Abstract

Debates on controversial policies often stimulate extensive discourse, which is difficult to interpret objectively. Political science scholars have begun to use new textual data analysis tools to illuminate policy debates, yet these techniques have been little leveraged in the international business literature. We use a combination of natural language processing, network analysis and trade data to shed light on a high-profile policy debate—the EU’s recently enacted Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM). We leverage these novel techniques to analyze business inputs to the EU’s public consultation, differentiating between different types of organizations (companies, trade associations, non-EU actors) and nature of impact (direct, indirect, potential). Although there are similarities in key concerns, there are also differences, both across sectors and between collective and individual actors. Key findings include the fact that collective actors and indirectly affected sectors tended to be less concerned about the negative impacts of the new measure on international relations than individual firms and those directly affected. Firms’ home country also impacted on their positions, with EU-headquartered and foreign-owned companies clustering separately. Our research highlights the potential of natural language processing techniques to help better understand the positions of business in contentious debates and inform policy making.

Plain language summary

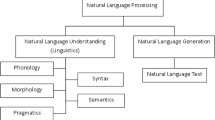

In recent years, the European Union (EU—a political and economic union of 27 European countries) has been striving for more openness and inclusivity in its policy-making process. Public consultations, which are opportunities for individuals and organizations to provide feedback on proposed policies, have become a crucial method for collecting stakeholder views and evaluating policy alternatives. The European Commission, the EU's executive branch, conducted 1744 public consultations between 2016 and 2021, generating a large amount of data on stakeholder positions in different policy areas. However, the size of these databases presents difficulties for analysis. Advances in textual analysis techniques, which involve examining and interpreting written or spoken language, now allow for detailed exploration of this data, providing insights into policy positions and their changes over time. This study analyzed responses to one such consultation on the EU's Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM - a policy that imposes a tariff on certain imported goods based on their carbon content), using natural language processing (a field of artificial intelligence that helps computers understand human language) and network analysis (a method for visualizing and analyzing complex systems) to examine business actors' inputs. The research reveals the main topics of concern for these stakeholders and how they differ across affected actors, offering nuanced insights into the perceived effects of the policy shift. The analysis identified groups of stakeholders with similar concerns and distinguished between types of actors, such as EU-owned companies, third-country actors (companies owned by non-EU countries), and collective actors like trade associations, providing a comprehensive view of business perspectives. The study also incorporated trade data to contextualize the analysis. The results show that EU-owned companies tended to group together in their responses, while those owned by third-country actors formed separate groups. Collective actors and indirectly affected sectors expressed less concern about the negative impacts of the CBAM on international relations and governance compared to individual firms and those directly affected. The research concludes that advanced data analysis techniques can significantly enhance our understanding of policy debates affecting international business. The study's findings suggest that the CBAM will have complex implications for international trade, potentially affecting competitiveness, trade relations, and the broader international business environment. The potential impact and future implications of this research are significant for both policymakers and international businesses. Leveraging advanced textual analysis can provide a comprehensive understanding of stakeholder positions to policymakers, enabling more informed decision-making. For international businesses, the findings highlight the importance of participating in public consultations to express concerns and influence policy outcomes. The study also opens avenues for future research to assess the actual impacts of regulatory innovations like the CBAM on trade, investment, and international business. As the world's first major economy to use trade policy to address international differences in carbon pricing, the EU's CBAM represents a pioneering step with far-reaching consequences for global trade and environmental policy.

This text was initially drafted using artificial intelligence, then reviewed by the author(s) to ensure accuracy.

Résumé

Les débats sur les politiques controversées suscitent souvent des discussions foisonnantes, difficiles à interpréter de manière objective. Les chercheurs en science politique ont commencé à utiliser de nouveaux outils d'analyse de données textuelles pour éclairer les débats politiques, bien que ces techniques aient été peu exploitées dans la littérature en affaires internationales. Nous utilisons une combinaison de traitement du langage naturel, d'analyse de réseau et de données commerciales pour éclairer un débat politique de haut niveau - le Mécanisme d'Ajustement des Frontières Carbone (CBAM) récemment adopté par l'Union européenne (UE). Nous exploitons ces techniques novatrices pour analyser les contributions des entreprises à la consultation publique de l'UE, en différenciant entre différents types d'organisations (entreprises, associations commerciales, acteurs non-UE) et la nature de l'impact (direct, indirect, potentiel). Bien qu'il existe des similitudes dans les préoccupations clés, il y a aussi des différences, à la fois entre les secteurs et entre les acteurs collectifs et individuels. Les principales conclusions incluent le fait que les acteurs collectifs et les secteurs indirectement touchés avaient tendance à être moins préoccupés par les impacts négatifs de la nouvelle mesure sur les relations internationales que les entreprises individuelles et celles directement touchées. Le pays d'origine des entreprises a également influencé leurs positions, avec des entreprises basées dans l'UE et des entreprises étrangères formant des regroupements distincts. Notre recherche met en lumière le potentiel des techniques de traitement du langage naturel pour mieux comprendre les positions des entreprises dans des débats controversés et éclairer l'élaboration des politiques.

Resumen

Los debates en torno a políticas controversiales suelen estimular largos discursos difíciles de interpretar objetivamente. Académicos de las ciencias políticas han comenzado a usar nuevas herramientas de análisis textual de datos para iluminar los debates políticos, aunque estas técnicas se han afianzado poco en la literatura de los negocios internacionales. Utilizamos una combinación de procesamiento del lenguaje natural, análisis de red y datos de mercado para arrojar luz en un debate de alto perfil político: La UE recientemente promulgó el Mecanismo de Ajuste en Frontera por Carbono (CBAM), por sus siglas en inglés. Nos apalancamos en estas técnicas novedosas para analizar los aportes de los negocios a la consulta pública de la UE, distinguiendo entre diferentes tipos de organizaciones (compañías, asociaciones de comercio y actores fuera de la UE), así como la naturaleza del impacto (directo, indirecto, potencial). Aunque hay similitudes en las preocupaciones esenciales también hay diferencias, tanto a través de sectores y colectivos, así como entre actores individuales. Entre los hallazgos principales están que los actores colectivos y los sectores afectados indirectamente tienden a preocuparse menos por los impactos negativos de la nueva medida en relaciones internacionales, que las compañías individuales y aquellos afectados directamente. El país anfitrión de la compañía también se impacta en sus posiciones con compañías asentadas en la UE y las de propiedad extranjera agrupándose separadamente. Nuestra investigación destaca el potencial de técnicas de procesamiento del lenguaje natural para ayudar a entender mejor las posiciones de los negocios en los debates continuos y la realización de políticas públicas informadas.

Resumo

Debates sobre políticas controversas frequentemente estimulam um discurso extensivo, o qual é difícil de interpretar de maneira objetiva. Acadêmicos na área de ciências políticas começaram a usar novas ferramentas de análise de dados textuais para elucidar debates políticos, no entanto essas técnicas têm sido pouco aproveitadas na literatura de negócios internacionais. Usamos uma combinação de processamento de linguagem natural, análise de rede e dados comerciais para lançar luz sobre um debate político importante - o Mecanismo de Ajuste de Fronteira de Carbono (CBAM) recentemente promulgado pela União Europeia. Aproveitamos essas técnicas inovadoras para analisar contribuições empresariais para a consulta pública da UE, diferenciando entre diferentes tipos de organizações (empresas, associações comerciais, atores fora da UE) e natureza do impacto (direto, indireto, potencial). Embora haja semelhanças nas principais preocupações, também existem diferenças, tanto entre setores quanto entre atores coletivos e individuais. Os principais achados incluem o fato de que atores coletivos e setores indiretamente afetados tendem a estar menos preocupados com os impactos negativos da nova medida nas relações internacionais do que empresas individuais e aquelas diretamente afetadas. O país de origem das empresas também impactou as suas posições, com empresas com sede na UE e empresas de propriedade estrangeira se agrupando separadamente. Nossa pesquisa destaca o potencial das técnicas de processamento de linguagem natural para ajudar a entender melhor as posições dos negócios em debates contenciosos e informar a formulação de políticas públicas.

摘要

关于有争议的政策的辩论往往会激发广泛的讨论, 这很难客观地解读。政治学学者已经开始使用新的文本数据分析工具来阐明政策辩论, 然而这些技术在国际商务文献中很少得到利用。我们结合使用自然语言处理、网络分析和贸易数据来阐明备受瞩目的政策辩论——欧盟最近颁布的碳边界调整机制(CBAM)。我们利用这些新技术来分析欧盟公众咨询的商业投入, 区分不同类型的组织(公司、贸易协会、非欧盟参与者)和影响的性质(直接、间接、潜在)。尽管在关键问题上有相似之处, 但在行业之间以及集体和个人行为者之间也存在差异。主要发现包括, 集体行为者和间接受影响的行业往往比个别公司和直接受影响的行业更不关心新措施对国际关系的负面影响。公司的母国也影响了他们的位置, 总部设在欧盟的公司和外资公司分开聚集。我们的研究强调了自然语言处理技术的潜力, 它有助于更好地理解企业在有争议的辩论中的立场, 并为政策制定提供信息。

Zusammenfassung

Debatten über kontroverse politische Maßnahmen regen oft einen umfangreichen Diskurs an, der schwer objektiv zu interpretieren ist. Politikwissenschaftler haben begonnen, neue Instrumente der Textdatenanalyse zu nutzen, um politische Debatten zu beleuchten, jedoch wurden diese Verfahren in der Literatur zur internationalen Betriebswirtschaft bisher nur wenig genutzt. Wir verwenden eine Kombination aus natürlicher Sprachverarbeitung, Netzwerkanalyse und Handelsdaten, um eine hochrangige politische Debatte zu beleuchten—das kürzlich in Kraft getretene CO2-Grenzausgleichssystem (CBAM) der EU. Wir setzen diese neuen Verfahren ein, um die Beiträge von Unternehmen zur öffentlichen Konsultation der EU zu analysieren, wobei wir zwischen verschiedenen Arten von Organisationen (Unternehmen, Handelsverbände, Nicht-EU-Akteure) und der Art der Auswirkungen (direkt, indirekt, potenziell) unterscheiden. Obwohl es Ähnlichkeiten bei den zentralen Bedenken gibt, gibt es auch Unterschiede, sowohl zwischen den Sektoren als auch zwischen kollektiven und einzelnen Akteuren. Zu den wichtigsten Ergebnissen gehört die Tatsache, dass kollektive Akteure und indirekt betroffene Sektoren tendenziell weniger über die negativen Auswirkungen der neuen Maßnahme auf die internationalen Beziehungen beunruhigt sind als Einzelunternehmen und direkt Betroffene. Auch das Herkunftsland der Unternehmen wirkte sich auf ihre Position aus, wobei Unternehmen mit Hauptsitz in der EU und Unternehmen in ausländischem Besitz getrennt voneinander geclustert wurden. Unsere Forschung zeigt das Potenzial von Verfahren zur natürlichen Sprachverarbeitung auf, um die Positionen von Unternehmen in kontroversen Debatten besser zu verstehen und die politische Entscheidungsfindung zu unterstützen.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In recent years, the EU policy-making process has become more transparent and inclusive, with public consultations a particularly popular means of accessing stakeholder opinion and testing policy options. The European Commission launched 1744 public consultations in the period 2016–2021 alone (Nørbech, 2023). These exercises provide a huge amount of quantitative and qualitative data about the positions of stakeholders on key policy areas. Although the sheer size of such databases can be challenging for analysis and interpretation, recent advances in textual analysis techniques facilitate detailed exploration.

In line with these advances, textual analysis has recently become popular in the political science literature as a means to better understand policy positions and their evolution (Abel & Mertens, 2023; Bail, 2016; Frelih-Larsen et al., 2023; James et al., 2021; Rule et al., 2015). Such analysis of EU consultations has yielded interesting insights into variations in positions and arguments, as well as coalition-building. Frelih-Larsen et al. (2023) used corpus analytics and software tools to identify clusters for and against key proposals on pesticide use, as well as variations in the arguments used to back up their positions. Abel and Mertens (2023) built on automated textual analysis of the consultation on the EU’s Emission’s Trading System (ETS) to identify similarities in belief systems and networks. Finally, James et al. (2021) leveraged quantitative textual analysis of responses to several consultations on financial regulation to identify networks based on text re-use and common submissions. This enables them to highlight the co-existence of national and cross-border coalitions.

In spite of their demonstrable potential to yield such insights, this data resource has yet to be widely exploited in the international business context. In this paper, we demonstrate how understanding of policy debates affecting international business can be informed by leveraging advanced data analysis techniques to explore textual input to policy debates. We focus on one recent consultation—that on the EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM)—and use a combination of natural language processing and network analysis to explore business actors’ inputs. This approach enables us to use text to identify the key topics of concern to these interests and how they differed across affected actors, providing detailed and nuanced insights on the perceived likely effects of the policy shift. We supplement this with data on trade flows to contextualize our analysis.

Insights on the positions of business interests are particularly useful in contexts where a proposed policy is very novel, such that there is a lot of uncertainty about the likely impacts. The CBAM—the world’s first effort to put a price on imported carbon—also referred to as a ‘carbon tariff’—is such a measure. It is the first time a major economy has sought to use trade policy to level the playing field on carbon pricing and it has been very controversial. It thus provides an ideal opportunity to leverage new analytical tools to explore policy debates.

As discussed below, the effects of CBAM in trade and trading partners are still largely unknown. The objective of the measure is to encourage other jurisdictions to follow the EU’s lead in making carbon more expensive, but it is unsure whether that will happen. In the face of such uncertainly, it is vital for policymakers to collect inputs from interested economic (and other) actors to supplement their own analysis. Yet the number of inputs provided is challenging for interpretation, especially those that use free text rather than answering closed questions. Indeed the Commission’s own analysis of the consultation only reports the findings of the closed questions (CEC, 2021a). This represents a missed opportunity to mine such data to provide a more nuanced understanding of actor’s positions and how they cluster together.

The objective of this paper is to demonstrate how analysis of the textual data provided to the public consultation can inform understanding of the likely effects of novel policy proposals on international business. In general, only companies and sectors which consider their core interests to be affected engage in political debates in the EU (Curran & Eckhardt, 2022; Kinderman, 2021). Although inevitably biased towards exposed sectors, inputs nevertheless highlight the key concerns of stakeholders on proposed regulation and provide a rich source of data on the most salient issues.

Our approach allows us to identify clusters of stakeholders with similar concerns. In addition, by differentiating between types of actors (collective vs. individual; EU vs non-EU), we can more precisely identify variations in business positions on the regulation. Our key findings include the fact that EU-owned companies clustered together, while those owned by third-country actors clustered separately and that collective actors and indirectly affected sectors tended to be less concerned about the negative impacts of the new measure on international relations and governance than individual firms and those directly affected.

The paper is structured as follows, after a brief introduction to the debate on CBAM, we explore what we know about its operation. We then introduce our methodology for the analysis of perceived potential effects, providing details, in particular, on our novel approach to analyzing business positions on the proposal, before presenting the key findings which emerge. We conclude by highlighting the potential of leveraging sophisticated techniques for textual analysis in support of future research in IB and policy, as well as providing some tentative indications of the short- and long-term impacts of CBAM. We also suggest avenues for future research to assess the actual impacts of this regulatory innovation on trade, investment and international business more broadly.

A novel measure to deal with carbon leakage: the CBAM and its discontents

The CBAM has been a long time in the making. The EU first put a price on carbon in 2005 through the ETS, which capped emissions from the most carbon-intensive industries and allowed companies that produced less than their quota to trade unused emissions ‘credits’ with installations that found it harder to limit emissions. From the outset, there was much concern about the potential for such climate action to have negative effects on the competitiveness of EU industry, in particular if EU firms relocated production to less-regulated countries, exporting their carbon emissions—so-called ‘carbon leakage’ (Graichen et al., 2008). There were discussions at the time about a mechanism to adjust for carbon costs at the border (Curran, 2010). However, in the face of the operational and political difficulties of border tax adjustment, the compromise solution to address the risk of carbon leakage and level the playing field, was to provide ‘free’ ETS carbon allowances to carbon-intensive sectors subject to import competition (CEC, 2009). Probably as a result, analyses found that there was little evidence of carbon leakage during the roll out of the ETS (ECORYS, 2013).

The EU is now redoubling its efforts to reduce carbon emissions and carbon costs will need to rise if the region is to achieve its declared aims of carbon neutrality by 2050 and a 55% reduction in carbon emissions by 2030 (Böhringer et al., 2018; CEC, 2021b). Although the complexities of border tax adjustment have not disappeared, this evolving context made such action more of a political imperative (Mehling et al., 2019). The von der Leyen Commission formally proposed the CBAM in 2021 (CEC, 2021c).

After a long negotiating process, it was finally agreed in May 2023. It is controversial, not least because it is one of a raft of EU trade-related measures linked to sustainability concerns (Moens & Mathiesen, 2023). Economists are skeptical about the effectiveness of such measures (Böhringer et al., 2018). Other mechanisms to deal with carbon leakage have been proposed (Leal-Arcas, 2020), such as ‘Climate clubs’ of like-minded countries (Nordhaus, 2015), or a minimum carbon price, an idea supported by the IMF (Parry et al., 2021).

One of the key concerns of its critics is that CBAM will result in ‘resource shuffling’. This refers to a scenario where MNEs export their most carbon-efficient goods to the EU, while continuing to serve other markets with their carbon-intensive goods (Böhringer et al., 2018; Kardish et al., 2021). This practice will be difficult to police and has the potential to seriously undermine the utility of CBAM as an environmental tool. The fact that the EU has chosen to ‘go it alone’ on CBAM is likely to reduce its effectiveness (Perdana & Vielle, 2023). The hope is that other large traders will follow the EU’s lead and that CBAM-like policies will be globalized, but this outcome is by no means certain. There are also fears about negative impacts on relations with important geo-political allies like Ukraine (even before the invasion) and Turkey (Erixon, 2021), as well as the implications for certain developing countries (Böhringer et al., 2018; Curran, 2010; Erixon, 2021; Godin & Magacho, 2021).

It seems likely that it will be challenged in the World Trade Organization (WTO) (Overland & Sabyrbekov, 2022), although the Commission has argued that the measure is WTO-compatible. Some observers consider that it could not be justified under Article XX, the GATT article usually cited to secure exceptions for environmental measures which impact negatively on trade (Bacchus, 2021). There is concern about the wider impact on the WTO system of a key member implementing a measure which many consider to stretch interpretation of its rules (Bacchus, 2021; Erixon, 2021; Hufbauer et al., 2021). The wider impacts of CBAM on the international trading system are important, especially in a context of heightened political tensions post-COVID and the war in Ukraine, but any forthcoming WTO challenge will take several years to conclude.

A more immediate concern is that trade partners effected by CBAM will retaliate against EU products and tension could spill over into other sectors, with unpredictable results (Erixon, 2021). We have seen this in the past, with conflicts over aircraft subsidies impacting olive oil exports (Hammami & Beghin, 2021) and contentious steel tariffs spilling over to whiskey and motorbikes (Muhammad & Thompson, 2022). While a deterioration in trading relations with several partners following the implementation of CBAM is, to some extent, a given, exactly how this will affect trade and trading partnerships is impossible to predict with any precision at this stage. As discussed below, many important aspects of its operation are still being defined.

Given this context, we would expect international companies to be concerned about the potential effects of CBAM. From a business point of view, we would expect more short-term concerns on the potential effects on operations, trade, and production to dominate inputs. Prior research has found that threats to global trade governance from populism and the fragilization of WTO have attracted little concern from business actors, especially individual companies (Curran & Eckhardt, 2022). They tended to take the global trading system for granted and did not see the need to mobilize in defense of the status quo. However, in a more fractious geo-political context post-Covid, the importance of global governance may be more salient for companies. The nature of business concerns and their variation across stakeholders are explored in our detailed textual analysis below.

The operation of CBAM: coverage, practicalities, and likely impacts

Coverage

A key question for the CBAM is what goods will be covered? The practical and methodological challenges of calculating embedded carbon are substantial. There are many products which are both carbon-intensive and heavily traded, and which could, therefore, be considered relevant for the measure (CEC, 2021b). However, rather than seek to cover all goods from the outset, the Commission chose to focus on goods which are particularly carbon-intensive and, importantly, are covered by the EU’s own internal ETS (CEC, 2021c). The exact tariff lines targeted were subject to some debate. They are detailed in Annex I of the Regulation. The decision to focus on ETS sectors meant that certain products which may be vulnerable to carbon leakage (like glass and plastics), although cited in early Commission analysis (CEC, 2021b), were not included in the final proposal. The industries which the EU Commission proposed to include were cement, electricity, certain fertilizers, and most iron, steel, and aluminum intermediate products (CEC, 2021c).

The scope of the regulation has been subject to extensive discussion between the European Parliament (EP) and Council during the legislative process and the final version (CEC, 2023a) includes hydrogen (at the insistence of the EP) (EP, 2022) and some downstream products, especially some articles of iron and steel (at the insistence of the Council) (Council of the European Union, 2022). The scope may yet expand relatively quickly after adoption, as the Commission is committed to assessing whether further sectors can be included, even before the CBAM comes into force.

Another, equally important question is whether all non-EU countries will be affected by the CBAM? There is the potential for third countries to be exempted—Annex III countries in the Regulation (CEC, 2023a). This is the case for countries where the ETS applies (primarily Norway and Iceland), but also for countries with a carbon price which exceeds that of the EU. The process of achieving such equivalence has not yet begun, and in early 2024 there were no such countries included in Annex III.

Enabling third-country accreditation is a key feature of the external aspect of the CBAM. In effect it is an effort to use ‘market power Europe’ (Damro, 2012) to force/encourage other countries to follow the EU’s lead and increase their domestic carbon prices. It has been credited with stimulating the upgrading of carbon pricing in Turkey (Konrat, 2021) and Russia, prior to the invasion of Ukraine (Zabanova, 2021). The Commission is now setting out, in detail, how this system will operate under a so-called ‘implementing regulation’.

As with other aspects of the system discussed below, the devil will often be in the details of these operational modalities (Chartier, 2023). Whether third countries will be excluded from the CBAM and on what basis, will clearly involve both technical and political assessments. The question of whether and how to provide a temporary exemption for Ukraine will be one of the first exercises in balancing these two factors (Merkus & Norell, 2023).

Although the Regulation will differentiate between countries on the basis of whether (and how) they regulate carbon emissions, there is also the possibility for individual companies which produce in a more carbon efficient manner than their country average to apply for carbon credits. Third-country installations can provide direct (and verified) data on their carbon emissions and costs to the CBAM registry, which importers can then use as default values. The system thus combines a country-based approach with flexibility under which some companies can secure more favorable conditions. This creates an incentive for MNEs and other exporters to reduce the carbon intensity of (some of) their facilities, differentiating themselves from others in the same jurisdiction. There are concerns, however, that this capacity to submit individual carbon tallies for more sustainably produced goods could encourage the ‘resource shuffling’ discussed above, as MNEs simply direct their ‘clean’ production to the EU market.

How will the system operate?

The new measure will not be fully applied until 2026, although from October 1, 2023, importers already had to detail the carbon content of their goods in customs declarations. This trial period is intended to give traders the opportunity to get used to the operation of the system before they actually have to pay for the cost of embedded carbon. However, there was little time for them to adapt before it entered into force. The Commission only published the details in mid-August 2023 (CEC, 2023b).

EU importers of covered goods now have to submit a CBAM report every quarter to a special repository set up by the European Commission. The details required include the goods imported, where they were produced (the exact facility), the total embedded emissions (including those from the production of inputs to the goods and electricity used in the production process) and any carbon costs incurred in the producing country, as well as any rebates received. The methodology for converting third-country carbon costs to EU equivalents is defined in an implementing regulation (CEC, 2023c), however only explicit carbon costs are credited. Policies which may have equivalent effects, like incentives to reduce emissions, are not currently included in the proposed methodology. This means that securing carbon credits for goods from countries with very different approaches, including the US, will likely be challenging (Benson et al., 2023). When fully operational, reporting will be annual, and reports will need to be accompanied by proof that the required value of CBAM certificates has been procured. The costs of these certificates will mirror the cost of carbon on the EU’s ETS market and will increase in line with the planned phasing out of free emissions to equivalent EU producers.

Finally, the system allows for the possibility that the actual emissions related to the production of some goods cannot be determined. In this case, a default value will be applied, based on either average emissions data for the country of production, or the average emission intensity of the worst performing EU installations. There are concerns that using averages will disincentivize decarbonization, as more advanced companies may have to pay twice—once for decarbonizing investment and again at the EU border (Benson et al., 2023). The system will include penalties for non-conformity and fraud.

Impacts on EU companies

Although the prime objective of the CBAM is to level the playing field between EU and non-EU producers, the impact on EU industry will be non-negligible. Firstly, because free ETS allowances will simultaneously be phased out. Most observers consider that the effectiveness (and WTO compatibility) of the CBAM depends, at least in part, on this linkage (Gisselman, 2020). These free allowances were instigated in the first place precisely because of the unlevel international playing field created by higher carbon pricing in the EU through the ETS (CEC, 2009). Nevertheless, the EU industry is lobbying hard to avoid their elimination. A trade association representing energy-intensive industries, AEGIS, commissioned an ‘independent’ study that purported to show that such free allowances can be maintained in a WTO-compatible manner (King & Spalding, 2021).

Secondly, there are concerns about the negative impacts of CBAM on EU exports. While the measure will protect EU goods sold within the community from unfair competition from goods which do not pay carbon costs, EU exports will need to compete globally despite these costs. Although there are mechanisms to deal with this, such as providing rebates, or giving free carbon allowances to exports, these are judged to be problematic from the point of view of WTO compatibility. The Commission has been tasked with assessing the risk of such export-related carbon leakage by 2025 and, if necessary, developing a WTO-compatible means of addressing the problem.

Thirdly, there will be supply chain effects in downstream industries in the EU. Carbon-intensive inputs to sectors like cars, bicycles, and even agriculture will become more expensive, pushing up the costs of EU production. These goods will compete with those from other jurisdictions that do not have to pay for the embedded carbon in intermediate goods, both in the EU and in third-country markets. There is a concern that this situation will greatly disadvantage the EU’s downstream industries at home and abroad. These wider supply chain effects were certainly one of the reasons why, as we will see below, many sectors that were not directly impacted by the CBAM nevertheless provided inputs to the public consultation.

Analyzing the potential impacts of the CBAM

Approach and methodology

To explore the likely impact of these proposals we took a two-pronged approach. Firstly, we identified the most affected sectors and actors by looking at historical trade flows. Based on the Harmonized System (HS) codes in the final text defined as covered by the CBAM (CEC, 2023a), we extracted figures from the International Trade Center (ITC) on EU tradeFootnote 1 in recent years. This enabled us to specify which sectors and trade partners would be most heavily affected by the policy. As 2020–2022 were quite atypical years for trade in these products, both because of the pandemic and the war in Ukraine, we present averages both for the last 3 year and over a longer period (2015–2019).

It quickly became clear from the data that the inclusion of electricity (HS 2716) distorts the figures considerably for two reasons. Firstly, there was a huge surge in electricity imports by value and volume in 2021–2022 because of the energy crisis caused by the war in Ukraine, which increased demand and, especially, price.Footnote 2 Total EU imports amounted to over $100 billion in 2022 (compared to $22 billion in 2019), making up a fifth of CBAM imports. Secondly, most of the electricity imported into the EU comes from within the block (71% in 2022), or neighboring countries, linked to the EU grid, which are unlikely to be strongly affected by CBAM (another 17% comes from UK, Switzerland, and Norway). We therefore present the trade figures excluding electricity, to get a more realistic view of the most affected countries exporting CBAM goods to the EU.

Secondly, we explored business attitudes through the analysis of inputs provided to the EU’s public consultation on the proposed regulation.Footnote 3 In general, EU business reacts to regulatory proposals based on their perceived interests and industry mobilization is a good indicator of the extent of concerns/support. As discussed above, academic researchers have only recently begun to mine these sources to better understand political debates (Abel & Mertens, 2023; Frelih-Larsen et al., 2023; James et al., 2021; Langhof et al., 2016).

Much of the input to the consultation on CBAM was provided in an on-line questionnaire with closed questions, which the Commission analyzed in its own document in 2021 (CEC, 2021a). This summary combined inputs from all respondents, such that the outcome was very general, and it does not give us a sense of the variation across actors with different interests. Most importantly civil society inputs were combined with those of business and non-EU actors were combined with those from the EU. In addition, only the responses to the closed questions were analyzed. These were generally on a Likert scale from 0 to 3. Thus, concerns on the unnecessary burden on business had a score of 1, although there are certainly some businesses for which this is a major issue. Despite the variation in interests responding to the questionnaire, most agreed that the most important economic impact of CBAM would likely be the increase in costs for downstream sectors (2.24/3).

Our objective was to explore the concerns of business, as well as the differences across business interests. To do this, we focused our attention on the specific submissions to the consultation, which were usually submitted in parallel with the questionnaire. These used free text and went into much more detail about the positions and concerns of the actors in question than was possible in the questionnaire. They also provided the possibility to highlight issues that had not been addressed in the closed questions. There were 224 such inputs altogether. As 600 respondents filled in the questionnaire, this implies that quite a large share of respondents thought it useful to provide supplementary information. We focused on feedback from business and differentiated between different types of actors to get a more nuanced view. There were inputs from 45 individual EU companies, 24 non-EU organizations (both companies and trade associations) and 80 EU trade associations. These submissions were often very detailed and ran to several pages. By focusing only on those business interests which were sufficiently engaged to provide additional position statements we are clearly exploring the attitudes of the most affected economic actors. However, we believe that this choice is justified, given our interest in mobilizing the text to highlight the key perceived impacts.

Our methodological approach is based on network analysis, which is not an uncommon method in international business studies (Buchnea & Elsahn, 2022; Kurt & Kurt, 2020). For example, longitudinal datasets of formal linkages between firms have been leveraged to explore how connectedness between company clusters improves innovation performance (Turkina & Van Assche, 2018). Others have explored how cross-border relationships impact the social capital, power, and social influence of international businesses (Sultana & Turkina, 2020). Network analysis has also been used to analyze the centrality of organizations in institutional networks using qualitative data collected through questionnaires (Monaghan et al., 2014). While our method does share some similarities with this prior scholarship, our data is very different. Instead of using relational data, we start from textual data to identify clusters of organizations and companies with similar concerns, as well as the topics discussed within each cluster.

To do this, we employ a combination of natural language processing and network analysis. In recent years, these techniques have built on seminal early work (Bail, 2016; Rule et al., 2015) to enable new approaches to understanding how text helps us to illuminate policy positions and their evolution over time. The sheer size of the data provided to EU consultations is challenging for manual analysis, such that some early work analyzed a random sample of submissions (Langhof et al., 2016). The more sophisticated techniques now available enable us to integrate all inputs into our analysis.

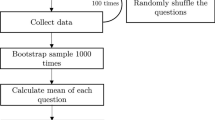

The first step in the process involved excluding non-informative content such as stop-words and infrequent words (occurring less than twice). Lemmatization was then applied to group inflected word forms together, enabling the consolidation of words with common roots (e.g., “imported” and “imports” are combined as “import”). The resulting selection comprised a total of 63,326 words with the following distribution: 22,257 observations from companies, 9618 from non-EU organizations, and 31,451 from trade associations. Figure 1 provides details on the top 20 most frequently occurring words in the different submissions. We excluded uninformative words occupying the first positions like “carbon”, “eu”, “cbam”, “border” and “mechanism”. In terms of the other words, (carbon) leakage was a key concern in all submissions, especially those from companies. ‘Risk’ was also important for both companies and trade associations, while ‘climate’ was important for all. Concerns about WTO compatibility were expressed more by companies, although non-EU actors highlighted ‘international’. ‘price’ and/or ‘costs’ were important for all, as was the link to the ETS.

In the next step of our analysis, we applied a method that involves creating connections between documents using a two-mode network projection, which is based on the words appearing in the texts. The result of this process is a weighted adjacency matrix, obtained by applying the term-frequency inverse-document frequency (TFIDF) to overlapping terms between pairs of documents (Bail, 2016). There, each cell counts how many times a word appears in each pair of documents. This matrix not only represents the co-occurrence, but also the strength of relationships between words in the dataset.

Using this matrix, we can create a two-mode network where nodes can either be documents or words. In the first case, nodes represent documents and edges represent the number of words co-appearing in both documents. In the second case, we use words as nodes and the edges represent the co-appearing of other words within the same document. As indicated, the co-occurrence of words is a continuous variable, allowing us to quantify not only who is similar to whom, but also the strength of this similarity. Therefore, larger edge weights indicate greater association between organizations (Neal, 2022). For example, if two documents have only one word in common, their relationship strength will be lower than another pair of documents with hundreds of words in common. Similarly, if two words appear together in a single document, their association will have lower weight compared to words that co-appear in several documents. However, since we are dealing with text networks, every word has a high probability to appear in all documents, therefore we need to extract statistically significant connections. To do so, we applied the backbone extraction technique (Neal, 2022), which reduces network complexity by isolating a subgraph containing only the significant edges. The disparity filter (Serrano et al., 2009) was employed to retain edges with weights that significantly deviate from a null model, using a statistical significance level of α = 0.05.

The process is as follows. First, we prepare the data. This step involves tokenizing the text into words, deleting stop words, and lemmatizing them. Then, we create a document-term matrix (DTM) and a term-document matrix (TDM) where rows represent documents/terms, columns represent terms/documents, and the matrix elements represent term frequencies of co-occurrence. Secondly, we create a weighted adjacency matrix, where each cell represents the strength of the relationship between two documents or words based on the overlapping between them (either by document or by word). The third step involves the two-mode network representation. For the document-node network, each document is a node, and the edges represent the strength of the relationship based on the number of words co-occurring in both documents. For the word-node network, each word is a node, and edges represent co-occurrence of words within the same document. Our next step involves applying the backbone extraction technique to isolate a subgraph containing only statistically significant edges, retaining edges with weights significantly deviating from a null model (α = 0.05). After doing so, we obtain two types of networks. In the case of the documents network, it allows us to analyze similarities between organizations, while the case of the words network allows us to identify topics being discussed in the documents.

This method differs from previous alternative approaches to textual analysis of public consultations (James et al., 2021). First, our approach provides a network representation, offering a visual and quantitative understanding of the relationships between organizations based, not only on the presence –or not—of common topics, but also accounting for the strength of these shared concerns. Secondly, the use of backbone extraction and the disparity filter introduces statistical significance measures, contributing to a more robust identification of meaningful connections. This ensures that the extracted connections are not merely coincidental but are statistically significantly different from the null model, contributing to the reliability of the results. Third, our method not only facilitates the identification of clusters of organizations but also enables the discernment of relevant topics within each cluster. This is achieved through the same process by modifying the bipartite projection under analysis (nodes as organizations or nodes as words).

Identifying clusters of organizations

The Louvain algorithm is a popular and efficient method used for community detection or clustering in network analysis. Since first introduced in 2008 (Blondel et al., 2008), it has gained widespread recognition for its ability to identify cohesive subgroups or communities within complex networks. The algorithm operates in a two-step iterative process. In the first step, it optimized the modularity of the network by iteratively moving nodes between communities to increase the overall modularity score. Modularity is a measure of the density of connections within communities compared to connections between communities, indicating the strength of community structure in a network. In the second step, the communities identified in the first step were treated as individual nodes, and a new network was constructed based on the community structure. The same modularity optimization process was applied again to further refine this structure. This iterative process of moving nodes between communities and optimizing modularity was repeated until no further improvement in modularity could be achieved.

For example, in a network of documents, each node (document) is considered as its own group. Then, the algorithm looks at each node and asks, “Would moving this node to another group create a better-organized community?” This is assessed based on the density of connections within the community compared to connections between communities (modularity score). If moving a node improves the overall organization, it is relocated to another community. The process is repeated, with nodes continuously shifting to enhance the network's structure. Then, the entire process is repeated until no further improvement can be made, indicating that the network has reached a stable community structure. After several iterations, the identified communities are treated as individual entities in a new network, which in our case represents either communities of organizations sharing common concerns, or communities of words that represent latent topics in the documents. After applying the Louvain algorithm to our sample of organizations, we identified three clusters of EU companies, five clusters of non-EU organizations, and eight clusters of trade associations. These are represented visually in Figs. 2, 3 and 4.

Identifying topics

To identify topics, we used the same network created for identifying clusters of organizations. However, since it is a two-mode network, instead of focusing on organizations, we focused on words. The process began by subsetting each organization cluster and their associated documents. Then, we calculated a word co-occurrence matrix which captures the joint appearances of words within each cluster. This matrix was then used to compute a measure of word relatedness, resulting in a weighted network where nodes represent words and edges represent connections between these words, with weights reflecting their level of relatedness. Again, the backbone of each network was extracted using the method introduced by Serrano et al. (2009), which retains statistically significant links deviating from a null network model. Subsequently, the Louvain community detection algorithm was applied to identify cohesive subgraphs, referred to as “topics”. In this study, topics were labeled manually based on the words that constitute them. For example, topics featuring words like “CO2, import, increase, cost…” were categorized as “Import Costs,” while topics consisting of words such as “consumer, farmer, pesticide, plant protection, substance, treatment” were labeled as “Effects on Agriculture.”

Differentiating by impact

We know that business may hold quite heterogeneous positions on proposed policy change (Abel & Mertens, 2023), not least because regulatory shifts impact differently across sectors depending on their production structure and position in value chains (Curran & Eckhardt, 2018). This variation across companies and between firms and their trade associations seems to be increasing over time in the EU (Hanegraaff & Poletti, 2021). To explore the extent to which the position of business varied depending on their level of exposure to direct and indirect effects of CBAM, we differentiated between those directly affected by CBAM, as proposed by the Commission (steel, cement, etc.) and those indirectly affected through downstream effects on their supply chains (bicycles, cars, etc.). There were also several submissions from sectors like glass, ceramics, plastics, pulp and paper, not initially targeted by the Commission proposal, but discussed in their initial analysis as potentially subject to the CBAM because of their high emissions and high trade intensity (CEC, 2021b). We labeled these “debated sectors”.

As the objective of CBAM is to level the playing field, one would expect those directly affected to be rather supportive, beyond the concerns about ‘losing’ free carbon credits and consequent potential negative effects on their export competitiveness. We would expect downstream sectors to be concerned about increased costs for their imported intermediates impacting their competitiveness both at home and abroad. Finally, “debated” sectors would be expected to be concerned about their exposure to competition from low-cost imports, as the increasing cost of their carbon use in EU production will not be offset by the CBAM.

To explore differences between collective and individual positions, and internal and external actors, we also differentiated between EU trade associations, EU companies, and non-EU actors (both companies and associations). As discussed below, differentiating between these latter two groups was not as straightforward as might be expected, as several ‘EU’ companies were subsidiaries of non-EU multinationals. Interestingly, the clustering exercise which we undertook clearly differentiated these from the other submissions. In terms of collective versus individual action, recent research on the reaction of EU industry to protectionism found that individual companies did not mobilize on more generic threats, such as that to the WTO, leaving this to their trade associations (Curran & Eckhardt, 2022). We would thus expect individual companies to be focused on the direct effects of CBAM on their business models, with trade associations taking a more holistic and wide-ranging approach, for example expressing concerns about the effects on international relations and trade governance.

Findings: which trade partners and products will be most affected by CBAM?

CBAM is a very targeted policy measure. To put our analysis into context, it is important to understand which trade flows will be affected. The ITC figures we extracted indicate that the average value of total EU imports of CBAM goods (minus electricity) was $254 billion in 2015–2019, rising to $332 billion in the period 2020–2022. The first insight from the figures is that most of the EU’s imports are from within the block. The post-Brexit EU27 has consistently made up over two-thirds of EU imports, with the average figure standing at 67.2% in 2020–2022. Obviously, EU internal trade will not be affected by CBAM, so we focus here on extra-EU imports, which averaged $109 billion in 2020–2022, up from $79 billion in 2015–2019.

The market share of the main suppliers of CBAM products is presented in Table 1. The country that will be most affected by the CBAM is China, whose share of these EU imports was 14.7% in 2020–2022, similar to the 2015–2019 average. The next most affected country is Russia, whose exports to the EU have continued, despite the invasion of Ukraine, but at a lower level (10.6%, against 13.2% on average over the 5 years to 2020). Overall, the table indicates that, while China has long been an important supplier of these products to the EU, there has been some shifts in the importance of others. Historic suppliers like the UK, Norway, Switzerland, and the US are becoming less important, with an increase in the share of Turkey and India. The war in Ukraine had a major impact on trade, with Russia’s exports of CBAM products to the EU falling by 17.5% to $12 billion in 2022, while intra-EU trade increased by 13% and imports from China rose by 45% to $22 billion.

Vulnerability to policy change varies across the most important suppliers. Switzerland and Norway are integrated into the ETS and are included in Annex III of the Regulation (CEC, 2023a), so will not be subject to the CBAM. The UK is not yet included in the Annex, but is seeking to avoid the mechanism and has launched a consultation on plans to set up its own equivalent (HMSO, 2023). It is likely that a solution will be found to exempt Ukraine (Merkus & Norell, 2023), while it is probably safe to say that the CBAM will not be the main sources of trade tensions with Russia in the near future.

Of the other key suppliers Turkey, as mentioned above, is redoubling its carbon reduction efforts and looks likely to seek to demonstrate regulatory equivalence, although whether this will be achieved is an open question (Konrat, 2021). South Korea has its own ETS, although there are substantial differences compared to the EU scheme, making equivalence challenging (Schott & Hogan, 2022). In Taiwan, several efforts to implement a carbon tax have failed in recent years (Chou & Liou, 2023), making equivalence highly unlikely.

The situation also varies widely in the other three key exporters—China, India, and the US. China has its own version of ETS, however its sectoral coverage is more limited than the EU’s, the carbon price is significantly lower and the carbon intensity of production of key CBAM products such as steel is far higher (Kardish et al., 2021). India has little hope of securing equivalence and has already signaled that they will challenge the measure in the WTO (Euractiv, 2023).

The question of how to deal with imports from the US is a highly political one. The idea of a transatlantic ‘climate club’ has been floated (Falkner et al., 2022) and the EU has agreed to work with the US towards a common approach to the decarbonization of the steel and aluminum sector, as part of an agreement to reduce punitive tariffs and reduce overcapacity (CEC, 2021d). However, such cooperation is fraught with difficulties, not least because of the very different ways in which the two incentivize decarbonization (Leonelli, 2022). Any future deal is also dependent to a large extent on the outcome of forthcoming elections in 2024 (Jain et al., 2024). The assumption seems to be that US producers will rely on their declared emissions being relatively low, rather than blanket country level exemptions, although this will disadvantage smaller producers who lack the capacity to provide the required verified certification (Benson et al., 2023). Indeed, these same difficulties will apply to other smaller producers worldwide.

Here we have focused on the main traders. Several observers have pointed out that certain small countries with relatively low absolute trade levels may suffer negative effects from CBAM. These include neighboring countries like those in the Western Balkans and the near East who rely on the EU market in several CBAM sectors (Erixon et al., 2023), as well as larger developing countries like South Africa and Brazil (UNCTAD, 2021). Our analysis indicates that Vietnam, whose CBAM exports have grown rapidly to reach $3.5 billion in 2022, is also vulnerable. These negative effects will certainly create trade tensions with the risk of retaliation and a WTO challenge.

In terms of the products that will be most affected by the CBAM, we extracted data on imports of the products listed in the EU’s Regulation (at the level of HS 4 product classification) which will be subject to CBAM. Given the variability of trade in recent years, we calculated average figures over the period 2020–2022. Trade flows of several covered products are relatively small, such that impacts will be minor. For example, the inclusion of hydrogen seems unlikely to be impactful, at least in the short term. Total extra-EU imports have averaged just over $2 million in the period. In other products, flows are far more significant and extra-EU sources are often key suppliers.

Table 2 reports data on the most important CBAM products in terms of the average value of total extra-EU imports over the period, as well as the share of total imports accounted for by these extra-EU sources. Clearly, iron, steel, and aluminum and their derivative products predominate, and this sector will feel the effect of the new measure most acutely. Electricity is also very significant, but as mentioned above, although over a quarter of imports come from outside the EU, this market is mainly dominated by suppliers in the EU neighborhood physically linked to its supply infrastructure several of which are covered by the ETS. The other key non-metal sector affected is fertilizers. Across these different products there are large differences in the importance of extra-EU trade. Unwrought aluminum, semifinished iron and steel products, and ammonia have particularly high dependence on non-EU production and therefore CBAM will be particularly impactful for these goods.

It is notable that most of the products in Table 2 are intermediate goods, used in downstream industries, from construction to automobiles to washing machines. In the case of fertilizers, indirect effects are likely in agriculture. Thus, it is clear that CBAM will have an impact, not just in the sectors that will be directly affected, but also in those that will experience increased prices for their key inputs. The nature of the effects of the CBAM therefore differ considerably depending on the stage in the value chain. While the mechanism provides protection from competition for the targeted sectors (and thus we could expect them to support the measure), it will inevitably increase costs for downstream users of the affected inputs, whether these are domestically produced or imported (we would thus expect these sectors to be more concerned about competitiveness effects). This is why we differentiated between directly affected sectors and indirectly affected sectors in our analysis. As we expected, we find their core topics of concern vary.

Although CBAM will obviously not be applied to exports, there are concerns that the new regime will nevertheless affect flows. The increased carbon costs within the bloc that the measure seeks to counterbalance will inevitably impact on the competitiveness of EU exports, especially in markets where carbon is not subject to pricing systems. This is not just an issue for carbon intensive products covered by CBAM, but also for products which rely on these intermediate inputs. However, one would expect CBAM products to be the most heavily affected. In addition, there is a risk of retaliation from trade partners if they observe negative effects on their exports because of CBAM. Although, as mentioned above, such retaliation could affect non-CBAM sectors (Hammami & Beghin, 2021; Muhammad & Thompson, 2022), CBAM products would be amongst the most vulnerable.

To assess the extent to which EU exporters could be exposed to negative competitiveness and retaliation effects, we also extracted EU exports of CBAM products (minus electricity for the same reasons indicated above). The EU exported $324 billion such products on average between 2020 and 2022, up from $267 billion in the 2015–2019 period. Again, intra-EU trade accounts for most of these flows—over 74% in the most recent years. Extra-EU trade is presented in Table 3. The most important markets are the US (15.2% on average, worth $13 billion) and the UK (14.7%, worth $12 billion). The neighboring markets of Switzerland, Turkey, and Norway are also important, as is China. The EU has been increasing its dependence on traditional markets for CBAM products, like the US, Switzerland, and Norway, with a fall in the importance of the UK since Brexit, while some emerging markets like China, Mexico, and Brazil have seen slight increases in shares.

Although agreements on equivalence may be found with some key trade partners, calming trade tensions, it is unlikely to be the case for all. Exports to the US and China are probably the most vulnerable to negative repercussion from the new EU carbon regime, both because neither have equivalent carbon costs (thus production should be cheaper) and because they have not hesitated in the past to retaliate against perceived discrimination against their exports (Furceri et al., 2023; Li et al., 2018). Combined exports to the two markets were worth an average of $18 billion in the period 2019–2022.

Finally, these figures represent the flows in sectors currently covered by the measure. The impact of the CBAM would become more significant if the Commission expands its scope. One of the largest sectors which had been proposed for CBAM (by the EP), but not retained in the final version, is plastics (HS39). Its inclusion at a later stage would be very impactful, as extra-EU imports in this sector averaged $72 billion in 2020–2022, 40% of which came from China or the US. Other sectors mooted in the original impact assessment as carbon intensive, but excluded from the final proposal, include ceramics, glass and pulp and paper (CEC, 2021b). While these products will not be subject to the CBAM in the short term, one would expect producers to be following the proposal closely, although they will likely have different concerns to those already directly or indirectly affected. Thus, we differentiate in our analysis between inputs from the latter sectors and those from ‘debated’ sectors.

Findings on business positions on the CBAM

Clusters and topics across different types of economic actors

In this section, we delve into our findings in terms of the clusters of organizations categorized by type—EU companies, non-EU organizations and trade associations. Within each cluster, we will discuss the concerns highlighted in the inputs to the consultation from these entities. We also differentiate between those sectors where the CBAM would have direct or indirect effects and those sectors where its application was (and remains) debated. We will analyze the key topics and discussions surrounding each cluster, shedding light on the specific challenges and opportunities they face in relation to the use of this novel tool.

Figure 2 depicts the cluster of EU companies as identified by the Louvain algorithmFootnote 4 and the topics discussed by them. In the following we discuss each in turn. To clarify the results for the discussion, we provide summary tables on the key topics discussed by the different actors.

In terms of EU companies, the results are summarized in Table 4. The first cluster consists of organizations primarily involved in the aluminum industry, especially subsidiaries of the Russian company Rusal. Two significant topics emerge for this group: carbon leakage and the need to address and mitigate it and carbon efficiency, focusing on minimizing the carbon footprint of specific processes or industries. Cluster 2 is the largest cluster. It encompasses a diverse range of EU companies (e.g., BASF, PwC, Repsol, Tata Steel, UPS) from industries including chemical manufacturing, energy production, consulting, logistics, and steel.

Their concerns focused on the potential for trade frictions and the implications of the CBAM in terms of its potential (in)compatibility with WTO. This topic encompasses a wide range of interconnected elements, including legal considerations, discriminatory practices, taxation, conservation efforts, and the assessment of environmental impacts of climate change. The need for consistent and effective measures and compatibility with WTO regulations was emphasized, with proposals to redesign the mechanism suggested. The potential for negative impacts on international relations was underlined. On another front, the impact on costs, including electricity costs was a concern, with discussions revolving around carbon prices, domestic policies, and the implications for EU competitiveness, especially for sectors like cement and chemicals. Thus, perhaps contrary to expectations (Curran & Eckhardt, 2022), EU companies expressed as much concern about the negative impacts of the CBAM on international relations and WTO, as on their own cost structures and industrial sectors.

Cluster 3 consists of subsidiaries of NLKM group, another Russian company, engaged in steel production, trading, and related activities. Eleven NLKM subsidiaries responded to the consultation, making essentially the same points. The notion of "avoid" takes center stage—with two key concerns—the threat of retaliation from trade partners and the negative impacts on steel users. It is notable that in terms of the company contributions, the nationality of the parent company was very influential in positioning interests. Most EU companies clustered together, whereas the EU subsidiaries of Russian companies clustered separately.

In the case of non-EU organizations, the results are summarized in Table 5 and Fig. 3.Footnote 5 We found five different clusters of organizations. The first cluster includes a diverse range of organizations related to forestry products and fossil fuels (e.g., Brazil forestry products sector and UK oil and gas sector). Their inputs focused on the global impacts of the CBAM; the potential for carbon leakage and the need to ensure an effective design, with limited administrative burden; its relation to the ETS; the practicalities of its operation and its environmental impacts. Cluster number 2—organizations that are involved in the production and distribution of carbon-related products—also focused on global impacts, especially on emissions, as well as costs, highlighting the impacts on EU production.

Cluster 3 comprises organizations in the energy sector, including renewable energy and hydroelectric power. Examples include Energy Norway and Hydro Norway. Their key topics were related to aluminum production and emissions; carbon leakage; CO2 costs of imports and the export impacts of the CBAM, including in downstream industries. Cluster 4 (Russian and Korean industry) focused on the CBAM’s impact on industry. Finally, cluster 5 consists of organizations in Ukraine, associated with transportation and steel and electricity generation. They highlighted carbon leakage and impact on imports, but also the relationship to the Association Agreement which links the EU and Ukraine, as well as the need to explore other options and accompany the transition. Overall, we see that non-EU actors also raised concerns about the CBAM’s global and bilateral impacts, as well as its impacts on costs, especially in downstream industries.

Finally, for EU trade associations we identified eight clusters, represented in Fig. 4,Footnote 6 but only five contained enough words to enable interpretation.Footnote 7 The topics discussed within these clusters are summarized in Table 6. Cluster 1 includes a diverse range of generic industry organizations, business services and representatives of energy intensive sectors, both those covered by the CBAM, like cement, potentially included, like chemicals, or indirectly affected, like rail.

Topics highlighted included those related to likely operational difficulties, including fraud, the administrative burden and impacts on consumers. Another set of concerns focused on the negative competitiveness effects of the CBAM, including market effects and the issue of phasing out free emissions permits, another addressed the potential negative impacts on investment. Concerns about value chain effects were also important, including issues related to carbon content, carbon leakage and market demand for metals as costs increase. Similarly, the topic of ‘downstream effects’, explored the implications of carbon border adjustment mechanisms on downstream industries, including allocation of emission allowances, measurement of carbon content, and support for renewable energy. Additionally, the specific topics of “Glass” and “Power” were also identified.

Cluster 2 comprises food and logistics industries. Here concerns focused on the indirect effects on agriculture, related to increasing pesticide costs and the undermining of the economic sustainability of the sector. Another key topic was the need to consider the agricultural sector in the context of CBAM and emissions reduction. The last topic focuses on considering the broader needs of the EU. Cluster 3 includes a range of industries related to steel and its downstream users (bikes, home appliances). Here key concerns related to the impact on exports and the difficulty to absorb the new costs; the indirect negative effects along the value chain; the risk of carbon leakage and consequent need for free allowances; production costs and negative downstream sectoral impacts, especially on the bicycle industry.

Cluster 7 comprises mainly mining and resource extraction. Here the key issues discussed related to whether the measure would have the assumed impact and the importance of understanding its consequences; the loss of free allowances; the negative effect on exports, potential negative effects on trade and competitiveness and increased administrative burden; national concerns about competitiveness and investment impacts; indirect competitiveness effects, especially through increasing metals prices and the impact on exports; downstream effects, especially on paper and chemicals. Finally, there was a separate topic on "Electricity Costs". Lastly, Cluster 8 includes France Chimie, and MEDEF, representing the mining, paper, chemicals, and wider business sector in France. The key issues they addressed were costs; monitoring impacts and application; coverage of the measure and impacts on energy costs.

Overall, we can see that the concerns of the trade associations are focused on the operation of the system, the administrative burden it represents, its effects on costs, trade, investment and competitiveness and the impacts of the loss of free allowances. Surprisingly, and in contrast to other recent research (Curran & Eckhardt, 2022), they seemed to be less concerned about the wider controversy that the CBAM has fostered and its potential negative impacts on international relations and the WTO. This topic seems to have had greater salience in the input from companies, as well as from non-EU actors. The latter is to be expected. Trading partners that will be hit by CBAM are likely to highlight concerns about its legality and negative externalities. That individual companies express concern about its legal basis and the potential unintended geo-political effects of the measure is more surprising.

Topics by level of exposure to the CBAM

In addition to our analysis of the topics discussed by type of organization, we also classified submissions in terms of the likely effect that CBAM will have on the sector in question as discussed above. We repeated the topic analysis for each of the three types of effects: directly affected, indirectly affected, or subject to debate.

Figure 5 shows the different topics discussed within each type of organizations in terms the extent to which they are directly affected by the CBAM. As the figure shows, perhaps unsurprisingly, directly affected organizations had the most extensive list of topics, while those sectors that were subject to debate had, both fewer topics and no interconnections between them, indicating very sector/company focused submissions. The key topics which emerged across these different sectors are summarized in Table 7.

For directly affected sectors, we could identify 14 different topics. These focused on various aspects related to carbon content and costs, including indirect impacts and pricing effects; support for reductions in carbon content, including in trade partners like Ukraine; challenges associated with the phasing out of free allowances and the need for gradual implementation of carbon pricing mechanisms and consultation; the effects on international relations and the institutional and regulatory frameworks governing international agreements, such as association agreements, dialogue, and cooperation between countries; questions about the effectiveness of the CBAM; the sectoral impact and potential alternative approaches.

Other topics included the need for a joint international approach and the relationship of the CBAM to the Paris Agreement; administrative and industry-specific issues related to carbon emissions and competitiveness; the need to take into account downstream effects and the importance of detailed measurement and data to assess this; alumina and aluminum, with a specific focus on carbon leakage, export impacts and loss of free allowances; the legality of the measure and potential retaliation by trade partners; the price impacts, especially in the power sector and policy options to deal with challenges; various sectoral challenges related to the cement industry, facility management, process innovation and the reduction of carbon emissions in specific sectors; the negative impacts on aluminum and steel production volumes. Finally, the last topic pertains specifically to carbon leakage and its implications in the context of Norway.

Overall, directly affected sectors focused on negative competitiveness and cost impacts across the value chain and operational challenges, as well as impacts on international relations. The prevailing narrative was not generally as supportive of the proposal as might be expected. Rather, even in business sectors which the CBAM aims to protect, stakeholders highlighted a wide range of concerns about its practicality and wider impacts. The system is quite revolutionary and there was a lot of concern about how it will work in practice and whether it will really help to protect EU producers of carbon-intensive goods. Indeed, affected sectors continued to express concerns as the regulatory process advanced. Eurofer, the EU streel trade association sent an open letter in May 2022 reiterating these concerns and criticizing: …a premature transition from the free allocation and indirect cost compensation system to a CBAM which has not yet been tested. (Eurofer, 2022).

Regarding indirectly affected organizations, we could identify 17 significant topics. These revolved around supply chain effects in manufacturing; carbon costs and exemptions for exporters; carbon leakage; the links to the ETS system; allocation of emission allowances and the need for reliable methods for calculation; the impacts on the agricultural sector; the impact on carbon intensive industries and efforts for carbon content reduction; the need to negotiate with neighboring countries, especially Switzerland; the exemption of certain jurisdictions from the CBAM, including legal aspects and design options; questions about the equivalence of other countries’ systems; concerns on the methodology and the need for transparency.

Other topics highlighted industrial effects, the risk to competitiveness and the need for compensatory measures; downstream industry risks and the availability and reshoring of raw materials and components, especially for the bicycle industry; the concerns of the forest and pulp and paper sectors; the need for gradual roll out of policy change and the importance of public consultation and transparency in decision-making processes. The final topic revolves around the sustainability of investments and the role of the financial sector in driving emission reduction efforts.

Overall, these indirectly affected organizations were concerned about the practical aspects of implementation, including the question of exemptions for certain trading partners, as well as cost and competitiveness issues, including along the value chain. Issues of potential negative geo-political fallout were not salient for this group of actors, whose core concerns were very much focused on their own interests. This could be related to the fact that indirectly affected sectors have not been heavily involved in the prior debates on the ETS and are thus less well aware of the international fallout from CBAM. It seems that they saw a complex and novel new system which will increase the cost of their inputs as THE key concern and reacted accordingly.

Finally, for those representing debated sectors, we could identify six significant topics. These focused on the glass sector and the need for consultation and different approaches to address carbon emissions in the EU container glass industry; competition from China and the implications for manufacturers and investment; product specific risks and the allocation of resources; the challenges in the flat glass industry; the need to assess the competitiveness impacts and the importance of understanding and addressing the impact of carbon taxes. Thus, it seems these organizations were very much focused on their own sectoral concerns, linked to the fact that, without the CBAM, these sectors are more exposed to the negative competitiveness effects which will emerge from higher carbon costs. Like the indirectly affected sectors, these industries were not, generally, subject to the ETS and thus less involved in prior debates about international implications. In addition, they are generally intensive users of electricity and were worried about the increased costs of power generation linked to reduced free credits.

Overall, these findings indicate that concerns about the CBAM were wide-ranging, with all actors expressing apprehension about its practical implementation, its impacts on competitiveness and on the wider EU value chain. The level of concern on its impact on the trading system and international relations varied, with directly affected companies, overseas actors and individual firms expressing greater unease on this issue than trade associations, or actors from indirectly affected or debated sectors. Of course, inputs to consultations are likely to be biased towards concerns. Companies and trade associations rarely fully support all aspects of a policy proposal and we see here that they use the consultation process to highlight issues they think need to be addressed in the revision process.