Abstract

Background

Hybridization coupled with whole-genome duplication (allopolyploidy) leads to a variety of genetic and epigenetic modifications in the resultant merged genomes. In particular, gene loss and gene silencing are commonly observed post-polyploidization. Here, we investigated DNA methylation as a potential mechanism for gene silencing in Tragopogon miscellus (Asteraceae), a recent and recurrently formed allopolyploid. This species, which also exhibits extensive gene loss, was formed from the diploids T. dubius and T. pratensis.

Results

Comparative bisulfite sequencing revealed CG methylation of parental homeologs for three loci (S2, S18 and TDF-44) that were previously identified as silenced in T. miscellus individuals relative to the diploid progenitors. One other locus (S3) examined did not show methylation, indicating that other transcriptional and post-transcriptional mechanisms are likely responsible for silencing that homeologous locus.

Conclusions

These results indicate that Tragopogon miscellus allopolyploids employ diverse mechanisms, including DNA methylation, to respond to the potential shock of genome merger and doubling.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Whole-genome duplication (polyploidy) has played a major role in eukaryotic evolution [1–6]. In particular, flowering plants have experienced repeated episodes of polyploidy since they shared a common ancestor with the gymnosperms some 300 million years ago [7, 8]. Understanding the genomic consequences of polyploidization, particularly when accompanied by hybridization (allopolyploidy), allows insight into the potential for speciation and adaptation of these novel entities [9, 10]. In particular, the merger and doubling of two divergent genomes can induce different genetic and epigenetic changes in the resulting polyploid [11–16]. Genetic modifications can include gene loss, genome down-sizing, variable mutation rates of the duplicated genes (homeologs), chromosomal rearrangements and regulatory incompatibilities resulting from post-transcriptional modifications in the merged genomes [16–24]. Epigenetic modifications involve heritable changes in gene expression without changes in the nucleotide sequence [25–27] and can include histone modification, DNA methylation, chromatin remodeling, or microRNA or prion activity [28–30]. DNA methylation, the addition of a methyl group at position 5 of the pyrimidine ring of cytosine, is a common mechanism associated with gene silencing in polyploids [31–33]. In general, cytosine methylation is important for maintaining genomic stability and is involved in genomic imprinting, transposon silencing and epigenetic regulation of gene transcription [30, 34–36].

Here, we investigated gene silencing via methylation in the allotetraploid plant Tragopogon miscellus. This species formed repeatedly during the early 1900s in the western United States, following the introduction of the diploid progenitors, T. dubius and T. pratensis, from Europe [37–40]. Previous studies identified extensive homeolog loss [21, 41–43] and chromosomal variation [17] in naturally occurring T. miscellus populations. Two studies [42, 43] also identified homeologous gene silencing in some individuals of T. miscellus, but the mechanism for silencing was not known. In Tate et al. [43], the T. dubius copy of one locus (TDF-44) was silenced in multiple individuals from Pullman, Washington, and Moscow, Idaho. In Buggs et al. [42], six loci showed variable silencing of T. dubius or T. pratensis homeologs in a few individuals from five different populations (Oakesdale, Pullman, and Spangle, Washington; Moscow and Garfield, Idaho). In the present study, we used comparative bisulfite sequencing to determine if these loci were silenced by methylation.

Results and discussion

CG methylation regulates duplicate gene expression

Genomic and bisulfite-converted sequences were acquired for four loci [TDF-44 (putative leucine-rich repeat transmembrane protein kinase) [43], S2 (putative RNA binding protein), S3 (putative NADP/FAD oxidoreductase), and S18 (putative porphyrin-oxidoreductase) [42]] from allopolyploid Tragopogon miscellus and the diploid parents T. dubius and T. pratensis (Table 1). A fifth locus (S8, putative acetyl transferase) identified as silenced in Buggs et al. [42] was not amenable for study because no single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) between the diploids were maintained following bisulfite conversion to distinguish the parental copies in the allopolyploid (Figure 1a). For the four loci examined, we took advantage of SNPs between the diploids to determine if a parental homeolog was silenced by methylation in the T. miscellus individuals. In addition to the partial gene sequences retrieved in the two previous studies [42, 43], 5’ genome walking was undertaken to determine methylation status of the promoter regions. The new sequences were deposited in GenBank (KM260156-KM260165).

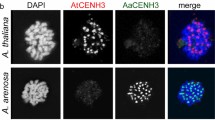

Methylation of homeologous loci in Tragopogon miscellus. Sequence polymorphisms between the diploid parents (Tragopogon dubius and T. pratensis) were used to determine homeolog-specific silencing in T. miscellus allopolyploids. (a) Diagrammatic illustration of the expected chromatogram peaks for genomic and bisulfite-converted sequences when un-methylated or methylated in allopolyploid T. miscellus. This example shows silencing of the T. dubius homeolog. (b) Chromatograms of TDF-44 indicating the position of a methylated CG adjacent to a polymorphic site (red box) in T. miscellus compared to the diploids. (c) Chromatograms of S18 showing an un-methylated CG site in T. miscellus (black box) and the location of a polymorphic site between parental copies (red box). Red, blue, green and yellow colors of the chromatogram correspond to A, C, T and G, respectively. IUPAC ambiguity codes: W = A/T, Y = C/T, R = A/G. BS-converted = bisulfite-converted.

Inspection of the promoter and coding regions identified CG sites, which are common methylation sites in plants [44, 45]. The integrity of bisulfite conversion was determined from the conversion of all the Cs not adjacent to a G into Ts. The loci studied here all showed complete bisulfite conversion in the genic regions, while incomplete conversion at a few sites was detected in the promoter region of TDF-44 for three polyploid individuals (2604-4, 2604-35 and 2605-14). Given that most of the promoter and genic regions were properly converted, the incomplete conversion for TDF-44 does not influence the overall interpretation of the results. Such low frequency of partial bisulfite conversion is commonly due to reaction temperature [46, 47]. Alternatively, these sites could represent varying levels of CHH (H = A, C, or T) or CHG methylation [48].

CG methylation of both sense and antisense strands was detected in the genic and promoter regions of S2 (putative RNA binding protein) and TDF-44 (putative leucine-rich repeat transmembrane protein kinase). TDF-44 included seven CG sites in the promoter region and four in genic regions; the T. dubius homeolog was methylated in 11 of 12 T. miscellus individuals from Pullman and Moscow (Figure 1b, Table 1), which reveals the mechanism of silencing observed in Tate et al. [43]. The exception was individual 2604-22, which retained only the T. dubius genomic homeolog and therefore expressed that copy [43]. Similarly, we found methylation of the S2 locus, which was shown by Buggs et al. [42] to be silenced in two T. miscellus individuals (one each from Garfield and Oakesdale). All CG sites in the promoter (four) and genic (six) regions of S2 were methylated in both individuals. However, both parental homeologs showed CG methylation and sequencing the cloned bisulfite-converted sequences revealed twice as many methylated T. dubius cloned copies as T. pratensis copies. This result suggests that methylation can quantitatively regulate the level of expression of parental copies rather than completely silencing one homeolog. For locus S18 (putative porphyrin-oxidoreductase), which had 11 CG sites in the promoter and 11 in the genic regions, the only methylation detected was one individual that showed hemimethylation of the antisense strand (Table 1). Interestingly, this individual only showed methylation at five of the 11 CG sites in the genic regions.

Analysis of the promoter and genic regions of the other locus (S3-putative NADP/FAD oxidoreductase) did not show methylation of any of the CG sites (Figure 1c, Table 1; S3 included six CG sites in the promoter and three CG sites in the genic regions). Thus, there may be mechanisms other than DNA methylation that are responsible for homeolog-specific silencing. For example, histone deacetylation (causing chromatin condensation) is thought to be responsible for transcriptional repression [49–51]. RNA interference (RNAi) is also widely associated with post-transcriptional silencing via a number of different mechanisms, including mRNA degradation, translational inhibition and the repression of transcription elongation [52–55].

Natural variation in epigenetic patterning is not well understood, but can be an important driver of ecological speciation, as has been found in Viola[56] and Dactylorhiza[57, 58]. Here we find differences in the methylation status and silencing mechanisms in allopolyploid individuals from different populations (Table 1). For the 17 Tragopogon miscellus polyploids studied here, most showed silencing of only one locus in the previous studies of Tate et al. [43] and Buggs et al. [42], but three individuals showed silencing of two or more loci. Some of these loci are silenced by methylation, but others are not, suggesting diverse mechanisms exist within an allopolyploid individual to regulate duplicate gene expression. For the loci that were methylated, two showed 100% CG methylation in genic and promoter regions (TDF-44 and S2), while the third was methylated at 50% of the genic CG sites. As methylation of gene regions is not usually associated with gene silencing in plants [48], how this pattern of methylation contributes to silencing this gene, if at all, is not understood. Comparison of the methylation status of silenced vs. unsilenced loci could lend further insight into the role of gene body methylation in Tragopogon.

Hence, as in other polyploid species [Spartina anglica, [11], Brassica, [59], wheat, [60], rice, [61], Arabidopsis suecica, [62]], genome evolution in Tragopogon miscellus includes DNA methylation as a mechanism to regulate duplicate gene expression, which we demonstrate here for the first time. Previous studies in Tragopogon showed homeolog loss [41–43] and chromosomal repatterning [63, 64] following allopolyploid formation. These latter phenomena seem to be more common mechanisms in T. miscellus populations than expression changes for dealing with the ‘genome shock’ that accompanies hybridization and whole genome duplication [65]. The loci silenced via methylation had the T. dubius copy silenced, which, although a small number, may indicate a ‘preference’ for silencing loci of one progenitor’s genome. This result is true of the T. miscellus polyploids formed with either T. dubius (Pullman) or T. pratensis (Garfield, Moscow, Oakesdale, Spangle) as the maternal parent, so there does not seem to be a maternal ‘imprinting’ influence for the loci studied here. This interpretation is in line with previous studies that have reported a greater tendency of homeolog loss of the T. dubius copy compared to T. pratensis[21, 41–43, 66–68]. Curiously, in the case of rDNA, although T. dubius homeologs are more frequently lost from the polyploid genomes, transcription rates of remaining T. dubius copies are higher than T. pratensis copies [67]. As T. miscellus has shown a high frequency of homeolog loss, but little gene silencing based on the studies to date [21, 41–43, 69], a more comprehensive genome-wide analysis of methylation would help to determine the role of this epigenetic mechanism in shaping the evolution of Tragopogon allopolyploid genomes.

Conclusions

Allopolyploids can employ diverse mechanisms to cope with duplicate and redundant genomes. While previous studies of Tragopogon allopolyploids showed that homeolog loss is a common consequence of allopoyploidization, here we show that DNA methylation can silence one progenitor homeolog or it can regulate the level of expression of the two progenitor homeologs. As further genomic resources for Tragopogon are developed, genome-wide methylation analyses should be undertaken to assess how extensive homeolog methylation is within the allopolyploid species.

Methods

Plant material

DNA for the diploid parents (Tragopogon dubius and T. pratensis) and Tragopogon miscellus used was the same as previous studies [42, 43]. Briefly, DNA was extracted by a modified CTAB method [70] from tissue previously flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen. Leaf tissue was collected from seedlings grown under standardized glasshouse conditions. In total, 17 T. miscellus individuals, each of which previously showed gene silencing (TDF-44 in [43]; S2, S3 and S18 in [42]; Table 1), were examined. Three representatives of each diploid species were also included.

Bisulfite conversion

Prior to bisulfite conversion, genomic DNA of the diploid and polyploid samples was digested with EcoRV (New England Biolabs, UK), which does not cut within the genes of interest. Two micrograms of genomic DNA were digested in a total volume of 100 μl with 80 units of EcoRV, 10X buffer and 10 μg BSA. The reaction was incubated at 37°C overnight (16-18 hours) and the digested DNA cleaned by ethanol precipitation. Bisulfite conversion was carried out using the EZ DNA Methylation kit (Zymo Research, USA). After bisulfite conversion, the single-stranded DNA was quantified using parameters for RNA-40 on a Nanodrop-1000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA).

Amplification and sequencing of genomic and bisulfite-Converted DNA

Primers were designed following a home-made genome walking kit [71]. Separate primers were designed to amplify sense and antisense strands, because after bisulfite conversion the two strands were not precisely complementary, with additional primers designed to perform nested PCR, using Methyl Primer Express software v. 1.0 (Applied Biosystems, USA). Primers 26-29 bp in length were designed to generate an amplicon of ~300 bp and with a C or T near the 3’ end to avoid non-specific binding in the bisulfite-converted DNA. The primers used for amplification of genomic DNA and bisulfite-converted DNA are listed in Additional file 1: Table S1.

Amplification of bisulfite-converted DNA for the primary PCR reaction was conducted in a total volume of 25 μl with 10 ng template DNA, 10 μM of both gene-specific forward and reverse primers, 10X PCR buffer, 10 mM dNTPs and 1 unit of Takara Ex TaqTM polymerase (Takara Biotechnology, Japan). Genomic and bisulfite-converted DNA was amplified using the following PCR program: 95°C for 5 min, 95°C for 1 min, 53°C for 1 min, 72°C for 1 min for the first 5 cycles, then 44 cycles with 95°C for 1 min, 48°C for 1 min, 72°C for 1 min, and a final extension at 72°C for 7 min. Using the nested primers, another PCR was performed using the primary PCR product as template. The resulting nested PCR products were run on a 1.5% agarose gel stained with ethidium bromide and examined using a Gel Doc 2000 system (Bio-Rad, UK). For sequencing, PCR products were treated with Exonuclease I (5 units) and Shrimp alkaline phosphatase (0.5 unit) prior to the cycle sequencing reaction using BigDye Terminator v. 3.1 (Applied Biosystems). The purified products were sequenced with both forward and reverse primers on an ABI DNA Analyzer 3770 at Massey Genome Service (Palmerston North, New Zealand). The resulting sequences were assembled and analyzed in Sequencher v. 4.10.1 (Gene Codes Corporation, USA).

Because both parental homeologs in T. miscellus polyploids showed CG methylation of the S2 locus, cloning was undertaken to determine the methylation status of the parental copies. PCR products of BS-converted DNA were cloned from Tragopogon miscellus individuals 2671-11 and 2688-3 using the TOPO TA cloning kit (Invitrogen, CA, USA). Twelve positive clones per sample were sequenced with T3 and T7 primers using the above-mentioned protocols for sequencing.

Genome walking

In order to determine the methylation status of the promoter region, 5’genome walking was performed following the GenomeWalker manual (Clontech Laboratories, USA) [72]. Genomic DNA of Tragopogon dubius (a diploid parental species) was digested with three different restriction enzymes: EcoRV, DraI and ScaI (New England Biolabs, USA) in separate reaction tubes containing 2.5 μg of genomic DNA, 80 units of restriction enzyme and 10X buffer (New England Biolabs) in a total volume of 100 μl. Reactions were incubated at 37°C for 16-18 hours. These reactions were ethanol precipitated in the presence of 20 μg glycogen and 3M sodium acetate. Adapter ligation to the precipitated, digested genomic DNA was performed in a total volume of 8 μl containing 25 μM adapter, 10X ligation buffer, 3 units of T4 DNA ligase (New England Biolabs) and 0.5 μg of purified DNA. Primary PCR was performed in 50-μl total volume using 10 mM dNTPs, 10X PCR buffer (Takara Biotechnology, Japan), 10 μM of adapter primer AP1 (Forward) and gene-specific primer (Reverse) (gene-specific reverse primers for all the genes S2, S3, S8, S18 and TDF-44 are listed in Additional file 1: Table S1) and 1 unit of Takara Ex Taq polymerase (Takara Biotechnology, Japan). The PCR profile for the primary PCR was as follows: first 7 cycles at 94°C for 25 sec, 72°C for 3 min, then remaining 32 cycles at 94°C for 25 sec, 67°C for 3 min, and a final extension at 67°C for 7 min. Primary PCR products for the nested round were diluted 1:50 in ddH2O. In the secondary PCR, 10 μM nested adapter primer AP2 (forward) and internal gene-specific primers (reverse) were used (Table S1) and 2 μl of diluted primary PCR product were used as template. The secondary PCR profile was as follows: 94°C for 25 sec, 72°C for 3 min for 5 cycles and 94°C for 25 sec, 67°C for 3 min for next 20 cycles, then final extension at 67°C for 7 min. Secondary PCR products were separated on a 1% agarose gel and products from each library were cloned. At least ten positive clones per gene per individual were sequenced. The resulting sequences for each gene were aligned with previously obtained sequences of that gene in Sequencher. New methylation-specific primers were designed to amplify promoter regions from bisulfite-converted DNA. The amplified promoter regions from bisulfite-converted DNA and genomic DNA of all five genes were sequenced for the T. miscellus polyploids and the progenitors T. dubius and T. pratensis.

References

Paterson AH, Chapman BA, Kissinger JC, Bowers JE, Feltus FA, Estill JC: Many gene and domain families have convergent fates following independent whole-genome duplication events in Arabidopsis, Oryza, Saccharomyces and Tetraodon. Trends Genet. 2006, 22 (11): 597-602.

Wolfe KH: Yesterday's polyploids and the mystery of diploidization. Nat Rev Genet. 2001, 2 (5): 333-341.

Hudson CM, Conant GC: Yeast as a window into changes in genome complexity due to polyploidization. Polyploidy and genome evolution. Edited by: Soltis DE, Soltis PS. 2012, Berlin Heidelberg: Springer, 293-308.

Cañestro C: Two rounds of whole-genome duplication: evidence and impact on the evolution of vertebrate innovations. Polyploidy and genome evolution. Edited by: Soltis DE, Soltis PS. 2012, Berlin Heidelberg: Springer, 309-339.

Braasch I, Postlethwait JH: Polyploidy in fish and the teleost genome duplication. Polyploidy and genome evolution. Edited by: Soltis DE, Soltis PS. 2012, Berlin Heidelberg: Springer, 341-383.

Sankoff D, Nadeau J, Vision T, Brown D: Genome archaeology: detecting ancient polyploidy in contemporary genomes. Comparative Genomics, Volume 1. 2000, Netherlands: Springer, 479-491.

Jiao Y, Wickett NJ, Ayyampalayam S, Chanderbali AS, Landherr L, Ralph PE, Tomsho LP, Hu Y, Liang H, Soltis PS, Soltis DE, Clifton SW, Schlaurbaum SE, Schuster SC, Ma H, Leebens-Mack J, de Pamphilis C: Ancestral polyploidy in seed plants and angiosperms. Nature. 2011, 473: 97-100.

Soltis DE, Albert VA, Leebens-Mack J, Bell CD, Paterson AH, Zheng CF, Sankoff D, De Pamphilis CW, Wall PK, Soltis PS: Polyploidy and angiosperm diversification. Am J Bot. 2009, 96 (1): 336-348.

Ramsey J, Schemske DW: Pathways, mechanisms, and rates of polyploid formation in flowering plants. Annu Rev Ecol Syst. 1998, 29: 467-501.

Madlung A: Polyploidy and its effect on evolutionary success: old questions revisited with new tools. Heredity. 2013, 110 (2): 99-104.

Salmon A, Ainouche ML, Wendel JF: Genetic and epigenetic consequences of recent hybridization and polyploidy in Spartina (Poaceae). Mol Ecol. 2005, 14 (4): 1163-1175.

Paun O, Fay MF, Soltis DE, Chase MW: Genetic and epigenetic alterations after hybridization and genome doubling. Taxon. 2007, 56 (3): 649-656.

Ma XF, Gustafson JP: Allopolyploidization-accommodated genomic sequence changes in Triticale. Annals of Botany. 2008, 101 (6): 825-832.

Chen Z: Genetic and epigenetic mechanisms for gene expression and phenotypic variation in plant polyploids. Annual Rev Plant Biol. 2007, 58: 377-406.

Comai L: The advantages and disadvantages of being polyploid. Nat Rev Genet. 2005, 6: 836-846.

Wendel JF, Flagel LE, Adams KL: Jeans, genes, and genomes: cotton as a model for studying polyploidy. Polyploidy and genome evolution. Edited by: Soltis PS, Soltis DE. 2012, Berlin Heidelberg: Springer, 181-207.

Chester M, Gallagher JP, Symonds VV, da Silva AVC, Mavrodiev EV, Leitch AR, Soltis PS, Soltis DE: Extensive chromosomal variation in a recently formed natural allopolyploid species, Tragopogon miscellus (Asteraceae). Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012, 109 (4): 1176-1181.

Jackson S, Chen ZJ: Genomic and expression plasticity of polyploidy. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2010, 13 (2): 153-159.

Tang ZX, Wu M, Zhang HQ, Yan BJ, Tan FQ, Zhang HY, Fu SL, Ren ZL: Loss of parental coding sequences in an early generation of wheat-rye allopolyploid. Int J Plant Sci. 2012, 173 (1): 1-6.

Xiong Z, Gaeta RT, Pires JC: Homoeologous shuffling and chromosome compensation maintain genome balance in resynthesized allopolyploid Brassica napus. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2011, 108 (19): 7908-7913.

Buggs RJA, Chamala S, Wu W, Tate JA, Schnable PS, Soltis DE, Soltis PS, Barbazuk WB: Rapid, repeated, and clustered loss of duplicate genes in allopolyploid plant populations of independent origin. Current Biology. 2012, 22 (3): 248-252.

Doyle JJ, Flagel LE, Paterson AH, Rapp RA, Soltis DE, Soltis PS, Wendel JF: Evolutionary genetics of genome merger and doubling in plants. Annu Rev Genet. 2008, 42: 443-461.

Renny-Byfield S, Kovarik A, Kelly LJ, Macas J, Novak P, Chase MW, Nichols RA, Pancholi MR, Grandbastien M-A, Leitch AR: Diploidization and genome size change in allopolyploids is associated with differential dynamics of low- and high-copy sequences. Plant J. 2013, 74 (5): 829-839.

Zielinski M-L, Scheid OM: Meiosis in polyploids. Polyploidy and genome evolution. Edited by: Soltis DE, Soltis PS. 2012, Berlin Heidelberg: Springer, 33-55.

Liu B, Wendel JF: Epigenetic phenomena and the evolution of plant allopolyploids. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2003, 29 (3): 365-379.

Rapp RA, Wendel JF: Epigenetics and plant evolution. New Phytologist. 2005, 168: 81-91.

Zeng ZX, Zhang T, Li GR, Liu C, Yang ZJ: Phenotypic and epigenetic changes occurred during the autopolyploidization of Aegilops tauschii. Cereal Res Comm. 2012, 40 (4): 476-485.

Lee D, Shin C: MicroRNA–target interactions: new insights from genome-wide approaches. Ann New York Acad Sci. 2012, 1271 (1): 118-128.

Halfmann R, Lindquist S: Epigenetics in the extreme: prions and the inheritance of environmentally acquired traits. Science. 2010, 330 (6004): 629-632.

Vanyushin BF, Ashapkin VV: DNA methylation in higher plants: past, present and future. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011, 1809 (8): 360-368.

Chan SWL, Henderson IR, Jacobsen SE: Gardening the genome: DNA methylation in Arabidopsis thaliana. Nat Rev Genet. 2005, 6 (7): 351-360.

Finnegan EJ, Genger RK, Peacock WJ, Dennis ES: DNA methylation in plants. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 1998, 49: 223-247.

Vanyushin BF: DNA methylation in plants. DNA methylation: basic mechanisms, Volume 301. Edited by: Doerfler W, Böhm P. 2006, Berlin Heidelberg: Springer, 67-122.

He X-J, Chen T, Zhu J-K: Regulation and function of DNA methylation in plants and animals. Cell Res. 2011, 21 (3): 442-465.

Ji L, Chen X: Regulation of small RNA stability: methylation and beyond. Cell Res. 2012, 22 (4): 624-636.

Martienssen RA, Colot V: DNA methylation and epigenetic inheritance in plants and filamentous fungi. Science. 2001, 293 (5532): 1070-1074.

Ownbey M: Natural hybridization and amphiploidy in the genus Tragopogon. Am J Bot. 1950, 37 (7): 487-499.

Soltis DE, Soltis PS: Allopolyploid speciation in Tragopogon - insights from chloroplast DNA. Am J Bot. 1989, 76 (8): 1119-1124.

Ownbey M, McCollum GD: Cytoplasmic inheritance and reciprocal amphiploidy in Tragopogon. Am J Bot. 1953, 40 (10): 788-796.

Soltis PS, Plunkett GM, Novak SJ, Soltis DE: Genetic-variation in Tragopogon species - additional origins of the allotetraploids T. mirus and T. miscellus (Compositae). Am J Bot. 1995, 82 (10): 1329-1341.

Tate JA, Joshi P, Soltis KA, Soltis PS, Soltis DE: On the road to diploidization? Homoeolog loss in independently formed populations of the allopolyploid Tragopogon miscellus (Asteraceae). BMC Plant Biology. 2009, 9: 80-

Buggs RJA, Doust AN, Tate JA, Koh J, Soltis K, Feltus FA, Paterson AH, Soltis PS, Soltis DE: Gene loss and silencing in Tragopogon miscellus (Asteraceae): comparison of natural and synthetic allotetraploids. Heredity. 2009, 103 (1): 73-81.

Tate JA, Ni Z, Scheen A-C, Koh J, Gilbert CA, Lefkowitz D, Chen ZJ, Soltis PS, Soltis DE: Evolution and expression of homeologous loci in Tragopogon miscellus (Asteraceae), a recent and reciprocally formed allopolyploid. Genetics. 2006, 173 (3): 1599-1611.

Shawn JC, Suhua F, Xiaoyu Z, Zugen C, Barry M, Christian DH, Sriharsa P, Stanley FN, Matteo P, Steven EJ: Shotgun bisulphite sequencing of the Arabidopsis genome reveals DNA methylation patterning. Nature. 2008, 452 (7184): 215-219.

Julie AL, Steven EJ: Establishing, maintaining and modifying DNA methylation patterns in plants and animals. Nat Rev Genet. 2010, 11 (3): 204-220.

Grunau C, Clark SJ, Rosenthal A: Bisulfite genomic sequencing: systematic investigation of critical experimental parameters. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001, 29 (13): e65-65.

Genereux DP, Johnson WC, Burden AF, Stoger R, Laird CD: Errors in the bisulfite conversion of DNA: modulating inappropriate- and failed-conversion frequencies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008, 37 (15): e150-

Law JA, Jacobsen SE: Establishing, maintaining and modifying DNA methylation patterns in plants and animals. Nat Rev Genet. 2010, 11: 204-220.

Ma X, Lv S, Zhang C, Yang C: Histone deacetylases and their functions in plants. Plant Cell Reports. 2013, 32 (4): 465-478.

Luo M, Yu C-W, Chen F-F, Zhao L, Tian G, Liu X, Cui Y, Yang J-Y, Wu K: Histone deacetylase HDA6 is functionally associated with AS1 in repression of KNOX genes in Arabidopsis. PLoS Genetics. 2012, 8 (12): e1003114-

Kim J-M, To TK, Seki M: An epigenetic integrator: new insights into genome regulation, environmental stress responses and developmental controls by HISTONE DEACETYLASE 6. Plant Cell Physiol. 2012, 53 (5): 794-800.

Feng X, Guang S: Small RNAs, RNAi and the inheritance of gene silencing in Caenorhabditis elegans. J Genet Genomics. 2013, 40 (4): 153-160.

Ketting RF: The many faces of RNAi. Developmental Cell. 2011, 20 (2): 148-161.

Guang S, Bochner AF, Burkhart KB, Burton N, Pavelec DM, Kennedy S: Small regulatory RNAs inhibit RNA polymerase II during the elongation phase of transcription. Nature. 2010, 465 (7301): 1097-1101.

Carthew RW, Sontheimer EJ: Origins and mechanisms of miRNAs and siRNAs. Cell. 2009, 136 (4): 642-655.

Herrera CM, Bazaga P: Epigenetic differentiation and relationship to adaptive genetic divergence in discrete populations of the violet Viola cazorlensis. New Phytologist. 2010, 187: 867-876.

Paun O, Bateman R, Fay M, Luna J, Moat J, Hedren M, Chase M: Altered gene expression and ecological divergence in sibling allopolyploids of Dactylorhiza (Orchidaceae). BMC Evol Biol. 2011, 11 (1): 113-

Paun O, Bateman RM, Fay MF, Hedren M, Civeyrel L, Chase MW: Stable epigenetic effects impact adaptation in allopolyploid orchids (Dactylorhiza: Orchidaceae). Mol Biol Evol. 2010, 27 (11): 2465-2473.

Zhang X, Ge X, Shao Y, Sun G, Li Z: Genomic change, retrotransposon mobilization and extensive cytosine methylation alteration in Brassica napus introgressions from two intertribal hybridizations. Plos One. 2013, 8 (2): e56346-

Hu Z, Han Z, Song N, Chai L, Yao Y, Peng H, Ni Z, Sun Q: Epigenetic modification contributes to the expression divergence of three TaEXPA1 homoeologs in hexaploid wheat (Triticum aestivum). New Phytologist. 2013, 197 (4): 1344-1352.

Wang Y, Wang X, Lee T-H, Mansoor S, Paterson AH: Gene body methylation shows distinct patterns associated with different gene origins and duplication modes and has a heterogeneous relationship with gene expression in Oryza sativa (rice). New Phytologist. 2013, 198 (1): 274-283.

Zhang X, Yazaki J, Sundaresan A, Cokus S, Chan SWL, Chen H, Henderson IR, Shinn P, Pellegrini M, Jacobsen SE, Ecker JR: Genome-wide high-resolution mapping and functional analysis of DNA methylation in Arabidopsis. Cell. 2006, 126 (6): 1189-1201.

Chester M, Lipman MJ, Gallagher JP, Soltis PS, Soltis DE: An assessment of karyotype restructuring in the neoallotetraploid Tragopogon miscellus (Asteraceae). Chromosome Res. 2013, 21 (1): 75-85.

Lim KY, Soltis DE, Soltis PS, Tate JA, Matyášek R, Šrubařová HS, Kovařík A, Pires JC, Xiong Z, Leitch AR: Rapid chromosome evolution in recently formed polyploids in Tragopogon (Asteraceae). PLoS One. 2008, 3 (10): 1-13.

McClintock B: The significance of responses of the genome to challenge. Science. 1984, 226: 792-801.

Buggs RJA, Chamala S, Wu W, Gao L, May GD, Schnable PS, Soltis DE, Soltis PS, Barbazuk WB: Characterization of duplicate gene evolution in the recent natural allopolyploid Tragopogon miscellus by next-generation sequencing and Sequenom iPLEX MassARRAY genotyping. Mol Ecol. 2010, 19: 132-146.

Matyasek R, Tate J, Lim Y, Srubarova H, Koh J, Leitch A, Soltis D, Soltis P, Kovarik A: Concerted evolution of rDNA in recently formed Tragopogon allotetraploids is typically associated with an inverse correlation between gene copy number and expression. Genetics. 2007, 176: 2509-2519.

Kovarik A, Pires JC, Leitch AR, Lim KY, Sherwood AM, Matyasek R, Rocca J, Soltis DE, Soltis PS: Rapid concerted evolution of nuclear ribosomal DNA in two Tragopogon allopolyploids of recent and recurrent origin. Genetics. 2005, 169 (2): 931-944.

Buggs RJA, Zhang LJ, Miles N, Tate JA, Gao L, Wei W, Schnable PS, Barbazuk WB, Soltis PS, Soltis DE: Transcriptomic shock generates evolutionary novelty in a newly formed, natural allopolyploid plant. Current Biology. 2011, 21 (7): 551-556.

Doyle JJ, Doyle JL: A rapid DNA isolation procedure for small quantities of fresh leaf tissue. Phytochemical Bulletin. 1987, 19: 11-15.

Warnecke PM, Stirzaker C, Song J, Grunau C, Melki JR, Clark SJ: Identification and resolution of artifacts in bisulfite sequencing. Methods. 2002, 27 (2): 101-107.

Siebert PD, Chenchik A, Kellogg DE, Lukyanov KA, Lukyanov SA: An improved PCR method for walking in uncloned genomic DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995, 23 (6): 1087-1088.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a Massey University Research Fund grant to JAT. TS was supported by a Ph.D. scholarship from the Higher Education Commission of Pakistan. Two anonymous reviewers provided valuable comments that improved the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

TS and JAT designed the experiments. TS conducted experiments. TS, VS, DES, PSS and JAT analyzed data and wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

12864_2014_6373_MOESM1_ESM.xlsx

Additional file 1: Table S1: List of primers used for amplification of bisulfite-converted DNA and 5’ genome walking. (XLSX 18 KB)

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Sehrish, T., Symonds, V.V., Soltis, D.E. et al. Gene silencing via DNA methylation in naturally occurring Tragopogon miscellus (Asteraceae) allopolyploids. BMC Genomics 15, 701 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2164-15-701

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2164-15-701