Abstract

The luminosity calibration for the ATLAS detector at the LHC during pp collisions at \(\sqrt{s} = 7~\mathrm{TeV}\) in 2010 and 2011 is presented. Evaluation of the luminosity scale is performed using several luminosity-sensitive detectors, and comparisons are made of the long-term stability and accuracy of this calibration applied to the pp collisions at \(\sqrt{s} = 7~\mathrm{TeV}\). A luminosity uncertainty of \(\delta\mathcal{L}/ \mathcal{L} = \pm 3.5~\%\) is obtained for the 47 pb−1 of data delivered to ATLAS in 2010, and an uncertainty of \(\delta\mathcal{L}/ \mathcal{L} = \pm1.8~\%\) is obtained for the 5.5 fb−1 delivered in 2011.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

An accurate measurement of the delivered luminosity is a key component of the ATLAS [1] physics programme. For cross-section measurements, the uncertainty on the delivered luminosity is often one of the major systematic uncertainties. Searches for, and eventual discoveries of, new physical phenomena beyond the Standard Model also rely on accurate information about the delivered luminosity to evaluate background levels and determine sensitivity to the signatures of new phenomena.

This paper describes the measurement of the luminosity delivered to the ATLAS detector at the LHC in pp collisions at a centre-of-mass energy of \(\sqrt{s}=7~\mathrm{TeV}\) during 2010 and 2011. The analysis is an evolution of the process documented in the initial ATLAS luminosity publication [2] and includes an improved determination of the luminosity in 2010 along with a new analysis for 2011. Table 1 highlights the operational conditions of the LHC during 2010 and 2011. The peak instantaneous luminosity delivered by the LHC at the start of a fill increased from \(\mathcal{L}_{\mathrm{peak}} = 2.0 \times10^{32}\ \mathrm{cm}^{-2}\,\mathrm{s}^{-1}\) in 2010 to \(\mathcal{L}_{\mathrm{peak}} = 3.6 \times10^{33}\ \mathrm{cm}^{-2}\,\mathrm{s}^{-1}\) by the end of 2011. This increase results from both an increased instantaneous luminosity delivered per bunch crossing as well as a significant increase in the total number of bunches colliding. Figure 1 illustrates the evolution of these two parameters as a function of time. As a result of these changes in operating conditions, the details of the luminosity measurement have evolved from 2010 to 2011, although the overall methodology remains largely the same.

Average number of inelastic pp interactions per bunch crossing at the start of each LHC fill (above) and number of colliding bunches per LHC fill (below) are shown as a function of time in 2010 and 2011. The product of these two quantities is proportional to the peak luminosity at the start of each fill

The strategy for measuring and calibrating the luminosity is outlined in Sect. 2, followed in Sect. 3 by a brief description of the detectors used for luminosity determination. Each of these detectors utilizes one or more luminosity algorithms as described in Sect. 4. The absolute calibration of these algorithms using beam-separation scans is described in Sect. 5, while a summary of the systematic uncertainties on the luminosity calibration as well as the calibration results are presented in Sect. 6. Additional corrections which must be applied over the course of the 2011 data-taking period are described in Sect. 7, while additional uncertainties related to the extrapolation of the absolute luminosity calibration to the full 2010 and 2011 data samples are described in Sect. 8. The final results and uncertainties are summarized in Sect. 9.

2 Overview

The luminosity \(\mathcal{L}\) of a pp collider can be expressed as

where R inel is the rate of inelastic collisions and σ inel is the pp inelastic cross-section. For a storage ring, operating at a revolution frequency f r and with n b bunch pairs colliding per revolution, this expression can be rewritten as

where μ is the average number of inelastic interactions per bunch crossing.

As discussed in Sects. 3 and 4, ATLAS monitors the delivered luminosity by measuring the observed interaction rate per crossing, μ vis, independently with a variety of detectors and using several different algorithms. The luminosity can then be written as

where σ vis=εσ inel is the total inelastic cross-section multiplied by the efficiency ε of a particular detector and algorithm, and similarly μ vis=εμ. Since μ vis is an experimentally observable quantity, the calibration of the luminosity scale for a particular detector and algorithm is equivalent to determining the visible cross-section σ vis.

The majority of the algorithms used in the ATLAS luminosity determination are event counting algorithms, where each particular bunch crossing is categorized as either passing or not passing a given set of criteria designed to detect the presence of at least one inelastic pp collision. In the limit μ vis≪1, the average number of visible inelastic interactions per bunch crossing is given by the simple expression μ vis≈N/N BC where N is the number of bunch crossings (or events) passing the selection criteria that are observed during a given time interval, and N BC is the total number of bunch crossings in that same interval. As μ vis increases, the probability that two or more pp interactions occur in the same bunch crossing is no longer negligible (a condition referred to as “pile-up”), and μ vis is no longer linearly related to the raw event count N. Instead μ vis must be calculated taking into account Poisson statistics, and in some cases instrumental or pile-up-related effects. In the limit where all bunch crossings in a given time interval contain an event, the event counting algorithm no longer provides any useful information about the interaction rate.

An alternative approach, which is linear to higher values of μ vis but requires control of additional systematic effects, is that of hit counting algorithms. Rather than counting how many bunch crossings pass some minimum criteria for containing at least one inelastic interaction, in hit counting algorithms the number of detector readout channels with signals above some predefined threshold is counted. This provides more information per event, and also increases the μ vis value at which the algorithm saturates compared to an event-counting algorithm. The extreme limit of hit counting algorithms, achievable only in detectors with very fine segmentation, are particle counting algorithms, where the number of individual particles entering a given detector is counted directly. More details on how these different algorithms are defined, as well as the procedures for converting the observed event or hit rate into the visible interaction rate μ vis, are discussed in Sect. 4.

As described more fully in Sect. 5, the calibration of σ vis is performed using dedicated beam-separation scans, also known as van der Meer (vdM) scans, where the absolute luminosity can be inferred from direct measurements of the beam parameters [3, 4]. The delivered luminosity can be written in terms of the accelerator parameters as

where n 1 and n 2 are the bunch populations (protons per bunch) in beam 1 and beam 2 respectively (together forming the bunch population product), and Σ x and Σ y characterize the horizontal and vertical convolved beam widths. In a vdM scan, the beams are separated by steps of a known distance, which allows a direct measurement of Σ x and Σ y . Combining this scan with an external measurement of the bunch population product n 1 n 2 provides a direct determination of the luminosity when the beams are unseparated.

A fundamental ingredient of the ATLAS strategy to assess and control the systematic uncertainties affecting the absolute luminosity determination is to compare the measurements of several luminosity detectors, most of which use more than one algorithm to assess the luminosity. These multiple detectors and algorithms are characterized by significantly different acceptance, response to pile-up, and sensitivity to instrumental effects and to beam-induced backgrounds. In particular, since the calibration of the absolute luminosity scale is established in dedicated vdM scans which are carried out relatively infrequently (in 2011 there was only one set of vdM scans at \(\sqrt{s} = 7~\mathrm{TeV}\) for the entire year), this calibration must be assumed to be constant over long periods and under different machine conditions. The level of consistency across the various methods, over the full range of single-bunch luminosities and beam conditions, and across many months of LHC operation, provides valuable cross-checks as well as an estimate of the detector-related systematic uncertainties. A full discussion of these is presented in Sects. 6–8.

The information needed for most physics analyses is an integrated luminosity for some well-defined data sample. The basic time unit for storing luminosity information for physics use is the Luminosity Block (LB). The boundaries of each LB are defined by the ATLAS Central Trigger Processor (CTP), and in general the duration of each LB is one minute. Trigger configuration changes, such as prescale changes, can only happen at luminosity block boundaries, and data are analysed under the assumption that each luminosity block contains data taken under uniform conditions, including luminosity. The average luminosity for each detector and algorithm, along with a variety of general ATLAS data quality information, is stored for each LB in a relational database. To define a data sample for physics, quality criteria are applied to select LBs where conditions are acceptable, then the average luminosity in that LB is multiplied by the LB duration to provide the integrated luminosity delivered in that LB. Additional corrections can be made for trigger deadtime and trigger prescale factors, which are also recorded on a per-LB basis. Adding up the integrated luminosity delivered in a specific set of luminosity blocks provides the integrated luminosity of the entire data sample.

3 Luminosity detectors

This section provides a description of the detector subsystems used for luminosity measurements. The ATLAS detector is discussed in detail in Ref. [1]. The first set of detectors uses either event or hit counting algorithms to measure the luminosity on a bunch-by-bunch basis. The second set infers the total luminosity (summed over all bunches) by monitoring detector currents sensitive to average particle rates over longer time scales. In each case, the detector descriptions are arranged in order of increasing magnitude of pseudorapidity.Footnote 1

The Inner Detector is used to measure the momentum of charged particles over a pseudorapidity interval of |η|<2.5. It consists of three subsystems: a pixel detector, a silicon microstrip tracker, and a transition-radiation straw-tube tracker. These detectors are located inside a solenoidal magnet that provides a 2 T axial field. The tracking efficiency as a function of transverse momentum (p T), averaged over all pseudorapidity, rises from 10 % at 100 MeV to around 86 % for p T above a few GeV [5, 6]. The main application of the Inner Detector for luminosity measurements is to detect the primary vertices produced in inelastic pp interactions.

To provide efficient triggers at low instantaneous luminosity (\(\mathcal {L} < 10^{33}~{\rm cm}^{-2}\,{\rm s}^{-1}\)), ATLAS has been equipped with segmented scintillator counters, the Minimum Bias Trigger Scintillators (MBTS). Located at z=±365 cm from the nominal interaction point (IP), and covering a rapidity range 2.09<|η|<3.84, the main purpose of the MBTS system is to provide a trigger on minimum collision activity during a pp bunch crossing. Light emitted by the scintillators is collected by wavelength-shifting optical fibers and guided to photomultiplier tubes. The MBTS signals, after being shaped and amplified, are fed into leading-edge discriminators and sent to the trigger system. The MBTS detectors are primarily used for luminosity measurements in early 2010, and are no longer used in the 2011 data.

The Beam Conditions Monitor (BCM) consists of four small diamond sensors, approximately 1 cm2 in cross-section each, arranged around the beampipe in a cross pattern on each side of the IP, at a distance of z=±184 cm. The BCM is a fast device originally designed to monitor background levels and issue beam-abort requests when beam losses start to risk damaging the Inner Detector. The fast readout of the BCM also provides a bunch-by-bunch luminosity signal at |η|=4.2 with a time resolution of ≃0.7 ns. The horizontal and vertical pairs of BCM detectors are read out separately, leading to two luminosity measurements labelled BCMH and BCMV respectively. Because the acceptances, thresholds, and data paths may all have small differences between BCMH and BCMV, these two measurements are treated as being made by independent devices for calibration and monitoring purposes, although the overall response of the two devices is expected to be very similar. In the 2010 data, only the BCMH readout is available for luminosity measurements, while both BCMH and BCMV are available in 2011.

LUCID is a Cherenkov detector specifically designed for measuring the luminosity. Sixteen mechanically polished aluminium tubes filled with \({\rm C}_{4}{\rm F}_{10}\) gas surround the beampipe on each side of the IP at a distance of 17 m, covering the pseudorapidity range 5.6<|η|<6.0. The Cherenkov photons created by charged particles in the gas are reflected by the tube walls until they reach photomultiplier tubes (PMTs) situated at the back end of the tubes. Additional Cherenkov photons are produced in the quartz window separating the aluminium tubes from the PMTs. The Cherenkov light created in the gas typically produces 60–70 photoelectrons per incident charged particle, while the quartz window adds another 40 photoelectrons to the signal. If one of the LUCID PMTs produces a signal over a preset threshold (equivalent to ≃15 photoelectrons), a “hit” is recorded for that tube in that bunch crossing. The LUCID hit pattern is processed by a custom-built electronics card which contains Field Programmable Gate Arrays (FPGAs). This card can be programmed with different luminosity algorithms, and provides separate luminosity measurements for each LHC bunch crossing.

Both BCM and LUCID are fast detectors with electronics capable of making statistically precise luminosity measurements separately for each bunch crossing within the LHC fill pattern with no deadtime. These FPGA-based front-end electronics run autonomously from the main data acquisition system, and in particular are not affected by any deadtime imposed by the CTP.Footnote 2

The Inner Detector vertex data and the MBTS data are components of the events read out through the data acquisition system, and so must be corrected for deadtime imposed by the CTP in order to measure delivered luminosity. Normally this deadtime is below 1 %, but can occasionally be larger. Since not every inelastic collision event can be read out through the data acquisition system, the bunch crossings are sampled with a random or minimum bias trigger. While the triggered events uniformly sample every bunch crossing, the trigger bandwidth devoted to random or minimum bias triggers is not large enough to measure the luminosity separately for each bunch pair in a given LHC fill pattern during normal physics operations. For special running conditions such as the vdM scans, a custom trigger with partial event readout has been introduced in 2011 to record enough events to allow bunch-by-bunch luminosity measurements from the Inner Detector vertex data.

In addition to the detectors listed above, further luminosity-sensitive methods have been developed which use components of the ATLAS calorimeter system. These techniques do not identify particular events, but rather measure average particle rates over longer time scales.

The Tile Calorimeter (TileCal) is the central hadronic calorimeter of ATLAS. It is a sampling calorimeter constructed from iron plates (absorber) and plastic tile scintillators (active material) covering the pseudorapidity range |η|<1.7. The detector consists of three cylinders, a central long barrel and two smaller extended barrels, one on each side of the long barrel. Each cylinder is divided into 64 slices in ϕ (modules) and segmented into three radial sampling layers. Cells are defined in each layer according to a projective geometry, and each cell is connected by optical fibers to two photomultiplier tubes. The current drawn by each PMT is monitored by an integrator system which is sensitive to currents from 0.1 nA to 1.2 mA with a time constant of 10 ms. The current drawn is proportional to the total number of particles interacting in a given TileCal cell, and provides a signal proportional to the total luminosity summed over all the colliding bunches present at a given time.

The Forward Calorimeter (FCal) is a sampling calorimeter that covers the pseudorapidity range 3.2<|η|<4.9 and is housed in the two endcap cryostats along with the electromagnetic endcap and the hadronic endcap calorimeters. Each of the two FCal modules is divided into three longitudinal absorber matrices, one made of copper (FCal-1) and the other two of tungsten (FCal-2/3). Each matrix contains tubes arranged parallel to the beam axis filled with liquid argon as the active medium. Each FCal-1 matrix is divided into 16 \(\rm\phi\)-sectors, each of them fed by four independent high-voltage lines. The high voltage on each sector is regulated to provide a stable electric field across the liquid argon gaps and, similar to the TileCal PMT currents, the currents provided by the FCal-1 high-voltage system are directly proportional to the average rate of particles interacting in a given FCal sector.

4 Luminosity algorithms

This section describes the algorithms used by the luminosity-sensitive detectors described in Sect. 3 to measure the visible interaction rate per bunch crossing, μ vis. Most of the algorithms used do not measure μ vis directly, but rather measure some other rate which can be used to determine μ vis.

ATLAS primarily uses event counting algorithms to measure luminosity, where a bunch crossing is said to contain an “event” if the criteria for a given algorithm to observe one or more interactions are satisfied. The two main algorithm types being used are EventOR (inclusive counting) and EventAND (coincidence counting). Additional algorithms have been developed using hit counting and average particle rate counting, which provide a cross-check of the linearity of the event counting techniques.

4.1 Interaction rate determination

Most of the primary luminosity detectors consist of two symmetric detector elements placed in the forward (“A”) and backward (“C”) direction from the interaction point. For the LUCID, BCM, and MBTS detectors, each side is further segmented into a discrete number of readout segments, typically arranged azimuthally around the beampipe, each with a separate readout channel. For event counting algorithms, a threshold is applied to the analoge signal output from each readout channel, and every channel with a response above this threshold is counted as containing a “hit”.

In an EventOR algorithm, a bunch crossing is counted if there is at least one hit on either the A side or the C side. Assuming that the number of interactions in a bunch crossing can be described by a Poisson distribution, the probability of observing an OR event can be computed as

Here the raw event count N OR is the number of bunch crossings, during a given time interval, in which at least one pp interaction satisfies the event-selection criteria of the OR algorithm under consideration, and N BC is the total number of bunch crossings during the same interval. Solving for μ vis in terms of the event counting rate yields:

In the case of an EventAND algorithm, a bunch crossing is counted if there is at least one hit on both sides of the detector. This coincidence condition can be satisfied either from a single pp interaction or from individual hits on either side of the detector from different pp interactions in the same bunch crossing. Assuming equal acceptance for sides A and C, the probability of recording an AND event can be expressed as

This relationship cannot be inverted analytically to determine \(\mu _{\mathrm{vis}}^{\mathrm{AND}}\) as a function of N AND/N BC so a numerical inversion is performed instead.

When μ vis≫1, event counting algorithms lose sensitivity as fewer and fewer events in a given time interval have bunch crossings with zero observed interactions. In the limit where N/N BC=1, it is no longer possible to use event counting to determine the interaction rate μ vis, and more sophisticated techniques must be used. One example is a hit counting algorithm, where the number of hits in a given detector is counted rather than just the total number of events. This provides more information about the interaction rate per event, and increases the luminosity at which the algorithm saturates.

Under the assumption that the number of hits in one pp interaction follows a Binomial distribution and that the number of interactions per bunch crossing follows a Poisson distribution, one can calculate the average probability to have a hit in one of the detector channels per bunch crossing as

where N HIT and N BC are the total numbers of hits and bunch crossings during a time interval, and N CH is the number of detector channels. The expression above enables \(\mu_{\mathrm{vis}}^{\mathrm{HIT}}\) to be calculated from the number of hits as

Hit counting is used to analyse the LUCID response (N CH=30) only in the high-luminosity data taken in 2011. The lower acceptance of the BCM detector allows event counting to remain viable for all of 2011. The binomial assumption used to derive Eq. (9) is only true if the probability to observe a hit in a single channel is independent of the number of hits observed in the other channels. A study of the LUCID hit distributions shows that this is not a correct assumption, although the data presented in Sect. 8 also show that Eq. (9) provides a good description of how \(\mu_{\mathrm{vis}}^{\mathrm{HIT}}\) depends on the average number of hits.

An additional type of algorithm that can be used is a particle counting algorithm, where some observable is directly proportional to the number of particles interacting in the detector. These should be the most linear of all of the algorithm types, and in principle the interaction rate is directly proportional to the particle rate. As discussed below, the TileCal and FCal current measurements are not exactly particle counting algorithms, as individual particles are not counted, but the measured currents should be directly proportional to luminosity. Similarly, the number of primary vertices is directly proportional to the luminosity, although the vertex reconstruction efficiency is significantly affected by pile-up as discussed below.

4.2 Online algorithms

The two main luminosity detectors used are LUCID and BCM. Each of these is equipped with customized FPGA-based readout electronics which allow the luminosity algorithms to be applied “online” in real time. These electronics provide fast diagnostic signals to the LHC (within a few seconds), in addition to providing luminosity measurements for physics use. Each colliding bunch pair can be identified numerically by a Bunch-Crossing Identifier (BCID) which labels each of the 3564 possible 25 ns slots in one full revolution of the nominal LHC fill pattern. The online algorithms measure the delivered luminosity independently in each BCID.

For the LUCID detector, the two main algorithms are the inclusive LUCID_EventOR and the coincidence LUCID_EventAND. In each case, a hit is defined as a PMT signal above a predefined threshold which is set lower than the average single-particle response. There are two additional algorithms defined, LUCID_EventA and LUCID_EventC, which require at least one hit on either the A or C side respectively. Events passing these LUCID_EventA and LUCID_EventC algorithms are subsets of the events passing the LUCID_EventOR algorithm, and these single-sided algorithms are used primarily to monitor the stability of the LUCID detector. There is also a LUCID_HitOR hit counting algorithm which has been employed in the 2011 running to cross-check the linearity of the event counting algorithms at high values of μ vis.

For the BCM detector, there are two independent readout systems (BCMH and BCMV). A hit is defined as a single sensor with a response above the noise threshold. Inclusive OR and coincidence AND algorithms are defined for each of these independent readout systems, for a total of four BCM algorithms.

4.3 Offline algorithms

Additional offline analyses have been performed which rely on the MBTS and the vertexing capabilities of the Inner Detector. These offline algorithms use data triggered and read out through the standard ATLAS data acquisition system, and do not have the necessary rate capability to measure luminosity independently for each BCID under normal physics conditions. Instead, these algorithms are typically used as cross-checks of the primary online algorithms under special running conditions, where the trigger rates for these algorithms can be increased.

The MBTS system is used for luminosity measurements only for the data collected in the 2010 run before 150 ns bunch train operation began. Events are triggered by the L1_MBTS_1 trigger which requires at least one hit in any of the 32 MBTS counters (which is equivalent to an inclusive MBTS_EventOR requirement). In addition to the trigger requirement, the MBTS_Timing analysis uses the time measurement of the MBTS detectors to select events where the time difference between the average hit times on the two sides of the MBTS satisfies |Δt|<10 ns. This requirement is effective in rejecting beam-induced background events, as the particles produced in these events tend to traverse the detector longitudinally resulting in large values of |Δt|, while particles coming from the interaction point produce values of |Δt|≃0. To form a Δt value requires at least one hit on both sides of the IP, and so the MBTS_Timing algorithm is in fact a coincidence algorithm.

Additional algorithms have been developed which are based on reconstructing interaction vertices formed by tracks measured in the Inner Detector. In 2010, the events were triggered by the L1_MBTS_1 trigger. The 2010 algorithm counts events with at least one reconstructed vertex, with at least two tracks with p T>100 MeV. This “primary vertex event counting” (PrimVtx) algorithm is fundamentally an inclusive event-counting algorithm, and the conversion from the observed event rate to μ vis follows Eq. (5).

The 2011 vertexing algorithm uses events from a trigger which randomly selects crossings from filled bunch pairs where collisions are possible. The average number of visible interactions per bunch crossing is determined by counting the number of reconstructed vertices found in each bunch crossing (Vertex). The vertex selection criteria in 2011 were changed to require five tracks with p T>400 MeV while also requiring tracks to have a hit in any active pixel detector module along their path.

Vertex counting suffers from nonlinear behaviour with increasing interaction rates per bunch crossing, primarily due to two effects: vertex masking and fake vertices. Vertex masking occurs when the vertex reconstruction algorithm fails to resolve nearby vertices from separate interactions, decreasing the vertex reconstruction efficiency as the interaction rate increases. A data-driven correction is derived from the distribution of distances in the longitudinal direction (Δz) between pairs of reconstructed vertices. The measured distribution of longitudinal positions (z) is used to predict the expected Δz distribution of pairs of vertices if no masking effect was present. Then, the difference between the expected and observed Δz distributions is related to the number of vertices lost due to masking. The procedure is checked with simulation for self-consistency at the sub-percent level, and the magnitude of the correction reaches up to +50 % over the range of pile-up values in 2011 physics data. Fake vertices result from a vertex that would normally fail the requirement on the minimum number of tracks, but additional tracks from a second nearby interaction are erroneously assigned so that the resulting reconstructed vertex satisfies the selection criteria. A correction is derived from simulation and reaches −10 % in 2011. Since the 2010 PrimVtx algorithm requirements are already satisfied with one reconstructed vertex, vertex masking has no effect, although a correction must still be made for fake vertices.

4.4 Calorimeter-based algorithms

The TileCal and FCal luminosity determinations do not depend upon event counting, but rather upon measuring detector currents that are proportional to the total particle flux in specific regions of the calorimeters. These particle counting algorithms are expected to be free from pile-up effects up to the highest interaction rates observed in late 2011 (μ≃20).

The Tile luminosity algorithm measures PMT currents for selected cells in a region near |η|≈1.25 where the largest variations in current as a function of the luminosity are observed. In 2010, the response of a common set of cells was calibrated with respect to the luminosity measured by the LUCID_EventOR algorithm in a single ATLAS run. At the higher luminosities encountered in 2011, TileCal started to suffer from frequent trips of the low-voltage power supplies, causing the intermittent loss of current measurements from several modules. For these data, a second method is applied, based on the calibration of individual cells, which has the advantage of allowing different sets of cells to be used depending on their availability at a given time. The calibration is performed by comparing the luminosity measured by the LUCID_EventOR algorithm to the individual cell currents at the peaks of the 2011 vdM scan, as more fully described in Sect. 7.5. While TileCal does not provide an independent absolute luminosity measurement, it enables systematic uncertainties associated with both long-term stability and μ-dependence to be evaluated.

Similarly, the FCal high-voltage currents cannot be directly calibrated during a vdM scan because the total luminosity delivered in these scans remains below the sensitivity of the current-measurement technique. Instead, calibrations were evaluated for each usable HV line independently by comparing to the LUCID_EventOR luminosity for a single ATLAS run in each of 2010 and 2011. As a result, the FCal also does not provide an independently calibrated luminosity measurement, but it can be used as a systematic check of the stability and linearity of other algorithms. For both the TileCal and FCal analyses, the luminosity is assumed to be linearly proportional to the observed currents after correcting for pedestals and non-collision backgrounds.

5 Luminosity calibration

In order to use the measured interaction rate μ vis as a luminosity monitor, each detector and algorithm must be calibrated by determining its visible cross-section σ vis. The primary calibration technique to determine the absolute luminosity scale of each luminosity detector and algorithm employs dedicated vdM scans to infer the delivered luminosity at one point in time from the measurable parameters of the colliding bunches. By comparing the known luminosity delivered in the vdM scan to the visible interaction rate μ vis, the visible cross-section can be determined from Eq. (3).

To achieve the desired accuracy on the absolute luminosity, these scans are not performed during normal physics operations, but rather under carefully controlled conditions with a limited number of colliding bunches and a modest peak interaction rate (μ≲2). At \(\sqrt{s} = 7~\mathrm{TeV}\), three sets of such scans were performed in 2010 and one set in 2011. This section describes the vdM scan procedure, while Sect. 6 discusses the systematic uncertainties on this procedure and summarizes the calibration results.

5.1 Absolute luminosity from beam parameters

In terms of colliding-beam parameters, the luminosity \(\mathcal{L}\) is defined (for beams colliding with zero crossing angle) as

where n b is the number of colliding bunch pairs, f r is the machine revolution frequency (11245.5 Hz for the LHC), n 1 n 2 is the bunch population product, and \(\hat{\rho}_{1(2)}(x,y)\) is the normalized particle density in the transverse (x–y) plane of beam 1 (2) at the IP. Under the general assumption that the particle densities can be factorized into independent horizontal and vertical components, (\(\hat{\rho}(x,y)=\rho_{x}(x)\rho_{y}(y)\)), Eq. (10) can be rewritten as

where

is the beam-overlap integral in the x direction (with an analogous definition in the y direction). In the method proposed by van der Meer [3] the overlap integral (for example in the x direction) can be calculated as

where R x (δ) is the luminosity (or equivalently μ vis)—at this stage in arbitrary units—measured during a horizontal scan at the time the two beams are separated by the distance δ, and δ=0 represents the case of zero beam separation.

Defining the parameter Σ x as

and similarly for Σ y , the luminosity in Eq. (11) can be rewritten as

which enables the luminosity to be extracted from machine parameters by performing a vdM (beam-separation) scan. In the case where the luminosity curve R x (δ) is Gaussian, Σ x coincides with the standard deviation of that distribution. Equation (14) is quite general; Σ x and Σ y , as defined in Eq. (13), depend only upon the area under the luminosity curve, and make no assumption as to the shape of that curve.

5.2 vdM scan calibration

To calibrate a given luminosity algorithm, one can equate the absolute luminosity computed using Eq. (14) to the luminosity measured by a particular algorithm at the peak of the scan curve using Eq. (3) to get

where \(\mu^{\mathrm{MAX}}_{\mathrm{vis}}\) is the visible interaction rate per bunch crossing observed at the peak of the scan curve as measured by that particular algorithm. Equation (15) provides a direct calibration of the visible cross-section σ vis for each algorithm in terms of the peak visible interaction rate \(\mu^{\mathrm{MAX}}_{\mathrm{vis}}\), the product of the convolved beam widths Σ x Σ y , and the bunch population product n 1 n 2. As discussed below, the bunch population product must be determined from an external analysis of the LHC beam currents, but the remaining parameters are extracted directly from the analysis of the vdM scan data.

For scans performed with a crossing angle, where the beams no longer collide head-on, the formalism becomes considerably more involved [7], but the conclusions remain unaltered and Eqs. (13)–(15) remain valid. The non-zero vertical crossing angle used for some scans widens the luminosity curve by a factor that depends on the bunch length, the transverse beam size and the crossing angle, but reduces the peak luminosity by the same factor. The corresponding increase in the measured value of Σ y is exactly cancelled by the decrease in \(\mu^{\mathrm{MAX}}_{\mathrm{vis}}\), so that no correction for the crossing angle is needed in the determination of σ vis.

One useful quantity that can be extracted from the vdM scan data for each luminosity method and that depends only on the transverse beam sizes, is the specific luminosity \(\mathcal{L}_{\mathrm{spec}}\):

Comparing the specific luminosity values (i.e. the inverse product of the convolved beam sizes) measured in the same scan by different detectors and algorithms provides a direct check on the mutual consistency of the absolute luminosity scale provided by these methods.

5.3 vdM scan data sets

The beam conditions during the dedicated vdM scans are different from the conditions in normal physics fills, with fewer bunches colliding, no bunch trains, and lower bunch intensities. These conditions are chosen to reduce various systematic uncertainties in the scan procedure.

A total of five vdM scans were performed in 2010, on three different dates separated by weeks or months, and an additional two vdM scans at \(\sqrt{s} = 7~\mathrm{TeV}\) were performed in 2011 on the same day to calibrate the absolute luminosity scale. As shown in Table 2, the scan parameters evolved from the early 2010 scans where single bunches and very low bunch charges were used. The final set of scans in 2010 and the scans in 2011 were more similar, as both used close-to-nominal bunch charges, more than one bunch colliding, and typical peak μ values in the range 1.3–2.3.

Generally, each vdM scan consists of two separate beam scans, one where the beams are separated by up to ±6σ b in the x direction keeping the beams centred in y, and a second where the beams are separated in the y direction with the beams centred in x, where σ b is the transverse size of a single beam. The beams are moved in a certain number of scan steps, then data are recorded for 20–30 seconds at each step to obtain a statistically significant measurement in each luminosity detector under calibration. To help assess experimental systematic uncertainties in the calibration procedure, two sets of identical vdM scans are usually taken in short succession to provide two independent calibrations under similar beam conditions. In 2011, a third scan was performed with the beams separated by 160 μm in the non-scanning plane to constrain systematic uncertainties on the factorization assumption as discussed in Sect. 6.1.11.

Since the luminosity can be different for each colliding bunch pair, both because the beam sizes can vary bunch-to-bunch but also because the bunch population product n 1 n 2 can vary at the level of 10–20 %, the determination of Σ x/y and the measurement of \(\mu^{\mathrm{MAX}}_{\mathrm{vis}}\) at the scan peak must be performed independently for each colliding BCID. As a result, the May 2011 scan provides 14 independent measurements of σ vis within the same scan, and the October 2010 scan provides 6. The agreement among the σ vis values extracted from these different BCIDs provides an additional consistency check for the calibration procedure.

5.4 vdM scan analysis

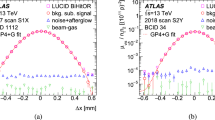

For each algorithm being calibrated, the vdM scan data are analysed in a very similar manner. For each BCID, the specific visible interaction rate μ vis/(n 1 n 2) is measured as a function of the “nominal” beam separation, i.e. the separation specified by the LHC control system for each scan step. The specific interaction rate is used so that the result is not affected by the change in beam currents over the duration of the scan. An example of the vdM scan data for a single BCID from scan VII in the horizontal plane is shown in Fig. 2.

Specific visible interaction rate versus nominal beam separation for the BCMH_EventOR algorithm during scan VII in the horizontal plane for BCID 817. The residual deviation of the data from the Gaussian plus constant term fit, normalized at each point to the statistical uncertainty (σ data), is shown in the bottom panel

The value of μ vis is determined from the raw event rate using the analytic function described in Sect. 4.1 for the inclusive EventOR algorithms. The coincidence EventAND algorithms are more involved, and a numerical inversion is performed to determine μ vis from the raw EventAND rate. Since the EventAND μ determination depends on \(\sigma_{\mathrm {vis}}^{\mathrm{AND}}\) as well as \(\sigma_{\mathrm{vis}}^{\mathrm{OR}}\), an iterative procedure must be employed. This procedure is found to converge after a few steps.

At each scan step, the beam separation and the visible interaction rate are corrected for beam–beam effects as described in Sect. 5.8. These corrected data for each BCID of each scan are then fitted independently to a characteristic function to provide a measurement of \(\mu^{\mathrm{MAX}}_{\mathrm{vis}}\) from the peak of the fitted function, while Σ is computed from the integral of the function, using Eq. (13). Depending upon the beam conditions, this function can be a double Gaussian plus a constant term, a single Gaussian plus a constant term, a spline function, or other variations. As described in Sect. 6, the differences between the different treatments are taken into account as a systematic uncertainty in the calibration result.

One important difference in the vdM scan analysis between 2010 and 2011 is the treatment of the backgrounds in the luminosity signals. Figure 3 shows the average BCMV_EventOR luminosity as a function of BCID during the May 2011 vdM scan. The 14 large spikes around \(\mathcal{L} \simeq3\times10^{29}\ \mathrm{cm}^{-2}\,\mathrm{s}^{-1}\) are the BCIDs containing colliding bunches. Both the LUCID and BCM detectors observe some small activity in the BCIDs immediately following a collision which tends to die away to some baseline value with several different time constants. This “afterglow” is most likely caused by photons from nuclear de-excitation, which in turn is induced by the hadronic cascades initiated by pp collision products. The level of the afterglow background is observed to be proportional to the luminosity in the colliding BCIDs, and in the vdM scans this background can be estimated by looking at the luminosity signal in the BCID immediately preceding a colliding bunch pair. A second background contribution comes from activity correlated with the passage of a single beam through the detector. This “single-beam” background, seen in Fig. 3 as the numerous small spikes at the 1026 cm−2 s−1 level, is likely a combination of beam-gas interactions and halo particles which intercept the luminosity detectors in time with the main beam. It is observed that this single-beam background is proportional to the bunch charge present in each bunch, and can be considerably different for beams 1 and 2, but is otherwise uniform for all bunches in a given beam. The single-beam background underlying a collision BCID can be estimated by measuring the single-beam backgrounds in unpaired bunches and correcting for the difference in bunch charge between the unpaired and colliding bunches. Adding the single-beam backgrounds measured for beams 1 and 2 then gives an estimate for the single-beam background present in a colliding BCID. Because the single-beam background does not depend on the luminosity, this background can dominate the observed luminosity response when the beams are separated.

Average observed luminosity per BCID from BCMV_EventOR in the May 2011 vdM scan. In addition to the 14 large spikes in the BCIDs where two bunches are colliding, induced “afterglow” activity can also be seen in the following BCIDs. Single-beam background signals are also observed in BCIDs corresponding to unpaired bunches (24 in each beam)

In 2010, these background sources were accounted for by assuming that any constant term fitted to the observed scan curve is the result of luminosity-independent background sources, and has not been included as part of the luminosity integrated to extract Σ x or Σ y . In 2011, a more detailed background subtraction is first performed to correct each BCID for afterglow and single-beam backgrounds, then any remaining constant term observed in the scan curve has been treated as a broad luminosity signal which contributes to the determination of Σ.

The combination of one x scan and one y scan is the minimum needed to perform a measurement of σ vis. The average value of \(\mu^{\mathrm{MAX}}_{\mathrm{vis}}\) between the two scan planes is used in the determination of σ vis, and the correlation matrix from each fit between \(\mu^{\mathrm{MAX}}_{\mathrm{vis}}\) and Σ is taken into account when evaluating the statistical uncertainty.

Each BCID should measure the same σ vis value, and the average over all BCIDs is taken as the σ vis measurement for that scan. Any variation in σ vis between BCIDs, as well as between scans, reflects the reproducibility and stability of the calibration procedure during a single fill.

Figure 4 shows the σ vis values determined for LUCID_EventOR separately by BCID and by scan in the May 2011 scans. The RMS variation seen between the σ vis results measured for different BCIDs is 0.4 % for scan VII and 0.3 % for scan VIII. The BCID-averaged σ vis values found in scans VII and VIII agree to 0.5 % (or better) for all four LUCID algorithms. Similar data for the BCMV_EventOR algorithm are shown in Fig. 5. Again an RMS variation between BCIDs of up to 0.55 % is seen, and a difference between the two scans of up to 0.67 % is observed for the BCM_EventOR algorithms. The agreement in the BCM_EventAND algorithms is worse, with an RMS around 1 %, although these measurements also have significantly larger statistical errors.

Measured σ vis values for LUCID_EventOR by BCID for scans VII and VIII. The error bars represent statistical errors only. The vertical lines indicate the weighted average over BCIDs for scans VII and VIII separately. The shaded band indicates a ±0.9 % variation from the average, which is the systematic uncertainty evaluated from the per-BCID and per-scan σ vis consistency

Measured σ vis values for BCMV_EventOR by BCID for scans VII and VIII. The error bars represent statistical errors only. The vertical lines indicate the weighted average over BCIDs for Scans VII and VIII separately. The shaded band indicates a ±0.9 % variation from the average, which is the systematic uncertainty evaluated from the per-BCID and per-scan σ vis consistency

Similar features are observed in the October 2010 scan, where the σ vis results measured for different BCIDs, and the BCID-averaged σ vis value found in scans IV and V agree to 0.3 % for LUCID_EventOR and 0.2 % for LUCID_EventAND. The BCMH_EventOR results agree between BCIDs and between the two scans at the 0.4 % level, while the BCMH_EventAND calibration results are consistent within the larger statistical errors present in this measurement.

5.5 Internal scan consistency

The variation between the measured σ vis values by BCID and between scans quantifies the stability and reproducibility of the calibration technique. Comparing Figs. 4 and 5 for the May 2011 scans, it is clear that some of the variation seen in σ vis is not statistical in nature, but rather is correlated by BCID. As discussed in Sect. 6, the RMS variation of σ vis between BCIDs within a given scan is taken as a systematic uncertainty in the calibration technique, as is the reproducibility of σ vis between scans. The yellow band in these figures, which represents a range of ±0.9 %, shows the quadrature sum of these two systematic uncertainties. Similar results are found in the final scans taken in 2010, although with only 6 colliding bunch pairs there are fewer independent measurements to compare.

Further checks can be made by considering the distribution of \(\mathcal {L}_{\mathrm{\mathrm{spec}}}\) defined in Eq. (16) for a given BCID as measured by different algorithms. Since this quantity depends only on the convolved beam sizes, consistent results should be measured by all methods for a given scan. Figure 6 shows the measured \(\mathcal{L}_{\mathrm{\mathrm {spec}}}\) values by BCID and scan for LUCID and BCMV algorithms, as well as the ratio of these values in the May 2011 scans. Bunch-to-bunch variations of the specific luminosity are typically 5–10 %, reflecting bunch-to-bunch differences in transverse emittance also seen during normal physics fills. For each BCID, however, all algorithms are statistically consistent. A small systematic reduction in \(\mathcal{L}_{\mathrm{spec}}\) can be observed between scans VII and VIII, which is due to emittance growth in the colliding beams.

Specific luminosity determined by BCMV and LUCID per BCID for scans VII and VIII. The figure on the top shows the specific luminosity values determined by BCMV_EventOR and LUCID_EventOR, while the figure on the bottom shows the ratios of these values. The vertical lines indicate the weighted average over BCIDs for scans VII and VIII separately. The error bars represent statistical uncertainties only

Figures 7 and 8 show the Σ x and Σ y values determined by the BCM algorithms during scans VII and VIII, and for each BCID a clear increase can be seen with time. This emittance growth can also be seen clearly as a reduction in the peak specific interaction rate \(\mu_{\mathrm{vis}}^{\mathrm{MAX}}/(n_{1} n_{2})\) shown in Fig. 9 for BCMV_EventOR. Here the peak rate is shown for each of the four individual horizontal and vertical scans, and a monotonic decrease in rate is generally observed as each individual scan curve is recorded. The fact that the σ vis values are consistent between scan VII and scan VIII demonstrates that to first order the emittance growth cancels out of the measured luminosity calibration factors. The residual uncertainty associated with emittance growth is discussed in Sect. 6.

5.6 Bunch population determination

The dominant systematic uncertainty on the 2010 luminosity calibration, and a significant uncertainty on the 2011 calibration, is associated with the determination of the bunch population product (n 1 n 2) for each colliding BCID. Since the luminosity is calibrated on a bunch-by-bunch basis for the reasons described in Sect. 5.3, the bunch population per BCID is necessary to perform this calibration. Measuring the bunch population product separately for each BCID is also unavoidable as only a subset of the circulating bunches collide in ATLAS (14 out of 38 during the 2011 scan).

The bunch population measurement is performed by the LHC Bunch Current Normalization Working Group (BCNWG) and has been described in detail in Refs. [8, 9] for 2010 and Refs. [10–12] for 2011. A brief summary of the analysis is presented here, along with the uncertainties on the bunch population product. The relative uncertainty on the bunch population product (n 1 n 2) is shown in Table 3 for the vdM scan fills in 2010 and 2011.

The bunch currents in the LHC are determined by eight Bunch Current Transformers (BCTs) in a multi-step process due to the different capabilities of the available instrumentation. Each beam is monitored by two identical and redundant DC current transformers (DCCT) which are high-accuracy devices but do not have any ability to separate individual bunch populations. Each beam is also monitored by two fast beam-current transformers (FBCT) which have the ability to measure bunch currents individually for each of the 3564 nominal 25 ns slots in each beam. The relative fraction of the total current in each BCID can be determined from the FBCT system, but this relative measurement must be normalized to the overall current scale provided by the DCCT. Additional corrections are made for any out-of-time charge that may be present in a given BCID but not colliding at the interaction point.

The DCCT baseline offset is the dominant uncertainty on the bunch population product in early 2010. The DCCT is known to have baseline drifts for a variety of reasons including temperature effects, mechanical vibrations, and electromagnetic pick-up in cables. For each vdM scan fill the baseline readings for each beam (corresponding to zero current) must be determined by looking at periods with no beam immediately before and after each fill. Because the baseline offsets vary by at most ±0.8×109 protons in each beam, the relative uncertainty from the baseline determination decreases as the total circulating currents go up. So while this is a significant uncertainty in scans I–III, for the remaining scans which were taken at higher beam currents, this uncertainty is negligible.

In addition to the baseline correction, the absolute scale of the DCCT must be understood. A precision current source with a relative accuracy of 0.1 % is used to calibrate the DCCT system at regular intervals, and the peak-to-peak variation of the measurements made in 2010 is used to set an uncertainty on the bunch current product of ±2.7 %. A considerably more detailed analysis has been performed on the 2011 DCCT data as described in Ref. [10]. In particular, a careful evaluation of various sources of systematic uncertainties and dedicated measurements to constrain these sources results in an uncertainty on the absolute DCCT scale in 2011 of 0.2 %.

Since the DCCT can measure only the total bunch population in each beam, the FBCT is used to determine the relative fraction of bunch population in each BCID, such that the bunch population product colliding in a particular BCID can be determined. To evaluate possible uncertainties in the bunch-to-bunch determination, checks are made by comparing the FBCT measurements to other systems which have sensitivity to the relative bunch population, including the ATLAS beam pick-up timing system. As described in Ref. [11], the agreement between the various determinations of the bunch population is used to determine an uncertainty on the relative bunch population fraction. This uncertainty is significantly smaller for 2011 because of a more sophisticated analysis, that exploits the consistency requirement that the visible cross-section be bunch-independent.

Additional corrections to the bunch-by-bunch fraction are made to correct for “ghost charge” and “satellite bunches”. Ghost charge refers to protons that are present in nominally empty BCIDs at a level below the FBCT threshold (and hence invisible), but still contribute to the current measured by the more precise DCCT. Satellite bunches describe out-of-time protons present in collision BCIDs that are measured by the FBCT, but that remain captured in an RF-bucket at least one period (2.5 ns) away from the nominally filled LHC bucket, and as such experience only long-range encounters with the nominally filled bunches in the other beam. These corrections, as well as the associated systematic uncertainties, are described in detail in Ref. [12].

5.7 Length scale determination

Another key input to the vdM scan technique is the knowledge of the beam separation at each scan point. The ability to measure Σ x/y depends upon knowing the absolute distance by which the beams are separated during the vdM scan, which is controlled by a set of closed orbit bumpsFootnote 3 applied locally near the ATLAS IP using steering correctors. To determine this beam-separation length scale, dedicated length scale calibration measurements are performed close in time to each vdM scan set using the same collision-optics configuration at the interaction point. Length scale scans are performed by displacing the beams in collision by five steps over a range of up to ±3σ b. Because the beams remain in collision during these scans, the actual position of the luminous region can be reconstructed with high accuracy using the primary vertex position reconstructed by the ATLAS tracking detectors. Since each of the four bump amplitudes (two beams in two transverse directions) depends on different magnet and lattice functions, the distance-scale calibration scans are performed so that each of these four calibration constants can be extracted independently. These scans have verified the nominal length scale assumed in the LHC control system at the ATLAS IP at the level of ±0.3 %.

5.8 Beam–beam corrections

When charged-particle bunches collide, the electromagnetic field generated by a bunch in beam 1 distorts the individual particle trajectories in the corresponding bunch of beam 2 (and vice-versa). This so-called beam–beam interaction affects the scan data in two ways.

The first phenomenon, called dynamic β [13], arises from the mutual defocusing of the two colliding bunches: this effect is tantamount to inserting a small quadrupole at the collision point. The resulting fractional change in β ∗ (the value of the β functionFootnote 4 at the IP), or equivalently the optical demagnification between the LHC arcs and the collision point, varies with the transverse beam separation, sligthly modifying the collision rate at each scan step and thereby distorting the shape of the vdM scan curve.

Secondly, when the bunches are not exactly centred on each other in the x–y plane, their electromagnetic repulsion induces a mutual angular kick [15] that distorts the closed orbits by a fraction of a micrometer and modulates the actual transverse separation at the IP in a manner that depends on the separation itself. If left unaccounted for, these beam–beam deflections would bias the measurement of the overlap integrals in a manner that depends on the bunch parameters.

The amplitude and the beam-separation dependence of both effects depend similarly on the beam energy, the tunesFootnote 5 and the unperturbed β-functions, as well as the bunch intensities and transverse beam sizes. The dynamic evolution of β ∗ during the scan is modelled using the MAD-X optics code [16] assuming bunch parameters representative of the May 2011 vdM scan (fill 1783), and then scaled using the measured intensities and convolved beam sizes of each colliding-bunch pair. The correction function is intrinsically independent of whether the bunches collide in ATLAS only, or also at other LHC interaction points [13]. The largest β ∗ variation during the 2011 scans is about 0.9 %.

The beam–beam deflections and associated orbit distortions are calculated analytically [17] assuming elliptical Gaussian beams that collide in ATLAS only. For a typical bunch, the peak angular kick during the 2011 scans is about ±0.5 μrad, and the corresponding peak increase in relative beam separation amounts to ±0.6 μm. The MAD-X simulation is used to validate this analytical calculation, and to verify that higher-order dynamical effects (such as the orbit shifts induced at other collision points by beam–beam deflections at the ATLAS IP) result in negligible corrections to the analytical prediction.

At each scan step, the measured visible interaction rate is rescaled by the ratio of the dynamic to the unperturbed bunch-size product, and the predicted change in beam separation is added to the nominal beam separation. Comparing the results of the scan analysis in Sect. 5.4 with and without beam–beam corrections for the 2011 scans, it is found that the visible cross-sections are increased by approximately 0.4 % from the dynamic-β correction and 1.0 % from the deflection correction. The two corrections combined amount to +1.4 % for 2011, and to +2.1 % for the October 2010 scans,Footnote 6 reflecting the smaller emittances and slightly larger bunch intensities in that scan session.

5.9 vdM scan results

The calibrated visible cross-section results for the vdM scans performed in 2010 and 2011 are shown in Tables 4 and 5. There were four algorithms which were calibrated in all five 2010 scans, while the BCMH algorithms were only available in the final two scans. The BCMV algorithms were not considered for luminosity measurements in 2010. Due to changes in the hardware or algorithm details between 2010 and 2011, the σ vis values are not expected to be exactly the same in the two years.

6 Calibration uncertainties and results

This section outlines the systematic uncertainties which have been evaluated for the measurement of σ vis from the vdM calibration scans for 2010 and 2011, and summarizes the calibration results. For scans I–III, the ability to make internal cross-checks is limited due to the presence of only one colliding bunch pair in these scans, and the systematic uncertainties for these scans are unchanged from those evaluated in Ref. [18]. Starting with scans IV and V, the redundancy from having multiple bunch pairs colliding has allowed a much more detailed study of systematic uncertainties.

The five different scans taken in 2010 have different systematic uncertainties, and the combination process used to determine a single σ vis value is described in Sect. 6.2. For 2011, the two vdM scans are of equivalent quality, and the calibration results are simply averaged based on the statistical uncertainties. Tables 6 and 7 summarize the systematic uncertainties on the calibration in 2010 and 2011 respectively, while the combined calibration results are shown in Table 8.

6.1 Calibration uncertainties

6.1.1 Beam centring

If the beams are not perfectly centred in the non-scanning plane at the start of a vdM scan, the assumption that the luminosity observed at the peak is equal to the maximum head-on luminosity is not correct. In the last set of 2010 scans and the 2011 scans, the beams were centred at the beginning of the scan session, and the maximum observed non-reproducibility in relative beam position at the peak of the fitted scan curve is used to determine the uncertainty. For instance, in the 2011 scan the maximum offset is 3 μm, corresponding to a 0.1 % error on the peak instantaneous interaction rate.

6.1.2 Beam-position jitter

At each step of a scan, the actual beam separation may be affected by random deviations of the beam positions from their nominal setting. The magnitude of this potential “jitter” has been evaluated from the shifts in relative beam centring recorded during the length-scale calibration scans described in Sect. 5.7, and amounts to aproximately 0.6 μm RMS. Very similar values are observed in 2010 and 2011. The resulting systematic uncertainty on σ vis is obtained by randomly displacing each measurement point by this amount in a series of simulated scans, and taking the RMS of the resulting variations in fitted visible cross-section. This procedure yields a ±0.3 % systematic error associated with beam-positioning jitter during scans IV–VIII. For scans I–III, this is assumed to be part of the 3 % non-reproducibility uncertainty.

6.1.3 Emittance growth

The vdM scan formalism assumes that the luminosity and the convolved beam sizes Σ x/y are constant, or more precisely that the transverse emittances of the two beams do not vary significantly either in the interval between the horizontal and the associated vertical scan, or within a single x or y scan.

Emittance growth between scans would manifest itself by a slight increase of the measured value of Σ from one scan to the next. At the same time, emittance growth would decrease the peak specific luminosity in successive scans (i.e. reduce the specific visible interaction rate at zero beam separation). Both effects are clearly visible in the 2011 May scan data presented in Sect. 5.5, where Figs. 7 and 8 show the increase in Σ and Fig. 9 shows the reduction in the peak interaction rate.

In principle, when computing the visible cross-section using Eq. (15), the increase in Σ from scan to scan should exactly cancel the decrease in specific interaction rate. In practice, the cancellation is almost complete: the bunch-averaged visible cross-sections measured in scans IV–V differ by at most 0.5 %, while in scans VII–VIII the values differ by at most 0.67 %. These maximum differences are taken as estimates of the systematic uncertainties due to emittance growth.

Emittance growth within a scan would manifest itself by a very slight distortion of the scan curve. The associated systematic uncertainty determined by a toy Monte Carlo study with the observed level of emittance growth was found to be negligible.

For scans I–III, an uncertainty of 3 % was determined from the variation in the peak specific interaction rate between successive scans. This uncertainty is assumed to cover both emittance growth and other unidentified sources of non-reproducibility. Variations of such magnitude were not observed in later scans.

6.1.4 Consistency of bunch-by-bunch visible cross-sections

The calibrated σ vis value found for a given detector and algorithm should be a constant factor independent of machine conditions or BCID. Comparing the σ vis values determined by BCID in Figs. 4 and 5, however, it is clear that there is some degree of correlation between these values: the scatter observed is not entirely statistical in nature. The RMS variation of σ vis for each of the LUCID and BCM algorithms is consistently around 0.5 %, except for the BCM_EventAND algorithms, which have much larger statistical uncertainties. An additional uncertainty of ±0.55 % has been applied, corresponding to the largest RMS variation observed in either the LUCID or BCM measurements to account for this observed BCID dependence in 2011. For the 2010 scans, only scans IV–V have multiple BCIDs with collisions, and in those scans the agreement between BCIDs and between scan sessions was consistent with the statistical accuracy of the comparison. As such, no additional uncertainty beyond the 0.5 % derived for emittance growth was assigned.

6.1.5 Fit model

The vdM scan data in 2010 are analysed using a fit to a double Gaussian plus a constant background term, while for 2011 the data are first corrected for known backgrounds, then fitted to a single Gaussian plus constant term. Refitting the data with several different model assumptions including a cubic spline function and no constant term leads to different values of σ vis. The maximum variation between these different fit assumptions is used to set an uncertainty on the fit model.

6.1.6 Background subtraction

The importance of the background subtraction used in the 2011 vdM analysis is evaluated by comparing the visible cross-section measured by the BCM_EventOR algorithms when the detailed background subtraction is performed or not performed before fitting the scan curve. Half the difference (0.31 %) is adopted as a systematic uncertainty on this procedure. For scans IV–V, no dedicated background subtraction was performed and the uncertainty on the background treatment is accounted for in the fit model uncertainty, where one of the comparisons is between assuming the constant term results from luminosity-independent background sources compared to a luminosity-dependent signal.

6.1.7 Reference specific luminosity

The transverse convolved beam sizes Σ x/y measured by the vdM scan are directly related to the specific luminosity defined in Eq. (16). Since this specific luminosity is determined by the beam parameters, each detector and algorithm should measure identical values from the scan curve fits.

For simplicity, the visible cross-section value extracted from a set of vdM scans for a given detector and algorithm uses the convolved beam sizes measured by that same detector and algorithm.Footnote 7 As shown in Fig. 6, the values measured by LUCID_EventOR and BCM_EventOR are rather consistent within statistical uncertainties, although averaged over all BCIDs there may be a slight systematic difference between the two results. The difference observed between these two algorithms, after averaging over all BCIDs, results in a systematic uncertainty of 0.29 % related to the choice of specific luminosity value.

6.1.8 Length-scale calibration

The length scale of each scan step enters into the extraction of Σ x/y and hence directly affects the predicted peak luminosity during a vdM scan. The length scale calibration procedure is described in Sect. 5.7 and results in a ±0.3 % uncertainty for scans IV–VIII. For scans I–III, a less sophisticated length scale calibration procedure was performed which was more sensitive to hysteresis effects and re-centring errors resulting in a correspondingly larger systematic uncertainty of 2 %.

6.1.9 Absolute length scale of the Inner Detector

The determination of the length scale relies on comparing the scan step requested by the LHC with the actual transverse displacement of the luminous centroid measured by ATLAS. This measurement relies on the length scale of the Inner Detector tracking system (primarily the pixel detector) being correct in measuring displacements of vertex positions away from the centre of the detector. An uncertainty on this absolute length scale was evaluated by analysing Monte Carlo events simulated using several different misaligned Inner Detector geometries. These geometries represent distortions of the pixel detector which are at the extreme limits of those allowed by the data-driven alignment procedure. Samples were produced with displaced interaction points to simulate the transverse beam displacements seen in a vdM scan. The variations between the true and reconstructed vertex positions in these samples give a conservative upper bound of ±0.3 % on the uncertainty on the determination of σ vis due to the absolute length scale.

6.1.10 Beam–beam effects

For given values of the bunch intensity and transverse convolved beam sizes, which are precisely measured, the deflection-induced orbit distortion and the relative variation of β ∗ are both proportional to β ∗ itself; they also depend on the fractional tune. Assigning a ±20 % uncertainty on each β-function value at the IP and a ±0.02 upper limit on each tune variation results in a ±0.5 % (±0.7 %) uncertainty on σ vis for 2011 (2010). This uncertainty is computed under the conservative assumption that β-function and tune uncertainties are correlated between the horizontal and vertical planes, but uncorrelated between the two LHC rings; it also includes a contribution that accounts for small differences between the analytical and simulated beam–beam-induced orbit distortions.

6.1.11 Transverse correlations

The vdM formalism outlined in Sect. 5.1 explicitly assumes that the particle densities in each bunch can be factorized into independent horizontal and vertical components such that the term 1/(2πΣ x Σ y ) in Eq. (14) fully describes the overlap integral of the two beams. If the factorization assumption is violated, the convolved beam width Σ in one plane is no longer independent of the beam separation δ in the other plane, although a straightforward generalization of the vdM formalism still correctly handles an arbitrary two-dimensional luminosity distribution as a function of the transverse beam separation (δ x ,δ y ), provided this distribution is known with sufficient accuracy.

Linear x–y correlations do not invalidate the factorization assumption, but they can rotate the ellipse which describes the luminosity distribution away from the x–y scanning planes such that the measured Σ x and Σ y values no longer accurately reflect the true convolved beam widths [19]. The observed transverse displacements of the luminous region during the scans from reconstructed event vertex data directly measure this effect, and a 0.1 % upper limit on the associated systematic uncertainty is determined. This uncertainty is comparable to the upper limit on the rotation of the luminous region derived during 2010 LHC operations from measurements of the LHC lattice functions by resonant excitation, combined with emittance ratios based on wire-scanner data [20].

More general, non-linear correlations violate the factorization assumption, and additional data are used to constrain any possible bias in the luminosity calibration from this effect. These data include the event vertex distributions, where both the position and shape of the three-dimensional luminous region are measured for each scan step, and the offset scan data from scan IX, where the convolved beam widths are measured with a fixed beam–beam offset of 160 μm in the non-scanning plane. Two different analyses are performed to determine a systematic uncertainty.

First, a simulation of the collision process, starting with single-beam profiles constructed from the sum of two three-dimensional Gaussian distributions with arbitrary widths and orientations, is performed by numerically evaluating the overlap integral of the bunches. This simulation, which allows for a crossing angle in both planes, is performed for each scan step to predict the geometry of the luminous region, along with the produced luminosity. Since the position and shape of the luminous region during a beam-separation scan varies depending on the single-beam parameters [21], the simulation parameters are adjusted to provide a reasonable description of the mean and RMS width of the luminous region observed at each scan step in the May 2011 scans VII–IX (including the offset scan). Luminosity profiles are then generated for simulated vdM scans using these tuned beam parameters, and analysed in the same fashion as the real vdM scan data, which assumes factorization. The impact of a small non-factorization in the single-beam distributions is determined from the difference between the ‘true’ luminosity from the simulated overlap integral at zero beam separation and the ‘measured’ luminosity from the luminosity profile fits. This difference is 0.1–0.2 % for the May 2011 scans, depending on the fitting model used. The number of events with vertex data recorded during the 2010 vdM scans is not sufficient to perform a similar analysis for those scans.

A second approach, which does not use the luminous region data, fits the observed luminosity distributions as a function of beam separation to a number of generalized, two-dimensional functions. These functions include non-factorizable functions constructed from multiple two-dimensional Gaussian distributions with possible rotations from the scan axes, and other functions where factorization between the scan axes is explicitly imposed. By performing a combined fit to the luminosity data in the two scan planes of scan VII, plus the two scan planes in the offset scan IX, the relative difference between the non-factorizable and factorizable functions is evaluated for 2011. The resulting fractional difference on σ vis is 0.5 %. For 2010, no offset scan data are available, but a similar analysis performed on scans IV and V found a difference of 0.9 %.

The systematic uncertainty associated with transverse correlations is taken as the largest effect among the two approaches described above, to give an uncertainty of 0.5 % for 2011. For 2010, the 0.9 % uncertainty is taken as the difference between non-factorizable and factorizable fit models.

6.1.12 μ dependence

Scans IV–V were taken over a range of interactions per bunch crossing 0<μ<1.3 while scans VII–VIII covered the range 0<μ<2.6, so uncertainties on the μ correction can directly affect the evaluation of σ vis. Figure 10 shows the variation in measured luminosity as a function of μ between several algorithms and detectors in 2011, and on the basis of this agreement an uncertainty of ±0.5 % has been applied for scans IV–VIII.Footnote 8

Scans I–III were performed with μ≪1 and so uncertainties in the treatment of the μ-dependent corrections are small. A ±2 % uncertainty was assigned, however, on the basis of the agreement at low μ values between various detectors and algorithms, which were described in Ref. [2].

6.1.13 Bunch-population product

The determination of this uncertainty has been described in Sect. 5.6 and the contributions are summarized in Table 3.

6.2 Combination of 2010 scans

The five vdM scans in 2010 were taken under very different conditions and have very different systematic uncertainties. To combine the individual measurements of σ vis from the five scans to determine the best calibrated \(\overline{\sigma}_{\mathrm{vis}}\) value per algorithm, a Best Linear Unbiased Estimator (BLUE) technique has been employed taking into account both statistical and systematic uncertainties, and the appropriate correlations [23, 24]. The BLUE technique is a generalization of a χ 2 minimization, where for any set of measurements x i of a physical observable θ, the best estimate of θ can be found by minimizing

where V −1 is the inverse of the covariance matrix V, and θ is the product of the unit vector and θ.

Using the systematic uncertainties described above, including the correlations indicated in Table 6, a covariance matrix is constructed for each error source according to V ij =σ i σ j ρ ij where σ i is the uncertainty from a given source for scan i, and ρ ij is the linear correlation coefficient for that error source between scans i and j. As there are a total of five vdM scans, a 5×5 covariance matrix is determined for each source of uncertainty. These individual covariance matrices are combined to produce the complete covariance matrix, along with the statistical uncertainty shown in Table 5. While in principle, each algorithm and detector indicated in Table 5 could have different systematic uncertainties, no significant sources of systematic uncertainty have been identified which vary between algorithms. As a result, a common systematic covariance matrix has been used in all combinations.

The best estimate of the visible cross-section \(\overline{\sigma}_{\mathrm{vis}}\) for each luminosity method in 2010 is shown in Table 8 along with the uncertainty. Because the same covariance matrix is used in all combinations aside from the small statistical component, the relative weighting of the five scan points is almost identical for all methods. Here detailed results are given for the LUCID_EventOR combination. Because most of the uncorrelated uncertainties were significantly reduced from scans I–III to scans IV–V, the values from the last two vdM scans dominate the combination. Scans IV and V contribute a weight of 45 % each, while the other three scans make up the remaining 10 % of the weighted average value. The total uncertainty on the LUCID_EventOR combination represents a relative error of ±3.4 %, and is nearly identical to the uncertainty quoted for scans IV–V alone in Table 6. Applying the beam–beam corrections described in Sect. 5.8, which only affect scans IV–V in 2010, changes the best estimate of \(\overline{\sigma}_{\mathrm{vis}}\) by +1.9 % compared to making no corrections to the 2010 calibrations.

Figure 11 shows the agreement among the algorithms within each scan in 2010 by plotting the deviations of the ratios \(\sigma_{\mathrm{vis}}/\sigma_{\mathrm{vis}}(\mathrm{LUCID\_EventOR})\) for several algorithms from the mean value of these ratios, \(\overline{\sigma }_{\mathrm{vis}}/\overline{\sigma}_{\mathrm{vis}}\)(LUCID_EventOR). By construction, any variation between scans related to the bunch population product n 1 n 2 cancels out, and the remaining scatter reflects the variation between algorithms in measuring \(\mu_{\mathrm{vis}}^{\mathrm{MAX}} \varSigma _{x} \varSigma_{y}\). The observed variation is mostly consistent with the statistical uncertainties, and the observed variation of up to ±2 % is consistent with the systematic uncertainty assigned to scans I–III for μ dependence. No evidence for any additional source of significant systematic uncertainty between the algorithms is apparent.

7 Luminosity extrapolation