Abstract

Entrepreneurship is of great significance to individuals, families and society. Recently, intrapreneurship, i.e., business ventures within established organisations, has also attracted widespread interest among individuals and organisations. However, we still know little about how individuals make decisions when they face diverse types of entrepreneurial activities. Based on theories of entrepreneurial action and conservation of resources and the literature on family embeddedness, this paper proposes an integrated framework for entrepreneurial choice—including intrapreneurship, self-employment and non-entrepreneurship, and examines the roles of socio-cognitive traits and family contingency factors in the entrepreneurial choice process. By using secondary and survey data, the empirical results show that (a) entrepreneurial alertness (EA) and self-efficacy (ESE) both positively affect individuals’ choice towards intrapreneurship and self-employment, with a stronger effect on the latter; (b) the interaction between EA and ESE has a negative effect on intrapreneurship but a positive effect on self-employment; (c) family-to-work conflict weakens the aforementioned interactive effect on both intrapreneurship and self-employment, whereas work-to-family conflict strengthens its effect on self-employment; (d) household income strengthens the interactive effect on both intrapreneurship and self-employment. Overall, these findings contribute to a nuanced understanding of the relationship among individual cognitive traits, family contingencies and entrepreneurial choice. The theoretical and practical implications are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Entrepreneurship, as a challenging but exciting career choice, not only profoundly influences individual development but also acts as a vital force driving socio-economic innovation and growth. Scholars have noted that most successful entrepreneurs have also been employed by established organisations (Sørensen and Fassiotto, 2011). Despite this, numerous individuals with entrepreneurial talents choose to stay within organisations. They engage in proactive intrapreneurship by improving, refining and developing products and services, which enhances organisational profitability and contributes to its expansion (Antoncic, 2007; Elert and Stenkula, 2022). Especially in the digital era, the significant role of intrapreneurship for individuals, organisational development and economic growth is supported by the literature (Reibenspiess et al., 2022; del Olmo-García et al., 2023). Compared with the practice of intrapreneurship in full swing, however, we still know little about the factors that promote and hinder intrapreneurship, especially the individual decision-making process when faced with the trade-off between intrapreneurship and self-employment.

Prior research identifies entrepreneurship as a process of opportunity identification and development (Ardichvili et al., 2003). Some literature further suggests that an individual’s decision to embark on an entrepreneurial venture (i.e., whether or not to start a business) is based on a rational assessment of risks and return (Hsu et al., 2017; Kaul et al., 2024). Nevertheless, when we acknowledge that intrapreneurship is also an optional entrepreneurial choice for individuals, the literature becomes insufficient to help us fully comprehend the entrepreneurial decision-making process. Are the factors that determine intrapreneurship similar to those of self-employment? If so, why do some people choose intrapreneurship over self-employment? If not, which factors contribute more to intrapreneurship? These questions are still not satisfactorily answered. In particular, there remains a significant research gap as to which contingency factors play a role and how they operate when individuals are faced with the trade-offs among multiple entrepreneurial options.

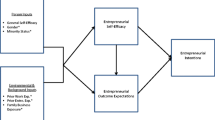

In this paper, we integrate intrapreneurship and self-employment into an entrepreneurial choice framework. Based on the theories of entrepreneurial action and conservation of resources, we discuss the impact of two socio-cognitive traits—entrepreneurial alertness and entrepreneurial self-efficacy on entrepreneurial choice. Furthermore, we explore the contingency role of work–family conflict and household income in entrepreneurship from a family embeddedness perspective. We find that, on the one hand, entrepreneurial alertness and self-efficacy both have a positive impact on intrapreneurship, which is similar to the impact on self-employment, but on the other hand, individuals with both high entrepreneurial alertness and self-efficacy are less likely to engage in intrapreneurship, and their impact on self-employment differs. Also, the above relationships change subtly for individuals with different levels of work–family conflict and household income. In summary, we confirm that entrepreneurial choice is a process of identifying and developing entrepreneurial opportunities and highlight that it is also a process of resource conservation, investment and loss avoidance, in which individual cognitive traits and family factors play an important role.

Literature review and hypotheses development

Entrepreneurship and intrapreneurship

The literature on entrepreneurial choice suggests that if individuals wish to obtain high entrepreneurial rents, they may engage in self-employment, become employers or entrepreneurs, otherwise they will choose to become paid employees or non-entrepreneurs (Burton et al., 2016; Su et al., 2022). Recent literature has shown interest in two types of entrepreneurial behaviours among employees, namely intrapreneurship and hybrid entrepreneurship. The former refers more to the process of developing opportunities within an organisation (Parker, 2011; Blanka, 2019), while the latter refers to starting a business independently while remaining as an employee (Raffiee and Feng, 2014; Sun et al., 2020). In this paper, we divide individual entrepreneurial choice into three categories: non-entrepreneurship, intrapreneurship and self-employment. We view hybrid entrepreneurship as a special form of self-employment, which allows us to focus on the difference between intrapreneurship and self-employment.

The mainstream view on entrepreneurship is that entrepreneurship is a process of discovering and developing business opportunities (Ardichvili et al., 2003; Douglas et al., 2021), and those who engage in entrepreneurial activities are considered entrepreneurs. The definition of intrapreneurship is quite divided, and one important reason is that the literature has different understandings of who an intrapreneur is (Neessen et al., 2019; Blanka, 2019). From an opportunity view, intrapreneurship refers to the practice of establishing new projects within mature organisations to develop opportunities and create economic value (Parker, 2011). However, such a definition still does not allow us to identify who an intrapreneur is. Therefore, some literature focuses on employee intrapreneurship, defining it as the behaviour of employees showing initiative, taking risks and developing new ideas in their work (de Jong et al., 2015; Badoiu et al., 2020). Further, Gawke et al. (2017, 2018) argue that intrapreneurship is similar to innovative work behaviour and is a special kind of proactive behaviour associated with organisational change or improvement, which mainly includes two dimensions—strategic renewal and business venturing (Gawke et al., 2019), and distinguish it from proactive behaviour that aims to achieve compatibility between individual and organisational contexts, as well as organisational citizenship behaviour and job crafting.

The earliest research on intrapreneurship suggests that the factors that drive intrapreneurship are similar to those that drive entrepreneurship (Pinchot, 1985; Hisrich, 1990). This statement fails to take fully into account the embeddedness of intrapreneurs as employees with stable jobs rather than as self-employed (Camelo-Ordaz et al., 2012). Thus, it is a false assumption to equate intrapreneurs with entrepreneurs. Subsequent studies explore the individual and organisational factors that influence intrapreneurship (Menzel et al., 2007; Martín-Rojas et al., 2013; Niemann et al., 2022). These studies, however, fail to explain a key question—why some individuals choose to be intrapreneurs while others start their own businesses, even if they have similar entrepreneurial talents. Therefore, some studies suggest that entrepreneurship and intrapreneurship are distinct behaviours, and the differences in entrepreneurial cognitive traits ultimately lead to different results (Douglas and Fitzsimmons, 2013; Adachi and Hisada, 2017) and create terms such as intrapreneurial self-efficacy (Deprez et al., 2021; Rabl et al., 2023) and intrapreneurial intention (Chouchane et al., 2023). Although the above research contributes a great deal of important knowledge to intrapreneurship, the proliferation of terminology may weaken its true impact.

There is also some literature that focuses on the contingency factors that affect self-employment and entrepreneurship, respectively, and recent research mainly explores the influencing factors of entrepreneurship and intrapreneurship in the institutional context (Boudreaux et al., 2019; Urbano et al., 2024). But surprisingly, the role of family as an important force influencing individual decision-making, has been overlooked to some extent. Specifically, the literature on self-employment discusses the role of family based on theories such as social capital, human capital and social support (Edelman et al., 2016; Ruef, 2020). To our knowledge, however, there is no literature that examines the impact of family on intrapreneurship. Given the profound influence of family on work and entrepreneurial decisions, the gap in the literature is surprising. From a family embeddedness perspective (Aldrich and Cliff, 2003), therefore, we suggest that family background may be a key contingency context that leads individuals to show preferences in the choice between intrapreneurship and self-employment.

Socio-cognitive traits and entrepreneurial choice

Social cognitive theory provides a perspective that integrates individual cognitive, behavioural, and environmental factors to understand human behaviour (Bandura, 1989). In the field of entrepreneurship research, scholars have well explored the effects of individual socio-cognitive traits, such as entrepreneurial alertness and self-efficacy, on entrepreneurial intention and behaviour (Boudreaux et al., 2019; Schade and Schuhmacher, 2022). In contrast to the prior literature, we discuss the impact of socio-cognitive traits on entrepreneurial choice more comprehensively in a framework that includes both intrapreneurship and self-employment.

Entrepreneurial alertness (EA)

The alertness to opportunities is the core and foundation of identifying entrepreneurial opportunities (Lanivich et al., 2022). From a social cognitive perspective, Tang et al. (2012) conceptualised entrepreneurial alertness as an individual’s sensitivity and insight into potential business opportunities. It helps individuals search, connect and evaluate environmental information to identify profitable entrepreneurial opportunities. First, by understanding the customer issues and ways to serve the market, individuals with high entrepreneurial alertness can capture market needs and subtle changes that have been overlooked by others, which provides a rich information base for identifying opportunities (Arentz et al., 2013). Second, individuals with high entrepreneurial alertness are good at connecting seemingly independent or less relevant information with resources at their disposal and thinking about entrepreneurial opportunities that are not easily perceived or considered non-existent by others (Tang et al., 2021). Finally, individuals with high entrepreneurial alertness can better assess the value of business opportunities (Levasseur et al., 2022).

To sum up, we suggest that entrepreneurial alertness is conducive to individuals capturing more information and better integrating this information and resources at their disposal to identify profitable business opportunities. As entrepreneurial behaviour revolves around entrepreneurial opportunities, high entrepreneurial alertness is beneficial for individuals to engage in entrepreneurial activities. Considering that some information and resources are not owned by individuals—such as the resources owned by the organisation where individuals are employed or the information from the stakeholders of the organisation, we further suggest that entrepreneurial alertness is not only conducive to self-employment, but also promotes individuals to carry out entrepreneurial ventures within established organisations to a certain extent. Nevertheless, the impact on intrapreneurship may be weaker than that on self-employment because, on the one hand, organisational inertia and bureaucracy may hinder or delay the opportunity development process (Sørensen, 2007; Li et al., 2023), and on the other hand, opportunities identified by individuals may not align with organisational goals, and thus employers may hold a negative attitude towards intrapreneurship (Urbig et al., 2021). In these circumstances, self-employment is still a better entrepreneurial choice for individuals who are alert to opportunities. Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1 (H1). Entrepreneurial alertness (a) has a significant positive effect on intrapreneurship, and (b) has a significant positive effect on self-employment, but (c) the positive effect on intrapreneurship is significantly weaker than that of self-employment.

Entrepreneurial self-efficacy (ESE)

Perceived self-efficacy refers to the subjective cognition and evaluation of an individual’s ability to participate in a specific behaviour (Bandura, 1989). The impact of self-efficacy on entrepreneurial behaviour and intention has been extensively discussed in the context of self-employment (e.g., Chen et al., 1998; Zhao et al., 2005). We suggest that perceived self-efficacy, related to entrepreneurship, is also an important antecedent for individuals to participate in intrapreneurial activities because, first, individuals with high entrepreneurial self-efficacy can gain more career development opportunities through intrapreneurship. For instance, by successfully developing business opportunities through intrapreneurship, intrapreneurs can reap both financial and intrinsic rewards (Urban and Nikolov, 2014), especially when employers introduce a higher profit-sharing mechanism or an equity allocation mechanism (Monsen et al., 2010). Second, not only individuals but also many organisations are motivated to perform intrapreneurial activities to achieve strategic renewal or corporate entrepreneurship, in which case the organisation encourages employees with entrepreneurial capabilities to engage in intrapreneurial activities and even recruit talents from outside (Ng and Sherman, 2022). Third, the resources and knowledge that individuals possess may only be effective in specific fields or organisations, which limits individuals with high entrepreneurial self-efficacy from choosing to start their own businesses. Especially when resources and knowledge are embedded in the organisation and cannot be transferred outside the organisation, it is unrealistic for individuals to establish a new enterprise (Marx et al., 2009), and then intrapreneurship can serve as an alternative option. Nevertheless, the impact of entrepreneurial self-efficacy on intrapreneurship may not be as strong as that on self-employment, as intrapreneurs have clear and specific roles within the organisation (Menzel et al., 2007), which may not encompass all dimensions of entrepreneurial self-efficacy, thereby constraining its potential for impact. To sum up, we suggest that while intrapreneurship provides an outlet for entrepreneurial self-efficacy, it is not the primary one. Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2 (H2). Entrepreneurial self-efficacy (a) has a significant positive effect on intrapreneurship and (b) has a significant positive effect on self-employment, but (c) the positive effect on intrapreneurship is significantly weaker than that of self-employment.

Interaction of EA and ESE

The influence of socio-cognitive traits such as alertness and self-efficacy on entrepreneurship has attracted sufficient attention in the literature, and several studies have discussed their interrelationship in recent years as well (Tang et al., 2023; Araujo et al., 2023). In this paper, we do not intend to discuss the causal relationship between the two but rather treat them as two independent individual traits and focus our research on understanding the impact of their interaction on entrepreneurial choice. Based on theories of entrepreneurial action (McMullen and Shepherd, 2006) and conservation of resources (Hobfoll et al., 2018), we suggest that although entrepreneurial alertness and self-efficacy have a positive impact on intrapreneurship and self-employment, respectively, the impact of their interaction is much more subtle. Specifically, individuals with high entrepreneurial alertness and self-efficacy are less likely to engage in intrapreneurship but more likely to be self-employed, mainly for the following reasons:

First, the impact of entrepreneurial alertness on entrepreneurial choice will be moderated by entrepreneurial self-efficacy. Individuals with high entrepreneurial alertness but low entrepreneurial self-efficacy are more likely to choose intrapreneurship over self-employment. Entrepreneurial action theory suggests that evaluating and utilising opportunities usually involves two stages: attention and evaluation, while entrepreneurial alertness is more related to the identification and judgement of third-person opportunities in the attention stage, but first-person opportunities, i.e., an individual’s evaluation of the opportunities they have, are more significant to entrepreneurial behaviour (McMullen and Shepherd, 2006; Tang et al., 2012). Higher entrepreneurial self-efficacy means that individuals have more action-specific knowledge and skills about entrepreneurship, as well as lower uncertainty perception and fear of failure, and are therefore more likely to activate the process of evaluating third-person opportunities, recognising the opportunity as their own and then initiating and exploiting it (Townsend et al., 2018; Boudreaux et al., 2023). On the contrary, when entrepreneurial self-efficacy is low, the second stage of the evaluation process will not be initiated. According to the COR theory, the loss and the acquisition of resources are asymmetrical, and the impact of loss is more prominent than the gain (Halbesleben et al., 2014; Hobfoll et al., 2018). Thus, individuals who have good alertness to opportunities but lack the necessary abilities to start a business will follow the primacy of loss principle, and are less likely to choose self-employment with a high risk of failure. But we also do not believe that individuals will choose to give up third-person opportunities easily, in which case an organisational context may provide individuals with some resources that they do not have on their own—such as funds, teams, suppliers and customers, as well as entrepreneurial mentoring, and therefore potential entrepreneurs who are lacking in entrepreneurial ability may combine their alertness with organisational resources to develop business opportunities.

Second, the impact of entrepreneurial self-efficacy on entrepreneurial choice will be moderated by entrepreneurial alertness. When entrepreneurial alertness is low, individuals do not acknowledge the existence of third-person opportunities in the first place, let alone the subsequent evaluation and development process, so even if individuals believe that they have the skills and abilities necessary to start a business, they are less likely to take entrepreneurial action in this situation. At the same time, however, we suggest that individuals who are less alert to opportunities but have higher entrepreneurial self-efficacy are more likely to engage in intrapreneurship. This is because, although individuals do not perceive good business opportunities to motivate them to be self-employed, intrapreneurial activities can still bring them income growth, promotion possibilities and job autonomy (Urban and Nikolov, 2014). Thus, following the resource investment principle, they are more likely to capitalise their knowledge and skills into higher salaries and promotion opportunities through intrapreneurship.

To sum up, we suggest that individuals with both high entrepreneurial alertness and self-efficacy are more likely to be self-employed, while individuals who lack one of the two aspects are more likely to combine their strengths with established organisations and engage in intrapreneurship. Based on the view of COR, there are two other reasons that may lead to a lack of motivation for individuals with both high alertness and self-efficacy to engage in intrapreneurship. First, when utilising business opportunities through intrapreneurship, it is to some extent to foster a strong competitor for potential future entrepreneurship, especially when the opportunity is unique and not easily perceived by others. In this case, alternative strategies include temporarily forgoing the development of this opportunity and engaging in hybrid entrepreneurship outside the organisation while retaining the role of employee (Sun et al., 2020). Second, when intrapreneurs have accumulated sufficient entrepreneurial experience or are trained to be more alert to opportunities, they may break away from established organisations, start their own businesses and earn higher entrepreneurial rents. This may lead to the underrepresentation of individuals with both high entrepreneurial alertness and self-efficacy among intrapreneurs. Based on the above analysis, we propose the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 3 (H3). The interaction of entrepreneurial alertness and entrepreneurial self-efficacy has (a) a significant negative effect on intrapreneurship, but (b) a significant positive effect on self-employment.

Family embeddedness and entrepreneurial choice

The family embeddedness perspective in the field of entrepreneurship originates from Aldrich and Cliff’s (2003) pioneering research, which finds that North American households tend to shrink and suggests that this shift in household size has a profound impact on the emergence of business opportunities, opportunity perception, entrepreneurial decisions and household resource mobilisation. Subsequent studies have further developed this view, pointing out that the influence of family on individual entrepreneurial behaviour is a whole-lifecycle, multidimensional and double-edged process (Sieger and Minola, 2017; Huang et al., 2024). On the one hand, individuals can make full use of the time, human resources, financial capital, knowledge, information and emotional support provided by their families to carry out their own entrepreneurial activities (Dyer et al., 2014; Edelman et al., 2016). On the other hand, due to the inherent interactive relationship between family and entrepreneurship that carries expectations of reciprocity and fairness (Kwon and Adler, 2014; Xu et al., 2020), if family expectations of entrepreneurship are not met, family embeddedness may lead to conflicts among family members, putting resources at risk, which in turn negatively affects entrepreneurial decision-making and its performance (Edelman et al., 2016; Sieger and Minola, 2017). In this paper, we focus on the effect of two contingency factors related to family embeddedness—work–family conflict and household income on entrepreneurial choice. The COR theory suggests that individuals have a tendency to conserve, protect and acquire resources. Both potential threats to resources and actual losses will increase the stress experienced by individuals (Halbesleben et al., 2014; Hobfoll et al., 2018). For entrepreneurs, these threats include uncertainties, opportunity costs and the potential loss of time, energy and other resources during the entrepreneurial process (Lanivich, 2015).

Work–family conflict

Work–family conflict reflects the competitive and incompatible relationship between an individual’s different roles in the work and family domains (Greenhaus and Beutell, 1985). First, in the case of high work–family conflict, the time and energy that individuals devote to entrepreneurial activities will be greatly limited, making it difficult for individuals to give their all. Especially in the early stages of entrepreneurship, it requires a great deal of commitment and work (Ronstadt et al., 1988), which requires a redistribution of resources between family and entrepreneurial ventures and may exacerbate the conflict between work and family. Therefore, when the conflict is high, individuals with high entrepreneurial alertness or self-efficacy will activate a defence mode to protect family resources from loss. According to the primacy of loss principle (Hobfoll et al., 2018), they are less likely to start their own business. However, compared to self-employment, although intrapreneurship also poses challenges to family roles, its duties are relatively clear and well-designed, which requires much less time and effort (Menzel et al., 2007). According to the self-regulation theory, individuals can achieve a better work–family balance by reducing inefficient labour through intrapreneurship and then achieving individualised work arrangements (Grawitch et al., 2010), thus, individuals with high entrepreneurial alertness or self-efficacy are more motivated to engage in intrapreneurship on the premise of avoiding losses. Second, the family embeddedness perspective argues that family support becomes particularly significant in the process of starting a business, and in the case of high work–family conflict, individuals may lack resource and emotional support from their families, which may make entrepreneurship more difficult. At this point, support from established organisations becomes even more valuable, and thus individuals with high entrepreneurial alertness or self-efficacy, or both, are more motivated to engage in intrapreneurship. Finally, work–family conflict is associated with stress, psychological safety and well-being (Allen et al., 2000; Grant-Vallone and Donaldson, 2001), which may lead to individuals with significant family responsibilities to be more inclined to choose a stable job rather than a high-risk entrepreneurial career. Therefore, if individuals are alert to business opportunities or possess the skills and abilities required for entrepreneurship, we expect that intrapreneurial activities to provide outlets for their talents.

The above analysis is based on the assumption that individuals face a high level of work–family conflict. For individuals with low work–family conflict, they are more likely to achieve a balance between work and family, and thus, family embeddedness is beneficial for them to turn opportunities into entrepreneurial actions. Therefore, if individuals have high entrepreneurial alertness or self-efficacy, or both, the resource investment principle prevails and the loss principle takes a back seat (Hobfoll et al., 2018), making them more likely to start their own businesses rather than engage in intrapreneurship. In summary, we propose the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 4 (H4). The effect of entrepreneurial alertness and entrepreneurial self-efficacy on entrepreneurial choice is negatively moderated by work–family conflict, that is, work–family conflict (a) significantly weakens the negative effect of the interaction between EA and ESE on intrapreneurship, and (b) significantly weakens the positive effect on self-employment.

Household income

Next, we analyse the impact of household income. Shortage of funds is the biggest obstacle to entrepreneurship (Pissarides, 1999). Among the many sources of entrepreneurial funding, financial support from households has lower transaction costs and fewer strings attached (Steier, 2003), thus having a significant impact on individual entrepreneurial decision-making. First, the higher the household income, the more likely an individual is to receive the financial support needed for entrepreneurship from their family, and this increases the likelihood of individuals with entrepreneurial alertness and self-efficacy starting their own businesses. Meanwhile, financial support from households is a positive signal for external investors, favouring entrepreneurs to obtain debt financing from outside (Chua et al., 2011), which further promotes entrepreneurship. Second, individuals with higher household incomes may be more inclined to seek high-risk and high-return entrepreneurial opportunities if they have higher entrepreneurial cognitive traits. This is because higher household incomes provide potential entrepreneurs with more psychological security, especially financial risk tolerance (Chiang and Xiao, 2017), and therefore motivated by resource acquisition rather than resource conservation, they are willing to take on the risk of trying something new and achieve asset appreciation. Third, higher household incomes allow individuals to pursue higher levels of autonomy, satisfaction, and overall economic well-being of the household (Stephan, 2018), therefore, in households with higher incomes, individuals with higher entrepreneurial cognitive traits are more likely to pursue non-monetary goals and start businesses. For them, the resources provided by established organisations are less important, and the benefits added from intrapreneurship are expected to be smaller than that of self-employment. On the contrary, if they have lower alertness and self-efficacy, they will reduce entrepreneurial activities in order to protect their household wealth, and their motivation to participate in intrapreneurship is also lower, whether in perspectives from developing opportunities or earning money. Therefore, we expect that individuals with high entrepreneurial alertness or self-efficacy, or both, will take advantage of their household wealth to develop business opportunities, start their own businesses and thus reduce the likelihood of engaging in intrapreneurship.

Conversely, when the family is strapped for money, it is obviously difficult to provide the financial capital needed to start a business. In this case, established organisations provide intrapreneurial employees with the necessary capital, technology, executive teams and other resources (Martín-Rojas et al., 2013). Therefore, we expect that if individuals have high entrepreneurial alertness or self-efficacy, or both traits, they are more likely to engage in intrapreneurship when they do not receive adequate financial support from their family, rather than self-employment outside the organisation, and thus, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 5 (H5). The effect of entrepreneurial alertness and entrepreneurial self-efficacy on entrepreneurial choice is positively moderated by household income, that is, household income (a) significantly strengthens the negative effect of the interaction between EA and ESE on intrapreneurship, and (b) significantly strengthens the positive effect on self-employment.

Study 1

Methods

Data sources

We obtained entrepreneurial choice, entrepreneurial alertness, entrepreneurial self-efficacy, as well as individual-level control variables from the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM) database. The GEM is one of the largest ongoing surveys of multinational entrepreneurship dynamics. Since 2011, the GEM has organised its special survey on entrepreneurship, as it has attracted increasing attention. Due to the disclosure of the full datasets by the GEM 3 years after the survey ended, the years we analysed in this study were from 2011 to 2019. Some procedures were used to clean up the data set in order to get clearer and more accurate empirical results: first, since our research topic was entrepreneurship and career decision-making, we only retained workforce aged between 18 and 64 in the sample. Second, we excluded observations with missing values in key variables in order to make the results comparable among different models. Third, since a very small number of respondents had very large household sizes, in order to prevent the regression results from being affected by extreme values, we truncated the right 0.1% of the household size variable. Our final sample comprises 704,515 observations from 97 economies, with annual observation counts ranging between 63,575 and 98,852. We matched data on GDP per capita and unemployment rates at the regional level from the websites of the World Bank and the International Labour Organization as control variables.

Measures

Entrepreneurial choice (EC)

It was a multi-categorical variable, and we measured it using multiple questions. If an individual was trying to start a new venture for their employer, we considered the choice to be intrapreneurship (encoded as 1). If an individual was trying to start a business for themselves, the choice was self-employment (encoded as 2). Respondents who had not engaged in entrepreneurial or intrapreneurial activities were encoded as 0. We excluded respondents who reported earning a living due to a scarcity of jobs, as their entrepreneurial motivation did not meet our assumption about entrepreneurial choice.

Entrepreneurial alertness (EA)

Respondents were asked if they found good opportunities for starting a business. Since the core of alertness lies in identifying profitable opportunities (Tang et al., 2012; Boudreaux et al., 2019), we assessed EA using the responses to this question. If the answer was yes, alertness was relatively high (encoded as 1). If no, alertness was relatively low (encoded as 0).

Entrepreneurial self-efficacy (ESE)

Respondents were asked if they had the knowledge, skills and experience necessary to start a business. Referring to the literature (Shahriar, 2018; Schade and Schuhmacher, 2022), we assessed ESE using the responses to this question. It was also a dummy variable and a ‘yes’ answer was encoded as 1, otherwise as 0.

Household size (Size)

Respondents were asked how many permanent household members there were, including themselves. The bigger the household, the higher the level of work–family conflict. We used this variable as a proxy for work–family conflict mainly for the following reasons: first, a bigger household often entails greater family-related responsibilities, necessitating a more substantial allocation of time and attention resources to family matters, which may lead to conflicts with work duties (Yang et al., 2000; Masuda et al., 2019). Second, although the literature distinguishes between work-to-family conflict (WFC) and family-to-work conflict (FWC), Greenhaus and Beutell (1985) have proposed that work–family conflict is non-directional in nature. An increase in family needs due to a bigger household size can thus interfere with both family and work domains (Chen and Cheng, 2023). Therefore, although using household size as a proxy had significant limitations, it was considered an acceptable measure in the absence of more precise measures.

Household income (Income)

The GEM divided respondents’ household income into three categories: high, middle and low income (one-third each). We graded the variable from low to high, with values of 1, 2 and 3, respectively.

Control variables

Referring to the literature (Douglas and Fitzsimmons, 2013; Adachi and Hisada, 2017; Huang et al., 2024), we controlled for gender, age and its squared and education at the individual level, as well as GDP per capita (logarithm) and unemployment rate (UnRate) at the regional level.

Empirical strategy

Since the dependent variable in this study was multi-categorical, we used multinomial logistic models for empirical testing:

where \(k\) denotes an individual takes a type \(k\) entrepreneurial choice \((k=1,\,2)\), \(P(Y=k)\) denotes its probability, and \(P(Y=0)\) denotes the probability that an individual takes a choice of non-entrepreneurship. \({{\rm {EA}}}\) and \({{\rm {ESE}}}\) are the independent variables. \({{\rm {Controls}}}\) denotes a set of control variables, including gender, age and its square, education, GDP per capita and unemployment rate mentioned above, and year dummies. \({\beta }_{ik}\,(i=\mathrm{0,1,2},\ldots )\) are the coefficients, and \(\varepsilon\) is the error term. We clustered standard errors at economy level, i.e., we allowed error terms to be correlated within economies.

Next, we changed the baseline group from non-entrepreneurship to intrapreneurship and set the following model:

where \(j=0,\,2\).

On the basis of Eq. (1), the interaction of EA and ESE was added to test H3a and H3b:

And on the basis of Eq. (3), the two-way and three-way interactions were added to test H4 and H5:

where \({{\rm {MV}}}\) is a moderating variable, which can be replaced by household size and income. We used two indicators, log pseudo-likelihood and Pseudo-R2, to evaluate the fitness of models (Shinnar et al., 2018), both of which are larger is better. We performed empirical testing using R.

Results

Table 1 reports the results of descriptive statistics, and Table 2 reports the correlation coefficients between variables.

Table 3 presents the results of multinomial logistic regression. In Model 1, EA had both a positive effect on individual choice of intrapreneurship (RR = 1.449, 95% CI [1.323, 1.586]) and self-employment (RR = 2.475, 95% CI [2.231, 2.745]). Therefore, H1a and H1b were supported. ESE had both a positive effect on intrapreneurship (RR = 2.126, 95% CI [1.966, 2.299]) and self-employment (RR = 5.202, 95% CI [4.712, 5.744]), so H2a and H2b were supported as well. We ran Model 2 to test H1c and H2c. The components of Model 2 and Model 1 were the same, but we changed the baseline group from non-entrepreneurship (EC = 0) to intrapreneurship (EC = 1). It can be found that individuals with high EA (RR = 1.708, 95% CI [1.590, 1.834]) and high ESE (RR = 2.447, 95% CI [2.248, 2.664]) were more likely to choose self-employment than intrapreneurship. Therefore, H1c and H2c were supported.

In Model 3, we added the interaction EA × ESE, and the result showed that the interaction was significantly negatively correlated with intrapreneurship (RR = 0.777, 95% CI [0.703, 0.859]), which indicated individuals with both high EA and ESE were less likely to engage in intrapreneurial activities, and thus H3a was supported. As another entrepreneurial choice, we can see that the interaction was positively correlated with self-employment but not significant (RR = 1.048, p = 0.426). In Model 4, we simultaneously added EA, ESE, Size, the interactions between them three, as well as the three-way interaction. The interaction EA × ESE × Size was not significant (RR = 1.001, p = 0.947), and thus H4a was not supported. The larger the household, the positive effect of EA × ESE on self-employment was weakened (RR = 0.971, 95% CI [0.945, 0.999]), and thus H4b was supported. In Model 5, we simultaneously added EA, ESE and Income, the interactions between them three, as well as the three-way interaction. The last interaction was significantly negatively correlated with intrapreneurship (RR = 0.805, 95% CI [0.747, 0.869]), indicating individuals with higher household income were less likely to participate in intrapreneurial activities if they had both high EA and ESE, and thus H5a was supported. The higher the household income, the positive effect of EA × ESE on self-employment was strengthened (RR = 1.145, 95% CI [1.055, 1.243]), and thus H5b was supported.

The literature suggests that when the dependent variable is categorical, the coefficient of the interaction may be insufficient to support the existence of an interaction effect (Mustillo et al., 2018). As shown in Fig. 1, we plotted graphs on the interactions to further understand these effects (Dawson and Richter, 2006; Hoetker, 2007; Dawson, 2014). In subfigure (b), two lines sloping upwards to the right indicated that EA had a positive effect on self-employment, regardless of whether ESE was high or low. When ESE took 1, the distance between the two lines increased, indicating a positive effect of the interaction on self-employment, and thus H3b was supported.

a The interaction between EA and ESE has a negative impact on intrapreneurship. b The interaction between EA and ESE has a positive impact on self-employment. c The interaction of EA, ESE and household size has no significant impact on intrapreneurship. d The interaction of EA, ESE and household size has a negative effect on self-employment. e The interaction of EA, ESE and household income has a negative effect on intrapreneurship. f The interaction of EA, ESE and household income has a positive impact on self-employment.

Discussion

The above results support most of the hypotheses to a large extent, but there are some serious limitations in the methodology, including: first, independent variables were both dummies that relied on a single item, which threatened the construct validity. In fact, the literature has raised concerns about the use of single items to measure related constructs (Lanivich et al., 2022). Additionally, when the dependent variable was categorical, this also impacted the inferential robustness of the interaction term. Second, we used household size as a proxy variable for work–family conflict, which was questionable to some extent. On the one hand, this did not allow us to examine the independent impacts of WFC and FWC more nuancedly. On the other hand, household size is also related to human resources and social capital that foster self-employment (Ruef, 2020; Huang et al., 2024). However, due to the availability of data, we were unable to rule out these influences. Third, individual-level variables were all self-reported and most of them were categorical, making it difficult to assess the effect of CMB on the results. Forth, the GEM does not release the survey results for that year until 3 years after the survey ends. In this study, individuals were interviewed in years between 2011 and 2019, which might threaten the timeliness of the conclusions.

Study 2

Methods

Sample and procedure

We conducted an extended replication survey in China to compensate for the limitations of Study 1. We collected data from seventeen subdistricts across five cities by collaborating with community committees and putting up posters, employing both paper and electronic questionnaires. To reduce potential common method bias, we also balanced the order of questions in the questionnaire (Podsakoff et al., 2003). Out of the 462 questionnaires collected, only those completed by working-age respondents (ages 18–64) were retained. Questionnaires with omissions or errors in key questions were excluded from the analysis. Ultimately, 363 questionnaires were considered valid, resulting in an effective response rate of 78.6%. In the final sample, 45.7% of respondents were female, the average age was 39 (SD = 13.68), 68.6% had a high school diploma or higher, 84.6% were employed by established organisations, and 5.2% had entrepreneurial experience. English measures used in the study were translated into Chinese following a back-translation approach (Brislin, 1970).

Measures

Intrapreneurship behaviour (IB)

We used the venture behaviour scale developed by Gawke et al. (2019), which was a new achievement in measuring intrapreneurship and had been validated by subsequent research (Gorgievski et al., 2023). The scale consisted of seven items and one example item was ‘I conceptualise new products for an established organisation.’ Using 7-point measurement, 1 = never, 7 = always.

Self-employment (SE)

Some entrepreneurship research projects, such as the GEM and Panel Study of Entrepreneurial Dynamics (PSED), captured the gestation activities during the entrepreneurial process through a checklist. Referring to the references (Shinnar et al., 2018; Neneh, 2019), we described entrepreneurial behaviour through 10 items. An example item was ‘I’m collecting information about markets or competitors.’ All questions were required to answer yes or no.

Entrepreneurial alertness (EA)

We used a short version of Tang et al. (2012) entrepreneurial alertness scale with seven items. The short scale has been shown to be effective and more in line with the Chinese research context (Araujo et al., 2023; Tang et al., 2023). An example item was ‘I can distinguish between profitable opportunities and not-so-profitable opportunities.’ Using 7-point measurement, 1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree.

Entrepreneurial self-efficacy (ESE)

We used a three-item scale developed by Schjoedt and Craig (2017). The scale was developed based on the PSED project and was similar to the GEM items. An example item was ‘My skills and abilities will help me start a business.’ Using 7-point measurement, 1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree.

Work-to-family conflict (WFC) and family-to-work conflict (FWC)

We used Netemeyer et al. (1996) scale with two dimensions. One example item for WFC was ‘The demands of my work interfere with my home and family life,’ and one for FWC was ‘The demands of my family interfere with work-related activities.’ Using 7-point measurement, 1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree.

Household income (Income)

Compared with Study 1, we used a more detailed classification method to measure household income. It was divided into 11 groups, ranging from ‘¥30,000 and below’ to ‘above ¥300,000,’ with an interval of ¥30,000 between each group.

Control variables

We controlled for gender, age and its squared, education and entrepreneurial experience.

Model evaluation

We performed confirmatory factor analysis on the five constructs measured using Likert scales, and the results are reported in Table 4. The hypothetical five-factor model showed a good fit to the data (χ2 (314) = 377.657, p = 0.008, CFI = 0.985, RMSEA = 0.024, SRMR = 0.046) and outperformed the others. As a post-hoc CMB test, the result of Harman’s single-factor test showed that the first common factor explained 21.8% of the variance, and thus, we considered that CMB threatened our measures slightly.

Empirical strategy

Compared with Study 1, since the dependent variable was changed from a categorical variable to two ordinal variables, we built two linear models to test the hypotheses. This allowed us to test most hypotheses nuancedly, but it should be noted that under this strategy, we were unable to test H1c and H2c. Considering our focus on interactions, such a trade-off was worthwhile. The setting of interactions remained consistent with Study 1, and we tested the interaction of EA and ESE, as well as the moderating effects of WFC, FWC and household income. We centralised the interactions to mitigate the threat of multicollinearity to the estimated parameters. The mean variance inflation factor (VIF) of modified models ranged from 1.116 to 1.246. We evaluated the goodness of fit for each model by using the adjusted R2.

Results

Descriptive statistics, reliabilities and correlations between variables are reported in Table 5. Compared to men, women had significantly lower IB and SE levels and faced higher FWC.

Table 6 presents the results of linear regression. In Model 1, the coefficients of both EA and ESE were significantly positive (β = 0.090, 95% CI [0.019, 0.162]; β = 0.084, 95% CI [0.005, 0.162]). Thus, H1a and H2a were supported. In Model 2, the interaction EA × ESE was significantly negative (β = −0.082, 95% CI [−0.137, −0.027]), thus H3a was supported. In Models 3–5, we added the moderating variables WFC, FWC and Income, respectively, and their interactions with independent variables. The interaction EA × ESE × WFC was positive but not significant (β = 0.009, 95% CI [−0.030, 0.048]), and the interaction EA × ESE × FWC was significantly positive (β = 0.049, 95% CI [0.006, 0.093]), suggesting that individuals with both high EA and ESE were more likely to engage in intrapreneurship at high FWC levels. Compared with Study 1, these results provided new insights into the important role of FWC, rather than WFC, in individual intrapreneurial decision-making. The interaction EA × ESE × Income was significantly negative (β = −0.027, 95% CI [−0.043, −0.011]), suggesting that individuals with both high EA and ESE were less likely to exhibit intrapreneurial behaviours in high-income households and H5a was therefore supported.

In Model 6, the coefficients of both EA and ESE were significantly positive (β = 0.175, 95% CI [0.047, 0.304]; β = 0.285, 95% CI [0.145, 0.425]), thus H1b and H2b were supported. In Model 7, the interaction EA × ESE was significantly positive (β = 0.102, 95% CI [0.003, 0.201]), thus H3b was supported. In Models 8–10, we added moderating variables and interactions in the same way as above. The interaction EA × ESE × WFC had a positive coefficient and was marginally significant at the 0.10 level (β = 0.064, 95% CI [−0.009, 0.137], 90% CI [0.003, 0.125]), which was contrary to our hypothesis, suggesting that individuals with both high EA and ESE were more likely to start their own businesses at high WFC levels. The interaction EA × ESE × FWC was significantly negative (β = −0.082, 95% CI [−0.162, −0.002]), which was consistent with our hypothesis. The interaction EA × ESE × Income had a positive coefficient and was marginally significant at the 0.10 level (β = 0.025, 95% CI [−0.003, 0.054], 90% CI [0.001, 0.050]), suggesting that individuals with both high EA and ESE were more likely to be self-employed in high-income households.

We noted that WFC and FWC had opposite contingency effects on self-employment, which might reflect two different entrepreneurial motivations. On the one hand, in the scenario of high WFC, individuals with high EA and ESE traits were more likely to choose to start their own businesses due to the need for temporal autonomy. On the other hand, in the scenario of high FWC, individuals with high EA and ESE traits were more likely to be attracted to intrapreneurship. In our opinion, neither of these scenarios actually violated the assumption of the COR theory that individuals would strive for more resources on the premise of avoiding resource losses.

General discussion

Theoretical contribution

Based on theories of entrepreneurial action and conservation of resources, this paper explores the individual traits and family contingency antecedents of entrepreneurial choice and makes the following contributions to the literature:

First, in a more inclusive entrepreneurial framework that includes intrapreneurship and self-employment, we re-examined the impact of entrepreneurial alertness and entrepreneurial self-efficacy on individual entrepreneurial choice. On the one hand, we contribute two important antecedents for intrapreneurial behaviour, and on the other hand, we deepen a more nuanced understanding of the interaction between alertness to opportunity and self-efficacy in entrepreneurship. Specifically, in the field of intrapreneurship, although prior literature has preliminarily sorted out the characteristics of intrapreneurs based on theories of job demands–resources (Gawke et al., 2017) and planned behaviour (Chouchane et al., 2023), the contribution is still relatively scattered. Is there a similarity or difference between the impact of entrepreneurial cognitive traits on intrapreneurship and self-employment? The literature does not provide a satisfactory answer. In our research framework, we propose that EA and ESE still have predictive effects on intrapreneurial engagement, exhibiting similar effects as on self-employment. Correspondingly, however, if individuals possess both high EA and ESE traits, they are more likely to choose self-employment rather than intrapreneurship, thus exhibiting different outcomes. Here, consistent with the recommendations of social cognitive theory, we aim to explore interactions, but in addition to the interaction between cognitive traits and the environment, we discover the interaction between cognitive traits, which is also markedly distinct from the literature focused on exploring causal relationships between traits (Tang et al., 2023; Araujo et al., 2023). Therefore, by combining theories of entrepreneurial action and COR, we go beyond the traditional social cognitive framework to understand the relationship between entrepreneurial alertness, self-efficacy and behaviour.

Second, the discussion of intrapreneurship in this paper also contributes to the literature on the entrepreneurial process. Entrepreneurial action theory suggests that entrepreneurial action occurs when a third-person opportunity transforms into a first-person opportunity or when a third-person opportunity matches a first-person opportunity (McMullen and Shepherd, 2006; Tang et al., 2012; Levasseur et al., 2022). From an intrapreneurial perspective, we provide a new mechanism for how these two types of opportunities fit together (or, more appropriately, how they connect). Specifically, the intrapreneurial perspective allows us to look at entrepreneurial individuals and established organisations together, and a third-person opportunity for an individual may also be a first-person opportunity for organisations, and that’s when intrapreneurship occurs. Meanwhile, entrepreneurial action theory focuses more on understanding how individuals evaluate opportunities from a perspective of uncertainty, while this paper emphasises the role of self-efficacy. We suggest that entrepreneurial action depends not only on individuals’ assessment of their willingness to tolerate risks and uncertainty but also on their perceived self-efficacy.

Third, we found the contingency impact of family factors on individual entrepreneurial choice. Based on family embeddedness and COR perspective, we argue that family factors can moderate the impact of EA and ESE on entrepreneurial choice. Our theory and empirical evidence also indicated that FWC would lead individuals with entrepreneurial traits to turn to the organisations and engage in intrapreneurship, and that WFC, as well as household income, would guide them to start their own businesses. On the one hand, these results highlighted the important role of family context in understanding individual entrepreneurial choice, and on the other hand, they also implied the subtle influence of different types of work–family conflicts on individual career decision-making and time and energy allocation. As suggested by Greenhaus and Beutell (1985), work–family conflict is non-directional in nature and can only be directed when the individual decides to resolve the conflict. When individuals make an entrepreneurial choice, actually, they have a willingness to resolve this conflict. Thus, while contributing knowledge to the study of entrepreneurship, especially intrapreneurship, this paper also contributes insights to the literature on family embeddedness and work–family conflict.

Practical implications

This paper has implications for business organisations. If an organisation decides to implement an intrapreneurship strategy, according to our framework, it needs to guide employees’ alertness towards intrapreneurship and improve their self-efficacy. In recruitment and selection, employers should also pay more attention to the assessment of candidates’ entrepreneurial experiences and abilities. Despite the literature suggesting that recruiting for intrapreneurship does not appear to be a good strategy (Ng and Sherman, 2022), for those who do not have high entrepreneurial alertness but outstanding abilities, however, they are more likely to become excellent intrapreneurs by providing financial and intrinsic rewards. Again, employers should not ignore employees’ family-embedded backgrounds. We suggest that family factors are closely related to employees’ intrapreneurial decision-making, so employers need to give employees certain freedom and enough material incentives to balance the relationship between intrapreneurship and family and alleviate their worries.

Individuals who have plans to start a business will benefit from this paper. As suggested by Yang and Kacperczyk (2024), intrapreneurship shows greater inclusivity. By comparing the effects of individual traits and family contingencies on intrapreneurship and self-employment, we actually point out that intrapreneurship is a new entrepreneurial model that is different from traditional self-employment. This is reflected in the fact that compared with the self-employed, intrapreneurs have lower entrepreneurial alertness and self-efficacy. Therefore, intrapreneurship is an ideal career choice for people who are less sensitive to business opportunities but have higher abilities and skills—such as some R&D staff or those who have recently experienced entrepreneurial failure. Further, for these individuals, if they face high levels of work–family conflicts or have limited household wealth, intrapreneurship may be more attractive than self-employment outside organisations.

Limitations and future research

This paper has some limitations. First, in Study 1, the measurement of key variables, such as entrepreneurial alertness and self-efficacy, was limited by the database. Although we had largely overcome this challenge through a replication questionnaire survey, we encourage more researchers to participate in it. It is reminded that some popular scales overlap in the measurement of EA and ESE to a certain extent, so these scales need to be used with caution. In addition, we also recommend studying the impact of other socio-cognitive traits, such as risk preference and fear of failure, on entrepreneurial choice. Second, CMB may affect some of the conclusions of this paper. While we focus primarily on interactions and moderating effects, and in Study 2, we attempted to address this issue by collecting data from multiple sites and balancing questions, this did not completely dispel concerns as we still relied on self-reported cross-sectional data. The effects of EA and ESE on entrepreneurial choice were particularly threatened by bias and reverse causality, so a relatively conservative approach should be taken toward the relevant results. Third, our findings indicated that role theory was well suited to guide future research, and therefore we suggest further exploring the mechanisms by which (expected) work–family conflict affects entrepreneurial or career decision-making, how individual work–family conflict changes before and after entrepreneurial actions, and the role of gender in it. In fact, we notice that some scholars propose new constructs, such as work-to-venture conflict, based on role theory (Carr et al., 2023). We also note that it is useful to distinguish between WFC and FWC in the field of entrepreneurship, which also has implications for future research. Finally, although we focus on intrapreneurship, it is recommended that future research explore entrepreneurial choice and entrepreneurial process in a framework that integrates intrapreneurship, hybrid entrepreneurship and self-employment.

Conclusion

Based on theories of entrepreneurial action and conservation of resources, we explore the relationship among individual socio-cognitive traits, family contingencies and entrepreneurial choice and advance the literature on intrapreneurship and self-employment. To be specific, we argue that individual EA and ESE have a greater positive impact on self-employment than entrepreneurship, respectively, while their interaction has a positive effect on the former but a negative effect on the latter. A high level of FWC not only increases the likelihood of individuals with high EA and ESE engaging in intrapreneurship but also reduces the likelihood of self-employment. The role of household income is the opposite. By using secondary data and conducting an extended questionnaire survey, we find general evidence to support our notions.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analysed in Study 1 are available from the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (https://www.gemconsortium.org/data), the World Bank (https://databank.worldbank.org/) and the International Labour Organization websites (https://ilostat.ilo.org/data/). The dataset generated and analysed in Study 2 is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Adachi T, Hisada T (2017) Gender differences in entrepreneurship and intrapreneurship: an empirical analysis. Small Bus Econ 48(3):447–486. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-016-9793-y

Aldrich HE, Cliff JE (2003) The pervasive effects of family on entrepreneurship: toward a family embeddedness perspective. J Bus Ventur 18(5):573–596. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-9026(03)00011-9

Allen T, Herst D, Bruck C, Sutton M (2000) Consequences associated with work-to-family conflict: a review and agenda for future research. J Occup Health Psychol 5(2):278–308. https://doi.org/10.1037/1076-8998.5.2.278

Antoncic B (2007) Intrapreneurship: a comparative structural equation modeling study. Ind Manag Data Syst 107(3):309–325. https://doi.org/10.1108/02635570710734244

Araujo CF, Karami M, Tang J, Roldan LB, dos Santos JA (2023) Entrepreneurial alertness: a meta-analysis and empirical review. J Bus Ventur Insights 19:e00394. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbvi.2023.e00394

Ardichvili A, Cardozo R, Ray S (2003) A theory of entrepreneurial opportunity identification and development. J Bus Ventur 18(1):105–123. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-9026(01)00068-4

Arentz J, Sautet F, Storr V (2013) Prior-knowledge and opportunity identification. Small Bus Econ 41(2):461–478. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-012-9437-9

Badoiu G-A, Segarra-Ciprés M, Escrig-Tena AB (2020) Understanding employees’ intrapreneurial behavior: a case study. Pers Rev 49(8):1677–1694. https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-04-2019-0201

Bandura A (1989) Human agency in social cognitive theory. Am Psychol 44(9):1175–1184. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.44.9.1175

Blanka C (2019) An individual-level perspective on intrapreneurship: a review and ways forward. Rev Manag Sci 13(5):919–961. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-018-0277-0

Boudreaux CJ, Nikolaev BN, Klein P (2019) Socio-cognitive traits and entrepreneurship: the moderating role of economic institutions. J Bus Ventur 34(1):178–196. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2018.08.003

Boudreaux CJ, Bennett DL, Lucas DS, Nikolaev BN (2023) Taking mental models seriously: institutions, entrepreneurship, and the mediating role of socio-cognitive traits. Small Bus Econ 61(2):465–493. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-022-00712-8

Brislin RW (1970) Back-translation for cross-cultural research. J Cross-Cult Psychol 1(3):185–216. https://doi.org/10.1177/135910457000100301

Burton MD, Sørensen JB, Dobrev SD (2016) A careers perspective on entrepreneurship. Entrep Theory Pract 40(2):237–247. https://doi.org/10.1111/etap.12230

Camelo-Ordaz C, Fernández-Alles M, Ruiz-Navarro J, Sousa-Ginel E (2012) The intrapreneur and innovation in creative firms. Int Small Bus J 30(5):513–535. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242610385396

Carr JC, Marshall DR, Michaelis TL, Pollack JM, Sheats L (2023) The role of work-to-venture role conflict on hybrid entrepreneurs’ transition into entrepreneurship. J Small Bus Manag 61(5):2302–2325. https://doi.org/10.1080/00472778.2022.2082455

Chen CC, Greene PG, Crick A (1998) Does entrepreneurial self-efficacy distinguish entrepreneurs from managers? J Bus Ventur 13(4):295–316. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-9026(97)00029-3

Chen S, Cheng M-I (2023) The influence of household size on the experience of work–family conflict. SN Soc Sci 3(9):150. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43545-023-00744-1

Chiang T-F, Xiao JJ (2017) Household characteristics and the change of financial risk tolerance during the financial crisis in the United States. Int J Consum Stud 41(5):484–493. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcs.12356

Chouchane R, Fernet C, Austin S, Zouaoui SK (2023) Organizational support and intrapreneurial behavior: on the role of employees’ intrapreneurial intention and self-efficacy. J Manag Organ 29(2):366–382. https://doi.org/10.1017/jmo.2021.14

Chua JH, Chrisman JJ, Kellermanns F, Wu Z (2011) Family involvement and new venture debt financing. J Bus Ventur 26(4):472–488. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2009.11.002

Dawson JF (2014) Moderation in management research: what, why, when, and how. J Bus Psychol 29(1):1–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-013-9308-7

Dawson JF, Richter AW (2006) Probing three-way interactions in moderated multiple regression: development and application of a slope difference test. J Appl Psychol 91(4):917–926. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.91.4.917

de Jong JPJ, Parker SK, Wennekers S, Wu C (2015) Entrepreneurial behavior in organizations: does job design matter? Entrep Theory Pract 39(4):981–995. https://doi.org/10.1111/etap.12084

del Olmo-García F, Crecente-Romero FJ, del Val-Núñez MT, Sarabia-Alegría M (2023) Entrepreneurial activity in an environment of digital transformation: an analysis of relevant factors in the euro area. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 10:755. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-02270-0

Deprez J, Peeters ER, Gorgievski MJ (2021) Developing intrapreneurial self-efficacy through internships? Investigating agency and structure factors. Int J Entrep Behav Res 27(5):1166–1188. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEBR-09-2020-0642

Douglas EJ, Fitzsimmons JR (2013) Intrapreneurial intentions versus entrepreneurial intentions: distinct constructs with different antecedents. Small Bus Econ 41(1):115–132. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-012-9419-y

Douglas EJ, Shepherd DA, Venugopal V (2021) A multi-motivational general model of entrepreneurial intention. J Bus Ventur 36(4):106107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2021.106107

Dyer WG, Nenque E, Hill EJ (2014) Toward a theory of family capital and entrepreneurship: antecedents and outcomes. J Small Bus Manag 52(2):266–285. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsbm.12097

Edelman LF, Manolova T, Shirokova G, Tsukanova T (2016) The impact of family support on young entrepreneurs’ start-up activities. J Bus Ventur 31(4):428–448. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2016.04.003

Elert N, Stenkula M (2022) Intrapreneurship: productive and non-productive. Entrep Theory Pract 46(5):1423–1439. https://doi.org/10.1177/1042258720964181

Gawke JC, Gorgievski MJ, Bakker AB (2017) Employee intrapreneurship and work engagement: a latent change score approach. J Vocat Behav 100:88–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2017.03.002

Gawke JC, Gorgievski MJ, Bakker AB (2018) Personal costs and benefits of employee intrapreneurship: disentangling the employee intrapreneurship, well-being, and job performance relationship. J Occup Health Psychol 23(4):508–519. https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000105

Gawke JC, Gorgievski MJ, Bakker AB (2019) Measuring intrapreneurship at the individual level: development and validation of the Employee Intrapreneurship Scale (EIS). Eur Manag J 37(6):806–817. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2019.03.001

Gorgievski MJ, Bakker AB, Petrou P, Gawke JC (2023) Antecedents of employee intrapreneurship in the public sector: a proactive motivation approach. Int Public Manag J 26(6):852–873. https://doi.org/10.1080/10967494.2023.2255172

Grant-Vallone EJ, Donaldson SI (2001) Consequences of work–family conflict on employee well-being over time. Work Stress 15(3):214–226. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678370110066544

Grawitch MJ, Barber LK, Justice L (2010) Rethinking the work-life interface: it’s not about balance, it’s about resource allocation. Appl Psychol Health Well-Being 2(2):127–159. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1758-0854.2009.01023.x

Greenhaus JH, Beutell NJ (1985) Sources of conflict between work and family roles. Acad Manag Rev 10(1):76–88. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1985.4277352

Halbesleben JRB, Neveu J-P, Paustian-Underdahl SC, Westman M (2014) Getting to the “COR”: understanding the role of resources in conservation of resources theory. J Manag 40(5):1334–1364. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206314527130

Hisrich RD (1990) Entrepreneurship/intrapreneurship. Am Psychol 45(2):209–222. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.45.2.209

Hobfoll SE, Halbesleben J, Neveu JP, Westman M (2018) Conservation of resources in the organizational context: the reality of resources and their consequences. Annu Rev Organ Psychol Organ Behav 5:103–128. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-032117-104640

Hoetker G (2007) The use of logit and probit models in strategic management research: critical issues. Strateg Manag J 28(4):331–343. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.582

Hsu DK, Wiklund J, Cotton RD (2017) Success, failure, and entrepreneurial reentry: an experimental assessment of the veracity of self-efficacy and prospect theory. Entrep Theory Pract 41(1):19–47. https://doi.org/10.1111/etap.12166

Huang Y, Wu S, Chen C, Zou C (2024) Household and entrepreneurial entry: an individual entrepreneurial capital perspective. Balt J Manag 19(2):253–269. https://doi.org/10.1108/BJM-08-2023-0319

Kaul A, Ganco M, Raffiee J (2024) When subjective judgments lead to spinouts: employee entrepreneurship under uncertainty, firm-specificity, and appropriability. Acad Manag Rev 49(2):215–248. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2020.0113

Kwon S-W, Adler PS (2014) Social capital: maturation of a field of research. Acad Manag Rev 39(4):412–422. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2014.0210

Lanivich SE (2015) The RICH entrepreneur: using conservation of resources theory in contexts of uncertainty. Entrep Theory Pract 39(4):863–894. https://doi.org/10.1111/etap.12082

Lanivich SE, Smith A, Levasseur L, Pidduck RJ, Busenitz L, Tang J (2022) Advancing entrepreneurial alertness: review, synthesis, and future research directions. J Bus Res 139:1165–1176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.10.023

Levasseur L, Tang J, Karami M, Busenitz L, Kacmar KM (2022) Increasing alertness to new opportunities: the influence of positive affect and implications for innovation. Asia Pac J Manag 39(1):27–49. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10490-020-09724-y

Li W, Chen W, Pang Q, Song J (2023) How to mitigate the inhibitory effect of organizational inertia on corporate digital entrepreneurship? Front Psychol 14:1130801. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1130801

Martín-Rojas R, García-Morales VJ, Bolívar-Ramos MT (2013) Influence of technological support, skills and competencies, and learning on corporate entrepreneurship in European technology firms. Technovation 33(12):417–430. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2013.08.002

Marx M, Strumsky D, Fleming L (2009) Mobility, skills, and the Michigan non-compete experiment. Manag Sci 55(6):875–889. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.1080.0985

Masuda AD, Sortheix FM, Beham B, Naidoo LJ (2019) Cultural value orientations and work–family conflict: the mediating role of work and family demands. J Vocat Behav 112:294–310. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2019.04.001

McMullen JS, Shepherd DA (2006) Entrepreneurial action and the role of uncertainty in the theory of the entrepreneur. Acad Manag Rev 31(1):132–152. https://doi.org/10.2307/20159189

Menzel HC, Aaltio I, Ulijn JM (2007) On the way to creativity: engineers as intrapreneurs in organizations. Technovation 27(12):732–743. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2007.05.004

Monsen E, Patzelt H, Saxton T (2010) Beyond simple utility: incentive design and trade–offs for corporate employee–entrepreneurs. Entrep Theory Pract 34(1):105–130. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2009.00314.x

Mustillo SA, Lizardo OA, McVeigh RM (2018) Editors’ comment: a few guidelines for quantitative submissions. Am Sociol Rev 83(6):1281–1283. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122418806282

Neessen PCM, Caniëls MCJ, Vos B, de Jong JP (2019) The intrapreneurial employee: toward an integrated model of intrapreneurship and research agenda. Int Entrep Manag J 15(2):545–571. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-018-0552-1

Neneh BN (2019) From entrepreneurial intentions to behavior: the role of anticipated regret and proactive personality. J Vocat Behav 112:311–324. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2019.04.005

Netemeyer RG, Boles JS, McMurrian R (1996) Development and validation of work–family conflict and family–work conflict scales. J Appl Psychol 81(4):400–410. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.81.4.400

Ng W, Sherman EL (2022) In search of inspiration: external mobility and the emergence of technology intrapreneurs. Organ Sci 33(6):2300–2321. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.2021.1530

Niemann CC, Mai R, Dickel P (2022) Nurture or nature? How organizational and individual factors drive corporate entrepreneurial projects. J Bus Res 140:155–169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.11.065

Parker SC (2011) Intrapreneurship or entrepreneurship? J Bus Ventur 26(1):19–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2009.07.003

Pinchot G (1985) Intrapreneuring: why you don’t have to leave the corporation to become an entrepreneur. Harper & Row, New York

Pissarides F (1999) Is lack of funds the main obstacle to growth? EBRD’s experience with small- and medium-sized businesses in central and eastern Europe. J Bus Ventur 14(5):519–539. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-9026(98)00027-5

Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Lee J-Y, Podsakoff NP (2003) Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J Appl Psychol 88(5):879–903. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

Rabl T, Petzsche V, Baum M, Franzke S (2023) Can support by digital technologies stimulate intrapreneurial behaviour? The moderating role of management support for innovation and intrapreneurial self-efficacy. Inf Syst J 33(3):567–597. https://doi.org/10.1111/isj.12413

Raffiee J, Feng J (2014) Should I quit my day job?: a hybrid path to entrepreneurship. Acad Manag J 57(4):936–963. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2012.0522

Reibenspiess V, Drechsler K, Eckhardt A, Wagner H-T (2022) Tapping into the wealth of employees’ ideas: design principles for a digital intrapreneurship platform. Inf Manag 59(3):103287. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2020.103287

Ronstadt R, Vesper KH, McMullan WE (1988) Entrepreneurship: today courses, tomorrow degrees? Entrep Theory Pract 13(1):7–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/104225878801300102

Ruef M (2020) The household as a source of labor for entrepreneurs: evidence from New York City during industrialization. Strateg Entrep J 14(1):20–42. https://doi.org/10.1002/sej.1309

Schade P, Schuhmacher MC (2022) Digital infrastructure and entrepreneurial action-formation: a multilevel study. J Bus Ventur 37(5):106232. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2022.106232

Schjoedt L, Craig JB (2017) Development and validation of a unidimensional domain-specific entrepreneurial self-efficacy scale. Int J Entrep Behav Res 23(1):98–113. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEBR-11-2015-0251

Shahriar AZM (2018) Gender differences in entrepreneurial propensity: evidence from matrilineal and patriarchal societies. J Bus Ventur 33(6):762–779. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2018.04.005

Shinnar RS, Hsu DK, Powell BC, Zhou H (2018) Entrepreneurial intentions and start-ups: are women or men more likely to enact their intentions? Int Small Bus J 36(1):60–80. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242617704277

Sieger P, Minola T (2017) The family’s financial support as a “poisoned gift”: a family embeddedness perspective on entrepreneurial intentions. J Small Bus Manag 55(S1):179–204. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsbm.12273

Sørensen JB (2007) Bureaucracy and entrepreneurship: workplace effects on entrepreneurial entry. Adm Sci Q 52(3):387–412. https://doi.org/10.2189/asqu.52.3.387

Sørensen JB, Fassiotto MA (2011) Organizations as fonts of entrepreneurship. Organ Sci 22(5):1322–1331. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1100.0622

Steier L (2003) Variants of agency contracts in family-financed ventures as a continuum of familial altruistic and market rationalities. J Bus Ventur 18(5):597–618. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-9026(03)00012-0

Stephan U (2018) Entrepreneurs’ mental health and well-being: a review and research agenda. Acad Manag Perspect 32(3):290–322. https://doi.org/10.5465/amp.2017.0001

Su Y, Zahra SA, Fan D (2022) Stratification, entrepreneurial choice and income growth: the moderating role of subnational marketization in an emerging economy. Entrep Theory Pract 46(6):1597–1625. https://doi.org/10.1177/1042258721998942

Sun J, Huang Y, Su D, Yang C (2020) Data mining and analysis of part-time entrepreneurs from the perspective of entrepreneurial ability. Inf Syst E-Bus Manag 18(3):455–484. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10257-019-00425-8

Tang J, Baron RA, Yu A (2023) Entrepreneurial alertness: exploring its psychological antecedents and effects on firm outcomes. J Small Bus Manag 61(6):2879–2908. https://doi.org/10.1080/00472778.2021.1945071

Tang J, Kacmar KM, Busenitz L (2012) Entrepreneurial alertness in the pursuit of new opportunities. J Bus Ventur 27(1):77–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2010.07.001

Tang J, Yang J, Ye W, Khan SA (2021) Now is the time: the effects of linguistic time reference and national time orientation on innovative new ventures. J Bus Ventur 36(5):106142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2021.106142

Townsend DM, Hunt RA, McMullen JS, Sarasvathy SD (2018) Uncertainty, knowledge problems, and entrepreneurial action. Acad Manag Ann 12(2):659–687. https://doi.org/10.5465/annals.2016.0109

Urban B, Nikolov K (2014) Sustainable corporate entrepreneurship initiatives: a risk and reward analysis. Technol Econ Dev Econ 19(S1):S383–S408. https://doi.org/10.3846/20294913.2013.879749

Urbano D, Orozco J, Turro A (2024) The effect of institutions on intrapreneurship: an analysis of developed vs developing countries. J Small Bus Manag 62(3):1107–1147. https://doi.org/10.1080/00472778.2022.2161556

Urbig D, Reif K, Lengsfeld S, Procher VD (2021) Promoting or preventing entrepreneurship? Employers’ perceptions of and reactions to employees’ entrepreneurial side jobs. Technol Forecast Soc Chang 172:121032. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2021.121032

Xu F, Kellermanns FW, Jin L, Xi J (2020) Family support as social exchange in entrepreneurship: its moderating impact on entrepreneurial stressors-well-being relationships. J Bus Res 120:59–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.07.033