Abstract

The value of the Higgs boson mass plus the lack of signal at LHC13 has led to a naturalness crisis for supersymmetric models. In contrast, rather general considerations of the string theory landscape imply a mild statistical draw towards large soft SUSY breaking terms tempered by the requirement of proper electroweak symmetry breaking where SUSY contributions to the weak scale are not too far from \(m_{weak}\sim 100\) GeV. Such a picture leads to the prediction that \(m_h\simeq 125\) GeV while most sparticles are beyond current LHC reach. Here we explore the possibility that the magnitude of the Peccei–Quinn (PQ) scale \(f_a\) is also set by string landscape considerations within the framework of a compelling SUSY axion model. First, we examine the case where the PQ symmetry arises as an accidental approximate global symmetry from a more fundamental gravity-safe \(\mathbb {Z}_{24}^R\) symmetry and where the SUSY \(\mu \) parameter arises from a Kim-Nilles operator. The pull towards large soft terms then also pulls the PQ scale as large as possible. Unless this is tempered by rather severe (unknown) cosmological or anthropic bounds on the density of dark matter, then we would expect a far greater abundance of dark matter than is observed. This conclusion cannot be negated by adopting a tiny axion misalignment angle \(\theta _i\) because WIMPs are also overproduced at large \(f_a\). Hence, we conclude that setting the PQ scale via anthropics is highly unlikely. Instead, requiring soft SUSY breaking terms of order the gravity-mediation scale \(m_{3/2}\sim 10\)–100 TeV places the mixed axion–neutralino dark matter abundance into the intermediate scale sweet zone where \(f_a\sim 10^{11}\)–\(10^{12}\) GeV. We compare our analysis to the more general case of a generic SUSY DFSZ axion model with uniform selection on \(\theta _i\) but leading to the measured dark matter abundance: this approach leads to a preference for \(f_a\sim 10^{12}\) GeV.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The Standard Model (SM) is beset with several fine-tuning problems that call for new physics beyond the SM. These include:

- 1.

The gauge hierarchy problem [1, 2] wherein the weak scale \(m_{weak}\simeq m_{W,Z,h}\simeq 100\) GeV \(\sim 10^{-14}m_\mathrm{GUT}\) (where \(m_\mathrm{GUT}\simeq 2\times 10^{16}\) GeV).

- 2.

The cosmological constant (CC) problem [3] wherein the measured value of the cosmological constant \(\Lambda \simeq 10^{-120}m_P^4\) (where naively it is expected that \(\Lambda \simeq m_P^4\) with \(m_P\) being the reduced Planck mass).

- 3.

The strong CP problem [4] wherein the \(\bar{\theta }\) coefficient of the CP-violating \(\bar{\theta }(g_s^2/32\pi )G_{\mu \nu A}\tilde{G}_A^{\mu \nu }\) QCD Lagrangian term is \(\lesssim 10^{-10}\) times its expected value from the ’t Hooft theta vacuum solution to the \(U(1)_A\) problem [5, 6].

The most elegant solution to problem #1 is to extend the Poincare’ group of spacetime symmetries to include weak scale broken supersymmetry (WSS) [7,8,9] wherein all quadratic divergences to \(m_h^2\) necessarily cancel. WSS is in fact supported by four sets of measurements:

The measured values of the gauge couplings actually unify under Minimal Supersymmetric Standard Model (MSSM) evolution whereas they do not under SM evolution [10,11,12,13].

The measured value of the top quark mass is just right to generate a radiative breakdown of EW symmetry in the MSSM (assumed valid up to scales \(Q\simeq m_\mathrm{GUT}\)) [14,15,16,17,18,19,20].

The measured value of \(m_h\simeq 125\) GeV falls squarely within the narrow window of MSSM required values where \(m_h\lesssim 135\) GeV [21,22,23] and

the measured value of \(m_W\simeq 80.4\) GeV favors heavy WSS over the SM assuming the measured value of \(m_t\simeq 173.2\) GeV [24].

The value of the Higgs boson mass plus the lack of signal at LHC13 have led to a naturalness crisis for supersymmetric models [25]. The general impression has been set forth that weak scale SUSY, while perhaps not yet dead, may still be worth studying. This has led to renewed scrutiny of the basis of naturalness calculations within SUSY Effective Field Theories (EFTs) which adopt multiple independent soft parameters. While the multiple soft parameters are useful to parametrize our ignorance of SUSY breaking, in more fundamental models (such as string based constructions) then the soft terms are typically correlated which leads to very different values of fine-tuning. The electroweak fine-tuning measure \(\Delta _{EW}\) has been presented as a more conservative, model-independent measure which accounts for the case where all soft terms are inter-dependent. Using \(\Delta _{EW}\) [26, 27], fine-tuning analyses now require only \(m_{\tilde{g}}\lesssim 6\) TeV and \(m_{\tilde{t}_1}\lesssim 3\) TeV [27,28,29,30] as compared to present LHC limits that \(m_{\tilde{g}}\gtrsim 2\) TeV and \(m_{\tilde{t}_1}\gtrsim 1\) TeV.Footnote 1 In the MSSM, only higgsinos are required by naturalness to have weak scale masses, and these particles are very difficult (but not impossible) to see at LHC [35,36,37,38,39,40,41].

Some understanding of the magnitude of the cosmological constant has emerged from the string theory landscape of vacua solutions [42, 43]. In a discretuum [44] of vacua states with all possible values for \(\Lambda : -m_P^4\rightarrow +m_P^4\), then one expects \(\Lambda \) as large as possible subject to the requirement that galaxies be able to condense, which is a seeming precondition for a pocket universe containing sentient observers. Indeed, Weinberg [3, 45] used such reasoning to predict the value of \(\Lambda \) to within a factor of several of its value which was measured more than a decade later. Such an anthropic solution to the CC problem emerges naturally from string theory including a vast landscape of flux vacua, estimated as \(\sim 10^{500}\) such possibilities [46, 47].

The most elegant solution to the strong CP problem involves the introduction of a new global U(1) PQ symmetry [48, 49] which is spontaneously broken (SSB) at some scale \(f_a\sim 10^9-10^{16}\) GeV.Footnote 2 The (pseudo-)Goldstone boson which emerges from SSB, the axion a [51, 52], allows for a dynamical relaxation of the \(G\tilde{G}\) QCD Lagrangian terms to zero thus solving the strong CP problem. A remnant of the PQ procedure is the existence of a physical axion particle which also turns out to be a solid candidate for cold dark matter (CDM) in the universe [53,54,55,56,57,58]. Remnant axion CDM is being searched for at a variety of experiments, the most sensitive of which are the microwave cavity searches [59]. While the PQ axion solution to the strong CP problem is indeed compelling, it is beset by two problems of its own.

Global symmetries are not respected by gravitational interactions and thus the PQ symmetry is not expected to be fundamental [60,61,62,63]. Instead, PQ symmetry is expected to emerge as an accidental, approximate symmetry from some more fundamental gravity-safe symmetry. While string theory itself is gravity-safe, under compactification from 10 dimensions to a 4-d effective SUGRA field theory, then all allowed non-renormalizable 4-d operators are expected to be induced unless forbidden by some symmetry. Discrete R-symmetries can often emerge as a byproduct of compactification of the original 10-d Lorentz symmetry of the string action and so these are prime candidates to forbid the unwanted non-renormalizable terms that could spoil the axion solution to the strong CP problem. To be gravity-safe, the global \(U(1)_{PQ}\) symmetry should emerge as an accidental, approximate symmetry which arises from the more fundamental discrete R-symmetry. The resultant PQ symmetry must be of exceptionally high quality: the PQ breaking contributions to the axionic potential must be suppressed by at least eight powers of \(m_P\) [60, 61] in order for \(\bar{\theta }\lesssim 10^{-10}\): \(V_{PQB}\sim \phi ^{10}/m_P^8\) (where \(\phi \) stands for generic scalar fields). This is a very high bar to hurdle!Footnote 3

In string theory, many candidate axions can emerge, but with a PQ scale \(f_a\sim m_\mathrm{GUT}\) to \(m_\mathrm{string}\) [69, 70]. Meanwhile, cosmological (dark matter) constraints seem to require \(f_a\sim 10^{11}-10^{12}\) GeV [53,54,55,56,57,58]. A further problem then is: what accounts for the apparent suppression of the PQ breaking scale?

The goal of this paper is to examine the second of these axionic concerns in the context of the string theory landscape: can the magnitude of the PQ breaking scale be understood from landscape considerations within a well-motivated model for axion (and WIMP) dark matter? A number of previous works have also addressed this question and these will be briefly reviewed in Sect. 1.1. The first of the PQ concerns – gravity safety – was recently addressed within the context of anomaly-free (up to a Green–Schwarz term) discrete R symmetries which forbid the SUSY \(\mu \) term while respecting grand unification conditions [71, 72]. It was found in Ref. [73] that two closely related SUSY axion models – dubbed hybrid CCK [74] (hyCCK) and hybrid SPM [75,76,77] (hySPM) – were found to be gravity-safe under a \(\mathbb {Z}_{24}^R\) discrete R-symmetry which also led to

suppression of the SUSY \(\mu \) term,

suppression of the various renormalizable R-parity violating terms and

suppression of the dangerous dimension-5 proton decay operators,

all while allowing for see-saw neutrinos. In such a setting, the \(\mathbb {Z}_{24}^R\) symmetry (and resulting accidental approximate \(U(1)_{PQ}\) symmetry) are broken as a consequence of SUSY breaking. Thus, the PQ scale emerges as a derived value depending on the soft SUSY breaking terms. We will assume the hyCCK model in Sect. 2 and derive a probability distribution for the resulting magnitude of the PQ scale \(f_a\) for an assumed upper bound on the allowed dark matter abundance in pocket universes. Requiring a (pocket) universe without overproduction of mixed axion–WIMP dark matter by a (arbitrary) factor four excess beyond its measured value then leads to a most probable value of \(f_a\sim 10^{14}\) GeV. We also derive a probability distribution for the initial axion misalignment angle \(\theta _i\) which tends to favor smaller values of its expected range. Typically this leads to a large overproduction of dark matter beyond its observed value. If one assumes axion-only dark matter, then one may compensate for the large value of \(f_a\) by allowing for a small value of the initial axion misalignment angle \(\theta _i\sim 0\) [78]. In our approach, where SUSY stabilizes the weak scale and the \(\mathbb {Z}_{24}^R\) symmetry yields gravity-safety, then WIMPs are also overproduced and a tiny value of \(\theta _i\) cannot save the day for \(f_a \gtrsim 10^{14}\) GeV.

Some motivation for our approach comes from earlier analyses by Douglas which explored a statistical approach to the magnitude of the SUSY breaking scale. In Refs. [79, 80], it is assumed that all real-valued SUSY breaking scales are equally likely in a fertile patch of the landscape which contains the MSSM as the low energy effective theory. In the case of F-term SUSY breaking, since the F terms are complex-valued fields and the magnitude of SUSY breaking depends on the modulus of \(\langle F\rangle \), then one expects the magnitude of soft terms \(m_{soft}\sim m_{3/2}\sim m_{hidden}^2/m_P\) to enjoy a linearly increasing statistical distribution in the landscape. For a variety of hidden sector F and D-term fields contributing to SUSY breaking, then one expects instead \(m_{soft}^n\) where \(n=2n_F+n_D-1\) and where \(n_F\) is the number of contributing F-term SUSY breaking fields and \(n_D\) is the number of D-term SUSY breaking fields.Footnote 4

Naively, the increasing soft term prior would suggest soft terms most probably at energy scales far beyond the weak scale. However, Agrawal et al. [82, 83] have computed that if the weak scale is increasing by a factor of 2–5 beyond its measured value, then nuclear physics is modified in ways that are unlikely to lead to a livable universe (as we understand it). Requiring SUSY contributions to the weak scale to be within a factor of a few (four) of its measured value is the same as requiring the naturalness measure [26, 27] \(\Delta _\mathrm{EW}\lesssim 30\) [84]. (For a review of details, see the Appendix.) By requiring that the weak scalar potential is properly broken to \(SU(3)_C\times U(1)_{EM}\) and no contribution to the weak scale exceeds a factor four beyond the weak scale (in the presence of a natural value of \(\mu \sim 200\) GeV which emerges from our assumed solution to the SUSY \(\mu \) problem), then the distribution of soft terms becomes bounded from above. For the case of a mild \(n=1\) statistical draw on soft terms, then there is large mixing in the top-squark mass matrix leading to enhanced Higgs mass radiative corrections and hence \(m_h\simeq 125\) GeV whilst the gluinos and squarks are pulled beyond LHC search limits [85, 86]. An exception is the SUSY-preserving \(\mu \) term which directly contributes to the magnitude of the weak scale and thus must be of order \(\mu \sim 100\)–350 GeV. The \(\mu \) parameter leads to a rather light set of four higgsinos whose parameter space is only now beginning to be explored at LHC via the soft dilepton plus jet plus \(\not \!\!\!{E_T}\) signature [37,38,39,40,41]. Thus, in the SUSY landscape picture with a mild statistical draw towards large soft terms, the prediction is that the LHC will see exactly that which it does see: a light Higgs of mass \(m_h\simeq 125\) GeV with as yet no sign of sparticles [86].

1.1 Review of some previous work

Here, we briefly review some previous related works to give context for our directions.

In Ref. [78], Linde assumes a scenario where inflation continues past the PQ phase transition (which alleviates the axion domain wall problem) giving rise to a uniform axion field strength \(a\equiv \theta _i f_a\) throughout the observable universe. He argues that an increased value of initial axion field strength by a factor ten in pocket universes leads to an increase in matter content of galaxies by a factor \(\sim 10^8\) likely leading to conditions hostile to life as we know it. Since \(\Omega _a h^2\sim \theta _i^2 f_a^{7/6}\), then small values of \(\theta _i\) are favored and hence values of \(f_a\gg 10^{12}\) GeV can be accommodated.

In Hellerman and Walcher [87], the authors examine axion CDM and galaxy formation in a multiverse setting where all other parameters of \(\Lambda \)CDM models are fixed at the values of our pocket universe. By requiring structure formation before the onset of cosmological constant domination, the authors derive upper bounds on the ratio of dark matter-to-baryons \(\rho _{DM}/\rho _B\) which are typically of order \(10^4\)–\(10^5\) while our universe sits at the lower edge of allowed values \(\sim 5\). They conclude that anthropic constraints are unlikely to explain our observed value of \(\rho _{DM}/\rho _B\sim 5\).

In Wilczek and in Tegmark et al. [88, 89], a model with axion-only CDM is assumed where PQ breaking occurs before the end of inflation. For uniform sampling of \(\theta _i\), then the prior distribution of axion CDM is the mild distribution \(f(\rho _\mathrm{CDM})\sim 1/\sqrt{\rho _\mathrm{CDM}}\). Imposing anthropic limits from galaxy formation, star and black hole formation, solar system stability and stiff upper limits on the density of habitable halos, then it is found that the measured DM density is comparable to expectations from the multiverse.

Freivogel [90] adopts the same axion-only CDM model as in Ref. [89] but then uses Bousso’s causal diamond measure to provide selection constraints. He fixes \(\rho _B/\rho _{\gamma }\) to its observed value, fixes \(f_a\gg 10^{12}\) GeV and allows only the misalignment angle \(\theta _i\) to vary uniformly and calculates the probability of observing a particular value of \(\xi =\rho _\mathrm{DM}/\rho _B\) which is allowed to vary. He finds 68% of observers see \(\xi \le 15\) and 95% of observers see \(\xi \le 65\). In our pocket universe with \(\xi \sim 5\), he concludes that the observed value of \(\xi \) is then reasonable. However, it is not completely improbable to observe \(\xi \) values different from our universe.

Some related papers [91,92,93,94] argue that comparable values for \(\Omega _\Lambda \) and \(\Omega _\mathrm{DM}\) should emerge from the multiverse.Footnote 5

In these works, a particularly parsimonious approach – of the SM amended with a simple axionic extension – is adopted. While admittedly simple, it contains two problems which make them likely unrealistic. First, there is nothing in them to stabilize the weak scale, and thus we would expect a value for the weak scale far beyond its measured value. The inclusion of WSS solves this problem. Second, it is well known that the global \(U(1)_{PQ}\) needed for an axionic solution to the strong CP problem is intrinsically incompatible with the inclusion of gravitation and with embedding in string theory in particular. In the following, we adopt a particular SUSY axion model based upon a more fundamental discrete R-symmetry which may arise from compactification of extra space dimensions in string theory. For a strong enough discrete symmetry, in this case \(\mathbb {Z}_{24}^R\), then the emerging accidental, approximate global PQ symmetry is sharp enough such as to allow for the PQ solution to the strong CP problem.

2 Probability distributions for the PQ scale and \(\theta _i\) from a SUSY axion model based upon a gravity-safe \(\mathbb {Z}_{24}^R\) symmetry

In this section, we first introduce the gravity-safe hyCCK SUSY axion model where the global PQ symmetry emerges as an accidental, approximate global symmetry from a more fundamental \(\mathbb {Z}_{24}^R\) symmetry. The hyCCK model as used here is perhaps the most simple and plausible gravity-safe SUSY axion model and should serve as a stand-in for whatever (perhaps more complicated) mechanism nature adopts which solves the gauge hierarchy problem, the strong CP problem, the SUSY mu problem and suppression of proton-decay operators while at the same time generating the needed R-parity conservation and PQ symmetry.

Next, we review calculation of the mixed axion–WIMP dark matter abundance using eight coupled Boltzmann equations. Then, we combine statistical selection of the PQ scale with the requirement against overproduction of dark matter within pocket universes which populate an eternally-inflating [98] multiverse to derive probability distributions for the magnitude of the PQ energy scale and also for the initial axion misalignment angle \(\theta _i\).

2.1 MSSM augmented by gravity-safe PQ sector based on \(\mathbb {Z}_{24}^R\) discrete R-symmetry

In Ref. [85], probability distributions for Higgs and sparticle masses were derived from the string landscape assuming Douglas’ [79, 80] \(m_{soft}^n\) (with \(n=0,1,2\)) soft term prior coupled with a veto \(\Theta (30-\Delta _\mathrm{EW})\) on non-standard vacua or too large of SUSY contributions to the weak scale. The \(n=1\) sampling generates a probability distribution for \(m_h\) which peaked at \(m_h\simeq 125\) GeV while sparticle mass predictions were characterized by

- 1.

\(m_{\tilde{g}}\sim 4\pm 2\) TeV,

- 2.

\(m_{\tilde{t}_1}\sim 1.5\pm 0.5\) TeV,

- 3.

\(m_A\sim 3\pm 2\) TeV,

- 4.

\(m_{\widetilde{\chi }^{\pm }_1,\widetilde{\chi }^0_{1,2}}\sim 200\pm 100\) GeV and

- 5.

\(m_{\tilde{q},\tilde{\ell }}\sim 20\pm 10\) TeV.

In accord with these results, we will adopt for illustrative purposes a SUSY benchmark point from the NUHM3 model [99,100,101,102,103,104] with parameters \(m_0(1,2)=16\) TeV, \(m_0(3)=5\) TeV, \(m_{1/2}=1.5\) TeV, \(A_0=-7\) TeV, \(\tan \beta =10\) with \(\mu =200\) GeV and \(m_A=3\) TeV. We generate sparticle mass spectra using Isajet 7.88 [105] and find the spectra provided in Table 1 and labelled as landSUSY (landscape SUSY). The spectra lie well within the landscape SUSY predictions for an \(n=1\) mild draw to large soft terms [85]. Our final results will hardly depend on significant deviations from the landSUSY benchmark model which mainly sets a natural value for the \(\mu \) parameter and the saxion and axino branching fractions which enter into the relic density calculation.

We will augment the landscape SUSY spectra with a PQ sector from the hybrid CCK [74] model where the superpotential is given by

where we have introduced MSSM singlet fields X and Y with PQ charges listed in Table 2. The hyCCK model is thus a particular example of a SUSY DFSZ axion model where PQ field X couples to the two Higgs doublets thus providing a solution to the SUSY \(\mu \) problem.Footnote 6 The model assumes an underlying \(\mathbb {Z}_{24}^R\) discrete R symmetry which forbids 1. renormalizable RPV terms, 2. the usual \(\mu \) term and 3. dimension-5 proton decay operators while allowing the required Yukawa couplings and see-saw neutrino terms [71, 72]. The lowest order PQ breaking superpotential terms are \(X^8Y^2/m_P^7\), \(Y^{10}/m_P^7\) and \(X^4Y^6/m_P^7\) leading to lowest order scalar potential terms suppressed by powers of \(m_P^8\): thus, the underlying \(\mathbb {Z}_{24}^R\) symmetry renders the model gravity-safe according to the KM-R requirements [60, 61]. The required \(U(1)_{PQ}\) symmetry arises as an accidental approximate global symmetry which arises from an underlying more fundamental discrete \(\mathbb {Z}_{24}^R\) symmetry.

The scalar potential for hyCCK, augmented with the corresponding soft SUSY breaking terms, is given by

Minimization conditions for the hyCCK model can be found in Ref. [106]. The scalar potential develops a non-zero minimum at \(\langle \phi _X\rangle \equiv v_X\) and \(\langle \phi _Y\rangle \equiv v_Y\) for a sufficiently large soft term \(-A_f\), thus breaking the underlying \(\mathbb {Z}_{24}^R\) and accidental, approximate PQ symmetries. The PQ breaking vev is given by \(v_{PQ}=\sqrt{v_X^2+9v_Y^2}\) where then \(f_a=\sqrt{2}v_{PQ}\). In accord with expectations from supergravity models, we will assume \(m_X=m_Y=m_{\tilde{a}}=m_s\equiv m_{3/2}\) [107, 108]. Thus, in this model, the PQ scale is a derived consequence of SUSY breaking.

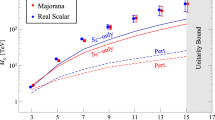

The calculated value of \(f_a\) is given in Fig. 1 as a function of the \(-A_f\) soft term assuming various values of \(m_X=m_Y=m_0(1,2)\equiv m_{3/2}\) and three different values of f. From Fig. 1, we see that \(f_a\) has a monotonically increasing value with increasing \(|-A_f|\). For a particular value of \(-A_f\) and \(m_X=m_Y=m_0(1,2)\equiv m_{3/2}\) if the value of f is reduced by a factor of 2, then \(f_a\) increases by approximately \(41\%\) and if the value of f is increased by a factor of 2, then \(f_a\) decreases by approximately \(41\%\). Since \(-A_f\) doesn’t contribute directly to the determination of the weak scale, then there is no (anthropic) upper bound on its value and one might expect \(-A_f\) and hence \(f_a\) to lie far beyond the well-known cosmological sweet spot where \(f_a\sim 10^{11}\)–\(10^{12}\) GeV [53,54,55,56,57,58]. Thus, we will adopt as a hypothesis a variable and independent \(-A_f\) soft parameter which is statistically selected to be as large as possible and which sets the magnitude of the PQ breaking scale as a consequence of SUSY breaking.Footnote 7

2.2 Relic density of mixed axion–WIMP dark matter

The evaluation of mixed axion–WIMP dark matter from SUSY axion models is more complicated than simply adding the WIMP thermal abundance to the coherent-oscillation-produced axions. To evaluate the mixed neutralino–axion relic density, we apply the eight-coupled-Boltzmann equation computer code developed in Refs. [109,110,111]. For brevity, we will not reproduce here the eight coupled Boltzmann equations which can instead be found in Ref. [109, 110]. The code relies on the IsaReD [112] calculation of \(\langle \sigma v\rangle (T)\) which is a crucial input to the coupled Boltzmann calculation. Starting from the time of re-heat with temperature \(T_R\) at the end of the inflationary epoch, the computer code tracks the coupled abundances of radiation (i.e. SM particles), neutralinos, axinos, gravitinos, saxions and axions (the latter two consists of both thermal/decay-produced and coherent oscillation-produced (CO) components).

The CO-produced abundance of axions is determined in part by the axion field initial misalignment angle \(\theta _i\) [53,54,55,56,57,58]. For numerical analyses, we adopt a simple formula

where \(f(\theta _i )=\left[ \log \left( e/(1-\theta _i^2/\pi ^2)\right) \right] ^{7/6}\) is the anharmonicity factor [58] and \(N_\mathrm{DW}\) is the domain wall number (\(=6\) for the DFSZ model). In previous work the initial misalignment angle \(\theta _i\) is adjusted to gain the measured value of the relic abundance. In the current work, we will allow for a uniform distribution of \(\theta _i: 0-\pi \) values since we are scanning over many pocket universes which arise as subuniverses of the more vast multiverse.

A plot of various energy densities \(\rho \) vs. scale factor \(R/R_0\) starting from \(T_R=10^7\) GeV until the era of entropy conservation from our eight-coupled Boltzmann equation solution to the mixed axion–neutralino relic density in the SUSY DFSZ model for the landscape SUSY benchmark point. We take \(\xi _s=1\). The corresponding temperature T is denoted by the dashed green line where in this case the y-axis is interpreted as T in GeV

In Fig. 2 we show the energy densities of various species vs. scale factor \(R/R_0\) that influence the ultimate dark matter abundance for the landscape SUSY benchmark point landSUSY in Table 1. Here, \(R_0\) is the reference scale factor at the beginning of re-heat and the corresponding temperature T is shown by the dashed green line (where instead the y-axis is interpreted as temperature in GeV). We take \(T_R=10^7\) GeVFootnote 8 and \(f_a=s_0=10^{12}\) GeV and where \(s_0\) denotes the initial saxion field value. We also take \(m_{\tilde{a}}=m_s=m_{3/2}=16\) TeV. The blue curve denotes the neutralino abundance which freezes out at \(R\sim 10^6 R_0\) or \(T\sim 10\) GeV. The saxion and axion contributions are split into their thermally- and decay-produced components and their coherent-oscillation (CO) produced components. Saxions decay around \(R\sim 10^5R_0\) (\(T\sim 10\) GeV) whilst axinos decay around \(R\sim 10^6R_0\) ( or \(T\sim 1\) GeV). The saxion decays depend on a model dependent coupling \(\xi _s\) which governs the saxion decay rate \(s\rightarrow aa\) and \(s\rightarrow \tilde{a}\tilde{a}\) [109, 110]. We take \(\xi _s=1\) so these decays are turned on. (Of course, for our case the \(s\rightarrow \tilde{a}\tilde{a}\) decay is not kinematically open so s decays mainly to aa but also to other MSSM particles). CO-produced axions (brown curve) start to oscillate around \(T\sim 1\) GeV and become the dominant component of dark matter as one enters the era of entropy conservation on the right-hand-side of the plot. Due to late decays of axinos, which occur after neutralino freeze-out, the neutralino abundance increases to \(\Omega _{\widetilde{\chi }^0_1}h^2 \simeq 0.02.\)

Relic density of axion and higgsino-like WIMP DM versus \(f_a\) for the landSUSY benchmark point with \(\theta _i=1\). The red curve denotes the sum of axion plus WIMP dark matter while green denotes the separate axion abundance and the blue curve denotes the separate WIMP abundance. The curves become brown when \(\Delta N_\nu ^{eff}>1\)

To gain some perspective on the expected relative abundances of mixed axion–WIMP dark matter, in Fig. 3 we show the relic density of mixed axion–WIMP dark matter vs. \(f_a\) for the landSUSY benchmark point and with \(T_R=10^7\) GeV and \(m_s=m_{\tilde{a}}=m_{3/2}=16\) TeV and where \(\theta _i=\theta _s=1\).Footnote 9 The green curve corresponds to the axion relic density while the blue curve corresponds to the WIMP relic density. The red curve shows the total relic density. We see that for low values of \(f_a\), the axion relic density – arising here from coherent oscillations corresponding to Eq. (3) – is highly suppressed. Also, the thermally-produced WIMP dark matter is highly suppressed due to the higgsino-like nature of the LSP which enhances its annihilation rate. The WIMP relic density is also highly suppressed by co-annihilations with the slightly heavier higgsinos \(\widetilde{\chi }^{\pm }_1\) and \(\widetilde{\chi }^0_2\). Thus, for \(f_a\sim 10^{10}\)–\(10^{12}\) GeV, we expect typically an under-production of mixed axion-higgsino DM. As \(f_a\) increases, the CO-produced axions steadily increase while WIMPs remain at their thermally-produced level. By \(f_a\sim 10^{12}\) GeV, the axino and saxion decay rates are sufficiently suppressed (by \(\Gamma _{\tilde{a},s}\sim 1/f_a^2\)) that they begin decaying into higgsinos after WIMP freeze-out, thus augmenting the WIMP abundance with a non-thermal, decay-produced component. By \(f_a\sim 3\times 10^{12}\) GeV, then the mixed axion–WIMP abundance saturates the measured value \(\Omega _\mathrm{CDM}h^2\simeq 0.12\), and where at this point CDM consists nearly equally of axions along with a comparable thermal and non-thermal WIMP component. In this region, the non-thermal WIMP component arises mainly from thermal axino production followed by late \(\tilde{a}\) decays in the early universe. As \(f_a\) increases further, the thermal axino production rate falls off rapidly so that the WIMP abundance levels off. For even higher values of \(f_a\gtrsim 10^{14}\) GeV, saxion production via COs becomes large and so saxion-decay produced WIMP production rapidly rises. In addition, the \(s\rightarrow aa\) decays sharply increase the already over-produced axions. These relativistic axions also lead to violation of limits on relativistic species present in the early universe characterized in terms of the effective number of neutrinos parameter \(\Delta N_{\nu }^{eff}\) which we take (very conservatively) to be \(\lesssim 1\) (brown curve).Footnote 10 For \(f_a\gtrsim 2\times 10^{15}\) GeV, then entropy dilution of all relics from CO-produced saxions can suppress the mixed axion–neutralino relic abundance.

In terms of the string theory landscape, we see that allowing values of \(f_a\sim m_\mathrm{GUT}\) could lead to dark matter overproduction by a factor of \(\sim 10^4\) compared to its measured value. As noted by Linde and others, it might be hard to visualize the existence of observers in a universe with such an overabundance of dark matter. Precisely how much of an overabundance of dark matter is anthropically too much is an open question. But clearly, if such a limit exists, then it would place an upper limit on the value of \(f_a\). Even requiring a modest factor of four overabundance, indicated by the dashed gray horizontal line, would already require a value \(f_a\lesssim 10^{13}\) GeV. This upper bound is well below the expected magnitude for \(f_a\) from string theory where instead \(f_a\sim 10^{16}\)–\(10^{18}\) GeV is typically expected [114]. The bound on \(f_a\) from the axion abundance may be considered a softer bound since it is possible to lower the axion abundance with a smaller value of \(\theta _i\sim 0\) (although if \(\theta _i\) scans on the landscape, then \(\theta _i\sim 1\) is to be expected). However, we see that a bound on \(f_a\) still obtains from the WIMP contribution to \(\Omega _{a\widetilde{\chi }^0_1}h^2\), although this bound on WIMP overproduction occurs at over an order of magnitude higher values: in Fig. 3, \(f_a\lesssim 10^{14}\) GeV occurs from just overproduction of the WIMP component of dark matter.

In Fig. 4, we show the total mixed WIMP plus axion dark matter abundance but this time assuming \(T_R=10^6\) GeV and \(10^8\) GeV with \(\theta _i=0.1,\ 0.5,\ 1\) and 2. For \(T_R\gtrsim 10^9\) GeV, thermal production and late decay of gravitinos can lead to conflict with bounds from late-decaying neutral particles in the early universe: in this case, the gravitino problem [115, 116]. We see that for different \(\theta _i\) values the upper limit on \(f_a\) can move around by typically an order of magnitude: nonetheless, an upper bound on \(f_a\) from overproduction of dark matter should obtain which is still much less than the the string/GUT scale. We also show variation in the \(a-\widetilde{\chi }^0_1\) dark matter relic density versus varying \(T_R\). For the DFSZ axion model, the axino and saxion production rates in the early universe hardly depend on \(T_R\) [117, 118] (unlike the case of the KSVZ axion model [119]). Some variation in relic density is seen for \(f_a\gtrsim 10^{14}\) GeV where gravitino production, which does depend on \(T_R\) [120], becomes important and augments the non-thermal WIMP abundance.

2.3 PQ scale from the landscape

In this Subsection, we investigate whether landscape considerations can determine the magnitude of the PQ scale \(f_a\). We assume an \(n=1\) statistical draw towards large soft terms \(-A_f\) which in turn leads to large PQ scales along the lines of Fig. 1 where the PQ scale is related to the breakdown of supersymmetry. For our landscape benchmark point landSUSY, the magnitude of \(f_a\) is determined by the quartic soft term \(A_f\). However, since \(-A_f\) is not connected with EWSB, then it need not be susceptible to the same bounds on MSSM soft terms that emerge from requiring an appropriate breakdown of electroweak symmetry with independent contributions to \(m_{weak}\) not more than a factor of a few from its value \(m_{weak}\simeq 100\) GeV. Instead, the PQ scale \(f_a\) is intimately related to the production of both axion dark matter and (natural) higgsino-like WIMP dark matter.

Since we are working within a multiverse scenario wherein each pocket universe may have different laws of physics, and the multiverse is an expression of the universe emerging from a spacetime continuum characterized by eternal inflation, then of course inflationary cosmology is an essential component of our overall scheme. In inflationary cosmology, the universe has an early exponential expansion phase which drives the universe to flatness, which requires an overall energy density teetering on the boundary between an open or a closed universe. Such a universe is characterized by the overall energy density lying at its critical closure density:

and where \(\Omega _{curv}=0\) for an inflationary universe which gives rise to a flat geometry. For our pocket universe, the measured value of the Hubble constant is \(H_0=100 h\) km/s/Mpc with \(h=0.678\pm 0.009\) but for other pocket universes then \(H_0\) will be different depending on the various constituencies. We will adopt as usual \(\rho _B/\rho _\gamma \) equal to the value of our universe since we are assuming a “friendly” fertile patch of the multiverse where the SM remains as the low energy effective theory.Footnote 11 Thus, in the fertile patch of multiverse assumed here, only \(\Lambda \), \(m_{soft}\) and \(\theta _i\) are assumed to scan. The scanning of the soft term \(A_f\) sets the value of \(f_a\) for otherwise fixed values of scalar masses as expected for our landSUSY benchmark point: i.e. we assume a common value of all scalar masses \(m_0(1,2)=m_X=m_Y\equiv m_{3/2}\). We also allow for non-universal generations \(m_0(3)\ll m_0(1,2)\).Footnote 12

The generated probability distribution for \(-A_f\) is shown in Fig. 5a, which is seen to rise linearly as expected. For a given value of \(A_f\), then the value of \(f_a\) is determined by the minimization conditions arising from Eq. (2). In frame (b), we show the derived distribution \(dP/df_a\). Here, the probability distribution is seen to favor the highest values of \(f_a\) possible, which would be generated from very large values of \(-A_f\).

At this point, our prior distribution for \(f_a\) is set, but we will also need some selection criterion to avoid \(f_a\) exploding up to huge values, leading to perhaps a gross overproduction of dark matter. Thus, the question now is: how much dark matter is too much dark matter for our fertile patch of pocket universes within the greater multiverse? Some of the papers of Sect. 1.1 have entertained values of \(\rho _{DM}/\rho _B\) as high as 25–100.

For illustrative purposes, we will consider the effect of limiting pocket universes to a modest bound of four times greater dark matter density than in our universe: suppose \(\Omega _\mathrm{DM}h^2\lesssim 0.48\). Such a bound would saturate the case where we maintain our measured value of \(\rho _c\) but allow the dark matter abundance to nearly saturate \(\rho _c\) at the expense of a dark energy component. Such models were commonly contemplated before the discovery of a non-zero dark energy component.

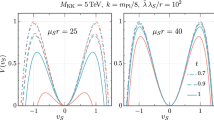

In Fig. 6a, we show the resulting probability distribution \(dP/df_a\) which results from an \(n=1\) draw on \(-A_f\) coupled to an anthropic/cosmological selection bound \(\Omega _{a\widetilde{\chi }^0_1}h^2<0.48\) (green curve). Even with our proposed modest selection bound, we see that the value of \(f_a\) is driven to its nearly maximal value such as to avoid overproduction of dark matter. From the plot, we would expect that a value of \(f_a\sim 10^{14}\) GeV or only somewhat lower, with a rather sharp cutoff \(f_a\lesssim 8\times 10^{13}\) GeV. For comparison, we also show the black histogram where we instead require that the upper bound on dark matter abundance is only slightly beyond our measured value: \(\Omega _\mathrm{DM}<0.15\). This case would prefer \(f_a\sim 5\times 10^{12}\) GeV.

Let us compare the results of Fig. 6a with those of Fig. 7 which shows the allowed mixed axion–WIMP dark matter abundance for our landSUSY benchmark point in the generic SUSY DFSZ axion model while scanning uniformly over \(\theta _i\) and uniformly over \(\log (f_a)\). From Fig. 7, we see that for \(f_a\sim 10^{13}\)–\(10^{14}\) GeV, we are already overproducing dark matter compared to our universe with \(\Omega _\mathrm{DM}h^2=0.12\). There is only a miniscule probability to obtain from Fig. 6a \(f_a\) values low enough to match the measured value, which occurs for \(f_a\sim 10^{11}\)–\(\sim 4\times 10^{12}\) GeV. In the references from Sect. 1.1, large values of \(f_a\sim 10^{14}\)–\(10^{16}\) GeV could be compensated for by selecting on small values of \(\theta _i\). For our case of natural mixed axion–WIMP dark matter, this compensation is not permitted because large \(f_a\) also leads to large (non-thermal) overproduction of WIMP dark matter via delayed axino and saxion decays in the early universe. From Fig. 6a, we would expect that if the landscape is involved in determining the PQ scale \(f_a\), then its value should be very near the maximally allowed abundance of DM in pocket universes such as to allow observers to exist. But it is hard to believe that our pocket universe’s value of dark matter abundance is nearly anthropically maximal (as depicted by the black curve of Fig. 6a).

In Fig. 6b, we show the corresponding distribution \(dP/d\theta _i\) from the \(n=1\) pull on soft terms coupled with our modest anthropic veto that \(\Omega _\mathrm{DM}h^2<0.48\). The plot shows a probability that \(\theta _i\) is peaked around its smallest allowed values. This is easy to understand in that while the landscape prior strongly favors large values of \(f_a\), from Eq. (3) we see that overproduction of axions can be avoided by selecting only those vacua with correspondingly tiny values of \(\theta _i\). This effect is easily understood from Fig. 8 where we show regions of the \(\theta _i\) vs. \(f_a\) plane for our landSUSY benchmark point which lead to \(\Omega _\mathrm{DM}h^2<0.48\) (green points) or \(\Omega _\mathrm{DM}h^2>0.48\) (yellow points). The brown points denote where also \(\Delta N_{eff}>1\). From the figure, we see that for large \(f_a\sim 8 \times 10^{13}\) GeV, only a small range of \(\theta _i\) allows for non-overproduction of dark matter. And once \(f_a\gtrsim 8 \times 10^{13}\) GeV, then no value of \(\theta _i\) is possible which allows one to avoid DM overproduction.

3 Prediction of PQ scale from generic SUSY DFSZ axion model with uniform scan on \(\theta _i\)

In Sect. 2, we adopted a particular gravity-safe SUSY axion model based on a \(\mathbb {Z}_{24}^R\) discrete R-symmetry and the hyCCK superpotential Eq. (1) to show that a statistical draw towards large soft terms also yields a draw to large PQ breaking scale \(f_a\). The value of \(f_a\) gains an upper bound by requiring no overproduction of dark matter. For the modest assumption of less than a factor four times the measured abundance of dark matter, then we found \(f_a\sim 10^{14}\) GeV which is well below the values expected from pre-landscape string theory but which typically leads to much more dark matter production than we observe in our universe.

In this Section, we try to be more general by eschewing a particular SUSY axion model and instead assume a generic SUSY DFSZ axion model [109, 110] where \(f_a\) is an input instead of an output parameter. In this case, we will adopt a uniform distribution in \(\theta _i\) in accord with expectations from the landscape, but then require that the dark matter abundance lie at its measured value: \(\Omega _{a\widetilde{\chi }^0_1}h^2=0.12\). From this, we can then determine the necessary value of \(f_a\) such that, for scanned values of \(m_{\tilde{a}}\), \(m_s\) and \(m_{3/2}\), the measured abundance of mixed axion–neutralino dark matter is obtained. We will scan uniformly over each of \(m_{\tilde{a}},\ m_s\) and \(m_{3/2}:1-50\) TeV.

In a, we plot the value of \(\Omega _{\widetilde{\chi }^0_1}h^2\) versus \(f_a\) from a uniform scan over \(\theta _i: 0\rightarrow 3.14\) (and \(m_{\tilde{a}}\), \(m_s\) and \(m_{3/2}\)). In b, we show the corresponding correlation of \(\theta _i\) vs. \(f_a\). In c, we show the ensuing probability distribution for \(f_a\). In d, we show the probability distribution in \(\theta _i\) after selection effects. In all the frames, we require the total abundance of DM to equal its measured value: \(\Omega _{a\widetilde{\chi }^0_1}h^2=0.12\).

For a SUSY benchmark point within a two-component dark matter framework, direct and indirect WIMP dark matter searches can put a stringent upper limits upon the neutralino density which are more severe than the measured value, \(\Omega _\mathrm{DM}h^2=0.12\). In many cases, indirect DM detection (IDD) offers the most contraining limits on the non-thermal, decay-produced neutralinos for models with thermally underproduced higgsino-like neutralinos. In natural SUSY models from the \(n=1\) landscape, thermally produced neutralinos typically make up 5–20% of the total CDM density which renders them safe from Fermi-LAT+MAGIC [123] limits on overproduction of gamma rays in dwarf spheroidal galaxies [124]. In Fig. 9, we show the allowed percentage of WIMP dark matter compared to \(m_{\widetilde{\chi }^0_1}\) along with the Fermi-LAT+MAGIC IDD limit for our landSUSY benchmark point. If we increase \(\mu \sim 340\) GeV, then \(m_{\widetilde{\chi }^0_1}\sim 340\) GeV and all generated points would be Fermi-LAT+MAGIC allowed. The gray-shaded region shows the excluded WIMP composition for all landSUSY points within a good approximation.

In Fig. 10, we work within the SUSY DFSZ axion model using again our landSUSY benchmark point but with input parameters \(m_s,\ \theta _s,\ \theta _i,\ f_a,\ T_R\) and \(m_{3/2}\). Here, we fix \(T_R=10^7\) GeV and \(\theta _s=1\) but allow \(m_s\), \(m_{\tilde{a}}\) and \(m_{3/2}\) to scan over the range given above with a uniform scan on \(\theta _i\) and a log prior scan on \(f_a\). We only accept solutions with \(\Omega _{a\widetilde{\chi }^0_1}h^2=0.12\). We show the parameter space with augmented neutralino densities \(\Omega _{\widetilde{\chi }^0_1}h^2 < 0.12, 0.06\) and 0.03 with black, orange and purple colors respectively. We impose an upper limit on \(\theta _i\) (\(\theta _i < 3.14\)) so that the highly fine-tuned region \(\theta _i \simeq \pi \) is not present in our analysis.

In Fig. 10 frame (a), the resulting abundance of neutralino dark matter is shown while the remainder of DM is made of DFSZ axions. The horizontal line around \(f_a \lesssim 10^{11}\) GeV is just the expected thermal abundance of 200 GeV higgsino-like WIMP dark matter. For higher \(f_a > 10^{11}\) GeV, then non-thermal LSP production begins to occur where axinos can be produced in the early universe and decay to LSPs after neutralino freeze-out. There is a gap around \(f_a\sim 10^{13}\) GeV where axino decays are still contributing to the neutralino density. For \(f_a\sim 10^{14}\) GeV, points again become allowed due to diminished thermal production of axinos in the early universe. The WIMP abundance increases for \(f_a\gtrsim 10^{14}\) GeV due to increasing CO-production of saxions which then decay (in part) to WIMPs [109, 110]. An upper limit of \(f_a\lesssim 2\times 10^{14}\) GeV ensues in this case since for large \(f_a\), the DM is always overproduced. There is no conflict here with Fig. 7 since in this case with random values of \(m_s\) and \(m_{\tilde{a}}\), then relative axino and saxion production and decay rates can vary which leads to allowed points for \(f_a\sim 10^{14}\) GeV.

The corresponding correlation of \(\theta _i\) with the required value of \(f_a\) to make \(\Omega _{a\widetilde{\chi }^0_1}=0.12\) is shown in frame (b). Here, large values of \(\theta _i\) are correlated with low values of \(f_a\) to boost the axion production to gain accord with the measured relic abundance. For very large \(f_a\), then consequently small values of \(\theta _i\) are required to allow for \(\Omega _{a\widetilde{\chi }^0_1}h^2=0.12\).

In frame (c), we show the resulting probability distribution \(dP/df_a\) versus \(f_a\). Including all points with the measured abundance, then one obtains the black histogram which peaks around \(f_a\sim 2 \times 10^{12}\) GeV but with a tail extending to over \(10^{14}\) GeV. For the cases in which neutralino makes less than half of the measured DM density, the peak shifts to lower values of \(f_a\) (orange and purple histograms) with a small probability at high \(f_a\).

In frame (d), we show the probability distribution \(dP/d\theta _i\) for the three cases considered. Here, the black histogram is almost uniform across its range whilst the orange histogram displays a gap at small \(\theta _i\) where no allowed solutions occur. The high \(f_a\) region does not show up for \(\Omega _{\widetilde{\chi }^0_1}h^2 \lesssim 0.04\) and \(\theta _i\) can only take values greater than \(\sim \)1 when the neutralino makes less than 25% of the total DM abundance (purple).

4 Conclusions

In this paper we have sought to answer the question: is the magnitude of the PQ scale \(f_a\) set by the landscape, or by something else? To address this question, we have adopted the scenario advocated by Douglas wherein the soft terms are statistically favored by a prior distribution \(m_{soft}^{2n_F+n_D-1}\) and where we take the value \(n=2n_F+n_D-1=1\) (i.e. a linear distribution favoring large soft SUSY breaking terms). Along with this prior distribution, we invoke a selection criteria that vetos models with inappropriate EW breaking (CCB minima or no EWSB) and vetos models with contributions to the weak scale \(\gtrsim 4\) (corresponding to \(\Delta _\mathrm{EW}>30\)) in accord with nuclear physics constraints derived by Agrawal et al. on anthropically allowed values for the weak scale. Such an approach receives support in that previously it has been shown that \(n=1\) (or 2) has a most probable Higgs mass of \(m_h\simeq 125\) GeV whilst lifting sparticle masses beyond the reach of Run 2 of the LHC.

We implement this approach within a highly motivated SUSY axion model labeled as hyCCK. We feel this is an improvement upon previous work in that the model 1. stabilizes the weak scale via SUSY, 2. solves the strong CP problem via a gravity-safe \(\mathbb {Z}_{24}^R\) discrete symmetry which gives rise to an accidental, approximate global \(U(1)_{PQ}\), 3. solves the SUSY \(\mu \) problem [125] via the presence of a Kim-Nilles superpotential [126] and 4. explains R-parity conservation and proton stability as consequences of the more fundamental \(\mathbb {Z}_{24}^R\) which could arise from compactification of extra space dimensions in string theory. By choosing a MSSM benchmark point in accord with \(n=1\) landscape predictions and allowing for the PQ soft term \(-A_f\) to scan linearly and to set the magnitude of the PQ scale \(f_a\), then we find that as large as possible values of \(f_a\) are statistically preferred. In this approach, typically both WIMP and axion dark matter are overproduced. Axions are overproduced via vacuum misalignment at \(f_a\gg 10^{12}\) GeV unless the large value of \(f_a\) is compensated for by a small value of \(\theta _i\). However, since WIMPs are also overproduced at large \(f_a\), due to axino and saxion production coupled with delayed decays to SUSY LSPs after neutralino freeze-out (i.e. non-thermal WIMP production), then even with small \(\theta _i\) one cannot avoid overproduction of mixed axion–WIMP dark matter. From this approach, using even a modest DM overproduction bound of a factor four, then there is only a tiny probability to gain the measured value of dark matter density in our own pocket universe. Thus, the answer to the question posed in the title is: No, in our well-motivated landscape SUSY model based upon gravity-safe, electroweak natural hyCCK SUSY axion model, the magnitude of the PQ scale is highly unlikely to be set by the landscape.

Instead, an alternative but perhaps underappreciated mechanism is available to set the magnitude of the PQ scale. This is that in generic supergravity models with hidden sector SUGRA breaking via the superHiggs mechanism, then soft terms arise from SUGRA breaking with magnitudes of order the gravitino mass \(m_{3/2}\). For a well-specified hidden sector, then the soft terms are all calculable and correlated. For our landscape SUSY model with \(m_0(1,2)\sim m_{3/2}\), we would also expect \(-A_f\sim m_{3/2}\sim 10\)–100 TeV. This places us from Fig. 1 into the zone where \(f_a\sim 10^{11}\)–\(10^{12}\) GeV which is the sweet spot for generating a thermal underabundance of higgsino-like WIMP dark matter but with mainly SUSY DFSZ axion dark matter.

In Sect. 3, we implemented instead a uniform scan over \(\theta _i\) and a scan over independent \(m_{\tilde{a}}\), \(m_s\) and \(m_{3/2}\) values with the corresponding \(f_a\) value such that \(\Omega _{a\widetilde{\chi }^0_1}h^2=0.12\). In this case, we are pushed to the cosmological sweet spot where \(f_a\simeq 10^{11}\)–\(10^{13}\) GeV.

From our overall approach, we understand why WIMPs haven’t yet been detected: it is because they make up only a small portion of the total dark matter. In addition, even though the non-thermal decay-production of WIMPs is allowed for, more than 40% of the points in Fig. 10a (Sect. 3) still have the same neutralino abundance as the thermally-produced value. Nonetheless, WIMP discovery should be possible at multi-ton noble liquid direct WIMP detection experiments [127]. Axions – while likely to make up the bulk of dark matter – are much more difficult to detect since the presence of higgsinos in their \(g_{a\gamma \gamma }\) coupling diagram suppresses their detection rate compared to KSVZ or non-SUSY DFSZ axion models [124]. Meanwhile, sparticle detection may be possible at HL-LHC via the soft OS dilepton+jet+MET channel which arises from direct higgsino pair production [37,38,39,40,41]. Detection of gluinos, top squarks or winos might be possible at HL-LHC if we are lucky, but otherwise may have to await construction of higher energy pp colliders [29, 30].

Data Availability Statement

This manuscript has no associated data or the data will not be deposited. [Authors’ comment: This is a theory paper so there is no data.]

Notes

The validity of early measures of naturalness has been examined in Refs. [31,32,33] and has been found to be problematic. Recent examination of stringy naturalness based on general landscape considerations has been examined in Ref. [34] where it is shown that multi-TeV soft terms are more stringy natural than weak scale soft terms: see Fig. 9.

In accord with the PDG [50], we take \(f_A\equiv f_a/N_\mathrm{DW}\) where \(N_\mathrm{DW}\) is the domain-wall number which is \(N_\mathrm{DW}=6\) for the DFSZ axion model assumed here.

While flux compactifications may stabilize all complex structure moduli, the further step of Kähler moduli stabilization must be taken, and this could affect the distribution of soft SUSY breaking terms. Some discussion can be found for example in Ref. [81].

When the PQ field Y couples to the two Higgs doublets, the resulting model is hySPM model which is also an example of a gravity-safe model that solves strong CP problem and the SUSY \(\mu \) problem. This model gives \(f_a\) values similar to those obtained in the hyCCK model [73].

Indeed, our main conclusion at the end is that this scheme leads to overproduction of dark matter and likely to an unlivable universe so that the magnitude of the PQ scale is not likely to be determined by the landscape (in contradiction to the earlier hypotheses from Sect. 1.1). A better scheme is that the soft term \(-A_f\) will be correlated via the underlying SUGRA EFT to the other soft terms which are related to the generation of the weak scale. This approach leads to mixed axion–WIMP dark matter in the sweet spot with an abundance close to the measured value in our own pocket universe.

This value of \(T_R\) is in accord with well-motivated baryogenesis mechanisms such as non-thermal or Affleck-Dine leptogenesis [113].

Here, the saxion field strength \(s =\theta _s.f_{a}\).

In the Particle Data Book [50], it is tabulated that \(N_{eff}=3.13\pm 0.32\).

Anthropic arguments usually depend on a so-called “friendly” landscape wherein one focuses on most parameters assuming their SM values so as to retain predictivity [121]. Sometimes these are called fertile patches of the landscape of vacua since they should lead to the standard cosmological and particle physics models aside from just the few mass scales which may scan in the multiverse.

Such generational non-universality occurs in some string model variants. For example, in the mini-landscape of heterotic orbifold constructions, then third generation fields lie on the bulk of the compactified orbifold whilst first/second generation fields lie near orbifold fixed points [122]. These latter fields feel less protective supersymmetry and hence can have larger soft masses.

References

E. Witten, Nucl. Phys. B 188, 513 (1981)

R.K. Kaul, Phys. Lett. 109B, 19 (1982)

S. Weinberg, Rev. Mod. Phys. 61, 1 (1989)

R.D. Peccei, Adv. Ser. Direct. High Energy Phys. 3, 503 (1989)

S. Weinberg, Phys. Rev. D 11, 3583 (1975)

G. ’t Hooft, Phys. Rev. Lett. 37, 8 (1976)

S. Dimopoulos, H. Georgi, Nucl. Phys. B 193, 150 (1981)

S. Dimopoulos, H. Georgi, Phys. Lett. 117B, 287 (1982)

H. Baer, X. Tata, Weak Scale Supersymmetry: From Superfields to Scattering Events (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2006), p. 537

S. Dimopoulos, S. Raby, F. Wilczek, Phys. Rev. D 24, 1681 (1981)

U. Amaldi, W. de Boer, H. Furstenau, Phys. Lett. B 260, 447 (1991)

J.R. Ellis, S. Kelley, D.V. Nanopoulos, Phys. Lett. B 260, 131 (1991)

P. Langacker, M x Luo, Phys. Rev. D 44, 817 (1991)

L.E. Ibanez, G.G. Ross, Phys. Lett. B 110, 215 (1982)

K. Inoue et al., Prog. Theor. Phys. 68, 927 (1982)

K. Inoue et al., Prog. Theor. Phys. 71, 413 (1984)

H.P. Nilles, M. Srednicki, D. Wyler, Phys. Lett. B 120, 346 (1983)

J. Ellis, J. Hagelin, D. Nanopoulos, M. Tamvakis, Phys. Lett. B 125, 275 (1983)

L. Alvarez-Gaumé, J. Polchinski, M. Wise, Nucl. Phys. B 221, 495 (1983)

B.A. Ovrut, S. Raby, Phys. Lett. B 130, 277 (1983) (for a review, see L.E. Ibanez and G.G. Ross, Comptes Rendus Physique 8, 1013 (2007))

H.E. Haber, R. Hempfling, Phys. Rev. Lett. 66, 1815 (1991)

J.R. Ellis, G. Ridolfi, F. Zwirner, Phys. Lett. B 257, 83 (1991)

Y. Okada, M. Yamaguchi, T. Yanagida, Prog. Theor. Phys. 85, 1 (1991) (For a review, see e.g. M. Carena and H. E. Haber, Prog. Part. Nucl. Phys. 50, 63 (2003))

S. Heinemeyer, W. Hollik, D. Stockinger, A.M. Weber, G. Weiglein, JHEP 0608, 052 (2006)

J. Lykken, M. Spiropulu, Sci. Am. 310N5, 36 (2014)

H. Baer, V. Barger, P. Huang, A. Mustafayev, X. Tata, Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 161802 (2012)

H. Baer, V. Barger, P. Huang, D. Mickelson, A. Mustafayev, X. Tata, Phys. Rev. D 87, 115028 (2013)

H. Baer, V. Barger, M. Savoy, Phys. Rev. D 93(3), 035016 (2016)

H. Baer, V. Barger, J.S. Gainer, H. Serce, X. Tata, Phys. Rev. D 96(11), 115008 (2017)

H. Baer, V. Barger, J.S. Gainer, D. Sengupta, H. Serce, X. Tata, Phys. Rev. D 98(7), 075010 (2018)

H. Baer, V. Barger, D. Mickelson, Phys. Rev. D 88(9), 095013 (2013)

A. Mustafayev, X. Tata, Indian J. Phys. 88, 991 (2014)

H. Baer, V. Barger, D. Mickelson, M. Padeffke-Kirkland, Phys. Rev. D 89(11), 115019 (2014)

H. Baer, V. Barger, S. Salam, arXiv:1906.07741 [hep-ph]

H. Baer, V. Barger, P. Huang, D. Mickelson, A. Mustafayev, W. Sreethawong, X. Tata, JHEP 1312, 013 (2013)

H. Baer, V. Barger, M. Savoy, X. Tata, Phys. Rev. D 94(3), 035025 (2016)

H. Baer, V. Barger, P. Huang, JHEP 1111, 031 (2011)

Z. Han, G.D. Kribs, A. Martin, A. Menon, Phys. Rev. D 89(7), 075007 (2014)

H. Baer, A. Mustafayev, X. Tata, Phys. Rev. D 90(11), 115007 (2014)

C. Han, D. Kim, S. Munir, M. Park, JHEP 1504, 132 (2015)

A.M. Sirunyan et al. [CMS Collaboration], Phys. Lett. B 782, 440 (2018)

L. Susskind, In *Carr, Bernard (ed.): Universe or multiverse?* 247–266. arXiv:hep-th/0302219

R. Bousso, J. Polchinski, Sci. Am. 291, 60 (2004)

R. Bousso, J. Polchinski, JHEP 0006, 006 (2000)

S. Weinberg, Phys. Rev. Lett. 59, 2607 (1987)

M.R. Douglas, JHEP 0305, 046 (2003)

S. Ashok, M.R. Douglas, JHEP 0401, 060 (2004)

R.D. Peccei, H.R. Quinn, Phys. Rev. Lett. 38, 1440 (1977)

R.D. Peccei, H.R. Quinn, Phys. Rev. D 16, 1791 (1977)

M. Tanabashi et al. [Particle Data Group], Phys. Rev. D 98(3), 030001 (2018)

S. Weinberg, Phys. Rev. Lett. 40, 223 (1978)

F. Wilczek, Phys. Rev. Lett. 40, 279 (1978)

L.F. Abbott, P. Sikivie, Phys. Lett. B 120, 133 (1983)

J. Preskill, M.B. Wise, F. Wilczek, Phys. Lett. B 120, 127 (1983)

M. Dine, W. Fischler, Phys. Lett. B 120, 137 (1983)

M.S. Turner, Phys. Rev. D 33, 889 (1986)

K.J. Bae, J.H. Huh, J.E. Kim, JCAP 0809, 005 (2008)

L. Visinelli, P. Gondolo, Phys. Rev. D 80, 035024 (2009)

N. Du et al. [ADMX Collaboration], Phys. Rev. Lett. 120(15), 151301 (2018)

M. Kamionkowski, J. March-Russell, Phys. Lett. B 282 (1992) 137 (see also S. M. Barr and D. Seckel, Phys. Rev. D 46, 539 (1992))

R. Holman, S.D.H. Hsu, T.W. Kephart, E.W. Kolb, R. Watkins, L.M. Widrow, Phys. Lett. B 282, 132 (1992)

R. Kallosh, A.D. Linde, D.A. Linde, L. Susskind, Phys. Rev. D 52, 912 (1995)

B.A. Dobrescu, Phys. Rev. D 55, 5826 (1997)

A. Arvanitaki, S. Dimopoulos, S. Dubovsky, N. Kaloper, J. March-Russell, Phys. Rev. D 81, 123530 (2010)

J.P. Conlon, JHEP 0605, 078 (2006)

M. Cicoli, M. Goodsell, A. Ringwald, JHEP 1210, 146 (2012)

M. Cicoli, arXiv:1309.6988 [hep-th]

M. Cicoli, J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 485, 012064 (2014)

P. Svrcek, E. Witten, JHEP 0606, 051 (2006)

J.P. Conlon, S. Krippendorf, JHEP 1604, 085 (2016)

H.M. Lee, S. Raby, M. Ratz, G.G. Ross, R. Schieren, K. Schmidt-Hoberg, P.K.S. Vaudrevange, Phys. Lett. B 694, 491 (2011)

H.M. Lee, S. Raby, M. Ratz, G.G. Ross, R. Schieren, K. Schmidt-Hoberg, P.K. S. Vaudrevange, Nucl. Phys. B 850, 1 (2011) (see also K. S. Babu, I. Gogoladze and K. Wang, Nucl. Phys. B 660, 322 (2003))

H. Baer, V. Barger, D. Sengupta, Phys. Lett. B 790, 58 (2019)

K. Choi, E.J. Chun, J.E. Kim, Phys. Lett. B 403, 209 (1997)

S.P. Martin, Phys. Rev. D 54, 2340 (1996)

S.P. Martin, Phys. Rev. D 61, 035004 (2000)

S.P. Martin, Phys. Rev. D 62, 095008 (2000)

A.D. Linde, Phys. Lett. B 201, 437 (1988)

M.R. Douglas, arXiv:hep-th/0405279

M.R. Douglas, Comptes Rendus Physique 5, 965 (2004). [hep-th/0409207]

K. Bobkov, V. Braun, P. Kumar, S. Raby, JHEP 1012, 056 (2010)

V. Agrawal, S.M. Barr, J.F. Donoghue, D. Seckel, Phys. Rev. Lett. 80, 1822 (1998)

V. Agrawal, S.M. Barr, J.F. Donoghue, D. Seckel, Phys. Rev. D 57, 5480 (1998)

H. Baer, V. Barger, M. Savoy, H. Serce, Phys. Lett. B 758, 113 (2016)

H. Baer, V. Barger, H. Serce, K. Sinha, JHEP 1803, 002 (2018)

H. Baer, V. Barger, S. Salam, H. Serce, K. Sinha, JHEP 1904, 043 (2019)

S. Hellerman, J. Walcher, Phys. Rev. D 72, 123520 (2005)

F. Wilczek, In *Carr, Bernard (ed.): Universe or multiverse* 151–162. arXiv:hep-ph/0408167 (see also F. Wilczek, Class. Quant. Grav. 30, 193001 (2013))

M. Tegmark, A. Aguirre, M. Rees, F. Wilczek, Phys. Rev. D 73, 023505 (2006)

B. Freivogel, JCAP 1003, 021 (2010)

R. Bousso, L.J. Hall, Y. Nomura, Phys. Rev. D 80, 063510 (2009)

R. Bousso, B. Freivogel, S. Leichenauer, V. Rosenhaus, Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 101301 (2011)

R. Bousso, L. Hall, Phys. Rev. D 88, 063503 (2013)

F. D’Eramo, L.J. Hall, D. Pappadopulo, JHEP 1411, 108 (2014)

K. Harigaya, M. Ibe, K. Schmitz, T.T. Yanagida, Phys. Rev. D 88(7), 075022 (2013)

K. Harigaya, M. Ibe, K. Schmitz, T.T. Yanagida, Phys. Lett. B 749, 298 (2015)

K. Harigaya, M. Ibe, K. Schmitz, T.T. Yanagida, Phys. Rev. D 92(7), 075003 (2015)

A.H. Guth, J. Phys. A 40, 6811 (2007)

D. Matalliotakis, H.P. Nilles, Nucl. Phys. B 435, 115 (1995)

M. Olechowski, S. Pokorski, Phys. Lett. B 344, 201 (1995)

P. Nath, R.L. Arnowitt, Phys. Rev. D 56, 2820 (1997)

J. Ellis, K. Olive, Y. Santoso, Phys. Lett. B 539, 107 (2002)

J. Ellis, T. Falk, K. Olive, Y. Santoso, Nucl. Phys. B 652, 259 (2003)

H. Baer, A. Mustafayev, S. Profumo, A. Belyaev, X. Tata, JHEP 0507, 065 (2005)

F.E. Paige, S.D. Protopopescu, H. Baer, X. Tata, arXiv:hep-ph/0312045

K.J. Bae, H. Baer, H. Serce, Phys. Rev. D 91(1), 015003 (2015)

E.J. Chun, A. Lukas, Phys. Lett. B 357, 43 (1995)

J.E. Kim, M.S. Seo, Nucl. Phys. B 864, 296 (2012)

K.J. Bae, H. Baer, E.J. Chun, JCAP 1312, 028 (2013)

K.J. Bae, H. Baer, A. Lessa, H. Serce, JCAP 1410(10), 082 (2014)

H. Baer, A. Lessa, W. Sreethawong, JCAP 1201, 036 (2012)

H. Baer, C. Balazs, A. Belyaev, JHEP 0203, 042 (2002)

K.J. Bae, H. Baer, H. Serce, Y.F. Zhang, JCAP 1601, 012 (2016)

S.K. Soni, H.A. Weldon, Phys. Lett. 126B, 215 (1983)

M. Kawasaki, K. Kohri, T. Moroi, A. Yotsuyanagi, Phys. Rev. D 78, 065011 (2008)

K. Jedamzik, Phys. Rev. D 74, 103509 (2006)

K.J. Bae, K. Choi, S.H. Im, JHEP 1108, 065 (2011)

K.J. Bae, E.J. Chun, S.H. Im, JCAP 1203, 013 (2012)

A. Brandenburg, F.D. Steffen, JCAP 0408, 008 (2004)

J. Pradler, F.D. Steffen, Phys. Rev. D 75, 023509 (2007)

N. Arkani-Hamed, S. Dimopoulos, S. Kachru, arXiv:hep-th/0501082

H.P. Nilles, P.K.S. Vaudrevange, Mod. Phys. Lett. A 30(10), 1530008 (2015)

M.L. Ahnen et al., [MAGIC and Fermi-LAT Collaborations], JCAP 1602(02), 039 (2016)

K.J. Bae, H. Baer, H. Serce, JCAP 1706(06), 024 (2017)

K.J. Bae, H. Baer, V. Barger, D. Sengupta, arXiv:1902.10748 [hep-ph]

J.E. Kim, H.P. Nilles, Phys. Lett. B 138, 150 (1984)

H. Baer, V. Barger, H. Serce, Phys. Rev. D 94(11), 115019 (2016)

H.P. Nilles, Phys. Rep. 110, 1 (1984)

F. Denef, M.R. Douglas, JHEP 0405, 072 (2004)

L. Susskind, In *Shifman, M. (ed.) et al.: From fields to strings, vol. 3* 1745–1749. arXiv:hep-th/0405189

N. Arkani-Hamed, S. Dimopoulos, JHEP 0506, 073 (2005)

M. Dine, E. Gorbatov, S.D. Thomas, JHEP 0808, 098 (2008) (for reviews, see M. Dine, arXiv:hep-th/0410201)

L.J. Hall, Y. Nomura, JHEP 1201, 082 (2012)

Y. Nomura, S. Shirai, Phys. Rev. Lett. 113(11), 111801 (2014)

A. Arvanitaki, N. Craig, S. Dimopoulos, G. Villadoro, JHEP 1302, 126 (2013)

J.A. Casas, A. Lleyda, C. Munoz, Nucl. Phys. B 471, 3 (1996)

H. Baer, M. Brhlik, D. Castano, Phys. Rev. D 54, 6944 (1996)

G.F. Giudice, R. Rattazzi, Nucl. Phys. B 757, 19 (2006)

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by the US Department of Energy, Office of High Energy Physics. The computing for this project was performed at the OU Supercomputing Center for Education & Research (OSCER) at the University of Oklahoma (OU).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix: Statistics of the SUSY breaking scale

Appendix: Statistics of the SUSY breaking scale

In this Appendix, we review our computational approach to a statistical determination of soft SUSY breaking terms from string landscape considerations. The discussion follows along the lines of previous Refs. [84,85,86].

We first assume a vast ensemble of string vacua states which give rise to a \(D=4\), \(N=1\) supergravity effective field theory at high energies. Furthermore, the theory consists of a visible sector containing the MSSM along with a perhaps large assortment of fields that comprise the hidden sector. The scalar potential is given by the usual supergravity form [128]

where W is the holomorphic superpotential, K is the real Kähler potential and \(F_i=D_iW=DW/D\phi ^i\equiv \partial W/\partial \phi ^i+(1/m_P^2)(\partial K /\partial \phi ^i)W\) are the F-terms and \(D_\alpha \sim \sum \phi ^\dagger gt_{\alpha }\phi \) are the D-terms and the \(\phi ^i\) are chiral superfields. Supergravity is assumed to be broken spontaneously via the super-Higgs mechanism either via F-type breaking or D-type breaking or in general a combination of both leading to a gravitino mass \(m_{3/2}=e^{K/2m_P^2}|W|/m_P^2\). The (metastable) minima of the scalar potential can be found by requiring \(\partial V/\partial \phi ^i=0\) with \(\partial ^2V/\partial \phi ^i\partial \phi ^j>0\) to ensure a local minimum. The cosmological constant is given by

where \(m_{hidden}^4=\sum _i |F_i|^2 \, + \, \frac{1}{2}\sum _\alpha D^2_\alpha \) is a mass scale associated with the hidden sector (and usually in SUGRA-mediated models it is assumed \(m_{hidden}\sim 10^{12}\) GeV such that the gravitino gets a mass \(m_{3/2}\sim m_{hidden}^2/m_P\)).

According to Douglas et al. [79] from investigations of flux compactifications in IIB string theory, the distribution of vacua ought to have the form

where we define the weak scale \(m_{weak}\simeq m_{W,Z,h}\simeq 100\) GeV and where \(m_{hidden}\) sets the scale for SUSY breaking with \(m_{hidden}^2=\sum _i|F_i|^2+\frac{1}{2}\sum _{\alpha }D_{\alpha }^2\) for a (in general) more complicated SUSY breaking sector containing multiple sources of SUSY breaking, as may be expected to occur in string theory.

The function \(f_{SUSY}\) contains the expected statistical distribution of SUSY breaking scales. This is related to the mass scale of MSSM soft terms as \(m_{soft}\simeq m_{hidden}^2/m_P\). If the sources of SUSY breaking have uniformly distributed vacuum expectation values (vevs), then it is surmised that

where \(n_F\) is the number of F-breaking fields and \(n_D\) is the number of D-term breaking fields in the hidden sector [79, 80, 129, 130]. We will denote the collective exponent in \(f_{SUSY}\) as \(n\equiv 2n_F+n_D-1\). Since the F terms are complex-valued but the modulus |F| sets the scale of SUSY breaking, then they contribute as \((m_{hidden}^2)^{2n_F}\) whereas the real valued D terms contribute as \((m_{hidden}^2)^{n_D}\). In terms of MSSM soft SUSY breaking parameters, one would expect a statistically uniform distribution of soft terms \(m_{soft}^0\) only for a single D-term breaking field so that \(n_D=1\). A single F-term breaking field leads to \(f_{SUSY}\sim m_{soft}^1\) so that there is a linearly increasing preference for large soft terms. For more complex configurations with larger number of \(n_F\) and \(n_D\), then there is an even greater statistical preference for large soft terms which could lead to a preference for models with high scale SUSY breaking.

Regarding the role of the cosmological constant in determining the SUSY breaking scale, a key observation of Denef and Douglas [79, 129] and Susskind [130] was that W at the minima is distributed uniformly as a complex variable, and the distribution of \(e^{K/m_P^2}|W|^2/m_P^2\) is not correlated with the distributions of \(F_i\) and \(D_\alpha \). Setting the cosmological constant to nearly zero, then, has no effect on the distribution of supersymmetry breaking scales. Physically, this can be understood by the fact that the superpotential receives contributions from many sectors of the theory, supersymmetric as well as non-supersymmetric. The cosmological fine-tuning penalty is \(f_{cc}\sim \Lambda /m^4\) where the above discussion leads to \(m^4\sim m_{string}^4\) rather than \(m^4\sim m_{hidden}^4\), rendering this term inconsequential for determining the number of vacua with a given SUSY breaking scale.

The final term \(f_{EWFT}\) merits some discussion. Following Ref. [131], an initial guess [79, 130, 132,133,134,135] for \(f_{EWFT}\) was that \(f_{EWFT}\sim m_{weak}^2/m_{soft}^2\) which may be interpreted as conventional naturalness in that the larger the Little Hierarchy between \(m_{weak}\) and \(m_{soft}\), then the greater is the fine-tuning penalty. As pointed out in Ref. [85], there are several problems with this ansatz.

- 1.

As soft terms such as the trilinear \(A_t\) terms increase, one is ultimately forced into charge-or-color-breaking vacua of the MSSM [136, 137]. These sorts of vacua must be entirely vetoed on anthropic grounds.

- 2.

As high-scale soft terms such as \(m_{H_u}^2\) increase too much, then they are no longer driven to negative values and electroweak symmetry isn’t even broken. These non-EWSB solutions also should be vetoed on anthropic grounds.

- 3.

As the high scale soft term \(m_{H_u}^2\) increases, its weak scale value actually becomes smaller and smaller until EWSB is barely broken [84, 138]. This means that as the soft term \(m_{H_u}^2(\Lambda )\) increases, the weak scale value of \(m_{H_u}^2\) becomes more natural – a phenomena known as radiatively driven naturalness (RNS) [26, 27].

- 4.

As the soft term \(A_t\) increases, then cancellations can occur in the \(\Sigma _u^u(\tilde{t}_{1,2})\) contributions to the weak scale scalar potential, rendering their contributions closer to, not further from, the weak scale whilst at the same time lifting up the Higgs mass \(m_h\) to the 125 GeV range.

- 5.

Even in the event of appropriate EWSB, the factor \(f_{EWFT}\sim m_{weak}^2/m_{soft}^2\) penalizes but does not forbid vacua with a weak scale far larger than its measured value. In contrast, Agrawal et al. [82, 83] have shown that a weak scale larger than \(\sim 2\)–5 times its measured value would lead to much weaker weak interactions and a disruption in nuclear synthesis reactions, and likely an unlivable universe as we know it. In addition, Susskind posits that an increased weak scale would lead to larger SM particle masses and consequent disruptions in both atomic and nuclear physics. From these calculations, it seems reasonable to veto SM-like vacua which lead to a weak scale more than (conservatively) four times its measured value.

To account for these issues, in Ref. [85] the alternative of

was suggested where \(\Delta _\mathrm{EW}\) is the electroweak fine-tuning measure which just requires that weak scale contributions to \(m_Z^2\) should be comparable to or less than \(m_Z^2\). From the minimization conditions for the MSSM Higgs potential [9] one finds

The naturalness measure \(\Delta _\mathrm{EW}\) compares the largest contribution on the right-hand-side of Eq. (12) to the value of \(m_Z^2/2\). The radiative corrections \(\Sigma _u^u\) and \(\Sigma _d^d\) include contributions from various particles and sparticles with sizeable Yukawa and/or gauge couplings to the Higgs sector. Usually the most important of these are

where \(f_t\) is the top-quark Yukawa coupling, \(\Delta _t=(m_{\tilde{t}_L}^2-m_{\tilde{t}_R}^2)/2+M_Z^2\cos 2\beta (\frac{1}{4}-\frac{2}{3}x_W)\), \(x_W\equiv \sin ^2\theta _W\), \(F(m^2)= m^2\left( \log \frac{m^2}{Q^2}-1\right) \) and the optimized scale choice for evaluation of these corrections is \(Q^2=m_{\tilde{t}_1}m_{\tilde{t}_2}\). In the denominator of Eq. (13), the tree level expressions of \(m_{\tilde{t}_{1,2}}^2\) should be used. Expressions for the remaining \(\Sigma _u^u\) and \(\Sigma _d^d\) terms are given in the Appendix of Ref. [27].

In our approach, we assume a natural (\(|\mu |\sim m_{weak}\)) solution to the SUSY \(\mu \) problem, perhaps via the gravity-safe hyCCK model [73] based upon a \(\mathbb {Z}_{24}^R\) discrete R-symmetry. In this case, then \(m_Z\) is not fixed at its measured value, but is allowed to vary with values \(m_Z^{PU}\) in various pocket universes. The requirement of \(\Delta _{EW}<30\) then corresponds to a value \(m_Z^{PU}<4\cdot m_Z^{meas}\) in accord with Agrawal et al. calculations [82, 83].

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Funded by SCOAP3

About this article

Cite this article

Baer, H., Barger, V., Sengupta, D. et al. Is the magnitude of the Peccei–Quinn scale set by the landscape?. Eur. Phys. J. C 79, 897 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1140/epjc/s10052-019-7408-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1140/epjc/s10052-019-7408-x