Abstract

Optical homodyne tomography consists in reconstructing the quantum state of an optical field from repeated measurements of its amplitude at different field phases (homodyne data). The experimental noise, which unavoidably affects the homodyne data, leads to a detection efficiency \(\eta<1\). The problem of reconstructing quantum states from noisy homodyne data sets prompted an intense scientific debate about the presence or absence of a lower homodyne efficiency bound (\(\eta> 0.5\)) below which quantum features, like quantum interferences, cannot be retrieved. Here, by numerical experiments, we demonstrate that quantum interferences can be effectively reconstructed also for low homodyne detection efficiency. In particular, we address the challenging case of a Schrödinger cat state and test the minimax and adaptive Wigner function reconstruction technique by processing homodyne data distributed according to the chosen state but with an efficiency \(\eta< 0.5\). By numerically reproducing the Schrödinger’s cat interference pattern, we give evidence that quantum state reconstruction is actually possible in these conditions, and provide a guideline for handling optical tomography based on homodyne data collected by low efficiency detectors.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

The rapid development of experimental and theoretical techniques in quantum optics has made it simpler to prepare and manipulate quantum states of light [1]. Consequently, estimating the quantum state of an optical field is now an essential tool in this research field. Nowadays, optical homodyne tomography, proposed for the first time by Vogel and Risken in 1989 [2] and then experimentally demonstrated by Smithey et al. in 1993 [3], constitutes a well-established method for the reconstruction of optical quantum states with continuous variables [4]. The technique is based on two subsequent phases. The first consists in the experimental procedure known as balanced homodyne detection, while the second concerns the tomographic reconstruction, where statistical algorithms are used for retrieving the optical quantum state from the measured homodyne data. In the experimental phase, balanced homodyne detection, a single mode photon state, the signal, is mixed with a coherent reference state, the so-called local oscillator, by a \(50/50\) beam splitter. The outputs are collected by two photodiodes and the difference photocurrent is measured. It can be proved that, when the local oscillator is significantly more intense than the signal, the homodyne photocurrent is proportional to the signal quadrature [5]. The quadrature operator is defined as

where â and \(\hat{a}^{\dagger}\) denote the single mode annihilation and creation operators associated with the signal and ϕ is the relative phase between signal and local oscillator. The continuum set of quadratures with \(\phi\in[0, \pi]\) provides a complete characterization of the signal state [2, 6]. Repeated homodyne measurements on identically prepared light modes in the state ρ̂ provide an experimental histogram which approaches the probability distribution of the quadrature outcome at a fixed phase:

This represents the probability of having as outcome the eigenvalue \(x_{\phi}\) when measuring \(\hat{x}_{\phi}\). Once such histograms have been obtained for different \(\phi\in[0, \pi]\), the second phase of optical homodyne tomography starts. A tomographic mathematical procedure uses the experimental homodyne data in order to provide a complete characterization of the quantum state by reconstructing its density matrix ρ̂ or equivalently its Wigner function \(W_{\rho }\). The Wigner function, defined later, is a convenient representation of the optical quantum state as a pseudo, that is non-positive definite, distribution on phase space whose marginals exactly correspond to the quadratures probability distributions in (2).

The mathematical approaches to the quantum state reconstruction problem are divided in two main categories, the inverse linear transform techniques and the statistical inference techniques [4, 7, 8]. The first category is based on accessing the state ρ̂ by directly inverting the linear relation in (2) through back-projection algorithms [9]. The second category is instead based on looking for the most likely density matrix that generates the observed homodyne data by means of non linear algorithms like maximum likelihood estimation [10].

Here we focus on the first approach with particular attention to the problem of processing homodyne data with low detection efficiency. In detail we adopt quantum statistical methods based on minimax and adaptive estimation methods of the Wigner function [11, 12] which have been developed to intrinsically counteract the effects of detection inefficiencies. Usually, a very high detection efficiency and ad hoc designed apparatuses with low electronic noise are required [13]. However, the scientific debate about how to process homodyne data with low efficiency is of crucial importance [10–12, 14–23] towards applying optical homodyne tomography to study physical systems where high noise conditions are unavoidable [24–31]. In this context an intense discussion developed about the presence or absence of a lower homodyne efficiency bound (\(\eta= 0.5\)), under which quantum state reconstruction is not achievable [8, 11, 12, 14–17, 19, 20, 27]. In this framework, it has been mathematically demonstrated that the algorithms of minimax and adaptive estimation of the Wigner function to be used in the following allow the tomographic reconstruction of quantum states of light for any homodyne detection efficiency η, excluding the existence of a lower bound to the efficiency beyond which faithful reconstruction is impossible [11, 12]. Nevertheless the absence of a test of such algorithms for \(\eta<0.5\) could suggest that they might not be of practical use. In a precedent work [27] we tested the algorithm for the reconstruction of Gaussian states starting from homodyne data obtained with a commercially available detection apparatus associated with an efficiency of about 0.3. In that paper the discrimination between different Gaussian states (like coherent and squeezed states) has been proved. However, Gaussian states are a very special class of states characterized by Gaussian and always positive Wigner functions. This leaves open the question about whether intrinsically quantum features, like quantum interferences (characterized by negative portions of the Wigner function), can be retrieved in low efficiency conditions or whether they would be made practically invisible by optical losses. In this respect, a physically relevant example is provided by the so-called Schrödinger cat states, that is by linear superpositions of two coherent states [4]. The main challenge is to make it clear whether or not the reconstruction algorithm can distinguish the linear superposition from the statistical mixture of the constituent coherent states. Indeed, the first state exhibits purely quantum interference patterns, while they are absent in the second state. Such a challenge has so far not been taken on. In order to fill this gap, in the following we test the reconstruction algorithm by means of numerical experiments where we generate homodyne data according to the probability distribution corresponding to a given Schrödinger cat, but distorted by an independent Gaussian noise that simulates an efficiency lower than 0.5. By suitably enlarging the size of the set of numerically generated data, we are able to reconstruct the Wigner function of the linear superposition within errors that are compatible with the theoretical bounds. Our results show that the Schrödinger cat interference pattern can actually be unambiguously reconstructed even in low homodyne detection efficiency conditions, demonstrating also the concrete feasibility of the adopted tomographic approach for \(\eta<0.5\).

2 Methods

2.1 Wigner function reconstruction

Let us consider a quantum system with one degree of freedom described by the Hilbert space \(L^{2}(\mathbb{R})\) of square integrable functions \(\psi(x)\) over the real line. The most general states of such a system are density matrices ρ̂, namely convex combinations of projectors \(\vert\psi_{j}\rangle \langle \psi_{j}\vert\) onto normalized vector states

Any density matrix ρ̂ can be completely characterized by the associated Wigner function \(W_{\rho}(q,p)\) on the phase-space \((q,p)\in\mathbb{R}^{2}\); that is, by the non-positive definite (pseudo) distribution defined by

Here q̂ and p̂ are the position and momentum operators obeying the commutation relation \([\hat{q} , \hat{p}]=i\) (\(\hbar=1\)), and \(\vert q\pm v/2\rangle\) are eigenstates of q̂: \(\hat{q}\vert q\pm v/2\rangle=(q\pm v/2)\vert q\pm v/2\rangle\). Notice that \(W_{\rho}(q,p)\) is a square integrable function:

Among the advantages of such a representation is the possibility of expressing the mean value of any operator Ô with respect to a state ρ̂ as a pseudo-expectation with respect to \(W_{\rho}(q,p)\) of an associated function \(O(q,p)\) over the phase-space, where

Indeed, by direct inspection one finds

In homodyne detection experiments the collected data consist of n pairs of quadrature amplitudes and phases \((X_{\ell},\Phi_{\ell})\): these can be considered as independent, identically distributed stochastic variables. Given the probability density \(p_{\rho}(x_{\phi},\phi)\) in (2), one could reconstruct the Wigner function by substituting the integration with a sum over the pairs for a sufficiently large number of data. However, the measured values \(x_{\phi}\) are typically not the eigenvalues of \(\hat {x}_{\phi}\), but rather those of

where y is a normally distributed random variable describing the possible noise that may affect the homodyne detection data and η parametrizes the detection efficiency that increases from 0 to 100% with η increasing from 0 to 1 [12]. The noise can safely be considered Gaussian and independent from the statistical properties of the quantum state, that is y can be considered as independent from \(\hat{x}_{\phi}\). Then, as briefly summarized in Appendix A, the Wigner function is reconstructed from a given set of n measured homodyne pairs \((X_{\ell},\Phi_{\ell})\) by means of an estimator of the form [12]

where the positive constant γ is given in Eq. (25) of Appendix A. This expression is an approximation of the Wigner function in (26) of Appendix A by a sum over n homodyne pairs \((X_{\ell},\Phi_{\ell})\). The parameter h serves to control the divergent factor \(\exp(\gamma\xi^{2})\), while r, through the characteristic function \(\chi_{r}(q,p)\) of a circle \(C_{r}(0)\) of radius r around the origin, restricts the reconstruction to the points \((q,p)\) such that \(q^{2}+p^{2}\leq r^{2}\). Both parameters have to be chosen in order to minimize the reconstruction error which is conveniently measured [11] by the \(L^{2}\)-distance between the true Wigner function and the reconstructed one, \(\|W_{\rho}-W^{\eta ,r}_{h,n}\|_{2}\). Since such a distance is a function of the data through \(W^{\eta,r}_{h,n}\), the \(L^{2}\)-norm has to be averaged over different sets, M, of quadrature data:

where E denotes the average over the M data samples, each sample consisting of n quadrature pairs \((X_{\ell},\Phi_{\ell})\) corresponding to measured values of \(x_{\phi}\) with \(\phi\in[0, \pi]\). In [11], an optimal dependence of the parameters r and h upon the number of data, n, is obtained by minimizing an upper bound to \(\Delta_{h,n}^{\eta,r}(\hat{\rho})\).Footnote 1

3 Results

3.1 Interfering coherent states

Homodyne reconstruction is particularly useful to expose quantum interference effects that typically spoil the positivity of the Wigner function: it is exactly these effects that are often claimed not to be accessible by homodyne reconstruction in presence of efficiency lower than 50%, i.e. when η in (7) is smaller than 0.5 [18]. In contrast, in [12] it is theoretically shown that \(\eta<0.5\) only requires increasingly larger data sets for achieving small reconstruction errors. However, this claim was not put to test in those studies as the values of η in the considered numerical experiments were close to 1.

One major concern, often presented as a challenge to reconstruction methods in low efficiency conditions, is that they might be unable to sort out the interference pattern arising from a linear superposition of two coherent states,

with α any complex number \(\alpha_{1}+i\alpha_{2}\in\mathbb{C}\), a so-called Schrödinger cat state. Thus, in the following, we will consider an efficiency \(\eta<0.5\) and reconstruct the Wigner function of \(\hat{\rho}_{\alpha}=\vert\Psi _{\alpha}\rangle\langle\Psi_{\alpha}\vert\): its general expression together with that of its Fourier transform and of the probability distributions \(p_{\rho}(x_{\phi},\phi)\) and \(p^{\eta}_{\rho}(x_{\phi},\phi)\) are given in Appendix B. The Wigner function corresponding to the pure state \(\hat{\rho}_{\alpha}\) is shown in Figure 1.

In Appendix C, a derivation is provided of the \(L^{2}\)-errors and of the optimal dependence of h and r on the number of data n and on a parameter β that takes into account the fast decay of both the Wigner function and its Fourier transform for large values of their arguments. The following upper bound to the mean square error in (10) is derived:

with \(0<\beta<1/4\) and γ as given in (25) of Appendix A.

As explained in Appendix C, the quantities \(\Delta_{1,2,3}\) do not depend on h, r and n. By taking the derivatives with respect to r and h, one finds that the upper bound to the mean square deviation is minimized, for large n, by choosing

This relation between the various parameters of the reconstruction algorithm is the one which minimizes the theoretical upper bounds. In particular, it points to the way the estimator in (9) depends on the parameter β. If η is very small, γ diverges and \(\beta+2\gamma\simeq 2\gamma\): however, for \(\eta<1/2\) but not too small, the integration interval \([-1/h,1/h]\) shrinks with increasing β, therefore a larger β, through a smaller \(1/h\), can reduce the impact of numerical noise coming from too large an integration interval. More details on the role of β are given in Appendix C.

In order to reconstruct the Wigner function of \(\vert\Psi_{\alpha}\rangle \), we generated \(M=100\) samples of \(n=16\times10^{6}\) quadrature data \((X_{\ell},\Phi_{\ell})\) distributed according to the noisy probability density \(p_{\rho}^{\eta}(x_{\phi},\phi)\) explicitly given in (31) of Appendix B, namely by considering an efficiency lower than 50% (\(\eta=0.45\)). Starting from each set of simulated quadrature data we reconstructed the associated Wigner function by means of (8) and (9). The processing of such an amount of data has been supported by an efficient calculation of the estimator as detailed in Appendix D. The averaged reconstructed Wigner functions \(E [W^{\eta ,r}_{h,n}(q,p) ]\) for \(\eta= 0.45\) are shown in Figure 2 for two representative values of the parameter β.

The choice to average over the M reconstructed Wigner functions has the benefit of reducing the noise and to show more clearly the interference pattern proper to the Schrödinger cat state. This pattern is exhibited, though more noisily, by each of the M reconstructed Wigner functions: if it were a mere artifact of the reconstruction, its visibility would not increase by averaging over one hundred independent reconstructions.

The mean square error of the reconstructed Wigner functions has been computed as in (10) and compared with the mathematically predicted upper bounds Δ. The dependence of the upper bound reconstruction error on the parameter β is discussed at the end of Appendix C. In Table 1, we compare the reconstruction errors \(\Delta_{h,n}^{\eta ,r}(\hat {\rho})\) with their upper bounds Δ for two significant values of β.

Despite common beliefs, the interference features clearly appear in the reconstructed Wigner function also for an efficiency lower than 50% and the reconstruction errors are compatible with the theoretical predictions. In the following, we make a quantitative study of the visibility of the interference effects.

3.2 A Schrödinger cat interference witness

The real challenge to any reconstruction technique is to show that, working in low efficiency conditions, that technique is really able to overcome the effects of the noisy data. These effects are expected to hamper a faithful reconstruction by destroying the interference pattern present in the Wigner function of the projection \(\vert\Psi_{\alpha}\rangle\langle\Psi_{\alpha}\vert\) onto the linear superposition \(\vert\Psi _{\alpha}\rangle\) and reducing it to an incoherent mixture of the projections onto the two constituent coherent states,

whose Wigner function differs from the previous one only by the absence of the interference pattern. Section 3.1 qualitatively shows that the interference pattern can survive the reconstruction based on noisy data. In the following, we provide a quantitative way of witnessing the coherent interferences by means of a suitable observable \(\hat{O}_{\alpha}\) that we choose of the form

Indeed, \(\hat{O}_{\alpha}\) is the observable contribution to \(\vert \Psi _{\alpha}\rangle\langle\Psi_{\alpha}\vert\) that does not come from the projectors onto the constituent coherent states \(\vert{\pm}\alpha \rangle \): its mean value with respect to the linear superposition \(\langle\Psi_{\alpha}\vert\hat{O}_{\alpha}\vert\Psi_{\alpha}\rangle=1/2\), while, for sufficiently large \(|\alpha|\), its mean value with respect to \(\hat{\rho}_{\alpha\lambda}\) becomes small, as shown by

From (5) it follows that the phase-space function \(O_{\alpha}(q,p)\) associated to \(\hat{O}_{\alpha}\) is

For details see (27) and (30) in Appendix B.

Let us denote by \(W_{j,\mathrm{rec}}^{\alpha}(q,p)\), the estimated Wigner function \(W^{\eta,r}_{h,n}(q,p)\) in (8) for the j-th set of collected quadrature data. It yields a reconstructed mean value

of which one can compute mean, \(\operatorname {Av}(\langle\hat{O}_{\alpha}\rangle _{\mathrm {rec}})\), and standard deviation, \(\operatorname {Sd}(\langle\hat{O}_{\alpha}\rangle _{\mathrm {rec}})\), with respect to the M sets of collected data:

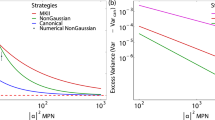

We computed \(\operatorname {Av}(\langle\hat{O}_{\alpha}\rangle_{\mathrm{rec}})\) and \(\operatorname {Sd}(\langle\hat{O}_{\alpha}\rangle_{\mathrm{rec}})\) with \(M=100\) simulated sets of noisy data with \(\eta=0.45\) for two different numbers of simulated quadrature data (see the caption in Figure 3). We repeated the procedure for different values of the parameter β. The results are presented in Figure 3, where the error bars represent the computed \(\operatorname {Sd}(\langle\hat{O}_{\alpha}\rangle_{\mathrm{rec}})\).

Interference witness. \(\operatorname {Av}(\langle\hat{O}_{\alpha}\rangle_{\mathrm{rec}}) - \frac{\mathrm {e}^{-2|\alpha|^{2}}}{1+\mathrm {e}^{-2|\alpha|^{2}}}\) as a function of β. The error bars represent \(\operatorname {Sd}(\langle\hat{O}_{\alpha}\rangle_{\mathrm{rec}})\). For each β, \(M=100\) set of n noisy quadrature data have been considered. The square markers refer to \(\eta= 0.45\) (\(n=16 \times10^{6}\) blue marker and \(n=5 \times10^{5}\) green markers) while the round ones refer to \(\eta= 0.95\) (\(n=16 \times10^{6}\)). The error bars for \(\eta= 0.95\) have been multiplied by 20 in order to make them more visible.

In order to be compatible with the interference term present in \(\vert \Psi_{\alpha}\rangle\), the reconstructed Wigner functions should yield an average incompatible with the incoherent mean value in (16), namely such that

We thus see that the condition in (21) is verified for \(\eta= 0.45\), that is the reconstructed Wigner functions are not compatible with incoherent superpositions of coherent states, if enough data are considered. We also notice that the same behavior is valid for the high efficiency \(\eta=0.95\).

The dependence of the errors on β can be understood as follows: when β decreases the integration interval in (9) becomes larger and approaches the exact interval \([-\infty, +\infty]\). However, this occurs at the price of increasing the reconstruction error. This can be noted both in Figure 3 (larger error bars) and in Figure 2 (increasing noise effects in the reconstructed Wigner function). This problem can be overcome with a larger number of data samples M, that would reduce the reconstruction noise and compensate the effect of decreasing β.

4 Conclusions

We have numerically shown that quantum interference effects can be reconstructed by means of optical homodyne tomography also in low efficiency conditions. In particular, we simulated quadrature data affected by high electronic noise associated with a detection efficiency lower than 50% and, based on the tomographic techniques developed in [12], we reconstructed the Wigner function of a Schrödinger cat state. The ability of doing so in presence of noisy data is a challenging task that any novel reconstruction technique is asked to overcome. Then, taking into account the decay properties of the Wigner function and its Fourier transform, we have checked that the reconstruction errors conform with the theoretical error bounds computed via \(L^{2}\) norms. In order to clearly exhibit the quantum interference effects, both qualitatively in the graphic reconstruction of the Wigner function, and quantitatively in the variance of an interference witness, larger sets of homodyne data are necessary as the detection efficiency gets smaller. Our results not only support the theoretical indications that homodyne reconstruction of quantum features is actually possible for efficiencies lower than 0.5, but also demonstrate for the first time the concrete applicability of this method for low efficiencies in terms of computational effort and number of needed homodyne data.

Notes

The functional relation between the parameters h and r on n also depends on an auxiliary parameter \(\beta>0\). This was introduced in [11] in order to characterize the localization properties on \(\mathbb{R}^{2}\) of the Fourier transforms of the Wigner functions and to possibly exploit them in the reconstruction methods. These have been which are indeed applied to the following class of density matrices: \( \mathcal{A}_{\beta,s,L} = \{\hat{\rho} : \int_{\mathbb{R}^{2}}\mathrm {d}q\,\mathrm {d}p \vert F [W_{\rho}](q,p)\vert^{2} \mathrm {e}^{2\beta(q^{2}+p^{2})^{s/2}} \leq (2\pi)^{2}L \}\).

References

Walmsley IA. Quantum optics: science and technology in a new light. Science. 2015;348:525-30.

Vogel K, Risken H. Determination of quasiprobability distributions in terms of probability distributions for the rotated quadrature phase. Phys Rev A. 1989;40:2847.

Smithey DT, Beck M, Raymer MG, Faridani A. Measurement of the Wigner distribution and the density matrix of a light mode using optical homodyne tomography: application to squeezed states and the vacuum. Phys Rev A. 1993;70:1244.

Lvovsky AI, Raymer MG. Continuous-variable optical quantum-state tomography. Rev Mod Phys. 2009;81(1):299.

Olivares S, Ferraro A, Paris MGA. Gaussian states in quantum information. Napoli: Bibiopolis; 2005.

Welsch D-G, Vogel W, Opatrny T. Homodyne detection and quantum state reconstruction. Prog Opt. 1999;39:63-211.

Paris M, Řeháček J, editors. Quantum state estimation. Berlin: Springer; 2004. (Lecture notes in physics; vol. 649).

Artiles LM, Gill RD, Guţă MI. An invitation to quantum tomography. J R Stat Soc B. 2005;67(1):109-34. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9868.2005.00491.x.

Leonhardt U, Paul H. Measuring the quantum state of light. Prog Quantum Electron. 1995;19:89-130.

Hradil Z. Quantum-state estimation. Phys Rev A. 1997;55:R1561-R1564. doi:10.1103/PhysRevA.55.R1561.

Aubry J-M, Butucea C, Meziani K. State estimation in quantum homodyne tomography with noisy data. Inverse Probl. 2009;25:015003.

Butucea C, Guţă M, Artiles L. Minimax and adaptive estimation of the Wigner function in quantum homodyne tomography with noisy data. Ann Stat. 2007;35:465.

Zavatta A, Viciani S, Bellini M. Non-classical field characterization by high-frequency, time-domain quantum homodyne tomography. Laser Phys Lett. 2006;3(1):3-16.

Kiss T, Herzog U, Leonhardt U. Compensation of losses in photodetection and in quantum-state measurements. Phys Rev A. 1995;52:2433.

D’Ariano GM, Leonhardt U, Paul H. Homodyne detection of the density matrix of the radiation field. Phys Rev A. 1995;52:R1801-R1804. doi:10.1103/PhysRevA.52.R1801.

Herzog U. Loss-error compensation in quantum-state measurements and the solution of the time-reversed damping equation. Phys Rev A. 1996;53:1245.

D’Ariano GM, Paris MGA. Adaptive quantum homodyne tomography. Phys Rev A. 1999;60:518-28. doi:10.1103/PhysRevA.60.518.

D’Ariano GM, Macchiavello C. Loss-error compensation in quantum-state measurements. Phys Rev A. 1998;57:3131.

Kiss T, Herzog U, Leonhardt U. Reply to “Loss-error compensation in quantum-state measurements”. Phys Rev A. 1998;57:3134.

Richter T. Realistic pattern functions for optical homodyne tomography and determination of specific expectation values. Phys Rev A. 2000;61:063819.

D’Ariano GM, Paris MGA, Sacchi MF. Quantum tomography. Adv Imaging Electron Phys. 2003;128:205-308.

Appel J, Hoffman D, Figueroa E, Lvovsky AI. Electronic noise in optical homodyne tomography. Phys Rev A. 2007;75(3):035802.

Lounici K, Meziani K, Peyré G. Minimax and adaptive estimation of the Wigner function in quantum homodyne tomography with noisy data. Preprint. arXiv:1506.06941 (2015).

Garrett G, Rojo A, Sood A, Whitaker J, Merlin R. Vacuum squeezing of solids: macroscopic quantum states driven by light pulses. Science. 1997;275(5306):1638-40. doi:10.1126/science.275.5306.1638.

Dabbicco M, Fox AM, von Plessen G, Ryan JF. Role of \(\chi^{(3)}\) anisotropy in the generation of squeezed light in semiconductors. Phys Rev B. 1996;53:4479-87. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.53.4479.

Grosse NB, Owschimikow N, Aust R, Lingnau B, Koltchanov A, Kolarczik M, Lüdge K, Woggon U. Pump-probe quantum state tomography in a semiconductor optical amplifier. Opt Express. 2014;22:32520-5.

Esposito M, Benatti F, Floreanini R, Olivares S, Randi F, Titimbo K, Pividori M, Novelli F, Cilento F, Parmigiani F, Fausti D. Pulsed homodyne Gaussian quantum tomography with low detection efficiency. New J Phys. 2014;16(4):043004.

Spagnolo N, Vitelli C, Lucivero VG, Giovannetti V, Maccone L, Sciarrino F. Phase estimation via quantum interferometry for noisy detectors. Phys Rev Lett. 2012;108:233602. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.108.233602.

Bartley TJ, Donati G, Jin X-M, Datta A, Barbieri M, Walmsley IA. Direct observation of sub-binomial light. Phys Rev Lett. 2013;110:173602. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.110.173602.

Donati G, Bartley TJ, Jin X-M, Vidrighin M-D, Datta A, Barbieri M, Walmsley IA. Observing optical coherence across Fock layers with weak-field homodyne detectors. Nat Commun. 2014;5:5584.

Harder G, Mogilevtsev D, Korolkova N, Silberhorn C. Tomography by noise. Phys Rev Lett. 2014;113:070403. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.113.070403.

Abramowitz M, Stegun IA. Handbook of mathematical functions with formulas, graphs, and mathematical tables. 9th Dover printing, 10th GPO printing ed. New York: Dover; 1964.

Zimmermann K. Efficient Wigner function reconstruction. In preparation.

Zimmermann K. Tomohowk. https://github.com/tomohowk/tomohowk (2016).

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Francesca Giusti for insightful discussions and critical reading of the paper and thank referee number 2 of the manuscript in reference [27] for stimulating the discussions that led to this work. This work has been supported by a grant from the University of Trieste (FRA 2013).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

ME performed the numerical experiments supported by FR, GK, AC, and KZ. FB developed the theoretical description supported by KT, RF; KZ developed the optimized computational approach. ME and FB coordinated the project, together with DF and FP; ME and FB wrote the manuscript with contributions from all other co-authors.

Appendices

Appendix 1: Wigner function reconstruction

The quadrature probability distribution (2) can be conveniently related to the Wigner function by passing to polar coordinates \(u=\xi\cos\phi\), \(v=\xi\sin\phi\), such that \(0\leq\phi\leq\pi \) and \(-\infty< \xi< +\infty\):

where \(F[p_{\rho}(x,\phi)](\xi)\) denotes the Fourier transform with respect to x of the probability distribution:

Since y can be considered a normally distributed random variable independent of \(\hat{x}_{\phi}\), the noise affected distribution of the eigenvalues of \(\hat{x}_{\phi}\) in (7) is given by the following convolution:

Its Fourier transform is connected with that of \(p_{\rho}(x,\phi)\) according to

By inserting \(F[p_{\rho}( x ,\phi)](\xi)\) into (23), one can finally write the Wigner function in terms of the noisy probability distribution \(p^{\eta}_{\rho}(x,\phi)\):

Appendix 2: Coherent state superposition: Wigner function

The Wigner function corresponding to the pure state \(\hat{\rho }_{\alpha}=\vert\Psi_{\alpha}\rangle\langle\Psi_{\alpha}\vert\) and its Fourier transform read

For a generic Wigner function \(W_{\rho}(q,p)\) one computes the quadrature probability density \(p_{\rho}(x_{\phi},\phi)\) in (2) by means of the so-called Radon transform:

It follows that the probability density \(p_{\rho}(x_{\phi},\phi)\) and the noise affected probability density \(p^{\eta}_{\rho}(x_{\phi},\phi)\) in (24) are given by:

where

Appendix 3: Upper bound reconstruction error estimation

Here we derive an upper bound to the mean square error of the reconstructed Wigner function. This analysis is necessary in order to find an optimal functional relation between the free parameters in the reconstruction algorithm such as to minimize the reconstruction error. For this purpose we follow the techniques developed in [11], adapting them to the case of a linear superposition of coherent states. Using (8) and (9), one starts by rewriting the error in (10) as the sum of three contributions:

\(C^{c}_{r}(0)\) denoting the region outside the circle \(C_{r}(0)\), where \(q^{2}+p^{2}>r^{2}\). The first and the third term correspond to variance and bias of the reconstructed Wigner function, respectively, while the second term is the error due to restricting the reconstruction to the circle \(C_{r}(0)\).

Given a density matrix ρ̂, the second term can be directly calculated. This is true also of the bias; indeed, because of the hypothesis that the pairs \((X_{\ell},\Phi_{\ell})\) are independent identically distributed stochastic variables, it turns out that

differs from the true Wigner function \(W_{\rho}(q,p)\) in (26) by the integration over ξ being restricted to the interval \([-1/h,1/h]\). Moreover, its Fourier transform reads

where \(w = (w_{1},w_{2})\), and \(\chi_{[-1/h,1/h]}(\Vert w\Vert )\) is the characteristic function of the interval \([-1/h,1/h]\). Then, by means of Plancherel equality, one gets

The variance contribution can be estimated as follows: firstly, by using (8) and (9), one recasts it as

Then, a direct computation of the first contribution yields the upper bound

with \(o(1)\) denoting a quantity which vanishes as h when \(h\to0\). On the other hand, the second contribution can be estimated by extending the integration over the whole plane \((q,p)\in\mathbb{R}^{2}\) and using (36) together with (4):

Let us consider now the specific case of \(\hat{\rho} = \hat{\rho }_{\alpha}\), the superposition of coherent states defined in (11). The auxiliary parameter β labelling the class of density matrices \(\mathcal{A}_{\beta,s,L}\) in endnote a with \(s=2\) can be used to further optimize the reconstruction error \(\Delta_{h, n}^{\eta, r} (\hat{\rho}_{\alpha})\). In particular, since \(\vert\sum_{j=1}^{M} z_{j}\vert^{2}\leq M \sum_{j=1}^{M}|z_{j}|^{2}\), we get the upper bounds

where \(R^{2}=q^{2}+p^{2}\) in (42) and \(R^{2}=w_{1}^{2}+w_{2}^{2}\) in (43). Then, one derives the upper bounds

which simultaneously hold for \(0<\beta<1/4\).

Then, by means of the Cauchy-Schwartz inequality, one can estimate the contribution (33) to the error,

and similarly for (37),

where \(\Theta(x)=0\) if \(x\leq0\), \(\Theta(x)=1\) otherwise, and

Altogether, the previous estimates provide the following upper bound to the mean square error in (32)–(34):

where \(\Delta_{1,2,3}\) do not depend on h, r and n and \(\Delta _{1}(\gamma) = \sqrt{\pi}/(16 \pi^{2} \sqrt{\gamma})\) is the leading order term in (39). By setting the derivatives with respect to r and h of the right hand side equal to 0, one finds

Whenever β is such that the logarithm of the number of data is much larger than the logarithms in which β appears explicitly, then, to leading order in n, the upper bound to the mean square deviation is minimized by

The behavior of the optimal theoretical upper bound Δ as a function of β is shown in Figure 4.

Notice that this approximation breaks when β gets close to \(1/4\) and 0. In the first case, the quantity \(\Delta_{3}(\beta)\) diverges and so the bound becomes loose, while, in the second one, the logarithms which contain β diverge to −∞ and no solution for \(1/h\) is possible. It thus follows that the range of values \(\beta\in[\beta_{0},\beta_{1}]\) where the numerical errors \(\Delta_{h,n}^{\eta,r}(\hat{\rho}_{\alpha})\) are comparable with meaningful theoretical upper bounds Δ depends on the number n of data and on the efficiency η. For the case considered in this work, \(n=16\times10^{6}\) and \(\eta =0.45\), \(\beta_{0}=10^{-4}\) and \(\beta_{1}=0.1\). In Figure 5 the optimal theoretical upper bound Δ is compared with the real reconstruction errors calculated according to (10) for different values of β in the range where the comparison is meaningful.

Appendix 4: Calculation of the estimator

To facilitate the treatment of a large amount of data, we sought to optimize the computation of the estimator. Our starting point is (9), where we are interested in the efficient calculation of the integral for a fixed position in phase space \((q, p)\) and a given quadrature data point \((X_{\ell}, \Phi _{\ell})\). Hence, to simplify the notation, let us introduce the variable \(x = q\cos\Phi_{\ell}+p\sin\Phi_{\ell}-X_{\ell}/\sqrt{\eta}\), suppressing all its dependencies. Then the estimator (9) writes as

Through a series of transformations, this can be written in terms of the error function erf as

where ℜ denotes the real part. This changes the problem from the cumbersome numerical integration to that of the evaluation of the error function, for which a large body of work exists. We settled for the series expansion given in [32], Eq. (7.1.29), which in our case leads to good convergence already with as few as six terms [33].

Since the calculation is independent for both individual quadrature data points and different points in phase space, the problem is well suited for parallelization. Furthermore, the quadrature data alone allows for an estimate of the support of the Wigner function in phase space, which can be exploited to construct a well adapted mesh automatically, without any prior information about the state. The resulting algorithm has been implemented, optionally making use of multiple cores in a single computer or the advanced computational abilities of modern graphics cards for the parallelization, and is available as Open Source Software [34].

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Esposito, M., Randi, F., Titimbo, K. et al. Quantum interferences reconstruction with low homodyne detection efficiency. EPJ Quantum Technol. 3, 7 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1140/epjqt/s40507-016-0045-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1140/epjqt/s40507-016-0045-5