Abstract

Standard quantum mechanics is not capable of solving properly the Planck scale problems. A quantum theory of spacetime, Quantum Gravity, which could be in essence a combination of general relativity and quantum mechanics, is necessary to address the Planck scale phenomena. Natural cutoffs as fundamental characteristics of quantum spacetime are phenomenological outcomes of approaches to quantum gravity proposal. These natural cutoffs are encoded as a minimal length, a maximal momentum and a minimal momentum. These are indeed technically related to compactness of corresponding symplectic manifold in Snyder noncommutative phase space. Here we focus on the issue of particle processes and photon’s propagation in the presence of all natural cutoffs. We firstly derive a modified dispersion relation encoding these cutoffs in a massive particle process and then pay our attention to the massless photon’s dispersion relation. As a novel achievement, we show that photon’s propagation, in addition to photon’s energy, depends also on the position due to existence of a minimal measurable momentum. This novel position dependence of quantities in this framework provides new physics in the infrared regime of the background gravitational theory. We also consider frequency at the peak GW strain based on event GW170814 and investigate the possible constraints on the model parameters in this setup by treating graviton’s group velocity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Quantum mechanics and general theory of relativity are two cornerstones of modern physics. Both theories play a key role in characterizing the very natural world regardless of different scales. Contrary to the many successes that each of these theories obtained separately, they seemed to be incompatible. Quantum mechanics explains atomic and subatomic structures and general theory of relativity explains large scales towards structures in the universe. The theory of general relativity is studied in a continuous space-time manifold, while the underlying concept of spacetime in quantum mechanics is based on discrete states in essence. This contradiction in the heart of theoretical physics was one of the most controversial subjects in Science. The inconveniences between these theories appeared quite clearly as the restriction of twentieth-century physics. A more perfect explanation of nature has to embrace general relativity and quantum mechanics in a unified manner. In other words, it seems that the real essence of nature follows as a composition of quantum mechanics and general relativity.

Since gravity is coupled to everything and the ultimate description of nature should be quantum mechanical in principle, to describe all natural phenomena properly a quantum theory of gravitation is indeed inevitable. This is a very difficult task and has not been done successfully so far. But, at least from the prospect of phenomenology, if we impose quantum effects on gravity or take gravity in the framework of quantum mechanics, the very notion of space becomes a dynamical concept, and the result is a spacetime with a quantum mechanically fluctuating metric [1, 2]. In fact, in order to incorporate general relativity with quantum field theory, it was necessary to construct a new mathematical framework in which generalizes Riemannian geometry and accordingly our imagination of space and space-time [3]. In recent years and within contemporary developments in theoretical physics it has been suggested that a new kind of geometry could be incorporated into physics, and space-time itself can be reinterpreted as a discrete concept. Thusly, the candidates of quantum gravity theories come in all varieties shape and forms [4], but behind each candidate lies a common secret to why they were constructed. In other words, the underlying spacetime of all promising approaches to quantum gravity is not fundamental, but is constructed by other components, such as strings, loops, q-bits, etc. (see for instance Ref. [5]). This is the source of complication in construction of the ultimate quantum theory of gravity.

The equivalence principal tells us that gravitational field is coupled to everything. In this respect, the gravitational interaction between photon and electron in Heisenberg’s thought experiment is expected to be the origin of important effects, which are neglected in the standard quantum mechanics. Physical foundations of Heisenberg uncertainty principle in standard quantum mechanics can be examined based on Heisenberg’s thought experiment. In principle, Heisenberg’s thought experiment was designed to violate the uncertainty principle, but ultimately and surprisingly has led to the confirmation of the very principle of uncertainty. In order to determine the position of the electron in Heisenberg’s thought experiment as accurately as possible, we need to have a light with a high energy or shorter wavelength. In fact, in order to probe spacetime and to have resolution of adjacent points more accurately, we need high energetic photons as much as possible. But, based on the theory of special relativity, a higher-energy wave has also a higher equivalent mass for the photon. So, the equivalent mass of the energetic photon interacts with electron gravitationally. In the Heisenberg’s original gedanken experiment, Heisenberg ignored the gravitational interaction between the electron and the scattered photon. But, if this interaction is taken into account, then the standard uncertainty relation could be corrected. In recent years, several modifications have been introduced in the framework of various phenomenological approaches to quantum gravity proposal, the results of which are known as the Generalized (Gravitational) Uncertainty Principle (GUP). For instance, Kempf et al. presented an uncertainty relation that led to the smallest uncertainty in position measurement as \( (\Delta x_0)\) [6]

According to some evidences (for instance from string theory), this minimal uncertainty in position is of the order of the Planck length [7]. When there is a minimal length in the space-time structure, then there will be essentially a maximal energy (momentum) too. So the uncertainty principle in the presence of a minimal length and a maximal momentum will be as follows [8,9,10]

which can be investigated based on the theory of Doubly Special Relativity [11]. Eventually, if the spacetime background is curved, the fluctuations of spacetime don’t allow the uncertainty in momentum to be zero. Hence, the momentum of the system cannot be set to zero and there is always a minimal observable momentum for all systems [12]. Therefore, the uncertainty principle that includes all the natural cutoffs including minimal length, maximal momentum and minimal momentum can be represented by the following relationship [13,14,15]

This generalized uncertainty relation forms the basis of our forthcoming discussions in this paper. Of course, it should be noted that in this kind of relations there are other terms containing the expectation values of position and momentum operators, that here we set aside for the sake of simplicity. It can be shown that this procedure does not detract the generality of the discussion.

Another structure that is expected to be modified according to different approaches to quantum gravity proposal (due to the existence of natural cutoffs) is the energy–momentum dispersion relation. Particularly, a substantial contribution of quantum gravity phenomenology is considering the sequels which would become manifest if the particles obtain, because of spacetime fuzziness, some very small extra terms in the dispersion relation. Various species of phenomenological consequences of this new appearance of modified dispersion relation have been studied by authors [16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24]. This strategy has been presented fully in Ref. [24] where the authors interpreted energy-momentum relation in the presence of a minimal length and a maximal momentum. Now, we focus on a conceivable emergence of modified dispersion relation which is agreed in the majority of quantum gravity stimulated designs for testing departures from ordinary energy–momentum relation in the presence of all natural cutoffs as a minimal length, a maximal momentum and a minimal momentum. In this regard our study is one more step forward in this streamline. We treat particle processes in this framework in details. On the other hand, detection of gravitational waves via events such as GW170814 [25], which has constrained gravitational theories dramatically (see for instance [26,27,28,29,30]), provides a fascinating framework to constraint GUPs’ parameters (see also [31]). This is the issue we shall focus on and investigate via some numerical analysis.

The structure of the paper is classified as follows: in Sect. 2, we review briefly the issue of natural cutoffs which plays a significant role in approaches to quantum gravity. In Sect. 3, we focus our attention on particle processes and wave propagation in a discrete spacetime where discreteness of spacetime is an implication of the existence of a minimal length cutoff. Then we use the generalized uncertainty relation to obtain a modified dispersion relation. In Sect. 4, we consider a photon with a special gravitational background which is characterized by metric approach and we derive phase and group velocities of the system respectively. A position dependence of these quantities appears as a result of minimal momentum. In Sect. 5, inspired by the detection of gravitational waves, by setting frequency at the peak GW170817 strain in energy relation of graviton we constraint the GUP parameters in this setup.

2 Natural cutoffs and discontinuity of position and momentum spaces

In view of Planck scale physics and recent studies in this area, the existence of a minimal measurable length is undeniable, see for instance [7, 32,33,34,35,36]. In the presence of a minimal length, the representation of position space in quantum mechanics encounters with serious difficulties. When there is no possibility of resolution between adjacent points closer than the Planck length, defining a wave function with specific support (as it is the case in mathematical analysis), is impossible. If we do not consider the minimal momentum, then the representation in the momentum space is sufficient to formulate the Hilbert space of the theory. But when we consider the minimal momentum, the representation of the momentum space, as valid in standard quantum mechanics, loses its credibility. For this reason, generalization of the Hilbert space representation is necessary in the presence of natural cutoffs. Of course, quasi-position and quasi-momentum representations or maximally localized states in coordinate and momentum spaces in the framework of Bargmann–Fock theory, though complex and troublesome, present the ways to solve the issue of representation in quantum gravity [6, 8, 13,14,15]. The important point to note here is that when we consider the presence of a minimal momentum as the infrared cutoff of the theory, we mean that the position operator in our expressions is a representation of this operator in the maximal localization space or quasi-position representation of underlying quantum mechanics [6, 8]. This is an essential point in our forthcoming analysis.

3 Dispersion relations in a discrete spacetime

A significant concept in the class of waves and wave propagation is dispersion. A dispersion relation is characterized as the relation of the frequency and the wavenumber (or energy and momentum equivalently). Within the framework of the special theory of relativity, the dispersion relation is a relation between the rest mass, total energy and momentum in the form of \(E^2=(m_0c^2)^2+(pc)^2\). In recent years it has been revealed that dispersion relations could be generalized in high energy regime. As a result of Planck scale physics (at the scope of high energies or equivalently very short distances), the real spacetime has a complicated structure. In other words, spacetime at high energies and short distances has granular structure and subsequently leads to a discrete spacetime. At the high energy or short distance regime the modified dispersion relation can be expressed as \( E^2=(m_0c^2)^2+(pc)^2(1+f(p))\). This can be achieved in the framework of doubly special relativity (including the minimal length and maximal momentum constraints). To completing this process and in order to have a dispersion relation that addresses and includes all natural cutoffs, we add also a minimal momentum (as one of the implications of the curvature of spacetime) to our model [12]. In this regard, we obtain a dispersion relation which corresponds to the generalized uncertainty principle introduced in relation (3). Motivated by the modifications of position and momentum operators relationships in the Planck scale physics, we firstly specify the standard 4-momentum, modified 4-momentum and modified position operator respectively as \( p^a \), \( P^a \) and \( X^a \). In this regard, the following relationships exist between standard and modified operatorsFootnote 1

where \(\alpha \) and \(\eta \) are small parameters, \(p^2=\delta _{ij}p^ip^j\) and \(x^2=\delta _{ij}x^ix^j\). To prove that these maps are capable of realizing the generalized algebra

we set

and we find

Since the last term of this relation is absent in relation (6), so we set \(\alpha _{3}=0\) and \(\alpha _{4}=0\). Now comparing the result with (6), we find \(\alpha _{1}=-\alpha \) and \(\alpha _{2}^{2}=2\alpha ^{2}\). In this situation, we have \([P_{i},P_{j}]\sim -2i\hbar \eta _{2}^{2}L_{ij}\) where \(L_{ij}=x_{i}p_{j}-x_{j}p_{i}\). In order to get no effect in the curvature of the spacetime, we demand that \(\eta _{2}=0\) and we recover the algebra (6) or the generalized uncertainty (3) by setting \(\eta _{1}^{2}=2\eta ^{2}\). As an important result, we see that just by the assumption \(\eta _{2}=0\) (that is, \([P_{i},P_{j}]=0\)) we are faced with a flat spacetime (space of \(X^{i}\)’s).

Now we consider a set of metrics based on the model (following Ref. [24]). Remembering that the gravitational background metric is expressed as followsFootnote 2

and continuing on this line, the result in terms of square of 4-momentum is

For simplicity, we preserve terms of the order of \(\alpha ^2\) and \( \eta ^2\), namelyFootnote 3

Clearly, the standard dispersion relation can be recovered easily from the above relation as

Now, proceeding on this manner by using the relation (5) and writing the standard momentum based on the modified momentum as \(p^i=P^i(1+\alpha p-2\alpha ^2 p^2-2\eta ^2x^2)\), and then by applying this definition in (12), the corresponding dispersion relation is obtained by the Generalized Uncertainty Principle (3) as follows

In this regard, quantum gravity corrections can be interpreted as a modification of the particle’s mass. So, the quantity of effective mass in this framework appears as follows

This relation has some interesting physical implications. As it is seen, now the mass of the particle is position dependent. We note that position x here can be interpreted as maximal localization of the particle in the language of maximally localized states, or quasi-space coordinate (operator) in quasi-space representation. Albeit, position dependence of particles’ mass is familiar in, for instance, condensed matter physics. There are various models toward quantum mechanical systems that imply the position-dependent mass in physics, see for instance [38, 39]. Generally, the mass of the particle that interacts with an external environment appears to be an effective mass that depends on the position. Further treatment on this issue is desirable to extend our knowledge in this content. Using the peculiarity of metric (9) and the gravitational background energy as \(E=-g_{00}\,c\, p^0\), we extract the time component of momentum from (13) in the form

In this situation we can express energy of the particle as

This is a position dependent particles’ energy or equivalently a position dependent dispersion relation. Given the above relation for a particular Minkowski spacetime in which \(g_{00}=-1\) and in the absence of quantum gravity corrections i.e. \(\alpha ,\eta \rightarrow 0\), the standard dispersion relation is recovered. It should be noted that Majhi and Vagenas have investigated the corrective effects of quantum gravity in the state \(\eta =0 \) in reference [24].

4 Phase and group velocities

After deducing the modified dispersion relation (16) that addresses the effects of all natural cutoffs, now we treat some kinematical issues in this setup. In this respect, to expand our understanding about the propagation of waves and the role of modified dispersion relation, we discuss the phase and group velocities in this context. Consider a photon with a special gravitational background described by Eq. (9). Recalling this point, the phase velocity of each particle including massive or massless is defined as the ratio of the relativistic energy and its momentum as \(v_{ph}\equiv (-g_{00})^\frac{1}{2}\frac{E}{P}\). Thus we can write the phase velocity in the following form

The group velocity of particles including massive or massless particles is defined as the derivative of the relativistic energy with respect to its relativistic momentum as \( v_g\equiv (-g_{00})^\frac{1}{2}\frac{\partial E}{\partial P} \), so we obtain modified group velocity as follows

Eventually, from Eqs. (17) and (18) we get

where for \(m=0\) gives

In the standard case (where \(\alpha ,\eta =0\)), the product of the phase and group velocities is in the form of \(v_{ph}v_g=(-g_{00})c^2\). Here there is a correction factor which appears as a result of existence of natural cutoffs. The new and important ingredient of this relation is its position dependence.

In fact, existence of a minimal momentum for the test particle due to the curvature of the background geometry is the basis of such a position dependence. So, when one incorporates an IR cutoff as a manifestation of minimal momentum, a position dependence appears in all kinematical quantities of the theory. To shed more light on this novel phenomenon, we note that in the presence of a minimal measurable length, the position space representation of the Hilbert space of the standard quantum mechanics breaks down [6]. Then one can do all calculations in momentum space without any difficulty. If one insists on using the position space representation in the presence of a minimal length, then one has to go to the maximally localized states or quasi-space representation to handle the problem. When there is also an additional cutoff, a minimal measurable momentum, then momentum space representation of the Hilbert space of the standard quantum mechanics breaks down too. To overcome these issues, Maximally Localized States in position or momentum spaces are introduced successfully [8]. Since existence of a minimal measurable momentum (as an IR cutoff) in the GUP is addressed by the term containing position operator, it is so important to say trivially that what are the eigenvalues of this position operator. One can do all of calculations in Maximally Localized States or equivalently in Quasi-Space Representation to distinguish clearly the eigenvalues of the position operator. Now, about the phrase “position” in our context we note that this is the position of the received graviton with respect to, for instance, the laboratory observer. This is actually a symmetry breaking model as can be seen in Ref. [40]. This feature can be described also as some intrinsic uncertainty of the emission point with respect to the observer. One may argue that why should we take into account such a contribution when we have only a vague idea of the exact emission (or reception) point of the gravitational wave? By working in a generalized Hilbert space based on Maximally Localized States or Quasi-Position Representation this feature is understandable. We mean that now we are faced (and working) with a generalized representation that is based on a discretized space where gravitons is propagating.

Now, if we assume the particle to be massless, by setting \(m=0\) in (16) we find

In order to express the above relation in terms of energy, we solve Eq. (16) for P and then we propose to use an iteration method as described in [24]. This procedure will be used to compute the energy of the system based on relation (16). The solution of the zeroth-order for P is obtained by putting \(\alpha , \eta =0 \) in relation (16)

Now, we replace the solution of the zeroth order to P to find

After substituting Eq. (22) into Eq. (16) one can write

So the iterative process with P goes into an infinite loop without converging. As a corollary, the velocity of the photon is corrected as follows

Given this relation, if we consider a certain model of the Minkowski spacetime, i.e. \(g_{00}=-1\) and in the absence of quantum gravity effects (\(\alpha ,\eta =0\)), the relation (25) should recover the photon’s velocity with the standard dispersion relation, that is, c. Therefore, in this framework, we must choose the sign of the first term in the right hand side to be positive. Therefore, the modified photon velocity is as follows

As is demonstrated in this equation, in this new structure (the presence of natural cutoffs in the theory), the photons velocity not only depends on energy, but also depends on the position of the particle. Moreover, since, based on the relation (26), photon’s velocity u can attain values greater than the speed of light [for example, when the symbols in (25) are all positive], the propagation of photons at speeds greater than the speed of light is essentially allowed in this theory due to gravitational quantum corrections. Note that dependence of this velocity to the position of the photon, which is indicated by the presence of the position in (26), has the origin on the presence of the minimal momentum as a natural infrared cutoff.

5 Bounds on the GUP parameters based on the gravitational wave event GW170817

Perception of gravitational waves, which started up with the discovery of an occurrence by LIGO in 2015 and then LIGO and VIRGO revolutionary discoveries in 2017 with further progresses then after, has opened new and promising window on fundamental physics. In this section we consider gravitational waves data from GW170814 event in order to investigate possible constraints on the model parameters in this setup. To proceed we analyze the problem by adding cutoffs gradually. That is, we firstly consider the case just with a minimal length. Then we add the maximal momentum and finally we treat the case with all natural cutoffs. We note that this issue has been considered for the first two cases in Ref. [31] with data from GW150914. We reconsider these two cases with more recent data from GW170814 to find more updated constraints. The case with all natural cutoffs together is totally novel by special focus on infrared cutoff.

To constraint our setup with GW data, we firstly derive the difference between gravitational and electromagnetic waves in the frameworks of the standard uncertainty principle and the generalized uncertainty principle. In the framework of the standard uncertainty principe, a simple analysis based on the relativistic dispersion relation \(p_{a}p^{a}=-m^{2}c^{2}\) gives \(E^{2}\equiv (-g_{00}c p^{0})^{2}=-g_{00}(p^{2}c^{2}+m^{2}c^{4}\)) where we have used the fact that GW observation is in a weak gravitational background and hence \(g_{00}=-1\). So, the graviton’s speed is given by [31]

where \(E_{g}\) and \(m_{g}\) are the energy and rest mass of gravitons. Now the difference between the speed of gravitons and photons (light) is given by \(\delta v=c-v_{g}=\frac{m_{g}^{2}c^{5}}{2E_{g}^{2}}\). The data from GW170814 gives frequency at peak GW strain from 155 to 203 Hz leading to the maximum energy of gravitons as \(E_{g}=h\nu \approx 8.4\times 10^{-13}\) eV. The upper bound for the mass of gravitons calculated based on the analysis provided in Ref. [41] (which considers Solar system versus gravitational wave bounds on the graviton mass via constraint on the wavelength of gravitons) is \(m_{g}\approx 4.4 \times 10^{-22}\) eV/\(c^{2}\). Therefore, we find \(\delta v\approx 4.1 \times 10^{-11}\) m/s.

For the case of GUP with just a minimal measurable length following Ref. [31] we consider the GUP as \(\Delta x\Delta p\ge \frac{\hbar }{2}(1+\beta (\Delta p)^2)\). Following the same procedure as the previous paragraph, we find \(E^{2}=m^{2}c^{4}+p^{2}c^{2}(1-2\beta p^{2})\). In this case the speed of graviton as a massless particle is given by \(v_{g}=\frac{\partial E}{\partial p}\approx c(1-3\beta p^{2})\). Since \(E_{g}=p_{g}c\), we find \(v_{g}\approx c(1-3\beta \frac{E_{g}^{2}}{c^{2}})\). So, the following result is obtained

where \(M_{p}\) is the Planck mass. We see that quantum gravitational effect encoded in GUP reduces the speed of gravitational waves in essence. Now if we use the value of \(\delta v\) obtained in previous part as an upper bound, it is possible to constraint \(\beta _{0}\) as follows:

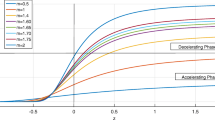

Note that this result is one order of magnitude better than the result obtained in Ref. [31] which was obtained by the 2015 GWs data. Figure 1 gives the frequency at the peak GW strain versus \(\beta _{0}\) for this case. The shaded region gives the acceptable range of \(\beta _{0}\) based on the GW170814 data.

In the first step, we extend our study to the case with a minimal length and maximal momentum. In this case with the GUP as \(\Delta x\Delta p\ge \frac{\hbar }{2}(1-\alpha p+2\alpha ^{2}(\Delta p)^2)\), by some simple calculation in the lines of the previous parts, we find \(v_{g}\approx c(1-2\alpha \frac{E_{g}}{c})\) and therefore, \(\delta v=c-v_{g}\approx 2\alpha E_{g}\). By using the value of \(\delta v\) obtained in the first case as an upper bound, that is, by setting \(\delta v\le 4.1 \times 10^{-11}\) m/s, we have \(2\frac{\alpha _{0}}{M_{p}^{2}c^{2}}E_{g}\le 4.1 \times 10^{-11}\) m/s which gives the following bound on \(\beta _{0}\) by using the GW170814 event data

We note that this bound is different from the result reported in Ref. [31] in numerical coefficient (see Eq. 32 in this reference that should be actually \(2.68\times 10^{20}\)). Figure 2 gives the frequency at the peak GW strain versus \(\alpha _{0}\) for this case. The shaded region gives the acceptable range of \(\alpha _{0}\) based on the GW170814 data.

Now we pay our attention to the most general form of GUP with all natural cutoffs including minimal length, maximal momentum and minimal momentum. We start with the GUP as

With this GUP we find the dispersion relation as

Now, up to the second order of the GUP parameters, we find \(v_{g}\approx c-2c\eta ^{2}x^{2}-\frac{3}{2}cp^{2}\alpha ^{2}+2cp\alpha \) which gives \(\delta v =c-v_{g}=2c\eta ^{2}x^{2}+\frac{3}{2}cp^{2}\alpha ^{2}-2cp\alpha \), or in terms of \(E_{g}\) as

Once again, by using \(\delta v\le 4.1 \times 10^{-11}\) m/s, we find

The phase plane of \(\alpha _{0}\)–\(\eta _{0}\) for two different values of the frequency at the peak GW strain, \(\nu =155\) and \(\nu =203\) as lower and upper frequencies at the peak GW strain. The shaded regions in these two panels give the allowed values of \(\alpha _{0}\) and \(\eta _{0}\) based on GW170817 data

where by definition \(\eta =\hbar \frac{\eta _{0}}{M_{p} c}\) and \(\alpha =\frac{\alpha _{0}}{M_{p}c}\) . Now we should decide about the value of \(x^{2}\). Actually x is the position of a test particle in the presence of all natural cutoffs. Because of existence of a minimal uncertainty in position, it is impossible to localize the particle perfectly. So, based on the seminal work of Kempf et al. [6] we have to consider maximal localization or quasi-space representation to speak about localization of the test particle. We work in maximally localized state representation and suppose the particle is situated around the origin with \(x\sim l_{p}=\frac{\hbar }{M_{p}c}\). So we find

To proceed further, we work in two different fashion. Firstly we use the constraint on \(\alpha _{0}\) from (29) to find a constraint on \(\eta _{0}\). This gives

The other way is to find a constraint on \(\alpha _{0}\) and \(\eta _{0}\) in the phase plane \(\alpha _{0}\)–\(\eta _{0}\). For this goal, we numerically analyze a constraint on this phase plane in the background of GW170814 data. The results of these analysis are shown in Fig. 3 for two different values of the frequency at the peak GW strain, \(\nu =155\) and \(\nu =203\) as lower and upper frequencies at the peak GW strain. The shaded regions in these two panels give the allowed values of \(\alpha _{0}\) and \(\eta _{0}\) based on GW170814 d ata.

Finally, to see the situation for other values of frequencies in the range \(\nu =155\)–\(\nu =203\), Table 1 gives a detailed numerical values of \(\eta _{0}\) based on GW170817 data with the constraint on \(\alpha _{0}\) as \(\alpha _{0}=9.93\times 10^{20}\).

As the final argument, in Sect. 4 we defined some deformed expressions for the group/phase velocity of photons, asserting that it may vary from c, depending on the photon’s observables. However in Sect. 5 we only looked for modifications in the graviton’s velocity, giving for granted an unmodified speed of light. It is not astonishing to have deformed expressions for photon’s velocity from QG phenomenology, but the reason that in Sect. 5 we have looked just for modifications in the graviton’s velocity and considered unmodified speed of light is the fact that we were seeking for some constraints on the QG parameters (\(\alpha \) and \(\eta \)) of the model at hand by using the observational data related to the detection of gravitational wave from LIGO and VIRGO. The data from black holes merger released by LIGO and VIRGO show a very small time deference between reception of gravitational waves and the companion electromagnetic waves, \(|\frac{c_{g}}{c}-1|\le 5\times 10^{-16}\). In fact, multimessenger gravitational-wave (GW) astronomy has commenced with the detection of the binary neutron star merger GW170817 and its associated electromagnetic counterpart. The almost coincident observation of both signals places an exquisite bound on the GW speed as \(|\frac{c_{g}}{c}-1|\le 5\times 10^{-16}\) [28]. Since we were seeking for some constraints on the parameters \(\alpha \) and \(\eta \) by using this observational bound, it is permissible to consider the modifications imposed just on the graviton’s speed. We know that in this context photon’s velocity could be modified too, but graviton probably feels some quantum spacetime effects since gravitons is actually the ripples of spacetime itself. In fact, we considered the photon’s uncertainty principle as “classic” while the graviton’s one “feels” some quantum spacetime effects. Note also that the graviton’s energy is so narrow that only allows to shrink the parameter’s space to less than \(10^{60}\) or \(10^{20}\). However, it is so important to find some severe constraints on the free parameters of the GUP (QG parameters). Since GUPs are actually some phenomenological aspects of the ultimate quantum gravity, any step forward to better understanding the issue is appreciable. It is a positive point of our work that uses the latest released data of GW for study of a phenomenological aspect of QG.

6 Summary and conclusion

The issue of massive and massless particles propagation (by focusing on the phase and group velocities) in the presence of natural cutoffs has been studied in this paper. While the presence of a minimal length and a maximal momentum causes no considerable complication due to applicability of momentum space representation, the presence of a minimal measurable momentum (as a consequence of a limited resolution in momentum space due to curvature of background manifold which leads to an infrared cutoff) faces with a conceptual issue. This is because of the presence of position x in the generalized uncertainty relations and also all kinematical quantities such as the phase and group velocities, from the representation point of view. In another words, the question arises that what is x in, for instance, group velocity. We argued that this issue can be addressed by using quasi-position or maximally localized space representation in the presence of a minimal length cutoff. In this manner we were able to treat the issue of massive and massless particles propagation in the presence of both the ultra-violet and infra-red cutoffs. Then we obtained a position dependent effective mass and energy for a test particle. The phase and group velocities for this general case are also position dependent in the language of quasi-position or maximally localized states. What is important in this kind of studies is possible constraints on the quantum gravity parameters appeared via generalized uncertainty principle. We have used the frequency at the peak GW strain based on the event GW170814 and investigated the possible constraints on the model parameters in this setup by treating graviton’s group velocity. In this way we were able to find severe numerical constraints on the GUPs parameters for several cases encoded in figures.

Data Availability Statement

This manuscript has no associated data or the data will not be deposited. [Authors’ comment: Actually all the data (mathematical and numerical) are included in the manuscript and we have no other data regarding this article.]

Notes

According to the Darboux theorem, one can always find a local chart in which any structure takes the canonical form as the corresponding algebra becomes commutative. At the classical level, models such as the generalized uncertainty principle (our case), and also any model which includes natural UV and IR cutoffs, can be realized from the deformed Hamiltonian system. Such systems are usually led to deformed noncanonical Poisson algebras with non-vanishing commutation relations between positions and momenta which signal the existence of UV and IR cutoffs respectively. This is, however, a local criterion and we know that the Hamiltonian system are described by the symplectic manifolds which are locally equivalent. Any noncanonical Poisson algebra then can be transformed to a canonical form in the light of the Darboux theorem [37].

We note that in our framework one can show that \([X_{i}, X_{j}]\sim -2i\hbar \eta ^{2}L_{ij}\). Then \([X_{i}, X_{j}]\ne 0\) shows that the momentum space gets quantum gravity modification while, \([P_{i},P_{j}]=0\) ensures that spacetime (space of \(X^{i}\)’s) would not get any quantum gravity modification. This is actually our case. More precisely, the curvature of any space is defined by the noncommutativity of the associated translation operator. Much similar to the General Relativity where \([\nabla _{\mu },\nabla _{\nu }]\propto Curvature\) and momenta \(\nabla _{\mu }\) (translation operator in coordinate space) are noncommutative, here the translation operator for momentum space, that is, \(X^{i}\)’s are noncommutative and therefore \([X_{i}, X_{j}]\) gives the curvature of the momentum space. So, in our framework we are working with \([P_{i},P_{j}]=0\) which is the reason why we have not changed the line-element. Since in our case \([X_{i}, X_{j}]\ne 0\), so we are faced with a curved momentum space and therefore modified dispersion relations.

We note our analysis in this paper are not exact and all of our calculations are essentially perturbative and up to the second order in QG parameters \(\alpha \) and \(\eta \). Nevertheless, we have not used the symbols \(\simeq \) or \(\approx \) in equations just for simplicity of notation as is usual in related literature.

References

A. Ashtekar, New J. Phys. 7, 188 (2005)

A. Ashtekar, J. Lewandowski, Class. Quant. Gravit. 21, R53 (2004)

H.F. Yu, B.Q. Ma, Mod. Phys. Lett. A 32, 1750030 (2017)

C. Rovelli, Living Rev. Relativ. 1, 1 (1998)

T. Thiemann, Lect. Notes Phys. 631, 41–135 (2003)

A. Kempf, G. Mangano, R.B. Mann, Phys. Rev. D 52, 1108 (1995)

D. Amati, M. Ciafaloni, G. Veneziano, Phys. Lett. B 216, 41 (1989)

K. Nozari, A. Etemadi, Phys. Rev. D 85, 104029 (2012)

A.F. Ali, S. Das, E.C. Vagenas, Phys. Lett. B 678, 497 (2009)

S. Das, E.C. Vagenas, A.F. Ali, Phys. Lett. B 690, 407 (2010)

J.L. Cortes, J. Gamboa, Phys. Rev. D 71, 065015 (2005)

H. Hinrichsen, A. Kempf, J. Math. Phys. 37, 2121–2137 (1996)

M. Roushan , K. Nozari, AHEP, Article ID 353192 (2014)

K. Nozari, M. Roushan, IJGMMP 13, 1650054 (2016)

M. Roushan, K. Nozari, IJGMMP 15, 1850136 (2018)

R. Gambini, J. Pullin, Phys. Rev. D 59, 124021 (1999)

J. Alfaro, H.A. Morales-Técotl, L.F. Urrutia, Phys. Rev. Lett. 84, 2318 (2000)

G. Amelino-Camelia, M. Arzano, A. Procaccini, Phys. Rev. D 70, 107501 (2004)

G. Amelino-Camelia, M. Arzano, Y. Ling, G. Mandanici, Class. Quant. Gravit. 23, 2585 (2006)

G. Amelino-Camelia, M. Arzano, A. Procaccini, Int. J. Mod. Phys. D 13, 2337 (2004)

G. Amelino-Camelia, Nature 410, 1065 (2001)

J. Magueijo, L. Smolin, Phys. Rev. D 67, 044017 (2003)

G. Amelino-Camelia, Int. J. Mod. Phys. D 11, 35 (2002)

B.R. Majhi, E.C. Vagenas, Phys. Lett. B 725, 477 (2013)

The LIGO Scientific Collaboration and The Virgo Collaboration, Phys. Rev. Lett. 119, 161101 (2017)

P. Creminelli, F. Vernizzi, Phys. Rev. Lett. 119, 251302 (2017)

J. Sakstein, B. Jain, Phys. Rev. Lett. 119, 251303 (2017)

J. MaríaEzquiaga, M. Zumalacárregui, Phys. Rev. Lett. 119, 251304 (2017)

S. Nojiri, S.D. Odintsov, Phys. Lett. B 779, 425 (2018)

D. Langlois, R. Saito, D. Yamauchi, K. Noui, Phys. Rev. D 97, 061501 (2018)

Z.-W. Feng, S.-Z. Yang, H.-L. Li, X.-T. Zu, Phys. Lett. B 768, 81 (2017)

G. Veneziano, Europhys. Lett. 2, 199 (1986)

D.J. Gross, P.F. Mende, Nucl. Phys. B 303, 407 (1988)

K. Konishi, G. Paffuti, P. Provero, Phys. Lett. B 234, 276 (1990)

M.R. Douglas, N.A. Nekrasov, Rev. Mod. Phys. 73, 977 (2001)

F. Girelli, E.R. Livine, D. Oriti, Nucl. Phys. B 708, 411 (2005)

K. Nozari, M.A. Gorji, V. Hosseinzadeh, B. Vakili, Class. Quant. Gravit. 33, 025009 (2016)

T. Gora, W. Ferd, Phys. Rev. 177, 1179 (1969)

O. von Roos, Phys. Rev. B 27, 7547 (1983)

M. Faizal, Phys. Lett. B 757, 244 (2016)

C.M. Will, Phys. Rev. D 57, 2061 (1998)

Acknowledgements

We really appreciate the referee for very insightful comments that have boosted the quality of the paper considerably. We would like to thank Dr M. A. Gorji and Dr Narges Rashidi for fruitful discussions. The work of K. Nozari has been supported financially by Research Institute for Astronomy and Astrophysics of Maragha (RIAAM) under research project number 1/6025-50.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Funded by SCOAP3

About this article

Cite this article

Roushan, M., Nozari, K. Particle processes in a discrete spacetime and GW170814 event. Eur. Phys. J. C 79, 212 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1140/epjc/s10052-019-6714-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1140/epjc/s10052-019-6714-7