Abstract

Background

Hyperplastic polyps are the most common polypoid lesions of the stomach. Rarely, they cause gastric outlet obstruction by prolapsing through the pyloric channel, when they arise in the prepyloric antrum.

Case presentation

A 62-year-old woman presented with intermittent nausea and vomiting of 4 months duration. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy revealed a 30 mm prepyloric sessile polyp causing intermittent gastric outlet obstruction. Following submucosal injection of diluted adrenaline solution, the polyp was removed with a snare. Multiple biopsies were taken from the greater curvature of the antrum and the corpus. Rapid urease test for Helicobacter pylori yielded a negative result. Histopathologic examination showed a hyperplastic polyp without any evidence of malignancy. Biopsies of the antrum and the corpus revealed gastritis with neither atrophic changes nor Helicobacter pylori infection. Follow-up endoscopy after a 12-week course of proton pomp inhibitor therapy showed a complete healing without any remnant tissue at the polypectomy site. The patient has been symptom-free during 8 months of follow-up.

Conclusions

Symptomatic gastric polyps should be removed preferentially when they are detected at the initial diagnostic endoscopy. Polypectomy not only provides tissue to determine the exact histopathologic type of the polyp, but also achieves radical treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Gastric outlet obstruction (GOO) presents with nausea and vomiting and usually develops over weeks to months [1]. It may be complete or incomplete with intermittent symptoms. In the past, peptic ulcer disease was considered as the most common cause of GOO; more recently, gastric malignancy has become a more frequent entity [2]. The rare causes are bezoars, foreign bodies, Bouveret's syndrome, hypertrophic pyloric stenosis, and large polyps of the antrum or pyloric channel [3–6].

Gastric polyps are incidentally detected in 2–3% of upper gastrointestinal endoscopic examinations [7]. The most common type of gastric polyps is hyperplastic polyps, which account for nearly 85–90% of cases [7, 8]. They are usually seen in adults, over 60 years of age [8]. These polyps are often pinkish, round-shaped, solitary, and small (<2 cm) and classified as either sessile or pedunculated. While small polyps tend to be sessile, the larger ones may have a short stalk [8]. Most of them are localized at the junction of fundic and pyloric mucosa. Multiple hyperplastic polyps are found in 20% of the patients [9].

Until recently it was believed that the hyperplastic polyps do not undergo malignant transformation, but carcinomas associated with hyperplastic polyps were reported in the literature over the past few years [10, 11]. Interestingly, an association between hyperplastic polyps and Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) gastritis has been proposed in some recent studies [12, 13].

In this report, we present a patient who had a gastric hyperplastic polyp causing GOO and a review of the pertinent literature.

Case presentation

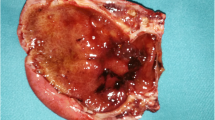

A 62-year-old woman (A.K., #5202) applied to our institute with complaints of nausea and vomiting. She described four episodes of similar type, each lasting 2 to 3 days, in the last 4 months. Her medical background and family history were unremarkable and physical examination was normal. The standard laboratory results (whole blood count, glucose, blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, electrolytes, prothrombin time, and partial thromboplastin time) were also within normal limits. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy revealed a 30 mm prepyloric sessile polyp covered with normal mucosa and which partially obstructed the entrance of the pyloric channel Figure 1A. The patient's gastric outlet obstruction was ascribed to this pathology and a polypectomy was carried out in the same session. The polyp was slightly elevated by submucosal injection of diluted adrenaline solution (0.0125 mg/mL in saline) targeted at 4 points around the base Figure 1B. The polyp was removed with a snare and diathermy was used at a level of 40 watts Figure 1C. Two biopsies were taken from both the antrum and the corpus for rapid urease test. Four samples from each sites of the greater curvature of the antrum and the corpus were also taken to assess any atrophy, intestinal metaplasia or gastritis. Rapid urease test for H. pylori yielded a negative result. Histopathologic examination of the polypectomy specimen showed a hyperplastic polyp without any malignant features Figure 2. Biopsies of the antrum and the corpus revealed gastritis with no evidence of atrophic changes or intestinal metaplasia. H. pylori was not observed by either Hematoxylin and Eosin or modified Giemsa stains. Follow-up endoscopy after a 12-week course of proton pomp inhibitor (PPI) therapy showed a complete healing of the polypectomy site with no remnant tissue related to the polyp Figure 3. The patient has been symptom-free during 8 months of follow-up.

Conclusions

Most hyperplastic polyps are usually small (< 2 cm); however, larger polyps may seldom be encountered on endoscopic examinations. Larger the size of the polyps, higher is the risk of the complications such as obstruction or bleeding. Rarely, hyperplastic polyps may cause dramatic clinical pictures. De La Cruz et al. [14] reported a patient with a hyperplastic polyp that caused pancreatitis by prolapsing into the duodenum and compressing the Vater ampulla. Alper et al. [6] showed that a large pedunculated antral hyperplastic polyp may cause gastric outlet obstruction and iron deficiency anemia by prolapsing into the duodenum through the pyloric channel. More frequent use of gastroscopic examinations resulted in an increase of incidental diagnosis of hyperplastic polyps. Although it has been widely accepted that every symptomatic polyp should be removed either endoscopically or surgically, there is no particular guideline regarding the evaluation and treatment of asymptomatic hyperplastic polyps.

The exact pathogenesis of hyperplastic polyps is still unclear. The current theory is that an exaggerated regenerative response to mucosal damage occurs [8]. They may be found in association with various forms of chronic gastritis, notably with autoimmune or H. pylori gastritis [9]. Abraham et al. [9] investigated 160 patients with hyperplastic polyps and found that 85% of the cases had an associated inflammatory mucosal pathology, mostly H. pylori gastritis. Not only inflammatory changes, but also malignant foci in other parts of the gastric mucosa may be detected in patients with hyperplastic polyps. Accordingly, taking biopsies from the remote gastric mucosa in order to evaluate any inflammatory changes or malignant transformation has been advocated [15].

There is still a debate on whether H. pylori promotes the development of hyperplastic polyps. In a series of 21 patients with gastric hyperplastic polyp, H. pylori was positive in 76% of the patients [12]. However, in another larger series, 85% (136/160) of the patients had inflammatory mucosal pathology, most commonly active chronic H. pylori gastritis (25%) [9]. On the other hand, Varis et al. [16] investigated the presence of H. pylori in patients with different types of gastric polyps and reported the prevalence of H. pylori infection significantly lower in patients with hyperplastic polyps (45%) and foveolar hyperplasia (48%) than in the group with inflammatory polyps (81%). As an interesting observation, Ohkusa et al. [13] showed that hyperplastic polyps disappeared after eradication of H. pylori in most patients with H. pylori associated gastritis. Similarly, Ljubicic et al. [12] reported a 40% complete regression rate of hyperplastic polyps in patients who had associated H. pylori gastritis after an average follow-up of 14 months. In both trials, endoscopic polypectomy has been recommended as the second-line approach in the management of hyperplastic polyps associated with H. pylori gastritis, when eradication therapy fails to achieve complete polyp regression [12, 13]. However, this approach has not been unanimously accepted. The policy in our institute is to remove single polyps of any diameter regardless whether the patient has or not associated H. pylori gastritis. When there are multiple polyps, the strategy is determined by the results of H. pylori urease test: if negative, all the polyps are removed; but if positive, polyps larger than 15 mm in diameter are removed whereas sampling polypectomy and eradication therapy are offered to the smaller ones. Then, these patients are submitted to endoscopic surveillance.

Contrary to the previous belief, recent studies have revealed that hyperplastic polyps may include dysplastic foci and even undergo malignant degeneration [10, 11]. Hizawa et al. [11] reported the incidence of malignancy in the hyperplastic polyps as 2%.

In summary, symptomatic gastric polyps presenting as the case above should be removed preferentially when they are detected at the initial diagnostic endoscopy. Polypectomy not only provides tissue to determine the exact histopathologic type of the polyp, but also achieves radical treatment. The same strategy can be used for asymptomatic polyps, where biopsy samples may yield inconclusive results by sampling error. Evidence now is in favour of polypectomy even though the histopathologic examination shows that these are hyperplastic polyps. Additionally, in patients with gastric polyps, other parts of the gastric mucosa should also be histologically evaluated by multiple biopsies for detection of any accompanying inflammatory changes or malignancy. After polypectomy, endoscopic follow-up can be recommended, because of the possibility of recurrence at the polypectomy site and of development of malignancy in the remote gastric mucosa.

Abbreviations

- GOO:

-

Gastric Outlet Obstruction

- H. pylori :

-

Helicobacter pylori

- PPI:

-

Proton Pump Inhibitor

References

Livingston EH: Stomach and duodenum. In Surgery: Basic Science and Clinical Evidence. Edited by: Norton JA, Bollinger RR, Chang AE, Lowry SF, Mulvihill SJ, Pass HI, Thompson RW. 2000, New York: Springer-Verlag, 489-515.

Jaffin BW, Kaye MD: The prognosis of gastric outlet obstruction. Ann Surg. 1985, 201: 176-179.

Malvaux P, Degolla R, De Saint-Hubert M, Farchakh E, Hauters P: Laparoscopic treatment of a gastric outlet obstruction caused by a gallstone (Bouveret's syndrome). Surg Endosc. 2002, 16: 1108-1109. 10.1007/s004640042033.

Gencosmanoglu R, Sad O, Sav A, Tozun N: Primary hypertrophic pyloric stenosis in the adult: a case report. Turkish J Gastroenterol. 2002, 13: 175-179.

Dean PG, Davis PM, Nascimento AG, Farley DR: Hyperplastic gastric polyp causing progressive gastric outlet obstruction. Mayo Clin Proc. 1998, 73: 964-967.

Alper M, Akcan Y, Belenli O: Large pedinculated antral hyperplastic gastric polyp traversed the bulbus causing outlet obstruction and iron deficiency anemia: endoscopic removal. World J Gastroenterol. 2003, 9: 633-634.

Silverstein FE, Tytgat GNJ: Stomach II: Tumors and polyps. In Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. Edited by: Silverstein FE, Tytgat GNJ. 1997, London: Mosby, 147-180.

Owen DA: The stomach. In Diagnostic Surgical Pathology. Edited by: Sternberg SS. 1999, Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 1311-1347.

Abraham SC, Singh VK, Yardley JH, Wu TT: Hyperplastic polyps of the stomach: associations with histologic patterns of gastritis and gastric atrophy. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001, 25: 500-507. 10.1097/00000478-200104000-00010.

Orlowska J, Kupryjanczyk J: Malignant transformation of gastric hyperplastic polyps. Am J Clin Pathol. 2002, 117: 165-166.

Hizawa K, Fuchigami T, Iida M, Aoyagi K, Iwashita A, Daimaru Y, Fujishima M: Possible neoplastic transformation within gastric hyperplastic polyp. Application of endoscopic polypectomy. Surg Endosc. 1995, 9: 714-718.

Ljubicic N, Banic M, Kujundzic M, Antic Z, Vrkljan M, Kovacevic I, Hrabar D, Doko M, Zovak M, Mihatov S: The effect of eradicating Helicobacter pylori infection on the course of adenomatous and hyperplastic gastric polyps. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1999, 11: 727-730.

Ohkusa T, Takashimizu I, Fujiki K, Suzuki S, Shimoi K, Horiuchi T, Sakurazawa T, Ariake K, Ishii K, Kumagai J, et al: Disappearance of hyperplastic polyps in the stomach after eradication of Helicobacter pylori. A randomized, clinical trial. Ann Intern Med. 1998, 129: 712-715.

de la Cruz RA, Albillos JC, Oliver JM, Dhimes P, Hernandez T, Trapero MA: Prolapsed hyperplastic gastric polyp causing pancreatitis: case report. Abdom Imaging. 2001, 26: 584-586. 10.1007/s00261-001-0014-y.

Cristallini EG, Ascani S, Bolis GB: Association between histologic type of polyp and carcinoma in the stomach. Gastrointest Endosc. 1992, 38: 481-484.

Varis O, Laxen F, Valle J: Helicobacter pylori infection and fasting serum gastrin levels in a series of endoscopically diagnosed gastric polyps. APMIS. 1994, 102: 759-764.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-230X/3/16/prepub

Acknowledgements

Written consent was obtained from the patient for publication of study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Gencosmanoglu, R., Sen-Oran, E., Kurtkaya-Yapicier, O. et al. Antral hyperplastic polyp causing intermittent gastric outlet obstruction: Case report. BMC Gastroenterol 3, 16 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-230X-3-16

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-230X-3-16