Abstract

Background

Our aim was to investigate the aortic distensibility (AD) of the ascending aorta and carotid artery intima-media thickness (c-IMT) in HIV-infected patients compared to healthy controls.

Methods

One hundred and five HIV-infected patients (86 males [82%], mean age 41 ± 0.92 years), and 124 age and sex matched HIV-1 uninfected controls (104 males [84%], mean age 39.2 ± 1.03 years) were evaluated by high-resolution ultrasonography to determine AD and c-IMT. For all patients and controls clinical and laboratory factors associated with atherosclerosis were recorded.

Results

HIV- infected patients had reduced AD compared to controls: 2.2 ± 0.01 vs. 2.62 ± 0.01 10-6 cm2 dyn-1, respectively (p < 0.001). No difference was found in c-IMT between the two groups. In multiadjusted analysis, HIV infection was independently associated with decreased distensibility (beta –0.45, p < 0.001). Analysis among HIV-infected patients showed that patients exposed to HAART had decreased AD compared to HAART-naïve patients [mean (SD): 2.18(0.02) vs. 2.28(0.03) 10-6 cm2 dyn-1, p = 0.01]. In multiadjusted analysis, increasing age and exposure to HAART were independently associated with decreased AD.

Conclusion

HIV infection is independently associated with decreased distensibility of the ascending aorta, a marker of subclinical atherosclerosis. Increasing age and duration of exposure to HAART are factors further contributing to decreased AD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

The use of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) resulted in a significant decrease in morbidity and mortality in patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection [1], turning this lethal infection to a chronic ambulatory disease. However, the initial optimism has been tempered when it became evident that HAART has metabolic side effects such as fat redistribution, dyslipidemia, insulin resistance, glucose intolerance, metabolic syndrome, and overt diabetes; all of them are established risk factors for atherosclerosis and cardiovascular disease [2–5]. Indeed, soon after the introduction of HAART into the clinical practice, researchers reported unexpected vascular events among young patients. A large prospective study confirmed that HAART, especially the protease inhibitor (PI)–containing regimens, increases the risk for cardio- and cerebro-vascular events in HIV-infected persons [6]. This finding suggests that HAART causes early atherosclerosis [7, 8]. The observed excess cardiovascular risk cannot be attributed solely to the side effects of antiretroviral drugs since chronic HIV infection itself has a role, as it has been shown for other chronic inflammatory diseases [9]. Moreover, HAART increased life expectancy and as HIV seropositive population ages, chronic diseases like atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease become increasingly important [10, 11].

It is difficult to dissect relative contributions of conventional cardiovascular risk factors, metabolic side effects of antiretroviral drugs, and HIV infection itself on early atherosclerosis and cardiovascular events, as these factors frequently co-exist in the same patient. Moreover, studies using clinical endpoints to investigate cardiovascular outcomes in patients with HIV infection, who typically are young or middle-aged, need large numbers of patients because of the low event rate. Therefore, studies using surrogate markers for early atherosclerosis are required.

Researchers have reported that the reduction of the elastic properties of aorta represents an early stage in the atherosclerotic process [12–16]. Aortic distensibility (AD) is an elasticity index of the ascending aorta, and along with carotid artery intima-media thickness (c-IMT) are simple and reproducible markers of subclinical arteriosclerotic disease and have been identified as strong predictors of cardiovascular mortality in different clinical settings [17–24]. There are no studies for early atherosclerosis of ascending aorta among HIV-infected patients. The aim of this study was to investigate the distensibility of the ascending aorta and c-IMT in HIV-infected patients compared with age and sex matched uninfected controls, and to investigate whether HIV infection itself, conventional risk factors for atherosclerosis, and/or HAART are associated with early atherosclerosis.

Methods

We enrolled in the study a total of 105 consecutive, HIV-infected patients attending the outpatient clinic of the Athens Laikon Hospital. Controls were 124 healthy volunteers recruited from hospital staff, as well as their relatives or friends. HIV infection was ruled out in controls by serologic testing with their consent. Control subjects were individually matched with patients by age (± 5 years) and sex.

Demographic and clinical data such as age, sex, body weight, arterial blood pressure, and history of smoking were obtained from all patients and control subjects, as well as blood samples for laboratory measurements, including blood count, glucose, total cholesterol, triglyceride, high density lipoprotein (HDL), low-density-lipoprotein (LDL) and creatinine levels. Hypertriglyceridemia and hypercholesterolemia were defined as triglyceride and cholesterol level equal or more than 150 and 200 mg/dl, respectively. Hypertension was defined as systolic and diastolic blood pressure level above 140mmHg and 90mmHg, respectively. Moreover, for each HIV-infected patient the following information corresponding to the sampling time point was recorded: risk group, disease duration, CDC stage, CD4 cell count, viral load, and HAART. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Laikon General Hospital, Athens, Greece. All participants gave their informed consent.

All HIV-infected patients and seronegative controls were evaluated to determine c-IMT and AD. Visualization of the carotid artery was obtained via high resolution, B-mode carotid artery ultaronography, and c-IMT was measured by the same investigator. Measurement of c-IMT was performed in the common carotid artery, of both left and right side, 1cm proximal to carotid bulb and at least three separate measurements of each side were obtained according to previous recommendations [25]. Abnormal c-IMT was defined as a value of equal or more than 0.9 mm. AD was determined noninvasively based on the relationship between changes in aortic diameter and pressure with each cardiac pulse [26, 27]. The echocardiographic study was carried out using a Hewlett Packard Sonos 1000 ultrasound system (Hewlett Packard), using a 2·5-MHz transducer. Each subject was placed in the mild left recumbent position and the ascending aorta was recorded at a level 3 cm above the aortic valve in the M-mode tracings guided by the two-dimensional echocardiogram in the parasternal long axis view [26]. Internal aortic diameters were measured by means of a caliper in systole and diastole as the distance between the trailing edge of the anterior aortic wall and the leading edge of the posterior aortic wall. Systolic aortic diameter was measured as the maximal anterior motion of the aorta and diastolic diameter at the peak of the QRS complex on the simultaneously recorded electrocardiogram. Ten consecutive cardiac beats were measured routinely and averaged [26, 27]. Blood pressure was measured with a Dinamap TM XL vital signs monitor (Johnson-Johnson, Arlington, VA). AD was calculated according to the formula [26, 28]:

Where ΔD is the change of the aortic diameter between systole and diastole, Dd is the aortic diameter in diastole, Ps is the systolic arterial blood pressure and Pd is the diastolic arterial blood pressure. The cardiologist who performed the measurements (IM) was blind of the results of the autonomic function tests of the examined subjects. The intraobserver and interobserver mean percentage error (absolute difference between two observations divided by the mean and expressed as percentage) was determined for the aortic dimensions in 20 randomly selected subjects and were 4.2% and 4.6% for the systolic and 4.1% and 4.4% for the diastolic dimensions in our centre, respectively.

Statistical analysis

STATA package v8 (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX, USA) was used for data analysis. Continuous variables are presented as mean ± SD, and compared using the t-test. Dichotomous variables are presented as frequency (%) and compared using the chi-square test. For HIV-infected patients vs. controls comparison, a multiadjusted analysis for AD (dependent variable) which was the major outcome was performed using the linear regression technique and all significant variables of the univariate analysis entered the model as independent covariates.

In a second step, a univariate and multivariate linear regression (using a stepwise, backward selection technique) were performed in HIV-positive group only to identify influential factors for AD. A two-sided P-value <0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Results

Characteristics of the study population

The study population consisted of 105 HIV seropositive patients (86 male [82%]) with mean age ± SD, 41 ± 0.92 years and 124 control subjects (104 male [84%] with mean age 39.2 ± 1.03 years. Sixty out of the 105 HIV-infected patients (57%) had acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) and 89 of them (85%) were receiving HAART. Patients’ clinical characteristics are shown on Table 1. The prevalence of dislipidemia was higher among HIV-infected patients, as they had higher fasting plasma concentrations of total cholesterol (p < 0.001), triglycerides (p < 0.001) and LDL (p = 0.08) and lower concentrations of HDL (p < 0.001), compared to HIV- seronegative controls. On the contrary, the prevalence of obesity [Body mass index (BMI) > 30 kg/m2] was significantly higher in control subjects than in HIV-infected patients (p < 0.001). The mean arterial pressure was higher among controls regarding both systolic and diastolic arterial pressure (p < 0.001); hypertension was statistically more frequent in controls than in HIV-infected patients [13, (10.5%) vs. 1, (1%), respectively, p = 0.003] (Table 2).

Distensibility of the ascending aorta and HIV infection in the whole study population

We first compared HIV-infected patients with controls using t-test. AD was statistically lower in patients’ population than in uninfected controls: 2.2 ± 0.01 vs. 2.62 ± 0.01 10-6 cm2 dyn-1, respectively (p < 0.001) (Table 2). Nevertheless, no difference was found in c-IMT between the two groups.

In multiadjusted analysis, after adjustment for all significant confounders, HIV infection was independently associated with decreased distensibility (beta –0.45, p < 0.001) (Table 3). Other factors associated with decreased AD were, as expected, obesity and increasing diastolic pressure.

Distensibility of the ascending aorta in HIV-infected patients

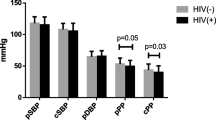

A separate analysis was performed within the group of HIV-infected patients. Patients exposed to HAART had decreased distensibility of the ascending aorta compared to HAART-naïve patients [mean (SD): 2.18(0.02) vs. 2.28(0.03), p = 0.01]. In multivariate linear regression analysis only increasing age and cumulative duration of exposure to HAART were independently associated with decreased AD (Table 4). Based on the previous model, Figure 1 shows the effect of HAART therapy on the distensibility of the ascending aorta, stratified for age > =40 years vs. <40 years.

Discussion

The main findings of our study were that HIV-infected patients had significantly reduced distensibility of the ascending aorta compared to age and sex matched control subjects. On the contrary, no difference in c-IMT was observed between the two groups. Multiadjusted analysis showed that after adjustment for conventional cardiovascular risk factors HIV infection was independently associated with decreased AD. Among HIV-infected patients, those exposed to HAART had significantly decreased AD compared to HAART-naïve patients. In multivariate analysis, increasing age and duration of HAART exposure were factors independently associated with decreased AD. Moreover, the effect of HAART on the distensibility was more pronounced among patients older than 40 years old (Figure 1).

The reduced distensibility of the ascending aorta that we found among HIV-infected patients compared to uninfected controls is a marker of subclinical arteriosclerotic disease and has been identified as a strong predictor of cardiovascular mortality in different clinical settings [17–21]. In a large population study, AD was inversely related to conventional cardiovascular disease risk factors, such as older age, hypertension, smoking, and low HDL-cholesterol levels [29]. In accordance, in our study multiadjusted analysis showed that vascular risk factors such as obesity, and increasing diastolic pressure were also important for decreased distensibility of the ascending aorta. It is interesting that we found decreased distensibility among HIV-infected patients despite the fact that obesity and blood pressure were significantly higher among controls. One explanation could be that dislipidemia was statistically more frequent among HIV-infected patients, due to the HAART side effects or to the chronic infection per se.

Multi-adjusted analysis showed that after correction for other vascular risk factors, HIV infection was independently associated with decreased AD. In fact, premature atherosclerosis has been reported in young adults with HIV infection in the pre–HAART era [30]. The cardiovascular disease risk associated with HIV infection appears to be partially attenuated by antiretroviral treatment, since treatment interruption increases short-term risk of cardiovascular disease events [11]. These findings suggest that HIV infection itself may increase the risk for cardiovascular disease, as it has been shown for other chronic inflammatory diseases [9] in the non-HIV setting. Many markers of inflammation are markedly elevated in individuals with untreated HIV infection and are only partially reversed by effective combination antiretroviral therapy [31].

Our data are consistent with previous studies showing that HIV infection per se, as well as HAART is associated with increased stiffness [30, 32–36] of peripheral arteries (femoral and branchial) and the carotid artery. Interestingly, recent investigations have shown that biological and vascular age in HIV infected patients is increased [37, 38]. Our study did not find increased c-IMT in HIV-infected patients compared to uninfected controls. Conflicting evidence exists in the bibliography on the c-IMT: some studies reported increased c-IMT in HIV- infected patients compared with HIV-negative controls [30, 33, 39–44] but others did not [45–48]. It is noteworthy that our HIV-infected population had decreased distensibility of the ascending aorta and a normal c-IMT. This may imply that there are differences in the effect of HIV along the arterial system and reduced AD is an earlier marker of subclinical atherosclerosis compared to c-IMT. An alternative explanation could be that although arterial stiffening is thought to be a generalized phenomenon, different arterial segments are known to respond differently to atherosclerotic risk factors [49–51].

Our study showed that among HIV-infected patients, increasing age and longer exposure to HAART contribute further to decreased distensibility of the ascending aorta. Moreover, the effect of HAART on the AD was more pronounced among patients older than 40 years old. While increasing age is a well known risk for atherosclerosis, the effect of HAART on accelerating atherosclerosis remains controversial. Chronic HIV infection may lead to vascular endothelial damage and damage the elastic properties of an artery by sustaining a low degree of inflammation [52]. HAART has beneficial effects by reducing the inflammation due to active HIV infection, and detrimental effects such as dyslipidemia. Although it is difficult to determine the net effect in an individual patient and in different arterial segments, a recent study showed that endothelial dysfunction actually improved after start of HAART despite the rapid onset of dyslipidemia [53]. Our study had not enough statistical power to detect if PI containing regimens had different effect on the AD compared to NNRTI-containing regimens.

Our study has some limitations. Aortic diameters were measured echocardiographically and not invasively. A previous study has shown that aortic diameter can be determined with a high degree of accuracy in subjects whose cardiothoracic anatomy permits an echocardiographic signal of satisfactory quality, and the values obtained by echocardiography were not significantly different from those obtained by angiography [26]. In addition, pulse pressure estimated non-invasively from the brachial artery by external sphygmomanometry has been used for the calculation of AD in previous reports [26, 54–56]. These non-invasive techniques have also been used for calculating AD in previous studies [55–57]. Thus a reliable estimation of the elastic properties of the ascending aorta using completely non-invasive techniques is feasible. Another limitation was the very high proportion of male subjects included in the cohort, which could limit the generalization of results to female HIV-infected patients. Moreover, the potential impact of past/active drug abuse could not be reliably evaluated, as only 3 patients (3%) had a history of drug abuse.

Conclusions

HIV infection is independently associated with decreased distensibility of the ascending aorta, a marker of premature atherosclerosis. This suggests that patients with HIV infection may be at increased cardiovascular disease risk, independent of the presence of classical cardiovascular risk factors. Study of arterial elasticity as early marker of vascular damage could be promising and more appropriate investigation in HIV people than evaluation of cIMT.

References

Sterne JA, Hernán MA, Ledergerber B, Tilling K, Weber R, Sendi P, et al: Swiss HIV Cohort Study. Long-term effectiveness of potent antiretroviral therapy in preventing AIDS and death: a prospective cohort study. Lancet. 2005, 366: 378-384.

Riddler SA, Li X, Chu H, Kingsley LA, Dobs A, Evans R, et al: Longitudinal changes in serum lipids among HIV-infected men on highly active antiretroviral therapy. HIV Med. 2007, 8: 280-287.

Calza L, Manfredi R, Chiodo F: Dyslipidaemia associated with antiretroviral therapy in HIV-infected patients. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2004, 53: 10-

Riddler SA, Smit E, Cole SR, Li R, Chmiel JS, Dobs A, et al: Impact of HIV infection and HAART on serum lipids in men. JAMA. 2003, 289: 2978-2982.

Morse CG, Kovacs JA: Metabolic and skeletal complications of HIV infection: the price of success. JAMA. 2006, 296: 844-854.

d'Arminio A, Sabin CA, Phillips AN, Reiss P, Weber R, Kirk O, et al: Writing Committee of the D:A:D: Study Group. Cardio- and cerebrovascular events in HIV-infected persons. AIDS. 2004, 18: 1811-1817.

Friis-Møller N, Reiss P, Sabin CA, Weber R, Monforte A, El-Sadr W, DAD Study Group: Class of antiretroviral drugs and the risk of myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2007, 356: 1723-1735.

Sabin CA, Worm SW, Weber R, Reiss P, El-Sadr W, Dabis F, D:A:D Study Group: Use of nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors and risk of myocardial infarction in HIV-infected patients enrolled in the DAD study: a multi-cohort collaboration. Lancet. 2008, 371: 1417-1426.

Roman MJ, Devereux RB, Schwartz JE, Lockshin MD, Paget SA, Davis A, et al: Arterial stiffness in chronic inflammatory diseases. Hypertension. 2005, 46: 194-199.

Currier JS: Update on cardiovascular complications in HIV infection. Top HIV Med. 2009, 17: 98-103.

Martínez E, Larrousse M, Gatell JM: Cardiovascular disease and HIV infection: host, virus, or drugs?. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2009, 22: 28-34.

Willum-Hansen T, Staessen JA, Torp-Pedersen C, Rasmussen S, Thijs L, Ibsen H, et al: Prognostic value of aortic pulse wave velocity as index of arterial stiffness in the general population. Circulation. 2006, 113: 664-670.

Shokawa T, Imazu M, Yamamoto H, Toyofuku M, Tasaki N, Okimoto T, et al: Pulse wave velocity predicts cardiovascular mortality: findings from the Hawaii-Los Angeles-Hiroshima study. Circ J. 2005, 69: 259-264.

Laurent S, Boutouyrie P, Asmar R, Gautier I, Laloux B, Guize L, et al: Aortic stiffness is an independent predictor of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in hypertensive patients. Hypertension. 2001, 37: 1236-1241.

Sutton-Tyrrell K, Najjar SS, Boudreau RM, Venkitachalam L, Kupelian V, Simonsick EM, et al: Health ABC Study. Elevated aortic pulse wave velocity, a marker of arterial stiffness, predicts cardiovascular events in well-functioning older adults. Circulation. 2005, 111: 3384-3390.

Mattace-Raso FU, van der Cammen TJ, Hofman A, van Popele NM, Bos ML, Schalekamp MA, et al: Arterial stiffness and risk of coronary heart disease and stroke: the Rotterdam Study. Circulation. 2006, 113: 657-663.

Moyssakis I, Gialafos E, Vassiliou VA, Boki K, Votteas V, Sfikakis PP, et al: Myocardial performance and aortic elasticity are impaired in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Scand J Rheumatol. 2009, 38: 216-221.

Moyssakis I, Gialafos E, Tentolouris N, Floudas CS, Papaioannou TG, Kostopoulos C, et al: Impaired aortic elastic properties in patients with systemic sarcoidosis. Eur J Clin Invest. 2008, 38: 82-89.

Moyssakis I, Gialafos E, Vassiliou V, Taktikou E, Katsiari C, Papadopoulos DP, et al: Aortic stiffness in systemic sclerosis is increased independently of the extent of skin involvement. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2005, 44: 251-254.

Margos PN, Moyssakis IE, Tzioufas AG, Zintzaras E, Moutsopoulos HM: Impaired elastic properties of ascending aorta in patients with giant cell arteritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005, 64: 253-256.

Tentolouris N, Liatis S, Moyssakis I, Tsapogas P, Psallas M, Diakoumopoulou E, et al: Aortic distensibility is reduced in subjects with type 2 diabetes and cardiac autonomic neuropathy. Eur J Clin Invest. 2003, 33: 1075-1083.

Bots ML, Hoes AW, Koudstaal PJ, Hofman A, Grobbee DE: Common carotid intima-media thickness and risk of stroke and myocardial infarction: the Rotterdam Study. Circulation. 1997, 96: 1432-1437.

Lorenz MW, von Kegler S, Steinmetz H, Markus HS, Sitzer M: Carotid intima-media thickening indicates a higher vascular risk across a wide age range: prospective data from the Carotid Atherosclerosis Progression Study (CAPS). Stroke. 2006, 37: 87-92.

O'Leary DH, Polak JF, Kronmal RA, Manolio TA, Burke GL, Wolfson SK: Carotid-artery intima and media thickness as a risk factor for myocardial infarction and stroke in older adults. Cardiovascular Health Study Collaborative Research Group. N Engl J Med. 1999, 340: 14-22.

Stein JH, Korcarz CE, Hurst RT, Lonn E, Kendall CB, Mohler ER, et al: American Society of Echocardiography Carotid Intima-Media Thickness Task Force. Use of carotid ultrasound to identify subclinical vascular disease and evaluate cardiovascular disease risk: a consensus statement from the American Society of Echocardiography Carotid Intima-Media Thickness Task Force. Endorsed by the Society for Vascular Medicine. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2008, 21: 93-111.

Stefanadis C, Stratos C, Boudoulas H, Kourouklis C, Toutouzas P: Distensibility of the ascending aorta: comparison of invasive and non-invasive techniques in healthy men and in men with arterial disease. Eur Heart J. 1990, 11: 990-996.

Stefanadis C, Dernellis J, Vlachopoulos C, Tsioufis C, Tsiamis E, Toutouzas K, et al: Aortic function in arterial hypertension determined by pressure-diameter relation: effects of diltiazem. Circulation. 1997, 96: 1853-1858.

Boudoulas H, Wooley CF: Aortic function. Functional abnormalities of the aorta. Edited by: Toutouzas PK, Wooley CF. 1996, Futura Publishing Co. Inc, Armonk, NY, 3-36.

Malayeri AA, Natori S, Bahrami H, Bertoni AG, Kronmal R, Lima JA, et al: Relation of aortic wall thickness and distensibility to cardiovascular risk factors (from the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis [MESA]). Am J Cardiol. 2008, 102: 491-496.

van Vonderen MG, Smulders YM, Stehouwer CD, Danner SA, Gundy CM, Vos F, et al: Carotid intima-media thickness and arterial stiffness in HIV-infected patients: the role of HIV, antiretroviral therapy, and lipodystrophy. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009, 50: 153-161.

Kaplan RC, Sinclair E, Landay AL, Lurain N, Sharrett AR, Gange SJ, et al: T cell activation and senescence predict subclinical carotid artery disease in HIV-infected women. J Infect Dis. 2011, 203: 452-463.

Seaberg EC, Benning L, Sharrett AR, Lazar JM, Hodis HN, Mack WJ, et al: Association between human immunodeficiency virus infection and stiffness of the common carotid artery. Stroke. 2010, 41: 2163-2170.

van Vonderen MG, Hassink EA, van Agtmael MA, Stehouwer CD, Danner SA, Reiss P, et al: Increase in carotid artery intima-media thickness and arterial stiffness but improvement in several markers of endothelial function after initiation of antiretroviral therapy. J Infect Dis. 2009, 199: 1186-1194.

Baker JV, Duprez D, Rapkin J, Hullsiek KH, Quick H, Grimm R, Neaton JD, Henry K, et al: Untreated HIV infection and large and small artery elasticity. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009, 52: 25-31.

Schillaci G, De Socio GV, Pirro M, Savarese G, Mannarino MR, Baldelli F, Stagni G, Mannarino E, et al: Impact of treatment with protease inhibitors on aortic stiffness in adult patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005, 25: 2381-2385.

Schillaci G, De Socio GV, Pucci G, Mannarino MR, Helou J, Pirro M, Mannarino E, et al: Aortic stiffness in untreated adult patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection. Hypertension. 2008, 52: 308-313.

Guaraldi G, Zona S, Alexopoulos N, Orlando G, Carli F, Ligabue G, et al: Coronary aging in HIV-infected patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2009, 49: 1756-1762.

De Socio GV, Ricci E, Parruti G, Maggi P, Madeddu G, Quirino T, Bonfanti P, et al: Chronological and biological age in HIV infection. J Infect. 2010, 61: 428-430.

Ross AC, Storer N, O'Riordan MA, Dogra V, McComsey GA: Longitudinal changes in carotid intima-media thickness and cardiovascular risk factors in human immunodeficiency virus-infected children and young adults compared with healthy controls. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2010, 29: 634-638.

Vigano A, Bedogni G, Cerini C, Meroni L, Giacomet V, Stucchi S, et al: Both HIV-infection and long-term antiretroviral therapy are associated with increased common carotid intima-media thickness in HIV-infected adolescents and young adults. Curr HIV Res. 2010, 8: 411-417.

Hsue PY, Hunt PW, Schnell A, Kalapus SC, Hoh R, Ganz P, et al: Role of viral replication, antiretroviral therapy, and immunodeficiency in HIV-associated atherosclerosis. AIDS. 2009, 23: 1059-1067.

Oliviero U, Bonadies G, Apuzzi V, Foggia M, Bosso G, Nappa S, et al: Human immunodeficiency virus per se exerts atherogenic effects. Atherosclerosis. 2009, 204: 586-589.

Lorenz MW, Stephan C, Harmjanz A, Staszewski S, Buehler A, Bickel M, et al: Both long-term HIV infection and highly active antiretroviral therapy are independent risk factors for early carotid atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis. 2008, 196: 720-726.

Hsue PY, Lo JC, Franklin A, Bolger AF, Martin JN, Deeks SG, et al: Progression of atherosclerosis as assessed by carotid intima-media thickness in patients with HIV infection. Circulation. 2004, 109: 1603-1608.

Bonnet D, Aggoun Y, Szezepanski I, Bellal N, Blanche S: Arterial stiffness and endothelial dysfunction in HIV-infected children. AIDS. 2004, 18: 1037-1041.

Currier JS, Kendall MA, Zackin R, Henry WK, Alston-Smith B, Torriani FJ, AACTG 5078 Study Team: Carotid artery intima-media thickness and HIV infection: traditional risk factors overshadow impact of protease inhibitor exposure. AIDS. 2005, 19: 927-933.

Currier JS, Kendall MA, Henry WK, Alston-Smith B, Torriani FJ, Tebas P, et al: Progression of carotid artery intima-media thickening in HIV-infected and uninfected adults. AIDS. 2007, 21: 1137-1145.

Mercié P, Thiébaut R, Lavignolle V, Pellegrin JL, Yvorra-Vives MC, Morlat P, et al: Evaluation of cardiovascular risk factors in HIV-1 infected patients using carotid intima-media thickness measurement. Ann Med. 2002, 34: 55-63.

Henry RM, Kostense PJ, Spijkerman AM, Dekker JM, Nijpels G, Heine RJ, et al: Arterial stiffness increases with deteriorating glucose tolerance status: the Hoorn Study. Circulation. 2003, 107: 2089-2095.

van der Heijden-Spek JJ, Staessen JA, Fagard RH, Hoeks AP, Boudier HA, van Bortel LM: Effect of age on brachial artery wall properties differs from the aorta and is gender dependent: a population study. Hypertension. 2000, 35: 637-642.

Ferreira I, Henry RM, Twisk JW, van Mechelen W, Kemper HC, Stehouwer CD: The metabolic syndrome, cardiopulmonary fitness, and subcutaneous trunk fat as independent determinants of arterial stiffness: the Amsterdam Growth and Health Longitudinal Study. Arch Intern Med. 2005, 165: 875-882.

Fisher SD, Miller TL, Lipshultz SE: Impact of HIV and highly active antiretroviral therapy on leukocyte adhesion molecules, arterial inflammation, dyslipidemia, and atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis. 2006, 185: 1-11.

Torriani F: Antiretroviral therapy improves endothelial function in treatment-naive HIV infected patients: a prospective, randomized multicenter trial (A5152s. 2005, EACS, Dublin, Presented at

Gatzka CD, Cameron JD, Kingwell BA, Dart AM: Relation between coronary artery disease, aortic stiffness, and left ventricular structure in a population sample. Hypertension. 1998, 32: 575-578.

Dart AM, Lacombe F, Yeoh JK, Cameron JD, Jennings GL, Laufer E, et al: Aortic distensibility in patients with isolated hypercholesterolaemia, coronary artery disease, or cardiac transplant. Lancet. 1991, 338: 270-273.

Eren M, Gorgulu S, Uslu N, Celik S, Dagdeviren B, Tezel T: Relation between aortic stiffness and left ventricular diastolic function in patients with hypertension, diabetes or both. Heart. 2004, 90: 37-43.

Lacombe F, Dart A, Dewar E, Jennings G, Cameron J, Laufer E: Arterial elastic properties in man: a comparison of echo-Doppler indices of aortic stiffness. Eur Heart J. 1992, 13: 1040-1045.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2334/12/167/prepub

Acknowledgments

NVS acknowledges support by the Special Account of Research Funds (ELKE) of the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

AZ and NVS designed the study and drafted the study protocol with input from TK. SPG and MNG collected the data with input from ANK. IM performed the ultrasound measurements and contributed in the interpretation of data. PDZ conducted the data analysis. AZ and NVS wrote the manuscript. TK revised the final draft. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Zormpala, A., Sipsas, N.V., Moyssakis, I. et al. Impaired distensibility of ascending aorta in patients with HIV infection. BMC Infect Dis 12, 167 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2334-12-167

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2334-12-167