Abstract

We study the achievements of quantum circuits comprised of several one- and two-qubit gates subject to dissipation and dephasing. Quantum process matrices are determined for the basic one- and two-qubit gate operations and concatenated to yield the process matrix of the combined quantum circuit. Examples are given of process matrices obtained by a Monte Carlo wavefunction analysis of Rydberg blockade gates in neutral atoms. Our analysis is ideally suited to compare different implementations of the same process. In particular, we show that the three-qubit Toffoli gate facilitated by the simultaneous interaction between all atoms may be accomplished with higher fidelity than a concatenation of one- and two-qubit gates.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Since the first proposals were made to use quantum effects for computing purposes there has been a strong focus on how errors and imperfections may harm and even prevent successful application of quantum computing. A simple estimate suggests that if each single operation in a computation entails an error with a probability  then the application of k operations will lead to a useful outcome with a probability that decreases exponentially

then the application of k operations will lead to a useful outcome with a probability that decreases exponentially  . Error correction codes have provided a way to correct these errors up to a certain probability threshold, thereby allowing scalable, fault-tolerant quantum computing [1, 2].

. Error correction codes have provided a way to correct these errors up to a certain probability threshold, thereby allowing scalable, fault-tolerant quantum computing [1, 2].

The errors occurring in a single computational step such as a one- or two-qubit gates are often characterized by a single number, typically related to the overlap between the desired and actual output state, averaged over all input states. There is no guarantee, however, that such a number encapsulates the accumulation of errors in a quantum circuit, where the output state of one operation serves as the input to the next. Errors may build up coherently, so that error probabilities grow quadratically rather than linearly with time, or so that they compensate each other, cf., bang-bang control and composite pulses [3–5]. Thus, a concatenation of two imperfect gates can lead to either unusable results or a correcting mechanism.

Consider the action of a quantum process that takes an input density matrix ρ describing a physical system with Hilbert space dimension D to an output density matrix. Such a process is described as a completely-positive linear map  , where

, where  can be written [6]

can be written [6]

by introducing a complete basis of  operators

operators  on the Hilbert space. The coefficients

on the Hilbert space. The coefficients  constitute the process matrix χ.

constitute the process matrix χ.

In quantum computing we aim to implement definite gate operations yielding, ideally, a unitary transformation,  . Expanding

. Expanding  , this corresponds to Eq. (1) with

, this corresponds to Eq. (1) with  . The process matrix of an experimental gate implementation differs from this form due to dissipation and decoherence. In this article, we will show that, provided dissipation and decoherence acts locally and is uncorrelated over the quantum computing register χ-matrices calculated once for one- and two-qubit gates can be concatenated, see Figure 1, to characterize circuits built from many of these gates. This assumption may be well justified in our example, which concerns neutral atom quantum computing, where the Rydberg blockade mechanism is used for two-qubit quantum gates [7, 8].

. The process matrix of an experimental gate implementation differs from this form due to dissipation and decoherence. In this article, we will show that, provided dissipation and decoherence acts locally and is uncorrelated over the quantum computing register χ-matrices calculated once for one- and two-qubit gates can be concatenated, see Figure 1, to characterize circuits built from many of these gates. This assumption may be well justified in our example, which concerns neutral atom quantum computing, where the Rydberg blockade mechanism is used for two-qubit quantum gates [7, 8].

The paper is organized as follows. In Section 2, we review the definition of χ-matrices and how they may be computed with Monte Carlo wave function simulations. In Section 3, we describe how χ-matrices for simple processes on few particles are concatenated to characterize large quantum circuits. In Section 4, we introduce the Rydberg blockade gate scheme for quantum computing with neutral atoms. In Section 5, we concatenate one- and two-qubit gate χ-matrices in a neutral atom system to characterize the circuit performing a Toffoli gate. This we compare to a direct multi-atom Rydberg mediated implementation. In Section 6, we conclude and present an outlook.

2 Process matrix identification

Many techniques now exist to experimentally determine χ. Standard quantum process tomography [6, 9, 10] successfully reproduces χ by measuring all output states via quantum state tomography [11, 12]. This has been demonstrated in NMR [13, 14], optical [15, 16], and atomic systems [17]. Alternately, χ may be obtained making use of an ancillary system [18, 19] or avoiding state tomography altogether through the use of suitable ‘probe’ systems [20–22].

If the system is subject to known dissipation and decoherence mechanisms, the quantum system evolution may be modeled theoretically and the process matrix be calculated by solution of the quantum master equation. A gate operation typically involves application of time dependent laser pulses. Therefore, it is valuable to determine how losses and errors accumulate and contribute to different types of errors in the output. To theoretically characterize a complete quantum circuit is a formidable task and is ultimately at odds with using a physical system to solve computationally hard problems. Still, a theoretical analysis of how errors propagate and accumulate in small systems may guide efforts to pick among different implementations of gates and assess optimal strategies for error correction. Such detailed studies may also serve to confirm the values of experimental parameters [23, 24].

In a recent publication [25], we described how to characterize a quantum controlled-phase gate subject to decay and dephasing. Instead of simulating the evolution of a complete set of  input states we gain access to all elements of χ by evolving a single maximally entangled pure state of the system and an idle ancilla system of the same Hilbert space dimension [18]. The system is propagated stochastically using the Monte Carlo wave function method, which on average reproduces results of a master equation evolution [26–28]. Process characterization using this approach has a number of advantages: First, for large D, an adequate ensemble of wave functions is easier to store and evolve than density matrices. Second, obtaining χ through the output state data from an ensemble of wave functions is less costly, numerically, than from a density matrix [25]. Third, the stochastic evolution consists of a deterministic smooth evolution interrupted by ‘quantum jumps’. Since useful quantum gates require excellent fidelity, jumps are rare and a single deterministic ‘no-jump’ wave function suffices to provide a good estimate and rigorous bound on the process matrices describing the evolution [25].

input states we gain access to all elements of χ by evolving a single maximally entangled pure state of the system and an idle ancilla system of the same Hilbert space dimension [18]. The system is propagated stochastically using the Monte Carlo wave function method, which on average reproduces results of a master equation evolution [26–28]. Process characterization using this approach has a number of advantages: First, for large D, an adequate ensemble of wave functions is easier to store and evolve than density matrices. Second, obtaining χ through the output state data from an ensemble of wave functions is less costly, numerically, than from a density matrix [25]. Third, the stochastic evolution consists of a deterministic smooth evolution interrupted by ‘quantum jumps’. Since useful quantum gates require excellent fidelity, jumps are rare and a single deterministic ‘no-jump’ wave function suffices to provide a good estimate and rigorous bound on the process matrices describing the evolution [25].

3 The process matrix for a quantum circuit

Suppose the quantum circuit performing a computational task is composed of N physical units. The Hilbert space of the entire system is then a tensor product of N Hilbert spaces, each of dimension d. An implementation of a quantum process often requires using more than just the qubit states. However, since the physical units only process binary information we shall refer to them as qubits, even if we exploit states from a space larger than dimension 2. On each qubit Hilbert space we assume the complete operator basis  . By merely forming tensor products of the basis operators, we obtain a complete operator basis

. By merely forming tensor products of the basis operators, we obtain a complete operator basis  for the N qubits, where the single index n represents all values of the set

for the N qubits, where the single index n represents all values of the set  . The operator tensor product structure provides a convenient representation of the

. The operator tensor product structure provides a convenient representation of the  operators

operators  (

( ) in Eq. (1).

) in Eq. (1).

If we assume that process matrices χ correctly describe processes acting separately on one and two qubits of the circuit, then the application of several one- and two-qubit operations is exactly represented by an appropriate concatenation of the corresponding process matrices.

3.1 Parallel concatenation

Suppose two subsystems are simultaneously subjected to processes independent of each other. These processes  and

and  may be described by the process matrices

may be described by the process matrices  and

and  respectively, illustrated as two- and one-qubit gates in Figure 1(a). The combined three-qubit process matrix

respectively, illustrated as two- and one-qubit gates in Figure 1(a). The combined three-qubit process matrix  is simply the tensor product of the independent χ matrices. Other systems may be present but idle during the gate operation. They are then represented by the identity operator in the process matrix tensor product.

is simply the tensor product of the independent χ matrices. Other systems may be present but idle during the gate operation. They are then represented by the identity operator in the process matrix tensor product.

3.2 Serial concatenation

Most quantum algorithms make use of many computational steps, where the output of every step serves as the input to the subsequent one. In Figure 1(b) we illustrate this situation for two consecutive three-qubit operations  and

and  characterized by

characterized by  and

and  respectively. If the output

respectively. If the output  of the input density matrix ρ becomes the input of

of the input density matrix ρ becomes the input of  , what is the resulting χ matrix? Formally, the output of the sequential application of the operations is given by

, what is the resulting χ matrix? Formally, the output of the sequential application of the operations is given by

Since the operators  form a complete set, any product

form a complete set, any product  can be expanded on these operators, that is,

can be expanded on these operators, that is,  and

and  . Equation (2) then becomes

. Equation (2) then becomes

where

Note that although two consecutive processes may act on different subsets of some multi-qubit system both operations may be reformulated to act on the entire system through parallel concatenation.

It now becomes apparent that once the process matrices of all contributing gates in a circuit have been computed conclusively, we limit the cost of finding  and thus of process matrices for larger quantum circuits. The assessment of how errors accumulate becomes a function of the width and depth of the quantum circuit.

and thus of process matrices for larger quantum circuits. The assessment of how errors accumulate becomes a function of the width and depth of the quantum circuit.

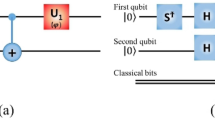

3.3 Example: Toffoli gate

The Toffoli gate, or C2NOT gate, performs a controlled NOT operation on a target qubit based on the state of two control qubits. The Toffoli gate may be implemented as a sequence of six two-qubit C-NOT gates and nine one-qubit Hadamard and  and

and  phase gates, see Figure 2(a). The gate and its generalization to higher numbers of control qubits (C

k

-NOT) have applications as sub-modules in different quantum computing algorithms. Thus, it is relevant to determine the process matrix for its implementation in realistic systems.

phase gates, see Figure 2(a). The gate and its generalization to higher numbers of control qubits (C

k

-NOT) have applications as sub-modules in different quantum computing algorithms. Thus, it is relevant to determine the process matrix for its implementation in realistic systems.

The Toffoli gate:

(a) The three-qubit Toffoli gate on the left may be reproduced by a circuit of C-NOT, Hadamard (H),  and

and  gates, shown to the right. (b) The process matrix χ (left), characterizing the Toffoli gate may be calculated by concatenation of one- and two-qubit process matrices (right). The process matrices

gates, shown to the right. (b) The process matrix χ (left), characterizing the Toffoli gate may be calculated by concatenation of one- and two-qubit process matrices (right). The process matrices  ,

,  ,

,  and

and  characterize the C-NOT, Hadamard, T and

characterize the C-NOT, Hadamard, T and  gates respectively. The ‘identity’ process matrix

gates respectively. The ‘identity’ process matrix  indicates an idle qubit.

indicates an idle qubit.

In the analysis of the Toffoli gate process matrix we first simulated the propagation of quantum states in the full three-qubit Hilbert space through the sequence of one- and two-qubit gates. Such a calculation, e.g. using Monte Carlo wave functions to include dissipation, yields the full circuit process matrix  . Next, we apply the concatenation rules to obtain the circuit’s process matrix

. Next, we apply the concatenation rules to obtain the circuit’s process matrix  . Its repeated use of the same C-NOT χ matrix (cf. Figure 2(b)), which only needs a single calculation on a two-qubit system, attests to the advantage of the latter approach.

. Its repeated use of the same C-NOT χ matrix (cf. Figure 2(b)), which only needs a single calculation on a two-qubit system, attests to the advantage of the latter approach.

4 Rydberg blockade quantum gates

A promising candidate for quantum computing involves neutral atoms held at closely spaced sites in far-off-resonance optical traps. The atoms may be individually addressed with laser fields and excited into high lying Rydberg states that feature strong, long distance dipole and van der Waals forces that can be used to mediate two-qubit interactions [7, 8, 29].

In Rubidium atoms, a convenient choice for the qubit states are the hyperfine ground states  and

and  . They can be selectively excited to the Rydberg state

. They can be selectively excited to the Rydberg state  by a two photon process using a 780-nm (480-nm) laser field, tuned by an amount Δ to the red (blue) of the intermediate

by a two photon process using a 780-nm (480-nm) laser field, tuned by an amount Δ to the red (blue) of the intermediate  state. The Rabi frequency associated with the red (blue) detuned laser is

state. The Rabi frequency associated with the red (blue) detuned laser is  (

( ), illustrated in Figure 3(a). An atom that achieves excitation to the Rydberg state shifts the

), illustrated in Figure 3(a). An atom that achieves excitation to the Rydberg state shifts the  state energy of all other atoms within the so-called blockade radius by an amount ℬ. Thus, one excited atom can prevent the resonant excitation of its neighboring atoms and this is the basis for effective quantum gates between them.

state energy of all other atoms within the so-called blockade radius by an amount ℬ. Thus, one excited atom can prevent the resonant excitation of its neighboring atoms and this is the basis for effective quantum gates between them.

Simulation and characterization of the C-NOT gate:

(a) The red (lower) and blue (upper) laser fields drive  , via

, via  , into the Rydberg state

, into the Rydberg state  by two-photon absorption. (b) Implementation of the C-NOT gate involves a sequence of two-photon π-pulses: In pulse 1 the control atom makes the transition

by two-photon absorption. (b) Implementation of the C-NOT gate involves a sequence of two-photon π-pulses: In pulse 1 the control atom makes the transition  to

to  . The target atom then makes the transitions

. The target atom then makes the transitions  (pulse 2),

(pulse 2),  (pulse 3) and finally

(pulse 3) and finally  (pulse 4). In pulses 2-4 the target atom’s states

(pulse 4). In pulses 2-4 the target atom’s states  and

and  are swapped, but only if the control atom is not in

are swapped, but only if the control atom is not in  . Finally, in pulse 5 the control atom is driven from

. Finally, in pulse 5 the control atom is driven from  back to

back to  . (c) Trace distance (see text in Section 4.1) between the ideal C-NOT process matrix and the process matrix calculated for the implementation shown in panel (b), with the parameters listed in Table 1. The trace distance is shown as a function of the blue laser Rabi frequency

. (c) Trace distance (see text in Section 4.1) between the ideal C-NOT process matrix and the process matrix calculated for the implementation shown in panel (b), with the parameters listed in Table 1. The trace distance is shown as a function of the blue laser Rabi frequency  .

.

Dephasing of the Rydberg level normally associated with magnetic field noise and atomic motion is modeled by the operator  , where

, where  is the dephasing rate and

is the dephasing rate and  is shorthand for the identity operator. Spontaneous decay from a state

is shorthand for the identity operator. Spontaneous decay from a state  to a lower lying state

to a lower lying state  at a rate

at a rate  is modeled by the jump operator

is modeled by the jump operator  . The effects of both dissipation mechanisms are simulated using the Monte Carlo wave function method [25]. Characteristic parameters are summarized in Table 1.

. The effects of both dissipation mechanisms are simulated using the Monte Carlo wave function method [25]. Characteristic parameters are summarized in Table 1.

Adiabatic elimination by the effective operator formalism detailed in Ref. [32] provides a mechanism to decouple the intermediate optically excited state and describe the coherent and incoherent dynamics within the subspace of  and

and  . The system is then described by a Hamiltonian coupling a selected qubit state to

. The system is then described by a Hamiltonian coupling a selected qubit state to  by an effective Rabi frequency. The formalism also provides an effective form for the operators describing decohering processes [25].

by an effective Rabi frequency. The formalism also provides an effective form for the operators describing decohering processes [25].

4.1 Rydberg blockade C-NOT gate

In atomic quantum computing proposals, single qubit gates amount to fast, resonant transitions within single atoms and can be made with high precision. Thus, for the purpose of this study we assume that the χ matrices associated with one-qubit gates are identical to the desired ones. The two-qubit C-NOT gate depends on finite interactions between excited state atoms, lengthening gate time and making it prone to dissipation and decoherence.

Figure 3(b) illustrates how a unitary C-NOT gate between two atoms can be implemented by a sequence of five perfect π-pulses. First transferring the control qubit’s population from  to

to  (pulse 1), then transferring the target qubit’s population between

(pulse 1), then transferring the target qubit’s population between  and

and  via the state

via the state  (pulses 2-4) and finally returning the control qubit’s population from

(pulses 2-4) and finally returning the control qubit’s population from  to

to  (pulse 5). If the control qubit initially populates the state

(pulse 5). If the control qubit initially populates the state  the Rydberg blockade prevents any transfer during pulses 2-4. Thus, a NOT operation on the target qubit is conditioned on the control qubit initially populating the state

the Rydberg blockade prevents any transfer during pulses 2-4. Thus, a NOT operation on the target qubit is conditioned on the control qubit initially populating the state  , defining it to be a C-NOT operation.

, defining it to be a C-NOT operation.

Monte Carlo wave functions were used to simulate the five π-pulse implementation of the C-NOT gate (Figure 3) with the parameters of Table 1. The performance of the gate was investigated as a function of the blue laser Rabi frequency  . To provide a simple quantitative measure we applied the trace distance measure

. To provide a simple quantitative measure we applied the trace distance measure  between the simulated and ideal process matrix, where

between the simulated and ideal process matrix, where  and

and  is the trace norm. Note that this distance measure is less ‘forgiving’ than, for example, measures based on the trace overlap [23]. In Figure 3(c) we show the trace distance between a simulated C-NOT gate process matrix and the ideal, unitary process matrix. At low values of

is the trace norm. Note that this distance measure is less ‘forgiving’ than, for example, measures based on the trace overlap [23]. In Figure 3(c) we show the trace distance between a simulated C-NOT gate process matrix and the ideal, unitary process matrix. At low values of  the gate experiences greater dephasing errors from population in the Rydberg state, due to long gate times. At large

the gate experiences greater dephasing errors from population in the Rydberg state, due to long gate times. At large  the blockade mechanism becomes inefficient. Thus, the optimum Rabi frequency lies between these two regimes.

the blockade mechanism becomes inefficient. Thus, the optimum Rabi frequency lies between these two regimes.

5 The Toffoli gate by Rydberg blockade

We demonstrate the characterization of the Toffoli gate resulting from simulation in Figure 4. The process matrix  of the Toffoli gate in the circuit implementation (Figure 2) may be obtained without further simulation by a concatenation of the single qubit process matrices and the C-NOT process matrix of Section 4.1. Alternatively, we may simulate the circuit implementation in the full three-qubit Hilbert space to obtain

of the Toffoli gate in the circuit implementation (Figure 2) may be obtained without further simulation by a concatenation of the single qubit process matrices and the C-NOT process matrix of Section 4.1. Alternatively, we may simulate the circuit implementation in the full three-qubit Hilbert space to obtain  . In the simulation of a Rydberg mediated gate, the characterization of a single qubit has a Hilbert space dimension of

. In the simulation of a Rydberg mediated gate, the characterization of a single qubit has a Hilbert space dimension of  , which translates into a 46 problem for the three qubit circuit characterization. We observe that the Toffoli gate consists of six C-NOT gates and the trace distance to the ideal gate is, indeed, roughly six times the one shown in Figure 3(c).

, which translates into a 46 problem for the three qubit circuit characterization. We observe that the Toffoli gate consists of six C-NOT gates and the trace distance to the ideal gate is, indeed, roughly six times the one shown in Figure 3(c).

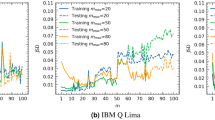

Trace distance between the process matrix

for the ideal Toffoli gate and the process matrices for Rydberg interaction implementations subject to dissipation and decoherence. The results are shown as a function of the Rabi frequency

for the ideal Toffoli gate and the process matrices for Rydberg interaction implementations subject to dissipation and decoherence. The results are shown as a function of the Rabi frequency  of the

of the  (blue) laser coupling. The dashed curve is obtained by simulating all three qubits as they evolve under the sequence of gates in the Toffoli circuit shown in Figure 2(a). The top solid curve uses concatenation of the one- and two-qubit process matrices to compute the Toffoli circuit process matrix. The bottom (solid) curve results from simulating the multi-qubit implementation shown in Figure 5. In all calculations 500 Monte Carlo trajectories were used with the parameters listed in Table 1.

(blue) laser coupling. The dashed curve is obtained by simulating all three qubits as they evolve under the sequence of gates in the Toffoli circuit shown in Figure 2(a). The top solid curve uses concatenation of the one- and two-qubit process matrices to compute the Toffoli circuit process matrix. The bottom (solid) curve results from simulating the multi-qubit implementation shown in Figure 5. In all calculations 500 Monte Carlo trajectories were used with the parameters listed in Table 1.

The top dashed (solid) curve in Figure 4 illustrates trace distance between the full circuit  (concatenated

(concatenated  ) process matrix to the ideal process matrix

) process matrix to the ideal process matrix  , plotted as a function of

, plotted as a function of  . Since the decay and decoherence processes apply to the individual atoms, the successive treatment of the evolution of the atoms acted upon by the laser fields and concatenation of the resulting one- and two-qubit process matrices should yield the same results as the solution on the full-register Hilbert space.

. Since the decay and decoherence processes apply to the individual atoms, the successive treatment of the evolution of the atoms acted upon by the laser fields and concatenation of the resulting one- and two-qubit process matrices should yield the same results as the solution on the full-register Hilbert space.

Each point in both curves is determined by propagating  wave function trajectories, and the minor discrepancy between the two curves is due to the use of the MCWF method. The final number of propagated wave functions imposes a statistical error

wave function trajectories, and the minor discrepancy between the two curves is due to the use of the MCWF method. The final number of propagated wave functions imposes a statistical error  on both curves. Furthermore, it imposes a small systematical error in the construction of

on both curves. Furthermore, it imposes a small systematical error in the construction of  , because the same simulated C-NOT process matrix is applied several times to form the concatenated process matrix (see Ref. [33] for an analysis of a similar situation). The discrepancy between the curves in Figure 4 depends on

, because the same simulated C-NOT process matrix is applied several times to form the concatenated process matrix (see Ref. [33] for an analysis of a similar situation). The discrepancy between the curves in Figure 4 depends on  . For low values of

. For low values of  , and thus slow gate operation, decay and dephasing dominate the error. More random quantum jumps occur and the resulting scattering of Monte Carlo wave functions explains the relatively large discrepancy between

, and thus slow gate operation, decay and dephasing dominate the error. More random quantum jumps occur and the resulting scattering of Monte Carlo wave functions explains the relatively large discrepancy between  and

and  . For high values of

. For high values of  , imperfect blockade dominates the gate error. This corresponds to a unitary term in the state evolution which is well represented by a single wave function, and the discrepancy between

, imperfect blockade dominates the gate error. This corresponds to a unitary term in the state evolution which is well represented by a single wave function, and the discrepancy between  and

and  decreases for large

decreases for large  .

.

A Rydberg excited atom blocks excitation of any number of atoms within the Rydberg interaction blockade radius, which may be of order 10 μm. Thus, it is possible to contain an entire qubit register within a single blockade radius, allowing implementation of multi-qubit gate operations which are faster than the circuit equivalent [34]. One such protocol is the C k NOT gate operation, illustrated in Figure 5 [35].

Multi-qubit Rydberg blockade implementation of a

NOT gate. Each control atom is sequentially excited from

NOT gate. Each control atom is sequentially excited from  to

to  in k

π-pulses. Next, the target atom qubit states are swapped as in Figure 3(b), via the Rydberg state

in k

π-pulses. Next, the target atom qubit states are swapped as in Figure 3(b), via the Rydberg state  (conditioned on no control atom populating the state

(conditioned on no control atom populating the state  ). The control atoms are then returned to their original state in reverse order. The trace distance between the process matrix using this implementation for

). The control atoms are then returned to their original state in reverse order. The trace distance between the process matrix using this implementation for  and the ideal Toffoli gate is shown as the lower curve in Figure 4.

and the ideal Toffoli gate is shown as the lower curve in Figure 4.

For  the gate becomes the Toffoli gate and calculation of the process matrix is only possible by solving the master equation for the complete qubit register. In this paper, simulation of the process, including the decay and decoherence mechanisms detailed above, was carried out using the Monte Carlo method. The trace distance between the process matrix resulting from simulation and the ideal process matrix is shown as the lower, black curve in Figure 4. Remarkably, the multi-qubit implementation, with interactions allowed between all three atoms, performs markedly better than the Toffoli circuit consisting of one- and two-qubit operations. In comparison with the C-NOT gate, the minimal trace distance here is approximately 1.5 times larger. This is consistent with using 7 π-pulses rather than the 5 needed for a single C-NOT gate.

the gate becomes the Toffoli gate and calculation of the process matrix is only possible by solving the master equation for the complete qubit register. In this paper, simulation of the process, including the decay and decoherence mechanisms detailed above, was carried out using the Monte Carlo method. The trace distance between the process matrix resulting from simulation and the ideal process matrix is shown as the lower, black curve in Figure 4. Remarkably, the multi-qubit implementation, with interactions allowed between all three atoms, performs markedly better than the Toffoli circuit consisting of one- and two-qubit operations. In comparison with the C-NOT gate, the minimal trace distance here is approximately 1.5 times larger. This is consistent with using 7 π-pulses rather than the 5 needed for a single C-NOT gate.

6 Conclusion

In conclusion, we have presented an efficient method to compute the accumulation of errors in quantum circuits comprised of several few-qubit gates. We have shown that a set of concatenation rules on the appropriate few-qubit gate process matrices is enough to reproduce the process matrix of the entire circuit. To demonstrate the method’s efficiency at calculating process matrices of large systems we considered the three-qubit Toffoli gate. The Toffoli gate may be implemented as a circuit of one- and two-qubit gates and simulations show that the process matrix obtained via concatenation is in good agreement with the result achieved by propagation through the entire circuit.

Our theory allows comparison of different implementations of gates. In particular, we compared a multi-qubit implementation of the Toffoli gate with its one- and two-qubit circuit implementation. For the parameters chosen, the factor determining gate fidelity was the number of laser π-pulses. More gates lead to a lower fidelity, with a dependence that is almost linear. In this way, our analysis provides the necessary information to choose between different gate implementations. A theory of full error correction may benefit significantly from knowledge of the precise nature of errors incurred, potentially leading to higher thresholds for errors that can be remedied by appropriate error correction. The full process matrix, which remains at our disposal, may be further applied to optimally combine the Toffoli gate with previous and subsequent gate operations along the lines of NMR composite pulses [4].

Our analysis quantifies how erroneous states prepared by one gate are the input states to the subsequent ones and how the resulting accumulation of errors cause the full register quantum state to stray away from the ideal unitary evolution. The calculations assumed a quantum optical master equation with independent Lindblad type relaxation terms. This is well justified for Rydberg blockade quantum computing with optical excitation of neutral atoms, but it also applies for a number of quantum computing proposals with similarly isolated and identifiable qubits. However, if the deleterious interaction between the quantum register and its environment is subject to correlations between qubits and non-Markovian effects, more care must be exercised in the assessment of how errors accumulate, and how they may be corrected [36, 37].

References

Calderbank AR, Shor PW: Good quantum error-correcting codes exist. Phys Rev A 1996, 54:1098–1105. 10.1103/PhysRevA.54.1098

Steane A: Multiple-particle interference and quantum error correction. Proc R Soc Lond A 1996, 452:2551–2577. 10.1098/rspa.1996.0136

Viola L, Lloyd S: Dynamical suppression of decoherence in two-state quantum systems. Phys Rev A 1998, 58:2733–2744. 10.1103/PhysRevA.58.2733

Levitt MH: Composite pulses. Prog Nucl Magn Reson Spectrosc 1986, 18:61–122. 10.1016/0079-6565(86)80005-X

Jones JA: Designing short robust NOT gates for quantum computation. Phys Rev A 2013., 87: Article ID 052317

Chuang IL, Nielsen MA: Prescription for experimental determination of the dynamics of a quantum black box. J Mod Opt 1997,44(11–12):2455–2467. 10.1080/09500349708231894

Jaksch D, Cirac JI, Zoller P, Rolston SL, Côté R, Lukin MD: Fast quantum gates for neutral atoms. Phys Rev Lett 2000, 85:2208–2211. 10.1103/PhysRevLett.85.2208

Saffman M, Walker TG, Mølmer K: Quantum information with Rydberg atoms. Rev Mod Phys 2010, 82:2313–2363. 10.1103/RevModPhys.82.2313

Nielsen MA, Chuang IL: Quantum computation and quantum information. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge; 2010.

Poyatos JF, Cirac JI, Zoller P: Complete characterization of a quantum process: the two-bit quantum gate. Phys Rev Lett 1997, 78:390–393. 10.1103/PhysRevLett.78.390

Gross D, Liu Y-K, Flammia ST, Becker S, Eisert J: Quantum state tomography via compressed sensing. Phys Rev Lett 2010., 105: Article ID 150401

D’Ariano GM, Maccone L, Paini M: Spin tomography. J Opt B 2003, 5:77–84. 10.1088/1464-4266/5/1/311

Childs AM, Chuang IL, Leung DW: Realization of quantum process tomography in NMR. Phys Rev A 2001., 64: Article ID 012314

Boulant N, Havel TF, Pravia MA, Cory DG: Robust method for estimating the Lindblad operators of a dissipative quantum process from measurements of the density operator at multiple time points. Phys Rev A 2003., 67: Article ID 042322

Mitchell MW, Ellenor CW, Schneider S, Steinberg AM: Diagnosis, prescription, and prognosis of a Bell-state filter by quantum process tomography. Phys Rev Lett 2003., 91: Article ID 120402

O’Brien JL, Pryde GJ, Gilchrist A, James DFV, Langford NK, Ralph TC, White AG: Quantum process tomography of a controlled-NOT gate. Phys Rev Lett 2004., 93: Article ID 080502

Myrskog SH, Fox JK, Mitchell MW, Steinberg AM: Quantum process tomography on vibrational states of atoms in an optical lattice. Phys Rev A 2005., 72: Article ID 013615

D’Ariano GM, Lo Presti P: Quantum tomography for measuring experimentally the matrix elements of an arbitrary quantum operation. Phys Rev Lett 2001, 86:4195–4198. 10.1103/PhysRevLett.86.4195

Altepeter JB, Branning D, Jeffrey E, Wei TC, Kwiat PG, Thew RT, O’Brien JL, Nielsen MA, White AG: Ancilla-assisted quantum process tomography. Phys Rev Lett 2003., 90: Article ID 193601

Mohseni M, Lidar DA: Direct characterization of quantum dynamics. Phys Rev Lett 2006., 97: Article ID 170501

Mohseni M, Lidar DA: Direct characterization of quantum dynamics: general theory. Phys Rev A 2007., 75: Article ID 062331

Wang Z-W, Zhang Y-S, Huang Y-F, Ren X-F, Guo G-C: Experimental realization of direct characterization of quantum dynamics. Phys Rev A 2007., 75: Article ID 044304

Zhang XL, Gill AT, Isenhower L, Walker TG, Saffman M: Fidelity of a Rydberg-blockade quantum gate from simulated quantum process tomography. Phys Rev A 2012., 85: Article ID 042310

Weinstein YS, Havel TF, Emerson J, Boulant N, Saraceno M, Lloyd S, Cory DG: Quantum process tomography of the quantum Fourier transform. J Chem Phys 2004,121(13):6117–6133. 10.1063/1.1785151

Gulliksen J, Bhaktavatsala Rao DD, Mølmer K: Process characterization with Monte Carlo wave functions. Phys Rev A 2013., 88: Article ID 052129

Dalibard J, Castin Y, Mølmer K: Wave-function approach to dissipative processes in quantum optics. Phys Rev Lett 1992, 68:580–583. 10.1103/PhysRevLett.68.580

Mølmer K, Castin Y, Dalibard J: Monte Carlo wave-function method in quantum optics. J Opt Soc Am B 1993,10(3):524–538. 10.1364/JOSAB.10.000524

Dum R, Zoller P, Ritsch H: Monte Carlo simulation of the atomic master equation for spontaneous emission. Phys Rev A 1992, 45:4879–4887. 10.1103/PhysRevA.45.4879

Saffman M, Walker TG: Analysis of a quantum logic device based on dipole-dipole interactions of optically trapped Rydberg atoms. Phys Rev A 2005., 72: Article ID 022347

Johnson TA, Urban E, Henage T, Isenhower L, Yavuz DD, Walker TG, Saffman M: Rabi oscillations between ground and Rydberg states with dipole-dipole atomic interactions. Phys Rev Lett 2008., 100: Article ID 113003

Saffman M, Zhang X, Gill A, Isenhower L, Walker T: Rydberg state mediated quantum gates and entanglement of pairs of neutral atoms. J Phys Conf Ser 2011., 264: Article ID 012023

Reiter F, Sørensen AS: Effective operator formalism for open quantum systems. Phys Rev A 2012., 85: Article ID 032111

Castin Y, Mølmer K: Monte Carlo wave functions and nonlinear master equations. Phys Rev A 1996, 54:5275–5290. 10.1103/PhysRevA.54.5275

Mølmer K, Isenhower L, Saffman M: Efficient Grover search with Rydberg blockade. J Phys B 2011.,44(18): Article ID 184016

Isenhower L, Saffman M, Mølmer K:Multibit

NOT quantum gates via Rydberg blockade.

Quantum Inf Process 2011, 10:755–770. 10.1007/s11128-011-0292-4

NOT quantum gates via Rydberg blockade.

Quantum Inf Process 2011, 10:755–770. 10.1007/s11128-011-0292-4Jacobsen SH, Mintert F: Optimal correction of independent and correlated errors. J Phys A, Math Theor 2014., 47: Article ID 045306

Terhal BM, Burkard G: Fault-tolerant quantum computation for local non-Markovian noise. Phys Rev A 2005., 71: Article ID 012336

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge discussion with Mark Saffman. This work was supported by the IARPA MQCO program through ARO contract W911NF-10-1-0347 and by the Villum Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

All authors contributed to the derivation and analysis as well as to the preparation of the manuscript. JG performed the numerical simulations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

To view a copy of this licence, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gulliksen, J., Dasari, D.B.R. & Mølmer, K. Characterization of how dissipation and dephasing errors accumulate in quantum computers. EPJ Quantum Technol. 2, 4 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1140/epjqt17

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1140/epjqt17

NOT quantum gates via Rydberg blockade.

Quantum Inf Process 2011, 10:755–770. 10.1007/s11128-011-0292-4

NOT quantum gates via Rydberg blockade.

Quantum Inf Process 2011, 10:755–770. 10.1007/s11128-011-0292-4