Abstract

Background

Infertility affects ~10-15% of couples trying to have children, in which the rate of male fertility problems is approximately at 30-50%. Copy number variations (CNVs) are DNA sequences greater than or equal to 1 kb in length sharing a high level of similarity, and present at a variable number of copies in the genome; in our study, we used the canine species as an animal model to detect CNVs responsible for male infertility. We aim to identify CNVs associated with male infertility in the dog genome with a two-pronged approach: we performed a sperm analysis using the CASA system and a cytogenetic-targeted analysis on genes involved in male gonad development and spermatogenesis with fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH), using dog-specific clones. This analysis was carried out to evaluate possible correlations between CNVs on targeted genes and spermatogenesis impairments or infertility factors.

Results

We identified two genomic regions hybridized by BACs CH82-321J09 and CH82-509B23 showing duplication patterns in all samples except for an azoospermic dog. These two regions harbor two important genes for spermatogenesis: DNM2 and TEKT1. The genomic region encompassed by the BAC clone CH82-324I01 showed a single-copy pattern in all samples except for one dog, assessed with low-quality sperm, displaying a marked duplication pattern. This genomic region harbors SOX8, a key gene for testis development.

Conclusion

We present the first study involving functional and genetic analyses in male infertility. We set up an extremely reliable analysis on dog sperm cells with a highly consistent statistical significance, and we succeeded in conducting FISH experiments on sperm cells using BAC clones as probes. We found copy number differences in infertile compared with fertile dogs for genomic regions encompassing TEKT1, DNM2, and SOX8, suggesting those genes could have a role if deleted or duplicated with respect to the reference copy number in fertility biology. This method is of particular interest in the dog due to the recognized role of this species as an animal model for the study of human genetic diseases and could be useful for other species of economic interest and for endangered animal species.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Infertility affects ~10-15% of couples that try to have children [1, 2]. During the last 15 years, attention of the scientific world to male-related fertility issues has grown exponentially, so that the percentage of male fertility problems in couples that cannot achieve a pregnancy raised till nowadays, when it is approximately estimated at 30-50% [3]. Genetic causes of male infertility involve a large group of genes leading to multifactorial male differentiation defects, abnormal spermatogenesis or impaired sperm function; the estimated number of these genes is ~2000; most of them are present on the autosomic chromosomes, while ~30 genes encompass the Y chromosome [4]. Cytogenetic abnormalities in somatic cells associated with male infertility are very frequent, and can be found at different rates (from 3% to 19%) depending on the particular fertility problem [5]. Copy number variations (CNVs) are defined as DNA sequences ≥1 kb in length that are present at a variable number of copies in the genome and sharing high level of similarity (≥95%). CNVs in the human genome are at least 1,447, harboring hundreds of genes and covering 12% of the entire genome [6], leading to high genetic variability among populations or even individuals. [7]. CNVs can predispose to genomic disorders or complex genetic diseases such as autism and schizophrenia due to non correct recombinative events between non allelic CNVs [8–11]. Few studies relate human infertility to CNVs, and most of them did not show any clear association between phenotype and genotype [12].

One targeted assay on copy number variations of SPANX gene family, coding for a protein involved in sperm development, showed no differences in the average CNV patterns between fertile and infertile men [13]. In our study, we used the dog as an animal model to detect CNVs responsible of infertility. We aim to identify CNVs associated with male infertility in dog genome with a cytogenetic targeted analysis on genes involved in male gonad development and spermatogenesis. In particular, morphological and functional analyses of the canine semen samples were performed on a Computer Assisted Sperm Analyzer (CASA) device followed by Fluorescent In Situ Hybridization (FISH) performed on dog sperm cells using Canis familiaris Bacterial Artificial Chromosomes (BAC) clones, in order to evaluate possible correlations between CNVs on targeted genes and spermatogenesis impairments or infertility factors. Awareness about the importance of deep studies on Canis familiaris genome has been increasing during last years. First, we chose canine species for the increasing role of the ever-expanding purebred dogs industry in the economic and social environments; indeed, dog infertility results in substantial financial losses to canine breeding industry. Second, from a human-related point of view, dog attracts much interest for its pathological correlation with Homo sapiens. Up to at least 370 known canine genetic diseases have been described, and more than an half of them (215) show great similarity to human diseases (i.e. epilepsy [14], Alzheimer’s disease [15], chronic hepatitis [16], type 2 diabetes [17] or cancer [18, 19]); for 41 of them, the abnormal disease-causing gene product is the same in both species. Purebred dogs are more prone to genetic disorders compared with mixed-breed dogs, because of their genetic isolation caused by the pedigree barrier used by dog breeders during last centuries of breed selections [20]. Last, dog represents a good model because of the ease in retrieving samples to be analyzed in replicate, differently from human where it is not ethically accepted to perform study on sperm samples.

Methods

Semen physiologic analysis

Use of Computer-Aided Sperm Analysis (CASA) system for dog semen samples has been standardized during the last years [21, 22]. The Hamilton-Thorn computer-aided semen analyzer (IVOS 12.3) has been used for semen analyses. We analyzed 12 purebred dogs and classified them according to their reproductive clinical features and medical history in: infertile, partial infertile and fertile. All subjects were checked and did not show any systemic pathology. Dogs age ranged from 2 to 12 years old with different body sizes (from 7 to 59 kg) (Additional file 1: Table S1). In oligo-azoospermic subjects, seminal ALP (alkaline phosphatase) was evaluated in order to exclude obstructive or partially obstructive ejaculation (only 1–3 fractions). Seminal ALP is produced in the epididymis. In normal ejaculates, ALP concentrations are >5000 U/L; in cases of incomplete ejaculation, it is <5000 U/L and often <2000 U/L [23, 24]. Oligo-azoospermic subjects showed ALP values higher than 5000 U/L. Semen samples were collected by manual manipulation in presence of a teaser bitch in estrous phase of the reproductive cycle [25] and we diluted them in PBS (Phosphate Buffer Saline, P4417, Sigma, Milan, Italy) [26].

Motility parameters measurements have been carried out in triplicate in order to minimize systematic bias; thus, spermatozoa in slide chambers have been immobilized by heat with a specific soldering iron, then a morphology assessment has been performed.

Sperm morphology was visually assessed on images taken at the CASA system, including 5 fields per sample, containing a mean value of 100 cells. Sperm abnormalities were recorded according to Kruger classification criteria [27] as reported by WHO manual [28]. Additionally, all subjects underwent clinical and ultrasound examination of testes and prostate, in order to assess their size and appearance which were found as being normal.

FISH analysis on lymphocytes

Dog lymphocytes derived from peripheral blood samples treated as previously described [29] have been fixed onto slides and viewed at a phase contrast microscope to verify a proper number of metaphases and good nuclei morphology. Incubation at 90°C for 1h30′ contributed to sample fixation and dehydratation, whereas a treatment with 0.005% pepsin/HCl 0.01 M eliminated cytoplasm proteins in order to obtain better hybridization rates. Subsequent treatments in PBS 1X, MgCl2 0.5 M, 8% paraformaldehyde and 70%/90%/absolute alcohols allowed a proper stabilization, fixation and dehydratation of metaphases and nuclei DNA molecules. FISH experiments were performed as previously described [30]. FISH probes were canine-specific BACs (Children’s Hospital Oakland Research Institute, Oakland, California) covering 23 genes with previously reported associations with human male infertility (Table 1). Digital images were obtained using a Leica epifluorescence microscope equipped with a cooled CCD camera. Pseudocoloring and merging of images were performed using Adobe Photoshop™ software.

FISH analysis on sperm cells (S-FISH)

We modified and standardized for our specific purposes a previously reported sperm preparation protocol for FISH analysis [31]. Sperm cells resuspended in methanol/acetic acid (at a 3:1 ratio) were applied onto slides, dehydrated in 80% methanol at -20°C for 20'; to decondense sperm cell chromatin, slides were treated with a DTT (DL-Dithiotreitol, Sigma-Aldrich) 10 mM solution for 25′ and subsequently in a DTT 1 mM/SDS (Sodium Dodecyl Sulphate, J.T. Baker) 10 mM/Tris solution for 2h30′. After that, sperm cells with decondensed chromatin were re-dehydrated in 80% methanol at -20°C for 20′ and then stored at -20°C. Following steps of FISH analysis were carried out in the same way as described above.

Statistical analysis

To measure of the strength of the linear relationship between post-analysis physiological features and hybridized probes signals Pearson’s correlation coefficient were calculated by using the SAS™ package v9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). P-value was used to assess the significance of the correlation coefficient. If this probability was lower than 5% (P <0.05) the correlation coefficient was considered statistically significant.

Results

Semen evaluation test

Sperm samples were analyzed for functional and morphological properties. We evaluated different parameters to assess a complete analysis on sperm cells: we assessed quantitative (concentration and total sperm output-TSO [32]), and qualitative parameters (total and progressive motility). Motility subcategories were also measured: average path velocity (VAP), straight-line rectilinear velocity (VSL), curvilinear velocity (VCL), amplitude of lateral head displacement (ALH), beat cross frequency (BCF), straightness (STR), and linearity (LIN). Progressively motile cells subparameters (rapid, medium, slow and static) percentages were evaluated as well. Moreover, morphological aspects of sperm cells were carefully considered (Additional file 1: Table S1).

Based on total and progressive motility, total sperm output (TSO) and concentration parameters, we preliminarily evaluated 7 samples (dog #1 to #7) as good quality, 2 samples (dog #8 and #9) as mediocre and 3 samples (dog #10 to #12) as low-quality. Subsequently, we were able to confirm these classifications by analyzing progressive motility subcategories and speed motility subdivisions (Additional file 1: Table S1). Dog #6 showed low TSO and concentration values, but it showed excellent values in the other parameters, thus it was considered as a good quality sample. Although high TSO and concentration values, Dog #8 was evaluated as mediocre according to the high rate of sperm cells showing residual proximal cytoplasmic droplets and coiled tails (Figure 1, Additional file 1: Table S1). In addition, we reported suboptimal values for progressive motility subparameters (Figure 2). Dog #12 showed severe azoospermia by the absence of any sperm cell in his ejaculate; for this reason in this subject it was not possible to perform any sperm test (Additional file 2: Figure S1 and Additional file 1: Table S1).

FISH analysis on lymphocytes

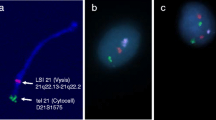

We could retrieve blood samples from 6 out of 12 dogs, then those samples were analyzed by 2 colors FISH using a single dog BAC clone (CH82-297B18 or CH82-53P08) as single control region, and one of the 23 previously selected BAC probes to define gene copy number; among these samples, 4 out of 6 dogs belonged to the good quality cohort (dogs #1, #2, #5 and #7) and the other two to the low-quality group (#11 and #12). Two regions (CH82-321J09 and CH82-509B23) were found to be duplicated in all samples except for the azoospermic dog #12, whereas the genomic region encompassed by the BAC clone CH82-324I01 showed a single-copy pattern in all samples except for the dog #11 (low-quality group), displaying a marked duplication pattern (3 copies) (Figure 3A and Additional file 3: Table S2). The rest of analyzed regions showed a variable copy number in canine genome and no direct correlation was found between phenotypes and copy numbers. All the results were compared to the most comprehensive catalog of canine structural variation to date published in 2011 [33], although the breeds analyzed in that catalog do not match with some of the breeds (such a Cane Corso and Dogo Argentino) we could retrieve samples.

FISH experiments on lymphocytes. A. Co-hybridizations of BACs CH82-321J09, CH82-324I01, and CH82-509B23 (Cy-3 labeled, in red) with single-copy control BACs CH82-297B18 and CH82-53P08 (Cy-5 labeled, in green) on lymphocytes from 6 samples. Bigger sizes of hybridization signals for BAC CH82-321 J09 and CH82-509B23 compared with single-copy control BACs CH82-297B18 and CH82-53P08 reveal duplications in those genomic regions in all the analyzed samples except for sample #12. Sample #11 shows bigger hybridization signals for probe CH82-324I01 compared with other samples and single-copy control probe, suggesting a clear and isolated duplication pattern. B. same co-hybridizations on sperm cells from the 5 out of the 6 samples shown in part A.

FISH analysis on sperm cells (S-FISH)

We analyzed the three genomic regions spanned by BACs CH82-321J09, CH82-509B23 and CH82-324I01 performing Fluorescent In Situ Hybridization analysis onto sperm cells (S-FISH) deriving from the samples we could retrieve blood; case #12 could not be analyzed as it resulted azoospermic. S-FISH analysis was carried out in order to compare the duplication patterns between somatic and germinal cell. We counted fluorescence signals in at least 100 nuclei, then we calculated the average signal(s) number per cell; we were able to confirm the previously reported results, even the assessment of the heterozygous patterns (Figure 3B and Table 2 and Additional file 4: Table S3). Statistically significant correlations between semen quality parameters and hybridized probes signals of BAC clones (average/BAC Additional file 4: Table S3) were detected. In particular, a high percentage of sperm in the static subcategory was positively related to increased signals of BAC clone CH82-405N09 (r = 0.67 P = 0.02), CH82-53P08 (r = 0.66 P = 0.02) and CH82-209K14 (r = 0.59 P = 0.05). This pattern was further confirmed by the negative correlation between BAC clone CH82-405N09 signals and the percentage of progressive motility (r = -0.67 P = 0.02), and between BAC clone CH82-53P08 signals and total motility (r = -0.61 P = 0.04). In addition a high percentage of rapid sperm corresponded to low signals of BAC clone CH82-405N09 (r = -0.72 P = 0.01) and CH82-209K14 (r = -0.62 P = 0.04). Negative correlations were also found between kinetics parameters VAP, VSL, VCL, ALH and signals of BAC clone CH82-253P13 (r = -0.71 P = 0.01), (r = -0.63 P = 0.03), (r = -0.76 P = 0.006), and (r = -0,69 P = 0.01) respectively. Overall, increased BAC signals corresponded to low semen quality.

We performed a parallel analysis by hybridizing on sperm cells a probe covering the genomic region harboring DBY gene, on dog X chromosome (CH82-297B18 - chrX:35,709,014-35,892,273) on the 11 dog sperm samples. We carried out this analysis in order to see whether germ cells bearing X and Y chromosome were sorted in a physiological ratio of 1:1; moreover, this analysis was used to assess the integrity of sperm DNA after the chromatin decondensation protocol. Higher concentrations of DTT would overdecondense sperm chromatin, leading to the visualization of several hybridization signals even in single-copy regions. We counted at least 300 nuclei per sample, and we found percentages of X chromosome bearing germ cells ranging from ~48% to ~52% (Additional file 5: Table S4).

Discussion

Infertility includes a wide range of phenotypes, most of them difficult to decipher, and whose causes are frequently unknown. Environmental, genetic and behavioral features participate in inducing a wide spectrum of different forms of infertility. In our study we tried to understand if the presence of chromosomal abnormalities as Copy number variations (CNVs) could be a cause of male infertility, using canine species as a model. Scientific interest in CNVs has grown exponentially during last years, and some investigators found out interesting correlations between male infertility and CNVs in genes involved in related biological pathways [12, 13, 34, 35]. We carried out for the first time a molecular genomic characterization of potential roles of CNVs in dogs in mediating male infertility, accompanied by detailed assessment of sperm quality. Infertile male dogs represent tough economical losses for breeders, thus a reliable and accurate diagnostic tool to fully characterize causes and features of these pathologies is highly requested in this environment. We used a two-pronged approach to quantify and characterize fertility in male dog: morphological and physiological aspects of male dog sperm cells were investigated, as well as genomic variations among samples for key fertility genes. On the morphology side, we found the presence of cytoplasmic droplets as well as coiled tails in the sperm cells of few samples. Cytoplasmic droplets are not deleterious to sperm motility, however they may be predictive of some forms of human male infertility [36], while coiled tails may indicate epididymal disfunction [37]. Moreover, we have developed a new standardized protocol for FISH using BAC probes on sperm cells (S-FISH). In previous similar studies different probes like Whole-Chromosome Paintings (WCP), Partial Chromosome Paintings (PCP) or chromosome-specific probes were used, leading to less detailed characterization of genomic duplications/deletions [31, 38, 39]. Using BAC probes we focused our analysis to more specific genomic regions, in particular regions harboring genes playing a key role in mammalian male fertility. We demonstrated a great reliability for this protocol by validating duplication/deletion patterns found in lymphocytes from the same samples, and confirming a 1:1 ratio between X- and Y-chromosome bearing sperm cells using a “sperm sorting by FISH” method with an X-specific BAC probe. In our analysis, we found deletion patterns for BAC probes CH82-321J09 and CH82-509B2 (dog #12, azoospermic) and duplication of BAC CH82-324I01 (dog #11) in the sample showing the most severe phenotypes. BAC CH82-321J09 covers a genomic region harboring 7 genes, among them DNM2 has an important function in Sertoli cells for tubulobulbar complex (TBC) formation and spermatid release [40]. To date, no studies reported any specific correlation between male infertility and DNM2 gene duplication/deletion. BAC 509B23 harbors 6 known dog protein-coding genes; among them TEKT1 represents a good candidate for its role in spermatogenesis and sperm cells movement [41, 42]. No reports have been published to date on the causative effect of deletion/duplication in this genomic region. BAC CH82-324I01 contains 2 full and 3 partial genes; SOX8 has been taken into consideration for its involvement in embryonic testis development and spermatogenesis regulation in adults [43] (Additional file 6: Table S5). In the same study, Sox8 null mice developed a severe infertility phenotype, with spermiation failure and impairment of spermatogenic cycle. In our case, dog #11 showing oligozoospermia and asthenozoospermia carries an extra copy of this gene, likely leading to the disorganisation of spermatogenesis steps (Table 2).

Moreover, results from sperm sorting by FISH analysis state the absence of any alteration in sex chromosomes segregation in samples. This suggests that, as well as for sex chromosomes, meiosis errors among autosomal chromosomes are likely to be excluded for the samples analyzed. With the development of a well-characterized list of male fertility-related genes to test, S-FISH analysis could represent a useful tool for breeders to verify any discrepancy in young dogs (i.e. before matings) as well as in adult infertile dogs to understand the causes underlying this pathological condition; the routine setup of this two-pronged approach would be dramatically less time- and money-consuming for breeders, who will be able to avoid expensive and difficult matings for verified low quality samples; this will result in the selection of new generations of purebred dogs with high economic value. Moreover, on the clinical point of view, understanding the genetic cause could represent a chance to develop targeted therapies to restore fertility in low quality samples.

Conclusion

This is the first study involving functional and genetic analyses in male infertility with Computer Assisted Sperm Analysis and Fluorescent In Situ Hybridization assay; we succeeded in setting up both an extremely reliable and objective functional analysis with a highly consistent statistical significance (P <0.0001), and an accurate sperm chromatin decondensation treatment for more stringent targeted FISH analysis, with small probes as BAC. So far, published studies using sperm-FISH analyses were less specific, using marker probes for chromosomes X, Y, 13, 18 and 21 to show aneuploidies [44]. We found copy number differences in infertile dogs compared with fertile for genomic regions encompassing TEKT1, DNM2 and SOX8 genes, suggesting a role in infertility biology if deleted or duplicated with respect to reference copy number. Bigger cohorts need to be screened to unravel which part these genomic regions play in male infertility causes; however, these preliminary results could suggest those three genes could have a potential role in male infertility onset when deleted/duplicated. This is because those genes act in very early phases of embryonic development and/or in key stages of spermatogenesis; hence, a change in the normal copy number of these specific genes, either deletions or duplications, is likely to give rise to impairments in the normal development of these phenotypic factors.

This correlation method has a main interest in the dog, due to the recognized role of this species as an animal model for the study of genetic deseases in humans, and could be useful in the near future for other species of economical interest, as bovine, equine and ovine, as well as for endangered animal species.

References

de Kretser DM: Male infertility. Lancet. 1997, 349 (9054): 787-790. 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)08341-9.

Seli E, Robert C, Sirard MA: OMICS in assisted reproduction: possibilities and pitfalls. Mol Hum Reprod. 2010, 16 (8): 513-530. 10.1093/molehr/gaq041.

Lipshultz LI HS: Infertility in the male. 1997, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Hargreave TB: Genetic basis of male fertility. Br Med Bull. 2000, 56 (3): 650-671. 10.1258/0007142001903454.

Yoshida A, Miura K, Shirai M: Cytogenetic survey of 1,007 infertile males. Urol Int. 1997, 58 (3): 166-176. 10.1159/000282975.

Redon R, Ishikawa S, Fitch KR, Feuk L, Perry GH, Andrews TD, Fiegler H, Shapero MH, Carson AR, Chen W, et al: Global variation in copy number in the human genome. Nature. 2006, 444 (7118): 444-454. 10.1038/nature05329.

Perry GH, Dominy NJ, Claw KG, Lee AS, Fiegler H, Redon R, Werner J, Villanea FA, Mountain JL, Misra R, et al: Diet and the evolution of human amylase gene copy number variation. Nat Genet. 2007, 39 (10): 1256-1260. 10.1038/ng2123.

Lupski JR: Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease: a gene-dosage effect. Hosp Pract (Minneap). 1997, 32 (5): 83-84. 89–91, 94–85 passim

Lupski JR: Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease: lessons in genetic mechanisms. Mol Med. 1998, 4 (1): 3-11.

Lakich D, Kazazian HH, Antonarakis SE, Gitschier J: Inversions disrupting the factor VIII gene are a common cause of severe haemophilia A. Nature Genet. 1993, 5 (3): 236-241. 10.1038/ng1193-236.

Antonacci F, Kidd JM, Marques-Bonet T, Teague B, Ventura M, Girirajan S, Alkan C, Campbell CD, Vives L, Malig M, et al: A large and complex structural polymorphism at 16p12.1 underlies microdeletion disease risk. Nature Genet. 2010, 42 (9): 745-750. 10.1038/ng.643.

Stouffs K, Vandermaelen D, Massart A, Menten B, Vergult S, Tournaye H, Lissens W: Array comparative genomic hybridization in male infertility. Hum Reprod. 2012, 27 (3): 921-929. 10.1093/humrep/der440.

Hansen S, Eichler EE, Fullerton SM, Carrell D: SPANX gene variation in fertile and infertile males. Syst Biol Reprod Med. 2010, 55: 18-26.

Ekenstedt KJ, Patterson EE, Mickelson JR: Canine epilepsy genetics. Mamm Genome. 2012, 23 (1–2): 28-39.

Head E: A canine model of human aging and Alzheimer’s disease. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013, 1832 (9): 1384-1389. 10.1016/j.bbadis.2013.03.016.

Favier RP, Spee B, Schotanus BA, van den Ingh TS, Fieten H, Brinkhof B, Viebahn CS, Penning LC, Rothuizen J: COMMD1-deficient dogs accumulate copper in hepatocytes and provide a good model for chronic hepatitis and fibrosis. PLoS One. 2012, 7 (8): e42158-10.1371/journal.pone.0042158.

Jeong YW, Lee GS, Kim JJ, Park SW, Ko KH, Kang M, Kim YK, Jung EM, Hyun SH, Shin T, et al: Establishment of a canine model of human type 2 diabetes mellitus by overexpressing phosphoenolypyruvate carboxykinase. Int J Mol Med. 2012, 30 (2): 321-329.

Angstadt AY, Thayanithy V, Subramanian S, Modiano JF, Breen M: A genome-wide approach to comparative oncology: high-resolution oligonucleotide aCGH of canine and human osteosarcoma pinpoints shared microaberrations. Cancer Genet. 2012, 205 (11): 572-587. 10.1016/j.cancergen.2012.09.005.

Pinho SS, Carvalho S, Cabral J, Reis CA, Gartner F: Canine tumors: a spontaneous animal model of human carcinogenesis. Transl Res. 2012, 159 (3): 165-172. 10.1016/j.trsl.2011.11.005.

Ostrander EA, Galibert F, Patterson DF: Canine genetics comes of age. Trends Genet. 2000, 16 (3): 117-124. 10.1016/S0168-9525(99)01958-7.

Iguer-ouada M, Verstegen JP: Evaluation of the “Hamilton Thorn computer-based automated system” for dog semen analysis. Theriogenology. 2001, 55 (3): 733-749. 10.1016/S0093-691X(01)00440-X.

Gunzel-Apel AR, Gunther C, Terhaer P, Bader H: Computer-assisted analysis of motility, velocity and linearity of dog spermatozoa. J of reproduction and fertility Supplement. 1993, 47: 271-278.

Memon MA: Common causes of male dog infertility. Theriogenology. 2007, 68 (3): 322-328. 10.1016/j.theriogenology.2007.04.025.

Schafer-Somi S, Frohlich T, Schwendenwein I: Measurement of alkaline phosphatase in canine seminal plasma–an update. Reprod Domest Anim. 2013, 48 (1): e10-e12. 10.1111/j.1439-0531.2012.02025.x.

Linde-Forsberg C: Achieving canine pregnancy by using frozen or chilled extended semen. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract. 1991, 21 (3): 467-485.

Schafer-Somi S, Aurich C: Use of a new computer-assisted sperm analyzer for the assessment of motility and viability of dog spermatozoa and evaluation of four different semen extenders for predilution. Anim Reprod Sci. 2007, 102 (1–2): 1-13.

Kruger TM, Franken DR, Menkveld R: A self teaching program for strict sperm morphology. 1993, MQ Medical: Bellville, South Africa

WHO: WHO laboratory manual for the examination and processng of human semen. 2010, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 5

Nicholas TJ, Cheng Z, Ventura M, Mealey K, Eichler EE, Akey JM: The genomic architecture of segmental duplications and associated copy number variants in dogs. Genome Res. 2009, 19 (3): 491-499.

Lichter P, Tang CJ, Call K, Hermanson G, Evans GA, Housman D, Ward DC: High-resolution mapping of human chromosome 11 by in situ hybridization with cosmid clones. Science. 1990, 247 (4938): 64-69. 10.1126/science.2294592.

Hristova R, Ko E, Greene C, Rademaker A, Chernos J, Martin R: Chromosome abnormalities in sperm from infertile men with asthenoteratozoospermia. Biol Reprod. 2002, 66 (6): 1781-1783. 10.1095/biolreprod66.6.1781.

Rijsselaere T, Maes D, Hoflack G, de Kruif A, Van Soom A: Effect of body weight, age and breeding history on canine sperm quality parameters measured by the Hamilton-Thorne analyser. Reprod Domest Anim. 2007, 42 (2): 143-148. 10.1111/j.1439-0531.2006.00743.x.

Nicholas TJ, Baker C, Eichler EE, Akey JM: A high-resolution integrated map of copy number polymorphisms within and between breeds of the modern domesticated dog. BMC Genomics. 2011, 12: 414-10.1186/1471-2164-12-414.

Tuttelmann F, Simoni M, Kliesch S, Ledig S, Dworniczak B, Wieacker P, Ropke A: Copy number variants in patients with severe oligozoospermia and Sertoli-cell-only syndrome. PLoS One. 2011, 6 (4): e19426-10.1371/journal.pone.0019426.

Harbuz R, Zouari R, Pierre V, Ben Khelifa M, Kharouf M, Coutton C, Merdassi G, Abada F, Escoffier J, Nikas Y, et al: A recurrent deletion of DPY19L2 causes infertility in man by blocking sperm head elongation and acrosome formation. Am J Hum Genet. 2011, 88 (3): 351-361. 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.02.007.

Fetic S, Yeung CH, Sonntag B, Nieschlag E, Cooper TG: Relationship of cytoplasmic droplets to motility, migration in mucus, and volume regulation of human spermatozoa. J Androl. 2006, 27 (2): 294-301. 10.2164/jandrol.05122.

Pelfrey RJ, Overstreet JW, Lewis EL: Abnormalities of sperm morphology in cases of persistent infertility after vasectomy reversal. Fertil Steril. 1982, 38 (1): 112-114.

Rens W, Yang F, Welch G, Revell S, O’Brien PC, Solanky N, Johnson LA, Ferguson Smith MA: An X-Y paint set and sperm FISH protocol that can be used for validation of cattle sperm separation procedures. Reproduction. 2001, 121 (4): 541-546. 10.1530/rep.0.1210541.

Sarrate Z, Anton E: Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) protocol in human sperm. J Vis Exp. 2009, 1 (31): 1-2.

Kusumi N, Watanabe M, Yamada H, Li SA, Kashiwakura Y, Matsukawa T, Nagai A, Nasu Y, Kumon H, Takei K: Implication of amphiphysin 1 and dynamin 2 in tubulobulbar complex formation and spermatid release. Cell Struct Funct. 2007, 32 (2): 101-113. 10.1247/csf.07024.

Gubbay J, Collignon J, Koopman P, Capel B, Economou A, Munsterberg A, Vivian N, Goodfellow P, Lovell-Badge R: A gene mapping to the sex-determining region of the mouse Y chromosome is a member of a novel family of embryonically expressed genes. Nature. 1990, 346 (6281): 245-250. 10.1038/346245a0.

Foster JW, Dominguez-Steglich MA, Guioli S, Kwok C, Weller PA, Stevanovic M, Weissenbach J, Mansour S, Young ID, Goodfellow PN, et al: Campomelic dysplasia and autosomal sex reversal caused by mutations in an SRY-related gene. Nature. 1994, 372 (6506): 525-530. 10.1038/372525a0.

O’Bryan MK, Takada S, Kennedy CL, Scott G, Harada S, Ray MK, Dai Q, Wilhelm D, de Kretser DM, Eddy EM, et al: Sox8 is a critical regulator of adult Sertoli cell function and male fertility. Dev Biol. 2008, 316 (2): 359-370. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.01.042.

Pastuszak AW, Lamb DJ: The genetics of male fertility–from basic science to clinical evaluation. J Androl. 2012, 33 (6): 1075-1084. 10.2164/jandrol.112.017103.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by a grant “Futuro in ricerca 2010” RBFR103CE3.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

DC carried out the experiments and data analysis, and co-authored the manuscript. NAM carried out data analysis and co-authored the manuscript. LV collected biological material and critically evaluated the manuscript. ACG collected material. MFC managed the BAC collections. FP critically evaluated the manuscript and contributed valuable discussion and statistical analysis. MED advised on data analysis and critically evaluated the manuscript. MV conceived the experiments, carried out experiments and data analysis, and authored the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

12864_2013_7172_MOESM1_ESM.jpeg

Additional file 1: Table S1: Reproductive anamnesis and sperm quality in dogs. Legend. NA: Not available information. VAP: average path velocity (μm/s); VSL: straight-line rectilinear velocity (μm/s); VCL: curvilinear velocity (μm/s); ALH: Amplitude of Lateral Head displacement (μm); BCF: Beat Cross Frequency (Hz); STR: Straightness (%); LIN: Linearity (%). Detection of these features in dog #12 was not possible for its azoospermia condition. (JPEG 272 KB)

12864_2013_7172_MOESM2_ESM.xlsx

Additional file 2: Figure S1: Hamilton-Thorne IVOS 12.3 CASA analyses on 11 sperm samples. Computed LS-MEAN values for VAP, VSL, VCL, ALH, BCV, STR and LIN parameters. Statistical significance analysis was performed with SAS software. a vs b, c vs d: P ≤0.0002. (XLSX 40 KB)

12864_2013_7172_MOESM3_ESM.xlsx

Additional file 3: Table S2: Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization results on lymphocytes from 6 samples with 25 different BACs covering genes of interest for male reproduction and fertility. (XLSX 49 KB)

12864_2013_7172_MOESM4_ESM.xlsx

Additional file 4: Table S3: Results from Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization on sperm cells (S-FISH) carried out on 11 out of 12 samples analyzed on IVOS 12.3. Dog #12 could not be analyzed because of its azoospermia condition. (XLSX 53 KB)

12864_2013_7172_MOESM5_ESM.xlsx

Additional file 5: Table S4: “Sex sorting by FISH” analysis on all the sperm samples available, with numbers of X positive sperm cells among the total cells counted, and respective X percentages in germinal cells population. (XLSX 43 KB)

12864_2013_7172_MOESM6_ESM.xlsx

Additional file 6: Table S5: Genes included in the three BAC probes selected for duplication analysis in sperm cells. Biological processes and molecular functions of each gene were retrieved on The Gene Ontology database (http://amigo.geneontology.org). In bold, genes playing crucial roles in male fertility and reproductive phenotypes; in italic, genes included only partially in the probe. (XLSX 43 KB)

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Cassatella, D., Martino, N.A., Valentini, L. et al. Male infertility and copy number variants (CNVs) in the dog: a two-pronged approach using Computer Assisted Sperm Analysis (CASA) and Fluorescent In Situ Hybridization (FISH). BMC Genomics 14, 921 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2164-14-921

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2164-14-921