Abstract

Using the Monte Carlo event generator tools Pythia and Herwig, we simulate the production of bottom/charm meson and antimeson pairs at hadron colliders in proton–proton/antiproton collisions. With these results, we derive an order-of-magnitude estimate for the production rates of the bottom analogs and the spin partner of the \(X(3872)\) as hadronic molecules at the LHC and Tevatron experiments. We find that the cross sections for these processes are at the nb level, so that the current and future data sets from the Tevatron and LHC experiments offer a significant discovery potential. We further point out that the \(X_b/X_{b2}\) should be reconstructed in the \(\gamma \Upsilon (nS) (n=1,2,3)\), \(\Upsilon (1S)\pi ^+\pi ^-\pi ^0\), or \(\chi _{bJ}\pi ^+\pi ^-\) instead of the \(\Upsilon (nS)\pi ^+\pi ^-\) final states.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

As the \(B\) factories and high energy hadron colliders have accumulated unprecedented data samples, a dramatic progress has been made in hadron spectroscopy in the past decade. Especially, in the mass region of heavy quarkonia, a number of new and unexpected structures have been discovered at these experimental facilities. Many of them defy an ordinary charmonium interpretation; the \(X(3872)\) has received the most intensive attention [1] so far.

The \(X(3872)\) was first discovered by the Belle Collaboration in \(B\) decays at the \(e^+e^-\) collider located at KEK [2] and later confirmed by the BaBar Collaboration [3] in the same channel. It can also be copiously produced in high energy proton–proton/antiproton collisions at the Tevatron [4, 5] and LHC [6, 7]. This meson is peculiar in several aspects, and its nature is still under debate. The total width is tiny compared to typical hadronic widths and only an upper bound has been set: \(\Gamma <1.2\) MeV [8]. The mass lies in the extreme close vicinity to the \(D^0\bar{D}^{*0}\) threshold, \(M_{X(3872)}-M_{D^0}-M_{D^{*0} }=(-0.12\pm 0.24)\) MeV [9], which leads to speculations of the \(X(3872)\) as a hadronic molecule—either a \(D\bar{D}^*\) loosely bound state [10] or a virtual state [11]. Furthermore, a large isospin breaking is found in its decays: the process \(X(3872) \rightarrow J/\psi \pi ^+\pi ^-\) via a virtual \(\rho ^0\) and the process \(X(3872)\rightarrow J/\psi \pi ^+\pi ^-\pi ^0\) via a virtual \(\omega \) have similar partial widths [8]. Evidence for different rates of charged and neutral \(B\) decays into \(X(3872)\) was also found [12].

These facts have stimulated great interest in understanding the nature, production and decays of the \(X\)(3872). An important aspect involves the discrimination of a compact multiquark configuration and a loosely bound hadronic molecule configuration. Recent calculations of the hadroproduction rates at the LHC based on non-relativistic QCD indicate that the \(X\)(3872) could hardly be an ordinary charmonium \(\chi _{c1}(2P)\) [13, 14], while there is sizable disagreement in theoretical predictions in the molecule picture [15–19].

To clarify the intriguing properties and finally decipher the internal nature, more accurate data and new processes involving the production and decays of the \(X\)(3872) will be helpful. For instance, one may obtain useful information on the flavor content of the \(X\)(3872) from precise measurements of decays of neutral/charged \(B\) mesons into the \(X\)(3872) associated with neutral/charged \(K^*\) mesons.

On the other hand, it is also expedient to look for the possible analog of the \(X(3872)\) in the bottom sector, referred to as \(X_b\) following the notation suggested in Reference [20]. If such a state exists, measurements of its properties would assist us in understanding the formation of the \(X(3872)\) as the underlying interaction is expected to respect heavy flavor symmetry. In fact, the existence of such a state was predicted in both the tetraquark model [21] and the hadronic molecular calculations [22–24]. The mass of the lowest-lying \(1^{++}\) \(\bar{b} \bar{q} bq\) tetraquark was predicted to be 10504 MeV in Reference [21], while the mass of the \(B\bar{B}^*\) molecule based on the mass of the \(X(3872)\) is a few tens of MeV higher [23, 24]. In Reference [23], the mass was predicted to be \((10580^{+9}_{-8})\) MeV for a typical cutoff, corresponding to a binding energy of \((24^{+8}_{-9})\) MeV.

Notice that there is a big difference between the predicted \(X_b\) and the \(X(3872)\). The distance of the mass of the \(X(3872)\) to the \(D^0\bar{D}^{*0}\) threshold is much smaller than the distance to the \(D^+D^{*-}\) threshold. This difference leaves its imprint in the wave function at short distances through the charmed meson loops so that a sizable isospin breaking effect is expected. However, the mass difference between the charged and neutral \(B\) mesons is only \((0.32\pm 0.06)\) MeV [8], and the binding energy of the \(B\bar{B}^*\) system may be larger than that in the charmed sector due to a larger reduced mass. In addition, while the isospin breaking observed in the \(X(3872)\) decays into \(J/\psi \) and two/three pions can be largely explained by the phase-space difference between the \(X(3872)\rightarrow J/\psi \rho \) and the \(X(3872)\rightarrow J/\psi \omega \) [25], the phase-space difference between the \(\Upsilon \rho \) and \(\Upsilon \omega \) systems will be negligible since the mass splitting between the \(X_b\) and the \(\Upsilon (1S)\) is definitely larger than 1 GeV. Therefore, we expect that the isospin breaking effects would be much smaller for the \(X_b\) than that for the \(X(3872)\). Consequently, the \(X_b\) should be an isosinglet state to a very good approximation, in line with the predictions in References [22–24].

Since the mass of the \(X_b\) is larger than 10 GeV and its quantum numbers \(J^{PC}\) are \(1^{++}\), it is unlikely to be discovered at the current electron–positron colliders, though the prospect for an observation in the \(\Upsilon (5S,6S)\) radiative decays at the Super KEKB in future may be bright due to the expected large data sets, of order \(50~\mathrm{ab}^{-1}\) [26]. See Reference [27] for a recent search in the \(\Upsilon \omega \) final state. There have been works on the production of the exotic states, especially hadronic molecules, at hadron colliders [16–19, 28–31]. In this paper, we will follow closely Reference [31], which uses effective field theory (EFT) to cope with the two-body hadronic final state interaction (FSI), and focus primarily on the production of the \(X_b\) and its spin partner, a \(B^*\bar{B}^*\) molecule with \(J^{PC}= 2^{++}\), denoted \(X_{b2}\), at the LHC and the Tevatron. Results on the production of the spin partner of the \(X(3872)\), \(X_{c2}\) with \(J^{PC}=2^{++}\), will also be given. Notice that due to heavy quark spin symmetry, the binding energies of the \(X_{b2}\) and \(X_{c2}\) are similar to those of the \(X_b\) and \(X(3872)\), respectively. In addition, we will also revisit the production of the \(X(3872)\) and compare the obtained results with the experimental data.

This paper is organized as follows. We begin in Sect. 2 by discussing the factorization formula for the \(pp/\bar{p}\rightarrow X\) (here \(X\) is used to represent all the above mentioned candidates of hadronic molecules, and both \(pp\) and \(p\bar{p}\) will be written as \(pp\) for simplicity in the following) amplitudes in case that the \(X\) states are bound states not far from the corresponding thresholds. Our numerical results for the cross sections are presented in Sect. 3. The last section contains a brief summary.

2 Hadroproduction

The universal scattering amplitude of particles with short-range interaction provides an easy way to derive the formula for estimating the cross section of the inclusive production of an \(S\)-wave loosely bound hadronic molecule [18, 19]. However, the amplitude derived in an EFT can also be used for such a purpose [31]. Furthermore, by investigating the consequences of heavy quark symmetries on the \(X(3872)\) within an EFT framework, Reference [23] predicted the bottom analogs and the spin partner of \(X(3872)\). In the following, we will follow Reference [31] and use the EFT as adopted in Reference [23] to obtain a factorization formula, which will enable us to estimate the inclusive production cross sections for the \(X\) production.

When the binding energy of a bound state is small, we can assume that the formation of the hadronic molecule, which is a long-distance process, would occur after the production of its constituents, which is of short-distance nature. The mechanism is shown in Fig. 1. Therefore, the amplitude for the production of the hadronic molecule can be written as [31]

where \(\mathcal{M}[HH^{\prime } + \text {all}]\) is the amplitude for the inclusive production of heavy mesons \(H\) and \(H^{\prime }\), \(T_X\) is amplitude for the process \(HH'\rightarrow X\), and \(G\) is the Green function of the heavy meson pair. In general, the above equation is an integral equation with all the parts on the right-hand-side involved in an integral over the momentum of the intermediate mesons. However, in the case that the hadronic molecule is a loosely bound state, \(T_X\) can be approximated by the coupling constant \(g\) of the \(X\) to its constituents, and as argued in Reference [18], one should be able to approximate the production amplitude \(\mathcal{M}[HH^{\prime } + \text {all}]\), which does not take into account the FSI carrying a strong momentum dependence near threshold, by a constant.

Thus, both \(\mathcal{M}[HH^{\prime } + \text {all}]\) and \(g\) can be taken outside the momentum integral, and \(G\) becomes a two-point scalar loop function.

The general differential Monte Carlo (MC) cross section formula for the inclusive \(HH^{\prime }\) production reads

where \(k\) is the three-momentum in the center-of-mass frame of the \(HH^{\prime }\) pair, \(\mu \) is the reduced mass of the \(HH^{\prime }\) pair and \(K_{HH^{\prime }}\sim \mathcal{O}(1)\) is introduced because of the overall difference between MC simulation and the experimental data, while for an order-of-magnitude estimate we can roughly take \(K_{HH^{\prime }}\simeq 1\). Without considering the FSI, the matrix element \(\mathcal{M}[HH^{\prime }(k) +\text {all}]\) is a constant and thus we have

On the other hand, the cross section for the production of the \(X\), which stands for \(X(3872)\), \(X_b\), \(X_{b2}\) or \(X_{c2}\), is

where the phase-space integration is the same as that in Eq. (2). Therefore the cross section of \(X\) can be rewritten with Eqs. (1) and (2) as

Since we will study the production of the hadronic molecules predicted in Reference [23], we will use the same Gaussian cutoff to regularize the divergent loop integral \(G\), and we have [32]

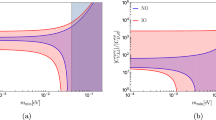

where \(D(x)=\mathrm{e}^{x^2}\,\int ^{x}_0\,\mathrm{e}^{-y^2}\,\mathrm{d}y\) is the Dawson function, \(\gamma =\sqrt{-2\mu (E-m_H-m_{H'})}\) is the binding momentum and \(\Lambda \) is the cutoff. Following Reference [23], a range of \([0.5,1.0]\) GeV will be used to the cutoff \(\Lambda \). By considering only the leading order contribution, the pole of the bound state satisfies the equation \(1-C_0\,G[E_\text {pole},\Lambda ]=0\), where \(C_0\) is the leading order low energy constant which describes the contact interaction between the considered heavy meson pair. The renormalization group invariance requires that \(C_0\) depends on \(\Lambda \) as well in order to make the physical observables cutoff independent. The coupling constant \(g\) in Eq. (5) is related to the residue of the bound state pole by

where \(s\) is the center-of-mass energy squared.

3 Results and discussions

In order to form a molecule, the mesonic constituents must be produced at first and have to move collinearly with a small relative momentum. Such configurations originate from the inclusive QCD process which contains a \(\bar{Q}Q\) pair with a similar relative momentum in the final state. Thus, at least a third parton needs to be produced in the recoil direction, which corresponds to a \(2\rightarrow 3\) parton process. In our explicit realization, the \(2\rightarrow 3\) process can be generated initially through hard scattering, and the parton shower will produce more quarks via soft radiations.

Following our previous work [30], we use Madgraph [33] to generate the \(2\rightarrow 3\) partonic events with a pair of a heavy quark and an antiquark (\(\bar{b} b\) or \(\bar{c}c\)) in the final states, and then pass them to the MC event generators for hadronization. We choose Herwig [34] and Pythia [35] as the hadronization generators, whose outputs are analyzed using the Rivet library [36].

To improve the efficiency of the calculation, we apply the partonic cuts for the transverse momentum \(p_T>2\) GeV for heavy quarks and light jets, \(m_{c\bar{c}}< 4.5\) GeV (\(k_{D\bar{D}^*}=1.14\) GeV and \(k_{D^*\bar{D}^*}=1.02\) GeV), \(m_{b\bar{b}}< 10.7\) GeV (\(k_{B\bar{B}^*}=715\) MeV and \(k_{B^*\bar{B}^*}=517\) MeV at the hadron level), and \(\Delta R(c, \bar{c})<1\)(\(\Delta R(b, \bar{b})<1\)) where \(\Delta R=\sqrt{\Delta \eta ^2 +\Delta \phi ^2}\) (\(\Delta \phi \) is the azimuthal angle difference and \(\Delta \eta \) is the pseudo-rapidity difference of the \(b\bar{b}\)).

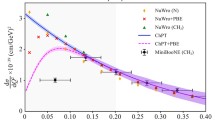

Before proceeding to the predictions for the bottom analogs and the spin partner of the \(X(3872)\), we shall revisit the production of the \(X(3872)\) and compare the results with the experimental data. Such a comparison requires a range for the branching ratio \(\mathcal{B}(X(3872)\rightarrow J/\psi \pi ^+ \pi ^-)\). Making use of the Babar upper limit for \(\mathcal{B}(B^+\rightarrow X(3872)K^+)\) [37] and the most recent Belle measurement of \(\mathcal{B}(B^+\rightarrow X(3872)K^+) \times \mathcal{B}(X(3872)\rightarrow J/\psi \pi ^+ \pi ^-)\) [38],

we can derive a lower bound:

On the other hand, summing over the branching fractions of \(X(3872)\) to all measured channels which, in addition to the \(J/\psi \pi ^+\pi ^-\) [38], include \(D^0\bar{D}^{*0}+c.c.\) [39], \(J/\psi \omega \) [40], \(\psi '\gamma \) and \(J/\psi \gamma \) [41, 42] can provide an upper bound for the branching fraction of the \(X(3872)\rightarrow J/\psi \pi ^+ \pi ^-\):

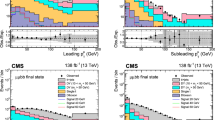

Differential cross sections \({\mathrm{d}\sigma }/{\mathrm{d}k}\) (in units of nb/GeV) for the process \(pp\rightarrow B^0\bar{B}^{*0}\) at the LHC with \(\sqrt{s}=8\) TeV (upper panels) and at the Tevatron with \(\sqrt{s}=1.96\) TeV (lower panel). The kinematic cuts for the left-upper panel are used as \(|y|<2.5\) and \(p_T>5\) GeV, which lie in the phase-space regions of the ATLAS and CMS detectors, for the Tevatron experiments (CDF and D0) at 1.96 TeV (the lower panel), we use \(|y| <0.6\); the rapidity range \(2.0<y<4.5\) is used for LHCb (the right-upper panel)

In Table 1, we show the integrated cross sections (in units of nb) for the \(pp/\bar{p}\rightarrow X(3872)\) and compare with previous theoretical estimates [16, 18] and experimental measurements by the CDF Collaboration [43]

and by the CMS Collaboration [6]

The same kinematical cuts on the transverse momentum and rapidity as those in the experimental analyses were implemented: \(p_T>5 \) GeV and \(|y|<1.2\) at the Tevatron and \(10\, \mathrm{GeV}<p_T<50\, \mathrm{GeV}\) and \(|y|<0.6\) at the LHC with \(\sqrt{s}=7\) TeV. In this table, we have converted the experimental data to \({ \sigma }(p\bar{p}/pp\rightarrow X)\). A very small upper bound was derived for \({ \sigma }(p\bar{p}/pp\rightarrow X)\) in Reference [16], and the predicted values are increased in Reference [18] by taking into account the FSI using the universal scattering amplitude. As shown in this table, our results agree with the experimental measurements quite well, which validates our calculation based on an EFT treatment of the FSI.

Uncertainties in our results come from the parameter \(\Lambda \) in the loop function in Eq. (5). Based on heavy quark symmetries, this parameter has been adopted as \(\Lambda \in [0.5,1]\) GeV [23]. Different values will give rise to different binding energies of the counterparts for instance the \(X_b\), ranging from \(24\) to \(66\) MeV. Measurements of the \(X_b\) mass in future will reduce the errors. Taking into account these uncertainties, our results for the cross section at the Tevatron are given as

and at the LHC with \(\sqrt{s}=7\) TeV

Based on \(10^7\) partonic events generated by Madgraph, we show the differential cross sections \({\mathrm{d}\sigma }/{\mathrm{d}k}\) (in units of nb/GeV) for the process \(pp\rightarrow B^0\bar{B}^{*0}\) in Fig. 2, and the ones for the reaction \(pp\rightarrow B^{*0}\bar{B}^{*0}\) in Fig. 3 at the LHC with the center-of-mass energy \(\sqrt{s}=8\) TeV and at the Tevatron with \(\sqrt{s}=1.96\) TeV. The kinematic cuts are \(|y|<2.5\) and \(p_T>5\) GeV, where \(y\) and \(p_T\) are the rapidity and the transverse momentum of the bottom mesons, respectively, which lie in the phase space regions of the ATLAS and CMS detectors. For the Tevatron experiments (CDF and D0) at 1.96 TeV, we use \(|y| <0.6\); the rapidity range \(2.0<y<4.5\) is used for the LHCb detector. We have checked that \(\mathrm{d}\sigma /\mathrm{d}k\) is approximately proportional to \(k^{2}\), cf. Eq. (3).

Same as Fig. 2 but for the \(B^*\bar{B}^*\) final state

Integrated cross sections (in units of nb) for the \(pp\rightarrow X_b\), and \(pp\rightarrow X_{b2,c2}\) are collected in Table 2. Results outside (inside) brackets are obtained using Herwig (Pythia).

From the table, one sees that the cross sections for the \(X_{b2}\) is similar to those for the \(X_b\), and the ones for the \(X_{c2}\) are of the same order as those for the \(X(3872)\) given in Table 1 and are two orders of magnitude larger than those for their bottom analogs.

Recently, the CMS Collaboration has presented results of a first search for new bottomonium states, with the main focus on the \(X_b\), decaying to \(\Upsilon (1S)\pi ^+\pi ^-\). The search is based on a data sample corresponding to an integrated luminosity of 20.7 \(\mathrm{fb}^{-1}\) at \(\sqrt{s} = 8\) TeV [44]. No evidence for the \(X_b\) is found, and the upper limit at a confidence level of 95 % on the product of the production cross section of the \(X_b\) and the decay branching fraction of \(X_b\rightarrow \Upsilon (1S)\pi ^+\pi ^-\) has been set to be

where the range corresponds to the variation of the \(X_b\) mass from 10 to 11 GeV.

Using the current experimental data on the \(\sigma (pp\rightarrow \Upsilon (2S))\), we can convert the above ratio into the cross section which can be directly compared with our results. Since the masses of the \(\Upsilon (2S)\) and \(X_b\) are not very different, it may be a good approximation to assume that the ratio given in Eq. (15) is insensitive to kinematic cuts. Using the CMS measurement in Reference [45]:

with the cuts \(p_T< 50\) GeV and \(|y|<2.4\) for the \(\Upsilon (2S)\), we get

Taking into account theoretical errors, our estimate for the cross section \(\sigma (pp\rightarrow X_b )\) is

However, since the branching ratio \(\mathcal{B}(X_b\rightarrow \Upsilon (1S)\pi ^+\pi ^-)\) is expected to be tiny because of isospin breaking (see below), our result given in Eq. (18) is consistent with the CMS upper bound in Eq. (17).

As already discussed in the Introduction, \(X_b\) and \(X_{b2}\) are isosinglets. In contrast to \(X(3872)\), the isospin breaking decays of these two states will be heavily suppressed. Thus, one shall not simply make an analogy to \(X(3872)\rightarrow J/\psi \pi ^+\pi ^-\) and attempt to search for \(X_b\) in the \(\Upsilon (1S,2S,3S)\pi ^+\pi ^-\) channels, as the isospin of the \(\Upsilon (1S,2S,3S)\pi ^+\pi ^-\) systems is one when the quantum numbers are \(J^{PC}\!=\!1^{++}\). This could be the reason for the negative search result by the CMS Collaboration [44]. Possible channels which can be used to search for \(X_b\) and \(X_{b2}\) include the \(\Upsilon (nS)\gamma \,(n=1,2,3)\), \(\Upsilon (1S)\pi ^+\pi ^-\pi ^0\) and \(\chi _{bJ}\pi ^+\pi ^-\). The \(X_{b2}\) can also decay into \(B\bar{B}\) in a \(D\)-wave, and the decays of \(X_{c2}\) are similar to those of \(X_{b2}\) with the bottom being replaced by its charm analog. The isospin breaking decay \(X_{c2}\rightarrow J/\psi \pi ^+\pi ^-\) through an intermediate \(\rho \) meson should be largely suppressed compared with the decay of \(X(3872)\) into the same particles because the mass of \(X_{c2} \) is about 140 MeV higher than that of \(X(3872) \), and the phase-space difference between \(J/\psi \rho \) and \(J/\psi \omega \) becomes negligible.

Compared with the pionic decays, \(\Upsilon (nS)\gamma \,(n=1,2,3)\) final states are advantageous because no pion needs to be disentangled from the combinatorial background. The disadvantage is the low efficiency in reconstructing a photon at hadron colliders. Since the \(X(3872)\) meson has a sizable partial decay width into \(J/\psi \gamma \) [8],

presumably the branching ratio for \(X_b\rightarrow \gamma \Upsilon \) is of this order; see Reference [46] for an estimate. If so, the cross section for \(pp\rightarrow X_b\rightarrow \gamma \Upsilon (1S)\rightarrow \gamma \mu ^+\mu ^-\) is of \(\mathcal{O}(10~\text {fb})\) or even larger when summing up \(\Upsilon (1S,2S,3S)\). Since the CMS and ATLAS Collaborations have accumulated more than 20 fb\(^{-1}\) data [47, 48], we expect at least a few hundred events. Less events will be collected at the LHCb detector due to a smaller integrated luminosity, \(\mathcal{O}(3~\mathrm{fb}^{-1})\) [49]. Nevertheless, the future prospect is bright since a data sample of about \(3{,}000~\mathrm{fb}^{-1}\), will be collected, for instance, by ATLAS after the upgrade [50].

Apart from the production rates, the nonresonant background contributions can also play an important role in the search for these molecular states at hadron colliders since a signal could be buried by a huge background. To investigate this issue, we consider \(X_b\) as an example, which will be reconstructed in \(\Upsilon +\gamma \) final states. In this process, the inclusive cross section \(\sigma (pp\rightarrow \Upsilon )\) can serve as an upper bound for the background. It has been measured at \(\sqrt{s}= 7 \) TeV by the ATLAS Collaboration as [53]

with \(p_T< 70 \) GeV and \(|y|<2.25\). Our results in Table 2 show that the corresponding cross section for \(pp\rightarrow X_b\) is about 1 nb at \(\sqrt{s}= 7 \) TeV. It is noteworthy to point out that our kinematic cuts in \(p_T\) are more stringent compared to the ones set by the ATLAS Collaboration. Using the integrated luminosity in 2012, 22 fb\(^{-1}\) [47], we have a lower bound estimate for the signal/background ratio

where \(2.6\,\%\) is the branching fraction of \(\Upsilon (1S)\rightarrow \mu ^+\mu ^-\) [8], and \(10^{-2}\) is a rough estimate for the branching fraction of \(X_b\rightarrow \Upsilon (1S)\gamma \). The value of the signal/background ratio can be significantly enhanced in the data analysis by employing suitable kinematic cuts which can greatly suppress the background, and accumulating many more events based on the upcoming \(3{,}000~\mathrm{fb}^{-1}\) data [50].

4 Summary

In summary, we have made use of the Monte Carlo event generator tools Pythia and Herwig, and explored the inclusive processes \(pp/\bar{p}\rightarrow B^0\bar{B}^{*0}\) and \(pp/\bar{p}\rightarrow B^{*0}\bar{B}^{*0}\) at hadron colliders. Based on the molecular picture, we have derived an order-of-magnitude estimate for the production rates of the \(X_b\), \(X_{b2}\), and \(X_{c2}\) states, the bottom and spin partners of \(X(3872)\), at the LHC and Tevatron experiments. We found that the cross sections are at the nb level for the hidden bottom hadronic molecules \(X_b\) and \(X_{b2}\), and two orders of magnitude larger for \(X_{c2}\). Therefore, one should be able to observe them at hadron colliders if they exist in the form discussed here. The channels which can be used to search for \(X_b\) and \(X_{b2}\) include \(\Upsilon (nS)\gamma \,(n=1,2,3)\), \(\Upsilon (1S)\pi ^+\pi ^-\pi ^0\), \(\chi _{bJ}\pi ^+\pi ^-\) and \(B\bar{B}\) (the last one is only for \(X_{b2}\)), and the channels for the \(X_{c2}\) is similar to those for \(X_{b2}\) (with the bottom replaced by its charm analog). In fact, both the ATLAS and the D0 Collaborations reported an observation of the \(\chi _b(3P)\) [51, 52], whose mass is \((10534\pm 9)\) MeV [8], slightly lower than the \(X_b\) and \(X_{b2}\), in the \(\Upsilon (1S,2S)\gamma \) channels. A search for these states will provide very useful information in understanding \(X(3872)\) and the interactions between heavy mesons. Especially, if the \(X_b\), which is the most robust among the predictions in Reference [23], based on heavy quark symmetries, cannot be found in any of these channels, it may imply a non-molecular nature for \(X(3872)\).

References

N. Brambilla, S. Eidelman, B.K. Heltsley, R. Vogt, G.T. Bodwin, E. Eichten, A.D. Frawley, A.B. Meyer et al., Eur. Phys. J. C 71, 1534 (2011)

S. K. Choi et al., Belle Collaboration, Phys. Rev. Lett. 91, 262001 (2003). hep-ex/0309032

B. Aubert et al., BaBar Collaboration, Phys. Rev. D 71, 071103 (2005). hep-ex/0406022

V.M. Abazov, et al., D0 Collaboration, Phys. Rev. Lett. 93, 162002 (2004)

T. Aaltonen et al., CDF Collaboration, Phys. Rev. Lett. 103, 152001 (2009). arXiv:0906.5218 [hep-ex]

S. Chatrchyan et al., CMS Collaboration, JHEP 1304, 154 (2013). arXiv:1302.3968 [hep-ex]

R. Aaij et al., LHCb Collaboration, Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 222001 (2013). arXiv:1302.6269 [hep-ex]

J. Beringer et al., Particle Data Group Collaboration, Phys. Rev. D 86, 010001 (2012) (2013 partial update for the 2014 edition)

J. P. Lees et al., BABAR Collaboration, Phys. Rev. D 88, 071104 (2013). arXiv:1308.1151 [hep-ex]

N.A. Törnqvist, Phys. Lett. B 590, 209 (2004). hep-ph/0402237

C. Hanhart, Y.S. Kalashnikova, A.E. Kudryavtsev, A.V. Nefediev, Phys. Rev. D 76, 034007 (2007). arXiv:0704.0605 [hep-ph]

B. Aubert et al., BaBar Collaboration, Phys. Rev. D 77, 111101 (2008). arXiv:0803.2838 [hep-ex]

M. Butenschoen, Z.-G. He, B.A. Kniehl, Phys. Rev. D 88, 011501 (2013). arXiv:1303.6524 [hep-ph]

C. Meng, H. Han, K.-T. Chao, arXiv:1304.6710 [hep-ph]

M. Suzuki, Phys. Rev. D 72, 114013 (2005). hep-ph/0508258

C. Bignamini, B. Grinstein, F. Piccinini, A.D. Polosa, C. Sabelli, Phys. Rev. Lett. 103, 162001 (2009). arXiv:0906.0882 [hep-ph]

A. Esposito, F. Piccinini, A. Pilloni, A.D. Polosa, J. Mod. Phys. 4, 1569 (2013). arXiv:1305.0527 [hep-ph]

P. Artoisenet, E. Braaten, Phys. Rev. D 81, 114018 (2010). arXiv:0911.2016 [hep-ph]

P. Artoisenet, E. Braaten, Phys. Rev. D 83, 014019 (2011). arXiv:1007.2868 [hep-ph]

W.-S. Hou, Phys. Rev. D 74, 017504 (2006). hep-ph/0606016

A. Ali, C. Hambrock, I. Ahmed, M.J. Aslam, Phys. Lett. B 684, 28 (2010). arXiv:0911.2787 [hep-ph]

N.A. Törnqvist, Z. Phys. C 61, 525 (1994). hep-ph/9310247

F.-K. Guo, C. Hidalgo-Duque, J. Nieves, M.P. Valderrama, Phys. Rev. D 88, 054007 (2013). arXiv:1303.6608 [hep-ph]

M. Karliner, S. Nussinov, JHEP 1307, 153 (2013). arXiv:1304.0345 [hep-ph]

D. Gamermann, E. Oset, Phys. Rev. D 80, 014003 (2009). arXiv:0905.0402 [hep-ph]

T. Aushev, W. Bartel, A. Bondar, J. Brodzicka, T. E. Browder, P. Chang, Y. Chao, K. F. Chen et al., arXiv:1002.5012 [hep-ex]

X. H. He et al., Belle Collaboration, arXiv:1408.0504 [hep-ex]

A. Ali, W. Wang, Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 192001 (2011). arXiv:1103.4587 [hep-ph]

A. Ali, C. Hambrock, W. Wang, Phys. Rev. D 88, 054026 (2013). arXiv:1306.4470 [hep-ph]

F.-K. Guo, U.-G. Meißner, W. Wang, Commun. Theor. Phys. 61, 354 (2014). arXiv:1308.0193 [hep-ph]

F.-K. Guo, U.-G. Meißner, W. Wang, Z. Yang, JHEP 1405, 138 (2014). arXiv:1403.4032 [hep-ph]

J. Nieves, M.P. Valderrama, Phys. Rev. D 86, 056004 (2012). arXiv:1204.2790 [hep-ph]

J. Alwall, M. Herquet, F. Maltoni, O. Mattelaer, T. Stelzer, JHEP 1106, 128 (2011). arXiv:1106.0522 [hep-ph]

M. Bahr, S. Gieseke, M.A. Gigg, D. Grellscheid, K. Hamilton, O. Latunde-Dada, S. Platzer, P. Richardson et al., Eur. Phys. J. C 58, 639 (2008). arXiv:0803.0883 [hep-ph]

T. Sjostrand, S. Mrenna, P.Z. Skands, Comput. Phys. Commun. 178, 852 (2008). arXiv:0710.3820 [hep-ph]

A. Buckley, J. Butterworth, L. Lonnblad, D. Grellscheid, H. Hoeth, J. Monk, H. Schulz, F. Siegert, Comput. Phys. Commun. 184, 2803 (2013). arXiv:1003.0694 [hep-ph]

B. Aubert et al., BaBar Collaboration, Phys. Rev. Lett. 96, 052002 (2006). hep-ex/0510070

S.-K. Choi, S.L. Olsen, K. Trabelsi, I. Adachi, H. Aihara, K. Arinstein, D.M. Asner, T. Aushev et al., Phys. Rev. D 84, 052004 (2011). 1107.0163 [hep-ex]

T. Aushev et al., Belle Collaboration, Phys. Rev. D 81, 031103 (2010). 0810.0358 [hep-ex]

P. del Amo Sanchez et al., BaBar Collaboration, Phys. Rev. D 82, 011101 (2010). arXiv:1005.5190 [hep-ex]

B. Aubert et al., BaBar Collaboration, Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 132001 (2009). arXiv:0809.0042 [hep-ex]

V. Bhardwaj et al., Belle Collaboration, Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 091803 (2011). arXiv:1105.0177 [hep-ex]

G. Bauer, CDF Collaboration, Int. J. Mod. Phys. A 20, 3765 (2005). hep-ex/0409052

S. Chatrchyan et al., CMS Collaboration, Phys. Lett. B 727, 57 (2013). arXiv:1309.0250 [hep-ex]

S. Chatrchyan et al., CMS Collaboration, Phys. Lett. B 727, 101 (2013). arXiv:1303.5900 [hep-ex]

G. Li, W. Wang, Phys. Lett. B 733, 100 (2014). arXiv:1402.6463 [hep-ph]

https://twiki.cern.ch/twiki/bin/view/AtlasPublic/LuminosityPublicResults. Accessed 20 Sept 2014

https://twiki.cern.ch/twiki/bin/view/CMSPublic/LumiPublicResults. Accessed 20 Sept 2014

https://twiki.cern.ch/twiki/bin/view/Main/LHCb-Facts#Integrated\_luminosity. Accessed 20 Sept 2014

ATLAS Collaboration, arXiv:1307.7292 [hep-ex]

G. Aad et al., ATLAS Collaboration, Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 152001 (2012). arXiv:1112.5154 [hep-ex]

V. M. Abazov et al., D0 Collaboration, Phys. Rev. D 86, 031103 (2012). arXiv:1203.6034 [hep-ex]

G. Aad et al., ATLAS Collaboration, Phys. Rev. D 87, 052004 (2013). arXiv:1211.7255 [hep-ex]

Acknowledgments

FKG would like to thank Institute of Theoretical Physics of Chinese Academy of Sciences, where part of the work was done, for the hospitality. This work is supported in part by the DFG and the NSFC through funds provided to the Sino-German CRC 110 “Symmetries and the Emergence of Structure in QCD”, and by the NSFC (Grant No. 11165005). We also acknowledge the support of the European Community-Research Infrastructure Integrating Activity “Study of Strongly Interacting Matter” (acronym HadronPhysics3, Grant Agreement no. 283286) under the Seventh Framework Programme of EU. Tabulated results of the distributions for \(pp/\bar{p}\rightarrow B^{(*)}\bar{B}^*\) and \(pp/\bar{p}\rightarrow D^{(*)}\bar{D}^*\) can be found at: http://www.itkp.uni-bonn.de/~weiwang/hadronLHC.shtml.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits any use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

Funded by SCOAP3 / License Version CC BY 4.0.

About this article

Cite this article

Guo, FK., Meißner, UG., Wang, W. et al. Production of the bottom analogs and the spin partner of the X(3872) at hadron colliders. Eur. Phys. J. C 74, 3063 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1140/epjc/s10052-014-3063-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1140/epjc/s10052-014-3063-4