Abstract

Background

Repeat infection with Chlamydia trachomatis is common and increases the risk of sequelae in women and HIV seroconversion in men who have sex with men (MSM). Despite guidelines recommending chlamydia retesting three months after treatment, retesting rates are low. We are conducting the first randomised controlled trial to assess the effectiveness of home collection combined with short message service (SMS) reminders on chlamydia retesting and reinfection rates in three risk groups.

Methods/Design

The REACT (retest after Chlamydia trachomatis) trial involves 600 patients diagnosed with chlamydia: 200 MSM, 200 women and 200 heterosexual men recruited from two Australian sexual health clinics where SMS reminders for retesting are routine practice. Participants will be randomised to the home group (3-month SMS reminder and home-collection) or the clinic group (3-month SMS reminder to return to the clinic). Participants in the home group will be given the choice of attending the clinic if they prefer. The mailed home-collection kit includes a self-collected vaginal swab (women), UriSWAB (Copan) for urine collection (heterosexual men), and UriSWAB plus rectal swab (MSM). The primary outcome is the retest rate at 1-4 months after a chlamydia diagnosis, and the secondary outcomes are: the repeat positive test rate; the reinfection rate; the acceptability of home testing with SMS reminders; and the cost effectiveness of home testing. Sexual behaviour data collected via an online survey at 4-5 months, and genotyping of repeat infections, will be used to discriminate reinfections from treatment failures. The trial will be conducted over two years. An intention to treat analysis will be conducted.

Discussion

This study will provide evidence about the effectiveness of home-collection combined with SMS reminders on chlamydia retesting, repeat infection and reinfection rates in three risk groups. The trial will determine client acceptability and cost effectiveness of this strategy.

Trial registration

Australian and New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry ACTRN12611000968976.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Chlamydia trachomatis is the most frequently reported sexually transmitted infection in most developed countries and notification rates are increasing steadily each year [1–3]. In many countries, the greatest burden of infection is among young heterosexual men and women aged 15-24 years, with population-based prevalence estimates ranging from 3 to 6% [4–7]. High prevalence rates have also been reported in men who have sex with men (MSM), ranging from 5 to 9% for rectal infections and 3 to 6% for urethral infections [8–11].

Repeat chlamydial infections

Repeat chlamydial infections following treatment are also common. In a prospective cohort of 16-24 year old women attending general practices in the United Kingdom, a repeat infection rate of 29.9% per year following treatment was reported (95% confidence interval [CI]: 19.7-45.4%) [12]. An Australian cohort of 1116 women aged 16-25 years reported a repeat infection rate of 18% at 3 months (95% CI: 8-34%) and 22.3% by 12 months (95% CI: 13.2, 37.6) following treatment [13]. In a review of eight studies, it was reported that 10.9% of heterosexual of men with active follow-up had a repeat infection at 4 months [14]. Higher rates of repeat infection after treatment have been reported in MSM [15]. Repeat chlamydial infections increase the risk of chlamydia-related sequelae such as pelvic inflammatory disease and infertility, when compared to initial infection [16], and in MSM, repeat rectal chlamydia or gonorrhoea infections have been associated with an increased risk of HIV seroconversion [17].

Repeat positive chlamydia tests may result from reinfection from the same partner, an infection from a new partner, inadequate treatment or treatment failure [18]. Batteiger et al. found that of the repeat positive tests among young women participating in a longitudinal cohort, 84.2% were definite, probable, or possible reinfections (different genotypes +/- unprotected sex); 13.7% were probable or possible treatment failures; and 2.2% persisted without documented treatment [18]. This study and others [19, 20], have demonstrated that treatment failure with azithromycin may be a contributing factor in repeat positive chlamydia tests, and this has been the subject of recent debate [21, 22].

Chlamydia retesting

Retesting at 3 months is important to prevent onward transmission and sequelae associated with repeat infections. Given that the majority of repeat infections are the result of existing partners not being treated, repeat positivity is also an important indicator of the effectiveness of partner notification.

Although clinical guidelines in a number of countries recommend retesting after treatment for chlamydia [23–27], retesting rates are low, especially amongst men. In a recent analysis of 2008-2010 United States (US) laboratory data, chlamydia retesting rates within a year among men and non-pregnant women, were 22% and 38% respectively [28]. In a 5-year period between 2004 and 2008, the proportion of Australian sexual health service patients with chlamydia infection who were retested in 30-120 days was 8.6% in MSM, 11.9% in heterosexual males and 17.8% in heterosexual females [29]. In England, retesting rates within a year among 15 to 24 year olds in 2010 ranged from 18.4% in the National Chlamydia Screening Program dataset to 26.1% in the genitourinary medicine clinic activity dataset [30].

The true clinical impact of increased rescreening has not yet been established. Of the interventions aiming to increase retesting conducted to date, few measured repeat positive tests and none discriminated between reinfections and treatment failures [31–37]. Among the interventions which did report repeat positive test rates, despite higher retesting rates, the rate of repeat infection in all but one study, was lower in the intervention arm compared with the control arm. However only one study showed this difference was statistically different.

Based on the study by Batteiger et al. [18], the majority of repeat positive tests would be expected to be reinfections, which suggests that rescreening strategies may be reaching more asymptomatic patients and those at lower risk of reinfection. For example, in the postcard reminder study by Paneth-Pollack et al. [32], 50% of retesters in the intervention arm were asymptomatic compared to 23% in the control group. People with symptoms may be more likely to initiate retesting, and this may help to account for the lower rates of repeat infection found, despite higher retesting rates. This highlights the importance of measuring both retesting and repeat positive test rates in studies which aim to increase retesting.

The high sensitivity of nucleic acid amplification tests (NAAT) has enabled the use of self-collected specimens, such as urine and vaginal swabs, for the diagnosis and screening of chlamydia and gonococcal infections [38]. Self-collected urine, vaginal and rectal specimens have been widely used in a variety of clinical and non-clinical settings to increase access to chlamydia screening and rescreening [37, 39–42] and have been found to be acceptable in men and women [43–46]. A previous study in Australia has confirmed the robustness of swabs when transported for up to a week through routine postal systems [47].

Interventions to increase chlamydia retesting

Mailed home collection kits have been demonstrated in a meta-analysis of controlled studies by Guy and colleagues, to increase retesting rates by an average of 30% (pooled effect estimate = 1.30; 95% CI: 1.10-1.50) [48]. The same meta-analysis showed reminder strategies including phone calls (+/- letters) and postcard reminders also resulted in a modest increase in rescreening.

A reminder strategy that was not used in the studies reviewed by Guy et al. was the use of short message services (SMS) reminders. SMS and telephone reminders have been found to be effective for a variety of health related purposes such as reducing missed appointments [49] and increasing vaccination uptake [50], with SMS reminders shown to be more cost-effective [49, 51]. SMS reminders have the advantage of automation, convenience, confidentiality and immediacy [52] and have been found to be acceptable in the sexual health context [53, 54]. Subsequent to the review by Guy et al. [48], three Australian before-after studies have demonstrated that SMS reminders increase STI retesting rates in sexual health clinic patients [35, 52, 55].

Cost effectiveness

There is limited evidence regarding the cost effectiveness of home-based versus clinic based rescreening for sexually transmitted infections. A study by Xu et al. found home-collection to be less costly than clinic-based rescreening at $54 per self-collected test versus $118 per clinic-based test [33].

We describe here a randomised controlled trial that aims to assess the effectiveness of home-collection combined with SMS reminders on chlamydia retesting rates in MSM, women and heterosexual men. The trial will also determine client acceptability and cost effectiveness of the approach.

Methods/Design

Study design/setting

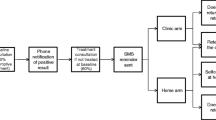

This is a non-blinded, randomised controlled trial (RCT) where individuals are randomised in a 1:1 ratio to an SMS reminder and home-based, self-collected samples (home group) or an SMS reminder and clinic testing (clinic group). The trial is being conducted in two Australian sexual health clinics (Melbourne and Sydney Sexual Health Centres). The study is diagrammatically represented in Figure 1.

Research objectives

The primary objective of the trial is to compare the retest rate 1-4 months after treatment for chlamydia among participants in the home group (3-month SMS reminder and home-collection) compared with the clinic group (3-month SMS reminder to return to the clinic). The secondary objectives are to: compare the chlamydia repeat positive test rate in participants in the home group compared with the clinic group; assess the reinfection rate among participants who retested; determine the acceptability of home-based testing with SMS reminders; and compare health provider costs of home-based specimen collection with routine (clinic based) retesting.

Duration of trial

The study will require 24 months to complete: 6 months for recruitment and 18 months to complete follow-up, data collection and analysis.

Blinding

Given the nature of the intervention, it is not possible to blind the patient to their trial group. However, the statistician analysing the RCT data will be blinded to the study group.

Ethical considerations

The REACT study protocol has been approved by the Alfred Health Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC), South Eastern Sydney and Illawarra Area Health Service HREC and the University of New South Wales HREC.

Trial inclusion and exclusion criteria

Patients will be included if they: are aged 16 years or above; have a mobile phone; are heterosexual men (reported sexual contact only with female partner/s in the last 12 months)/MSM (reported sexual contact with male partner/s in the last 12 months)/or women; have a diagnosis of chlamydia infection (diagnosed by NAAT); and reside in a jurisdiction serviced by the sexual health clinic and plan to stay in that jurisdiction for the next six months. Patients will be excluded if they: are unwilling or unable to comply with all the requirements of the protocol; cannot speak English; are HIV positive or a current sex worker.

Recruitment

A total of 600 participants (200 MSM, 200 women and 200 heterosexual men) diagnosed with chlamydia are required. The trial will be advertised by postcards left in the waiting room or provided to patients at the time of chlamydia testing or treatment. All positive chlamydia results will be reviewed by study nurses based at each of the clinics. Among potentially eligible patients, the nurse will contact the patient by telephone and let them know of their chlamydia diagnosis and for those not already treated, recommend they come to the clinic for treatment. During the call the nurse will give a brief overview of the study and asked the patient for permission to pass on their contact details to a member of the research team. If the patient agrees, a member of the research team will then contact the patient to explain the trial requirements and undertake a verbal consent process.

Randomisation

Eligible patients will be randomised to the intervention or control strategies using a minimisation approach. This will maximise the balance across the risk groups (MSM, women and heterosexual men). Computer generated randomisation codes, stratified for risk group will be produced by a statistician and sealed in opaque envelopes. Once consent has been given, the research team member will select the next randomisation envelope according to the risk group of the patient and inform the patient which group they have been assigned to – the home or clinic group.

Intervention (home testing) arm

The home-collection kit will contain the collection device, illustrated collection instructions, laboratory request form and pre-paid envelope. The collection devices will vary according to the patient’s risk group as follows: for heterosexual men the collection device will consist of a sponge-based urine collection device (UriSWAB®, Copan Diagnostics, CA, USA); for women the collection device will consist of a swab for lower vaginal self-collection and for MSM two collection devices will be provided: (i) a swab for rectal self-collection; and (ii) a UriSWAB for first-pass urine collection.

The swabs and request form will be pre-labelled with identifying information. Three months after chlamydia diagnosis, the clinic will send an SMS reminder to encourage the patient to either: (i) return to the clinic for retesting; or (ii) collect a sample/s using the collection kit and mail it to the lab with the request slip. A purpose-built database will be used to generate a list of patients due to be mailed home-collection kits. The collection kit will be mailed to the patient in an unmarked envelope by the research team. Patients will be instructed in a covering letter to collect their specimen/s and package them according to the instructions provided and mail them to the laboratory in the pre-paid envelope.

Control (standard care) arm

Three months after chlamydia diagnosis patients will be sent an SMS reminder by the clinic to encourage them to return to the clinic for retesting. This is routine practice at the two participating clinics.

Specimen processing, testing and results

Chlamydia testing

The baseline chlamydia positive specimens (600) and clinic group retesting specimens will be tested by the clinic’s usual pathology provider. Specimen collection and processing will be in accordance with the pathology provider’s usual protocol, and pathology providers will be requested to store chlamydia positive baseline and retest specimens until the end of the trial. Results will be given to patients according to the clinic’s protocol for managing test results. Treatment for chlamydia positive cases is 1g single dose azithromycin according to the routine practice [25].

All home group retesting specimens will be processed by a specialist laboratory. The laboratory will also be asked to store the specimens until the end of the trial. Results will be reported back to, and managed by the referring clinics, in the usual manner.

Serovar detection

Confirmation of each chlamydia serovar, and detection of genotypic variants will be determined by qPCR assay and DNA sequencing [56]. qPCR will be performed in a primary chlamydia group-specific multiplex PCR which utilises two primers and four probes, specific to all chlamydia types, including the B group (B, E, D, L1, and L2), C group (A, C, H, I, J, K, and L3) or intermediate group (F and G) serovars. The primary group-specific PCR will be used to determine which set of secondary serovar-specific PCRs to perform, as described previously [56]. When the same serovar is detected at diagnosis and follow-up, further discriminatory confirmation of relatedness using multilocus sequence typing (MLST) will be conducted [57].

Outcomes

The primary outcome is the proportion of patients who retest between 1-4 months after a chlamydia diagnosis.

The secondary outcomes are:

-

1.

The repeat positive test rate.

-

2.

Reinfection rate.

-

3.

Acceptability of home testing with SMS reminders.

-

4.

Cost effectiveness of home testing.

Data collection methods and variables

Clinical and sexual behaviour data

Among all patients who test positive at the study site in the recruitment period a range of variables (condom use, number of partners, previous chlamydia diagnoses, anal and uro-genital symptoms, treatment and chlamydia results) will be extracted from the patient management system for all episodes of care during the trial period.

Acceptability data

Participants in both study arms will be asked to complete a quantitative survey online. An SMS reminder will be sent to participants at 4.5 and 5 months (after ascertainment of the primary outcome). The SMS will contain the study website and the participant’s code which is linked to their patient details captured at consent. The survey will investigate participants’ living situation (with parents or not), chlamydia treatment for themselves and partners, sexual behaviour, retesting at the same clinic or elsewhere, reasons for not retesting, acceptability of SMS reminders, and for participants in the home group, the acceptability of home testing, ease of collection and retesting preferences (home or clinic retesting). On completion of the survey participants will be sent a $40 AUD voucher, irrespective of retesting. If the participant notes on the online survey that they had a chlamydia test at a clinic other than the sexual health clinic since their positive test, the participant will be mailed a consent form to obtain their permission to contact this clinic to obtain the results of this test. The consent form will then be mailed to the doctor at the clinic.

Cost analysis data

The cost of an organised chlamydia retesting program will be assessed from the perspective of the health care provider only. Cost data will relate to patients seen in the 12 months prior to the commencement of the study. De-identified data will be extracted from the patient management system for each patient interaction including: triage time, consultation time, staff type, risk group of client, type of clinic (regular or fast track clinical service known as the express clinic) and number of SMS reminders sent. Where these data are not available through the patient management system, (for example phone times and administration time), log sheets will be developed for the relevant staff members to document the time taken for each interaction.

Analysis

Chlamydia retesting and repeat positive test rates

The final analysis of primary and secondary outcomes will be performed at the conclusion of the trial. Patient baseline characteristics will be compared by randomised group as appropriate but no formal statistical tests will be undertaken. Analyses will be conducted using STATA statistical analysis software. An intention-to-treat approach will be taken.

In the initial analysis, the percentage of individuals who returned will be cross tabulated by randomised group. The analysis will determine the effect of the intervention on primary and secondary outcomes overall and between risk groups (MSM, women and heterosexual men). The primary analysis will be retesting rates between 1-4 months after a chlamydia diagnosis. Per protocol analyses will include: i) among the home-testing arm: the percentage who retested at home compared with the clinic, and the median time to retest among those who tested at the clinic versus home; ii) in each arm: the median time to retest (overall and in those who retested positive); and iii) factors associated with repeat positivity among those who retested at 1-4 months.

Reinfection rate

Consistent with the algorithm described by Batteiger [18] repeat positive cases will be discriminated using sexual behaviour data (from the questionnaires and data extracted from the patient management system) and chlamydia genotyping. To differentiate between chlamydia reinfection, treatment failure or persistent infection, we will use a modified version of the chlamydia repeat infection algorithm developed by Batteiger et al. [18] and adapted by Walker et al. [13] (Figure 2). If a participant has two infections with different genotypes, then the second infection will be considered a reinfection. If participants received appropriate treatment but had unprotected sex with their current or new partners, the second infection will also be considered a reinfection. Treatment failure will be defined as a positive chlamydia result following appropriate treatment if the participant reported either no sex between the two episodes or always using condoms with sex. An infection will be defined as persistent if the participant has two consecutive positive chlamydia test results and was not treated between episodes [18, 13].

Acceptability

The acceptability of home-testing in the home group participants will be compared in the three different risk groups using a Chi-2 test, with breakdowns according to age group, sex, symptoms and sexual behaviour. Factors associated with acceptability will be assessed using multivariate logistic regression. The primary outcome of the analysis will be preference for home-testing.

Cost analysis

In order to estimate the costs of each component of retesting, a flowchart will be constructed to describe the pathway of patients from their initial chlamydia test, notification of results and treatment, to retest, either at the clinic or via home-based collection, notification of results and treatment. Labour costs will be estimated based on time, staff type and average salary. All equipment for each clinical interaction will be listed and priced according to clinic inventories. The costs of diagnostic testing will be based on the Medicare Benefits Schedule (a listing of the Medicare services subsidised by the Australian government). The cost of clinic and home-based retesting will be compared. The cost of testing at the regular clinic versus the express clinic and between risk groups will also be compared. Using the cost data and primary outcome data of retesting and repeat positive test rates, a cost-effectiveness analysis will be undertaken.

Data storage

A central database containing de-identified quantitative trial data will be held at the Kirby Institute. All electronic files will be password protected and only the trial research staff and statistician will have access. Participants’ contact details will be securely stored separately to the quantitative trial data.

Sample size calculation

The sample size is based on a chlamydia retesting rate of 40% in the clinic group (receiving the SMS) based on findings from previous studies. In the analysis we are interested in assessing the primary outcome in the three risk groups (200 MSM, 200 women and 200 heterosexual men) and overall. A sample size of 194 in each risk group will achieve at least 80% statistical power to detect an overall 20% difference (60% compared to 40%) in retesting between home and clinic groups. The 194 will be rounded to 200, and summed up to give an overall sample size of 600. A total sample size of 600 will achieve at least 80% statistical power to detect an overall 12% difference (52% compared to 40%) between home and clinic group for all three risk groups combined. Assuming the retesting rates above are achieved, and the repeat positivity in the clinic group is 10%, we have 80% power to detect an increase of 13% (10% compared to 23%) in repeat positivity.

Registration

This trial is registered with the Australian and New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry: ACTRN12611000968976.

Discussion

Chlamydia retesting at 3 months after infection is an important strategy to detect reinfections and to monitor the effectiveness of partner notification, but retesting rates are low. There is some evidence from other studies that home-based specimen collection results in a modest increase in retesting for repeat chlamydial infection as do SMS reminders, but no studies have combined these two strategies.

One of the major problems in interpreting the findings from studies to date is suboptimal study designs. Many of the studies included in the review by Guy et al. [48] were evaluated using a before-after design and it is possible that the intervention group patients may have had characteristics which facilitated rescreening irrespective of receiving the intervention. Few studies aimed to control for these differences. Some may also have underestimated retesting as a proportion of patients may have undergone screening at other health services. Several studies also had small sample sizes, precluding any analysis of the differential impact according to risk behaviour, symptoms or demographics. Another limitation of the intervention research in this area is that most studies have defined a repeat positive test as a reinfection. However repeat positive tests results may represent reinfections, persistence without treatment, or treatment failure, with varying implications for each. In addition many of the previous retesting studies included women only [31, 33, 36].

Most of the previous interventions which have aimed to increase retesting have focused on offering people one strategy or another. However people may choose different retesting strategies depending on their personal circumstances. For example, in a US study by Sparks et al. [58], heterosexuals aged 14 years or older were given a choice of either mailing a specimen for testing or returning to the clinic for retesting, and 30% of participants in the intervention arm chose the mailed retesting option compared with 70% who opted to attend the clinic for rescreening. Another US study of home screening by Cook et al. [31] reported that although most young women (179) received their home-collection kit in the mail, 18 (9%) opted to pick it up from the clinic, and a study in Australia found that young people were less likely to return home-collection kits if they lived with their parents [59]. These findings highlight that to maximise the effectiveness of an intervention, it is important to provide different options to suit the diverse needs and preferences of different risk groups and individuals.

This world first trial will provide evidence about the effectiveness of home collection and SMS reminders as a combined strategy, to increase retesting and detect repeat positive tests following treatment for chlamydia in three risk groups (MSM, women and heterosexual men), as well as providing information about the acceptability and cost effectiveness of this strategy. Given limited resources, offering innovative and effective ways to improve retesting rates in those at highest risk of reproductive and other chlamydia-related morbidity and HIV transmission, is an important strategy for chlamydia control.

References

Kirby Institute: HIV, viral hepatitis and sexually transmitted infections in Australia Annual Surveillance Report 2012. 2012, Sydney: Kirby Institute, University of New South Wales

Health Protection Agency HIV Sexually Transmitted Infections Department Centre for Infections: Sexually Transmitted Infections and Young People in the United Kingdom. 2008, London: Health Protection Agency HIV and Sexually Transmitted Infections Department Centre for Infections

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC): Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance 2011. 2012, Atlanta: United States Department of Health and Human Services

Hocking JS, Willis J, Tabrizi S, Fairley CK, Garland SM, Hellard M: A chlamydia prevalence survey of young women living in Melbourne, Victoria. Sex Health. 2006, 3 (4): 235-240. 10.1071/SH06033.

Goulet V, de Barbeyrac B, Raherison S, Prudhomme M, Semaille C, Warszawski J: Prevalence of Chlamydia trachomatis: results from the first national population-based survey in France. Sex Transm Infect. 2010, 86 (4): 263-270. 10.1136/sti.2009.038752.

Datta SD, Torrone E, Kruszon-Moran D, Berman S, Johnson R, Satterwhite CL, Papp J, Weinstock H: Chlamydia trachomatis trends in the United States among persons 14 to 39 years of age, 1999-2008. Sex Transm Dis. 2012, 39 (2): 92-96. 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31823e2ff7.

Eggleston E, Rogers SM, Turner CF, Miller WC, Roman AM, Hobbs MM, Erbelding E, Tan S, Villarroel MA, Ganapathi L: Chlamydia trachomatis infection among 15- to 35-year-olds in Baltimore, MD. Sex Transm Dis. 2011, 38 (8): 743-749.

Vodstrcil LA, Fairley CK, Fehler G, Leslie D, Walker J, Bradshaw CS, Hocking JS: Trends in chlamydia and gonorrhea positivity among heterosexual men and men who have sex with men attending a large urban sexual health service in Australia, 2002-2009. BMC Infect Dis. 2011, 11: 158-10.1186/1471-2334-11-158.

Annan NT, Sullivan AK, Nori A, Naydenova P, Alexander S, McKenna A, Azadian B, Mandalia S, Rossi M, Ward H, Nwokolo N: Rectal chlamydia–a reservoir of undiagnosed infection in men who have sex with men. Sex Transm Infect. 2009, 85 (3): 176-179. 10.1136/sti.2008.031773.

Kent CK, Chaw JK, Wong W, Liska S, Gibson S, Hubbard G, Klausner JD: Prevalence of rectal, urethral, and pharyngeal chlamydia and gonorrhea detected in 2 clinical settings among men who have sex with men: San Francisco, California, 2003. Clin Infect Dis. 2005, 41 (1): 67-74. 10.1086/430704.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC): Clinic-based testing for rectal and pharyngeal Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis infections by community-based organizations-five cities, United States, 2007. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009, 58 (26): 716-719.

Scott LaMontagne D, Baster K, Emmett L, Nichols T, Randall S, McLean L, Meredith P, Harindra V, Tobin JM, Underhill GS, Graham Hewitt W, Hopwood J, Gleave T, Ghosh AK, Mallinson H, Davies AR, Hughes G, Fenton KA: Incidence and reinfection rates of genital chlamydial infection among women aged 16–24 years attending general practice, family planning and genitourinary medicine clinics in England: a prospective cohort study by the Chlamydia Recall Study Advisory Group. Sex Transm Infect. 2007, 83 (4): 292-303. 10.1136/sti.2006.022053.

Walker J, Tabrizi SN, Fairley CK, Chen MY, Bradshaw CS, Twin J, Taylor N, Donovan B, Kaldor JM, McNamee K, Urban E, Walker S, Currie M, Birden H, Bowden F, Gunn J, Pirotta M, Gurrin L, Harindra V, Garland SM, Hocking JS: Chlamydia trachomatis incidence and re-infection among young women–behavioural and microbiological characteristics. PLoS One. 2012, 7 (5): e37778-10.1371/journal.pone.0037778.

Fung M, Scott KC, Kent CK, Klausner JD: Chlamydial and gonococcal reinfection among men: a systematic review of data to evaluate the need for retesting. Sex Transm Infect. 2007, 83 (4): 304-309. 10.1136/sti.2006.024059.

Harte D, Mercey D, Jarman J, Benn P: Is the recall of men who have sex with men (MSM) diagnosed as having bacterial sexually transmitted infections (STIs) for re-screening a feasible and effective strategy?. Sex Transm Infect. 2011, 87 (7): 577-582. 10.1136/sextrans-2011-050144.

Haggerty CL, Gottlieb SL, Taylor BD, Low N, Xu F, Ness RB: Risk of Sequelae after Chlamydia trachomatis Genital Infection in Women. J Infect Dis. 2010, 201 (Suppl 2): S134-S155.

Bernstein KT, Marcus JL, Nieri G, Philip SS, Klausner JD: Rectal gonorrhea and chlamydia reinfection is associated with increased risk of HIV seroconversion. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010, 53 (4): 537-543. 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181c3ef29.

Batteiger BE, Tu W, Ofner S, Van Der Pol B, Stothard DR, Orr DP, Katz BP, Fortenberry JD: Repeated Chlamydia trachomatis Genital Infections in Adolescent Women. J Infect Dis. 2010, 201 (1): 42-51. 10.1086/648734.

Golden MR, Whittington WLH, Handsfield HH, Hughes JP, Stamm WE, Hogben M, Clark A, Malinski C, Helmers JRL, Thomas KK, Holmes KK: Effect of expedited treatment of sex partners on recurrent or persistent gonorrhea or chlamydial infection. N Engl J Med. 2005, 352 (7): 676-685. 10.1056/NEJMoa041681.

Schwebke JR, Rompalo A, Taylor S, Seña AC, Martin DH, Lopez LM, Lensing S, Lee JY: Re-Evaluating the Treatment of Nongonococcal Urethritis: Emphasizing Emerging Pathogens–A Randomized Clinical Trial. Clin Infect Dis. 2011, 52 (2): 163-170. 10.1093/cid/ciq074.

Handsfield HH: Questioning azithromycin for chlamydial infection. Sex Transm Dis. 2011, 38 (11): 1028-1029. 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e318227a366.

Horner PJ: Azithromycin antimicrobial resistance and genital Chlamydia trachomatis infection: duration of therapy may be the key to improving efficacy. Sex Transm Infect. 2012, 88 (3): 154-156. 10.1136/sextrans-2011-050385.

Chlamydia Trachomatis UK Testing Guidelines. http://www.bashh.org/documents/3352.pdf,

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC): Sexually Transmitted Diseases Treatment Guidelines, 2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010, 59 (No. RR-12): 46-

Australasian Chapter of Sexual Health Medicine: National management guidelines for sexually transmissible infections. 2008, Melbourne: Royal Australasian College of Physicians

Bourne C, Edwards B, Shaw M, Gowers A, Rodgers C, Ferson M: Sexually transmissible infection testing guidelines for men who have sex with men. Sex Health. 2008, 5 (2): 189-191. 10.1071/SH07092.

Lanjouw E, Ossewaarde JM, Stary A, Boag F, van der Meijden WI: 2010 European guideline for the management of Chlamydia trachomatis infections. Int J STD AIDS. 2010, 21 (11): 729-737. 10.1258/ijsa.2010.010302.

Hoover KW, Tao G, Nye MB, Body BA: Suboptimal adherence to repeat testing recommendations for men and women with positive Chlamydia tests in the United States, 2008-2010. Clin Infect Dis. 2013, 56 (1): 51-57. 10.1093/cid/cis771.

Guy R, Wand H, Franklin N, Fairley CK, Chen MY, O’Connor CC, Marshall L, Grulich AE, Kaldor JM, Hellard M, Donovan B: Re-testing for chlamydia at sexual health services in Australia, 2004-08. Sex Health. 2011, 8 (2): 242-247. 10.1071/SH10086.

Woodhall SC, Atkins JL, Soldan K, Hughes G, Bone A, Gill ON: Repeat genital Chlamydia trachomatis testing rates in young adults in England, 2010. Sex Transm Infect. 2013, 89 (1): 51-56. 10.1136/sextrans-2012-050490.

Cook RL, Ostergaard L, Hillier SL, Murray PJ, Chang CC, Comer DM, Ness RB: Home screening for sexually transmitted diseases in high-risk young women: randomised controlled trial. Sex Transm Infect. 2007, 83 (4): 286-291. 10.1136/sti.2006.023762.

Paneth-Pollak R, Klingler EJ, Blank S, Schillinger JA: The elephant never forgets; piloting a chlamydia and gonorrhea retesting reminder postcard in an STD clinic setting. Sex Transm Dis. 2010, 37 (6): 365-368.

Xu F, Stoner BP, Taylor SN, Mena L, Tian LH, Papp J, Hutchins K, Martin DH, Markowitz LE: Use of home-obtained vaginal swabs to facilitate rescreening for Chlamydia trachomatis infections: two randomized controlled trials. Obstet Gynecol. 2011, 118 (2 Pt 1): 231-239.

Gotz HM, van den Broek IV, Hoebe CJ, Brouwers EE, Pars LL, Fennema JS, Koekenbier RH, van Ravesteijn S, Op De Coul EL, van Bergen J: High yield of reinfections by home-based automatic rescreening of Chlamydia positives in a large-scale register-based screening programme and determinants of repeat infections. Sex Transm Infect. 2013, 89 (1): 63-69. 10.1136/sextrans-2011-050455.

Zou H, Fairley CK, Guy R, Bilardi J, Bradshaw CS, Garland SM, Sze JK, Afrizal A, Chen MY: Automated, computer generated reminders and increased detection of gonorrhoea, chlamydia and syphilis in men who have sex with men. PLoS One. 2013, 8 (4): e61972-10.1371/journal.pone.0061972.

Kohn R, Reynolds A, Snell A, Kohn RP, Reynolds A, Snell A, Marcus JL, Philip SS: New Reminder System Does Not Improve Chlamydia Re-Screening Rate In: National STD Prevention Conference. 2010, GA: Atlanta

Gotz HM, Wolfers ME, Luijendijk A, van den Broek IV: Retesting for genital Chlamydia trachomatis among visitors of a sexually transmitted infections clinic: randomized intervention trial of home- versus clinic-based recall. BMC Infect Dis. 2013, 13 (1): 239-10.1186/1471-2334-13-239.

Masek BJ, Arora N, Quinn N, Aumakhan B, Holden J, Hardick A, Agreda P, Barnes M, Gaydos CA: Performance of Three Nucleic Acid Amplification Tests for Detection of Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae by Use of Self-Collected Vaginal Swabs Obtained via an Internet-Based Screening Program. J Clin Microbiol. 2009, 47 (6): 1663-1667. 10.1128/JCM.02387-08.

Smith K, Harrington K, Wingood G, Oh M, Hook IE, DiClemente RJ: Self-obtained vaginal swabs for diagnosis of treatable sexually transmitted diseases in adolescent girls. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2001, 155 (6): 676-679. 10.1001/archpedi.155.6.676.

Wiesenfeld HC, Lowry DL, Heine RP, Krohn MA, Bittner H, Kellinger K, Shultz M, Sweet RL: Self-collection of vaginal swabs for the detection of Chlamydia, gonorrhea, and trichomoniasis: opportunity to encourage sexually transmitted disease testing among adolescents. Sex Transm Dis. 2001, 28 (6): 321-325. 10.1097/00007435-200106000-00003.

Bloomfield PJ, Steiner KC, Kent CK, Klausner JD: Repeat chlamydia screening by mail, San Francisco. Sex Transm Infect. 2003, 79 (1): 28-30. 10.1136/sti.79.1.28.

Graseck AS, Shih SL, Peipert JF: Home versus clinic-based specimen collection for Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2011, 9 (2): 183-194. 10.1586/eri.10.164.

Stephenson J, Carder C, Copas A, Robinson A, Ridgway G, Haines A: Home screening for chlamydial genital infection: is it acceptable to young men and women?. Sex Transm Infect. 2000, 76 (1): 25-27. 10.1136/sti.76.1.25.

van der Helm JJ, Hoebe CJ, van Rooijen MS, Brouwers EE, Fennema HS, Thiesbrummel HF, Dukers-Muijrers NH: High performance and acceptability of self-collected rectal swabs for diagnosis of Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae in men who have sex with men and women. Sex Transm Dis. 2009, 36 (8): 493-497. 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181a44b8c.

Soni S, White JA: Self-screening for Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis in the human immunodeficiency virus clinic–high yields and high acceptability. Sex Transm Dis. 2011, 38 (12): 1107-1109. 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31822e6136.

Dodge B, Van Der Pol B, Rosenberger JG, Reece M, Roth AM, Herbenick D, Fortenberry JD: Field collection of rectal samples for sexually transmitted infection diagnostics among men who have sex with men. Int J STD AIDS. 2010, 21 (4): 260-264. 10.1258/ijsa.2009.009056.

Costa AM, Fairley CK, Garland SM, Tabrizi SN: Evaluation of self-collected urine dip swab method for detection of Chlamydia trachomatis. Sex Health. 2009, 6 (3): 213-216. 10.1071/SH09013.

Guy R, Hocking J, Low N, Ali H, Bauer HM, Walker J, Klausner JD, Donovan B, Kaldor JM: Interventions to increase rescreening for repeat chlamydial infection. Sex Transm Dis. 2012, 39 (2): 136-146. 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31823ed4ec.

Stubbs ND, Geraci SA, Stephenson PL, Jones DB, Sanders S: Methods to reduce outpatient non-attendance. Am J Med Sci. 2012, 344 (3): 211-219. 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e31824997c6.

Warwick Z, Dean G, Carter P: B safe, B sorted: results of a hepatitis B vaccination outreach programme. Int J STD AIDS. 2007, 18 (5): 335-337. 10.1258/095646207780749673.

Chen ZW, Fang LZ, Chen LY, Dai HL: Comparison of an SMS text messaging and phone reminder to improve attendance at a health promotion center: a randomized controlled trial. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B. 2008, 9 (1): 34-38. 10.1631/jzus.B071464.

Bourne C, Knight V, Guy R, Wand H, Lu H, McNulty A: Short message service reminder intervention doubles sexually transmitted infection/HIV re-testing rates among men who have sex with men. Sex Transm Infect. 2011, 87 (3): 229-231. 10.1136/sti.2010.048397.

Lim MSC, Hocking JS, Hellard ME, Aitken CK: SMS STI: a review of the uses of mobile phone text messaging in sexual health. Int J STD AIDS. 2008, 19 (5): 287-290. 10.1258/ijsa.2007.007264.

Cohen CE, Coyne KM, Mandalia S, Waters A-M, Sullivan AK: Time to use text reminders in genitourinary medicine clinics. Int J STD AIDS. 2008, 19 (1): 12-13. 10.1258/ijsa.2007.007149.

Guy R, Wand H, Knight V, Kenigsberg A, Read P, McNulty AM: SMS reminders improve re-screening in women and heterosexual men with chlamydia infection at Sydney Sexual Health Centre: a before-and-after study. Sex Transm Infect. 2013, 89 (1): 11-15. 10.1136/sextrans-2011-050370.

Stevens MP, Twin J, Fairley CK, Donovan B, Tan SE, Yu J, Garland SM, Tabrizi SN: Development and evaluation of an ompA quantitative real-time PCR assay for Chlamydia trachomatis serovar determination. J Clin Microbiol. 2010, 48 (6): 2060-2065. 10.1128/JCM.02308-09.

Hocking JS, Vodstrcil L, Huston WM, Timms P, Chen M, Worthington K, McIver R, Tabrizi SN: A cohort study of Chlamydia trachomatis treatment failure in women: a study protocol. BMC Infect Dis. 2013, 13 (1): 379-10.1186/1471-2334-13-379.

Sparks R, Helmers JR, Handsfield HH, Totten PA, Holmes KK, Wroblewski JK, Malinski C, Golden MR: Rescreening for gonorrhea and chlamydial infection through the mail: a randomized trial. Sex Transm Dis. 2004, 31 (2): 113-116. 10.1097/01.OLQ.0000109512.95959.ED.

Sacks-Davis R, Gold J, Aitken CK, Hellard ME: Home-based chlamydia testing of young people attending a music festival–who will pee and post?. BMC Public Health. 2010, 10: 376-10.1186/1471-2458-10-376.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2334/14/223/prepub

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by an Australian Government National Health and Medical Research Council grant.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Authors’ contributions

All authors contributed to the design of the study and have read, contributed to and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Smith, K.S., Hocking, J.S., Chen, M. et al. Rationale and design of REACT: a randomised controlled trial assessing the effectiveness of home-collection to increase chlamydia retesting and detect repeat positive tests. BMC Infect Dis 14, 223 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2334-14-223

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2334-14-223