Abstract

Background

The human inferior frontal junction area (IFJ) is critically involved in three main component processes of cognitive control (working memory, task switching and inhibitory control). As it overlaps with several areas in established anatomical labeling schemes, it is considered to be underreported as a functionally distinct location in the neuroimaging literature. While recent studies explicitly focused on the IFJ's anatomical organization and functional role as a single brain area, it is usually not explicitly denominated in studies on cognitive networks. However based on few analyses in small datasets constrained by specific a priori assumptions on its functional specialization, the IFJ has been postulated to be part of a cognitive control network. Goal of this meta-analysis was to establish the IFJ’s connectivity profile on a high formal level of evidence by aggregating published implicit knowledge about its co-activations. We applied meta-analytical connectivity modeling (MACM) based on the activation likelihood estimation (ALE) method without specific assumptions regarding functional specialization on 180 (reporting left IFJ activity) and 131 (right IFJ) published functional neuroimaging experiments derived from the BrainMap database. This method is based on coordinates in stereotaxic space, not on anatomical descriptors.

Results

The IFJ is significantly co-activated with areas in the dorsolateral and ventrolateral prefrontal cortex, anterior insula, medial frontal gyrus / pre-SMA, posterior parietal cortex, occipitotemporal junction / cerebellum, thalamus and putamen as well as language and motor areas. Results are corroborated by an independent resting-state fMRI analysis.

Conclusions

These results support the assumption that the IFJ is part of a previously described cognitive control network. They also highlight the involvement of subcortical structures in this system. A direct line is drawn from works on the functional significance of brain activity located at the IFJ and its anatomical definition to published results related to distributed cognitive brain systems. The IFJ is therefore introduced as a convenient starting point to investigate the cognitive control network in further studies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The human inferior frontal junction area (IFJ) located at the junction of the inferior frontal sulcus and the inferior precentral sulcus had been largely neglected as a distinct region involved in cognitive control processes. Yet recent work explicitly addressing this brain area has attributed a major role to the IFJ related to three main component processes (task switching, inhibitory control and working memory) [1–8]. In an FDG-PET study hypometabolism in the IFJ was associated with cognitive decline in early dementia suggesting a potential clinical relevance of IFJ functioning [5]. An involvement of the IFJ in a network associated with cognitive control has been suggested mainly based on a single highly hypothesis-driven combined task- and resting-state-fMRI study. This network also involves the anterior cingulate cortex/pre-supplementary motor area (ACC/pre-SMA), dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC), anterior insular cortex, dorsal pre-motor cortex, and posterior parietal cortex (PPC) [9]. Though there is a larger body of neuroimaging literature on fronto-parietal networks associated with cognitive functions (e.g. [10, 11], see Discussion), to our knowledge there is no further work explicitly denominating the IFJ as one of their constituents.

Peak coordinates from published human functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) studies accumulated in the BrainMap database have previously been integrated in order to delineate the functional connectivity of designated brain regions based on their co-activation profiles using the activation likelihood estimation (ALE) method [12–14]: Activation coordinates reported together with peaks within a defined seed region are retrieved from the database. Gaussian probability distributions are then modeled centered at these coordinates based on spatial variability estimates. Then these distributed activations are analyzed for where they converge in random-effects-analyses, weighted by the number of subjects in the studies included [12, 15]. Such Metanalytic Connectivity Modelling (MACM) has been validated against non-human primate anatomical connectivity [16] and human resting-state functional connectivity (rsFC) modeling [13] showing substantial overlap. There is additional evidence that large BrainMap datasets contain information similar to rsFC from calculations based on independent component analyses (ICA) [10]. A similar coactivation approach has been used to build a voxel-wise functional connectivity map of the human brain using the BrainMap database in June 2006 with 825 articles available then [17].

Goal of this meta-analysis was to aggregate implicit knowledge by means of coordinate representation (independent from anatomical descriptors) to characterize the functional connectivity profile of the IFJ on the basis of more than a decade of neuroimaging studies. These included a variety of studies investigating cognitive control yet there were no a priori constraints regarding the functional specialization of the IFJ. Do these aggregated data support the hypothesis of the involvement in the cognitive control network as proposed by Cole et al. [9]? Are there additional regions associated with IFJ activations not recognized by many individual studies but significantly involved across a large number of fMRI sessions? How do potential findings relate to earlier work based on different methodology (human structural connectivity based on diffusion MRI, human resting-state and task-based fMRI and animal studies) regarding the role of the IFJ in the functional and structural organization of the human brain? To what extent is the IFJ-connectivity lateralized? Can meta-analytic results be confirmed by resting-state fMRI [18] using an analogous seed-definition?

Methods

Activation likelihood estimation meta-analysis

IFJ coordinates were adapted from a review article [1] aggregating peak locations from different functional imaging studies, and task-based meta-analyses showing IFJ-activations and reporting an approximation of the IFJ location as a functionally defined brain area. Instead, relying on an atlas-based anatomical definition would have been difficult as the IFJ has been reported to overlap with different cytoarchitectonically defined areas (mainly Brodmann areas 6, 9 and 44). Cuboidal seeds were defined by adding spatial extent along the x-axis to their two-dimensional definition: left IFJ from (-52, 1, 27) to (-42, 10, 40) and right IFJ from (42, 1, 27) to (52, 10, 40) with (x, y, z) representing coordinates in the Talairach coordinate system [19]. All coordinates reported in the meta-analysis refer to Talairach space, which is the space used by the BrainMap database.

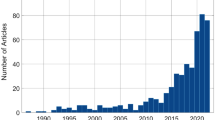

Data were retrieved from the BrainMap database using Sleuth (Version 1.2) [20, 21] on 30 June 2011 containing results of 2,114 articles in total at that time [22]. Whole-brain activation coordinates from those fMRI sessions which revealed IFJ activations within the seeds were extracted for the left and right IFJ separately. The query was additionally restricted to right-handed healthy subjects and the context of normal mapping according to the studies’ BrainMap records.

Regarding the left IFJ we identified 180 experiments/contrasts comprising 2,274 subjects in 139 articles (from 730 single experiments in 2,434 participants in these studies in total). Consequently 2,764 of 8,301 locations reported in these papers were included in further analyses. For the right IFJ 131 experiments in 1,767 subjects reported in 111 articles (from 574 experiments in 1962 participants in these studies) matched these criteria. Thus 2,336 of 6,922 locations shown in these papers were included. A complete list of these articles is provided in the supplementary online material.

The ALE random effects meta-analysis was conducted using the revised algorithm by Eickhoff et. al. in GingerALE (Version 2.0) [15, 23]. After excluding locations potentially outside the brain by masking coordinates using the conservative standard mask in GingerALE (dimensions 80 x 96 x 70 mm) 2,727 (left IFJ) and 2,293 activation foci (right IFJ) remained. Study specific smoothing using a Gaussian kernel was applied (left IFJ: median full width at half maximum = 9.66, range 8.71 to 11.37; right IFJ: median full with at half maximum = 9.66, range 8.67 to 11.37). For resulting co-activations with the IFJ a threshold of p = 0.001 corrected for multiple comparisons using false-discovery rate (FDR) was applied at voxel-level. Anatomical labels are automatically assigned in GingerALE.

Visualizations were created using Mango (Version 2.3.2) [24] and an anatomical template in Talairach space [25].

Resting-state functional connectivity analysis

In order to confirm our meta-analytic results using a different approach to functional connectivity, we additionally performed a seed-based analysis of intrinsic fluctuations in a presumably independent sample.

We therefore retrieved an anonymized resting-state fMRI dataset comprising 198 individuals (123 females and 75 males aged 18 to 30 years, mean age: 21.03 ± 2.31 years). For each participant 119 volumes of 47 slices had been acquired with TR = 3 s using a 3 Tesla MRI-scanner (resulting total acquisition time 5 min 57 s). The dataset is publicly available from the 1000 Functional Connectomes Project (FCP) [26] and data were provided by R. L. Buckner, Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Cambridge, MA. Acquisition and submission of the data was approved by the contributor’s ethics committee. The institutional review boards of NYU Langone Medical Center and New Jersey Medical School approved the receipt and dissemination of the data through the FCP [27].

As a prerequisite for further analyses, center coordinates of the meta-analytic seed as described above were converted to MNI space using the Lancaster transform [28] as implemented in GingerALE [29]: ±52, 11, 31 (seeds 1 and 2). In order to exclude a substantial biasing influence of our seed coordinate selection strategy we also conducted an analogous analysis using more medial mean coordinates from a study on interindividual variability of the IFJ’s location [2]: -41, 7, 31 and 47, 7, 29 (seeds 3 and 4). Spherical ROIs with a radius of 15 mm in MNI spaced were constructed and used as seeds in further analyses.

There is a range of widely accepted preprocessing steps in analyses of rs-fc data [30]. The following raw data modification steps were guided by these principles: The first 6 EPI-volumes were discarded in order to allow for T1-equilibration. Using SPM8 [31] based on MATLAB (R2010a, ver. 7.10.0.499, The MathWorks Inc., Natick, MA) images were motion corrected, normalized to a template in MNI space, resampled to a voxel-size of 2 x 2 x 2 mm3 and smoothed using a Gaussian kernel (FWHM = 6 mm).

Resulting images were subjected to a conventional seed-based functional connectivity analysis based on Pearson linear correlation using REST (version 1.7) [32, 33], a MATLAB Toolbox: A temporal band-pass filter (0.01 to 0.08 Hz) was applied to restrict the analysis to the typical frequency-band of spontaneous signal fluctuations and linear trends were removed. A template was used for masking voxels typically outside the brain. Signal time courses obtained from the ventricles and white matter as operationalized by corresponding templates, global signal and motion correction parameters were included as covariates in the partial correlation model. Correlation coefficients of signal co-fluctuations with the left IFJ were calculated for every remaining voxel and Z-scored. This resulted in one unthresholded correlation map for each individual subject for each IFJ seed. These preprocessing steps based on SPM8 and REST were accomplished using the Data Processing Assistant for Resting-State fMRI (DPARSF, version 2.1) [34].

Resulting correlation maps were subjected to a one-sample t-test in SPM8. Results were thresholded at p < 0.001, corrected for multiple comparisons using family-wise error-rate (FWE). For comparison with the MACM results, peak-coordinates of rs-fc were transformed back to Talairach space. Local maxima of the correlation maps (at least 8 mm apart) were compared to meta-analytic results and assigned to brain areas as named in the results and discussion section of the meta-analysis. Additional brain regions were labeled based on the Talairach atlas [35, 36].

Results

Meta-analytic results

The IFJ was associated bilaterally with a set of frontal and insular activations, mainly contained as separate peaks in an expansive cluster spanning anatomically distinct regions. It is exemplarily depicted in Figure 1a) and b) in terms of left hemispherical co-activations with the left seed. Peak activations within the IFJ seeds and corresponding contralateral activations were anatomically labeled inferior frontal gyrus, Brodmann area (BA) 9 or precentral gyrus (BA 6) based on the Talairach atlas. The fronto-insular co-activations comprised an area of the dorso-lateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) on the middle frontal gyrus, confluent ventro-lateral prefrontal areas with neighboring peak coordinates in the inferior frontal gyrus and precentral gyrus (including BA 44 in the left hemisphere), a posterior dorsal area predominantly in the precentral gyrus (BA 4 and 6) and parts of the anterior insula. A cluster in the posterior fronto-median cortex was evident independent from the other frontal locations; see Figure 1c).

Activation likelihood of cortical areas associated with left IFJ activations. (p < 0.001, FDR corrected): a) and b) subregions of the frontal/insular cluster of the left hemisphere (1 inferior frontal gyrus / IFJ, 2 middle frontal gyrus, 3 inferior frontal gyrus, 4 precentral gyrus, 5 precentral gyrus, 6 insula) c) postero-medial frontal cortex (7 left medial frontal gyrus) d) posterior regions (8 left superior / inferior parietal lobule, 9 right inferior parietal lobule, 10 left fusiform gyrus / inferior temporal gyrus / cerebellum.

There were bilateral co-activations in the PPC surrounding the intraparietal sulcus (IPS) mainly in the inferior and superior parietal lobule and partially extending into the precuneus (see Figure 1d). Clusters of significant activation likelihood were also observed surrounding the cerebellar tentorium (Figure 1d) extensively overlapping with the fusiform gyrus. Yet the peak coordinates were mainly located in the cerebellum according to the atlas labels. Subcortical areas associated with left IFJ activations are depicted in Figure 2. Right IFJ associations are comparable. The submaxima of the subcortical clusters were located in the putamen and the thalamus, mainly the medial dorsal nucleus. For a detailed description of all clusters and their submaxima significantly co-activated with the IFJ across studies see Tables 1 and 2.

The locations of the main frontal, parietal, insular and subcortical co-activations are largely comparable in both cerebral hemispheres for both IFJ seeds. The cluster in the left occipito-temporal area was marked in the left hemisphere in conjunction with the left IFJ. The extent of lateralization in the data is visualized in Figure 3.

Intrinsic functional connectivity results

Resting-state analyses yielded a set of brain regions exhibiting correlated activity with the IFJ widely overlapping in all seeds and with the meta-analytic results: bilateral DLPFC, Broca’s area (left seeds only), medial frontal cortex, anterior insula, PPC, occipito-temporal junction, premotor cortex, striatum and thalamus (mainly medial dorsal nucleus). The VLPFC was included in the maps of suprathreshold voxels yet it could not be identified as an independent local maximum (Table 3). Additionally, consistent functional connectivity across seeds was observed with the anterior cingulate cortex and further parts of the cerebellum not covered in the meta-analysis (Additional file 1: Table S1).

Discussion

Network subregions and correspondence with prior network definitions

The lateral frontal clusters of co-activation with the IFJ are formed by a set of confluent separate frontal cortical areas that have been well-characterized in the literature: A group of co-activation peaks rostral to the IFJ, predominantly assigned to the middle fontral gyrus in this analysis highly corresponds to an earlier definition of the mid-dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (mid-DLPFC) as discussed as constituent of a network subserving multiple cognitive demands [37] and other common definitions of dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) in stereotaxic space, e.g. [38, 39]. Another consistent finding was a common co-activation of the IFJ with a set of peak activations in the mid-ventrolateral prefrontal cortex (mid-VLPFC) extending to the anterior insula [37], partially overlapping with other prior definitions of mid-VLPFC and anterior VLPFC [40]. Co-activations in BA 44 resemble the location of Broca’s area in terms of a coordinate-based definition [41].

Observed peak coordinates comprise a range of precentral co-activations. One of these peaks is located close to the frontal eye field. However it better corresponds to an adjacent region that has previously been associated with visuomotor hand conditional activity [42]. Thus in summary, the precentral peaks observed are presumably to some extent more directly associated with task execution than the other observed co-activations, as a range of studies included in this meta-analysis adopted task vs. baseline contrasts. The oberved association in our rs-fc analysis (Table 3) point even to a direct association in terms of neuronal activity.

In addition to these lateral frontal areas the network observed in this meta-analysis comprises medial frontal, posterior parietal and inferior posterior cortical areas (Tables 1 and 2, Figure 1). In this respect results are in line with findings based on other approaches to the study of functional brain networks that did however not directly focus on the IFJ: Similar activations of the medial wall have been observed by Duncan et. al. in their analyses focusing on frontal networks subserving multiple cognitive demands [37]. Similarly, mainly fronto-parietal networks are common findings in functional connectivity analyses based on resting-state fMRI acquisition: A set of lateral frontal (including precentral), insular, medial frontal, posterior parietal and inferior posterior foci form the ‘task-positive network’ in a study by Fox et al. [43]. A similar network has been observed with an exploratory approach based on independent component analyses as well in resting-state fMRI data as in data derived from the BrainMap database analyzed without constraints regarding functional areas or specific tasks [10].

Our results are highly concordant with the involvement of the IFJ in the cognitive control network (CCN) proposed by Cole et. al. [9]. All its components were found to be significantly co-activated with the IFJ: the DLPFC, pre-SMA, anterior insular cortex and PPC as well as matching aspects of the dorsal premotor cortex as far as coordinates are concerned. In contrast, in that study activations in Broca’s area were not tightly coupled with the CCN. Thus, co-activations of the IFJ with Broca’s area in our analysis could be interpreted as an evidence of a relation to additional language processing demands in the tasks included without representing a direct functional connection. Yet rs-fc results support a more direct links in terms of coherent neuronal activity (Table 3).

A recent task-based meta-analysis of cognitive control identified a comparable fronto-parietal CCN including the IFJ. Yet it was labeled as part of the inferior frontal gyrus (IFG) based on its Talairach coordinates (-42, 4 ,30 and 44, 6 32) in that case. The thalamus was also identified in an overall analysis across task-domains, yet it did not survive a formal conjunction analysis of different sub-domains of the construct of cognitive control [11].

Moreover, as a rather consistent finding we observed parallel activations of the IFJ with the basal ganglia (mainly the lentiform nucleus) and the thalamus. Regarding thalamic activation there might be a pitfall in ALE analyses related to the more spherical structure of its nuclei compared to rather flat cortical areas: Thalamic activations arising from different nuclei may be concatenated to a single cluster or even lead to a common peak location near midline. This is especially problematic as the activations observed here are finally assigned to the medial-dorsal nucleus (MDN), indeed a near-midline structure. However, thalamic co-activations form rather separate sub-clusters in both thalamic hemispheres (see Figure 2). In addition it is the MDN that has in previous studies been closely associated with the prefrontal cortex and higher cognitive functions in contrast to more lateral thalamic nuclei: Connections of the MDN with prefrontal brain areas have been observed using diffusion-MRI based tractography in humans including the DLPFC [44, 45] and primary fMRI functional connectivity analyses [46]. This notion is also supported by animal studies [47]. This applies to the thalamic peaks observed here as well: After conversion of the coordinates into MNI space using the corresponding tool provided in GingerALE [28, 48], the left thalamic peak exhibited a probability of 0.87 and the right thalamic peak of 0.79 to be connected with the pre-frontal cortex (without differentiation of subdivisions) according to a probabilistic human tractography atlas based on diffusion-MRI [49–51]. The probability of direct structural connectivity to the posterior parietal cortex was however nearly non-existent, reflecting the fact that diffusion tractography only detects direct fiber connections and not polysynaptical connectivity in functional networks. Human lesion data suggests, that executive dysfunction may arise from combined lesioning of several thalamic structures including the MDN [52].

Comparison of MACM and resting-state results

Meta-analytic results were mostly confirmed using an analysis of intrinsic BOLD signal fluctuations in a presumably independent, publicly available dataset. However, there were some distinct differences: The VLPFC was less clearly identifiable in the resting-state analysis. It was present in the correlation maps but it was not marked as a distinct local maximum. The definition of local maxima in the rs-fc analysis was however constrained by a distance criterion (8 mm). As the VLPFC is wedged in Broca’s area in the left hemisphere and the anterior insula as well as the DLPFC in both hemispheres it might have been missed for that reason.

The ACC has been extensively studied as a region crucial for cognitive control processes [53]. Therefore its identification in the resting-state analysis is in line with previous findings. More inferior parts of the cerebellum identified in the rs-fc analysis might have been missed in the MACM analysis because this inferior region is not usually covered in many functional neuroimaging studies. Superior and middle temporal locations were only identified quite inconsistently when comparing different analysis strategies and can therefore not be considered a verified finding in this study.

Finally there were some pre- and postcentral areas of significant functional connectivity in the analysis of resting-state data that were not observed in the MACM analysis.

In contrast to prior findings in resting-state fMRI analyses based on spatial independent component analyses (ICA) [10] the network observed here appears more interhemispherically connected and additionally overlaps with a fronto-insular component. This may be related to a possible advantage of the meta-analytic connectivity modeling approach adopted here: classical definitions of functional connectivity are based on the analysis of a tight temporal coupling of neurophysiological events [54]. In contrast, functional connectivity in terms of MACM can be interpreted as remote brain areas cooperating in dealing with a task without necessarily exhibiting highly temporally correlated activity. Thus if two rather independent networks in terms of direct structural connectivity or classical functional connectivity are parallel recruited due to comparable task demands, these networks can potentially be identified as one coherent network by MACM [13]. This clear differentiation is however limited by our seed-based rs-fc analysis: Though exhibiting a certain degree of asymmetry, resting-state networks were not limited to the seed’s hemisphere. The main difference might thus arise from different analysis strategies of rs-fc analyses (with spatial ICA emphasizing spatial independence of networks).

There are different possible explanations for the fact that more regions were connected to the IFJ in the analysis of the resting-state dataset compared to the MACM results: Statistical power of both approaches is most likely different. In addition to some baseline-comparisons the BrainMap database contains coordinates from many well-controlled fMRI contrasts to delineate specific behavioral processes by including associated functions (e.g. stimulus-perception and motor responses) in control conditions. The additional correlations in the resting-state data may therefore also represent meaningful and necessary connections of the actual CCN components to brain areas relevant for direct interaction with the environment.

Though the results of both methods are comparable the occasional differences of resting-state and MACM results point to the critical fact that current converging methods applied in the study of complex brain networks may oversimplify the actual functional organization of the human brain as they may not optimally account for the internal organization of such networks and their complex interdependences. It is a notable finding in this context that analyzing fMRI data with an increased temporal resolution using temporal ICA Smith et al. recently reported temporally-independent functional modes of spontaneous brain activity that overlapped with each other and networks known from conventional (seed-correlation or spatial ICA) analyses [55].

Functional implications

As stated in the introduction the IFJ has been studied as a specific brain area in task-based fMRI and meta-analyses limited to a few task domains. Results can be summarized as an involvement of the IFJ in three main component processes of cognitive control (task switching, inhibitory control and working memory) [1–8].

The functional significance of similar fronto-parietal networks as observed in this study has explicitly or implicitly been assessed in numerous often highly specific task-based studies. As reported above, a recent meta-analysis has accumulated such findings based on the BrainMap database [11]: In that meta-analysis cognitive control was operationalized as initiation, inhibition, working memory, flexibility, planning and vigilance. Therefore for each of these sub-domains a set of established tasks (like Flanker, Go/No-Go, Antisaccade, Simon and Stroop tasks for inhibition) was defined and the studies included in the final analyses were restricted to those using these a priori defined tasks. A core network was observed in a conjunction analysis of flexibility, inhibition and working memory that highly overlapped with the CCN observed in the MACM analysis reported here. Thus results point to an involvement of the CCN in all of these functions in a rather unspecific way and to a connection of the IFJ with these other regions in this context.

In contrast to these previous meta-analytic approaches providing information about the IFJ [3] or the CCN [11] the analysis reported in this article is conceptually different (1) in that it is not a priori limited to the context of cognitive control and (2) in that it starts from the IFJ as a previously defined specific location in the brain and therefore adds specificity to the knowledge about this set of connections. Although our analysis aimed at studying connectivity, this framework can also be used to explore functional meanings of the IFJ and the CCN using an analogous approach: The BrainMap database contains structured information (hierarchical meta-data) about behavioral aspects represented in the reported contrasts. Lancaster et al. have reported an automated behavioral analysis based on these meta-data that allows ROI-based searches [56]. Queries regarding the IFJ and the whole network observed here (Additional file 1: Table S2) give a rough estimation of functions associated with the specific coordinate definitions and network maps in this study. They show a statistically significant association with cognitive processes including (working) memory, inhibition and attention but among others also language processing (left hemisphere) and perceptive processes presumably involved in some of the chosen fMRI paradigms.

There is evidence in the meta-analytic results on CCN functions by Niendam et. al. [11] that in addition to the rather unspecific involvement of the CCN core regions additional areas are recruited in a sub-domain-specific manner. This finding is compatible with the recent meta-analytic and task-based finding that within the frontal cortex the IFJ is generally involved in the cognitive control subdomain of switching / flexibility but together with other lateral and medial frontal regions which are recruited more specifically [7, 8]. This in turn is in some way reminiscent of the assumption of a hierarchical organization of the rostro-caudal axis of the frontal lobes [57].

Taken together but potentially limited by the power to detect the involvement of certain brain regions in the different approaches reported the findings seem to support the notion that the IFJ is rather specifically involved in brain systems playing an important role in cognitive control compared to other aspects of brain function.

Limitations

A potential limitation of the MACM approach may arise from the fact that, unlike for example in resting-state fMRI approaches to functional connectivity, results, though including several different functional domains, may be influenced by the overall distribution of tasks in the BrainMap database and correspondingly the distribution of tasks adopted by the whole functional neuroimaging community. However, as discussed above, our results are in line with recent literature regarding IFJ connectivity and a different approach to MACM [58] adopted in the NeuroSynth project (http://www.neurosynth.org/) yields qualitatively comparable results regarding IFJ connectivity, thus at least we suppose that there is no specific bias regarding the BrainMap database and studies included.

Recently it has been argued that the IFJ is functionally dissociated from the directly adjacent posterior part of the inferior frontal gyrus (pIFG) [59]. We have not directly observed this dissociation in terms of different peaks in our analysis. The used cuboid-shaped ROIs were based on prior literature regarding IFJ location in stereotaxic space. However, irregularly shaped ROIs might better conform to the IFJ as a functional brain area and help clarify this issue.

The selection of coordinates most exactly representing the IFJ in stereotaxic space is still a matter of debate. For the meta-analysis we aimed at high specificity regarding the IFJ as a distinct functional brain region without accidentally including other functionally defined areas in our seed. We therefore selected a relatively small ROI based on a large body of literature aggregated in a review based on a number of single studies and meta-analytical data [1]. Yet there is recent data that suggests that the IFJ may be located more medial in some subjects [2]. The meta-analysis might thus have missed some studies reporting IFJ peaks just outside the ROI borders. We addressed this issue by using two different ROI definition strategies in the confirmatory analysis based on resting-state functional connectivity. Results were not qualitatively different regarding the identification of the main constituent brain areas of the CCN) when comparing the more lateral and more medial ROI in each hemisphere.

Though the main finding of this study is a considerably specific connection of the IFJ with brain regions previously characterized as a network engaged in cognitive control from a systems neuroscience perspective, it cannot be reliably deduced from these results that the CCN is indeed ‘only’ involved in cognitive control from a classical neuropsychological perspective. This would be some kind of problematic reverse inference [60]. Though the additional analysis of BrainMap meta-data reported shows a significant association of the IFJ as well as the whole network with ‘cognitive’ tasks, a disjunctive analysis of ‘cognitive control’ in a strict sense does not seem to be feasible in this framework, especially due to the fact that the above-mentioned definition of cognitive control partially overlaps with different categories in the BrainMap meta-data. The behavioral analysis in this framework is also limited by the fact that the set of studies which the analysis is based on overlaps with previous function-guided meta-analyses and also includes, as a minority, studies that have originally led to the fundamental assumption that this specific brain location in the inferior frontal junction area is involved in cognitive control.

Conclusions

Using a metaanalytic connectivity modeling (MACM) approach with data from the BrainMap database of functional neuroimaging studies we characterized the functional connectivity profile of the inferior frontal junction area (IFJ) in terms of co-activations. Based on a large dataset of published peak activations our results confirm the notion that the IFJ is involved in a cognitive control network (CCN). The CCN comprises the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, anterior insula (and neighboring ventrolateral prefrontal cortex), the medial frontal cortex/pre-SMA, parts of the dorsal premotor cortex and the posterior parietal cortex. In addition we identified connectivity of the IFJ with subcortical areas mainly pertaining to the medial dorsal nucleus of the thalamus and an inferior posterior region surrounding the cerebellar tentorium that cannot unequivocally be ascribed to the cerebellum or occipito-temporal junction based on the Talairach atlas. Assigning these locations to the CCN is compatible with prior observations mainly in resting-state fMRI and structural connectivity analyses. Other co-activations most consistently observed include language and motor-related locations. Results were largely confirmed in an additional resting-state fMRI analysis. However, using this approach, the VLPFC was less clearly identified and the CCN was complemented by the anterior cingulate cortex in line with previous observations.

The CCN involving the IFJ has been proposed previously by using task-based and resting-state fMRI data in a number of subjects [9]. Most of the larger studies on fronto-parietal networks relevant for cognition do not denominate the IFJ explicitly. Thus, results reported here establish the formal link between previous work on IFJ functionality and studies focusing on the overall organization of cognitive brain networks on a high formal level of (meta-analytical) evidence. It has to be emphasized however that models like the CCN are only approximations of the human brain’s functional organization and cannot fully capture interdependencies between and specialization within networks.

Still, in light of results suggesting a role of impaired IFJ functionality in early dementia together with this information of functional connectivity of the IFJ in the CCN, the IFJ seems to be a promising starting point to investigate the cognitive control network in further studies and in particular in clinical populations.

Abbreviations

- ACC:

-

Anterior cingulate cortex

- ALE:

-

Activation likelihood estimation

- BA:

-

Brodmann area

- CCN:

-

Cognitive control network

- DLPFC:

-

Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex

- FCP:

-

1000 Functional Connectomes Project

- FDG-PET:

-

Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography

- FDR:

-

False-discovery rate

- fMRI:

-

Functional magnetic resonance imaging

- FWE:

-

Family-wise error-rate

- ICA:

-

Independent component analysis

- IFJ:

-

Inferior frontal junction

- IPS:

-

Intraparietal sulcus

- MACM:

-

Metaanalytic connectivity modelling

- MDN:

-

Medial-dorsal nucleus of the thalamus

- MNI:

-

Montreal Neurological Institute

- pIFG:

-

Posterior part of the inferior frontal gyrus

- PPC:

-

Posterior parietal cortex

- pSMA:

-

Pre-supplementary motor area

- ROI:

-

Region of interest

- rsFC:

-

Resting-state functional connectivity

- VLPFC:

-

Ventrolateral prefrontal cortex.

References

Brass M, Derrfuss J, Forstmann B, von Cramon DY: The role of the inferior frontal junction area in cognitive control. Trends Cogn Sci. 2005, 9 (7): 314-316. 10.1016/j.tics.2005.05.001.

Derrfuss J, Brass M, von Cramon DY, Lohmann G, Amunts K: Neural activations at the junction of the inferior frontal sulcus and the inferior precentral sulcus: interindividual variability, reliability, and association with sulcal morphology. Hum Brain Mapp. 2009, 30 (1): 299-311. 10.1002/hbm.20501.

Derrfuss J, Brass M, Neumann J, von Cramon DY: Involvement of the inferior frontal junction in cognitive control: meta-analyses of switching and Stroop studies. Hum Brain Mapp. 2005, 25 (1): 22-34. 10.1002/hbm.20127.

Derrfuss J, Brass M, von Cramon DY: Cognitive control in the posterior frontolateral cortex: evidence from common activations in task coordination, interference control, and working memory. Neuroimage. 2004, 23 (2): 604-612. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.06.007.

Schroeter ML, Vogt B, Frisch S, Becker G, Barthel H, Mueller K, Villringer A, Sabri O: Executive deficits are related to the inferior frontal junction in early dementia. Brain. 2012, 135 (1): 201-215. 10.1093/brain/awr311.

Levy BJ, Wagner AD: Cognitive control and right ventrolateral prefrontal cortex: reflexive reorienting, motor inhibition, and action updating. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2011, 1224 (1): 40-62. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.05958.x.

Kim C, Cilles SE, Johnson NF, Gold BT: Domain general and domain preferential brain regions associated with different types of task switching: a meta-analysis. Hum Brain Mapp. 2012, 33 (1): 130-142. 10.1002/hbm.21199.

Kim C, Johnson NF, Cilles SE, Gold BT: Common and distinct mechanisms of cognitive flexibility in prefrontal cortex. J Neurosci. 2011, 31 (13): 4771-4779. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5923-10.2011.

Cole MW, Schneider W: The cognitive control network: Integrated cortical regions with dissociable functions. Neuroimage. 2007, 37 (1): 343-360. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.03.071.

Smith SM, Fox PT, Miller KL, Glahn DC, Fox PM, Mackay CE, Filippini N, Watkins KE, Toro R, Laird AR, Beckmann CF: Correspondence of the brain's functional architecture during activation and rest. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009, 106 (31): 13040-13045. 10.1073/pnas.0905267106.

Niendam TA, Laird AR, Ray KL, Dean YM, Glahn DC, Carter CS: Meta-analytic evidence for a superordinate cognitive control network subserving diverse executive functions. Cogn Affect Behav Neurosci. 2012, 12 (2): 241-268. 10.3758/s13415-011-0083-5.

Laird AR, Eickhoff SB, Kurth F, Fox PM, Uecker AM, Turner JA, Robinson JL, Lancaster JL, Fox PT: ALE Meta-Analysis Workflows Via the Brainmap Database: Progress Towards A Probabilistic Functional Brain Atlas. Front Neuroinformatics. 2009, 3: 23.

Cauda F, Cavanna AE, D'agata F, Sacco K, Duca S, Geminiani GC: Functional Connectivity and Coactivation of the Nucleus Accumbens: A Combined Functional Connectivity and Structure-Based Meta-analysis. J Cogn Neurosci. 2011, 23: 2864-2877. 10.1162/jocn.2011.21624.

Eickhoff SB, Jbabdi S, Caspers S, Laird AR, Fox PT, Zilles K, Behrens TE: Anatomical and functional connectivity of cytoarchitectonic areas within the human parietal operculum. J Neurosci. 2010, 30 (18): 6409-6421. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5664-09.2010.

Eickhoff SB, Laird AR, Grefkes C, Wang LE, Zilles K, Fox PT: Coordinate-based activation likelihood estimation meta-analysis of neuroimaging data: a random-effects approach based on empirical estimates of spatial uncertainty. Hum Brain Mapp. 2009, 30 (9): 2907-2926. 10.1002/hbm.20718.

Robinson JL, Laird AR, Glahn DC, Lovallo WR, Fox PT: Metaanalytic connectivity modeling: delineating the functional connectivity of the human amygdala. Hum Brain Mapp. 2010, 31 (2): 173-184.

Toro R, Fox PT, Paus T: Functional coactivation map of the human brain. Cereb Cortex. 2008, 18 (11): 2553-2559. 10.1093/cercor/bhn014.

van den Heuvel MP, Hulshoff Pol HE: Exploring the brain network: a review on resting-state fMRI functional connectivity. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2010, 20 (8): 519-534. 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2010.03.008.

Talairach JT P: Co-Planar Stereotaxic Atlas of the Human Brain. 1988, New York: Thieme Medical Publishers

Fox PT, Lancaster JL: Opinion: Mapping context and content: the BrainMap model. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2002, 3 (4): 319-321. 10.1038/nrn789.

Laird AR, Lancaster JL, Fox PT: BrainMap: the social evolution of a human brain mapping database. Neuroinformatics. 2005, 3 (1): 65-78. 10.1385/NI:3:1:065.

The BrainMap Project. [http://www.brainmap.org/]

Laird AR, Fox PM, Price CJ, Glahn DC, Uecker AM, Lancaster JL, Turkeltaub PE, Kochunov P, Fox PT: ALE meta-analysis: controlling the false discovery rate and performing statistical contrasts. Hum Brain Mapp. 2005, 25 (1): 155-164. 10.1002/hbm.20136.

Multi-image Analysis GUI. [http://ric.uthscsa.edu/mango/]

Kochunov P, Lancaster J, Thompson P, Toga AW, Brewer P, Hardies J, Fox P: An optimized individual target brain in the Talairach coordinate system. Neuroimage. 2002, 17 (2): 922-927. 10.1006/nimg.2002.1084.

1000 Functional Connectomes Project. [http://fcon_1000.projects.nitrc.org/]

Biswal BB, Mennes M, Zuo XN, Gohel S, Kelly C, Smith SM, Beckmann CF, Adelstein JS, Buckner RL, Colcombe S, Dogonowski AM, Ernst M, Fair D, Hampson M, Hoptman MJ, Hyde JS, Kiviniemi VJ, Kotter R, Li SJ, Lin CP, Lowe MJ, Mackay C, Madden DJ, Madsen KH, Margulies DS, Mayberg HS, McMahon K, Monk CS, Mostofsky SH, Nagel BJ, Pekar JJ, Peltier SJ, Petersen SE, Riedl V, Rombouts SA, Rypma B, Schlaggar BL, Schmidt S, Seidler RD, Siegle GJ, Sorg C, Teng GJ, Veijola J, Villringer A, Walter M, Wang L, Weng XC, Whitfield-Gabrieli S, Williamson P, Windischberger C, Zang YF, Zhang HY, Castellanos FX, Milham MP: Toward discovery science of human brain function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010, 107 (10): 4734-4739. 10.1073/pnas.0911855107.

Lancaster JL, Tordesillas-Gutierrez D, Martinez M, Salinas F, Evans A, Zilles K, Mazziotta JC, Fox PT: Bias between MNI and Talairach coordinates analyzed using the ICBM-152 brain template. Hum Brain Mapp. 2007, 28 (11): 1194-1205. 10.1002/hbm.20345.

GingerALE. [http://www.brainmap.org/ale/]

Van Dijk KR, Hedden T, Venkataraman A, Evans KC, Lazar SW, Buckner RL: Intrinsic functional connectivity as a tool for human connectomics: theory, properties, and optimization. J Neurophysiol. 2010, 103 (1): 297-321. 10.1152/jn.00783.2009.

Statistical Parametric Mapping (SPM). [http://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm/]

Song XW, Dong ZY, Long XY, Li SF, Zuo XN, Zhu CZ, He Y, Yan CG, Zang YF: REST: a toolkit for resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging data processing. PLoS One. 2011, 6 (9): e25031-10.1371/journal.pone.0025031.

Forum of resting-state fMRI. [http://www.restfmri.net]

Chao-Gan Y, Yu-Feng Z: DPARSF: A MATLAB Toolbox for "Pipeline" Data Analysis of Resting-State fMRI. Front Syst Neurosci. 2010, 4: 13.

Lancaster JL, Woldorff MG, Parsons LM, Liotti M, Freitas CS, Rainey L, Kochunov PV, Nickerson D, Mikiten SA, Fox PT: Automated Talairach atlas labels for functional brain mapping. Hum Brain Mapp. 2000, 10 (3): 120-131. 10.1002/1097-0193(200007)10:3<120::AID-HBM30>3.0.CO;2-8.

Lancaster JL, Rainey LH, Summerlin JL, Freitas CS, Fox PT, Evans AC, Toga AW, Mazziotta JC: Automated labeling of the human brain: a preliminary report on the development and evaluation of a forward-transform method. Hum Brain Mapp. 1997, 5 (4): 238-242. 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0193(1997)5:4<238::AID-HBM6>3.0.CO;2-4.

Duncan J, Owen AM: Common regions of the human frontal lobe recruited by diverse cognitive demands. Trends Neurosci. 2000, 23 (10): 475-483. 10.1016/S0166-2236(00)01633-7.

MacDonald AW, Cohen JD, Stenger VA, Carter CS: Dissociating the role of the dorsolateral prefrontal and anterior cingulate cortex in cognitive control. Science. 2000, 288 (5472): 1835-1838. 10.1126/science.288.5472.1835.

Weissman DH, Perkins AS, Woldorff MG: Cognitive control in social situations: a role for the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. Neuroimage. 2008, 40 (2): 955-962. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.12.021.

Badre D, Poldrack RA, Pare-Blagoev EJ, Insler RZ, Wagner AD: Dissociable controlled retrieval and generalized selection mechanisms in ventrolateral prefrontal cortex. Neuron. 2005, 47 (6): 907-918. 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.07.023.

Fiebach CJ, Schlesewsky M, Lohmann G, von Cramon DY, Friederici AD: Revisiting the role of Broca's area in sentence processing: syntactic integration versus syntactic working memory. Hum Brain Mapp. 2005, 24 (2): 79-91. 10.1002/hbm.20070.

Amiez C, Kostopoulos P, Champod AS, Petrides M: Local morphology predicts functional organization of the dorsal premotor region in the human brain. J Neurosci. 2006, 26 (10): 2724-2731. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4739-05.2006.

Fox MD, Snyder AZ, Vincent JL, Corbetta M, Van Essen DC, Raichle ME: The human brain is intrinsically organized into dynamic, anticorrelated functional networks. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005, 102 (27): 9673-9678. 10.1073/pnas.0504136102.

Eckert U, Metzger CD, Buchmann JE, Kaufmann J, Osoba A, Li M, Safron A, Liao W, Steiner J, Bogerts B, Walter M: Preferential networks of the mediodorsal nucleus and centromedian-parafascicular complex of the thalamus-A DTI tractography study. Hum Brain Mapp. 2011, 10.1002/hbm.21389. Epub ahead of print

Klein JC, Rushworth MF, Behrens TE, Mackay CE, de Crespigny AJ, D'Arceuil H, Johansen-Berg H: Topography of connections between human prefrontal cortex and mediodorsal thalamus studied with diffusion tractography. Neuroimage. 2010, 51 (2): 555-564. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.02.062.

Buchsbaum MS, Buchsbaum BR, Chokron S, Tang C, Wei TC, Byne W: Thalamocortical circuits: fMRI assessment of the pulvinar and medial dorsal nucleus in normal volunteers. Neurosci Lett. 2006, 404 (3): 282-287. 10.1016/j.neulet.2006.05.063.

Barbas H: Connections underlying the synthesis of cognition, memory, and emotion in primate prefrontal cortices. Brain Res Bull. 2000, 52 (5): 319-330. 10.1016/S0361-9230(99)00245-2.

Laird AR, Robinson JL, McMillan KM, Tordesillas-Gutierrez D, Moran ST, Gonzales SM, Ray KL, Franklin C, Glahn DC, Fox PT, Lancaster JL: Comparison of the disparity between Talairach and MNI coordinates in functional neuroimaging data: validation of the Lancaster transform. Neuroimage. 2010, 51 (2): 677-683. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.02.048.

Johansen-Berg H, Behrens TE, Sillery E, Ciccarelli O, Thompson AJ, Smith SM, Matthews PM: Functional-anatomical validation and individual variation of diffusion tractography-based segmentation of the human thalamus. Cereb Cortex. 2005, 15 (1): 31-39.

Behrens TE, Johansen-Berg H, Woolrich MW, Smith SM, Wheeler-Kingshott CA, Boulby PA, Barker GJ, Sillery EL, Sheehan K, Ciccarelli O, Thompson AJ, Brady JM, Matthews PM: Non-invasive mapping of connections between human thalamus and cortex using diffusion imaging. Nat Neurosci. 2003, 6 (7): 750-757. 10.1038/nn1075.

Thalamic Connectivity Atlas. [http://www.fmrib.ox.ac.uk/connect/]

Van der Werf YD, Scheltens P, Lindeboom J, Witter MP, Uylings HB, Jolles J: Deficits of memory, executive functioning and attention following infarction in the thalamus; a study of 22 cases with localised lesions. Neuropsychologia. 2003, 41 (10): 1330-1344. 10.1016/S0028-3932(03)00059-9.

Carter CS, van Veen V: Anterior cingulate cortex and conflict detection: an update of theory and data. Cogn Affect Behav Neurosci. 2007, 7 (4): 367-379. 10.3758/CABN.7.4.367.

Friston KJ, Frith CD, Liddle PF, Frackowiak RS: Functional connectivity: the principal-component analysis of large (PET) data sets. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1993, 13 (1): 5-14. 10.1038/jcbfm.1993.4.

Smith SM, Miller KL, Moeller S, Xu J, Auerbach EJ, Woolrich MW, Beckmann CF, Jenkinson M, Andersson J, Glasser MF, Van Essen DC, Feinberg DA, Yacoub ES, Ugurbil K: Temporally-independent functional modes of spontaneous brain activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012, 109 (8): 3131-3136. 10.1073/pnas.1121329109.

Lancaster JL, Laird AR, Eickhoff SB, Martinez MJ, Fox PM, Fox PT: Automated regional behavioral analysis for human brain images. Front Neuroinform. 2012, 6: 23.

Badre D, D'Esposito M: Is the rostro-caudal axis of the frontal lobe hierarchical?. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2009, 10 (9): 659-669. 10.1038/nrn2667.

Yarkoni T, Poldrack RA, Nichols TE, Van Essen DC, Wager TD: Large-scale automated synthesis of human functional neuroimaging data. Nat Methods. 2011, 8 (8): 665-670. 10.1038/nmeth.1635.

Chikazoe J: Localizing performance of go/no-go tasks to prefrontal cortical subregions. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2010, 23 (3): 267-272. 10.1097/YCO.0b013e3283387a9f.

Poldrack RA: Can cognitive processes be inferred from neuroimaging data?. Trends Cogn Sci. 2006, 10 (2): 59-63. 10.1016/j.tics.2005.12.004.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the BrainMap online community and David Herr for helpful comments and the contributors of the resting state fMRI dataset (R. L. Buckner, Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Cambridge, MA) through the 1000 Functional Connectomes Project. We acknowledge support by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft and Open Access Publication Fund of the University of Muenster, Germany.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that there are no potential competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

BS conceived the study and analyzed the data. BS and BP participated in study design, interpretation of the results and drafted the manuscript. Both authors approved the final manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

12868_2012_2853_MOESM1_ESM.pdf

Additional file 1: Table S1: Peak coordinates and Talairach atlas labels of brain areas exhibiting correlated activity with the IFJ in the resting-state fMRI analysis that do not conclusively correspond to the cognitive control network observed in the MACM analysis (p < 0.001, FWE corrected, cluster-size-threshold: 10 voxels)., Table S2 – behavioral analysis of BrainMap-data on IFJ and CCN activations, List of References – 139 articles initially identified for the left IFJ, 111 articles initially identified for the right IFJ. (PDF 622 KB)

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Sundermann, B., Pfleiderer, B. Functional connectivity profile of the human inferior frontal junction: involvement in a cognitive control network. BMC Neurosci 13, 119 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2202-13-119

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2202-13-119