Abstract

This study attempts to explore the relationship between the two mediator variables effective learning engagement and educational social media (SM) usage and the study’s outcome measures, which include student satisfaction and learning performance. The distribution of a self-determination theory questionnaire with external factors to 293 university students served as the primary data collection method. King Saud University used a poll to personally collect data. Partial least squares structural equation modeling was then used to examine the data and assess the model in Smart-PLS. Students’ academic success and contentment at colleges and universities seem to be positively correlated, and their active involvement in learning activities and educational use of SM. It was shown that important factors influencing affective learning participation and the instructional use of SM for teaching and learning include perceived competence, perceived autonomy, perceived relatedness, information sharing, and collaborative learning environments. It was discovered that these connections were important. The self-determination theory provided confirmation that this model is appropriate for fostering students’ feelings of competence, autonomy, and relatedness in order to increase their affective learning involvement. This, in turn, improves students’ satisfaction and achievement in higher education.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Introduction

Numerous academics are examining students’ desire to participate in social media (SM) tools and the impact of their use on the educational environment due to the growing popularity of SM and the extensive use of these tools by students in their daily lives. Teachers are keen to grasp the educational importance of SM, even though researchers are still in the investigative stage, trying to gather definitive information about whether or not using SM platforms is suitable (Al-Adwan et al., 2021; Al-Rahmi et al., 2022a). Nonetheless, earlier studies in the literature (Sabah, 2022) mainly examined the causes of SM tool acceptance or use and the ways in which important elements influence this kind of educational usage (Sayaf et al., 2022; Ullah et al., 2021). Educational SM use is the deliberate integration of SM platforms and tools into the classroom to enhance the overall pedagogical experience. This approach considers the contemporary digital landscape and leverages the SM platform’s communicative and collaborative potential to foster students’ active learning, engagement, and knowledge (Al-Rahmi et al., 2022b; Yin & Yuan, 2021). Websites like blogs, wikis, discussion forums, and microblogging sites can be used to promote student participation, peer learning, and cooperative projects (Sayaf et al., 2022). Nevertheless, despite the potential benefits of SM use in education, a number of considerations need to be made carefully, including fostering a supportive learning environment and privacy issues (Sayaf et al., 2022). Most SM research in Saudi Arabia has concentrated on the motivations behind and actions connected to SM use.

According to Yin and Yuan (2021) and Sabah (2022), students’ attitudes toward using SM in a blended learning environment, like Facebook and WhatsApp, as well as their acceptance of using SM for educational purposes, have all been investigated through experimental research in a few studies. Additionally, Facebook and Twitter have been used to support student-centered learning. Previous studies have examined the role that cultural norms play in preserving social relationships on Facebook as well as the risks that excessive Facebook use poses to students’ mental health (Remedios et al., 2017). Furthermore, investigations into the potential educational benefits of SM platforms are still underway; numerous studies have evaluated the extent to which SM usage enhances learning (Hameed et al., 2022; Nti et al., 2022). However, because these studies ignored the particular correlations between the use of SM and learning outcomes, they were unable to deepen our understanding of these explanatory relationships. As a result, the prior literature found inconsistent findings about these platforms’ ability to improve students’ learning outcomes. A few of these studies (Alhussain et al., 2020), for example, found that using SM enhanced students’ academic achievement. However, other research has shown that SM use has a negative impact on academic performance (Al-Maatouk et al., 2020) and that students’ use of SM reduces their study time and effort. It’s noteworthy that other research has revealed SM platforms might not be advantageous for students.

According to them, these platforms have little to no impact on academic achievement (Al-Rahmi et al., 2022c) and are improper for improving learning performance (Foroughi et al., 2022). The majority of this study (Alamri et al., 2020b) has not taken into consideration the important function that mediator variables play in examining the relationship between the use of SM and satisfaction as well as learning outcomes. Few studies have explicitly examined the moderator factor (such as cyberstalking) that affects the association between academic performance and SM use (Al-Rahmi et al., 2022d), and how, while using SM for learning, cyberbullying plays a moderating effect in the relationship between academic accomplishment and cooperative learning in higher education (Alyoussef et al., 2019). Understanding how and when SM use might increase or decrease results requires a sophisticated viewpoint because there are more complex links between SM use and its outcomes than merely a positive or negative influence. Actually, learning’s ability to make knowledge widely available, accessible, and flexible is what really distinguishes it from other conventional kinds of education (Han & Shin, 2016).

Because of these benefits, SM has drawn a sizable initial user base, particularly in the setting of higher education. In fact, because they typically possess their own mobile devices, college learners are more likely to accept and employ SM learning than students in a classroom (Al-Qaysi et al., 2021). Nevertheless, attracting the initial user base is just half the battle for the success of SM sites. How to retain students using SM is a crucial question that many educators and providers of SM technology are posing (Chawinga, 2017). While a lot of scholarly research has been done on the acceptance and use of mobile learning, most of these studies have identified the factors that led to its development from a technological standpoint (Pham & Dau, 2022). Perceived utility, effort expectations, and performance expectations are some of the factors that affect the early uptake of SM use in higher education (Chugh et al., 2021).

It has been demonstrated that increased well-being and intrinsic motivation are significantly impacted by the fulfillment of the three general psychological aims of SDT—autonomy, competence, and relatedness (Ryan & Deci, 2000). Garn defines relatedness as the need to feel socially connected in a classroom environment, competence as the process of growing one’s own abilities and skills, and autonomy as the basic need to regulate one’s behavior and organize oneself according to one’s self-awareness (Garn et al., 2019). SDT is applied in a variety of settings, including the commercial world, the workplace, and educational institutions. According to Sun et al. (2019), it is regarded as one of the “most supported by evidence incentive theories” in use today. SDT has several uses in the field of research in education as well. The goal of SDT, a macro-level theory concerning human incentive, is to make clear the relationships that exist between motivation, growth, and well-being.

It emphasizes how important fundamental psychological requirements like relatedness, competence, and autonomy have been. The application of SDT in virtual learning environments has been the subject of numerous research investigations. According to Hsu et al.‘s 2019 study, for instance, satisfying basic mental needs enhanced self-regulated learning, which in turn was associated with higher reported knowledge transfer and greater course-end accomplishment. The significance of students’ continuous self-regulation for effective learning in an online setting was the subject of another study conducted in 2021. It achieved this by explaining the connections between students’ motivation, fundamental psychological requirements, and ongoing desire to participate in online self-regulated learning using SDT (Luo et al., 2021). Thus, by applying the SDT principles to create online learning that supports students’ autonomy, competence, and relatedness, educators can improve students’ motivation and learning outcomes through the use of SM (Chiu, 2023; Al-Rahmi et al., 2022d).

SDT can conduct additional studies on SM platforms by examining how intrinsic motivation as well as conduct during learning are influenced by the three fundamental psychological requirements of independence, skill, and connection (Sun et al., 2019). Researchers utilizing SDT also looked at how learner motivation, success, and well-being were affected by mobile learning tools (Jeno et al., 2019). As learners themselves, teachers make use of a range of educational resources. SDT (Jansen in de Wal et al., 2020) states that when a person’s basic psychological needs are met, learning actions and goals also become more obvious.

Early studies on SM and education have shown how important trust and the kind of organization are in fostering knowledge sharing (Singh et al., 2019; Ahmad & Huvila, 2019). Mutambik et al. (2022) state that people regard collaborative learning highly. SM’s function in promoting education and information sharing still has advantages and disadvantages because there is a lack of research demonstrating how SM affects information sharing in the field of education. Though self-determination theory (SDT) with affective learning involvement and educational usage of SM factors (Platts, 1972; Sørebø et al., 2009) can be used to study the basic processes by which student motivation to learn develops and how they affect SM tools, very little research has been done on these topics, especially in the post-adoption phase (Nti et al., 2022).

SM in higher education

Lately, lifelong learning in terms of skills has taken precedence over knowledge in higher education (Abdullah Moafa et al., 2018).

Cooperation abilities are highly valued by employers, which is how they are in this compilation (Raza et al., 2020). Considering the broad meaning of “SM,” it is not surprising that most research has focused on websites such as Facebook, Twitter, and MySpace as educational successes. As stated by Alisaiel et al. (2022c), the broadest definition of active collaborative learning is when two or more people collaborate to study or attempt to learn new. According to Stockdale and Coyne (2020), SM websites aim to facilitate various tasks for their users, such as sending and receiving emails, adding friends, creating personal profiles, joining groups, creating apps, and finding other users.

Compared to Web 1.0, which was less active and more static, Web 2.0 allows for greater user engagement, collaboration, and personalization (Tajvidi & Karami, 2021). It combines active collaborative learning with the use of Facebook, blogs, and YouTube, amongst other platforms, as noted in Al-Rahmi et al. (2021a).

Furthermore, it has historically been challenging for faculty personnel in higher education to communicate with students effectively (Alenazy et al., 2019). They have access to SM technologies, which makes it possible to communicate with students quickly and create more engaging lessons. SM is used by students to raise their academic standing. Teachers and students can both use social networks to improve and expedite the teaching and learning process.

King Saud University medical students stated that they used SM for academic studies much less frequently (40%) but that their primary objectives were enjoyment (95.8%), keeping up with the news (88.3%), and socializing (85.5%) (Lahiry et al., 2019). A different study found that students with lower GPAs use Facebook more normally than their higher-achieving peers. They explained this by filling out that students often use Facebook as a way to divert attention away from social or academic issues they are having (Michikyan et al., 2015).

The impact of SM on students’ academic achievement is a controversial subject. For college students, there have supposedly been conflicting results. Therefore, generalizations on the impact of SM are untrue (Lepp et al., 2014). It’s noteworthy to note that more than half of students admitted the negative effects that excessive social media use had on both their personal and academic lives (64.6.1%) and students (77.1%). Of them, 69% claimed that social media prevented them from attending classes. Parallel to this, Able to Encourage (Alwagait et al., 2015) examined how SM affected the academic achievement of 108 Saudi students. According to 60% of individuals, using social media excessively interfered with their capacity to function (Sarfraz et al., 2022). An additional survey included university students in Ghana who said WhatsApp negatively affected their academic performance. They blamed it on their inability to focus in class and their difficulty juggling their online activities with their homework responsibilities (Sarfraz et al., 2022).

However, some studies (Alturki & Aldraiweesh, 2022; Capriotti & Zeler, 2023) discovered that SM might be used as an instructional tool to promote communication, facilitate cooperative learning, and boost student engagement (Al-Rahmi et al., 2022c). Through this study, we hope to close a knowledge gap in the literature and provide further insight into the connections between students’ satisfaction with their academic progress and their use of SM.

The current study intends to investigate the moderating effects of affective learning involvement and instructive SM use to facilitate concurrently the students’ satisfaction and learning performance, which were measured by the students’ approval and learning performance, in order to address the aforementioned limitations. This investigation, therefore, has two goals. The first objective is to evaluate the impact of SM use as a teaching tool on students’ enactment and satisfaction.

The second objective is to assess how the connection between student happiness and academic success is influenced by specific mediator characteristics, such as the use of educational SM and emotional learning engagement. Consequently, this study tackles the following essential research questions:

What effects on learning and usage of SM platforms for education do academic students’ needs for SM-used autonomy (perceived competence, perceived autonomy, and perceived relatedness) have? When SM and affective learning engagement are employed as instructional strategies in the classroom, do students’ happiness and academic achievement increase?

Development of research models and hypotheses

Six mini-theories make up the SDT, a larger framework of human inspiration and well-being that explains the connection between motivation and fundamental psychological needs (Ryan & Deci, 2000). One of these is the SDT’s Basic Psychological Needs Theory, which promotes motivation and well-being (Ryan & Deci, 2000). It has been demonstrated that increased well-being and intrinsic motivation are significantly impacted by the fulfillment of the three general psychological aims of SDT—autonomy, competence, and relatedness (Ryan & Deci, 2000). The use of SM tools in education has theoretical ramifications for technology, society, behavior, and education. Learning outcomes during the COVID-19 pandemic, pupil involvement, perceived value, perceived simplicity of use, perceived enjoyment, perception of using SM, intention of behavior to use SM, and using SM for collaborative education are just a few of the variables that were used in the study conducted in Saudi Arabia that is reported by Alismaiel et al. (2022b).

Concentrated on various elements that influence students’ learning outcomes and satisfaction, including information sharing, a collaborative learning environment, affective learning involvement, perceived competence, perceived autonomy, perceived relatedness, and the use of SM in education. Furthermore, a study carried out in Malaysia (Al-Rahmi et al., 2022a) used some elements from the previous research, including student satisfaction and collaborative learning, but not all of the elements. Furthermore, a study conducted in Saudi Arabia by Alturki and Aldraiweesh (2022) used a number of variables, such as task-technology fit, perceived utility, perceived ease of use, behavioral intention to use, and actual use of mobile M-learning. On the other hand, concentrated on various elements that influence students’ learning outcomes and satisfaction, including information sharing, a cooperative learning environment, affective learning involvement, perceived competence, perceived autonomy, perceived relatedness, and the use of SM in education. Consequently, Yildiz Durak (2019) made use of a Turkish study. Social impact, performance expectations, effort expectations, behavior to utilize these devices, and actual use were some of the factors used in this study.

Moreover, concentrated on various elements that influence students’ learning outcomes and satisfaction, including information sharing, a collaborative learning environment, affective learning involvement, perceived competence, perceived autonomy, perceived relatedness, and the use of SM in education. Last but not least, a study conducted in Greece (Troussas et al., 2021) used a number of variables, such as social features, social gamification, perceived utility, usage of social networks, perceived ease of use, attitude toward utilizing social networks, and intention to use. Furthermore, concentrated on various elements that influence students’ learning outcomes and satisfaction, including information sharing, a collaborative learning environment, affective learning involvement, perceived competence, perceived autonomy, perceived relatedness, and the use of SM in education.

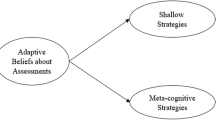

The research model incorporates exogenous variables of educational use of SM platforms that support endogenous variables of student satisfaction and learning performance impact, as well as mediator variables of affective learning involvement and educational use of SM, as illustrated in Fig. 1. We developed a model (Fig. 1) to better understand how the educational use of SM at King Saud University in Saudi higher education influences the collaborative learning environment, knowledge sharing, affective learning participation, and educational usage of SM. The association between students’ academic achievement, level of satisfaction with their education, and affective engagement when using SM for learning is depicted in Fig. 1.

Perceived competence

Students must be adept at online learning if they can use the online tool to improve their academic status. Zhao et al. (2011) claim that the degree to which an ability demand is satisfied affects motivation levels. Pupils who believe they are capable of handling online SRL will have the confidence to manage their own involvement. Affective learning involvement is expected to be linked to this sense of competence. Competency and self-efficacy are related concepts. Self-efficacy, as defined by Hew and Sharifah (2017), is people’s opinion of their ability to organize and complete tasks to produce desired outcomes (Bandura, 2012). In an SM-related scenario, Yang and Brown (2015) illustrated the relationship between students’ use of SM for education and their social competency. The IS literature has connected computer proficiency to affective learning involvement (Rezvani et al., 2017). As per Sørebø et al. (2009), the supposed ease of use of e-learning technology is associated with its perceived benefits and collaborative nature. We hypothesise:

H1: Affective learning involvement is positively impacted by perceived competence.

H2: The use of SM for education is positively impacted by perceived competency.

Perceived autonomy

Students must be willing to self-regulate their own decisions and learning processes in order to be considered autonomous when utilizing SM in educational settings. Several studies have shown the connection between success and self-governance. According to Bedenlier et al. (2020), autonomy support has a significant effect on employee satisfaction and business trust in the context of an organization. Adoption of organizational changes is encouraged, according to Trenshaw et al. (2016), when managers support the changes. Indeed, a sum of studies revealed that autonomy promoted both intrinsic and extrinsic motivation, which had positive outcomes (Williams & Deci, 1996). The perceived support from supervisors affects how beneficial and simple a system is viewed to be in the IS domain (Zhang et al., 2015). In the framework of e-learning, perceived independence affects perceived value and perceived playfulness (Hew & Sharifah, 2017). These theories which maintain that the degree of perceived freedom in SM in classrooms is probably positively correlated with the use of SM for academic goals as well as emotional learning are supported by the findings of the current study. As a result, we recommend the following:

H3: Perceived autonomy has a positive impact on Affective learning involvement.

H4: Perceived autonomy has a positive impact on educational SM use.

Perceived relatedness

SDT had maintained that competence and autonomy were the most important motivators of motivation, despite the fact that relatedness was found to be a substantial antecedent of motivation (Williams & Deci, 1996). According to Rogers (2017), people participate in activities even when they are not especially enjoyable because they need to interact with other people. Put another way, when people feel connected to something, they are more likely to be motivated and invested in it. Numerous research scenarios have supported the association between felt relatedness and motivation (Rogers, 2017). According to Luo et al. (2021), students’ usage of social media for educational purposes is significantly influenced by their peers and acquaintances. Students spend a great deal of time on campuses with their fellow students and exchange modern learning experiences frequently, which may strengthen their both intrinsic and external incentives (Zhang et al., 2015). Thus, we can hypothesize that:

H5: Perceived relatedness has a positive impact on Affective learning involvement.

H6: Perceived relatedness has a positive impact on educational SM use.

Information sharing

Through information sharing, people tell one another, their family, and other contacts about various topics. The quality and content of information exchange determine its effectiveness, and these factors have significant practical implications (Muliadi et al., 2022). Chang and Chuang (2011) believe that knowledge is produced through the integration of facts, theory, and observation.

Learning is enhanced when individuals get together in groups and engage with each other, as they exchange experiences and knowledge (Eid & Al-Jabri, 2016). Research on content and education in an organizational setting indicates that information sharing through the use of SM tools aids organizational learning. According to Alyouzbaky et al. (2022), student use of SM improves educational results and academic performance.

Aslam et al. (2013) examined the impact of information sharing on academic achievement with Khuram, Syed, Ramish, and Aslam. To gauge students’ performance in learning, they employed the cumulative GPA (CGPA) (Alalwan et al., 2019). However, they were unable to find any significant relationships between them. Their success was attributed to the use of a relative (norm-referenced) grading scheme such as the CGPA (Alalwan et al., 2019). Students find it more difficult to communicate their knowledge in the classroom when there is a higher level of competition due to CGPA (Salimi et al., 2022). Examined the relationship between student grades and the volume and caliber of information exchanged. She found that the only relationship between the quantity of information shared and students’ grades (or learning performance) was that there was no association between learning quantity and quality. He and Gunter (2015) state that among the student learning experiences that comprise the learning performance in our study are discussion, self-reliance, leadership, problem-solving, and creativity. We contend that both student achievement and high-quality education are impacted by knowledge sharing. Consequently, we put up the following theory:

H7 Information sharing has a positive impact on Affective learning involvement.

H8: Information sharing has a positive impact on educational SM use.

Collaborative learning environment

Two or more students working together to accomplish a similar learning objective is known as collaborative learning (CL), as defined by Astherhan & Schwarz (2016) and Islamy et al. (2020). Constructive student interaction (CL) is highly valued (Johnson & Johnson, 2009); students are encouraged to ask questions, offer extensive justifications, exchange counterarguments, generate novel concepts and problem-solving strategies, and so forth. Prior research has demonstrated that a crucial element in determining whether or not students gain from CL is student contact (Al-Rahmi et al., 2020). These studies demonstrate the need for supportive surroundings for student interaction as well as the importance of collaborative contact, or the way in which students work together. Research conducted by Alalwan et al. (2019) and Hamadi et al. (2022) highlights the importance of student participation throughout task completion. On-task interaction is the term used to describe interaction that is relevant to the current task. It is noteworthy that this encompasses not only cognitive tasks that aid in the group’s achievement of its goals but also social-affective and regulative activities (Qureshi et al., 2021). Explaining, summarizing, or having direct conversations about the concepts at hand are examples of cognitive processes (Almusharraf & Bailey, 2021). One example of how the instructor is essential to fostering positive student involvement during CL is when they diagnose the group’s progress and step in when necessary (Van Leeuwen et al., 2015). (Almusharraf & Bailey, 2021). There is a risk of positive student involvement if there is insufficient instructor leadership. When teachers fail to identify problems early on and take the necessary action to address them, the collaborative process may not be as effective as it may be, and learning results may suffer as a result (Van Leeuwen et al., 2015). The findings indicate that it can be challenging for educators to guide groups of students engaged in cooperative learning (Van Leeuwen et al., 2015). One example is that it requires teachers to have a range of higher-level competencies (De Hei et al., 2016). This is because teachers are required to oversee multiple groups at the same time during CL, provide support with task content and cooperation strategies, and assess whether intervention is required and, if so, what kind of intervention is most suitable (De Hei et al., 2016). Consequently, we put up the following theory:

H9: Collaborative learning environment has a positive impact on Affective learning involvement.

H10: Collaborative learning environment has a positive impact on educational SM use.

Affective learning involvement

Referred to as “emotional or hedonistic,” affective participation is triggered by affective or intrinsic impulses (Lim & Richardson, 2021). Research has already demonstrated that learning engagement positively affects students’ propensity to continue reading on their mobile devices (Wei et al., 2021), learning outcomes (Brom et al., 2017), and approval of learning management systems (Klobas & McGill, 2010). Participation in cognitive learning encompasses the advanced learning stages connected to a particular learning task. High intellectual engagement in the current study’s setting implies that students actively engage in mobile learning activities and digest the content on digital learning platforms. Consequently, sustained use and other benefits are anticipated from strong engagement in cognitive learning (Sørebø et al., 2009). Conversely, heightened emotional experiences associated with a specific learning activity are represented by affective learning participation. These emotional states are present when pupils are learning, and they will most likely have an effect on the learning outcomes or progress. The more emotionally engaged students are in their learning, the more likely it is that they will stick with a mobile learning platform. As a matter of fact, Wei et al. (2021) found that affective involvement positively influences the intention to continue utilizing mobile reading. Based on the evidence that is currently accessible, we can hypothesize that:

H11: Affective learning involvement has a positive impact on students’ satisfaction.

H12: Affective learning involvement has a positive impact on learning performance.

SM use in education

Online communities, or SM platforms, aim to improve communication, teamwork, and content sharing (Alismaiel et al., 2022c). These platforms act as an open channel of communication in the social life of today, allowing people to meet and share ideas or expertise. According to Al-Rahmi et al. (2021b), Facebook offers many channels that vary in terms of accessibility, engagement, and speed. Posts are accessible to all followers on the network, while private messages are available exclusively to a specific individual. Exactly studies have found that the use of SM sites (such as Facebook, Twitter, and blogs) in the classroom has enhanced effective learning, enriched online interactions, and increased student engagement (Dumford & Miller, 2018). Students’ involvement in the SM collaborative environment enhanced their ability to communicate with one another in groups and their performance in group projects (Saini & Abraham, 2019). Users can communicate in groups and exchange experiences thanks to the collaborative SM environment (Almulla & Alamri, 2021). The environment in question fosters knowledge-sharing behavior and fortifies reciprocal social links among group members, both of which can be explained by the belief in mutual advantages (del Valle et al., 2017). Given this, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H13: Educational SM use has a positive impact on Affective learning involvement.

H14: Educational SM use has a positive impact on students’ satisfaction.

H15: Educational SM use has a positive impact on learning performance.

Students’ satisfaction

perceived usefulness and simplicity of use are two variables that, in the user’s opinion, are critical and significant for the deployment of specific technologies and students’ contentment. These qualities are essential because they make it possible to predict the level of happiness that a technology user will experience (Qureshi et al., 2021). Performance can be predicted by user experience, as is well known. The pleasure that technology makes available has an impact on user adoption, future performance, and the desire to socialize (Sayaf et al., 2021). (Dumpit & Fernandez, 2017) suggested that students’ learning pleasure in this setting might be raised through embedded online interaction. Thus, it stands to reason that a student’s degree of satisfaction will likewise affect how well they do. Performance is impacted by the formal education that facilitators, learners, students, and institutions have acquired as a result of reaching their academic objectives (Sayaf et al., 2021). Shayan and Iscioglu (2017) assert that SM still has an impact on students’ performance in scientific fields. Sayaf et al. (2022) assert that students’ knowledge and learning are supported by the advantages of a fulfilling use of educational technology, such as Facebook and Twitter (Al-Rahmi et al., 2018). To go deeper into this subject, they tried to ascertain how Facebook affected students’ academic performance (Al-Samarraie & Saeed, 2018). Furthermore, SM use helps to create a positive relationship between users’ pleasure and learning results (Sayaf et al., 2022). Given this, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H16: Students’ satisfaction has a positive impact on learning performance.

Learning performance

According to this research, learning show is the degree to which a student participates in progressive learning, which is critical for meeting learning objectives related to gaining new knowledge and skill development over the course of education. Our study’s main focus, student learning performance, is more on the efficacy of the students’ learning process or experience than it is on academic achievement (Ko, 2012). SM sites have educational value and can increase students’ motivation and engagement in their studies (Thorne et al., 2009). When using these SM platforms for learning, professionals and students alike benefit (S.Patel et al., 2013). According to recent studies, SM platforms offer benefits to both professionals and students (Yin & Yuan, 2021). Online SM software enhances the learning environment by encouraging more online engagement and debate among students as compared to traditional learning management solutions (Astatke et al., 2021). The time and location constraints of traditional face-to-face teaching techniques are eliminated by SNS. As to Alamri et al. (2020a), Facebook provides a basic means of contact and information exchange for students, teachers, and other students. Students who utilized Facebook more regularly for SM did better academically than their peers, according to Sabah (2022). However, because they used Facebook more for fun than for discussing and sharing course material, Kirschner & Karpinski (2010) discovered that college students who utilized the SM platform reported lower academic than non-users. The benefits of using SNS for both teaching and learning are not refuted by the findings of Kirschner & Karpinski (2010). Emphasizing social contact will promote meaningful learning and student innovation, claim Al-Rahmi, Al-Rahmi, et al. (2022). Our study focuses on performance or experience in relation to the use of SNS.

Research methodology

Participants in the study

Out of the 300 respondents who received the survey, 293 (97.6%) provided insightful answers. As previously mentioned, 300 students were given samples of questionnaires from King Saud University in Saudi Arabia during the summer semester of 2022, which ran from July to August. After a thorough evaluation, it is evident that seven of the surveys had to be removed since they were not comprehensive. The 293 remaining surveys were then imported into IBM SPSS 26. This meant that, excluding the aforementioned scenarios from the sample surveys, there were just 293 questionnaires left for analysis. Hair et al. (2012) corroborated this phenomenon by stating that outliers have to be disregarded because they frequently yield erroneous statistical conclusions (refer to Table 1).

Measurement tools

The content validity of the measurement scales was demonstrated by modifying the construct items from previous studies. The following were modified from (Ryan & Deci, 2000; Sørebø et al., 2009; Sun et al., 2019; Zhao et al., 2011): basic demographic information (gender, age, and specialty); questionnaire items measuring perceived competence, perceived autonomy, perceived relatedness, and affective learning involvement (each with five items); questionnaire items measuring information sharing, collaborative learning environments, and educational use of SM (each with five items). 45 questionnaire items measuring 9 factors (affective learning involvement, collaborative learning environment, educational SM use, information sharing, perceived autonomy, perceived competence, perceived relatedness, academic achievement, and students’ satisfaction) were adopted, and five items measuring each factor were adopted from Alamri et al. (2020a) and Hosen et al. (2021).

Methodology of the questionnaires (survey)

To assess the research hypothesis, our study is quantitative and uses questionnaire methodologies. To assess the components, we modified and contextualized survey questions from previously approved instruments to fit our research strategy. The poll items were scored using a five-point Likert scale, where 1 represents “strongly disagree” and 5 represents “strongly agree.” Convenience sampling was used to collect the data. The survey’s sample consisted of Saudi Arabian undergraduate students enrolled at King Saud University. Among the targeted classes were foundational courses that are necessary for all students at the university, not just those majoring in management (refer to Table 1).

Convergent validity has been identified using average variance extraction (AVE), which must be less than 0.500. To assess discriminant validity, the heterotrait-monotrait ratio (HTMT), cross-loading, and the Fornell-Larcker criterion were applied. In the meantime, the dependability of the data was assessed using an internal dependability and consistency approach. Values greater than 0.700 are necessary for two dependability metrics: composite reliability (CR) and Cronbach’s alpha. For the assessment model, we reported the significance of the association using the path coefficients, t-value, and p-value.

The questionnaire was given to each respondent by hand in order to gather feedback on how social media is used to study as well as the responses they gave regarding how it affects their enjoyment and academic achievement. Methods for analyzing data: This study used IBM SPSS and partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) for data analysis. The measurement methods and structural models utilized in this study were assessed using the Smart PLS 3.3 software. The accuracy and dependability of the data were assessed as they were being used to build the measurement model. To assess the validity of the data, we reported both discriminant and convergent validity.

Data analysis and result

Measurement and modeling of structural equations (PLS-SEM) were used in this work to analyze the data. In this work, partial least squares (PLS) and structural equation modeling, or SEM, were used to examine the proposed hypotheses. PLS enables researchers to evaluate the reliability and validity of the model and look for correlations across theoretical constructs (Hair et al., 2019). A practical and trustworthy method for managing the reflecting measures and mediating effects is the use of smart-PLS software (Barnes, 2011). Therefore, the linkages in the structural model were assessed using Smart-PLS (3.3.3), particularly for the confirming factor analysis (CFA).

Using SPSS 23, the preliminary descriptive data and correlation were acquired. The parts that follow include more information. Convergent validity: The average variances retrieved (AVEs) from the concepts were used to assess convergent validity. The difference between the variation attributed to measurement errors and the variance represented by indicators of a deep component is shown by AVEs (Chin, 1998). Every one of our constructs has an AVE value greater than 0.5 (Table 2). This suggests that each of the components in our model has enough construct validity (Ramajesthan et al., 2012; Komiak & Benbasat, 2006).

Discriminant validity

To assess the validity of discrimination, the Fornell-Larcker test and the heterotrait-monotrait ratio of associations (HTMT) were used (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). The Fornell-Larcker criterion states that the square root of the AVEs for these latent variables and the factor loadings should be compared in order to confirm discriminant validity. For the latent constructs to exhibit enough discriminant validity, their correlation must be less than the square of the root of the AVEs of the latent variables being studied (Ramakrishnan et al., 2012). Table 3 shows the link between the latent parameters and their square root. There is less association between the latent factors (non-diagonal elements) and the square base of the AVEs (diagonal elements). This implies that our model’s constructs all have strong discriminant validity. Table 4 shows the loading and crossover for each indication.

All of the constructs had outside loadings that were higher than the other constructs (bold). In contrast to the loadings of its other constructs, such as the Collaborative Learning Environment (0.489), Educational Usage of SM (0.421), Information Sharing (0.542), Learning Performance (0.521), Perceived Competence (0.509), Perceived Relatedness (0.528), and Students’ Satisfaction (0.496), the indicator AFLN_1 within the construct of Affective Learning Involvement obtained the highest loading of 0.803. In order to ascertain the discriminant validity of the correlations, we also assessed their HTMT ratio (Henseler et al., 2015) (Table 5). If two constructs were 100% trustworthy, the disattenuated correlation—also referred to as the genuine correlation—between them is determined via the HTMT approach.

Composite reliability

We used the composite reliability metric and Cronbach’s alpha to evaluate the dependability of the internal consistency. All of our constructs had composite dependabilities and Cronbach’s alpha values greater than 0.7 (Table 6), showing adequate reliability.

The variance inflating factor

We searched for multicollinearity-related issues in the structural model. Table 7 indicates that the predictor constructs’ variance inflation factor, or VIF, levels are all less than five, suggesting that the model is not multicollinear, in accordance with Hair et al. (2012) and 2019 (Hair et al.). Researchers could calculate the VIF, or variance inflation factor, to assess redundancy and ascertain the level of convergence in the precursor indicators (Hair et al., 2019). A VIF score of 5, which denotes that 80% of an indicator’s variation is explained by the remainder of the initial indicators linked to the same construct, is indicative of possible multicollinearity issues in the context of PLS-SEM.

This is a reconsideration of the setup of the formative measurement paradigm. In light of the prior conversation, we propose removing an indicator to reduce multicollinearity issues. If this indicator’s formative measurement approach coefficient (outer weight) does not differ significantly from zero, (1) multicollinearity is very high (as shown by a VIF value of 5 or higher), and (3) the remaining indicators sufficiently capture the domain of the being studied. A test for sophisticated model skills was integrated with basic model testing.

Nevertheless, “the importance of convergence should be noted by announcing the values to change the extension factor before offering details of the main model” (VIF). Interestingly, the collinearity of the indexing was assessed (Hair et al., 2019). Collaborative learning environments, the use of SM in education, information sharing, perceived competence, perceived relatedness, and autonomy are the factors that determine emotional learning involvement (Table 7). Multiple problems are frequently viewed as having more than three structures; hence, VIF values must be three. As a predictor of affective learning participation, educational SM use had values of 2.074 and 1.940, respectively, according to Table 7’s data test results, which indicate that all VIFs are 3. Therefore, the study’s model does not have a collinearity issue.

Model fit analysis

A model fit analysis was performed to show that the proposed model is valid. Table 6 presents evidence that all parameter estimates were higher than the minimal threshold value, hence confirming the appropriateness of the suggested model. Additionally, bootstrap samples were produced using the revised sample data. To test the model fit in PLS-SEM, a total of seven key indicators were used: SRMR, RMSEA, Chi-square, Degrees of Freedom, ChiSqr/dF, NFI, and CFI. Henseler et al. (2015) and Bentler & Bonett, (1980) state that the threshold values for SRMR, RMSEA, and NFI are, respectively, less than 0.08 and greater than 0.90. Moreover, the ChiSqr/dF value is, therefore, less than 3.00. Table 8 shows the SRMR and RMSEA indexes, which are 0.056 and 0.068, respectively. Additionally, 0.913 and 0.918, respectively, are the NFI and CFI indices. All seven primary signals for the model fit indices indicated that the model was typically rather well-matched. Table 8 displays the specifics of the model fit and collinearity evaluations.

Assessment model and hypothesis testing

To test our theories, we used PLS. PLS enables the simultaneous evaluation of multiple interdependent relationships. A structural model in PLS illustrates the connections between the theoretical ideas. Using the bootstrapping technique, 500 recommended random samples were generated with SmartPLS (Hair et al., 2019). The hypotheses were evaluated using a one-tailed t-test due to their unidirectional nature. The study model’s route evaluation and the variance that each path supplied were assessed by looking at the connections between all of the hypotheses. Every theory was proven correct.

The path coefficient results are shown in Table 9 and Figs. 2 and 3. A relationship between affective learning involvement and perceived competence (H1 = 0.122, t = 2.258), perceived autonomy (H3 = 0.485, t = 8.649), perceived relatedness (H5 = 0167, t = 2.556), information sharing (H7 = 0.179, t = 3.854), and collaborative learning environment (H9 = 0183, t = 2.512) has been found in the first, third, fifth, seventh, and ninth (H1, H3, H5, H7, and H9). The results showed a significant and positive correlation, supporting H1, H3, H5, H7, and H9. Additionally, the hypothesis numbers two, four, six, eight, and ten (H2, H4, H6, H8, and H10) suggest a connection between perceived competence (H2 β = 0.147, t = 2.339), With educational SM use for teaching and learning, there is a correlation between perceived autonomy (H4 β = 0.137, t = 2.150), perceived relatedness (H6 β = 0.168, t = 2.310), information sharing (H8 β = 0.208, t = 3.628), and collaborative learning environment (H10 β = 0.253, t = 3.475).

The results showed a significant and positive correlation, supporting H2, H4, H6, H8, and H10. Furthermore, the eleventh and twelfth hypotheses (H11 and H12) demonstrate a relationship between students’ happiness on SM platforms (H12 β = 0.262, t = 4.076) and affective learning participation (H11 β = 0.326, t = 6.367). Consequently, H11 and H12 are endorsed. The thirteenth, fourteenth, and fifteenth hypotheses (H13, H14, and H15) demonstrate a relationship between the use of SM in education and students’ satisfaction (H14 β = 0.532, t-value = 11.373), learning performance (H15 β = 0.238, t-value = 3.622), and affective learning involvement (H13 β = −0.156, t-value = 2.222). The results showed a significant and positive correlation, supporting the three hypotheses (H13, H14, and H15). Lastly, the hypothesis is that the impact of learning performance on student satisfaction is positively and strongly correlated with it (H16 β = 0.191, t = 2.560). The results showed a significant and positive correlation; as a result, H16 is validated; refer to Figs. 2 and 3.

Discussion and implications

The relationships between student satisfaction, academic achievement, and views of competence, autonomy, relatedness, information sharing, collaborative learning settings, affective learning engagement, and SM use in the classroom are clarified by the results of our study. Furthermore, the effective learning environment that is described throughout the educational use of SM may be helpful to users and students.

This makes it easier to switch to depictions of the necessities for education and instruction that are more accurate. The findings and observations demonstrate how using social networks to foster a supportive and upbeat environment is beneficial for learning, teamwork, and information sharing. Furthermore, by enhancing views of competence, independence, and relatedness, it can enhance affective engagement with learning in educational settings. By encouraging student interaction and teamwork, as well as supporting discussion groups and the finishing of assignments or research projects, improves the environment, which has a greater effect on students’ performance (Al-Qaysi et al., 2020; Al-Rahmi et al., 2022a; Al-Rahmi et al., 2022c).

Additionally, SM is demonstrated by improvements in research skills among teachers and the sharing of ideas among students for use in education. SM is more useful for educational purposes than in-person interactions (Rodriguez-Triana et al., 2020). The determination of the education was to determine whether self-determination requirements had an impact on college students’ emotional learning engagement. The study’s conclusions demonstrate that when using a certain SM platform, users are more likely to use it for learning if they receive social influence and encouragement for doing so.

The current study discovered that perceived competence had a substantial impact on affective learning involvement or educational usage of SM in the online learning environment, which is consistent with the results of Chiu (2022) and Hsu et al. (2019). According to one theory, college students who possess great self-management abilities are better at acquiring self-discipline than other students and view SM as one of the most crucial tools for self-learning. Learners are inclined to participate in mobile learning when they experience social effects and support from the SM platform they are utilizing for learning.

Moreover, the current study discovered that perceived competence had a substantial impact on affective learning involvement or educational usage of SM in the online learning environment, which is consistent with the results of Chiu (2022) and Hsu et al. (2019). According to one theory, college students who possess great self-management abilities are better at acquiring self-discipline than other students and view SM as one of the most crucial tools for self-learning. The current study discovered that attitudes about relatedness, independence, and learning support have a major impact on students’ college affective learning engagement when using educational SM.

According to the hypotheses (H1, H2, H3, H4, H5, and H6), relatedness, competence, and autonomy are related to affective learning participation and with using SM platforms for educational purposes. The hypotheses are validated because the findings indicate a positive and substantial association. The results align with earlier studies (Nikou & Economides, 2017; Zhao et al., 2011) that examined the impact of relatedness, competence, and autonomy on psychological learning involvement. This demonstrates that college students would use SM in learning contexts more when their education activity was supported by the SDT.

The research findings (H7, H8, H9, and H10) associate the sharing of information and collaborative environments for learning with emotional engagement with learning and instructional use of SM platforms. The results demonstrate that information sharing and interactive classrooms greatly enhance the use of social media for educational purposes, and these two elements are identified as the most important cursor signals for this purpose. This finding’s practical explanation is that students do not view social media platforms as traditional learning environments; rather, they use them for multitasking. As a result, the investigation’s findings confirm previous findings about the correlations between the factors (Yilmaz, 2016; Alalwan et al., 2019).

Hypotheses (H11, H12, H13, H14, and H15) that are based on the research’s findings suggest that SM use, students’ pleasure, affective learning involvement, and academic success are positively and significantly correlated. The hypotheses are validated because the findings indicate a positive and substantial association. Table 9 (affective learning participation and educational usage of SM) shows that students’ academic progress and satisfaction are greatly improved by SM use. It’s interesting to notice that student contentment and SM use in the classroom are somewhat more correlated than academic accomplishment.

This is probably due to the fact that students were more aware of the ways in which using SM for teaching and learning could improve their education. The findings also suggest that three factors are critical to students’ academic success: affective learning engagement, SM use for education, and student satisfaction. Furthermore, previous research has demonstrated that provided that the type and appropriateness of the utilization are taken into consideration, system utilization is often associated with gains in learning performance (DeLone & McLean, 2003), which provides indirect support for the observed results.

Moreover, the general results align with earlier empirical studies that demonstrate a robust positive correlation between students’ academic performance and their utilization of social media for education (Alamri et al., 2020b, 2020a; Sobaih et al., 2022) and the influence of social media on developing (Al-Rahmi et al., 2021a; Al-Rahmi et al., 2022d; Sayaf et al., 2022).

In the end, the results clearly validate hypothesis (H16) and show that learning success in educational institutions has a beneficial influence on students’ satisfaction. Hypothesis 16 is validated by the study’s findings, which demonstrate a substantial relationship between students’ happiness and their academic performance in higher education. Conversely, it is more probable to be applied in educational settings if a greater number of students are satisfied with their learning outcomes. Numerous scholars have investigated the significance of students’ contentment in the classroom. Thus, the results of the analysis corroborate previous conclusions on the associations among the variables being studied (Al-Rahmi et al., 2022b; Alhussain et al., 2020). For this reason, this study employs distinct methodologies compared to previous studies.

The study first suggests that there may be a relationship, mediated by educational SM usage, between affective learning participation, self-determination theory (SDT), and SM usage for education. With this information, students may create and implement strategies that promote SM use in the classroom that are both responsible and productive. One way to promote student participation and teamwork in the classroom would be to integrate SM platforms. Secondly, it is imperative to attend to the academic achievement and contentment of pupils.

This is demonstrated by comprehending the role that SDT plays as a mediator between emotional learning and educational SM use. By emphasizing autonomy, competence, and relatedness, students can develop curriculum frameworks and instructional practices that enable self-directed learning (SDT). This entails promoting knowledge exchange and cultivating a cooperative learning atmosphere. This tactic might promote increased drive and participation in the educational process. Thirdly, the findings demonstrate how crucial it is for students to grasp SDT and how different teaching approaches are impacted by this understanding. Through cooperative information exchange, students can acquire the skills necessary to integrate SDT concepts into their instructional strategies.

This could mean offering workshops, seminars, and ongoing support to students in order to provide them with the knowledge and skills needed to create a motivating and supportive learning environment. As a result, the study emphasizes the need to promote effective learning engagement and demonstrates how crucial student emotional engagement is to achieving effective learning outcomes.

Education establishments can focus on creating student-centered learning environments that prioritize the needs of each individual, encourage collaboration, and provide opportunities for self-expression in accordance with SDT principles. By putting these findings into practice, pupils as well as stakeholders can contribute to the development of more interesting and successful teaching strategies that raise student satisfaction and overall learning success. Politicians should consider how SM usage impacts students’ participation in emotional learning and how it is used in the classroom. To promote responsible and educational SM use on college campuses, policies and guidelines can be developed.

This means addressing issues related to digital literacy and privacy in addition to creating a framework that promotes the beneficial integration of SM into the educational process. Compared to earlier research in these areas, which was unable to determine the influence of affective learning engagement on the usage of SM in the classroom, our findings offer a substantial theoretical advance (Alismaiel et al., 2022a; Ryan & Deci, 2020).

Prior to presenting the study’s conclusions, it is important to recognize its limitations. First of all, real-use behavior among college students is not taken into consideration by the model that is suggested in this study. The mentioned limitation should not be construed as negating our findings since other instances of empirical study have substantiated the causal relationship between conduct and intention (Alismaiel et al., 2022a; Ryan & Deci, 2020; Venkatesh & Davis, 2000).

However, the accuracy with which they predict outcomes may still vary depending on how different evaluations of intention are made. More research will be possible because of the study model’s incorporation of real-world ongoing activity. A further potential limitation could be found in the diverse educational and cultural settings. For example, Saudi Arabia, a nation that emphasizes collectivism, is where the current study was conducted. There may be various patterns in the effects of SDT demands on students’ motivation and behavior in individualistic societies where people function more freely. It is recommended that future research expand on this paradigm by analyzing the findings in diverse cultural contexts.

Secondly, the study only included students from one Saudi Arabian university who had previously used SM platforms as teaching aids, so the sample size was somewhat limited because only students from those four academic subjects were chosen for participation. Future research could replicate this study at other academic institutions with more participants, but caution should be exercised because the results may not be generalizable to other academic institutions. Lastly, the suggested model was validated using self-reported measures. The truth is that privacy issues prevented the writers from obtaining objective information on GPA (such as student grades).

Therefore, to test the proposed paradigm, future research may employ objective metrics and concentrate on one or more courses. In order to provide a more comprehensive model (such as gender, specialization, and experience), future research may look into a wide range of determinants for SM use predictors (such as instructors and students with peers, ease of use, characteristics, and perceived enjoyment), as well as other mediating factors.

The usage of SM in the classroom and how it impacts students’ engagement with emotional learning have drawn attention in recent years. SM platforms, including SM websites (SNS) like Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram, can be used in a range of educational settings to support cooperative argumentation, equitable participation, and affective learning (Näykki et al., 2019). Several significant insights about the roles of SM use in education and emotional learning involvement are as follows:

-

Both positive and negative effects: Using SM might have an impact on students’ emotional states. Stress, worry, and depression are just a few of the unpleasant emotions that can arise from it, but it can also help learners develop positive emotions and build their emotional repertoire. This aligns with the findings of Chen & Xiao (2022).

-

Moderating Roles: The association between SM use in educational settings and learning outcomes can be weakened by task-technology fit (TTF) as well as perceived risk (PR).

If educators and legislators are aware of these moderator factors, they can make more informed decisions on how to include SM in the classroom. This aligns with the findings of Sabah and Altalbe (2022). SM affordances: SM platforms can offer students a number of advantages, such as better chances for distance learning, enhanced literacy, and extended communication abilities. This aligns with the findings of Chen and Xiao (2022).

Social comparison theory: Students may experience negative emotions and emotive learning engagement as a result of comparing their experiences and successes on SM, which can lead to a variety of issues. This aligns with the findings of Bui et al. (2023). SM Integration in Education: Educational institutions may integrate technological advances such as learning games, SM sites, and digital manufacturing into their learning activities to enhance emotional learning involvement. This aligns with the findings of Näykki et al. (2019).

Both positive and negative effects on emotional learning involvement might result from the use of SM in the classroom. Teachers, legislators, and researchers need to understand SM’s affordances as well as the moderating effects of PR and TTF in order to make well-informed judgments about SM integration in the tutorial room. In the context of digital education, addressing social comparison theory and its potential negative effects on students’ emotional states might help improve affective learning involvement.

Conclusion

The study’s findings are consistent with the idea that factors that promote students’ academic performance and happiness include competence, autonomy, relatedness, information sharing, and a collaborative learning environment. The findings also showed how students’ views of competence, autonomy, and relatedness affected their enjoyment and academic performance, which encouraged affective learning engagement and the instructional use of SM for teaching and learning.

Similarly, the results demonstrated that students’ information-sharing and collaborative learning settings are impacted by the use of SM in the classroom, which in turn influences their satisfaction and academic performance. The results also supported the application of SDT in combination with exogenous variables to investigate students’ emotional learning engagement and the pedagogical advantages of SM instruction to improve students’ happiness and achievement in postsecondary education.

In general, SM promotes students’ academic activities, knowledge sharing, information exchange, and peer communication through information sharing and collaborative learning environments. Subsequent studies using one or more courses and objective measurements may test the proposed model, depending on the restrictions of the research design and the quantitative approach selected. Subsequent studies might look at a variety of antecedents for students using SM for academic purposes.

Data availability

The datasets generated during the analysis of this research were shared in the supplementary files.

References

Abdullah Moafa F, Ahmad K, Al-Rahmi WM, Yahaya N, Bin Kamin Y, Alamri MM (2018) Develop a model to measure the ethical effects of students through social media use. IEEE Access 6:56685–56699. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2018.2866525

Ahmad F, Huvila I (2019) Organizational changes, trust and information sharing: an empirical study. Aslib J Inf Manag 71(5):677–692. https://doi.org/10.1108/AJIM-05-2018-0122

Al-Adwan AS, Albelbisi NA, Hujran O, Al-Rahmi WM, Alkhalifah A (2021) Developing a holistic success model for sustainable e-learning: a structural equation modeling approach. Sustainability (Switzerland), 13(16). https://doi.org/10.3390/su13169453

Alalwan N, Al-Rahmi WM, Alfarraj O, Alzahrani A, Yahaya N, Al-Rahmi AM (2019) Integrated three theories to develop a model of factors affecting students’ academic performance in higher education. IEEE Access 7:98725–98742. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2019.2928142

Alamri MM, Almaiah MA, Al-Rahmi WM (2020a). Social media applications affecting students’ academic performance: a model developed for sustainability in higher education. Sustainability (Switzerland) 12(16). https://doi.org/10.3390/su12166471

Alamri MM, Almaiah MA, Al-Rahmi WM (2020b) The role of compatibility and task-technology fit (TTF): on social networking applications (SNAs) usage as sustainability in higher education. IEEE Access 8:161668–161681. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2020.3021944

Alenazy WM, Mugahed Al-Rahmi W, Khan MS (2019) Validation of TAM model on social media use for collaborative learning to enhance collaborative authoring. IEEE Access 7:71550–71562. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2019.2920242

Alhussain T, Al-Rahmi WM, Othman MS (2020) Students’ perceptions of social networks platforms use in higher education: a qualitative research. Int J Adv Trends Comput Sci Eng 9(3):2589–2603. https://doi.org/10.30534/ijatcse/2020/16932020

Alismaiel OA, Cifuentes-Faura J, Al-Rahmi WM (2022a) Online learning, mobile learning, and social media technologies: an empirical study on constructivism theory during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability (Switzerland) 14(18). https://doi.org/10.3390/su141811134

Alismaiel OA, Cifuentes-Faura J, Al-Rahmi WM (2022b) Social media technologies used for education: an empirical study on TAM model during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front Educ 7:280. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2022.882831

Alismaiel OA, Cifuentes-Faura J, Al-Rahmi WM (2022c) Social media technologies used for education: an empirical study on TAM model during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front Educ 7. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2022.882831

Al-Maatouk Q, Othman MS, Aldraiweesh A, Alturki U, Al-Rahmi WM, Aljeraiwi AA (2020) Task-technology fit and technology acceptance model application to structure and evaluate the adoption of social media in academia. IEEE Access 8:78427–78440. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2020.2990420

Almulla MA, Alamri MM (2021) Using conceptual mapping for learning to affect students’ motivation and academic achievement. Sustainability (Switzerland) 13(7). https://doi.org/10.3390/su13074029

Almusharraf NM, Bailey D (2021) Online engagement during COVID-19: Role of agency on collaborative learning orientation and learning expectations. J Comput Assist Learn 37(5):1285–1295. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcal.12569

Al-Qaysi N, Mohamad-Nordin N, Al-Emran M (2020) A systematic review of social media acceptance from the perspective of educational and information systems theories and models. J Educ Comput Res 57(8):2085–2109. https://doi.org/10.1177/0735633118817879

Al-Qaysi N, Mohamad-Nordin N, Al-Emran M (2021) Factors affecting the adoption of social media in higher education: a systematic review of the technology acceptance model. In: Studies in systems, decision and control. vol. 295584. Springer. pp. 571–584

Al-Rahmi AM, Al-Rahmi WM, Alturki U, Aldraiweesh A, Almutairy S, Al-Adwan AS (2022a) Acceptance of mobile technologies and M-learning by university students: an empirical investigation in higher education. Educ Inf Technol 27(6):7805–7826. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-022-10934-8

Al-Rahmi AM, Shamsuddin A, Alturki U, Aldraiweesh A, Yusof FM, Al-Rahmi WM, Aljeraiwi AA (2021a) The influence of information system success and technology acceptance model on social media factors in education. Sustainability (Switz.) 13(14):7770. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13147770

Al-Rahmi AM, Shamsuddin A, Wahab E, Al-Rahmi WM, Alismaiel OA, Crawford J (2022b) Social media usage and acceptance in higher education: A structural equation model. In: Frontiers in education. vol. 7. Frontiers Media SA

Al-Rahmi AM, Shamsuddin A, Wahab E, Al-Rahmi WM, Alturki U, Aldraiweesh A, Almutairy S (2022c) Integrating the role of UTAUT and TTF model to evaluate social media use for teaching and learning in higher education. Front Public Health 10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.905968

Al-Rahmi AM, Shamsuddin A, Wahab E, Al-Rahmi WM, Alyoussef IY, Crawford J (2022d) Social media use in higher education: Building a structural equation model for student satisfaction and performance. Front Public Health 10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.1003007

Al-Rahmi WM, Alias N, Othman MS, Marin VI, Tur G (2018) A model of factors affecting learning performance through the use of social media in Malaysian higher education. Comput Educ 121:59–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2018.02.010

Al-Rahmi WM, Yahaya N, Alamri MM, Alyoussef IY, Al-Rahmi AM, Kamin YBin (2021b) Integrating innovation diffusion theory with technology acceptance model: supporting students’ attitude towards using a massive open online courses (MOOCs) systems. Interact Learn Environ 29(8):1380–1392. https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2019.1629599

Al-Rahmi WM, Yahaya N, Alturki U, Alrobai A, Aldraiweesh AA, Omar Alsayed A, Bin Kamin Y (2020) Social media–based collaborative learning: the effect on learning success with the moderating role of cyberstalking and cyberbullying. Interact Learn Environ 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2020.1728342

Al-Samarraie H, Saeed N (2018) A systematic review of cloud computing tools for collaborative learning: opportunities and challenges to the blended-learning environment. Comput Educ 124:77–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2018.05.016

Alturki U, Aldraiweesh A (2022). Students’ perceptions of the actual use of mobile learning during COVID-19 pandemic in higher education. Sustainability (Switzerland), 14(3). https://doi.org/10.3390/su14031125

Alwagait E, Shahzad B, Alim S (2015) Impact of social media usage on students academic performance in Saudi Arabia. Comput Hum Behav 51:1092–1097. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.09.028

Alyoussef IY, Alamri MM, Al-Rahmi WM (2019) Social media use (SMU) for teaching and learning in Saudi Arabia. Int Recent Technol. Eng 8(4):942–946

Alyouzbaky BA, Al-Sabaawi MYM, Tawfeeq AZ (2022) Factors affecting online knowledge sharing and its effect on academic performance. VINE J Inf Knowl Manag Syst. https://doi.org/10.1108/VJIKMS-01-2022-0015

Aslam MMH, Shahzad K, Syed AR, Ramish A (2013) Social capital and knowledge sharing as determinants of academic performance. J Behav Appl Manag 15(1). https://doi.org/10.21818/001c.17935

Astatke M, Weng C, Che S (2021) A literature review of the effects of social networking sites on secondary school students’ academic achievement. In: Interactive learning environments. Routledge. pp. 1–17

Bandura A (2012) Social foundations of thought and action. In: The health psychology reader. SAGE Publications Ltd, pp 94–106

Bedenlier S, Bond M, Buntins K, Zawacki-Richter O, Kerres M (2020) Facilitating student engagement through educational technology in higher education: a systematic review in the field of arts and humanities. In: Australasian J Educ Technol. vol. 36, Issue 4, pp 126–150

Bentler PM, Bonett DG (1980) Significance tests and goodness of fit in the analysis of covariance structures. Psychol Bull 88(3):588–606. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.88.3.588

Brom C, Děchtěrenko F, Frollová N, Stárková T, Bromová E, D’Mello SK (2017) Enjoyment or involvement? Affective-motivational mediation during learning from a complex computerized simulation. Comput Educ 114:236–254. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2017.07.001

Bui HP, Ulla MB, Tarrayo VN, Pham CT (2023) The roles of social media in education: affective, behavioral, and cognitive dimensions. Front Psychol 14:1–3

Capriotti P, Zeler I (2023) Analysing effective social media communication in higher education institutions. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 10(1):10. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-02187-8

Chang HH, Chuang SS (2011) Social capital and individual motivations on knowledge sharing: Participant involvement as a moderator. Inf Manag 48(1):9–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2010.11.001

Chawinga WD (2017) Taking social media to a university classroom: teaching and learning using Twitter and blogs. Int J Educ Technol High Educ 14(1):3. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-017-0041-6

Chen M, Xiao X (2022) The effect of social media on the development of students’ affective variables. Front Psychol 13:1010766

Chin WW (1998) Issues and opinion on structural equation modeling. MIS Q Manag Inf Syst. vol. 22, Issue 1. https://www.jstor.org/stable/249674

Chiu TK (2023) Student engagement in K-12 online learning amid COVID-19: a qualitative approach from a self-determination theory perspective. Interact Learn Environ 31(6):3326–3339

Chiu TKF (2022) Applying the self-determination theory (SDT) to explain student engagement in online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Res Technol Educ 54(S1):S14–S30. https://doi.org/10.1080/15391523.2021.1891998

Chugh R, Grose R, Macht SA (2021) Social media usage by higher education academics: a scoping review of the literature. Educ Inf Technol 26(1):983–999. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-020-10288-z

De Hei MSA, Sjoer E, Admiraal W, Strijbos JW (2016) Teacher educators’ design and implementation of group learning activities. Educ Stud 42(4):394–409. https://doi.org/10.1080/03055698.2016.1206461

del Valle ME, Gruzd A, Haythornthwaite C, Paulin D, Gilbert S (2017) Social media in educational practice: faculty present and future use of social media in teaching. Proc Annu Hawaii Int Conf Syst Sci 2017:164–173. https://doi.org/10.24251/hicss.2017.019. Janua

DeLone WH, McLean ER (2003) The DeLone and McLean model of information systems success: a ten-year update. J Manag Inf Syst 19(4):9–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421222.2003.11045748

Dumford AD, Miller AL (2018) Online learning in higher education: exploring advantages and disadvantages for engagement. J Comput High Educ 30(3):452–465. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12528-018-9179-z

Dumpit DZ, Fernandez CJ (2017) Analysis of the use of social media in higher education institutions (HEIs) using the technology acceptance model. Int J Educ Technol High Educ 14(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-017-0045-2

Eid MIM, Al-Jabri IM (2016) Social networking, knowledge sharing, and student learning: The case of university students. Comput Educ 99:14–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2016.04.007

Fornell C, Larcker DF (1981) Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J Mark Res 18(1):39–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378101800104

Foroughi B, Griffiths MD, Iranmanesh M, Salamzadeh Y (2022) Associations between Instagram addiction, academic performance, social anxiety, depression, and life satisfaction among university students. Int J Ment Health Addict 20(4):2221–2242. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-021-00510-5

Garn AC, Morin AJS, Lonsdale C (2019) Basic psychological need satisfaction toward learning: a longitudinal test of mediation using bifactor exploratory structural equation modeling. J Educ Psychol 111(2):354–372. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000283

Hair JF, Risher JJ, Sarstedt M, Ringle, CM (2019). When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. In: European business review. vol. 31, Issue 1. Emerald Group Publishing Ltd. pp. 2–24

Hair JF, Sarstedt M, Ringle CM, Mena JA (2012) An assessment of the use of partial least squares structural equation modeling in marketing research. J Acad Mark Sci 40(3):414–433. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-011-0261-6

Hamadi M, El-Den J, Azam S, Sriratanaviriyakul N (2022) Integrating social media as cooperative learning tool in higher education classrooms: an empirical study. J King Saud Univ Comput Inf Sci 34(6):3722–3731. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jksuci.2020.12.007

Hameed I, Haq MA, Khan N, Zainab B (2022) Social media usage and academic performance from a cognitive loading perspective. Horizon 30(1):12–27. https://doi.org/10.1108/OTH-04-2021-0054

Han I, Shin WS (2016) The use of a mobile learning management system and academic achievement of online students. Comput Educ. 102:79–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2016.07.003

He J, Gunter G (2015) Examining factors that affect students’ knowledge sharing within virtual teams. J Interact Learn Res 26(2):169–187

Henseler J, Ringle CM, Sarstedt M (2015) A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J Acad Mark Sci 43(1):115–135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-014-0403-8

Hew TS, Sharifah SL (2017) Applying channel expansion and self-determination theory in predicting use behaviour of cloud-based VLE. Behav Inf Technol 36(9):875–896. https://doi.org/10.1080/0144929X.2017.1307450

Hosen M, Ogbeibu S, Giridharan B, Cham TH, Lim WM, Paul J (2021) Individual motivation and social media influence on student knowledge sharing and learning performance: evidence from an emerging economy. Comput Educ 172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2021.104262

Hsu HCK, Wang CV, Levesque-Bristol C (2019) Reexamining the impact of self-determination theory on learning outcomes in the online learning environment. Educ Inf Technol 24:2159–2174

Hsu HCK, Wang CV, Levesque-Bristol C (2019) Reexamining the impact of self-determination theory on learning outcomes in the online learning environment. Educ Inf Technol 24(3):2159–2174. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-019-09863-w

Islamy FJ, Yuniarsih T, Kusnendi, Wibowo LA (2020) The power of knowledge donating and knowledge collecting for academic performance: developing Indonesian students’ knowledge sharing models. In: Advances in business, management and entrepreneurship. CRC Press. pp. 504–507

Jansen in de Wal J, van den Beemt A, Martens RL, den Brok PJ (2020) The relationship between job demands, job resources and teachers’ professional learning: is it explained by self-determination theory? Stud Contin Educ 42(1):17–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/0158037X.2018.1520697

Jeno LM, Adachi PJC, Grytnes JA, Vandvik V, Deci EL (2019) The effects of m-learning on motivation, achievement and well-being: a self-determination theory approach. Br J Educ Technol 50(2):669–683. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.12657