Abstract

Background

Effective diabetes prevention strategies that can be implemented in daily practice, without huge amounts of money and a lot of personnel are needed. The Dutch Diabetes Federation developed a protocol for coaching people with impaired fasting glucose (IFG; according to WHO criteria: 6.1 to 6.9 mmol/l) to a sustainable healthy lifestyle change: ‘the road map towards diabetes prevention’ (abbreviated: Road Map: RM). This protocol is applied within a primary health care setting by a general practitioner and a practice nurse. The feasibility and (cost-) effectiveness of care provided according to the RM protocol will be evaluated.

Methods/Design

A cluster randomised clinical trial is performed, with randomisation at the level of the general practices. Both opportunistic screening and active case finding took place among clients with high risk factors for diabetes. After IFG is diagnosed, motivated people in the intervention practices receive 3–4 consultations by the practice nurse within one year. During these consultations they are coached to increase the level of physical activity and healthy dietary habits. If necessary, participants are referred to a dietician, physiotherapist, lifestyle programs and/or local sports activities. The control group receives care as usual. The primary outcome measure in this study is change in Body Mass Index (BMI). Secondary outcome measures are waist circumference, physical activity, total and saturated fat intake, systolic blood pressure, blood glucose, total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, triglycerides and behaviour determinants like risk perception, perceived knowledge and motivation. Based on a sample size calculation 120 people in each group are needed. Measurements are performed at baseline, and after one (post-intervention) and two years follow up. Anthropometrics and biochemical parameters are assessed in the practices and physical activity, food intake and their determinants by a validated questionnaire. The cost-effectiveness is estimated by using the Chronic Disease Model (CDM). Feasibility will be tested by interviews among health care professionals.

Discussion

The results of the study will provide valuable information for both health care professionals and policy makers. If this study shows the RM to be both effective and cost-effective the protocol can be implemented on a large scale.

Trial registration

ISRCTN41209683. Ethical approval number: NL31342.075.10.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Diabetes is an increasing problem which affects approximately 371 million people worldwide [1]. In 2011 the estimated prevalence in the Netherlands was 834.100 people with diabetes, of which 90% with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), with an annual estimate of newly discovered cases of 71,000 in that year [2]. This number translates into approximately 5% of the total Dutch population and is expected to rise to 1,300,000 and 1,600,000 in 2025 [3]. Many of these people are not aware of their risk of diabetes, but already have impaired fasting glucose (IFG; according to WHO criteria: 6.1 to 6.9 mmol/l). It is estimated, that some 750.000 people in the Netherlands between 30 and 70 years of age have either IFG or impaired glucose tolerance (IGT) [4]. People with IFG not only have a high risk of developing T2DM on short term, but also have an increased cardiovascular risk [5]. Without changes in lifestyle and proper support, about 9% of people with IFG will develop T2DM within three years [6].

When IFG is diagnosed, follow-up often is not well organized. The Diabetes Mellitus type 2 guideline of the Dutch College of General Practitioners 2006 advices a regular check in people known with IFG for development of T2DM and to treat their cardiovascular risk factors [7]. However, these people are not monitored systematically: most of the times a simple life style advice is given, combined with the advice to have fasting blood glucose measured at regular intervals. Health care providers indicate that there is a need for support in coaching people with IFG in a more systematic and intensive way. They also indicate that they do not know how to handle this group [8].

Lifestyle interventions which focus on both physical activity and diet can be effective for people diagnosed with IFG, with a relative risk reduction of 43% seven years after the start of the intervention [9, 10]. Another study shows a similar risk reduction which sustained even 20 years after the start [11, 12] Also Dutch projects show that it is possible to stimulate people to change their lifestyle [13–15]. For example, the SLIM study shows an improvement of glucose tolerance, which sustained after three years [16]. While the studies mentioned above show that a health gain can be achieved by people at risk for diabetes, another Dutch study on reducing risk by lifestyle change did not show the expected effects and proved to be not cost-effective [17]. Still it is concluded that combined lifestyle interventions are likely to have great potential as a strategy to prevent diabetes. Actually, these most successful interventions were obtained using many personnel and intensive supervision while the current practice requests less expensive, simple interventions which can be easily carried out in daily practice.

For above mentioned reason and in order to meet the needs of both people at high risk to develop T2DM and health care professionals, the Dutch Diabetes Federation (NDF) developed a protocol for coaching persons with an increased risk of diabetes in general practice called ‘the road map towards diabetes prevention’ (abbreviated: Road Map: RM). It aims to delay or even prevent the development of T2DM and associated cardiovascular risk factors. The protocol is developed according to the framework of the Diabetes Mellitus type 2 Guideline of the Dutch College of General Practitioners [7]. To include people in the protocol, people at risk for diabetes were stimulated to fill out the Diabetes Risk Test (DRT). The DRT consists of ten questions covering risk factors for diabetes, and provides a score for the probability of developing diabetes within five years [9, 18]. This paper describes the design of a RCT into the feasibility and (cost-) effectiveness of care provided according to the RM.

Methods

Study design

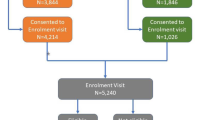

A clustered randomized controlled trial is carried out to study the feasibility and (cost-)effectiveness of the RM. Randomization takes place at the level of the general practices. The subjects in the intervention group are treated according to the RM. Persons in the control group receive care as usual, including one consultation each year, according to the T2DM guideline of the Dutch College of General Practitioners [7]. A baseline measurement takes place just after the diagnosis of IFG and just before the start of the intervention. Outcome measurements are performed one year after the diagnosis (t1, 1-year follow-up) and two years after the diagnosis (t2, 2-year follow up) (Figure 1).

Recruitment of general practices

Recruitment of general practices takes place in the North-eastern region of the Netherlands. Only practices which employ a practice nurse are included. Both, the general practitioner and the practice nurse are responsible for the recruitment and inclusion of participants.

Recruitment of participants

Potential participants are selected by opportunistic screening and active case finding. Selection criteria for both are the absence of the diagnose diabetes and age (≥45). For opportunistic screening additional selection criteria are weight (BMI ≥ 25) and the presence of cardiovascular risk factors. Opportunistic screening takes place during consultations with the general practitioner and/or practice nurse. Active screening is based on the patient files in the general practices. Selected individuals receive a mailing in which they are asked to do the DRT at home or the DRT is filled out during the consultation. If the DRT shows an increased risk of T2DM, a fasting glucose measure has to be taken.

Study population

All subjects diagnosed with IFG and motivated to change their lifestyle are included in the study. Exclusion criteria are previous education about IFG or diabetes, emotional, psychological or intellectual problems that are likely to limit the ability of the individual to comply with the protocol, malignant diseases or other diseases or conditions associated with a poor prognosis.

Training

The practice nurse carries out the intervention with support of the general practitioner, if necessary. Besides carrying out the RM, the practice nurses are responsible for the data collection. Prior to the start of the study, all practice nurses of the intervention group are trained to support them in applying the protocol. Additionally they are trained in techniques of motivational interviewing.

Randomisation

To avoid contamination of care as usual by the intervention, the randomisation takes place at the level of the general practices. General practices within the same health center are allocated to the same study group. A computerised random number generator is used to allocate the practices to the intervention or the control group.

Intervention

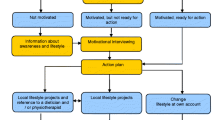

The RM protocol is based on the ‘stages of change’ model [19]. In this model change is considered as a process directed towards progress through a series of stages (precontemplation, contemplation, preparation, action and maintenance). The education and counselling of an individual persons’ needs depend on the stage he or she is in. People in the precontemplation and contemplation stage require information about the advances of a healthy lifestyle. People in the preparation stage are already aware of the advantages and disadvantages of a healthy lifestyle and require counselling and guidance to improve their ability to change their lifestyle. In the action stage, people do require tips and strategies for making the actual change. In the maintenance stage people may need additional guidance and feedback to stimulate them in maintaining their changed behaviour and to prevent relapse.

The first section of the protocol focuses on case finding and testing (Figure 2). The general practitioner is responsible for assessing subjects’ individual risk to develop T2DM. When someone is diagnosed with IFG, the second section of the RM is applied (Figure 3). This section of the protocol focuses on coaching the individual person to a healthy lifestyle. The practice nurse tries to get insight into the motivational situation of the participant. Based on this insight, three to four extra consultations spread over a one year period are carried out. During these consultations the practice nurse gives advice and teaches concrete and applicable skills in order to increase the level of physical activity and healthy dietary habits. If necessary, participants are referred to a dietician, physiotherapist, lifestyle programs and/or local sports activities. The practice nurse applies motivational interviewing techniques to determine someone’s motivational situation and to help a person to change his or her behaviour based on the model of stages of change [19, 20]. After one year participants receive care as usual.

After the initial development of the RM protocol it has been piloted on practical feasibility in different small scale pilot studies. The results of these pilots were used to improve the protocol.

Care as usual

Care as usual for those with IFG means a yearly check on diabetes-related symptoms and blood glucose levels according to the T2DM guideline of the Dutch College of General Practitioners [7].

Outcomes

The primary outcome measure in this study is change in Body Mass Index (BMI). Secondary outcome measurements are waist circumference, total and saturated fat intake, physical activity, systolic blood pressure, blood glucose, total cholesterol, triglycerides and the behaviour determinants risk perception, perceived knowledge, motivation, attitude, self efficacy and social norm.

Measurements

Medical records

The practice nurse measures body weight, blood pressure and waist circumference. Fasting plasma glucose levels, HbA1c, and serum lipids are determined in regional laboratories. Information on family history of diabetes, history of elevated blood glucose, ethnicity, other cardiovascular risk factors and comorbidity are recorded by the practice nurse. Furthermore, the practice nurse is responsible for collecting and reporting this data at three moments in time: just after the diagnosis (t0) and during the yearly follow-up consultations (t1 and t2).

Questionnaires

All participants are asked to complete a questionnaire at three different time points. The questionnaire is handed over by the practice nurse to the participants right after the diagnosis (t0) and after the yearly follow-up consultations (t1 and t2). Participants send the questionnaire directly to the researchers. The questionnaire at t0 comprises general background information on demographic characteristics (including sex, age, ethnicity, education, household composition and occupational situation). The questionnaires at t0, t1 and t2 comprise general health (including perceived health, smoking behaviour, and alcohol consumption), dietary habits (including total and saturated fat intake) [21] and physical activity (including minutes of light, moderate and intense physical activity per week) [22]. Furthermore, promoting and inhibiting factors for compliance are asked (including appreciation of care regarding to their high risk on diabetes, self-efficacy regarding lifestyle change, attitude towards lifestyle change and social norm on healthy living).

Process evaluation

A process evaluation is carried out to gather information about the care given in the intervention and control group. This evaluation consists of registration forms, questions in the questionnaire of the intervention group at t1 and t2, and face-to-face interviews with the practice nurses responsible for the study. Time spent on the intervention is recorded on registration forms. In the questionnaires participants in both groups are asked about their experiences with the offered care and referrals. In each participating general practice a face-to-face interview with the practice nurse responsible for the study takes place. During these interviews information is gathered about the inclusion of participants, the implementation of the care, the education and motivation of the practice nurses, the number of referrals, experienced motivation and treatment possibilities of the participants. In the intervention group practice nurse are asked about the perceived effect of the RM and advice for further implementation of the RM.

Sample size calculation

The sample size calculation is estimated based on BMI with the objective to detect a decrease in BMI of 0.5 in the intervention group. In the SLIM study, the standard error of the mean in change in BMI was 0.2 kg/m2 and the standard deviation 1.37 [16]. The SLIM study has a comparable population to this study, so it is assumed that the standard error and standard deviations are also comparable. To adjust for clusters, an intra-cluster correlation of 0.011 is used [23]. Furthermore, a power of 80% and a two-sided alpha of 0.05 is used. Based on these assumptions, 120 people in each group are needed.

Analysis

Effects

Multivariate variance and regression analysis are carried out to determine differences in effect on the primary and secondary outcome measures. All analyses are adjusted for baseline measurements and possible differences between both groups at baseline. To adjust for clustering, multilevel analyses are performed.

Cost-effectiveness

Costs of the care according to the RM are related to determined effects on BMI and physical activity. The cost-effectiveness is estimated by using the Chronic Disease Model (CDM) developed by the Dutch National Institute for Public Health and the Environment (RIVM) [24–26]. The CDM is a Markov type multi-transition model. The model computes life time health effects, effect on health care costs and costs per quality-adjusted life year (QALY) resulting from the minimum and maximum estimated intervention effect. A cost-effectiveness ratio of less than 20.000 euro per QALY gained is considered cost-effective [27, 28].

Discussion

The aim of the study is to investigate whether the use of the RM adds value (for money) compared to the usual care for people with IFG. The results of the study are used as input in the discussion about integrating lifestyle interventions like the RM in the Dutch health care. The study is carried out in a real life situation: in the daily care by general practices. This means that if effects are found, it is likely these effects of the intervention will sustain when the protocol is implemented on a wider scale.

Thus, the results of the study provide valuable information for both health care professionals and policy makers. When this study proves the RM to be both effective and cost-effective, it will be recommended for all healthcare professionals to integrate protocolled coaching for people with an increased risk of diabetes into daily care in general practice.

Abbreviations

- T2DM:

-

Type 2 diabetes mellitus

- IFG:

-

Impaired fasting glucose

- NDF:

-

Netherlands Diabetes Federation

- RM:

-

Route map diabetes prevention

- DRT:

-

Diabetes Risk Test

- BMI:

-

Body Mass Index

- SQUASH:

-

Short questionnaire to assess health enhancing physical activity

- t0:

-

Just after the diagnosis

- t1:

-

1-year follow-up

- t2:

-

2-year follow up

- CDM:

-

Chronic Disease Model

- RIVM:

-

Dutch National Institute for Public Health and the Environment, QUALY, health care costs and costs per quality-adjusted life year.

References

International Diabetes Federation: Diabetes Atlas 5th edition, update 2012: Retrieved October 9, 2013, from http://www.idf.org/diabetesatlas/

Nationaal Kompas Volksgezondheid. http://www.nationaalkompas.nl,

Houweling ST, Kleefstra N, Meulepas M, Romeijnders A, Klomp M, Bilo HJG: New estimates of diabetes prevalence in the Netherlands, based on information from 5 million subjects (DUDE-1). Diabetologia. 2013, 56 (Suppl 1): 291-

Blokstra A, Vissink P, Venmans LMAJ, Holleman P, van der Schouw YT, Smit HA, Verschuren WMM: The Netherlands the measure taken. Monitoring risk factors in the general population. 2012, Bilthoven: RIVM, The Netherlands, Nederland de Maat Genomen, 2009-2010. Monitoring van risicofactoren in de algemene bevolking, RIVM Utrecht report number 260152001,

Novoa FJ, Boronat M, Saavedra P, Díaz-Cremades JM, Varillas VF, La Roche F, Alberiche MP, Carrillo A: Differences in cardiovascular risk factors, insulin resistance and insulin secretion in individuals with normal glucose tolerance and in subjects with impaired glucose regulation: the Telde study. Diabetes Care. 2005, 28: 2388-2393. 10.2337/diacare.28.10.2388.

Nichols GA, Hillier TA, Brown JB: Progression from newly acquired impaired fasting glusose to type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2007, 30 (2): 228-33. 10.2337/dc06-1392.

Richtlijn diabetes van het Nederlandse huisartsengenootschap: Diabetes guideline of the Dutch College of General Practitioners. 2006, Utrecht: NHG

De Weerdt I, Kuipers B, Kok G: ‘Kijk op Diabetes’ met perspectief voor de toekomst. [‘Look at Diabetes' with prospects for the future.]. 2007, Amersfoort: Nederlandse Diabetes Federatie. Report

Uusitupa M, Lindi V, Louheranta A, Salopuro T, Lindström J, Tuomilehto J: Long-term improvement in insulin sensitivity by changing lifestyles of people with impaired glucose tolerance: 4-year results from the Finnish diabetes prevention study. Diabetes. 2003, 52 (10): 2532-8. 10.2337/diabetes.52.10.2532.

Lindstrom J, Ilanne-Parikka P, Peltonen M, Aunola S, Eriksson JG, Hemiö K, Hämäläinen H, Härkönen P, Keinänen-Kiukaanniemi S, Laakso M, Louheranta A, Mannelin M, Paturi M, Sundvall J, Valle TT, Uusitupa M, Tuomilehto J: Sustained reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes by lifestyle intervention: follow up of the Finnish diabetes prevention study. Lancet. 2006, 368: 1673-1697. 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69701-8.

Pan XR, Li GW, Hu YH, Wang JX, Yang WY, An ZX, Hu ZX, Lin J, Xiao JZ, Cao HB, Liu PA, Jiang XG, Jiang YY, Wang JP, Zheng H, Zhang H, Bennett PH, Howard BV: Effects of diet and exercise in preventing NIDDM in people with impaired glucose tolerance: the DA Qing IGT and diabetes study. Diabetes Care. 1997, 20: 537-544. 10.2337/diacare.20.4.537.

Li G, Zhang P, Wang J, Gregg EW, Yang W, Gong Q, Li H, Jiang Y, An Y, Shuai Y, Zhang B, Zhang J, Thompson TJ, Gerzoff RB, Roglic G, Hu Y, Bennett PH: The long term effect of lifestyle interventions to prevent diabetes in het China Da Quing diabetes prevention study: a 20-year follow-up study. Lancet. 2008, 371: 1783-1789. 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60766-7.

Steenbakker M, Bastiaens C, Leurs M: Vijf jaar community-based werken in Hartslag Limburg (1998–2003) [Five years of working community based in Hartslag Limburg (1998–2003)]. TSG. 2005, 2: 108-112.

De Vries M: Evaluatie Zuidoost-Drenthe HARTstikke goed!: mogelijkheden community-based preventie van hart- en vaatziekten in Nederland. [Evaluation study Zuidoost-Drenthe HARTstikke goed!: possibilities of community-based prevention of heart and vascular diseases in the Netherlands.]. 2005, Groningen: University Library Groningen

Mensink M, Feskens EJ, Saris HW, De Bruin TW, Blaak EE: Study on Lifestyle Intervention and Impaired Glucose Tolerance Maastricht (SLIM): preliminary results after one year. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2003, 279: 337-384.

Roumen C, Corpeleijn E, Feskens EJM J, Mensink M, Saris WH, Blaak EE: Impact of 3-year lifestyle intervention on postprandial glucose metabolism: the SLIM study. Diabet Med. 2008, 25 (5): 597-605. 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2008.02417.x.

van Wier MF, Lakerveld J, Bot SD, Chinapaw MJ, Nijpels G, van Tulder MW: Economic evaluation of a lifestyle intervention in primary care to prevent type 2 diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular diseases: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Fam Pract. 2013, 14 (1): 45-10.1186/1471-2296-14-45.

Lindstrom J, Tuomilehto J: The diabetes risk score: a practical tool to predict type 2 diabetes risk. Diabetes Care. 2003, 26: 725-731. 10.2337/diacare.26.3.725.

Prochaska JO, Velicer WF: The transtheoretical model of health behavior change. Am J Health Promot. 1997, 12 (1): 38-48. 10.4278/0890-1171-12.1.38.

Miller W, Rollnick S: Talking oneself into change: motivational interviewing, stages of change and therapeutic process. J Cognit Psychother. 2004, 18: 299-308. 10.1891/jcop.18.4.299.64003.

Van Assema P, Brug J, Ronda G, Steenhuis I: The relative validity of a short Dutch questionnaire as a means to categorize adults and adolescents to a total and saturated fat intake. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2001, 14 (5): 377-90. 10.1046/j.1365-277X.2001.00310.x.

Wendel-Vos GC, Schuit AJ, Saris WH, Kromhout D: Reproducibility and relative validity of the short questionnaire to assess health enhancing physical activity. J Clin Epidemiol. 2003, 56: 1163-1169. 10.1016/S0895-4356(03)00220-8.

Littenberg B, MacLean CD: Intra-cluster correlation coefficients in adults with diabetes in primary care practice: the Vermont Diabetes Information field survey. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2006, 6: 20-10.1186/1471-2288-6-20.

der Bruggen MA J-v, van Baal PH, Hoogenveen RT, Feenstra TL, Briggs AH, Lawson K, Feskens EJ, Baan CA: Cost-effectiveness of lifestyle modification in diabetic patients. Diabetes Care. 2009, 32 (8): 1453-1458. 10.2337/dc09-0363.

der Bruggen MA J-v, Bos G, Bemelmans WJ, Hoogenveen RT, Vijgen SM, Baan CA: Lifestyle interventions are cost-effective in people with different levels of diabetes risk: results from a modelling study. Diabetes Care. 2007, 30: 128-134. 10.2337/dc06-0690.

der Bruggen MA J-v, Engelfriet PM, Hoogenveen RT, van Baal PH, Struijs JN, Verschuren WM, Smit HA, Baan CA: Lipid-lowering treatment for all could substantially reduce the burden of macrovascular complications of diabetes patients in the Netherlands. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2008, 15 (5): 521-525. 10.1097/HJR.0b013e3283041523.

Simoons ML, Casparie AF: Therapie en preventie van coronaire hartziekten door verlaging van het serum cholesterol, in de derde consensus 'Cholesterol'. Consensus werkgroep CBO. [Therapy and prevention of coronary heart diseases through lowering of the serum cholesterol levels; third consensus ‘Cholesterol’. Consensus working group CBO]. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskunde. 1998, 42: 2096-2101.

Casparie AF, Van Hout BA, Simoons ML: Richtlijnen en kosten. [Guidelines and costs]. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 1998, 142: 2096-2101.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2296/14/184/prepub

Acknowledgements

This study is financed by Ministry of Health, Wellbeing and Sports (VWS) and the Netherlands Diabetes Federation (NDF) (project number 31249). The authors thank Sander Slootmaker and Lotje Bachus for all their effort in developing and testing the RM protocol.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests to disclose.

Authors’ contributions

RJ, HJGB, IW and GEHMR were responsible for study conceptualization and, design of the study. RJ, HJGB, GEHMR, AH and MM developed the analytic plan. AH drafted the manuscript. MM, HJGB, RJ, GEHMR and IW revised the manuscript. All authors approved the manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Hesselink, A.E., Bilo, H.J., Jonkers, R. et al. A cluster-randomized controlled trial to study the effectiveness of a protocol-based lifestyle program to prevent type 2 diabetes in people with impaired fasting glucose. BMC Fam Pract 14, 184 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2296-14-184

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2296-14-184