Abstract

Background

We have examined the association between adiposity and cardiac structure in adulthood, using a life course approach that takes account of the contribution of adiposity in both childhood and adulthood.

Methods

The Childhood Determinants of Adult Health study (CDAH) is a follow-up study of 8,498 children who participated in the 1985 Australian Schools Health and Fitness Survey (ASHFS). The CDAH follow-up study included 2,410 participants who attended a clinic examination. Of these, 181 underwent cardiac imaging and provided complete data. The measures were taken once when the children were aged 9 to 15 years, and once in adult life, aged 26 to 36 years.

Results

There was a positive association between adult left ventricular mass (LVM) and childhood body mass index (BMI) in males (regression coefficient (β) 0.41; 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.14 to 0.67; p = 0.003), and females (β = 0.53; 95% CI: 0.34 to 0.72; p < 0.001), and with change in BMI from childhood to adulthood (males: β = 0.27; 95% CI: 0.04 to 0.51; p < 0.001, females: β = 0.39; 95% CI: 0.20 to 0.58; p < 0.001), after adjustment for confounding factors (age, fitness, triglyceride levels and total cholesterol in adulthood). After further adjustment for known potential mediating factors (systolic BP and fasting plasma glucose in adulthood) the relationship of LVM with childhood BMI (males: β = 0.45; 95% CI: 0.19 to 0.71; p = 0.001, females: β = 0.49; 95% CI: 0.29 to 0.68; p < 0.001) and change in BMI (males: β = 0.26; 95% CI: 0.04 to 0.49; p = 0.02, females: β = 0.40; 95% CI: 0.20 to 0.59; p < 0.001) did not change markedly.

Conclusions

Adiposity and increased adiposity from childhood to adulthood appear to have a detrimental effect on cardiac structure.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Background

Cardiac structure and functional changes are known to predict morbidity and mortality in later life and may be linked to modifiable factors in early life. Cohort studies have shown childhood risk factors influence the subsequent risk of coronary heart disease in adult life. For example, vascular endothelial dysfunction, an early stage in the development of atherosclerosis, has been demonstrated in children [1] long before any substantial risk factor burden is identifiable [2]. Cross-sectional studies of children and youth have demonstrated elevations in left ventricular mass (LVM) in association with elevated blood pressure [3], type 1 diabetes [4] and increased body mass index (BMI) [5, 6]. This association is of major interest as it is well established that adults with left ventricular (LV) hypertrophy, a consequence of increased LVM, are at an increased risk of myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure and cardiovascular disease (CVD) mortality [7, 8].

The few longitudinal studies to examine the association of adiposity (primarily BMI) in childhood and change in adiposity from childhood to adulthood with cardiac structure have largely allowed for the confounding effect of lipids and sex, and the mediating effect of systolic BP [9–11], these studies have not considered physical fitness or glucose metabolism as a potential confounder of the association in the primary analyses [11]. Given that diabetes exerts adverse effects on systolic and diastolic LV function independent of hypertension and coronary artery disease [12–14]; that this association is evident well below the threshold for diabetes [15]; and that fitness impacts on cardiac structure [16], assessment of these factors (both confounding and mediating) in early to mid-adulthood is warranted. Furthermore, previous longitudinal studies have used body mass index (BMI) in childhood as the measure of body size or obesity, but have not differentiated between fat and lean mass, which may have different and perhaps opposing effects on cardiac structure.

The Childhood Determinants of Adult Health study (CDAH) is a longitudinal, population-based cohort of young adults followed since childhood in Australia. This provides an important opportunity to examine the association between adiposity (potential predictor) and cardiac structure in adulthood (outcome), using a life course approach that takes account of the contribution of adiposity in both childhood and adulthood.

Methods

Study population

The CDAH study is a population-based, prospective cohort study established to examine childhood predictors of adult CVD and diabetes. The CDAH study design and procedures have been described in detail elsewhere but will be summarized here [17, 18]. Extensive lifestyle and biological data were collected in 1985 (baseline) on a representative sample of 8498 school children aged 7 to 15 years as part of the Australian Schools Health and Fitness Survey [19]. A sub-sample of 2809 children (9, 12 and 15 year-olds) underwent additional measurements, including blood pressure, blood lipids, and further fitness tests. These additional measurements were restricted to a sub-sample owing to economic and time constraints. The follow-up study, CDAH, was performed from May 2004 to May 2006. A total of 2410 were re-measured at one of 34 field-work clinics across Australia. The population was then aged 26–36 years. During the follow-up survey, a random sample of 204 participants (approximately 1 in 3 participants with relevant childhood measures as 9, 12 and 15 year-olds) had M-mode echocardiography performed. Complete data for these analyses were available on 181 participants. Echocardiography was restricted to a sub-sample owing to time constraints of field-clinics and the need to reduce respondent burden. Participants who received echocardiography were similar to those clinic attendees who did not have the examination with respect to BMI, total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), triglycerides, insulin, and glucose, but had higher mean (SD) systolic (121 (13) vs 117 (13)) and diastolic (75 (9) vs 72 (9)) blood pressure, and waist circumference (86.0 (12.5) vs 83.6 (12.3)). The childhood characteristics of those with cardiac measures were also very similar to those who did not attend the follow-up study as adults on the following measures: BMI, waist circumference, total cholesterol, LDL-C, triglycerides, systolic and diastolic BP. Those with cardiac measures, however, had higher mean (SD) HDL-C (1.52 (0.31) vs 1.45 (0.28)).

At baseline, consent from both parent and child was required for inclusion in the study; at follow-up, all participants gave written informed consent. The baseline study was approved by the State Directors General of Education and the follow-up survey was approved by the Southern Tasmania Health and Medical Human Research Ethics Committee.

Weight was measured with participants in light clothes without shoes using regularly calibrated bathroom scales that recorded to the nearest 0.5 kg in 1985, and with a digital Heine portable scale that recorded to the nearest 0.1 kg at follow-up. Standing height was measured to the nearest 0.1 cm using a portable stadiometer, with the participant in bare feet. BMI was calculated using the formula: BMI = weight (kg)/height (m) [2]. Childhood overweight and obesity for BMI were defined using age and sex specific cut-points [20]. Waist circumference was measured to the nearest 0.1 cm on the skin or over light clothing. At baseline, the measurement was taken at the level of the umbilicus with a constant tension tape. At follow-up, a non-stretch tape was used to obtain the measurement at the narrowest point between the lower costal border and iliac crest.

Fat mass and percent body fat at baseline and follow-up was estimated from established regression equations that incorporate four measures of skin fold thickness. In 1985, tricep, bicep, subscapular, and suprailiac skin folds were measured at locations determined by reference to anatomical landmarks [21] using Holtain Calipers to the nearest 0.1 mm. Three readings were taken from each site, and the readings were then averaged. At follow-up, tricep, bicep, subscapular, and iliac crest skin folds were measured using Slim Guide calipers to the nearest 0.5 mm. Measurements were repeated a maximum of three times, or discontinued if the first two readings were unchanged. The average of the two closest readings was used as the location specific score. As we have previously detailed [22], skin fold values exceeding 40 mm at follow-up were imputed from BMI and waist circumference. Body density was estimated using regression equations for 9 [23], 12 and 15 year old children [24] at baseline, and for adults at follow-up [21]. Body density was then used for the calculations of fat mass and percent body fat [25].

Cardiorespiratory fitness was estimated sub-maximally at baseline and follow-up as physical working capacity at a heart rate of 170 beats per minute (PWC170) on a friction-braked bicycle ergometer (Monark Exercise AB, Sweden). The test protocol comprised three successive workloads of three minutes duration at baseline, or four minutes duration at follow-up. The workloads were selected on an individual basis to induce steady-state heart rate responses from the participant at the end of each workload. Heart rate was recorded during the final 20 seconds of each workload. Physical work capacity at 170 beats per minute was estimated by extrapolating the line of best fit from the heart rates recorded at each sub-maximal workload [26, 27]. Cardiorespiratory fitness is expressed in relative terms as watts per kg (W/kg) of lean body mass.

Blood pressure measurements were obtained from the left brachial artery using a standard mercury sphygmomanometer at baseline, and from the right brachial artery using a digital automatic monitor (Omron HEM907, Omron Healthcare Inc, Kyoto, Japan) at follow-up. Blood pressure levels are reported as the mean of two measurements at baseline and the mean of three measurements at follow-up.

Blood samples were collected at baseline and follow-up from the antecubital vein after an overnight fast. In 1985, serum total cholesterol and triglycerides were determined according to the Lipids Research Clinic Program [28], and HDL-C analyzed following precipitation of apolipoprotein-B containing lipoproteins with heparin-manganese [19]. In 2004–2006, serum total cholesterol, triglyceride, and HDL-C concentrations were determined enzymatically [18]. LDL-C concentration was calculated using the Friedewald formula [29]. At follow-up only, plasma glucose levels were measured enzymatically using the Olympus AU5400 automated analyser. Two methods of insulin determination were used during the follow-up study. Plasma insulin was measured by a microparticle enzyme immunoassay kit (AxSYM, Abbot Laboratories, Abbot Park, Illinois, USA) initially, before a change in kit by the laboratory to measure serum insulin determined by electrochemiluminescence immunoassay (Elecsys Modular Analytics E170; Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Switzerland). Insulin levels assayed using the first methodology were corrected to levels in participants assayed using the second methodology (as per correction factor equation of the laboratory).

Echocardiography

Two-dimensional M-mode echocardiography was performed using a portable Acuson Cypress (Siemens Medical Solutions USA Inc., Mountainview, CA) ultrasound system with a 1.8-3.6 MHz cardiac transducer by a single technician who traveled to field clinics. The left ventricle was first visualised from B-mode images obtained from the standard parasternal long-axis view. Once a clear image was obtained, the M-mode line of sight was angled perpendicular to the left ventricle between the tip of the mitral valve and papillary muscle. All images were stored on the system’s hard-drive for off-line measurement by a single technician, blinded to the participants status (obese versus non-obese). Measurements were obtained using the machine’s internal programmed calipers. End-diastolic and end-systolic measurements were made from a single cardiac cycle and then repeated on a second cardiac cycle with the measurements averaged. Cardiac measures included: inter-ventricular septum thickness (IVST), left ventricular internal diameter (LVID), left ventricular posterior wall thickness (PWT), ejection fraction, stroke volume, cardiac output and cardiac index. Images used for measurement were given a subjective rating of image quality by the technician with 1 = excellent, 2 = average, and 3 = unacceptable. Six participants had images that were graded as unacceptable and were not used for the analyses. Left ventricular mass (LVM) was calculated by the necropsy-validated formula described by Devereux: [30] LVM = {0.8 [1.04 ((IVSTd + LVIDd + PWTd)3 - LVIDd3)] + 0.6}. Left ventricular mass index (LVMI) was calculated by dividing LVM by height(m)2.7. Relative wall thickness (RWT) was calculated by dividing the sum of left ventricular PWT and IVST by LVID. Septal to PWT ratio was calculated by dividing IVST by PWT.

The authors of this manuscript have certified that they comply with the Principles of Ethical Publishing in the International Journal of Cardiology [31].

Statistical methods

The data analysis was performed with Stata software (Stata Inc., 2009, Texas, USA). Means and standard deviations (or medians and interquartile ranges) were used to summarize quantitative variables and percentages were used to summarize categorical variables.

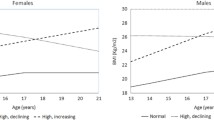

In order to provide a graphical illustration of the associations between adiposity measures and LVMI, separate categorical variables describing pattern of change between childhood and adulthood in adiposity status were created. For each adiposity measure (BMI, waist circumference, fatmass and skinfold thickness) those in the highest quartile (age and sex specific) were defined as overweight/obese. For this analysis the top quartile of each adiposity measure was used to allow direct comparison across the adiposity measures. The resulting categories of change were: (1) normal weight as child and normal weight as adult; (2) overweight/obese as child and normal weight as adult; (3) normal weight as child and overweight/obese as adult; (4) overweight/obese as child and overweight/obese as adult. We present means on the LVMI outcome for each adiposity change category.

The relationship between quantitative measures of adiposity and LVM/LVMI was estimated separately for males and females using linear regression. LVM was used to assess BMI as LVMI is indexed to height. This was undertaken as the association between adiposity and CVD risk is linear. Relationships were estimated separately for the four indicators of adiposity: BMI, waist circumference, fat mass and skinfold thickness. A life course epidemiologic approach was used that simultaneously takes account of the contribution of adiposity in both childhood and adulthood [32]. Adiposity and change in adiposity were modeled as continuous predictors in the regression models. Change is based on taking the difference of continuous scores.

Models were fitted in which childhood adiposity and change in adiposity between childhood and adulthood were used as predictors (Model 1); the first model was extended to adjust for potential confounding factors in adulthood: fitness, age, triglyceride levels and total cholesterol (Model 2); finally a third model also included potential mediating factors in adulthood: systolic BP and FPG (Model 3). In these models the regression coefficient for the child adiposity variable is the difference in the mean cardiac outcome between subjects who are one unit apart in their adiposity level at both childhood and adulthood (e.g. subject A is one unit higher in BMI than subject B at both time points). If the association were causal it would represent the effect of an increase of 1 unit in adiposity at both childhood and adulthood. The coefficient for the change in adiposity variable quantifies the mean increase in the cardiac outcome associated with a one unit difference in change (e.g. comparing cardiac outcome between two children whose changes in adiposity are 1 unit apart, say an increase of 2 units versus an increase of 1 unit).

Results

Two hundred and four (204) participants underwent cardiac imaging and of these 181 had complete data available and acceptable echocardiography images. The characteristics of the participants are shown in Table 1. The mean age of participants in childhood was 12 years (range 7 to 15 years) and in adulthood 31 years (range 27 to 37 years). 54% of the sample was male. Change in BMI between participants in the sub-sample and data collected on a further 4500 participants at the time of enrollment in the follow-up study showed that the cardiac sub-sample underwent a similar mean change in BMI from childhood to adulthood to the rest of the cohort (6.8 kg/m2 vs. 7.1 kg/m2).

Table 2 shows the echocardiographic measures by childhood and adulthood BMI category. The table is presented combined for males and females, due to the small number of overweight and obese children (n = 16). In childhood, a pattern of higher values was observed among those in the overweight or obese category for LVM, LVMI, LV diameter in diastole and systole and PWT in systole and diastole compared with those with a BMI within the normal range. In adulthood those in the overweight and obese category had a higher LVM, LVMI, LV diameter in diastole and systole, PWT and IVST. Figures 1a to d show the mean (age and sex specific) LVMI and 95% CI by categories of change in BMI, waist circumference, fat mass and skinfold thickness, respectively. The overall p-value for each adiposity measure by LVMI was significant at the 5% level. For each adiposity measure, (BMI, waist circumference, fat mass and skin fold thickness) there was an indication of higher LVMI in those who were overweight in both childhood and adulthood or only overweight in childhood.

The results from the linear regressions of adult echocardiographic measures (LVM and LVMI on adiposity are shown in Table 3. LVM was used in these models when assessing BMI. In both males and females, there was a positive association between childhood BMI and LVM and a positive association between change in BMI and LVM (model 1).

Adjustment for confounding factors (in adulthood: age, fitness, triglycerides and total cholesterol), had little impact on the estimated regression coefficients (Model 2). This association did not change with adjustment for both age in childhood and adulthood or stratification by age group, with the exception of change in skinfold thickness and fat mass in females aged 11 to 15 years and BMI change in males aged 7–10 years, which were no longer significant.’ These relationships also changed little after further adjustment for mediating factors from adulthood (systolic BP and FPG, Model 3). In Model 3 the coefficient for BMI in childhood for males was 0.45 (95% CI: 0.19 to 0.71; p = 0.001) and for females was 0.49 (95% CI: 0.29 to 0.68; p < 0.001). The coefficient for change in BMI for males was 0.26 (95% CI: 0.04 to 0.49; p = 0.02) and for females was 0.40 (95% CI: 0.20 to 0.59; p < 0.001). Analyses that replaced BMI with waist circumference, fat mass or skinfold thickness in separate analyses also showed evidence of associations with LVMI in females (Table 3). When direct measures of fat (skinfold thickness and fatmass) were used the associations were much weaker than for BMI and only significant in females.

The models were additionally re-run replacing FPG with fasting insulin to assess the potential mediating impact of insulin on LVM. There was little change in the association of BMI with LVM after adjustment for the mediating impact of insulin: the regression coefficient for BMI in childhood for males was 0.47 (95% CI: 0.20 to 0.73; p = 0.001) and for females was 0.49 (95% CI: 0.29 to 0.69; p < 0.001). The coefficients for change in BMI for males was 0.28 (95% CI: 0.02 to 0.55; p = 0.04) and for females was 0.40 (95% CI: 0.20 to 0.59; p < 0.001).

Discussion

The present study determined that childhood adiposity and change in adiposity (using several different measures of adiposity) from childhood to adulthood is associated with cardiac structure. The association with change in adiposity was independent of childhood adiposity. While previous research has suggested an association between adiposity and LVM in adolescence [34–36] and in adulthood [9–11], only one previous study has had more than 14 years of follow-up allowing assessment of the association into the third decade of life [11].

This study extends the work of the few longitudinal studies undertaken by assessing four measures of adiposity (BMI, waist circumference, fat mass and skin fold thickness, in separate models), taking a life course approach and allowing for key potential factors that might introduce confounding on these associations, separately in males and females. Overall, our results suggest that adiposity in childhood and adulthood and change in adiposity between childhood and adulthood, are associated with LVMI in adulthood. In particular, when direct measures of fat (skinfold thickness and fatmass) are used the associations were much weaker than for BMI and only significant in females, which may be related to sex hormones [37]. The risk of increased LVM/LVMI appears to be greatest among those who are overweight in childhood and adulthood, supporting the results of earlier studies.

The few longitudinal studies to examine the association of adiposity in childhood and change in adiposity from childhood to adulthood with cardiac structure have largely allowed for the confounding effect of lipids and sex, and the mediating effect of systolic BP. These studies have not considered physical fitness as a potential confounder of the association in the primary analyses [11]. The Bogalusa Heart study with 21 years of follow-up assessed cardiac structure in a subgroup of 467 young adults aged 20–38 years (mean age 32.6 years) [11]. The study showed that those with a higher BMI in childhood had larger LVM 21 years later, and those with a higher BMI in both childhood and adulthood had the largest cardiac size, with adjustment for lipids (HDL and LDL cholesterol and triglycerides) and blood pressure. The Bogalusa Heart study similarly found no mediating role for fasting glucose when assessed at a mean age of 19 years [38], with an association between diabetes and left ventricular hypertrophy evident at the 24 year follow-up [39].

In a 10 year follow-up study of African American and European American youth (mean age at baseline 14 years) with a positive family history of CVD, Dekkers et al. [9] found an increased BMI was a strong predictor of LVM. The study assessed a number of important risk factors (including SBP, pulse pressure, heart rate, ethnicity and father’s education). A further study undertaken by Sivanandam et al. [10] of 132 healthy children, at a mean age of 13 years and re-evaluated 14 years later showed that adiposity and LVM were related in childhood and that the greater the increase in BMI from childhood through to adult life the greater the increase in LVM. This study investigated the association of LVM with glucose and fasting insulin after adjustment for BMI and showed no association. Studies in adolescent and adult populations have shown mixed results for glycaemia, largely as a consequence of assessing small samples with limited power to detect associations. In the present study there was little evidence of fasting plasma glucose being associated with increased LVM or other measures of cardiac structure. Fitness is known to impact on cardiac structure [16]. In this sample adjusting for fitness did not reduce the association of adiposity with cardiac measures.

Increased adiposity is directly linked to other CVD risk factors. It is well-established that as adiposity increases so too do other CVD risk factors, i.e. blood pressure and total cholesterol. Elevated blood pressure related to obesity increases the heart’s workload and leads to cardiac growth. In the present population, blood pressure did not mediate the association of adiposity (for any of the adiposity measures) with cardiac structure. There are several mechanisms linking adiposity with adverse changes in cardiac structure and function. Of particular interest is research providing a direct link between increased adiposity and cardiac growth. It is well acknowledged that central fat is metabolically active and leads to the activation of a series of pathophysiologic processes including activation of the renin-angiotensin system and development of insulin resistance [40]. Several studies have demonstrated an association between adiposity and cardiac structure among those who are obese but not hypertensive and have shown that chronic volume overload (increased preload) and the related increased cardiac output may stimulate cardiac growth [41]. This interpretation has been supported by a number of studies and appears to be supported by the present study, as the impact of adiposity on cardiac measures was not explained by BP.

The present study has several limitations including its small sample size. Further work should be undertaken on a large population-based cohort with long follow-up, as understanding the cardiac impacts will provide insights into the likely trajectory of development of cardiac disease in individuals who are overweight or obese. It may also provide valuable information on the differences in the rate of progress of components of the pathogenic process when obesity and insulin resistance occur at an early age. Bias due to subject selection is unlikely to explain the current study results. For example, the baseline population characteristics of those with cardiac data at follow-up were similar to those who did not attend follow-up, with the exception of HDL-C. HDL-C is not an established risk factor for change in cardiac structure or function, so we do not expect this difference to have impacted on our findings. Moreover, because echocardiographs were not collected in childhood, we were unable to discount that children with increased adiposity had larger hearts already in childhood. Finally, any sex differences need to be further confirmed in studies with larger sample sizes.

Conclusions

The impact of childhood risk factors on cardiac structure is not fully understood. This study has shown that childhood and adulthood adiposity and increased adiposity from childhood to adult life are associated with poorer cardiac structure in adulthood independent of other known factors that impact on cardiac structure. This suggests that changes in cardiac structure begin to develop in youth as a consequence of obesity.

References

Woo KS, Chook P, Yu CW, Sung RY, Qiao M, Leung SS, Lam CW, Metreweli C, Celermajer DS: Overweight in children is associated with arterial endothelial dysfunction and intima-media thickening. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2004, 28: 852-857.

Leeson CP, Kattenhorn M, Morley R, Lucas A, Deanfield JE: Impact of low birth weight and cardiovascular risk factors on endothelial function in early adult life. Circulation. 2001, 103: 1264-1268.

Schieken RM, Clarke WR, Lauer RM: Left ventricular hypertrophy in children with blood pressures in the upper quintile of the distribution. The muscatine study Hypertension. 1981, 3: 669-675.

Suys BE, Katier N, Rooman RP, Matthys D, Op De Beeck L, Du Caju MV, De Wolf D: Female children and adolescents with type 1 diabetes have more pronounced early echocardiographic signs of diabetic cardiomyopathy. Diabetes Care. 2004, 27: 1947-1953.

Lorber R, Gidding SS, Daviglus ML, Colangelo LA, Liu K, Gardin JM: Influence of systolic blood pressure and body mass index on left ventricular structure in healthy african-american and white young adults: The cardia study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003, 41: 955-960.

Chinali M, de Simone G, Roman MJ, Lee ET, Best LG, Howard BV, Devereux RB: Impact of obesity on cardiac geometry and function in a population of adolescents: The strong heart study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006, 47: 2267-2273.

Levy D, Garrison RJ, Savage DD, Kannel WB, Castelli WP: Prognostic implications of echocardiographically determined left ventricular mass in the framingham heart study.[see comment]. N Engl J Med. 1990, 322: 1561-1566.

Gardin JM, McClelland R, Kitzman D, Lima JA, Bommer W, Klopfenstein HS, Wong ND, Smith VE, Gottdiener J: M-mode echocardiographic predictors of six- to seven-year incidence of coronary heart disease, stroke, congestive heart failure, and mortality in an elderly cohort (the cardiovascular health study). Am J Cardiol. 2001, 87: 1051-1057.

Dekkers C, Treiber FA, Kapuku G, Van Den Oord EJ, Snieder H: Growth of left ventricular mass in african american and european american youth. Hypertension. 2002, 39: 943-951.

Sivanandam S, Sinaiko AR, Jacobs DR, Steffen L, Moran A, Steinberger J: Relation of increase in adiposity to increase in left ventricular mass from childhood to young adulthood. Am J Cardiol. 2006, 98: 411-415.

Li X, Li S, Ulusoy E, Chen W, Srinivasan SR, Berenson GS: Childhood adiposity as a predictor of cardiac mass in adulthood: The bogalusa heart study. Circulation. 2004, 110: 3488-3492.

Kosmala W, Kucharski W, Przewlocka-Kosmala M, Mazurek W: Comparison of left ventricular function by tissue doppler imaging in patients with diabetes mellitus without systemic hypertension versus diabetes mellitus with systemic hypertension. Am J Cardiol. 2004, 94: 395-399.

Fang ZY, Yuda S, Anderson V, Short L, Case C, Marwick TH: Echocardiographic detection of early diabetic myocardial disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003, 41: 611-617.

Liu JE, Palmieri V, Roman MJ, Bella JN, Fabsitz R, Howard BV, Welty TK, Lee ET, Devereux RB: The impact of diabetes on left ventricular filling pattern in normotensive and hypertensive adults: The strong heart study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001, 37: 1943-1949.

Chaturvedi N, McKeigue PM, Marmot MG, Nihoyannopoulos P: A comparison of left ventricular abnormalities associated with glucose intolerance in african caribbeans and europeans in the uk. Heart. 2001, 85: 643-648.

Venckunas T, Raugaliene R, Mazutaitiene B, Ramoskeviciute S: Endurance rather than sprint running training increases left ventricular wall thickness in female athletes. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2008, 102: 307-311.

Venn AJ, Thomson RJ, Schmidt MD, Cleland VJ, Curry BA, Gennat HC, Dwyer T: Overweight and obesity from childhood to adulthood: A follow-up of participants in the 1985 australian schools health and fitness survey. Med J Aust. 2007, 186: 458-460.

Magnussen CG, Raitakari OT, Thomson R, Juonala M, Patel DA, Viikari JS, Marniemi J, Srinivasan SR, Berenson GS, Dwyer T, Venn A: Utility of currently recommended pediatric dyslipidemia classifications in predicting dyslipidemia in adulthood: Evidence from the childhood determinants of adult health (cdah) study, cardiovascular risk in young finns study, and bogalusa heart study. Circulation. 2008, 117: 32-42.

Dwyer T, Gibbons LE: The australian schools health and fitness survey. Physical fitness related to blood pressure but not lipoproteins Circulation. 1994, 89: 1539-1544.

Cole TJ, Freeman JV, Preece MA: British 1990 growth reference centiles for weight, height, body mass index and head circumference fitted by maximum penalized likelihood. Stat Med. 1998, 17: 407-429.

Durnin JV, Womersley J: Body fat assessed from total body density and its estimation from skinfold thickness: Measurements on 481 men and women aged from 16 to 72 years. Br J Nutr. 1974, 32: 77-97.

Dwyer T, Magnussen CG, Schmidt MD, Ukoumunne OC, Ponsonby AL, Raitakari OT, Zimmet PZ, Blair SN, Thomson R, Cleland VJ, Venn A: Decline in physical fitness from childhood to adulthood associated with increased obesity and insulin resistance in adults. Diabetes Care. 2009, 32: 683-687.

Brook CG: Determination of body composition of children from skinfold measurements. Arch Dis Child. 1971, 46: 182-184.

Durnin JV, Rahaman MM: The assessment of the amount of fat in the human body from measurements of skinfold thickness. Br J Nutr. 1967, 21: 681-689.

Siri W: Gross composition of the body. Advances in biological and medical physics. Edited by: Lawrence JH TC. 1956, New York: Accademic Press

Sjostrand T: Changes in the respiratory organs of workmen at an ore smelting works. Acta Med Scand. 1947, 196 (Suppl): 687-699.

Wahlund H: Determination of the physical working capacity. Acta Med Scand. 1948, 215 (Suppl): 1-78.

Lipid research clinics program: Manual of laboratory operations: Lipid and lipoprotein analysis. 1974, Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health: US Dept of Health, Education and Welfare publication NIH, 75-628.

Friedewald WT, Levy RI, Fredrickson DS: Estimation of the concentration of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in plasma, without use of the preparative ultracentrifuge. Clin Chem. 1972, 18: 499-502.

Devereux RB, Alonso DR, Lutas EM, Gottlieb GJ, Campo E, Sachs I, Reichek N: Echocardiographic assessment of left ventricular hypertrophy: Comparison to necropsy findings. Am J Cardiol. 1986, 57: 450-458.

Coats AJ, Shewan LG: Statement on authorship and publishing ethics in the international journal of cardiology. Int J Cardiol. 2011, 153: 239-240.

De Stavola BL, Nitsch D, dos Santos SI, McCormack V, Hardy R, Mann V, Cole TJ, Morton S, Leon DA: Statistical issues in life course epidemiology. Am J Epidemiol. 2006, 163: 84-96.

Cole TJ, Bellizzi MC, Flegal KM, Dietz WH: Establishing a standard definition for child overweight and obesity worldwide: International survey. BMJ. 2000, 320: 1240-1243.

Janz KF, Dawson JD, Mahoney LT: Predicting heart growth during puberty: The muscatine study. Pediatrics. 2000, 105: E63-

Urbina EM, Gidding SS, Bao W, Pickoff AS, Berdusis K, Berenson GS: Effect of body size, ponderosity, and blood pressure on left ventricular growth in children and young adults in the bogalusa heart study. Circulation. 1995, 91: 2400-2406.

Schieken RM, Schwartz PF, Goble MM: Tracking of left ventricular mass in children: Race and sex comparisons: The mcv twin study. Medical college of virginia.[see comment]. Circulation. 1998, 97: 1901-1906.

Parks RJ, Howlett SE: Sex differences in mechanisms of cardiac excitation-contraction coupling. Arch Eur J Physiol. 2013, 465: 747-763.

Urbina EM, Gidding SS, Bao W, Elkasabany A, Berenson GS: Association of fasting blood sugar level, insulin level, and obesity with left ventricular mass in healthy children and adolescents: The bogalusa heart study. Am Heart J. 1999, 138: 122-127.

Toprak A, Wang H, Chen W, Paul T, Srinivasan S, Berenson G: Relation of childhood risk factors to left ventricular hypertrophy (eccentric or concentric) in relatively young adulthood (from the bogalusa heart study). Am J Cardiol. 2008, 101: 1621-1625.

Govindarajan G, Alpert MA, Tejwani L: Endocrine and metabolic effects of fat: Cardiovascular implications. Am J Med. 2008, 121: 366-370.

Schunkert H: Obesity and target organ damage: The heart. Int J Obesity Relate Metabolic Disorders J Int Assoc Study Obesity. 2002, 26 (Suppl 4): S15-S20.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2261/14/79/prepub

Acknowledgments

We thank the contributions of the Childhood Determinants of Adult Health Study’s staff and volunteers, in particular, project manager Marita Dalton, and the study participants who made this study possible.

Source of funding

The Australian Schools Health and Fitness Survey was supported by the Commonwealth Departments of Sport, Recreation and Tourism, and Health; The National Heart Foundation; and the Commonwealth Schools Commission. The Childhood Determinants of Adult Health study, was supported by: the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council, the Australian National Heart Foundation, the Tasmanian Community Fund, and Veolia Environmental Services. Financial support was also provided by: Sanitarium Health Food Company, ASICS Oceania, and Target Australia. C.G.M. is supported by the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Early Career Public Health Fellowship (Grant No. 1037559). OU is supported by the Peninsula Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care (CLAHRC), a collaboration between the University of Exeter, University of Plymouth, and National Health Service South West, funded by the National Institute for Health Research. No funding organization had any role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

RT undertook the data analyses, interpretation of the data, drafting of the manuscript and giving final approval of the version to be published. AV participated in the study design, interpretation of the analyses, revising the manuscript and giving final approval of the version to be published. LH assisted with the data analyses, revising the manuscript and giving final approval of the version to be published. OR assisted with interpretation of the data, drafting of the manuscript and giving final approval of the version to be published. OU assisted with interpretation of the data, drafting of the manuscript and giving final approval of the version to be published. TD participated in the study design, interpretation of the analyses, revising the manuscript and giving final approval of the version to be published. CM assisted with the interpretation of the data, drafting of the manuscript and giving final approval of the version to be published. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Tapp, R.J., Venn, A., Huynh, Q.L. et al. Impact of adiposity on cardiac structure in adult life: the childhood determinants of adult health (CDAH) study. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 14, 79 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2261-14-79

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2261-14-79