Abstract

Background

Few exceptions have been described from strict maternal inheritance of mitochondrial DNA in animals, including sea mussels (Mytilidae), clams (Donacidae, Veneridae and Solenidae) and freshwater mussels (Unionoidae) order. In these bivalves mitochondria and their DNA are transferred through two separate routes. The females inherit only the maternal mitochondrial DNA whereas the males inherit maternal as well as paternal mitochondrial DNA, which is usually present only in gonads and sperm. The mechanism controlling this phenomenon is unclear but leads to the existence of two separate mitochondrial DNA lineages in a single species. The lineages are usually well differentiated: up to 20-50% divergence in nucleotide sequence. Occasionally, a maternal mitochondrial DNA can invade the paternal transmission route, eventually replacing the diverged M-type and lowering the divergence. Such role reversal (masculinization) event has happened recently in the Mytilus population of the Baltic Sea which consists of M. edulis × M. trossulus hybrids, but the functional status of the resulting mitochondrial genome was unknown.

Results

In this paper we sequenced transcripts from one specimen that was identified as male carrying both the female mitochondrial genome and a recently masculinized mitochondrial genome. Additionally, the analysis of the control region has showed that the recently masculinized, recombinant genome, not only has an M-type control region and all coding regions derived from the F-type, but also is transcriptionally active along side the maternally inherited F-type genome. In the comparative analysis, the two genomes exhibit different substitution patterns, typical for the M vs. F genome comparisons. The genetic distances and ratios of non-synonymous substitutions also suggest that one of the genomes is transitioning from the maternal to the paternal inheritance mode, consistent with its recent masculinization.

Conclusion

We have shown, for the first time, that the recently masculinized mitochondrial genome is active and that it accumulates excess of non-synonymous substitutions across its coding sequence. This suggests, that, under certain cytonuclear incompatibility conditions, masculinization may serve to restore the endangered functionality of the paternally inherited genome. This is also another example of a mitochondrial genome in which the recombination in the control region predated its transition from paternal to maternal transmission route.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

In the animal kingdom mitochondria are commonly inherited through the maternal line (SMI – Strict Maternal Inheritance) [1] and their inheritance is clonal. The number of mitochondria within a single spermatozoa is much lower than in an oocyte. In mammals, during fertilization, the sperm mitochondria usually enter the ovum but are are ubiquitinated and enzymatically degraded [2]. It has been shown, that sperm mitochondria apparently do not persist beyond 48 hours after fertilization in female embryos of Mytilus mussel [3, 4] but it is unclear whether they are stochastically lost or actively eliminated thereafter [5]. The mitochondria inheritance system of these bivalves is complicated by the Doubly Uniparental Inheritance (DUI) phenomenon, originally described in Mytilidae [6, 7] but present also in other, distantly related bivalves such as some clams (Veneridae, Donacidae and Solenidae) [8, 9] and the members of Unionoida order (freshwater mussels) [10, 11]. Under DUI, the females are homoplasmic and pass their mitochondrial genome to all their progeny, as in SMI. Males, however, also pass their mtDNA but only to their male progeny. Most work concerning the fate of paternal mtDNA was done in Mytilus. The paternal mtDNA, if present in female tissues, is silent [12], and exists in very low concentration [13]. However, in male zygotes sperm mitochondria aggregate in only one blastomere from which gonadal tissue is shaped during embryo development [3, 14]. Consequently, both genomes are present and expressed in the male germ line and only the paternal genome is present in sperm. Both genomes may also be present in the male somatic tissues, but primarily the F genome is expressed there [15, 16]. The M genome evolves faster than the F genome and accumulates more non-synonymous substitutions. It has been postulated that this may be explained by either relaxed or even positive selection [17–20]. The mechanism of DUI still remains unclear, although theoretical models have been developed explaining most of the observed DUI features [21, 22].

Members of the Mytilus edulis species complex tend to hybridize in areas of sympatry. Such a hybridyzation zone has been described in the vicinity of the Baltic Sea. The species inhabiting the Baltic Sea was long considered to be M. edulis. However, allozyme data have changed the paradigm suggesting that the Baltic Sea population should be considered M. trossulus, hybridising with North Sea M. edulis in Danish Straits [23]. When more molecular markers were taken into account, it turned out that the whole Baltic population must be considered hybrid, with mixed nuclear background [24, 25] and strong, unidirectional introgression of M. edulis mtDNA, leading to the complete replacement of the M. trossulus mtDNA [25, 26]. Furthermore, the highly divergent (typically 20% in M. edulis) M genome is present at low frequencies only and is replaced by far less divergent (up to 4%) genomes of F origin [27–29]. These genomes have mosaic structures, with a part of the control region (CR) derived from the typical, highly divergent M genome and the coding sequences derived from the typical F genome [28, 30]. This apparent role reversal of the F genome invading the paternal transmission route has been called masculinization [21, 31] and was reported also in M. galloprovincialis from the Black Sea [32, 33]. These cases are, in the phylogenetic sense, quite recent. In other DUI animals the divergence between the two lineages is much higher, although if the DUI phenomenon is an ancient trait, then the role-reversals must have occasionally happened because the last common ancestor of M and F lineages is usually much younger than DUI itself [11, 22]. The recentness of this process in the Baltic Mytilus gave an opportunity to study it in more detail. It has been postulated that CR sequences of the M origin are somehow involved in the paternal inheritance, and hence the CR recombination would be prerequisite for masculinization [30, 32]. The discovery that in American M. trossulus the typical F genome has mosaic CR, despite not being masculinized [19, 34], has somewhat lessened the strength of the argument. It has also raised the question how the masculinized genome can be recognized, without experimentally following its transmission route.

In this paper, we report divergence analysis of a co-expressed F and recently masculinized genome from a single male M. trossulus from Baltic Sea (Gulf of Gdańsk), for the first time applying EST (Expressed Sequence Tags) analysis to that type of genomes.

Methods

Collection of samples

Mussels were collected from the Gulf of Gdańsk (Southern Baltic Sea) at the end of April 2007. For Mytilus sp. it is the reproduction season and the adult individuals are full of ripe gametes just before spawning. The sex of each specimen was determined by microscopic examination of both sides, to exclude hermaphrodite individuals [13]. Overall 30 ripe male individuals were selected. Gill and mantle tissue samples of each individual were stored at -70°C.

DNA isolation and screening

The first step in identifying specimens bearing recombinant, presumably masculinized genomes among morphologically identified males, was to extract total DNA using the CTAB method [35]. The control region (CR) fragment was then amplified using selective PCR primers developed in our laboratory [28]. First amplification was performed with AB32-AB16 primers. They have been used to detect rearranged genomes throughout the European range of Mytilus and do not amplify from the regular – non recombinant genomes [33]. The expected proportion [28] of examined males (10 individuals) gave a positive signal in this PCR. Then the long PCR was performed with MF12S and MFCO2 primers flanking the CR [33], for the selected 10 individuals. The length of this PCR product is indicative of the type of amplified genome: for the typical M genome, the PCR product is about 4600 bp long, whereas for typical F genome it is almost 4900 bp long. In recombinant genomes, the PCR products are longer; the difference depends on the number of 950 bp long repeat units present [28] and hence the number of repeats can be roughly estimated simply by comparing the lengths of the PCR products (Additional file 1). One of the individuals was selected for further analysis at random. To determine the sequence of the CR, the PCR products of the second amplification were ligated into the pUC19 vector (SmaI digested) and transformed into chemocompetent Escherichia coli DH5α host cells. Recombinant plasmids were isolated using the Plasmid Mini kit from A&A Biotechnology and then sequenced by Macrogene Inc. in Korea (Sanger method) from both ends.

Preparation of cDNA library

For further analysis, central part of the mantle tissue containing gonads from one male individual bearing the recombinant mitochondrial genome was chosen. Total RNA was purified with GenElute™ Mammalian Total RNA Miniprep Kit (#RTN70, Sigma-Aldrich) including DNaseI (#EN0521, Fermentas) “on column” digestion step. Tissue was digested in the lysis buffer with proteinase K (#P2308, Sigma-Aldrich), 2-mercaptoethanol (#M3148, Sigma-Aldrich) and incubated for 30 minutes at 55°C. RNA was eluted twice.

A cDNA library was created in cooperation with the Max Planck Institute in Berlin-Dahlem, Germany. The library was created using CloneMinerTM cDNA Library Construction Kit from Invitrogen. The cloning into an E. coli Gateway System and subsequent clone sequencing (Sanger method) was performed semiautomatically at the Max Planck Institute. The bioinformatic analysis of obtained EST data was performed at the Institute of Oceanology, Polish Academy of Sciences, Sopot.

Bioinformatic analysis

Primary sequence reads were filtered using pregap4 software from the Staden Package [36]. Low quality sequences (Phred quality value <20), cloning vectors, primers as well as the polyadenylation tails, were automatically masked. To separate the mitochondrial transcripts from the nuclear, all sequences were compared by the estwisedb software (wise2 package) [37] to HMM profiles, which were built for Mytilus sp. mitochondrial genes using HMMER [38]. The positively identified reads were clustered in gap4 [36], and the resulting mitochondrial transcripts (mtEST) were BLASTed [39, 40] against a local database of reference mtDNAs (GenBank and own data, Table 1). This second filtering step allowed identification of two reference genomes for further comparative analyses: F-BMt [28] and RF-Mg [33], both with less than 5% divergence from the mtESTs.

Estwisedb selected transcripts were mapped (assembled) onto the corresponding mtDNA reference genomes (Additional file 2A), in gap4. Manual screening of each assembly did not reveal any cloning or PCR anomalies (Additional file 2B). The mtEST consensus sequences were extracted for each gene separately in gap4 (Additional file 2C), trimmed to coding open reading frame (ORF) (Additional file 2D), and concatenated in the same order as the genes in mtDNA (Additional file 2E). There was no sequence polymorphism (differences between high quality reads) within any of the contigs. All individual consensus sequences were deposited in GenBank (Accession numbers: KF220383–KF220405). To broaden the scope of the comparative analysis, three other genomes were used: F-Me [41], F-Mg [42] and M-BMt [26] (Table 1). The F-Me and F-Mg were potential outgroups rooting the clades containing mtEST, whereas the M-BMt was an outgroup for all F – like genomes compared in this paper. From all genomes, coding sequences were extracted, trimmed to the extent represented by mtESTs and concatenated (Additional file 2). All seven concatamers were then aligned in MEGA5 [44]. The nucleotide sequences were converted into amino acid sequences using the invertebrate mitochondrial genetic code (translation according to Codon Usage table five, NCBI) to eliminate the risk of not-in-frame gap insertions (MEGA5 ClustalW protein alignment under the default settings, with PAM weight matrix). For further analysis nucleotide sequences arranged by the amino acid alignment with all the gaps, stop codons and missing data removed were used. Nucleotide and amino acid divergence was determined in pairwise comparisons between all concatamers. Pairwise distance (Tamura-Nei model) as well as the disparity index (ID) test were calculated in MEGA5 [44] under the default settings. For the ID test, a statistical Monte Carlo test (10000 replicates) was used to estimate the P-value.

The Ka/Ks ratios were calculated using KaKs_Calculator2.0 [45]. Input set consisted of all possible pairs of the seven concatamers. The computation was performed with the GY model (modified Hasegawa-Kishino-Yano) [46] of substitutions and assuming invertebrate mitochondrial genetic code. The model was selected using HyPhy1.0 [47] with default parameters, 4 rate categories (for both tests: Hierarchical and AIC) and P < 0.05. Also, the sliding window data analysis was performed for paired sequences with HyPhy1.0 (GTR model and 3 × 3 window setting).

For calculation of maximum likelihood (ML) tree, all seven concatamers were used. The tree was calculated using MrBayes-3.1.2 [48]. The M-BMt sequence was set as an outgroup. The analysis consisted of 4 runs with 4 chains. For each run three chains were heated and one was a cold chain. Each run consisted of 25 mln generations and sampling frequency was set at 10000 generations. This procedure was sufficient to achieve effective sample size (ESS) of at least 1900. The substitution model was set as a General Time Reversible model with gamma-distributed rate variation across sites and a proportion of invariable sites (GTR + Γ + I model, nst = 6). The 50% majority-rule Bayesian inference tree was derived from obtained data with the burnin of 25%. Afterwards, the resulting tree was drawn in FigTree 1.4 [49]. The posterior probability values are included as an indication of the support for key nodes.

All research described in the manuscript has been performed in compliance with the ethical guidelines regarding the experiments on animals.

Results

In 10 morphologically identified males, CR amplification with AB32 and AB16 primers gave homogenous products with the length of about 950 bp. An individual bearing the relatively short recombinant genome was selected for further analysis (MF12S-MFCO2 product length of approx. 6850 bp, indicative of the presence of two repeats). The sequencing of the clone library and in silico analysis confirmed the presence of two AB32-AB16 repeats in the CR. Sequence comparison confirmed that the genome belongs to the 11a/15 or mf2 haplogroup described previously [28, 33], mainly from the Baltic and Mediterranean Sea: the sequenced parts of the CR were identical to some of the previously described haplotypes from this haplogroup (data not shown).

The sequenced cDNA library from the selected specimen consisted of over 2300 ESTs and about 10.5% of them were identified as mtEST. They were clustered into 24 contigs. Each contig was assigned to one of the two sets of ESTs (presumably transcribed from two genomes), based on its distances from the two reference genomes (Table 2). The genome represented by 202 ESTs in 13 contigs closer to the RF-Mg genome was called EL (large set of ESTs), whereas the second genome, containing 54 ESTs in 11 contigs was called ES (small set of ESTs). Figure 1A is a schematic map of those two EST sets. Most genes were represented in both sets. The overall coding sequence coverage was 91.5% for EL and 66.6% for ES (Figure 1B). To avoid the bias associated with this difference, both sets and all reference sequences were trimmed to the longest common coverage and aligned. The alignment was 7515 bp (2505 amino acids) long and represented 64.1% of the mitochondrial coding sequence from 11 out of 13 mitochondrial protein coding genes (cytb and nd4L were excluded because they were not present in the ES). There were no transcripts covering the recently described ORF in the control region [50] or the 16S rRNA subunit and there was only a single transcript for the 12S rRNA subunit (data not shown). Some genes with possible alternative polyadenylation sites and a few sequences spanning two adjacent genes have been identified but their presence did not influence the consensus generation.

Transcript mapping. Figure (A) The two mtEST sets (EL and ES) mapped on a hypothetical mitochondrial genome. Each green or brown rectangle represents a single contig. The numbers indicate the number of ESTs building each contig. Curved lines indicate the presence and positions of the polyadenine tails. Alternative polyadenylation sites and transcripts spanning two genes are retained. (B) The position of consensus mtESTs against a Mytilus circular mitochondrial genome. There are no sequence differences between apparently alternatively polyadenylated transcripts. Note that these mtESTs were further trimmed to the common coverage before performing comparative analyses.

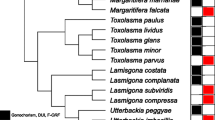

The phylogenetic tree based on the aligned set of representative gene fragments was inferred by the Bayesian approach (Figure 2). The relationships between all seven genomes were resolved with good support for all bipartitions. It confirmed the placement of both EL and ES genomes close to the other F-like genomes and the closest relationship of both genomes with the respective reference genomes (F-BMt and RF-Mg). This was confirmed also by the high resolution phylogeny involving more unpublished complete mitochondrial genomes (Additional file 3).

Bayesian inference, majority-rule tree for mitochondrial transcripts of representatives from European Mytilus family. Phylogenetic tree based on the 7515 bp long alignment of concatenated coding sequence fragments from the mitochondrial genomes expressed in the mantle of a male individual of Baltic M. trossulus with the reference genomes listed in Table 1. Branch support is given as posterior probability (Bayesian inference).

Pairwise comparison of distances between all genomes (Table 3) showed an overall uniform pattern of synonymous and non-synonymous substitutions across all comparisons. This was in agreement with the disparity index (ID) test showing mostly homogenous substitution pattern, with only the outgroup M genome (M-BMt) exhibiting significant differences (Additional file 4). The only exception was the higher Ka/Ks ratio in EL:RF-Mg comparison (Table 3). It suggested elevation of the non-synonymous substitution rate along the recent history of the EL genome. For similarly distant pairs of genomes involving the ES genome (ea. the ES:F-Me comparison), the Ks values were similar but there were three times more non-synonymous substitutions in the EL:RF-Mg comparison. This seems to be representative for the paternally inherited genomes: if the two M genomes from M. galloprovincialis (M1-Mg and M2-Mg, Table 1) were compared in a similar way, the obtained Ka/Ks ratio was very similar (118.6 × 10-3). The sliding window, codon-by-codon analysis (Figure 3) showed that the sites responsible for this effect were spread along the whole alignment, intermixed with the numerous codons showing synonymous substitution bias.

Sliding window analysis of selective pressure. Each codon was evaluated for its substitution patten. Negative values indicate purifying selection, positive values mark non-synonymous sites. Each of the expressed genomes was compared with its closest relative. Concatenated alignment was used in the analysis, gene boundaries are marked with thin vertical lines and clearly labeled.

Discussion

We have shown co-expression of two moderately divergent mitochondrial genomes in the mantle tissue of a male M. trossulus from the Baltic Sea. Since the mantle consists of both generative and somatic tissues we expect one of the genomes to be the typical F genome, in line with the observed tissue-specific patterns of expression reported recently for the congeneric M. galloprovincialis[16]. Based on the comparative analysis we can conclude that the genome expressing the ES set of transcripts must be the typical F genome of this individual. There were fewer ES than EL transcripts in the EST library suggesting that the sample may be enriched for the tissue preferentially expressing the second genome. Our main focus was on this second genome, represented by the EL transcripts.

Is the genome functional?

It is expressed, all mitochondrial protein coding gene transcripts are present and all the transcripts contain undisturbed ORFs. Moreover, they are typically polyadenylated near the ends of each coding sequence, although in the case of nd4L - nd5 - nd6 as well as atp8 – cox1 regions the presence of polycistronic transcripts cannot be excluded. Similar features have been reported for M. galloprovincialis mitochondrial transcripts recently [51]. Few sequences either did not contain the polyA sequence - simply because the sequencing did not reach it as only the ends of clones are sequenced - or contained it in unexpected places. There were two such cases in nd4 and one in nd5 sets. These can be viewed as cloning artifacts: they could have arisen either by mispriming from a particularly A-rich mitochondrial region during the first strand synthesis. They could have also be obtained as a result of attaching the polyA fragment to a partially degraded transcript at the ligation step during cloning. Long homopolymeric A or T DNA fragments are known to be particularly fragile [52], hence this interpretation is possible. Regardless of the origin, these sequences had no influence on the consensus calling – after removal of the terminal polyA they did not differ from the other transcripts mapped at the same mitochondrial region. Likewise the potential alternative polyadenylation sites observed may be artifacts of similar origin and without any consequences for the consensus. The lack of 16S sequences in our EST library may be moderately surprising, knowing that these transcripts are typically abundant in 454 transcriptome libraries [53], but the cloning procedure used during EST library preparation differs significantly from the one used in 454 sequencing. Apparently it is far easier for abundant sequences without polyA tail to ”leak-through” in 454 libraries [54]. We have found a single 12S transcript which apparently was polyadenylated. This is not surprising as polyadenylation of 12S transcripts has been reported for human mitochondria [55]. We can conclude that the EL genome is most likely functional.

Is the genome masculinized?

To conclude that a mitochondrial genome is masculinized it should ideally be detected in sperm and in the male offspring. This is rarely possible for various technical reasons. Usually the very presence of a genome in highly purified sperm can be viewed as an evidence that this is a male-transmitted genome [32]. The other approach is to follow its distribution among animals differing in gender [29]. Both approaches can be combined to some degree, allowing the use of poorer quality sperm [28]. This approach was initially received with reservations [56], the need to establish the true transmission route of these genomes was stressed. The EL genome detected here clearly belongs to one of the haplogroups described by [28], based on the identity of sequenced CR fragments. On the other hand, the closest reference genome (RF-Mg) was isolated from a female M. galloprovincialis individual and therefore cannot be considered masculinized [33]. Further arguments supporting the masculinized status of the EL genome include its very expression in male generative tissues. All experimental and model approaches to DUI agree that the paternally transmitted genome should be present and expressed there [3, 4, 13, 16, 22]. The second argument is associated with the observed pattern of substitutions: the EL genome accumulated more non-synonymous substitutions than expected in the phylogenetic context. This is characteristic for a paternally inherited genome [17, 21] and is not seen in the context of the second, ES genome. Therefore the alternative hypotheses assuming that the EL genome is not masculinized can be dismissed.

What is the extent of recombination in the ELgenome?

The presence of mitochondrial genomes with mosaic CR sequences in the sperm of Baltic M. trossulus[28, 30] strongly implied that these were masculinized genomes and that a reorganization of the CR involving the acquisition of sequences from the CR of the M genome was necessary for masculinization [22]. Since the CR of the EL genome falls into this category it can be viewed as another case of a genome in which masculinization and recombination within the CR are linked. However, the confinement of the M-like sequences to the CR is important in the context of the original hypothesis. It remained possible that other parts of these molecules might have also been of type M [32]. This reservation is particularly true in the context of studies reporting recombination between different mitochondrial genomes outside the CR [57, 58]. Here we show no ambiguity in the assignment of all transcripts to their genomes. In particular no M-like transcripts have been found. Therefore it is very unlikely that any other parts of the EL genome are of M origin or that any products of potential recombination between EL and ES genomes are expressed. We can safely conclude that there was no physiologically important recombination outside the CR: no products of such recombination events were expressed at levels comparable with any of the parental sequences. The relationship between recombination and masculinization in the case of EL genome can be further traced in the phylogenetic context. The closest reference genome (RM-Mg) does have a mosaic CR but there are no other reasons to consider this genome masculinized: it was localized in female tissues and its substitution pattern do not indicate the accelerated accumulation of non-synonymous mutations. Therefore we can parsimoniously assume that a single recombination event within the phylogenetic lineage leading to the EL genome preceded its masculinization, the latter happening only very recently, possibly within a short period of the Baltic Sea existence. The mitochondrial dynamics of the Baltic Sea Mytilus population seems to be confined to this period [26].

What is the driving force for the masculinization of mitochondrial genomes in Baltic population?

The most obvious explanation, that M genomes must occasionally be replaced because they degenerate, do not hold. The accumulation of potentially deleterious mutations in M-type genomes does not seem to be a problem for other DUI species. It has been shown that the system can be stable (ea. without any masculinization events) for hundreds of millions of years, as in unionidean mussels [10], moreover most Mytilus populations do not show masculinized genomes [33]. What is unique to the Baltic M. trossulus population is its nuclear background. Relatively high frequency of M. edulis alleles coupled with the complete replacement of the mitochondrial genomes creates a space for potential cytonuclear incompatibilities. They could lead to mitochondrial genome instabilities, both structural and functional. In fact, the CR length variants [59], recombination [30] and masculinization [27] can be viewed as manifestations of this instability. Under the mixed nuclear background the divergence threshold required to retain functionality of the mitochondrial genome may have abruptly lowered, rendering the divergent M genome less functional and therefore favoring masculinization. Studies reporting functional deficiencies of sperm carrying masculinized genomes in American M. edulis[60, 61] seem to support such hypothesis. The reported fitness deficiency happened in the context of the presence of apparently native M. trossulus F genomes in M. edulis individuals. These genomes were originally interpreted as M. edulis masculinized genomes, but it has been shown that they are more likely typical F genomes of M. trossulus[19]. In this context it was most likely the cytonuclear incompatibility rather than masculinization that caused the fitness deficiency [19]. Whatever the reason, it clearly happened also in the context of interspecies hybridisation showing that under this conditions sperm mitochondria may become less fit.

Can transcriptomics help to detect DUI?

There are three major F haplogroups in European populations of Mytilus spp. [18]. It has been noted previously, that a single lineage of genomes with mosaic CR structures has been derived from each of the haplogroups [28, 33]. Two of the three recombinant lineages were associated with M. galloprovincialis. In the Baltic Sea, apparently very recent masculinization involved genomes from all three clades [28]. This is the reason why some of them are quite divergent – most of the divergence did not accumulate after the masculinization. The <4% divergence between the two expressed genomes observed in this study (EL and ES) was high enough to unambiguously identify all transcripts. This shows the utility of transcriptomics in analysing mitochondrial divergence patterns. This methodology can be applied to other species as well, potentially overcoming the problems with the detection of DUI outlined by [9]: by analysing transcripts from male gonads one should be able to detect either single set of transcripts (for non-DUI species) or two sets of transcripts (indicating potential DUI species). We have shown that the sets can be distinguished even if the divergence is small. It should be even easier if the divergence is larger.

Conclusions

We have shown that two mitochondrial genomes are co-expressed in the mantle of a male Mytilus mussel from the Baltic Sea. Both genomes are functional and one of them is recently masculinized. The masculinized genome contains a mosaic CR. The recombination was confined to the CR of its ancestor and preceded masculinization. These conclusions must be stated as tentative at present, given the sample size of one male. Nevertheless, the proposed methodology demonstrates the usefulness of transcriptome analysis in studying DUI.

Abbreviations

- Bp:

-

Base pairs

- CR:

-

Control region

- DUI:

-

Doubly uniparental inheritance

- F genome:

-

Female type genome

- mt:

-

Mitochondria/mitochondrial

- mtDNA:

-

Mitochondrial DNA

- mtEST:

-

Mitochondrial Expressed Sequence Tag

- M genome:

-

Male type genome

- ML:

-

Maximum likelihood

- ORF:

-

Open reading frame

- PCR:

-

Polymerase chain reaction

- poly(A):

-

Polyadenylation

- R genome:

-

Recombinant F genome

- SMI:

-

Strict maternal inheritance

- sq:

-

Sequences.

References

Birky CW: The inheritance of genes in mitochondria and chloroplasts: laws, mechanisms, and models. Annu Rev Genet. 2001, 35: 125-148. 10.1146/annurev.genet.35.102401.090231.

Sutovsky P, Moreno RD, Ramalho-Santos J, Dominko T, Simerly C, Schatten G: Development: ubiquitin tag for sperm mitochondria. Nature. 1999, 402: 371-372. 10.1038/46466.

Cao L, Kenchington E, Zouros E: Differential segregation patterns of sperm mitochondria in embryos of the Blue Mussel (Mytilus edulis). Genetics. 2004, 166: 883-894. 10.1534/genetics.166.2.883.

Obata M, Komaru A: Specific location of sperm mitochondria in mussel Mytilus galloprovincialis zygotes stained by MitoTracker. Dev Growth Differ. 2005, 47: 255-263. 10.1111/j.1440-169X.2005.00801.x.

Sutherland B, Stewart D, Kenchington ER, Zouros E: The fate of paternal mitochondrial DNA in developing female mussels, Mytilus edulis: implications for the mechanism of doubly uniparental inheritance of mitochondrial DNA. Genetics. 1998, 148: 341-347.

Zouros E, Ball AO, Saavedra C, Freeman KR: Mitochondrial DNA inheritance. Nature. 1994, 368: 818-10.1038/368818a0.

Skibinski DOF, Gallagher C, Beynon CM: Mitochondrial DNA inheritance. Nature. 1994, 368: 817-818.

Passamonti M, Scali V: Gender-associated mitochondrial DNA heteroplasmy in the venerid clam Tapes philippinarum (Mollusca Bivalvia). Curr Genet. 2001, 39: 117-124. 10.1007/s002940100188.

Theologidis I, Fodelianakis S, Gaspar MB, Zouros E: Doubly uniparental inheritance (DUI) of mitochondrial DNA in Donax trunculus (Bivalvia: Donacidae) and the problem of its sporadic detection in Bivalvia. Evolution. 2008, 62: 959-970. 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2008.00329.x.

Hoeh WR, Stewart DT, Guttman SI: High fidelity of mitochondrial genome transmission under the doubly uniparental mode of inheritance in freshwater mussels (Bivalvia: Unionoidea). Evolution. 2002, 56: 2252-2261.

Doucet-Beaupré H, Breton S, Chapman EG, Blier PU, Bogan AE, Stewart DT, Hoeh WR: Mitochondrial phylogenomics of the Bivalvia (Mollusca): searching for the origin and mitogenomic correlates of doubly uniparental inheritance of mtDNA. BMC Evol Biol. 2010, 10: 50-10.1186/1471-2148-10-50.

Dalziel AC, Stewart DT: Tissue-specific expression of male-transmitted mitochondrial DNA and its implications for rates of molecular evolution in Mytilus mussels (Bivalvia: Mytilidae). Genome NRC Canada. 2002, 45: 348-355.

Garrido-Ramos MA, Stewart DT, Sutherland BW, Zouros E: The distribution of male-transmitted and female-transmitted mitochondrial types in somatic tissues of blue mussels: Implications for the operation of doubly uniparental inheritance of mitochondrial DNA. Genome NRC Canada. 1998, 41: 818-824.

Cogswell AT, Kenchington ELR, Zouros E: Segregation of sperm mitochondria in two- and four-cell embryos of the blue mussel Mytilus edulis: Implications for the mechanism of doubly uniparental inheritance of mitochondrial DNA. Genome NRC. 2006, 49: 799-807. 10.1139/G06-036.

Sano N, Obata M, Komaru A: Quantitation of the male and female types of mitochondrial DNA in a blue mussel, Mytilus galloprovincialis, using real-time polymerase chain reaction assay. Dev Growth Differ. 2007, 49: 67-72. 10.1111/j.1440-169X.2007.00904.x.

Obata M, Sano N, Komaru A: Different transcriptional ratios of male and female transmitted mitochondrial DNA and tissue-specific expression patterns in the blue mussel, Mytilus galloprovincialis. Dev Growth Differ. 2011, 53: 878-886. 10.1111/j.1440-169X.2011.01294.x.

Stewart DT, Kenchington ER, Singh RK, Zouros E: Degree of selective constraint as an explanation of the different rates of evolution of gender-specific mitochondrial DNA lineages in the mussel Mytilus. Genetics. 1996, 143: 1349-1357.

Śmietanka B, Burzyński A, Wenne R: Molecular population genetics of male and female mitochondrial genomes in European mussels Mytilus. Mar Biol. 2009, 156: 913-925. 10.1007/s00227-009-1137-x.

Śmietanka B, Burzyński A, Wenne R: Comparative genomics of marine mussels (Mytilus spp.) gender associated mtDNA: rapidly evolving atp8. J Mol Evol. 2010, 71: 385-400. 10.1007/s00239-010-9393-4.

Śmietanka B, Zbawicka M, Sańko T, Wenne R, Burzyński A: Molecular population genetics of male and female mitochondrial genomes in subarctic Mytilus trossulus. Mar Biol. 2013, 160: 1709-1721. 10.1007/s00227-013-2223-7.

Stewart DT, Breton S, Blier PU, Hoeh WR: Masculinization events and doubly uniparental inheritance of mitochondrial DNA: a model for understanding the evolutionary dynamics of gender-associated mtDNA in mussels. Evolutionary Biology. Edited by: Pontarotti P. 2009, 163-173.

Zouros E: Biparental inheritance through uniparental transmission: the doubly uniparental inheritance (DUI) of Mitochondrial DNA. Evol Biol. 2013, 40: 1-31. 10.1007/s11692-012-9195-2.

Väinölä R, Hvilsom M: Genetic divergence and a hybrid zone between Baltic and North Sea Mytilus populations (Mytilidae: Mollusca). Biol J Linn Soc. 1991, 43: 127-148. 10.1111/j.1095-8312.1991.tb00589.x.

Riginos C, Sukhdeo K, Cunningham CW: Evidence for selection at multiple allozyme loci across a mussel hybrid zone. Mol Biol Evol. 2002, 19: 347-351. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a004088.

Kijewski TK, Zbawicka M, Väinölä R, Wenne R: Introgression and mitochondrial DNA heteroplasmy in the Baltic populations of mussels Mytilus trossulus and M. edulis. Mar Biol. 2006, 149: 1373-1385.

Zbawicka M, Burzyński A, Wenne R: Complete sequences of mitochondrial genomes from the Baltic mussel Mytilus trossulus. Gene. 2007, 406: 191-198. 10.1016/j.gene.2007.10.003.

Skibinski DOF, Wenne R: Mitochondrial DNA heteroplasmy in European populations of the mussels Mytilus trossulus. Mar Biol. 1995, 122: 619-624. 10.1007/BF00350683.

Burzyński A, Zbawicka M, Skibinski DOF, Wenne R: Doubly uniparental inheritance is associated with high polymorphism for rearranged and recombinant control region haplotypes in Baltic Mytilus trossulus. Genetics. 2006, 174: 1081-1094. 10.1534/genetics.106.063180.

Quesada H, Stuckas H, Skibinski DOF: Heteroplasmy suggests paternal co-transmission of multiple genomes and pervasive reversion of maternally into paternally transmitted genomes of mussel (Mytilus) mitochondrial DNA. J Mol Evol. 2003, 57 (Suppl 1): S138-S147.

Burzyński A, Zbawicka M, Skibinski DOF, Wenne R: Evidence for recombination of mtDNA in the marine mussel Mytilus trossulus from the Baltic. Mol Biol Evol. 2003, 20: 388-392. 10.1093/molbev/msg058.

Hoeh WR, Stewart DT, Saavedra C, Sutherland BW, Zouros E: Phylogenetic evidence for role-reversals of gender-associated mitochondrial DNA in Mytilus (Bivalvia: Mytilidae). Mol Biol Evol. 1997, 14: 959-967. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a025839.

Venetis C, Theologidis I, Zouros E, Rodakis GC: A mitochondrial genome with a reversed transmission route in the Mediterranean mussel Mytilus galloprovincialis. Gene. 2007, 406: 79-90. 10.1016/j.gene.2007.06.001.

Filipowicz M, Burzyński A, Śmietanka B, Wenne R: Recombination in Mitochondrial DNA of European Mussels Mytilus. J Mol Evol. 2008, 67: 377-388. 10.1007/s00239-008-9157-6.

Rawson PD: Nonhomologous recombination between the large unassigned region of the male and female mitochondrial genomes in the Mussel, Mytilus trossulus. J Mol Evol. 2005, 61: 717-732. 10.1007/s00239-004-0035-6.

Hoarau G, Rijnsdorp AD, Van der Veer HW, Stam WT, Olsen JL: Population structure of plaice (Pleuronectes platessa L.) in northern Europe: microsatellites revealed large-scale spatial and temporal homogeneity. Mol Ecol. 2002, 11: 1165-1176. 10.1046/j.1365-294X.2002.01515.x.

Bonfield JK, Smith KF, Staden R: A new DNA sequence assembly program. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995, 23: 4992-4999. 10.1093/nar/23.24.4992.

Birney E, Clamp M, Durbin R: Genewise and Genomewise. Genome Res. 2004, 14: 988-995. 10.1101/gr.1865504.

Eddy SR: Profile hidden Markov models. Bioinformatics. 1998, 14: 755-763. 10.1093/bioinformatics/14.9.755.

Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schäffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman DJ: Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997, 25: 3389-3402. 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389.

Camacho C, Coulouris G, Avagyan V, Ma N, Papadopoulos J, Bealer K, Madden TL: BLAST+: architecture and applications. BMC Bioinforma. 2008, 10: 421-

Boore JL, Medina M, Rosenberg LA: Complete Sequences of the highly rearranged molluscan mitochondrial genomes of the Scaphopod Graptacme eborea and the Bivalve Mytilus edulis. Mol Biol Evol. 2004, 21: 1492-1503. 10.1093/molbev/msh090.

Burzyński A, Śmietanka B: Is interlineage recombination responsible for low divergence of nad3 in Mytilus galloprovincialis?. Mol Biol Evol. 2009, 26: 1441-1445. 10.1093/molbev/msp085.

Mizi A, Zouros E, Moschonas N, Rodakis GC: The complete maternal and paternal mitochondrial genomes of the Mediterranean mussel Mytilus galloprovincialis: implications for the doubly uniparental inheritance mode of mtDNA. Mol Biol Evol. 2005, 22: 952-967. 10.1093/molbev/msi079.

Tamura K, Peterson D, Peterson N, Stecher G, Nei M, Kumar S: MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol Biol Evol. 2011, 28: 2731-2739. 10.1093/molbev/msr121.

Zhang Z, Li J, Zhao X, Wang J, Wong GK, Yu J: KaKs_Calculator: calculating Ka and Ks through model selection and model averaging. Gen Proteo Bioinforma. 2006, 4: 259-263. 10.1016/S1672-0229(07)60007-2.

Goldman N, Yang Z: A codon-based model of nucleotide substitution for protein-coding DNA sequences. Mol Biol Evol. 1994, 11: 725-736.

Pond SLK, Frost SDW, Muse SV: HyPhy: hypothesis testing using phylogenies. Bioinformatics. 2005, 21: 676-679. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti079.

Ronquist F, Huelsenbeck JP: MrBayes 3: bayesian phylogenetic inference under mixed models. Bioinformatics. 2003, 19: 1572-1574. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg180.

Rambaut A: FigTree, A Graphical Viewer of Phylogenetic Trees. 2009, Institute of Evolutionary Biology, University of Edinburgh

Breton S, Ghiselli F, Passamonti M, Milani L, Stewart DT, Hoeh WR: Evidence for a fourteenth mtDNA-encoded protein in the female-transmitted mtDNA of marine Mussels (Bivalvia: Mytilidae). PLoS ONE. 2011, 6: e19365-10.1371/journal.pone.0019365.

Chatzoglou E, Kyriakou E, Zouros E, Rodakis GC: The mRNAs of maternally and paternally inherited mtDNAs of the mussel Mytilus galloprovincialis: start/end points and polycistronic transcripts. Gene. 2013, 520: 156-165. 10.1016/j.gene.2013.02.019.

Wallace DW, Kay JE: Stability of polyadenylated mRNA in pig lymphocytes. Biosci Rep. 1981, 1: 539-545. 10.1007/BF01116302.

Craft JA, Gilbert JA, Temperton B, Dempsey KE, Ashelford K, Tiwari B, Hutchinson TH, Chipman JK: Pyrosequencing of Mytilus galloprovincialis cDNAs: tissue-specific expression patterns. PLoS ONE. 2010, 5: e8875-10.1371/journal.pone.0008875.

Voelkerding VK, Dames SA, Durtschi JD: Next-generation sequencing: from basic research to diagnostics. Clin Chem. 2009, 55: 641-658. 10.1373/clinchem.2008.112789.

Slomovic S, Laufer D, Geiger D, Schuster G: Polyadenylation of ribosomal RNA in human cells. Nucleic Acid Res. 2006, 34: 2966-2975. 10.1093/nar/gkl357.

Cao L, Ort BS, Mizi A, Pogson G, Kenchington E, Zouros E, Rodakis GC: The control region of maternally and paternally inherited mitochondrial genomes of three species of the sea mussel genus Mytilus. Genetics. 2009, 181: 1045-1056. 10.1534/genetics.108.093229.

Ladoukakis ED, Zouros E: Direct evidence for homologous recombination in mussel (Mytilus galloprovincialis) mitochondrial DNA. Mol Biol Evol. 2001, 18: 1168-1175. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a003904.

Ladoukakis ED, Theologidis I, Rodakis GC, Zouros E: Homologous recombination between highly diverged mitochondrial sequences: examples from maternally and paternally transmitted genomes. Mol Biol Evol. 2011, 28: 1847-1859. 10.1093/molbev/msr007.

Zbawicka M, Wenne R, Skibinski D: Mitochondrial DNA variation in populations of the mussel Mytilus trossulus from the Southern Baltic. Hydrobiologia. 2003, 499: 1-12. 10.1023/A:1026356603105.

Jha M, Côté J, Hoeh WR, Blier PU, Stewart DT: Sperm motility in Mytilus edulis in relation to mitochondrial DNA polymorphisms: implications for the evolution of doubly uniparental inheritance in bivalves. Evolution. 2008, 62: 99-106.

Sophie B, Stewart DT, Blier PU: Role-reversal of gender-associated mitochondrial DNA affects mitochondrial function in Mytilus edulis (Bivalvia: Mytilidae). J Exp Zool. 2009, 312: 108-117.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by a Technology Platforms Access Grant within the EC 6th FP Marine Genomics Europe Network of Excellence and by Polish National Science Centre grant UMO-2011/01/N/NZ2/02977 to TJS. AB was supported by NSC grant UMO-2012/07/B/NZ2/01991.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

TJS was the main researcher, performed specimen identification, DNA and RNA isolation, PCR, cloning, sequence assembly, and analysis, prepared the draft of the manuscript and all figures. AB designed the experiments, participated in the sequence analysis and assembly, edited the manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

12863_2013_1216_MOESM1_ESM.png

Additional file 1: Primer binding map for Control Region identification. A large fragment of the Control Region (CR) with flanking sequences was amplified with MF12S – MFCO2 primers spanning the region from s-rRNA to cox2. The presence of duplicated fragments was detected by amplification of the fragment between primers AB32 –AB16.These duplications contain M – derived fragments and are often present in masculinized genomes of European Mytilus. Blue, vertical lines indicate tRNA genes. (PNG 10 KB)

12863_2013_1216_MOESM2_ESM.png

Additional file 2: EST consensus extraction scheme. (A) All mtESTs were identified by BLAST (B) mapped on the reference genome (C) Stop codons, poli(A) tails and indels were removed and a consensus sequence was derived, (D) consensus as well as the reference sequence were trimmed to the same length; (E) All the consensus sequences were then concatenated according to the mitogenome order. (PNG 57 KB)

12863_2013_1216_MOESM3_ESM.png

Additional file 3: High-resolution phylogeny analysis. The tree was inferred based on nucleotide alignment (7515 bp long coding sequence) in MrBayes. The genome names as well as the EL and ES concatamers described in this paper had been marked on the branch tips. Red branches correspond to documented masculinized genomes. Abbreviations: Me – Mytilus edulis; Mg – Mytilus galloprovincialis; Mt – Mytilus trossulus; BMt – Baltic Mytilus trossulus; M – male genome type; F – female genome type. (PNG 53 KB)

12863_2013_1216_MOESM4_ESM.png

Additional file 4: The results of disparity index test (I D ). The test was performed in all pairwise comparisons in MEGA. Test values are above diagonal, statistical support (p values) are under the diagonal The P-values smaller than 0.05 (yellow marked) indicate significant rate heterogeneity. (PNG 86 KB)

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Sańko, T.J., Burzyński, A. Co-expressed mitochondrial genomes: recently masculinized, recombinant mitochondrial genome is co-expressed with the female – transmitted mtDNA genome in a male Mytilus trossulus mussel from the Baltic Sea. BMC Genet 15, 28 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2156-15-28

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2156-15-28