Abstract

Background

Rupture of the spleen in the absence of trauma or previously diagnosed disease is largely ignored in the emergency literature and is often not documented as such in journals from other fields. We have conducted a systematic review of the literature to highlight the surprisingly frequent occurrence of this phenomenon and to document the diversity of diseases that can present in this fashion.

Methods

Systematic review of English and French language publications catalogued in Pubmed, Embase and CINAHL between 1950 and 2011.

Results

We found 613 cases of splenic rupture meeting the criteria above, 327 of which occurred as the presenting complaint of an underlying disease and 112 of which occurred following a medical procedure. Rupture appeared to occur spontaneously in histologically normal (but not necessarily normal size) spleens in 35 cases and after minor trauma in 23 cases. Medications were implicated in 47 cases, a splenic or adjacent anatomical abnormality in 31 cases and pregnancy or its complications in 38 cases.

The most common associated diseases were infectious (n = 143), haematologic (n = 84) and non-haematologic neoplasms (n = 48). Amyloidosis (n = 24), internal trauma such as cough or vomiting (n = 17) and rheumatologic diseases (n = 10) are less frequently reported. Colonoscopy (n = 87) was the procedure reported most frequently as a cause of rupture. The anatomic abnormalities associated with rupture include splenic cysts (n = 6), infarction (n = 6) and hamartomata (n = 5). Medications associated with rupture include anticoagulants (n = 21), thrombolytics (n = 13) and recombinant G-CSF (n = 10). Other causes or associations reported very infrequently include other endoscopy, pulmonary, cardiac or abdominal surgery, hysterectomy, peliosis, empyema, remote pancreato-renal transplant, thrombosed splenic vein, hemangiomata, pancreatic pseudocysts, splenic artery aneurysm, cholesterol embolism, splenic granuloma, congenital diaphragmatic hernia, rib exostosis, pancreatitis, Gaucher's disease, Wilson's disease, pheochromocytoma, afibrinogenemia and ruptured ectopic pregnancy.

Conclusions

Emergency physicians should be attuned to the fact that rupture of the spleen can occur in the absence of major trauma or previously diagnosed splenic disease. The occurrence of such a rupture is likely to be the manifesting complaint of an underlying disease. Furthermore, colonoscopy should be more widely documented as a cause of splenic rupture.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Rupture of the spleen is relatively common both immediately and in a delayed fashion following significant blunt abdominal injury [1], and this phenomenon is well documented in the scientific literature and textbooks (e.g. [2, 3]). While less common, cases of atraumatic rupture of diseased spleens are also widely reported in the literature (reviewed in [4, 5]). In contrast, the phenomenon of splenic rupture in the absence of these two risk factors is not documented in emergency medicine textbooks [2, 3] and we believe that it is not widely appreciated by emergency physicians.

Cases of splenic rupture not fitting the description above are related by their lack of historical cues to suggest the diagnosis at presentation. This distinguishes them from other causes of splenic rupture and highlights the importance to emergency physicians who rely a great deal on the patient history to appropriately triage patients for definitive investigation and referral. A recent systematic review of cases of atraumatic rupture of the spleen has been published [4]; however, a surprising number of the splenic rupture cases reported in this review and elsewhere represent the presenting complaint of the underlying disease process. The authors of the review do not highlight this fact which we believe to be crucial information to the practicing clinician. Therefore, we have reviewed the literature on cases of splenic rupture for which there was not an immediately obvious cause apparent on presentation such as significant trauma (either recent or remote) or previously diagnosed disease known to affect the spleen.

Methods

We conducted a systematic review of English and French language papers indexed in CINAHL, PubMed and Embase using the medical subject heading (MeSH) search terms “rupture, spontaneous,” and “splenic rupture,” (or equivalent for the different databases) combined with the textword search “undiagnosed” or “first manifestation” or “presenting” or “spontaneous.” This search strategy was combined with an additional strategy including the MeSH terms “rupture, spontaneous” and “spleen” and the free text “normal spleen;” both strategies were used together to extract relevant papers. Searches were limited to English and French language papers on human subjects published in the years 1950 to 2011. We also explored multiple other textword modifiers such as “atraumatic,” “non-traumatic” and “trivial,” none of which improved the sensitivity of the search with sufficient specificity to be helpful. Searches were developed by a research librarian and one of the authors who has training in clinical epidemiology (KA).

The reference lists of the papers so identified were also examined for relevant additions. We elected to include papers written in other languages if an English language abstract was available that included the information necessary for our report. Because the information we were trying to extract was fairly straightforward, we elected to include cases from papers for which only the abstract was available to us if the necessary information was reported there.

Case reports and case series’ were examined for relevance. Data was extracted from cases referenced in review papers only if the original paper was not available to us, and these were cross-referenced with case reports to prevent duplicate recording. Papers pertaining to the rupture of diseased spleens were excluded if the disease was correctly diagnosed prior to presentation at the emergency department. Cases of splenic rupture occurring immediately following any trauma (including trivial) were also excluded. Delayed splenic rupture cases were excluded if they occurred greater than 48 hours after major trauma (because this phenomenon is well reported in the literature and textbooks), but were included if the inciting traumatic event was considered by the two authors to be of trivial severity. Although the degree of trauma is debatable, we elected to include cases likely caused by cough or vomiting because we felt that these aetiologic factors were also under-appreciated. Although delayed post-medical procedure rupture of the spleen is documented in the proceduralist (surgical and GI) literature, it is not documented in EM textbooks and we have elected to include these cases here. We limited our report to papers published since 1950. Although the diagnosis and treatment of splenic rupture has changed considerably in recent years, we found no evidence to suggest that the underlying causes of rupture have changed during this time period. Because the primary purpose of our paper was to highlight aetiology and not diagnosis or management, we elected to choose a somewhat broader time period than might have been appropriate for a study with a different purpose. The information extracted onto a spreadsheet included the splenic disease process if any, other evidence of splenic abnormality (anatomical or histological), and the nature of any associated trauma. Causative processes were grouped into clinically relevant categories. We did not attempt to document histological or pathological findings, or review diagnostic or treatment methods as these are recently reviewed in detail elsewhere [4, 5].

Results

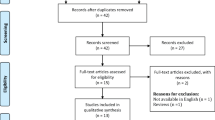

No Medical Subject Headings or other keywords reliably identified the 396 papers reporting 607 cases of splenic rupture that met our inclusion criteria. Thus, we manually reviewed many abstracts and papers that ended up being excluded from this review (Figure1). Some case series referenced here report both cases meeting our inclusion criteria and others meeting our exclusion criteria; only those meeting the inclusion criteria are included. We attempted to obtain all of the original papers referenced here so that we could document the cases without relying on secondary sources. However, sixteen of the papers were not accessible to us nor were we able to find the information necessary to fully ascertain whether the cases described within them were appropriate for this review. All cases are categorized in Figure2 and clinically relevant sub-categories are presented in Tables 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6.

PRISMA [7] flow diagram documenting number of references processed. Legend: *Only abstracts containing all necessary information were included. Abbreviations: Assoc = associated.

Discussion

Although rupture of the spleen in the absence of previously diagnosed disease or trauma is widely described as rare, given the extensive reports in the literature documented here, we believe that this descriptor should no longer be used. Although its existence is debated [1, 369, 400–402], sufficient reports from multiple authors are available to strongly suggest that rupture can occur spontaneously in otherwise normal spleens, but that this phenomenon is very rare. Given these two facts, the emergency clinician must be attuned to the possibility of splenic rupture in patients presenting with compatible symptoms without a compatible history. ED physicians must also be aware that such a presentation is very likely to be the manifesting episode of an underlying disease or anatomical abnormality. In the only other reference to these surprising findings, Renzulli found that the underlying cause for 51.2 % of the cases of atraumatic splenic rupture was not elicited until after hospital presentation [4].

In 1958, Orloff and Peskin proposed four criteria to define a true spontaneous rupture of a spleen [206], which emphasize that the spleen must appear grossly and histologically normal. In the same paper, they cite 71 reports documenting ruptures of the spleen labelled as spontaneous, only 20 of which fulfilled all of their criteria. Thus, usage of the term spontaneous was inconsistent and continues to be so in the more recent literature, with many authors labeling the rupture of diseased spleens as spontaneous. We highlight this because many of the pathological ruptures that we have documented here (as well as pathological ruptures in patients with previously known disease documented elsewhere [6]) include the word spontaneous in the title and no information on the associated pathology [8, 61, 91, 98, 124, 151, 154, 355–357, 365, 400, 403]. Thus, readers skimming titles may be mistaken in thinking that true spontaneous rupture is more common than thought.

As we have shown here, documentation of rupture of the spleen following colonoscopy is relatively common with at least 87 cases reported (Table2). However, we found only 1 such case reported in the emergency medicine literature [9], and no reference to this association in emergency medicine textbooks [2, 3] or electronic resources [404]. Although many occurrences of these cases should be evident to the endoscopist at the time of or shortly after the procedure, at least 8 documented cases have presented to the ED greater than 48 hours afterwards [10, 11, 21–23]. We have therefore elected to include these and other post-procedure cases in this review. Rupture of the spleen after other procedures appears to be very rare.

For the cases presented here with pathology in addition to the splenic rupture, there is a plausible causative relationship between the other pathology and the rupture for the vast majority. However, we have also included cases with a less clear patho-physiological relationship, such as the case reported 3 years after a pancreato-renal transplant [253], and that associated with viral hepatitis but no cirrhosis [113]. We acknowledge that the association in these cases may be coincidental and thus that these cases may better be classified as spontaneous. Although Wilson’s disease does not typically affect the spleen directly, the likely pathologic mechanism of the rupture in the case reported here is splenomegaly caused by portal hypertension [229].

We found only one case of delayed rupture of a normal spleen following trivial trauma reported in the literature in the last 60 years [392]. One other report of such a rupture in an enlarged but otherwise normal spleen [249], and reports of three others do not include information on the presence of splenic disease [393–395]. One additional case has been reported in a man 14 days after a mild fall, but the patient had also just been given heparin for a presumed myocardial infarction [396]. Given the dearth of publication in this area, the possibility remains that the associations observed in these reports are coincidental rather than causational. Regardless of the causative mechanism, these cases still meet the inclusion criteria for this review.

Limitations

The primary goal of this paper is to highlight the occurrence of splenic rupture in patients without risk factors apparent on history. A secondary purpose is to document the diverse nature of illnesses that can present in this manner. However, we have not attempted to obtain papers that were not available to us either electronically, on paper at our library or through inter-library loan. We also have not attempted to have non-English or non-French language abstracts or papers translated. The possibility remains therefore that we have missed some rare causes of splenic rupture. In addition, while a general estimate of the relative frequency of different causes of splenic rupture can be made from the numbers reported here, the numbers for those that are frequently reported such as colonoscopy, malaria and lymphoma are likely underestimated because of publication bias. Conversely, the relative frequencies of rupture for rare or novel causes are likely over-estimated.

Conclusions

Both traumatic and pathological rupture of the spleen are frequently reported in journals and documented in textbooks of emergency medicine. However, other causes of rupture are largely ignored in the emergency literature. We have documented a diverse range of patients for whom the presenting complaint for a disease was rupture of the spleen. We have also documented a number of medical procedures and medications that appear to have contributed to a rupture of the spleen, including some that have presented after the patients had been discharged from the facility conducting the procedure. Finally, we have documented several cases of trivial trauma associated with splenic rupture. Although these categories at first glance seem unrelated, they share the characteristic of having causes of rupture that would either be very subtle or completely unapparent on the presenting history, and are thus directly relevant to the practicing emergency physician. We hope that increased awareness of these phenomena will improve the ability of emergency clinicians to diagnose similar cases of splenic rupture in a timely fashion.

References

Olsen WR, Polley TZ: A Second Look at Delayed Splenic Rupture. Arch Surg. 1977, 112 (4): 422-425. 10.1001/archsurg.1977.01370040074012.

Tintinalli JE, Kelen GD, Stapczynski JS: Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Study Guide. 2004, McGraw Hill, New York, 6

Stone CK, Humphries RL: CURRENT Diagnosis & Treatment: Emergency Medicine. available at: http://www.accessmedicine.com/content.aspx?aID=3099123.: Access Medicine; 2011, 6,

Renzulli P, Hostettler A, Schoepfer AM, Gloor B, Candinas D: Systematic review of atraumatic splenic rupture. Br J Surg. 2009, 96 (10): 1114-1121. 10.1002/bjs.6737.

Debnath D, Valerio D: Atraumatic rupture of the spleen in adults. J R Coll Surg Edinb. 2002, 47: 437-445.

Renzulli P, Schoepfer A, Mueller E, Candinas D: Atraumatic splenic rupture in amyloidosis. Amyloid. 2009, 16 (1): 47-53. 10.1080/13506120802676922.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman D, Antes G: Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6 (7): e1000097-10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097.

Randriamarolahy A, Cucchi JM, Brunner P, Garnier G, Demarquay J, Bruneton JN: Two rare cases of spontaneous splenic rupture. Clin Imaging. 2010, 34 (4): 306-308. 10.1016/j.clinimag.2009.09.004.

Meier RPH, Toso C, Volonte F, Mentha G: Splenic rupture after colonoscopy. Am J Emerg Med. 2011, 29: 242-e1-242.e2

Saad A, Rex DK: Colonoscopy-induced splenic injury: Report of 3 cases and literature review. Dig Dis Sci. 2008, 53: 892-898. 10.1007/s10620-007-9963-5.

Petersen CR, Adamsen S, Gocht-Jensen P, Arnesen RB, Hart-Hansen O: Splenic injury after colonoscopy. Endoscopy. 2008, 40: 76-79. 10.1055/s-2007-966940.

DeVries J, Ronnen HR, Oomen APA, Linskens RK: Splenic rupture following colonoscopy, a rare complication. Neth J Med. 2009, 67 (6): 230-233.

Arnaud JP, Bergamaschi R, Casa C, Boyer J: Splenic rupture: unusual complication of colonoscopy. Colo-proctology. 1993, 6: 356-357.

Guerra JF, San Francisco I, Pimentel F, Ibanez L: Splenic rupture following colonoscopy. World J Gastroenterol. 2008, 14 (41): 6410-6412. 10.3748/wjg.14.6410.

Janes SEJ, Cowan IA, Dijkstra B: A life threatening complication after colonoscopy. BMJ. 2005, 330 (7496): 889-10.1136/bmj.330.7496.889.

Lalor PF, Mann BD: Splenic rupture after colonoscopy. J Soc Laparoendocsopic Surgeons. 2007, 11: 151-156.

Rao KV, Beri GD, Sterling MJ, Salen G: Splenic injury as a complication of colonoscopy: a case series. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009, 104 (6): 1604-1605.

Sarhan M, Ramcharan A, Ponnapalli S: Splenic injury after elective colonoscopy. J Soc Laparoendocsopic Surgeons. 2009, 13: 616-619.

Tse CCW, Chung KM, Hwang JST: Prevention of splenic injury during colonoscopy by positioning the patient. Endoscopy. 1998, 30: 74-75.

Wiedmann MW, Kater F, Bohm B: Splenic rupture following endoscopic polypectomy. Z Gastroenterol. 2010, 48 (4): 476-478. 10.1055/s-0028-1109605.

Ahmed A, Eller PM, Schiffman FJ: Splenic rupture: an unusual complication of colonoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997, 92: 1201-1204.

Merchant AA, Cheng EH: Delayed splenic rupture after colonoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol. 1990, 85 (7): 906-907.

Taylor FC, Frankl HD, Riemer KD: Late presentation of splenic trauma after routine colonoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol. 1989, 84 (4): 442-443.

Zyromski NJ, Camp CM: Splenic Injury: A Rare Complication of Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography. Am Surg. 2004, 70 (8): 737-739.

Lewis FW, Moloo N, Stiegmann GV, Goff JS: Splenic injury complicating therapeutic upper gastrointestinal endoscopy and ERCP. Gastrointest Endosc. 1991, 37: 632-633. 10.1016/S0016-5107(91)70872-9.

Furman G, Morgenstern L: Splenic injury and abscess complicating endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Surg Endosc. 1993, 7: 343-344. 10.1007/BF00725954.

Kingsley D, Schermer C, Jamal M: Rare complications of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography: wo case reports. JSLS. 2001, 5: 171-173.

Tronsden E, Roseland AR, Moer A, Solheim K: Rupture of the spleen following endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreotography (ERCP). Acta Chir Scand. 1989, 155: 75-76.

Ong E, Bohmler U, Wurgs D: Splenic injury as a complication of endoscopy: two case reports and a literature review. Endoscopy. 1991, 23: 302-304. 10.1055/s-2007-1010695.

Lo AY, Washington M, Fischer MG: Splenic trauma following endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP). Surg Endosc. 1994, 8: 692-693. 10.1007/BF00678569.

Wu WC, Katon RM: Injury to the liver and spleen after diagnostic ERCP. Gastrointest Endosc. 1993, 39: 824-827. 10.1016/S0016-5107(93)70278-3.

Baradaran S, Mischinger HJ, Bacher J, Werkgartner G, Karpf E, Linck FG: Spontaneous splenic rupture during portal triad clamping. Langenbecks Arch Chir. 1995, 380: 266-268.

Ben-Haim M, Emre S, Fishbein T, Sheiner PA, Miller CM, Schwartz ME: Spontaneous splenic rupture during hepatic inflow occlusion (Pringle maneuver) or total vascular isolation. Liver Transpl. 2000, 6: C19-Abstract 77

Douzdjian V, Broughan TA: Spontaneous splenic rupture during total vascular occlusion of the liver. Br J Surg. 1995, 82: 406-407. 10.1002/bjs.1800820343.

Baniel J, Bihrle R, Wahle GR, Foster RS: Splenic rupture during occlusion of the porta hepatis in resection of tumors with vena caval extension. J Urol. 1994, 151: 992-994.

Kling N, Bechstein WO, Steinmüller T, Raakow R, Jonas S: Spontaneous splenic rupture during Pringle maneuvre in liver resection for hepatic abscess. Acta Chir Austr. 1999, 31: 261-263. 10.1007/BF02620180.

Klotz S, Semik M, Senninger N, Berendes E, Scheld HH: Spontaneous splenic rupture after a left-side thoracotomy: Report of a case. Surg Today. 2003, 33 (8): 636-638. 10.1007/s00595-003-2535-1.

Stupnik T, Vidmar S, Hari P: Spontaneous rupture of a normal spleen following bronchoplastic left lung lower lobectomy. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2008, 7: 290-291.

Hunter RCJ: Gastroscopy and delayed rupture of the spleen; a review and report of a possible case. Gastroenterology. 1955, 29: 898-906.

delos Santos CA, von Eye O, Vila D, Mottin CC: Rupture of the spleen: A complication of continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis. Perit Dial Int. 1986, 6 (4): 203-204.

Marcuzzi D, Gray R, Wesley-James T: Symptomatic splenic rupture following extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy. J Urol. 1991, 145: 547-548.

Ernst D: Ruptured spleen after electric convulsion therapy. BMJ. 1980, 280: 763-

Johnson N: Traumatic rupture of the spleen: a review of eighty-five cases. ANZ J Surg. 1954, 24 (2): 112-124. 10.1111/j.1445-2197.1954.tb05079.x.

Chang MY, Shiau CS, Chang CL, Hou HC, Chiang CH, Hsieh TT, Soong YK: Spleen laceration, a rare complication of laparoscopy. J Am Assoc Gyecol Laparosc. 2000, 7 (2): 267-272.

Bahli ZM, Kennedy K: Post hysterectomy spontaneous rupture of spleen. J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad. 2009, 21 (3): 181-183.

Hoffman RL: Rupture of the spleen: a review and report of a case following abdominal hysterectomy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1972, 113: 524-530.

Habek D, Cerkez Habek J: Spontaneous splenic rupture of the spleen following abdominal hysterectomy. Zentralbl Gynakol. 2001, 123: 588-589. 10.1055/s-2001-19086.

Heidenreich W, Mlasowsky B: Spontaneous splenic rupture as a cause of postoperative hemorrhage. Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd. 1986, 46: 910-911. 10.1055/s-2008-1036345.

Hamel CT, Blum J, Harder F, Kocher T: Nonoperative treatment of splenic rupture in malaria tropica: review of literature and case report. Acta Trop. 2002, 82 (1): 1-5. 10.1016/S0001-706X(02)00025-6.

Imbert P, Rapp C, Buffet PA: Pathological rupture of the spleen in malaria: Analysis of 55 cases (1958–2008). Travel Med Infect Dis. 2009, 7 (3): 147-159. 10.1016/j.tmaid.2009.01.002.

Patel MI: Spontaneous rupture of a malarial spleen 16. Med J Aust. 1993, 159 (11–12): 836-837.

Ozsoy MF, Oncul O, Pekkafali Z, Pahsa A, Yenen OS: Splenic complications in malaria: Report of two cases from Turkey. J Med Microbiol. 2004, 53 (12): 1255-1258. 10.1099/jmm.0.05428-0.

Zingman BS, Viner BL: Splenic complications in malaria: Case report and review. Clin Infect Dis. 1993, 16 (2): 223-232. 10.1093/clind/16.2.223.

Yagmur Y, Hamdi Kara I, Aldemir M, Buyukbayram H, Tacyildiz IH, Keles C: Spontaneous rupture of malarial spleen: two case reports and review of literature. Crit Care. 2000, 4: 309-313. 10.1186/cc713.

Gupta N, Lal P, Vindal A, Hadke NS, Khurana N: Spontaneous rupture of malarial spleen presenting as hemoperitoneum: a case report. J Vector Borne Dis. 2010, 47: 119-120.

Mokashi AJ, Shirahatti RG, Prabhu SK, Vagholkar KR: Pathological rupture of malarial spleen. J Postrad Med. 1992, 38 (3): 141-142.

John BV, Ganesh A, Aggarwal S, Clement E: Persistent hypotension and splenic rupture in a patient with Plasmodium vivax and faciparum co-infection. J Postgrad Med. 2004, 50 (1): 80-81.

Rubio PA, Berkman NL: Rupture of the spleen in a Central American immigrant. Hosp Pract. 1996, 31 (1): 89-90.

Clezy JK, Richens JE: Non-operative management of a spontaneously rupture malarial spleen. Br J Surg. 1985, 72: 990-10.1002/bjs.1800721219.

Adam I, Adam ES: Spontaneous splenic rupture in a pregnant Sudanese woman with Falciparum malaria: a case report. East Mediter Health J. 2007, 13: 735-736.

Tu AS, Tran MT, Larsen CR: Spontaneous splenic rupture: Report of five cases and a review of the literature. Emerg Radiol. 1997, 4 (6): 415-418. 10.1007/BF01451078.

Ali J: Spontaneous rupture of the spleen in patients with infectious mononucleosis. Can J Surg. 1993, 36 (1): 49-52.

Coltheart G, Little JM: Splenectomy: A review of morbidity. ANZ J Surg. 1976, 46 (1): 32-36. 10.1111/j.1445-2197.1976.tb03189.x.

Hyun BH, Varga CF, Rubin RJ: Spontaneous and Pathologic Rupture of the Spleen. AMA Arch Surg. 1972, 104 (5): 652-657. 10.1001/archsurg.1972.04180050028007.

McMahon MJ, Lintott JD, Mair WSJ, Lee PWR, Duthie JS: Occult rupture of the spleen. Br J Surg. 1977, 64 (9): 641-643. 10.1002/bjs.1800640910.

Alberty R: Surgical implications of infectious mononucleosis. Am J Surg. 1981, 141 (5): 559-561. 10.1016/0002-9610(81)90048-9.

Badura RA, Oliveira O, Palhano MJ, Borregana J, Quaresma J: Spontaneous rupture of the spleen as presenting even in infectious mononucleosis. Scan J Infec Dis. 2001, 33: 872-874. 10.1080/003655401753186268.

Bonsignore A, Grillone G, Soliera M, Fiumara F, Pettinato M, Calarco G, Angio LG, Licursi M: [Occult rupture of the spleen in a patient with infectious mononucleosis] Italian. G Chir. 2010, 31 (3): 86-90.

Gauderer MWL, Stellato TA, Hutton MC: Splenic injury: Nonperative management in three patients with infectious mononucleosis. J Pediatr Surg. 1989, 24 (1): 118-120. 10.1016/S0022-3468(89)80314-8.

Gayer G, Zandman-Boddard G, Kosych E: Spontaneous rupture of the spleen detected on CT as the initial manifestation of infectious mononucleosis. Emerg Radiol. 2003, 10: 51-

Mavinamane S, Yadava R, Abood E: Spontaneous splenic rupture secondary to infectious mononucleosis [abstract]. Eur J Intern Med. 2009, 20: S219-S219.

Patel JM, Rizzolo E, Hinshaw JR: Spontaneous subcapsular splenic hematoma as the only clinical manifestation of infectious mononucleosis. JAMA. 1982, 247: 3243-3244. 10.1001/jama.1982.03320480059027.

Rotolo JE: Spontaneous splenic rupture in infectious mononucleosis. Am J Emerg Med. 1987, 5 (5): 383-385. 10.1016/0735-6757(87)90386-X.

Stephenson JT, DuBois JJ: Nonoperative management of spontaneous splenic rupture in infectious mononucleosis: A case report and review of the literature. Pediatrics. 2007, 120 (2): e432-e435. 10.1542/peds.2006-3071.

Stockinger ZT: Infectious mononucleosis presenting as spontaneous splenic rupture without other symptoms. Mil Med. 2003, 168 (9): 722-724.

Szoko M, Matolcsy A, Kovacs G, Simon G: Spontaneous splenic rupture as a complication of symptom-free infections mononucleosis. Orv Hetil. 2007, 148 (29): 1381-1384. 10.1556/OH.2007.28094.

Blaivas M, Quinn J: Diagnosis of spontaneous splenic rupture with emergency ultrasonogrophy. Ann Emerg Med. 1998, 32: 627-630. 10.1016/S0196-0644(98)70046-0.

Semrau F, Kühl R, Ritter K: Ruptured spleen and autoantibodies to superoxide dismutase in infectious mononucleosis. Lancet. 1996, 347 (9008): 1124-1125.

Johnson M, Cooperberg P, Boisvert J, Stoller J, Winrob H: Spontaneous splenic rupture in infectious mononucleosis: sonographic diagnosis and follow-up. Am J Roentgenol. 1981, 136 (1): 111-114.

Klinkert P, Kluit AB, Vries AC, Puylaert JBCM: Spontaneous Rupture of the Spleen: Role of Ultrasound in Diagnosis, Treatment, and Monitoring. Eur J Surg. 1999, 165 (7): 712-713. 10.1080/11024159950189807.

MacGowan JR, Mahendra P, Ager S, Marcus RE: Thrombocytopenia and spontaneous rupture of the spleen associated with infectious mononucleosis. Clin Lab Haematol. 1995, 17: 93-94.

Miranti JP, Rendleman DF: Spontaneous rupture of the spleen as the presenting event in infectious mononucleosis. J Am Coll Health Assoc. 1981, 30: 96-10.1080/07448481.1981.9938887.

Gordon MK, Rietveld JA, Frizelle FA: The management of splenic rupture in infetious mononucleosis. Aust N Z J Surg. 1995, 65: 247-250. 10.1111/j.1445-2197.1995.tb00621.x.

Fleming WR: Spontaneous splenic rupture in infectious mononucleosis. Aust N Z J Surg. 1991, 61: 389-390. 10.1111/j.1445-2197.1991.tb00241.x.

Peters RM, Gordon LA: Nonsurgical treatment of splenic hemorrhage in an adult with infectious mononucleosis: Case report and review. Am J Med. 1986, 80 (1): 123-125. 10.1016/0002-9343(86)90061-6.

Schuler JG, Filtzer H: Spontaneous Splenic Rupture: The Role of Nonoperative Management. Arch Surg. 1995, 130 (6): 662-665. 10.1001/archsurg.1995.01430060100020.

Purkiss SF: Splenic rupture and infectious mononucleosis-splenectomy, splenorrhaphy or non operative management. J R Soc Med. 1992, 85 (8): 458-459.

Aswani V, Visekruna M: Atraumatic splenic rupture (abstract). Wisconsin Med J. 2008, 1007: 247-

Lum D: Infectious mononucleosis. Proc UCLA Healthcare. 2005, 9: 1-3.

Al-Mashat FM, Sibiany AM: Al Amri AM: Spontaneous splenic rupture in infectious mononucleosis. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2003, 9: 84-86.

Lieberman ME, Levitt MA: Spontaneous rupture of the spleen: A case report and literature review. Am J Emerg Med. 1989, 7 (1): 28-31. 10.1016/0735-6757(89)90079-X.

Maillard N, Koenig M, Pillet S, Cuilleron M, Cathebras P: Spontaneous splenci rupture in primary cytomegalovirus infections. La Presse Medicale. 2007, 36: 874-877. 10.1016/j.lpm.2007.02.014.

Rogues AM, Dupon M, Cales V, Malou M, Paty MC, Le Bail B, Lacut JY: Spontaneous splenic rupture: an uncommon complication of cytomegalovirus infection. J Infect. 1994, 29 (1): 83-85. 10.1016/S0163-4453(94)95195-0.

Alliot C, Beets C, Besson M, Derolland P: Spontaneous splenic rupture associated with CMV infection: a report of a case and review. Scand J Infect Dis. 2001, 33: 875-877. 10.1080/00365540110027114.

Ragnaud J, Morlat P, Gin H, Dupon M, Delafaye C, du Pasquier P, Aubertin J: Aspects cliniques, biologiques et évolutifs de l'infection à cytomégalovirus chez le sujet immunocompétent: à propos de 34 patients hospitalisés. La Revue de Médecine Interne. 1994, 15 (1): 13-18.

Ali G, Kamili MA, Rashid S, Mansoor A, Lone BA, Allaqaband GQ: Spontaneous splenic rupture in typhoid fever. Postgrad Med J. 1994, 70 (825): 513-514. 10.1136/pgmj.70.825.513.

Julià J, Canet JJ, Martínez Lacasa X, González G, Garau J: Spontaneous spleen rupture during typhoid fever. Int J Infect Dis. 2000, 4 (2): 108-109. 10.1016/S1201-9712(00)90104-8.

Shivashankar GH, Kelly JF: Spontaneous splenic rupture. Surgery On-line. 2007

Winearls JR, McGloughlin S, Fraser JF: Splenic rupture as a presenting feature of endocarditis. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2009, 35 (4): 737-739. 10.1016/j.ejcts.2008.12.045.

Llanwarne N, Badic B, Delugeau V, Landen S: Spontaneous splenic rupture associated with Listeria endocarditis. Am J Emerg Med. 2007, 25 (9): 1086-e3-1086.e5

Casanova-Roman M, Casas J, Sanchez-Porto A, Nacie B: Spontaneous rupture of the spleen associated with Legionella pneumonia. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol. 2010, 21 (3): e107-e108.

Saura P, Valles J, Jubert P, Ormaza J, Sequra F: Spontaneous rupture of the spleen in a patient with legionellosis. Clin Infect Dis. 1993, 17 (2): 298-10.1093/clinids/17.2.298.

Athey RJ, Barton LL, Horgan LF, Wood BH: Spontaneous splenic rupture in a patient with pneumonia and sepsis. Acute Medicine. 2006, 5: 21-23.

Barrier JH, Bani-Sadr F, Gaillard F, Raffi F: Spontaneous rupture of the spleen revealing primary human immunodeficiency virus infection. Clin Infect Dis. 1997, 25 (2): 336-337. 10.1086/516915.

Mirchandani HG, Mirchandani IH, Pak MSY: Spontaneous rupture of the spleen due to AIDS in an IV drug abuser. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1985, 109: 1114-1116.

Vallabhaneni S, Scott H, Carter J, Treseler P, Machtinger EL: Atraumatic splenic rupture: an unusual manifestation of acute HIV infection. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2011, 25 (8): 461-464. 10.1089/apc.2011.0132.

Henderson SA, Templeton JL, Wilkinson AJ: Spontaneous splenic rupture: a unique presentation of Q fever. Ulster Med J. 1988, 57 (2): 218-219.

Baumbach A, Brehm B, Sauer W, Doller G, Hoffmeister HM: Spontaneous splenic rupture complicating acute Q fever. Am J Gastroenterol. 1992, 87 (11): 1651-1653.

Rest JG, Seid AS, Rogers D, Goldstein EJ: Pathologic rupture of the spleen due to Salmonella dublin infection. J Trauma. 1985, 25: 366-368. 10.1097/00005373-198504000-00018.

Benanti C, Arena L, Albertacci A, Rosso L: From spontaneous rupture of the spleen to septic shock in a case of salmonellosis. Acta Anaesth Italica. 2007, 58: 182-194.

Lam KY, Ng WF, Chan ACL: Miliary tuberculosis with splenic rupture: A fatal case with hemophagocytic syndrome and possible association with long standing sarcoidosis. Pathology. 1994, 26 (4): 493-493. 10.1080/00313029400169262.

Pramesh C, Tamhankar A, Rege S, Shah S: Splenic tuberculosis and HIV-1 infection. Lancet. 2002, 359 (9303): 353-

Lazaro EJ, Ong F, Parmer LP: Splenic rupture masquerading as acute appendicitis. Am Surg. 1970, 36: 705-708.

Guleria S, Dorairajan LN, Sinha S, Khazanchi R, Bal S, Guleria R: Spontaneous rupture of spleen in viral hepatitis A. Indian J Gastroenterol. 1996, 15: 30-

Fonseca AG, Amaro M, Travancinha D, Barata J: A surprising virus spontaneous spleen rupture presenting EBV infection. Abstract 67.006. 2006, 12th International Congress on Infectious Diseases (ICID), Lisbon Portugal

Tweed J: Tick trauma: tiny insect nearly did in veteran deputy. Brainerd Daily Dispatch. 2005, http://lymespot.blogspot.ca/2005_05_01_archive.html,

Dulger AC, Yilmaz M, Aytemiz E, Bartin K, Bulut MD, Kemik O, Sumer A: Spontaneous splenic rupture and hemoperitoneum due to brucellosis infection: A case report. Van Tip Dergisi. 2011, 18 (1): 41-44.

Daybell D, Paddock CD, Zaki SR, Comer JA, Woodruff D, Hansen KJ, Peacock JE: Disseminated Infection with Bartonella henselae as a Cause of Spontaneous Splenic Rupture. Clin Infect Dis. 2004, 39 (3): e21-e24. 10.1086/422001.

Redondo MC, Rios A, Cohen R, Ayala J, Martinex J, Arellano G, et al: Hemmorhagic dengue with spontaneous splenic rupture: case report and review. Clin Infect Dis. 1997, 25: 1262-1263. 10.1086/516971.

Peiper M, Broering DC, Schroter M, Rogiers X: Rupture of the spleen associated with Enterobacter cloacae. Acta Chir Belg. 1999, 99: 85-86.

McKelvey SD, Braidley PC, Stansby GP, Weir WRC: Spontaneous splenic rupture associated with murine typhus. J Infect. 1991, 22 (3): 296-297. 10.1016/S0163-4453(05)80017-9.

Schmulewitz L, Moumile K, Patey-MariousdeSerre N, Poiree S, Gouin E, Mechai F, et al: Splenic rupture and malignant Mediterranean spotted fever. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008, 14: 995-996. 10.3201/eid1406.071295.

Vial I, Hamidou M, Coste-Burel M, Baron D: Abdominal pain in varicella: an unusual cause of spontaneous splenic rupture. Eur J Emerg Med. 2004, 11: 176-177. 10.1097/01.mej.0000104026.33339.d5.

Torricelli P, Coriani C, Marchetti M, Rossi A, Manenti A: Spontaneous rupture of the spleen: Report of two cases. Abdom Imaging. 2001, 26 (3): 290-293. 10.1007/s002610000158.

Andrews DF, Hernandez R, Grafton W, Williams DM: Pathologic rupture of the spleen in non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Arch Intern Med. 1980, 140 (1): 119-120. 10.1001/archinte.1980.00330130121029.

Dobashi N, Kuraishi Y, Kobayashi T, Hirano A, Isogai Y, Takagi K: Spontaneous splenic rupture in a case of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Rinsho Ketsueki. 1993, 34 (2): 190-193.

Haj M, Zaina A, Wiess M, Cohen I, Joseph M, Horn I, Eitan A: Pathologic-spontaneous-rupture of the spleen as a presenting sign of splenic T-cell lymphoma - Case report with review. Hepatogastroenterology. 1999, 46 (25): 193-195.

Lunning MA, Stetler-Stevenson M, Silberstein PT, Zenger V, Marti GE: Spontaneous (pathological) splenic rupture in a blastic variant of mantle cell lymphoma: A case report and literature review. Clin Lymphoma. 2002, 3 (2): 117-120. 10.3816/CLM.2002.n.018.

Mason KD, Juneja SK: Spontaneous rupture of the spleen as the presenting feature of the blastoid variant of mantle cell lymphoma. Clin Lab Haematol. 2003, 25 (4): 263-265. 10.1046/j.1365-2257.2003.00522.x.

Opeskin K, Ellis D, Burke M: Anaplastic lymphoma kinase-positive anaplastic large cell lymphoma presenting with spontaneous splenic rupture. Pathology. 2004, 36 (1): 94-96. 10.1080/00313020310001643598.

Salmi R, Guadenzi P, DiTodaro F, Morandi P, Nielsen I, Manfredini R: When a car accident can change the life: Splenic lymphoma and not post-traumatic haematoma. Intern Emerg Med. 2008, 3 (3): 1007-1008.

Strickland AH, Marsden KA, McArdle J, Lowenthal RM: Pathologic Splenic Rupture as the Presentation of Mantle Cell Lymphoma. Leuk Lymphoma. 2001, 41 (1): 197-10.3109/10428190109057971.

Zieren J, Paul M, Scharfenberg M, Müller JM: The spontaneous splenic rupture as first manifestation of mantle cell lymphoma, a dangerous rarity. Am J Emerg Med. 2004, 22 (7): 629-631. 10.1016/j.ajem.2004.09.018.

Biswas S, Keddington J, McClanathan J: Large B- cell lymphoma presenting as acute abdominal pain and spontaneous splenic rupture; a case report and review of relevant literature. World J Emerg Surg. 2006, 1 (1): 35-10.1186/1749-7922-1-35.

Chen JH, Chan DC, Lee HS, Liu HD, Hsieh CB, Yu JC, Liu YC, Chen CJ: Spontaneous splenic rupture associated with hepatosplenic gammadelta T-cell lymphoma. J Formos Med Assoc. 2005, 104 (8): 593-596.

Narasimhan P, Hitti IF, Gheewala P, Pulakhandam U, Kanzer B: Unusual presentations of lymphoma: Case 3. Splenic hematoma associated with non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2002, 20: 1946-1947.

Thomson WHF: Diffuse lymphocytic lymphoma with splenic rupture. Postgrad Med J. 1969, 45: 50-51. 10.1136/pgmj.45.519.50.

Chappuis J, Simoens C, Smets D, Duttmann R, Mendes da Costa P: Spontaneous rupture of the spleen in relation to a non-Hodgkin lymphona. Acta Chir Belg. 2007, 107: 446-448.

Hebeda KM, MacKenzie MA, van Krieken JH: A case of anaplastic lymphoma kinase-positive anaplastic large cell lymphoma presenting with spontaneous splenic rupture: an extremely unusual presentation. Virchows Arch. 2000, 437: 459-464. 10.1007/s004280000251.

Soria-Aledo V, Aguilar-Domingo M, Garcia-Cuadrado J, Carrasco-Prats M, Gonzalez-Martinez P: Spontaneous rupture of the spleen: a rare form of onset of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Rev Clin Esp. 1999, 199: 552-553.

Roncella S, Cutrona G, Truini M, Airoldi I, Pezzolo A, Valetto A, Di Martino D, Dadati P, De Rossi A, Ulivi M, Fontana I, Nocera A, Valente U, Ferrarini M, Pistoia V: Late Epstein-Barr virus infection of a hepatosplenic gamma delta T-cell lymphoma arising in a kidney transplant recipient. Haematologica. 2000, 85 (3): 256-262.

Tanaka M, Minato T, Yamamura Y, Katayama K, Ishikura H, Ichimori T, et al: A case of non-Hodgkin Lymphoma presenting with spontaneous splenic rupture. Tokushima Red Cross Hospital Medical Journal. 2008, 13: 91-95.

Matsui H, Andou S, Sakakibara K, Tsuji H, Uragami T, Karamatsu S, et al: A case of spontaneous splenic rupture due to malignant lymphoma. Jpn J Gastroenterol Surg. 1994, 27: 2166-2170. 10.5833/jjgs.27.2166.

Fausel R, Sun NCJ, Klein S: Splenic rupture in a human immunodeficiency virus-infected patient with primary splenic lymphoma. Cancer. 1990, 66 (44): 2414-2416.

Hoar FJ, Chan S, Stonelake PS, Wolverson RW, Bareford D: Splenic rupture as a consequence of dual malignant pathology: a case report. J Clin Pathol. 2003, 56 (9): 709-710. 10.1136/jcp.56.9.709.

Brissette M, Dhru RD: Hodgkin's disease presenting as spontaneous splenic rupture. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1992, 116 (10): 1077-1079.

Dobrow RB: Spontaneous (pathologic) rupture of the spleen in previously undiagnosed Hodgkin's disease. Report of a case with survival. Cancer. 1977, 39 (1): 354-358. 10.1002/1097-0142(197701)39:1<354::AID-CNCR2820390154>3.0.CO;2-U.

Saba HI, Garcia W, Hartmann RC: Spontaneous ruptur eof the spleen: an unusual presenting feature in Hodgkin's lymphoma. South Med J. 1983, 76: 247-249. 10.1097/00007611-198302000-00027.

Bloom RA, Freund V, Perkes EH, et al: Acute Hodgkin's disease masquerading as splenic abscess. J Surg Oncol. 1981, 17: 279-282. 10.1002/jso.2930170310.

Beshara FM: Spontaneous rupture of the spleen in Hodgkin's lymphoma. Clin Oncol. 1982, 8: 69-71.

Amonkar SJ, Kumar EN: Spontaneous rupture of the spleen: three case reports and causative processes for the radiologist to consider. Br J Radiol. 2009, 82: e111-e113. 10.1259/bjr/81440206.

Berrebi A, Bustan A, Mashiah A, Hurwitz N: Splenic rupture as a presenting sign of lymphoma of the spleen. Isr J Med Sci. 1984, 20 (1): 66-67.

Chow MS, Taylor MA, William Hanson C: Splenic laceration associated with transesophageal echocardiography. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 1998, 12 (3): 314-316. 10.1016/S1053-0770(98)90013-1.

Rhee SJ, Sheena Y, Imber C: Spontaneous rupture of the spleen: a rare but important differential of an acute abdomen. Am J Emerg Med. 2008, 26 (6): 733-e5-733.e6

Altes A, Brunet S, Martinez C, Soler J, Ayats R, Sureda A, Lopez R, Domingo A: Spontaneous splenic rupture as the initial manifestation of acute lymphoblastic leukaemia: Immunophenotype and cytogenetics. Ann Hematol. 1994, 68 (3): 143-144. 10.1007/BF01727419.

Banerjee PK, Bhansali A, Dash S, Dash RJ: Acute lymphoblastic leukaemia manifesting with splenic rupture. J Assoc Physicians India. 1990, 38 (6): 434-435.

Bernat S, Garcia-Boyero R, Guinot M, Lopez F, Gozalbo T, Canigral G: Pathologic rupture of the spleen as the initial manifestation in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Haematalogica. 1998, 83: 760-761.

Gibbs TJ, Sells RA, Bellingham AJ: A rare presentation of splenic rupture. Postgrad Med J. 1977, 53 (621): 403-405. 10.1136/pgmj.53.621.403.

Johnson CS, Rosen PJ, Sheehan WW: Acute lymphocytic leukemia manifesting as splenic rupture. Am J Clin Pathol. 1979, 72 (1): 118-121.

McEntee GP, Duignan JP, Otridge BW, Heffeman SJ: Acute lymphocytic leukaemia presenting as spontaneous splenic rupture. I J M S. 1984, 153 (8): 284-285.

Donfrid M, Trisic B, Kraguljac N, Cemerikic V, Suvajdzic N, Colovic M: Subcapsular splenic hematoma as the initial manifestation of gammadelta + T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Haema. 2001, 4: 49-51.

Narang M, Sunita SS, Bhasin S, Sharma M, Gupta DK: Spontaneous splenic rupture - A rare initial manifestation of acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Ind J Med Paediatr Oncol. 2005, 26: 68-70.

Gorosquieta A, Pérez-Equiza E, Gastearena J: [Asymptomatic pathological rupture of the spleen as the presenting form of acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Sangre (Barc). 1996, 41: 261-262.

Rodriguez-Luaces M, Jimenez HC, Lafuente GA, Mateos RP, Hernandez-Bajo JM: Pathological ruptue of the spleen as the initial manifestation of acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Haematologica. 1998, 83: 383-384.

Carrasco CD, Yin JL: Spontaneous rupture of the spleen in a patient with B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Ann Hematol. 2005, 84: 555-556. 10.1007/s00277-005-1012-x.

Leuridan B, Sigam M, Callens J, Langeron P: Spontaneous rupture of the spleen revealing a chronic myeloid leukemia. J Sci Med Lille. 1970, 88 (10): 537-541.

Loza J, Egurbide I, Ramirez G: Spontaneous spleen rupture as presenting feature and cause of death in chronic myelogenous leukaemia. Sangre. 1979, 24 (1): 73-79.

Pelosi AJ, Sinclair DJM: Spontaneous rupture of the spleen as the presenting feature of chronic myeloid leukemia. Scott Med J. 1981, 26 (4): 352-353.

Nestok BR, Goldstein JD, Lipkovic P: Splenic rupture as a cause of sudden death in undiagnosed chronic myelogenous leukemia. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 1988, 9 (3): 241-245. 10.1097/00000433-198809000-00014.

Wang JY, Lin YF, Lin SH, Tsao TY: Hemoperitoneum due to splenic rupture in a CAPD patient with chronic myelogenous leukemia. Perit Dial Int. 1998, 18: 334-337.

Marcos-Sánchez F, Juárez-Ucelay F, Aparicio-Martínez JC, Durán-Pérez NA: Stress angina, spontaneous rupture of the spleen and almost normal leukocyte values, a rare form of presentation of chronic myeloid leukosis. An Med Interna. 1991, 8: 575-576.

Diebold J, Audoin J: Peliosis of the spleen. Report of a case associated with chronic myelomonocytic leukemia, presenting with spontaneous splenic rupture. Am J Surg Pathol. 1983, 7: 197-204.

Han J, Oh SY, Kim S, Kwon H, Hong SH, Han JY, Park K, Kim H: A case of pathologic splenic rupture as the initial manifestation of acute myeloid leukemia M2. Yonsei Med J. 2010, 51 (1): 138-140. 10.3349/ymj.2010.51.1.138.

Rajagopal A, Rmasamy R, Martin J: Acute myeloid leukemia presenting as splenic rupture. J Assoc Physicians India. 2002, 50: 1435-1437.

Serur D, Terjanian T: Spontaneous rupture of the spleen as the initial manifestation of acute myeloid leukemia. N Y State J Med. 1992, 92: 160-161.

Tan A, Ziari M, Salman H, Ortega W, Cortese C: Spontaneous rupture of the spleen in the presentation of Acute Myeloid Leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2007, 25 (34): 5519-5520. 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.1755.

Sonobe H, Uchida H, Doi K, Shinozaki Y, Kunitomo T, Ogawa K: Spontaneous rupture of the spleen in acute myeloid leukemia. Acta Pathol Jpn. 1981, 31 (2): 309-318.

Nagarsheth KH, Tucker B, Taylor D: Non-traumatic splenic rupture disguised as fall injury. Internet J Surg. 2010, 24 (1): 5p-5p.

Joubaud F, Gardais J, D'Aubigny N, Saint-Andre JP: Spontaneous rupture of the spleen in a patient with hairy cell leukemia. Semaine des Hopitaux. 1985, 61 (20): 1449-1451.

Von Der Walde J, Mashiah A, Berrebi A: Tumores rari et inusitati. Spontaneous rupture of the spleen in hairy cell leukemia. Clin Oncol. 1981, 7 (3): 241-244.

Ustün C, Sungur C, Akbas O, Sungur A, Gürgen Y, Ruacan S, et al: Spontaneous splenic rupture as the initial presentation of plasma cell leukemia: a case report. Am J Hematol. 1998, 57: 266-267.

Morla J, Masa L, Antela C, Barrio E: [Spontaneous rupture of the spleen as the form of presentation of hairy cell leukemia]. Med Clin (Barc). 1991, 96: 198-

Minato E, Fujino I, Sugihira N, Matsumoto K, Shima K, Miki C: Spontaneous Splenic Rupture in a Case of Adult T Cell Leukemia. Jpn J Gastroenterol Surg. 2003, 36 (11): 1571-1574. 10.5833/jjgs.36.1571.

Saiers JH: Acute leukemia presenting as a ruptured spleen. Report of a case. Rocky Mt Med J. 1977, 74: 319-320.

Low SE, Stafford JS: Malignant histiocytosis: a case report of a rare tumour presenting with spontaneous splenic rupture. J Clin Pathol. 2006, 59: 770-772. 10.1136/jcp.2005.027870.

de Lajarte-Thirouard AS, Molina T, Audoin J, Le Tourneau A, Leduc F, Rose C, et al: Spleen localization of light chain deposition disease associated with sea blue histiocytosis, revealed by spontaneous rupture. Virchows Arch. 1999, 434: 463-465. 10.1007/s004280050368.

Gonday G, Delluc G, Demoures A: [Sea blue histiocyte syndrome. Disclosure by spontaneous splenic rupture. Nouv Presse Med. 1982, 11: 1949-

Dawson PJ, Dawson G: Adult niemann-pick disease with sea-blue histiocytes in the spleen. Hum Pathol. 1982, 13 (12): 1115-1120. 10.1016/S0046-8177(82)80249-9.

Wilson CI, Cabello-Inchausti B, Sendzischew H, Robinson MJ: Ceroid histiocytosis: an unusual cause of traumatic splenic rupture. South Med J. 2001, 94: 237-239.

Rodon P, Ramain JP, Bruandet P, Piedon A, Akli J, Penot J: La maladie de Niemann-Pick type B avec syndrome des histiocytes bleu de mer. La Revue de Médecine Interne. 1991, 12 (4): 299-302.

Sherwood P, Sommers A, Shirfield M, Majumdar G: Spontaneous splenic rupture in uncomplicated multiple myeloma. Leuk Lymphoma. 1996, 20 (5–6): 517-519.

Levy J: Spontaneous rupture of the spleen in association with idiopathic thrombocytopaenic purpura. Postgrad Med J. 1994, 70: 239-

Sawlani KK, Gaiha M, Jain S, Shome DK, Aggarwal SB, Rani S, et al: Rare presentations of idiopathic myelofibrosis: spontaneous rupture of the spleen; pyoderma gangrenosum; and urologic obstruction. J Assoc Physicians India. 1998, 46: 230-232.

Friedrich EB, Kindermann M, Link A, Böhm M: Splenic rupture complicating periinterventional glycoprotein IIb/IIIa antagonist therapy for myocardial infarction in polycythemia vera. Z Kardiol. 2005, 94 (3): 200-204. 10.1007/s00392-005-0197-2.

Sharma D: Sub-capsular splenectomy for delayed spontaneous splenic rupture in a case of sickle cell anemia. World J Emergency Surgery. 2009, 4 (1): 17-10.1186/1749-7922-4-17.

Chim CS, Kwong YL, Shek TW, Ma SK, Ooi GC: Splenic rupture as the presenting symptom of blastic crisis in a patient with Philadelphia-negative, bcr-abl-positive ET. Am J Hematol. 2001, 66 (1): 70-71. 10.1002/1096-8652(200101)66:1<70::AID-AJH1018>3.0.CO;2-H.

Franssen CFM, Ter Maaten JC, Hoorntje SJ: Spontaneous splenic rupture in Wegener's vasculitis. Annals of Rheumatic Disease. 1993, 52: 314-10.1136/ard.52.4.314.

Hawley PH, Copland G, Zetler P: Spontaneous splenic rupture in c-ANCA positive vasculitis. Aust N Z J Medicine. 1996, 26: 431-432.

McCain M, Quinet R, Davis W, Serebro L, Zakem J, Nair P, Ishaq S: Splenic rupture as the presenting manifestation of vasculitis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2002, 31 (5): 311-316. 10.1053/sarh.2002.30636.

Fallingborg J, Lausten J, Winther P, Svanholm H: Atraumatic rupture of the spleen in periarteritis nodosa. Acta Chir Scand. 1985, 151 (1): 85-87.

Ford GA, Bradley JR, Appleton DS: Spontaneous splenic rupture in polyarteritis nodosa. Postgrad Med J. 1986, 62 (732): 965-966. 10.1136/pgmj.62.732.965.

Tolaymat A, Al-Mousily F, Haafiz AB, Lammert N, Afshari S: Spontaneous rupture of the spleen in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol. 1995, 22: 2344-2345.

Zimmerman-Gorska I, Bielaka K: Splenic rupture in the course of SLE. Pol Tyr Lek. 1971, 26: 1991-1992.

Van de Voorde K, De Raeve H, De Block CE, Van Regenmortel N, Van Offel JF, De Clerck LS, Stevens WJ: Atypical systemic lupus erythematosus or Castleman's Disease. Act Clin Belg. 2004, 59: 161-164.

Pena JM, Garcia-Alegria J, Crespo M, Gijon J, Vazquez JJ: Spontaneous rupture of the spleen in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1984, 43: 539-10.1136/ard.43.3.539.

Orloff MJ, Peskin GW: Spontaneous rupture of the normal spleen; a surgical enigma. Int Abstr Surg. 1958, 106 (1): 1-11.

Cubo T, Ramia JM, Pardo R, Martin J, Padilla D, Hernandez-Calvo J: Spontaneous rupture of the spleen in amyloidosis. Am J Emerg Med. 1997, 15 (4): 443-444. 10.1016/S0735-6757(97)90150-9.

Gupta R, Singh G, Bose SM, Vaiphei K, Radotra B: Spontaneous rupture of the amyloid spleen: a report of two cases. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1998, 26: 161-10.1097/00004836-199803000-00020.

Oran B, Wright DG, Seldin DC, McAneny D, Skinner M, Sanchorawala V: Spontaneous rupture of the spleen in AL amyloidosis. Am J Hematol. 2003, 74: 131-135. 10.1002/ajh.10389.

Hurd WW, Katholi RE: Acquired Functional Asplenia: Association With Spontaneous Rupture of the Spleen and Fatal Spontaneous Rupture of the Liver in Amyloidosis. Arch Intern Med. 1980, 140 (6): 844-845. 10.1001/archinte.1980.00330180118035.

Nowak G, Westermark P, Wernerson A, Herlenius G, Sletten K, Ericzon BG: Liver transplantation as rescue treatment in a patient with primary AL kappa amyloidosis. Transpl Int. 2000, 13: 92-97. 10.1111/j.1432-2277.2000.tb01047.x.

Okazaki K, Moriyasu F, Shiomura T, Yamamoto T, Suzaki T, Kanematsu Y, Akasaka S, Kobashi Y: Spontaneous rupture of the spleen and liver in amyloidosis - a case report and review of the literature. Gastroenterol Jpn. 1986, 21 (5): 518-524.

Mumford AD, O'Donnell J, Gillmore JD, Manning RA, Hawkins PN, Laffan M: Bleeding symptoms and coagulation abnormalities in 337 patients with AL-amylodosis. Br J Haematol. 2000, 110: 454-460. 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2000.02183.x.

Choufani EB, Sanchorawala V, Ernst T, Quillen K, Skinner M, Wright DG, Seldin DC: Acquired factor X deficiency in patients with amyloid light-chain amyloidosis: incidence, bleeding manifestations, and response to high-dose chemotherapy. Blood. 2001, 97 (6): 1885-1887. 10.1182/blood.V97.6.1885.

Tamarit Garcia JJ, Boluda Garcia F, Calvo Catala J, Campos Fernandez C, Parra Rodenas JV, Gonzalez Cruz ME, et al: [Spontaneous splenic rupture as an unusual presentation of primary amylodiosis. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 1999, 91: 653-654.

Roll GR, Lee AY, Royaie K, Visser B, Hanks DK, Knudson MM, Roll FJ: Acquired A amyloidosis from injection drug use presenting with atraumatic splenic rupture in a hospitalized patient: a case report. J Med Case Reports. 2011, 5 (1): 29-10.1186/1752-1947-5-29.

Rege JD, Kavishwar VS, Mopkar PS: Peliosis of spleen presenting as splenic rupture with haemoperitoneum-a case report. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 1998, 41 (4): 465-467.

Etzion Y, Benharroch D, Saidel M, Riesenberg K, Gilad J, Schlaeffer F: Atraumatic rupture of the spleen associated with hemophagocytic syndrome and isolated splenic peliosis. Case report. APMIS. 2005, 113: 555-557. 10.1111/j.1600-0463.2005.apm_165.x.

Celebrezze JPJ, Cottrell DJ, William GB: Spontaneous splenic rupture due to isolated splenic peliosis. Sout Med J. 1998, 91: 763-764. 10.1097/00007611-199808000-00014.

Parsons MA, Platts M, Slater D, Fox M: Splenic peliosis associated with rupture in a renal transplant patient. Postgrad Med J. 1980, 56 (661): 796-797. 10.1136/pgmj.56.661.796.

Tsokos M, Puschel J: Isolated peliosis of the spleen: report of 2 autopsy cases. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 2004, 25: 251-254. 10.1097/01.paf.0000127401.89952.65.

Lashbrook D, James R, Phillips A, Holbrook A, Agombar A: Splenic peliosis with spontaneous splenic rupture: report of two cases. BMC Surg. 2006, 6 (1): 9-10.1186/1471-2482-6-9.

Kohr RM, Haendiges M, Taube RR: Peliosis of the spleen: a rare cause of spontaneous splenic rupture with surgical implications. Am Surg. 1993, 59: 197-199.

Hakoda S, Shinya H, Kiuchi S: Spontaneous splenic rupture caused by splenic peliosis of a hemodialysis patient with chronic renal failure receiving erythropoietin. Am J Emerg Med. 2008, 26 (1): 109-e1-109.e2

Dennehy T, Lamphier TA, Wickman W, Goldberg R: Traumatic rupture of the normal spleen: Analysis of eighty-three cases. Am J Surg. 1961, 102 (1): 58-65. 10.1016/0002-9610(61)90686-9.

Moore PG, Gillies JG, James OF, Saltos N: Occult ruptured spleen–two unusual clinical presentations. Postgrad Med J. 1984, 60 (700): 171-173. 10.1136/pgmj.60.700.171.

Lloyd TV, Johnson JC: Intramural gastric hematoma secondary to splenic rupture. South Med J. 1980, 73: 1675-1676. 10.1097/00007611-198012000-00048.

Mujtaba G, Josmi J, Arya M, Anand S: Spontaneous splenic rupture: A rare complication of acute pancreatitis in a patient with Crohn's disease. Case Rep Gastroenterol. 2011, 5: 179-182. 10.1159/000327215.

Ahmed A, Feller ER: Rupture of the spleen as the initial manifestation of Wilson's disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996, 91: 1454-1455.

Holt S: Spontaneous rupture of a normal spleen diagnosed as ruptured ectopic pregnancy. Two case reports. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1982, 89 (12): 1062-1063. 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1982.tb04667.x.

Lam CM, Yuen ST, Yuen WK: Hemoperitoneum caused by spontaneous rupture of a true splenic cyst. Hepatogastroenterology. 1998, 45: 1884-1886.

Bhagrath R, Bearn P, Sanusi FA, Najjar S, Qureshi R, Simanovitz A: Postpartum rupture of the spleen. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1993, 100: 954-955. 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1993.tb15117.x.

Paravastu SC, Burdge A, da Silva A: Spontaneous splenic rupture in the postpartum period. Br J Hosp Med. 2008, 69 (2): 106-107.

Kianmanesh R, Aguirre HI, Enjaume F, Valverde A, Brugière O, Vacher B, Bleichner G: Ruptures non traumatiques de la rate: trois nouveaux cas et revue de la littérature. Spontaneous splenic rupture: report of three new cases and review of the literature. Ann Chir. 2003, 128 (5): 303-309. 10.1016/S0003-3944(03)00092-0.

Foley WJ, Thompson NW, Herlocher JE, Campbell DA: Occult rupture of the spleen. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1969, 128 (6): 1215-1220.

Mahesh B, Muwanga CL: Splenic infarct: a rare cause of spontaneous rupture leading to massive haemoperitoneum. ANZ J Surg. 2004, 74: 1030-1032. 10.1111/j.1445-1433.2004.03227.x.

Gascón A, Iglesias E, Bélvis JJ, Berisa F: The elderly haemodialysis patient with abdominal symptoms and hypovolemic shock splenic rupture secondary to splenic infarction in a patient with severe atherosclerosis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1999, 14: 1044-1045. 10.1093/ndt/14.4.1044.

Kanagasundaram NS, Macdougall IC, Turney JH: Massive haemoperitoneum due to rupture of splenic infarct during CAPD. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1998, 13 (9): 2380-2381. 10.1093/ndt/13.9.2380.

Morgenstern L, McCafferty I, Rosenberg J, Michel SL: Hamartomas of the spleen. Arch Surg. 1984, 119: 1291-1293. 10.1001/archsurg.1984.01390230057013.

Yoshizawa J, Mizuno R, Yoshida T, Kanai M, Kurobe M, Yamazaki Y: Spontaneous rupture of splenic hamartoma: A case report. J Pediatr Surg. 1999, 34 (3): 498-499. 10.1016/S0022-3468(99)90512-2.

Seyama Y, Tanaka N, Suzuki Y, Nagai M, Furuya T, Nomura Y, et al: Spontaneous rupture of splenic hamartoma in a patient with hepatitis C virus-related cirrhosis and portal hypertension: A case report and review of the literature. World J Gastroenterol. 2006, 12 (13): 2133-2135.

Ballardini P, Incasa E, Del Noce A, Cavazzini L, Martoni A, Piana E: Spontaneous splenic rupture after the start of lung cancer chemotherapy. A case report. Tumori. 2004, 90: 144-146.

Foiada M, Muller W, Conti Rossini B, Pedrinis E: [Case report of spontaneous splenic rupture in splenoma]. Helv Chir Acta. 1993, 60: 187-190.

Kesava-Rao RC G, Sawhney S, Berry M: Hemangioma of spleen with spontaneous, extra-peritoneal rupture, with associated splenic tuberculosis — an unusual presentation. Australas Radiol. 1993, 37 (1): 100-101. 10.1111/j.1440-1673.1993.tb00025.x.

Norris PM, Hughes SCA, Strachan CJL: Spontaneous Rupture of a Benign Cavernous Haemangioma of the Spleen Following Thrombolysis. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2003, 25 (5): 476-477. 10.1053/ejvs.2002.1839.

Neumann J, Ambrosius C, Zirngibl H: Spontaneous splenic rupture with diffused angiomatosis of the spleen. Chirurg. 1999, 70 (7): 800-802.

Patel VG, Eltayeb OM, Zakaria M, Fortson JK, Weaver WL: Spontaneous Subcapsular Splenic Hematoma: A Rare Complication of Pancreatitis. Am Surg. 2005, 71 (12): 1066-1069.

McMahon NG, Norwood SH, Silva JS: Pancreatic pseudocyst with splenic involvement: an uncommon complication of pancreatitis. South Med J. 1988, 81: 910-912. 10.1097/00007611-198807000-00025.

Drapanas T, Yates AJ, Brickman R, Wholey M: The Syndrome of Occult Rupture of the Spleen. AMA Arch Surg. 1969, 99 (3): 298-306. 10.1001/archsurg.1969.01340150006002.

Williams N, Gerrand C, London NJ, Chapman C, Bell PR: Splenic rupture following splenic vein thrombosis in a man with protein S deficiency. Postgrad Med J. 1992, 68 (805): 928-929. 10.1136/pgmj.68.805.928.

Windham TC, Risin SA, Tamm EP: Spontaneous Rupture of a Nontraumatic Intrasplenic Aneurysm. N Engl J Med. 2000, 342 (26): 1999-2000. 10.1056/NEJM200006293422616.

Mayo P: Spontaneous rupture of the spleen presenting as acute thoracic empyema. South Med J. 1984, 77: 1061-1062. 10.1097/00007611-198408000-00040.

Paulvannan S, Pye JK: Spontaneous rupture of a normal spleen. Int J Clin Pract. 2003, 57 (3): 245-246.

Wisniewski B, Vadrot J, D’Hubert E, Drouhin F, Fischer D, Denis J, Labayle D: Rupture spontanée de rate secondaire à une maladie des embolies de cristaux de cholestérol: à propos d’un cas. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2004, 28 (10, Part 1): 922-924. 10.1016/S0399-8320(04)95162-7.

Spearman J, Alwan MH: Atraumatic rupture of the spleen: a cautionary note. ANZ J Surg. 2006, 76 (5): 419-421.

Robb BW, Reed MF: Congenital diaghragmatic hernia presenting as splenic rupture in an adult. Ann Thorac Surg. 2006, 81: e9-e10. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2005.11.027.

Lamerton AJ: Spontaneous rupture of the spleen in early pregnancy. Postgrad Med J. 1983, 59 (695): 596-597. 10.1136/pgmj.59.695.596.

Weekes LR: Ruptured spleen as a differential diagnosis in ruptured tubal pregnancy. J Natl Med Assoc. 1984, 76: 345-349.

Buchsbaum HJ: Splenic rupture in pregnancy: report of a case and review of the literature. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 1967, 22: 381-395. 10.1097/00006254-196706000-00001.

Barnett T: Rupture of the spleen in pregnancy: a review of recorded cases with a further case report. J Obstet Gynaecol Br Emp. 1952, 59: 795-802. 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1952.tb14762.x.

Gilbert CRA, Goldzieher JW, Cook TA: Insidious rupture of the spleen or splenic vessels associated with pregnancy. J Abdom Surg. 1964, 6: 48-57.

Hunter RM, Shoemaker WC: Rupture of the spleen in pregnancy: a review of the subject and a case report. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1957, 73: 1326-1332.

Nanda S, Gulati N, Sangwan K: Spontaneous splenic rupture in early pregnancy. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1990, 31: 171-173.

O'Brien SE: Spontaneous rupture of the spleen in pregnancy. Can Med Assoc J. 1963, 89 (13): 667-668.

Cobellis L, Stradella L, Pecori E, Cobellis G: Spontaneous rupture of the spleen in pregnancy. Minerva Ginecol. 2003, 55: 289-290.

Brocas E, Tenaillon A: Spontaneous splenic rupture in the second quarter of pregnancy. Ann Fr Anesth Reanim. 2002, 21: 231-234. 10.1016/S0750-7658(02)00601-9.

Landa Aranzabal MA, Tubia Landaberea JI, Esteban Aldezabal L, Carbajal Cervino C, Berdejo Lambarri L: Rotura espontanea de bazo. Presentacion de un caso registrado en una gestante. Cir Esp. 1991, 49: 459-460.

Fletcher H, Frederick J, Barned H, Lizarraga V: Spontaneous rupture of the spleen in pregnancy with splenic conservation. West Indian Med J. 1989, 38: 114-115.

de Graaff J, Pijpers PM: Spontaneous rupture of the spleen in third trimester of pregnancy. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1987, 25: 243-247. 10.1016/0028-2243(87)90105-5.

Kiran G, Himsweta S: Spontaneous splenic rupture in pregnancy - a rare entity. J Obstet Gynecol India. 2007, 57: 545-546.

Thakkar U: Spontaneous rupture of spleen. Med J Zambia. 1981, 15 (2): 32-34.

Bljajić D, Ivanisević M, Djelmis J, Majerović M, Starcević V: Splenic rupture in pregnancy - traumatic or spontaneous event?. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2004, 115: 113-114. 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2003.10.028.

Popli K, Chitra R, Puri M: Spontaneous rupture of spleen in term pregnancy. Trop Doct. 2004, 34: 54-55.

Epstein M, King R, Kenney D: Splenic rupture at term. Case report. Mo Med. 1983, 80: 83-84.

Londero F, Cociancich G: Spontaneous rupture of the spleen in labor. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000, 183: 782-783. 10.1067/mob.2000.106557.

Touré B, Ouattara T, Ouédraogo A, Ouédraogo CMR, Koné B: [Splenic rupture during delivery. A case report. Journal Européen des Urgences. 2004, 17: 87-89.

Denehy T, McGrath EW, Breen JL: Splenic torsion and rupture in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 1988, 43 (3): 123-131.

Sparkman RS: Rupture of the spleen in pregnancy. Am J Obst and Gynecol. 1958, 76: 587-598.

Huber DE, Martin SD, Orlay G: A case report of splenic pregnancy. Aust N Z J Surgery. 1984, 54: 81-82. 10.1111/j.1445-2197.1984.tb06692.x.

Michaud P, Robillot P, Tescher M: Spontaneous rupture of the spleen in relation to a splenic pregnancy. Apropos of a case. Rev Fr Gynecol Obstet. 1988, 83: 281-282.

Kalof AN, Fuller B, Harmon M: Splenic pregnancy. A case report and review of the literature. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2004, 128: e146-e148.

Caruso V, Hall WH: Primary abdominal pregnancy in the spleen: a case report. Pathology. 1984, 16: 93-94. 10.3109/00313028409067918.

Reddy KSP, Modgill VK: Intraperitoneal bleeding due to primary splenic pregnancy. Br J Surg. 1983, 70: 564-10.1002/bjs.1800700920.

Larkin JK, Garcia DM, Paulson EL, Powers DW: Primary splenic pregnancy with intraperitoneal bleeding and shock: a case report. Iowa Med. 1988, 78: 529-530.

Yackel DB, Panton ON, Martin DJ, Lee D: Splenic pregnancy - a case report. Obstet Gynecol. 1988, 71: 471-473.

Kahn JA, Skjeldestad FE, Düring V, Sunde A, Molne K, Jørgensen OG: A spleen pregnancy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1989, 68: 83-84. 10.3109/00016348909087696.

Cormio G, Santamato S, Vimercati A, Selvaggi L: Primary splenic pregnancy. A case report. J Reprod Med. 2003, 48: 479-481.

Sakhel K, Aswad N, Usta I, Nassar A: Postpartum splenic rupture. Obstet Gynecol. 2003, 102: 1207-1210. 10.1016/S0029-7844(03)00676-8.

McCormick GM, Young DB: Spontaneous rupture of the spleen. A fatal complication of pregnancy. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 1995, 16: 132-134. 10.1097/00000433-199506000-00010.

Kaluarachchi A, Krishnamurthy S: Post-cesarean section splenic rupture. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1995, 173: 230-232. 10.1016/0002-9378(95)90199-X.

Huang YH, Hsu CY, Chang YF, Chen CP: Postcesarean splenic torsion. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2006, 45: 257-259. 10.1016/S1028-4559(09)60237-0.

Barrilleaux PS, Adair D, Johnson G, Lewis DF: Splenic rupture associated with severe preeclampsia. A case report. J Reprod Medicine. 1999, 44: 899-901.

Manda P, Dorman E, Olagbaiye F, Akinfenwa O: A case report of spontaneous splenic capsular rupture associated with atypical presentation of haemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, low platelet count (HELLP) syndrome. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2004, 24 (3): 317-318. 10.1080/01443610410001661002.

Maier A, Bataille F, Krenz D, Anthuber M: Angiosarcoma as a rare differential diagnosis in spontaneous rupture of the spleen. Der Chirurg. 2004, 75: 70-74. 10.1007/s00104-003-0733-4.

Miyata T, Fujimoto Y, Fukushima M, Torisu M, Tanaka M: Spontaneous rupture of splenic angiosarcoma: A case report of chemotherapeutic approach and review of the literature. Surg Today. 1993, 23: 370-374. 10.1007/BF00309058.

Aranha GV, Gold J, Grage TB: Hemangiosarcoma of the spleen: report of a case and review of previously reported cases. J Surg Oncol. 1976, 8: 481-487. 10.1002/jso.2930080607.

Reale A, Petrogalli F: Hemangiosarcome of the spleen. Report of a case. Pathologica. 1996, 88 (1): 49-51.

Simanski DA, Schiby G, Dreznik Z, Jacob ET: Rapid progressive dissemination of hemangiosarcoma of the spleen following spontaneous rupture. World J Surg. 1986, 10 (1): 142-145. 10.1007/BF01656109.

Sivelli R, Piccolo D, Soliani P, Franzini C, Ziegler S, Sianesi M: Rupture of the spleen in angiosarcoma: a case report and review of the literature. Chir Ital. 2005, 57: 377-380.

Wick MR, Scheithauer BW, Smith SL, Beart RWJ: Primary nonlymphoreticular malignant neoplasms of the spleen. Am J Surg Pathol. 1982, 6: 229-242. 10.1097/00000478-198204000-00005.

Winde G, Sprakel B, Bosse A, Reers B, Wendt M: Rupture of the spleen caused by primary angiosarcoma. Case report. Acta Chir Eur J Surg. 1991, 157 (3): 215-217.

Villedieu Poignant S, Mermet L, Bousquet A, Dupont P: Une cause rare d'hémopéritoine spontané. La Revue de Médecine Interne. 2000, 21 (9): 809-811.

Safarpor D, Safapor F, Aghajanzade M, Kohsari M, Hoda S: Spontaneous rupture of the spleen: A case report and review of the literature. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2007, 13 (3): 136-137. 10.4103/1319-3767.33466.

Falk S, Krishnan J, Meis JM: Primary angiosarcoma of the spleen. A clinicopathologic study of 40 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1993, 17: 959-970. 10.1097/00000478-199310000-00001.

Hsu JT, Chen HM, Lin CY, Yeh CN, Hwang TL, Jan YY, et al: Primary angiosarcoma of the spleen. J Surg Oncol. 2005, 92: 312-316. 10.1002/jso.20419.

Neuhauser TS, Derringer GA, Thompson LD, Fanburg-Smith JC, Miettinen M, Saaristo A, et al: Splenic angiosarcoma: a clinicopathologic and immunophenotypic study of 28 cases. Mod Pathol. 2000, 13: 978-987. 10.1038/modpathol.3880178.

Mahony B, Jeffrey RB, Federle MP: Spontaneous rupture of the hepatic and splenic angiosarcoma demonstrated by CT. Am J Roentgenol. 1983, 138: 965-966.

Thompson WM, Levy AD, Aguilera NS, Gorospe L, Abbott RM: Angiosarcoma of the Spleen: Imaging Characteristics in 12 Patients. Radiology. 2005, 235 (1): 106-115. 10.1148/radiol.2351040308.

Catalano O, Sandomenico F, Raso MM, Siani A: Real-time, contrast-enhanced sonography: A new tool for detecting active bleeding. J Trauma. 2005, 59: 933-939. 10.1097/01.ta.0000188129.91271.ab.

Kristoffersson A, Emdin S, Jarhult J: Acute intestinal obstruction and splenic hemmorrhage due to metastatic choriocarcinoma. A case report. Acta Chir. 1985, 454: 381-384.

Ghinescu C, Sallami Z, Jackson D: Choriocarcinoma of the spleen - a rare cause of atraumatic rupture. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2008, 90: W12-W14.

Hou HC, Chen CJ, Chang TC, Hsieh TT: Metastatic choriocarcinoma with spontaneous splenic rupture following term pregnancy: a case report. Changgeng Yi Xue Za Zhi. 1996, 19: 166-170.

Lam KY, Tang V: Metastatic Tumors to the Spleen. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2000, 124 (4): 526-530.

Challis DE, Rew KJ, Steigrad SJ: Choriocarcinoma complicated by splenic rupture: an unusual presentation. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 1996, 22: 395-400.

Giannakopoulos G, Nair S, Snider PS, Amenta C: Implications for the pathogenesis of aneurysm formation: Metastatic choriocarcinoma with spontaneous splenic rupture. Case report and a review. Surg Neurol. 1992, 38 (3): 236-240. 10.1016/0090-3019(92)90175-M.

Smith WM, Lucas JG, Frankel WL: Splenic rupture: A rare presentation of pancreatic carcinoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2004, 128 (10): 1146-1150.

Chung S, Park K, Li AK: A pancreatic tumour presenting as a ruptured spleen. HPB Surg. 1989, 1: 161-163. 10.1155/1989/82783.

Patrinou V, Skroubis G, Zolota V, Vagianos C: Unusual presentation of pancreatic mucinous cystadenocarcinoma by spontaneous splenic rupture. Dig Surg. 2000, 17: 645-647. 10.1159/000051979.

Yettimis E, Trompetas V, Varsamidakis N, Courcoutsakis N, Polymeropoulos V, Kalokairinos E: Pathologic splenic rupture. An unusual presentation of pancreatic cancer. Pancreas. 2003, 27: 273-274.

Otero-Palleiro MM, Barbagelata-Lopez C: Spontaneous rupture of the spleen: a rare form of onset gastric carcinoma]. Med Clin (Barc). 2006, 127: 318-

Gupta PB, Harvey L: Spontaneous rupture of the spleen secondary to metastatic carcinoma. Br J Surg. 1993, 80: 613-10.1002/bjs.1800800522.

Lachachi F, Abita T, Durand Fontanier S, Maisonnette F, Descottes B: Spontaneous splenic rupture due to splenic metastasis of lung cancer. Ann Chir. 2004, 129: 521-522. 10.1016/j.anchir.2004.09.001.

Kyriacou A, Arulraj N, Varia H: Acute abdomen due to spontaneous splenic rupture as the first presentation of lung malignancy: a case report. J Med Case Reports. 2011, 5: 444-10.1186/1752-1947-5-444.

Tresallet C, Thibault F, Cardot V, Baleston F, Nguyen-Thanh Q, Chigot JP, et al: Spontaneous splenci rupture during intrasplenic Kaposi's sarcoma in an HIV-positive patients. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2005, 29: 1296-1297. 10.1016/S0399-8320(05)82227-4.

Charters JW, Prince G, McGarry JM: Granulosa cell tumour presenting with haemoperitoneum and splenic rupture. Case report. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1989, 96: 735-736.

Hassan KS, Cohen HI, Hassan FK, Hassan SK: Unusual case of pancreatic inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor associated with spontaneous splenic rupture. World J Emerg Surg. 2010, 5 (1): 28-10.1186/1749-7922-5-28.

Burg MD, Dallara JJ: Rupture of a previously normal spleen in association with enoxaparin: An unusual cause of shock. J Emerg Med. 2001, 20 (4): 349-352. 10.1016/S0736-4679(01)00310-9.

Weiss SJ, Smith T, Laurin E, Wisner DH: Spontaneous splenic rupture due to subcutaneous heparin therapy. J Emerg Med. 2000, 18 (4): 421-426. 10.1016/S0736-4679(00)00157-8.

Blankenship JC, Indeck M: Spontaneous splenic rupture complicating anticoagulant or thrombolytic therapy. Am J Med. 1993, 94 (4): 433-437. 10.1016/0002-9343(93)90156-J.

Kapan M, Kapan S, Karabicak I, Bavunoglu I: Simultaneous rupture of the liver and spleen in a patient on warfarin therapy: report of a case. Surg Today. 2005, 35: 252-255. 10.1007/s00595-004-2898-y.

Ghobrial MW, Karim M, Mannam S: Spontaneous splenic rupture following the administration of intravenous heparin: case report and retrospective case review. Am J Hematol. 2002, 71: 314-317. 10.1002/ajh.10214.

Abad C, Fernández-Bethencourt M, Ortiz E, Rodríguez San Román JL, Facal P, Avila R: Spontaneous rupture of the spleen in a patient hypercoagulated with dicumarol. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 1992, 81: 366-367.

Badaoui R, Chebboubi K, Delmas J, Jakobina S, Mahjoub Y, Riboulot M: Rupture de la rate et anticoagulant. Ann Fr Anesth Reanim. 2004, 23 (7): 748-750. 10.1016/j.annfar.2004.04.018.

Gernigon Y, Beaumont E, Griffe J: Rupture spontanée de la rate chez un malade traité par les anticoagulants. Arch Med Ouest. 1980, 12: 163-167.

Jabbour M, Tohmé C, Ingea H, Farah P: Spontaneous splenic rupture due to heparin. Report of a case and review of the literature. J Med Liban. 1995, 43: 107-109.

Reches A, Almog R, Pauzner D, Almog B, Levin I: Spontaneous splenic rupture in pregnancy after heparin treatment. BJOG. 2005, 112: 837-838. 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2005.00531.x.

Kim H, Lee G, Park DJ, Lee JD, Chang S: Spontaneous splenic rupture in a hemodialysis patient. Yonsei Med J. 2005, 46 (3): 435-438. 10.3349/ymj.2005.46.3.435.

Jayamaha AS, Patel JK, Orlikowski C: Splenic rupture following streptokinase therapy. Intensive Care Med. 1994, 20: 244-10.1007/BF01704713.

Gardner-Medwin J, Sayer J, Mahida YR, Spiller RC: SPONTANEOUS RUPTURE OF SPLEEN FOLLOWING STREPTOKINASE THERAPY. Lancet. 1989, 334 (8676): 1398-

Wiener RS, Ong LS: Streptokinase and splenic rupture. Am J Med. 1989, 83: 249-

Lambert GW, Cook PS, Gardiner GA, Regan JR: Spontaneous splenic rupture associated with thrombolytic therapy and/or concomitant heparin anticoagulation. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 1992, 15: 177-179. 10.1007/BF02735583.

Cheung PK, Arnold JM, McLarty TD: Splenic hemorrhage: a complication of tissue plasminogen activator treatment. Can J Cardiol. 1990, 6: 183-185.

Watring NJ, Wagner TW, Stark JJ: Spontaneous splenic rupture secondary to pegfilgrastim to prevent neutropenia in a patient with non–small-cell lung carcinoma. Am J Emerg Med. 2007, 25 (2): 247-248. 10.1016/j.ajem.2006.10.005.

Arshad M, Seiter K, Bilaniuk J, Qureshi A, Patil A, Ramaswamy G, et al: Side effects related to cancer treatment: Case 2. Splenic rupture following pefgilgrastim. J Clin Oncol. 2005, 23: 8533-8534.

Falzetti F, Aversa F, Minelli O, Tabilio A: Spontaneous rupture of spleen during peripheral blood stem-cell mobilisation in a healthy donor. Lancet. 1999, 353 (9152): 555-

Dincer AP, Gottschall J, Margolis DA: Splenic rupture in a parental donor undergoing peripheral blood progenitor cell mobilization. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2004, 26: 761-763. 10.1097/00043426-200411000-00015.

Pitini V, Ciccolo A, Arrigo C, Aloi G, Micali C, La Torre F: Spontaneous rupture of spleen during periferal blood stem cell mobilization in a patient with breast cancer. Haematologica. 2000, 85 (5): 559-560.

Rossitto M, Versaci A, Barbera A, Broccio M, Lepore V, Ciccolo A: Spontaneous rupture of the spleen in a patient treated with chemotherapy and growth factors for stem cell mobilization]. G Chir. 1998, 19: 204-206.

de Lezo Suarez j, Torres A, Herrera I, Pan M, Romero M, Pavlovic D, et al: Effects of stem-cell mobilization with recombinant human granulocyte colony stimulating factor in patients with percutaneously revascularized acute anterior myocardial infarction. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2005, 58: 253-261. 10.1157/13072472.

Balaguer H, Galmes A, Ventayol G, Bargay J, Besalduch J: Splenic rupture after granulocyte-colony-stimulating factor mobilization in a peripheral blood progenitor cell donor. Transfusion. 2004, 44: 1260-1261. 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2004.00413.x.

Becker PS, Wagle M, Matous S, Swanson RS, Pihan G, Lowry PA, et al: Spontaneous splenic rupture following administration of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF): occurrence in an allogeneic donor of peripheral blood stem cells. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 1997, 3: 45-49.

Stuart D, Wolfer R: Spontaneous splenic rupture following administration of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF): a rare but fatal complication. J Surg Res. 2007, 137: 306-307.

Loizon P, Nahon P, Founti H, Delecourt P, Rodor F, Jouglard J: Spontaneous rupture of the spleen under ticlopidine. Apropos of two cases. J Chir (Paris). 1994, 131: 371-374.

Mitchell C, Riley CA, Vahid B: Unusual Complication of Heparin-Induced Thrombocytopenia After Mitral Valve Surgery: Spontaneous Rupture of Spleen. Ann Thorac Surg. 2007, 83 (3): 1172-1174. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2006.08.047.

Buciuto R, Kald A, Borch K: Spontaneous rupture of the spleen. Eur J Surg. 1992, 158 (2): 129-130.

Morrin FJ, Guiney E: Spontaneous rupture of the normal spleen. Ir J Med Sci. 1960, 36 (11): 500-505.

Rice JP, Sutter CM: Spontaneous splenic rupture in an active duty Marine upon return from Iraq: a case report. J Med Case Reports. 2010, 4: 353-10.1186/1752-1947-4-353.

Arnold RE, Van Vooren A: Spontaneous rupture of the spleen with hematoma. South Med J. 1975, 68 (7): 863-864. 10.1097/00007611-197507000-00013.

Grech A: Spontaneous rupture of spleen. Br Med J. 1971, 1 (5740): 111-

Lennard TW, Burgess P: Vomiting and "spontaneous" rupture of the spleen. Br J Clin Pract. 1985, 39: 407-410.

Toubia NT, Tawk MM, Potts RM, Kinasewitz GT: Cough and spontaneous rupture of a normal spleen. Chest. 2005, 128 (3): 1884-1886. 10.1378/chest.128.3.1884.

Wehbe E, Raffi S, Osborne D: Spontaneous splenic rupture precipitated by cough: a case report and a review of the literature. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2008, 43 (5): 634-637. 10.1080/00365520701763472.

Wergowske GL, Carmody TJ: Splenic Rupture From Coughing. Arch Surg. 1983, 118 (10): 1227-a-

Kara E, Kaya Y, Zeybek R, Coskun T, Yavuz C: A case of diaphragmatic rupture complicated with laceration of stomach and spleen caused by a violent cough presenting with mediastinal shift. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2004, 33 (649): 650-

Thomas WEG: Apparent spontaneous rupture of the spleen. Br Med J. 1978, 1 (6110): 409-410.