Abstract

Background

Problem gambling often goes undetected by family physicians but may be associated with stress-related medical problems as well as mental disorders and substance abuse. Family physicians are often first in line to identify these problems and to provide a proper referral. The aim of this study was to compare a group of primary care patients who identified concerns with their gambling behavior with the total population of screened patients in relation to co-morbidity of other lifestyle risk factors or mental health issues.

Methods

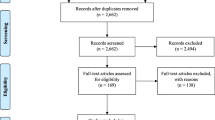

This is a cross sectional study comparing patients identified as worrying about their gambling behavior with the total screened patient population for co morbidity. The setting was 51 urban and rural New Zealand practices. Participants were consecutive adult patients per practice (N = 2,536) who completed a brief multi-item tool screening primary care patients for lifestyle risk factors and mental health problems (smoking, alcohol and drug misuse, problem gambling, depression, anxiety, abuse, anger). Data analysis used descriptive statistics and non-parametric binomial tests with adjusting for clustering by practitioner using STATA survey analysis.

Results

Approximately 3/100 (3%) answered yes to the gambling question. Those worried about gambling more likely to be male OR 1.85 (95% CI 1.1 to 3.1). Increasing age reduced likelihood of gambling concerns – logistic regression for complex survey data OR = 0.99 (CI 95% 0.97 to 0.99) p = 0.04 for each year older. Patients concerned about gambling were significantly more likely (all p < 0.0001) to have concerns about their smoking, use of recreational drugs, and alcohol. Similarly there were more likely to indicate problems with depression, anxiety and anger control. No significant relationship with gambling worries was found for abuse, physical inactivity or weight concerns. Patients expressing concerns about gambling were significantly more likely to want help with smoking, other drug use, depression and anxiety.

Conclusion

Our questionnaire identifies patients who express a need for help with gambling and other lifestyle and mental health issues. Screening for gambling in primary care has the potential to identify individuals with multiple co-occurring disorders.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

As available opportunities for gambling increase, it appears that problem gambling is increasing in prevalence [1]. Gambling disorders have been shown to have high comorbidity with the use of tobacco [1], problem drinking [2, 3], other substance misuse [4], and mood disorder [5]. As well as impacting on an individual's health and well-being, problematic gambling may have serious harmful effects on the patient's family, financial security and career. Family physicians are often the first in the line to identify these problems and to provide a proper referral but problem gambling may go undetected during a standard consultation.

It is well known in the literature that comorbidity is linked with problem gambling and this link is bidirectional [6]. This connection between problem gambling and comorbidity has been widely supported worldwide mainly from treatment populations of problem gamblers, substance abusers, or psychiatric cohorts [7]. Within the general population, a link is reported between problem gambling and 'hazardous use of alcohol' as well as weaker associations between problem gambling and minor mental disorders and with substance abuse and psychiatric illness amongst young people [8]. Overall studies support the supposition that there is a link albeit a weaker one in the general population compared to treatment settings.

Comorbid conditions and problem gambling should not be viewed as discrete disorders, particularly when these individuals engage in treatment. Some problem gamblers will binge on alcohol if they do not have the resources to gamble [9]. Those with dual disorders may engage in other addictive behaviors such as alcohol or drug abuse when recovering from gambling, or relapse with gambling if they are also abusing substances [10].

Individuals with gambling and related comorbidity, tend to move in and out of these disorders. Many do not completely recover from these problem behaviors. For example, women casino employees were able to decrease the problem drinking symptoms over a three year time space frame, but they continued to gamble problematically [11]. Furthermore, many problem gamblers suffer from medical problems such as insomnia, irritable bowel syndrome, peptic ulcer, hypertension, migraines, and other stress-related problems which may be presented to the medical physicians rather than a gambling problem [12].

The aim of this study was to compare the group of New Zealand (NZ) screened primary health care patients who identified concerns with their gambling behavior with the total population of screened patients in relation to co-morbidity of other lifestyle risk factors and mental health issues.

Methods

The assessment of the multi-item screening tool has been reported previously [13]. This is an instrument that contains screening questions for 10 potential issues: smoking, alcohol, substance abuse, gambling, depression, anxiety, stress, violence, eating disorders, physical activity. It also has the addition of a help question asking if the individual wants help no, yes, yes but not today. The gambling question 'Sometimes I've felt depressed or anxious after a session of gambling' has been found to have a sensitivity of 0.857 and a specificity of 0.935 to a positive score in the EIGHT test for problematic gambling [14], which in turn has been validated against the South Oaks Gambling Screen (SOGS) [15]. Validity of the multi-item screening tool against a composite gold standard is currently underway.

The tool was assessed by 51 primary health care providers (family physicians or practice nurses) in one urban, one mixed urban and rural and one rural center in New Zealand. Practitioners were randomly selected using a computer-generated random number table. Multi-center ethical approval was obtained from the Auckland, Otago and Hawkes Bay ethics committees. Participant Information Sheets were provided both for practitioners and for patients, and written consent forms were signed from all participants.

Fifty consecutive adult patients were recruited per practitioner. All consecutive patients aged 16 years and over attending the practice (including those attending as caregiver of another patient) were invited to complete the lifestyle assessment screening tool and evaluation sheet. Exclusion criteria were patients who were unable to understand English or mental impairment that precluded meaningful participation. Demographic data included gender, age and ethnicity.

Data analysis, using descriptive statistics and non-parametric binomial (chi-squared tests and Fishers Exact 2-tailed) was conducted using SPSS-10.0 statistical package. Data included demographic information; positive responses to each screening question and number of patients requesting assistance from their doctor or nurse concerning risk factors.

The 79 who screened positive for concerns about gambling (answered yes to 'Do you sometimes feel unhappy or worried after a session of gambling?') were compared with the total patient population (2536) with respect to their responses to other screening factors. To examine the effects of age, gender, other behaviors on gambling status, a Pearson chi-squared statistic was corrected for the survey design using the second-order correction of Rao and Scott [16] and converted into an F-statistic. Adjusting for clustering by practitioner used STATA survey analysis, χ2 and logistic regression (51 clusters). All analyses were done with the group of 79 as cases.

Results

A total of 2,536 consecutive patients (1000 in Auckland; 1000 in Otago and 536 in Hawkes Bay), 20 urban doctors, 20 practice nurses and 11 rural doctors (51 practices) participated in the study. In Auckland, where patients were recruited by a research assistant, 23 patients actively declined to participate (97.75% response rate). In the other centers refusal rate was not formally recorded but research assistants said that it was less than 5%.

Forty-three of the 79 patients expressing concerns about gambling were female (54%), whereas two-thirds of total sample were female. Those worried about gambling more likely to be male with an odds ratio (OR) of 1.85 (95% CI 1.1–3.1).

The age of the 79 patients ranged from 18 to 89 years with a mean of 43 and SD of 16.3. When age was examined using logistic regression for complex survey data the OR = 0.99 (CI 95% 0.97–0.99) p = 0.035 for each year older – in other words, the older the patient, the less likely to identify as worried about gambling.

Maori (6%, 15/242) were significantly more likely than NZ European (1.55, 15/1002) to be worried about their gambling behavior (p = 0.0002) and were also more likely to want immediate help (p = 0.04) [17].

The group concerned about their gambling were also significantly more likely (all p < 0.0001) to have concerns about their smoking, use of recreational drugs, and alcohol (see Table 1). Similarly they were more likely to indicate a problem with depression, anxiety and anger control. They had no significant relationship for abuse, physical inactivity or weight concerns.

The multivariable logistic regression with 'worry gambling' as the dependent variable is presented in Table 2. Because the responses to the two depression questions are highly correlated (0.47), only the first depression question was used in the model. The increased odds ratios for other factors for those concerned by their gambling show a risk picture of multiple and independent issues.

Eleven out of the 79 (14%) who identified as having gambling concerns expressed a desire for help, five immediately and six at a later date. Those worried about their gambling were significantly more likely to want help with their smoking, other drug use, depression and anxiety (Table 3) but the small numbers means these results should be treated with caution.

Only a proportion of patients acknowledging a problem identified that they would like help with this, either immediately or at a later date. Of those identifying smoking, 44% wanted help, 16% immediately; for alcohol use, 13% with 4.6% immediately; other drug use 28% with 14% immediately, and for gambling, 16% identified that they would like help with this behavior, 6% immediately.

Discussion

It is not surprising that co-occurring symptoms such as depression, anxiety, and substance use linked with worries about gambling. Data do suggest that problem gambling can be associated with non-gambling health problems [18, 19]. Co-occurring conditions were frequently identified amongst a group of patients concerned with their gambling behavior, particularly young males [20]. It is estimated that youth and adult problem gamblers in community and clinical settings drink alcohol and consume other legal and illegal substances at several times the average population rates [21, 22]. A United States national problem gambling survey found 10% of lifetime pathological gamblers alcohol-dependent compared to 1.1% of non-gamblers [23]. A significant number of patients concerned about their gambling were more likely to be apprehensive about their smoking, use of recreational drugs and alcohol. Problem gamblers' rates of smoking have been shown to increase when they gamble [24].

Co-occurring rates of pathological gambling and mental disorders have been examined. Pathological gamblers have been shown to be significantly more likely than non-gamblers to suffer from anxiety disorder [25], and phobias [26] In the present study, patients responding yes to the gambling screen commonly also responded positively to the questions about depression, anxiety and anger control. While the depression questions have already been validated [27], validation of those on anxiety and anger control is currently underway.

It has been reported that moderate to high percentages of adults seeking treatment for pathological gambling have comorbid alcohol and/or substance misuse disorders. [28–30]. In addition, elevated rates of problem and pathological gambling (usually 10% to 20%) are evident among adults seeking professional help for alcohol and other substance misuse/dependence disorders [29, 31–33]. Patients in this study who expressed concerns about their gambling, were also significantly more likely to want help with their smoking, other drug use, depression and anxiety. It has been shown that addition of the help question increases the specificity of the two depression questions used in this study from 67% to 89% while maintaining a sensitivity of 96% [34].

Research suggests that due to issues such as shame and stigma, gamblers are most likely to first seek assistance for gambling-related problems from informal sources of help (their family and friends) and to develop a range of self-help strategies prior to seeking formal (professional) assistance [35]. It is possible that the distribution of when patients would like help with their gambling could be partially explained by the above preferences of help-seeking.

Major reasons suggested for not seeking treatment are the desire to handle the problem without help, negative attitude related to stigmatization of addiction problems and embarrassment and pride [36]. For services to be accessible, they must be sensitive to the target demographics. For example, despite inflated problem gambling rates, some ethnicities [35, 37] and age groups (adolescents) [38], often do not access mainstream gambling help agencies.

It should be noted that other reasons for a low rate of desire for help with gambling might reflect not having a gambling problem, not identifying a gambling problem that is present, or having a past gambling problem that has been resolved. The latter is less likely however, given that the gambling question is framed in the present tense.

A strength of this study is that it is the first to report co-morbidity in both lifestyle behaviors and mental health issues in a general practice setting. A weakness of this study is that we cannot be specific about the response rates in some of the centers but believe it to be low and unlikely to over-estimate any morbidities. Each question is quite brief however we know from other work that asking for help for depression is associated with a positive predictive value of 48% for major depression [39]. A further limitation is that a single question was used to assess gambling behavior with no specific timeframe referenced. While individual brief questions may have been validated, the composite tool has not yet been fully validated against a complied gold standard, although this work in underway. Furthermore because the question asks about feeling worried or unhappy after gambling, the likelihood of co-occurrence with a generalized anxiety or depressive disorder is increased and a positive response to the question does not necessarily indicate a gambling disorder.

Conclusion

While screening is recommended by some authorities for depression, alcohol problems and obesity, some thought needs to be give to considering screening for problem gambling in primary care [40]. There is a need for more research, particularly of a detailed nature with more structured assessments used in conjunction with screening items, to improve prevention and treatment strategies.

Abbreviations

- CI:

-

confidence interval

- MIST:

-

multi-item screening tool

- NZ:

-

New Zealand

- OR:

-

odds ratio

References

Pasternak AV, Fleming MF: Prevalence of gambling disorders in a primary care setting. Arch Fam Med. 1999, 8: 515-520. 10.1001/archfami.8.6.515.

Stewart SH, Kushner MG: Recent research on the comorbidity of alcoholism and pathological gambling. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2003, 27: 285-291.

Welte JW, Barnes GM, Wieczorek WF, Tidwell MC: Simultaneous drinking and gambling: a risk factor for pathological gambling. Subst Use Misuse. 2004, 39: 1405-1422. 10.1081/JA-120039397.

Kausch O: Patterns of substance abuse among treatment-seeking pathological gamblers. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2003, 25: 263-270. 10.1016/S0740-5472(03)00117-X.

Henderson MJ: Psychological correlates of comorbid gambling in psychiatric outpatients: a pilot study. Subst Use Misuse. 2004, 39: 1341-1352. 10.1081/JA-120039391.

Gambino B, Fitzgerald R, Shaffer HJ, Renner J, et al: Perceived family history of problem gambling and scores on SOGS. Journal of Gambling Studies. 1993, 9: 169-184. 10.1007/BF01014866.

Shepherd RM: Clinical obstacles in administrating the South Oaks Gambling Screen in a methadone and alcohol clinic. Journal of Gambling Studies. 1996, 12: 21-32. 10.1007/BF01533187.

Lynch WJ, Maciejewski PK, Potenza MN: Psychiatric correlates of gambling in adolescents and young adults grouped by age at gambling onset. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004, 61: 1116-1122. 10.1001/archpsyc.61.11.1116.

Sullivan S, Penfold A: Coexisting problem gambling and alcohol misuse: the case for reciprocal screening. Problem Gambling and Mental Health in New Zealand Selected Proceedings from the national conference on gambling (1999). Edited by: Adams P and Bayley B. 2000, Auckland, Compulsive Gambling Society of NZ Inc, 133-138.

Shaffer HJ, LaPlante DA, LaBrie RA, Kidman RC, Donato AN, Stanton MV: Toward a Syndrome Model of Addiction: Multiple Expressions, Common Etiology. Harvard Review of Psychiatry. 2004, 12: 367-374. 10.1080/10673220490905705.

Shaffer HJ, Hall MN: The natural history of gambling and drinking problems among casino employees. Journal of Social Psychology. 2002, 142: 405-424.

Westphal JR, Johnson LJ, Stodghill S, Stevens L: Gambling in the south: implications for physicians. South Med J. 2000, 93: 850-858.

Goodyear-Smith F, Arroll B, Sullivan S, Elley C, Docherty B, Janes R: Lifestyle screening: development of an effective and acceptable general practice tool. New Zealand Medical Journal. 2004, 117: 1-10.

Sullivan S: 'The 'eight' Gambling Screen. General Practice & Primary Health Care. 1999, Auckland, University of Auckland

Battersby MW, Thomas LJ, Tolchard B, Esterman A: The South Oaks Gambling Screen: A review with reference to Australian use. Journal of Gambling Studies. 2002, 18: 257-271. 10.1023/A:1016895221871.

Rao JNK, Scott AJ: On Chi-squared Tests For Multiway Contigency Tables with Proportions Estimated From Survey Data. Annals of Statistics. 1984, 12: 46-60.

Goodyear-Smith F, Arroll B, Coupe N, Buetow S: Ethnic differences in mental health and lifestyle issues: results from multi-item general practice screening. N Z Med J 118(1212):U1374. 2005, 118: U1374-

Potenza MN, Fiellin DA, Heninger GR, Rounsaville BJ, Mazure CM: Gambling: an addictive behavior with health and primary care implications. J Gen Intern Med. 2002, 17: 721-732. 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.10812.x.

Petry N, Stinson F, Grant G: Comorbidity of DSM-IV Pathological Gambling and Other Psychiatric Disorders: Results From the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005, 66: 564-574.

Winters KC, Kushner MG: Treatment issues pertaining to pathological gamblers with a comorbid disorder. J Gambl Stud. 2003, 19: 261-277. 10.1023/A:1024203403982.

Volberg RA, Abbott MW: Lifetime prevalence estimates of pathological gambling in New Zealand. International Journal of Epidemiology. 1994, 23: 976-983.

Fisher S: Gambling and Pathological Gambling in Adolescents. Journal of Gambling Studies. 1993, 9:

Gerstein D, Volberg R, Toce M, Harwood H, Palmer A, Johnson R, Larison C, Chuchro L, Buie T, Engelman L, Hill M: Gambling Impact and Behaviour Study: Report to the National Gambling Impact Study Commission. 1999, Chicago, IL, National Opinion Research Center at the University of Chicago

Sullivan SG, Beer H: Smoking and problem gambling in NZ: problem gamblers' rates of smoking increase when they gamble. Health Promotion J of Australia. 2003, 14: 192-195.

Bland RC, Newman SC, Orn H, Stebelsky G: Epidemiology of Pathological Gambling in Edmonton. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 1993, 38:

Cunningham-Williams RM, Cottler LB, Compton WM, Spitznagel EL: Taking Chance: Problem Gamblers and Mental Disorders - Results from the St. Louis Epidemiological Catchment Area (ECA) Study. American Journal of Public Health. 1998, 88: 1093-1096.

Arroll B, Khin N, Kerse N: Depression screening in primary care: Two verbally asked questions are simple and valid. British Medical Journal. 2003, 327: 1144 -11146.

Crockford DN, el-Guebaly N: Psychiatric comorbidity in pathological gambling: a critical review. Can J Psychiatry. 1998, 43: 43-50.

Lesieur HR, Blume SB, Zoppa RM: Alcoholism, Drug Abuse and Gambling. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1986, 10: 33-38.

Petry N: A Comparison of Young, Middle-Aged, and Older Adult Treatment-Seeking Pathological Gamblers. Gerentologist. 2002, 42: 92-99.

Abbott M, Volberg R, Bellringer M, Reith G: A Review of Research on Aspects of Problem Gambling. 2004, London, Responsibiity in Gambling Trust

Feigelman W, Wallisch LS, Lesieur HR: Problem Gamblers, Problem Substance Users, and Dual Problem Individuals: An epidemiological Study. American Journal of Public Health. 1998, 88: 467-470.

Petry N: How Treatments for Pathological Gambling Can Be Informed by Treatments for Substance Use Disorders. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2002, 10: 184-192. 10.1037/1064-1297.10.3.184.

Arroll B, Goodyear-Smith F, Kerse N, Fishman T, Gunn J: Effect of the addition of a "help" question to two screening questions on specificity for diagnosis of depression in general practice: diagnostic validity study. BMJ. 2005, doi:10.1136/bmj.38607.464537.7C:

McMillen J, Marshall D, Murphy L, Lorenzen S, Waugh B: Help-seeking by problem gamblers, friends and families: A focus on gender and cultural groups. 2004, Canberra, Centre for Gambling Research, RegNet, Australian National University

Hodgins DC, el-Guebaly N: Natural and treatment-assisted recovery from gambling problems: a comparison of resolved and active gamblers. Addiction. 2000, 95: 777-789. 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2000.95577713.x.

Brown K: Understanding problem gambling in ethnocultural communities: Taking the first steps. Newslink: Responsible Gambling Issues and Information. 2002, Fall 2002: 1-5.

Chevalier S, Griffiths M: Why don't adolescents turn up for gambling treatment (revisited)?. [http://www.camh.net/egambling/issue11/jgi_11_chevalier_griffiths.html]11

U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF): Mental Health Conditions and Substance Abuse. [http://www.ahrq.gov/clinic/uspstfix.htm]

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2296/7/25/prepub

Acknowledgements

The study involved initial collaboration between primary health care researchers with specific lifestyle or mental health interests and expertise in the Department of General Practice and Primary Health Care, the University of Auckland in the development of the tool.

Funding for this study was provided by the Charitable Trust of the Auckland Faculty of the Royal New Zealand College of General Practitioners; the Ministry of Health Mental Health Directorate and the Institute of Rural Health, Hamilton.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests statement

The authors declare that they have no competing interests. The complete independence of researchers from funders is declared.

Authors' contributions

FG conceived of the study, participated in its design, co-ordination and analysis and drafted the manuscript.

BA participated in the design and analysis of the study and helped draft the manuscript.

NK participated in the design and analysis of the study and contributed to manuscript revision.

SS participated in the design of the gambling component of the study and contributed to manuscript revision.

NC participated in the design and analysis of the study and contributed to manuscript revision.

ST participated in analysis of the study and contributed to manuscript revision.

RS participated in analysis of the study and contributed to manuscript revision.

ST participated in analysis of the study and contributed to manuscript revision.

FR participated in analysis of the study and contributed to manuscript revision.

LP participated in analysis of the study and contributed to manuscript revision.

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Goodyear-Smith, F., Arroll, B., Kerse, N. et al. Primary care patients reporting concerns about their gambling frequently have other co-occurring lifestyle and mental health issues. BMC Fam Pract 7, 25 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2296-7-25

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2296-7-25