Abstract

Ride-hailing, as part of wider transitions to smart city, has emerged as a beneficial complement to urban public transport. However, the frequent occurrence of ride-hailing safety accidents in multiple countries has raised concerns about passenger safety on an international scale. Within this context, this study aims to investigate female passengers’ safety perception and prevention action when using ride-hailing services, helping establish better management and protection mechanisms for passenger safety. Using objective data from 7898 ride-hailing criminal adjudications (674 passenger victimizations) and subjective data from 596 Chinese female respondents, the safety perception scale and prevention tendency scale, with six potential variables, are developed to further examine the heterogeneity of perception and prevention. Results reveal that driver’s words and actions directly influence female passengers’ safety judgments regarding ride-hailing services and that traveling with companions significantly enhances their perceived safety. The main preventative actions identified include relying on mobile phones for information and communication, as well as avoiding risky ride-hailing situations. Furthermore, the analysis of individual heterogeneity has uncovered perception and prevention differences based on factors such as age, education level, residence conditions, ride-hailing frequency, and victimization experiences. These differences are evident in perception biases towards driver attitudes and accompanying travel, as well as variations in risk avoidance behaviors. The insights inductively derived hold fundamental conceptual and empirical value for scholarship on safety evaluation and crime prevention in the context of shared mobility. Additionally, the countermeasures proposed in this study can serve as a theoretical reference for enhancing the safety supervision of ride-hailing services, contributing to the establishment of safer, more reliable and more sustainable shared travel environment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The rapid advancement of mobile Internet and artificial intelligence technologies has propelled the emergence of app-based on-demand mobility services, such as car-sharing and ride-hailing, from their initial launch in North America and Europe to their gradual expansion to other regions (Acheampong et al. 2020). Notably, prominent ride-hailing companies such as Lyft in the US, Didi Chuxing in China, Ola in India, Snapcar in France, and Uber on a global scale have experienced significant growth. For instance, as of August 2018, Uber had established a wide presence in around 800 cities (Tirachini, 2019). In San Francisco alone, an estimated 170,000 ride-hailing trips with Uber or Lyft are conducted on weekdays, constituting about 15% of urban transport share (SFCTA, 2017). Didi Chuxing currently boasts approximately 550 million users, solidifying its position as the largest ride-hailing company in China. Statista’s 2022 data on ride-hailing users show a user penetration rate of 15.7% in Europe, 22.5% in the Americas, and a much higher rate of 33.4% in China, with a user base of 472 million individuals (CNNIC, 2023). This indicates that at least a third of citizens are ride-hailing users. The popularity of ride-hailing has substantially met the demand in the urban transportation market, offering a valuable complement to public transport (PT) (Cats et al. 2022), especially in densely populated areas such as China and Europe (Goodspeed et al. 2019; Gomez et al. 2021). Additionally, this service has effectively mitigated the shortcomings and issues stemming from information asymmetry in the traditional taxi services (Nguyen-Phuoc et al. 2021), as well as reduced the necessity for private vehicle usage, firmly establishing itself as a high-quality public travel alternative (Flor et al. 2021).

However, recent years have witnessed several media reports about safety incidents of ride-hailing passengers, including leaking user information (Duan et al. 2020; Zhang et al. 2017) and encroaching upon personal and property security (Guo et al. 2019). On one hand, this can be ascribed to the low entry threshold for drivers, increasing the likelihood of felons becoming ride-hailing drivers, thereby exposing passengers to the risk of theft, assault, and even homicide (Chaudhry et al. 2018; Guo et al. 2019; Tang et al. 2021). On the other hand, ‘driver behaviors’, such as reckless driving and distracted driving, further increase passengers’ safety risks (Acheampong, 2021; Mao et al. 2021). Related research surveys indicate considerable variability in victimization rates across different cities, with certain regions, such as Mexico City and Sao Paulo in North and South America, Italy, Sweden, and France in Europe, and Egypt in Africa, exhibiting markedly higher victimization rates than cities in other areas, like Guangzhou and Tokyo in Southeast Asia (Ceccato and Loukaitou-Sideris, 2022; Coppola and Silvestri, 2021; D’ Arbois de Jubainville and Vanier, 2017; Yates and Ceccato, 2020). According to Uber’s US Safety Report, a major focus is on the issue of sexual assault, with 3045 related incidents recorded and about 100 drivers charged for sexual assault in 2018 (Sun et al. 2020). Concurrently, Didi Chuxing reported over 50 cases of drivers sexually assaulting or harassing passengers in China during the same period. The exposure of these incidents caused users to question the safety of ride-hailing and carefully choose their travel mode. Consequently, ensuring passengers’ personal safety has emerged as a focal point of societal concern and a pressing issue to be solved urgently (Acheampong et al. 2020).

Globally, a significant proportion of victims were female, particularly young girls and women who heavily rely on PT for their travel demands, as demonstrated in numerous studies (Coppola and Silvestri, 2021; Tang et al. 2021; Yates and Ceccato, 2020). International research surveys have also pointed to the fact that a vast majority of victims on PT trips are vulnerable groups, such as women (Madan and Nalla, 2016; Ouali et al. 2020). Notably, in Mexico, the majority of women have experienced an assault during their trips (Ceccato and Loukaitou-Sideris, 2022). UN Women (2017) has reported that verbal and physical harassment in public spaces is routine for women worldwide, let alone in concealed spaces such as ride-hailing, inevitably heightening the crime likelihood of drivers. Moreover, women are conventionally perceived as vulnerable and less capable of self-defence, exhibiting lower levels of safety and in greater need of protection (Cresswell and Uteng, 2008; Noor and Iamtrakul, 2023). As a result, they are more likely to experience fear and anxiety in travel environments compared to men (Ajayi, 2020; Coppola and Silvestri, 2021; D’ Arbois de Jubainville and Vanier, 2017; Ouali et al. 2020). Particularly during nighttime travels, women are more vigilant about safeguarding themselves from potential perpetrators. Additionally, a survey conducted by Dunckel Graglia (2015) discovered that women exhibited a significantly higher rate of complaints about ride-hailing’s safety issues than men. All these signs point towards women being more attuned to safety risks and demonstrating heightened vigilance. Despite ongoing improvements in safety regulations and associated legal systems, travel safety remains a paramount concern for female users when opting for ride-hailing services, especially at night. It is evident that the efficacy of potential solutions largely depends on passengers’ perception of actual conditions, including driver, vehicle and travel environment. So much so that United Nations (2022) proposed a target, namely safety and sustainable transport systems should specifically consider the needs of vulnerable groups, including women, children, disabled people and the elderly by 2030 (Flor et al. 2021).

This study focuses on women and examines the safety perceptions and preventative actions against potential risks during ride-hailing. Utilizing reported ride-hailing accident data and subjective empirical data from passengers in various cities in China, the safety perception scale and preventative tendency scale are developed. And through an inductive exploratory analysis of the data, six latent variables are identified to reveal the heterogeneity in individuals’ perceptions and preventions, filling a research gap identified by Yang et al. (2022). Hence, our study was structured as follows: The “Literature Review” section offers an overview of the exiting literature, while the “Methodology” section details the data collection and analysis, identifying the observed variables related to safety perception and preventative tendencies, as well as describing individual variances in these aspects. Subsequently, the “Discussion” section delves into the results and practical implications, and the final section draws conclusions.

Literature review

Safety of ride-hailing services

Safety, the fundamental criterion in the evaluation of ride-hailing services (Kumar et al. 2022), encompasses all potential risks capable of jeopardizing personal belongings, physical well-being, and mental health (Coppola and Silvestri, 2021). It lies primarily in the aspects of vehicles, drivers and online platforms (Acheampong, 2021), consisting of traffic safety, personal safety, property safety and information safety (Duan et al. 2020; Balapour et al. 2020). Among these facets, the paramount concerns of passengers, particularly when ride-sharing, gravitate towards personal safety and privacy (Ko, 2019).

In the wake of recurrent ride-hailing accidents, its service safety draws significant attention from scholars and practitioners, particularly within the realms of safety regulation and risk prevention. Related researches predominantly adopt a qualitative approach. For instance, addressing Uber’s operational security in Europe, Chaudhry et al. (2018) proffered some practical strategies, including the incorporation of mandatory dash cams, distress alarms, in-vehicle lighting, and conspicuous ride-hailing signage, aimed at assuaging passengers’ safety apprehensions. Certain scholars have also highlighted technical risks inherent in ride-hailing services, such as risks related to privacy, legitimacy, and security (Duan et al. 2020; Najjar and Dahabiyeh, 2021; Smith and McCormick, 2019). In response, they have formulated decision-making recommendations directed at local governments and operators (Li et al. 2018). Notably, Sun et al. (2020) proposed a safety regulation strategy for ride-hailing systems involving social media participation. To safeguard the location privacy of passengers in carpooling services, Duan et al. (2020) devised a cloaking region-based order dispatch scheme, minimizing pickup distance and maximizing social welfare while ensuring passenger privacy. Nevertheless, the dearth of quantitative studies from the passenger perspective necessitates further validation of the applicability of these measures. The sustainable growth of ride-hailing services heavily hinges on passenger perception and driver attitude towards passengers (Acheampong, 2021; Acheampong et al. 2020).

Safety perception and prevention of female passengers

How people move (destination, mode, and frequency) is gendered, as confirmed by feminist scholars (Cresswell and Uteng, 2008). Notably, the gender distinctions in travel patterns are particularly conspicuous in both northern and southern regions globally (Law, 1999). For example, women typically take fewer work and business trips than men, yet more shopping trips and trips related to caring for the elderly, children and household chores (Ceccato and Loukaitou-Sideris, 2022; Sagaris and Tiznado-Aitken, 2023). Their activity patterns are characterized by greater diversity and complexity, with accompanied trips and multi-purpose trips being more prevalent. Furthermore, women exhibit a higher reliance on PT than men, and generally express lower perceived safety in public spaces and a greater apprehension about being alone in concealed spaces with strangers, such as in the context of ride-hailing services (Ouali et al. 2020). To this, Gardner et al. (2017) and Kash (2019) have assessed the effect of concerns about victimization on women’s behavior during travel, ultimately concluding that these effects are consistently amplified for women and present variations across individuals and scenarios (Ceccato and Loukaitou-Sideris, 2022). For instance, low-income women often exhibit heightened concerns about victimization compared to their high-income counterparts, as typically residing in unmonitored, poorly lit, and inaccessible neighborhoods (Ceccato et al. 2021; Yates and Ceccato, 2020). Subsequently, these circumstances have perpetuated a stereotype of vulnerability to victimization among many women, rendering them particularly apprehensive in these environments, both in reality and perception (Gardner et al. 2017). And, female victims with previous victimization may be twice as likely to avoid nighttime travel compared to other women (Kash, 2019).

When it comes to preventative measures, various studies conducted in Europe and America (Ceccato et al. 2021; Coppola and Silvestri, 2021; D’ Arbois de Jubainville and Vanier, 2017; Kash, 2019) have outlined the preventative actions adopted by most female passengers, categorizing them into two distinct groups: avoidance behaviors and protective behaviors. Avoidance behaviors include refraining from traveling at night, avoiding destinations with high crime rates, altering travel patterns, or even abstaining from making the trip altogether. Specifically, a study in Australia (Gardner et al. 2017) found that women would not use PT for late-night journeys or during peak hours due to inadequate surveillance. Similar findings were echoed by Kash (2019), indicating that women would reduce such trips to avoid contacting with strangers. As well as, women who have experienced or witnessed victimization are more inclined to take preventative actions, such as traveling with companions or opting for more expensive modes of transportation, or even eschewing travel (Ceccato et al. 2021; Ceccato and Loukaitou-Sideris, 2022).

Protective behaviors primarily involve assuming a defensive posture and utilizing defensive objects. Literature on harassment and travel behavior reviewed by Gardner et al. (2017) revealed that many female passengers would slightly adjust their posture to minimize physical contacts with others. These behaviors include maintaining heightened situational awareness of their surroundings and fellow passengers (Kash, 2019), positioning themselves in close proximity to other women, and using personal belongings to separate from others (Ceccato et al. 2021; Gardner et al. 2017). Notably, there may be gender discrepancies in response to adopting preventative and protective measures. For instance, in high-crime areas such as Mexico, Sao Paulo, and Stockholm, both male and female (especially students) are always ready to defend themselves during travel. While boys primarily prevent robbery and violence by themselves, girls focus on deterring sexual harassment by attracting others’ attention (Ceccato and Loukaitou-Sideris, 2022).

A few studies have also investigated preventative actions commonly taken by female ride-hailing passengers. For instance, in dynamic ridesharing scenarios, they tend to be matched with same-sex passengers and seek additional information, such as the starting and ending points, about their co-passenger (Chang and Wang, 2018; Sarriera et al. 2017). They argue that the built-in functions of online platforms, such as ‘real-time trip tracking’ and ‘ride information queries’, contribute to their heightened sense of safety, particularly in a carpooling context (Young and Farber, 2019; Chen and Lu, 2021). Conversely, a separate survey revealed that over half of the respondents perceived ridesharing as unsafe and were unwilling to carpool with strangers (Acheampong et al. 2020). They harbored widespread concerns that such carpooling behavior could potentially lead to the disclosure of personal details, such as residential locations and activities (Duan et al. 2020). Additionally, female passengers also consider other issues during trips, such as the qualifications of the driver’s identity, any prior criminal record, and whether the driver deviates from the optimal route or engages in risky behaviors, such as speeding and running red lights (Acheampong, 2021). However, these generalized descriptions are mostly presented from an overarching perspective, lacking segmentation. For example, there is still a knowledge gap concerning proactive and reactive prevention measures, as well as the broader expectations of female passengers for the ride-hailing environment.

Summary of the literature findings

To visually present the main contributions of the aforementioned papers, Table 1 categorizes several typical studies on female passengers’ safety perceptions and preventative actions, and summarizes the relevant conclusions from these literatures. They have discussed the effects of passengers’ gender, age, residential community, travel environment, and victimization experiences on travel safety perceptions, with a primary focus on PT mode and fewer studies related to ride-hailing services. Regarding preventative actions, cell phone communication, surveillance devices, and traveling in pairs are considered effective protective behaviors, although their effectiveness may vary depending on individual and situational factors, necessitating further exploration in our study.

Based on the literature summarized in Tables 1 and 2 extracts the relevant factors affecting passengers’ perceptions and prevention actions, which can be categorized into individual characteristics, driver behavior, safety and security, travel conditions, previous experiences, and media attention. This provides a theoretical basis for subsequent investigations. The data in these studies were primarily obtained through interviews or surveys, with the most commonly applied methodologies including factor analysis, structural equation model (SEM), linear regression, and logistic regression analysis. Notably, SEM which integrates regression analysis and latent factor analysis offers a unique advantage in mining latent variables and examining qualitative causal hypotheses, including tests of causal relationships between latent variables and regression of outcome variables (Acheampong et al. 2020). In this study, inductive and factor analysis methods are used to inform the selection of latent variable in the subsequent structural equation modeling. Further, independent sample t-tests and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) are employed to explore differences in variables across various dimensions.

As previously mentioned, existing research on the perceived vulnerability of female passenger has predominantly focused on PT services such as bus, subway, and train. While their safety perception for ride-hailing services are poorly understood, manifesting in two aspects: passenger heterogeneity and the factors contributing to perceived and behavioral differences. As a vulnerable group, female passengers’ safety requirements are often marginalized in actual transportation, particularly in certain developing countries where female participation in transport planning, management, and operation is lacking (Noor and Iamtrakul, 2023). Although some safety measures have been implemented, there remains a discrepancy between the actual safety level provided by the ride-hailing environment through current preventative measures and the perceived safety level of female passengers. Since this perception is influenced by subjective factors such as socioeconomic conditions, personality, travel habits, and previous victimization experiences. Addressing these issues is the primary motivation behind this study, aiming to fill the flaws in previous research. Thus, taking into account the distribution characteristic of ride-hailing accidents in China, this study conducts an investigation into the safety perception and prevention of female passengers through situation-based stated preference. It further analyzes their individual heterogeneity in safety perceptions and preventative actions. The findings lead to the proposal of corresponding preventative measures from proactive and reactive perspectives. The aim is not only to minimize the likelihood of unforeseen incidents but also to transmit a sense of security to passengers, thereby preventing the development of negative and distorted perceptions about ride-hailing services.

Methodology

Data collection

Safety, as a mean of averting peril and harm, can be quantified objectively or subjectively (Acheampong et al. 2020). Objectively measurement involves assessing incident reporting data, such as fatalities or injuries. On the other hand, subjective or perceived safety pertains to the sense of being free from danger or injury, typically captured through empirical data gathered from interviews and questionnaires.

Accidents retrieval

Drawing from data regarding the ride-hailing landscape in China, Didi Chuxing has dominated the market with over 80% share since its inception in 2012 (CNBC, 2021), establishing itself as China’s largest and most popular ride-hailing company, boasting approximately 70 million monthly active users as of December 2022 (Statista, 2023). However, it also witnessed a relatively high number of incidents over the past ten years (Tirachini, 2019). Consequently, utilizing the influential DiDi Chuxing platform as a primary exemplar, this study evaluates the objective safety of ride-hailing through an exploration of pertinent safety incidents. Notably, a search for ‘Didi Chuxing’ on the China Judgments Online platform yielded 7898 criminal judgment documents. According to incomplete data, there were approximately 674 verdicts involving drivers as perpetrators and passengers as victims. The regional distribution of criminal cases is depicted in Fig. 1, revealing a notably high crime rate in southeast China, with over 10 cases reported in about 24 provinces. Among the various provinces in China, Guangdong recorded the highest number of incidents, with a significant 107 cases (15.9%), followed by Sichuan with 61 cases (9.1%). Furthermore, the tally of related accidents escalated annually from 2016 to 2018. The onset of the COVID-19 pandemic precipitated a significant decline in Didi Chuxing usage in 2020, corresponding with a decrease in related accidents.

From the 7898 Didi-related criminal cases, the incidents in each province were identified using the provided keywords, and the top 14 provinces are presented in Fig. 2. These cases mainly involve traffic accidents, illegal gains, intentional offense, sexual assault, indecent behavior, and other violations against women’s will. The incentives behind these crimes can be categorized into six types: monetary gain, sexual gratification, minor disputes, fare disagreements, loading issues, and route disputes. Particularly notable are a series of related incidents over the past ten years involving the victimization of female passengers. However, it is noteworthy that the majority of available information related to sexual harassment in ride-hailing services is rarely reported in resources. Notwithstanding these constraints, the findings synthesized in this section also underscore the fact that sexual harassment in ride-hailing is a matter of global concern, significantly impacting the travel experience of numerous women and girls. In response, many ride-hailing platforms have implemented safety measures. For example, in 2018, DiDi Chuxing announced that its carpool drivers are required to exclusively pick up same-sex passengers during early morning or late evening hours (Al-Heeti, 2018). Furthermore, a number of ride-hailing startups, only serving women, have emerged, such as Chariot for Women (USA), She Cabs (India), and She’Kab (Pakistan) (Tang et al. 2021).

Participants

The preceding section has objectively demonstrated the existence of safety risks to passengers’ persons and property when using ride-hailing services. Whereas, passengers’ perceived safety is recognized as a crucial indicator for evaluating its subjective safety (Chaudhry et al. 2018), with relevant data primarily gathered through investigative methods such as online surveys, intercept surveys, and questionnaires (Tirachini, 2019). Therefore, in order to specifically comprehend the experiences of female passengers, this study employed an exploratory survey design to collect pertinent data through a combination of face-to-face interviews and online questionnaires, with the goal of obtaining first-hand insights and deriving inductive generalizations. Drawing from the factors explored in prior literature (see Table 2) and the accident keywords in Fig. 2, we crafted the questionnaire for this study. It is divided into three parts: individual characteristics, travel habits, and situational inquiries. The survey was conducted in two stages: an on-site survey and an online survey. During the on-site survey, paper questionnaires were randomly distributed to passersby, with the participation of respondents being rewarded with a nominal incentive of 5 Yuan, and the survey time is October 18, 2020. Subsequently, in the formal survey stage, electronic questionnaires (completed exclusively by women) were distributed via Internet survey on relevant websites, offering an incentive of 2 Yuan per person (dispersed after screening and approval). It was open from October 20, 2020 to March 15, 2021. Throughout the survey, these respondents were selected randomly based on their availability and willingness to share their perceptions and experiences regarding ride-hailing services in China. It’s crucial to note that the researcher neither encouraged participation in any way (respondents were unaware of the financial incentives in advance) nor provided any reminders.

Nonetheless, it is imperative to acknowledge the potential challenges associated with employing this sampling methodology, specifically, the presence of selection bias and sampling bias, which is pervasive issue across various sampling techniques. Despite the random selection of target respondents, bias inevitably creeps in due to individuals’ subjective responses. Therefore, in order to mitigate these potential biases, this study draws upon pertinent literature (Acheampong et al. 2020; Ceccato and Loukaitou-Sideris, 2022; Yates and Ceccato, 2020) for solutions to analogous issues. The adopted strategies encompass enlarging the sample size, enriching survey dimensions (including different regions, city classifications, and five socio-demographic characteristics), combining offline and online surveys, and rigorously controlling for a consistent daily survey period. Consequently, a total of 1055 responses were gathered, of which only 753 were complete. The collected questionnaires were further screened through trap questions, reasonableness, and time limits for completion. Following the exclusion of markedly inconsistent and unreliable simples, a final dataset comprising 596 responses was deemed valid for the study. Its size exceeds the minimum sample requirement of 384, as calculated using the sample calculator (calculator.net, 2023), considering a confidence level of 95%, a margin of error of 5%, a female population proportion of 48.6%, and an estimated population size of 472 million ride-hailing users (CNNIC, 2023). This demonstrates the adequacy and representativeness of the 596 samples utilized for subsequent data analysis.

The age distribution of the surveyed group follows a normal distribution, with the majority falling within the 18–25 age bracket, constituting 62.8% of the respondents. This segment is fairly evenly divided between students (47.3%, comprising high school students, undergraduates, and graduates) and practitioners (43.6%, encompassing roles such as civil servants, enterprise employees, and freelancers). The regional distribution of the respondents is depicted in Fig. 3, revealing a distinct concentration in southeastern China, particularly in Chongqing (26.8%), Hunan (6.7%), Guangdong (6.2%), and Sichuan (5.2%). Comparable to the regional distribution patterns observed in Fig. 1 for Didi-related criminal cases, this indicates a certain level of representativeness in the sampled population.

Measurement & tests

Tool and approach

A 5-point Likert scale was employed to score the questionnaire items. Following data collection and importation into the Statistical Package of Social Science (SPSS-26), descriptive statistics, such as mean and standard deviation (SD), were calculated. Analytical statistical tests, including reliability and validity tests for scales, assessment for common method bias, factor analysis, Pearson correlation, one-way ANOVA, independent sample t-test, and presentation by box-whisker plots, were harnessed for meticulous data scrutiny.

Cross statistics

Respondents were tasked with evaluating on the overall perceived safety of ride-hailing services via a Likert scale, ranging from 1 to 5, denoting the following meaning: 1-extremely unsafe, 2-marginally unsafe, 3-neutrality, 4-reasonably safe, and 5-extremely safe. The mean scores for traffic safety (TS), information safety (IS), property safety (PrS), and personal safety (PeS) assigned by 596 interviewees are 2.84, 2.57, 2.73, and 2.42, respectively. Significantly, all these scores fall below 3, signifying that ride-hailing is perceived as marginally unsafe. Table 3 delineates the distribution characteristics of age, education level, income, ride-hailing frequency, and victimization among respondents perceiving unsafe. Notably, they exhibit higher concern regarding personal safety (n = 350), characterized by youthfulness (76.6%, under 26 years old) and modest income (44.9%, less than $308). In the survey on ride-hailing usage, users with infrequent utilization primarily harbor concerns about traffic safety, and there is a higher incidence of individuals who have encountered mishaps related to fare and traffic.

Safety perception score (SPS)

To comprehend specific safety contexts and expectations, respondents were prompted to evaluate their sense of safety using a 5-point Likert scale (1-extremely unsafe to 5-extremely safe) across various ride-hailing scenarios outlined in Table 4. Descriptive statistics, such as means and standard deviations (SD), pertaining to the driver image (DI1-DI4), driver behavior (DB1-DB5), and traveling together (TT1-TT6) components, were presented to capture the respondents’ SPS. The findings revealed that passengers reported heightened unease in scenarios involving DB2 (taking a detour), DB3 (asking privacy), and DB4 (peeping), with the SPS below 2.0. Conversely, passengers perceived safer in scenarios such as TT1 (travelling with friends), TT2 (carpooling with an acquaintance), and TT6 (travelling with children), with the SPS exceeded 4.0.

Subsequently, an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was executed to examine their potential relationships and their effectiveness in describing the content of constructs. For the precise computational procedure, please refer to the literature (Yang et al. 2022), while the outcomes are shown in Table 4. The KMO value for safety perception scale is 0.859, surpassing the threshold of 0.6 (Quy Nguyen-Phuoc et al. 2021), and the Bartlett test also fulfilled the significance criterion (p < 0.001), indicating the suitability of the scale data for EFA. Following the factor analysis, three latent factors with eigenvalues exceeding 1 were retained, collectively explaining 60.673% of the total variance, with the first factor accounting for 20.872%, falling short of the critical threshold of 50% (Podsakoff et al., 2003). Moreover, the factor loadings for each item ranged from 0.593 to 0.874, all falling within the valid range. Finally, the reliability of the factors, denoting the internal consistency among items within a factor, was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha (α) values. The results demonstrated that α values of all factors surpassed the threshold of 0.7 (Urbach and Ahlemann, 2010), all conclusively passing the test.

Preventative Action tendency (PAT)

Given the interplay between safety perception and preemptive action (Wang et al. 2020), respondents were also tasked with choosing from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) for the statements given in Table 5. Descriptive statistics, such as means and SD, were employed to elucidate the respondents’ PAT in terms of mobile phone dependence (PD1-PD6), information attention (IA1-IA6), and Risk avoidance (RA1-RA3). It is evident that across these scenarios in Table 5, the average PAT scores surpass 3.5, signifying the inclination of most passengers to remain cautious and take preventative actions in potential emergency situations during their journeys. Noteworthy instances with relatively high PAT scores include PD3: sharing information, PD4: checking the route, PD6: keeping phones available, IA4: auditing driver identity, IA5: confirming drivers without a criminal history, IA6: focusing on other users’ complaints, and RA2: avoid ride-hailing in remote suburbs, all scoring over 4.0. These represent prevalent preventative actions and risk avoidance behaviors.

Furthermore, the scale data and its structure underwent validation through EFA, as shown in Table 5. The preliminary analysis affirms the suitability of the prevention tendency scale data for EFA (KMO = 0.890, p < 0.001). In the factor analysis, the 15 items comprising the scale are categorized into three dimensions of PAT, collectively explaining 67.106% of the total variance. The primary factor alone elucidates 26.769% of the variance, meeting the critical condition. Notably, factor loadings for all items range from 0.571 to 0.905, above the threshold of 0.5 (Urbach and Ahlemann, 2010). Finally, the Cronbach’s alpha (α) values of all factors exceed 0.7, attesting to their reliability and internal consistency.

Common method bias

In order to investigate the presence of common method bias (CMB) in this survey, Harman’s single-factor analysis was employed to assess the self-reporting measurements. These include respondents’ congruence motives, leniency effects, acquiescence tendencies, and transient emotions, as well as biases related to questionnaire topic characteristics, content, and survey environment. The results of this analysis indicate a total CMB of 26.296%, a value well below the recommended standard of 50% total variance (Podsakoff et al. 2003). Moreover, Pearson correlation analysis revealed no excessively high bivariate correlations (r < 0.90) between constructs (see Table 6), affirming the absence of a significant CMB issue in this study.

Reliability analysis

Composite reliability (CR), convergent validity, and discriminant validity tests were conducted to further validate the dependability of the study’s variables (see Table 6). The results unveiled CR values ranging from 0.82 to 0.92, above the threshold of 0.6 recommended by Urbach and Ahlemann (2010). This indicates the effective representation of all latent constructs by the observed variables. Additionally, with the exception of TT, the average variance extracted (AVE) values for all constructs exceeded the recommended threshold of 0.5. It is worth noting that if the AVE is below 0.5 while the CR exceeds 0.6, the convergent validity of the construct remains satisfactory (Fornell and Larcker, 1981), further supporting the convergent validity of the measurement. Moreover, Table 6 illustrates interrelations among all variables (i.e., DI, DB, TT, PD, IA, RA, and PS), and the square roots (i.e., diagonal cells) of the AVE values for all constructs exceeded the correlation coefficients among the constructs. This denotes the solid discriminant validity of the scale employed in this study.

Data analysis & results

Perceived safety difference

The graphical representations in Fig. 4 present the frequencies of perceived safety scores (ranging from 1-extremely unsafe to 5-extremely safe) among female passengers, segregated by their diverse socioeconomic characteristics and travel experience. These visual depictions yield intriguing evidence of disparities in perceived safety of ride-hailing services across various demographic attributes, including age, income, employment, and usage frequency, and victimization experience. Notably, the distribution of respondents aged over 26 exhibits a negative skew, with the peak shifted towards a substantial rating of 4.0 (indicating a perception of relative safe). It surpasses the mean rating of 3.0 for respondents fewer than 26, thereby suggesting a differential in safety perceptions based on age groups. Analogously, discernible disparities in safety perceptions are observable across other individual attributes. And a divergence in the mode value is discernible among these subgroups.

Individual heterogeneity

Typically, independent sample t-test, Chi-square test, and ANOVA conventionally employed to scrutinize divergences in variables across different dimensions. ANOVA allows for comparisons of means across two or more groups or factors with three or more levels, while t-test is primarily utilized for comparisons between two means. In this study, a combination of independent sample t-test and one-way ANOVA was concurrently applied to conduct a thorough examination of heterogeneity, with the goal of probing the differences of safety perceptions (DI, DB, and TT) and preventative actions (PD, IA, and RA) among female passengers with distinct personal attributes and riding habits.

From a perspective of hypothesis testing, the aim is to obtain compelling evidence by rejecting the null hypothesis in favor of the alternative hypothesis (i.e., rejection-support testing approach), as a conclusion derived from a “rejected” null hypothesis is generally considered more credible than one predicated on an “accepted” null hypothesis (Sohn et al. 2020). Thus, the null hypothesis (H0) posited in this context postulates the absence of significant differences in safety perception and preventative action among female passengers with varying personal attributes, socioeconomic conditions, riding habits, and victimization experiences. In contrast, the alternative hypothesis (Ha) asserts the existence of significant differences in safety perception and preventative action among female passengers characterized by differing attributes. This underscores the potential impact of specific attributes on their safety perception or preventative action.

Prior to conducting ANOVA or t-test, it is imperative to assess the normality and independence of the samples. Utilizing IBM SPSS Statistics enables the simultaneous execution of difference tests and assessments of sample homogeneity, obviating the necessity for preliminary examinations. The homogeneity of variance, as indicated by a Levene statistic p-value exceeding 0.05, can be ascertained. In cases of unequal variances, the significance of the F-test in ANOVA diminishes, necessitating the utilization of Welch’s correction to discern difference. Similarly, corrected t-test outcomes are employed to evaluate the difference test results in the context of unequal variances.

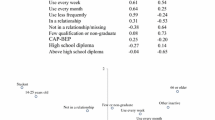

In the ANOVA (Table 7), F values are calculated for each parameter based on key indicators such as degrees of freedom, sum of squares, and mean of squares. The increasing magnitude of the F value conveys a heightened effect on the response value. With a significance level set at 0.05, corresponding to a 95% confidence level, the analysis results disclose that the F value of age-DI is 6.790 (p < 0.001), thereby rejecting H0 and accepting Ha. This signifies significant perception differences of driver image (DI) among female passengers of differing ages, indicating a notable influence of age on DI perception. Similarly, significant effects of passengers’ education level, income status, and ride-hailing usage frequency on DI perception are observed (p < 0.05). Also, education and ride-hailing usage frequency exert a notable influence on PS (p < 0.05). Moreover, substantial perception differences of traveling together (TT) among female passengers across different age groups (F = 4.638, p < 0.01), and variations in risk avoidance (RA) tendencies among groups with differing educational levels (F = 4.899, p < 0.01) are significant.

Subsequently, post-hoc multiple comparisons, commonly employed following significant results from one-way ANOVA, are conducted to compare paired means between groups and identify significant differences within the levels. Here, the outcomes from the LSD (with equal variance) or Tamhane (with unequal variance) multiple comparisons displayed in Table 8 demonstrate noteworthy disparities. For instance, passengers with higher education (graduate or above) exhibit weaker RA tendencies (mean of 3.757), demonstrating greater acceptance of risky rides, and a notably higher perceived safety compared to those with lower education levels (E3 > E1, E3 > E2). Furthermore, among different age groups, women over 40 (A4) are characterized by heightened sensitivity to driver image (DI) and a heightened propensity to travel with companions (mean of 4.120). These findings regarding perception difference align with those of two other safety perception studies (Lee et al. 2017; Park and Garcia, 2019).

Table 9 presents the results of t-tests examining the impact of various factors such as student identity, victimization experience and business trips on their safety perceptions and prevention tendencies. The findings indicate that the t values for student-DI and student-RA are −4.350 (p < 0.001) and −2.126 (p < 0.05), respectively, leading to the rejection of H0 and acceptance of Ha. This suggests significant differences in DI perceptions and RA tendencies between students and practitioners. Specifically, students demonstrate reduced sensitive to driver image (DI) and a stronger inclination toward risk avoidance (RA), with a mean of 4.083 (Table 10), while practitioners show a greater willingness to take risky rides due to their work.

Furthermore, previous victimization experiences also influence female passengers’ DI perceptions (p < 0.001), although they do not significantly impact other perceptions or prevention tendencies. This finding contradicts international evidence, which holds that prior victimization remains a crucial determinant of passengers’ safety perceptions and behaviors (Ceccato and Loukaitou-Sideris, 2022; Yates and Ceccato, 2020; Wang et al. 2020). This disparity may stem from the lower percentage of respondents in this study reporting victimization experiences (i.e., 20.1%, as indicated in Table 3), making it challenging to find victims. Similarly, due to the unequal distribution of the random samples—where only approximately 13% of passengers have long-distance travel experience—there is no significant difference in prevention tendencies between passengers with or without business travel experience. Moreover, environmental factors such as poorly maintained areas, unclean spaces, inadequate lighting, and desolate areas are shown to heighten feelings of insecurity among women (Ratnayake, 2016). Accordingly, the residential environment is found to impact passengers’ perceived safety (PS, p < 0.05) and their proclivity for preventative actions (RA, p < 0.001) in this study. For instance, female riders living in areas below the county-level exhibit a stronger inclination toward risk avoidance (mean of 4.184) and a weaker perceived safety (mean of 2.555) compared to those residing in municipal districts (Table 10).

To visualize the heterogeneity test outcomes outlined in Tables 7 and 9, we adopted box-whisker plots (BWP) to tangibly depict the distribution of responses with significant differences. Mainly, influenced by individual characteristics (age, education, income, residence conditions, student status, business travel status, victimization status, and ride-hailing frequency), the distribution of seven descriptive variables pertaining to safety perception and prevention, namely, DI, DB, TT, PD, IA, RA, and PS were given. And 15 BWP were drawn using Origin, as presented in Fig. 5.

In the BWP, we mainly considered the means, represented by the distinctive black dots, delineating the variations across different groups within each variable. Take age groups as an illustrative example, the mean values reveal a decline in passengers’ safety perception of driver image (DI) and an increase in inclination towards traveling together (TT) with increasing age. Notably, for women over the age of 40, this observed trend becomes even more pronounced with a mean of 2.459 for DI and 4.120 for TT (as indicated in Table 8). This phenomenon elucidates why older individuals tend to harbor a heightened sense of apprehension, despite statistical evidence indicating that younger individuals are more susceptible to victimization (Ceccato and Loukaitou-Sideris, 2022). Likewise, as passengers’ educational attainment increases, their safety perception towards DI and total perceived safety (PS) also increases correspondingly. It is worthy to mention that the groups exhibiting the highest mean ratings for DI and PS all hold postgraduate or higher degrees. This corroborates the findings of Acheampong et al. (2020) that individuals with higher education levels are more amenable to emerging things and thus more willing to trust the safety of ride-hailing services. It further illustrates the ability of knowledge to broaden perspectives and mitigate cognitive biases.

Furthermore, the variance in income among female passengers significantly impacts their DI perception, albeit showing not significant effect on other safety perceptions and preventions during ride-hailing. This may be correlated with the relatively minor income gap observed among female respondents in this study, 47.3% of who are students with a monthly income of less than $308 (as indicated in Table 3). Their perceived safety levels related to DI (mean of 3.235, see Table 8) are notably higher than those of female passengers belonging to other income brackets. Similar to the findings of Alemi et al. (2018), we also proved that female passengers using ride-hailing more frequently exhibit heightened trust in the service and evince greater confidence in its safety. This association is mostly related to their daily travel habits, as habitual behaviors can somewhat erode vigilance and elevate the travel experience. However, it is important to acknowledge that the highest average ratings are not exceedingly high, standing at 3.185 (DI) and 2.799 (PS) respectively. This may be attributed to the incomplete and unreliable nature of the regulatory system and infrastructural facilities within ride-hailing services themselves.

In contrast to practitioners, students are less sensitive towards driver image, but more perceptive of travel environment and more aware of safety precautions. Accordingly, their inclination towards risk avoidance (RA) is higher, indicated by a mean of 4.083 (see Table 10). This discovery is analogous to the findings advanced by Ceccato and Loukaitou-Sideris (2022), indicating that students are more inclined to adopt avoidance behaviors in response to the fear of victimization. Whereas certain risk-taking behaviors exhibited by practitioners (e.g., late-night ride-hailing) are mostly tied to the demands of their jobs, as post working overtime at night, the majorities opt for ride-hailing or taxi services, except for those driving themselves.

Notably, female passengers who have encountered victimization exhibit a heightened concern about driver image, directly influencing their overall safety perception. This finding is closely linked to the fact that most victimization experienced by female ride-hailing passengers can be attributed to drivers, as evidenced in Fig. 2. Additionally, Fig. 5 expounds that female passengers residing in county-level cities manifest lower overall perceived safety and higher tendency towards risk avoidance than their counterparts inhabiting municipal district cities. This is mainly evidenced by their preference for traveling with companions and their aversion to engaging in risky behaviors, such as traveling alone at night or using ride-hailing services in suburb areas.

Discussion

Ride-hailing user groups

According to our investigation in China, we have discerned that the majority of ride-hailing users are middle-aged and young women, highly educated and residing in urban areas, aligning seamlessly with the empirical utilization of ride-hailing services. This revelation mirrors findings unearthed in analogous research those conducted in other cities, including Madrid, Spain (Gomez et al. 2021), California, USA (Alemi et al. 2018), and Canada (Tirachini, 2019), indicating the prevalent adoption of ride-hailing services among the relatively youthful and erudite populace. Among our respondents, the number of respondents with victimization experiences is relatively small, accounting for only 20.1% of the overall sample, as indicated in Table 3. This is due to the fact that our survey did not specifically target victims and the generally low crime rate associated with ride-hailing services in China. By contrast, it is evident that our survey would align more aptly with countries that lack robust regulations governing ride-hailing platforms and companies, such as Egypt, India, Spain, and Sweden (Chaudhry et al. 2018), as well as certain cities with relatively high passenger victimization rates, such as Mexico City, Sao Paulo, and Lagos (Ceccato and Loukaitou-Sideris, 2022).

Safety perception

During ride-hailing, the verbal and behavioral cues exhibited by the driver serve as the most perceptible yardstick for female passengers to gauge the safety quotient of this service. Among the driver’s common behaviors, they display heightened sensitive towards instances of unauthorized detours, privacy inquiries, and intrusive conduct. This is consistent with the survey findings in Ghana conducted by Acheampong (2021). Generally, when using ride-hailing services accompanied by a companion, such as a friend, family member, or even a child, female passengers tend to perceive a greater sense of security. This affirms the positive impact of companionship on perceived safety. Accordingly, when engaging in dynamic ridesharing, female passengers show heightened willingness to carpool with same-sex passengers, a trend that corroborates findings elucidated by Sarriera et al. (2017).

As expected, significant perception differences emerge among female ride-hailing passengers with diverse individual attributes. Specifically, compared with their younger counterparts, middle-aged women (aged >40) are more sensitive towards drivers’ image attributes, including age, gender and appearance. Also, they display a predilection for traveling with companions. Still, statistical analyses reveal that young individuals are more susceptible and prone to victimization (Ceccato and Loukaitou-Sideris, 2022). Furthermore, it has been substantiated that transit and neighborhood environments exert a substantial influence on women’ safety perception and behavior. Instances of poorly maintained and unclean areas, deficient lighting and desolate streets, as well as unsupervised and inaccessible communities easily evoke feelings of unease. Generally in China, students who undergo regular safety education exhibit strong safety awareness, resulting in a heightened risk perception and increased awareness of safety precautions compared to practitioners. Paradoxically, this heightened safety consciousness is coupled with a greater likelihood to opt for ride-hailing services. Moreover, as their education level increases, so does their overall perceived safety of the services, including willingness to engage in riskier rides. This finding is consistent with previous research in Boston, USA, and Madrid, Europe (Lee et al. 2017; Gomez et al. 2021).

Notably, low-income women care more about drivers’ image attributes than their high-income counterparts during ride-hailing. Interviews reveal that a majority of low-income women reside in communities with poor environmental conditions, inconvenient transportation, and inadequate monitoring. This exactly explains their heightened sensitivity to actual travel circumstances, aligning with Ceccato and Loukaitou-Sideris’s (2022) exploration of safety perception disparities among different income groups globally. Likewise, women residing in sub-county level cities feel relatively insecure during ride-hailing, coupled with a stronger desire to safeguard personal information and property safety. This concurs with an international study positing that social disorder and neighborhood context significantly impact residents’ safety perception (Ceccato et al. 2021). Prolonged residence in such communities tends to foster a “negativity bias”, where individuals unconsciously fixate on negative information, generating negative emotions.

Additionally, our research reveals that passengers’ dependence on ride-hailing could diminish their perception of associated risks and increase overall perceived safety (PS). Passengers engaging in a high proportion of ride-hailing trips are more inclined to persist in using this service, mirroring a similar pattern observed in Madrid and Sweden (Gomez et al. 2021; Ceccato et al. 2021). Habitual and regular ridership, to some extent, mitigates individuals’ vigilance and moderates travel expectations, thereby enhancing their overall travel experience. Factors such as frequent business trips, and previous victimization (Yates and Ceccato, 2020), further influence female passengers’ inherent impression of drivers (DI), impacting their direct safety perception within this travel pattern.

Preventative action

As the study conducted by Wang et al. (2020) in China, women who perceive a high level of risk are more likely to adopt behaviors to mitigate these risks. This has prompted our further investigation into the preventative actions adopted by female ride-hailing passengers. Of these behaviors, a prevalent approach involves reliance on mobile phones to verify the driver’s identity, peruse complaints from other users, review driving routes, and get in touch with others. Additionally, ride-hailing specific information, encompassing accident reports, driver status, and recent comments and feedback from other users, also attract passengers’ attention, aiding them in assessing the driver’s reliability. To this, Guo et al. (2019) and Acheampong (2021) have drawn similar conclusions, emphasizing that passenger’ fears and concerns are largely influenced by news media coverage of ride-hailing accidents. However, it is indisputable that social media engagement plays a positive role in supervising ride-hailing safety. Moreover, in a concerted effort to preclude victimized incidents, the majority of female passengers (74%) engage in risk-averse behaviors, such as avoiding solo ride-hailing trips during nighttime, particularly to and from remote areas. These findings have also been corroborated in earlier studies on residents’ mobility in Italy (Coppola and Silvestri, 2021), France (D’ Arbois de Jubainville and Vanier, 2017), and Sweden (Ceccato et al. 2021).

Undoubtedly, notable disparities in risk prevention strategies also exist among various demographic groups. Recent literature suggests that female victims are more inclined to undertake preventative measures compared to women not victimized previously (Ceccato and Loukaitou-Sideris, 2022; Yates and Ceccato, 2020). For instance, they tend to travel together and avoid nighttime excursions (Kash, 2019). Our findings fail to confirm this, concluding only that female passenger who have been victimized harbor heightened concerns regarding drivers’ appearance, and habitually observe their demeanor and actions during the journey. This inclination can be attributed, to some extent, to prevalent accounts of ride-hailing accidents where drivers are commonly the main perpetrators (Fig. 2), leaving a lasting negative impression on passengers. Concerning age differences, we find that women over the age of 40 have the strongest preference for traveling with companions, be it friends, family members, or even children. This tendency is closely linked to their engagement in caregiving trips for the elderly and children, as well as errands.

Furthermore, in comparison to students, practitioners demonstrate a higher inclination to undertake risky ride-hailing trips due to occupational demands, such as ride-hailing alone after working overtime or in remote suburbs. These findings mirror the outcomes of a prior study conducted in Boston, which highlighted students’ adoption of avoidance strategies due to their fear of victimization (Ceccato and Loukaitou-Sideris, 2022). However, in sparsely populated European cities such as Greenland, Iceland (Tang et al. 2021), and Ile-de-France (D’ Arbois de Jubainville and Vanier, 2017), students residing in the suburbs cannot entirely avoid such perilous behaviors unless commuting to and from school in private vehicles. And, as education levels and knowledge expand, their perceptions tend to become more objective and less biased, relatively more receptive for risky ride-hailing endeavors. The development status of the residential city also significantly influences the risk-averse behaviors of female passengers. Women residing in remote Chinese cities, marked by scant security personnel and insufficient surveillance equipment, tend to travel accompanied and actively avoid risky rides, such as ride-hailing alone at night or to suburb locals. This substantially restricts their travel activities and could potentially curtail their mobility initiative.

Practical implications

Upon conducting inductive analysis and comparing the findings with international research, it is evident that certain aspects of female passengers’ safety perceptions and preventions during ride-hailing exhibit homogeneity, while others display heterogeneity. And some passengers seem to possess a distorted view of the actual risks associated with ride-hailing. For instance, women who have been victimized or harbor negative cognitive biases tend to magnify the impact of real risks on their perceived safety. Consequently, to address the disparity between female passengers’ perceived safety and the actual safety of ride-hailing services, we proposed diverse countermeasures to manage and mitigate ride-hailing safety incidents. Meanwhile, from female passengers’ standpoint, enhancements have been proposed for the Situational Crime Prevention Framework (Kash, 2019) enhancements have been proposed for preventative actions and, in turn, augmenting their safety perception.

As previously delineated, driver’s physical appearance, emotional state, driving proficiency, and driving behaviors constitute the most immediate criteria for female passengers when formulating safety assessments. This revelation can guide ride-hailing platforms towards refining driver entry standards, intensifying identity verification, and scrutinizing vehicles’ safety performance. It aims to mitigate security vulnerabilities, including drivers counterfeiting certificates, identity swapping, and suboptimal vehicle functionality. Numerous countries have already witnessed positive outcomes following the implementation of such provisions (Smith and McCormick, 2019, Kumar et al. 2022). Also, it is imperative for platforms to regularly update training and educational systems. These should evaluate drivers’ psychophysical fitness, instill safe driving behaviors, and provide instruction on relevant behavioral norms, risk perceptions, and safety consciousness (Ko, 2019; Liu et al. 2022). For example, drivers should obey traffic rules, eschew aggressive driving, refrain from probing into passengers’ privacy, abstain from grievances, and maintain composure. Equally pivotal is the enhancement of the bidirectional rating system employed by ride-hailing platforms. Establishing a reward-punishment mechanism and prioritizing user feedback and comments are critical elements of this process (Chaudhry et al. 2018). This feedback loop not only safeguards passengers’ rights effectively but also serves as a form of supervision for drivers. And, it provides valuable information for potential users considering the service.

Given the sensitivity of passengers’ perception of the ride environment, ride-hailing operators should invest in improving in-vehicle visibility and developing real-time monitoring systems. The aim is to proactively ensure safety of passengers, particularly women traveling alone late at night. The platform can recommend ride-sharing services with same-sex passengers and collaborate with law enforcement to bolster remote monitoring, accompanied by relevant voice alerts. Incorporating environmental and gender considerations into transport policies, planning, and management assumes paramount importance, especially in developing countries (Noor and Iamtrakul, 2023). Scandinavian countries, for example, prioritize well-lit environments in streets and vehicles due to the long dark winters (Ceccato et al. 2021). Remote suburban areas should contemplate augmenting security personnel, fortifying security forces, and enhancing surveillance facilities.

Acknowledging the heightened reliance of female passengers on mobile phones, ride-hailing vehicles should be equipped with power banks and wireless networks to ensure mobile phone availability, assuaging anxiety. Concerns surrounding the safety of alone ride-hailing trips, particularly during late-night hours, may be mitigated by the development of a platform system exclusively pairing female passengers with female drivers. This initiative holds significance, particularly in Europe and America, where some remote commuters face safety risks walking to public transportation (Cats et al. 2022). Also, as technology advances, the advent of driverless ride-hailing services emerges as the ultimate goal. This transition promises passengers both freedom and safety during rides, eliminating concerns about drivers.

Additionally, we supplement the Situational Crime Prevention Framework (Natarajan et al. 2015) from the victim perspective, offering reactive preventative measures tailored for female passengers, as outlined in Table 11. On one front, through intelligent software to disseminate pertinent safety information and highlight the in-built features in ride-hailing vehicles empowers female passengers to cultivate heightened awareness of prevention and control. On the other hand, the dissemination of information about ride-hailing accidents serves to mitigate passengers’ negative biases towards the service. This includes informing users about the probability of safety risks associated with ride-hailing and making crime statistics readily available on the platform, among other transparency measures. Furthermore, to alleviate the impact of gender inequality on female mobility, particularly in terms of avoidance behavior, transport planners and operators should earnestly implement the proactive interventions mentioned earlier. These interventions have been identified as the most effective and efficient means to achieve the overarching goal. Additionally, the nation must enact stringent legislation and ensure justice to compel ride-hailing organizations to operate more safely and reliably.

Limitations

While this study has yielded valuable insights, it is essential to acknowledge certain limitations. A notable constraint lies in the fact that our questionnaire survey was conducted among all female ride-hailing passengers in China, rather than exclusively focusing on those who had experienced victimization. Consequently, the sample size of respondents with prior victimization experiences remains modest (20.1%), rendering impact of previous victimization on most safety perceptions and preventions statistically insignificant. Although our findings align with international studies, such as the one conducted by Ceccato and Loukaitou-Sideris (2022), it is imperative to recognize and address these limitations. To enhance the robustness of future scale validation, it is advisable to employ a more diverse and representative sample. Additionally, incorporating a dedicated survey exclusively for victims would facilitate a more comprehensive and nuanced comparison of results. Moreover, certain aspects of our findings resonate with safety issues reported globally, yet others are distinctly shaped by the unique context of China. Building upon this exploratory groundwork, future research should delve into safety issues across various travel modes in different countries. Furthermore, it is crucial to highlight that this paper serves as a sequel to a preceding article (Yang et al. 2022), aiming to analyze individual heterogeneity in safety perception and preventative actions. The next phase of research should consider both individual attributes and latent structural variables to model the intricate relationships among the influencing factors of safety perception and prevention.

Conclusions

A robust ride-hailing system can verifiably enhance users’ safety, be it objectively measured or subjectively perceived, by shielding them from potential dangers or harm. However, the disjuncture between the concrete safety afforded by the ride-hailing environment through preventative measures and the perceived safety of female passengers is a prevailing challenge. Hence, our endeavor delved into the root causes of this deviation, exploring the safety perceptions—encompassing drivers’ image and behavior, and the act of traveling together—and the perception-influenced preventative actions of female ride-hailing passengers in China. Our study revealed that ride-hailing environment, the actual travel situations, and social media engagement exerted palpable influence on individuals’ safety perceptions and preventative actions. Such subjective factors also emerged as primary drivers of perceptual and behavioral differences. Women with low education, humble residence, infrequent ride-hailing use, and past victimization experiences tend to foster a negative bias towards perceived safety. Moreover, prevalent practices such as mobile phone dependency, information attention, and risk avoidance found unanimous agreement. Key manifestations included verifying the driver’s identity, perusing user feedbacks, examining driving routes, connecting with others, and avoiding risky rides. Undoubtedly, these inductive insights serve as guiding lights for subsequent design research on in-built safety features of ride-hailing services and safety prevention research in alternative mobility methods.

Furthermore, founded on these findings, ride-hailing entities can fortify security measures from diverse perspectives, ensuring passengers’ secure mobility while fostering the inclusive and sustainable development of this service. Proactive prevention measures include regulating drivers’ conduct, enhancing vehicle monitoring systems, optimizing in-app safety features, and devising emergency protocols to secure passengers’ travel. In reactive prevention, disseminating safety knowledge and vehicle built-in features elevates passengers’ prevention and control awareness, fostering the adoption of proactive measures. Simultaneously, the publication of related information mitigates users’ negative bias towards ride-hailing safety. Based on these countermeasures proposed in this paper, it aims not only to substantially bridge the gap between the perceived safety of female passengers and the actual safety in ride-hailing and reshape their trust in ride-hailing services, but also to build robust prevention and control awareness, emboldening them to confidently embrace safe behaviors.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Acheampong RA (2021) Societal impacts of smart, digital platform mobility services—an empirical study and policy implications of passenger safety and security in ride-hailing. Transp Policy 9(1):302–314

Acheampong RA, Siiba A, Okyere DK, Tuffour JP (2020) Mobility-on-demand: An empirical study of internet-based ride-hailing adoption factors, travel characteristics and mode substitution effects. Transp Res Part C: Emerg Technol 115(C):1–22

Ajayi AP (2020) Uber: examination of socio-economic situation of its clienteles and security components in Lagos. J Transp Secur 13(1-2):117–131

Al-Heeti A (2018) Uber Rival Didi Limits Rides Based on Gender After Grisly Murder. https://www.cnet.com/news/uber-rival-didi-may-limit-rides-based-on-gender-after-grisly murder/. Accessed 14 June 2020

Alemi F, Circella G, Handy S, Mokhtarian P (2018) What influences travelers to use Uber? Exploring the factors affecting the adoption of on-demand ride services in California. Travel Behav Soc 13:88–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tbs.2018.06.002

Balapour A, Nikkhah HR, Sabherwal R (2020) Mobile application security: Role of perceived privacy as the predictor of security perceptions. Int J Inf Manag 52(6221):102063–102076

calculator.net. (2023) Sample size calculator. https://www.calculator.net/sample-size-calculator.html?type=1&cl=95&ci=5&pp=48.6&ps=472000000&x=Calculate. Accessed 09 Nov 2023

Cats O, Kucharski R, Danda SR, Yap M (2022) Beyond the dichotomy: How ride-hailing competes with and complements public transport. PLoS ONE 17(1):1–17. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0262496

Ceccato V, Langefors L, Näsman P (2021) The impact of fear on young people’s mobility. European Journal of Criminology. https://doi.org/10.1177/14773708211013299

Ceccato V, Loukaitou-Sideris A (2022) Fear of sexual harassment and its impact on safety perceptions in transit environments: a global perspective. Viol Women 28(1):26–48

Chang WL, Wang JY (2018) Mine is yours? Using sentiment analysis to explore the degree of risk in the sharing economy. Electron Commer Res Appl 28:141–158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.elerap.2018.01.014

Chaudhry B, Yasar AUH, El-Amine S, Shakshuki E (2018) Passenger safety in ride-sharing services. Procedia Comput Sci 130:1044–1050. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2018.04.146

Chen A, Lu Y (2021) Protective behavior in ride-sharing through the lens of protection motivation theory and usage situation theory. Int J Inf Manag 61:102402–102416. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2021.102402

Chowdhury S, Wee BV (2020) Examining women’s perception of safety during waiting times at public transport terminals. Transp Policy 94:102–108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tranpol.2020.05.009

CNBC (2021) Didi says it stores all China user and roads data in China. Retrieved from Consumer News and Business Channel. https://www.cnbc.com/2021/07/03/didi-says-it-stores-all-china-user-and-roads-data-in-china.html?&qsearchterm=Chinese%20ride-hailing%20giant%20DiDi%2080%. Accessed 31 May 2023

CNNIC (2023) The 52th Statistical Report on China’s Internet Development. Retrieved from China Internet Network Information Center. https://www.cnnic.net.cn/NMediaFile/2023/0908/MAIN1694151810549M3LV0UWOAV.pdf. Accessed 09 Nov 2023

Coppola P, Silvestri F (2021) Gender inequality in safety and security perceptions in railway stations. Sustainability 13(7):4007–4022

Cresswell T, Uteng TP (2008) Gendered mobilities: Towards a holistic understanding. Gend Mobil 1:1–12

D’ Arbois de Jubainville H, Vanier C (2017) Women’s avoidance behaviours in public transport in the Ile-de-France region. Crime Prev Community Saf 19(3-4):183–198

Duan Y, Gao GJ, Xiao MJ, Wu J (2020) Cloaking region based passenger privacy protection in ride-hailing systems. J Comput Sci Technol 35(3):629–646

Dunckel Graglia A (2015) Finding mobility: women negotiating fear and violence in Mexico City’s public transit system. Gend Place Cult 23(5):624–640

Flor M, Ortuo A, Guirao B, Casares J (2021) Analysis of the impact of ride-hailing services on motor vehicles crashes in madrid. Sustainability 13(11):1–16

Fornell C, Larcker DF (1981) Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J Mark Res 18(1):39–50

Gardner N, Cui J, Coiacetto E (2017) Harassment on public transport and its impacts on women’s travel behaviour. Aust Plan 54(1):8–15

Gomez J, Aguilera-García Á, Dias FF, Bhat CR, Vassallo JM (2021) Adoption and frequency of use of ride-hailing services in a European city: The case of Madrid. Transp Res Part C: Emerg Technol 131:1–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trc.2021.103359

Goodspeed R, Xie T, Dillahunt TR, Lustig J (2019) An alternative to slow transit, drunk driving, and walking in bad weather: an exploratory study of ridesourcing mode choice and demand. J Transp Geogr 79(C):1–12

Guo P, Tang CS, Tang Y, Wang Y (2019) Gender-based operational issues arising from on-demand ride-hailing platforms: safety concerns and system configuration. SSRN Electron J 32604(27):1–34

Kash G (2019) Always on the defensive: The effects of transit sexual assault on travel behavior and experience in Colombia and Bolivia. J Transp Health 13:234–246. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jth.2019.04.004

Ko S (2019) Didi Chuxing: Expansion and Risk Management. SAGE Business Cases Originals, SAGE Publications, London, UK

Kumar A, Gupta A, Parida M, Chauhan V (2022) Service quality assessment of ride-sourcing services: A distinction between ride-hailing and ride-sharing services. Transp Policy 127:61–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tranpol.2022.08.013

Law R (1999) Beyond ‘women and transport’: towards new geographies of gender and daily mobility. Prog Hum Geogr 23(4):567–588

Lee C, Rahafrooz M, Lee OKD (2017) What Are the Concerns of Using a Ride-Sharing Service?: An Investigation of Uber Emergent Research Forum Paper. Paper presented at the Twenty-third Americas Conference on Information Systems. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/328062597

Li Y, Taeihagh A, Jong MD (2018) The governance of risks in ridesharing: a revelatory case from Singapore. Energies 11(5):1277–1298

Liu Y, Gao Q, Rau PLP (2022) Chinese passengers’ security perceptions of ride-hailing services: An integrated approach combining general and situational perspectives. Travel Behav Soc 26:250–269. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tbs.2021.10.009

Madan M, Nalla MK (2016) Sexual harassment in public spaces: examining gender differences in perceived seriousness and victimization. Int Crim Justice Rev 26(2):80–97

Mao H, Deng X, Jiang H, Shi L, Li H, Tuo L, Shi D, Guo F (2021) Driving safety assessment for ride-hailing drivers. Accid Anal Prev 149:1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aap.2020.105574

Najjar MS, Dahabiyeh L (2021) Trust in the ride hailing service of the sharing economy: the roles of legitimacy and process transparency. J Organ End Use Comput 33(6):1–24

Natarajan M, Clarke R, Carcach C, Ponce C, de Sanfeliú MB, Polanco DE, Chávez M, Shi M (2015) Situational prevention and public transport crime in El Salvador. Crime. Science 4(1):1–15

Nguyen-Phuoc DQ, Tran PTK, Su DN, Oviedo-Trespalacios O, Johnson LW (2021) The formation of passenger loyalty: Differences between ride-hailing and traditional taxi services. Travel Behav Soc 24:218–230. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tbs.2021.04.006

Noor S, Iamtrakul P (2023) Women’s access to urban public transport: Toward addressing policy constraints in combating sexual harassment. Transp Policy 137(6):14–22

Ouali L, Graham DJ, Barron A, Trompet M (2020) Gender differences in the perception of safety in public transport. J R Stat Soc Ser A (Stat Soc) 183(3):737–769

Park Y, Garcia M (2019) Pedestrian safety perception and urban street settings. Int J Sustain Transp 14(11):860–871

Podsakoff PM, Mackenzie SB, Lee JY, Podsakoff NP (2003) Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. American Psychol Assoc 88:879–903

Quy Nguyen-Phuoc D, Oviedo-Trespalacios O, Vo NS, Thi Le P, Van Nguyen T (2021) How does perceived risk affect passenger satisfaction and loyalty towards ride-sourcing services? Transp Res Part D: Transp Environ 97(7):102921–102938

Ratnayake R (2016) Association between fear of crime gender, student nationality, and physical features. Environ Behav 1(16):1–16

Sagaris L, Tiznado-Aitken I (2023) New horizons for sustainable transport planning: An analysis of seven years of gender-related research in Chile. J Transp Health 28(3):101544–101558

Sarriera JM, Alvarez GE, Blynn K, Alesbury A, Scully T, Zhao J (2017) To share or not to share: investigating the social aspects of dynamic ridesharing. Transp Res Rec J Transp Res Board 2605(1):109–117

SFCTA (2017) TNCs Today: A Profile of San Francisco Transportation Network Company Activity. Retrieved from San Francisco County Transportation Authority

Smith NC, McCormick E (2019) Uber and the ethics of sharing: exploring the societal promises and responsibilities of the sharing economy. Manag Sustain Bus 27:579–611. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-024-1144-7_27

Sohn W, Jeong M, Jeong K (2020) Theoretical comparative study of t tests and nonparametric tests for final status surveys of MARSSIM at decommissioning sites. Ann Nucl Energy 135:106945–106954. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anucene.2019.106945

Statista (2023) Number of monthly active user number (MAU) of the leading ride-hailing apps in China as of December 2022. https://www.statista.com/statistics/1218000/china-leading-ride-hailing-apps-based-on-monthly-active-users/. Accessed 20 June 2023

Sun Q, Li T, Ma F, Guo X, Wang S (2020) Dynamic evolution of safety regulation of the ridesharing industry under social media participation. Symmetry 12(4):560–580

Tang Y, Guo P, Tang CS, Wang Y (2021) Gender-related operational issues arising from on-demand ride-hailing platforms: safety concerns and system configuration. Prod Oper Manag 0(0):1–16. https://doi.org/10.1111/poms.13444

Tirachini A (2019) Ride-hailing, travel behaviour and sustainable mobility: an international review. Transportation 47(4):2011–2047

United Nations. (2022) Sustainable Development Goals. Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment. Accessed 8 Dec. 2022

UN Women (2017) Safe cities global initiatives. Retrieved from the National Institute for Women (INMUJERES). https://www.unwomen.org

Urbach N, Ahlemann F (2010) Structural equation modeling in IS Research Using PLS. J Inf Technol Theory 11(2):5–40

Wang X, Yuen KF, Shi W, Ma F (2020) The determinants of passengers’ safety behaviour on public transport. J Transp Health 18:1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jth.2020.100905