Abstract

Background

Despite the favorable effects of behavior change interventions on diabetes risk, lifestyle modification is a complicated process. In this study we therefore investigated opportunities for refining a lifestyle intervention for type 2 diabetes prevention, based on participant perceptions of behavior change progress.

Methods

A 30 month intervention was performed in Dutch primary care among high-risk individuals (FINDRISC-score ≥ 13) and was compared to usual care. Participant perceptions of behavior change progress for losing weight, dietary modification, and increasing physical activity were assessed after18 months with questionnaires. Based on the response, participants were categorized as ‘planners’, ‘initiators’ or ‘achievers’ and frequencies were evaluated in both study groups. Furthermore, participants reported on barriers for lifestyle change.

Results

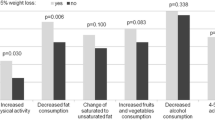

In both groups, around 80% of all participants (intervention: N = 370; usual care: N = 322) planned change. Except for reducing fat intake (p = 0.08), the number of initiators was significantly higher in the intervention group than in usual care. The percentage of achievers was high for the dietary and exercise objectives (intervention: 81–95%; usual care: 83–93%), but was lower for losing weight (intervention: 67%; usual care: 62%). Important motivational barriers were ‘I already meet the standards’ and ‘I’m satisfied with my current behavior’. Temptation to snack, product taste and lack of time were important volitional barriers.

Conclusions

The results suggest that the intervention supports participants to bridge the gap between motivation and action. Several opportunities for intervention refinement are however revealed, including more stringent criteria for participant inclusion, tools for (self)-monitoring of health, emphasis on the ‘small-step-approach’, and more attention for stimulus control.

Trial registration

Netherlands Trial Register: NTR1082

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Type 2 diabetes mellitus is a serious illness, leading to severe complications [1] and increased mortality [2]. Global incidence of the disease is estimated to rise to 552 million individuals in 2030, posing a great burden to many countries worldwide [3]. Behavior change interventions can however prevent or delay development of type 2 diabetes in individuals at high risk [4]. In the Diabetes Prevention Study (DPS) and the Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP) for example, dietary improvement and more physical activity led to a reduction in diabetes incidence of nearly 60% in 4 years [5, 6].

Despite the favorable effects of behavior change interventions on type 2 diabetes risk, lifestyle modification is a complicated process [7, 8]. Furthermore, due to organizational and financial barriers, translation of successful lifestyle interventions into daily life settings is challenging [9, 10]. More insight into the process of behavior change may reveal opportunities for refining intervention content and may thereby potentially improve intervention effectiveness [9–11]. Nevertheless, evaluation of behavior change in diabetes prevention programs remains limited [10].

The ‘Active Prevention in High Risk individuals Of Diabetes Type 2 in and around Eindhoven’ (APHRODITE) study investigates the effectiveness and feasibility of lifestyle counseling for diabetes prevention in Dutch primary care. In this article we investigate the perceived behavior change phase for several lifestyle objectives of participants receiving lifestyle counseling and receiving usual care. In addition, we assess the main perceived barriers for planning or achieving behavior change. Based on these insights we discuss opportunities for refining intervention content.

Methods

Participants were recruited in January 2008 by 48 general practitioners (GPs) and 24 nurse practitioners from 14 primary care practices in the Netherlands. A Dutch translation of the Finnish FINDRISC [12] was sent to GP patients aged ≥40 and ≤70 years. All individuals with a score ≥13 points (n = 1533) were invited to participate [13]. To minimize selection bias, individuals were at random allocated to either the intervention group (n = 479) or the usual care group (n = 446). Randomization was performed on the level of the individual [13]. Details of participant recruitment, randomization and intervention reach were described previously [13]. Individuals who were diagnosed with diabetes during the follow-up were excluded from the study and were referred to the GP for further care.

Intervention group

The APHRODITE intervention was based on the transtheoretical model [7] and was designed to support participant progress from a motivational phase (planning change), via the motivation-action gap (initiating change) towards an action phase (achieving change) (Figure 1). Progress through the phases is limited by motivational and volitional barriers, which can be influenced by lifestyle counseling. In our study, a combination of behavior change techniques was used (motivational interviewing, filling out decisional balance sheets, goal setting, developing action plans, barrier identification, relapse prevention) [8, 14]. Details of the theoretical framework of the APHRODITE intervention are described in Additional file 1.

Intervention effects on participant behavior change. During the process of behavior change, individuals progress from a motivational phase (planning change), via the motivation-action gap (initiating change) towards an action phase (achieving change). Progress through the different phases is limited by motivational and volitional barriers, which can be affected using lifestyle counseling.

After the admission interview with the GP [13], 11 consultations of 20 minutes were scheduled over 30 months with alternately the nurse practitioner and the GP (Additional file 2). In addition, 5 group meetings were organised by dieticians and physiotherapists to provide more detailed information on diet and exercise. Moreover, intervention-group participants were invited for a 1-hour consultation with a dietician, in which a 3-day food record was discussed.

Five project objectives were specified: weight reduction of at least 5% if overweight, physical exercise of moderate to high intensity for at least 30 minutes a day for at least five days a week, dietary fat intake less than 30% and saturated fat intake less than 10% of total energy intake and dietary fibre intake of at least 3.4 g per MJ. Following a tailor-made and small-step approach [15], participants were however stimulated by the nurse practitioner to set individual (intermediate) goals and develop individual action plans.

The programme was free of charge for all participants. Providers received financial reimbursement for all consultations with their participants according to Dutch payment standards. The intervention was registered with the Dutch Trial Register (NTR1082). The Medical Ethical Review Committee of the Catharina Hospital in Eindhoven gave ethical approval to the study (M07-1705). All participants gave informed consent for participation.

GP and nurse practitioner training

Before the start of the study, all GPs and nurse practitioners received a two-evening directive instruction on the theoretical framework of the intervention and its translation into practice (the content of this instruction is summarized in Additional file 1 and the mode of delivery in Additional file 3). In addition, a manual with all topics discussed and key-message cards for use during consultations were sent both on paper and by email. Moreover, as they intensively guided the behavior change process, all nurse practitioners received a five-evening course in motivational interviewing (MI) [16] (briefly summarized in Additional file 3). As a part of the course, active role-playing was performed and consultations with participants were audio-taped for feedback purposes. During the study, regular return-meetings were organised with GPs (once a year) and nurse practitioners (every half a year).

Usual care group

During the admission interview, participants in the usual care group received oral and written information about type 2 diabetes and a healthy lifestyle. The nurse practitioner was visited only for measurements at baseline and after 6, 18 and 30 months. Apart from the admission interview participants did not have study-related encounters with the GP.

Participant questionnaires

Questionnaires were filled out after 18 months of intervention (Additional file 4). Response was 92% in the intervention group and 85% in the usual care group. To reduce detection bias, individuals were not made aware of being in the intervention or the usual care group; they were only told to be in either of two groups with different contact frequency.

To gain more insight into perceived behavior change progress (Figure 1), participants were first asked whether they were planning to change a behavior or were already acting on it. When answering yes, they were asked whether they had initiated change. When answering yes, they were asked whether they had achieved change. For analysis, all participants who indicated to have planned, but not initiated change were called planners. All who reported to have initiated, but not achieved change were called initiators. Participants who indicated to have achieved change were called achievers.

Motivational and volitional barriers for behavior change were inquired for all lifestyle objectives using open questions. Motivational barriers were collected from non-planners with reporting rates ranging from 87% to 99% (intervention) and from 83% to 99% (usual care). Volitional barriers were collected from initiators and achievers, with reporting rates ranging from 81% to 88% (intervention) and from 80% to 94% (usual care). All barriers were coded by the main investigator and two research assistants; inconsistencies were checked by the main investigator. Categorization of the barriers was based on frameworks developed by Penn et al. [11] and Grol and Wensing [17].

Sample size calculation

Sample size calculation was based on the main outcome diabetes incidence. As implementation of lifestyle interventions in real life settings is challenging [9, 10], modest differences between groups were expected. To detect small differences in diabetes incidence (Cohen’s conventional effect size of 0.1), with a power of 0.8, 393 individuals were needed in each arm. As in total 925 individuals could be included, this allowed for a dropout rate of approximately 15%, which was in line with others [4]. Post-hoc power analysis showed that the power to detect small differences between groups in the percentage of planners was 0,75 for all lifestyle objectives. For a difference in initiators, the power ranged between 0,63-0,68 and for a difference in achievers between 0,46-0,59.

Statistical analysis

Differences between study groups were analysed with chi-square tests using SPSS 18.0. A p-value of <0.05 was considered significant. Additionally, the effect of a bonferroni adjustment for multiple comparisons was investigated (p = 0.05/15 = <0.003). Individuals who developed diabetes during follow-up intervention: N = 32 (6.8%); usual care: N = 32 (7.3%) or who ended participation intervention: N = 46, 9.6%; usual care: N = 36 (8.1%) were excluded from the study and from analysis.

Results

No significant differences in baseline characteristics (sex, age, education, FINDRISC-score, smoking) and clincial measures (mean bmi, mean fasting and 2-hour glucose values) were observed between study groups. Table 1 shows perceived behavior change at 18 months of participants in both groups for all lifestyle objectives. The percentage of planners ranged from 76% to 85% in both groups and was comparable between groups. The percentage of initiators ranged from 72% to 86% (intervention) and from 59% to 79% (usual care). Except for reducing fat intake (p = 0.08), the percentage of initiators was significantly higher in the intervention group than in the usual care group. When a bonferroni adjustment was applied significance was lost for all objectives. For the nutrition and physical activity objectives, the percentage of achievers ranged from 81% to 95% (intervention) and from 83% to 93% (usual care). For losing weight these percentages were 67% (intervention) and 62% (usual care). For all lifestyle objectives, the percentage of achievers did not significantly differ between groups.

Table 2 summarizes the most-mentioned behavior change barriers of participants in both groups. Both the motivational and volitional barriers were highly comparable between the study groups. For all objectives an important barrier for planning change was ‘I already meet the standards’. This especially applied to the dietary fibre, total fat and physical activity objectives, with reporting-rates ranging from 56 to 66% (intervention) and from 48 to 69% (usual care). Another important factor limiting participant motivation was ‘I’m satisfied with my health and/or behavior’, especially regarding weight (intervention: 26%; usual care: 35%).

For the weight loss and physical activity objectives, continuity (maintaining a new habit on the longer term) was an often-reported bottleneck (intervention: 13% and 12%; usual care: 14% for both). For the weight loss and fat-related objectives, temptation to snack was an important volitional barrier, with reporting-rates ranging from 19% to 32% (intervention) and from 18% to 28% (usual care). Lack of time was a bottleneck for increasing physical activity (intervention: 17%; usual care: 23%). A substantial number reported ‘no difficulties’ when trying to achieve dietary objectives (intervention: 33%-52%; usual care: 33% to 67%).

Discussion

Although lifestyle change can lead to reduced diabetes risk, it is a complicated process [7, 8]. In this article we therefore investigated the perceived behavior change phase for several lifestyle objectives of participants receiving lifestyle counseling and receiving usual care. In addition, we assess the main perceived barriers for planning or achieving behavior change. Based on these insights we discuss opportunities for refining intervention content (Table 3).

The motivational phase (planning change)

Participation in a behavior change program implies that individuals are motivated to improve their lifestyle [18]. In line with this hypothesis, the percentage of non-planners was low in both groups for all objectives. Two important barriers for planning change were the conviction that recommendations were already met and satisfaction with the current behavior. The relatively low cut-off-value of the FINDRISC (≥13 points) may have led to the selection of individuals with a relatively healthy lifestyle, limiting the motivation to change [10, 19]. In line with this hypothesis, 40% of the non-planners had a healthy BMI (<25 kg/m2) at 18 months versus 13% of the planners (p = <0.0001). An increase in the FINDRISC-value for inclusion or evaluation of participant lifestyle prior to invitation are therefore recommended.

Another explanation for the large number of non-planners convinced of their health may be an inability of participants to correctly interpret the lifestyle. For the dietary objectives for example, 58% to 87% of the convinced non-planners incorrectly thought they already met the recommendations. Non-planners should therefore be better informed about the standards reflecting a healthy lifestyle. Second, introduction of tools for self-monitoring, like in the PRAEDIAS-study [20, 21] may help participants reflect on their health.

The motivation-action gap (initiating change)

Significant differences in the number of initiators were observed between the groups for nearly all objectives. This result suggests that the intervention was successful in helping participants bridge the gap between motivation and action. Overcoming this gap is regarded as an important step in behavior change [8, 22]. Possibly contributing to taking this step, participants were stimulated to set goals and develop concrete action plans [8, 14, 22]. Despite this apparant success, 15% to 28% of the planners in the intervention group did not put their plans into action. This may partially be explained by a lack of action self-efficacy [23]. Action self-efficacy could potentially be enlarged by underlining the ‘small-step-approach’ of the intervention, in which participants are encouraged to make small, but meaningful changes that can more easily be sustained long-term [15].

The differences in the number of initiators were no longer significant after applying a bonferroni adjustment for multiple comparisons. This loss of significance could however partially be explained by a lack of statistical power to detect small differences in the number of initiators between groups (0,63-0,68). Because behavior change phase was not assessed at baseline we cannot exclude that the difference in the percentage of initiators between groups may partially be due to baseline differences. However, as persons were randomly assigned to either group and no differences in baseline characteristics or clinical measures were observed, this possibility seems unlikely. The absence of baseline differences between groups also makes it unlikely that the results were subject to selection bias. Intervention group participants may however have been aware of the high(er) contact frequency with the GP and the nurse practitioner and may therefore more easily have given socially desirable answers (detection bias).

The action phase (achieving change)

A majority of initiators in the intervention group indicated to have achieved change regarding diet and physical activity. Risk factor reductions shown in the intervention group after 18 months however were modest (BMI: -0.1 kg/m2, p = 0.66; fasting glucose: -0.02 mmol/l, p = 0.77) and no significant difference in diabetes incidence was found between the intervention group (10.0%) and the usual care group (11.9%) (p = 0.99) after 30 months [24, 25]. This discrepancy may be explained by the inability of participants to correctly monitor lifestyle change. Introduction of tools for self-monitoring may therefore also be recommended for participants to reflect on their progress. In other studies, self-monitoring was also found to contribute to lifestyle change [14, 20, 26]. Too optimistic perceptions of initiators may also have been caused by setting goals that were not challenging enough. It is therefore important that providers guard progress towards achieving the project objectives.

Despite the positive view of initiators, several barriers for achieving lifestyle change were reported. For the weight loss and physical activity objectives, continuity (maintaining a new habit on the longer term) was an often-reported bottleneck. This result may reflect the tendency to make too drastic alterations in the lifestyle (extreme dieting, intensive work-outs), that can easily result in relapse [15]. Following the small-step approach of our intervention [15], participants should therefore be stimulated to set intermediate goals. In addition, a goal and performance logbook may facilitate continued evaluation of participant progress [21].

For the weight loss and dietary objectives, resisting temptation to snack was an often-mentioned difficulty. This result underlines the importance of techniques to control internal and external stimuli, as described by for example Shaw et al. [27]. Professionals may support stimulus control by encouraging participants to avoid cues (for example not have snacks stored at home) [27] and to engage social support [14, 26]. In addition, monitoring of psychological causes for and circumstances of habitual behavior [21] may help participants to identify future high-risk situations, so that strategies can be developed beforehand.

Strengths and limitations

Our study provides more insight into the black box between the intervention on the one side and its effectiveness of the other side. The high response rates make it unlikely that missing values have markedly influenced the results. When answering questions, participants may however have been affected by recent experiences. The missing data of drop-outs and individuals diagnosed with diabetes may have influenced participant outcomes. In addition, as barriers to change were only inquired once, development over time could not be investigated. An opposite approach of inquiring facilitators for change could provide valuable additional insights into behavior change. Furthermore, it would have been useful to provide participants with the opportunity to express their views and preferences during intervention development.

Conclusions

A better insight into the process of behavior change can contribute to better adapted and potentially more effective interventions for diabetes prevention [9–11]. Although the results suggest that the APHRODITE intervention helps participants bridge the gap between motivation and action, several opportunities for refining intervention content are revealed. Recommendations for practice include an increase in the FINDRISC value for participant inclusion, instruction about standards reflecting a healthy lifestyle, tools for (self)-monitoring of health and lifestyle, goal setting and action planning, engaging social support, monitoring of causes for and circumstances of habitual behavior, a larger emphasis on the small-step-approach, and more attention for controlling environmental and psychological stimuli.

References

Nathan DM: Long-term complications of diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 1993, 328 (23): 1676-1685. 10.1056/NEJM199306103282306.

Roglic G, Unwin N: Mortality attributable to diabetes: estimates for the year 2010. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2010, 87 (1): 15-19. 10.1016/j.diabres.2009.10.006.

International Diabetes Federation, I.D.F: Diabetes atlas 2010. 2010, Brussels, Belgium: International Diabetes Federation, cited 4th edition: http://www.idf.org/media-events/press-releases/2011/diabetes-atlas-5th-edition

Gillies CL: Pharmacological and lifestyle interventions to prevent or delay type 2 diabetes in people with impaired glucose tolerance: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2007, 334 (7588): 299-10.1136/bmj.39063.689375.55.

Knowler WC: Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med. 2002, 346 (6): 393-403.

Tuomilehto J: Prevention of type 2 diabetes mellitus by changes in lifestyle among subjects with impaired glucose tolerance. N Engl J Med. 2001, 344 (18): 1343-1350. 10.1056/NEJM200105033441801.

Baranowski T: Are current health behavioral change models helpful in guiding prevention of weight gain efforts?. Obes Res. 2003, 11 (Suppl): 23S-43S.

Brug J, Oenema A, Ferreira I: Theory, evidence and Intervention Mapping to improve behavior nutrition and physical activity interventions. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2005, 2 (1): 2-10.1186/1479-5868-2-2.

Rosal MC: Opportunities and challenges for diabetes prevention at two community health centers. Diabetes Care. 2008, 31 (2): 247-254.

Simmons RK, Unwin N, Griffin SJ: International Diabetes Federation: An update of the evidence concerning the prevention of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2010, 87 (2): 143-149. 10.1016/j.diabres.2009.10.003.

Penn L, Moffatt SM, White M: Participants' perspective on maintaining behaviour change: a qualitative study within the European Diabetes Prevention Study. BMC Publ Health. 2008, 8: 235-10.1186/1471-2458-8-235.

Lindstrom J, Tuomilehto J: The diabetes risk score: a practical tool to predict type 2 diabetes risk. Diabetes Care. 2003, 26 (3): 725-731. 10.2337/diacare.26.3.725.

Vermunt PW: An active strategy to identify individuals eligible for type 2 diabetes prevention by lifestyle intervention in Dutch primary care: the APHRODITE study. Fam Pract. 2010, 27 (3): 312-319. 10.1093/fampra/cmp100.

Paulweber B: A European evidence-based guideline for the prevention of type 2 diabetes. Horm Metab Res. 2010, 42 (Suppl 1): S3-S36.

Hill JO: Can a small-changes approach help address the obesity epidemic? A report of the Joint Task Force of the American Society for Nutrition, Institute of Food Technologists, and International Food Information Council. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009, 89 (2): 477-484. 10.3945/ajcn.2008.26566.

Rubak S: Motivational interviewing: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Gen Pract. 2005, 55 (513): 305-312.

Grol R, Wensing M: What drives change? Barriers to and incentives for achieving evidence-based practice. Med J Aust. 2004, 180 (6 Suppl): S57-S60.

Saaristo T: Lifestyle intervention for prevention of type 2 diabetes in primary health care: one-year follow-up of the Finnish National Diabetes Prevention Program (FIN-D2D). Diabetes Care. 2010, 33 (10): 2146-2151. 10.2337/dc10-0410.

Makrilakis K: Implementation and effectiveness of the first community lifestyle intervention programme to prevent Type 2 diabetes in Greece. The DE-PLAN study. Diabet Med. 2010, 27 (4): 459-465. 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2010.02918.x.

Kulzer B: Prevention of diabetes self-management program (PREDIAS): effects on weight, metabolic risk factors, and behavioral outcomes. Diabetes Care. 2009, 32 (7): 1143-1146. 10.2337/dc08-2141.

Hermanns N, Gorges D, Project Management, I.M.A.G.E: IMAGE (Development and Implementation of a European Guideline and Training Standards for Diabetes Prevention. 2009, Bad Mergentheim, Germany: Research Institute of Diabetes Academy, http://www.image-project.eu/pdf/PRAEDIAS.pdf,

Prestwich A, Lawton R, Conner M: The use of implementation intentions and the decision balance sheet in promoting exercise behaviour. Psychol Health. 2003, 18 (6): 707-721. 10.1080/08870440310001594493.

Schwarzer R, Renner B: Social-cognitive predictors of health behavior: action self-efficacy and coping self-efficacy. Health Psychol. 2000, 19 (5): 487-495.

Vermunt PW: A lifestyle intervention to reduce Type 2 diabetes risk in Dutch primary care: 2.5-year results of a randomized controlled trial. Diabet Med. 2012, 29 (8): e223-e231. 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2012.03648.x.

Vermunt PW: Lifestyle counseling for type 2 diabetes risk reduction in Dutch primary care: results of the APHRODITE study after 0.5 and 1.5 years. Diabetes Care. 2011, 34 (9): 1919-1925. 10.2337/dc10-2293.

Greaves CJ: Systematic review of reviews of intervention components associated with increased effectiveness in dietary and physical activity interventions. BMC Publ Health. 2011, 11: 119-10.1186/1471-2458-11-119.

Shaw K: Psychological interventions for overweight or obesity. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005, CD003818-2

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2296/14/78/prepub

Acknowledgements

We thank Lidwien Lemmens and Jorien Veldwijk from the National Institute for Public Health and the Environment in Bilthoven for reviewing our manuscript. Furthermore, we thank all GPs and nurse practitioners from ‘De Ondernemende Huisarts’ (DOH) and all participants. This study was supported by ZonMw ‘the Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development’ (63,300,016).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

All authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

PV contributed to the study design, to the acquisition of the data, and to analysis and interpretation of the data and drafted the manuscript. IM, FW, CB, JS, GW and HvO contributed to the study design and to the interpretation of the data and critically revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

12875_2012_884_MOESM1_ESM.docx

Additional file 1: Overview of the theoretical framework of the APHRODITE intervention to support behavior change.(DOCX 13 KB)

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Vermunt, P.W., Milder, I.E., Wielaard, F. et al. Behavior change in a lifestyle intervention for type 2 diabetes prevention in Dutch primary care: opportunities for intervention content. BMC Fam Pract 14, 78 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2296-14-78

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2296-14-78