Abstract

Background

Cryptosporidium spp and I. belli are intestinal opportunistic infections associated with HIV/AIDS. A decline in the incidence of these opportunistic infections due to HAART was reported. We aim to investigate these parasites among HAART naïve and experienced HIV patients in south Ethiopia.

Methods

A cross sectional study was carried out among 268 HIV- positive patients between January and September, 2007. Interview with questionnaires and document reviews were used to collect data. Stool samples were obtained from each patient and parasites were examined by direct, formol-ether and modified Ziehl-Neelsen stain for Cryptosporidium spp and I. belli. Univariate and multivariate analysis were carried out. Level of significance was set at p-value of 0.05.

Results

A total of 268 patients participated in the study. The mean age was 34.0 (±1 SD of 8.34) years. Females constituted 53.4% (143) of the study participants. Half of the study participants were on HAART; majorities (85.8%) of such patients were within the first year of treatment. The prevalence of Cryptosporidium spp was 34.3% (92/268) and I. belli was 1.5% (4/268). Dual infection was detected in two patients (0.75%). The crude analysis revealed significant reduction in the odds of Cryptosporidium spp infection among patients who have started HAART (crude OR = 0.59, 95% CI 0.35, 0.98). The adjusted analysis remained in the same direction but has lost significance (Adj OR 0.65, 95%CI 0.35, 1.24). No differences in the risk of developing infection with Cryptosporidium spp were observed between groups based on most recent CD4 counts, sex, duration on HAART and age (p > 0.05 for all variables). Patients with Cryptosporidium spp were more likely to report vomiting [Adj OR 2.34 (95% CI 1.22, 5.41)], weight loss [Adj OR 2.10 (95% CI 1.15, 3.81)] and chronic diarrhea [Adj OR 3.35 (95%CI 1.05, 10.63)].

Conclusion

There is high burden of infection with Cryptosporidium spp among HIV infected individuals in southern Ethiopia but that of I. belli is low. We recommend considering infection with Cryptosporidium spp in HIV infected people with chronic diarrhea, weight loss and vomiting for HAART naïve patients and/or for patients who are within the first year of starting HAART.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

HIV infected patients are susceptible to a variety of common and opportunistic infections due to progressive decline in their immunity status. Intestinal protozoan parasites that cause a mild or self-limited disease in immunocompetent individuals can cause protracted and severe diarrhea in immunocompromised patients. Among the intestinal protozoa that cause intestinal infections in immunocompromised patients, Cryptosporidium parvum and I. belli are most frequently encountered [1, 2].

Highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) can restore immunity by increasing memory and naïve CD4+ cells against pathogens [3, 4]. In the absence of a vaccine and affordable HAART, people living with HIV/AIDS, especially in developing countries, remain at risk of opportunistic infections (OIs) [5].

In Ethiopia, some studies have been conducted on the distribution and prevalence of opportunistic parasites among HIV infected individuals [5, 6]. The high rates of occurrence of Cryptosporidium parvum and Isospora belli in Ethiopia indicates that both are major public health concern specifically among HIV infected patients. The experiences of developed nations have proven that HAART reduces disease burden and improves the wellbeing and productivity of AIDS patients. Thus, the aim of this study was to assess the prevalence of intestinal opportunistic infections among HIV infected patients in south Ethiopia.

Methods

Study setting

The study was conducted in Yirgalem hospital which is located at a distance of 347 km south of Addis Ababa, the capital city of Ethiopia.

The study design and population

This was a cross sectional study which was conducted over a period of January - September, 2007. A total of 268 HIV infected patients who were on chronic care follow up at Yirgalem Hospital’s HIV clinic were sampled consecutively.

Sociodemographic characteristics and symptom related information were collected by directly interviewing patients using a structured questionnaire. The duration on treatment and types of HAART drug regimen and other information including the most recent CD4 cells counts were obtained from HIV care clinic registers (esp. ART register) and appropriate formats including the HIV care follow up forms and patient intake forms. Patient follow up forms were first used to retrieve the recent CD4 count and for how long the patient has taken HAART. We have used the ART register in cases where we were not able to get either of the information from the follow up form.

Diarrhea in this paper is defined as a subjective report by the study participants as having passage of unformed stool for more than 2 or 3 times a day. Moreover, we used reported duration of one month cut off to differentiate acute from chronic diarrhea.

Stool collection and processing

Single stool samples were collected in a leak proof vial and subjected to microscopy. SAF (Sodium acetate-Acetic acid-Formalin) preserved specimens and air dried smear were taken to the EHNRI’s (Ethiopian Health and Nutrition Research Institute) parasitology department for analysis. Each specimen was examined by direct wet-saline, formol-ether concentration and also stained by modified Ziehl-Neelsen/MZN to detect the oocysts. The EHNRI’s operating procedure for identification of coccida parasites was used. The size of the oocysts was utilized to differentiate Cryptosporidium spp from Cyclospora oocysts. A sample is labeled as positive for Cryptosporidium spp if the oocysts’ size ranges between 4–6 μm.

Ethical consideration

The ethical committee of Addis Ababa University (AAU), Biology Department approved the study proposal. Written informed consent was obtained from each study participant.

Data analysis

The data were entered, cleaned and analyzed using SPSS, version 16.0. Univariate analysis was first run to detect for factors that are associated with Cryptosporidium spp infections. Then adjusted analysis was performed by entering variables that have shown significance during univariate analysis or have been previously reported to be significant in other literatures. For all statistical decisions, the level of significance was set at α of 0.05.

Result

Characteristics of study participants

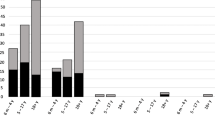

A total of 264 HIV infected patients participated in the study. The overall mean age of the study participants was 34.0 (±1 SD of 8.34). Females constituted 53.4% (143) of the study participants. Half of the study participants have been initiated on HAART. The commonest HAART regimen being used by the study participants was D4T/3TC/NVP, accounting for 63.4% (85/134) out of those patients initiated on HAART. Among patients who were initiated on HAART, 63.4% (85/134) have taken the therapy for more than 7 months and 85.8% (115/134) of such patients were within the first year of treatment (Table 1). Cryptosporidium spp infection was detected in 34.3% (92/268) of the study participants where as I. belli was identified only in 4 (1.5%) cases. Dual infection was detected in 2 patients (0.75%).

Clinical characteristics

Majority of the patients [90.3% (242)] had complaints of diarrhea. Among patients complaining of diarrhea almost half [48.5% (130)] of them had chronic diarrhea. The next major complaint was abdominal pain accounting for 70.1% (188) of the study participants (Table 2).

Factors associated with Cryptosporidium spp infection

No differences in the risk of developing infection with Cryptosporidium spp were observed between groups based on most recent CD4 counts, sex of the study participants, duration on HAART and age category of the study participants (p > 0.05 for all variables). The crude analysis has shown a significant reduction in the odds of Cryptosporidium spp infection among patients who have started HAART than among those who have not started treatment with HAART. The adjusted analysis remained in the same direction but has failed to attain level of statistical significance (Table 3).

Clinical symptoms associated with Cryptosporidium spp infection

Next we used logistic regression analysis for clinical symptoms reported by patients to verify their association with Cryptosporidium spp infection. Accordingly, patients with Cryptosporidium spp were more likely to report vomiting [Adj OR 2.34 (95% CI 1.22, 5.41)], weight loss [Adj OR 2.10 (95% CI 1.15, 3.81)] and chronic diarrhea when compared with patients who didn’t report diarrhea [Adj OR 3.35 (95%CI 1.05, 10.63)] (Table 4).

Discussion

In this paper it was found that there is high burden of infection with Cryptosporidium spp in south Ethiopia with a prevalence rate of 34.3% (92/268). This is in fact lower than a report from south west Ethiopia and Nigeria [7–9]. WHO recommends conducting 3 stool examinations collected on separate days because of the intermittent shading of the oocysts [2]. This might be one possible reason for the lower prevalence of Cryptosporidium spp in this paper. For instance, a report from Malawi has detected an additional 13% of Cryptosporidium parvum after conducting the second stool examination [9]. In addition, it is also important to consider the reported seasonal variations in the prevalence of Cryptosporidium spp infections [10, 11]. However, there are also papers from Ethiopia [12], Malaysia [13], India [14] and Iran [15] that have reported relatively lower prevalence of Cryptosporidium spp than the current prevalence. One possible reason for this could be that most of our study participants had complaints of diarrhea (90.3%) which may increase the detection yield of the parasites.

Similar to the findings with Certad et al., we have not seen gender difference in the prevalence of Cryptosporidium spp infection [16]. In addition, the role of CD4 cell counts seems to be insignificant on the prevalence of Cryptosporidium spp infection in this report. However, the effect of CD4 cells count on the prevalence of Cryptosporidium spp infection has been well documented and is biologically well explained [14, 17–19]. In this study CD4 counts were not measured at the time of the stool specimen collection; instead, we have taken the most recent CD4 counts that were documented in the HIV care clinic of the hospital. In fact it might have happened that the CD4 counts of patients may in reality be higher (for patients who started treatment) or lower (for HAART naïve patients) than the collected data by the time of stool sample collection. The median recent CD4 counts among patients infected with Cryptosporidium spp was 166.0 (IQR 80.8, 266.0) where as it was 192.0 (IQR 112.8, 280.0) among uninfected patients.

A couple of articles reported that after initiation of treatment with HAART, it is possible to eradicate Cryptosporidium spp among immunocompromised patients [3, 20]. In these two papers, the study patients were on second line treatment regimen consisting of protease inhibitors (PI) and were reported from high income countries. On the contrary none of our study patients were on PI. This could be a potential researchable area as to the effectiveness of PI and non-PI containing HAART for the eradication of Cryptosporidium spp. In the current study majority (85.8%) of patients who have started HAART were within their first year of their treatment. The median durations to clear off infection with Cryptosporidium spp as reported by the two papers above were 13.6 months [3] and 6 months [20]. The numbers of patients followed up were only twelve [3] and six [20]. The latter paper has noted the importance of response to HAART treatment for eradication of Cryptosporidium spp. This could indicate that in the current study the patients were not able to clear off the infection after one year of their medication with HAART. But it could also be that some of the patients were having transient infection [20] or relapse of infection as was pointed out by Carr et al. [3]. The other papers that reported reduction in prevalence of Cryptosporidium spp after starting HAART failed to report the association between the reduction and duration of treatment [6, 21]. Another factor to look at is the level of adherence of patients to their treatment regimen. The effectiveness of HAART highly depends on how adherent patients are on their treatment [22, 23] but low level of adherence to first line treatment is a common phenomenon in low income countries including Ethiopia [24, 25].

Concerning the main clinical features, we have observed that vomiting, reported weight loss and chronic diarrhea were strongly associated with Cryptosporidium spp infection. In order to control for the side effects of HAART, we have also included treatment status in to the regression analysis. The fact that chronic diarrhea is more common among Cryptosporidium spp infected patients than patients with no diarrhea has been reported in other literature [5, 10, 16, 26]. It has been documented that patients with Cryptosporidium spp infection can have weight loss of up to 10% when they have stool frequency as high as 10 per day [4, 16]. Even though we failed to objectively verify the degree of weight loss, we observed that there is strong association between reported weight loss and infection with Cryptosporidium spp.

The prevalence of I. belli was low when compared with other studies conducted previously [12, 14, 27]. One possible explanation for this could be the use of cotrimoxazole prophylaxis which is effective to control infection with I. belli.

Conclusion

In summary, there is still high burden of infection with Cryptosporidium spp among HIV infected individuals in southern Ethiopia. We recommend considering infection with Cryptosporidium spp in HIV infected people with chronic diarrhea, weight loss and vomiting for HAART naïve patients and/or for patients who are within the first year of starting treatment with HAART. It is also very important to note that patients with acute diarrhea can also be suffering from this infection as they could be in the early phase of the clinical manifestation of the disease.

References

Arora DR, Arora B: AIDS-associated parasitic diarrhoea. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2009, 27 (3): 185-190. 10.4103/0255-0857.53199.

WHO: IMAI District Clinician Manual: Guidelines for the management of common illnesses with limited resources Hospital Care for Adolescents and Adults: Guidelines for the management of illnesses with limited-resources. 2011, Switzerland, ISBN

Carr A, Marriott D, Field A, Vasak E, Cooper DA: Treatment of HIV-1-associated microsporidiosis and cryptosporidiosis with combination antiretroviral therapy. Lancet. 1998, 351 (9098): 256-261. 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)07529-6.

Chen XM, Keithly JS, Paya CV, LaRusso NF: Cryptosporidiosis. N Engl J Med. 2002, 346 (22): 1723-1731. 10.1056/NEJMra013170.

Fisseha B, Petros B, WoldeMichael T: Cryptosporidium and other parasites in Ethiopian AIDS patients with chronic diarrhoea. East Afr Med J. 1998, 75 (2): 100-101.

Teklemariam Z, Abate D, Mitiku H, Dessie Y: Prevalence of intestinal parasitic infection among HIV positive persons who are naive and on antiretroviral treatment in Hiwot Fana Specialized University Hospital. Eastern Ethiopia ISRN AIDS. 2013, 2013: 324329-

Ojurongbe O, Raji OA, Akindele AA, Kareem MI, Adefioye OA, Adeyeba AO: Cryptosporidium and other enteric parasitic infections in HIV-seropositive individuals with and without diarrhoea in Osogbo. Nigeria Br J Biomed Sci. 2011, 68 (2): 75-78.

Mengesha B: Cryptosporidiosis among medical patients with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome in Tikur Anbessa Teaching Hospital Ethiopia. East Afr Med J. 1994, 71 (6): 376-378.

Mariam ZT, Abebe G, Mulu A: Opportunistic and other intestinal parasitic infections in AIDS patients, HIV seropositive healthy carriers and HIV seronegative individuals in southwest Ethiopia. East Afr J Public Health. 2008, 5 (3): 169-173.

Cranendonk RJ, Kodde CJ, Chipeta D, Zijlstra EE, Sluiters JF: Cryptosporidium parvum and Isospora belli infections among patients with and without diarrhoea. East Afr Med J. 2003, 80 (8): 398-401.

Current WL, Garcia LS: Cryptosporidiosis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1991, 4 (3): 325-358.

Endeshaw T, Mohammed H, Woldemichael T: Cryptosporidium parvum and other instestinal parasites among diarrhoeal patients referred to EHNRI in Ethiopia. Ethiop Med J. 2004, 42 (3): 195-198.

Asma I, Johari S, Sim BLH, Lim YAL: How common is intestinal parasitism in HIV-infected patients in Malaysia?. Trop Biomed. 2011, 28 (2): 400-410.

Chopra RD, Dworkin MS: Descriptive epidemiology of enteric disease in Chennai India. Epidemiol Infect. 2013, 141 (5): 953-957. 10.1017/S0950268812001409.

Daryani A, Sharif M, Meigouni M, Mahmoudi FB, Rafiei A, Gholami S, Khalilian A, Gohardehi S, Mirabi MA: Prevalence of intestinal parasites and profile of CD4+ counts in HIV+/AIDS people in north of Iran, 2007–2008. Pak J Biol Sci. 2009, 12 (18): 1277-1281. 10.3923/pjbs.2009.1277.1281.

Certad G, Arenas-Pinto A, Pocaterra L, Ferrara G, Castro J, Bello A, Núñez L: Cryptosporidiosis in HIV-infected Venezuelan adults is strongly associated with acute or chronic diarrhea. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2005, 73 (1): 54-57.

Navin TR, Weber R, Vugia DJ, Rimland D, Roberts JM, Addiss DG, Visvesvara GS, Wahlquist SP, Hogan SE, Gallagher LE, Juranek DD, Schwartz DA, Wilcox CM, Stewart JM, Thompson SE, Bryan RT: Declining CD4+ T-lymphocyte counts are associated with increased risk of enteric parasitosis and chronic diarrhea: results of a 3-year longitudinal study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol. 1999, 20 (2): 154-159. 10.1097/00042560-199902010-00007.

Vyas N, Sood S, Sharma B, Kumar M: The prevalence of intestinal parasitic infestation and the related profile of the CD4 (+) counts in HIV/AIDS people with diarrhoea in Jaipur City. JCDR. 2013, 7 (3): 454-456.

KSR K, K L R: Intestinal Cryptosporidiosis and the profile of the CD4 counts in a cohort of HIV infected patients. Journal of clinical and diagnostic research. JCDR. 2013, 7 (6): 1016-1020.

Miao YM, Awad-El-Kariem FM, Franzen C, Ellis DS, Müller A, Counihan HM, Hayes PJ, Gazzard BG: Eradication of cryptosporidia and microsporidia following successful antiretroviral therapy. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2000, 25 (2): 124-129. 10.1097/00126334-200010010-00006.

Adamu H, Petros B: Intestinal protozoan infections among HIV positive persons with and without Antiretroviral Treatment (ART) in selected ART centers in Adama, Afar and Dire-Dawa Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Dev. 2009, 23 (2): 133-140.

Bangsberg DR, Perry S, Charlebois ED, Clark RA, Roberston M, Zolopa AR, Moss A: Non-adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy predicts progression to AIDS. AIDS. 2001, 15 (9): 1181-1183. 10.1097/00002030-200106150-00015.

Abrogoua DP, Kablan BJ, Kamenan BAT, Aulagner G, N'guessan K, Zohoré C: Assessment of the impact of adherence and other predictors during HAART on various CD4 cell responses in resource-limited settings. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2012, 6: 227-237.

Herrmann S, McKinnon E, John M, Hyland N, Martinez OP, Cain A, Turner K, Coombs A, Manolikos C, Mallal : Evidence-based, multifactorial approach to addressing non-adherence to antiretroviral therapy and improving standards of care. Intern Med J. 2008, 38 (1): 8-15.

Amberbir A, Woldemichael K, Getachew S, Girma B, Deribe K: Predictors of adherence to antiretroviral therapy among HIV-infected persons: a prospective study in Southwest Ethiopia. BMC Public Health. 2008, 8: 265-10.1186/1471-2458-8-265.

Kurniawan A, Dwintasari SW, Connelly L, Nichols RAB, Yunihastuti E, Karyadi T, Djauzi S: Cryptosporidium species from human immunodeficiency-infected patients with chronic diarrhea in Jakarta, Indonesia. Ann Epidemiol. 2013, 23 (11): 720-3. 10.1016/j.annepidem.2013.07.019.

Alemu A, Shiferaw Y, Getnet G, Yalew A, Addis Z: Opportunistic and other intestinal parasites among HIV/AIDS patients attending Gambi higher clinic in Bahir Dar city, North West Ethiopia. Asian Pacific J Trop Med. 2011, 4 (8): 661-665. 10.1016/S1995-7645(11)60168-5.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2334/14/100/prepub

Acknowledgement

The study was funded by AAU, Biology Department Graduate Study. The authors are grateful to the parasitology laboratory staff of EHNRI (especially Mr. Hussein Mohamed) and Yirgalem Hospital for their collaboration in sample collection/analysis.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

MG designed the study, collected both the field and lab data, and involved in the analysis and manuscript preparation. The original research was the requirement for his MSc in biomedical sciences/parasitology; BP and TE were primary thesis advisors. TE also involved in the manuscript preparation, WT reanalyzed the data and involved in the preparation of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Girma, M., Teshome, W., Petros, B. et al. Cryptosporidiosis and Isosporiasis among HIV-positive individuals in south Ethiopia: a cross sectional study. BMC Infect Dis 14, 100 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2334-14-100

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2334-14-100