Abstract

Background

The assessment of Health Related Quality of Life (HRQL) is important in people with dementia as it could influence their care and support plan. Many studies on dementia do not specifically set out to measure dementia-specific HRQL but do include related items. The aim of this study is to explore the distribution of HRQL by functional and socio-demographic variables in a population-based setting.

Methods

Domains of DEMQOL’s conceptual framework were mapped in the Cambridge City over 75’s Cohort (CC75C) Study. HRQL was estimated in 110 participants aged 80+ years with a confirmed diagnosis of dementia with mild/moderate severity. Acceptability (missing values and normality of the total score), internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha), convergent, discriminant and known group differences validity (Spearman correlations, Wilcoxon Mann-Whitney and Kruskal-Wallis tests) were assessed. The distribution of HRQL by socio-demographic and functional descriptors was explored.

Results

The HRQL score ranged from 0 to 16 and showed an internal consistency Alpha of 0.74. Validity of the instrument was found to be acceptable. Men had higher HRQL than women. Marital status had a greater effect on HRQL for men than it did for women. The HRQL of those with good self-reported health was higher than those with fair/poor self-reported health. HRQL was not associated with dementia severity.

Conclusions

To our knowledge this is the first study to examine the distribution of dementia-specific HRQL in a population sample of the very old. We have mapped an existing conceptual framework of dementia specific HRQL onto an existing study and demonstrated the feasibility of this approach. Findings in this study suggest that whereas there is big emphasis in dementia severity, characteristics such as gender should be taken into account when assessing and implementing programmes to improve HRQL.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Dementia is the most common disorder of old age [1, 2] and a leading cause of mortality and disability in high income countries [3]. Medications temporarily relieve symptoms for some individuals, but do not modify the overall course of the disease, [4]. Narrow assessment of cognition and functional ability is insufficient for clinical decision-making and policy development as they only reflect a part of the impact of dementia [5]. Dementia can also have a significant impact on quality of live (QoL). Indeed, treatment is increasingly focused on improving or maintaining optimal QoL and this has become a key outcome for evaluating the effectiveness of dementia interventions [5–7].

Health-related quality of life (HRQL) can be defined as an individual’s perception of the impact of a health condition on their everyday life [8]. HRQL differs from the broader concept of QoL in that it includes only aspects of QoL that are affected by a health condition. Despite the lack of agreement on what domains constitute HRQL, it is generally agreed that the concept is multidimensional and subjective and that any assessment should include measurement of positive and negative dimensions [9–12]. There have been many efforts to capture HRQL in dementia including generic and dementia-specific HRQL measures. Generic HRQL measures are not tailored to people with dementia [13, 14]. Such measures focus on health and function and imply that HRQL will automatically decrease with disease progression. Some generic measures (e.g., Nottingham Health Profile [15], Duke Health Profile [16]) have been found to lack evidence on validity or reliability in dementia populations [17]. A recent recent systematic review on HRQL in dementia found that there are at least 15 different dementia specific HRQL scales [18]. Some of the most widely used include: the Quality of Life in Alzheimer’s Disease (QoL-AD) [19], Alzheimer’s Disease Related Quality of Life (ADRQL) [13], QUALIDEM [20], Quality Of Life Assessment Schedule (QOLAS) [21] and the DEMQOL [22]. Each of these measures a wide range of dimensions and their use has been found to be beneficial within a clinical framework. However, there are limitations with each. For example, while the QoL-AD has been validated in numerous countries it includes items on functioning and cognition implying that HRQL will decrease automatically with disease progression. The ADRQL can obtain both total and subscale scores. However it is a proxy-rated only measure and therefore is not the most suitable measure for use in individuals with mild-moderate dementia. The same applies to the QUALIDEM. In the QOLAS scale, while the subdomains are chosen by the patient, making this one of the most suitable measures for clinical practice, this limits its utility for research purposes since the concept of HRQL is intrinsic to the person. The DEQMOL’s conceptual framework was developed by literature review and interviews with people with dementia and their carers. There is a self and a proxy-rated version. However, in a clinical sample, factor analysis showed a lack of dimensionality. Lastly, a limitation of all scales is that none has been validated in a population-based sample.

Although research on HRQL has increased in the last decade, there is still limited evidence on how it is affected by dementia [23]. Knowledge of this is necessary to measure the impact of early diagnosis, access to treatment and effective planning of care. To our knowledge no study has assessed HRQL with dementia-specific measures in a population-based setting. While many population studies focused on dementia do not specifically set out to measure dementia-specific HRQL, they do include related items such as mood or social support. Mapping measures of HRQL in such studies is important for determining the distribution of HRQL and its risk factors in the dementia population. Therefore, the aim of this study was to explore the distribution of HRQL by functional and socio-demographic variables, mapped using items of the DEMQOL scale, using data from the Cambridge City over 75s Cohort (CC75C).

Methods

Sample and design

Participants were from the CC75C study, a population-based longitudinal cohort study representative of Cambridge’s (UK) older people. Full details of the methodology has been described elsewhere [24] and can be found online at can be found on line at http://www.cc75c.group.cam.ac.uk/. The baseline survey enrolled 95% (n = 2610) of individuals aged 75 years and older, approached from six general practices in Cambridge in 1985/87. Participants were followed with surveys repeated at two (Survey 2), seven (Survey 3), ten (Survey 4), 13 (Survey 5), 17 (Survey 6) and 21 years (Survey 7). Interviews were conducted with the study participants and a proxy informant if the participant was unable to complete the interview. Proxy informants were usually relatives but could sometimes be a friend/neighbour or a warden or member of staff in a care home. Observations by the interviewer were also gathered during the course of the interviews. Core data included information on socio-demographic variables (e.g. place of residence, household structure, marital status and social contact), activities of daily living (ADLs), use of health and social services, cognitive function (e.g., Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) [25]), health problems and medication. This data except for HRQL and cognitive assessments was retrieved from the caregivers if necessary. The interview schedule has undergone slight revisions with the addition of new sections, such as questions on affect and loneliness added in survey 3 and 4. Survey 3, conducted in the 7th year of follow up, was the first survey that best represented all the DEMQOL domains, with questions including socio-demographic information, social relationships, mood, loneliness, anxiety, depression, ADLs and cognitive functioning. Therefore data from Survey 3 will be used in this analysis.

Dementia diagnosis

Dementia was diagnosed using a two-stage approach. At baseline, individuals who scored ≤ 23 on the MMSE, and one in three individuals with a MMSE score of 24 or 25, were assessed using the Cambridge Mental Disorders of the Elderly Examination (CAMDEX) [26], a structured schedule specifically designed to detect mild dementia. Between the baseline interview and survey 3, six assessments for dementia were conducted. Based on the CAMDEX results, different dementia types were assessed including: Alzheimer’s disease (AD), vascular dementia (VaD), mixed (AD and VaD), dementia secondary to other causes, clouded/delirious state plus AD and clouded/delirious state plus VaD. Dementia diagnoses were also sought by checking death certificates for any mention of dementia as a cause of death and checking reports from interviews with relatives for the sub-sample of participants who donated their brains to research. No additional people with dementia were identified. For the present study, participants with a last diagnosis of dementia, from any CAMDEX assessment and MMSE score > 10 (n = 110, 40 men and 70 women aged 80-99) up until one year after Survey 3 were identified for inclusion in this analysis. Among those without a MMSE score, 2 people were diagnosed with minimal, 2 with mild and 2 with moderate dementia using the CAMDEX. The staging of dementia was calculated using cut-offs on the MMSE as follows: 11–20 = moderate; 21 and above = mild [27].

Assessment of socio-demographic and functional ability

Socio-demographic variables included age (continuous), gender, marital status (currently married, widowed, separated/divorced, and never married), education (up to 14 years of age and 15 and above) and accommodation (house, warden controlled housing, residential home and long stay hospital). Functional disability included impairment in basic and instrumental ADLs (IADLs). Individuals were categorised into three groups based on their pattern of impairment including: (1) IADL disability only if they required help with cooking, housework or both; (2) ADL + IADL disability if they needed help with any of four basic ADL tasks including: bathing, dressing, getting to the toilet on time and grooming; or, (3) No ADL/IADL disability.

Questionnaire mapping and development

In this study we chose to map the DEMQOL framework as it includes the domains that have been most commonly assessed in dementia-specific HRQL measures, namely daily activities/looking after yourself, health and well-being, cognitive functioning, social relationships, and self-concept. Further, the conceptual framework underpinning the DEMQOL was developed in in the UK. Using data obtained at Survey 3, the following subdomains of the DEMQOL framework could be mapped including: health and well-being, social relationships, self-concept and items from daily activities corresponding to enjoyment of activities. Only self-reported information was used to assess HRQL. Due to the high percentage of missing responses to HRQL items in the most cognitively impaired participants, only those with a MMSE score above 10 were included in the study, as has been suggested previously [28–30].

Table 1 shows the DEMQOL conceptual framework and the subdomains that could be mapped in the CC75C study. After mapping, 18 items were included. After applying existing criteria for missing data analysis, inter-item correlations and endorsement frequencies analysis [22], two of these items were removed, giving a scale ranging from 0 to 16 with 0 being the lowest and 16 the highest scores.

Analysis

The psychometric properties of the final version of the questionnaire (16 items) were tested with the sample of 110 people with dementia identified as described above. Standard psychometric methods were used [31] to evaluate acceptability, reliability (internal consistency) and validity (content, convergent, discriminant and known group differences). Criteria for acceptability were: missing data for summary scores <5% and normality of the distribution of the total score (Skewness measured with Shapiro-Francia, Shapiro-Wilk and Skewness test with a p value higher than 0.05 indicating normality). Criteria for internal consistency were Cronbach’s alpha ≥0.7. Convergent and discriminant validity were measured with Spearman correlations (r). Convergent validity is the evidence that the scale is correlated with other measures of the same or similar constructs and was deemed acceptable when r was 0.20 and higher. Discriminant validity is the evidence that the scale is not correlated with measures of different constructs and was deemed acceptable when r was below 0.20. Known group differences refer to the ability of a scale to differentiate groups who are expected to differ on the construct being measured. Differences in HRQL scores by socio-demographic, functional and measures of disability and cognition were tested using the Wilcoxon Mann-Whitney tests (variables with two groups) and Kruskal-Wallis test (variables with more than two groups). Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. A meta-analytical review was conducted in order to generate a priori hypotheses as part as the validity assessment of the measure used. This has been annexed as a separate report (Additional file 1) as a separate report. We used factor analysis to evaluate hypothesised subscales based on the conceptual framework. All analyses were performed using Stata 11 [32].

Ethics approval and consent

Each CC75C study phase was approved by Cambridge Research Ethics Committee and National Research Ethics Service Committee East of England- Cambridge Central (Reference numbers: 05_Q0108_308 and 08_H0308_3).

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. For those deemed to lack capacity to give fully informed consent, and those unable to give consent in writing for reasons of physical disability, both the study participant’s clear assent to be interviewed and written proxy informed consent from a relative or caregiver well known to the participant were attained.

Results

Description of sample

A description of the sample can be found in Table 2. Out of the 713 people who took part in Survey 3, there were 134 people with a dementia diagnosis. From these, we excluded n = 24 with MMSE scores 0-10. Diagnoses included Alzheimer’s disease (69.1%), vascular dementia (3.6%), mixed dementia (22.7%) and other dementia (4.6%). Age ranged from 81 to 99 years (mean age 86.6, SD 3.6), 63.6% were women and 29.1% of the sample left school at age 15 or later. A high percentage of the sample lived in a house or flat (70.9%), 16.4% lived in warden controlled sheltered housing and 11.8% in a residential home. Most participants were widowed (77.1%), with less than a quarter of the sample (23.6%) married. In terms of disability 31.8% had no ADL/IADL disability, 30.9% had only IADL disability and 36.4% had both. A higher percentage of women with dementia had both ADL and IADL disability compared to men (44.3% vs. 22.5%). Scores on the MMSE scores ranged from 11 to 30 (mean MMSE 21.3, SD 4.8). Dementia severity was rated mild for 60% of the sample and 40% had moderate dementia. A high percentage of patients (78.2%) rated their health as good or very good.

Results from mapping

We were able to map all the DEMQOL domains except for those that are dementia symptoms (cognition and ADLs except for enjoyment of activities). One out of seven subdomains of self-esteem, nine out of eighteen of health and well-being, three out of eight of social relationships and one out of fifteen of daily activities (one out of four of enjoyment of activities) were mapped onto the CC75C study.

Psychometric evaluation

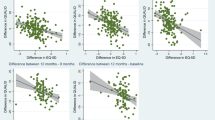

Table 3 shows the psychometric properties of the HRQL scale assessed [31]. Regarding acceptability, missing data was below the criteria of 5% (2.73%). Shapiro-Francia, Shapiro-Wilk and Skewness test indicated that the distribution of HRQL was skewed. The HRQL questionnaire shows acceptable internal consistency reliability (α = 0.73). Regarding convergent validity, correlations with cognition measured with the MMSE as a continuous variable and disability were not significant (r = 0.059, p = 0.55 and r = -0.08, p = 0.40). HRQL was not associated with age (r = -0.048, p = 0.62) indicating acceptable discriminant validity. Regarding known groups validity the HRQL score showed the predicted pattern amongst a priori known groups regarding sex and self-perceived health. Men had higher HRQL compared to women (z = 1.958, p = 0.05). Those who rated their health as being good or very good had higher HRQL than those who rated it as fair or poor (z = -2.428, p = 0.02). There were no significant differences in HRQL score according to education and marital status. Factor analysis did not support subscales. Factor analysis of the instrument suggested a one-factor model (only one factor with eigenvalues above 1 accounting for 22% of the variance).

Distribution of HRQL by socio-demographic and functional variables

Tables 4 and 5 show the distribution of HRQL in the CC75C sample. HRQL in the presence of dementia does not vary by age. Men have higher HRQL than women. HRQL is higher in the 81-84 and 85-89 groups than the 90+ in men, being almost constant in women. The median HRQL score does not vary by education or type of accommodation. Married people with dementia and those that were never married have higher HRQL than their widowed counterparts. The median score does not differ much in women but it does in men, being higher in married men compared to widowers and women in general. Those with only IADL disability have better HRQL than those with no disability and those with more severe disability (including ADLs). The HRQL of those with good self-reported health is higher than those with fair/poor self-reported health. HRQL does not vary with cognition. Within those that left school before age 15, the median score is similar in those with mild and moderate severity. However, within those who left school at age 15 or later, HRQL was lower in those with moderate than those with mild dementia severity. As an additional analysis, we calculated the association between sex and severity of depression measured with the CAMDEX (the higher the score the higher the severity) using the Kruskal-Wallis equality-of-populations rank test. Men’s rank sum was 1885.5 and women’s was 4219.5 (p = 0.038).

Discussion

We have assessed the distribution of HRQL in very old individuals with mild to moderate dementia, a section of the population with whom it is hard to conduct this kind of research. Marital status, sex, education and self-rated health seem to be the most important variables related to HRQL. Dementia severity does not seem to be associated with HRQL in dementia.

Strengths

There are a number of strengths in the approach we have taken. Firstly, this is a population-based sample of older old adults with dementia. The study also includes both people with dementia living in the community and institutionalised populations. The present study did not specifically set out to measure dementia-specific HRQL. However, we have been able to maximise its value by mapping most dimensions of the DEMQOL onto this project and studying the distribution of HRQL in a representative sample of the Cambridge population over 80 years old with dementia. One of the strengths of the DEMQOL conceptual framework is that it was developed using a combination of interviews with people with mild to severe dementia and their non-professional caregivers, and a review of the literature and existing instruments. The adapted version of the DEMQOL using the CC75C study questions has been shown to have acceptable psychometric properties suggesting that this scale fulfils standard criteria for acceptability, good internal consistency, and validity, namely content validity, discriminant validity and to some extent, known group differences. These properties have been tested in a population sample, providing therefore evidence of external validity of this instrument. Something no other dementia-specific measure has proved yet [18]. Another strength of our instrument is the breadth of dimensions measured compared to dimension-specific instruments such as the Progressive deteriorations Scale (PDS) [33] or a number of other dementia-specific HRQL measures [34–38].

Weaknesses

Several limitations need to be taken into account when analysing these results. The sample used in this study was derived from several phases of a longitudinal cohort investigating HRQL in people with dementia. The use of this data may therefore result in a number of biases in the research, for example survival bias in which there might have been a selection of people with factors associated to survival or follow up such as gender, education or setting, may lead to some unrepresentative distributions of HRQL. Cognitive bias may also be affecting the results of this study given the lack of insight of people with dementia [39]. However evidence suggests that people with mild to moderate dementia are able to assess their HRQL [22, 28, 40, 41]. There are other limitations, principally arising from the methodology of exploring HRQL, previously un-researched in this sample in which HRQL had not been assessed using existing dementia-specific measures. Firstly, since the instrument has been designed a posteriori, the question stems, response options and time frame of the questions were not identical to those from the DEMQOL framework. A limitation of our instrument compared to other instruments such as the ADRQL [13], QUALIDEM [20] or DEMQOL proxy [22] is that HRQL in people with severe dementia could not be analysed given the high percentage of missing values and the lack of proxy ratings for HRQL items. Compared to the original DEMQOL [22] and Bath Assessment of Subjective Quality of Life in Dementia (BASQID) [42] our instrument did not include items on worry/satisfaction with cognition and activities of daily living. Regarding the psychometric properties, some aspects such as test-retest reliability could not be evaluated due to the study design. Causality in the associations between HRQL and covariates cannot be inferred in this study, as it is cross-sectional. Finally, the distribution by ethnicity, medication or relationship with the caregiver could not be explored. These variables have been shown to be associated in previous studies [29, 43].

Summary of distribution of HRQL

Age was not associated with HRQL, a finding consistent with previous literature [42, 44–47]. Findings such as the lower HRQL in men with dementia who are 90 years of age and older compared to younger groups may be due to differential mortality between gender [48]. The oldest age group is likely to have worst health than the other two age groups. The established relationship between married state and higher HRQL in men is found for men with dementia too. This could be related to social support mechanisms given one of the primary benefits of marriage for men is social connectedness [49]. According to the sex role hypothesis, this positive effect of marriage would not affect women because of the ungratifying nature of housework (usually conducted by women) and women’s primary responsibility for household chores [50, 51]. This lack of effect of marriage in women and the high percentage of widowed women and married men could account for the higher HRQL of men. The finding that men have higher HRQL than women could also indicate that women had higher levels of, for example depression and anxiety, as occurs in the general population [52, 53]. In fact we have found that in our sample, women have higher levels of depression than men. This finding is consistent with what is observed in clinical practice when offering support to relatives of patients with Alzheimer’s disease, and could also be related to the greater difficulties women face in terms of continuing to perform the tasks associated with their role in the family and generational context [46]. Similar results have been reported in other populations [54–56].

HRQL did not vary by levels of cognition and its association with disability is not clear. There is increasing evidence that severity of dementia may not be a major determinant of HRQL in dementia, indicating that it is possible to have good life quality at all levels of dementia severity [22, 23, 40, 57]. This finding casts doubts on the usefulness of interventions only aimed at improving or maintaining cognition and function in order to improve the quality of life of the patient with dementia. However, there is also evidence pointing at the decreased awareness of their cognitive impairments and change of behaviour by patients with dementia [58]. This also manifests as poor awareness of deficits in ADL. In general, awareness of deficits seems to decrease with an increased severity of dementia [39, 59]. This could account for the lack of association between severity and HRQL. In fact, people with moderate dementia severity who left school after age 14 had a very low HRQL score compared to those with the same level of education but higher cognition and to those who left school before that age. This may reflect that this group are more conscious of their limitations in relation to more intellectual tasks, e.g. reading for pleasure, than people with less formal education, who may be less troubled by such impairments. This could also be related with the cognitive reserve hypothesis [60]. There is evidence showing that high cognitive reserve groups have a higher cognitive decline but later [61, 62]. A systematic review, found cognitive decline to be associated to HRQL [23]. Patients with high reserve and moderate dementia might be more worried about the sudden decline of their functioning compared to the other groups.

Finally, higher HRQL in those with good self-rated health compared with people with lower self-rated health has also been previously reported [47]. Whereas it is plausible that health itself may be related to HRQL, the subjective nature of the rating of both concepts and the inclusion of a similar item as part of the concept of HRQL may partly explain this association.

Future directions

Many population-based studies on dementia exist. None of them set out to measure dementia-specific HRQL. However, a number of these studies include variables that could be used to map a dementia-specific HRQL framework into the study. Doing so would be a useful way of maximising already existing resources and allow comparison across populations and provide valuable information for policy development.

Conclusion

To our knowledge this is the first study that has mapped an existing conceptual framework of dementia-specific HRQL onto an existing study that did not aim at measuring it, thereby describing HRQL in an under-researched section of the population of increasing clinical importance. These results have practical implications for public health policies and dementia care. They emphasise the need for taking gender into account when assessing and implementing programmes to improve HRQL. According to the present findings, improving social support and modifying sex roles that can decrease HRQL when affected by dementia such as women’s family tasks will be key in these programmes.

References

Ferri CP, Prince M, Brayne C, Brodaty H, Fratiglioni L, Ganguli M, Hall K, Hasegawa K, Hendrie H, Huang Y, Jorm A, Mathers C, Menezes PR, Rimmer E, Scazufca M: Global prevalence of dementia: a Delphi consensus study. Lancet. 2005, 366: 2112-2117.

Marengoni A, Winblad B, Karp A, Fratiglioni L: Prevalence of chronic diseases and multimorbidity among the elderly population in Sweden. Am J Public Health. 2008, 98: 1198-1200. 10.2105/AJPH.2007.121137.

Lopez AD, Mathers CD, Ezzati M, Jamison DT, Murray CJL: Global and regional burden of disease and risk factors, 2001: systematic analysis of population health data. Lancet. 2006, 367: 1747-1757. 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68770-9.

World Health Organization: Dementia: A Public Health Priority. 2012, Geneva: World Health Organization

Whitehouse PJ: Harmonization of dementia drug guidelines (United States and Europe): a report of the international working group for the harmonization for dementia drug guidelines. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2000, 14 Suppl 1: S119-S122.

Small GW, Rabins PV, Barry PP, Buckholtz NS, DeKosky ST, Ferris SH, Finkel SI, Gwyther LP, Khachaturian ZS, Lebowitz BD, McRae TD, Morris JC, Oakley F, Schneider LS, Streim JE, Sunderland T, Teri LA, Tune LE: Diagnosis and treatment of Alzheimer disease and related disorders. Consensus statement of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry, the Alzheimer’s Association, and the American Geriatrics Society. JAMA. 1997, 278: 1363-1371. 10.1001/jama.1997.03550160083043.

Moniz-Cook E, Vernooij-Dassen M, Woods R, Verhey F, Chattat R, De Vugt M, Mountain G, O’Connell M, Harrison J, Vasse E, Dröes RM, Orrell M: A European consensus on outcome measures for psychosocial intervention research in dementia care. Aging Ment Health. 2008, 12: 14-29. 10.1080/13607860801919850.

Bullinger M, Anderson R, Cella D, Aaronson N: Developing and evaluating cross-cultural instruments from minimum requirements to optimal models. Qual Life Res. 1993, 2: 451-459. 10.1007/BF00422219.

Lawton MP: Quality of life in Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 1994, 8: 138-150.

The WHOQOL Group: The World Health Organization Quality of Life asessment (WHOQOL): position paper from the World Health Organization. Soc Sci Med. 1995, 41: 1403-1409.

Brown J, Bowling A, Flynn T: Models of Quality of Life: A Taxonomy, Overview and Systematic Review of the Literature. 2004

Ready RE: Measuring quality of life in dementia. Qual. Life Meas. Neurodegener. Relat. Cond. Edited by: Jenkinson C, Michele P, Bromber MB. 2011, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 82-94.

Rabins PV, Kasper JD, Kleinman L, Black BS: Concepts and methods in the development of the ADRQL: an instrument of assessing health-related quality of life in persons with Alzheimer’s disease. J Ment Health Aging. 1999, 5: 33-48.

Silberfeld M, Rueda S, Krahn M, Naglie G: Content validity for dementia of three generic preference based health related quality of life instruments. Qual Life Res. 2002, 11: 71-79. 10.1023/A:1014406429385.

Bureau-Chalot F, Novella JL, Jolly D, Ankri J, Guillemin F, Blanchard F: Feasibility, acceptability and internal consistency reliability of the nottingham health profile in dementia patients. Gerontology. 2002, 48: 220-225. 10.1159/000058354.

Novella JL, Jochum C, Jolly D, Morrone I, Bureau JAF, Blanchard F: Agreement between patients’ and proxies’ reports of quality of life in Alzheimer’ s disease. Qual Life Res. 2012, 10: 443-452.

Ettema TP, Dröes R-M, de Lange J, Mellenbergh GJ, Ribbe MW: A review of quality of life instruments used in dementia. Qual Life Res. 2005, 14: 675-686. 10.1007/s11136-004-1258-0.

Perales J, Cosco TD, Stephan BCM, Haro JM, Brayne C: Health-related quality-of-life instruments for Alzheimer’s disease and mixed dementia. Int Psychogeriatr. 2013, 25 (5): 691-706. 10.1017/S1041610212002293.

Logsdon RG, Gibbons LE, McCurry SM, Teri L: Quality of life in Alzheimer’s disease: patient and caregiver reports. J Ment Health Aging. 1999, 5: 21-32.

Ettema TP, Droes R-M, de Lange J, Mellenbergh GJ, Ribbe MW: QUALIDEM: development and evaluation of a dementia specific quality of life instrument – validation. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007, 22: 424-430. 10.1002/gps.1692.

Selai CE, Trimble MR, Rossor MN, Harvey RJ: Assessing quality of life in dementia: preliminary psychometric testing of the Quality of Life Assessment Schedule (QOLAS). Neuropsychol Rehabil. 2001, 11: 219-243. 10.1080/09602010042000033.

Smith S, Lamping D, Banerjee S, Harwood R, Foley B, Smith P, Cook J, Murray J, Prince M, Levin E, Mann A, Knapp M: Measurement of health-related quality of life for people with dementia: development of a new instrument (DEMQOL) and an evaluation of current methodology. Health Technol Assess. 2005, 9: 1-93.

Banerjee S, Samsi K, Petrie CD, Alvir J, Treglia M, Schwam EM, Valle M: What do we know about quality of life in dementia? A review of the emerging evidence on the predictive and explanatory value of disease specific measures of health related quality of life in people with dementia. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009, 24: 15-24. 10.1002/gps.2090.

Fleming J, Zhao E, O’Connor DW, Pollitt PA, Brayne C: Cohort profile: the Cambridge City over-75s Cohort (CC75C). Int J Epidemiol. 2007, 36: 40-46. 10.1093/ije/dyl293.

Folstein M, Folstein S: Mini-mental state: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975, 12: 189-198. 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6.

Roth M, Tym E, Mountjoy CQ, Huppert FA, Hendrie H, Verma S, Goddard R: CAMDEX. A standardised instrument for the diagnosis of mental disorder in the elderly with special reference to the early detection of dementia. Br J Psychiatry. 1986, 149: 698-709. 10.1192/bjp.149.6.698.

Mega MS, Cummings JL, Fiorello T, Gornbein J: The spectrum of behavioral changes in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 1996, 46: 130-135. 10.1212/WNL.46.1.130.

Logsdon RG, Gibbons LE, McCurry SM, Teri L: Assessing quality of life in older adults with cognitive impairment. Psychosom Med. 2002, 64: 510-519.

James BD, Xie SX, Karlawish JHT: How do patients with Alzheimer disease rate their overall quality of life?. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005, 13: 484-490. 10.1097/00019442-200506000-00007.

Thorgrimsen L, Selwood A, Spector A, Royan L, de Madariaga Lopez M, Woods RT, Orrell M: Whose quality of life is it anyway?. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2003, 17: 201-208. 10.1097/00002093-200310000-00002.

Lamping DL, Schroter S, Marquis P, Marrel A, Duprat-Lomon I, Sagnier P-P: The community-acquired pneumonia symptom questionnaire: a new, patient-based outcome measure to evaluate symptoms in patients with community-acquired pneumonia. Chest. 2002, 122: 920-929. 10.1378/chest.122.3.920.

StataCorp: Stata: release 11. Stat Softw. 2009

DeJong R, Osterlund OW, Roy GW: Measurement of quality-of-life changes in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Clin Ther. 1989, 11: 545-554.

Ready RE, Ott BR, Grace J, Fernandez I: The Cornell-Brown scale for quality of life in dementia. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2002, 16: 109-115. 10.1097/00002093-200204000-00008.

Salek M, Walker M, Bayer A: The community dementia quality of life profile (CDQLP): a factor analysis. Qual Life Res. 1999, 8: 660-

Albert SM, Del Castillo-Castaneda C, Sano M, Jacobs DM, Marder K, Bell K, Bylsma F, Lafleche G, Brandt J, Albert M, Stern Y: Quality of life in patients with Alzheimer’ s disease as reported by patient proxies. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1996, 44: 1-12.

Porzsolt F, Kojer M, Schmidl M, Greimel ER, Sigle J, Richter J, Eisemann M: A new instrument to describe indicators of well-being in old-old patients with severe dementia–the Vienna List. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2004, 2: 10-10.1186/1477-7525-2-10.

Fossey J, Lee L, Ballard C: Dementia care mapping as a research tool for measuring quality of life in care settings: psychometric properties. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2002, 17: 1064-1070. 10.1002/gps.708.

Aalten P, Van Valen E, De Vugt ME, Lousberg R, Jolles J, Verhey FRJ: Awareness and behavioral problems in dementia patients: a prospective study. Int Psychogeriatr. 2006, 18: 3-17. 10.1017/S1041610205002772.

Brod M, Stewart AL, Sands L, Walton P: Conceptualization and measurement of quality of life in dementia: the dementia quality of life instrument (DQoL). Gerontologist. 1999, 39: 25-35. 10.1093/geront/39.1.25.

Mozley CG, Huxley P, Sutcliffe C, Bagley H, Burns A, Challis D, Cordingley L: ‘Not knowing where I am doesn’t mean I don’t know what I like’: cognitive impairment and quality of life. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1999, 14: 776-783. 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1166(199909)14:9<776::AID-GPS13>3.0.CO;2-C.

Trigg R, Skevington S, Jones R: How can we best assess the quality of life of people with dementia? The Bath Assessment of Subjective Quality of Life in Dementia (BASQID). Gerontologist. 2007, 47: 789-797. 10.1093/geront/47.6.789.

Mougias AA, Politis A, Lyketsos CG, Mavreas VG: Quality of life in dementia patients in Athens, Greece: predictive factors and the role of caregiver-related factors. Int Psychogeriatr. 2011, 23: 395-403. 10.1017/S1041610210001262.

Chan IW-P, Chu L-W, Lee PWH, Li S-W, Yu K-K: Effects of cognitive function and depressive mood on the quality of life in Chinese Alzheimer’s disease patients in Hong Kong. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2011, 11: 69-76. 10.1111/j.1447-0594.2010.00643.x.

Fuh J-L, Wang S-J: Assessing quality of life in Taiwanese patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006, 21: 103-107. 10.1002/gps.1425.

Conde-Sala JL, Garre-Olmo J, Turro-Garriga O, Lopez-Pousa S, Vilalta-Franch J: Factors related to perceived quality of life in patients with Alzheimer’s disease: the patient’s perception compared with that of caregivers. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009, 24: 585-594. 10.1002/gps.2161.

Lucas-Carrasco R, Lamping DL, Banerjee S, Rejas J, Smith SC, Gómez-Benito J: Validation of the Spanish version of the DEMQOL system. Int Psychogeriatr. 2010, 22: 589-597. 10.1017/S1041610210000207.

Raleigh VS, Kiri VA: Life expectancy in England: variations and trends by gender, health authority, and level of deprivation. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1997, 51: 649-658. 10.1136/jech.51.6.649.

Umberson D, Wortman C, Kessler R: Widowhood and depression: explaining long-term gender differences in vulnerability. J Health Soc Behav. 1992, 33: 10-24. 10.2307/2136854.

Gove W, Tudor J: Adult sex roles and mental illness. Am J Sociol. 1978, 78: 812-835.

Kessler RC, McRae JA: Trends in the relationship between sex and psychological distress: 1957-1976. Am Sociol Rev. 1981, 46: 443-452. 10.2307/2095263.

Regier DA, Farmer ME, Rae DS, Myers JK, Kramer M, Robins LN, George LK, Karno M, Locke BZ: One-month prevalence of mental disorders in the United States and sociodemographic characteristics: the Epidemiologic Catchment Area study. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1993, 88: 35-47.

Copeland JR, Beekman AT, Dewey ME, Hooijer C, Jordan A, Lawlor BA, Lobo A, Magnusson H, Mann AH, Meller I, Prince MJ, Reischies F, Turrina C, DeVries MW, Wilson KC: Depression in Europe. Geographical distribution among older people. Br J Psychiatry. 1999, 174: 312-321. 10.1192/bjp.174.4.312.

Belloch A, Perpiñá M, Martínez-Moragón E, De Diego A, Martínez-Francés M: Gender differences in health-related quality of life among asthma patients. J Asthma. 2003, 40: 189-199. 10.1081/JAS-120017990.

Koch CG, Khandwala F, Cywinski JB, Ishwaran H, Estafanous FG, Loop FD, Blackstone EH: Health-related quality of life after coronary artery bypass grafting: a gender analysis using the Duke Activity Status Index. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2004, 128: 284-295. 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2003.12.033.

Hsu H: Gender differences in health-related quality of life among the elderly in Taiwan. Asian J Heal Inf Sci. 2007, 1: 366-376.

Banerjee S, Smith S, Lamping D, Harwood R, Foley B, Smith P, Murray J, Prince M, Levin E, Mann A, Knapp M: Quality of life in dementia: more than just cognition. An analysis of associations with quality of life in dementia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2006, 77: 146-148. 10.1136/jnnp.2005.072983.

Riepe MW, Mittendorf T, Förstl H, Frölich L, Haupt M, Leidl R, Vauth C, von der Schulenburg MG: Quality of life as an outcome in Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias- obstacles and goals. BMC Neurol. 2009, 9: 47-10.1186/1471-2377-9-47.

Starkstein SE, Jorge R, Mizrahi R, Robinson RG: A diagnostic formulation for anosognosia in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2006, 77: 719-725. 10.1136/jnnp.2005.085373.

Stern Y: Cognitive reserve. Neuropsychologia. 2009, 47: 2015-2028. 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2009.03.004.

Teri L, McCurry SM, Edland SD, Kukull WA, Larson EB: Cognitive decline in Alzheimer’s disease: a longitudinal investigation of risk factors for accelerated decline. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1995, 50A: M49-M55. 10.1093/gerona/50A.1.M49.

Stern Y, Albert S, Tang MX, Tsai WY: Rate of memory decline in AD is related to education and occupation: cognitive reserve?. Neurology. 1999, 53: 1942-1947. 10.1212/WNL.53.9.1942.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2318/14/18/prepub

Acknowledgements

JP is grateful to the Instituto de Salud Carlos III for a predoctoral grant (PFIS) and to the Mendeley reference manager developers. We gratefully acknowledge the contributions of previous investigators and past research team members (see http://www.cc75c.group.cam.ac.uk/pages/studypersonnel), collaborating general practitioners and their practice teams, and, most particularly, the study respondents, their families and friends, and the staff in many care homes. Especial thanks to Sally Hunter, Emily Zhao, Eugene Paykel and Tom Dening for providing valuable comments to improve the paper. We thank all the past CC75C sponsors for financial support spanning two decades (see http://www.cc75c.group.cam.ac.uk for full list of project grants) most recently the BUPA Foundation for support under their Health and Care of Older People grant. Current CC75C research is in association with the NIHR CLAHRC (National Institute for Health Research Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research & Care) for Cambridgeshire and Peterborough.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

JP conducted the data analysis and wrote the paper. TDC, BCMS, JF, SM and JMH assisted with writing the paper. CB supervised the data analysis and development of the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Perales, J., Cosco, T.D., Stephan, B.C. et al. Health-related quality of life in the Cambridge City over-75s Cohort (CC75C): development of a dementia-specific scale and descriptive analyses. BMC Geriatr 14, 18 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2318-14-18

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2318-14-18