Abstract—The problem of vertical flow stability in an oil reservoir with a gas cap is considered, when the oil flow obeys the Brinkman equation. Boundary conditions at the moving boundary of the gas-oil interface are derived and a basic solution is obtained. The normal mode method is used to study the stability of the gas–oil interface. The obtained dispersion equation is investigated. Conditions for flow stability are found for all values of the parameters, and it is shown that, in the linear approximation, the growth rate of short-wave perturbations tends to zero with increasing wave number.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Oil reservoirs with a gas cap make up a significant proportion of gas and oil fields [1]. The extraction of oil from such fields has certain features and differs from the development of purely oil fields. Thus, a decrease in pressure in an area saturated with oil causes the boundary of the gas-oil contact to move. The movement of this interface can be unstable, which leads to gas breakthrough into the production well and the formation of immobile oil in the reservoir and near-wellbore region [2]. In other cases, instability and destruction of the gas-oil contact surface can cause flow fragmentation and the formation of residual immobile oil in the field [3]. Based on this, it can be concluded that the determining factor of many processes is the instability of filtration flows.

In recent years, analytical and numerical studies of the instability of interfaces during filtration in geothermal systems, soils, and rocks have been carried out [4–7]. In these works, the mathematical description of the filtration process in porous media was based on the Darcy’s law. It has been established that in many cases important for applications, the transition to instability occurs simultaneously for all values of the wave number or for infinitely large wave numbers. In the last case, the most rapidly growing mode of the unstable flow is the mode corresponding to an infinitely small linear size. Thus, we can conclude that the mathematical model based on the Darcy law is inapplicable for describing both the transition to instability itself and the subsequent development of the flow with the destruction of the interface, leading to the formation of “fingers.”

In [8], in the framework of the Darcy filtration theory, the stability of the gas-oil interface was studied under a pressure drop in an oil-saturated region. A criterion for the stability of the surface is found and it is shown that when the parameters change, the transition to the unstable regime occurs simultaneously for all wave numbers. It is natural to assume that the Darcy’s law, which describes well flows with a large characteristic length scale, cannot always give an adequate mathematical description of small-scale phenomena. In these cases, when studying filtration flows, instead of the Darcy law, it is proposed to use the Brinkman equation [9].

Interest in the Brinkman equation, as a generalized form of the Darcy filtration equation, arose largely as a result of attempts to formulate correct boundary conditions on the contact surface of a free fluid flow and a flow in a porous medium [10–12]. The properties of the Brinkman equation and boundary conditions on the contact surface of a free fluid and a porous medium were studied in [13, 14]. An analysis of the influence of inertial terms on the flow of a contacting free liquid and a liquid in a porous medium in the framework of the Brinkman equation is presented in [15]. In [16], the data of experiments on the stability of the interface between two miscible liquids, carried out for a vertical Hele–Shaw cell, are presented. A comparison was made with the results of studies of the linear stability of a flow subject to the Brinkman equation. In [17], the stability of a plane-parallel flow of a free fluid over a saturated porous medium was considered. A comparative analysis of the results using two approaches is given. In one case, the Brinkman model with Ochoa–Tapia–Whitaker boundary conditions was applied, and in the other case, the Darcy–Forchheimer equations with Beavers–Joseph boundary conditions were used.

The evolution of infinitely small and finite localized perturbations for a moving phase transition front was studied in [18, 19] in the Darcy approximation. The development of gravitational instability in a two-layer liquid of constant and variable viscosity in a porous medium was numerically studied in [20, 21] also using the Darcy law. The Brinkman equation was used in [22] to simulate the flow of a micropolar fluid in a porous medium.

In this paper, within the framework of the generalized Brinkman filtration equation, the stability of the gas-oil contact surface is studied with a decrease in pressure in the oil-saturated region.

1 PROBLEM FORMULATION

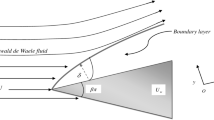

We consider the movement of oil in a porous medium for the case when a horizontal reservoir saturated with oil borders on top with a gas cap and on the bottom with a high permeability interlayer or fracture. It is assumed that the movement of oil is described by the generalized Brinkman filtration equation.

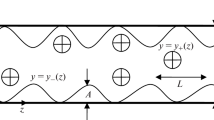

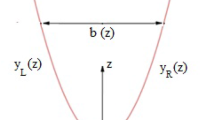

Let the lower boundary of the reservoir have a vertical Cartesian coordinate z = 0, and the upper boundary z = L. An infinite reservoir in the horizontal dimension includes the region Ωf, saturated with oil at 0 < z < S(x, t) and the region Ωg: S(x, t) < z < L, saturated with gas. We assume that the volume of the gas is large enough and its motion can be neglected, and the pressure in it is constant and equal to PG. We neglect the dissolution of gas in oil and the degassing of oil. When pumping oil from a highly permeable layer corresponding to the boundary z = 0, we assume that the pressure in it changes instantly throughout its entire length and is equal to a constant value of PF.

Oil is assumed to be incompressible, and its motion is described by the Brinkman equation, taking into account gravity

Here, P is the pressure, ρ the density, g the acceleration due to gravity, μ the dynamic viscosity, μe the effective dynamic viscosity, k the permeability, \({\kern 1pt} \vec {V}\) the filtration velocity vector.

Let us find the basic solution, which is supposed to be investigated for stability. We use the fluid incompressibility condition (1.1) and apply the divergence operation to equation (1.2). As a result, we obtain the Laplace equation for pressure

If the surface of the oil and gas contact is flat and at time t has the z-coordinate H(t) > 0, then equation (1.3), as well as boundary conditions

satisfies the solution

From equation (1.2) we have

where Vx,b and Vz,b are x- and z-components of the velocity \({\kern 1pt} \vec {V}\) of the basic solution.

If we do not consider the processes of dissolution of gas in oil and degassing of oil, then the speed of the interface in the direction of the outer normal coincides with the normal component of the filtration rate \(\vec {V}(H(t))\), therefore, for the basic solution we obtain

From (1.9) we have

where H0 is the z-coordinate of the interface at t = 0. Relation (1.10) defines an implicit function H(t).

At the interface, the condition of equality of the normal stress components is satisfied, which has the form

Here, Vn is the normal velocity component to the surface S(x, t). \(\left( {\frac{{\partial {{V}_{n}}}}{{\partial n}}} \right)\) is the derivative of this component along the normal to the surface S(x, t).

The condition for shear stress, which is equal to zero (see, for example, [23]), can be written as

where Vτ is the tangent to the surface S(x, t) of the velocity \(\overrightarrow V \) component, \(\left( {\frac{\partial }{{\partial n}}{{V}_{\tau }}} \right)\) the derivative of this component in the direction of the normal, \(\left( {\frac{\partial }{{\partial \tau }}{{V}_{n}}} \right)\) the derivative of the normal velocity component in the direction of the tangent.

2 DERIVATION OF THE DISPERSION EQUATION

In the framework of the linear approach, the unknown functions can be represented as

where p(x, z, t), u(x, z, t), \({v}\)(x, z, t), s(x, t) are the small perturbations of the pressure, horizontal and vertical velocity components, as well as the position of the oil-gas interface, respectively.

Since equation (1.3) is linear, p(x, z, t) satisfies the equation

We will look for a solution for p(x, z, t) in the form

then from equation (2.5) we obtain

We write the general solution of equation (2.6) in the form

Taking into account that perturbations arise on the free surface and decay at the lower boundary of the low-permeability layer, the second term on the right side of expression (2.8) can be neglected, then

Solutions for u(x, z, t) and \({v}\)(x, z, t) we will search in the form

Substituting (2.2), (2.3), and (2.4) in equation (1.2), and using (2.9), (2.10), (2.11) we have

where \(c = k{\text{/}}\mu \),\({{m}_{e}} = c{{\mu }_{e}}\).

For the general solution of equation (2.12)

and for the sufficiently large oil-bearing reservoir thickness, we can neglect the term on the right-hand side, which decreases with increasing z, and write the solution in the form

Similarly, from equation (2.13) we have

It follows from the liquid phase incompressibility condition (1.1) that

Using relations (2.10) and (2.11), from equation (2.16) we obtain

Substituting (2.14) and (2.15) into equation (2.17), we find an equation relating the coefficients Cu and \({{C}_{{v}}}\)

From (2.18) we get

We assume that perturbation of the front position has the form

and ∂s/∂x ≪ 1. Then, within the linear approach from (1.11) follows

Thus, the normal velocity of the interface can be found from equation

From (1.12) in the framework of linear approach we have

Using relations (2.14), (2.15), and (2.19), we transform equation (2.23) to the form

and obtain homogeneous system of equations (2.21), (2.22), (2.24) for the unknown parameters C1, \({{C}_{{v}}}\), Cη. The system has a non-trivial solution if the determinant of the matrix coefficients is zero

Here, \({{e}_{H}} = \exp (\sqrt {{{K}^{2}} + 1{\text{/}}{{m}_{e}}} H(t))\), \({{e}_{K}} = \exp \left( {KH(t)} \right)\), \({{f}_{k}} = \sqrt {{{K}^{2}} + 1{\text{/}}{{m}_{e}}} \).

From (2.25) we obtain

or

3 INVESTIGATION OF FLOW STABILITY

Within the Darcy approximation the effective viscosity μe is equal to zero, respectively me = 0, then from (2.26) we have

The condition for the unstable development of perturbations at the interface, which follows from relation (3.1), coincides with the condition obtained using the Darcy law [6, 7]. In the case of instability, when PG > PF, the perturbation amplitude tends to infinity with the growth of the wave number K → ∞.

Consider the behavior\(f{\kern 1pt} '(t)\) at K → ∞, when me ≠ 0. From (2.25) we have

Therefore, in the Brinkman approximation, the rate of damping or growth of short-wave disturbances tends to zero at K → ∞ both in the stable (PF > PG) and in the unstable (PF < PG) case.

If we use the quasi-stationary condition, which follows from the fact that the characteristic time of motion of the gas-oil interface is much greater than the characteristic time of pressure redistribution, then we can neglect the dependence of H on t on the right side of the equation (2.25) and assume that the interface is fixed. Similar conditions of quasi-stationarity are valid for many problems of filtration theory with discontinuity surfaces [3, 24]. Then we have

And relations (2.25), (3.1), and (3.2) have the forms

In Fig. 1, we demonstrate the dispersion curve Σ = Σ (K) that follows from (3.3), where dimensionless parameter \(\Sigma = \frac{{\sigma H\sqrt {{{m}_{e}}} }}{{c{{P}_{k}}}}\) depends on dimensionless wave number \(\kappa = K\sqrt {{{m}_{e}}} \) and Pk = PG – PF. It is seen that Видно, that the perturbation growth rate has a maximum, which is reached at \(K\sqrt {{{m}_{e}}} \approx 0.72\) and tends to zero with an increase in the wavenumber K → ∞.

In Fig. 2 the dimensionless perturbation growth rates for small dimensionless wave numbers is compared for the Darcy (curve 1) and Brinkman (curve 2) filtration equations. At \(K\sqrt {{{m}_{e}}} \) ≪ 1 the Darcy equation describes well the behavior of a physical system, and for large wave numbers, the error from using the Darcy law becomes significant. It follows from (3.3) that since the expression in the denominator is always positive, the transition to instability occurs when the sign of the difference between the pressure in the gas cap PG and the pressure in the high-permeability layer PF changes.

In Fig. 3 we illustrate the change in the dimensionless parameter \(\frac{{\sigma H\sqrt {{{m}_{e}}} }}{{c{{P}_{k}}}}\), which describes the growth or decay of the perturbations, on dimensionless wave number \(K\sqrt {{{m}_{e}}} \) at fixed PG and different values of PF. It can be seen that the transition to instability occurs at PG = PF simultaneously for all values of the wave number.

SUMMARY

The dynamics and stability of vertical flow in an oil reservoir with a gas cap has been studied. The oil flow was described by the generalized Brinkman filtration equation. The law of motion of a flat horizontal interface between oil and gas is presented. The normal mode method is used to study the flow stability with respect to infinitesimal perturbations of a flat boundary. It is shown that such perturbations increase if the pressure in the gas cap is higher than the pressure in the high-permeability formation from which oil is produced. If the flat interface is at rest, then the pressure in the gas cap is less than in the high-permeability layer, which is equal to the hydrostatic pressure. At the first stage of pressure reduction in the interlayer, the contact surface will begin to move downward, but will remain stable until the pressure in the interlayer drops below the pressure in the gas cap. After that, the movement of the oil-gas border will become unstable. In this case, nonlinear instability takes place for any wavelength, but depends on the wave number K in such a way that for K → ∞ and K → 0 this rate tends to zero. There is a certain value of the wave number at which the growth rate has a maximum.

When using Darcy’s law, instability also occurs if the pressure in the gas cap is greater than the pressure in the interlayer. However, in this case, the growth rate of the perturbation increases indefinitely with the decreasing perturbation wavelength. In this case, short-wave perturbations grow arbitrarily fast, which does not allow obtaining a reliable picture of the flow and indicates the inapplicability of the mathematical model based on the Darcy law to describe both the transition to instability itself and the subsequent development of the flow with the destruction of the interface, leading to the formation of fingers. The use of the generalized Brinkman filtration equation makes it possible to eliminate the anomalous nature of the evolution of short-wave disturbances, which opens up the possibility of studying problems ill-posed in terms of the Darcy approach.

The work was carried out with support from the Russian Science Foundation under the grant no. 21-11-00126.

REFERENCES

Lapuk, B.B., Theoretical foundations for the development of natural gas fields, Moscow–Izhevsk.: Institute of Computer Science, 2002 (in Russian).

Koutyrev, E.F., Shkandratov, V.V., Belousov, Yu.V., Karimov, A.A., Some results of physical modeling of gas exchange processes in an oil-injected water system, Georesources, 2008, no. 5, pp. 33–36. (in Russian)

Tsypkin, G.G., Shargatov, V.A., Influence of capillary pressure gradient on connectivity of flow through a porous medium, Int. J. Heat and Mass Transfer, 2018, vol. 127, pp. 1053–1063.

Tsypkin, G.G., Il’ichev, A.T., Gravitational stability of the water-vapor phase transition interface in geothermal systems, Transp. Porous Media, 2004, vol. 55, pp. 183–199.

Il’ichev, A.T., Tsypkin, G.G., Catastrophic transition to instability of evaporation front in a porous medium, Eur. J. Mech. B/Fluids, 2008, vol. 27, no. 6, pp. 665–677.

Shargatov, V.A., Il’ichev, A.T., Tsypkin, G.G., Dynamics and stability of moving fronts of water evaporation in a porous medium, Int. J. Heat and Mass Transfer, 2015, vol. 83, pp. 552–561.

Tsypkin, G.G., Il’ichev, A.T., Superheating of water and morphological instability of the boiling front moving in the low-permeability rock, Int. J. Heat and Mass Transfer, 2021, vol. 167, p. 120820.

Tsypkin, G.G. Instability of a light fluid over a heavy one under the motion of their interface in a porous medium, Fluid Dynamics, 2020, vol. 55, no. 2, pp. 213–219.

Brinkman H.C. A calculation of the viscous force exerted by a flowing fluid on a dense swarm of particles, Appl. Sci. Res., 1947, vol. A1, pp. 27–34.

Beavers, G.S., Joseph, D.D., Boundary conditions at a naturally permeable wall, J. Fluid Mech., 1967, vol. 30, pp. 197–207.

Ochoa-Tapia, J.A., Whitaker, S., Momentum transfer at the boundary between a porous medium and a homogeneous fluid – I. Theoretical development, Int. J. Heat Mass Transfer, 1995, vol. 38, pp. 2635–2646.

Valdes-Parada, F.J., Ochoa-Tapia, J.A., Alvarez-Ramirez, J., On the effective viscosity for the Darcy–Brinkman equation, Physica A, 2007, vol. 385, pp. 69–79.

Nield, D.A., Modelling high speed flow of a compressible fluid in a saturated porous medium, Transp. Porous Media, 1994, vol. 14, pp. 85–88.

Nield, D.A., The Beavers–Joseph boundary condition and related matters: a historical and critical note, Transp. Porous Media, 2009, vol. 78, pp. 537–540.

Tsiberkin, K., Effect of inertial terms on fluid–porous medium flow coupling, Transp. Porous Media, 2018, vol. 121, pp. 109–210.

Fernandez, J., Kurowski, P., Petitjeans, P., Meiburg, E., Density-driven unstable flows of miscible fluids in a Hele-Shaw cell, J. Fluid Mech., 2002, vol. 451, pp. 239–260.

Lyubimova, T.P., Lyubimov, D.V., Baydina, D.T., et al., Instability of plane-parallel flow of incompressible liquid over a saturated porous medium, Phys. Rev., 2016, vol. 94, p. 013104.

Il’ichev, A.T., Shargatov, V.A., Dynamics of water evaporation fronts, Comput. Math. Math. Phys., 2013, vol. 53, no. 9, pp. 1350–1370.

Shargatov, V.A., Gorkunov, S.V., Il’ichev, A.T., Dynamics of front-like water evaporation phase transition interfaces, Commun. in Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul., 2019, vol. 67, pp. 223–236.

Soboleva, E.B., Onset of Rayleigh-Taylor convection in a porous medium, Fluid Dynamics, 2021, vol. 56, no. 2, pp. 200–210.

Soboleva, E.B., Density-driven convection in an inhomogeneous geothermal reservoir, Int. J. Heat and Mass Transfer, 2018, vol. 127, pp. 784–798.

Khanukaeva, D.Yu., Filippov, A.N., Yadav, P.K., et al., Creeping flow of micropolar fluid through a swarm of cylindrical cells with porous layer (membrane), J. Mol. Liq., 2019, vol. 294, p. 111558.

Zhuravleva, E.N., Pukhnachev, V.V., A problem on a viscous layer deformation, Doklady Physics, 2020, vol. 65, no. 2, pp. 60–63.

Tsypkin, G.G., Woods, A.W., Vapour extraction from a water saturated geothermal reservoir, J. Fluid Mech., 2004, vol. 506, pp. 315–330.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Rights and permissions

Open Access. This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tsypkin, G.G., Shargatov, V.A. LINEAR STABILITY OF A FILTRATION FLOW WITH GAS–OIL INTERFACE WITHIN THE BRINKMAN APPROACH. Fluid Dyn 57, 273–280 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1134/S0015462822030156

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1134/S0015462822030156