Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic has posed formidable challenges to economic mobility and corporate expansion. Among these challenges is its pronounced effect on knowledge innovation, a cornerstone upon which many organizations depend. To re-establish the flow of internal knowledge, organizations are compelled to refine their knowledge management strategies and amplify employees’ motivation and eagerness to share and transfer information. This study delves into the influence of knowledge management processes on employees’ knowledge-sharing and transfer behaviors, viewed through the lens of the social exchange theory. It also probes the role of social capital in fostering and augmenting employees’ involvement in refining these processes. Data was gleaned from 30 information service firms in mainland China, resulting in 483 valid responses. Our findings highlight that both relational and structural forms of social capital positively influence the knowledge management processes, subsequently enhancing employees’ knowledge-sharing and transfer behaviors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Over the past two decades, the topic of knowledge governance has garnered significant interest within the academic realm, resulting in a plethora of studies and diverse conclusions (Hu et al., 2019). The economic implications of the COVID-19 pandemic have hindered the propensity for effective information exchange among employees, thereby attenuating the momentum toward knowledge innovation and management in various firms (Pemsel et al., 2016; Hu et al., 2019). Hence, it becomes imperative to adopt a robust knowledge management strategy to invigorate knowledge innovation within the workforce. The knowledge management process serves as a structural mechanism, designed to streamline, invigorate, steer, and oversee knowledge management initiatives and other pertinent activities within an entity (Ye et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2019). The Knowledge Management Process (KMP) is a foundational framework within organizations aimed at creating, sharing, utilizing, and managing the knowledge and information possessed by the entities (Zaim et al., 2019). KMP encompasses several core activities, including but not limited to, knowledge creation (Syed et al., 2021), storage/retrieval (Al-Emran et al., 2018), transfer (Borges et al., 2019; Cao et al., 2022), and application (Farooq, 2019). This process facilitates the efficient and effective management of organizational knowledge resources, supporting the achievement of goals such as innovation (Ahmed et al., 2019; Fang et al., 2013), competitive advantage (Peng et al., 2023), and continuous improvement of practices and processes (Shahzad et al., 2020). While evidence underscores the profound influence of this process on knowledge sharing (Al-Emran et al., 2018; Hu et al., 2019), the nuances of informal knowledge governance remain somewhat underexplored, leaving interrelationships between associated variables ambiguous (Chuang et al., 2019). Acknowledging the paramount importance of information for enterprises, a growing contingent of scholars posits that knowledge stands as a pivotal asset, ushering in benefits related to customer satisfaction and competitive edge (Mothe et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2019). Moreover, the knowledge management framework offers advantages like operational continuity and agile adaptability to environmental shifts—including the economic turbulence instigated by the COVID-19 pandemic—which can engender trust amongst stakeholders and clientele (Albort-Morant et al., 2018; Hu et al., 2019). This study aspires to illuminate the merits of knowledge management processes, extending novel insights into the discourse (Chuang et al., 2019).

This study postulates that through social exchange mechanisms, employees can bolster their positive affective orientations towards their peers, consequently aligning their behaviors more closely with the tenets of the knowledge management process (Hu et al., 2019). Social exchange mechanisms refer to the interpersonal interactions and social behaviors within an organization that facilitate the sharing of knowledge, grounded in mutual trust and reciprocal benefits. These mechanisms may include but are not limited to, mentoring relationships (McFadyen and Cannella Jr, 2004), team-based collaborative projects (Janowicz-Panjaitan and Noorderhaven, 2009), and systems that reward contributions to collective knowledge pools (Gagné et al., 2019). Such practices foster a culture where trust is paramount, and knowledge is exchanged as part of reciprocal social interactions, creating an environment conducive to innovation and collaboration (Adler and Kwon, 2002). To achieve more notable results in knowledge exchange, management must nurture these social exchange mechanisms. This involves instituting policies that promote reciprocal knowledge sharing, such as establishing mentorship programs that pair less experienced employees with more seasoned colleagues (Bolino et al., 2002), deploying collaborative platforms that encourage cross-functional dialog and idea exchange (Reagans and McEvily, 2003), and adopting leadership approaches that prioritize open communication and mutual support within the team dynamic (Le and Lei, 2018). Additionally, management should work towards breaking down silos within the organization to enhance cross-functional collaboration and ensure that knowledge flows seamlessly across departments and teams (Cao and Xiang, 2012). This assumption is grounded in the theoretical framework of the social exchange relationship that exists between organizations and their constituents (Chuang et al., 2019). The established codes and relational dynamics are anticipated to catalyze the dissemination of knowledge within employee cohorts (Wang et al., 2019). Those beneficiaries of such shared expertise are theorized to reciprocate emotionally with the knowledge sharer, invoking a virtuous cycle of interaction consistent with Bearman’s (1997) conceptualization of social exchange. It is noteworthy that certain scholars have identified persisting lacunae in the literature concerning knowledge management processes (Chuang et al., 2019). Empirical findings delineating the motivations and modalities of information propagation and transference remain nebulous, notwithstanding the considerable scholarly attention directed toward the intricacies of the knowledge management process (Al-Emran et al., 2018; Hu et al., 2019).

Historically, academic discourse has gravitated more toward the availability of information-sharing platforms than the intrinsic motivational drivers underpinning knowledge sharing (Wang et al., 2019). However, numerous empirical inquiries have corroborated that the knowledge management architecture intrinsically augments knowledge dissemination and transference (Shraah et al., 2022; Hu et al., 2019; Peng and Shao, 2021). To elucidate, both the infrastructural avenues facilitating knowledge sharing and individual’s intrinsic motivations critically influence knowledge exchange behaviors (Chuang et al., 2019). The multifaceted construct of knowledge sharing encompasses aspects of information interchange, archival, retrieval, and the codification of systematic organizational procedures (Hassan et al., 2016). As articulated by Lailin and Gang (2016), knowledge transfer transcends mere information relay and encapsulates the holistic process of selection, assimilation, integration, and application of knowledge (Zhao et al., 2021). It is therefore incumbent upon the knowledge management framework to engender conducive environments for knowledge disseminators, while concurrently proffering appropriate incentives (Harzing et al., 2016; Shraah et al., 2022). A conspicuous gap in empirical literature persists regarding the functionality, relevance, and potency of knowledge-sharing and transfer mechanisms, with a marked dearth of insights specific to the information service sector (Chuang et al., 2019). This investigation endeavors to elucidate the ramifications of the knowledge management paradigm on employee’s propensities towards knowledge sharing and transference (Hu et al., 2019).

Organizations institute knowledge management processes with the intent of enhancing the exchange and transfer of knowledge among employees (Zhao et al., 2021). However, existing literature suggests that a rigid management framework might engender feelings of exclusion among employees, possibly diminishing their propensity to disseminate information and prompting opportunistic tendencies (Hassan et al., 2016). Areed et al. (2021) posited that intra-organizational social dynamics influence the appraisal of an individual’s social capital. This, in turn, can facilitate knowledge transfer at an individualistic level, thereby augmenting organizational value. In this context, social capital is understood as the sum of actual and potential resources embedded within, available through, and derived from the network of relationships possessed by an individual or organization (Adler and Kwon, 2002; Bolino et al., 2002). It is broadly categorized into structural social capital, which refers to the impersonal configuration of linkages between individuals or units (Burt, 2000; Coleman, 1988), and relational social capital, which emphasizes the personal relationships developed through a history of interactions, characterized by trust, reciprocity, and mutual respect (Putnam, 1995; Nahapiet & Ghoshal, 1998). These dimensions of social capital facilitate cooperative behaviors and knowledge exchange, enhancing organizational and individual performance (Le and Lei, 2018; Reagans and McEvily, 2003). The knowledge management process shapes individuals’ perceptions regarding governance protocols and is demonstrably influenced by social capital (Al-Emran et al., 2018). Interpersonal affiliations can bolster both formal and informal communication channels among staff, thereby promoting resource and expertise exchange (Shraah et al., 2022). Recent empirical evidence from Bhatti et al. (2021) underscores the profound influence of social capital on members’ tendencies towards knowledge sharing. Furthermore, Swanson et al. (2020) asserted that social capital positively modulates information dissemination across structural, relational, and cognitive dimensions. Nevertheless, the nexus between social capital and the knowledge management process remains underexplored (Lailin and Gang, 2016). Consequently, this study contends that delving into the ramifications of social capital on the knowledge management process holds significant academic and practical implications (Harzing et al., 2016; Shraah et al., 2022).

Literature review

Social exchange theory

The social exchange theory offers an analytical framework to interpret behaviors manifesting in social transactions. The rewards derived from social exchanges, both intrinsic and extrinsic, are often nebulous and defy precise quantification (Blau, 1964). Consequently, the emphasis on social exchanges gravitates toward the cultivation of enduring relationships rather than transient transactions (Shariq et al., 2019; Bolino et al., 2002; Bourdieu, 1986). Within this paradigm, knowledge dissemination can be conceptualized as a variant of social exchange where participants engage in oblique transactions (Shariq et al., 2019; Al-Emran et al., 2018; Farooq, 2019). The individual proffering knowledge prioritizes relationship cultivation over immediate gains, with the knowledge management system serving as an intermediary bridge connecting knowledge donors and recipients (Kankanhalli et al., 2005; Foss et al., 2010; Hansen, 1999). Leveraging the social exchange theory can yield insights into the merits of the knowledge management process, thereby optimizing returns for employees and fostering a robust culture of knowledge exchange and transfer (Ganguly et al., 2019; Ghahtarani et al., 2020; Mohajan, 2019).

The knowledge management process can significantly enhance the efficacy of knowledge transfer within organizational frameworks, as articulated by Ye et al. (2021). “Knowledge transfer” is defined as the dissemination of expertise from one entity to another via experienced conduits, and it is instrumental in amplifying organizational performance (Hamdoun et al., 2018; Lombardi, 2019; Al-Emran et al., 2018). As delineated by Farooq (2019), knowledge transfer is inherently unidirectional, signified by the transmission of information from the donor to the recipient. This encompasses the donor’s act of proffering information and the recipient’s subsequent assimilation and application of said information (Hansen, 1999; Foss and Pedersen, 2019). Moreover, the process of knowledge transfer is punctuated by stages of translation and transformation, as expounded by Krylova et al. (2016). Through these stages, knowledge is rendered more comprehensible and actionable (Lombardi, 2019; Ferraris et al., 2020), underscoring the applicability of the transferred knowledge within the recipient’s domain and illustrating the continuity of information flow (Lilleoere and Holme, 2011). Within the realm of academia, knowledge governance should pivot on the methodologies employed by educators in disseminating their knowledge and the pivotal role of leadership in orchestrating knowledge governance (Fabiano et al., 2020; Foss et al., 2010).

Information dissemination is a critical facet of knowledge-oriented endeavors and is imperative for transmuting individualized knowledge into an organizational asset. This practice augments capabilities pertaining to innovation, knowledge synthesis, and generative knowledge, whilst facilitating integration and application at the organizational level (Foss and Pedersen, 2019; Ritala and Stefan, 2021; Farooq, 2019). Hansen (1999) postulates that knowledge dissemination encompasses the mutual exchange of expertise, acumen, insights, and advisories amongst team constituents. The propensity to support peers is intrinsically linked with knowledge-sharing behavior, and both extrinsic and intrinsic inducements exert a profound influence on the predisposition toward knowledge dissemination (Foss and Pedersen, 2019; Ganguly et al., 2019; Borges et al., 2019; Yong et al., 2020; Peng, 2022). Amplified motivation heightens members’ discernment of the merits inherent in knowledge contribution, thereby catalyzing the sharing dynamic. The volition for information exchange, coupled with the presence of conducive platforms, predicates the volume and quality of expertise disseminated (Foss and Pedersen, 2019; Ganguly et al., 2019; Zhao et al., 2021; Abbas et al., 2020). Lilleoere and Hansen (2011) assert that members’ perception of available dissemination avenues critically influences intra-organizational knowledge sharing. The attendant risks and overheads associated with sharing diminish when individuals can leverage platforms underpinned by their social affiliations, thus nurturing a pro-sharing disposition (Anwar et al., 2019; Bhatti et al., 2021). A predisposition to share is fortified when individuals perceive unencumbered access to sharing conduits (Gagné et al., 2019; Saleh and Bista, 2017).

Knowledge management process

The Knowledge Management Process (KMP) serves as an instrumental framework within the ambit of the knowledge-based economy. In an era characterized by rapid shifts in consumer expectations and relentless market competition, organizations are increasingly reliant on KMP for the procurement and operationalization of innovative knowledge (Ahmed et al., 2019; Xie et al., 2019). KMP is delineated as a structured endeavor aimed at either enhancing organizational performance or offering value-added services to the community through the strategic deployment of extant expertise (Zaim et al., 2019; Farooq, 2019). It acts as a foundational nexus for the acquisition, dissemination, and efficacious utilization of knowledge assets, which in turn catalyze organizational innovation (Migdadi, 2021; Al-Emran et al., 2018). Empirical studies underscore the pivotal role of KMP’s triadic components: knowledge acquisition (KA), knowledge dissemination (KD), and knowledge application (KAP), in augmenting the processes of information sharing and transfer (Qasrawi et al., 2017; Shahzad et al., 2020; Han et al., 2019). These components serve as the foundational mechanisms through which knowledge is managed within organizations. Specifically, KA involves the identification and absorption of new knowledge (Al-Emran et al., 2018); KD refers to the distribution of knowledge within the organization (Borges et al., 2019); and KAP pertains to the effective utilization of knowledge in decision-making and organizational practices (Farooq, 2019). To clarify, the impact of KMP extends beyond the mere facilitation of these components. The successful implementation of KMP leads to tangible outcomes, including enhanced organizational innovation (Ahmed et al., 2019), improved employee performance (Abbas et al., 2020), and increased competitive advantage (Zaim et al., 2019). Therefore, when it is stated that KMP fosters knowledge sharing, it implies that the systematic and structured approach to managing knowledge—encompassing acquisition, dissemination, and application—enables a culture and practice of sharing, which in turn contributes to these broader organizational outcomes. This delineation ensures that the discussion of KMP’s role in fostering knowledge sharing is not circular but indicative of its comprehensive impact on organizational knowledge dynamics. Engaging with stakeholders through this structured paradigm enables organizations to assimilate novel information and gain nuanced insights into consumer predilections within evolving market landscapes (Shahzad et al., 2020; Borges et al., 2019).

Furthermore, the assimilated knowledge is harnessed to enhance both the final products and internal processes of the enterprise (Migdadi, 2021; Farooq, 2019). Institutions that prioritize knowledge often motivate their personnel to actively engage in organizational activities, thereby offering pragmatic solutions (Abbas et al., 2020). Environmental specialists and behavioral scientists posit that the consumption of non-sustainable products significantly contributes to environmental degradation, manifested in pollution, deteriorated air quality, and climate perturbations (Li et al., 2019; Hamdoun et al., 2018). The social exchange theory postulates that organizations fortified with robust KMP and nimble competencies are better positioned to innovate and manufacture sustainable commodities, thereby mitigating adverse impacts on both society and the environment (Foss and Pedersen, 2019; Ganguly et al., 2019).

Research has underscored the advantages of KMP in facilitating knowledge exchange (Al-Emran et al., 2018; Olaisen & Revang, 2017; Shahzad et al., 2020). Han et al. (2019) contend that there exists a lacuna in understanding the influence of structured knowledge governance on knowledge dissemination. A recent investigation by Syed et al. (2021) assessed the ramifications of both structured and unstructured KMP on knowledge dissemination, revealing a dichotomy between organizational expectations and individual employee motivations (Migdadi, 2021). While enterprises anticipate that employees will disseminate knowledge for collective advantage, individuals often retain specialized knowledge to safeguard their personal vested interests and organizational stature (Farooq, 2019). Consequently, a socio-organizational paradox emerges between firms and their staff. Cao and Xiang (2012) posit that KMP is pivotal in augmenting knowledge dissemination, serving as a catalyst for collaborative knowledge sharing among personnel (Ali et al., 2018; Qi and Chau, 2018; Xie et al., 2019). Given these considerations, this study propounds the ensuing hypothesis:

H1: Knowledge management process has a positive impact on knowledge sharing behavior.

The efficacy of a knowledge management approach, as delineated by Syed et al. (2021), holds promise not merely for bolstering information dissemination but also for enhancing the cognitive capacities of employees, paving the way for sustained knowledge transmission (Migdadi, 2021). An integral knowledge management framework is quintessential for cultivating a sharing ethos, institutionalizing methodologies, and judicious resource allocation within enterprises (Shahzad et al., 2020). Cultivating a sharing ethos stimulates employees to disseminate their acquired insights with colleagues (Al-Emran et al., 2018). Standardizing methodologies, encompassing operational protocols, documentation architectures, and reward-sanction mechanisms, lays the groundwork for facilitating knowledge exchange among staff (Fabiano et al., 2020; Olaisen & Revang, 2017). In scenarios of constrained resources, prudent resource stewardship becomes pivotal to amplifying knowledge transmission efficiency (Xie et al., 2019). Concurrently, elements such as trust, socio-professional networks, and personal identification exert significant influence on knowledge propagation (Han et al., 2019; Zhao et al., 2021; Qi and Chau, 2018). Interpersonal network affiliations and trust modulate the extent of tacit knowledge dissemination, while personal identification gauges the intrinsic worth of knowledge (Ali et al., 2018). Given the intricacies inherent in knowledge transmission, the salience of knowledge governance in elevating the efficacy of knowledge asset dissemination is accentuated (Zaim et al., 2019). In light of these insights, this study advances the subsequent hypothesis:

H2: Knowledge management process has a positive impact on knowledge transfer behavior.

Social capital

While earlier research acknowledged the role of knowledge management in integrating various organizational processes, it often overlooked the critical influence of social connections (Syed et al., 2021). Recently, however, there has been a noticeable shift towards examining the social aspects of knowledge management, particularly the role of social capital among organizational members, as highlighted in the studies by Ghahtarani et al. (2020) and Pemsel et al. (2016). The exploration of social capital has evolved significantly, tracing back to the pioneering works of Coleman (1988) and Putnam (1995), while also acknowledging the contributions of Pierre Bourdieu (Han et al., 2019). Coleman (1988) introduced social capital within a broader sociological framework, emphasizing its role in enabling specific actions through leveraging norms, networks, and social trust within social structures. Putnam (1995) further elaborated on social capital, elucidating its capacity to strengthen communities and organizations through networks of civic engagement, trust, and reciprocity, thus underlining the vital contribution of social capital to societal betterment and organizational innovation (Akram et al., 2017; Peng, 2022).

Simultaneously, Bourdieu’s examination offers a comprehensive perspective on social capital as the accumulation of real or potential resources stemming from one’s network, characterized by various degrees of institutionalized relationships, mutual familiarity, and recognition. His insights underscore the importance of networking and its benefits within a sociological context (Zhao et al., 2021). Social capital, as articulated by these scholars, comprises both hidden and overt resources that are accessible through networks of affiliation. According to Ganguly et al. (2019), Edinger & Edinger (2018), and as reinforced by Qi and Chau (2018), social capital within a team or organization facilitates the achievement of collective goals through enhanced cooperation and trust. Teams or collectives that effectively leverage their social capital, described by Al-Emran et al. (2018) as possessing a more readily mobilizable form, demonstrate greater efficiency in accessing, sharing knowledge, and mutual support, thus significantly elevating organizational performance.

Therefore, assessing a team’s social capital necessitates a comprehensive understanding of its broader organizational context, focusing on how social structures, networks, and the nature of interpersonal relationships contribute to achieving organizational goals (Coleman, 1988; Putnam, 1995; Alghababsheh & Gallear, 2020). Research efforts, as noted by Ganguly et al. (2019), Lucas et al. (2018), and Pinho & Prange (2016), commonly employ both relational and structural measures to quantify social capital. The relational dimension of social capital refers to the quality of personal relationships that exist within networks, characterized by trust, mutual respect, and an obligation to reciprocate, which facilitate cooperative behaviors and information sharing among individuals (Akram et al., 2017; Chen et al., 2020; Zhou et al., 2021). This dimension emphasizes the importance of strong, trust-based relationships in enabling effective communication and collaboration (Zhou et al., 2022). Conversely, the structural dimension of social capital pertains to the overall configuration of connections within a network, including the density and connectivity of social ties that enable individuals to access resources and information (Akram et al., 2017; Chen et al., 2020; Zhou et al., 2021). This dimension focuses on how the structure of networks, rather than the quality of individual relationships, facilitates or impedes the flow of information and resources across an organization. This study posits that an encompassing assessment that incorporates both relational and structural dimensions is crucial to fully appreciate the extensive benefits that social capital brings to information and knowledge management (Shahzad et al., 2020). Recent studies further underscore this point, showing that the interplay between relational and structural dimensions of social capital significantly impacts organizational innovation and performance (Reagans and McEvily, 2003; Hu and Randel, 2014). Solely focusing on one dimension might obscure the depth of insights and information employees derive from their social networks (Olaisen & Revang, 2017). This integrated perspective combines the foundational theories of social capital with current research, highlighting its pivotal role in enhancing knowledge management within organizations.

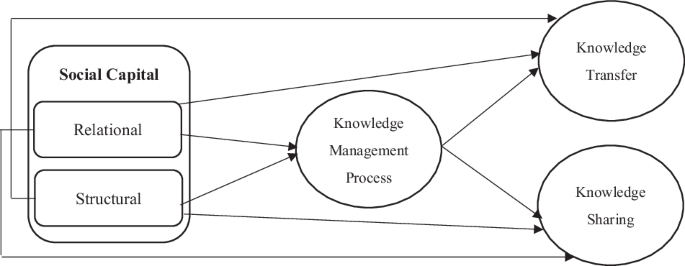

The construct of social capital encapsulates the inherent attributes of mutualistic network relationships, exerting influence not solely on knowledge dissemination but also bolstering the aptitude of employees to assimilate and deploy novel insights (Syed et al., 2021). Fundamental social dynamics, epitomized by intra-organizational cohesion and trust, stand as linchpins in sculpting a vibrant social network (Han et al., 2019). Such a network serves as a conduit for the seamless transition of organizational assets, acumen, and proficiencies (Danilov and Mihailova, 2021; Ahmed et al., 2019). The intricacies of social processes are instrumental in the genesis and operationalization of knowledge, underscoring the indispensable nature of social capital (Ghahtarani et al., 2020; Pemsel et al., 2016). In light of these considerations, this study delineates the ensuing hypotheses:

H3a: Relational social capital has a positive impact on knowledge management process.

H3b: Structural social capital has a positive impact on knowledge management process.

Prior empirical investigations, as highlighted by Swanson et al. (2020) and Rezaei et al. (2020), have meticulously probed the nexus between structural social capital and knowledge management. Their collective inference suggests that knowledge management acts as a catalyst for enhancing structural social capital (Liu & Meyer, 2020). Structural social capital inherently mirrors the intensity and regularity of affiliations among colleagues (Sheng & Hartmann, 2019). An amplified frequency of engagements, underpinned by social capital, bestows upon employees augmented avenues to disseminate explicit data and assimilate tacit wisdom (Foss and Pedersen, 2019). Such dynamics inevitably bolster the propensity to disseminate information, magnifying its periodicity, depth, and breadth within the confines of social exchanges (Khan and Khan, 2019). Bolino et al. (2002) accentuated that reciprocal trust stands as the cornerstone in the edifice of social capital connections. The magnitude of mutual trust and collaboration epitomizes the essence of social capital affiliations (Ganguly et al., 2019; Le and Lei, 2018). An elevated echelon of trust within the workforce invariably catalyzes a heightened inclination to unveil tacit insights and privileged intelligence (Ferraris et al., 2020). Intimate synergies among employees expedite the conveyance of tacit understanding, whereas the prevailing norms, trust, and collaboration within the social capital framework magnify the prospects for personnel to reciprocate and promulgate explicit knowledge (Gubbins and Dooley, 2021). Given these precepts, the subsequent hypothesis is posited:

H4a: Relational social capital has a positive impact on knowledge sharing behavior.

H4b: Structural social capital has a positive impact on knowledge sharing behavior.

H5a: Relational social capital has a positive impact on knowledge transfer behavior.

H5b: Structural social capital has a positive impact on knowledge transfer behavior.

According to the above hypotheses, the research framework is shown in Fig. 1:

Methodology

Sampling

This study aims to explore knowledge management practices within the research and development (R&D) sector of the information service industry, with a keen focus on companies operating within the People’s Republic of China. Recognizing the importance of ethical research practices, particularly in safeguarding the confidentiality of participants’ identities during the survey process, this study employs a purposive sampling method. This approach facilitates a targeted examination of specific characteristics within a select population group, ensuring that the identity of respondents is meticulously protected from any potential threats or breaches of confidentiality. The research was conducted among companies characterized by a unique amalgamation of state-driven and market-driven economic practices, a hallmark of the Chinese business environment. This environment, distinct from traditional capitalist market economies due to significant state intervention, impacts various management processes and practices. The companies surveyed span multiple sectors—manufacturing, technology, and services—and are situated in major economic hubs such as Shanghai, Shenzhen, and Guangzhou. Engaging with companies that, despite being rooted in a Chinese context, often participate in global markets, provides a relevant and rich field for examining knowledge management practices. In conducting this study, special emphasis was placed on research ethics to protect the identities of participants and prevent any inadvertent threats. The unique blend of influences in the Chinese context—ranging from state policies and cultural nuances to the historical evolution of the Chinese economic system—contributes significantly to the shaping of management processes. This backdrop allows for an intriguing exploration of knowledge management practices in an environment that diverges from the purely capitalist model, underpinned by a strong commitment to maintaining the highest standards of confidentiality and ethical rigor in the research process.

The study population was comprised of R&D workers from high-tech companies, excluding administrative personnel, to ensure a representative sample. Before commencing the sampling process, all research procedures, including the methods of data collection and analysis, were reviewed and approved. This was to ensure that the study adhered to the highest ethical standards and that the rights and privacy of participants were protected. All participants were informed about the purpose of the study, and their informed consent was obtained. They were also assured of the confidentiality of their responses and were informed that they could withdraw from the study at any time without any repercussions. The study utilized an electronic questionnaire to gather data from the participants. Out of 490 individuals approached, we received 483 valid responses after removing 7 invalid ones, yielding a response rate of approximately 98.6%. Such a high response rate is in line with Saleh and Bista’s (2017) emphasis on the importance of response rates in determining the reliability and validity of survey findings. The results showed that the majority of the participants were male (63.1%), highly educated with a master’s degree or above (61.4%), and between the ages of 30 and 40 years old (72.1%). The average work experience of the participants was 5.2 years. These demographic characteristics provide a clear picture of the study participants and offer important insights into the impact of identity threats on information-sharing behaviors among R&D workers in the information service industry.

Measures

The study employed a bespoke questionnaire to evaluate various factors within the realm of industrial practice. A five-point Likert scale was used to gauge the magnitude of each factor, where 1 signifies “strongly disagree” and 5 represents “strongly agree.” The instrument for assessing social capital was informed by the model proposed by Tsai et al. (2014) and underwent modifications building on scales developed by Lin and Huang (2010), Yilmaz and Hunt (2001), and Croteau and Raymond (2004). This questionnaire encompasses seven items probing both relational and structural dimensions of social capital, with the verbiage tailored to the industrial milieu.

The knowledge management process is gauged using a questionnaire grounded in the scales formulated by Shahzad et al. (2020) and refined by Migdadi (2021) to suit the information service industrial setting. The tripartite components of the knowledge management process—knowledge acquisition, knowledge dissemination, and knowledge application—are delineated into 6, 5, and 5 items correspondingly. The metric for assessing knowledge-sharing is derived from Al-Emran et al. (2018), encompassing 11 items that scrutinize three facets of knowledge-sharing practices: motivation, opportunities, and behavior.

The knowledge transfer scale is adapted from Reagans and McEvily (2003), and the five questions in the questionnaire evaluate employees’ knowledge transfer situations. The terminology is altered to fit the context, and the questions aim to assess the ease of transferring knowledge and information. The scale of constructs is shown in Table 1.

Analysis strategy

In this study, we employed Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) as our primary analytical tool. SEM was chosen due to its capability to assess complex relationships between observed and latent variables, allowing for a comprehensive understanding of the underlying constructs in our research model. SEM is particularly beneficial for research like ours, where multiple relationships are hypothesized simultaneously, and it provides a more nuanced understanding of the direct and indirect effects between variables (Dash and Paul, 2021; Savalei, 2020). Moreover, SEM’s flexibility in handling both measurement and structural models makes it an apt choice for our study, ensuring robustness in our findings (Hallgren et al., 2019).

Results

Measurement

In line with the recommendations of Hair et al. (2017), our first step was to evaluate the measurement model. This involved assessing the reliability and validity of the constructs used in the study. The validity of the postulated factor structure was appraised using confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). Adhering to the two-step CFA approach recommended by Anderson and Gerbing (1988), the construct validity of the model was ascertained. Initially, individual item reliability was evaluated by analyzing the direct loadings or correlations between the measures (or indicators) and their pertinent constructs. It was deemed imperative to verify that the factor loadings of these indicators surpassed 0.7, denoting a robust linkage (Hair et al., 2014). Subsequently, the model’s reliability was affirmed by scrutinizing Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability (CR) metrics, both of which exceeded the benchmark value of 0.7 as posited by Hair et al. (2017). In the third step, the average variance extracted (AVE) metrics were observed to exceed the threshold of 0.50 (Hair et al., 2017), indicating satisfactory convergent validity, as shown in Table 2.

Discriminant validity is a crucial aspect of construct validity, ensuring that a construct is distinctly different from other constructs within the model (Hair et al., 2016). In essence, it assesses the extent to which a construct is truly unique and not just a reflection of other constructs in the model. For our study, discriminant validity was tested to ensure that the measures of our constructs were not highly correlated with measures of other constructs, thereby confirming that each construct captures a unique phenomenon. In Table 3, the results for discriminant validity are presented. The diagonal values represent the square root of the average variance extracted (AVE) for each construct, while the off-diagonal values are the correlations between constructs. For adequate discriminant validity, the diagonal values (square root of AVE) should be greater than the off-diagonal values in the corresponding rows and columns (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). As can be observed in Table 3, our model meets this criterion, indicating satisfactory discriminant validity. It’s worth noting that discriminant validity is not just a statistical requirement but also a theoretical one. Ensuring distinct constructs allows for clearer interpretations of the relationships among constructs and enhances the robustness of the theoretical framework (Henseler et al., 2015).

Hypothesis testing

In this study, the structural model was assessed utilizing SmartPLS 3.0, with the linkages and foundational assumptions of the conceptual framework validated via PLS-SEM. Subsequent to the evaluation of the measurement model, we advanced to the structural model examination, adhering to the guidelines proposed by Hair et al. (2017). This phase entailed scrutinizing the interrelations among the constructs and appraising the posited hypotheses. When deploying PLS-SEM, it is imperative to assess both the model’s quality and the variances of the dependent variables, with pertinent metrics encompassing SRMR, NFI, Q2, and R2. Prior to delving into hypothesis testing, collinearity’s potential influence must be ascertained within the structural model. This entails examining whether variance inflation factors (VIFs) exceed the conventional threshold of 3. The results elucidate that collinearity is not a concern in this study, given that all VIF metrics fall below 3. Additionally, a bootstrapping method with 5000 subsamples was employed for the structural models in this investigation.

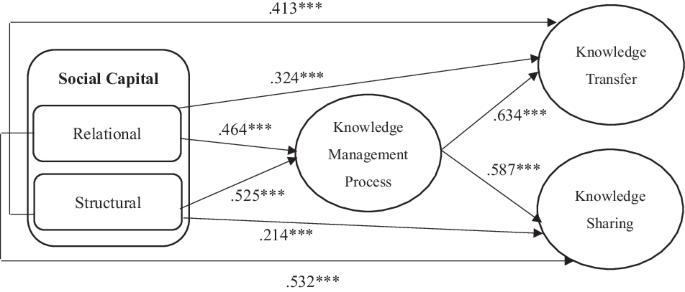

The findings of this investigation are shown in Fig. 2 and Table 4. Regarding H1 and H2, the findings show that the knowledge management process has a favorable and substantial impact on workers’ knowledge-sharing and transfer behaviors (β = 0.634, p = 0.000) and (β = 0.587, p = 0.000). H1 and H2 are thus supported. Additionally, the findings indicate that structural social capital (β = 0.525, p = 0.000) and relational social capital (β = 0.464, p = 0.000) both have a favorable and substantial impact on the knowledge management process, supporting H3a and H3b. H4a and H4b are verified because relational social capital (β = 0.532, p = 0.000) and structural social capital (β = 0.214, p = 0.000) have a favorable effect on workers’ knowledge-sharing behavior. Additionally, H5a and H5b are supported by our results, which show that relational social capital (β = 0.324, p = 0.000) and structural social capital (β = 0.413, p = 0.000) positively influence workers’ knowledge transfer behavior.

Conclusions

Discussion

The findings from this investigation underscore that KMP, defined as the systematic approach to acquiring, disseminating, and effectively using knowledge within organizations, exerts a positive influence on the dissemination and sharing of knowledge among staff members (Foss and Pedersen, 2019; McFadyen and Cannella Jr, 2004). This observation is consonant with perspectives delineated by Abbas et al. (2020), Olaisen and Revang (2017), and Areed et al. (2021). Furthermore, it is posited that an exhaustive knowledge management regimen—encompassing the key components of knowledge acquisition, dissemination, and application—significantly enhances the flow of information by fostering an environment that encourages employees to engage in knowledge transfer activities. This is largely due to the synergistic effect these components have when effectively integrated within an organization’s practices (Zaim et al., 2019; Al-Emran et al., 2018). Specifically, by establishing a methodical and formalized framework for KMP, organizations can significantly optimize the efficacy of knowledge exchange and transmission across individuals and entities (Ferraris et al., 2020; Han et al., 2019). This approach not only streamlines the process of sharing critical information but also ensures that knowledge is accurately and efficiently circulated among employees, thereby facilitating improved decision-making and innovation (Farooq, 2019; Borges et al., 2019). The organizational socialization paradigm, as expounded by Ali et al. (2018), Qi and Chau (2018), and Han et al. (2019), modulates the employees’ inclination toward fortifying knowledge dissemination and sharing. A strong organizational affiliation and a cohesive group identity serve to enhance interpersonal communication and collaboration among staff, creating a fertile ground for the effective implementation of KMP (Ahmed et al., 2019; Bhatti et al., 2021). Consequently, the leadership’s strategic approach to knowledge management plays a crucial role in shaping the dynamics of knowledge-sharing and transfer among employees, highlighting KMP’s significant contribution to promoting a culture of open information exchange and continuous improvement (Anwar et al., 2019; Hamdoun et al., 2018; Adler and Kwon, 2002; Bolino et al., 2002).

This study ascertains that, when enriched with substantial structural and relational social capital, employees exhibit an increased propensity to engage in knowledge-sharing and transfer endeavors. In this context, social capital is defined by the structural dimension, which refers to the objective and quantifiable connections among individuals or groups, such as network ties and configurations, and the relational dimension, which pertains to the subjective and qualitative aspects of relationships, such as trust, norms, and obligations (Putnam, 1995; Chen et al., 2020; Zhou et al., 2021; Adler and Kwon, 2002; Borges et al., 2019). The findings underscore that both structural and relational dimensions of social capital bolster the knowledge management procedure, consequently amplifying knowledge transfer and sharing proclivities (Ganguly et al., 2019; Ferraris et al., 2020). Accordingly, the structural dimension of social capital contributes to knowledge exchange by providing a framework of connections through which information can flow, while the relational dimension enhances the quality and effectiveness of these exchanges through interpersonal rapport and mutual understanding (Adler and Kwon, 2002; Borges et al., 2019; Chen et al., 2020; Zhou et al., 2021). An elevated reservoir of social capital, as articulated by Han et al. (2019), Zhao et al. (2021), and Bhatti et al. (2021), galvanizes employee participation in knowledge management undertakings and augments knowledge-centric collaborations. Moreover, components of social capital such as trust and shared language, which facilitate mutual understanding, are identified as critical factors that yield better results in information exchange (Coleman, 1988; McFadyen and Cannella Jr, 2004; Peng et al., 2021). Intimate social affiliations, coupled with a multifaceted social network matrix, incentivize employees to assimilate more nuanced and invaluable insights (Borges et al., 2019; Hu and Randel, 2014). These insights lead to deeper comprehension and utilization of knowledge within the organization, as individuals feel more confident and committed to sharing information in a trustworthy environment (McFadyen and Cannella Jr, 2004; Hau et al., 2013). Consequently, this equips them with an enhanced eagerness to acquire, disseminate, and implement knowledge, thereby refining their capabilities in knowledge innovation (Foss and Pedersen, 2019; Gubbins and Dooley, 2021).

The findings of this study corroborate the theoretical perspectives delineated by Alghababsheh and Gallear (2020), Edinger and Edinger (2018), and Ganguly et al. (2019). These theories underscore that an employee’s social capital acts as a pivotal conduit for external knowledge acquisition and as a barometer for interpersonal dynamics (Bolino et al., 2002; Bourdieu, 1986). The concept of ‘bridging’ and ‘bonding’ social capital further refines this understanding by distinguishing between the types of network connections that facilitate the flow of new information (bridging) and those that strengthen existing relationships (bonding), respectively (Putnam, 1995; Adler and Kwon, 2002). Enhanced social capital can fortify the nexus between employees and their organization, thereby smoothing the channels for information dissemination (Ahmed et al., 2019; Han et al., 2019). This fortification of relationships within the organization creates a conducive environment for the free flow of innovative ideas and critical information, integral to the adaptive and competitive capabilities of firms (Peng et al., 2021; Zhou et al., 2021). As evidenced by Crompton et al. (2020) and supported by Zhao et al. (2021), social interactions wield a positive influence on the magnitude of information exchanged. Through the creation of virtual social collectives—platforms where insights, expertise, and experiences are pooled—employees can foster mutual connections, thereby facilitating knowledge assimilation and dissemination amongst themselves (Gubbins and Dooley, 2021; Reagans and McEvily, 2003).

Implications

The findings of this study illuminate that employees’ perception of the institutionalization of knowledge management augments information-sharing behaviors, especially in the context of the economic repercussions stemming from the COVID-19 pandemic (Abbas et al., 2020; Olaisen & Revang, 2017). There is a discernible positive association between the employment of a social capital-centric knowledge management strategy and the knowledge transfer and sharing behaviors of employees (Han et al., 2019; Zhao et al., 2021). Primarily, the knowledge management strategy notably bolsters employees’ proclivities towards knowledge dissemination and transfer (Alghababsheh & Gallear, 2020; Edinger & Edinger, 2018; Ganguly et al., 2019). For organizations aspiring to stimulate knowledge-sharing behaviors among their workforce and elevate the efficacy of intra-organizational knowledge circulation, championing a comprehensive and structured knowledge management initiative is paramount (Ali et al., 2018; Qi and Chau, 2018). By harnessing interactive knowledge management infrastructures, organizations can stimulate knowledge creation endeavors, steward knowledge transfer and sharing both intrinsically and extrinsically, and solidify synergies between macro and micro organizational tiers (Crompton et al., 2020). This not only augments employees’ knowledge-sharing and transfer behaviors but also nurtures a culture imbued with sharing ethos. Moreover, it anchors a robust knowledge management framework, judiciously allocates resources and precipitates favorable organizational outcomes.

The augmentation of employees’ human capital is intrinsically linked to their knowledge acquisition. Furthermore, it is their inherent social capital that catalyzes knowledge dissemination and sharing behaviors (Foss and Pedersen, 2019). Effective management of social capital within the workforce empowers organizations to foster their human capital, which subsequently reciprocates by amplifying their social capital (Sheng & Hartmann, 2019). Consequently, employees endowed with elevated social capital are more predisposed to engage in regular interpersonal exchanges, cultivating a more conducive work environment (Ghahtarani et al., 2020). This dynamic facilitates rapid access to and sharing of both explicit and tacit knowledge, streamlining organizational information flow and optimizing the efficacy of knowledge transfer processes (Mohajan, 2019).

Limitations

Despite its insights, this study is not without limitations. Firstly, this study primarily investigates the knowledge management process through the lens of social interaction (Ganguly et al., 2019; Le and Lei, 2018). While this perspective offers valuable insights, theoretical models encompassing a broader spectrum, such as embeddedness theory (Crompton et al., 2020) and absorptive capacity (Abbas et al., 2020), exist and can enrich our understanding when aligned with diverse theoretical orientations. To further enrich the conceptual depth of knowledge management theories, it is posited that scholars develop management frameworks that more effectively promote employees’ knowledge dissemination and transfer practices (Olaisen & Revang, 2017).

Historically, social capital has been identified as a pivotal precursor in discussions centered on its influence on knowledge transfer and sharing behaviors (Foss and Pedersen, 2019; Sheng & Hartmann, 2019). However, contemporary research positions social capital as a salient mediating variable, asserting that robust social capital can amplify the effectiveness of knowledge management strategies (Han et al., 2019; Zhao et al., 2021). Consequently, future inquiries should delve into the intermediary role of social capital to furnish a more nuanced understanding (Ghahtarani et al., 2020).

Lastly, this study did not undertake a comparative analysis of high-tech employees across different countries (Ali et al., 2018; Qi and Chau, 2018). Given the intricate tapestry of societal and cultural nuances, discernible disparities might exist in employees’ information-sharing tendencies across national boundaries (Borges et al., 2019). Therefore, it is prudent for subsequent research to evaluate the mediating effects of regional characteristics on employees’ knowledge-sharing proclivities (Valk and Planojevic, 2021).

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. The data comprises questionnaire survey responses, which were collected and curated specifically for this research. Due to the nature of the data, it cannot be directly deposited in a public repository, but the corresponding author is willing to share the anonymized dataset with interested researchers upon request.

References

Abbas J, Zhang Q, Hussain I, Akram S, Afaq A, Shad MA (2020) Sustainable innovation in small medium enterprises: the impact of knowledge management on organizational innovation through a mediation analysis by using SEM approach. Sustainability 12(6):2407

Adler PS, Kwon SW (2002) Social capital: prospects for a new concept. Acad Manag Rev 27(1):17–40

Ahmed YA, Ahmad MN, Ahmad N, Zakaria NH (2019) Social media for knowledge-sharing: a systematic literature review. Telemat Inform 37:72–112

Akram T, Lei S, Haider MJ, Akram MW (2017) What impact do structural, relational and cognitive organisational social capital have on employee innovative work behaviour? A study from China. Int J Innov Manag 21(02):1750012

Albort-Morant G, Leal-Rodríguez AL, De Marchi V (2018) Absorptive capacity and relationship learning mechanisms as complementary drivers of green innovation performance. J Knowl Manag 22(2):432–452

Al-Emran M, Mezhuyev V, Kamaludin A, Shaalan K (2018) The impact of knowledge management processes on information systems: a systematic review. Int J Inf Manag 43:173–187

Alghababsheh M, Gallear D (2020) Social capital in buyer-supplier relationships: A review of antecedents, benefits, risks, and boundary conditions. Ind Mark Manag 91:338–361

Ali I, Musawir AU, Ali M (2018) Impact of knowledge sharing and absorptive capacity on project performance: the moderating role of social processes. J Knowl Manag 22(2):453–477

Anderson JC, Gerbing DW (1988) Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol Bull 103(3):411

Anwar R, Rehman M, Wang KS, Hashmani MA (2019) Systematic literature review of knowledge sharing barriers and facilitators in global software development organizations using concept maps. IEEE Access 7:24231–24247

Areed S, Salloum SA, Shaalan K (2021) The role of knowledge management processes for enhancing and supporting innovative organizations: a systematic review. In: Al-Emran M, Shaalan K, Hassanien A (eds) Recent Advances in Intelligent Systems and Smart Applications. Studies in Systems, Decision and Control, Vol. 295. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-47411-9_8

Bearman P (1997) Generalized exchange. Am J Sociol 102(5):1383–1415

Bhatti SH, Vorobyev D, Zakariya R, Christofi M (2021) Social capital, knowledge sharing, work meaningfulness and creativity: evidence from the Pakistani pharmaceutical industry. J Intellect Cap 22(2):243–259

Blau PM (1964) Justice in social exchange. Sociol Inq 34(2)

Bolino MC, Turnley WH, Bloodgood JM (2002) Citizenship behavior and the creation of social capital in organizations. Acad Manag Rev 27(4):505–522

Borges R, Bernardi M, Petrin R (2019) Cross-country findings on tacit knowledge sharing: evidence from the Brazilian and Indonesian IT workers. J Knowl Manag 23(4):742–762

Bourdieu P (1986) The forms of capital. In: Richardson J (Ed.) Handbook of theory and research for the sociology of education. Greenwood, New York, pp. 241–258

Burt RS (2000) The network structure of social capital. Res Organ Behav 22:345–423

Cao C, Peng MYP, Xu Y (2022) How determinants of employee innovation behavior matter during the COVID-19 pandemic: investigating cross-regional role via multi-group partial least squares structural equation modeling analysis. Front Psychol 13:739898

Cao Y, Xiang Y (2012) The impact of knowledge governance on knowledge sharing. Manag Decis 50(4):591–610

Chen Z, Peng MYP (2020) Impact of organizational support and social capital on university faculties’ working performance. Front Psychol 11:571559

Chen Z, Chen D, Peng MYP, Li Q, Shi Y, Li J (2020) Impact of organizational support and social capital on university faculties’ working performance. Front Psychol 11:571559

Chuang FH, Weng HC, Hsieh PN (2019) A qualitative study of barriers to innovation in academic libraries in Taiwan. Libr Manag 40(6/7):402–415

Coleman JS (1988) Social capital in the creation of human capital. Am J Sociol 94:S95–S120

Crompton CJ, Ropar D, Evans-Williams CV, Flynn EG, Fletcher-Watson S (2020) Autistic peer-to-peer information transfer is highly effective. Autism 24(7):1704–1712

Croteau AM, Raymond L (2004) Performance outcomes of strategic and IT competencies Alignment1. J Inf Technol 19(3):178–190

Danilov IV, Mihailova S (2021) Knowledge sharing in social interaction: towards the problem of primary data entry. In: 11th Eurasian Conference on Language & Social Sciences, Gjakova (virtual), Kosovo

Dash G, Paul J (2021) CB-SEM vs PLS-SEM methods for research in social sciences and technology forecasting. Technol Forecast Soc Change 173:121092

Denieffe S (2020) Commentary: purposive sampling: complex or simple? Research case examples. J Res Nurs 25:662–663

Edinger SK, Edinger MJ (2018) Improving teacher job satisfaction: The roles of social capital, teacher efficacy, and support. J Psychol 152(8):573–593

Fabiano G, Marcellusi A, Favato G (2020) Channels and processes of knowledge transfer: How does knowledge move between university and industry? Sci Public Policy 47(2):256–270

Fang SC, Yang CW, Hsu WY (2013) Inter-organizational knowledge transfer: the perspective of knowledge governance. J Knowl Manag 17(6):943–957

Farooq R (2019) Developing a conceptual framework of knowledge management. Int J Innov Sci 11(1):139–160

Ferraris A, Santoro G, Scuotto V (2020) Dual relational embeddedness and knowledge transfer in European multinational corporations and subsidiaries. J Knowl Manag 24(3):519–533

Fornell C, Larcker DF (1981) Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J Mark Res 18(1):39–50

Foss NJ, Pedersen T (2019) Microfoundations in international management research: the case of knowledge sharing in multinational corporations. J Int Bus Stud 50(9):1594–1621

Foss NJ, Husted K, Michailova S (2010) Governing knowledge sharing in organizations: levels of analysis, governance mechanisms, and research directions. J Manag Stud 47(3):455–482

Gagné M, Tian AW, Soo C, Zhang B, Ho KSB, Hosszu K (2019) Different motivations for knowledge sharing and hiding: the role of motivating work design. J Organ Behav 40(7):783–799

Ganguly A, Talukdar A, Chatterjee D (2019) Evaluating the role of social capital, tacit knowledge sharing, knowledge quality and reciprocity in determining innovation capability of an organization. J Knowl Manag 23(6):1105–1135

Ghahtarani A, Sheikhmohammady M, Rostami M (2020) The impact of social capital and social interaction on customers’ purchase intention, considering knowledge sharing in social commerce context. J Innov Knowl 5(3):191–199

Gubbins C, Dooley L (2021) Delineating the tacit knowledge‐seeking phase of knowledge sharing: the influence of relational social capital components. Hum Resour Dev Q 32(3):319–348

Hair JF, Black WC, Babin BJ, Anderson RE (2016) Multivariate data analysis (7th edn.). Cengage

Hair Jr J, Hair Jr JF, Hult GTM, Ringle CM, Sarstedt, M (2017) A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). Sage publications

Hair Jr JF, Sarstedt M, Hopkins LG, Kuppelwieser V (2014) Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) An emerging tool in business research. Eur Bus Rev 26(2):106–121

Hallgren KA, McCabe CJ, King K, Atkins DC (2019) Beyond path diagrams: Enhancing applied structural equation modeling research through data visualization. Addict Behav. 94:74–82

Hamdoun M, Jabbour CJC, Othman HB (2018) Knowledge transfer and organizational innovation: Impacts of quality and environmental management. J Clean Prod 193:759–770

Han SH, Yoon DY, Suh B, Li B, Chae C (2019) Organizational support on knowledge sharing: a moderated mediation model of job characteristics and organizational citizenship behavior. J Knowl Manag 23(4):687–704

Hansen MT (1999) The search-transfer problem: the role of weak ties in sharing knowledge across organization subunits. Adm Sci Q 44(1):82–111

Harzing AW, Pudelko M, Sebastian Reiche B (2016) The bridging role of expatriates and inpatriates in knowledge transfer in multinational corporations. Hum Resour Manag 55(4):679–695

Hassan M, Aksel I, Nawaz MS, Shaukat S (2016) Knowledge sharing behavior of business teachers of Pakistani universities: an empirical testing of theory of planned behavior. Eur Sci J 12(13):29–40

Hau YS, Kim B, Lee H, Kim YG (2013) The effects of individual motivations and social capital on employees’ tacit and explicit knowledge sharing intentions. Int J Inf Manag 33(2):356–366

Henseler J, Ringle CM, Sarstedt M (2015) A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J Acad Mark Sci 43(1):115–135

Hu L, Randel AE (2014) Knowledge sharing in teams: social capital, extrinsic incentives, and team innovation. Group Organ Manag 39(2):213–243

Hu YF, Hou JL, Chien CF (2019) A UNISON framework for knowledge management of university–industry collaboration and an illustration. Comput Ind Eng 129:31–43

Islam T, Ahmad S, Kaleem A, Mahmood K (2020) Abusive supervision and knowledge sharing: moderating roles of Islamic work ethic and learning goal orientation. Management Decision

Janowicz-Panjaitan M, Noorderhaven NG (2009) Trust, calculation, and interorganizational learning of tacit knowledge: an organizational roles perspective. Organ Stud 30(10):1021–1044

Kankanhalli A, Tan BC, Wei KK (2005) Contributing knowledge to electronic knowledge repositories: An empirical investigation. MIS Quarterly 113–143

Khan NA, Khan AN (2019) What followers are saying about transformational leaders fostering employee innovation via organisational learning, knowledge sharing and social media use in public organisations? Gov Inf Q 36(4):101391

Krylova KO, Vera D, Crossan M (2016) Knowledge transfer in knowledge-intensive organizations: the crucial role of improvisation in transferring and protecting knowledge. J Knowl Manag 20(5):1045–1064

Lailin H, Gang Y (2016) An empirical study of teacher knowledge transfer based on e-learning. Mod Distance Educ Res 4:80–90

Le PB, Lei H (2018) The mediating role of trust in stimulating the relationship between transformational leadership and knowledge sharing processes. J Knowl Manag 22(3):521–537

Lee TC, Yao-Ping Peng M, Wang L, Hung HK (2021) Factors influencing employees’ subjective wellbeing and job performance during the COVID-19 global pandemic: the perspective of social cognitive career theory. Front Psychol 12:577028

Lilleoere AM, Holme Hansen E (2011) Knowledge‐sharing enablers and barriers in pharmaceutical research and development. J Knowl Manag 15(1):53–70

Lilleoere AM, Hansen EH (2011) Knowledge‐sharing practices in pharmaceutical research and development—A case study. Knowl Process Manag 18(3):121–132

Lin K, Peng MYP, Anser MK, Yousaf Z, Sharif A (2021) Bright harmony of environmental management initiatives for achieving corporate social responsibility authenticity and legitimacy: glimpse of hotel and tourism industry. Corp Soc Responsib Environ Manag 28(2):640–647

Lin TC, Huang CC (2010) Withholding effort in knowledge contribution: The role of social exchange and social cognitive on project teams. Inf Manag 47(3):188–196

Liu Y, Meyer KE (2020) Boundary spanners, HRM practices, and reverse knowledge transfer: The case of Chinese cross-border acquisitions. J World Bus 55(2):100958

Lombardi R (2019) Knowledge transfer and organizational performance and business process: past, present and future researches. Bus Process Manag J 25(1):2–9

Lucas K, Philips I, Mulley C, Ma L (2018) Is transport poverty socially or environmentally driven? Comparing the travel behaviours of two low-income populations living in central and peripheral locations in the same city. Transportation Res Part A: Policy Pract 116:622–634

McFadyen MA, Cannella Jr AA (2004) Social capital and knowledge creation: diminishing returns of the number and strength of exchange relationships. Acad Manag J 47(5):735–746

Migdadi MM (2021) Knowledge management, customer relationship management and innovation capabilities. J Bus Ind Mark 36(1):111–124

Mohajan HK (2019) Knowledge sharing among employees in organizations. J Econ Dev Environ People 8(1):52–61

Mothe C, Nguyen-Thi UT, Triguero Á (2018) Innovative products and services with environmental benefits: design of search strategies for external knowledge and absorptive capacity. J Environ Plan Manag 61(11):1934–1954

Moysidou K, Hausberg JP (2020) In crowdfunding we trust: a trust-building model in lending crowdfunding. J Small Bus Manag 58(3):511–543

Nahapiet J, Ghoshal S (1998) Social capital, intellectual capital, and the organizational advantage. Acad Manag Rev 23(2):242–266

Olaisen J, Revang O (2017) Working smarter and greener: Collaborative knowledge sharing in virtual global project teams. Int J Inf Manag 37(1):1441–1448

Pemsel S, Müller R, Söderlund J (2016) Knowledge governance strategies in project-based organizations. Long Range Plan 49(6):648–660

Peng MYP (2022) Future time orientation and learning engagement through the lens of self-determination theory for freshman: evidence from cross-lagged analysis. Front Psychol 12:760212

Peng MYP (2022) The roles of dual networks and ties on absorptive capacity in SMEs: the complementary perspective. Total Qual Manag Bus Excell 33(5-6):566–589

Peng MYP, Shao L (2021) How do the determinants of new product development matter in the international context? The moderating role of learning orientation. J Competitiveness 13(3):129

Peng MYP, Feng Y, Zhao X, Chong W (2021) Use of knowledge transfer theory to improve learning outcomes of cognitive and non-cognitive skills of university students: evidence from Taiwan. Front Psychol 12:583722

Peng MYP, Xu C, Zheng R, He Y (2023) The impact of perceived organizational support on employees’ knowledge transfer and innovative behavior: comparisons between Taiwan and mainland China. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 10(1):1–13

Pinho JC, Prange C (2016) The effect of social networks and dynamic internationalization capabilities on international performance. J World Bus 51(3):391–403

Putnam RD (1995) Tuning in, tuning out: the strange disappearance of social capital in America. Polit Sci Polit 28(4):664–683

Qasrawi BT, Almahamid SM, Qasrawi ST (2017) The impact of TQM practices and KM processes on organisational performance: An empirical investigation. Int J Qual Reliab Manag 34(7):1034–1055

Qi C, Chau PYK (2018) Will enterprise social networking systems promote knowledge management and organizational learning? An empirical study. J Organ Comput Electron Commer 28(1):31–57

Reagans R, McEvily B (2003) Network structure and knowledge transfer: the effects of cohesion and range. Adm Sci Q 48(2):240–267

Rezaei M, Jafari-Sadeghi V, Bresciani S (2020) What drives the process of knowledge management in a cross-cultural setting: the impact of social capital. Eur Bus Rev 32(3):485–511

Ritala P, Stefan I (2021) A paradox within the paradox of openness: the knowledge leveraging conundrum in open innovation. Ind Mark Manag 93:281–292

Saleh A, Bista K(2017) Examining factors impacting online survey response rates in educational research: perceptions of graduate students. Online Submission 13(2):63–74

Savalei V (2020) Improving fit indices in structural equation modeling with categorical data. Multivar Behav Res 56:390–407

Setia M (2016) Methodology series module 5: sampling strategies. Indian J Dermatol 61:505–509

Shahzad M, Qu Y, Zafar AU, Rehman SU, Islam T (2020) Exploring the influence of knowledge management process on corporate sustainable performance through green innovation. J Knowl Manag 24(9):2079–2106

Shariq SM, Mukhtar U, Anwar S (2019) Mediating and moderating impact of goal orientation and emotional intelligence on the relationship of knowledge oriented leadership and knowledge sharing. J Knowl Manag 23(2):332–350

Sheng ML, Hartmann NN (2019) Impact of subsidiaries’ cross-border knowledge tacitness shared and social capital on MNCs' explorative and exploitative innovation capability. J Int Manag 25(4):100705

Shraah A, Abu-Rumman A, Alqhaiwi L, AlShaar H (2022) The impact of sourcing strategies and logistics capabilities on organizational performance during the COVID-19 pandemic: Evidence from Jordanian pharmaceutical industries. Uncertain Supply Chain Manag 10(3):1077–1090

Swanson E, Kim S, Lee SM, Yang JJ, Lee YK (2020) The effect of leader competencies on knowledge sharing and job performance: Social capital theory. J Hospit Tour Manag 42:88–96

Syed A, Gul N, Khan HH, Danish M, Ul Haq SM, Sarwar B, Ahmed W (2021) The impact of knowledge management processes on knowledge sharing attitude: the role of subjective norms. J Asian Financ Econ Bus 8(1):1017–1030

Tsai YH, Ma HC, Lin CP, Chiu CK, Chen SC (2014) Group social capital in virtual teaming contexts: a moderating role of positive affective tone in knowledge sharing. Technol Forecast Soc Change 86:13–20

Valk R, Planojevic G (2021) Addressing the knowledge divide: Digital knowledge sharing and social learning of geographically dispersed employees during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Glob Mobil Home Expatriate Manag Res 9(4):591–621

Wang L, Huo D, Motohashi K (2019) Coordination mechanisms and overseas knowledge acquisition for Chinese suppliers: the contingent impact of production mode and contractual governance. J Int Manag 25(2):100653

Xie L, Guan X, Huan TC (2019) A case study of hotel frontline employees’ customer need knowledge relating to value co-creation. J Hospitality Tour Manag 39:76–86

Ye X, Wang Z, Zhang Y, Li H (2021) How do knowledge governance mechanisms impact on repatriate knowledge transfer intention? The moderating role of perceived career and repatriation support and person-organization fit. Manag Decisi 59(2):324–340

Yilmaz C, Hunt SD (2001) Salesperson cooperation: the influence of relational, task, organizational, and personal factors. J Acad Mark Sci 29(4):335–357

Yong JY, Yusliza MY, Ramayah T, Chiappetta Jabbour CJ, Sehnem S, Mani V (2020) Pathways towards sustainability in manufacturing organizations: empirical evidence on the role of green human resource management. Bus Strategy Environ 29(1):212–228

Zaim H, Muhammed S, Tarim M (2019) Relationship between knowledge management processes and performance: critical role of knowledge utilization in organizations. Knowl Manag Res Pract 17(1):24–38

Zhao G, Hormazabal JH, Elgueta S, Manzur JP, Liu S, Chen H, Chen X (2021) The impact of knowledge governance mechanisms on supply chain performance: empirical evidence from the agri-food industry. Prod Plan Control 32(15):1313–1336

Zhao WX, Peng MYP, Liu F (2021) Cross-cultural differences in adopting social cognitive career theory at student employability in PLS-SEM: the mediating roles of self-efficacy and deep approach to learning. Front Psychol 12:586839

Zhou L, Chen Z, Peng MYP (2022) The role of relational embeddedness in enhancing absorptive capacity and relational performance of internationalized SMEs: evidence from mainland China. Front Psychol 13:896521

Zhou L, Peng MYP, Shao L, Yen HY, Lin KH, Anser MK (2021) Ambidexterity in social capital, dynamic capability, and SMEs’ performance: quadratic effect of dynamic capability and moderating role of market orientation. Front Psychol 11:584969

Acknowledgements

This study is supported by Philosophical and Social Science Planning Project of Guangdong Province (GD23CJY15).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Michael Yao-Ping Peng composed the conception and design and drafted the article; interpreted data and revised it critically for important intellectual content; collaborated with the writing of the study; provided data methodology and analysis help.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Approval for this study was obtained from the Ethics Committee of Foshan University. The procedures used in this study adhere to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. The ethical approval was requested and granted in August 2023, prior to the commencement of data collection.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all participants and/or their legal guardians prior to their participation in the study. Participants were informed about the nature and purpose of the study, as well as their rights to withdraw at any time without any consequences. The informed consent process was conducted from September to October 2023, concurrently with the distribution of the questionnaires.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Peng, M.YP. Breaking down barriers: exploring the impact of social capital on knowledge sharing and transfer in the workplace. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11, 1007 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03384-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03384-9

- Springer Nature Limited