Abstract

Background

Arthropods are infected by a wide diversity of maternally transmitted microbes. Some of these manipulate host reproduction to facilitate population invasion and persistence. Such parasites transmit vertically on an ecological timescale, but rare horizontal transmission events have permitted colonisation of new species. Here we report the first systematic investigation into the influence of the phylogenetic distance between arthropod species on the potential for reproductive parasite interspecific transfer.

Results

We employed a well characterised reproductive parasite, a coccinellid beetle male-killer, and artificially injected the bacterium into a series of novel species. Genetic distances between native and novel hosts were ascertained by sequencing sections of the 16S and 12S mitochondrial rDNA genes. The bacterium colonised host tissues and transmitted vertically in all cases tested. However, whilst transmission efficiency was perfect within the native genus, this was reduced following some transfers of greater phylogenetic distance. The bacterium's ability to distort offspring sex ratios in novel hosts was negatively correlated with the genetic distance of transfers. Male-killing occurred with full penetrance following within-genus transfers; but whilst sex ratio distortion generally occurred, it was incomplete in more distantly related species.

Conclusion

This study indicates that the natural interspecific transmission of reproductive parasites might be constrained by their ability to tolerate the physiology or genetics of novel hosts. Our data suggest that horizontal transfers are more likely between closely related species. Successful bacterial transfer across large phylogenetic distances may require rapid adaptive evolution in the new species. This finding has applied relevance regarding selection of suitable bacteria to manipulate insect pest and vector populations by symbiont gene-drive systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Reproductive parasites represent a diverse assemblage of maternally inherited microorganisms that induce aberrations in their hosts' reproductive biology in order to proliferate within arthropod populations. Their vertical transmission route greatly limits opportunities for interspecific transfer. However, phylogenies of hosts and parasites are generally not congruent, indicating that interspecific horizontal transfer events characterise the evolutionary history of these selfish genetic elements [1].

Two different modes of reproductive parasitism exist that aid the maintenance of these microbes in host populations. Some maternally inherited parasites bias host progeny sex ratios in favour of female offspring, through which they then achieve transmission (by feminization, parthenogenesis induction or male-killing); others modify sperm of infected males, in order to reduce the fitness of the uninfected females with which they mate (cytoplasmic incompatibility) [2]. Whilst Wolbachia is the best known, a variety of other microbial taxa has also evolved to manipulate arthropod reproduction, including microsporidia, gamma proteobacteria and members of the genera Cardinium, Rickettsia and Spiroplasma [2–5].

Individual symbioses between reproductive parasites and host species are generally short-lived relative to the speciation rate of hosts [6, 7] (although exceptions exist [8]). Transience may be due to host resistance evolution [9] or alternatively some sex ratio distorters risk driving host extinction due to male shortage [10]. Long term persistence of parasite lineages therefore demands horizontal transfer to exploit new host species. It seems logical that horizontal transfer should be more common within species than between them. Nevertheless strong linkage disequilibrium usually exists between bacterial strains and host mitochondrial DNA, indicating that intraspecific horizontal transfer is exceptionally rare [11–14]; opportunities for transmission between species must thus be highly restricted. One exception is the close ecological contact between parasitoids and their hosts, which may facilitate transfer between wasps following oviposition in a common host [15, 16] and between host and parasitoid [17, 18].

Three potential routes exist for a species to acquire a reproductive parasite infection: direct transfer of infective material, introgressive hybridisation or co-speciation of host and bacterium. Phylogenetic studies indicate that the majority of symbioses originate from infective transfer: bacterial strains are usually considerably more closely related to each other than are their hosts [6, 19, 20]. However, such studies cannot generally distinguish whether transfer occurred directly between two hosts, or if unstudied intermediate species were involved (but exceptions are known [18]). Although rare, cases exist where high recent host speciation rates have enabled host-parasite co-speciation [8]. Furthermore, hybridisation between closely related hosts has permitted introgression of Wolbachia in at least two cases and may be responsible for others [12, 21]. Whatever the transmission route, phylogenetic studies reveal that closely related reproductive parasite strains may specialise on closely related arthropod species; either reflecting symbiont adaptation to similar hosts or the frequency of horizontal transmission opportunities [6, 22]. Once a reproductive parasite has infected a novel host, the probability of invasion will be determined by its ability to induce a reproductive phenotype, its vertical transmission efficiency and its virulence in the new species.

An increasing number of studies report experimental interspecific transfers of Wolbachia and other symbionts [23–28]; most of these transfers have been intra-generic. Transfection of the Drosophila simulans cytoplasmic incompatibility (CI) strain w Ri into D. melanogaster and parthenogenesis inducing (PI) Wolbachia within the Trichogramma genus both resulted in maternal transmission and expression of the original phenotype [23, 25]. Host-shifts of increasing phylogenetic distance have had variable success. Whilst the D. simulans w Ri strain transmitted and induced CI in Aedes albopictus, a PI Wolbachia from Muscidifurax uniraptor transmitted but induced no phenotype in D. simulans [24, 29]. Experimental transfer of Drosophila SROs (male-killers) generally led to establishment in other Drosophila species; however, in some cases male-killing ability was reduced and maternal transmission unstable [27].

The experimental transfer of reproductive parasites between host species is of practical as well as evolutionary interest. Due to their ability to spread deterministically through host populations, microbes such as Wolbachia have been proposed as potential gene drive systems to control insect pest population sizes and manipulate vector competence [30, 31]. In addition to genetically engineering the symbionts concerned, such techniques may require infection of target species with well characterised bacterial strains from other hosts. Some successful transfers to vector species have recently been reported [32] but others have had less promising results [26].

There is phylogenetic evidence for horizontal transfer of bacteria between both closely and distantly related host species and an increasing number of reports demonstrating experimental transfection. However, only a minority of studies have attempted transfers outside the native genus and systematic research to investigate the effect of phylogenetic distance on the success of experimental infections is lacking. It also seems likely that there is a publication bias towards reports of successful transfection studies.

This study tested the hypothesis that increasing phylogenetic distance between native and novel hosts decreases the likelihood of reproductive parasites colonising a new species. The Spiroplasma male-killer of the coccinellid beetle Adalia bipunctata was employed because it has previously been demonstrated to transfer repeatably by injection [33]. The bacterium was injected into pupae of seven novel coccinellid species. Within the Adalia genus it was injected into both the native host A. bipunctata and its sister species A. decempunctata. We transfected five species outside the Adalia genus but within the Coccinellinae subfamily: Coccinella septempunctata, Harmonia quadripunctata, Anisosticta novemdecimpunctata, Calvia quatuordecimguttata and Propylea quatuordecimpunctata. We also injected Exochomus quadripustulatus, which lies in the Chilocorinae subfamily [34]. Finally, we injected the non-male-killing Spiroplasma symbiont of the aphid Acyrthosiphon pisum [35] into A. bipunctata. In each case three questions were investigated: could the bacterium establish an infection, could it transmit trans-ovarially and did it kill males in the novel host?

Results

Phylogenetic relationships between host species

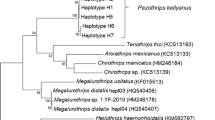

We produced 661 bp of 16S and 396 bp of 12S mitochondrial rDNA sequence; of the 1057 sites in our dataset, 386 were variable and 200 parsimony informative. The neighbour joining tree produced (Figure 1) broadly confirmed existing phylogenetic positions based on morphological characters [34].

Phylogenetic relationships of the coccinellid beetle species, derived from a combined 16S and 12S mitochondrial rDNA dataset. Tree estimation procedures are described in methods. The results of 1000 bootstrap resampling replicates are given next to branches, branch lengths are proportional to genetic distance (base substitutions per site, see scale bar). Tribolium castaneum is included as an outgroup.

Parental Lines

The female parents of all species from which recipient pupae for injection were derived produced offspring sex ratios not significantly different from equity (Fisher exact tests for all 19 parents, P > 0.18). Negative PCR results demonstrated that no parents were infected by the bacterial taxa Spiroplasma, Rickettsia, Wolbachia or Flavobacteria.

Adalia genus transfers

In total 33 A. bipunctata control females that had been injected with their native Spiroplasma were bred. They produced no male offspring (Figure 2). Mean progeny per line was 37.5 (range 4 – 95); in all, 1239 females resulted. Matriline sex ratios differed significantly from equity in 28 cases (Fisher exact test, Bonferroni corrected for 33 multiple comparisons). All females laying substantial numbers of eggs had hatch-rates below 50% (mean = 0.32) indicating that male-killing was taking place (Figure 3). An F1 female from each line was confirmed infected with Spiroplasma by PCR. The microinjection technique was thus both effective and replicable; infectivity of all homogenate samples used to inject novel species was confirmed.

Offspring sex ratios produced by females of each species injected with the A. bipunctata Spiroplasma male-killer. Average proportions of female and male offspring are represented by black and grey shading respectively. Species bars are shown in order of increasing genetic distance from A. bipunctata (left to right). Number of matrilines and total number of offspring per species are given above each bar. The results of Fisher exact tests for the significance of sex ratio deviations away from equity are indicated above bars by asterisks. Coccinella septempunctata females produced no offspring.

Hatch rates of eggs laid by females of the species injected with the A. bipunctata Spiroplasma male-killer. Average proportions of eggs that hatched are shown by black bars. Proportions of unhatched eggs are divided between those that showed no signs of embryonic development (in white) and those that became grey and died shortly before hatching (in grey). Species bars are shown in order of increasing genetic distance from A. bipunctata (left to right). Number of matrilines and total number of offspring per species are given above each bar.

Complete male-killer expression also occurred in A. decempunctata transfected lines. Sixteen females were bred, which all solely produced female offspring, 480 in total (Figure 2). Mean offspring number per line was 30.0 (range 4 – 48), 14 progeny sex ratios differed significantly from equity (Fisher exact test, Bonferroni corrected for 16 multiple comparisons). Low hatch rates were again recorded (mean = 0.27) and one offspring from each female was demonstrated Spiroplasma infected by PCR.

Inter-genus transfers

PCR tests at least six weeks after injection detected Spiroplasma infections in 100% of the parental females for all six species outside the Adalia genus (total n = 70; n per species 8 – 15). The bacterium therefore survived and replicated in these novel hosts. However, inter-genus transfers generally resulted in incomplete sex ratio distortion and impaired vertical transmission. These factors could not be assessed in C. septempunctata for which all females (n = 13) injected with the Spiroplasma were sterile (see below). In total, across the five remaining species 27 fertile females produced 334 offspring, 66% were female. All species exhibited significantly female-biased sex ratios except for E. quadripustulatus (Figure 2). Many females of the five species displayed low egg hatch rates, fecundity and survivorship. However, except in C. septempunctata, a considerable proportion of eggs hatched or reached late embryonic development (became grey); thus low hatch rates did not result from infertility and were indicative of male-killing (Figure 3). Pooling across species, sex ratio distortion was significantly impaired in females outside the native genus (mean sex ratio = 0.26 ± 0.05 SEM, n = 27) in comparison to transfers to congeneric A. decempunctata hosts (mean sex ratio = 0.0 ± 0.0 SEM, n = 16) (Wilcoxon W(n = 27,16) = 208; P < 0.001). Furthermore, a significant positive correlation between mean offspring sex ratio and genetic distance of transfection existed across species, indicating that progressively more distant host shifts reduced the degree of sex ratio distortion the bacterium achieved (Figure 4a) (rs(n = 6) = 0.829; P < 0.042).

Spiroplasma transmission rates in novel host-parasite associations were assessed by PCR (Table 1). Vertical transmission was perfect in A. bipunctata and A. decempunctata. However, only in two of the five fertile species outside the Adalia genus (A. novemdecimpunctata and E. quadripustulatus) did all offspring inherit the bacterium. Calvia quatuordecimguttata females behaved inconsistently: three females transmitted the Spiroplasma to all offspring tested (16 females, 1 male), whereas five females transmitted it to none (20 females, 14 males). Harmonia quadripunctata females were similarly variable: one female produced a significant sex ratio bias of 0.17 (n = 18) and transmitted to all offspring tested (7 females, 1 male), whereas another whose sex ratio was 0.47 (n = 53) transmitted to only 19% of progeny (19 females, 23 males tested). Propylea quatuordecimpunctata females produced a strongly female-biased sex ratio (0.11, n = 45) but surprisingly only 15% of offspring were infected when assayed as adults (n = 20). The bacterial transmission rate in hosts following inter-generic transfers (mean = 0.61 ± 0.09 SEM, n = 26) was significantly lower than that in congeneric A. decempunctata females (mean = 0.0 ± 0.0 SEM, n = 16) (Wilcoxon W(n = 26,16) = 483 P < 0.001). However, considering all interspecfic transfections, the negative relationship between mean transmission rate and genetic distance was not significant (Figure 4b) (rs(n = 6) = -0.213; P = 0.686). In three non-Adalia species (H. quadripunctata, A. novemdecimpunctata and E. quadripustulatus) a considerable percentage of male progeny were infected (Table 1). Pooling across all inter-genus transfers 46% (n = 72) of male offspring survived embryonic infection and carried the Spiroplasma as adults.

Relationship between host shift genetic distance and bacterial traits in novel species. Figure 4a – the relationship between interspecific transfer distance and the degree of host offspring sex-ratio distortion achieved by the male-killer (proportion male); the correlation is significant (see text). Figure 4b – the relationship between host shift genetic distance and vertical transmission to host offspring (proportion infected); the correlation is not significant (see text). Data points represent means for each species. A least squares best fit line fitted through the origin (4a) and through 1.0 (4b) is shown for each graph. All interspecific transfections are represented apart from C. septempunctata (for with no offspring resulted): brown, A. decempunctata; blue, P. quatuordecimpunctata; green, C. quatuordecimguttata; red, A. novemdecimpunctata, black; H. quadripunctata, orange; E. quadripustulatus. Error bars show standard errors, where no bar is visible variance was zero (apart from E. quadripustulatus for which n = 1).

Coccinella septempunctata responded unusually to Spiroplasma injection: all females were sterile. Thirteen injected females laid eggs, however not one hatched (n = 1889, mean eggs per female 145.3). All eggs remained yellow and showed no signs of embryonic development. Each female was mated to at least two independent males to ensure male infertility was not the cause. Egg clutches laid by these females carried the Spiroplasma (n = 10). Subsequently, 14 further females were produced that had been injected with homogenate of uninfected A. bipunctata females. Ten were fertile (71%) with hatch rates ranging from 0.07 to 0.81. The mean hatch rates of females injected with uninfected and infected homogenate (0.29 ± 0.07 SEM and 0.00 ± 0.00 SEM respectively) differed significantly (t-test, arcsin transformed data, t(v = 25)= 4.41; P = 0.002).

In addition, a non-male-killing Spiroplasma from the aphid Acyrthosiphon pisum was injected into A. bipunctata pupae. One egg clutch was tested for Spiroplasma from each of 50 injected females; none was infected. These 50 females were all similarly uninfected when they were killed and tested by PCR at least 5 weeks post-injection. Four individuals tested within two days of injection shortly after pupal emergence were all positive.

Discussion

This study investigated the host specificity of a reproductive parasite, the male-killing Spiroplasma of the coccinellid beetle Adalia bipunctata. We injected it into seven novel species and investigated bacterial transmission and sex ratio distortion. We tested the hypothesis that the phylogenetic distance between native and potential novel species has constrained host-shifts during male-killer evolution. The full male-killing phenotype was retained following transfers within the native genus, but in more distantly related species inefficient transmission or incomplete sex ratio distortion occurred.

Across every species tested injections always established an infection; bacteria were thus consistently able to survive the immune response associated with host injury and interact with cells in novel species. Wolbachia and Spiroplasma reproductive parasites do not naturally stimulate their hosts' immune systems, but Spiroplasma densities do fall following artificial immune challenge [36, 37]. This male-killer was therefore probably able to maintain immune evasion in novel hosts. Immune evasion may be aided if bacteria reside permanently or at times within host cells, where the antimicrobial response does not operate. The failure of the inter-order transfer of the non-male-killing A. pisum symbiont suggests that Spiroplasma tolerance to novel host environments is not without limit.

Bacteria were detected in eggs and offspring of all novel species following interspecific transfer between coccinellids. Thus no qualitative constraint to trans-ovarial transmission exists at this phylogenetic level. Bacterial transmission in novel species suggests absence of very tight specificity in the molecular interactions required, or considerable evolutionary conservation of the host molecules exploited. However, the efficiency and consistency of maternal inheritance did vary between species. Whilst transmission was perfect in A. bipunctata and A. decempunctata, in some cases outside the native genus it was reduced. Overall there was no consistent correlation between host-shift genetic distance and transmission rate; indeed no uninfected offspring were detected in two of the more distantly related species A. novemdecimpunctata and E. quadripustulatus.

The Spiroplasma maintained an ability to distort sex ratios following all inter-specific shifts across the native sub-family (Coccinellinae). However, as genetic distance of the novel host increased the degree of sex ratio distortion achieved by the bacterium fell. Whilst male-killing did occur outside the Adalia genus, in most other species infected males were produced. Therefore, in some cases, whilst the bacterium did transmit, male-killing failed. To distort sex ratios male-killers must interact with host sex determination mechanisms or male-specific gene products [38] and also be present in high enough density to kill male embryos [39, 40]. It is possible that bacterial density in distantly related species was lower than in the native host, as has been reported following other interspecific transfections [23, 41]. If correct, this hypothesis could explain the variable and reduced transmission rates as well as inefficient male-killing observed in some novel hosts. Phylogenetic variation in the molecules used to detect or kill males (such as sex determination pathways) may provide a further explanation for low male-killing penetrance in novel species. Male-killers require the ecological advantage provided by male embryo death to spread in host populations [42], therefore incomplete sex ratio distortion (due to low transmission or inefficient male-killing) would inhibit invasion of novel host species.

We did not set out to investigate the virulence of this bacterium in novel species. However, we found all C. septempunctata hosts were sterile following injection of the Spiroplasma. It is possible this resulted from specific pathogeneic effects of infection, or an inability of the bacterium to selectively kill only male embryos in this species. Strong selection acts on vertically transmitted parasites to reduce virulence costs on their hosts [43]. Future studies might assess pathogenic effects of reproductive parasites following host shifts (eg [41]). Increased virulence would represent another factor reducing the probability of population invasion following interspecific transfers.

Our study has assessed the average performance of a reproductive parasite in a panel of novel host species. There was variation in male-killing and transmission between individuals in most transfected species. It therefore remains possible that infections that kill males and transmit efficiently may occasionally establish following transfers beyond the genus level. Such events, however rare, might provide opportunities for parasites to successfully invade. In addition, we have not assessed transmission and sex ratio distortion past the F1 generation. Nevertheless, our data provide controlled comparisons of the likelihood of reproductive parasites retaining high fitness and establishing in a population following host shifts. A previous study transferred A. novemdecimpunctata's native male-killing Spiroplasma into A. bipunctata and also reported incomplete male-killing [20]. Therefore our data might have general relevance beyond this particular male-killing parasite. The manipulations of reproductive parasites employing other phenotypes may well be adversely affected by host shifts in a similar phylogenetically dependent manner.

We have demonstrated clear phylogenetic constraints to the interspecific movement of a male-killing bacterium. Molecular studies suggest that natural reproductive parasite host-shifts have occurred more frequently between closely related hosts [6, 22]. The present data indicate this may be the result of similarity in host physiology or genetics. Given molecular evidence that closely related bacterial strains do infect distantly related species [19, 20], we propose two scenarios for horizontal interspecific movement. Firstly, male-killers may make phylogenetically 'small steps' with relative ease whilst retaining efficiency of the original reproductive manipulation. Secondly, if phylogenetic 'giant leaps' occur, then persistence in novel hosts may require rapid bacterial evolution to improve sex ratio distortion, transmission or virulence.

One widely discussed application for bacterial reproductive parasites is in the control of insect pest or disease vector populations [30, 44, 45]. Releases of CI Wolbachia strains might be used to reduce pest species population sizes [31, 46]. Alternatively, the invasive nature of CI Wolbachia might be exploited to drive trans-genes conferring refractoriness to human disease transmission through insect vector populations [30]. The technical and practical aspects of these techniques have yet to be fully resolved. However, most require the introduction of well characterised symbionts into the target species. Such experimental transfers have indeed been achieved (eg [32]). Nevertheless our study emphasises that except in the case of small phylogenetic steps, ensuring high bacterial transmission fidelity and phenotype retention in field conditions may be a considerable challenge. Engineering native infections of the species concerned may be more generally successful than introducing novel bacteria.

Conclusion

This study indicates that constraints of host physiology or genetics have limited opportunities for successful horizontal transfers during reproductive parasite evolution. We demonstrated that the Adalia bipunctata male-killing Spiroplasma was only able to maintain full transmission and offspring sex ratio distortion after being injected into hosts within the native genus; more distant transfers resulted in low-fitness infections. Reproductive parasites thus exhibit a considerable degree of evolutionary specialisation on their natural host. Host-shift genetic distance was significantly correlated with sex ratio distortion ability but its relationship with transmission rate was inconsistent and not significant. This finding suggests the possibility that the reproductive manipulations of these parasites may be more generally sensitive to host shifts than their transovarial transmission. Our data offer experimental support for phylogenetic studies which indicate that host-shifts are relatively frequent between closely related species.

Methods

Ladybird Material

Donor individuals were A. bipunctata females carrying this species' native male-killing Spiroplasma, which displays perfect vertical transmission in the laboratory and has previously been shown infective by injection [33]. Donors were F1 progeny of parents collected in Stockholm. Novel recipient species were all collected close to Cambridge, UK. Offspring of field collected females were reared in the laboratory to pupal stage using standard techniques [47]. Parental females of each species from which recipient pupae were derived were assayed by PCR for the presence of any known coccinellid sex ratio distorting bacteria (see below) and offspring sex ratios were recorded to ensure that they were equitable in the generation prior to injection. Adalia bipunctata is host to at least three other male-killers, a Rickettsia and two strains of Wolbachia [48, 49], furthermore A. decempunctata carries a male-killing Rickettsia [50], A. novemdecimpunctata carries a male-killing Spiroplasma [20] and H. quadripunctata has a male-killing flavobacterium (Majerus unpublished). None of these symbionts was present in any recipient pupae.

Spiroplasma transfection

Injection techniques followed Tinsley and Majerus [20]. Briefly, A. bipunctata abdomen homogenate was prepared in 0.7% NaCl (25 μl per abdomen), then injected into recipient pupae between the second and third abdominal segments using pulled capillary needles attached to an oil-filled Hamilton syringe. The volume injected was standardised according to recipient pupal size: 0.5 μl was employed for A. novemdecimpunctata and P. quatuordecimpunctata, 1 μl for A. bipunctata, A. decempunctata and E. quadripustulatus, 1.25 μl for C. quatuordecimguttata and 1.5 μl for C. septempunctata and H. quadripunctata. Homogenate infectivity was confirmed on each occasion by injection back into uninfected A. bipunctata pupae. Whole body homogenate of Acyrthosiphon pisum adults carrying their Spiroplasma symbiont were similarly prepared and injected into A. bipunctata pupae. Aphids were derived from a laboratory clone collected in Bayreuth, Germany in 2001.

After pupae eclosed, females were maintained at 21°C on a mixed diet of aphids (Acyrthosiphon pisum) and artificial food [47] for one month before breeding to allow bacterial replication; males were discarded. Most species were bred directly following this incubation period. However, C. quatuordecimguttata, E. quadripustulatus and most C. septempunctata require diapause to initiate oviposition [51] therefore females were stored in an incubator at 4–8°C (24 hr dark) for around three months before breeding. Injection caused over 50% pupal mortality, further deaths occurred between eclosion and breeding and many females failed to oviposit: several hundred pupae of each species were injected to derive breeding samples. Surviving females were fed aphids, mated and allowed to oviposit at 21°C. Egg hatch rates (proportion hatched) and progenic sex ratios (proportion male) were assessed. The significance of offspring sex ratio deviations from 1:1 was calculated using one-tailed Fisher exact tests. PCR assays were used to determine if Spiroplasma bacteria were present in the injected females, their eggs and their offspring.

Molecular techniques

Molecular methods followed Tinsley and Majerus [20]. In short, DNA was extracted by incubating samples in buffer containing Chelex-100 resin, DTT and Proteinase K, then used in diagnostic PCR reactions employing primers specific for the following bacterial taxa: Spiroplasma (MGSO – Ha-In-1 [33, 52]), Wolbachia (wps81f – wsp691r [53]), Rickettsia (RSSUF – RSSUR [50]) and Flavobacteria (FL1 – FL2 [54]). Products were identified by agarose gel electrophoresis. Presence of amplifiable template was verified using mitochondrial DNA primers C1-J-2630 and TL2-N-3014 [55] and universal invertebrate ribosomal primers BD1 and 4S [56, 57]; if product was lacking the sample was discarded.

For phylogenetic analysis we investigated two conserved sections from the 3' ends of the 16S and 12S mitochondrial ribosomal subunits of all host species. These were amplified using primer pairs N1-J-12585 – LR-N-13398 (16S) and SR-J-14233 – SR-N-14588 (12S) [58]. Products were purified using Sigma GeneElute™ columns and sequenced directly using the PCR primers by MWG-Biotech (EMBL accession numbers [AM779598] – [AM779613]). We discarded the data from the 3' region of the 16S fragment which spanned the 5' end of the ND1 gene and the leucine tRNA and combined the remaining sequence from the two rDNA genes. A sequence alignment was constructed using CLUSTALW and manually edited, then a tree was constructed using the neighbour joining method in MEGA version 4.0 [59] and evaluated by maximum composite likelihood, employing pair-wise gap deletion and a gamma distributed rate variation parameter of 0.255 (calculated in PAUP* version 4.0b8 [60]). Robustness of this tree was tested by performing 1000 bootstrap replicates. Genetic distances of novel hosts from A. bipunctata were calculated in MEGA using the parameter options above. Correlations of the species means for bacterial transmission rate and offspring sex ratio with genetic distance were determined non-parametrically using Spearman rank tests due to non-normality of dependent variables.

References

Stouthamer R, Breeuwer JAJ, Hurst GDD: Wolbachia pipientis: microbial manipulator of arthropod reproduction. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1999, 53: 71-102. 10.1146/annurev.micro.53.1.71.

Bandi C, Dunn AM, Hurst GDD, Rigaud T: Inherited microorganisms, sex-specific virulence and reproductive parasitism. Trends in Parasitology. 2001, 17 (2): 88-94. 10.1016/S1471-4922(00)01812-2.

Hurst GDD, Jiggins FM: Male-killing bacteria in insects: mechanisms, incidence, and implications. Emerging Infectious Diseases. 2000, 6: 329-336.

Hunter MS, Perlman SJ, Kelly SE: A bacterial symbiont in the Bacteroidetes induces cytoplasmic incompatibility in the parasitoid wasp Encarsia pergandiella. Proc Biol Sci. 2003, 270 (1529): 2185-2190. 10.1098/rspb.2003.2475.

Zchori-Fein E, Gottlieb Y, Kelly SE, Brown JK, Wilson JM, Karr TL, Hunter MS: A newly discovered bacterium associated with parthenogenesis and a change in host selection behavior in parasitoid wasps. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001, 98 (22): 12555-12560. 10.1073/pnas.221467498.

Schilthuizen M, Stouthamer R: Horizontal transmission of parthenogenesis-inducing microbes in Trichogramma wasps. Proc Biol Sci. 1997, 264 (1380): 361-366. 10.1098/rspb.1997.0052.

Shoemaker DD, Machado CA, Molbo D, Werren JH, Windsor DM, Herre EA: The distribution of Wolbachia in fig wasps: correlations with host phylogeny, ecology and population structure. Proc Biol Sci. 2002, 269 (1506): 2257-2267. 10.1098/rspb.2002.2100.

Marshall JL: The Allonemobius-Wolbachia host-endosymbiont system: Evidence for rapid speciation and against reproductive isolation driven by cytoplasmic incompatibility. Evolution. 2004, 58 (11): 2409-2425.

Hornett EA, Charlat S, Duplouy AM, Davies N, Roderick GK, Wedell N, Hurst GD: Evolution of male-killer suppression in a natural population. PLoS Biol. 2006, 4 (9): e283-. 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040283.

Jiggins FM, Hurst GDD, Majerus MEN: Sex ratio distorting Wolbachia cause sex role reversal in their butterfly hosts. Proc R Soc Lond B. 2000, 267: 69-73. 10.1098/rspb.2000.0968.

Turelli M, Hoffmann AA, McKechnie SW: Dynamics of cytoplasmic incompatibility and mtDNA variation in natural Drosophila simulans populations. Genetics. 1992, 132 (3): 713-723.

Jiggins FM: Male-killing Wolbachia and mitochondrial DNA: selective sweeps, hybrid introgression and parasite population dynamics. Genetics. 2003, 164: 5-12.

Ironside JE, Dunn AM, Rollinson D, Smith JE: Association with host mitochondrial haplotypes suggests that feminizing microsporidia lack horizontal transmission. J Evol Biol. 2003, 16 (6): 1077-1083. 10.1046/j.1420-9101.2003.00625.x.

Jiggins FM, Tinsley MC: An ancient mitochondrial polymorphism in Adalia bipunctata linked to a sex-ratio-distorting bacterium. Genetics. 2005, 171 (3): 1115-1124. 10.1534/genetics.105.046342.

Huigens ME, Luck RF, Klaassen RHG, Maas M, Timmermans M, Stouthamer R: Infectious parthenogenesis. Nature. 2000, 405 (6783): 178-179. 10.1038/35012066.

Huigens ME, de Almeida RP, Boons PAH, Luck RF, Stouthamer R: Natural interspecific and intraspecific horizontal transfer of parthenogenesis-inducing Wolbachia in Trichogramma wasps. Proc Biol Sci. 2004, 271 (1538): 509-515. 10.1098/rspb.2003.2640.

Heath BD, Butcher RDJ, Whitfield WGF, Hubbard SF: Horizontal transfer of Wolbachia between phylogenetically distant insect species by a naturally occurring mechanism. Curr Biol. 1999, 9 (6): 313-316. 10.1016/S0960-9822(99)80139-0.

Vavre F, Fleury F, Lepetit D, Fouillet P, Bouletreau M: Phylogenetic evidence for horizontal transmission of Wolbachia in host-parasitoid associations. Mol Biol Evol. 1999, 16 (12): 1711-1723.

Dyson EA, Kamath MK, Hurst GDD: Wolbachia infection associated with all-female broods in Hypolimnas bolina (Lepidoptera : Nymphalidae): evidence for horizontal transmission of a butterfly male killer. Heredity. 2002, 88: 166-171. 10.1038/sj.hdy.6800021.

Tinsley MC, Majerus MEN: A new male-killing parasitism: Spiroplasma bacteria infect the ladybird beetle Anisosticta novemdecimpunctata (Coleoptera : Coccinellidae). Parasitology. 2006, 132: 757-765. 10.1017/S0031182005009789.

Narita S, Nomura M, Kato Y, Fukatsu T: Genetic structure of sibling butterfly species affected by Wolbachia infection sweep: evolutionary and biogeographical implications. Molecular Ecology. 2006, 15 (4): 1095-1108.

Jiggins FM, Bentley JK, Majerus MEN, Hurst GDD: Recent changes in phenotype and patterns of host specialisation in Wolbachia bacteria. Molecular Ecology. 2002, 11: 1275-1283. 10.1046/j.1365-294X.2002.01532.x.

Boyle L, O'Neill SL, Robertson HM, Karr TL: Interspecific and intraspecific horizontal transfer of Wolbachia in Drosophila. Science. 1993, 260: 1796-1799. 10.1126/science.8511587.

Braig HR, Guzman H, Tesh RB, O'Neill SL: Replacement of the natural Wolbachia symbiont of Drosophila simulans with a mosquito counterpart. Nature. 1994, 367: 453-455. 10.1038/367453a0.

Grenier S, Pintureau B, Heddi A, Lassabliere F, Jager C, Louis C, Khatchadourian C: Successful horizontal transfer of Wolbachia symbionts between Trichogramma wasps. Proc R Soc Lond B. 1998, 265: 1441-1445. 10.1098/rspb.1998.0455.

Ruang-areerate T, Kittayapong P: Wolbachia transinfection in Aedes aegypti: A potential gene driver of dengue vectors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006, 103 (33): 12534-12539. 10.1073/pnas.0508879103.

Williamson DL, Poulson DF: The sex ratio organisms (Spiroplasmas) of Drosophila. The Mycoplasmas. Edited by: Tully JG, Whitcomb RF. 1979, New York , Acad. Press, 3: 175-208.

Kellner RLL: Interspecific transmission of Paederus endosymbionts: relationship to the genetic divergence among the bacteria associated with pederin biosynthesis. Chemoecology. 2002, 12 (3): 133-138. 10.1007/s00012-002-8338-1.

Van Meer MMM, Stouthamer R: Cross-order transfer of Wolbachia from Muscidifurax uniraptor (Hymenoptera : Pteromalidae) to Drosophila simulans (Diptera : Drosophilidae). Heredity. 1999, 82: 163-169. 10.1038/sj.hdy.6884610.

Sinkins SP, Gould F: Gene drive systems for insect disease vectors. Nat Rev Genet. 2006, 7 (6): 427-435. 10.1038/nrg1870.

Dobson SL, Fox CW, Jiggins FM: The effect of Wolbachia-induced cytoplasmic incompatibility on host population size in natural and manipulated systems. Proc Biol Sci. 2002, 269 (1490): 437-445. 10.1098/rspb.2001.1876.

Xi ZY, Khoo CCH, Dobson SL: Wolbachia establishment and invasion in an Aedes aegypti laboratory population. Science. 2005, 310 (5746): 326-328. 10.1126/science.1117607.

Hurst GDD, Schulenburg JHG, Majerus TMO, Bertrand D, Zakharov IA, Baungaard J, Volkl W, Stouthamer R, Majerus MEN: Invasion of one insect species, Adalia bipunctata, by two different male-killing bacteria. Insect Mol Biol. 1999, 8: 133-139. 10.1046/j.1365-2583.1999.810133.x.

Sasaji H: Phylogeny of the family Coccinellidae (Coleoptera). Etizenia. 1968, 35: 1-37.

Fukatsu T, Tsuchida T, Nikoh N, Koga R: Spiroplasma symbiont of the pea aphid, Acyrthosiphon pisum (Insecta : Homoptera). Appl Environ Microbiol. 2001, 67 (3): 1284-1291. 10.1128/AEM.67.3.1284-1291.2001.

Bourtzis K, Pettigrew MM, O'Neill SL: Wolbachia neither surpresses nor induces antimicrobial peptides. Insect Mol Biol. 2000, 9: 635-639. 10.1046/j.1365-2583.2000.00224.x.

Hurst GDD, Anbutsu H, Kutsukake M, Fukatsu T: Hidden from the host: Spiroplasma bacteria infecting Drosophila do not cause an immune response, but are suppressed by ectopic immune activation. Insect Mol Biol. 2003, 12 (1): 93-97. 10.1046/j.1365-2583.2003.00380.x.

Veneti Z, Bentley JK, Koana T, Braig HR, Hurst GDD: A functional dosage compensation complex required for male killing in Drosophila. Science. 2005, 307 (5714): 1461-1463. 10.1126/science.1107182.

Anbutsu H, Fukatsu T: Population dynamics of male-killing and non-male-killing spiroplasmas in Drosophila melanogaster. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2003, 69 (3): 1428-1434. 10.1128/AEM.69.3.1428-1434.2003.

Kageyama D, Anbutsu H, Shimada M, Fukatsu T: Spiroplasma infection causes either early or late male killing in Drosophila, depending on maternal host age. Naturwissenschaften. 2007, 94 (4): 333-337. 10.1007/s00114-006-0195-x.

McGraw EA, Merritt DJ, Droller JN, O'Neill SL: Wolbachia density and virulence attenuation after transfer into a novel host. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002, 99 (5): 2918-2923. 10.1073/pnas.052466499.

Hurst GDD, Majerus MEN: Why do maternally inherited microorganisms kill males?. Heredity. 1993, 71: 81-95.

Yamamura N: Evolution of mutualistic symbiosis: A differential equation model. Researches On Population Ecology. 1996, 38 (2): 211-218. 10.1007/BF02515729.

Karr TL: Cytoplasmic Incompatibility - Giant Steps Sideways. Curr Biol. 1994, 4 (6): 537-540. 10.1016/S0960-9822(00)00118-4.

Sinkins SP, Curtis CF, O'Neill SL: The potential application of inherited symbiont systems to pest control. Influential passengers: microbes and invertebrate reproduction. Edited by: O'Neill SL, Hoffman AA, Werren JH. 1997, Oxford , Oxford University Press, 125-154.

Laven H: Eradication of Culex pipiens fatigans through cytoplasmic incompatibility. Nature. 1967, 216: 383-384. 10.1038/216383a0.

Majerus MEN, Kearns PWE, Ireland H, Forge H: Ladybirds as teaching aids: 1 Collecting and culturing. Journal of Biological Education. 1989, 23 (2): 85-95.

Werren JH, Hurst GDD, Zhang W, Breeuwer JAJ, Stouthamer R, Majerus MEN: Rickettsial relative associated with male killing in the ladybird beetle (Adalia bipunctata). Journal of Bacteriology. 1994, 176: 388-394.

Hurst GDD, Jiggins FM, Schulenberg JHG, Bertrand D, West SA, Goriacheva II, Zakharov IA, Werren JH, Stouthamer R, Majerus MEN: Male-killing Wolbachia in two species of insect. Proc R Soc Lond B. 1999, 266: 735-740. 10.1098/rspb.1999.0698.

Schulenburg JHG, Habig M, Sloggett JJ, Webberley KM, Bertrand D, Hurst GDD, Majerus MEN: Incidence of male-killing Rickettsia spp. (α-proteobacteria) in the ten-spot ladybird beetle Adalia decempunctata L. (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae). Appl Environ Microbiol. 2001, 67: 270-277. 10.1128/AEM.67.1.270-277.2001.

Majerus MEN: Ladybirds. New Naturalist. 1994, London , Harper Collins

van Kuppeveld FJM, van der Logt HTM, van Zoest MJ, Quint WGV, Niesters HGM, Galama JMD, Melchers WJG: Genus- and species-specific identification of the mycoplasmas by 16s rDNA amplification. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1992, 58: 2606-2615.

Zhou WF, Rousset F, O'Neill S: Phylogeny and PCR based classification of Wolbachia strains using wsp gene sequences. Proc Biol Sci. 1998, 265 (1395): 509-515. 10.1098/rspb.1998.0324.

Hurst GDD, Hammarton TM, Bandi C, Majerus TMO, Bertrand D, Majerus MEN: The diversity of inherited parasites of insects: the male killing agent of the ladybird beetle Coleomegilla maculata is a member of the Flavobacteria. Genet Res. 1997, 70: 1-6. 10.1017/S0016672397002838.

Schulenburg JHG, Hurst GDD, Tetzlaff D, Booth GE, Zakharov IA, Majerus MEN: History of infection with different male-killing bacteria in the two-spot ladybird beetle Adalia bipunctata revealed through mitochondrial DNA analysis. Genetics. 2002, 160: 1075-1086.

Bowles J, McManus DP: Rapid discrimination of Echinococcus species and strains using a polymerase chain reaction-based RFLP method. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1993, 57 (2): 231-240. 10.1016/0166-6851(93)90199-8.

Remigio EA, Blair D: Relationships among problematic North American stagnicoline snails (Pulmonata: Lymnaeidae) reinvestigated using nuclear ribosomal RNA internal transcribed spacer sequences. Canadian Journal Of Zoology. 1997, 75 (9): 1540-1545.

Simon C, Frati F, Beckenbach A, Crespi B, Liu H, Flook P: Evolution, weighting and phylogenetic utility of mitochondrial gene sequences and a compilation of conserved polymerase chain reaction primers. Ann Ent Soc Am. 1994, 87: 651-701.

Tamura K, Dudley J, Nei M, Kumar S: MEGA4: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis (MEGA) software version 4.0. Mol Biol Evol. 2007, 24 (8): 1596-1599. 10.1093/molbev/msm092.

Swofford DL: PAUP*. Phylogenetic analysis using parsimony (*and other methods). Version 4. 1998, Sunderland, Massachusetts. , Sinauer Associates

Acknowledgements

We thank Frank Jiggins for much helpful advice and assistance and are grateful to Ian Wright and Dennis Farrington for technical support. John Sloggett and Greg Hurst provided phylogenetic advice and three anonymous referees offered valuable comments on the manuscript. The A. pisum clone was supplied by John Sloggett, Grit Kunert and Wolfgang Weisser. MCT was funded by a BBSRC studentship.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Authors' contributions

MCT collected insect samples from the field, performed injections and conducted molecular work. MCT and MENM collaboratively designed the study, reared ladybirds in the laboratory and interpreted the results. MCT drafted the paper. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Tinsley, M.C., Majerus, M.E. Small steps or giant leaps for male-killers? Phylogenetic constraints to male-killer host shifts. BMC Evol Biol 7, 238 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2148-7-238

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2148-7-238