Abstract

We propose an uni-parametric deformation method of action principles of scalar fields coupled to gravity which generates new models with massive stealth field configurations, i.e. with vanishing energy-momentum tensor. The method applies to a wide class of models and we provide three examples. In particular we observe that in the case of the standard massive scalar action principle, the respective deformed action contains the stealth configurations and it preserves the massive ones of the undeformed model. We also observe that, in this latter example, the effect of the energy-momentum tensor of the massive (non-stealth) field can be amplified or damped by the deformation parameter, alternatively the mass of the stealth field.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

It is generally believed that matter curves the space, a consequence of the interpretation of the equations of gravity-matter systems, which tells that the energy- momentum tensor of matter fields feedback the curvature of the geometry equations. However, it seems mathematically possible the existence of non-trivial matter-field configurations with vanishing energy- momentum tensor, such that the first statement will not be always truth. Indeed, there are examples of systems where this happens. In the references [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9] the authors impose separately the vanishing Einstein tensor equation, the vanishing energy- momentum tensor equation (obtained from some scalar theory), and the matter-field equations of motion. If these three sets of equations are satisfied the scalar field would exist but it will not be detected by the background geometry, since it will not deform it. This is what a “stealth field” means. It is worth to mention that stealth solutions appeared also in the references [10,11,12,13], and that an analogous result, for a Dirac fermion field was found in [14]. Though this behavior of matter may seem strange, the mathematical possibility on the existence of stealth fields encourage their study. The non-trivial effect of matter on the gravitational background is also suggested by the observation on galaxies, which have led to the conjecture on the existence of “dark matter”.

The purpose of this paper is to present a method to construct models with massive stealth fields. This is, the method takes a given (original) action-principle and produces a related (deformed) one which contains massive stealth configurations. Just one restriction on the original action principle is needed, that the trivial vacuum (with vanishing VEV) must exist. We shall provide three non-trivial examples of application of our method. Advancing one interesting result, we shall observe that stealth field mass produces a re-scaling of the the energy-momentum tensor of a (non-stealth) massive configuration. Hence the stealth field, though undetectable by the background space-time geometry, can amplify (or reduce) the gravitational effect of regular matter fields, which may be interesting from a cosmological point of view.

This paper is organized as follow. In Sect. 1 we introduce the notation and define what a stealth field is. In Sect. 2 we define the deformation of the action principle and obtain the respective equations of motion, as deformations of the original equations of motion. We prove that the deformed theories contain massive fields with mass inversely proportional to the deformation parameter. This is done on full generality, without reference to any particular model. In Sect. 3 we construct some examples and characterize their solutions, and in Sect. 4 we present some conclusions.

1 Stealth scalar field definition

In generic space-time background metric \(g_{\mu \nu }\), \(\mu =0,...,D-1\), with diagonal components signature \((-,+,+,...)\), consider the gravity-matter system,

where \( S_{G}[g]\) is the gravitational action principle for a given theory of gravity (e.g. general relativity or modified models) and \(S_M[g,\phi ]\) is the action principle for a scalar matter field \(\phi \) coupled to the \(g_{\mu \nu }\).

The variation with respect to the (inverse) metric tensor \(g^{\mu \nu }\) yields,

where

are respectively the generalized Einstein tensor, \( H_{\mu \nu }[g]\), and the Hilbert energy-momentum tensor, \({\varXi }_{\mu \nu }[g,\phi ]\), up to constant coefficients.

From the variation of the action with respect to the scalar fields \(\phi \) we define,

which represents a differential operator acting on the field \(\phi \). In what follows, for functionals F[f] of a function f(x) valued in the point x, we shall declare the dependence on this point as F[f](x), whenever is necessary, as in e.g. \({\delta }/{\delta g^{\mu \nu }(x)}\), \({\delta }/{\delta \phi (x)}\), \(H_{\mu \nu }[g](x)\), \({\varXi }_{\mu \nu }[g](x)\).

The equations of motion of the theory (1) are given by,

respectively for the variation of the metric and the matter field, and for a non-degenerated metric tensor \(\sqrt{-g}\ne 0\).

By definition, a stealth scalar field is a non trivial field which satisfies the equations of motion and its energy-momentum tensor vanishes, respectively,

As consequence of (5), the generalized Einstein tensor must also vanish,

so that in presence of a stealth \(\phi \) the metric tensor must satisfy identical equations of motion than in the vacuum \(\phi =0\). The stealth scalar field does not feedback the metric background.

2 \(\theta \)-deformation of scalar field theories

The idea to be developed here can be spelled as follows. Given an action principle with a saddle point with vanishing expectation value of a scalar field (trivial vacua) we can construct a new (deformed-) one, with saddle points at the trivial and at a massive configurations. As a consequence of the construction, the deformed action principle, which is an extension of the original one, will have also vanishing energy momentum tensor. Surprisingly enough, the details of the original theory are not important, so that we can construct full class of models sharing these features.

Let us illustrate this with a simple example. Let f(x) be any function of \(x\;\in \;\mathbb {R}\) with a saddle point at \(x=0\),

and let y(x) another function which possess, for definiteness, two zeros at \(x=0\) and \(x=1\),

We define the composition of functions \(F(x):=f(y(x))\), which inherits from the parent functions f and y the properties,

such that it has two saddle points, at \(x=0,1\). It is straightforward to prove this. We can use the chain rule to evaluate dF / dx at \(x=0,1\),

Here the \(df(y)/dy|_{y=0}\) vanishes because from (9) y takes zero-value and from (8) the derivative of f vanishes when the argument is zero. Hence from an arbitrary function f(x) with saddle point at \(x=0\) (8) we can construct another arbitrary function F(x) with saddle points at the kernel of the map \(y:\mathbb {R}\rightarrow \mathbb {R}\), in this example \(x=0,1\).

We can promote the latter statements to functionals, i.e. to action principles and the solutions of the equations of motion. f is the analogous of an action principle for a scalar field represented by the variable x, of which \(x=0\) represents its trivial vacua and \(x=1\) will represent a non-trivial (massive) configuration. F is the analogous of a new action constructed from a transformed scalar field, y(x), i.e. which is a map from x to y in the class of differentiable functions. Now if \(x=0\) is a saddle point of the action f, then the new action principle F must have saddle points at the trivial vacuum (\(x=0\)) and at the non-trivial configuration (represented by \(x=1\)). Note that F(x) takes the same values at \(x=0\) and \(x=1\) since \(F(1)=F(0)=f(0)\). Hence both configurations, trivial and non-trivial, are at the same foot.

Now let us introduce a second variable, g, such that now \(y=y(x,g)\) is two-parametric and, consequently \(F:=f(y(x,g))\) is also two-parametric. We can easily prove that,

since \({\partial f(y(x,g))}/{\partial y}|_{y=0}=0\) whenever (8) and \(y(x,g)|_{y=0}=0\) (in correspondence with (9)) hold. Hence, the functional \(F:=f(y(x,g))\) has saddle points at \({x=0,1}\), no matter what the value of g is. Continuing our analogy, g will represent a metric tensor, and the implication of (11) is that the energy momentum tensor provided by the new action principle will vanish for either configuration.

We shall apply now the same logic in the language of functional calculus in order to construct new classes of (generic) action principles which have saddle points at massive configurations and which are also stealth.

The field transformation to be considered is:

where \(\theta \) is a real-valued parameter and

is the Laplace-Beltrami operator acting upon \(\phi \). The kernel of the deformation map (12) is degenerated, consisting of the trivial vacuum \(\phi =0\) and the massive configuration \(\phi =\phi _m\) with mass \(m=\theta ^{-1}\). Indeed,

is equivalent to the Klein–Gordon equation in curved space. (12) is a map between the class of differentiable functions in \(\mathbb {R}^D\) (the analogous of y(x, g)) which will be used to map a generic action principle of a scalar field into a new action principle with saddle points at \(\phi =0,\phi _m\). The latter will posses vanishing energy momentum tensor. Though we shall prove this in full generality, for the convenience of the reader, we shall advance here one example.

2.1 Quick example

In order to illustrate the non-trivial effects of the deformation map (12) let us construct the simplest example we can imagine, the deformation of the “mass term” action,

where M is the mass-coupling constant. The equation of motion for the scalar field is,

Hence (14) has a saddle point at \(\phi =0.\) Now let us construct the deformed action,

where we replaced the original field \(\phi \) by \(\phi ^\theta \). This action can be regarded as a degenerated (single-parameter) case of the two-parametric fourth-order action principle analyzed in [15]. The equation of motion for \(\phi \) yields,

It is clear from (17) that the equation of motion is satisfied by the solutions of the Klein–Gordon equation (13). Now let us verify that the gravitational energy-momentum tensor vanishes. A direct calculation of the energy momentum tensor produces,

which is evidently zero for the massive \(\phi =\phi _m\). Hence, in spite of it mass the configuration \(\phi _m\) possesses a trivial energy momentum tensor. We shall stress here the non-triviality of the action (16) no-matter of what its origin was, and that we derived the equation of motion and the energy momentum tensor in a standard way. The reader may also wish to give a quick look to two more examples in Sect. 3.

2.2 General models with stealth configurations

In this subsection we shall prove that the results of the example (2.1) can be extended to a wide class of action principles, i.e. which will possess solutions of the equations of motion with non-trivial mass and with vanishing energy momentum tensor.

We define the matter field \(\theta \)-deformed action principle,

consisting on the replacement of \(\phi \) by \(\phi ^\theta \) (12). The deformation of the gravity plus matter field is defined similarly,

Note that the pure gravity sector \(S_{G}[g]\) is not affected by the deformation, and that the deformed action will be of higher order in derivatives with respect to the original action.

Let us assume that the minimal degree of the matter field action as a functional of \(\phi \) is \(> 1\), such that the respective equations of motion admit the vacuum solution \(\phi =0\) and \(S_M[g,0]=0\). This implies that \(S_M[g,\phi ^\theta =0]=0\) also vanishes for both, trivial \(\phi =0\) and for the massive configuration of mass \(\theta ^{-1}\),

i.e. for solutions of (13).

Morally speaking, this means that the massive stealth field \(\phi =\phi _{m}\) (13) and the vacuum \(\phi =0\) are at the same foot.

The equations of motion of deformed theory are given by:

which yield respectively,

where \(H_{\mu \nu } [g]\) was defined in (3) and

Note that in (23) the generalized Einstein tensor \(H_{\mu \nu } [g]\) remains undeformed, since the field transformation (12) does not affect the metric tensor.

2.3 Variation of the action with respect to \(\phi \)

The variation with respect to \(\phi \) should be carried out taking into account that the action depends on \(\phi \) implicitly by means of \(\phi ^\theta [g,\phi ]\), so that we should consider the chain rule for functional derivation (see e.g. Appendix A in [16]). Indeed, given two functionals F[f] and G[f], and its composition F[G[f]], the generalized chain rule reads,

Applying this in the computation of (25), in the point y, we obtain the variation of the deformed action,

where we have used the definition (19) in r.h.s. The latter expression is equivalent to,

where,

and it is understood that

and therefore equivalent to the original operator (4) valued in \(\phi ^{\theta }[g,\phi ]\).

Replacing,

in (28), integrating by parts and adopting the notation (25), we finally obtain the equation of motion for the matter field of the deformed system (23),

2.4 Variation of the action with respect to \(g^{\mu \nu }\)

Let \(\mathcal {L}_M[g,\phi ]\) the Lagrangian density, such that,

In correspondence with the substitution (19), the \(\theta \)-deformed action principle is given by

Considering again the functional chain rule (26), and that the deformed action functional (34) depends on \(g^{\mu \nu }\) explicitly and also implicitly, by means of the functional \(\phi ^\theta =\phi ^\theta [g,\phi ]\), we obtain that the variation of the deformed action principle (19) is equivalent to,

Here, the first term on the r.h.s. corresponds to the variation with respect to the explicit dependence of the action, while the second encodes its implicit dependence. Alternatively, (35) can be written also as,

where we have defined

and considered (3), and (29)–(30). From (36) and (24), the energy-momentum tensor provided by the deformed matter action is given by,

To complete the calculation, we need to replace the functional

in (37), which after integration by parts yields,

2.5 Stealth theorem

Let us prove now that the massive field \(\phi =\phi _m\) (13) is a stealth field. The core of the proof is based in the fact that for this configuration \(\phi ^{\theta }[g,\phi _m]=0\). Let us replace \(\phi _m\) in the equations of motion of the deformed theory (23),

in an arbitrary background metric tensor \(g_{\mu \nu }\). The second equation is equivalent to,

As we have argued, if the original theory (5) admits a vacuum solution \(\phi =0\), then \({\varUpsilon }[g,0]=0\), which implies (40). Now, let us evaluate the energy-momentum tensor in \(\phi =\phi _m\), or equivalent in \(\phi ^\theta =0\),

Again, since \({\varUpsilon }[g,0]=0\), the second and third term on the r.h.s. vanish, while the first term \({\varXi }_{\mu \nu }[g,0]=0\) must also vanish as we argued that the vacuum solution \(\phi =0\) of the original theory must exist and it has to have, naturally, a vanishing energy-momentum tensor. Hence, the equations of motion (39) are reduced to

which corresponds to the equation of motion of the pure gravity theory given by \(S_G[g]\). Hence, \(\phi _m\) is stealth, since in its presence the gravity background must satisfy identical equations than in the vacuum \(\phi =0\).

3 Examples

Here we shall present two more examples. The reader may analyze these cases in independence of the general results of Sect. 2.

3.1 Deformation of the massless field action

Consider now the action of a massless scalar field,

whose equation of motion for \(\phi \) is,

According to the deformation recipe, the deformed action is given now by,

A direct calculation of the equation of motion for \(\phi \) yields,

which turns out to have the general form (32). As it can be seen in the line (44), the equation of motion is satisfied by the solutions of the Klein–Gordon equation (13).

Now let us obtain the gravitational energy-momentum tensor directly from the action (43),

Again, the energy-momentum tensor vanishes for the solutions of the Klein–Gordon equation (13). The action (43) describes massive stealth configurations of mass \(m=\theta ^{-1}\), among others non-stealth configurations. On the one hand, the original matter field equation (42) admits massless solutions, including the trivial one \(\phi =0\). On the other hand, the \(\theta \)-deformed system admits a extension of original space of solutions with stealth fields. Indeed, from the Eq. (44), written also as,

we find that the solutions are given by the trivial one, \(\phi =0\), the massless one, \(\Box \phi =0\), and the double-degeneracy massive stealth \(\phi =\phi _m\). Let us evaluate the massless solutions in the energy-momentum tensor (45). We obtain,

i.e., the deformed energy-momentum takes the same value than the undeformed energy-momentum tensor. Therefore, the space of solutions of the gravitational sector remains invariant with respect to the original theory (41). This means that, in terms of gravity effects, after deformation the stealth field yields the same results than the trivial matter vacuum, while for the massless configurations the geometry is sourced by the same energy-momentum tensor than in the original theory.

3.2 Deformation of the massive field action

In the case of the scalar field \(\phi \), with mass M the matter action principle is given by,

which corresponds to the sum of the massless field action (41) with the square potential action (14), and whose equation of motion for \(\phi \) is proportional to the Klein–Gordon equation,

Following the \(\theta \)-deformation recipe of the action (48), which produces a linear combination of (16) and (43), we obtain the equation of motion,

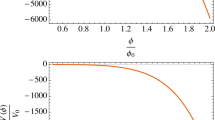

which has the general form (32), as expected. As for the energy momentum-tensor, the \(\theta \)-deformed action yields again a linear combination of (18) and (45), i.e. respectively

where \(\phi ^\theta :=(1-\theta ^2\Box )\phi \) as it has been already defined in (12). Among the solutions of the equation of motion (50), we have \(\phi =\phi _m\) of mass \(m=\theta ^{-1}\), which are the stealth solutions. The other massive solutions, say \(\phi =\phi _M\), which satisfy

have mass M. As we observe, the massive solutions of the undeformed theory remain after the deformation.

Now we analyze the energy-momentum tensor for these fields. First we replace \(\phi _M\) in the definition of \(\phi ^\theta \) which yields to,

so that their energy-momentum tensor (51) is given by,

which means that the energy-momentum tensor of the original gravity-matter system is rescaled by factor \(\lambda ^2\) in the deformed theory.

Hence, the space of solutions for the scalar field in the undeformed theory consist of the trivial solution \(\phi =0\) and the massive solution \(\phi _M\). In the deformed theory this space is extended by the massive stealth fields \(\phi _m\). The energy-momentum tensor (54) vanishes for the trivial solution and for the massive stealth fields but for the solutions \(\phi =\phi _M\) the deformed theory yields a rescaled energy-momentum tensor. Note that this can be interpreted also as a rescaling of the Newton coupling constant by a factor, \(G_\texttt {N}\rightarrow \lambda ^2 G_\texttt {N}\), in the standard nomenclature. Hence, the mass of the stealth field (equivalently the deformation parameter) can be used to smooth or amplify the effects of the massive field of mass M on the gravitational background.

4 Overview and remarks

In this paper we show that for a wide class of scalar field action principles in curved space we can construct a deformation which admits massive stealth configurations. The theory here presented consists of a method for the construction of action principles which insures the existence of massive stealth fields, independently of the solutions of the gravity field equations. In the proof, we just need to assume that the Klein–Gordon equation admits non-trivial solutions.

As for new developments, it would be interesting to extend our construction to gauge theories. For example, one possible way is to couple the scalar fields to (non-)abelian gauge fields, in a curved background, and use the correspondent generalization of the field transformation (12) to obtain stealth solutions with non-trivial gauge charges. Also, in a similar spirit but in absence of scalar fields, we can consider redefinitions of gauge fields to produce deformation of gauge theories with non-trivial propagating degrees of freedom, in spite of which they will not feedback the gravitational background. Indeed, non-linear electrodynamics can produce stealth configurations [8]. In this direction, an example was found in \(2+1\) dimensions [17], where it was shown that the correspondent (deformed) gauge theory contains self-dual fields in \(2+1\) dimensions [18] which are stealth. It is worth mentioning that further analogies between stealth matter sources and self-duality can be found in [19].

As for the stability of stealth fields, in our framework, since they do not depend on any specific background, they must be robust under background perturbations, so we expect they must be stable. This should be corroborated by means of the appropriated methods (see e.g. [20]).

Let us comment that though stealth fields do not curve space, they may give rise to new cosmological effects, for example by means of the energy-momentum tensor rescaling of regular matter fields, which depends on the stealth field mass parameter observed in (54). It would be interesting to check whether this may help with the cosmological constant problem or the amplification of the gravitational effects of the visible matter in galaxies. See e.g. [21, 22] for other possible cosmological implications of stealth fields.

Finally, as the reader must have noticed, the theories obtained by means of our method are in general of higher order (see examples (16) and (43)). The consistency of these theories in the quantum level requires the analysis of specific models in deeper detail, using similar techniques than in [15, 23, 24] and reference therein. This problem should be studied elsewhere.

References

E. Ayon-Beato, C. Martinez, J. Zanelli, Stealth scalar field overflying a (2+1) black hole. Gen. Relativ. Gravity 38, 145–152 (2006)

E. Ayon-Beato, C. Martinez, R. Troncoso, J. Zanelli, Gravitational Cheshire effect: Nonminimally coupled scalar fields may not curve spacetime. Phys. Rev. D 71, 104037 (2005)

E. Ayón-Beato, P.I. Ramírez-Baca, C.A. Terrero-Escalante, Cosmological stealths with nonconformal couplings. Phys. Rev. D 97(4), 043505 (2018)

E. Ayón-Beato, A.A. García, P.I. Ramírez-Baca, C.A. Terrero-Escalante, Conformal stealth for any standard cosmology. Phys. Rev. D 88(6), 063523 (2013)

M. Hassaine, Rotating AdS black hole stealth solution in D=3 dimensions. Phys. Rev. D 89(4), 044009 (2014)

E. Ayón-Beato, M. Hassaïne, M.M. Juárez-Aubry, Stealths on anisotropic holographic backgrounds (2015). arXiv:1506.03545 [gr-qc]

A. Alvarez, C. Campuzano, M. Cruz, E. Rojas, J. Saavedra, Stealths on \((1+1)\)-dimensional dilatonic gravity. Gen. Relativ. Gravity 48(12), 165 (2016)

I. Smolić, Spacetimes dressed with stealth electromagnetic fields. Phys. Rev. D 97(8), 084041 (2018)

A. Alvarez, C. Campuzano, E. Rojas, J. Saavedra, Gravitational stealths on dilatonic (1 + 1)-D black hole. In Proceedings, 14th Marcel Grossmann Meeting on Recent Developments in Theoretical and Experimental General Relativity, Astrophysics, and Relativistic Field Theories (MG14) (in 4 volumes), vol. 3 (Rome, 2015), pp. 2723-2726 (2017)

E. Ayon-Beato, A. Garcia, A. Macias, J.M. Perez-Sanchez, Note on scalar fields nonminimally coupled to (2+1) gravity. Phys. Lett. B 495, 164 (2000). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0370-2693(00)01241-7. arXiv:gr-qc/0101079

M. Henneaux, C. Martinez, R. Troncoso, J. Zanelli, Black holes and asymptotics of 2+1 gravity coupled to a scalar field. Phys. Rev. D 65, 104007 (2002). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevD.65.104007. arXiv:hep-th/0201170

J. Gegenberg, C. Martinez, R. Troncoso, A Finite action for three-dimensional gravity with a minimally coupled scalar field. Phys. Rev. D 67, 084007 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevD.67.084007. arXiv:hep-th/0301190

C. Martinez, J.P. Staforelli, R. Troncoso, Topological black holes dressed with a conformally coupled scalar field and electric charge. Phys. Rev. D 74, 044028 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevD.74.044028. arXiv:hep-th/0512022

A. Dimakis, F. Mueller-Hoissen, Solutions of the Einstein–Cartan–Dirac equations with vanishing energy momentum tensor. J. Math. Phys. 26, 1040 (1985). https://doi.org/10.1063/1.526535

S.W. Hawking, T. Hertog, Living with ghosts. Phys. Rev. D 65, 103515 (2002). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevD.65.103515. arXiv:hep-th/0107088

R.M. Dreizler, E. Engel, Density Functional Theory: An Advanced Course (Springer, New York, 2011)

J. Oliva, M. Valenzuela, Topological self-dual vacua of deformed gauge theories. JHEP 09, 152 (2014)

P.K. Townsend, K. Pilch, P. van Nieuwenhuizen, Selfduality in odd dimensions. Phys. Lett. 136B, 38 (1984) [ Addendum: Phys. Lett. 137B, 443 (1984)]

M. Hassaine, Analogies between self-duality and stealth matter source. J. Phys. A 39, 8675–8680 (2006)

V. Faraoni, A.F.Z. Moreno, Are stealth scalar fields stable? Phys. Rev. D 81, 124050 (2010)

H. Maeda, K. Maeda, Creation of the universe with a stealth scalar field. Phys. Rev. D 86, 124045 (2012)

C. Campuzano, V.H. Cárdenas, R. Herrera, Mimicking the LCDM model with Stealths. Eur. Phys. J. C 76(12), 698 (2016)

F.J. de Urries, J. Julve, Ostrogradski formalism for higher derivative scalar field theories. J. Phys. A 31, 6949 (1998). https://doi.org/10.1088/0305-4470/31/33/006. arXiv:hep-th/9802115

C.M. Bender, P.D. Mannheim, No-ghost theorem for the fourth-order derivative Pais-Uhlenbeck oscillator model. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 110402 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.100.110402. arXiv:0706.0207 [hep-th]

Acknowledgements

We thank Eloy Ayón-Beato and Julio Oliva for valuable discussions. A.S. thanks the FAPEMAT postdoc grant Edital 039/2016. We thank the support of Facultad de Ingeniería y Tecnología USS for its “Núcleo de Física Teórica” initiative which facilitated the production of this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Funded by SCOAP3

About this article

Cite this article

Quinzacara, C., Meza, P., Sampson, A. et al. Massive stealth scalar fields from deformation method. Eur. Phys. J. C 78, 950 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1140/epjc/s10052-018-6441-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1140/epjc/s10052-018-6441-5