Abstract

This project explores the potential of image-making in augmented reality (AR) technologies as means of designing sustaining quality peace futures—unfuturing peace, focusing on Ukraine’s heroic defense against Russia’s 2022–2024 full-scale war of aggression as a case study. Employing the methodology of compositional interpretation and the conceptual tool “futures images,” the project theoretically and practically differentiates between defuturing and unfuturing as peace design processes in developing an essay of originally designed marker-based Augmented Reality Posters in Support of Ukraine as demos of sustaining quality peace arrangements. The posters reference the topics of (physical) integrity of Ukrainian symbols, global food security and the security of the LGBTQI+ community in Ukraine. The technological artistic process/outcomes of this AR image-making experiment and their relation to power layouts in peacebuilding form the bases for theorizing how AR-supported futures design in war-affected communities—unfuturing peace—could facilitate “guerrilla peacebuilding.” In outlining theoretical and practical premises of guerrilla peacebuilding, the project intersects Augmented Reality Posters in Support of Ukraine with explorations of guerrilla warfare and counterinsurgency efforts leading to the 2016 Havana Peace Agreements in Colombia as well as mobile technologies/power in guerrilla approaches to democratic development.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The idea for this article and the image-making experiment it focuses on emerged when I encountered the Futuring Peace project by the Innovation Cell of the United Nations Department of Political and Peacebuilding Affairs (UN DPPA). Among an array of innovative peace-themed subprojects, Futuring Peace included the Augmented Reality Peace Posters initiative. These posters “about peacemaking and peacebuilding” were created by “a network of global artists” utilizing the augmented reality application Artivive (Futuring Peace, n.d.b). The technological aspect of the initiative allowed the artists to create “an interactive experience in a real-world environment where the objects are enhanced and blended with digital elements and information” (ibid.). Broadly, in augmented reality (AR) technologies (from smartphone applications to more advanced options including “glasses with the ability to project images into the user’s field of view”), a “[r]egular physical reality, such as an ordinary street, is augmented with virtual objects” (Chalmers 2022, p.225). One of the most popularly known examples of an AR application, although not in peace efforts, is the mobile game Pokémon Go (ibid.).

Futuring Peace emerged to “encourage interdisciplinary approaches such as futures thinking and speculative design and their practical limits to peace processes in a world of increasing complexity” (Futuring Peace, n.d.a). However, the emphasis on visualizing futures can appear contradictory to the premises of futures research—that we can imagine, predict and build knowledge about the future. Particularly, from a futures design stance, the projects’ emphasis on immersive visualizations also defutures peace (see Hiesinger 2021). Yet, this contradiction, I argue, could be made productive specifically for peacebuilding as an empowering and disruptive process of change through artistic and technological means. This leads me to work on two tasks in this project: the theoretical one and the peace-applied/methodological one.

The theoretical task of this project is in outlining what guerrilla peacebuilding could mean as an approach to pro-peace change during war and what it could mean in practice in war-affected communities, especially cases of national resistance in temporarily occupied territories. To execute this task, I theorize “unfuturing” of peace based on: existing futures research and futures design discussions of defuturing; research of mobile technologies in guerrilla democracies; and marketing insights into guerrilla warfare and counterinsurgency efforts in Colombia leading to the 2016 Havana Peace Agreements.

Within the peace-applied/methodological task, I employ the concept of “futures images” in futures research/studies and draw on image-making practices within futures design to perform a series of AR image transformations of three photographs which depict visual manifestations of supporting Ukraine during Russia’s full-scale war against Ukraine. The image transformations included four stages: (1) taking and editing photographs; (2) creating a digital art layer on top of these photographs; (3) adding these layers using AR software; and (4) making the pieces available for interaction—scanning of original images to see the layered graphics. This way, I adapt the methodology of compositional interpretation to create an augmented reality poster essay and to discuss the potential of AR image-making in imagining and implementing peaceful futures, using Ukraine’s heroic defense as a visual case study. Based on this artistic-technological experiment, I explore the potential of augmented reality technologies as peace technologies: broadly referring to “using digital technology to positively influence peace processes” (Harlander 2020) and here meaning AR technologies as tools empowering individual creators to engage in acts of “guerrilla peacebuilding.”

Designing quality peace futures: theoretical grounds

For studying and constructing futures, a “key idea is to understand the future as it emerges through the interactions of socio-technical networks…” (Ahlqvist & Rhisiart 2015, p.98). This prompts my choice of using AR technologies for working with photographs of visuals created by someone belonging to a social network of supporters of Ukraine’s fight for freedom. And the goal is to enable other supporters elsewhere to further interact with these visuals. As such, futures knowledge is about “the present view [Russia’s full-scale war against Ukraine] towards potential futures [Ukraine’s peace in Ukraine]” and is “created through practice [practicing/manifesting/building Ukrainian victory through visual-technological means]” (ibid). This way, AR imaging as a socio-technical means of imagining and studying potential futures would lead to the creation of “futures images”:

“Composed of beliefs, expectations, opinions, and assumptions of what the future might be like, images of the future therefore are systemic by nature: they are formed from knowledge and flavoured with imagination. They are built with information about the past, perceptions from the present, cultural and social knowledge, personal taste, values, and needs, as well as the expectations of how things “normally” are. They emerge as hopes, fears, and expectations, and therefore influence decision-making, choices, behaviour, and action. This is why their impact on human motivation is very strong: with our decisions, we either aim to bring forth the future which we cherish in our positive and desirable image, or we try to prevent the negative and undesirable future of our fearful expectations from happening” (Rubin 2013, p.S40).

Futures images are also tools to make futures closer (see Kuhmonen 2017; Jokinen et al 2022). And futures images of peace, working as peacebuilding tools, could make peace closer. Consecutively, designing futures would mean applying “design imagination” to a non-peaceful/secure present to design a peaceful/secure future.

Design imagination broadly means cross-disciplinary transformation of real-life challenges into opportunities of inclusive, multiple and complex futures (see Ryan 2021, pp.42–46). In the process of design imagination, the design practice itself, by acknowledging its limitations, becomes “unboxed” out of its usual premises and habits (ibid). Unboxing in this project happens through operationalizing the “futures images” theoretical tool through AR artistic image layering—not just as a design exercise, but as a guerrilla peacebuilding strategy. However, the “inclusive” aspect of design thinking needs to be rethought in the context of this project.

In the case of Ukraine’s defense, the built/imagined peace is “sustaining quality peace” (see more about the framework also in Glybchenko 2022, 2023). Developed by Peter Wallensteen, the concept of “quality peace” refers to such a post-war arrangement that possesses the qualities needed to prevent further eruptions of violence and that can be considered to have three pillars: dignity, security and predictability (2015). Quality peace is largely about post-war victory consolidation, where the peace design process is dominated by the victor.

In general, this dynamic of design domination could be both negative and positive. In the case of Russia’s war against Ukraine, consolidating the victory of Ukraine, democratic values and freedom (i.e., Ukraine’s peace by Ukraine, as opposed to traditional peace focus on building/bettering relationships between “sides”) is a gain for peace design when the risk of having more than one desirable future outcome is unacceptably high. Particularly, the risk of manifesting/building/practicing any future other than the one in which Ukraine wins is that material and human resources can be driven toward prolonging the ongoing genocide against the people of Ukraine.

Another feature of consolidating Ukraine’s victory, which could be productive for peace design, is the continuity of designed peace futures. The International Peace Institute conceptualized “sustaining peace” to mean supporting those agents and initiatives that already work for peace to ensure that a developed peace arrangement, once implemented, continues to work (2017). Hence, the images used here focus on Ukraine specifically, without giving attention or visibility to the invaders and their collaborators. And design leadership is rightfully assigned to those who work for peace—Ukrainians.

Therefore, using design imagination to create “futures images” as “the present view towards potential futures” is about manifesting/building the future in which Ukraine wins. Out of the pillars that would make the victory/peace last, I focus on security as a top priority during the ongoing war, which, when established, would allow to build up the other two pillars of sustaining quality peace. The images I create here reference particularly (physical) integrity of Ukraine and its national symbols, global food security and the security of the LGBTQI + community in Ukraine. I chose these topics because I designed the AR images to reference the dynamics of Ukraine’s defense and Ukraine’s development as a country during the time of creating those images, July–August 2022. And the manifestation of the future in which Ukraine wins can happen through making the uncertain qualities of futures images productive.

While “[a]ll acts of design are themselves small acts of future-making” (Blauvelt 2021, p.90), all the futures that are not featured in these acts of design are simultaneously unmade. This applies not only to end products, but also design demonstration models (or demos)—“example[s] of a system or product, used for showing people how it works or how they can use it” (Cambridge Dictionary, n.d.). Demos, also in the form of (AR) images, can make some futures tangibly and materially happen already here and now—already more than simply likely, while defuturing other futures. Defuturing refers to “limiting the number of futures we have now, and limiting the quality and quantity of the futures of those futures” (Blauvelt 2021, pp.91–92, quoting C. Tonkinwise). Making demos of sustaining quality peace arrangements not only limits the number of futures, but also influences how these demonstration models themselves are iterated and implemented, further defuturing certain aspects/details and defining the ways to form the final peace arrangement.

The difference between defuturing and unfuturing can be best illustrated by turning to political philosophy and aesthetics and connecting the terms/practices to Jacques Rancière’s notion of “distribution of the sensible.” This notion can be understood as “the system of self-evident facts of sense perception that simultaneously discloses the existence of something in common and the delimitations that define the respective parts and positions within it… This apportionment of parts and positions is based on a distribution of spaces, times, and forms of activity that determines the very manner in which something in common lends itself to participation and in what way various individuals have a part in this distribution” (Rockhill 2004, p.7). How distributions of the sensible are designed influences what is visible, seen and available to work with. It influences what we build our futures with and on the basis of. And what is not prioritized or is (strategically) invisibilized by a distribution is defutured: we simply do not use it and/or choose to strategically further invisibilize it by how we continue co-creating/transforming the distributions of the sensible we are embedded in.

For the network of agents aspiring to sustaining quality peace, it is crucial to create a distribution of the sensible that makes the common—achievement and consolidation of Ukrainian victory—powerfully pronounced, visible and seen. By creating demos of a sustaining quality peace arrangements, we defuture, invisibilize and delegitimize scenarios that contradict the achievement and consolidation of Ukrainian victory as Ukraine sees it. Like this, we determine “‘ways of doing and making’ [here, building specifically sustaining quality peace] that intervene in the general distribution of ways of doing and making [e.g. a traditional focus on bettering relationships between ‘sides’ of ‘conflict’ that may produce illusions of equal responsibility for Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine and expect Ukraine to surrender territories for ‘peace’]” (Rockhill 2004, p.7). And such ways of doing and making also intervene in the distributions of “the relationships they maintain to modes of being and forms of visibility”—how we experience processes of building peace and the built peace arrangements (ibid.).

When the delineation between right and wrong is clear, limiting the possibilities of the wrong visually manifested/built/practiced and presented as an option contributes to peacebuilding by (re)orienting minds, efforts, material resources and time towards supporting and maximizing the good we would like to see more of. Here, that good is the successes of Ukrainians in pushing back against the invasion, restoring the country territorially and restoring its social fabric. Therefore, designing for sustaining quality peaceful futures is not about inclusion of different opinions, but it is about acknowledging the existing power relations that give some actors more prominence than others—and giving the previously not favored actorsFootnote 1 more space for just future-making.Footnote 2 That means decisive exclusion of visions that are not right/moral/lawful/acceptable/good. In other words, defuturing is about limiting all options to only smart and moral options and defining the tools and strategies for implementing those smart and moral options.

When this network of agents working for sustaining quality peace starts mapping itself to explore how the individual positions could further support the common vision, it will become evident that not all agents can act equally freely, use all the tools and strategies or work towards the full expression of their smart and moral option at once. One such Ukrainian is writing this article while embedded in a relatively safe distribution of the sensible that to some degree relatively favors innovative research that pushes theoretical and methodological boundaries, especially in connection to re-thinking peace/security research/studies in the context/aftermath of Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine. Some other Ukrainians find themselves in temporarily occupied territories, where Russians enforce distributions of the sensible that invisibilize Ukraine and UkrainiannessFootnote 3 through a series of war crimes such as “wilful killing, torture, rape and other sexual violence, and the deportation of children to the Russian Federation” (Independent International Commission of Inquiry on Ukraine 2023, p.2).

Yet, both those Ukrainians and I are part of the larger distribution of the sensible dedicated to sustaining quality peace in Ukraine. While that peace is our common goal, our individual positions and ways to uphold and further contribute to this overarching distribution are different. The specifics of our contribution to sustaining quality peace (individual position within the distribution, limitations, available tools, available ways) pertain to unfuturing peace—implementing the demos that we have to the degree that we can implement them. If we unfuture some elements of the demos, we further move the distribution of the sensible in our favor, making it even less likely that opposing/enemy forces could disrupt our distribution. Demos being simplified demonstration models, our initial defuturing acts (building the security pillar of sustaining quality peace) will be followed by further iteration and development through further unfuturing acts. Those acts will create a deliberative process that can respond to a multiplicity of sustaining quality peace visions and the developments of Ukraine’s defense against Russian invasion—to ultimately build a detailed peace arrangement as Ukraine sees it.

If defuturing is about getting oneself ready/equipped to do things and unfuturing is about getting things effectively done, then I am interested in using my position in the sustaining quality peace distribution to help those who may experience more difficulties getting themselves ready/equipped to then implement. Like those for whom having a Ukrainian flag out may constitute a threat to life in temporarily occupied territories. I will not go to temporarily occupied territories to explore things on location, but I can use my skills, talents and interests in research, tech and art/design to, in the spirit of sustaining peace, support those who already work for peace—Ukrainians resisting to the occupying forces.

To Rancière, “[t]he essence of politics consists in interrupting the distribution of the sensible by supplementing it with those who have no part in the perceptual coordinates of the community, thereby modifying the very aesthetico-political field of possibility” (Rockhill 2004, p.xvi, italics as in original). And this article’s goal is to exercise the essence of politics by exploring how it may be possible to express Ukrainianness in guerrilla ways when it is not possible to do freely. While I do not imagine AR technologies and futures design as magical solutions, my overall hope is that new tools and strategies would change the field of possibility by making it safer to perform actions of (Ukrainian) resistance and by bringing closer peace as Ukraine sees it.

Guerrilla peacebuilding: unfuturing as empowerment

To “reconfigure the present for the future,” design imagination builds on combinations of almost, what if and maybe moments that create opportunities for imagining new realities (Ryan 2021, p.44, quoting S.T.Asma). In considering AR images as tools to design quality peace futures, I propose to pay special attention to the often overlooked in related research moments of “not quite there yet.” Those are the moments when we have a layered image–a demo—of a potential peace arrangement over a war-ridden reality, but the demo as the fruit of our imagination has not been implemented yet. In other words, this is the moment when we most prominently see the divide, the difference and the distance between what we have and what we are aspiring to design as a sustaining quality peace future.

Research-wise, when advocating for empowerment of image-makers to facilitate change, it is important to not jump to the point when these image-makers are already changemakers. It is important to pause when they are still without the needed for changemaking power and see if (AR) image-making itself could, practice-wise, be a source of the power. Working through this without stage is vital for making sure the power is self-grown and sustaining, that the process really means empowering instead of transporting an agent into an arrangement where they are temporarily given power. This is explained below on examples of analogue and digital/AR image transformations (Fig. 1).

This is an example of how an AR image could look like for this project’s context. Practically, this is a collage of photograph and AR elements created within this project’s experiment (see upcoming sections), with additional photograph elements from a photograph taken in Kyiv, Ukraine, in February 2023 by the author. Typeface/font as available in the 2023 Adobe Photoshop, provided by hosting institution. Design by author, including background digital art and in-AR fonts/typefaces

In the AR experiment, I built on knowledge generated in image-based research and practice. Various forms of image transformations have already been researched and found to empower the image creators to imagine and express a reality different to the status quo, thus at least critiquing it, if not ambitiously changing it, through legitimization of the possibility of difference. Such image transformations include mapping and graffitiing/street art.

Mapping has been identified as a “productive and liberating instrument” to foster change in post-conflict settings such as Mostar, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Cape Town, South Africa (Forde 2019a). The process of involving locals in (re)mapping the environments where their daily activities unfold emancipated the participants to defy urban sociopolitical boundaries and portray their daily movements over the pre-defined and pre-visualized boundaries (Forde 2019a, 2019b). Yet, this type of empowerment is temporary because it requires an arrangement similar to the research arrangement of the work above: a situation where someone would be invited to make changes and given a map to work with. This also requires tools unlike those which most people use daily. (When reading this, you are more likely to have a phone with the Internet connection, which you could use to create or participate in an AR intervention, than a map and a marker.) The empowerment of the exercise, even if making a lasting impression, would not itself be lasting since the changemaking would stop to unfold outside of the specially facilitated conditions of the (re)mapping exercise.

A more rebellious example of image-making/transformation like graffitiing offers insights into how image-making could be more effectively empowering, although still only temporarily lasting. Graffiti, so far under-researched in contexts of peace and conflict, “can depict imaginaries of the future, as images of peace can be portrayed during conflict, and conflict during peacetime” (Vogel 2020, p.2154). Often illegal, graffiti can provide a platform for voicing those thoughts for which there exists no officially suitable space (p.2153), which is sometimes the case for peace thoughts/work and peace images as their reflection/embodiment. Graffitiing is essentially about claiming space for and visualizing an idea where there was no place designed for that idea, making it a disruptive practice.

Street art, differentiated from graffiti as having a (clearer) message for the surrounding communities (Tellidis & Glomm 2018, p. 200), has also been described as an alternative technique of “doing/thinking security, community and peace” (p.192). That is because, with street art being simply around, “you are invited to recognise a part of yourself in the work and you are confronted by the message, whether or not you wish to be–not unlike advertisements” (p.200). Yet, graffitiing and street art still require conditions of relative privilege: having a wall/surface to create images on, having the art materials and being able to cover/hide while/after doing the art piece. The image only lasts until it is painted over or the surface is demolished/transformed. Photographs of the graffiti and street art pieces can surely remind of the periods of empowerment, but the everyday embodied presence would be gone.

AR images, in contrast, can be effective tools of empowerment when the physical redesign of a space is impossible and when creating a non-digital image is out of the limits of safety/privilege for those seeking to engage in designing quality peace futures. As smartphones are currently more of survival tools than signs of economic wealth, digital peacebuilding processes become more available to more potential users/contributors. And what AR image-making enables is engaging with the current layout of power relations (the photographic marker image to be scanned) by shifting its elements (the layered graphics), thus acknowledging the current power relations and one’s position in/towards them (as in a distribution of the sensible).

Critique and proposition of alternatives happens in the process of scanning, when the “now” and the “future” meet, as my photographs of the scanning process show. They meet when the sustaining quality peace future is “not quite there yet” (not implemented in reality) but is already unmistakably visible. Similarly to street art surrounding viewers, scanned AR images can also make viewers “confronted by the message, whether or not [they] wish to be” (Tellidis & Glomm 2018, p. 200). Once an AR-creator produces their pieces, they are around for others to scan without prior knowledge of what they are scanning. That way, if, for instance, in a temporarily occupied-by-Russians territory of Ukraine, a Russian invader would scan an image to see pro-Ukrainian AR-graphics layered there, the process and result of scanning would be self-defeating for the Russian, since with their own hands and mobile device they would bring to the forefront of that moment/location an affirmation of Ukrainian statehood and civilian Ukrainianness.

Apart from being just visible, AR images are also experienced in embodied ways, as the reader will see in the photographs of my colleague holding my phone to scan the original images. Helen Jackson studied “the augmented reality (AR) image as an embodied and interactive experience of image “in” location” (2016, p.211). They emphasized that “these [AR] informational technologies operate in virtual spaces, but access to them is dependent on embodied interaction in physical places, information flows between technology and the user are thus understood as a product of both real world environmental dimensions and virtual algorithms (de Souza e Silva 2006; Kabisch 2008; Kluitenberg 2006)” (p.213). Because “the body frames and gives meaning to the computational data” (ibid.), this combination of real-world/tangible and virtual makes the AR quality peace future (the layered graphics) much closer to its participant (the one who is scanning).

AR images are experienced in embodied ways through the same technology as the photographic images of the real environment—a phone camera. This makes AR quality peace futures in a way equal to the original photographic images. Such duality could be a strategic source of power for those seeking to design quality peace futures (here, Ukrainians), especially in war times and in guerrilla ways. And using AR technologies to design quality peace futures through images that can be so dually experienced could be an example of guerrilla peacebuilding.

While guerrilla warfare is relatively well researched, “guerrilla peacebuilding” is not. Irregular and non-official peacebuilding would be called “grassroots” or “bottom-up,” as though “bottom-up” is a flat highway with no structural obstacles instead of a struggle to defy the social-political gravity of grassroots’ resourcelessness. In other words, peace research often does not make use—and sometimes completely overlooks—power relations and the politics of entering the role of a peacebuilder.

Therefore, I propose looking into guerrilla warfare’s strategic use and subversion of power relations as a source of empowerment for peacebuilders, who are not official peace actors (i.e., not diplomats, NGO leaders, activists). They may be regular citizens, whom a war in/nearby their country could turn into an unofficial peacebuilding cohort. Thinking about guerrilla peacebuilding in the case of Ukraine’s defense is especially useful since images in support of Ukraine are essentially part of information warfare. And technologically enhanced images could be part of the digital front of the war, spearheaded by the IT-Army of Ukraine—a creation of the Ministry of Digital Transformation of Ukraine.

Guerrilla warfare can be understood as a “type of warfare fought by irregulars in fast-moving, small-scale actions against orthodox military and police forces and, on occasion, against rival insurgent forces, either independently or in conjunction with a larger political-military strategy” (Asprey, 2022). By nature being responsive to official/traditional warfare and rooted in the affected context, guerrilla warfare is challenging to define holistically (as guerrilla peacebuilding would be too). But its defining feature is asymmetry. This aspect of asymmetry is relevant also for peacebuilding: Peacebuilders can often find themselves outnumbered amidst all the violence of an armed conflict or a war and among the possibly unmanageable amounts of violence-centered images that these conflicts and wars can generate.

Asymmetric warfare describes such dynamics as “the weak against the strong, nonconventional against conventional combatants, and tactics ranging from ambush to the use of box cutters and computer hacking” (Smith 2019, p.1, building on Thornton, 2007). This asymmetry is strategically used to “exploit an opponent’s weaknesses, attain the initiative, or gain greater freedom of action” (Smith 2019, p.2, quoting Metz and Johnson 2001:5), which could also characterize national resistance to invaders in temporarily occupied territories of Ukraine. This subversive empowerment can also benefit peacebuilders on the ground, if, according to quality peace sustaining futures, the good (what/who works for peace) is to be so strengthened that it pushes out the bad (violence/invaders).

A related concept, “guerrilla democracy” could offer insights for connecting peacebuilding and “guerra” into empowered “guerrilla peacebuilding.” Aiming “to promote the importance of a new democratic ethos focused on reimagination and reconnection” (pp.78–79), Peter Bloom, Owain Smolović Jones and Jamie Woodcock (2021) conceptualized “guerrilla democracy” to refer to: (a) “the mobile and potentially viral ways contextually embedded actors can experiment with virtually reimagining the social and forging new connections for its actualization” (p.80) (like AR interventions in temporarily occupied territories); (b) “investment in truth and the exploration of its multiple possibilities for revealment” (pp.79–80) (using AR and emphasizing the divide between the now of the marker image and the future of the cartoonish layered graphic); and (c) design “explicitly aimed at simultaneously working with authorities to craft better policies while expanding democracy beyond its liberal democratic limits” (pp.79–80).

Regarding the last point, I understand “working with authorities” in the context of my work not traditionally (e.g., not as collaboration with invaders in temporarily occupied territories). Rather, I understand it as the following: guerrilla peacebuilders comprehending that the power relations put them at a disadvantage at the start, acknowledging their place in relevant distributions of the sensible, and working with those power relations and distributions creatively/subversively to gain visibility/prominence/power. Like this, guerrilla peacebuilders explore “what opportunities a given context or network provides for building up resistances to prevailing discourses and spreading contagious truths,” whereby a “truth” is the approaching Ukrainian victory and Ukrainian peace (Bloom et al., 2021, pp.79–80). Guerrilla peacebuilders demonstrate and act on “a willingness to creatively deconstruct this system [here, of violence and occupation] in order to realize what they see as important moral ends [here, the approaching Ukrainian victory and Ukrainian peace] which the present status quo [here, violence and occupation] cannot or will not achieve” (ibid.).

When conceptualizing “guerrilla democracy,” the scholars explained their choice of “guerrilla” approaches specifically by emphasizing the need to investigate “the potential [of mobile technologies and mobile power] for small- and large-scale political transformation” (pp.10–11). Similarly, I focus on three instances of small-scale action–AR image transformations—potentially leading to large-scale political transformation–sustaining quality peace. The upcoming sections operationalize these theoretical connections between AR image-making and guerrilla approaches to peacebuilding to pronounce and create implementable demos of sustaining quality peace futures by Ukrainians in Ukraine.

AR technologies for unfuturing peace: methodological notes and practicalities

The methodology of compositional interpretation, developed primarily based on knowledge about analogue images, focuses on the image itself—looking at its compositional qualities (Rose 2012, ch.4). Compositionally, I focus on the layering of photographic and computer graphics in creating marker-based AR images. While compositional interpretation only marginally considers production of images (p.56), I place it at the center of my inquiry to investigate the potential of AR technologies for designing quality peace futures and implementing them. The result is an adaptation of what traditionally would be a “photo-essay,” “a combination of writing with photographs” (p.317), to working with AR technologies. I created a poster essay Augmented Reality Freedom Posters in Support of Ukraine, using UN DPPA’s AR peace poster competition as a distant inspiration for the methodology.

The images that I used as the basis of the AR experiment are photographs I took in Vilnius, Lithuania, in July 2022. The photographs depict visual manifestations of supporting Ukraine during the 2022–2024 Russia’s full-scale war against Ukraine. Although I think of potential uses of AR technologies in temporarily occupied territories of Ukraine for their rapid liberation and rebuilding, my examples come specifically from Vilnius because of the war’s effect on my life. I was in Lithuania to conduct part of an arts-based peacebuilding project for Ukrainians and their host communities, and I took the photographs in the project breaks.

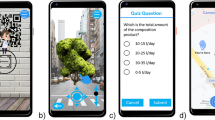

I took the photographs with my phone’s camera, and later enhanced such of their qualities as, for instance, vibrance and saturation in the raster graphics software Adobe Photoshop. To create the augmented reality experiences, I made digital art pieces to be layered onto the photographs using a Wacom graphic tablet, a stylus and Wacom 6D digital brushes. I drew those visual elements by hand in the vector-based graphics software Adobe Illustrator.Footnote 4 I proceeded to do the image layering in the online AR-creator application Overly, and the results can be seen by scanning the photographs (both from a screen and paper printouts) with the Overly mobile app, available for free for both Android and iOS.

The choices of hardware and image-editing software follow the logic of sustaining peace, here meaning using the tools that I have already had and have been using for digital arts-based peacebuilding—including within my peacebuilding startup Color Up Peace. I came to choose Overly because, after trying an array of other (mobile) applications I downloaded and experimented with, I found it to be user-friendly, easy-to-use, and to offer a variety of AR-creation options (layering images, video, 360-content, 3D objects, and more). While the free version at the time (summer 2022) allowed to develop and use only two AR pieces and only with video content, the possibility to create/use more pieces with more options could be purchased. When the payment expired, the AR pieces were unpublished (but not deleted from the creator’s online Overly account). And the payment plan could be manually downgraded to make the pieces unpublished (in addition to the everyday option to unpublish the pieces). The creator could see how many times the AR image had been scanned.

Further on political economy of the Overly app, it is important to consider data collection, its possible usage and ownership of generated content. At the end of 2023, the app’s privacy policy states that certain information is collected when the Overly app or website is used (e.g., “digital images of the objects and people you are scanning”). And it states that “[w]hen you use our Overly administration tool and/or our APIs, content generated or procured by you might be transferred to the Overly platform (‘User Generated Content’)” (Overly, n.d., section 4). Collecting data from such potential guerrilla peacebuilding initiatives can bring both dangers (in cases where the identity of a peacebuilder can be revealed leading to threats to life) and benefits (re-using this data ethically in effective justice processes to prosecute invaders).

I do not intend to promote this app through this project. But at the stage of exploring the potential of AR as a peace technology, it would not have made any research or practical sense to develop an entirely independent AR tool from scratch. Such explorations with existing/established apps/technologies can help (re-)think how we design apps/technologies in general and how we would need to design them for usage in peacebuilding settings specifically (including data policies, sharing, re-use etc.). This is important because every sensitive context might require unique policies and practices on data cycles.

During the research process, I had a chance to talk to a staff member of Overly about my experiences using their app,Footnote 5 my needs as a user and how these needs could be met (including my data considerations and questions). I explained why and how I used the app for considering peacebuilding processes specifically in this article, and how the app could be changed to meet my needs as a peacebuilder specifically. That in itself is one of the research goals accomplished—influencing the ways software is designed to support peace processes, even if it is just a start of rolling out that influence and making sure it translates to software development action.

While one AR poster essay would not suffice for building a broad understanding of AR technologies as peace technologies for implementing peaceful futures, “[i]n arts based research, generalizing from an n of 1 is an acceptable practice” (Latz 2017, p.33). Content-wise, while the AR layers I created here are demos of potential peace arrangements layered over a war-ridden reality, the whole AR pieces (by themselves and when arranged into my poster essay) are demos of how AR technologies could be used as peace technologies for guerrilla peacebuilding. In terms of the research process, this means it would not be ethical to engage research participants before AR tools are designed and framed to allow for contextual and nuanced peacebuilding.

The making of sustaining quality peace futures

Presented and discussed below are the original images (top or left of the visual), and the layered images (down or right of the visuals) users can see after scanning the original ones.

Repairing flags

Because the flag of Ukraine here (Figs. 2, 3) looks like someone unsuccessfully tried to remove it, I built the AR artwork’s subject around repairing freedom to highlight Ukraine’s long-ongoing fight against Russia’s invasion. This experiment I performed is not only about defuturing as limiting the futures that may be constructed, but the dialogical struggle of pronouncing some already imagined futures as purposefully unacceptable. The way that parts of the flag appear to be torn off the glass window tells me someone perhaps tried to physically assault—unstick—this pronunciation of support to Ukraine. This can be understood as someone imagining a future where freedom does not win.

Out of many photographs featuring the colors/symbols of Ukraine I made in Vilnius, I especially wanted to work with this one because it highlights that peacebuilding is a process and not a series of statements. And it highlights that one’s position needs to be constantly supported through action, as the “freedom repair” new business name and opening hours suggest. Here, the augmented reality technologies of layering an image over another—instead of replacing one with another—are especially important for designing sustaining quality peace futures. As in victory consolidation, a peace arrangement does not erase that a war happened. But it incorporates its memory and material consequences into such parts of peacebuilding processes as, for instance, economic reparations and restorative justice measures.

To return to pre-digital/AR image-making as a guerrilla peacebuilding strategy, post-war Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina, saw a particular role of graffiti, created by the local artists, which also tried to make the most of overlaying graffiti images over spaces. Sarajevo “in its post-war period” had “completely or partly destroyed and abandoned buildings, houses and other objects… seen all over the city” (Dugandžić & Mraović, 2019, p.9). At the same time, the increasingly-seen-all-over graffiti served as “intervention tactics of continuous insistence on differences, i.e. of rejecting to merge into a specific system of regulation and point to the gaps in the system within which potential resistance in the form of counter-space and counter-tactics can be created” (ibid.). This is an example of resistance to the aftermath of the war, the feel and the look the war brought to the city, and how it affected its citizens. And this is a statement of the city being greater than the armed violence inflicted on it. The lifespan of individual graffiti pieces was often short, especially in a city that is being rebuilt:

An outer wall of a factory with a throw-up on it was knocked down and a completely new building was raised. A newsstand was removed, and the original spatial context of the graffiti disappeared forever. Nonetheless, the writers do not worry about it too much. There are walls everywhere (Dugandžić & Mraović, 2019, p.11).

I, in contrast, worry about walls in Ukraine. With Russia’s war against Ukraine ongoing and more of Ukrainian built (and natural) environments suffering, walls are not everywhere. But resistance to the system of the invasion must continue. In this case, AR could be especially useful in creating counter-spaces that cannot be destroyed by a weapon like a wall can be destroyed. I believe it would not be reasonable to launch a missile or a drone attack against an augmented reality graphics layer. At the same time, the flag in the AR piece above will be an effective Ukrainian counter-space and the AR application itself will be an effective counter-tactic: counter to Russian invasion and its proponents abroad (whoever seemed to have tried to unstick the flag). If the sticker flag is physically vulnerable, augmentation of its materiality makes its presence continuous and extended, especially in this type of AR.

The present in AR becomes extended, if the designer of quality peace futures designs marker-based AR pieces, like I did. If an AR piece is marker-based, a static image—a photograph—serves as a “marker” which, with the help of computer vision, triggers device-based or cloud-based recognition leading to the appearance of the layered graphics over the marker (Zvejnieks 2022, para.3). For computer vision to be effective, the marker needs to be unique with high enough image contrast (partly why I edited levels/vibrance/saturation) (see para.4). This means that while AR creates opportunities for users to integrate content “into their real-life environment in real-time” (para.1), in my image-making experiment the “real-time” of when the photograph was taken (and me in the reflection) is stuck in that “present.” And if someone went to the place in Vilnius at a similar time in the day/year to scan the glass window from the same angle with the Overly app, it will most probably not work because of my marker’s uniqueness.

This way, scanning the static image above in its extended present gives continuous opportunities for designing quality peace futures for Ukraine. As a Ukrainian, I hope that the flag was restored to its physical integrity by the business owners. Yet, the visualization of the consequences of its possible assault makes the “again,” that is “never” supposed to happen, ever so eminent. If effectively integrated into peacebuilding processes, this image can serve as a driver to metaphorically ensure the memory of the atrocities and continuous efforts to actively ensure the “never.”

In Ukraine, AR has been used for cultural preservation by projecting “[a] live mural … at a wall of a building destroyed by a russian missile in downtown Kyiv and dedicated to Mykola Leontovych, [Ukrainian] author of the world famous Shchedryk (Carol of the Bells)” (see In Ukraine online media, post of 20 December 2022).Footnote 6 This way, I understand, the AR piece commemorates the past (composed music and its cultural significance for Ukraine and the world) and highlights the non-permanence of current destruction—resistance to the system of the invasion. While AR technologies overall foster interactivity with a real-world environment (and can reference the past too), marker-based AR pieces which I have created here, because they are based on an image of a real-world environment, are one step removed from the everyday movement of that environment. However, for designing quality peace futures this is not a problem. Instead of fostering interactivity with a real-world present, scanning a marker image to see the layered art is interactivity with a futures image to pull it closer—unfuture it.

Planting sunflowers

This image’s AR content (Figs. 4, 5) was themed around the first ships with Ukrainian agricultural products leaving Ukraine in the first half of August 2022 to deliver the products to foreign markets amidst Russia’s blockade of Ukrainian ports (see Svidomi online media, update on 6 August 2022, 23:00). Content-wise, the poster advocates for international efforts to remove the blockade of the Ukrainian ports so that Ukraine as a “global food security guarantor” could, as in the previous years, make “it possible to avoid food shortages, as well as hunger and political chaos in countries that need food products” (President of Ukraine 2022, para.7–8).

The choice of depicting a sunflower is partly to highlight food security, as 55% of global sunflower oil supplies are produced by/in Ukraine (MFA of Ukraine on Twitter, 5 March 2022). And partly the choice is due to the cultural significance of sunflowers to Ukraine and Ukrainians, which can be highlighted through acts of “symbolic sunflower planting… in support of the Ukrainian people and Ukraine's integration into the family of the European Union” in Riga, Latvia (Civic Alliance Latvia 2022). In both cases, focusing on digital and AR qualities of the sunflower beyond its physical materiality supports continuity of what the sunflower represents as an example of ontological security.

Psychologically and politically, ontological security refers to individual and collective “confidence that most human beings have in the continuity of their self-identity and in the constancy of the surrounding social and material environments of action” (Ejdus 2017, p.24, quoting Giddens 1991, p.92). Although the concept was originally developed to analyze experiences of individuals, it has mostly been applied to states, which “require constancy in their material environment [natural and built locales] in order to have a sense of continuity in the world” (p.27). The restored flag of Ukraine in the first AR piece and the continuity of Ukraine that I associated it with, was, similarly, an AR expression of my individual ontological security and Ukraine’s ontological security.

Digitalization and AR-izing of food security and security of identity in the form of the sunflower present an opportunity of continuity, since the field of conservation of new media and digital arts considers effective such conservation approaches as “endurance by variability” and “permanence through change” (Dekker 2016, p.556, quoting Depocas et al., 2003). This can also refer to the change that happens when creating an image of a physical object in a digital plane. Then, unfuturing peace is about making the elements that support it continuous in digital and augmented ways already now—when physically they are endangered.

To further build on social media accounts serving as digital archives to deal with uncertainty of outside-of-social-media life (see Areni 2019), AR images in the context of during-war peace-aspiring actions can make the moment of achieving post-war restoration closer. Another way to unfuture peace is to build (AR) archives/repositories of peace (or what works for peace) to bridge the divide between the “now” of violence and the “at some point in the future” of a peace arrangement. Symbolically in AR, it would undeniably exist (at least when looking at one’s phone screen) and so be close, even if it cannot just yet be fully experienced.

It is even more important for people to create such peace repositories during periods of enemy’s violent attacks. The consequences of these attacks (ruined buildings, damaged cultural/national symbols, etc.), if they continue unchallenged or unresisted to, can also tragically become a source of ontological security as they could overtime “generate a sense of stability and certainty” (Rumelili 2015, p.2). Such consolidation of suffering and such turning of peace prospects into a source of anxiety can happen when armed violence and victimhood are normalized and when perpetrators of violence are appeased/unpunished.

Adding colors

This poster’s (Figs. 6, 7) inspiration comes from the petition by Ukrainian citizens to legalize same-sex marriage in the country. That is why it features the LGBTQI + flag colors around a column full of blue-and-yellow posters in support of Ukraine. The Ukrainian online media Svidomi on its Instagram account in English highlighted this development with caution, noting that the martial law in Ukraine did not allow the state to introduce the necessary changes to the Constitution of Ukraine to sign same-sex marriages into law (post of 2 August 2022, 22:15). Legally, even if the move is welcomed by the citizens and the President of Ukraine (ibid.), it would still take time before it becomes a reality and not a future. Making it manifest visually in AR is then an act of pulling this future closer—unfuturing inclusive of LBTQI + values peace in Ukraine—by working with colors.

The Pantone Color Institute, as a “leading source of color expertise” in developing effective “color strategies” to address “color challenges” worldwide (Pantone, 2022), branded solidarity with Ukraine in “Freedom Blue” and “Energizing Yellow” by recreating the flag of Ukraine in a Twitter post of 3 March 2022. The colors coming to mean Ukraine’s fight for freedom outside of Ukraine’s symbols, illustrate the potential of colors building something non-existing just yet using what colors are—colors. (After all, Pantone posted a color palette, not the flag of Ukraine.)

Edith Young, researching the history of art and popular culture in visualized square color palettes, showed that “it’s not just a red apple but also an apple’d red” (2021, p.8). That means, colors co-form what they color and retain this ability even when outside of that which has been colored. An example of that can be presenting colors in square palette forms. Out of these palettes, the colors can be picked again to color something else. I was also picking colors in Adobe Photoshop and Adobe Illustrator when creating the layers for the AR image transformations. Thus, practicing designing quality peace futures through color-use in AR is a possibility to create a color palette of quality peace futures. It is a possibility to brand these futures as peace futures and make them recognizable, which would aid design imagination.

Generating a palette such as this is not an insurmountable task. For decades, the Pantone Color Institute has annually been announcing a color of the year, which is a result of its color connoisseurs’ “comb[ing] the world looking for new color influences” (Pantone, 2022, para.6). The emphasis on novelty here can also be understood as these colors being “released” or “created”—with new meanings and associations—like sustaining quality peace futures.

Let’s imagine a war-affected community created an artivist peacebuilding intervention to let the occupying forces of the military aggressor state know they are by no means welcome. The colors that are used, especially those that come up often, can be consolidated into the peace palette as seen by that community. And these colors can attain symbolic value, while becoming tools of peacebuilding to brand that community as belonging to the original population(’s state) and not the aggressor state. Beyond the community in question too, these colors can be used to “release” a palette of quality peace futures to aid other peacebuilding communities elsewhere to unfuture their peace, adding their colors to the collective palette too.

Guerrilla marketing and unfuturing peace

Instead of “releasing” colors like Pantone does, some Ukrainians have had to dig colors into the ground for security reasons during temporary occupation. On November 10, 2022, the online media Ukraine.ua shared on their Instagram account a photograph of a jar containing the flag of Ukraine with the caption: “A local from the Kharkiv region hid a yellow-blue flag [emoji of the flag of Ukraine] in a jar and dug into the ground, so that Russians did not find it… Only when the Ukrainian forces liberated the settlement, a man got in touch with our warriors and told them where the symbols of Ukrainian statehood and resistance could be found” (Ukraine.ua, 2022). Then, if guerrilla democracy is about “reimagining and rematerializing of the social through … hi-tech methods,” it is important to explore what “potential for small- and large-scale political transformation” AR technologies would hold in this situation (Bloom et al., 2021, pp.10–11). Out of security considerations only, leaving an AR Ukrainian flag “out” and not having to worry about its physical integrity could be an effective way of expressing resistance and branding peace into the colors of Ukraine. My poster essay, the demos of peace arrangements within it and the latest color discussion could also raise questions of branding—(guerrilla) marketing of sustaining quality peace.

Guerrilla warfare, at its intersection with peace too, has recently been researched in the context of Colombia, decades of violence in the country, and the 2016 Havana Peace Agreements between the Colombian state and the Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia–Ejército del Pueblo (FARC-EP). Although FARC-EP is seen as a guerrilla warfare group, research from this context guides some of the further argumentation on unfuturing peace as guerrilla peacebuilding.Footnote 7 Conceptualized for examining intersections of counterinsurgency (antiguerrilla warfare) and capitalism in Colombia, “guerrilla marketing” refers to the collaboration between the Colombian Ministry of Defense and a consumer marketing enterprise Lowe/SSP3 to develop marketing campaigns using affect to foster individual demobilization of FARC-EP guerrillas (Fattal 2018) and so arrive at a peace arrangement.

Conceptually and practically, guerrilla marketing was based on two ideas: that “marketing had the power to debilitate one of the world’s largest and most formidable insurgencies and precipitate peace” and that “the world’s most intractable problems can be branded away” (p.xi). Employed by the military and targeting guerrillas (as counterinsurgency and peace policies become “imbricated” in Colombia), guerrilla marketing develops guerrilla warfare’s tactics of camouflage “not merely to blend into the background, but to act upon it” (Fattal 2018, p.18,15). With my AR poster essay too, the intention was by no means blending with the background (also expressed in the purposefully different, cartoonish in style, layered graphics)—but making a decisive difference to it.

Guerrilla marketing in the context of Colombia learned from brand warfare, when:

“a multiplicity of armed actors adopted media strategies and tactics from each other, a process that drove the mediatization and spectacularization of the armed conflict through the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. This intensive borrowing between the conflict’s armed actors has further blurred the boundaries between politics, business, crime, revolution, and counterrevolution, attenuating the conflict’s earlier ideological framing in the face of a sweeping and popularly held idea that the war, in its later iterations, had become nothing but a business. One corollary of this logic is that if war can be reduced to business, the victor will be the party with either the best product or the best marketing.” (Fattal 2018, pp.67-68)

AR “branding” of peace could have an advantage in the competition for both “best” “product” and “marketing,” especially since guerrilla marketing holds that “marketing is the message” (Fattal 2018, p.13). Firstly, in terms of anonymity of guerrilla peacebuilders while unfuturing peace, no information about me came up to the viewer scanning the marker images. An exception here is that I inserted my art signature into the images out of consideration for ownership/safety of art/research online.

Secondly, unfuturing peace through such “branding” strategies as my AR poster essay could help create territorial peace. The concept of “territorial peace” evolved from the Colombian peace negotiation process to denote the bottom up (from the country’s differently affected regions) strategies for building and owning peace (Cairo et al. 2018). Although still fuzzy and understandably Colombia-specific, territorial peace considers “what ‘territory’ means to a diverse range of actors” (p.465) and “a condition to recognize the country’s economic, social, cultural and environmental diversity and particularity” (p.468).

In 2014–2024 Ukraine too, different regions have been differently affected by the ongoing war. And while designing sustaining quality peace futures means designing futures in which Ukraine wins in its entirety (see war.ukraine.ua., 2023), accessing all Ukrainian territories physically to create in-location sustaining quality peace interventions may not be possible all at once due to security concerns (e.g., landmines). Yet, accessing territory-specific quality peace futures can be possible through, for instance, sharing the marker images wider and making them available for scanning to larger groups of people. Furthermore, AR image-making presents opportunities of layering just about anything over just about anything, so the initial marker space is quite limitless. If there is an image of a space to engage with as the marker, this space can be engaged even if the AR image-maker cannot physically access the space anymore or if the space has been destroyed.

Thirdly, unfuturing peace through AR interventions like that can help approach the time and the process of peacebuilding with a greater emphasis on ontological security. One of the challenges of transitioning from guerrilla warfare to peace for guerrilla fighters in Colombia has been the “experience of limbo, waiting to incorporate into civilian life” (Álvarez et al. 2022, p.132). Between the violence of military occupation and the peace of national liberation, there can be a limbo too. This sense of limbo can be challenged if guerrilla peacebuilders unfuture peace, therefore making peace ontologically secure over time and digital spaces. An AR layer, on the one hand, is there when scanned and, on the other hand, is just as much not there when the AR app is not used. While the realities of war/violence can take time to transform holistically, quality peace futures can be seen and experienced in AR without having to go through the whole duration of the transformation. And these AR expressions, becoming tools of peacebuilding not suspended in time, can guide the transformation.

Brand warfare, in general and in the case of Colombia, targets not only individuals, but aims to also transform “categories as amorphous as the national mood, the cultural atmosphere and the international imagination” (Fattal 2018, p.80). Another category it can help support is non-colonial peacebuilding: as explained earlier, sustaining quality peace as Ukraine sees it. While the traditional focus of peace research/studies and research/employment of technologies in peace processes has been on “promoting dialogue/understanding and cooperation/reconciliation between “sides”/“parties”/“groups” to conflicts,” sustaining quality peace would mean “severing of all kinds of contacts/“dialogues”/“understandings” between Ukrainians and Russians that should never have happened in the first place: (neo-)colonial/imperial interactions by definition happen without the true consent of the colonized and against their dignity/security.” (Glybchenko 2023, p.3).

Supporting this category of non-colonial peacebuilding can happen through making the layered art stylistically different (cartoonish like in my AR poster essay) and content-wise conflictual to the marker image. This kind of expression of a sustaining quality peace future is more emancipatory in comparison with striving for photograph-like authenticity in style and content. Such authenticity would unavoidably require concessions from guerrilla peacebuilders as they try to integrate their peace vision into a rigid physical space or even a digitally malleable space if those spaces are organized in accordance with imperial/neo-colonial distributions of the sensible.

The difference of layering an image over another (thus rising above imperial/neo-colonial distributions) can also facilitate design imagination itself. Imagining different futures could be especially challenging in post-colonial settings where the imperial powers would have significantly curtailed the cultural and social resources that make design imagination possible (see Heidenreich-Seleme & O’Toole 2016; Blauvelt 2021). Purposeful difference from that background would facilitate the design of non-colonial futures where sustaining quality peace could be possible and likely.

Conclusion

This project explored the potential of AR technologies as peacebuilding tools to unfuture peace, using Ukraine’s defense against Russia’s 2022–2024 full-scale invasion as a visual case study for designing sustaining quality peace futures. If defuturing means defining the tools and main principles of futures design for sustaining quality peace arrangements (including first demos), unfuturing peace means creatively and subversively implementing those futures (including iteration and detailing towards full versions of peace arrangements) in as much as possible in potentially adversarial/dangerous conditions. Embedded in a network of sustaining quality peace that focuses on supporting those agents/things who/which already work for peace (the network itself), each guerrilla peacebuilder’s actions would gradually contribute to reimagination and rematerialization of sustaining quality peace arrangements through tech tools and design strategies. This would ensure that empowerment is self-grown and not dependent on artificial settings, which may temporarily simulate empowerment, or on imperial/neo-colonial residue/reality.

Since this project engaged with the AR pieces as demos only and all of them were created by a single person (author), more research, design and development steps need to be taken by a variety of stakeholders to enable (guerrilla) peacebuilders to employ AR technologies as peace technologies in their work ethically and effectively. That variety of stakeholders, depending on the context, can include peacebuilders, local communities, tech representatives, designers, and others. To further theoretically and methodologically substantiate “unfuturing peace” with AR and “guerrilla peacebuilding,” further research/application efforts could: consider an array of other (existing and to be designed) AR software to layer other types of content over markers and locations, ethically create a test/iteration experiment of unfuturing peace to gain input of the suggested variety of stakeholders to enable independent technology design as peace technology design, connect guerrilla warfare/peacebuilding to contexts other than Ukraine and Colombia and consider other types of peace technologies for guerrilla peacebuilding.

Change history

31 May 2024

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1057/s42984-024-00095-y

Notes

referring to general lack of interest and action of international community in response to Russia's illegal occupation of Ukrainian Crimea and war in the east of Ukraine in the years of 2014-2022.

meaning decisive support to Ukraine and Ukraine’s implementation of peace as it sees it, now primarily through the 10-point peace formula of President Zelenskyy (see war.ukraine.ua, n.d.).

Ukrainianness here meaning an unrestricted way/experience of practicing one’s authentically Ukrainian identity.

I recognize that these tools may not be available for every (aspiring) guerrilla peacebuilder wanting to potentially employ AR technologies in their endeavors. However, the logic here is to use what I already had to create user-friendly AR pieces, instead of going all the way to use more advanced AR hardware/software I could potentially find in a specialized laboratory in my research environments. At the same time, my specific tools are also not exactly required to create these AR pieces. Virtually no tools but a smartphone could do. This way, the current choices present a compromise that allows for effective research and image-making, where I believe I need to reach a certain quality of AR layers to be able to build my arguments effectively, yet without taking an exclusive elitist position.

Although this was not a research interview, the person agreed that I can reflect on this conversation in my research manuscripts.

That AR piece can be seen by scanning a QR code on location, as seen in the posted video (check the link in the bibliography). Undoubtedly, there are different technologies and ways of presentation available when it comes to AR

Within the scope of this project, I cannot effectively analyze dynamics, effectiveness or other aspects of the peace processes in Colombia, which can undoubtedly be critiqued/criticized. I only use and build off of the idea of using image-making for change in the context of Colombia, without implying that this was good/great/effective/perfect example of using images for change.

References

Ahlqvist, T., and M. Rhisiart. 2015. Emerging pathways for critical futures research: changing contexts and impacts of social theory. Futures : The Journal of Policy, Planning and Futures Studies 71: 91–104.

Álvarez, S., et al. 2022. Towards an anthropology of peace: reintegration of former guerrillas into Colombian society. Human Organization 81 (2): 132–140.

Areni, C. 2019. Ontological security as an unconscious motive of social media users. Journal of Marketing Management 35 (1–2): 75–96.

Asprey, R.B. (n.d.) Guerrilla Warfare. Britannica [Online] Available at: https://www.britannica.com/topic/guerrilla-warfare (Accessed 18 August 2022)

Blauvelt, A. (2021) “Defuturing the Image of the Future” in Hiesinger, K. B. et al. (eds), Designs for different futures.

Bloom, P., et al. 2021. Guerrilla democracy: Mobile power and revolution in the 21st century, 1st ed. Bristol: Bristol University Press.

Cairo, H., et al. 2018. ‘Territorial peace’: The emergence of a concept in Colombia’s peace negotiations. Geopolitics. 23 (2): 464–488.

Cambridge Dictionary. (n.d.) Demonstration Model. Available at: https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/demonstration-model (Accessed 8 June 2023)

Chalmers, D.J. 2022. Reality+. Virtual Worlds and the Problems of Philosophy: Penguin Books.

Civic Alliance Latvia (2022) Planting sunflowers for Ukraine and a united Europe with words of strength. Civic Alliance Latvia. [Online] Available at: https://nvo.lv/en/zina/planting_sunflowers_for_ukraine_and_a_united_europe_with_words_of_strength (Accessed 9 August 2022)

Dekker, A. (2016) “Enabling the Future, or How to Survive FOREVER” in Paul, C. (ed), A Companion to Digital Art. Available from: ProQuest Ebook Central.

Depocas, A., J. Ippolito, and C. Jones. 2003. Permanence through change: The variable media approach. New York/Montreal: The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation/Daniel Langlois Foundation for Art, Science and Technology.

Dugandžić, D. & Mraović, B. (2019) “Writing, erasing, time”, in Stojčić, B. (ed), Hotel Bristol. On walls of Sarajevo. Crvena Association for Culture and Art.

Ejdus, F. (2017) ‘Not a heap of stones’: material environments and ontological security in international relations. Cambridge review of international affairs. [Online] 30 (1), 23–43.

Fattal, A.L. 2018. Guerrilla marketing: Counterinsurgency and capitalism in Colombia. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Forde, S. 2019. Cartographies of transformation in mostar and Cape Town: Mapping as a methodology in divided cities. Journal of intervention and statebuilding. 13 (2): 139–157.

Forde, S. 2019. Socio-spatial agency and positive peace in Mostar Bosnia and Herzegovina. Space & polity 23 (2): 154–167.

Futuring Peace (n.d.a) About futuring peace. Futuring Peace. [Online] Available at: https://futuringpeace.org/about.html#about (Accessed 26 July 2022)

Futuring Peace (n.d.b) Augmented reality peace posters. Futuring Peace. [Online] Available at: https://futuringpeace.org/augmented-reality-peace-posters.html#top (Accessed 26 July 2022)

Glybchenko, Y. 2022. Coloring outside the lines? Imaginary reconstitution of security in Yemen through image transformations. Digi War 3: 113–127. https://doi.org/10.1057/s42984-022-00050-9.

Glybchenko, Y. 2023. Virtual reality technologies as PeaceTech: Supporting Ukraine in practice and research. Journal of Peacebuilding & Development 14: 85–96. https://doi.org/10.1177/15423166231211303.

Harlander, J. (2020) CMI & Salesforce l Peace Tech Webinar.

Heidenreich-Seleme, L., and S. O’Toole. 2016. African futures : thinking about the future through word and image. Bielefeld, Germany: Kerber.

Hiesinger, K. B. et al. (2021) Designs for different futures.

Independent international commission of inquiry on Ukraine. (2023) Report of the independent international commission of inquiry on Ukraine A/78/540. United Nations. Available at: https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/documents/hrbodies/hrcouncil/coiukraine/A-78-540-AEV.pdf (Accessed 13 November 2023)

International Peace Institute. (2017) Sustaining peace: What does it mean in practice? International Peace Institute. Available at: https://www.ipinst.org/2017/04/sustaining-peace-in-practice (Accessed 1 October 2022)

Jackson, H. 2016. Embodiment, meaning, and the augmented reality image. In Image Embodiment: New Perspectives of the Sensory Turn, ed. L. C. Grabbe, P. Rupert-Kruse, and N. M. Schmitz, 211–236. Büchner-Verlag.

Jokinen, L., et al. 2022. Creating futures images for sustainable cruise ships: Insights on collaborative foresight for sustainability enhancement. Futures : the journal of policy, planning and futures studies. 135: 102873.

Kuhmonen, T. 2017. Exposing the attractors of evolving complex adaptive systems by utilising futures images: Milestones of the food sustainability journey. Technological Forecasting & Social Change 114: 214–225.

Latz, A.O. 2017. Photovoice research in education and beyond: A practical guide from theory to exhibition. Taylor and Francis.

MFA of Ukraine (5 March 2022) Twitter. Available at: https://twitter.com/mfa_ukraine/status/1500176532316344322?lang=ga (Accessed 9 August 2022)

Overly (n.d.). Privacy policy. Overly. Available at: https://overlyapp.com/privacy-policy/

Pantone (3 March 2022) Twitter. Available at: https://twitter.com/pantone/status/1499461783509164035 (Accessed 9 August 2022)

Pantone (n.d.b) Announcing the pantone color of the year 2022. Pantone. Available at: https://www.pantone.com/color-of-the-year-2022 (Accessed 9 August 2022)

Pantone (n.d.a) Available at: https://www.pantone.com/color-consulting/about-pantone-color-institute (Accessed 9 August 2022)

President of Ukraine (2022) It is important that Ukraine remains the guarantor of world food security - President in the Odesa region. President of Ukraine. [Online] Available at: https://www.president.gov.ua/en/news/vazhlivo-shob-ukrayina-zalishalasya-garantom-svitovoyi-prodo-76765#:~:text=Volodymyr%20Zelenskyy%20is%20convinced%20that,food%20security%2C%22%20he%20emphasized (Accessed 9 August 2022)

Rockhill, G. 2004. Jacques Rancière: The politics of aesthetics. Manhattan: Bloomsbury Academic.

Rose, G. 2012. Visual methodologies : An introduction to researching with visual materials, 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, Calif: Sage Publications.

Rubin, A. 2013. Hidden, inconsistent, and influential: Images of the future in changing times. Futures: The Journal of Policy, Planning and Futures Studies 45: S38–S44.

Rumelili, B. 2015. Conflict resolution and ontological security: Peace anxieties. London: Routledge.

Ryan, Z. (2021) The design imagination. In Designs for different futures, ed. K. B. Hiesinger et al.

Smith, S.D. 2019. Introduction. An archeology or asymmetric warfare. In Partisans, guerrillas, and irregulars: Historical archaeology of asymmetric warfare, ed. S.D. Smith and R.G. Clarence. Tuscaloosa: The University of Alabama Press.

Svidomi (2 August 2022, 22:15) Instagram. Available at: https://www.instagram.com/p/CgxLY-Jr1aQ/?hl=en (Accessed 9 August 2022)

Svidomi (6 August 2022, 23:00) Instagram. Available at: https://www.instagram.com/p/Cg7gx9ELkX_/ (Accessed 9 August 2022)

Tellidis, I., and A. Glomm. 2018. Street art as everyday counterterrorism? The Norwegian art community’s reaction to the 22 July 2011 attacks. Cooperation and Conflict 54 (2): 191–210.

In Ukraine (20 December 2022). Facebook. Available at: https://www.facebook.com/inukraine.official/videos/1005287520385505

Ukraine.ua (10 November 2022). Instagram. Available at: https://www.instagram.com/p/CkxtM6CNNEY/ (Accessed 17 November 2023)

Vogel, B., et al. 2020. Reading socio-political and spatial dynamics through graffiti in conflict-affected societies. Third World Quarterly 41 (12): 2148–2168.

Wallensteen, P. 2015. Quality peace: Strategic peacebuilding and world order. Oxford University Press.

war.ukraine.ua. (n.d.). What is Zelenskyy’s 10-point peace plan? Available at: https://war.ukraine.ua/faq/zelenskyys-10-point-peace-plan/ (Accessed 13 November 2023)

Young, E. 2021. Color scheme : An irreverent history of art and pop culture in color palettes, 1st ed. New York: Princeton Architectural Press.

Zvejnieks, G. (2022) Marker-based vs markerless augmented reality: pros, cons & examples. Overly [Online] Available at: https://overlyapp.com/blog/marker-based-vs-markerless-augmented-reality-pros-cons-examples/ (Accessed 18 August 2022)

Funding

Open access funding provided by Tampere University (including Tampere University Hospital). Funding was provided by Gerda Henkel Foundation, AZ/08/KF/20; Kone Foundation, 202202939.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

No conflict of interest can be reported.

Additional information

“The original online version of this article was revised: ” For the unification of seplling, in the article title and content of the paper, all “guerrilla” have been corrected to “guerrilla”.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Glybchenko, Y. Unfuturing peace: augmented reality image design for Guerrilla peacebuilding. Digi War (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s42984-024-00090-3

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s42984-024-00090-3