Abstract

Background

Excitotoxic neuronal injury by action of the glutamate receptors of the N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) subtype have been implicated in the pathogenesis of brain damage as a consequence of bacterial meningitis. The most potent and selective blocker of NMDA receptors containing the NR2B subunit is (R,S)-alpha-(4-hydroxyphenyl)-beta-methyl-4-(phenylmethyl)-1-piperid inepropanol (RO 25-6981). Here we evaluated the effect of RO 25-6981 on hippocampal neuronal apoptosis in an infant rat model of meningitis due to Streptococcus pneumoniae. Animals were randomized for treatment with RO 25-6981 at a dosage of either 0.375 mg (15 mg/kg; n = 28) or 3.75 mg (150 mg/kg; n = 15) every 3 h or an equal volume of sterile saline (250 μl; n = 40) starting at 12 h after infection. Eighteen hours after infection, animals were assessed clinically and seizures were observed for a period of 2 h. At 24 h after infection animals were sacrificed and brains were examined for apoptotic injury to the dentate granule cell layer of the hippocampus.

Results

Treatment with RO 25-6981 had no effect on clinical scores, but the incidence of seizures was reduced (P < 0.05 for all RO 25-6981 treated animals combined). The extent of apoptosis was not affected by low or high doses of RO 25-6981. Number of apoptotic cells (median [range]) was 12.76 [3.16–25.3] in animals treated with low dose RO 25-6981 (control animals 13.8 [2.60–31.8]; (P = NS) and 9.8 [1.7–27.3] (controls: 10.5 [2.4–21.75]) in animals treated with high dose RO 25-6981 (P = NS).

Conclusions

Treatment with a highly selective blocker of NMDA receptors containing the NR2B subunit failed to protect hippocampal neurons from injury in this model of pneumococcal meningitis, while it had some beneficial effect on the incidence of seizures.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Bacterial meningitis is the most common serious infection of the central nervous system and, despite the use of highly effective antibiotics, is fatal in 5–25% of patients and causes neurologic sequelae in up to 30% of the survivors [1]. Two forms of neuronal injury have been identified. The first form consists of necrotic injury in the cortex and is reduced by therapies that prevent the development of ischemia [2]. The second form consists of apoptosis in the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus. It may be responsible for learning and memory deficits observed after meningitis [2].

Neuronal damage during meningitis may be caused by excitatory amino acids (EAA) [3]. The NMDA subtype of EAA receptors is believed to be responsible for excitotoxic cell death associated with neuronal disorders and injury [4, 5]. NMDA receptors are composed of an association of subunits that belong to two families: a single gene product (NR1) with eight splice variants and four different NR2 subunits (NR2A, B, C, D) produced by a different gene [6]. Within the brain, the NR1, NR2A and NR2B subunits are more prominent in cortical areas and the hippocampus than in white matter and cerebellum [7]. The NR2B subunits are expressed at highest levels in the hippocampus, cerebral cortex and olfactory bulb [8]. During early postnatal development, NR2B subunits may have a more dominant role than NR2A in modulating NMDA receptors throughout the CNS [9]. Recently, NR2B-selective NMDA antagonists have been developed that are protective in focal cerebral ischemia [8, 10]. RO 25-6981 is a noncompetitive, highly selective, activity-dependent blocker of NMDA receptors that contain the NR2B subunit [11]. The aim of the present study was to evaluate the effect of the NR2B-selective NMDA antagonist RO 25-6981 on hippocampal injury and seizures in an infant rat model of meningitis due to Streptococcus pneumoniae.

Methods

Infant rat model of bacterial meningitis

The animal studies were approved by the Animal Care and Experimentation Committee of the Canton of Bern, Switzerland and followed National Institutes of Health guidelines for the performance of animal experiments.

Nursing Sprague-Dawley rat pups with their dam were purchased (RCC Biotechnology & Animal Breeding, Füllinsdorf, Switzerland) and pups were infected on postnatal day 11. A clinical strain of Streptococcus pneumoniae (type 3) was used. Ten μl of a suspension of the organism in normal saline produced from a log-phase culture was directly injected into the cisterna magna [2, 12]. The inoculum size was ~log10 6.3 colony forming units/ml. Eighteen hours after infection, all animals were weighed and assessed clinically. Clinical severity of disease was scored in each animal and was graded as follows: 1 = coma; 2 = does not turn upright; 3 = turns upright within 30 s; 4 = minimal ambulatory activity; 5 = normal. Seizures as defined by tonic convulsions for >15 sec were observed for a period of two hours (i.e. from 18 to 20 h after infection).

To document meningitis, 10–30 μl of CSF was obtained at 18 h after infection by puncture of the cisterna magna and was cultured quantitatively on blood-agar plates and incubated for 24 h at 37°C with 5 % CO2. All animals were subsequently treated with antibiotics (ceftriaxone, 100 mg/kg subcutaneously once; Roche Pharma, Basel, Switzerland) as untreated animals die from the disease within 20–22 h after infection.

Animals were sacrificed with an overdose of pentobarbital (100 mg/kg intraperitoneally) at 24 h after infection or when they became terminally ill (cyanotic, severe dyspnea, protracted seizures).

Treatment regimens

Animals were randomized for treatment with RO 25-6981 (kindly provided by Dr. G. Fischer, Roche Pharma, Basel, Switzerland) or an equal volume of sterile saline (250 μl; n = 40) starting at 12 h after infection. Animals treated with RO 25-6981 received either 0.375 mg (15 mg/kg = low dose; n = 28) or 3.75 mg = (150 mg/kg = high dose; n = 15) subcutaneously every 3 h.

Histomorphometry

Immediately after sacrifice, animals were perfused via the left cardiac ventricle with 15 ml of 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate buffered saline (pH 7.4). Brains were cut at 45-μm intervals on a cryostat (Cryocut 1800; Leica Instruments, Nussloch, Germany) to obtain 12 coronal section. Only animals that survived > 18 h were included for the analysis of neuronal damage, since previous studies had shown that apoptosis is not reliably detected prior to 18 h after infection. Sections were stained with cresyl violet. For quantitative evaluation, coronal sections were examined for injury to the dentate granule cell layer of the hippocampus. Cells with morphologic changes compatible with apoptosis (condensed or fragmented nuclei, Figure 1) were counted in 3 visual fields (×400) in each of the four blades of the dentate gyrus. An averaged score per animal was calculated from all sections evaluated. All histopathologic evaluations were performed by an investigator blinded to the clinical, microbiological and treatment data of animals.

Hippocampal histopathology of infant rats with pneumococcal meningitis 24 hours after infection. Section of the dentate gyrus at ×100 magnification. Arrowheads point to apoptotic neurons in the granule cell layer; bar, 100 μm. Insert depicts apoptotic cells at ×450 magnification with characteristic condensed and fragmented nuclei; bar, 25 μm. (Nissl stain)

Statistics

Bacterial titers in the CSF were compared with the unpaired t-test. Incidence of seizures and spontaneous death were compared using Fisher's exact test. The score of hippocampal apoptosis was analyzed with the Mann-Whitney test. The clinical activity score and weight at 18 h were compared with one way ANOVA and the Newman-Keuls post-hoc test for multiple comparison. Probabilities ≤ 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Clinical outcome

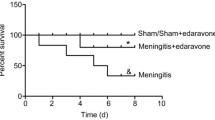

Eighteen hours after infection, all infected animals had fully developed meningitis, as evidenced by lethargy or obtundation and by positive bacterial CSF titers. Treatment of animals with RO 25-6981, beginning at 12 h after infection, had no influence on bacterial titers in CSF or clinical score (Table 1). Spontaneous death occurred more frequently (p < 0.02) in animals which received the higher dose of RO 25-6981 compared to animals treated with the lower dose. Mortality was not significantly different for all treated animals combined vs. saline controls and for the two treatment groups alone vs. their respective controls (Table 1). Between 18 and 20 h after infection, seizures occurred in 3/28 of animals treated with the low dose of RO 25-6981, compared to 7/28 of the corresponding saline controls. Similarly, animals treated with ten times higher dose of RO 25-6981 had a frequency of seizures of 1/15 compared to 4/12 in the corresponding controls. The differences in the incidence of seizures did not reach statistical significance when treatment groups were compared with their respective controls alone. However, comparison of seizure frequency of all treated animals (4/43) with that of the saline controls (11/40) revealed a significant (P < 0.05) reduction in animals treated with RO 25-6981.

Hippocampal injury

In all groups, there was apoptosis in the dentate gyrus (Figure 1). In the group of animals treated with the low doses of RO 25-6981, the median and [range] number of apoptotic cells was 12.76 [3.16–25.3], compared to 13.8 [2.60–31.8] in saline treated control animals (P = NS). Similarly, treatment with the higher doses of RO 25-6981 did not significantly reduce the number of apoptotic cells in comparison to saline treated controls (9.8 [1.7–27.3] vs 10.5 [2.4–21.75]; P = NS).

Discussion

Several observations led to the exploration of the role of EAA in causing seizures and apoptotic neuronal injury in the hippocampus. First, glutamate concentrations are markedly increased in the brain extracellular fluid and in the CSF during bacterial meningitis [3, 13]. Of note, the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus is in close vicinity of ventricular space. It is therefore conceivable that glutamate may diffuse into this brain structure from the CSF in the ventricular space, when concentrations of the EAA are increased during meningitis [14]. This is important in the current context, since direct ischemia, with subsequent local release of glutamate within the hippocampal tissue does not appear to be the primary mechanism of injury to this structure during meningitis [2]. Secondly, at certain concentrations, glutamate tends to induce apoptosis rather than necrosis in the brain [15–17]. This is of interest in the context of the hypothesis that glutamate may diffuse into the parenchyma of the hippocampus from the CSF in the ventricular system. This could lead to relatively moderate increases of extracellular glutamate concentrations, particularly if the local astrocytes maintain some glutamate scavenging functions, thus favoring apoptosis over necrosis. Finally, our earlier results in a model of group B streptococcal meningitis have indicated that the non-specific inhibitor of glutamate receptors, kynurenic acid, was protective in the hippocampus [18].

The failure of the drug to protect from structural damage despite its functional benefits (seizures) does not appear to result from insufficient dosing. We have used doses found previously to be effective in rats [19], and a 10-fold increased dose, which was high enough to show signs of toxicity (increased mortality) was not more effective than the standard dose. Furthermore, RO 25-6981 suppressed seizures, indicating that the drug did indeed penetrate into the brain in therapeutically relevant concentrations. Antagonists of NMDA receptors are powerful anticonvulsants in many animal models of epilepsy [20]. One obvious reason for the lack of neuroprotection may be that NMDA receptor stimulation by EAA is not causing apoptotic injury to the dentate gyrus. Our study with kynurenic acid, while showing some protection in the dentate gyrus, did not specifically examine whether it was the apoptotic form of injury that was prevented [18]. Another explanation may lie in the fact that beginning at about postnatal day 12, the levels of NR2B protein decline rapidly and reach undetectable levels by 22 days after birth [9]. The animals in our study were 12 days old at the time of therapy, an age where the NR2B subunit can still be documented immunocytochemically [21]. Nevertheless, it is conceivable that the number of functional NDMA receptors containing this subunit is already sufficiently reduced to make its blockade less effective. Alternatively, while the NR2B NDMA receptor may still be sufficiently functional, it may not be directly involved in causing the apoptotic form of neuronal injury observed in bacterial meningitis. Given the effect of the drug on seizures, we believe that the latter explanation is more likely.

Conclusions

In the present study, the NR2B selective NMDA antagonist RO 25-6981 prevented the occurrence of seizures during acute bacterial meningitis, but failed to demonstrate a protective effect on neuronal apoptotic injury in the hippocampal dentate gyrus. The potential of RO 25-6981 to serve as neuroprotective agent in bacterial meningitis is put into question by this study, while the drug may be of value as an antiepileptic compound.

References

Grimwood K, Nolan TM, Bond L, Anderson VA, Catroppa C, Keir EH: Risk factors for adverse outcomes of bacterial meningitis. J Paediatr Child Health. 1996, 32: 457-62.

Pfister L-A, Tureen JH, Shaw S, Christen S, Ferriero DM, Täuber MG, Leib SL: Endothelin inhibition improves cerebral blood flow and is neuroprotective in pneumococcal meningitis. Ann Neurol. 2000, 47: 329-35. 10.1002/1531-8249(200003)47:3<329::AID-ANA8>3.3.CO;2-I.

Guerra-Romero L, Tureen JH, Fournier MA, Makrides V, Tauber MG: Amino acids in cerebrospinal and brain interstitial fluid in experimental pneumococcal meningitis. Pediatr Res. 1993, 33: 510-3.

Di Loreto S, Balestrino M, Pellegrini P, Berghella AM, Del Beato T, Di Marco F, Adorno D: Blockade of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor prevents hypoxic neuronal death and cytokine release. Neuroimmunomodulation. 1997, 4: 195-9.

Lafon-Cazal M, Pietri S, Culcasi M, Bockaert J: NMDA-dependent superoxide production and neurotoxicity. Nature. 1993, 364: 535-7. 10.1038/364535a0.

Mutel V, Buchy D, Klingelschmidt A, Messer J, Bleuel Z, Kemp JA, Richards JG: In vitro binding properties in rat brain of [3H]Ro 25-6981, a potent and selective antagonist of NMDA receptors containing NR2B subunits. J Neurochem. 1998, 70: 2147-55.

Kim WT, Kuo MF, Mishra OP, Delivoria-Papadopoulos M: Distribution and expression of the subunits of N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors; NR1, NR2A and NR2B in hypoxic newborn piglet brains. Brain Res. 1998, 799: 49-54. 10.1016/S0006-8993(98)00464-8.

Boyce S, Wyatt A, Webb JK, O'Donnell R, Mason G, Rigby M, Sirinathsinghji D, Hill RG, Rupniak NM: Selective NMDA NR2B antagonists induce antinociception without motor dysfunction: correlation with restricted localisation of NR2B subunit in dorsal horn. Neuropharmacology. 1999, 38: 611-23. 10.1016/S0028-3908(98)00218-4.

Wang YH, Bosy TZ, Yasuda RP, Grayson DR, Vicini S, Pizzorusso T, Wolfe BB: Characterization of NMDA receptor subunit-specific antibodies: distribution of NR2A and NR2B receptor subunits in rat brain and ontogenic profile in the cerebellum. J Neurochem. 1995, 65: 176-83.

Reyes M, Reyes A, Opitz T, Kapin MA, Stanton PK: Eliprodil, a non-competitive, NR2B-selective NMDA antagonist, protects pyramidal neurons in hippocampal slices from hypoxic/ischemic damage. Brain Res. 1998, 782: 212-8. 10.1016/S0006-8993(97)01280-8.

Fischer G, Mutel V, Trube G, Malherbe P, Kew JN, Mohacsi E, Heitz MP, Kemp JA: Ro 25-6981, a highly potent and selective blocker of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors containing the NR2B subunit. Characterization in vitro. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1997, 283: 1285-92.

Leib SL, Leppert D, Clements J, Täuber MG: Matrix metalloproteinases contribute to brain damage in experimental pneumococcal meningitis. Infect Immun. 2000, 68: 615-20. 10.1128/IAI.68.2.615-620.2000.

Spranger M, Schwab S, Krempien S, Winterholler M, Steiner T, Hacke W: Excess glutamate levels in the cerebrospinal fluid predict clinical outcome of bacterial meningitis. Arch Neurol. 1996, 53: 992-6.

Leib SL, Täuber MG: Strategies for prevention of brain damage resulting from bacterial meningitis. Schweiz Med Wochenschr. 2000, 130: 928-35.

Tenneti L, D'Emilia DM, Troy CM, Lipton SA: Role of caspases in N-methyl-D-aspartate-induced apoptosis in cerebrocortical neurons. J Neurochem. 1998, 71: 946-59.

Du Y, Bales KR, Dodel RC, Hamilton-Byrd E, Horn JW, Czilli DL, Simmons LK, Ni B, Paul SM: Activation of a caspase 3-related cysteine protease is required for glutamate-mediated apoptosis of cultured cerebellar granule neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997, 94: 11657-62. 10.1073/pnas.94.21.11657.

Tumani H, Smirnov A, Barchfeld S, Olgemoller U, Maier K, Lange P, Bruck W, Nau R: Inhibition of glutamine synthetase in rabbit pneumococcal meningitis is associated with neuronal apoptosis in the dentate gyrus. Glia. 2000, 30: 11-8. 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1136(200003)30:1<11::AID-GLIA2>3.0.CO;2-E.

Leib SL, Kim YS, Ferriero DM, Täuber MG: Neuroprotective effect of excitatory amino acid antagonist kynurenic acid in experimental bacterial meningitis. J Infect Dis. 1996, 173: 166-71.

Lanis A, Schmidt WJ: NMDA receptor antagonists do not block the development of sensitization of catalepsy, but make its expression state-dependent. Behav Pharmacol. 2001, 12: 143-9.

Chapman AG: Glutamate receptors in epilepsy. Prog Brain Res. 1998, 116: 371-83.

Takai H, Katayama K, Uetsuka K, Nakayama H, Doi K: Distribution of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors (NMDARs) in the developing rat brain. Exp Mol Pathol. 2003, 75: 89-94. 10.1016/S0014-4800(03)00030-3.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Philipp Joss for the technical support. This work was supported by grants from the Swiss National Science Foundation (32-61654.00 and 632-66057.01), and by the NIH (NS-35902).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Authors' contributions

AK participated in carrying out the animal studies, in the histopathological evaluation and in drafting the manuscript. RR participated in coordinating the animal experiments and in carrying out and evaluating the animal studies. MGT participated in the design of the project and in writing of the manuscript. SLL participated in the design of the project, in coordinating the project and in writing of the manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Kolarova, A., Ringer, R., Täuber, M.G. et al. Blockade of NMDA receptor subtype NR2B prevents seizures but not apoptosis of dentate gyrus neurons in bacterial meningitis in infant rats. BMC Neurosci 4, 21 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2202-4-21

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2202-4-21