Abstract

The lack of evidence for low-scale supersymmetry suggests that the scale of supersymmetry breaking may be higher than originally anticipated. However, there remain many motivations for supersymmetry including gauge coupling unification and a stable dark matter candidate. Models like pure gravity mediation (PGM) evade LHC searches while still providing a good dark matter candidate and gauge coupling unification. Here, we study the effects of PGM if the input boundary conditions for soft supersymmetry breaking masses are pushed beyond the unification scale and higher dimensional operators are included. The added running beyond the unification scale opens up the parameter space by relaxing the constraints on \(\tan \beta \). If higher dimensional operators involving the SU(5) adjoint Higgs are included, the mass of the heavy gauge bosons of SU(5) can be suppressed leading to proton decay, \(p\rightarrow \pi ^0 e^+\), that is within reach of future experiments. Higher dimensional operators involving the supersymmetry breaking field can generate additional contributions to the A- and B-terms of order \(m_{3/2}\). The threshold effects involving these A- and B-terms significantly impact the masses of the gauginos and can lead to a bino LSP. In some regions of parameter space the bino can be degenerate with the wino or gluino and give an acceptable dark matter relic density.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Despite its many motivations, low energy supersymmetry (SUSY) (\(E < 1\) TeV) is yet to be discovered at the LHC [1,2,3,4] calling into question the scale of supersymmetry breaking. While it is possible that the discovery of supersymmetry is just around the corner for the LHC, it is also quite possible that supersymmetry breaking lies at higher or even much higher energy scales. For example, in models of split supersymmetry [5,6,7,8,9], scalar masses may lie beyond the PeV scale. In minimal anomaly mediated supersymmetry breaking (mAMSB) [10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28], the gravitino is also of order a PeV, while scalar masses are set independently and may lie somewhere in between the TeV and PeV mass scales [29, 30]. Since gaugino masses are generated at the 1-loop level, their masses are of order 1 TeV. In pure gravity mediation (PGM) [31,32,33,34,35,36,37], a variant of split supersymmetry, scalar masses are set by the gravitino mass as in models of minimal supergravity [38] and are near the PeV scale, while gaugino masses are generated by anomaly mediation. In both mAMSB and PGM, the lightest supersymmetric particle (LSP) is often the wino.Footnote 1 The scale of supersymmetry breaking can be even higher as in high-scale supersymmetry [39,40,41]. It is in fact possible that the scale of supersymmetry breaking lies beyond the inflationary scale leaving behind only the gravitino with a mass of order 1 EeV [42,43,44,45]. In the most extreme case, supersymmetry breaking occurs at the string or Planck scale and does not play a role in low energy phenomenology.

Here, we take a more optimistic view. While some of the supersymmetric spectrum may be heavy, part of it may remain light and accessible to experiment. In conventional models of supersymmetry based on supergravity such as the constrained minimal supersymmetric standard model (CMSSM) [30, 46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59], the soft masses lie below about 10 TeV. In these models, some form of tuning of its input parameters is required to obtain the needed mass degeneracies which allow the relic density to fall into the range determined by CMB experiments [60]. In PGM models, the gauginos remain light. The dark matter candidate is the wino and the mass degeneracies that set the relic density are enforced by the SU(2) gauge symmetry.

In all of the models we have been referring to, there are strong relations among the supersymmetry breaking parameters at some very high energy scale. In the CMSSM, for example, there is a common universality scale (taken to be the grand unified theory (GUT) scale, \(M_\mathrm{GUT}\), often defined as the renormalization scale where the two electroweak gauge couplings are equal). At this scale, all soft scalar masses are equal to a common mass \(m_0\), the three gaugino masses are set to \(m_{1/2}\), supersymmetry breaking tri-linear terms are all set to \(A_0\). The \(\mu \)-term and the supersymmetry breaking bilinear, B are set at the weak scale by the minimization of the Higgs potential, leaving the ratio of the two Higgs expectation values, \(\tan \beta \) as a fourth free parameter. However, there is no firm reason that the universality scale for supersymmetry breaking must lie at the GUT scale. That scale may lie below the GUT scale as in subGUT models [56, 57, 59, 61,62,63,64] or above the GUT scale as in the superGUT models discussed here [58, 65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75]. Both subGUT and superGUT models necessarily introduce at least one additional parameter (over the CMSSM), namely the universality input scale, \(M_\mathrm{in}\). While superGUT models also introduce new parameters directly associated with the specific GUT, the additional running between \(M_\mathrm{in}\) and \(M_\mathrm{GUT}\) offers additional flexibility due to the non-universality of the supersymmetry breaking parameters at the GUT scale.

While the CMSSM is highly constrained with only 4 parameters, minimal supergravity (mSUGRA), mAMSB and PGM have even fewer free parameters. In mSUGRA models, the B-term is fixed at the GUT scale, by \(B_0 = A_0 - m_0\), and so \(\tan \beta \) must be determined by the Higgs minimization conditions together with the \(\mu \)-term [76, 77]. mAMSB models also have three free parameters which are often chosen to be \(m_0\), \(\tan \beta \) and the gravitino mass, \(m_{3/2}\), with the gaugino masses and A-terms determined from \(m_{3/2}\). In principle, PGM models have only one free parameter, \(m_{3/2}\). As in the case of mAMSB, gaugino masses and A-terms are determined from \(m_{3/2}\), \(m_0 = m_{3/2}\), \(B_0 = A_0 - m_0 \approx -m_0\), and as in mSUGRA models, \(\tan \beta \) and \(\mu \) are fixed at the weak scale [34]. However, in most cases, this one-parameter model is too restrictive and can be relaxed by adding a Giudice–Masiero term [71,72,73, 78,79,80] which allows one to choose \(\tan \beta \) as a second free parameter.

As is well known, one of the prime motivations for supersymmetry is grand unification. The problem of gauge coupling unification [81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88] and the gauge hierarchy [89,90,91] problems are both relaxed in supersymmetric models. However in the context of minimal supersymmetric SU(5) [92, 93], a new problem arises due to proton decay from dimension-5 operators [94, 95]. In [96], it was argued that low energy supersymmetric models were incompatible with minimal SU(5). These arguments have been relaxed, however, as the scale of supersymmetry breaking is pushed past the TeV scale [57, 97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104]. They are further relaxed in PGM and other models with high scale supersymmetry breaking [104].

Previously, we considered PGM models in the context of minimal SU(5) with supersymmetry breaking universality input at the GUT scale [104]. To relax the constraint on \(\tan \beta \) (which must be around 2 to achieve radiative electroweak symmetry breaking (rEWSB)), we introduced some non-universality in the Higgs soft masses. This allowed for higher \(\tan \beta \), a heavier Higgs mass (with better compatibility with experiment), and a proton lifetime within reach of on-going and future experiments. In the models considered, the gravitino mass was of order 100 TeV and as a result, the wino mass was too small to sustain the needed relic density of dark matter. Here, we consider a superGUT version of PGM models. The additional running between \(M_\mathrm{in}\) and \(M_\mathrm{GUT}\), which as noted earlier, generates some non-universalities among the soft masses at the GUT scale. In addition, we consider the effects of higher dimension operators which may further affect the gaugino mass spectrum. The effects of these operators may change the identity of the lightest gaugino from wino to bino and even a gluino. We find that both wino-bino co-annihilations [105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112] and bino-gluino co-annihilations [36, 110, 111, 113,114,115,116,117,118,119,120,121,122,123,124,125,126] may play an important role in determined the cold dark matter density in these models. These higher dimensional operators affect the masses of the SU(5) particles. In fact, these operators also allow for a lighter SU(5) gauge boson putting dimension-6 proton decay within reach of future experiments.

The paper is organized as follows. In the next section, we describe the minimal SU(5) model, the boundary conditions at the input scale, \(M_\mathrm{in}\) set by PGM, the higher dimension operators we consider, and the matching conditions at the GUT scale between SU(5) parameters and those associated with the Standard Model (SM). In Sect. 3, we discuss our calculation of the proton lifetime. In Sect. 4, we present results for superGUT PGM models. Our conclusions are given in Sect. 5.

2 Model

We restrict our attention to a minimal SU(5) superGUT model in the context of PGM [31,32,33,34,35,36,37]. Above the GUT scale, the field content is that of minimal SUSY SU(5) [92, 93], which is briefly reviewed in Sect. 2.1. In our model, the soft SUSY-breaking parameters are generated by PGM at a scale \(M_\mathrm{in} \ge M_\mathrm{GUT}\), as in the superGUT models discussed in Refs. [58, 65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75]. We discuss this framework in Sect. 2.2. Generically speaking, we expect the theory to contain higher-dimensional effective operators suppressed by the Planck scale. We consider the possible effects of such operators in Sect. 2.3. We then show the GUT-scale matching conditions in the presence of these effective operators in Sect. 2.4. Finally, in Sect. 2.5, we summarize the setup we analyze in the following sections.

2.1 Minimal SUSY SU(5) GUT

The minimal SUSY SU(5) GUT [92, 93] consists of three \(\mathbf {\overline{5}}\) (\({\Phi }_i\)) and \(\mathbf {10}\) (\({\Psi }_i\)) matter chiral superfields with \(i = 1,2,3\) the generation index, an adjoint GUT Higgs superfield \(\Sigma \equiv \sqrt{2}\Sigma ^A T^A\) with \(T^A\) (\(A=1, \dots , 24\)) the generators of SU(5), and a pair of the Higgs chiral superfields in \(\mathbf{5}\) and \(\overline{\mathbf{5}}\) representations, H and \(\overline{H}\), respectively. The three generations of the MSSM matter fields are embedded into \(\Phi _i\) and \(\Psi _i\) as in the original Georgi–Glashow model [127], while the MSSM Higgs chiral superfields \(H_u\) and \(H_d\) are in H and \(\overline{H}\) accompanied by the \(\mathbf{3}\) and \(\overline{\mathbf{3}}\) color Higgs superfields \(H_C\) and \(\overline{H}_C\), respectively. The renormalizable superpotential in this model is then given by

where the Greek sub- and super-scripts denote SU(5) indices, and \(\epsilon _{\alpha \beta \gamma \delta \zeta }\) is the totally antisymmetric tensor with \(\epsilon _{12345}=1\). R-parity is assumed to be conserved in this model.

The adjoint Higgs \(\Sigma \) is assumed to have a vacuum expectation value (VEV) of the form

with

This VEV breaks the SU(5) GUT group into the SM gauge group, \(\text {SU}(3)_C \otimes \text {SU(2)}_L \otimes \text {U}(1)_Y\), while giving masses to the GUT gauge bosons

with \(g_5\) the SU(5) gauge coupling constant. In addition, we impose the fine-tuning condition \(\mu _H -3\lambda V \lesssim \mathcal{O}(m_{3/2})\) to ensure the doublet-triplet mass splitting in H and \(\overline{H}\). The color and weak adjoint components of \(\Sigma \), the singlet component of \(\Sigma \), and the color-triplet Higgs states then acquire masses

respectively.

2.2 SuperGUT pure gravity mediation

In the minimal SUSY SU(5) GUT, the soft SUSY-breaking terms are given by

where \(\widetilde{\psi }_i\) and \(\widetilde{\phi }_i\) are the scalar components of \(\Psi _i\) and \(\Phi _i\), respectively, the \(\widetilde{\lambda }^A\) are the SU(5) gauginos, and for the scalar components of the Higgs superfields we use the same symbols as for the corresponding superfields. In this work, we assume that these soft SUSY-breaking terms in the visible sector are induced at a scale \(M_\mathrm{in} > M_\mathrm{GUT}\) through PGM [31,32,33,34,35]. We focus on the minimal PGM content for the moment, and discuss the case with the Planck-scale suppressed non-renormalizable operators in the subsequent subsection.

In minimal PGM, the Kähler potential is assumed to be flat, and hence the soft scalar masses are universal and equal to the gravitino mass \(m_{3/2}\), as in mSUGRA [38, 76, 77]:

On the other hand, the gaugino masses and A-terms vanish at tree level – such a situation is naturally obtained if there is no singlet SUSY breaking field and/or in models with strong moduli stabilization [71,72,73, 128,129,130,131]. In this case they are induced by anomaly mediation [10,11,12,13,14,15] at the quantum level, and are thus suppressed by a loop factor. The contribution of the one-loop suppressed A-terms to the physical observables is insignificant and thus we can safely neglect them in the following discussion:

For gaugino masses, on the other hand, AMSB generates

with \(b_5 = -3\) the beta-function coefficient of the SU(5) gauge coupling. Thus, the gauginos have a universal mass above the GUT scale, which is orders-of-magnitude smaller than the scalar masses.

In addition to these contributions, in PGM, Giudice–Masiero (GM) terms [34, 35, 71,72,73,74, 78,79,80] are added to the Kähler potential:

These terms shift the corresponding \(\mu \)-terms as

and generate B-terms

where the first terms correspond to the usual supergravity contribution. We note that the second terms on the right-hand side of the above equations are smaller than the first terms by \(\mathcal{O}(m_{3/2}/M_\mathrm{GUT})\). For the contribution to the \(\mu \)-terms (11), therefore, we can safely neglect this in the following discussion. As for the B-terms (12), on the other hand, these terms do play a role in assuring successful electroweak symmetry breaking, as we will see in Sect. 2.4.

2.3 Planck-scale suppressed higher-dimensional operators

GUT phenomenology has some sensitivity to the Planck-scale suppressed higher-dimensional operators since the GUT scale is only about two orders of magnitude lower than the Planck scale. The SUSY spectrum may also be affected by non-renormalizable operators that consist of both visible and SUSY-breaking sector fields. In this subsection, we discuss the effect of such operators.

2.3.1 Non-renormalizable operators without SUSY-breaking fields

We first discuss the effect of the Planck-scale suppressed higher-dimensional operators which do not include SUSY-breaking fields. Here, we mainly consider the dimension-five operators involving the adjoint Higgs field \(\Sigma \), as the effect of such operators is suppressed only by a factor of \(\mathcal{O}(V/M_P)\).

Among such operators,

has the most significant effect on our analysis, where \(\mathcal{W}\equiv T^A \mathcal{W}^A\) denotes the superfields corresponding to the field strengths of the SU(5) gauge vector bosons \(\mathcal{V} \equiv \mathcal{V}^A T^A\) and \(M_P\) is the reduced Planck mass. This effective operator affects both gauge coupling [132,133,134,135,136,137] and gaugino mass [132, 137, 138] unification, as we see in detail in Sect. 2.4.

Another class of dimension-five operators that affect gauge coupling unification is comprised of quartic superpotential terms of the adjoint Higgs fields [139]:

These operators can split the masses of the SU(3)\(_C\) and SU(2)\(_L\) adjoint components in \(\Sigma \), \(M_{\Sigma _8}\) and \(M_{\Sigma _3}\), by \(\mathcal{O}(V^2/M_P)\). This mass difference induces threshold corrections to gauge coupling constants of \(\sim \ln (M_{\Sigma _3}/M_{\Sigma _8})/(16\pi ^2)\).Footnote 2 This effect can be significant if \(|\lambda ^\prime | \lesssim |c_{4\Sigma , 1(2)}|V/M_P\). In the following analysis, however, for simplicity, we assume that the contribution of these operators is negligibly small.

The operators

are also of dimension-five. These operators shift the masses of the SU(3)\(_C\) triplet and SU(2)\(_L\) doublet components of H and \(\overline{H}\) by \(\sim V^2/M_P\). In order to produce a MSSM Higgsino mass term of order the SUSY-breaking scale, we need to cancel this contribution by fine-tuning the parameter \(\mu _H\). Note that this does not introduce an additional fine tuning as, \(\mu _H\) must be tuned in any case to cancel \(3\lambda V\) as noted earlier. Other than this, these operators provide no significant effect on our analysis.

The adjoint Higgs field may directly couple to the matter fields via non-renormalizable operators such as

After \(\Sigma \) develops a VEV, these operators lead to Yukawa interactions. Among these operators, the first one has a significant implication for the prediction of the model, since it modifies the unification of the down-type quark and charged-lepton Yukawa couplings, which should be exact at the GUT scale in minimal SU(5). On the other hand, it is known that in most of the parameter space in the MSSM, Yukawa unification is imperfect. For the third generation, the deviation is typically at the \(\mathcal{O}(10)\)% level, while for the first two generations, there are \(\mathcal{O}(1)\) differences. These less successful predictions can be explained if the first term in Eq. (16) is included [139,140,141]. The change in the Yukawa couplings due to this operator is \(\mathcal{O}(V/M_P) \sim 10^{-2}\). Therefore, if the value of the third generation Yukawa coupling at the GUT scale is \(\sim 10^{-1}\), this contribution gives rise to an \(\mathcal{O}(10)\)% correction. For the first and second generation Yukawa couplings, this correction can be as large as the values of the Yukawa couplings themselves since their values are (much) smaller than \(10^{-2}\). As we do not discuss Yukawa coupling unification in this paper, we do not consider the operators in Eq. (16) in what follows.

We may also have Kähler-type operators of the form

where F collectively stands for the fields in this model, \(F = \Psi , \Phi , H, \overline{H}, \Sigma \). These terms modify the wave functions of the components in the field F below the GUT scale. This correction is insignificant for our analysis, and thus we neglect them in the following discussions.

There are lepton-number violating operators of the form

These dimension-five operators give rise to Majorana masses for left-handed neutrinos at low energies, whose size is at most \(\mathcal{O} (10^{-5})\) eV. This is much smaller than \(\sqrt{m_{31}^2}\) and \(\sqrt{m_{21}^2}\) (\(m_{31}^2\) and \(m_{21}^2\) are the squared-mass differences of active neutrinos) observed in neutrino oscillation experiments, and therefore we need an extra source for neutrino mass generation. This can be provided by right-handed neutrinos, which are singlets under SU(5), as was considered for the superGUT CMSSM in [75]. The presence of these additional singlet fields, as well as the operators in Eq. (18), does not affect the discussion below.

Finally, we may write down the dimension-five baryon- and lepton-number violating operator,

This operator yields the interactions of the form QQQL and \(\bar{U} \bar{D} \bar{U} \bar{E}\), which induce proton decay such as \(p \rightarrow K^+ \bar{\nu }\). If the coefficient of the operator (19) is \(\mathcal{O}(1)\), the presence of such an operator could be disastrous; as shown in Ref. [142], in this case the proton lifetime is predicted to be much shorter than the experimental bound even when the SUSY-breaking scale is as high as \(\sim 1\) PeV. This conclusion, however, strongly depends on the flavor structure of the coefficient  . For example, we may expect there is a flavor symmetry at high energies that accounts for small Yukawa couplings, as in the Froggatt-Nielsen model [143]. In this case, the couplings

. For example, we may expect there is a flavor symmetry at high energies that accounts for small Yukawa couplings, as in the Froggatt-Nielsen model [143]. In this case, the couplings  are strongly suppressed for the first two generations, and the resultant proton decay rate can be small enough to evade the experimental bound. In this work, we assume that the coefficients of the operator (19) are sufficiently suppressed so that the proton decay rate induced by this operator is negligibly small.

are strongly suppressed for the first two generations, and the resultant proton decay rate can be small enough to evade the experimental bound. In this work, we assume that the coefficients of the operator (19) are sufficiently suppressed so that the proton decay rate induced by this operator is negligibly small.

2.3.2 Non-renormalizable operators with SUSY-breaking fields

Next, we discuss non-renormalizable interactions that directly couple the visible-sector fields to hidden-sector fields. The presence of such interactions can modify the SUSY spectrum predicted in PGM. As we have seen in Sect. 2.2, in PGM, gaugino masses are induced by quantum effects and thus suppressed by a loop factor compared with the gravitino mass \(m_{3/2}\), which is the order parameter of SUSY breaking. Thus, gaugino masses are more sensitive to the effects of higher dimensional operators than scalar masses. Indeed, in Sect. 2.4 we will see that if such higher-dimensional operators generate A- and/or B-terms in the Higgs sector, they can significantly modify the gaugino mass spectrum through threshold corrections. To see this effect, we focus on the Planck-scale suppressed operators that contain both the Higgs \((\Sigma , H, \overline{H})\) and hidden-sector fields.

Again, we focus on the dimension-five effective operators. For the Kähler-type interactions, we have

where Z stands for the SUSY-breaking field in the hidden sector. As for the superpotential operators, in principle, renormalizable interactions such as \(Z\mathrm{Tr}(\Sigma ^2)\) and \(ZH\overline{H}\) are allowed, but here we just assume that the Higgs fields are sequestered from the SUSY-breaking field so that there is no coupling at the renormalizable level. In this case, the dominant contribution comes from the dimension-five operators:

Once the SUSY-breaking field Z develops an F-term, \(F_Z\), the fourth and fifth terms in Eq. (20) shift the \(\mu \)-terms as

where we have used

As was the case for the GM terms, these corrections are smaller than the tree-level terms by a factor of \(\mathcal{O}(m_{3/2}/M_\mathrm{GUT})\), and thus can safely be neglected. The above operators also yield soft SUSY-breaking terms. A straightforward calculation leads to

Notice that the last two terms in Eq. (21) do not generate soft SUSY-breaking terms.Footnote 3 Hence, we can neglect these operators in what follows. We also note that if \(\kappa _H, \kappa _{\bar{H}} \ne 0\), A-terms for matter fields are generated even though there is no direct coupling between the matter fields and the SUSY-breaking field. Since A-terms are induced only via quantum corrections in minimal PGM, the corrections in Eq. (24) can be the dominant contribution in this formulation.

When we write down the operators in Eqs. (20) and (21), we have assumed that the field Z is a singlet field. In this case, Z can in principle appear in the gauge kinetic function to generate a gaugino mass at tree level, which may dominate the AMSB contribution (9). In the present work, we instead assume that the Lagrangian is (approximately) invariant under the shift symmetry:Footnote 4

with \(\zeta \) real. This can be realized if

and \(\kappa _\Sigma \), \(\kappa _H\), and \(\kappa _{\bar{H}}\) are real. In this case, Z cannot couple to the gauge kinetic function and thus the dominant contribution to the gaugino mass term is given by AMSB as in Eq. (9). All of the superpotential terms (21) are forbidden by the shift symmetry, i.e., \(\Delta W_\mathrm{eff}^Z = 0\), while the Kähler potential in Eq. (20) reduces to

We focus on this case unless otherwise noted.

2.4 GUT-scale matching conditions

In this subsection, we summarize the matching conditions at the unification scale \(M_\mathrm{GUT}\), where the SU(5) GUT parameters are matched onto the MSSM parameters.

Let us begin with the matching conditions for the gauge coupling constants. At one-loop level in the \(\overline{\mathrm{DR}}\) renormalization scheme [146], we have

where \(g_1\), \(g_2\), and \(g_3\) are the U(1)\(_Y\), SU(2)\(_L\), and SU(3)\(_C\) gauge couplings, respectively, and \(Q \simeq M_\mathrm{GUT}\) is a renormalization scale. The last terms are induced by the dimension-five operator in Eq. (13). From these equations, we find

Notice that the contribution of the operator (13) to the right-hand side in Eq. (32) vanishes; we can therefore unambiguously determine the combination \(M_X^2 M_\Sigma \) via (32) by running the gauge couplings up from their low-energy values [147,148,149]. On the other hand, the operator (13) does affect the determination of \(M_{H_C}\) through Eq. (31). Indeed, we can use this degree of freedom to regard \(M_{H_C}\) (or, \(\lambda \) and \(\lambda ^\prime \)) as a free parameter, as was done in Refs. [58, 74].

For the Yukawa couplings, we use the tree-level matching conditions. As we mentioned in Sect. 2.3.1, the higher-dimensional operators in (16) affect the matching conditions, introducing a theoretical uncertainty. Without any rationale for evaluating the size of this effect, in this paper, we simply use

for the third generation Yukawa couplings, where \(h_{\mathbf{10}, i}\), \(h_{\overline{\mathbf{5}}, i}\), \(f_{u_i}\), \(f_{d_i}\), and \(f_{e_i}\) are eigenvalues of \(h_\mathbf{10}\), \(h_{\overline{\mathbf{5}}}\), the up-type Yukawa couplings, the down-type Yukawa couplings, and the charged lepton Yukawa couplings, respectively. This condition is the same as that used in Ref. [68,69,70]. For the first and second generation Yukawa couplings, on the other hand, we use

as in Ref. [58], though the replacement of \(f_{d_i}\) by \(f_{e_i}\) or \((f_{d_i}+f_{e_i})/2\) barely changes our result since these values are very small.

Next we list the matching conditions for the soft SUSY-breaking terms. For the gaugino masses [137, 150], we have:Footnote 5

It is instructive to investigate these equations for the case of PGM without the higher-dimensional operators (\(c = \kappa _\Sigma = \kappa _H = \kappa _{\bar{H}} = 0\)). By substituting Eqs. (8), (9), and (12) into the above equations (with \(c_\Sigma = c_H = 0\)), at the leading order, we obtain

which reproduces the gaugino mass spectrum in the MSSM with AMSB [10,11,12,13,14,15]. This demonstrates the well known feature of AMSB, namely, that the contribution of heavy fields completely decouples at their mass threshold so that the AMSB mass spectrum is unambiguously determined in low-energy effective theories. However, if there exist extra sources for soft masses of \(\mathcal{O}(m_{3/2})\), such as those mediated by the Planck-scale suppressed operators discussed in Sect. 2.3.2, the gaugino masses can be modified by an \(\mathcal{O}(1)\) factor and thus the resultant gaugino mass spectrum can be changed significantly.

The soft masses of the MSSM matter fields, as well as the A-terms of the third generation sfermions, are obtained via the tree-level matching conditions:

The \(\mu \) and B-term matching conditions require fine-tuning such that the low-energy values of these parameters are \(\mathcal{O}(m_{3/2})\). The matching conditions are [151]

with

As one can see, in order for the left-hand sides of Eqs. (41) and (42) to be \(\mathcal{O}(m_{3/2})\), \(|\mu _H -3\lambda V|\) and \(|\Delta |\) should be \(\lesssim \mathcal{O}(m_{3/2})\) and \(\mathcal{O}(m_{3/2}^2/M_\mathrm{GUT})\), respectively. We accept this fine-tuning in this model.

Note that the condition \(\Delta = 0\) is invariant under the renormalization-group flow [152]. Therefore, we can discuss the implications of this condition for the input soft SUSY-breaking parameters without suffering from the uncertainty due to renormalization effects. By substituting Eqs. (12) and (24) into \(\Delta \), we obtain its value at the input scale:Footnote 6

This result indicates that we need an \(\mathcal{O}(m_{3/2}/M_\mathrm{GUT})\) fine-tuning in \(\omega _{\lambda } - \omega _{\lambda ^\prime }\) if they are both of \(\mathcal{O}(1)\). This fine-tuning can, however, be evaded if we consider a setup as in Sect. 2.3.2, where \(\omega _{\lambda } = \omega _{\lambda ^\prime } = 0\) is assured. On the other hand, the second term is of \(\mathcal{O}(m_{3/2}^2/M_\mathrm{GUT})\), and thus even if this term is present the low-energy B-parameter remains \(\mathcal{O}(m_{3/2})\), shifted by

We will exploit this shift to realize electroweak symmetry breaking and the matching condition in Eq. (42).

The \(\mu \) and B parameters at low energies are subject to the electroweak vacuum conditions,

where \(\Delta _B\) and \(\Delta _\mu ^{(1,2)}\) denote loop corrections [153]. The GUT-scale values of these parameters are obtained using renormalization group equations from these values with some iterations. To satisfy the condition (42) with the B-parameters in minimal SU(5) at the unification scale, and which are obtained from given input values via renormalization group equations, we utilize the Giudice–Masiero contribution to the B-parameter shown in Eq. (45), as in Ref. [74]. With the extra free parameters, \(c_\Sigma \) and \(c_H\), we can always satisfy the matching condition (42).

2.5 Summary

In summary, we consider the minimal SU(5) GUT with PGM where the input scale \(M_\mathrm{in}\) for soft SUSY-breaking parameters is taken to be higher than the unification scale \(M_\mathrm{GUT}\). We also introduce GM terms (10), the Planck-scale suppressed correction to the gauge kinetic term (13), and the Kähler-type non-renormalizable interactions (27), neglecting the other dimension-five operators. The soft mass parameters at the input scale \(M_\mathrm{in}\) are then given by

The \(\mu \) and B parameters at the electroweak scale are determined for a given \(\tan \beta \) and \(\text {sign}(\mu )\) according to Eqs. (46) and (47); the values of these parameters at the unification scale are set by Eqs. (41) and (42), by fine-tuning \(\mu _H\) and a linear combination of \(c_H\) and \(c_\Sigma \). Our minimal superGUT PGM model is therefore specified with the following set of input parameters:

where \(\lambda \) and \(\lambda ^\prime \) are given at the unification scale while \(\kappa _\Sigma , \kappa _H, \kappa _{\bar{H}}\) are specified at the input scale \(M_\mathrm{in}\). The coefficient of the operator (13), c, as well as the unified coupling, \(g_5\), and the adjoint Higgs VEV, V, are determined using Eqs. (31–33) as was done in Refs. [58, 74]. In the following analysis, however, we also consider the case where \(c = 0\); in this case, \(\lambda ^\prime \) becomes a dependent parameter and is determined by the conditions (31–33). Our calculations require that we choose a value of Q to evaluate the gauge couplings and implement the matching conditions. We have chosen \(\log _{10} (Q/\mathrm{1~GeV}) = 16.3\) throughout this work, and our results are relatively insensitive to this choice (so long as it is near \(10^{16}\) GeV).

3 Proton decay

In the minimal SUSY GUT, the baryon- and lepton-number violating dimension-five operators are generated by the exchange of the color-triplet Higgs fields \(H_C\) and \(\overline{H}_C\). Such operators are potentially quite dangerous due to their low dimensionality, since they may induce rapid proton decay. In fact, it was argued in Ref. [96] based on the calculation of Ref. [154] that if stops lie around the TeV scale, the proton decay lifetime induced by the color-triplet Higgs exchange is too short to evade the experimental limit. This problem is, however, evaded if the SUSY scale is much higher than the TeV scale [57, 97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104], as in PGM models. Indeed, it is shown in Ref. [104] that in minimal SU(5) with PGM, the lifetime of the \(p \rightarrow K^+ \bar{\nu }\) mode is much longer than the current experimental bound for \(m_{3/2} \gtrsim 100\) TeV. It is found that this is also true for the present model and thus we can safely neglect dimension-five proton decay.

When dimension-five proton decay is suppressed, dimension-six proton decay induced by the exchange of GUT gauge bosons becomes dominant. The primary decay channel is \(p \rightarrow \pi ^0 e^+\) and its rate goes as \(\propto M_X^{-4}\). Intriguingly, in the models considered, \(M_X\) can be predicted to be lower than the typical GUT scale for TeV-scale SUSY models, \(\simeq 2 \times 10^{16}\) GeV, which then results in a shorter proton decay lifetime. As discussed in Ref. [149], the combination \((M_X^2 M_\Sigma )^{1/3}\), scales as \((M_3 M_2)^{-1/9}\). Hence, \(M_X\) tends to decrease when \(m_{3/2}\) is large.Footnote 7 In addition, as we discuss below, since \(M_\Sigma \sim \lambda ' V\) a small value for \(M_X\) can also be obtained when \(\lambda ^\prime \) is \(\mathcal{O}(1)\). Motivated by these observations, we study the lifetime of the \(p \rightarrow \pi ^0 e^+\) decay channel predicted in our model in this paper. We review the calculation of the dimension-six proton decay in this section, and show our numerical results in the subsequent section.

As we mentioned above, dimension-six proton decay is induced by SU(5) gauge interactions. The relevant Lagrangian terms are

where X stands for the SU(5) massive gauge fields, \(V_\mathrm{CKM}\) denotes the Cabibbo–Kobayashi–Maskawa (CKM) matrix, \(\varphi _i\) are the GUT phase factors [155], and we have suppressed the SU(3)\(_C\) and SU(2)\(_L\) indices just for simplicity (see, e.g., Ref. [156] for a more explicit expression). We integrate out the X bosons at tree level to obtain the dimension-six effective operators, and evolve their Wilson coefficients from the unification scale to the hadronic scale according to renormalization group equations in each effective theory. By using these effective operators, we can then calculate the partial decay width of the \(p \rightarrow \pi ^0 e^+\) mode. The result is

where \(m_p\) and \(m_\pi \) denote the proton and pion masses, respectively. The amplitudes \(\mathcal{A}_{L/R}\) are given by

where \(V_{ud} \equiv (V_\mathrm{CKM})_{12}\) and \(\langle \pi ^0\vert (ud)_Ru_L\vert p\rangle \) is the hadron matrix element, for which we use the result obtained by a lattice QCD simulation [157]:

\(A_1\) and \(A_2\) are the renormalization factors for the effective operators. They are given by

where \(M_\mathrm{SUSY}\) indicates the SUSY-breaking scale, and \(A_L \simeq 1.247\) is the QCD renormalization factor that is computed using the two-loop renormalization group equation [158]. The other renormalization factors are obtained at the one-loop level by using the renormalization group equations given in Refs. [159, 160].Footnote 8

Note that in contrast to dimension-five decay modes, the partial decay width \(\Gamma (p \rightarrow \pi ^0 e^+)\) does not depend on the GUT phases \(\varphi _i\) (see, e.g., Ref. [58]). In addition, \(g_5\) and \(M_X\), which appear in the amplitudes, can also be evaluated by using the threshold corrections (31–33) as we discussed in the previous section. For these reasons, the evaluation of the dimension-six proton decay rate is rather robust and suffers less from unknown uncertainties.Footnote 9

4 Results

We now show our numerical results for the study of the superGUT PGM model. In Sect. 4.1, we first discuss the case without any of the higher-dimensional operators. Then, in Sect. 4.2, we consider models which include the operator (13) (\(c \ne 0\)) but without the Kähler-type operators (27). Finally, in Sect. 4.3, we analyze the model with all of the higher-dimensional operators we consider in this paper.

4.1 Models without higher-dimensional operators

We begin with the case with \(c = \kappa _\Sigma = \kappa _{H} = \kappa _{\bar{H}} = 0\). As we mentioned in Sect. 2.5, in this case, \(\lambda ^\prime \) is not an independent parameter, but rather is fixed by the matching conditions (31–33). Therefore, each parameter point is specified by \(m_{3/2}\), \(M_\mathrm{in}\), \(\lambda \), \(\tan \beta \), and \(\text {sign}(\mu )\).

To maximize the effect of the renormalization group evolution above \(M_\mathrm{GUT}\), we set \(M_\mathrm{in} = 10^{18}\) GeV and choose \(\mu < 0\) so as to maximize the wino mass for the low values of \(\tan \beta \) we are considering.Footnote 10 In Fig. 1a, we plot the predicted value of the SM-like Higgs mass \(m_h\) as a function of the coupling \(\lambda \) for several values of \(\tan \beta \). In order to obtain rEWSB, PGM models are generally restricted to low values of \(\tan \beta \) [34]. In addition, unless \(\tan \beta \) is near its lower limit of \(\sim 2\), the value of \(\lambda \) must be relatively large (of order 1). In the Figure, for the three larger values of \(\tan \beta \), there is a lower limit to \(\lambda \) which allows rEWSB. Very high values of \(\lambda \) are also excluded as eventually the running value of \(\lambda \) becomes non-perturbative as it runs from \(M_\mathrm{GUT}\) to \(M_\mathrm{in}\). This effect cuts off the curves as \(\lambda (M_\mathrm{GUT})\) approaches 1. As we see, \(m_h \simeq 125\) GeV is best obtained for \(\tan \beta \approx 2.4\). Given that the Higgs-mass calculation suffers from the uncertainty of a few GeV,Footnote 11 we conclude that the observed value of \(m_h\) can be reproduced for \(\tan \beta \simeq 2\)–3. A similar pattern is seen in Fig. 1c which shows the Higgs mass for fixed \(\tan \beta = 2.4\) for several values of \(m_{3/2}\) between 250–1000 TeV.

a, c The Higgs mass \(m_h\) and b, d the LSP density \(\Omega _\mathrm{LSP} h^2\) as functions of the coupling \(\lambda \) with \(m_{3/2} = 10^3\) TeV for several values of \(\tan \beta \) a, b or fixed \(\tan \beta = 2.4\) for several values of \(m_{3/2}\) (c, d). We set \(M_\mathrm{in} = 10^{18}\) GeV, and \(\mu < 0\)

Since we do not include the higher-dimensional operators here, the gaugino masses are given by the AMSB spectrum (plus loop corrections), and thus the LSP is wino-like. It is known that the thermal relic abundance of the wino-like LSP agrees with the observed dark matter density \(\Omega _\mathrm{DM} h^2 \simeq 0.12\) [60] if its mass is \(\simeq 3\) TeV [165]. From Eq. (39), we find that a 3-TeV wino mass can be obtained for \(m_{3/2} \simeq 10^3\) TeV, and thus we expect that the correct DM density can be reproduced with this gravitino mass. In Fig. 1b, we show the thermal relic abundance of the LSP as a function of \(\lambda \) with the same choice of parameters used in Fig. 1a. It is in fact found that \(\Omega _\mathrm{LSP} h^2\simeq 0.12\) can be obtained, again for an \(\lambda \sim \mathcal{O}(1)\) and a small value of \(\tan \beta \). While lowering \(m_{3/2}\) to 500 TeV would still allow for a Higgs mass of 125 GeV (albeit with a slightly lower value of \(\lambda \)), the relic density would drop to \(\Omega _\mathrm{LSP} h^2 < 0.05\) due to the decrease in the wino mass. We clearly see the dependence of \(\Omega _\mathrm{LSP} h^2\) on \(m_{3/2}\) in Fig. 1d where \(\tan \beta = 2.4\).

In Fig. 2, we show two examples of \(\lambda \)-\(m_{3/2}\) plane for \(\tan \beta = 2.4\) (upper panel), and \(\tan \beta = 3\) (lower panel) and in both cases \(M_\mathrm{in} = 10^{18}\) GeV, and \(\mu < 0\). The solid red and dotted black curves show the Higgs mass \(m_h\) and \(\lambda ^\prime \), respectively. Recall that with \(c=0\), \(\lambda '\) is not a free parameter and is determined by the matching conditions. As one can see, when \(\tan \beta = 2.4\) over much of the plane, \(\lambda '\) takes values between \(10^{-4}\) and \(10^{-3}\) with slightly more variation when \(\tan \beta = 3\). The blue shaded region corresponds to the areas where the LSP abundance agrees with the observed DM density, \(\Omega _\mathrm{DM} h^2 \simeq 0.1200 \pm 0.0036\) (3\(\sigma \)) [60]. In the magenta region, rEWSB can not be obtained, while in the brown region \(\lambda \) becomes non-perturbative at the input scale (recall that the value used in the figure is \(\lambda (M_\mathrm{GUT})\)). This figure shows that we can obtain the correct value of the SM-like Higgs boson mass and the DM abundance simultaneously for \(m_{3/2} \sim 1\) PeV and \(\lambda = \mathcal{O}(1)\), which remains perturbative up to the input scale when \(\tan \beta \approx 2.4\). As one can see, in the lower panel when \(\tan \beta = 3\) the Higgs mass increases significantly. However, some of the dark matter strip may be viable considering the uncertainty in the Higgs mass calculation. In addition, in this case, the allowed range in \(\lambda \) is limited by the requirement of rEWSB.

Examples of the \(\lambda \)-\(m_{3/2}\) plane for \(M_\mathrm{in} = 10^{18}\) GeV, and \(\mu < 0\). In the upper panel, \(\tan \beta = 2.4\) and in the lower panel, \(\tan \beta = 3\), The solid red and dotted black curves show the Higgs mass \(m_h\) and \(\lambda ^\prime \), respectively. The blue shaded region corresponds to the areas where the LSP abundance agrees with the observed dark matter density. In the magenta region, rEWSB can not be obtained, while in the brown region \(\lambda \) becomes non-perturbative at the input scale

The relatively large region of parameter space with \(m_h \sim 125\) GeV and \(\Omega _\mathrm{LSP} h^2 \sim 0.12\) is achieved with a high supersymmetry breaking input scale, \(M_\mathrm{in} = 10^{18}\) GeV. Much of this space disappears as \(M_\mathrm{in}\) approaches the GUT scale. For example, when \(M_\mathrm{in}\) is lowered to \(10^{16.5}\) GeV. the relic density strip remains near \(m_{3/2} \sim 1\) PeV since that is required to obtain a wino with mass \(\sim 3\) TeV. However, the Higgs mass contours are pushed to lower values of \(m_{3/2}\) and more importantly the region with viable rEWSB is also pushed to lower \(m_{3/2}\) so that obtaining the correct Higgs mass and relic density is no longer possible.

Because \(\lambda '\) turns out to be small in this class of models with \(c=0\), \(M_X\) tends to be quite large. Note that by using Eqs. (4) and (5) we can express the mass of the SU(5) gauge bosons as

The factor \(\left( M_X^2 M_\Sigma \right) ^{\frac{1}{3}}\) can be evaluated by using Eq. (32), which is found to have a very small dependence on the choice of parameters (see, e.g., Ref. [104]). As a result, when \(\lambda ^\prime \) is very small, the proton decay lifetime becomes very long. We find that over the parameter space considered in the above figures the predicted value of the lifetime of the \(p \rightarrow \pi ^0 e^+\) decay channel is well above the current experimental bound, \(\tau (p \rightarrow \pi ^0 e^+) > 1.6\times 10^{34}\) years [166].

In summary, we find that despite the limited number of degrees of freedom, there is a parameter set with which both the Higgs mass and the dark matter relic abundance can be explained and the predicted value of proton lifetime is consistent with the experimental bound. The LSP is a wino-like neutralino as in AMSB models. In the following subsections, we consider the cases with the Planck-scale suppressed non-renormalizable operators and discuss their phenomenological consequences.

4.2 Models with Superpotential non-renormalizable interactions

Next, we discuss the case with \(c \ne 0\), keeping \(\kappa _\Sigma = \kappa _H = \kappa _{\bar{H}} = 0\). In this case, we can regard \(\lambda ^\prime \) as a free parameter, with c determined through the matching conditions (31–33). A non-zero value of c has two important phenomenological consequences. First, since \(\lambda ^\prime \) is a free parameter, we can take it to be significantly larger than the values displayed in Fig. 2 where \(c=0\). As can be seen from Eq. (55), a large \(\lambda ^\prime \) results in a small \(M_X\), which increases the proton decay rate, making proton decay potentially observable. Second, a non-zero value of c modifies the gaugino masses through the matching conditions (36–38), which significantly affects the thermal relic abundance of the LSP. We will examine both of these effects in this subsection.

First, in Fig. 3a, we plot the Higgs mass \(m_h\) as a function of \(m_{3/2}\) for \(\mu < 0\), \(\lambda = 1\), \(\lambda ' = 0.5\) and \(M_\mathrm{in} = 10^{18}\) GeV, for several values of \(\tan \beta \). In the right panel (Fig. 3b), the Higgs mass is shown as a function of \(\tan \beta \) for several values of \(m_{3/2}\). The predicted value of \(m_h\) is almost independent of \(\lambda ^\prime \); \(m_h\) mainly depends on \(m_{3/2}\) and \(\tan \beta \) as in the minimal PGM model, and thus we can always explain the observed value \(m_h \simeq 125\) GeV by choosing these two parameters appropriately. Higher \(m_{3/2}\) is necessary if \(\tan \beta < 3\). Recall that \(\tan \beta \) much larger than 3 is problematic without large \(\lambda \) because we lose the ability to achieve rEWSB.

The mass of the LSP (lightest gaugino) is shown in Fig. 4 as a function of \(\lambda '\), for the same fixed values of \(\lambda , M_\mathrm{in}\), and sign of \(\mu \) used in Fig. 3. In the left panel, we fix \(\tan \beta = 3\) for several choices of \(m_{3/2}\) whereas in the right panel, we fix \(m_{3/2} = 1\) PeV for several choices of \(\tan \beta \). As can be seen from Eqs. (36–38), the gaugino masses deviate from the AMSB spectrum if \(c \ne 0\). Depending on the value of \(m_{3/2}\) and \(\tan \beta \), there is a critical value for \(\lambda '\) such that the mass of the lightest gaugino suddenly jumps from a value \(\lesssim 1\) TeV to several TeV. Recall that c is calculated from the matching conditions of the gauge couplings which depend on \(\lambda ^\prime \) through \(M_\Sigma \). The jump in the gaugino mass seen in Fig. 4 is due to a change in sign in c. Since c affects the gaugino masses as well, when c changes sign, we see a rapid increase in the wino mass. An immediate consequence of this transition is seen in Fig. 5. For low \(\lambda '\), the relic density is low as one would expect for a relatively light wino. At large \(\lambda '\), the mass of the wino increases (due to the change in c) to several TeV and therefore we see (as expected) an overdensity in the LSP. When the sign change in c occurs, it is possible to obtain the correct relic density. The red horizontal line shows the value of the relic density determined by Planck [60] and allows one to read off the requisite value of \(\lambda ^\prime \). Recall that at low \(\lambda '\), it is possible to obtain the correct relic density for lower values of \(\tan \beta \) as we saw in the previous subsection.

The mass of the lightest gaugino as a function of \(\lambda '\). In both panels, \(M_\mathrm{in} = 10^{18}\) GeV and \(\lambda = 1\) with \(\mu < 0\). In a, \(\tan \beta = 3\) showing the gaugino mass for several values of \(m_{3/2}\). In b, \(m_{3/2} = 1\) PeV, for several values of \(\tan \beta \)

As in Fig. 4, showing the relic density of the lightest gaugino given by \(\Omega _\mathrm{LSP} h^2\) as a function of \(\lambda '\). The red horizontal line shows the Planck value for the relic density

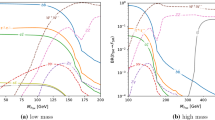

Next, we show in Fig. 6 the lifetime of the \(p \rightarrow \pi ^0 e^+\) decay channel as a function of \(\lambda ^\prime \) for fixed \(M_\mathrm{in} = 10^{18}\) GeV, \(m_{3/2} = 1\) PeV for \(\mu < 0\). In the left panel (Fig. 6a), we fix \(\tan \beta = 2.1\) and show the lifetime for several values of \(\lambda \). As we expect, the lifetime decreases as \(\lambda ^\prime \) increases. The predicted lifetime is always above the current experimental bound, \(\tau (p \rightarrow \pi ^0 e^+) > 1.6\times 10^{34}\) years [166], but can be within the sensitivity of the Hyper-Kamiokande, \(\tau (p \rightarrow \pi ^0 e^+) \simeq 7.8 \times 10^{34}\) years [167], if \(\lambda ^\prime \) is \(\mathcal{O}(1)\). The shift in the line at \(\lambda ' \simeq 10^{-4.7}\) is due to a sign change in the calculated value of c which affects the gaugino masses and gauge couplings. In the right panel (Fig. 6b), we show the lifetime for fixed \(\lambda = 1\) for several choices of \(\tan \beta \). For this choice of \(\lambda = 1\) the discontinuity in the curves due to the sign change of c occurs at higher \(\lambda ' \simeq 10^{-3.7}\).

The lifetime of the \(p \rightarrow \pi ^0 e^+\) channel as a function of the coupling \(\lambda ^\prime \) with \(M_\mathrm{in} = 10^{18}\) GeV, \(m_{3/2} = 1\) PeV, and \(\mu < 0\). In a, \(\tan \beta = 2.1\) and the lifetime is shown for several values of \(\lambda \). In b, \(\lambda = 1\) for several values of \(\tan \beta \)

A pair of (\(\lambda ,m_{3/2}\)) planes for the case with \(c \ne 0\) is shown in Fig. 7 with \(M_\mathrm{in} = 10^{18}\) GeV and \(\mu < 0\). In the upper panel, \(\tan \beta = 3\) and \(\lambda ' = 1\). As in Fig. 2, the magenta shaded region corresponds to parameter values where rEWSM is not possible. As we have seen before, this constraint forces one to relatively large values of \(\lambda \). For these parameter choices, \(\lambda \le 1\) remains perturbative up to the input scale, \(M_\mathrm{in}\). The red contours correspond to the Higgs mass in GeV. The solid green contours correspond to the proton lifetime in units of \(10^{35}\) years. For the large value of \(\lambda ^\prime \) considered here, the proton lifetime is close to but safely above the current experimental limit. Note that the fact that the proton lifetime is longer for smaller \(m_{3/2}\) has to do with the fact that the gravitino mass controls the MSSM \(\mu \) parameter (through EWSB) and hence the Higgsino masses, as well as the gaugino masses. When run up to the GUT scale these affect the unification point and unified gauge coupling and hence the proton lifetime. The black dotted curves show the values of c calculated from the gauge coupling matching conditions (31–33). The blue shaded strip corresponds to the region where the relic density falls within 3\(\sigma \) of the central value determined by Planck [60], which crosses the \(m_h = 125\) GeV contour at \(\lambda \approx 0.75\). We can compare the position of the endpoint of the relic density strip with \(\lambda = 1\) with the result in Fig. 5a where we see that the horizontal line would be crossed by a contour with \(m_{3/2}\) between 200 and 300 TeV in agreement with the endpoint in this panel.

Examples of the \(\lambda \)-\(m_{3/2}\) plane for \(M_\mathrm{in} = 10^{18}\) GeV, and \(\mu < 0\). In the upper panel, \(\tan \beta = 3\) with \(\lambda ' = 1\), and in the lower panel, \(\tan \beta = 2.4\) with \(\lambda ' = 0.001\), The solid red and dotted black curves show the Higgs mass \(m_h\) and c, respectively. The solid green contours in the upper panel show the value of the proton lifetime in units of \(10^{35}\) years. The blue shaded region corresponds to the areas where the LSP abundance agrees to the observed dark matter density. In the magenta region, we do not have successful rEWSB

In the lower panel of Fig. 7 we show the same plane with \(\tan \beta = 2.4\) and \(\lambda ^\prime = 0.001\). The Higgs masses are a bit lower, due to the decrease in \(\tan \beta \). We do not display the proton lifetime contours here because the lifetime is orders of magnitude larger than the experimental limit since \(\lambda ^\prime \) is small. Notice that there are two relic density strips in this case. In the strip with \(\lambda \gtrsim 0.5\), the relic density strip corresponds to a 3 TeV wino mass as the sign of c is changing (note the proximity of the relic density strip to the \(c = 0\) contour). This effect was seen in Fig. 5 though for different values of \(\tan \beta \). When \(\tan \beta < 3\) as it is here, the effect on the wino mass is greater and occurs at a lower value of \(\lambda ^\prime \), The relic density strip at low \(\lambda \approx 0.07\) is due to wino-bino coannihilation [105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112] where the LSP is bino-like for \(\lambda < 0.07\) and wino-like at larger \(\lambda \). The bino (and wino) mass on the strip with \(m_{3/2} = 200\) TeV is approximately 2.1 TeV.

4.3 Models with Kähler-type non-renormalizable interactions

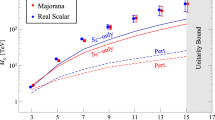

Finally, we consider the effects of both the operators (13) and (27). In this case, the Kähler-type operators (27) also modify the gaugino mass spectrum. To show the significance of this effect, in Fig. 8, we plot the gaugino masses as functions of \(\kappa _\Sigma \) for \(M_\mathrm{in} = 10^{18}\) GeV, \(m_\mathrm{3/2} = 200 \) TeV, and \(\lambda = 1\). When \(\kappa _\Sigma \) is non-zero, the contributions from \(\kappa _H\) and \(\kappa _{\bar{H}}\) are small unless these couplings are hierarchically larger compared with \(\kappa _\Sigma \). Therefore in Figs. 8 and 9 we consider only \(\kappa _\Sigma \) with \(\kappa _H\) = \(\kappa _{\bar{H}} = 0\). The lightest (second lightest) neutralino mass is shown by the solid purple (dashed green) line, while the blue dotted line shows the gluino mass. In Fig. 8a, we have taken \(\mu < 0\), \(\tan \beta = 3\) and \(\lambda ^\prime = 1\). For \(\kappa _\Sigma = 0\), the wino is the LSP, which is replaced by the bino for \(\kappa _\Sigma \gtrsim 0.1\). For \(\kappa _\Sigma \gtrsim 0.6\), the gluino becomes the LSP and thus large values of \(\kappa _\Sigma \) are phenomenologically disfavored. Near the cross-overs at \(\kappa _\Sigma \simeq 0.1\) and \(\kappa _\Sigma \simeq 0.6\), the bino LSP is degenerate with the wino and gluino in mass, respectively, and therefore we expect that coannihilation [168] is quite effective. Indeed coannihilations with gluinos has been studied at length [36, 110, 111, 113,114,115,116,117,118,119,120,121,122,123,124,125,126] and allows LSP masses significantly higher than wino or bino masses in the absence of coannihilation.

Gaugino masses as functions of \(\kappa _\Sigma \) for \(\kappa _H=\kappa _{\bar{H}}=0\), \(M_\mathrm{in} = 10^{18}\) GeV, \(m_\mathrm{3/2} = 200 \) TeV and \(\lambda = 1\). In a \(\mu < 0\), \(\tan \beta = 3\) and \(\lambda ^\prime = 1\); b \(\mu > 0\), \(\tan \beta = 3\) and \(\lambda ^\prime = 1\); c \(\mu < 0\), \(\tan \beta = 3.5\) and \(\lambda ^\prime = 1\); d \(\mu < 0\), \(\tan \beta = 3\) and \(\lambda ^\prime = 0.001\)

As seen in Fig. 8b, where we have take \(\mu > 0\), the sign of \(\mu \) plays only a small role, affecting mainly the wino mass (at \(\tan \beta < 3\) this effect becomes more pronounced). In Fig. 8c, we consider \(\tan \beta = 3.5\) with \(\mu < 0\) and is very similar to the case with \(\tan \beta = 3\). In Fig. 8d, we have taken \(\lambda ' = 0.001\). While the wino and bino masses are increased slightly, the gluino mass is decreased, and becomes the LSP at lower \(\kappa _\Sigma \approx 0.42\). We also see a sharp decrease in the wino mass due to the effect of a sign change in c, already seen in Fig. 4.

Examples of \(\kappa _\Sigma \)-\(m_{3/2}\) planes for \(\kappa _H=\kappa _{\bar{H}}=0\), \(M_\mathrm{in} = 10^{18}\) GeV, and \(\lambda = 1\). In a \(\mu < 0\), \(\tan \beta = 3\) and \(\lambda ^\prime = 1\); b \(\mu > 0\), \(\tan \beta = 3\) and \(\lambda ^\prime = 1\); c \(\mu < 0\), \(\tan \beta = 3.5\) and \(\lambda ^\prime = 1\); d \(\mu < 0\), \(\tan \beta = 3\) and \(\lambda ^\prime = 0.001\). The red and green solid contours correspond to the Higgs mass \(m_h\) and the proton lifetime \(\tau (p \rightarrow \pi ^0 e^+)\) in units of GeV and \(10^{35}\) years, respectively. The blue shaded region shows the areas where the LSP abundance agrees with the observed dark matter density. In the brown shaded region, the LSP is colored. The black dotted lines show the value of c

In Fig. 9a, we show a \(\kappa _\Sigma \)-\(m_{3/2}\) plane for \(\text {sign}(\mu ) < 0\), \(\tan \beta = 3\), \(M_\mathrm{in} = 10^{18}\) GeV, and \(\lambda = \lambda ^\prime = 1\), where the Higgs mass \(m_h\) and the proton lifetime \(\tau (p \rightarrow \pi ^0 e^+)\) are plotted in units of GeV and \(10^{35}\) years in the red and green solid curves, respectively. The black dotted curves indicate the values of c (recall again that c is calculated when \(\lambda '\) is specified). The thin blue shaded region shows the areas where the LSP abundance agrees to the observed dark matter density to within 3\(\sigma \). In the brown shaded region, the LSP is gluino and thus is phenomenologically disfavored. The gaugino masses for this case with \(m_{3/2} = 200\) TeV were shown in Fig. 8a. We see that there are two regions where both the dark matter density and the Higgs boson mass are explained. The region with \(\kappa _\Sigma \simeq 0\) is quite similar to that discussed in Sect. 4.2, and thus the LSP is wino-like. On the other hand, in the region where \(\kappa _\Sigma \simeq 0.6\), the correct relic abundance of the LSP is achieved via bino-gluino coannihilation [36, 110, 111, 113,114,115,116,117,118,119,120,121,122,123,124,125,126]. From Fig. 8a, we see that bino and gluino masses for this choice of parameters is about 4 TeV and may be just beyond the current reach of the LHC.Footnote 12 In these regions the proton lifetime is predicted to be \(\gtrsim 10^{35}\) years; to probe this, therefore, we need at least 10-years (15-years) run at Hyper-Kamiokande with a 372 kton (186 kton) detector [167].

In Fig. 9b, we show the same plane with \(\mu > 0\). Comparing panels (a) and (b) of Fig. 9, we find that they are nearly identical except for the relic density strip at low \(\kappa _\Sigma \). When \(\kappa _\Sigma \) is small, the LSP is a wino-like and more sensitive to the sign of \(\mu \). For \(\mu > 0\) and a given gravitino mass, the wino mass is lower (relative to the case with \(\mu < 0\)), and we require a higher gravitino mass to obtain the same wino mass and hence relic density. This allows us to obtain the correct relic density with a Higgs mass closer to the experimental value of 125 GeV. In Fig. 9c, we show the same plane with \(\tan \beta = 3.5\). The only significant change is the value of \(m_h\) which is roughly 2 GeV higher, making it easier to satisfy simultaneously the correct Higgs mass and relic density. The proton lifetime is hardly affected by the increase in \(\tan \beta \). Finally, in Fig. 9d, we show the same plane as in panel (a) with \(\lambda ' = 0.001\). The lower value of \(\lambda '\) causes a drop in the LSP mass (see e.g. Fig. 4) requiring an increase in the gravitino mass to obtain the same relic density. As expected from Fig. 8d, we see that the region excluded because the gluino is the LSP is larger extending down to \(\kappa _\Sigma \sim 0.4\). In this case, the proton lifetime greatly exceeds the experimental lower limit and no lifetime contours are shown. The other change apparent in panel (d) is the change in the value of c and one even sees a contour with \(c=0\) in the lower left corner of the figure. There is also a relic density contour which appears at large \(\kappa _\Sigma \) and low \(m_{3/2}\). As one can see from Fig. 8d, as \(\kappa _\Sigma \) increases the gluino mass decreases. For low \(m_{3/2}\) as in the right hand corner of this panel, the gluino mass passes through 0 and becomes large again and for \(\kappa _\Sigma > 0.8\) there is another possibility for bino-gluino co-annihilation (though \(m_h \approx 121\) GeV here).

Example of a \(\kappa _{H}\)-\(m_{3/2}\) plane for \(\kappa _\Sigma =\kappa _{\bar{H}}=0\), \(\tan \beta = 3\), \(M_\mathrm{in} = 10^{18}\) GeV, \(\lambda = \lambda ^\prime = 1\), \(\mu > 0\). The red and green solid contours correspond to the Higgs mass \(m_h\) and the proton lifetime \(\tau (p \rightarrow \pi ^0 e^+)\) in units of GeV and \(10^{35}\) years, respectively. The blue shaded region shows the areas where the LSP abundance agrees to the observed dark matter density. The black dotted lines show the value of c

When \(\kappa _H \ne 0\),Footnote 13 the contribution to \(m_H^2\) as given in Eq. (24) makes it difficult to achieve rEWSB. In Fig. 10, we show an example of a \(\kappa _{H}\)-\(m_{3/2}\) plane for \(\tan \beta = 3\), \(M_\mathrm{in} = 10^{18}\) GeV, \(\lambda = \lambda ^\prime = 1\), \(\mu > 0\). Indeed when \(|\kappa _H|\) is large, rEWSB is not attained as seen by the magenta shaded region. We see that for this choice of parameters, the relic density strip fall right about at \(m_h = 125\) GeV. In this example, the proton lifetime is rather long, and is greater than \(10^{35}\) over much of the plane.

Examples of \(\kappa _{\bar{H}}\)-\(m_{3/2}\) planes for \(\kappa _\Sigma =\kappa _{ H}=0\), \(\text {sign}(\mu ) > 0\), a \(\tan \beta = 3\), and b \(\tan \beta = 3.5\) with \(M_\mathrm{in} = 10^{18}\) GeV, and \(\lambda = \lambda ^\prime = 1\). The red and green solid contours correspond to the Higgs mass \(m_h\) and the proton lifetime \(\tau (p \rightarrow \pi ^0 e^+)\) in units of GeV and \(10^{35}\) years, respectively. The blue shaded region shows the areas where the LSP abundance agrees to the observed dark matter density. The black dotted lines show the value of c. The orange regions is for a wino LSP and the white has a bino LSP

Finally, in our last set of examples, we consider the effects of \(\kappa _{\bar{H}}\). In Fig. 11, we show a pair of \(\kappa _{\bar{H}}\)-\(m_{3/2}\) planes for \(M_\mathrm{in} = 10^{18}\) GeV, \(\lambda = \lambda ^\prime = 1\), \(\mu > 0\). In the left panel, \(\tan \beta = 3\) and in the right panel \(\tan \beta = 3.5\). In the orange shaded regions the LSP is a wino, whereas elsewhere it is a bino. Once again the proton lifetime is rather large and is greater than \(10^{35}\) over much of the plane. The Higgs mass increases by almost 2 GeV in the right panel. The relic density strip at \(\kappa _{\bar{H}} \lesssim -1\) is produced by wino-bino co-annihilations, whereas at larger \(\kappa _{\bar{H}}\) it is simply a wino LSP with mass near 3 TeV.

5 Conclusion and discussion

While the LHC has nearly closed the door on “low” energy supersymmetry due to the absence of new (colored) scalars or fermions with masses below \(\sim 1\) TeV, we are left with 2 nagging questions: Is supersymmetry a part of nature? and if so, at what scale is it manifest? Of course, the simplest way to definitively answer the first question, is through discovery, and barring good fortune at future runs of the LHC or its successor, both questions will be difficult to answer. Nevertheless, supersymmetry above the TeV scale may still have important consequences on nature, such as providing a dark matter candidate and affecting proton decay. Like anomaly mediated supersymmetry breaking, pure gravity mediation contains massive scalars with gaugino masses of order 1 to several TeV. In PGM, the scalars are invariably very heavy-of order the gravitino mass which is typically 0.1–1 PeV.

In constructing any top-down model, one must specify the scale at which supersymmetry breaking is introduced. In the CMSSM and similar models, this is usually chosen to be the GUT scale, ie. the same scale at which gauge coupling unification occurs. While there is no fundamental argument for this assumption, it does remove one free parameter, making the model as constrained as possible. If the supersymmetry breaking input scale lies above the GUT scale, the theory and low energy spectrum becomes sensitive to GUT scale parameters, such as the SU(5) Higgs self-couplings. In addition, higher order GUT operators may no longer be negligible and may also affect the low energy theory.

In relaxing the assumption of GUT scale universality, one may, if the input scale is above the GUT scale, change the boundary conditions at the GUT scale. In effect, this allows us to start with mass universality at \(M_\mathrm{in}\) and through renormalization group evolution, arrive at non-universal masses at the GUT scale for the scalars. In the absence of higher order operators, the gaugino mass spectrum is unaffected by running above the GUT scale as seen in Eq. (39). Scalar non-universality has an important effect on the Higgs soft masses in PGM which allows us to free up \(\tan \beta \). In anomaly mediated and PGM models, the gaugino mass spectrum is directly related to the coefficients of the one-loop beta functions. This leads to the lightest gaugino and hence LSP being a wino. As a consequence, to obtain the correct relic density, the lightest gaugino must have a mass of \(\sim 3\) TeV, which in turn fixes the gravitino mass. In the superGUT version of PGM, the hierarchy of gaugino masses can be altered when the effects of higher order operators are considered. These higher dimensional operators generate A- and B-terms of order \(m_{3/2}\). A- and B-terms this large give an order one correction to the matching conditions for the gauginos. This large deviation in gaugino matching conditions can lead to a bino or gluino LSP. At the boundaries between these regions with different LSP’s, coannihilation is active and the bino can be a viable dark matter candidate.

The higher dimensional operators also affect the gauge coupling matching conditions. As a result, the masses of the GUT scale gauge and Higgs bosons can be altered with strong effects on the proton lifetime.

In this work, we have sampled a variety of superGUT PGM models with and without the effects of higher order operators. GUT scale PGM is highly constrained. It has two free parameters, \(m_{3/2}\) and \(\tan \beta \) (when GM terms are included) and while possible, the parameter space with the correct relic density and Higgs mass is severely limited. In the superGUT PGM, it is relatively easy to find a viable parameter space so long as the Higgs coupling \(\lambda \) is relatively large. This is largely due to the addition of two new parameters, the supersymmetry breaking input scale, \(M_\mathrm{in}\) and the coupling \(\lambda \).

At scales at or above the GUT scale, non-renormalizable, Planck-suppressed operators may play a role in the low energy spectrum. Among these we considered first, an operator coupling between the Higgs adjoint, \(\Sigma \) and the SU(5) gauge field strength with coupling, we denoted as c. However, we used \(c \ne 0\) to free up the Higgs adjoint trilinear self coupling, \(\lambda ^\prime \) which was previously constrained by GUT matching conditions. The theory now contains 5 parameters. The non-zero coupling, c (or variable \(\lambda ^\prime \)) alters the anomaly mediated gaugino mass spectrum and makes it possible to obtain a 3 TeV wino mass for a range in gravitino masses not possible with \(c=0\). It is also possible to find regions of parameter space with a bino LSP with correct relic density when bino-wino coannihilations are active. Depending on the value of c (or \(\lambda ^\prime )\), the proton lifetime may be very large (as one might expect in PGM models) or potentially observable in on-going and future proton decay experiments when \(\lambda ^\prime \) is large.

We also considered Planck-suppressed Kähler corrections for the Higgs, 24, \(\mathbf{5}\) and \(\overline{\mathbf{5}}\) representations with respective couplings, \(\kappa _\Sigma \), \(\kappa _H\), and \(\kappa _{\overline{H}}\). These couplings induce shifts in the A- and B-terms and hence affect the gaugino matching conditions. They also induce shifts in the Higgs soft masses which affects radiative electroweak symmetry breaking. We have seen that the coupling \(\kappa _\Sigma \) has a strong effect on the gaugino mass. Even a small non-zero value for \(\kappa _\Sigma \) can cause \(m_{\tilde{B}} < m_{\tilde{W}}\), and for larger values (of order 0.4 – 0.6) can lead to a gluino LSP. When the wino/bino or bino/gluino are nearly degenerate, coannihilations may provide the correct dark matter density.

In absence of a discovery of physics beyond the Standard Model, determining the scale of supersymmetry breaking will indeed be challenging. As the mass scales associated with supersymmetry increase, the likelihood of direct detection also decreases. We may be reliant on more indirect signatures such as proton decay as discussed here, or other signatures if for example, R-parity is not exactly conserved and the LSP is allowed to decay with a long lifetime.

Data Availability Statement

This manuscript has no associated data or the data will not be deposited. [Authors’ comment: We do not have any data associated with this paper.]

Notes

It is also possible that the LSP is a Higgsino in PGM models [37].

In general, this correction can lead to an enhanced color Higgs mass and so lengthens the dimension-5 mediated proton lifetime. Since we are considering PGM, dimension-5 mediated proton decay is drastically suppressed making this correction less important.

Here, we have assumed that the VEV of the lowest component of the SUSY-breaking field is negligibly small: \(|\langle Z \rangle | \ll M_\mathrm{GUT}\).

In CMSSM-like models such as those considered in [58], there is no high scale boundary condition for the bilinear terms at \(M_\mathrm{in}\). Therefore, Eq. (42) can be used with \(\Delta = 0\) to determine \(B_H\) and \(B_\Sigma \) at \(M_\mathrm{in}\). However in a no-scale supergravity model such as that discussed in [74] or mSUGRA-like models including PGM, the boundary conditions are \(B_0 = A_0 - m_{3/2} \simeq -m_{3/2}\) at \(M_\mathrm{in}\) and a non-zero value for \(\Delta \) is required to satisfy (42). This can be achieved using either a GM term as in Eq. (12) or through the dimension 5 operator dependent on \(\omega _\lambda \) and \(\omega _\lambda '\). Note that the GM term in Eq. (12) carries a factor of two relative to that used in [74] which stems from the difference between using twisted matter fields here, relative to untwisted fields in the no-scale construction [35].

This tendency was also found in Ref. [104].

The uncertainty in \(\alpha _s\), can have a significant effect on the value of \(M_{H_C}\). However, the effect on \(M_X^2M_\Sigma \) is much weaker. This can be understood by looking at Eqs. 31 and 32. For more discussion see [149]. Since we do not consider dimension 5 proton decay, this effect is not important to our analysis.

See Ref. [30] for a recent discussion on the uncertainty in the Higgs mass calculation.

In this case, the gluino tends to be metastable because of the mass degeneracy between the bino and the gluino as well as some of the heavy sfermion masses. Such a gluino can efficiently be probed in displaced-vertex (DV) searches [125, 126], while the sensitivity of the ordinary gluino searches based on the hard jets plus missing energy signals get worse due to the mass degeneracy. Currently, the most stringent bound is given by the ATLAS DV search based on the 32.8 fb\(^{-1}\) data of the 13 TeV LHC: \(m_{\tilde{g}} > 1550\)–1820 GeV for \(\Delta m = 100\) GeV (\(\Delta m\) denotes the mass difference between gluino and the LSP) depending on the gluino lifetime [169]. This reach can be extended to \(\sim 2\) TeV in the HL-LHC or up to 10 TeV in a 100 TeV collider [170, 171].

References

M. Aaboud et al., [ATLAS Collaboration], JHEP 1806, 107 (2018). arXiv:1711.01901 [hep-ex]

M. Aaboud et al., [ATLAS Collaboration], Phys. Rev. D 97(11), 112001 (2018). arXiv:1712.02332 [hep-ex]

A.M. Sirunyan et al. [CMS Collaboration], Eur. Phys. J. C 77(10), 710 (2017). arXiv:1705.04650 [hep-ex]

A.M. Sirunyan et al., [CMS Collaboration], JHEP 1805, 025 (2018). arXiv:1802.02110 [hep-ex]

J.D. Wells, arXiv:hep-ph/0306127

N. Arkani-Hamed, S. Dimopoulos, JHEP 0506, 073 (2005). arXiv:hep-th/0405159

G.F. Giudice, A. Romanino, Nucl. Phys. B 699, 65 (2004) [Erratum-ibid. B 706, 65 (2005)]. arXiv:hep-ph/0406088

N. Arkani-Hamed, S. Dimopoulos, G.F. Giudice, A. Romanino, Nucl. Phys. B 709, 3 (2005). arXiv:hep-ph/0409232

J.D. Wells, Phys. Rev. D 71, 015013 (2005). arXiv:hep-ph/0411041

M. Dine, D. MacIntire, Phys. Rev. D 46, 2594 (1992). arXiv:hep-ph/9205227

L. Randall, R. Sundrum, Nucl. Phys. B 557, 79 (1999). arXiv:hep-th/9810155

G.F. Giudice, M.A. Luty, H. Murayama, R. Rattazzi, JHEP 9812, 027 (1998). arXiv:hep-ph/9810442

A. Pomarol, R. Rattazzi, JHEP 9905, 013 (1999). arXiv:hep-ph/9903448

J.A. Bagger, T. Moroi, E. Poppitz, JHEP 0004, 009 (2000). arXiv:hep-th/9911029

P. Binetruy, M.K. Gaillard, B.D. Nelson, Nucl. Phys. B 604, 32 (2001). arXiv:hep-ph/0011081

T. Gherghetta, G. Giudice, J. Wells, Nucl. Phys. B 559, 27 (1999). arXiv:hep-ph/9904378

E. Katz, Y. Shadmi, Y. Shirman, JHEP 9908, 015 (1999). arXiv:hep-ph/9906296

Z. Chacko, M.A. Luty, I. Maksymyk, E. Ponton, JHEP 0004, 001 (2000). arXiv:hep-ph/9905390

J.L. Feng, T. Moroi, Phys. Rev. D 61, 095004 (2000). arXiv:hep-ph/9907319

G.D. Kribs, Phys. Rev. D 62, 015008 (2000). arXiv:hep-ph/9909376

U. Chattopadhyay, D.K. Ghosh, S. Roy, Phys. Rev. D 62, 115001 (2000). arXiv:hep-ph/0006049

I. Jack, D.R.T. Jones, Phys. Lett. B 491, 151 (2000). arXiv:hep-ph/0006116

H. Baer, J.K. Mizukoshi, X. Tata, Phys. Lett. B 488, 367 (2000). arXiv:hep-ph/0007073

A. Datta, A. Kundu, A. Samanta, Phys. Rev. D 64, 095016 (2001). arXiv:hep-ph/0101034

H. Baer, R. Dermisek, S. Rajagopalan, H. Summy, JCAP 1007, 014 (2010). arXiv:1004.3297 [hep-ph]

A. Arbey, A. Deandrea, A. Tarhini, JHEP 1105, 078 (2011). arXiv:1103.3244 [hep-ph]

B.C. Allanach, T.J. Khoo, K. Sakurai, JHEP 1111, 132 (2011). arXiv:1110.1119 [hep-ph]

A. Arbey, A. Deandrea, F. Mahmoudi, A. Tarhini, Phys. Rev. D 87(11), 115020 (2013). arXiv:1304.0381 [hep-ph]

E. Bagnaschi et al., Eur. Phys. J. C 77(4), 268 (2017). arXiv:1612.05210 [hep-ph]

E. Bagnaschi et al., arXiv:1810.10905 [hep-ph]

M. Ibe, T. Moroi, T.T. Yanagida, Phys. Lett. B 644, 355 (2007). arXiv:hep-ph/0610277

M. Ibe, T.T. Yanagida, Phys. Lett. B 709, 374 (2012). arXiv:1112.2462 [hep-ph]

M. Ibe, S. Matsumoto, T.T. Yanagida, Phys. Rev. D 85, 095011 (2012). arXiv:1202.2253 [hep-ph]

J.L. Evans, M. Ibe, K.A. Olive, T.T. Yanagida, Eur. Phys. J. C 73, 2468 (2013). arXiv:1302.5346 [hep-ph]

J.L. Evans, K.A. Olive, M. Ibe, T.T. Yanagida, Eur. Phys. J. C 73(10), 2611 (2013). arXiv:1305.7461 [hep-ph]

J.L. Evans, K.A. Olive, Phys. Rev. D 90(11), 115020 (2014). arXiv:1408.5102 [hep-ph]

J.L. Evans, M. Ibe, K.A. Olive, T.T. Yanagida, Phys. Rev. D 91, 055008 (2015). arXiv:1412.3403 [hep-ph]

R. Barbieri, S. Ferrara, C.A. Savoy, Phys. Lett. B 119, 343 (1982)

G.F. Giudice, A. Strumia, Nucl. Phys. B 858, 63 (2012). arXiv:1108.6077 [hep-ph]

E. Bagnaschi, G.F. Giudice, P. Slavich, A. Strumia, JHEP 1409, 092 (2014). arXiv:1407.4081 [hep-ph]

S.A.R. Ellis, T. Gherghetta, K. Kaneta, K.A. Olive, Phys. Rev. D 98(5), 055009 (2018). arXiv:1807.06488 [hep-ph]

E. Dudas, Y. Mambrini, K. Olive, Phys. Rev. Lett. 119(5), 051801 (2017). arXiv:1704.03008 [hep-ph]

E. Dudas, T. Gherghetta, Y. Mambrini, K.A. Olive, Phys. Rev. D 96(11), 115032 (2017). arXiv:1710.07341 [hep-ph]

E. Dudas, T. Gherghetta, K. Kaneta, Y. Mambrini, K.A. Olive, Phys. Rev. D 98(1), 015030 (2018). arXiv:1805.07342 [hep-ph]

K. Kaneta, Y. Mambrini, K.A. Olive, arXiv:1901.04449 [hep-ph]

M. Drees, M.M. Nojiri, Phys. Rev. D 47, 376 (1993). arXiv:hep-ph/9207234

G.L. Kane, C.F. Kolda, L. Roszkowski, J.D. Wells, Phys. Rev. D 49, 6173 (1994). arXiv:hep-ph/9312272

H. Baer, M. Brhlik, Phys. Rev. D 53, 597 (1996). arXiv:hep-ph/9508321

H. Baer, M. Brhlik, Phys. Rev. D 57, 567 (1998). arXiv:hep-ph/9706509

J.R. Ellis, K.A. Olive, Y. Santoso, New J. Phys. 4, 32 (2002). arXiv:hep-ph/0202110

J.R. Ellis, K.A. Olive, Y. Santoso, V.C. Spanos, Phys. Lett. B 565, 176 (2003). arXiv:hep-ph/0303043

H. Baer, C. Balazs, JCAP 0305, 006 (2003). arXiv:hep-ph/0303114

A.B. Lahanas, D.V. Nanopoulos, Phys. Lett. B 568, 55 (2003). arXiv:hep-ph/0303130

U. Chattopadhyay, A. Corsetti, P. Nath, Phys. Rev. D 68, 035005 (2003). arXiv:hep-ph/0303201

J. Ellis, K.A. Olive, arXiv:1001.3651 [astro-ph.CO], in Particle dark matter, ed. G. Bertone, (pp. 142–163)

J. Ellis, F. Luo, K.A. Olive, P. Sandick, Eur. Phys. J. C 73(4), 2403 (2013). arXiv:1212.4476 [hep-ph]

J. Ellis, J.L. Evans, F. Luo, N. Nagata, K.A. Olive, P. Sandick, Eur. Phys. J. C 76(1), 8 (2016). arXiv:1509.08838 [hep-ph]

J. Ellis, J.L. Evans, A. Mustafayev, N. Nagata, K.A. Olive, Eur. Phys. J. C 76(11), 592 (2016). arXiv:1608.05370 [hep-ph]

J. Ellis, J.L. Evans, F. Luo, K.A. Olive, J. Zheng, Eur. Phys. J. C 78(5), 425 (2018) arXiv:1801.09855 [hep-ph]

N. Aghanim et al., [Planck Collaboration], arXiv:1807.06209 [astro-ph.CO]

J.R. Ellis, K.A. Olive, P. Sandick, Phys. Lett. B 642, 389 (2006). arXiv:hep-ph/0607002

J.R. Ellis, K.A. Olive, P. Sandick, JHEP 0706, 079 (2007). arXiv:0704.3446 [hep-ph]

J.R. Ellis, K.A. Olive, P. Sandick, JHEP 0808, 013 (2008). arXiv:0801.1651 [hep-ph]

J.C. Costa et al., Eur. Phys. J. C 78(2), 158 (2018). arXiv:1711.00458 [hep-ph]

L. Calibbi, Y. Mambrini, S.K. Vempati, JHEP 0709, 081 (2007). arXiv:0704.3518 [hep-ph]

L. Calibbi, A. Faccia, A. Masiero, S.K. Vempati, Phys. Rev. D 74, 116002 (2006). arXiv:hep-ph/0605139

E. Carquin, J. Ellis, M.E. Gomez, S. Lola, J. Rodriguez-Quintero, JHEP 0905, 026 (2009). arXiv:0812.4243 [hep-ph]

J. Ellis, A. Mustafayev, K.A. Olive, Eur. Phys. J. C 69, 201 (2010). arXiv:1003.3677 [hep-ph]

J. Ellis, A. Mustafayev, K.A. Olive, Eur. Phys. J. C 69, 219 (2010). arXiv:1004.5399 [hep-ph]

J. Ellis, A. Mustafayev, K.A. Olive, Eur. Phys. J. C 71, 1689 (2011). arXiv:1103.5140 [hep-ph]

E. Dudas, Y. Mambrini, A. Mustafayev, K.A. Olive, Eur. Phys. J. C 72, 2138 (2012)

E. Dudas, Y. Mambrini, A. Mustafayev, K.A. Olive, Eur. Phys. J. C 73, 2430 (2013). arXiv:1205.5988 [hep-ph]

E. Dudas, A. Linde, Y. Mambrini, A. Mustafayev, K.A. Olive, Eur. Phys. J. C 73(1), 2268 (2013). arXiv:1209.0499 [hep-ph]

J. Ellis, J.L. Evans, N. Nagata, D.V. Nanopoulos, K.A. Olive, Eur. Phys. J. C 77(4), 232 (2017). arXiv:1702.00379 [hep-ph]

J.L. Evans, K. Kadota, T. Kuwahara, Phys. Rev. D 98(7), 075030 (2018). arXiv:1807.08234 [hep-ph]

J.R. Ellis, K.A. Olive, Y. Santoso, V.C. Spanos, Phys. Lett. B 573, 162 (2003). arXiv:hep-ph/0305212

J.R. Ellis, K.A. Olive, Y. Santoso, V.C. Spanos, Phys. Rev. D 70, 055005 (2004). arXiv:hep-ph/0405110

G.F. Giudice, A. Masiero, Phys. Lett. B 206, 480 (1988)

K. Inoue, M. Kawasaki, M. Yamaguchi, T. Yanagida, Phys. Rev. D 45, 328 (1992)

J.A. Casas, C. Munoz, Phys. Lett. B 306, 288 (1993). arXiv:hep-ph/9302227