Abstract

We make comparison of the dynamics of the diagonal and nondiagonal Bianchi IX models in the evolution towards the cosmological singularity. Apart from the original variables, we use the Hubble normalized ones commonly applied in the examination of the dynamics of homogeneous models. Applying the dynamical systems method leads to the result that in both cases the continuous space of critical points is higher dimensional and they are of the nonhyperbolic type. This is a generic feature of the dynamics of both cases and seems to be independent on the choice of phase space variables. The topologies of the corresponding critical spaces are quite different. We conjecture that the nondiagonal case may carry a new type of chaos different from the one specific to the usually examined diagonal one.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

According to the singularity theorems of General Relativity (GR), the evolution of an expanding universe is geodesically past-incomplete. The Belinskii, Khalatnikov and Lifshitz (BKL) [1, 2] scenario predicts that on approach to a space-like cosmological singularity the dynamics of gravitaional field simplifies as time derivatives in Einstein equations dominate over spatial derivatives (see [3] for numerical support for BKL). In this regime the evolution of the Universe becomes strongly non-linear and chaotic, comprising expanding and contracting oscillatory phases around the singular point. One believes that an imposition of quantum rules onto this scenario may heal the singularity. Finding the nonsingular quantum BKL scenario would mean solving, to some extent, the generic cosmological singularity problem. Such a quantum theory could be used as a realistic model of the very early Universe.

Quantization of the BKL scenario should be preceded by the quantization of the Bianchi IX model. This seems to be a reasonable strategy because the BKL scenario has been obtained via analysis of the dynamics of the Bianchi IX spacetime. The three metric on space of the Bianchi IX model (in the synchronous reference system) is in general nondiagonal for general matter models. However in the case of vacuum or simple fluids it can be diagonalized during the entire evolution of the system. We refer to these two cases as nondiagonal and diagonal Bianchi IX models, respectively. The best prototype for the BKL scenario is the nondiagonal Bianchi IX model [2, 4, 5] corresponding to general matter fields.

The quantization of the Bianchi IX model requires full understanding of its classical dynamics in terms of variables convenient for quantization procedure. Our recent paper [6] has initiated such analysis. As far as we [7, 8] and references therein). The examination of the dynamics presented in [9] of the nondiagonal case is mathematically satisfactory, but seems to be too complicated to be used in any quantization scheme.

Recent analysis indicate that the dynamics of the nondiagonal case has asymptotic regime near the singularity [10]. The dynamics of this regime looks similarly to the dynamics of the diagonal case (devoid of asymptotic regime). However, the symmetry aspects of both set of equations defining the corresponding dynamics are quite different, which leads to the different topologies of the corresponding spaces of solutions. The aim of this paper is the examination of these differences in more details.

In this paper we use two quite different sets of variables parameterizing the dynamics: original BKL type [4, 5] and quasi Hubble normalized [11]. Making use the scale invariance of Einstein equations one can introduce variables which divided by the Hubble parameter become scale invariant [12]. The Hubble parameter, which in general spacetime is a geometrical average of expansion rates in three space directions, becomes infinite approaching the singularity. Although gravitational field variables like orthonormal frame variables also diverge approaching singularity, normalized by Hubble parameter remain finite and more useful for analytical analysis [8, 12], and they enabled successful numerical verification [3].

However, original BKL variables and Hubble normalized ones cannot be connected by canonical transformation. In both cases, applying dynamical systems method enables identification of the spaces of non-isolated critical (equilibrium) points, which are of nonhyperbolic type. Topologies of these spaces are quite different, and making them explicit constitutes one of the main results of this paper. Additional result is expressing the asymptotic nondiagonal Bianchi IX model in terms of non-divergent variables similar to the Hubble normalized variables, thus enabling future more detailed investigations.

Our paper is organized as follows: Sect. 2 concerns the nondiagonal case. We introduce quasi Hubble normalized variables, examine the asymptotic dynamics in these (and BKL) variables, and identify the spaces of critical points of the corresponding vector fields. The diagonal case is considered in Sect. 3, where we follow the steps of Sect. 2. The numerical simulations of the dynamics is presented in Sect. 4. We conclude in Sect. 5. Appendix A concerns the issue of an effective form of the metric near the singularity. The choice of quotient coordinates, presented in “Appendix B”, enables making an extension of the interpretation of our results. We present the relationship between the BKL and our new variables in “Appendix C”. Finally, we apply the Poincaré sphere to deal with the space of critical points in finite region of phase space in “Appendix D”.

2 The nondiagonal case

The general form of a line element of the nondiagonal Bianchi IX model, in the synchronous reference system, reads

where Latin indices \(a,b,\ldots \) run from 1 to 3 and label the frame vectors \(e^a_\alpha \), and Greek indices \(\alpha ,\beta ,\ldots \) take values 1, 2, 3 and concern space coordinates, and where \(\gamma _{ab}\) is a spatial metric.

It was shown in [1, 2] that near the cosmological singularity the general form of the metric \(\gamma _{ab}\) should be considered. Consequently, one cannot globally diagonalize the metric, i.e. for all values of time. After making use of the Bianchi identities, freedom in the rotation of the metric \(\gamma _{ab}\) and frame vectors \(e^a_\alpha \), one arrives at the well-defined, but complicated system of equations specifying the dynamics of the nondiagonal Bianchi IX model [5]. Assuming that the anisotropy of space may grow without bound, when approaching the singularity, enables considerable simplification of the dynamics. Finally, the asymptotic form (near the cosmological singularity) of the dynamical equations of the nondiagonal Bianchi IX model reads [4,5,6]:

where a, b, c are functions of time \(\tau \), satisfying the constraint

and where \(\tau \) is connected with the cosmological time variable t as follows

(\(\gamma \) denotes the determinant of \(\gamma _{ab}\)).

Turning the above dynamics into Hamiltonian dynamics, one can examine qualitatively the mathematical structure of the corresponding physical phase space by using the dynamical systems method (DSM). It has been found that the critical points of the system have the following properties: (i) define a three-dimensional continuous subspace of \({\bar{{\mathbb {R}}}}^6\) defined by the relation \(a \gg b \gg c > 0\), with \(a \rightarrow 0\) (see, Eq. (38) of [6] for more details), and (ii) are of the nonhyperbolic type.

The property (i) was already found long time ago [5] without using the DSM. The characteristic (ii) has been identified recently [6]. The latter property means that getting insight into the structure of the space of orbits near such critical set requires further examination of the exact nonlinear dynamics. So the results obtained from inearization of the dynamics cannot be conclusive (see, e.g., [14]).

2.1 Quasi Hubble normalized variables

To make progress in understanding the structure of our critical set, we propose the parametrization of the dynamics by an analog of the so-called Hubble-normalized (HN) variables \(({\tilde{\Sigma }}_\alpha ,{\tilde{N}}_\alpha )\) (see, e.g., [11,12,13] and references therein). They can be ascribed to the vacuum Bianchi type models in which case the spatial metric can be taken to be diagonal. Assuming a spacetime admitting a foliation \({\mathcal {M}}\mapsto \Sigma \times {\mathbb {R}}\), where \(\Sigma \) is spacelike, the line element of the spatially homogenous Bianchi type model reads, following the original notation of [11,12,13]:

where the \(\omega ^\alpha \)’s are 1-forms on \(\Sigma \) invariant with respect to the action of a simply transitive group of motions on the leaf and subject to

where \({\hat{n}}_{\alpha }\) are structure constants of the corresponding Lie algebra. In case of the Bianchi IX model \({\hat{n}}_{\alpha }=1\).

Within this framework one can define the expansion \(\theta \) and the shear \(\sigma ^\alpha _{\ \beta }\):

where \(k_{\alpha \beta }\) is the second fundamental form associated with hypersurfaces \(\{t=\text {const.}\}\) and \(\sigma _\alpha \) fulfill \(\Sigma _\alpha \sigma _\alpha =0\). The Hubble variable H is proportional to the expansion \( H= \theta /3\) and is related to changes of the spatial volume density via \(d \sqrt{g}/dt= 3 H \sqrt{g}\), where \(g=\text {det} g_{\alpha \beta }\). One can also define variables \(n_\alpha \)

For the Bianchi IX model there exists a one-to-one correspondence between the set of the definded above variables \((H, \sigma _\alpha , n_\alpha )\) (with \(\Sigma _\alpha \sigma _\alpha =0\)) and the standard ones \((g_{\alpha \beta },k_{\alpha \beta })\). In this setting one can introduce the Hubble normalized (HN) variables \(({\tilde{\Sigma }}_\alpha ,{\tilde{N}}_\alpha )\) (here we use symbol \(\tilde{}\) for distinguishing the original variables and our subsequent ones), which are orthonormal frame variables \(\sigma _\alpha \) and \(n_\alpha \) normalized by the Hubble variable H:

These are dimensionless quantities which fully describe the dynamics of the three-dimensional spacelike hypersurface \(\Sigma \). Near the singularity, where space curvature and expansion all diverge, the HN variables remain finite, as dividing by divergent Hubble variable H factors out the overall expansion. Analysing dynamics of the Bianchi IX spacetimes near its singularity in terms of HN variables brought a lot of important and interesting results (see, e.g., [8, 11] and references therein).

Henceforth, it would be natural trying to formulate dynamics of the non-diagonal Bianchi IX model in terms of the HN variables. However there is the key difficulty laying in the definition of those variables, formulated for diagonal metrics, in case of the general Bianchi IX spacetime described by the metrics (1). This metrics is generally non-diagonal globally, although it can be diagonalized at each separate moment of time. According to [5] the exact 3-dimensional metric \({\hat{\gamma }}\) is given by

where \({\hat{\Gamma }} = \text {diag} (\Gamma _1, \Gamma _2, \Gamma _3)\) and \({\hat{R}}\) is an orthogonal matrix (\({\hat{R}}^T = {\hat{R}}^{-1},\; \det {\hat{R}} = 1\)). The matrix \({\hat{R}}\) transforms the 3-dimensional metric tensor \(g_{\alpha \beta }\) to the principal axes and this rotation might be described in terms of Euler angles \((\theta , \varphi , \psi )\): rotation, precession and pure rotation. In other words \({\hat{R}}= {\hat{R}}_\theta {\hat{R}}_\varphi {\hat{R}}_\psi \), where \({\hat{R}}_\theta \), \({\hat{R}}_\varphi \) and \({\hat{R}}_\psi \) are standard rotation matrices.

In the general case, the Euler angles \((\theta , \varphi , \psi )\) are time dependent and describe the rotation with respect to the frame vectors \(e^a\), which are fixed. In the asymptotic regime the Euler angles become time independent, but \(\Gamma _\alpha \) stay being functions of time.

One can diagonalize the metric \({\hat{\gamma }}\) in the asymptotic regime by using \({\hat{R}}{\hat{\gamma }}{\hat{R}}^{-1} = {\hat{\Gamma }}\). Since \({\hat{R}}\) is time independent there, this diagonal form will exist until the gravitational system approaches the singularity. In this regime, the line element (1) can be presented as follows (see [1, 2] for more details)

where

and where C is a constant of motion. The metric (11) describes only the oscillatory modes devoid of the rotation. Since a, b and c satisfy Eqs. (2)–(3), derived from the exact system of equations with nondiagonal form of 3-metric, they have encoded nondiagonal aspects of the metric, and the line element:

may be interpreted as presenting an effective 3-metric. This identification suggests that we have a sort of an effective diagonal metric \(g_{\alpha \beta }\) near the cosmological singularity, i.e., in the asymptotic region of spacetime.

The effective 3-metric (13) is used below to introduce quasi-HN (qHN) variables. In this settings we define the new variables \((N_\alpha ,\Sigma _\alpha )\) as follows:

where \(V = 3/\frac{d}{d \tau }\ln (a b c)\), and where (a, b, c) satisfy Eqs. (2) and (3). Thus, \(\Sigma _1 + \Sigma _2 +\Sigma _3 = 0\) identically, and \(N_1> 0, N_2> 0, N_3 > 0\) as \(a b c \rightarrow 0\) near the singularity.

In what follows we will present similarities between the set of defined above variables and original HN ones.

The second fundamental form \(k_{\alpha \beta }\) associated with (13) is defined to be

where due to (4) we have

and where \(g:= \det g_{\alpha \beta }\), so v is the spatial volume density.

If we take \(k^\alpha _{~\beta } := g^{\alpha \gamma } k_{\gamma \beta }\), the trace of the matrix \(k_{\alpha \beta }\) reads

Defining the expansion \(\theta \) by

we get \(\theta := - \text {tr} (k)\). The volume changes according to \(d v/dt = \theta \, v \). Following the considerations in [11, 15], we define the Hubble variable

Thus the variables defined in Eqs. (14) and (15) coincide with Hubble normalized variables, namely:

where bared indices denote no summation convention, and \(\Sigma _1 + \Sigma _2 + \Sigma _3 = 0\) identically. We also have

directly corresponding to the definition (9) in our effective 3-metrics.

2.2 Dynamics

2.2.1 Finding the vector field

In what follows we derive the vector field corresponding to (2)–(3) entirely in terms of the qHN variables. Acting with \(d/d\tau \) on (14) and making use of (2) leads to the following set of equations

One can rewrite (15) as follows

where \(f := \pi _1 + \pi _2 + \pi _3\). Inserting (24) into (23) yields

Acting with \(d/d\tau \) on both sides of (24) and using (2) gives

Due to (B14), and \(\Sigma _1 + \Sigma _2 + \Sigma _3 =0\), we have

Inserting (29) into (25)–(28), we finally obtain the following vector field specifying the dynamics entirely in the qHN variables:

where \(\Sigma _1 + \Sigma _2 + \Sigma _3 = 0\). The variable \(\Pi \) has to satisfy the constraint (B23), which corresponds to the original constraint (3). Taking into account the constraint yields the system of equations:

where \(\Sigma :=-3+{\Sigma _1}^2+{\Sigma _1} {\Sigma _2}+{\Sigma _2}^2\).

2.2.2 Critical points of the dynamics

Direct inspection of the system (36)–(40) leads to the following identification of the set of the critical points:

in such a way that \(N_3 \ll N_2 \ll N_1\) and \(\sqrt{N_2/N_1} \ll N_1^2 \rightarrow 0\), and \(\sqrt{N_3/N_2} \ll \sqrt{N_2/N_1} \rightarrow 0\), which imply that

One can avoid taking the uncommon form of the limits (42) by introducing new variables, which we consider in “Appendix B”. However, this does not change the character of critical points. They stay to be the nonhyperbolic ones. A critical point is called a hyperbolic fixed point if all the eigenvalues of the Jacobian matrix of the linearized equations at this point have nonzero real parts. Otherwise, it is called a nonhyperbolic fixed point [14]. In the sequence we analyze the Jacobian for the above system and determine character of critical points.

2.2.3 The linearization of the vector field

One may verify, with some effort, that some elements of the Jacobian J of the system (36)–(40), evaluated at any point of \(S_{qHN}\), are diverging. This behavior comes from differentiating square roots. However, when calculating characteristic polynomial of the Jacobian J at any point those divergencies cancel out due to relations (42) giving

so the eigenvalues are \(\left( 0,0,0,0,0\right) \). Owing to very complicated form of the Jacobian matrix J and characteristic polynomial, we exhibit only the result after embedding conditions (42). Since the real parts of all eigenvalues of the Jacobian are equal to zero, we are dealing with the nonhyperbolic critical points.

Our system evolves asymptotically, as time goes to zero (when the system approaches the cosmological singularity), to the nonhyperbolic critical subspace with the coordinates \((\Sigma _1,\Sigma _2,N_1,N_2,N_3)\) given by

Further analysis should be based on making use of the exact form of our vector field.

3 The diagonal case

In what follows we demonstrate that the asymptotic forms of the dynamics of the non-diagonal and diagonal Bianchi IX model are quite different.

The dynamics of the diagonal Bianchi IX in asymptotic regime near the singularity may be obtained from the asymptotic dynamics of non-diagonal model with zero rotation of principal values \(\Gamma _a\) of the three-dimensional metric tensor \(\gamma _{ab}\) around frame vectors \(e^a\). It means that the Euler angles \((\theta ,\varphi ,\psi )\), describing the rotation with respect to the frame vectors are fixed

so they are no longer the degrees of freedom of the system. In that case the Einstein equations for the general Bianchi IX model in the vicinity of singularity derived in [5] take the following form:

where we assumed that the total angular momentum of the system vanishes, unlike in the general case, with rotation frozen near the singularity but with non-zero total angular momentum. The constraint equation, coming from the Bianchi identities, reads

For the comparison with (2)–(3), we rewrite (46)–(49) using the notation: \({\tilde{a}}:= \Gamma _1,~{\tilde{b}}:= \Gamma _2, {\tilde{c}}:= \Gamma _3\) , and get

with the dynamical constraint:

The dynamics of the diagonal and nondiagonal cases are quite different. Let us indicate just one aspect of this non-equivalence. Namely, it is clear that Eqs. (50)–(53) are symmetric with respect to the permutations:

whereas Eqs. (2)–(3) do not have the corresponding symmetry

The difference results from the fact that Eqs. (2)–(3) has been obtained by imposition onto the original set of equations defining the nondiagonal dynamics (see, Eqs. (2.14)–(2.20) in [5]) the condition

which implies Eq. (45).

3.1 Dynamical system analysis

Introducing the notation:

we rewrite the system (50)–(52) as follows

with the constraint corresponding to (53) in the form

It is easy to see that the critical points of the vector field (58)–(63), satisfying (64), are defined by

There are no strong relations among \(x_1,~x_2 \) and \(x_3\) in each of the above sets, contrary to the nondiagonal case (see the statement following Eq. (B9)).

One can solve the constraint equation (64) setting, e.g.

which turns the vector field (58)–(63) into

The above system has the same critical subspaces as the one without the constraint built into it. The Jacobian associated with the system (70)–(74) is found to be

The characteristic polynomial evaluated at the critical subspaces reads:

Hence, we can conclude that the character of the critical hypersurfaces (65)–(68) is the nonhyperbolic one.

3.2 Introducing the qHN variables

For the diagonal case we define the qHN variables \((M_\alpha ,\Omega _\alpha )\) a follows:

where \({\tilde{V}}:= 3/\frac{d}{d\tau } \ln ({\tilde{a}}{\tilde{b}}{\tilde{c}})\), and \(M_\alpha >0, \forall \alpha \), as near the singularity \({\tilde{a}}{\tilde{b}}{\tilde{c}}\rightarrow 0\).

Making use of (61)–(63) we can rewrite the constraint (64) in the form:

Using (77) and applying the analysis similar as in the nondiagonal case (B10)–(B14) we get:

where \(\Omega \in C^1({\mathbb {R}})\), and where \(\Omega _1 + \Omega _2 + \Omega _3 = 0\) due to (77).

Now, using (76) and (61)–(63) we arrive to the expressions:

Inserting (79)–(82) into (78) leads to the following expression for the constraint in terms of the qHN variables:

where \( \Omega _{123}:= 3 + \Omega _1 \Omega _2 + \Omega _1 \Omega _3 + \Omega _2 \Omega _3\) and \( M_{123}:= M_1 + M_2 + M_3 - 2(\sqrt{M_1 M_2} + \sqrt{M_1 M_3} + \sqrt{M_2 M_3}).\) Equation (83) has two solutions: \(\Omega = 0\), and \(\Omega = M_{123}/\Omega _{123}\).

3.3 The vector field

Acting with \(d/d \tau \) on (76) and (77), and using the expressions (79)–(82) leads, after some simple but lengthy rearrangements, to the following vector field:

where \(\Omega _0 = 0\) or \(\Omega _0 = 1/\Omega _{123}\), and the identity \(\Omega _1 + \Omega _2 +\Omega _3 = 0\) must be satisfied. Equations (87)–(89) fulfill this identically which shows self-consistence of the set (84)–(89).

3.4 Critical points

The critical points of the system (84)–(89), satisfying (83), define the set of critical hypersurfaces:

The Jacobian associated with the vector field (84)–89), satisfying (83), evaluated at any point of \(\{S_0,S_1,S_2,S_3\}\) has diverging components arising from differentiating terms of the type \(\sqrt{M_1 M_2}\) and in the limit \(M_1\mapsto 0\) (or other M’s going to zero). However, calculating characteristic polynomial and taking the value of its coefficient at the critical subspaces leads to the following result:

Hence, we can conclude that the character of the critical hypersurfaces (90)–(93) is the nonhyperbolic one.

4 Numerical simulations of the dynamics

In this section we present the numerical simulations of both evolutions, defined by Eqs. (2)–(3) and (50)–(53), to give support to some assumptions of the preceding sections. The numerical method we employed here is the same as described in [10]. Our simulations concern the dynamics with the initial data satisfying the strong inequality defined by Eq. (56). Since the product of the three scale factors is proportional to the volume density of the space, decreasing volume means evolution towards the singularity.

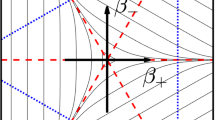

Figure 1a presents the plots of the directional scale factors corresponding to the dynamics of the nondiagonal case. Taking the initial data satisfying (56) leads to the evolution towards the singularity that maintains this strong inequality. This result gives support to the claim that this dynamics has the special asymptotic regime. Further support can be found in [10], where the simulations have been performed by using the exact dynamics of the general Bianchi IX model filled with a tilted pressureless fluid.

Figure 1b presents the evolution of the directional scale factors of the diagonal case with almost the same initial data as in the nondiagonal case.Footnote 1 No special regime occurs in this case. One can see the permutation symmetry of the relation (54) during the evolution of the system, contrary to the nondiagonal case. The permutation of the initial data leads to the same solutions (recoloring the plots), which is consistent with the permutation symmetry of the dynamics (50)–(53).

In fact, the permutation symmetry (54) was used to check the correctness of the numerical simulations.

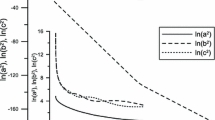

We were able to keep the numerical error in solving the Hamiltonian constraints, (3) or (53), as low as the order of \(10^{-16}\). This is illustrated in Fig. 2. Further increase of the precision of calculations keeps the plots unchanged.

5 Conclusions

Near the cosmological singularity, an evolution of the Bianchi IX model is an infinite sequence of the so called eras each of which consists of the Kasner type epochs [1]. In the diagonal case, each epoch can be described, e.g., by the relation \({\tilde{\Gamma }}_1 \sim {\tilde{\Gamma }}_2 > {\tilde{\Gamma }}_3\) (where \(\sim \) means coupled) called an oscillation.Footnote 2 The dynamics of the nondiagonal model has essentially different structure [4, 5]: the oscillation of the diagonal type, e.g., \(\Gamma _1 \sim \Gamma _2 > \Gamma _3\) enters sooner or later the relation \(\Gamma _1> \Gamma _2 > \Gamma _3\), which turns into the strong relation \(\Gamma _1 \gg \Gamma _2 \gg \Gamma _3\). Finally, the system approaches the singularity in a finite proper time.

The difference between the dynamics of the diagonal and nondiagonal cases leads to different topological structures of the corresponding sets of critical points. In the former case, this set consists of three hypersurfaces in \({{\bar{{\mathbb {R}}}}}^6\) having the same topology, Eqs. (91)–(93), and one set, Eq. (90), with the simple topology of \({{\bar{{\mathbb {R}}}}}^3\). In the latter case, the set of critical points has sophisticated topology, defined by Eq. (41), quite different from the diagonal case. Similar relationship occurs between the critical sets expressed in term of the BKL variables. However, in both cases the critical sets consist of the nonhyperbolic type of critical points.

The nonhyberbolicity is expected to be directly linked with the chaoticity of the dynamics of the Bianchi IX model. We conjecture that due to the different topologies of the critical spaces the chaoticity aspects of both cases can be different. Further studies are required to get insight into this intriguing issue.

Our main concern is the nonhyperbolicity of equilibrium points in both diagonal and general cases. They do not define a set of isolated points, but a three-dimensional continuous space. Thus, our choice of phase space variables seems to be unsatisfactory. We have already tried [6] to use the so-called blowing up technic initiated by McGehee [19] to avoid this obstacle, but with no success. More sophisticated approach based on \(\sigma \)-process of algebraic geometry proposed in [7] may bring some progress, but it leads to a noncanonical variables that we try to avoid. Another framework proposed for the spacially inhomogeneous models [12], within Hubble-normalized approach, can be probably specialized to the homogeneous models. However, this formulation is again a noncanonical one which we do not favour.

The way out seems to be giving up the insistence on dealing entirely with canonical formulations and planning making use of coherent states quantization methods (based on phase space structure of the underlying system) that we have recently applied to the diagonal Bianchi IX model [20, 21]. In such a case making use of the results of [12] to elucidate mathematical structure of the physical phase space specific to the dynamics of the Bianchi IX model (in both considered cases) would make sense. This is supposed to be the next step of our investigation and the results of the present paper could be used as a starting point. Another approach would be based on modification of the definition of the Hubble-normalized variables that we use in the present paper.

The fact that some critical points occur at infinity is not an obstacle. The mapping of the set of critical points onto the Poincaré sphere (considered, e.g., for the nondiagonal case, in “Appendix C”) des not change the type of the criticality. It stays to be of nonhyperbolic type. Thus, compactification of phase space does not help.

It seems that the nonhyperbolicity of the equilibrium points distributed in a continuous way in higher dimensional space is a generic feature of the dynamics of the Bianchi IX model and cannot be avoided. These properties may correspond to mathematical structure [13, 22] underlying chaotic behaviour of considered dynamics (see, e.g., [23, 24]), and needs to be further examined.

Data Availability Statement

This manuscript has no associated data or the data will not be deposited. [Authors’ comment: The article concerns entirely theoretical research.]

Notes

There can also occur small oscillations \({\tilde{\Gamma }}_1 \sim {\tilde{\Gamma }}_2 \gg {\tilde{\Gamma }}_3\), but they last for a finite interval of time and can be ignored.

References

V.A. Belinskii, I.M. Khalatnikov, E.M. Lifshitz, Oscillatory approach to a singular point in the relativistic cosmology. Adv. Phys. 19, 525 (1970)

V.A. Belinskii, I.M. Khalatnikov, E.M. Lifshitz, A general solution of the Einstein equations with a time singularity. Adv. Phys. 31, 639 (1982)

D. Garfinkle, Numerical simulations of generic singuarities. Phys. Rev. Lett. 93, 161101 (2004)

V.A. Belinski, On the cosmological singularity. Int. J. Mod. Phys. D 23, 1430016 (2014). arXiv:1404.3864 [gr-qc]

V.A. Belinskii, I.M. Khalatnikov, M.P. Ryan, The oscillatory regime near the singularity in Bianchi-type IX universes. Ann. Phys. 70, 301 (1971) [Preprint 469 (1971), Landau Institute for Theoretical Physics, Moscow (unpublished); published as Secs. 1 and 2 in M. P. Ryan]

E. Czuchry, W. Piechocki, Bianchi IX model: Reducing phase space. Phys. Rev. D 87, 084021 (2013). arXiv:1202.5448 [gr-qc]

O.I. Bogoyavlensky, Methods in the Qualitative Theory of Dynamical Systems in Astrophysics and Gas Dynamics (Springer, Berlin, 1985)

J.M. Heinzle, C. Uggla, Mixmaster: fact and belief. Class. Quant. Grav. 26, 075016 (2009). arXiv:0901.0776 [gr-qc]

O.I. Bogoyavlenskii, Some properties of the type IX cosmological model with moving matter. Sov. Phys. JETP 43, 187 (1976)

C. Kiefer, N. Kwidzinski, W. Piechocki, Dynamics of the general Bianchi IX spacetime near the singularity. arXiv:1807.06261 [gr-qc]

J.M. Heinzle, C. Uggla, A New proof of the Bianchi type IX attractor theorem. Class. Quant. Grav. 26, 075015 (2009). arXiv:0901.0806 [gr-qc]

C. Uggla, H. van Elst, J. Wainwright, G.F.R. Ellis, The Past attractor in inhomogeneous cosmology. Phys. Rev. D 68, 103502 (2003). arXiv:gr-qc/0304002

J. Wainwright, G.F.R. Ellis, Dynamical Systems in Cosmology (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1997)

S. Wiggins, Introduction to Applied Nonlinear Dynamical Systems and Chaos, 2nd edn. (Springer Science, New York, 2003)

G.F.R. Ellis, R. Maartens, M.A.H. MacCallum, Relativistic Cosmology (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2012)

N.J. Cornish, J.J. Levin, The Mixmaster universe is chaotic. Phys. Rev. Lett. 78, 998 (1997). arXiv:gr-qc/9605029

N.J. Cornish, J.J. Levin, The mixmaster universe: a chaotic farey tale. Phys. Rev. D 55, 7489 (1997). arXiv:gr-qc/9612066

V.A. Belinski, Private communication

R. McGehee, A stable manifold theorem for degenerate fixed points with application to celestial mechanics. J. Differ. Equations 14, 70 (1973)

H. Bergeron, E. Czuchry, J.P. Gazeau, P. Małkiewicz, W. Piechocki, Smooth quantum dynamics of the mixmaster universe. Phys. Rev. D 92, 061302 (2015)

H. Bergeron, E. Czuchry, J.P. Gazeau, P. Małkiewicz, W. Piechocki, Singularity avoidance in a quantum model of the Mixmaster universe. Phys. Rev. D 92, 124018 (2015)

B. Aulbach, Continuous and Discrete Dynamics near Manifolds of Equilibria (Springer, Berlin, 1984)

J.D. Barrow, Chaos in the Einstein equations. Phys. Rev. Lett. 46, 963 (1981)

J.D. Barrow, Chaotic behaviour in general relativity. Phys. Rep. 85, 1 (1982)

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Claes Uggla for the suggestion to use the Hubble normalized variables and to Juliette Hell for valuable discussions concerning the dynamics of the Bianchi IX model. Finally, we appreciate inspiring discussions with Vladimir Belinski. This work was partially supported by the German-Polish bilateral project DAAD and MNiSW, No 57391638, “Model of stellar collapse towards a singularity and its quantization”.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix A: Quotient coordinates

In order to avoid defining critical surface in term of the limits \(\sqrt{N_3/N_2} \ll \sqrt{N_2/N_1} \ll N_1^2 \rightarrow 0\), one can introduce quotient coordinates:

Then the system of equations (36)–(40) takes the following form:

where \(\Sigma _0=15 {\Sigma _1}+4 {\Sigma _1}^2-3 {\Sigma _2}+4 {\Sigma _1} {\Sigma _2}+ 4 {\Sigma _2}^2\) and \(\Sigma = -3+{\Sigma _1}^2+ {\Sigma _1} {\Sigma _2}+{\Sigma _2}^2\). The left hand sides of Eqs. (A3)–(A4) vanish for \(N_1=0=u=v\).

The set of critical points of the vector field (A3)–(A7) is easily found to be

The characteristic polynomial is \(P(\lambda )=-\lambda ^5\). Thus, the character of corresponding critical surface is nonhyperbolic.

One may speculate that \({\tilde{S}}_{qHN}\) corresponds to \(S_0\) of Eq. (90) so the underlying dynamics of corresponding vector fields have some common feature. One may further speculate that both \(S_0\) of Eqs. (90) and (A8) correspond to some new form of chaoticity, whereas (91)–(93) are specific to the well known attractor of the diagonal case.

Appendix B: Relationship between old and new variables

Let us rewrite Eqs. (2) as follows

where \(q_1 := \ln a,\; q_2 := \ln b,\; q_3 := \ln c, \; \pi _1 := {\dot{q}}_1,\;\pi _2 := {\dot{q}}_2,\;\pi _3 := {\dot{q}}_3 \) are new variables. Thus, the constraint (3) reads

Making use of (B1)–(B6) one can present (B7) in the form

One can easily verify that the critical points of the dynamical system (B1)–(B7) are of the nonhyperbolic type and coincide with the set of critical points \(S_B\) determined in [6]. Thus, the set of critical points \(S_B\) (in terms of \(q_\alpha \) and \(\pi _\alpha \) variables) is given by

where \({\bar{{\mathbb {R}}}}:= {\mathbb {R}}\cup \{-\infty , +\infty \}\). The infinities in (B9) should be approached in such a way that \(q_1 \gg q_2 \gg q_3\), which corresponds to \(a \gg b \gg c \) found in [5].

Now, we rewrite the vector field (B1)–(B7) in terms of the qHN variables \(N_\alpha \) and \(\Sigma _\alpha \). Using (15) we get

Equation (B10) can be presented in a matrix form as follows

One may verify that the determinant of the \(3 \times 3\) matrix A of the above equation reads: \(det(A) = 9 \,(\Sigma _1 + \Sigma _2 + \Sigma _3) = 0\), since \(\Sigma _1 + \Sigma _2 + \Sigma _3 =0\). Thus, rank of \(A <3\). One may easily check that all minors (\(M_k,~k=1,2,3\)) of the \(2 \times 2\) submatrixes of the matrix A are of the form \(M_k =\pm 3 (1+\Sigma _k)\). Since we cannot have \(1+\Sigma _k =0, \forall k \) due to \(\Sigma _1 + \Sigma _2 + \Sigma _3 =0\), the rank of the A matrix equals 2. Suppose we choose

to play the role of a nonsingular submatrix of A. Since \(det B = 3(1+ \Sigma _3)\), the rank of B equals 2 if we have

Using Cramer’s rules we find the following solution to (B11):

where we have redefined an arbitrary variable \( \pi _3 = \Pi \in C^1({\mathbb {R}})\) by taking \(\pi _3=\Pi (1+\Sigma _3)\), which is allowed as \((1+\Sigma _3)\ne 0\). It is clear that one can get the solution (B14) assuming that either \(1+ \Sigma _1 \ne 0\) or \(1+ \Sigma _2 \ne 0\), instead of (B13). Therefore, our solution (B14) is independent on the choice of the minor \(M_k\) connected with the matrix A of (B11). We conclude that the general solution to the matrix equation (B11) is defined by (B14).

Using (14) we obtain

that leads to

Comparing (B16) with (B17), and using the solution (B14), we get

Which can be presented in a matrix form as follows:

One may easily verify that determinant of the matrix defining (B21) equals one, so the system has only one solution. It is found to be:

where \({\tilde{\Pi }} :=\Pi N_1\).

An arbitrary variable \(\Pi \) that occurs in (B14) and (B22) can be fixed by the constraint (B8). It leads to the following equation for \(\Pi \):

where \(\Sigma _1 + \Sigma _2 + \Sigma _3 = 0\).

Appendix C: The Poincaré type variables

Since examination of phase space at ‘infinite region’, (B9), is difficult mathematically, we change coordinates of the phase space to map the set of critical points (B9) onto a finite region. We map the infinite space \({\bar{{\mathbb {R}}}}^6\) into a finite Poincaré sphere, parameterized by Cartesian coordinates \((X_1,X_2,X_3,P_1,P_2,P_3)\), as follows:

where \(r^2=X_1^2 + X_2^2 +X_3^2+ P_1^2 + P_2^2 + P_3^2 \), and where we redefined the variables: \(x_k := q_k, p_k := \pi _k ~~(k = 1,2,3) \) to get the connection with the results of our previous paper (see, Eq. (38) of [6]). We also rescale the time parameter \(\tau \) by defining the new time parameter T such that \(d{T} := d\tau /(1-r)\). In these coordinates our phase space is contained within a sphere of radius one – ‘infinities’ correspond to \(r=1\).

If the mapping is canonical, we should have:

The map (C1)–(C6) is not canonical, because we have:

where \(a:= r^2/ (1-r)^2,~f(a)\ne 0,~g(a)\ne 0 \). It is clear that there is no chance to get (C7) for any r including the limit \(r\rightarrow 1\).

The insertion of (C1)–(C6) into (B1)–(B6) gives:

where prime denotes derivative with respect to the new time parameter T.

To find the fixed points we insert \({X}_1' =0={X}_2' = {X}_3' = {P}_1' ={P}_2' = {P}_3'\) into (C11)–(C16) by using the elementary formulas:

and, e.g.

After rearrangement of terms we finally get:

The solution to (C19)–(C21) reads: \(P_1 = 0 = P_2 = P_3\). The equations (C22)–(C24) can be satisfied in the limit \(r\mapsto 1\) if

which leads to the condition: \(X_3< X_2< X_1 < 0.\) Therefore, the critical subspace is defined to be:

It is not difficult to verify that the transformation (C1)–(C6) does not map \(S_B\) into \(S_P\).

It is clear that any point of \(S_P\), in the limit \(r\rightarrow 1^-\), satisfies the constraint (B7) which in the variables (C1)–(C6) has the form:

One can resolve (either manually or by symbolic computations) the nonlinear vector field (C11)–(C16) with respect to the derivatives \(\;X_1', X_2',\ldots , P_3'\), and find the corresponding Jacobian. Its value at any point of the subspace \(S_P\) (in the limit \(r\mapsto 1\)) turns out to be a six dimensional zero matrix. It means that linearization of the exact vector field, at the set of critical points \(S_P\), cannot help in the understanding of the mathematical structure of the space of orbits of considered vector field. An examination of the nonlinearity cannot be avoided. One may say, formally, that the set \(S_P\) consists of the nonhyperbolic type of fixed points.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Funded by SCOAP3

About this article

Cite this article

Czuchry, E., Kwidzinski, N. & Piechocki, W. Comparing the dynamics of diagonal and general Bianchi IX spacetime. Eur. Phys. J. C 79, 173 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1140/epjc/s10052-019-6690-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1140/epjc/s10052-019-6690-y