Abstract

We study physical processes around a rotating black hole in pure Gauss–Bonnet (GB) gravity. In pure GB gravity, the gravitational potential has a slower fall-off as compared to the corresponding Einstein potential in the same dimension. It is therefore expected that the energetics of a pure GB black hole would be weaker, and our analysis bears out that the efficiency of energy extraction by the Penroseprocess is increased to 25.8 % and the particle acceleration is increased to 55.28 %; the optical shadow of the black hole is decreased. These are in principle distinguishing observable features of a pure GB black hole.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

From all generalizations of Einstein gravity what distinguishes the Lovelock gravity is its remarkable property that the equation of motion always remains second order. This happens despite the Lagrangian being polynomial in the Riemann curvature. It is the underlying differential geometric structure that is responsible for this unique remarkable property, discovered by Lovelock [1]. The Lovelock action S, which is a homogeneous polynomial of degree N in Riemann curvature, reads

where the Lagrangian is given by

and \(\lambda _{N}\) are coupling constants.

In this action \(N = 0, 1, 2,\ldots \), respectively, correspond to \(\lambda _{N}\), the usual cases of Einstein–Hilbert, Gauss–Bonnet, and so on. However, higher order Lovelock terms in the action make a non-zero contribution only in dimensions \(D>4\). That is, Lovelock is the natural higher dimensional generalization of Einstein gravity.

It is well known that particle physics theories, in particular string theory, call for higher dimensions as demanded by physical symmetries. Besides, one of us had also articulated some purely classical considerations for higher dimensions [2–4]. One of the most convincing arguments goes as follows [4]. It is customary to consider high energy effects of a theory by taking a higher power of the basic variable. In the case of gravity, the basic physical entity is the Riemann curvature, and hence, to take into account high energy effects, we should include higher powers of it in the action. However, if we demand that the equation of motion should not change its second order character, then we are uniquely led to the Lovelock action, which is pertinent only in higher dimensions. That is, high energy effects of gravity are accessible only in higher dimensions. Thus it makes a good case for studying gravity in higher dimensions.

Note that in the above action there is a sum over N and each term has a dimensionful coupling constant which cannot be determined because experiment can determine only one constant. To make the problem tractable, it was assumed, for obtaining dimensionally continued black holes [5], that all the couplings were given in terms of the unique ground state \(\lambda _{N}\). On the other hand, there is a strong case for pure Lovelock gravity [6, 7] where there is only one Nth order term in the action with \(\lambda _{N}\). That is, it does not include even the usual Einstein–Hilbert term. This has the remarkable unique property that gravitational dynamics is distinguished in all odd and even dimensions [7]. In all odd \(D=2N+1\) dimensions, gravity is kinematic meaning the Nth order Lovelock analog Riemann tensor vanishes whenever the corresponding Ricci tensor vanishes [8]. This of course includes the usual 3 dimensions for which the Riemann tensor is entirely given in terms of the Ricci tensor, showing the kinematic property of Einstein gravity for \(N=1\). It is thus a universal feature of pure Lovelock gravity. We will therefore adhere to the pure Lovelock generalization for exploring gravity in higher dimensions.

Rotating black holes are by far the most exciting objects, as they offer a rich arena of interesting physical processes of astrophysical importance in the usual 4 space-time dimensions. These include high energy exotic objects like quasars and active galactic nuclei (AGNs) with their energetic jets, energy extraction processes by the Penrose process [9] and its magnetic version [6, 10–14] and Blandford–Znajek mechanism [15] and particle acceleration [16] as well as optical shadowing of black hole; see, e.g., [17–23].

The possibility to obtain ultra-high energy particles and the appearance of Keplerian discs orbiting Kerr superspinars have been studied in [24, 25]. Keeping in view the physical richness and astrophysical significance of rotating black holes, it would be pertinent to probe these interesting properties for higher dimensional rotating black holes. As argued above, in higher dimensions, pure Lovelock gravity enjoys an unique special position in view of its universal characteristics for all odd and even dimensions. It would therefore be pertinent to study interesting physical and astrophysical phenomena for a pure Gauss–Bonnet (GB) rotating black hole in 6 dimensions. Apart from the astrophysical motivation for this study, there is a fundamental question as to what shape gravitational dynamics takes in higher dimensions. For instance in Einstein gravity, the gravitational field becomes stronger as the dimension increases, which implies that there can exist no bound orbits in dimensions greater than 4, while for pure Lovelock gravity, it becomes weaker with dimension and hence bound orbits continue to exist in all even dimensions [26].

Very recently, a rotating black hole metric has been obtained [27] to describe an analog of a Kerr black hole in pure GB gravity in 6 dimensions. Though it is not an exact solution of the pure Lovelock vacuum equation, it has all the desirable and expected features and it satisfies the equation in the leading order. Some causal structures in Gauss–Bonnet gravity have been analyzed in [28]. In this paper, we wish to study the energetics of a pure GB rotating black hole by employing this metric. Our study yields results which are in tune with the general properties of a rotating black hole and hence it further lends support to the metric for its viability.

Note that Einstein gravity is vacuous in two, kinematic in three, and becoming dynamic in four dimensions. It is pure Lovelock of order \(N=1\). The universalization of this general gravitational feature means that gravity should, respectively, be vacuous, kinematic, and dynamic for \(D = 2N, 2N+1, 2N+2\). This uniquely picks out pure Lovelock gravity; i.e. the gravitational equation in higher dimensions should be pure Lovelock. That is, in all odd and even \(D=2N+1, 2N+2\) dimensions gravitational dynamics should be similar [29]. This is what has been verified in various situations; for instance the black hole entropy is always proportional to square of the horizon’s radius [6, 7] and bound orbits around a static black hole exist only for pure Lovelock gravity in all even \(D=2N+2\) dimensions [26]. This motivates us to examine this general feature in all possible situations and that is what we wish to do it in this paper. We shall therefore study all usual physical processes like energy extraction, Hawking radiation, optical shadowing, and particle acceleration for a pure GB rotating black hole [27] and compare them to that of a rotating black hole in the usual 4-dimensional space-time. This is the primary aim of the paper.

The paper is arranged as follows: the rotating black hole metric is discussed in Sect. 2, while in Sect. 3 we analyze the geodesic equations for circular orbits; this is followed by a discussion of optical shadowing of a black hole in Sect. 4. Next section we study emission energy, energy extraction processes through the BSW effect and the Penrose process. We conclude with a discussion. Throughout the paper, we use a system of units in which the GB coupling constant and velocity of light are set to unity.

2 Pure GB rotating black hole metric

We wish to consider a pure Gauss–Bonnet rotating black hole in the critical 6 dimensions (in odd \(D=5\) GB gravity is kinematic; i.e. GB flat and it becomes dynamic in even \(D=6\) [7]). There does not exist an exact solution of pure GB vacuum equation for an axially symmetric space-time representing a rotating black hole. This is simply because the equations are very formidable to handle. However, for Einstein gravity in 4 dimensions there is the well-known Newman–Janis algorithm for converting a static black hole into a rotating one without solving the equation. This may, however, not be applicable for GB gravity and in higher dimension [30]. Second, one of us [31] has recently obtained the Kerr metric by appealing to the two simple physical considerations. First, it should incorporate Newton’s law in the first approximation, and second, one is free to choose the affine parameter for a null curve and hence the radial coordinate is chosen as the affine parameter for a radially falling photon. For this, one begins with an appropriate spatial geometry, which has ellipsoidal symmetry, and then implements these two common sense inspired physical considerations. What results is the metric [27] considered here. This may describe a rotating black hole, though it is not an exact solution of a pure GB vacuum equation; yet it has all the features of the usual Kerr metric. It, however, does satisfy the equation in the leading order. It has all the characteristics of a rotating black hole in the case there exists an ergosphere, and we have the right limits; for \(a=0\) it reduces to a pure GB static black hole, while \(M=0\) leads to flat space. It is therefore a perfectly appropriate metric for studying a rotating black hole in pure GB gravity. We shall thus employ this rotating black hole metric for studying its various physical properties.

The stationary axisymmetric metric for pure GB rotating black hole in the standard Boyer–Lindquist coordinates reads [27]

with

where M and a have the usual meaning of the total mass and specific angular momentum of black hole.

The space-time (3) has a horizon when \(t= \mathrm{const}\) becomes null; i.e. \(\Delta =0\), which has the following four roots:

with

The function under the square root in Eq. (6),

is always negative and consequently \(r_{3,4}\) is not real, while the function under the square root in Eq. (5),

is non-negative for the range of the rotation parameter \(|a|\le 3\sqrt{3} M/16\) (see Fig. 4), and equality indicates the extremal value of the rotation parameter. \(r_{+,-}\) denote the outer and inner horizons of the hole.

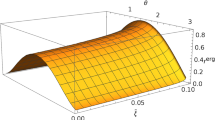

The static limit is defined where the time-translation Killing vector \(\xi _{(t)}^\alpha \) becomes null (i.e. \(g_{00}= \Delta - a^2 \sin ^2\theta = 0\)). The region bounded by the outer horizon and the static limit defines the ergosphere (see Fig. 1), the extent of which increases with the rotation parameter a of the hole.

3 Geodesics and circular orbits

In order to study particle motion around a 6-dimensional pure GB black hole we first write the Hamilton–Jacobi equation,

where m is mass, \(\mathcal{E}\) and \(\mathcal{L}\) are the conserved energy and angular momentum of the particle, respectively.

The issue of the separability of the Hamilton–Jacobi equation in higher dimensional space-time has been widely studied in the literature [32–34]. Particularly, the authors of Refs. [32, 33] have shown that the space-time metric (3) is of Petrov type D.

3.1 Null circular orbits

For null geodesics (when \(m = 0\)), one gets the equations of motion from the Hamilton–Jacobi equation (7),

where the new functions \(\mathcal {R}(r)\) and \(\varTheta (\theta )\),

are introduced.

The conserved quantity \(\mathcal W\) exists only when \(\theta \ne \pi /2\) and is similar to angular momentum. The so-called Carter constant \(\mathcal {K} \) characterizes together with the quantities \(\mathcal E\), \(\mathcal W\), and \(\mathcal L\) the geodetic motion. The Carter constant is not related to any isometry of the space-time unlike the conserved quantities \(\mathcal E\), \(\mathcal W\), and \(\mathcal L\).

By defining \(\xi =\mathcal{L}/\mathcal{E}\), \(\eta =\mathcal {K}/\mathcal{E}^{2}\), and \( \zeta =\mathcal{W}/\mathcal{E}\) and using Eq. (12) we get for the circular orbits characterized by \(\mathcal {R}(r)=0\) and \(\mathrm{d}\mathcal {R}(r)/\mathrm{d}r=0\),

3.2 Timelike circular orbits

Consider the equation of motion of a test particle with non-zero rest mass at the equatorial plane (\(\theta =\pi /2,\ \dot{\theta }=0\)). The equations of motion take the following form:

where

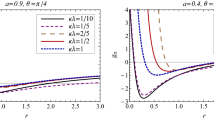

is the effective potential for radial motion. Note that for the orbits in the equatorial plane the new conserved quantity \(\mathcal W\) does not appear in the equations of motion. In Fig. 2 the radial dependence of the effective potential of radial motion in the equatorial plane has been shown for the fixed specific value of the rotation parameter a. The increase of the momentum of the particle leads to the increase of the peak of the potential: initially in-falling test particles become bounded or escape with the increase of the momenta.

The radial dependence of effective potential for the different values of angular momentum of the particle and rotation parameter of the black hole. The left plot corresponds to the case when a varies and the graphs are plotted for the different values of the rotation parameter: \(a/M=0.1\) (dotted line), \(a/M=0.3\) (dashed line), and \(a/M=a_{extr}/M=3\sqrt{3}/16\) (solid line). The right plot corresponds to the case when L varies and the graphs are plotted for the different values of the angular momentum of the particle: \(L/Mm= 1\) (dotted line), \(L/Mm= 5\) (dashed line), and \(L/Mm= 10\) (solid line)

The conditions of the occurrence of circular orbits are

From these equations, it follows that the energy \(\mathcal{E}\) and the angular momentum \(\mathcal{L}\) of a circular orbit of radius \(r_{c}\) are given by

where the \(+\) and \(-\) signs correspond to the co-rotating and counter-rotating particles, respectively.

In Fig. 3 we have shown energy and angular momentum of the co-rotating and counter-rotating orbits in the equatorial plane for different values of the rotation parameter a. One can easily see the shift in location of the minimal circular (MC) orbit marking the existence limit given by the photon circular orbit and the innermost stable circular orbits (ISCO). The MC orbit and ISCO come closer to the hole with increase in a for co-rotating orbits, while the opposite happens for counter-rotating ones.

The vanishing of the denominator in the expressions for \(\mathcal{E}\) and \(\mathcal{L}\) marks the location of a photon’s circular orbit or MC orbit, while for ISCO we have \(\mathrm{d}r/\mathrm{d}\sigma =V_\mathrm{eff}'(r)=0\) and \(V_\mathrm{eff}''(r)\ge 0\). In Fig. 4 we have shown three regions as dark, light gray, and white, marking the boundaries of stable, unstable, and no circular orbits. The inner boundary of light gray is defined by a photon’s circular orbit and the white region bounded between it and the horizon is the one where no circular orbits can exist. This is the region between 3M and 2M for the Schwarzschild black hole. As expected these regions are quite similar to that of the 4-dimensional Kerr black hole.

At this point it may be mentioned that bound orbits cannot exist for Einstein gravity in dimensions \(\ge 4\) [7] in general, and in particular their non-existence is shown for a 6-dimensional rotating black hole in Ref. [35]. For pure Lovelock gravity they do always exist in all even dimensions, \(D=2N+2\) [7].

4 Black hole shadow

In this section we study the optical properties of a black hole in Gauss–Bonnet gravity. If the bright source is located behind the black hole then a distant observer is able to detect only photons scattered away from the black hole, and those captured by the event horizon form a dark spot. This dark region, which could be detected and extracted from the luminous background, is traditionally called the black hole shadow or silhouette. In practice, the distant observer at infinity could see a projection of it on the flat plane passing through the black hole and normal to the line connecting it with the observer (the line of sight). The Cartesian coordinates at this plane, which are usually denoted by \(\alpha \) and \(\beta \) and called celestial coordinates, give the apparent position of the shadow image. The celestial coordinates are connected with the geodesic equations of photons around the black hole as [39]

with \(r_{0}\rightarrow \infty \), \(\theta _{0}\) being the inclination angle between the line of sight of the far observer and the axis of rotation of the black hole [40]; also see [41].

Note here that a silhouette of the black hole is observed in 3-D space and here we would like to check the influence of the extra dimensions to the shape of the black hole shadow.

With the help of the expressions for the impact parameters derived in Sect. 3 and the equations of motion obtained from the Hamilton–Jacobi equation (7), one can get \(\mathrm{d}\phi /\mathrm{d}r\) and \(\mathrm{d}\theta /\mathrm{d}r\), and insert them into Eqs. (25) and (26) in order to get the explicit expressions for the celestial coordinates:

We will concentrate here on the special case when the inclination angle \(\theta _0=\pi /2\) is similar to that for 4-dimensional Kerr space-time (see e.g. [36, 42–44]). Then for the pure GB 6-D rotating black hole we have

To get the boundary of the black hole shadow one can plot the dependence of the coordinate \(\beta \) from the coordinate \(\alpha \); see e.g. [41]. In Fig. 5, we compare the shadow of a 6-dimensional black hole in Gauss–Bonnet gravity with one of 4-dimensional Kerr black hole, which are shown for the different values of the rotation parameter a. The contours of the shadows of the Gauss–Bonnet black hole for the spin parameters \(a=0\), \(a=a_{\mathrm{ext}}/2\), and \(a=a_{\mathrm{ext}}\) are shown in Fig. 5. One can easily see that the photon sphere is decreased with the increase of the spin of the black hole in Gauss–Bonnet gravity. This behavior is exactly the same as in the Kerr space-time [36].

The observable parameters, as the distortion parameter \(\delta _{s}\) and radius of the shadow \(R_s\) can be computed numerically using either Eqs. (29) and (30) or images from Fig. 5. The distortion parameter \(\delta _{s}=\Delta x/ R_s\) [36, 41], where \(\Delta x\) is the deviation parameter, which is the distance between the edge point of the full circle and the edge point of the shadow [41]. Consequently if the rotation parameter is equal to zero, \(a=0\), then \(\Delta x\) must vanish. On the other hand, if we consider a rotating black hole, \(\Delta x\) is non-zero and consequently \(\delta _{s}\) depends on the spin parameter of a black hole.

In Fig. 6, the observables \(R_{s}\) and \(\delta _{s}\) as functions of the rotation parameter of the black hole are shown when the inclination angle \(\theta _{0}=\pi /2\).

From these plots one may conclude that with the increase of the spin parameter a of the black hole in Gauss–Bonnet gravity the shape of the shadow is decreasing, which is similar to the Kerr black hole case. The increase of \(\delta _s\) with the increase of the rotation parameter a corresponds to a deviation of the shape of the shadow from a circle.

Shadow of the rotating GB black holes when the inclination angle \(\theta = \pi /2\). For comparison we present the shadow of a rotating Kerr black hole (dashed lines). From left to right, the rotation parameter scans as \(a=0, a_\mathrm{ext}/2,\,\mathrm{and}\,a_\mathrm{ext} \). Note that for the pure GB 6-D black hole \(a_\mathrm{ext}=3\sqrt{3}/16\) as against \(a_\mathrm{ext}=1\) for the Kerr black hole

Dependence of the energy emission on the frequency for the different values of the spin parameter a: \(a/M=0.1\) (solid line), \(a/M=0.3\) (dashed line), \(a/M=a_{extr}/M=3\sqrt{3}/16\) (dot-dashed line). The left panel is for a black hole in the Gauss–Bonnet case and the right panel is for a 4D black hole in the Kerr space-time [38]

5 Energetics

5.1 Emission energy of 6D rotating black hole

As the next step we plan to calculate the energy emission from a rotating black hole in higher dimensional Gauss–Bonnet gravity as [38]

where \(\omega \) is the frequency of the emission, \(T=({r_{+}^2-3a^2})/ ({8 \pi r_{+} (r_{+}^2+a^2)})\) is the Hawking temperature for the Gauss–Bonnet black hole (for comparison, \(T=({r_{+}^2-a^2})/(4 \pi r_{+} (r_{+}^2+a^2))\) is the Hawking temperature of the Kerr black hole [38]), which can be computed from this expression \(T=k/ 2\pi \), and k is surface gravity. \(R_{s}\) is the radius of the shadow, which is shown in Fig. 6 for the second order Lovelock space-time [38].

The comparison of the energy emission of the rotating black hole in Gauss–Bonnet gravity and Kerr space-time for the different values of the spin parameters \(a=0.1\) (solid line), \(a=0.2\) (dashed line), and \(a=0.3\) (dot-dashed line) is represented in Fig. 7. The rate of the energy emission decreases as the rotation parameter increases. The emission is more intense for the Kerr black hole as compared to the GB one.

5.2 Particle acceleration through BSW effect

Here first we define the energy \(E_\mathrm{cm}\) in the center of mass of a system of two colliding particles with energy at infinity \(E_{1}\) and \(E_{2}\) in the gravitational field described by the space-time metric (3) as

where \(p_\mathrm{(tot)}^{\alpha }=p_\mathrm{(1)}^{\alpha }+p_\mathrm{(2)}^{\alpha }\) is the total momenta of particles 1 and 2 with the mass \(m_{1}\), \(m_{2}\), respectively. We assume that two particles with equal mass (\(m_{1}=m_{2}=m_{0}\)) have an energy at infinity \(E_{1}=E_{2}\simeq 1\), and consequently

Now using Eqs. (19)–(21) we derive an expression for the center-of-mass energy of particles in collision in the vicinity of the Gauss–Bonnet black hole:

where we put \(M=1\) and \(l_1={L_1}/{m_1}\), \(l_2={L_2}/{m_2}\).

For the extremal rotating Gauss–Bonnet black hole when \(a=3\sqrt{3}/16\) the center-of-mass energy at the horizon has the following limit:

Now we study the maximal energy which can be extracted through the BSW process [16] discussed in the Introduction from a rotating Gauss–Bonnet black hole. For this purpose, first we need to study the energy of the test particle moving on the innermost stable circular orbit. Then we define the coefficient of the total amount of released energy of the test particle on shifting from its stable circular orbit with the radius \(r_c\) to the ISCO with the radius \(r_\mathrm{ISCO}\). The energy release efficiency coefficient is given by

The radial dependence of the efficiency coefficient \(\eta \) for the different values of the rotation parameter a is shown in Fig. 8. The maximal energy extraction is for an extremal black hole for which \(r_{_{\mathrm{ISCO}}}=r_{h}\) and so we obtain the maximal limit as \(\eta \simeq 55.28 \%\).

5.3 Penrose process

The existence of an ergosphere around the rotating black hole, where negative energy states for the particles moving along the timelike or null trajectory are present, gives us an opportunity to consider the energy extraction from the rotating black hole through a Penrose process. Assume a small particle A falls down into the ergosphere of the black hole from far infinity. In the vicinity of the event horizon it splits into two fragments, B and C. If particle B with the negative energy with respect to infinity falls into the central black hole, then the emergent particle C has an energy exceeding the energy of the incident particle A. We have

where the following notations:

have been used.

As the particle falls inside the event horizon the change of the mass of central rotating black hole is defined as \(\delta M=E\). In principle one can increase the mass of the black hole increasing the number of the in-falling test particles with positive energy.

The minimum value of the central black hole mass \(\delta M\) is achieved for the condition when \(m=0\), \(p^{\theta }=0\), \(p^{\psi }=0\), and \(p^{r}=0\). Then one can get the expression for the minimum energy:

where we have introduced the notation

using the values of the mass of the particle and the momenta for the minimum condition.

Next we discuss the energy extraction efficiency from Gauss–Bonnet black hole through Penrose process. As in the case of the BSW process we introduce the coefficient of efficiency of the Penrose process by

where \(E_{A}\) is the energy of the incident particle and \(E_{C}\) is that of the emergent outgoing one. Using the energy conservation law for the particles A, B, and C, one can find the maximal value of \(\eta _P\) in the form

Evaluating this expression near the event horizon of an extreme rotating Gauss–Bonnet black hole one can find the maximal efficiency with the value of 25.8 %. Note that the energy extraction efficiency for the Penrose process in the case of an extreme rotating 4-D Kerr black hole was found to be 20.7 % [13, 45].

6 Discussion

The elemental feature of pure Lovelock gravity is that gravitational dynamics in all odd and even dimensions is similar. That is why it is expected that physical processes and effects around a 6-dimensional rotating pure GB black hole would be similar to that of a 4-dimensional Kerr black hole. It should, however, be admitted that the black hole metric we have considered has all the desired features of a rotating black hole, but it is not an exact solution of the pure Lovelock vacuum equation, though. It does, however, satisfy the equation in the leading order which is computed as follows. Since the metric goes as \(r^{-1/2}\), the Riemann tensor will go as \(r^{-5/2}\), and then the GB Ricci tensor will go as \(r^{-5}\). For the black hole metric (2), the GB Ricci tensor in fact falls off as \(r^{-7}\), two powers sharper. It could therefore be taken as a good model for describing a rotating pure GB black hole.

As the gravitational potential is weaker than in the case of Einstein gravity, its effects are reflected as follows. The efficiency of the Penrose process decreases and it is reduced to 7.74 % (it is equal to 29 % for the 4-D Kerr black hole), while the opposite is in effect on the particle acceleration efficiency, which is increased to 55.28 % (it is equal to 46 % for the 4-D Kerr black hole). The center-of-mass energy rapidly grows for a collision of particles falling from infinity into a rotating GB black hole in the case when the circular orbits shift arbitrarily close to the horizon. The optical shadow of a black hole also decreases as a lesser number of photons get captured, because of the weakening of the field. All these results are along the lines expected on physical grounds, and hence they provide strength to the validity and viability of the space-time metric used. Put another way, this study could be looked upon as probing the metric in question for its in principle physical and astrophysical validity.

We had set out to study various physical properties of a pure GB rotating black hole and show that they are indeed similar to the rotating black hole in the usual 4-dimensional physical space-time. All this is in line with the pure Lovelock gravity paradigm [29] in higher dimensions.

References

D. Lovelock, J. Math. Phys. 12, 498 (1971). doi:10.1063/1.1665613

N. Dadhich, General Relativity and Quantum Cosmology (2004). arXiv:gr-qc/0495115

N. Dadhich, High Energy Physics–Theory (2005). arXiv:hep-th/0509126

N. Dadhich, Int. J. Mod. Phys. D 20, 2739 (2011). doi:10.1142/S0218271811020573

M. Bañados, C. Teitelboim, J. Zanelli, Phys. Rev. Lett. 72, 957 (1994). doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.72.957

N. Dadhich (2012). arXiv:1210.3022 [gr-qc]

N. Dadhich, S.G. Ghosh, S. Jhingan, Phys. Lett. B 711, 196 (2012). doi:10.1016/j.physletb.2012.03.084

X.O. Camanho, N. Dadhich (2015). arXiv:1503.02889 [gr-qc]

R. Penrose, Riv. Nuovo Cimento 1, 252 (1969)

S.M. Wagh, S.V. Dhurandhar, N. Dadhich, Astrophys. J. 290, 12 (1985). doi:10.1086/162952

S.M. Wagh, S.V. Dhurandhar, N. Dadhich, Astrophys. J. 301, 1018 (1986). doi:10.1086/163965

S.M. Wagh, S.V. Dhurandhar, N. Dadhich, in Quasars, ed. G. Swarup, V. Kapahi. Proc. 4th IAU Symposium 119, Bangalore, 1985, Reidel, Dordrecht (1985)

S. Parthasarathy, S.M. Wagh, N. Dadhich, Astrophys. J. 307, 38 (1986)

S. Koide, T. Baba, Astrophys J. 792, 88 (2014). doi:10.1088/0004-637X/792/2/88

R.D. Blandford, R.L. Znajek, Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc. 179, 433 (1977)

M. Bañados, J. Silk, S.M. West, Phys. Rev. Lett. 103(11), 111102 (2009). doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.103.111102

K.S. Virbhadra, G.F.R. Ellis, Phys. Rev. D 62(8), 084003 (2000). doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.62.084003

K.S. Virbhadra, Phys. Rev. D 79(8), 083004 (2009). doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.79.083004

V. Bozza, F. de Luca, G. Scarpetta, M. Sereno, Phys. Rev. D. 72(8), 083003 (2005). doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.72.083003

C. Bambi, N. Yoshida, Class. Quantum Gravity 27(20), 205006 (2010). doi:10.1088/0264-9381/27/20/205006

A. Grenzebach, V. Perlick, C. Lämmerzahl, Phys. Rev. D 89(12), 124004 (2014). doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.89.124004

H. Falcke, S.B. Markoff, Class. Quantum Gravity 30(24), 244003 (2013). doi:10.1088/0264-9381/30/24/244003

A.A. Abdujabbarov, L. Rezzolla, B.J. Ahmedov (2015). arXiv:1503.09054 [gr-qc]

Z. Stuchlík, J. Schee, Class. Quantum Gravity 30(7), 075012 (2013). doi:10.1088/0264-9381/30/7/075012

Z. Stuchlík, J. Schee, Class. Quantum Gravity 27(21), 215017 (2010). doi:10.1088/0264-9381/27/21/215017

N. Dadhich, S.G. Ghosh, S. Jhingan, Phys. Rev. D 88(12), 124040 (2013). doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.88.124040

N. Dadhich, S.G. Ghosh (2013). arXiv:1307.6166 [gr-qc]

K. Izumi, Phys. Rev. D 90(4), 044037 (2014). doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.90.044037

N. Dadhich (2015). arXiv:1506.08764 [gr-qc]

D. Hansen, N. Yunes, Phys. Rev. D 88(10), 104020 (2013). doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.88.104020

N. Dadhich, Gen. Relativ. Gravit. 45, 2383 (2013). doi:10.1007/s10714-013-1594-x

V.P. Frolov, D. Kubizňák, Class. Quantum Gravity 25(15), 154005 (2008). doi:10.1088/0264-9381/25/15/154005

V. Frolov, D. Stojković, Phys. Rev. D 68(6), 064011 (2003). doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.68.064011

U. Papnoi, F. Atamurotov, S.G. Ghosh, B. Ahmedov, Phys. Rev. D 90(2), 024073 (2014). doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.90.024073

E. Hackmann, V. Kagramanova, J. Kunz, C. Lämmerzahl, Phys. Rev. D 78(12), 124018 (2008). doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.78.124018

K. Hioki, K.I. Maeda, Phys. Rev. D 80(2), 024042 (2009). doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.80.024042

A.F. Zakharov, A.A. Nucita, F. De Paolis, G. Ingrosso, New Astron. Rev. 10, 479 (2005). doi:10.1016/j.newast.2005.02.007

S.W. Wei, Y.X. Liu, JCAP 11, 063 (2013). doi:10.1088/1475-7516/2013/11/063

S.E. Vázquez, E.P. Esteban, Nuovo Cim. B 119, 489 (2004). doi:10.1393/ncb/i2004-10121-y

L. Amarilla, E.F. Eiroa, Phys. Rev. D 85(6), 064019 (2012). doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.85.064019

F. Atamurotov, A. Abdujabbarov, B. Ahmedov, Phys. Rev. D 88(6), 064004 (2013). doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.88.064004

Z. Stuchlík, J. Schee, Class. Quantum Gravity 29(6), 065002 (2012). doi:10.1088/0264-9381/29/6/065002

L. Amarilla, E.F. Eiroa, G. Giribet, Phys. Rev. D 81(12), 124045 (2010). doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.81.124045

L. Amarilla, E.F. Eiroa, Phys. Rev. D 87(4), 044057 (2013). doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.87.044057

S. Chandrasekhar, The Mathematical Theory of Black Holes (Oxford University Press, New York, 1998)

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the project Supporting Integration with the International Theoretical and Observational Research Network in Relativistic Astrophysics of Compact Objects, CZ.1.07/2.3.00/20.0071, supported by Operational Programme Education for Competitiveness funded by Structural Funds of the European Union. One of the authors (ZS) acknowledges the Albert Einstein Center for gravitation and astrophysics supported by the Czech Science Foundation No. 14-37086G. Warm hospitality that has facilitated this work to A.A., B.A. and N.D. by Faculty of Philosophy and Science, Silesian University in Opava (Czech Republic) and by the Goethe University, Frankfurt am Main, Germany is thankfully acknowledged. This research is supported in part by Projects No. F2-FA-F113, No. EF2-FA-0-12477, and No. F2-FA-F029 of the UzAS and by the ICTP through the OEA-PRJ-29 and the OEA-NET-76 projects and by the Volkswagen Stiftung (Grant No. 86 866). A.A. and B.A. acknowledge the TWAS associateship grant.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Funded by SCOAP3.

About this article

Cite this article

Abdujabbarov, A., Atamurotov, F., Dadhich, N. et al. Energetics and optical properties of 6-dimensional rotating black hole in pure Gauss–Bonnet gravity. Eur. Phys. J. C 75, 399 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1140/epjc/s10052-015-3604-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1140/epjc/s10052-015-3604-5