Abstract

Background

Chitin and chitosan are natural biopolymers found in shell of crustaceans, exoskeletons of insects and mollusks, as well as in the cell walls of fungi. These biopolymers have versatile applications in various fields such as biomedical, food industry, and agriculture. These applications are back to their biocompatibility, biodegradability, strong antibacterial effect, and non-toxicity.

Outcomes

The fungal biopolymers have many features that made them more advantageous than those biopolymers from seafood waste origin. Chitin and chitosan are not components of cell wall in all fungal species. The fungal classes of Basidiomycetes, Ascomycetes, Zygomycetes, and Deuteromycetes are known to contain chitin and chitosan in their cell walls. The amounts and characters of fungal biopolymers are affected by many factors so they should be optimized before increasing the scale of production. The statistical design of experiments is the most recent and advanced approach for optimization of various factors with more reliable results.

Conclusion

Although extensively studied, further studies concerning fungal chitin and chitosan should be conducted in order to be sure of safety for human use.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Worldwide, there are approximately 140 × 106 tons of synthetic polymers produced, annually. However, these synthetic polymers are somewhat stable and their biodegradation is limited. This necessitates the need for biodegradable polymers that are compatible with the ecosystem. Among these biopolymers, chitin and chitosan have attracted the attention of both scientists and industry men due to their numerous potential applications in biomedicine, agriculture, paper making, food industry, and textile industry (Akila 2014). The wider applications of chitin and chitosan are not only due to their abundance but also due to their non-toxicity and biodegradability (Islam et al. 2017).

Historically, chitin, a naturally abundant mucopolysaccharide, was first isolated by Braconnot (1811) from the cell walls of mushrooms where it was named “fungine.” In 1823, fungine was renamed as chitin by Odier (Odier 1823), almost three decades before the isolation of cellulose (Knorr 1984). Chitin follows cellulose in terms of abundance with annual biosynthesis of 100 billion tons (Tharanathan and Kittur 2003). Chitin is a main component in the shell wastes of crustaceans and also found in exoskeletons of insects and mollusks and in the cell walls of some fungi (Bhuiyan et al. 2013; Yeul and Rayalu 2013).

Chitosan was first discovered in 1859 by Rouget (Novak et al. 2003). After its discovery to present, it has become a source of numerous studies due to its versatile biological, chemical, and physical properties and wide range of applications (Bhuiyan et al. 2013). Although it has been found in some types of fungi, chitosan is, mostly, obtained from chitin deacetylation.

Initially, chitin and chitosan were obtained from the shell wastes of shrimps and crabs. However, their discovery in the fungal cell walls opened up the horizon for more research and biotechnological applications due to the absence of allergenic substances and less waste production (Chien et al. 2016). Moreover, fungal chitin and chitosan would offer non-seasonable and stable sources of raw material and consistent characters of the product.

The aim of the present review is to concentrate on the current and most recent researches on chitin and chitosan biosynthesis with a special focus on their fungal sources and factors affecting productivity as well as their biotechnological applications in various fields. Furthermore, this review is going to enlighten the most recent approach used for simulation and optimization of the various variables in a certain bioprocess.

Chitin and chitosan

Definitions and chemical structures

Chitin, a natural mucobiopolymer, is a hard, white, inelastic, and nitrogenous compound, composed of randomly distributed N-acetyl-d-glucosamine (N-GlcNAc) monomers (Islam et al. 2017). Following cellulose, chitin is considered as the second most abundant biopolymer on earth, with annual biosynthesis of more than 100 billion tons (Tharanathan and Kittur 2003). In nature, chitin polysaccharide is, enzymatically, synthesized by the transfer of a glycosyl of N-GlcNAc from uridinediphosphate-N-acetyl-d-glucosamine to chitodextrin acceptor (Sitanggang et al. 2012).

Chitosan is a linear biopolymer of β-(1-4)-linked-d-glucosamine (GlcN) units. Chitosan results from the deacetylation of chitin which is, almost, never complete and it still contains acetamide groups to some extent (Islam et al. 2017).

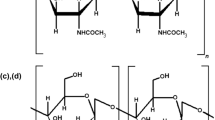

For both chitin and chitosan, their chemical structure is similar to that of cellulose, which consists of a polymer of several hundred units of β-(1-4) linked d-glucose (Bhuiyan et al. 2014). In chitin and chitosan, the hydroxyl group at position C-2 of cellulose has been replaced by an acetamide group (Fig. 1). Unlike cellulose, the nitrogen content of chitin and chitosan is 5–8% which makes them suitable for typical amines reactions (Kurita 2001). The commonly available chitin and chitosan are, generally, not strict homopolymers but they may exist as copolymers (Akila 2014). The presence of amine groups in both chitin and chitosan enables distinctive biological functions in addition to the application of modification reactions (Kumar 2000). Chitin and chitosan have many desirable properties such as non-toxicity, biodegradability, non-allergenic, bioactivity, biocompatibility, bioresorptivity, and good adsorption properties which make them suitable alternatives to synthetic polymers (Tan et al. 2009; Croisier and Jérôme 2013). However, the presence the amine and hydroxyl groups on each deacetylated unit make chitosan, chemically, more active than chitin. The chemical modifications of these reactive groups alter the physical and mechanical properties of chitosan (Islam et al. 2017).

Physicochemical properties

Solubility

Chitin has very few applications because it is insoluble in most solvents. In contrarily, chitosan has many applications because it is, readily, soluble in dilute acidic solutions such as acetic, formic, and lactic acids at pH < 6.0. The most commonly used solution is 1% acetic acid at about pH 4.0 (Zamani et al. 2008).

Molecular weight

Chitin and chitosan are considered as high molecular weight biopolymer. The molecular weight of these biopolymers varies with the variation of the source material and the preparation and extraction methods. The molecular weight of these biopolymers determines their suitable application, e.g., it has been reported that chitosan with low molecular weight has greater antimicrobial activity (Amorim et al. 2003; Franco et al. 2004; Tajdini et al. 2010; Moussa et al. 2013; Oliveira et al. 2014). The chitin molecular weight is as high as many Daltons. However, chitosan molecular weight may range from 100 to 1500 kDa due to the use of harsh chemical treatments. Chitosan of low molecular weight can be obtained either by chemical or enzymatic methods (Cai et al. 2006). Although, fungal chitin has unknown molecular mass, it has been proposed that Saccharomyces cerevisiae synthesizes a uniform chain of GlcNAc containing 120–170 monomer units which may correspond to 24,000–34,500 Da (Valdivieso et al. 1999).

Degree of deacetylation

The degree of deacetylation (DD) is one of the most important parameters that affect the physical and chemical characteristics of chitin and chitosan (copolymers), activity, and applications (Akila 2014). It can be defined as the molar fraction of GlcN in chitosan and represented by the following equation:

where (nGlcN) represents the average number of d-glucosamine units and (nGlcNAc) represents the average number of N-acetyl glucosamine units.

For example, only chitin samples with DD of about 50% are soluble in water, whereas those with lower or higher DD were insoluble (Wu 2004). Chitosan molecules with high DD (> 85%) have strong positive charge in aqueous solution with pH bellow 6 (Sorlier et al. 2001).

Various methods have been proposed for determination of chitin and chitosan DD. These techniques include:

-

i.

Infrared spectroscopy (IR) (Brugnerotto et al. 2001; Duarte et al. 2002): it is the most popular technique because it is very simple and requires minimal sample preparation. However, the use of this technique requires precise calibration.

-

ii.

13C solid-state NMR (Duarte et al. 2001): it appears to be the most reliable method and is often used as a reference. Unfortunately, it is not available at most laboratories due to the elevated cost.

-

iii.

High-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC) (Han et al. 2015): it depends on the hydrolysis of chitin and chitosan and analysis of the produced acetic acid.

-

iv.

Potentiometric titration (Ke and Chen 1990).

-

v.

Ultraviolet spectrometry (Liu et al. 2006).

Potentiometric titration and ultraviolet spectrometry require dissolved samples and therefore not suitable for chitosan with (DD < 50%) and chitin.

Occurrence and biological functions in nature

Chitins is considered as the main component in the shells of crustaceans such as crab, shrimp, and lobster, and is also a component of the exoskeletons of insects and mollusks as well as in the cell walls of some fungi (Yeul and Rayalu 2013). However, chitin and chitosan are not present in higher animals and higher plants. Currently, shrimp and crab shell wastes are the main industrial sources for the large-scale production of chitin and chitosan. It has been reported that chitin represents 13–15% and 14–27% of dry weight of crab and shrimp processing wastes, respectively (Ashford et al. 1977). Processing of these biological wastes from marine food factories helps recycling and useful use of the wastes in other fields. The extraction of chitin and chitosan from these crustacean shell wastes requires stepwise chemical methods because they are composed of protein, lipids, inorganic salts, and chitin as main structural components (Kim and Rajapakse 2005).

Chitin is widely distributed in many classes of fungi including Ascomycetes, Basidiomycetes, and Phycomycetes. Fungal chitin is a component of the structural membranes and cell walls of mycelia, stalks, and spores. However, chitin is not found in all fungi and may be absent in one species that is closely related to another. Chitin was reported in Saccharomyces cerevisiae as a major component in primary septa between mother and daughter cells (Sbrana et al. 1995).

Industrial production

The crustacean shells annual production has been estimated as 1.2 × 106 tons worldwide (Synowiecki and Al-Khateeb 2003). As it has, already, mentioned, crab and shrimp shells are the main industrial source for the large-scale production of chitin and chitosan. These crustacean shell wastes contain, in addition to chitin, proteins, inorganic salts, pigments, and lipids as main structural components. Therefore, chemical extraction of chitin and chitosan should be employed to obtain the pure product. Briefly, the following steps should be performed:

-

1.

Demineralization/decalcification: the shell wastes are washed, dried, and ground to smaller sizes and minerals such as calcium carbonate are removed with good mixing with dilute hydrochloric acid at ambient temperature.

-

2.

Discoloration: to remove pigments from the produced chitin.

-

3.

Deproteinization: the pure chitin and chitosan should be prevented from protein contamination and, therefore, residual material is treated with dilute aqueous solution of sodium hydroxide to remove proteins, glycoproteins and branched polysaccharides.

-

4.

Acid reflux for separation of chitin and chitosan: the acidic treatment is usually carried out using 2 to 10% hydrochloric acid or acetic at 95 °C for 3 to 14 h.

-

5.

Deacetylation: for chitosan production, the resulting chitin is treated with 40–45% sodium hydroxide, in the absence of oxygen, at 160 °C for 1–3 h in a process called deacetylation in which the acetyl group is removed from chitin molecules (Fig. 2) (Roberts 1992). Repetition of this process can give a degree of deacetylation (DD) up to 98%, but the complete deacetylation can never be achieved (Mima et al. 1983). The degree of chitin deacetylation depends on the concentration of NaOH, reaction temperature, and time (Kasaai 2009.). However, at least 85% deacetylation should be achieved for a good solubility of chitosan (No and Meyers 1995).

In contrarily, the crude fungal chitin has a lower level of inorganic matters compared to crustacean shell wastes and thus the step of demineralization is not required during the processing (Teng et al. 2001).

Applications of chitin and chitosan

Biological properties

Chitin and chitosan have many intrinsic characteristics that make them suitable for versatile applications in various fields. These characteristics include biocompatibility, biodegradability, strong antibacterial effect, non-toxicity, and high humidity absorption (Aranaz et al. 2009). Furthermore, other biological properties such as antitumor, analgesic, hemostatic, antitumor, hypocholesterolemic, antimicrobial, and antioxidant properties have also been reported by researchers (Islam et al. 2017).

Most of the chitin and chitosan biological properties are directly related to their physicochemical characteristics. These characteristics include degree of deacetylation, molecular mass, and the amount of moisture content (Aranaz et al. 2009). For example, chitosan-mediated inhibition of fungal and bacterial growth relies on the functional groups and molecular weight of chitosan. Two theories have been proposed for chitosan antimicrobial activity. The first theory relays on molecular weight; the smaller oligomeric chitosan can easily penetrate the cellular membrane and prevents the cell growth by inhibiting RNA transcription (Klaykruayat et al. 2010). The second relays on the polycationic nature of chitosan which changes the cellular permeability and induce the leakage of intracellular components due to interaction with anionic components of the cell membrane leading to cell death (Lim and Hudson 2004). Moreover, chitosan may disrupt the microbial cell physiological activities by absorbing the electronegative substrate, e.g., proteins, and finally death of cells (Zheng and Zhu 2003). The distribution of acetyl groups and the length of polymer chain in chitin and chitosan affect their biodegradation kinetics (Zhang and Neau 2001). It has been reported that chitosan with a high degree of deacetylation (97.5%) has a higher positive charge density compared to the moderate DD (83.7%), thus confers a stronger antibacterial activity (Kong et al. 2010).

The chitin poor solubility is the main limiting factor in its utilization. On the other hand, chitosan is considered as a potential biopolymer due to its free amino groups that contribute polycationic, chelating activity, and dispersion forming properties along with its solubility in dilute acetic acid (Akila 2014). Due to its exceptional versatile biological, chemical, and physical properties, chitosan can be used in a wide variety of applications including industrial, agricultural, medical and pharmaceutical.

Industrial applications

In industry, chitosan found many applications in various areas including biotechnology, e.g., enzyme immobilization, cosmetics, paper production, textile, semi-permeable membranes, wastewater treatment, and food processing (Bashar and Khan 2013).

Agricultural applications

Chitin and chitosan are potent agents that inhibit the growth of bacterial and fungal plant pathogens, consequently, elicit defense reactions in higher plants (Shibuya and Mimami 2001). In bell pepper fruit pathogen, chitosan has the ability to effectively reduce Botrytis cinerea polygalacturonases causing severe cytological damages to the invading hyphae (Glaouth et al. 1997). Similarly, spraying chitosan or chitin on the surface of cucumber plants before the inoculation with the pathogen B. cinerea, the activity of peroxidase and chitosanase increased causing inhibition of B. cinerea (Ben-Shalom et al. 2003). Furthermore, a Brazilian patent by Stamford and co-worker (Stamford et al. 2015) was published describing the successful application of fungal chitosan as a biofertilizer (Batista et al. 2018).

Biomedical and pharmaceutical applications

Chitin and chitosan biopolymers are considered as useful non-toxic and biocompatible materials to be used in various medical devices to treat, augment, or replace tissues, organs, or function of the body. Furthermore, chitosan and its derivatives are promising materials for supporting in tissue engineering applications (Islam et al. 2017). Chitosan serves as a potential material for nerve regeneration, wound-healing management products and wound dressing, burn treatment, cancer treatment, artificial kidney membrane, bioartificial liver (BAL), artificial skin, artificial tendon, articular cartilage, drug delivery systems, e.g., carrier in case of vaccine delivery or gene therapy, blood anticoagulation, bone damage, and antimicrobial applications. Moreover, chitosan has antioxidant, antitumor, antidiabetic, and antiulcer activities. It is provided as dietary supplements, under several proprietary names, in combination with other substances for weight loss (Candlish 1999). It has been sold to inhibit fat absorption in Japan and Europe as a nonprescription product (Akila 2014). Glucosamine (GlcN), chitosan hydrolysate, is an amino monosaccharide that has been reported to have the potential to prevent changes in the joint structure in patients with osteoarthritis (Reginster et al. 2001; Richy et al. 2003). Chitin is considered as a promising treatment for umbilical hernia (Islam et al. 2017).

Fungal chitin and chitosan

Historical background

Chitin was first isolated from some types of fungi, i.e., Agaricus volvaceus, Agaricus acris, Agaricus cantarellus, Agaricus piperatus, Hydnum repandum, Hydnum hybridum, and Boletus viscidus, by Braconnot (1811). During the nineteenth century, Odier succeeded in production and isolation of chitin and chitosan from the cuticle of insects and from mushrooms (Odier 1823). Rouget (1859) was initially described the presence of an amine grouping at position (C-2) and determined the characteristics of chitosan formation (Novak et al. 2003). The name of chitosan was first proposed by Hoppe-Seyler (1894).

Chitosan isolation from fungal mycelium was first developed by the scientist White et al. (1979), followed by several other researches to develop adaptations for improving the process efficiency (Rane and Hoover 1993; Crestini et al. 1996; Synowiecki and Al-Khateeb 1997). Based on these studies, Hu and colleages (1999) developed an extraction protocol for fungal chitosan. This protocol describes steps for successful cultivation and extraction (Hu et al. 1999).

The synthesis of chitosan in the cell wall of fungi was first described by Araki and Ito (1974) in Mucor rouxii (Zygomycetes). This process takes place due to the activity of chitin deacetylase enzyme (EC 3.5.1.41) which catalyzes bioconversion of chitin residues in the fungal cell wall (Batista et al. 2018). This discovery was the start for other researchers to analyze the walls and confirm the presence of chitosan in many fungal species (Kendra et al. 1989; Sudarshan et al. 1992; Synowiecki and Al-Khateeb 1997).

Features of fungal chitin and chitosan production

During the last few years, the industrial production of chitin and chitosan from fungal sources has attracted the attention of many countries due to their significant advantages over the currently applied processes. The following Table 1 summarized the major advantages of chitin and chitosan production from fungal mycelia over crustacean sources (Knorr et al. 1989; Rane and Hoover 1993; Teng et al. 2001; Adams 2004).

In addition to the above-mentioned differences between chitin and chitosan production from fungal mycelia and crustacean sources, it has been reported that the degree of acetylation, molecular weight, and distribution of charged groups in fungal chitin and chitosan are potentially different from that of crustacean source which enhances bioactivity and promotes their functional properties (Wu et al. 2004). However, further researches are required to get the most economical way for obtaining the chitinous material from fungal mycelia.

The production of chitin and chitosan from fungi has a significant role in lowering the expenses involved in managing fungal-based waste materials in parallel with production of value-added products which may provide a profitable solution to the biotechnological industries (Wu et al. 2005). The worldwide production of the mushroom, Agaricus bisporus, results in about 50,000 metric tons/year of useless waste material. On the other hand, the production of citric acid from Aspergillus niger results in approximately 80,000 tons/year of mycelial waste materials (Ali et al. 2002). These fungal wastes and others represent a free natural source of chitin and chitosan.

Physiological function of fungal chitin and chitosan

Generally, the fungal cell walls are composed of chitin, chitosan, neutral polysaccharides, and glycoproteins in addition to minor amounts of polyuronides, galactosamine polymers, lipids, and melanin (Wu et al. 2004). Chitin exists in the spores and hyphal cell walls in conjunction with glucan molecules forming microfibrils. These microfibrils are embedded in an amorphous matrix to provide the framework and cell wall morphology and rigidity. Chitosan is not considered as native to animal sources; meanwhile, it presents in some fungal species such as Mucor, Absidia, and Rhizopus as one of the structural components in their cell wall (Ruiz-Herrera 1992). Chitin and chitosan are thought to increase the cell wall integrity and strength and provide protection against foreign materials, e.g., cell inhibitors and higher temperatures to which fungal cells may be subjected (Adams 2004; Banks et al. 2005; Baker et al. 2007). Chitin and chitosan represented other functions as revealed by mutants bearing a defect in the complex machinery of chitin biosynthesis, deposition of the polysaccharide in cell walls, or intracellular trafficking of chitin synthases (Specht et al. 1996).

Biosynthesis of chitin and chitosan

Glycogen is the starting material for chitin synthesis. The first step is the catalysis of glycogen by phosphorylase enzyme where glycogen is converted to glucose-1-phosphate. In the presence of phosphomutase, glucose-6-P is formed and further converted to fructose-6-P by hexokinase. Fructose-6-phosphate is then converted to N-acetyl glucosamine which involves amination (glutamine to glutamic acid) and acetylation (acetyl CoA to CoA). Isomerization step is as follows (phosphate transfer to C6 to C1 catalyzed by a phospho-N-acetyl glucosamine mutase). Further inter-conversion, uridine diphosphate (UDP) N-acetyl glucosamine is formed by utilization of uridine triphosphate (UTP). Finally, chitin is formed from UDP N-acetyl glucosamine in the presence of chitin synthase. Chitin deacetylation results in chitosan. Chitin deacetylation in the cell wall of fungi is catalyzed by the chitin deacetylase enzyme (EC 3.5.1.41) (Batista et al. 2018). Biosynthetic pathway of chitin is graphically represented in Fig. 3.

Biosynthesis of chitin (Balaji et al. 2018)

Chitin and chitosan-producing fungi

The cell walls and septa of many fungal species belong to the classes Basidiomycetes, Ascomycetes, Zygomycetes, and Deuteromycetes contain, mainly, chitin to maintain their strength, shape, and integrity of cell structure (Kirk et al. 2008). Chitin is considered as the second most abundant polymer in the fungal cell wall. Also, chitosan can be easily recovered from these microorganisms (Synowiecki and Al-Khateeb 1997; Yokoi et al. 1998). These fungal classes include Absidia coerulea, Absidia glauca, Absidia blakesleeana, Mucor rouxii, Aspergillus niger, Phycomyces blakesleeanus, Trichoderma reesei, Colletotrichum lindemuthianum, Gongronella butleri, Pleurotus sajo-caju, Rhizopus oryzae, and Lentinus edodes which have been investigated for chitin and chitosan production (Hu et al. 1999; Teng et al. 2001; Chatterjee et al. 2005) and suggested as an alternative sources to crustaceans (Nwe et al. 2002; Pochanavanich and Suntornsuk 2002; Suntornsuk et al. 2002). The amount of chitin in the fungal cell wall is specific to species, environmental conditions, and age. The chitin content in the dry fungal cell wall may vary from 2 to 42% in yeast and Euascomycetes, respectively. Chitosan is also one of the structural components in the fungal cell walls which differ depending on fungal taxonomy. Thus, the cell wall in Zygomycetes contains chitosan-glucan complex, while contains chitin-glucan in Euascomycetes, Homobasidiomycetes, and Deuteromycetes (Ruiz-Herrera 1992).

Among the investigated species, M. rouxii of the Zygomycetes class was the most researched and studied since the quantities of chitin and chitosan in its cell wall reached 35% of the dry weight (Wu 2004). Chitosan has been mostly studied, produced, and characterized in Absidia and Mucor (Pochanavanich and Suntornsuk 2002). However, A. niger (produced from citric acid industry) and Agaricus bisporus, as waste materials, provide a plenty source of raw materials for chitin and chitosan production (Wu 2004). The chitin content in Agaricus cell walls has been reported to be 13.3 to 17.3%, 35%, 20 to 38%, and 43%. This broad range of chitin concentrations can be attributed to the fact that chitin content varies, significantly, during the mushroom life-cycle as well as during postharvest storage (Wu et al. 2004).

Fermentation systems of fungal chitin and chitosan

The content of chitin and chitosan within fungal species can vary depending on the method of fungal cultivation and fermentation system. Two types of fermentation systems can be differentiated: solid-state fermentation (SSF) and submerged fermentation (SmF), both of which can be used for production of chitin and chitosan from fungi. In solid-state fermentation, the microbial growth takes place on moist solid substrates where no free water flowing (Pandey et al. 2000; Gabiatti Jr. et al. 2006). On the other hand, submerged fermentation takes place in liquid medium.

Generally, the production of chitin and chitosan in the cell walls of fungal systems are associated with the fungus biomass concentration. Focusing on biomass concentration difference, and subsequently chitin and chitosan concentration, due to the different cultivations technique, it was shown that SSF of the fungus, Lentinus edodes, yielded a greater biomass concentration (up to 50 times), after 12 days of incubation, than that of SmF (Crestini et al. 1996).

There are many reports that confirm that SSF is more efficient in fungal biomass production compared with SmF. However, there are some cases in which the biomass production in SmF exceeds that of SSF. Biomass production by Pleurotus ostreatus was compared through SSF and SmF in a study by Mazumder et al. (2009). The results showed no significant difference between biomass concentrations in both techniques during the initial growth period. However, after 2 days of growth, SmF produced a higher biomass concentration of P. ostreatus. From these studies of fermentation systems, it can be concluded that it is difficult to derive a solid comparison between solid-state and submerged fermentations in terms of biomass concentration. In other way, the suitable fermentation system for chitin and chitosan production is specific to species. The main variation in chitin and chitosan productivity arises due to changes in substrate, environmental conditions and medium composition, etc. (Bhargav et al. 2008). The substrate in case of SSF can be homogenous (e.g., polyurethane foam (PUF)) or heterogeneous (e.g., rice bran, wheat straw, soybean, or other agricultural byproducts). The use of homogenous substrate is advantageous as it allows the control of oxygen transfer, feed rate, medium composition, and facilitates the quantification of fungal biomass. On the other hand, the difficulty of fungal biomass measurement is a major hindrance of using SSF or more specifically the heterogeneous substrate (Zhu et al. 1994; Sparringa and Owens 1999). In brief, the characterization, optimization, and standardization of SSF process is very difficult. The substrate’s physical properties, strongly, affect the rate of oxygen and nutrients diffusion, water activity, and consequently metabolic activity. The difficulty of recovering fungal biomass in case of SSF affects the extraction process of chitin and chitosan. These conditions push toward the use of SmF instead of SSF (Sitanggang et al. 2012). The simple step for determination of the fungal biomass in SmF makes this fermentation system preferred for production of chitin and chitosan. However, the higher probability of contamination, if the aseptic conditions are not maintained, the production of much waste water after biomass recovery, and high energy expenditure during the agitation for adequate mixing are the major obstructions in the use of SmF (Sitanggang et al. 2012).

Factors affecting fungal chitin and chitosan production

The quantity and/or quality of chitin and chitosan in the fungal cell wall may change due to environmental and nutritional conditions and the intrinsic characteristics of producing species (Campos-Takaki et al. 1983; Ruiz-Herrera 2012). Many researchers aim to maximize the yield of fungal chitin and chitosan as well as minimize the production costs to be able to compete commercially with those obtained from crustacean’s shell (Batista et al. 2018). Based on the mechanism of their biosynthesis in fungal cells, several factors were proposed to affect chitin and chitosan production by submerged culture. These factors are not only important for production, but for manipulation of physicochemical characteristics, also (Tanaka 2001; Jaworska and Konieczna 2001; Chatterjee et al. 2005; Chatterjee et al. 2008; Neves et al. 2013). These factors ultimately influence the metabolic activity of fungi through catabolic repression (Solís-Pereira et al. 1993; de Azeredo et al. 2007). For enhancing the growth of fungal mycelium and biopolymers productivity, many researchers tried to supplement additional nutrient sources to the traditional fermentation medium.

The effect of urea has been demonstrated by Nwe and Stevens (2004) showing a significant increase in total chitosan production by the fungal species Gongronella butleri. The addition of urea as a nitrogen source not only resulted in an elevated amount of chitosan, but resulted in differences in chitosan molecular weight, as well. Mishra and Kumar (2007) examined the effects of different N-sources; i.e., yeast extract, urea, ammonium sulfate, and dry cyanobacterial biomass of Anacystis nidulans on Pleurotus ostreatus and reported greatest recovery of the biopolymer in the presence of cyanobacterial biomass due to its high nutritional value.

Benjamin and Pandey (1997) used coconut oil cake (COC) as a substrate and examined different minerals, nitrogen, and carbon sources on Candida rugosa. This study involved optimization of N- and C-sources and combining the optimum parameters. The effect of different carbon sources, i.e., glucose, sucrose, or galacturonic acid with pectin, on the production of fungal biomass by A. niger was studied by Solís-Pereira and co-workers (1993) under SmF. The addition of such supplemental carbon sources showed increased biomass concentrations.

Besides the use of additional N- and C-sources, the effects of treating solid substrates with ethanol, phosphate, or acid and conditioning at different moisture contents on biomass content by A. niger have been explored. Xie and West (2009) showed that the treatment of the solid substrate with acid demonstrated a significant increasing the biomass concentration.

Exploration of the effect of plant growth hormones indicated a significant improvement in the mycelium growth of fungi in SmF. Chatterjee et al. (2008) demonstrated the effects of kinetin, auxins, and gibberellic acid on the production of chitosan by M. rouxii and R. oryzae in molasses-salt medium and whey medium, respectively. The low concentrations of these plant hormones caused an increase in both chitosan content and mycelia growth in R. oryzae and M. rouxii. However, at higher concentrations of plant hormone, the growth in both aspects was inhibited. In addition, the molecular weight of extracted chitosan was increased (Chatterjee et al. 2008, 2009).

It has been reported that for obtaining the maximum yield of chitin and chitosan, fungi should be harvested at their late exponential growth phase (Akila 2014).

Optimization of the factors affecting fungal chitin and chitosan production

The medium composition and environmental conditions play critical role in industrial microbial cultivation process due to their major influences on the final yield of a particular culture’s end product (Basri et al. 2007; Bibhu et al. 2007). In biotechnology, two approaches are applied for optimization of the variable factors in the bioprocesses; one-factor-at-a-time (OFAT) or “one-variable-at-a-time” and statistical or mathematical design of experiment (DOE) (Singh et al. 2011). The last one may be differentiated into factorial design or response surface methods.

-

One-factor-at-a-time (OFAT) approach: it is the conventional method used to optimize nutritional and environmental factors by changing one factor each time while keeping the other factors constant. This approach is simple and easy to understand by nonprofessionals. However, it is time consuming, laborious, and ignores the factor-factor interactions among different variables (Vishwanatha et al. 2010).

-

Statistical/mathematical approach: it is a useful technique used for simultaneous study of the effect of several variables. It is a collection of mathematical and statistical tools that is powerful in both fundamental research and applied research and development (Almquist et al. 2014). It became an indispensible tool in bioprocess design, simulation, and optimization (Kiparissides et al. 2011). This approach requires less number of experiments, equipments, and financials. In addition, the data obtained from this approach is much more reliable, understandable, can be used for prediction and simulation, and allow for evaluation of the interactions among variables (Singh et al. 2011; Nor et al. 2017).

Industrial biotechnology can benefit from mathematical models by using them to understand, predict, and optimize the properties and behavior of cell factories (Tyo et al. 2010). With valid models, improvement strategies can be discovered and evaluated in silico, saving both time and resources. Figure 4 summarizes the scenario for successful modeling of biological process. This scenario involves the following steps (Wang 2012):

-

Step 1: Identification of the problem; ask the questions: it is to define the purpose of the model. Typical questions are: Why do we model? What do we want to use the model for? What type of behavior should the model be able to explain?

-

Step 2: Post assumptions; select the modeling approach: it is to determine the mathematical expressions that define the interactions between the different components.

-

Step 3: Define the variables and formulate the model: when the network structure and the mathematical expressions have been determined, the structure of the model is complete. The model can now be written as a set of equations.

-

Step 4: Analyze and simulate the model: next to formulation of the model, the numerical values of the parameters should be determined.

-

Step 5: Validate the model with real phenomena: it is to determine the quality of the model.

-

Step 6: Apply the model and answer the questions: when a model has been established it can be used in a number of different ways to answer the questions for why it was created.

-

Step 7: Calibrate and extend the model.

Summary of the statistical procedures used to analyze the results from DOE (Granato and Calado 2014)

During the recent years, a new trend for co-production of multiple value-added products has been emerged to lower the process cost and to be able to compete with the chemical processes (Abo Elsoud et al. 2017). Coproduction of chitin and fumaric acid by R. oryzae has been explored by Liao et al. (2008). In addition, R. oryzae was reported for its ability to produce lactic acid in parallel with chitin. Biomass and gamma linolenic acid (GLA) production by M. rouxii was investigated by Jangbua et al. (2009) using different substrates and spore concentrations. Citric acid, lactic acid, oxalic acid, and alcohol were also studied in a co-production process with chitin from various fungal sources (Sumbali 2005). The optimization of a co-production process is very complicated; therefore, the use of traditional methods, in this case, is inapplicable, while statistical methods are going to be beneficial and give steady and reliable results.

Conclusion

Chitin and chitosan are magic natural biopolymers that exist in the shells of crustaceans, exoskeletons of insects and mollusks, as well as in the cell walls of fungi. Industrially, they are produced from the shells of crustaceans and found many applications in many industries, agriculture, and biomedicine. However, due to the inconsistent structure of chitin and chitosan from crustacean origin, the fungal origins represent suitable alternative, especially, for biomedical and pharmaceutical applications. Chitin and chitosan production from fungal sources relieves the world from a great amount of biological wastes. The quantity and/or quality of chitin and chitosan in the fungal cell wall may change due to environmental and nutritional conditions. Optimization of these conditions is better performed by statistical methods because the data obtained from this approach is much more reliable, understandable, can be used for prediction and simulation, and allow for evaluation of the interactions among different variables.

References

Abo Elsoud MM, Elkhouly HI, Sidkey NM (2017) Optimization of multiple valuable biogenic products using experimental design. J Innovations Pharm Biol Sci 4(4):32–38

Adams DJ (2004) Fungal cell wall chitinases and glucanases. Microbiology 150(1):2029–2035

Akila RM (2014) Fermentative production of fungal chitosan, a versatile biopolymer (perspectives and its applications). Adv Appl Sci Res 5(4):157–170

Ali S, Haq I-u, Qadeer MA, Iqbal J (2002) Production of citric acid by Aspergillus niger using cane molasses in a stirred fermentor. Electron J Biotechnol 5(3):1-4

Almquist J, Cvijovic M, Hatzimanikatis V, Nielsen J, Jirstrand M (2014) Kinetic models in industrial biotechnology—improving cell factory performance, Minireview. Metab Eng 24:38–60

Amorim RVS, Melo ES, Carneiro-da-Cunha MG, Ledingham WM, Campos-Takaki GM (2003) Chitosan from Syncephalastrum racemosum used as a film support for lípase immobilization. Bioresour Technol 89(1):35–39

Araki Y, Ito E (1974) A pathway of chitosan formation in Mucor rouxii. Enzymatic deacetylation of chitin. Eur J Biochem 55(1):71–78

Aranaz I, Mengibar M, Harris R, Panos I, Miralles B, Acosta N, Gemma G, Heras A (2009) Functional characterization of chitin and chitosan. Curr Chem Biol 3(2):203–230

Ashford NA, Hattis D, Murray AE (1977) Industrial prospects for chitin and protein from shellfish wastes. MIT Sea Grant Program. Report no. MITSG 77–3, Index no. 77–703-Zle. Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge

Baker LG, Specht CA, Donlin MJ, Lodge JK (2007) Chitosan, the Deacetylated form of chitin, is necessary for cell wall integrity in Cryptococcus neoformans. Eukaryot Cell 6(5):855–867

Balaji AB, Pakalapati H, Khalid M, Walvekar R, Siddiqui H (2018) Natural and synthetic biocompatible and biodegradable polymers. In: Shimpi NG (ed) Biodegradable and Biocompatible Polymer Composites Processing, Properties and Applications. Ohio: Woodhead Publishing, pp 3–32

Banks IR, Specht CA, Donlin MJ, Gerik KJ, Levitz SM, Lodge JK (2005) A chitin synthase and its regulator protein are critical for chitosan production and growth of the fungal pathogen Cryptococcus neoformans. Eukaryot Cell 4(11):1902–1912

Bashar MM, Khan MA (2013) An overview on surface modification of cotton fiber for apparel use. J Polym Environ 21(1):181–190

Basri M, RNZRA Rahman A, Ebrahimpour AB, Salleh ERG, Abd Rahman MB (2007) Comparison of estimation capabilities of response surface methodology (RSM) with artificial neural network (ANN) in lipase-catalyzed synthesis of palm-based wax ester. BMC Biotechnol 7:53

Batista ACL, Souza Neto FE, Paiva WS (2018) Review of fungal chitosan: past, present and perspectives in Brazil. Polímeros 28(3):275–283

Benjamin S, Pandey A (1997) Coconut cake—a potent substrate for the production of lipase by Candida rugosa in solid-state fermentation. Acta Biotechnol 3:241–251

Ben-Shalom N, Ardi R, Pinto R, Aki C, Fallik E (2003) Controlling gray mould caused by Botrytis cinerea in cucumber plants by means of chitosan. Crop Prot 22:285–290

Bhargav S, Panda BP, Ali M, Javed S (2008) Solid-state fermentation: an overview. Chem Biochem Eng Q 22:49–70

Bhuiyan MAR, Shaid A, Khan MA (2014) Cationization of cotton fiber by chitosan and its dyeing with reactive dye without salt. Chem Mater Eng 2:96–100

Bhuiyan MR, Shaid A, Bashar MM, Haque P, Hannan MA (2013) A novel approach of dyeing jute fiber with reactive dye after treating with chitosan. Open J Org Polym Mater 3(4):87–91

Bibhu PP, Ali M, Salem J (2007) Fermentation process optimization. Res J Microbiol 2:201–208

Braconnot H (1811) Sur la nature des champignons. Ann Chim Phys 79:265–304

Brugnerotto J, Lizardi J, Goycoolea FM, Monal WA, Desbrieres J, Rinaudo M (2001) An infrared investigation in relation with chitin and chitosan characterization. Polymer. 42:3569–3580

Cai J, Yang J, Du Y, Fan L, Qui Y, Li J, Kennedy JF (2006) Enzymatic preparation of chitosan from the waste Aspergillus niger mycelium of citric acid production plant. Carbohydr Polym 64:151–157

Campos-Takaki GM, Beakes GW, Dietrich SM (1983) Electron microscopic X-ray microprobe and cytochemical study of isolated cell walls of mucoralean fungi. Trans Br Mycol Soc 80(3):536–541

Candlish JK (1999) What you need to know: over the counter slimming products—their rationality and legality. Singap Med J 40:550–552

Chatterjee S, Adhya M, Guha AK, Chatterjee BP (2005) Chitosan from Mucor rouxii production and physico-chemical characterization. Process Biochem 40:395–400

Chatterjee S, Chatterjee S, Chatterjee BP, Guha AK (2008) Enhancement of growth and chitosan production by Rhizopus oryzae in whey medium by plant growth hormones. Int J Biol Macromol 42(2):120–126

Chatterjee S, Chatterjee S, Chatterjee BP, Guha AK (2009) Influence of plant growth hormones on the growth of Mucor rouxii and chitosan production. Microbiol Res 164:347–351

Chien R, Yen M, Mau J (2016) Antimicrobial and antitumor activities of chitosan from shiitak estipes, compared to commercial chitosan from crab shells. Carbohydr Polym 138(1):259–264

Crestini C, Kovac B, Giovannozzi-Sermanni G (1996) Production and isolation of chitosan by submerged and solidstate fermentation from Lentinus edodes. Biotechnol Bioeng 50(2):207–210

Croisier F, Jérôme C (2013) Chitosan-based biomaterials for tissue engineering. Eur Polym J 49(4):780–792

de Azeredo LAI, Gomes PM Jr, Sant’Anna GL, Castilho LR, Freire DMG (2007) Production and regulation of lipase activity from Penicillium restrictum in submerged and solid-state fermentations. Curr Microbiol 54:361–365

Duarte ML, Ferreira MC, Marvao MR, Rocha J (2001) Determination of the degree of acetylation of chitin materials by 13C CP/MAS NMR spectroscopy. Int J Boil Macromol. 28:359–363

Duarte ML, Ferreira MC, Marvao MR, Rocha J (2002) An optimized method to determine the degree of acetylation of chitin and chitosan by FTIR spectroscopy. Int J Boil Macromol 31:1–8

Franco LO, Maia RCC, Porto ALF, Messias AS, Fukushima K, Campos-Takaki GM (2004) Heavy metal biosorption by chitin and chitosan isolated from Cunninghamella elegans (IFM 46109). Braz J Microbiol 35(3):243–247

Gabiatti C Jr, Vendruscolo F, Piaia JCZ, Rodrigues RC, Durrant LR, Costa JAV (2006) Radial growth rate as a tool for the selection of filamentous fungi for use in bioremediation. Braz Arch Biol Technol 49:29–34

Glaouth EA, Arul J, Wilson C, Benhamor N (1997) Biochemical and cytochemical aspects of the interactions of chitosan and Botrytis cinerea in bell pepper fruit. Postharvest Biol Tec 12:183–194

Granato D, Calado VMA (2014) The use and importance of design of experiments (DOE) in process modelling in food science and technology. In: Granato D, Ares G (eds) Mathematical and Statistical Methods in Food Science and Technology, 1st edn. USA: Wiley

Han Z, Zeng Y, Lu H, Zhang L (2015) Determination of the degree of acetylation and the distribution of acetyl groups in chitosan by HPLC analysis of nitrous acid degraded and PMP labeled products. Carbohydr Res 413(2):75–84

Hoppe-Seyler F (1894) Ueber chitosan und zellulose. Ber. Deutsche Chemische Gesellschaft, Germany

Hu KJ, Yeung KW, Ho KP, Hu JL (1999) Rapid extraction of high-quality chitosan from mycelia of Absidia glauca. J Food Biochem 23(2):187–196

Islam S, Bhuiyan MAR, Islam MN (2017) Chitin and chitosan: structure, properties and applications in biomedical engineering. J Polym Environ 25:854–866

Jangbua P, Laoteng K, Kitsubun P, Nopharatana M, Tongta A (2009) Gamma-linolenic acid production of Mucor rouxii by solid-state fermentation using agricultural by-products. Appl Microbiol 49:91–97

Jaworska MM, Konieczna E (2001) The influence of supplemental components in nutrient medium on chitosan formation by the fungus Absidia orchidis. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 56(1–2):220–224

Kasaai MR (2009) Various methods for determination of the degree of N-acetylation of chitin and chitosan: a review. J Agric Food Chem 57(5):1667–1676

Ke HZ, Chen QZ (1990) Potentiometric titration of chitosan by linear method. Huaxue Tongbao 10:44–46

Kendra DF, Christian D, Hadwiger LA (1989) Chitosan oligomers from Fusarium solani/pea interactions, chitinase/ßglucanase digestion of sporelings and from fungal wall chitin actively inhibit fungal growth and enhance disease resistance. Physiol Mol Plant Pathol 35(3):215–230

Kim SK, Rajapakse N (2005) Enzymatic production and biological activities of chitosan oligosaccharides (COS): a review. Carbohydr Polym 62(4):357–368

Kiparissides A, Koutinas M, Kontoravdi C, Mantalaris A, Pistikopoulos EN (2011) ‘Closing the loop’ in biological systems modeling—from the in silico to the in vitro. Automatica 47:1147–1155

Kirk PM, Cannon PF, Minter DW, Stalpers JA (eds) (2008) Dictionary of the Fungi, 10th edn. CAB International, Wallingford

Klaykruayat B, Siralertmukul K, Srikulkit K (2010) Chemical modification of chitosan with cationic hyperbranched dendritic polyamidoamine and its antimicrobial activity on cotton fabric. Carbohydr Polym 80(1):197–207

Knorr D (1984) Use of chitinous polymer in food –a challenge for food research and development. Food Technol 38:85–97

Knorr D, Beaumont MD, Pandya Y (1989) Potential of acid soluble and water soluble chitosan in biotechnology. In: SkjakBrack G, Anthonsen T, Stanford P (eds) Chitin and chitosan. Elsevier Appl. Sci, London, New York, pp 101–118

Kong M, Chen XG, Xing K, Park HJ (2010) Antimicrobial properties of chitosan and mode of action: a state of the art review. Int J Food Microbiol 144(1):51–63

Kumar MNR (2000) A review of chitin and chitosan applications. React Funct Polym 46(1):1–27

Kurita K (2001) Controlled functionalization of polysaccharide chitin. Prog Polym Sci 26(9):1921–1971

Liao W, Liu Y, Frear C, Chen S (2008) Coproduction of fumaric acid and chitin from a nitrogen rich lignocellulosic material-dairy manure–using a pelletized filamentous fungus Rhizopus oryzae ATC 20344. Bioresour Technol 99:5859–5866

Lim SH, Hudson SM (2004) Synthesis and antimicrobial activity of a water-soluble chitosan derivative with a fiber-reactive group. Carbohydr Res 339(2):313–319

Liu D, Weia Y, Yao P, Jiang L (2006) Determination of the degree of acetylation of chitosan by UV spectrophotometry using dual standards. Carbohydr Res 341(6):782–785

Mazumder S, Basu SK, Mukherjee M (2009) Laccase production in solid-state and submerged fermentation by Pleurotus ostreatus. Eng Life Sci 9(1):45–52

Mima M, Mima S, Miya M, Iwamoto R, Yoshikawa S (1983) Highly deacetylated chitosan and its properties. J Appl Polym Sci 28(6):1909–1917

Mishra A, Kumar S (2007) Cyanobacterial biomass as N-supplement to agro-waste for hyper-production of laccase from Pleurotus ostreatus in solid state fermentation. Process Biochem 42:681–685

Moussa SH, Tayel AA, Al-Turki IA (2013) Evaluation of fungal chitosan as a biocontrol and antibacterial agent using fluorescence-labeling. Int J Biol Macromol 54:204–208

Neves AC, Schaffner RA, Kugelmeier CL, Wiest AM, Arantes MK (2013) Otimização de processos de obtenção de quitosana a partir de resíduo da carcinicultura para aplicações ambientais. Rev Bras de Energias Renováveis 2(1):34–47

No HK, Meyers SP (1995) Preparation and characterization of chitin and chitosan—a review. J Aquat Food Prod Technol 4(2):27–52

Nor NM, Mohamed MS, Loh TC, Foo HL, Abdul Rahim R, Tan JS, Mohamad R (2017) Comparative analyses on medium optimization using one-factor-at-a-time, response surface methodology and artificial neural network for lysine– methionine biosynthesis by Pediococcus pentosaceus RF-1. Biotechnol Biotechnol Equip 31(5):935–947

Novak K, Cupp MJ, Tracy TS (2003) Chitosan. In: Cupp MJ, Tracy TS (eds) Dietary supplements: toxicology and clinical pharmacology. Humana Press, Totowa

Nwe N, Chandrkrachang S, Stevens WF, Maw T, Tan TK, Khor E, Wong SM (2002) Production of fungal chitosan by solid state and submerged fermentation. Carbohyd Polym 49:235–237

Nwe N, Stevens WF (2004) Effect of urea on fungal chitosan production in solid substrate fermentation. Process Biochem 39:1639–1642

Odier A (1823) Mémoir sur la composition chimique des parties cornées des insectes. Mémoirs de la Societé d’Histoire Naturelle, vol 1, pp 29–42

Oliveira CEV, Magnani M, Sales CV, Pontes ALS, Campos-Takaki GM, Stamford TCM, Souza EL (2014) Effects of chitosan from Cunninghamella elegans on virulence of post-harvest pathogenic fungi in table grapes (Vitis labrusca L.). Int J Food Microbiol 171:54–61

Pandey A, Soccol C, Mitchell D (2000) Mitchell new developments in solid state fermentation: I-bioprocess and products. Process Biochem 35(10):1153–1169

Pochanavanich P, Suntornsuk W (2002) Fungal chitosan production and its characterization. Lett Appl Microbiol 35:17–21

Rane KD, Hoover DG (1993) Production of chitosan by fungi. Food Biotechnol 7(1):11–33

Reginster JV, Deroisy R, Rovati LC, Lee RL, Lejeune E, Bruyere O, Giacovelli G, Henrotin Y, Dacre JE, Gossett C (2001) Long-term effects of glucosamine sulphate on osteoarthritis progression: a randomised, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Lancet 357:251–256

Richy F, Bruyere O, Ethgen O, Cucherate M, Reginster JY (2003) Structural and symptomatic efficacy of glucosamine and chondroitin in knee osteoarthritis. Arch Int Med 163:1514–1522

Roberts GAF (1992) Chitin chemistry. Macmillan Press Ltd, London

Ruiz-Herrera J (1992) Fungal cell walls: structure, synthesis, and assembly. CRC Press Inc., Boca Raton, Florida

Ruiz-Herrera, J., 2012. Fungal cell wall: estructure, synthesis, and assembly. In J. Ruiz-Herrera (Ed.), Current topics in medical mycology (3, 168–217). New York: Springer

Sbrana C, Avio L, Giovannetti M (1995) The occurrence of calcofluor and lectin binding polysaccharides in the outer wall of AM fungal spores. Mycol Res 99:1249–1252

Shibuya N, Mimami E (2001) Oligosaccharide signaling for defense responses in plant. Physiol Mol Plant P 59:223–233

Singh SK, Singh SK, Tripathi VR, Khare SK, Garg SK (2011) Comparative one-factor-at-a-time, response surface (statistical) and bench-scale bioreactor level optimization of thermoalkaline protease production from a psychrotrophic Pseudomonas putida SKG-1 isolate. Microb Cell Factories 10:114

Sitanggang AB, Sophia L, Wu HS (2012) MiniReview: aspects of glucosamine production using microorganisms. Int Food Res J 19(2):393–404

Solís-Pereira S, Favela-Torres E, Viniegra-González G, Gutierrez-Rojas M (1993) Effects of different carbon sources on the synthesis of pectinase by Aspergillus niger in submerged and solid state fermentations. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 39:36–41

Sorlier P, Denuziere A, Viton C, Domard A (2001) Relation between the degree of acetylation and the electrostatic properties of chitin and chitosan. Biomacromolecules. 2:765–772

Sparringa RA, Owens JD (1999) Glucosamine content of tempe mould Rhizopus oligosporous. Int J Food Microbiol 47:153–157

Specht CA, Liu Y, Robbins PW, Bulawa CE, Iartchouk N, Winter KR, Riggle PJ, Rhodes JC, Dodge CL, Culp DW, Borgia PT (1996) The chsD and chsE genes of Aspergillus nidulans and their roles in chitin synthesis. Fungal Genet Biol 20:153–167

Stamford, N. P., C. E. R. S. Santos, T. C. M. Stamford, L. C. Franco and T. M. S. Arnaud, 2015. BR 10 2013 003043 0. Rio de Janeiro: INPI. Retrieved in 2016, July 15, from http://www.scielo.br/pdf/po/v28n3/0104-1428-po-0104-142808316.pdf

Sudarshan NR, Hoover DG, Knorr D (1992) Antibacterial action of chitosan. Food Biotechnol 6(3):257–272

Sumbali G (2005) The Fungi. Alpha Science International Ltd, United Kingdom, pp 86–168

Suntornsuk W, Pochanavanich P, Suntornsuk L (2002) Fungal chitosan production on food processing by-products. Process Biochem 37:727–729

Synowiecki J, Al-Khateeb NAA (2003) Production, properties, and some new applications of chitin and its derivatives. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 43:145–171

Synowiecki J, Al-Khateeb NAAQ (1997) Mycelia of Mucor rouxii as a source of chitin and chitosan. Food Chem 60(4):605–610

Tajdini F, Amini MA, Nafissi-Varcheh N, Faramarzi MA (2010) Production, physiochemical and antimicrobial properties of fungal chitosan from Rhizomucor miehei and Mucor racemosus. Int J Biol Macromol 47(2):180–183

Tan H, Chu CR, Payne KA, Marra KG (2009) Injectable in situ forming biodegradable chitosan-hyaluronic acid based hydrogels for cartilage tissue engineering. Biomaterials 30(13):2499–2506

Tanaka H (2001) Scale-up for fermentative production. Kyoritu Shuppan, Japão

Teng WL, Khor E, Tan TK, Lim LY, Tan SL (2001) Concurrent production of chitin from shrimp shells and fungi. Carbohydr Res 332:305–316

Tharanathan RN, Kittur FS (2003) Chitin—the undisputed biomolecular of great potential. Crit Rev Food Sci 43:61–87

Tyo KEJ, Kocharin K, Nielsen J (2010) Toward design-based engineering of industrial microbes. Curr Opin Microbiol 13:255–262

Valdivieso HM, Duran A, Roncero C (1999) Chitin synthases in yeast and fungi. EXS 87:55–69

Vishwanatha KS, Rao AGA, Singh SA (2010) Acid protease production by solid-state fermentation using Aspergillus oryzae MTCC 5341: optimization of process parameters. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol 37:129–138

Wang H (2012) Mathematical modeling I-preliminary. Bookboon ebook publisher, London. ISBN: 978-87-403-0248-6

White SA, Farina PR, Fulton I (1979) Production and isolation of chitosan from Mucor rouxii. Appl Environ Microbiol 38(2):323–328

Wu T (2004) "Production and characterization of fungal chitin and chitosan" Master's Thesis. Tennessee: University of Tennessee

Wu T, Zivanovic S, Draughon FA, Conway WS, Sams CE (2005) Physicochemical properties and bioactivity of fungal chitin and chitosan. J Agric Food Chem 53(10):3888–3894

Wu T, Zivanovic S, Draughon FA, Sams CE (2004) Chitin and chitosan—value-added products from mushroom waste. J Agric Food Chem 52(26):7905–7910

Xie G, West TP (2009) Citric acid production by Aspergillus niger ATCC 9142 from a treated ethanol fermentation co-production using solid-state fermentation. Lett Appl Microbiology 48:639–644

Yeul VS, Rayalu SS (2013) Unprecedented chitin and chitosan: a chemical overview. J Polym Environ 21(2):606–614

Yokoi H, Aratake T, Nishio S, Hirose J, Hayashi S, Takasaki Y (1998) Chitosan production from Shochu distillery wastewater by funguses. J Ferment Bioeng 85:246–249

Zamani A, Jeihanipour A, Edebo L, Niklasson C, Taherzadeh MJ (2008) Determination of glucosamine and N-acetyl glucosamine in fungal cell walls. J Agric Food Chemistry 56:8314–8318

Zhang H, Neau SH (2001) In vitro degradation of chitosan by a commercial enzyme preparation: effect of molecular weight and degree of deacetylation. Biomaterials 22(12):1653–1658

Zheng LY, Zhu JF (2003) Study on antimicrobial activity of chitosan with different molecular weights. Carbohydr Polym 54:527–530

Zhu Y, Knol W, Smits JP, Bol J (1994) A novel solid-state fermentation system using polyurethane foam as inert carrier. Biotechnol Lett 16:643–648

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the National Research Centre (NRC) and members of Microbial Biotechnology Department for the kind incorporeal support.

Funding

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

All information and data included in this study are included in this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The manuscript was compiled and edited by MMAE and was kindly revised by Prof. Dr. EMEK. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Abo Elsoud, M.M., El Kady, E.M. Current trends in fungal biosynthesis of chitin and chitosan. Bull Natl Res Cent 43, 59 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s42269-019-0105-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s42269-019-0105-y