Abstract

Physics has up to now missed to express in mathematical terms the fundamental idea of events of a path in time and space uniquely succeeding one another. An appropriate mathematical concept that reflects this idea is a well-ordered set. In such a set every subset has a least element. Thus every element of a well-ordered set has as its definite successor the least element of the subset of all elements larger than itself. This is apparently contradictory to the densely ordered real number lines which conventionally constitute the coordinate axes in any representation of time and space and in which between any two numbers exists always another number. In this article it is shown how decomposing this disaccord in favour of well-ordered sets causes spacetime to be discontinuous.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Whenever the motion of a particle is described in classical, special relativistic or general relativistic space and time it is always implicitly assumed that the particle moves from an initial event to a final event through a sequence of consecutive intermediate events. In other words, it is presumed that every element of the path has an unique successor. But even though this is a fundamental concept, it is never disclosed. It is neither named in Newton’s laws of motion or his law of gravitation nor mentioned in the basic principles of Special or General Relativity. Consequently, it is never expressed in mathematical terms.

Also without further ado these theories make constitutively use of the real number line by employing it as (local) coordinate axes or coordinate axes and parameter line for their respective manifolds which represent space and time.

Unfortunately these very two unnamed axioms are contradictory to each other. This becomes apparent most clearly in terms of ordered sets. An ordered set (A, R) is a set A together with a binary order relation R that is itself a subset of the set of all ordered pairs \(A\times A\) of A; see [1, p 10, p 17], [2, p 64, p 80].

A densely ordered set is an ordered set in which between any two elements of the set exists another element of the set; see [2, p 205]. Well known examples for this are the rational numbers or the real numbers together with the natural order of numbers; see [2, p 213]. By employing the real number line as coordinate axes this is transferred into the resulting \({\mathbb {R}}^n\). The open balls as the base of the Euclidean topology are a reflection of this. For any radius \(r>0\) exists a non-empty open ball around any \(x\in {\mathbb {R}}^n\). Since Riemannian manifolds are locally homeomorphic to a suitable \({\mathbb {R}}^n\) the dense order of \({\mathbb {R}}\) is not only a characteristic of Newtonian and Special relativistic spacetime but also of the description of space and time in General Relativity.Footnote 1

Another type of ordered sets are well-ordered set in which every non-empty subset has a least element; see [2, p 224]. Therefore every element of a well-ordered set has as its definite successor the least element of the subset of all elements larger than itself. This evidently provides appropriate means to mathematically represent the idea of events in spacetime uniquely succeeding one another. The defining example for well-ordered sets are ordinal numbers. Among these the natural numbers together with the natural order of numbers are the best known instance. But they are by far not the only members of this class of numbers. In fact, they just open the gates into this transfinite realm.

Densely ordered sets and well-ordered sets are obviously irreconcilable. A familiar example for this incongruity is the countability of \({\mathbb {Q}}\): bijections form \({\mathbb {Q}}\) to \({\mathbb {N}}\) are known to exist but none of them preserve the order of \({\mathbb {Q}}\).

Since each of the two unnamed axioms of spacetime respectively incorporates one of these types of ordered sets they cannot be assumed in combination.

As it is shown in [4] or [5, chapter 1.6] the concept of ordered sets is already a part of the definition of Minkowski space. However, with regard to the question if Minkowski space should be a densely ordered set or a well-ordered set nothing is specified. In Sect. 2 it is explicated that settling this unanswered question in favour of well-ordered sets causes spacetime to be discontinuous. More specifically, well-ordered Minkowski spacetime proves to consist of representations of ordinal numbers. For the sake of completeness the alternative of a densely ordered spacetime is stated as well with the tacit understanding that this choice is equivalent to renouncing the conception of a particle moving along a sequence of consecutive events. All this is achieved without recourse to the notion of quantum gravity. Thus, already a reformulation of electrodynamics over a well-ordered spacetime which produces the existing (large amount of) experimental results can verify that time and space are discontinuous. But more importantly this will provide a link between the fundamental principle of events uniquely succeeding one another and experimental data.

As a first step towards a rephrasing of electrodynamics (or the theory of any other force) an approach to well-ordered spacetime is presented in Sect. 3 which is different and more general than that of Sect. 2: for the reason of being a field which naturally incorporates ordinal numbers (and other infinite elements) besides real numbers Conway’s class of surreal numbers \(\text {No}\) prove to be an appropriate mathematical ground for investigating well-ordered spacetimes. Especially a concise way of navigating discontinuous spacetimes by virtue of pairs of infinite elements and their additionally included multiplicative inverse elements is described. Furthermore they allow for a consistent way of handling spacetimes based on representations of ordinal numbers that contain limit ordinals. The latter leads to the definition of virtual events. This is followed by opposing the exponential map of Riemannian geometry to the idea of visiting all elements of a geodesic in their natural order by consecutively transiting to a distinct next neighbour in Sect. 4. Section 5 exhibits in terms of cardinality how much unnecessary information is introduced into path integration when a densely ordered spacetime is used instead of a well-ordered spacetime. Finally, Sect. 6 takes a look on the quantisation of the area operator of Loop Quantum Gravity from the angle of well-ordered sets and arrives at the result that LQG (unwittingly) uses the lines of argumentation presented in the preceding sections. The reconstruction of \({\mathbb {R}}^4_1\) from a \({\mathbb {R}}^4\) by means of ordered sets in Appendix A is not fully part of the main line of reasoning of this article. But it is nevertheless worth noting because it describes how the need to keep the disjoint ordered and unordered subsets of a partial causal order apart during linear transformations leads to c.

2 Causality and order types

As mentioned in the introduction, the mathematical representation of the idea of “a distinct next neighbour” is the concept of well-order. In a well-ordered set \((A,<^{\text {ord(A)}})\) every subset has a least element. Thereby, every element \(\alpha \) of a well-ordered set A has as its unique successor \(\alpha +1\) the least element of the subset of all elements of \((A,<^{\text {ord(A)}})\) larger than itself.

In contrast to this, between any two elements a, c of a densely ordered set \((A,<^{\text {den}})\) always exists a third element b of \((A,<^{\text {den}})\). Thus, a subset of \((A,<^{\text {den}})\) consisting of elements larger than a specific member a of \((A,<^{\text {den}})\) has no least element. The strict mathematical formulation of the conception of infinitesimal vicinity is based on this. Consequently, there are no definite next neighbours in an infinitesimal vicinity, or more succinctly, the expression “infinitesimal next neighbour” contains a contradiction.

How dissolving this contradiction by choosing either a well-ordered or a densely ordered set shapes spacetime may be seen from the world line of a particle in Minkowski space

Of the pair of conditions for two events \(x,y\in M\) being chronologically ordered \(x\ll y\)

the second one determines if the two events are part of an admissible world line, whereas the first one establishes the sequence of events; see [4] or [5, chapter 1.6]. Therefore, matters of order of events can be discussed in the rest frame of a particle without loss of generality. For a detailed discussion of the implementation of the order given by (2) and (3) into \({\mathbb {R}}^4\) see Appendix A. Of course, all inequalities and equalities in (1)–(3) are to be understood in terms of the natural order of numbers and most certainly this understanding shall persist. Since this specifies the order relation \(R\subset A\times A\) in the pair (A, R), the issue of choosing a well-ordered or a densely ordered set is rephrased to the question which set of numbers is well-ordered or densely ordered by the natural order <.

With regard to the natural order neither \(({\mathbb {R}},<)\) nor \(({\mathbb {Q}},<)\) is well-ordered, because both contain subsets which have no least element. Moreover, every uncountable subset of \(({\mathbb {R}},<)\) is not well-ordered. But all of these sets are densely ordered by <, and for this reason allow infinitesimal vicinities for all events.

On the other hand, every ordinal number is well-ordered and for every ordinal number \(\alpha =\{\beta \in \text {Ord}~|~\beta<\alpha <\omega _1\}\) less than the smallest uncountable ordinal number \(\omega _1\) exists an order embedding into \(({\mathbb {Q}},<)\), i.e. every countable ordinal number \(\alpha <\omega _1\) can be represented by a monotonic sequence of rational numbers; see [2, p 214, theorem 3] or [6, p 350/351]. By an equally monotonic injection this sequence is easily transferred into \(({\mathbb {R}},<)\). Due to the fact that every element of \(\alpha =\{\beta \in \text {Ord}~|~\beta<\alpha <\omega _1\}\) has a unique successor there is always a non-empty interval \(\emptyset \ne (q(\beta ),q(\beta +1))\subset {\mathbb {Q}}\) between their images which is transferred by an injection to \(\emptyset \ne (x(\beta ),x(\beta +1))\subset {\mathbb {R}}\). Therefore, the set that represents \(\alpha \) in \({\mathbb {Q}}\) or \({\mathbb {R}}\) is a discontinuous union of singletons:

For \({\mathbb {N}}\ni \alpha <\omega \) the first sets in (4) and (5) reduce to \(\left[ q(0),q(\alpha )\right] \) and \(\left[ x(0),x(\alpha )\right] \).

In summary, if events are to have distinct successors and if this order is to be expressed by the natural order <, they have to be elements of a countable ordinal number \(\alpha <\omega _1\) to which \(({\mathbb {R}},<)\) merely serves as an embedding space. Notably, admissible events necessarily form a discontinuous subset of \(({\mathbb {R}},<)\). Quantisation is the special case of discontinuity where events are evenly timed and spaced.

By Lorentz transformations the spatial dimensions contribute to all other admissible time axes. For this reason, they must be ordered by the same order type as the time axis or otherwise the order type chosen for the \(x^0\)-coordinate differs between different frames of reference:

The \(R^{i}(\alpha ),i=0,1,2,3\) are different representations of \(\alpha \), which clearly exist. Though the \(R^j(\alpha ),j=1,2,3\) are well-ordered this does not say their order has to be followed strictly in every step. As long as (3) is satisfied their respective values can be associated to a \(x^0_\beta \) as freely as the \(x^j\) of \(\left( {\mathbb {R}},<\right) \) can be associated to a \(x^0\in \left( {\mathbb {R}},<\right) \). Only the \(x^0\)-coordinates are restrained to grow to larger values in their respective orders.

In case of a well-order (7), Lorentz transformations are understood to be causal automorphismen of the embedding space

which also lends its quadratic form to its subspaces.

Requiring the exclusive choice between (6) xor (7) to be conserved by Lorentz transformations seems at first glance to enlarge the set of invariants of the causal automorphismen group of M. But this requirement is already a member of said set because, as has just been shown, the causality condition (2) actually states the formation of an ordered type, or respectively, an ordered set \(\left( A,R\subset A\times A\right) \). Firstly, the constraint of events being put in sequence along the \(x^0\)-axis by the standard order < determines the binary relation R:

Secondly, the choice of a set

of whose set of ordered pairs < is a subset

completes the assembly of an order type, or respectively, an ordered set:

As the contradiction in the term “infinitesimal next neighbour” reveals, physics cannot avoid to encompass the full extent of the causality condition (2). The use of a well-order the author is biased to, may be declared by replacing M by \(M(\alpha )\) in (1); cf the rhs of (8).

For a sequence of events on the cone the above argumentation is valid if it is restricted to sequences of events for which the relation \(x\lessdot y\)

is transitive, i.e. for straight lines on the cone.

For more details of the prevalence of time as the carrier of causal order over the spatial dimensions as it is expressed by \(\Rightarrow \) in (6) and (7) see Appendix A.

A question that immediately arises when utilising well-ordered spacetime is how to handle an how to interpret spacetimes that are based on ordinal numbers containing limit ordinals larger than \(\omega =|{\mathbb {N}}|\). To this end \(M(\alpha )\) is not really apt. A mathematical framework that is more suitable for these purposes are the surreal numbers which are discussed in Sect. 3.

3 Surreal spacetime

An appropriate mathematical ground for investigating well-ordered spacetimes is provided by Conway’s surreal numbers \(\text {No}\) [7]. This class of numbers comprises real numbers as well as infinite and subfinite elements like \(\omega \) and \(\frac{1}{\omega }\). In [7] elements like \(\frac{1}{\omega }\) are called infinitesimal elements. To avoid confusion with anything that is based on the concept of infinitesimal vicinity (see second paragraph of Sect. 2), \(\frac{1}{\omega }\in \text {No}\) and alike elements are called subfinites in this article. For the conceptual reasons for this distinction see Appendix B.

Since \(\text {No}\) is also a field, \(\frac{1}{\omega }\) is the multiplicative inverse of \(\omega \) in the exact sense of the group operation \(\text {No}\times \text {No}\rightarrow \text {No}\) representing multiplication on \(\text {No}\): \(\frac{1}{\omega }\omega =\omega ^{-1}\omega =1\in {\mathbb {N}}\subset {\mathbb {R}}\subset \text {No}\). Moreover, every surreal number is uniquely expandable in terms of orders of magnitude of \(\omega \), called its normal form:

Members of \(\text {No}^4\) may then be written as

Other than in (15) there are a suitable number of \(r^i_\beta \) allowed to be 0 so that the sums in all components \(s^i\) of the form (15) range over the same order of magnitudes. This lets emerge a complete copy of \({\mathbb {R}}^4\) with basis \(\{e_i\}\) at each order of magnitude \(\omega ^{y_\beta }\) from which the coefficient for the associated order of magnitude can be selected. The first step in making (16) useful for physics is to designate the zeroth order of magnitude \(\omega ^0=1\) to be position space, or more precisely, to designate the coefficients \(r^i_0\) of \(\omega ^0\) to be events in spacetime \(r^i_0=x^i_0\equiv x^i\):

Additionally, in (17c) \(y_0=0\) is chosen to be the largest order of magnitude so by virtue of (15c) all other orders of magnitude \(y_{\beta >0}\) have to be negative. This is reflected by the according negative sign in the exponents in the second sum of (17a). Hereby, the event \((x^0_0,x^1_0,x^2_0,x^3_0)\) is furnished with a surrounding of subfinite numbers \(\omega ^{-y_\beta }r^i_\beta e_i\). The coefficient of any of those subfinite orders of magnitude \(\omega ^{-y_{\beta>0}}=\frac{1}{\omega ^{y_{\beta >0}}}\) can be turned into an event in spacetime if (17a) is multiplied by the corresponding inverse infinite order of magnitude \(\omega ^{y_{\beta >0}}\):

The three terms in (18a) sustainably spark a perception of past (\(\beta<\delta \leftrightarrow \omega ^{y_\beta }\gg \omega ^0\leftrightarrow y_{\beta <\delta }>0\)), present (\(\beta =\delta \leftrightarrow \omega ^{-y_\delta +y_\delta }=\omega ^0=1\)) and future (\(\beta>\delta \leftrightarrow \omega ^{-y_\beta }\ll \omega ^0\leftrightarrow y_{\beta >\delta }<0\)).Footnote 2 Thus the exponents of the orders of magnitude establish a causal order of events, which is the task already committed to the \(x^0\)-components of events. These two orders are accordable by an order-reversing bijection between the sets \(\{y_\beta \}\) and \(\{r^0_\beta \}\):

By this the inverted well-ordering (15c) of the sequence \(\{y_\beta \}\) becomes relevant to the set \(\{r^0_\beta \}\). Conversely, \(\{r^0_\beta \}\in {\mathbb {R}}\) restricts \(\alpha \) to countable ordinal numbers as there are no uncountable well-ordered subsets of \(({\mathbb {R}},<)\) [1, 6, p 350]. For violation of causality occurring when a well-order and a dense order are collocated see Sect. 4.

Summarised, in (17a) and (18a) \(\alpha \) is strictly less than \(\omega _1\) and \(r^0_\beta \in (R^0(\alpha ),<)\). In yet other words: when the inverted well-order of the order of magnitudes of an element s of \(\text {No}^4\) in its normal form is harmonised with the natural order of real numbers, \(\text {No}^4\) relegates to its subset of elements of countable normal length \(\alpha =\text {nl}(s)<\omega _1\) with causally ordered members of different \(\omega ^{y_\beta }{\mathbb {R}}^4\) as candidates for events in spacetime:

In order to establish the speed of light in each \(s\in {\mathbb {S}}^4_{causal}(\alpha )\) it must be subject to the further restraint that each \(\omega ^{-r^0_\beta }r_\beta =\omega ^{-r^0_\beta }(r^0_\beta ,r^1_\beta ,r^2_\beta ,r^3_\beta )\in \omega ^{-r^0_\beta }{\mathbb {R}}^4\) is a member of the cone

where (21b) correlates to the first term in (18a), (21c) to the third term in (18a) and \(x_0\) is the second term in (18a) denominating the present event in spacetime. For fixed \(\kappa <\delta \) and \(\delta <\rho \) (21b) and (21c) have to be iteratively true:

All in all, for fixed \(\alpha \) the set of candidates for events in spacetime is composed of the following surreal numbers:

(20)–(22) are the analogues of (2) and (3) resp. (A.4a) and (A.4b) for subsets of \(\text {No}^4\) with the addition of harmonising the inverse well-order of the orders of magnitude with the order of position space to make (23) fully internally ordered.

It should be clear by now that \(\text {No}^4\) is utilised in terms of paths. Every element of (23) constitutes a discontinuous path to be paced out by multiplication by eligibly selected \(\omega ^{r^0_\delta }\). The information about the transition from \(r_0\) to \(r_\delta \) is contained in the pair \((r_0+\frac{r_\delta }{\omega ^{r^0_\delta }},\omega ^{r^0_\delta })\); for a detailed discussion of this with regard to topology see Appendix B. Obviously forces act whenever the \(r_\beta \) do not form a straight line and/or the distance between consecutive coefficients \(r_{\beta +1}-r_\beta \) and \(r_{\beta +2}-r_{\beta +1}\) varies. Furthermore every \(r_\delta \) is a point of intersection for many paths each of which offers a different succeeding event. In this vein \({\mathbb {M}}(\alpha )\) (23) acts as a stage of potential next events.

But even that there are \(\omega _1\)-many paths intersecting at \(r_\delta \), i.e. that there is a full \({\mathbb {R}}^4_1\)-cone of successors \(r_\pi \) available at \(r_\delta \), this does not cure the contradiction in the statement “infinitesimal next neighbour”, because each of this potential next events \(r_\pi \) can only be reached by means of a discontinuous path. And what is even more important, all potential events with time component less than that of the successor \(r_\eta \) which became reality \(r^0_\delta<r^0_\pi <r^0_\eta \) cannot be revisited, as it would be necessary to establish the density needed for an infinitesimal vicinity, or else causality is breached. See Sect. 4 for more on this. On the other hand the interpretation of every \(r_\pi \) having a probability to be picked as the next real event is readily at hand. A \(s\in {\mathbb {M}}(\alpha )\) is then established step-by-step instead of being regarded as an already complete entity which deterministically fixes a path.

Reversely, a stage-like \(M(\alpha )\) is transformed into \({\mathbb {M}}(\alpha )\) by firstly generating the set of all path (2) and (3) allow in (8) and repeating this step for all combinations \(\times _{i=0}^3(R^i(\alpha ),<)\) of all order embeddings of \(\alpha \). After this, aligning all these paths along orders of magnitude by using the negative of the \(r^0\)-components of their points as exponents for \(\omega \) leads to \({\mathbb {M}}(\alpha )\).

When employing well-ordered Minkowski space by means of path-inclined causal normal forms of surreal numbers (23) acknowledging the question how to handle spacetimes involving limit ordinals \(\lambda \), which is pending since the end of Sect. 2, should no longer be postponed. Limit ordinals \(\lambda \) are elements of every ordinal number \(\alpha \) larger than \(\omega \) and are characterised by lacking a definite predecessor. Hence the corresponding \((r^0_\lambda ,\mathbf {r}_\lambda )\) is approached but cannot be reached by stepping out the trail of \((r^0_{\beta<\lambda },\mathbf {r}_{\beta <\lambda })\). The full and mathematically exact usability of the realms of the subfinite and the infinite within the framework of surreal numbers facilitates the following answer to this question: Only coefficients of orders of magnitude whose exponent \(r^0_\lambda \) corresponds to a limit ordinal \(\lambda \in \alpha \) are permitted to become reality:

Multiplying a \(s\in {\mathbb {M}}(\alpha >\omega )\) by \(\omega ^{r^0_\lambda }\) sends all \(\omega ^{-r^0_{\delta<\beta<\lambda }}r_{\delta<\beta <\lambda }\) between the present event \(\omega ^0r_\delta \) and its designated successor \(\omega ^{r^0_\lambda }r_\lambda \) directly to \(\omega ^{(-r^0_{\delta<\beta<\lambda }+r^0_\lambda )}r_{\delta<\beta <\lambda }\), i.e. directly from the future (\(-r^0_{\delta<\beta<\lambda }<0\)) to the past \((-r^0_{\delta<\beta <\lambda }+r^0_\lambda )>0\) without a stop at the present. These sections of virtual events of \(s\in {\mathbb {M}}(\alpha )\) (23) therefore offer stages on which additional structures may play out any desired real feature. “Real” denotes at first real numbers promptly implying accessibility to measurement. Examples for such virtual formation processes of real features that immediately come to mind are the generation of a dressed inertial mass from bare inertial masses or the shaping of a dressed electric charge from bare electric charges. Producing divergences while constituting the final real feature along a sequence of virtual stages should be avoidable by using suitably chosen subfinite bare instances of the desired feature on each virtual stage. Two of the measures for the suitability of the subfiniteness of the bare instances of the feature under consideration are surely the length of a virtual section and the weight of a single virtual stage in it. If multiple features are to be formed between two real events the index set for real events (24) needs to be refined to limit ordinals which themselves comprise a sufficient number of limit ordinals to furnish enough virtual structure to assemble all that is requested. In such situations mass may serve as a bracket with inertial mass being the first feature to arise and gravitational mass being the last characteristic to be accrued until its numerical value is that of inertial mass. GTR strongly suggests that the subfinite bare instances of every other feature are accompanied by a subfinite bare instance of gravitational mass, unless the bare instances of the other features are the bare instances of gravitational mass themselves, merely in disguise. Thereby the well-order of spacetime transfers to all other physical theories as a guiding principle; for some effects of this on path integration see Sect. 5. By the respective orientation and distances of its events to each other every \(s\in {\mathbb {M}}(\alpha )\) (23) generally prescribes if and how forces are acting leaving it to the additional structures to describe which force(s) exactly mould(s) a given portion of s.

Finally, the independent \({\mathbb {R}}^4\) at different orders of magnitude \(\omega ^\beta \) need not have parallel bases. Whenever the bases \(\{e_{\beta i}\}\) between the respective \({\mathbb {R}}^4\) at each \(\omega ^\beta \) are nonparallel, \({\mathscr {Q}}(c;r_\beta -x_0)\) in (21) has to be replaced by \({\mathscr {Q}}(c;Tr_\beta -x_0)\) where T is a transformation that aligns \(\{e_{\beta i}\}\) and \(\{e_{0i}\}\).

4 Comparing subsets of \(\text {No}^n\) to Riemannian geometry

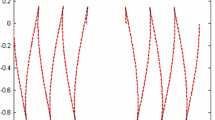

As stated in Sect. 2 there are neither order isomorphic nor order embedding mappings

between the well-ordered \(({\mathbb {R}},<^{\text {ord}({\mathbb {R}})})\) and the naturally ordered \(({\mathbb {R}},<)\). For the topics to be discussed in this section it is instructive to see what especially bijections between these two sets look like in their images. Because \(({\mathbb {R}},<)\) is densely ordered there exists at least one \(y\in ({\mathbb {R}},<)\) between the images \(f(\chi )\) and \(f(\chi +1)\) of a \(\chi \in ({\mathbb {R}},<^{\text {ord}({\mathbb {R}})})\) and its direct successor \(\chi +1\) which in addition is necessarily the image \(f(\xi )=y\) of an \(\xi \in ({\mathbb {R}},<^{\text {ord}({\mathbb {R}})})\) that is either less than \(\chi \) or larger than \(\chi +1\).Footnote 3 In all formal glory:

Thus pacing out \(({\mathbb {R}},<)\) by means of a bijection from \(({\mathbb {R}},<^{\text {ord}({\mathbb {R}})})\) always takes place in leaps and necessarily disregards the natural order of numbers. From within \(({\mathbb {R}},<)\), i.e. without reference to the bijection, this way of organising the reals appears therefore to be devoid of any order. In consequence, an intrinsic order relying on the natural order of numbers like \(<^{1+3}\) (A.3) or \(<^4_1\) (A.4) can either make use of the real numbers thereby renouncing the idea of a definite next event or hold on to the latter effecting that time (and hence space) is a representation of some countable ordinal number, which are the only well-ordered entities for which order embeddings into \(({\mathbb {R}},<)\) exist; compare (12).

This necessity to choose is highly visible in every member of the set

\(({\mathbb {R}},<^{\text {ord}({\mathbb {R}})})=\varXi \ge \omega _1\) is a ordinal number from the infinite realm of \(\text {No}\) which contains an ordinal sequence of the real numbers. The \(\chi \) are the ordinal numbers \(\chi <\varXi \) constituting \(\varXi \) in the sense of the usual definition of an ordinal number as the union of all its predecessors (or a suitable subset thereof if \(({\mathbb {R}},<^{\text {ord}({\mathbb {R}})})\) is a proper subset of \(\varXi \)). For \(\varXi \) exists its additive inverse \(-\varXi \) in \(\text {No}\) and the \(-\chi \) are its elements as the \(\chi \) are elements of \(\varXi \). There is more than one bijection \(r^i: ({\mathbb {R}},<^{\text {ord}({\mathbb {R}})})\subseteq \varXi \leftrightarrow ({\mathbb {R}},<)\) and (27) is the union of all s resulting from combining \(\varXi \) with all possible \(\times _{i=0}^nr^i\) among these bijections. Multiplying an element s of (27) by every element of the sequence \(\{\omega ^\chi \}\) yields the sequence \(\{s\omega ^\chi \}\) in which the respective coefficients of the order of magnitude \(\omega ^0=\omega ^{-\chi +\chi }\) form an uncountable sequence \(\{r(\chi )\}\) of members of \({\mathbb {R}}^n\) which is of course the sequence of coefficients of \(\omega ^{-\chi }\) in (27). But no matter which s is the basis for this sequence, none of the involved images \(r^i(\chi )\) reflects the order of \(\{r(\chi )\}\). Inversely, regrouping \(\{r(\chi )\}\) by using one of the \(r^i\) in its natural order calls up the \(\chi \) erratically; see (26). Since the orders of magnitude in the definition of the normal form of a \(s\in \text {No}^n\) decline along a well-order, surreal numbers sustain the idea of a definite next element. In the orders of magnitude’s set of real coefficients in a natural order the transitions between orders of magnitudes are always leaps even when the well-order and the natural order are harmonised as it is done in the following of (18). (26) and the ensuing choice is also present in the exponential map of Riemannian geometry, though not as obvious as in (27). By definition the exponential map takes tangent vectors \(v\in T_o(M)\) at a point o in a complete manifold M to the point \(\gamma _v(1)\) of the geodesic with \(\gamma _v(0)=o\) whose tangent vector at o is v [3, p 70]:

In other words: a member of the tangent space \(T_o(M)\) at o determines by virtue of the exponential map a transition from \(o=\gamma _v(0)\in M\) to \(p=\gamma _v(1)\in M\) in such a way that the portion of M belonging to \(\gamma _v:(0,1)\subset {\mathbb {R}}\rightarrow M\) is omitted. So \(\exp _o\) mediates a leap from o to p (with v being the designator of p at o) instead of facilitating a smooth passage between them. The attempt to restore the idea of a smooth progression from o to p is made by virtue of the density of \({\mathbb {R}}\) that transpires \(\exp _o\); see [3, p 71]:

This shows indeed that every point of \(\gamma _v\subset M\) between o and p is accessible by means of \(\exp _o\). But the idea of smoothly progressing from o to p, i.e. visiting all elements of \(\gamma _v\) in their natural order by consecutively transiting to a distinct next neighbour is not included in (29). If it were a part of (29), the real interval \([0,1]\subset {\mathbb {R}}\) in its entirety would have to be the representation of an (necessarily innumerable) ordinal number which it is not. Since Riemannian geometry is fundamentally build on the concept of infinitesimal vicinities it is not very surprising that the notion of elements of tangent spaces link elements of a Riemannian manifold as definite next neighbours that (28) hints at does not resonate with the rest of the theory. The ignorance of members of a interval of \(\gamma _v\) this requires is for example in contradiction with the topological concept of neighbourhoods which are constitutively woven into the idea of a manifold; cf [3, p 71, proposition 30] and footnote 1.

For discontinuously charting a geodesic (or any other curve) (27) is the instrument of choice. In \({\mathbb {S}}^n((\text {ord}({\mathbb {R}}))\supseteq \omega _1)\) surely exists a s which produces \(\gamma _v\) when successively multiplied by all \(\omega ^\chi \); see also Appendix C. For \(n=4\) all subsets of this s corresponding to a countable ordinal number and whose coefficients of the involved orders of magnitudes additionally satisfy (23) are eligible for physics. As only the coefficients of orders of magnitude associated with a limit ordinal may become reality (24), the coefficients of all other orders of magnitude, i.e. the virtual events, do not need to adhere to \(\gamma _v\). Thus all members of (27) with physical subsets whose real events are congruent, are affiliated to \(\gamma _v\) from the angle of physics.

5 Well-ordered spacetime and path integration

Some first implications of selecting a well-ordered spacetime for quantum theory are attainable by just jumping right in the middle of path integration. For this purpose, the most useful part of this method is the step in the derivation of the orthodox form of the bosonic path integral just before introducing time integration in the exponential function (see for example [9]):

By reason that the order type of spacetime is not dense, it is not possible to turn \(\varDelta t\) into an infinitesimal dt. Accordingly for the associated sum the transition into an integral is barred, even though \(\varDelta t\) is assumed to be already small enough to permit \(H(Q(t_k),P(t_{k-1})) \rightarrow H(q_k,p_{k-1})\). Now this first simple deduction only states a restriction. But starting out from the definition of the Riemann integral, there is another way to obtain the same result which casts some light on the full ordinal quality of N:

The limit on the rhs of (32a) is understood in terms of infinitesimal refinement of the tagged partition (32b), that is to say, every \(\xi \in [a,b]\) is approximated from the left and the right respectively by a sequence \(\{x_{i(n)}^n\}\). Essentially, this procedure is the same as the one by which \({\mathbb {R}}\) is constructed from \({\mathbb {Q}}\). In consequence, a single map \({\mathbb {N}}\rightarrow [a,b]\subset {\mathbb {Q}}\) does not suffice for the intended purpose. Instead, the whole set \({}^{{\mathbb {N}}}{\mathbb {Q}}([a,b])=\{g|g:{\mathbb {N}}\rightarrow [a,b]\subset {\mathbb {Q}}\}\) of functions from \({\mathbb {N}}\) to \([a,b]\subset {\mathbb {Q}}\) is needed. Since already \(2^{{\mathbb {N}}}={}^{{\mathbb {N}}}\{0,1\}\leftrightarrow {}^{{\mathbb {N}}}\{q_1,q_2\},~q_{1,2}\in {\mathbb {Q}}\) is of the same cardinality as \({\mathfrak {c}}\), the cardinality of \({}^{{\mathbb {N}}}{\mathbb {Q}}([a,b])\supset {}^{{\mathbb {N}}}\{q_1,q_2\}\) must at least be \({\mathfrak {c}}\); in fact, it is the same. Thus, in (32a) the vague \(\infty \) should be replaced by an ordinal number \(\gamma \ge \omega _1\), or, more precisely, the limit should be omitted and the sum should run from 1 to \(\gamma \).

The approximation of a function f by simple functions \(f_n\) supports this claim:

If for a non-constant continuous function \(f: [a,b]\rightarrow {\mathbb {R}}^+\) the objective of the procedure (33) really is to realise every value of f by a single indicator function, the limit must aim at least at \(\omega _1\). Otherwise, there will be not enough terms in the sum (33b) to exhaust the range of f completely. In unison with this, \(2^n\) and \(2^{2n}\) should be read as \(2^{{\mathbb {N}}}\) and \(2^{2{\mathbb {N}}}\) to indicate the necessary cardinality of the process (33). Replacing them by an ordinal number \(\gamma \ge \omega _1\) converts the rhs of (33b) into the transfinite expression that it is at its heart.Footnote 4 See [7] for an axiomatic definition of terms like \(\frac{1}{\gamma }\).

As it was shown in Sect. 2, a well-ordered spacetime consists of representations of a countable ordinal number \(\alpha <\omega _1\). Hence, if (30) is evaluated over such a spacetime, N has to be strictly less than \(\omega _1\) and the associated sum in the exponential function cannot turn into an integral. For \(\omega<N<\omega _1\) see Sect. 3. Section 4 gives the details on the unavoidable violation of causality by bijections \(({\mathbb {R}},<^{\text {ord}({{\mathbb {R}}})}\supseteq \omega _1)\leftrightarrow ({\mathbb {R}},<)\).

As a matter of course, the sum over a in (30) cannot be made into an integral for the same reasons that apply to the sum over k. Furthermore, (30) should be adjusted to the use of a well-ordered spacetime by replacing \(\int [\prod _{k=1}^N\prod _adq_{k,a}]\) and \(\frac{1}{2\pi }\int [\prod _{k=1}^{N+1}\prod _adp_{k-1,a}]\) with \(\sum _{q\in {}^{\alpha }{\mathbb {R}}}\) and \(\sum _{p\in {}^{\alpha }{\mathbb {R}}}\) where q and p are order embeddings. In terms of surreal spacetime the sum over order embeddings q is replaced by \(\sum _{s\in {\mathbb {M}}{\alpha }}\) whereas the information contained in the p is now embodied in the according set of pairs \((r_0+\frac{r_\delta }{\omega ^{r^0_\delta }},\omega ^{r^0_\delta })\); cf (23) and the subsequent discussion.

From the point of view of a well-ordered space time, exchanging \(\sum _k\) and \(\sum _a\) in (30) with integrals introduces much unnecessary information which has to be retracted at some point. This may be seen alone from a purely quantitative argumentation: The replacement of these sums by integrals expands the domain of calculations from countable ordinal numbers \(\beta <\omega _1\) to uncountable ordinal numbers \(\gamma \ge \omega _1\), i.e. causes a leap in the cardinality of the set of allowed events of each path which in turn affects the cardinality of the sets that are the domains of \(\sum _{q\in {\mathbb {M}}(\alpha )}\) and \(\int [\prod _{k=1}^N\prod _adq_{k,a}]\):

(20)-(22) restrict each \(f^i\) for respective \(\beta \in \alpha \) to an interval of \({\mathbb {R}}\). But every interval of \({\mathbb {R}}\) is of the same cardinality as \({\mathbb {R}}\) itself so the \(\le \) in (35) turns into a \(=\):

In a densely ordered real spacetime

where the \(g^i\) are restricted by versions of (21)–(22) adapted to a dense order and a real spacetime; the order embedding in (20) turns into confining \(g^0\) to be strictly monotonic increasing. By this the \(g^i\) are restricted for each \(x^0\in ({\mathbb {R}},\le )\) to intervals of \({\mathbb {R}}\), like the \(f^i\) are for each \(\beta \in \alpha \), thus:

It is then no surprise that the retraction of the excess information involves infinities. So all in all, even without taking into account the qualitative differences between the members of the domains of \(\sum _{q\in {\mathbb {M}}(\alpha )}\) and \(\int [\prod _{k=1}^N\prod _adq_{k,a}]\), renormalisation strongly points to a well-ordered spacetime.

6 Well-order and loop quantum gravity

Though without reference to causality, Loop Quantum Gravity uses the lines of argumentation presented in the preceding sections, especially Sect. 5, when determining the main sequence of the spectrum of the area operator \({\mathbf {A}}({\mathscr {S}})\). In order to see this, rewrite equation (6.72) on page 247 in [10] as a transfinite sum by replacing \(\lim _{N\rightarrow \infty }\sum _n\) with \(\sum _{n\in \alpha \in \text {Ord}}\); cf the discussion following (32):

If \(\alpha \) is chosen to be an uncountable ordinal number like \(\chi \) in Sect. 4 or \(\gamma \) in Sect. 5 this expression turns into the classical case (6.73) on page 247 in [10]. (Of course, in this case the sum should be replaced by a double sum \(\sum _{n_1\in \chi _1}\sum _{n_2\in \chi _2}\) with \(\chi _1,\chi _2\) suitably chosen to exhaust the area under consideration.)

If on the other hand \(\alpha \) is chosen to be a countable ordinal number, (41) is barred from turning into a continuous expression. This barring is done by setting \(\alpha \) equal to the set \({\mathscr {S}}\cap \varGamma \). As detailed in the text underneath equation (6.73) on page 247 in [10], there is a maximum of \(N_0\)-many elements in \({\mathscr {S}}\cap \varGamma \):

Since the natural numbers constitute the initial segment of the ordinal numbers and \(N_0\in {\mathbb {N}}\) the index set of (41) is now equal to a countable ordinal number. Because \(\omega \) is not exceeded it is even equal to some finite countable ordinal number. From the point of view of ordered sets and ordinal numbers this is unnecessarily strict. For preventing (41) from being a continuous expression it is just enough that \(\alpha \) is not an uncountable ordinal. It would be interesting to know if there are \(\varGamma \) which intersect \({\mathscr {S}}\) in such a way that the set of their intersections from a transfinite countable ordinal number. In combination with operators which exhibit this characteristicFootnote 5 spacetime will be endowed with more (sub)structure than it obtains form the natural numbers alone; see also Sect. 3 for more on this matter, especially the discussion below equation (24).

Data Availability Statement

This manuscript has no associated data or the data will not be deposited. [Authors’ comment: There is no associated data.]

Notes

In Riemannian geometry \({\mathbb {R}}^n\) is more than a mere vehicle to locally handle a manifold. As stated right at the top of [3, p 1] a smooth manifold is resembling Euclidean space enough to permit the establishment of all essential features of calculus. This statement is realised in the following by defining local coordinate systems to be homeomorphisms, i.e. smooth manifolds and \({\mathbb {R}}^n\) are topologically equivalent. By this the standard topology of \({\mathbb {R}}^n\), whose base are open balls, and hence the dense order of \({\mathbb {R}}\), on which calculus hinges, is fundamentally introduced into smooth manifolds.

\(\omega ^a\ll \omega ^b\) says that \(\omega ^b\) is of a higher order of magnitude than \(\omega ^a\); see [8, p 54].

Inversely there are at best countable many pairs \(x<z\) of elements of \(({\mathbb {R}},<)\) which are mapped to \(f^{-1}(x)=\chi \in ({\mathbb {R}},<^{\text {ord}({\mathbb {R}})})\) and its direct successor \(f^{-1}(z)=\chi +1\).

It is strange that in both Riemann integration and Lebesgue integration results already emerge even if only an initial subset of \(\omega _1\) as plain as the natural numbers \(\omega \subset \omega _1\) is considered (The usual interpretation of \(\lim _{n\rightarrow \infty }\) is to aim for \(\omega \); there is no hint that the use of limit ordinals larger than \(\omega \) and their internal structure is intended.). The condition of continuity does not immediately impose itself to be powerful enough to enforce this. Maybe there have been up to now only taken functions into account which by their definition are structurally plain beyond the requirements of continuity to allow this. Indeed, the author is not aware of any attempt to integrate the Weierstrass function. The same inner liveliness within the restrictions of continuity that prevents its differentiability should also prohibit (32) to yield results when being regarded for this function on \(\omega \) only.

Since \(\lim _{N\rightarrow \infty }\) is used in [10] in the usual way, i.e. just unspecificly aiming at larger values and thus to \(\omega \), and moreover it is claimed that (41) exhibits a continuous result already after this most initial subset of \(\omega _1\), it may be assumed that (41) is an expression which is structurally as plain as the natural numbers; see footnote 4.

There is one subspace of simultaneity at the origin stating to which events it is unrelated. This subspace is readily transferred to other elements by translation. Talking subsequently about a single unordered subspace refers to this blueprint at the origin.

References

T. Jech, Set Theory (Springer, Berlin, 2002)

K. Kuratowski, A. Mostowski, Set Theory (North Holland Publishing Company, Amsterdam, 1976)

B. O’Neill, Semi-Riemannian Geometry (Academic Press, San Diego, 1983)

E.C. Zeeman, Causality Implies the Lorentz Group. J. Math. Phys. 5, 490 (1964)

G.L. Naber, The Geometry of Minkowski Spacetime (Springer, New York, 2012)

Oliver Deiser, Einführung in die Mengenlehre (Springer, Berlin, 2010)

J.H. Conway, On Numbers and Games (A K Peters Ltd, Wellesley, 2001)

H. Gonshor, An Introduction to the Theory of Surreal Numbers (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1986)

Steven Weinberg, The Quantum Theory of Fields, vol. 1 (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2010)

Carlo Rovelli, Quantum Gravity (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2010)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix A: Minkowski space as an ordered set

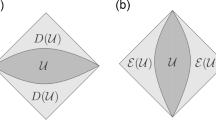

In order to rethink what role the requirements (2) and (3) fulfil and which weight they carry in establishing causality and the formation of Minkowski space it is useful to start out from a plain \({\mathbb {R}}^4\) and (re)assemble M step by step.

At first, all coordinate axes of \({\mathbb {R}}^4\) are equal which is synonymous to stating that there is no preferred direction in \({\mathbb {R}}^4\). More formally this is to say a plain \({\mathbb {R}}^4\) is understood to be an unordered set \(({\mathbb {R}}^4,\emptyset )\). Any order in a sequence made of its elements has to be recorded by an external parameter. This approach to organise members of \({\mathbb {R}}^4\) clearly leans too much towards Newton to be of fundamental use for physics. But it highlights the fact that causality is an independent requisition demanding its own mathematical structure to carry it. If the order of a sequence of elements of \({\mathbb {R}}^4\) is to be read off the elements themselves the mathematical structure to carry this causality has to be sought among the four coordinate axes of \({\mathbb {R}}^4\). One way of making causality an inherent feature of \({\mathbb {R}}^4\) in this manner is to endow all four axes with the task to display the order of a sequence of elements of \({\mathbb {R}}^4\):

By this realisation of inherent causality conceptual uniformity of all four axes is maintained. But it is so overly redundant that no periodicity can occur. Using on the other hand with \(x^0\) just one of the coordinates to embed causality intrinsically into sequences of elements of \({\mathbb {R}}^4\)

allows maximum freedom of choice for the values of the other three coordinates \(x^j, j=1,2,3\). Especially orbits in these coordinates are now possible. In that \(x^0\) is denied to return to values once assumed along sequences of elements ordered by \(<^{1+3}\) it is distinguished from the other coordinates. Thus introducing the independent requirement of causality to \({\mathbb {R}}^4\) is not followed by the introduction of a completely new mathematical structure as its carrier. Instead an existing one is reshaped to its needs, being singled out in the process. The resulting space will be called \({\mathbb {R}}^{1+3}=({\mathbb {R}}^4,<^{1+3})\) from here on with \(<^{1+3}\) being defined by (A.2).

Ordering members of \({\mathbb {R}}^4\) by their \(x^0\)-components establishes only a partial order. All \(x,y\in {\mathbb {R}}^{1+3}\) with \(x^0=y^0\), i.e. which are simultaneous, are not members of this order:

This results in a full \({\mathbb {R}}^3\) of simultaneous events at every \(x^0\) spanned by the \(e_j,j=1,2,3\). In the sense that the members of the subspaces \(x^0\times {\mathbb {R}}^3\) defy to be ordered by their \(x^0\)-component, simultaneity is a concept antagonistic to causality. On a more positive note it is justifiable to regard the members of each of these subspaces of simultaneity to be equal: From the point of view of \((x^0,{\mathbf {x}})\) every \({\mathbf {y}}\in {\mathbb {R}}^3\) at \(y^0>x^0\) is a suitable unordered element of a successor \((y^0,{\mathbf {y}})\). (Yes, every \({\mathbf {y}}\in {\mathbb {R}}^3\); c is not yet established, wait for it.) This idea of equality is easily extended to incorporate transformations of coordinates in the space(s) spanned by \(e_1\times e_2\times e_3\)Footnote 6 since the order constituted by the \(x^0\)-component is not impaired by them. This shows that equipping the task to describe an order solely to one dimension preserves in terms of the dimensionality of subspaces as much as possible of the equality of directions of a plain \({\mathbb {R}}^4\). At the same time it underscores from a different angle that \(x^0\) as the carrier of causality is discerned from the other dimensions.

With causality now an immanent trait of \({\mathbb {R}}^{1+3}\) the set constituting the order \(<^{1+3}\subset {\mathbb {R}}^4\times {\mathbb {R}}^4\) must be the same in all of \({\mathbb {R}}^{1+3}\)’s admissible coordinate systems. That is to say, members of \(<^{1+3}\) must have different \(x^0\)-coordinates respectively in all permissible coordinate systems. Clearly \(<^{1+3}\) excludes transformations which mingle the \(e_0\)-axis with one or more of \(e_1,e_2,e_3\) because any \(e^{\prime }_j,j=1,2,3\) resulting from this is a direction along which elements are unordered in contradiction to all of them having different \(x^0\)-coordinates respectively, i.e. being ordered, in the unprimed frame of reference. A way to overcome this stringent separation is to preclude elements from \(<^{1+3}\) so that coordinate axes of the now enlarged unordered subspace which include the current \(e_0\)-direction are rendered possible. This is exactly what (3) does: every event strictly outside the cone is deemed causally unordered:

In addition, using a double cone to separate causally ordered events from causally unordered events ensures the linearity of the coordinate transformations which preserve the established order; see [4]. With the coordinate axis carrying the causal order considered as time and the space spanned by the remaining axes to be the spatial dimensions the concept of a maximum velocity c ensues. The numerical value of c indicates how many formerly ordered events with \(x^0\ne y^0\) were excluded from \(<^{1+3}\).

Summarised, (2) expresses the fact that a causal order is implemented into \({\mathbb {R}}^4\) by singling out only one of the coordinate axes as its carrier thereby maintaining as much of the equality of all coordinate axes of a plain \({\mathbb {R}}^4\) as possible. The resulting \({\mathbb {R}}^{1+3}\) does not admit any order preserving coordinate transformation that mix the \(e_0\) direction bearing \(<^{1+3}\) and the unordered directions \(e_1, e_2, e_3\). A well-visible hallmark of this is the lack of suitable candidates for new axes spanning the unordered subspace of simultaneity among the directions in \({\mathbb {R}}^{1+3}\) involving \(e_0\). This is healed by (3) which firstly diminishes \(<^{1+3}\) enough to let order isomorphic coordinate transformations incorporating all coordinate axes be allowed. Secondly, its double cone structure refines these transformation to be linear and leads to the emergence of an invariant maximum velocity. Thus the formation of \(M={\mathbb {R}}^4_1=({\mathbb {R}}^4,<^4_1)\) is completed; \(<^4_1\) is defined by (A.4). The invariant division of causally ordered from causally unordered events furnished by (3) is reflected by the Lorentz transformations in that these do not permit the time axis to transit into the unordered region of \({\mathbb {R}}^4_1\) outside the cone and reversely prohibit the spatial axes to enter the ordered region inside the cone.

The idea of events being causally unordered xor causally ordered can be concised as follows: Each coordinate axis in \({\mathbb {R}}^4\) is ordered by the natural order of numbers. The equality of a number of these coordinate axes in \({\mathbb {R}}^4\) is synonymous to the absence of a preferred direction among them which in turn is tantamount to be able to choose freely values for the associated coordinates. Every subspace of \({\mathbb {R}}^4\) for which this holds true is regarded as causally unordered. A causally ordered axis is distinguished from this by restricting the choice of values for its associated coordinate to values greater than the current one.

The above line of argumentation is valid for both kinds of spacetime, densely ordered or well-ordered. Just as the \({\mathbb {R}}^j, j=1,2,3\) in (6) are not forced to grow by their underlying dense order the \(R^j(\alpha )\) in (7) are not forced to take on larger values by their underlying well-order. Only \({\mathbb {R}}^0\) and \(R^0(\alpha )\) are coerced to do so. But, as explained, both spatial parts are bound to the order type of their respective time axes as to not interfere with the creation of other time directions, i.e. with the designation of other directions in the ordered part of M or \(M(\alpha )\) as the carrier of the order.

Appendix B: Comparing surreal numbers to topology

Other than to avoid confusion there are also conceptual reasons for linguistically distinguishing the subfinite elements of \(\text {No}\) like \(\frac{1}{\omega }\) from the notion of infinitesimal vicinities of standard calculus. Topologies are closed (only) under finite intersections of their open sets. The very root of this axiom is to avoid producing inevitably open sets of singletons, i.e. to allow for instance for \({\mathbb {R}}^n\) other topologies than the discrete topology. As a result of this, the notion of convergence resp. infinitesimal vicinity in \({\mathbb {R}}^n\) with the ball topology is committed to distances between elements of \({\mathbb {R}}^n\) which despite ever reducing nonetheless never leave the real numbers. Infinitesimal vicinities like these are the basis for ever improvable inward bound approximations.

Using in their right sets all elements of sets like \(\{\frac{1}{2^n}|n\in {\mathbb {N}}\}\) Conway’s surreal numbers do on a regular basis from day \(\omega \) on what topology axiomatically circumvents for the real numbers. By bouncing all elements of \(\{\frac{1}{2^n}|n\in {\mathbb {N}}\}\) off of 0,

is created which opens the gates to the realm of subfinite elements. Consequently there are non-singleton subsets of \(\text {No}^4\) which contain only one real element \(r_0\in {\mathbb {R}}^n\) and one or more subfinite elements \(r_0+r\frac{1}{\omega ^s}, r\in {\mathbb {R}}^n, s\in \text {No}\). Multiplying one of those surrounding subfinite elements by its inverse infinite order of magnitude \(\omega ^s\) and substracting \(r_0\omega ^s\) gives the real element r. In this sense the subfinites surrounding \(r_0\) (in cooperation with the infinite elements) provide a nexus connecting \(r_0\) to other real numbers which prevents \(r_0\) from being isolated. In contrast to infinitesimal approximation this operation is inherently bound outward.

If causality is not an issue the nexus can of course be a dense set (or have any other desired characteristic). With

or

the rational numbers \(({\mathbb {Q}},<)\ni q(\kappa )\) or the real numbers \(({\mathbb {R}},<)\ni r(\chi )\) may be navigated freely. But since there must be chosen a definite \(\omega ^\kappa \) or \(\omega ^\chi \) to designate the next stop of this journey at \(\omega ^0\) there are always omitted the elements between the current rational or real number \(q(\kappa _0)\)/\(r(\chi _0)\) and the designated \(q(\kappa )\)/\(r(\chi )\). That is to say these transitions are always leaps. Moreover, visiting elements of the interval \((q(\kappa _0),q(\kappa ))\subset ({\mathbb {Q}},<)\) or \((r(\chi _0),r(\chi ))\subset ({\mathbb {R}},<)\) after \(q(\kappa )\) or \(r(\kappa )\) looks acausal from within \(({\mathbb {Q}},<)\) or \(({\mathbb {R}},<)\); see Sect. 4.

Appendix C: Well-ordered paths in \({\mathbb {R}}^n\) without surreal numbers

Alternatively a suitable subset of \({\mathbb {S}}^n(2)\) could be considered in which elements are respectively linked to one another by requiring that the destination of one element is the origin of one other: \((x+y\frac{1}{\omega ^1},\omega ^1)\leftrightarrow (y+z\frac{1}{\omega ^1},\omega ^1)\). This can in turn be transferred into a subset of an order relation \(\sigma \subset R\subset {\mathbb {R}}^n\times {\mathbb {R}}^n\) by requiring that the second member of every element of \(\sigma \subset R\) is the first member of one other: \((x,y)\leftrightarrow (y,z)\). When this is done at least \(\omega _1\)-many times it results in the same kind of path as for an s of (27) without the theory of surreal numbers. But not only is the notation of the s of (27) more compact, their access to handling \({\mathbb {R}}^n\) well-ordered is directly visible, not to mention the contrasting juxtaposition of the inversely well-ordered orders of magnitude and the natural order of at least one of the \({\mathbb {R}}\) of \({\mathbb {R}}^n\). Furthermore defining \(\omega ^0\) to be position space facilitates the definition of virtual events; see the discussion below (24).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Funded by SCOAP3

About this article

Cite this article

Schust, P. Well-order as a construction principle for physical theories. Eur. Phys. J. C 79, 937 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1140/epjc/s10052-019-7456-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1140/epjc/s10052-019-7456-2