Abstract

Background

Early stages in the excitation cascade of Limulus photoreceptors are mediated by activation of Gq by rhodopsin, generation of inositol-1,4,5-trisphosphate by phospholipase-C and the release of Ca2+. At the end of the cascade, cGMP-gated channels open and generate the depolarizing receptor potential. A major unresolved issue is the intermediate process by which Ca2+ elevation leads to channel opening.

Results

To explore the role of guanylate cyclase (GC) as a potential intermediate, we used the GC inhibitor guanosine 5'-tetraphosphate (GtetP). Its specificity in vivo was supported by its ability to reduce the depolarization produced by the phosphodiesterase inhibitor IBMX. To determine if GC acts subsequent to InsP3 production in the cascade, we examined the effect of intracellular injection of GtetP on the excitation caused by InsP3 injection. This form of excitation and the response to light were both greatly reduced by GtetP, and they recovered in parallel. Similarly, GtetP reduced the excitation caused by intracellular injection of Ca2+. In contrast, this GC inhibitor did not affect the excitation produced by injection of a cGMP analog.

Conclusion

We conclude that GC is downstream of InsP3-induced Ca2+ release and is the final enzymatic step of the excitation cascade. This is the first invertebrate rhabdomeric photoreceptor for which transduction can be traced from rhodopsin photoisomerization to ion channel opening.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Phototransduction processes in invertebrates have both similarities and differences from that in vertebrate rods. The initial enzymatic step in all photoreceptors is the activation of G protein by rhodopsin. In the ciliary photoreceptors of vertebrate rods and cones, G protein activates phosphodiesterase leading to a decrease of cGMP concentration, closure of cyclic nucleotide-gated channels and membrane hyperpolarization (for review see [1]). On the other hand, the ciliary photoreceptors from scallops, hyperpolarize due to an increase in cGMP which opens a K+ selective conductance [2]. In invertebrate rhabdomeric photoreceptors, which also depolarize in response to light, no complete transduction cascade has been determined. It is clear that G protein activates phospholipase C in all cases examined so far, including Drosophila [3–5], Limulus [6, 7] and squid [8, 9]. PLC then hydrolyzes phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate to produce inositol-1,4,5-trisphosphate and diacylglycerol.

Subsequent steps differ among these photoreceptors. In late stages of the excitation cascade in Drosophila, diacylglycerol (or metabolites) may lead to channel opening [10, 11]. However, understanding the final stages has been hampered by the unavailability of a direct assay for the light-dependent channels and varying results using heterologous expression systems [12]. In the photoreceptors of Limulus ventral eye (for review see [13]), the cascade involves PLC, InsP3, Ca2+ and cGMP. Light produces an InsP3-induced Ca2+ elevation that precedes the onset of the receptor potential [14]. Furthermore, intracellular injection of Ca2+ mimics the light response [15–17] and buffering intracellular Ca2+ inhibits it [16, 18]. Taken together, these results establish that InsP3-mediated Ca2+ elevation is an integral part of the excitation cascade. The Limulus cascade ends with the opening of cGMP-gated channels which, in this system, can be directly studied in cell-attached and excised patches [19, 20]. Photoreceptor cells contain mRNA for a putative Limulus cyclic nucleotide-gated channel protein, and antibodies to the expressed protein specifically label the light-sensitive rhabdomeric lobe [21, 22]. Furthermore either intracellular injection of cGMP [23, 24] or elevation of cGMP by inhibition of phosphodiesterase [25, 26] excites the cell. There is thus little doubt that the end of the cascade involves cGMP-gated channels. What remains unclear is the mechanism that couples Ca2+ release to cGMP elevation.

Recent work demonstrated that inhibitors of guanylate cyclase strongly reduce the response to light [27]. Although these results support the requirement for cGMP during excitation, they do not indicate at which stage GC is involved. In this paper, we test the hypothesis that GC is a missing link in the cascade; i.e. that it acts downstream from Ca2+ elevation as required if cGMP is to couple Ca2+ elevation to channel opening. Our results indicate that this is indeed the case. Because PDE inactivation is unlikely to be involved in excitation (see Discussion), it appears that activation of GC is what elevates cGMP. It is therefore now possible to a give a rather complete picture of this complex cascade that couples rhodopsin photoisomerization to ion channel opening.

Results

Guanylate cyclase antagonists oppose the effects of PDE inhibitors

Inhibitors of PDE raise cGMP levels in the Limulus eyes [26] and produce a depolarization of the photoreceptor membrane [25]. GC inhibitors should counteract this effect. To reduce PDE activity, 2.5 mM IBMX was added to the bath for several minutes. Fig. 1A shows that this evoked a 24 mV membrane depolarization in this cell (control). Once the cell recovered following wash-out of IBMX, GC inhibitor was injected. We used the competitive GC inhibitor guanosine 5'-tetraphosphate because it can be injected with greater ease and effects reverse more quickly than with other antagonists [27]. GtetP was injected until it decreased the light response by at least 80%. IBMX was then reapplied. Under these conditions, the peak depolarization caused by IBMX of 11 mV was 54% smaller compared to what occurred before GtetP injection (Fig. 1A, GtetP). The maximum slope of the depolarization also decreased: during control perfusion of IBMX, the maximum was 13.6 mV/min, and after injections the maximum slope was 6.1 mV/min. In ten experiments, the average decrease of depolarization was 56 ± 24% (Fig. 1B) and the average decrease in the maximal rising slope was 60 ± 20% (Fig. 1C). These results are consistent with GtetP inhibiting GC, thereby opposing the increase in cGMP resulting from PDE inhibition.

Guanosine 5'-tetraphosphate decreased and slowed the depolarization produced by 2.5 mM IBMX. (A) Bath application of 2.5 mM IBMX produced a characteristic depolarization of Limulus photoreceptors (control) that was diminished following intracellular pressure injection sufficient to inhibit the light response from a microelectrode containing 25 mM GtetP (GtetP). (B) Amplitudes of IBMX-induced depolarization in individual photoreceptors are matched before and after inhibition of the light response using GtetP. The thick line indicates the average decrease in depolarization (n = 10). (C) The maximum rising slopes of IBMX-induced depolarization in the same photoreceptors as in (B) are matched before and after inhibition of the light response using GtetP. The thick line indicates the average decrease in rising slope.

GC inhibitors act downstream from InsP3 mediated Ca2+release

In order to provide a link between light-induced Ca2+ elevation and the opening of cGMP-dependent channels, GC activity must be downstream from Ca2+ in the signaling cascade. To determine if this is the case, photoreceptors were excited by injecting InsP3 or Ca2+ directly into the light-transducing lobe (the R-lobe) [6, 7, 15–17]. If GC is downstream, this form of excitation should be reduced by GC inhibitors. A similar strategy has been used previously to characterize the ordering of other steps in the cascade [15, 18, 28, 29].

We first tested whether a GC inhibitor affects the excitation produced by activating InsP3 receptors (Fig. 2). Cells were impaled with two microelectrodes. One microelectrode contained the poorly hydrolysable analog of InsP3, 3dInsP3 (1 mM) [30] and was inserted into the R-lobe. Previous work has shown that brief injections of InsP3 or its analogs excite ventral photoreceptors and that the latency of the response is lowest when the injection bolus is close to the light-transducing membrane in the R-lobe [6, 7]. The second electrode contained 50 mM GtetP and was positioned in the non-transducing A-lobe. Since multiple injections from this microelectrode were spread over time, GtetP could diffuse throughout the cell. Each injection of 3dInsP3 caused a transient repeatable depolarization similar to a light response, as previously reported for InsP3 and analogs [31–33]. Cells were then injected with sufficient GtetP to cause a substantial decrease in the light response (81% in Fig. 2). Injections of 3dInsP3 were interspersed between light flashes. It can be seen (Fig. 2) that the response to the InsP3 analog was also greatly reduced (81%). In five experiments, the average inhibition of the 3dInsP3 response was 77 ± 16%, comparable to the average inhibition of the light response (89 ± 7%). After cessation of GtetP injections, there was a slow recovery of both the response to 3dInsP3 and the response to light. We found that limiting the number of 3dInsP3 injections was important for maintaining a consistent response and so gave approximately ten injections each under control, GtetP inhibition, and recovery conditions. The 3dInsP3 used in these experiments was a hexasodium salt (6 mM Na+ in the injection electrode). Since Na+ in high concentration can inhibit the light response [34], control experiments were done to test whether comparable small Na+ injections might account for the observed effect on the light response. In five experiments, no effect of comparable injections of 5 mM Na+ alone (not shown) was seen. We conclude that the effects of GtetP are due to GtetP rather than Na+, and that its effects are downstream from activation of InsP3 receptors.

Guanosine 5'-tetraphosphate acts subsequent to InsP 3 -mediated Ca2+ release during excitation. Intracellular pressure injection from a microelectrode containing 25 mM GtetP decreased both the responses to a test flash and intracellular pressure injection of 1 mM 3dInsP3. Brackets and numbers match sets of five consecutive responses to light (1, 3, 5) or 3dInsP3 (2, 4, 6) averaged to produce the respective trace in the inset. 3dInsP3 injections were interspersed between test flashes during the periods indicated by brackets (2, 4, 6). GtetP was injected during the period indicated by a solid bar. Averaged responses are shown before (1, 2), at the end of drug application (3, 4), and late in recovery (5, 6).

Similar experiments were done to test whether GtetP inhibits responses to Ca2+ injections (Fig. 3). The response to Ca2+ injection was strongly inhibited (Fig. 3A), indicating that GC is downstream from Ca2+ elevation. The insets show averaged responses to Ca2+ injection (Fig. 3A) and light (Fig. 3B) before and after GtetP-induced inhibition. The time course of inhibition was similar for Ca2+ responses and light responses, however there was some quantitative difference: responses to light were decreased by 90% whereas responses to Ca2+ were decreased by 60% in this experiment. In six experiments, the average inhibition of the light response was 88 ± 7 % and the average inhibition of the response to Ca2+ injection was 60 ± 27 %. These small differences have not been analyzed further. One possibility is that the greater inhibition of the light response is indicative of a minor effect of GtetP on excitation upstream of InsP3-mediated Ca2+ release. In any case, our results clearly show that a major component of Ca2+-induced excitation can be blocked by a GC inhibitor.

GtetP acts subsequent to Ca2+-mediated excitation. (A) Injection from a microelectrode containing 25 mM GtetP caused a progressive decline in the response to injection from a second microelectrode of 1.8 mM Ca2+ solution buffered with 2 mM HEDTA. Data points are the average response with error bars (std. dev.) to ten consecutive Ca2+ injections before, after inhibition of the light response by GtetP, and late in recovery of the light response. GtetP was injected during the period indicated by the bar positioned between the graphs. Brackets and arrows match response amplitude to averaged voltage time course in the insets. (B) GtetP injection inhibited the response to test flashes in parallel to the decline in response to Ca2+.

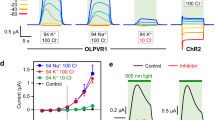

GC inhibitors act prior to the opening of cyclic nucleotide gated channels

In a final set of experiments, we tested the possibility the GC inhibitor might directly antagonize cyclic nucleotide-gated channels. We know of no precedent or other reason to suspect that GtetP would affect these channels, but it was nevertheless important to test directly for this possibility. This was done by examining whether GtetP affected the excitation produced by intracellular injection of the cGMP analog, Rp-8pCPT-cGMPS. We minimized intracellular accumulation of this membrane-permeant, high-affinity agonist by keeping the number of injections used for each measurement low (n < 10). In control experiments using these conditions (not shown) the response to Rp-8pCPT-cGMPS, the response to light, and membrane properties remained stable over long periods. Fig. 4 shows that the response to Rp-8pCPT-cGMPS was relatively unaffected by GtetP (10 to 30% decrease, N = 3), whereas the light response decreased enormously (90%). In two additional cells, the response to Rp-8pCPT-cGMPS injection appeared qualitatively unaffected by GtetP, but problems with clogging, a tendency of microelectrodes containing Rp-8pCPT-cGMPS, precluded quantitative analysis.

GtetP acts prior to opening of cyclic nucleotide-gated channels. (A) Injection from a microelectrode containing 25 mM GtetP was used to desensitize cells to a test flash by 90% (left panel). Data points are the average response with error bars (std. dev.) to seven consecutive test flashes. (B) The response to injection from a microelectrode containing 250 uM Rp-8pCPT-cGMPS (cGMP) in the same three cells was qualitatively unaffected by GtetP (left panel). Respective responses before (control) and after injection (GtetP) are matched by lines and symbols (+, *, and open circles). The voltage traces represent averaged responses from one cell (*) to light (left) and Rp-8pCPT-cGMPS (right) before (control) and after GtetP intracellular injections.

Discussion

There has been substantial previous work on the phototransduction cascade in Limulus, but the reactions involved in the late stages of the process have been unclear. In particular, there has been no information on enzymatic steps downstream from InsP3-mediated Ca2+ elevation that might couple this elevation to channel opening. Recently, it was shown that GC was required in the cascade [27], but its position in the cascade was not known. Here we have demonstrated that GC is downstream from Ca2+ and thus situated appropriately to mediate late stages of the cascade. As a result, a rather complete picture of the transduction cascade is now possible. In the paragraphs below, we provide an overview of this cascade and delineate areas where gaps remain.

In Limulus, excitation is initiated by conversion of rhodopsin to metarhodopsin by light (Fig. 5). The active state of metarhodopsin activates a G protein as evidenced by the fact that G protein inhibitors decrease the light-response, whereas G protein activators mimic the light response [31, 35, 36]. Metarhodopsin is inactivated in less than 150 ms [37]; while active about 10 G proteins are turned on [38]. The G protein involved has been identified as Gq in Limulus [39, 40]. In the next stage of the cascade, PLC is activated by Gq, resulting in the hydrolysis of phosphatidyl inositol-4,5-bisphosphate to produce InsP3 and diacyglycerol. PLC antagonists such as neomycin, spermine, and U-73122 decrease the response to light [41, 42] (see also [15]). Diacyglycerol may be important for excitation in Drosophila [10]; however in Limulus this is not likely to be the case [43]. InsP3 has been shown to meet all the requirements for acting as an intracellular second messenger necessary for excitation in Limulus: endogenous synthesis, increased concentration in response to light, and excitation through exogenous application [6, 7].

A model for Limulus excitation. The cascade is initiated by the isomerization of rhodopsin to metarhodopsin by light. Metarhodopsin catalyzes exchange of GTP for GDP on multiple G proteins (Gq). Gq-GTP binds and activates phospholipase C (PLC). This complex cleaves phosphatidyl inositol-4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) producing InsP3. InsP3 opens Ca2+ ion channels in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) leading to the release of Ca2+ into the cytosol. Ca2+ release activates GC. A rise in cGMP opens cyclic nucleotide-gated ion channels (CNCG) in the plasma membrane.

InsP3 produces a Ca2+ efflux from intracellular stores and can raise cytosolic Ca2+ upwards of 150 μ M [6, 7, 44, 45]. Excitation by light or InsP3 is blocked by the InsP3 receptor antagonist heparin [18, 29]. Direct measurements show that Ca2+ release is sufficiently fast to activate the light-dependent conductance [14, 45]. The InsP3 receptor is localized in the endoplasmic reticulum adjacent to the base of the rhodopsin-containing microvilli at the site of Ca2+ release [46]. Excitation can be mimicked by raising intracellular Ca2+ [15–17] and thwarted by Ca2+ buffers [16, 18]. Ca2+ elevation is thus necessary and sufficient for excitation.

Several lines of work indicate that the final step is the activation of cGMP-gated channels. Excitation can be induced by PDE inhibitors [25, 47] or by intracellular injection of cGMP [23, 24]. Most importantly, cGMP can directly activate channels when applied to inside-out excised membrane patches from the R-lobe [19]. These channels have properties similar to the light-activated channels in cell-attached patches on the R-lobe [48]. Most recently, a putative cyclic nucleotide-gated channel gene has been cloned from Limulus [22]. The mRNA for the channel is expressed in photoreceptors and the protein product was specifically localized in the R-lobe [21].

The work reported here shows that GC is appropriately positioned in the cascade to couple the light-induced Ca2+ elevation to the production of cGMP. In principle, the role of GC could be simply to constitutively produce cGMP; during light cGMP might be elevated due to a decrease in PDE activity. However, such a decrease in PDE activity during light exposure would probably enhance the response to injected cGMP relative to the dark-adapted response and certainly not decrease it, the observed effect [24]. These results thus strongly suggest that the GC is activated as a result of the light-induced elevation of Ca2+. Because there are few photoreceptors in the ventral eye, this preparation is not well-suited for biochemistry to the extent that experiments to test for the Ca2+ or light-dependence of GC are not practical. Therefore what is known in these photoreceptors about GC is based on its pharmacological profile. It has been concluded that the GC involved is not the soluble, NO-dependent form and therefore does not rely on Ca2+-dependent activation of nitric oxide synthase [27]. An important unresolved issue is how the enzyme might be regulated by Ca2+. Several precedents for Ca2+-dependent activation of this enzyme must be considered. For instance, in vertebrates Ca2+-dependent GC activating proteins (CD-GCAPs) and neurocalcin are known to activate rod GC [49, 50]. The concentration of Ca2+ required for this activity is well within the range achieved during Limulus phototransduction [44, 45]. In ciliates there is a form of GC that can be activated by Ca2+/calmodulin [51]. This raises the question of whether GC activation in Limulus might be mediated by calmodulin. The involvement of calmodulin in a critical step in the transduction cascade could be one reason for the high concentrations of calmodulin found in Limulus R-lobes [52].

The Limulus cascade is more complex than that of the vertebrate rod, but this increased complexity can be viewed in light of the remarkable performance characteristics of Limulus photoreceptors. These cells generate single photon responses in the nA range, three orders of magnitude larger than those of the rod. Furthermore, Limulus photoreceptors respond over nearly 4 orders of magnitude greater range of light intensities than rods [53, 54]. The Limulus cascade has eight stages compared to the five stages of the rod cascade. The larger number of stages may underlie the greater single-photon response and wider dynamic range seen in Limulus photoreceptors.

Conclusions

Although much has been determined about the phototransduction cascade in Limulus, the late steps occurring between InsP3-induced Ca2+ elevation and the opening of the cGMP-gated channels has been unclear. Previous work showed that guanylate cyclase was necessary for generation of the light-response, but did not identify where in the cascade it acted [27]. The major question answered in the present study is to determine whether GC is appropriately positioned at the end of the cascade where it could couple Ca2+ elevation to cGMP elevation. Our conclusion is that this is the case; the excitation produced by either InsP3 or Ca2+ injection can be greatly reduced by inhibiting GC (Figs. 2, 3). Importantly the GC inhibitor did not affect the excitation produced by injection of cGMP analog (Fig. 4); therefore channel function appears unaffected. Taken together with previous results, a picture of the enzymatic steps by which rhodopsin is coupled to channel activation in an invertebrate rhabdomeric photoreceptor can now be proposed (Fig. 5).

The simplest interpretation of the available data is that GC activation is the primary means by which the intracellular concentration of cGMP is increased during excitation in Limulus photoreceptors. This hypothesis can be tested by characterizing the specific guanylate cylase involved and the link between Ca2+ release and cyclase activation.

Methods

Electrophysiology

The dissection and techniques for electrophysiology have been described in detail elsewhere [16]. Cells were exposed to stimulus light with a maximal light intensity of 1.0 mW/cm2 which was attenuated by neutral density filters (attenuation = 10ND). Cells were perfused with artificial sea water (ASW) with the composition (in mM) 425 NaCl, 10 KCl, 10 CaCl2, 22 MgCl2, 26 MgSO4, and 15 Tris, adjusted to pH 7.8. Non-injecting intracellular microelectrodes contained 3 M KCl (15–25 mΩ resistance). Injection microelectrodes contained drugs as described in the text with (in mM) 150 KCl, 10 HEPES, 0.001% Triton X-100 [17] and had 7–15 mΩ resistance. The microelectrodes used to inject Ca2+ contained 1.8 mM Ca2+ buffered with HEDTA. This use of HEDTA has been described elsewhere and shown to not affect excitation or light adaptation [15]. GtetP, HEDTA, and IBMX were obtained from Sigma; InsP3 and 3dInsP3 from Calbiochem; Rp-8pCPT-cGMPS from Biolog.

Microscopy

The selection and observation of cells has been described in detail elsewhere [27]. Briefly, cells were observed under infrared illumination with Hofmann optics using a Cooke Corporation Sensicam. Cells were chosen on the basis of having a stable membrane potential and robust dark adapted and single photon light responses.

In some experiments the electrodes had to be placed into the light-sensitive R lobe of the cells. Under Hoffman optics, the R-lobe has a smooth appearance, contrasted with the granular appearance of the light-insensitive A-lobe. In these cases, the tip of the electrode was positioned at the border of the two lobes and advanced axially into the R-lobe.

Intracellular pressure injection

Injection electrodes were backfilled with at least 2 μL of solution and routinely recorded membrane potentials approximately 20 mV higher than 3 M KCl electrodes. Injections were observed on a monitor. The pulse duration and pressure were adjusted to maintain a constant bolus size. Injection electrodes became clogged on occasion, and the blockage was cleared using either a manually controlled high pressure pulse or brief (< 30 ms) oscillation train. If the cell's light or drug injection responses were affected by the clearing procedure, that experiment was not used.

Abbreviations

- A-lobe:

-

arhabdomeric lobe

- 3dInsP3:

-

3-deoxy-D-myo-inositol-1, 4,5-trisphosphate

- GC:

-

guanylate cyclase

- GtetP:

-

guanosine-5'-tetraphosphate

- HEDTA:

-

N-(2-hydroxyethyl)ethylenediaminetriacetic acid

- IBMX:

-

3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine

- InsP3:

-

D-myo-inositol-1, 4,5-trisphosphate

- PDE:

-

phosphodiesterase

- PLC:

-

phospholipase C

- R-lobe:

-

rhabdomeric lobe

- Rp-8pCPT-cGMPS:

-

Rp-8-(4-chlorophenylthio)guanosine-3' 5'-cyclic monophosphorothioate

References

Fain GL, Matthews HR, Cornwall MC, Koutalos Y: Adaptation in vertebrate photoreceptors. Physiol Rev. 2001, 81: 117-151.

Gomez M, Nasi E: Activation of light-dependent K+ channels in ciliary invertebrate photoreceptors involves cGMP but not the IP3/Ca2+ cascade. Neuron. 1995, 15: 607-618. 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90149-3.

Devary O, Heichal O, Blumenfeld A, Cassel D, Suss E, Barash S, Rubinstein CT, Minke B, Selinger Z: Coupling of photoexcited rhodopsin to inositol phospholipid hydrolysis in fly photoreceptors. Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.U.S.A. 1987, 84: 6939-6943.

Bloomquist BT, Shortridge RD, Schneuwly S, Perdew M, Montell C, Steller H, Rubin G, Pak WL: Isolation of a putative phospholipase C gene of Drosophila, norpA, and its role in phototransduction. Cell. 1988, 54: 723-733.

Inoue H, Yoshioka T, Hotta Y: Membrane-associated phospholipase C of Drosophila retina. J.Biochem.Tokyo. 1988, 103: 91-94.

Brown JE, Rubin LJ, Ghalayini AJ, Tarver AP, Irvine RF, Berridge MJ, Anderson RE: myo-inositol polyphosphate may be a messenger for visual excitation in Limulus photoreceptors. Nature. 1984, 311: 160-163.

Fein A, Payne R, Corson DW, Berridge MJ, Irvine RF: Photoreceptor excitation and adaptation by inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate. Nature. 1984, 311: 157-160.

Wood SF, Szuts EZ, Fein A: Inositol trisphosphate production in squid photoreceptors. Activation by light, aluminum fluoride, and guanine nucleotides. J Biol Chem. 1989, 264: 12970-12976.

Baer KM, Saibil HR: Light- and GTP-activated hydrolysis of phosphatidylinositol bisphosphate in squid photoreceptor membranes. J.Biol.Chem. 1988, 263: 17-20.

Chyb S, Raghu P, Hardie RC: Polyunsaturated fatty acids activate the Drosophila light-sensitive channels TRP and TRPL. Nature. 1999, 397: 255-259. 10.1038/16703.

Hardie RC, Martin F, Cochrane GW, Juusola M, Georgiev P, Raghu P: Molecular basis of amplification in Drosophila phototransduction: roles for G protein, phospholipase C, and diacylglycerol kinase. Neuron. 2002, 36: 689-701. 10.1016/S0896-6273(02)01048-6.

Hardie RC: Regulation of TRP channels via lipid second messengers. Annu Rev Physiol. 2003, 65: 735-759. 10.1146/annurev.physiol.65.092101.142505.

Lisman JE, Richard EA, Raghavachari S, Payne R: Simultaneous roles for Ca2+ in excitation and adaptation of Limulus ventral photoreceptors. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2002, 514: 507-538.

Payne R, Demas J: Timing of Ca2+ release from intracellular stores and the electrical response of Limulus ventral photoreceptors to dim flashes. J Gen Physiol. 2000, 115: 735-748. 10.1085/jgp.115.6.735.

Richard EA, Ghosh S, Lowenstein JM, Lisman JE: Ca2+/calmodulin-binding peptides block phototransduction in Limulus ventral photoreceptors: evidence for direct inhibition of phospholipase C. Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.USA. 1997, 94: 14095-14099. 10.1073/pnas.94.25.14095.

Shin J, Richard EA, Lisman JE: Ca2+ is an obligatory intermediate in the excitation cascade of Limulus photoreceptors. Neuron. 1993, 11: 845-855. 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90114-7.

Payne R, Corson DW, Fein A: Pressure injection of calcium both excites and adapts Limulus ventral photoreceptors. J.Gen.Physiol. 1986, 88: 107-126. 10.1085/jgp.88.1.107.

Frank TM, Fein A: The role of the inositol phosphate cascade in visual excitation of invertebrate microvillar photoreceptors. J.Gen.Physiol. 1991, 97: 697-723. 10.1085/jgp.97.4.697.

Bacigalupo J, Johnson EC, Vergara C, Lisman JE: Light-dependent channels from excised patches of Limulus ventral photoreceptors are opened by cGMP. Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.U.S.A. 1991, 88: 7938-7942.

Bacigalupo J, Lisman JE: Single-channel currents activated by light in Limulus ventral photoreceptors. Nature. 1983, 304: 268-270.

Chen FH, Baumann A, Payne R, Lisman JE: A cGMP-gated channel subunit in Limulus photoreceptors. Visual Neuroscience. 2001, 18: 517-526. 10.1017/S0952523801184026.

Chen FH, Ukhanova M, Thomas D, Afshar G, Tanda S, Battelle B-A, Payne R: Molecular cloning of a putative cyclic nucleotide-gated ion channel cDNA from Limulus polyphemus. J. Neurochem. 1999, 72: 461-471. 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1999.0720461.x.

Feng JJ, Frank TM, Fein A: Excitation of Limulus photoreceptors by hydrolysis-resistant analogs of cGMP and cAMP. Brain Res. 1991, 552: 291-294. 10.1016/0006-8993(91)90094-C.

Johnson EC, Robinson PR, Lisman JE: Cyclic GMP is involved in the excitation of invertebrate photoreceptors. Nature. 1986, 324: 468-470.

Brown JE, Kaupp UB, Malbon CC: 3',5'-cyclic adenosine monophosphate and adenylate cyclase in phototransduction by Limulus ventral photoreceptors. Journal of Physiology. 1984, 353: 523-539.

Dorlöchter M, de Vente J: Cyclic GMP in lateral eyes of the horseshoe crab Limulus. Vision Res. 2000, 40: 3677-3684. 10.1016/S0042-6989(00)00198-X.

Garger A, Richard EA, Lisman JE: Inhibitors of guanylate cyclase inhibit phototransduction in Limulus photoreceptors. Visual Neuroscience. 2001, 18: 625-632. 10.1017/S0952523801184129.

Dabdoub A, Payne R: Protein kinase C activators inhibit the visual cascade in Limulus ventral photoreceptors at an early stage. J Neurosci. 1999, 19: 10262-10269.

Faddis MN, Brown JE: Flash photolysis of caged compounds in Limulus ventral photoreceptors. J.Gen.Physiol. 1992, 100: 547-570. 10.1085/jgp.100.3.547.

Kozikowski AP, Ognyanov VI, Fauq AH, Nahorski SR, Wilcox RA: Synthesis of 1D-3-deoxy-, 1D-2,3-dideoxy-, and 1D-2,3,6-trideoxy-myo-inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate from quebrachitol, their binding affinities, and calcium release activity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1993, 115: 4429-4434.

Fein A: Blockade of visual excitation and adaptation in Limulus photoreceptor by GDP-beta-S. Science. 1986, 232: 1543-1545.

Payne R, Potter BV: Injection of inositol trisphosphorothioate into Limulus ventral photoreceptors causes oscillations of free cytosolic calcium. J.Gen.Physiol. 1991, 97: 1165-1186. 10.1085/jgp.97.6.1165.

Levitan I, Payne R, Potter BV, Hillman P: Facilitation of the responses to injections of inositol 1,4,5- trisphosphate analogs in Limulus ventral photoreceptors. Biophysical Journal. 1994, 67: 1161-1172.

Lisman JE, Brown JE: The effects of intracellular iontophoretic injection of calcium and sodium ions on the light response of Limulus ventral photoreceptors. J.Gen.Physiol. 1972, 59: 701-719. 10.1085/jgp.59.6.701.

Fein A, Corson DW: Excitation of Limulus photoreceptors by vanadate and by a hydrolysis-resistant analog of guanosine triphosphate. Science. 1981, 212: 555-557.

Fein A, Corson DW: Both photons and fluoride ions excite Limulus ventral photoreceptors. Science. 1979, 204: 77-79.

Richard EA, Lisman JE: Rhodopsin inactivation is a modulated process in Limulus photoreceptors. Nature. 1992, 356: 336-338. 10.1038/356336a0.

Kirkwood A, Weiner D, Lisman JE: An estimate of the number of G regulator proteins activated per excited rhodopsin in living Limulus ventral photoreceptors. Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.U.S.A. 1989, 86: 3872-3876.

Dorlöchter M, Klemeit M, Stieve H: Immunological demonstration of Gq-protein in Limulus photoreceptors. Vis.Neurosci. 1997, 14: 287-292.

Munger SD, Schremser-Berlin J-L, Brink CM, Battelle B-A: Molecular and immunological characterization of a Gq protein from ventral and lateral eye of the horseshoe crab Limulus polyphemus. Invert. Neurosci. 1996, 2: 175-182.

Nagy K, Contzen K: Inhibition of phospholipase C by U-73122 blocks one component of the receptor current in Limulus photoreceptor. Vis.Neurosci. 1997, 14: 995-998.

Faddis MN, Brown JE: Intracellular injection of heparin and polyamines. Effects on phototransduction in Limulus ventral photoreceptors. J.Gen.Physiol. 1993, 101: 909-931. 10.1085/jgp.101.6.909.

Fein A, Cavar S: Divergent mechanisms for phototransduction of invertebrate microvillar photoreceptors. Vis Neurosci. 2000, 17: 911-917. 10.1017/S0952523800176102.

Ukhanov KY, Flores TM, Hsiao HS, Mohapatra P, Pitts CH, Payne R: Measurement of cytosolic Ca2+ concentration in Limulus ventral photoreceptors using fluorescent dyes. J.Gen.Physiol. 1995, 105: 95-116. 10.1085/jgp.105.1.95.

Ukhanov K, Payne R: Light activated calcium release in Limulus ventral photoreceptors as revealed by laser confocal microscopy. Cell Calcium. 1995, 18: 301-313. 10.1016/0143-4160(95)90026-8.

Ukhanov K, Ukhanova M, Taylor CW, Payne R: Putative inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor localized to endoplasmic reticulum in Limulus photoreceptors. Neuroscience. 1998, 86: 23-28. 10.1016/S0306-4522(98)00164-X.

Johnson EC, O'Day PM: Inhibitors of cyclic-GMP phosphodiesterase alter excitation of Limulus ventral photoreceptors in Ca2+-dependent fashion. J.Neurosci. 1995, 15: 6586-6591.

Bacigalupo J, Chinn K, Lisman JE: Ion channels activated by light in Limulus ventral photoreceptors. J.Gen.Physiol. 1986, 87: 73-89. 10.1085/jgp.87.1.73.

Margulis A, Pozdnyakov N, Sitaramayya A: Activation of bovine photoreceptor guanylate cyclase by S100 proteins. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1996, 218: 243-247. 10.1006/bbrc.1996.0043.

Kumar VD, Vijay-Kumar S, Krishnan A, Duda T, Sharma RK: A second calcium regulator of rod outer segment membrane guanylate cyclase, ROS-GC1: neurocalcin. Biochemistry. 1999, 38: 12614-12620. 10.1021/bi990851n.

Schultz JE, Klumpp S: Lanthanum dissociates calmodulin from the guanylate cyclase of the excitable ciliary membrane from Paramecium. FEMS Microbiol.Letts. 1982, 13: 303-306. 10.1016/0378-1097(82)90116-1.

Battelle BA, Dabdoub A, Malone MA, Andrews AW, Cacciatore C, Calman BG, Smith WC, Payne R: Immunocytochemical localization of opsin, visual arrestin, myosin III, and calmodulin in Limulus lateral eye retinular cells and ventral photoreceptors. J Comp Neurol. 2001, 435: 211-225. 10.1002/cne.1203.

Lisman JE, Brown JE: Light induced changes of sensitivity in Limulus ventral photoreceptors. J.Gen.Physiol. 1975, 66: 473-488. 10.1085/jgp.66.4.473.

Brown JE, Coles JA: Saturation of the response to light in Limulus ventral photoreceptors. Journal of Physiology. 1979, 296: 373-392.

Acknowledgements

This grant was supported by NIH EYO1496 and support from the W. M. Keck Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Authors' contributions

AG carried out the electrophysiology studies and data analysis. ER designed the study, and participated in data analysis and drafting of the manuscript. JL conceived of the study, contributed to the experimental design and coordination, and participated in the drafting of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Garger, A.V., Richard, E.A. & Lisman, J.E. The excitation cascade of Limulus ventral photoreceptors: guanylate cyclase as the link between InsP3-mediated Ca2+release and the opening of cGMP-gated channels. BMC Neurosci 5, 7 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2202-5-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2202-5-7