Abstract

Low business start-ups due to poor entrepreneurial competence among the youth has continued to attract the interest of entrepreneurship educators and practitioners. Previous investigations have explored individual entrepreneurial orientation, with little attention given to entrepreneurial readiness of students from science and technology colleges in Nigeria. This research shortcoming forms the motivation for this study. The study aims to explore the effect of Individual Entrepreneurial Orientation (IEO) components on students’ entrepreneurial readiness for business start-ups. The philosophical approach is framed within the positivist perspective, with a survey of 289 exit-level students as the sample size. The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin test and Bartlett’s test were performed to measure the sample adequacy. Pearson’s correlation and regression analysis were conducted to validate the hypotheses. The results indicated that IEO risk-taking shows insignificant association with the students’ entrepreneurial readiness, while IEO innovation and IEO proactivity show significant association with the students’ entrepreneurial readiness. The study further reveals that there is no gender difference in the students’ entrepreneurial readiness as influenced by IEO towards starting a business. Managerial implication suggests the promotion and development of an entrepreneurial mindset with practical translations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The youth population in Nigeria is said to be about 140 million and estimated at 65% of the total population in 2018 (Ita and Bassey 2022). According to the National Bureau of Statistics (2020), over 120 million youth were unemployed in the same year. Accordingly, about 90% of graduates are faced with the challenge of unemployment annually (Adeniyi et al. 2022). In the third quarter of the year 2022, while the youth unemployment rate stood at 33.5%, the unemployment rate was estimated at 33%, up from 32.5% in 2021; and this is expected to rise to 40% in 2023, and to 44% in 2024 (Sasu 2022)Footnote 1. The high youth unemployment rate may be attributed to the inadequate readiness to engage in entrepreneurial activities. Entrepreneurship is known to increase employment opportunities and economic growth of any nation, including Nigeria (Ilevbare et al. 2022). Besides, the promotion of business start-ups among the youth is evident in the reduction of unemployment and poverty (Koen et al. 2018).

Recent study suggests that increase in unemployment occurs due to individuals’ lack of courage to engage in high-risk activities such as entrepreneurship (Wulandari et al. 2021). Empirical evidence has indicated that risk-taking is associated with successful entrepreneurs (Zaleskiewicz et al. 2020); and innovation is referred to as entrepreneurship, while proactivity is an influential construct of an entrepreneur. Risk-taking, innovation and proactivity are predominant IEO postures that have been demonstrated in assessing entrepreneurial behaviours (Adeniyi 2021; Chow and Hock 2021). Few studies have explored the IEO construct among young people in Nigeria. For instance, through a repeated-measure t-test, Otache et al. (2022) found an increased level of IEO among students of higher education after being exposed to entrepreneurship education. A significant and positive relationship was found between innovation, proactivity, and performance of SMEs (Yunusa et al. 2022). However, a study on women entrepreneurs in the north-western part of Nigeria found that IEO in terms of risk-taking, innovation, and proactivity show an insignificant relationship with women entrepreneurs’ success (Hashimu 2018). An insignificant association was also indicated between IEO risk-taking and students’ entrepreneurial preparedness in Nigeria (Adeniyi 2021). This inconsistency suggests the need for further investigation in identifying essential IEO components that can foster entrepreneurial readiness among young individuals in Nigeria. Extant literature has revealed that risk-taking, innovation, and proactivity are critical factors of entrepreneurial success (Nikitina et al. 2023). A change is therefore required to encourage young individuals in Nigeria to become entrepreneurially ready for business creation. A person with entrepreneurial readiness is believed to be a risk taker in starting a business. Therefore, this study aims to assess the entrepreneurial readiness of the exit-level students at selected science and technical colleges by focusing on the following objectives:

-

1.

Determine the influence of IEO risk-taking on students’ entrepreneurial readiness for business creation.

-

2.

Examine the impact of IEO innovation on students’ entrepreneurial readiness for business creation.

-

3.

Examine the impact of IEO proactivity on students’ entrepreneurial readiness for business creation; and

-

4.

Establish whether IEO reflects any gender differences in students’ entrepreneurial readiness for business creation.

Entrepreneurship construct

Entrepreneurship is a multidimensional concept which is transdisciplinary in nature; and, as such, entrepreneurship has no generally agreed-upon definition (Derera et al. 2020; Ferreira et al. 2017a; Westhead et al. 2011). For example, the economists’ view of entrepreneurship is as an input that is added to land, labour, and capital to extend the theory of production; and to complete the explanation of the four types of income: profit, rent, wages, and interest (Westhead et al. 2011). This school of thought views entrepreneurial activities as the introduction of novelty and innovation to new work practices, new products and services, and new venture creation (Ferreira et al. 2017b; Westhead et al. 2011). Sociologists, on the other hand, believe that entrepreneurship exists within a social context which shapes an individual’s propensity to become an entrepreneur (Westhead et al. 2011; Storey and Greene 2010). The psychological approach explores issues relating to the entrepreneur, the decision-making process, and the choices they make in entrepreneurship (Ferreira et al. 2017b; Westhead et al. 2011). Researchers in this field have also explored personality traits of entrepreneurs and the behaviour of successful entrepreneurs (Ndoro and van Niekerk 2019; Ferreira et al. 2017b; Westhead et al. 2011). Notable traits highlighted in literature are a risk-taking propensity, a strong need for achievement, a locus of control, and a need for autonomy, amongst others (Ndoro and van Niekerk, 2019; Kuratko Morris and Schindehutte, 2015). The socio-psychological approaches consider the context in which the entrepreneur is operating, and its characteristics (Westhead et al. 2011). The researchers argue that some social contexts are likely to promote entrepreneurial behaviour, whilst others are not (Westhead et al. 2011). The socio-cognitive approaches view entrepreneurship from the personality and behaviour of an entrepreneur stemming from both social interactions and personal characteristics (Ndoro and van Niekerk 2019; Storey and Greene, 2010). This approach suggests that the behaviour of individuals changes throughout their life, with their interactions with specific reference groups in different social contexts shaping their personalities (Ndoro and van Niekerk 2019). However, this approach acknowledges that personality traits may be difficult to change (Kuratko et al. 2015; Westhead et al. 2011). This study draws from the aforementioned theoretical approaches of entrepreneurship to explore the entrepreneurial readiness of the graduating students. The study argues that psychological attributes or cognitive factors associated with an individual must be stimulated to promote entrepreneurship.

Scholarships in entrepreneurship education have emphasised various factors that contribute to the development of a nascent entrepreneur. Of utmost importance is the entrepreneurial orientation of an individual (Sanchez 2013; Koe 2016). Entrepreneurial orientation has been defined as a company’s ability to engage in entrepreneurial behaviours that reflect innovation, proactivity, risk-taking, competitive aggressiveness, and autonomy, leading to change in the business space (Voss et al. 2005). It has been advanced that the meaning and dimensions associated with entrepreneurial orientation lack significant difference from the representation of individual entrepreneurial orientation, because the features of an entrepreneurial organisation also apply to individuals (Gabriel and Kobani 2022). Based on this premise, entrepreneurial orientation refers either to a company’s decision-making process to act entrepreneurially, or to an individual’s personality traits, attitudes, and attributes related to entrepreneurial activities (Eniola 2020; Covin et al. 2020). Accordingly, the components of IEO such as risk-taking, innovation and proactivity have been found to increase entrepreneurial activities of individuals (Nikitina et al. 2023). Moreover, the study of entrepreneurial orientation at the individual level has proven beneficial to future business owners (Bolton and Lane, 2012; Goktan and Gupta 2015); and this has given rise to the concept of individual entrepreneurial orientation (IEO).

Literature review

Entrepreneurial orientation

Miller (1983) views entrepreneurial orientation as the attributes and philosophy of a company measured by top-management decision-making strategies on entrepreneurial goals. Luu and Ngo (2019) state that EO is the chain of entrepreneurial behaviours of a business when introducing new production techniques, new processes; when manufacturing a new product line, and when accessing new market opportunities. Adebayo (2015) has described EO as the dynamic components and structure of a company when moving from a conservative orientation to one fully entrepreneurial. Lyon et al. (2000) established that EO comprises the process and decision-making attitudes of an entrepreneur when engaging in entrepreneurial activities. Accordingly, these processes and components have been placed into various entrepreneurial categories, such as risk-taking, proactivity, innovation, aggressive competition, and autonomy (Covin et al. 2020). In addition, Gabriel and Kobani (2022) affirmed that EO involves a set of distinct but related entrepreneurial components embedded in qualities of risk-taking, innovation, proactivity, competitive aggressiveness, and autonomy.

These dimensions of EO have paved the way for the determination of EO at the individual level. In addition, Bolton and Lane (2012) argued that EO can be determined at an individual level considering its multiconstruct components. This underscores the importance of IEO as a behavioural phenomenon driving the entrepreneurial quest (Bolton and Lane, 2012).

Individual entrepreneurial orientation constructs

IEO is seen by Bolton and Lane (2012) as representing entrepreneurial cognitive traits such as risk-taking, innovativeness, and proactivity. IEO emphasises individuals’ orientation of activating these skills to make business decisions. The potential of risk-taking ability, innovation, and proactivity has been strongly linked to entrepreneurial success (Koe 2016). Furthermore, IEO is a behavioural component of entrepreneurship for entrepreneurial pursuit (Bolton and Lane, 2012). This assumption underscores the determination of these skills at individual level for nascent entrepreneurs.

Risk-taking

Risk-taking is the ability to make decisions in the face of information shortages. Risk-taking activities involve borrowing heavily for business purposes, entering unknown markets, and committing a huge percentage of economic resources to a project with uncertain results (Adebayo 2015). Risk-taking may be viewed as the extent to which an individual is willing to make a strong business commitment, which justifies the nature of an entrepreneur to engage in bold rather than cautious actions (Gabriel and Kobani 2022). Previous research has shown that successful entrepreneurs often assume risky actions, and also adopt planning and forecasting strategies to limit uncertainty (Covin et al. 2020). Risk-taking ability is a critical entrepreneurial attribute for business creation. Accordingly, risk-taking skills have been found to increase innovation for business (Craig et al. 2014).

Proactivity

Proactivity is the process of projecting or anticipating, and responding to future demands (Lawan and Fakhrul 2015). Proactivity refers to a forward-looking step and opportunity-seeking perception which deals with the introduction of new products and services ahead of competitors; also acting in expectation of future needs to create a change in the business environment. The construct of proactivity as a component of EO has been well explored in the field of entrepreneurship scholarship (Bolton and Lane 2012; Luu and Ngo 2019; Eniola 2020).

Innovation

Innovation is a key characteristic of a successful entrepreneur. Innovation refers to the demonstration of new ideas, unique originality, and creative improvement in existing products or services; also, in the manufacturing of new products. Innovation involves building on existing ideas to create improved business; while disruptive innovation requires new skills or ideas which may leave existing skills outdated (Gabriel and Kobani 2022). Innovation is a key component required for business enterprise in achieving entrepreneurial success. This is because innovation is associated with new ideas, new products, and new technology.

Nexus between EO and IEO

While EO is associated with the assessment of entrepreneurial behaviours of firms, IEO could be described as the measure of EO at the individual level. It should be noted that risk-taking, innovation, and proactivity are the most investigated dimensions of EO and IEO in entrepreneurship literature (Robinson and Stubberud 2014; Koe 2016; Nikitina et al. 2023). In similar vein, risk-taking, innovation, and proactivity are the most predominant components shown in existing studies of EO as having a valid and reliable impact. However, most of these investigations have measured IEO against entrepreneurship education and business performance (Lumpkin and Dess, 2001; Aminu 2016; Shamsudin et al. 2017; Bandera et al. 2018, Covin et al. 2020). There is limited research on the link between IEO and students’ entrepreneurial readiness, particularly among students of science and technology colleges in Nigeria. The low level of business start-ups among young minds in Nigeria necessitates the urgent need to assess the most stimulating IEO posture towards starting a business. Therefore, this study aims to determine the impact of risk-taking, innovation, and proactivity on students’ entrepreneurial readiness at selected science and technical colleges in Nigeria.

Entrepreneurial readiness

Entrepreneurial readiness has been cited as an individual’s ability or willingness to take entrepreneurial action (Coduras et al. 2016). “Entrepreneurial readiness is an individual’s cognitive attributes of capability and willingness to direct behaviour in an entrepreneurial context”. In similar vein, entrepreneurial readiness is measured by an individual’s overall ability to respond to entrepreneurial activities (Darmasetiawan 2019). This suggests that entrepreneurial readiness is a collection of cognitive attributes required for entrepreneurial success (Pratomo et al. 2018). Various studies have been conducted to demonstrate the relationship between IEO and entrepreneurial readiness. This refers to technological readiness and IEO (Penz et al. 2017), together with IEO and readiness for change (Kurniawan et al. 2017; Soetjipto et al. 2022), and instrumental readiness and EO (Dakhan et al. 2021). It is important to state that the investigation on the effect of IEO dimensions (in terms of risk-taking, innovation and proactivity) on students’ entrepreneurial readiness in Nigeria is underexplored.

IEO, entrepreneurial readiness, and hypotheses formulation

A considerable number of studies have examined the various dimensions of IEO and entrepreneurial readiness. For example, Ebrahim and Schøtt (2011) empirically found that risk-taking propensity is a predictor of entrepreneurial readiness. Through the lens of the theory of planned behaviour (ToPB), Iqbal et al. (2012) demonstrated that entrepreneurial perception influenced university students’ readiness to take risks and to overcome business challenges. Braum and Nassif (2023) also discovered that individual entrepreneurial orientation significantly and positively influences entrepreneurial readiness. In addition, entrepreneurial personality was found by Saputri et al. (2019) to significantly influence entrepreneurial readiness. Recently, Kumar et al. (2021) found that risk-taking, innovation, and proactivity positively and significantly influenced entrepreneurial intentions of entrepreneurship and management students in Indonesia. IEO dimensions (risk-taking, innovation, and proactivity) have also been found to significantly impact entrepreneurial intention among university students (Suartha and Suprapti 2016; Dakhan et al. 2021). To this end, we therefore hypothesized that:

Ha1: IEO risk-taking has a significant effect on students’ entrepreneurial readiness for business creation.

Ha2: IEO innovativeness has a significant influence on students’ entrepreneurial readiness for business creation.

Ha3: IEO proactivity has a significant impact on students’ entrepreneurial readiness for business creation.

Demographic and psychological characteristics have been identified to determine various attitudes and behaviours. Previous studies have indicated that a demographic factor such as gender is a measurable construct of IEO development (Goktan and Gupta, 2015; Suartha and Suprapti, 2016). Suartha and Suprapti (2016) examined the relationship between IEO and entrepreneurial intention of university students in Indonesia. The result shows that male students have a higher mean score of IEO than their female counterparts; however, there is no significant difference between male and female entrepreneurial intention. Goktan and Gupta (2015) explored sex, gender, and IEO of men and women from the United States, Turkey, Hong Kong, and India. The scholars found that in these countries men rather than women are strongly related to IEO. Another related study revealed that female entrepreneurs are more proactive than male entrepreneurs; while there is no gender difference in risk and innovativeness (Jelenc et al. 2016). Based on these findings we formulated that:

Ha4: IEO has significant gender differences in entrepreneurial readiness for business creation.

Previous study has shown that risk-taking, innovation, and proactivity have significant impact on the establishment and performance of small businesses (Rahaman, et al. 2021). However, Ibrahim and Lucky (2014) noted that the components of IEO such as risk-taking, innovation and proactivity are lacking among young people in Nigeria. In similar vein, Aminu (2016) asserted that lack of integration of IEO propensities such as risk-taking, innovation, and proactivity in entrepreneurship programmes is one of the challenges of entrepreneurship education in Nigeria, especially in TVET institutions. To this end, Koe (2016) suggested that future research is needed to examine entrepreneurial orientation at individual level through the design of an entrepreneurship curriculum. One of the motivations of this study is to determine the influence of IEO risk-taking, innovation and proactivity on students’ entrepreneurial readiness for business creation in Nigeria.

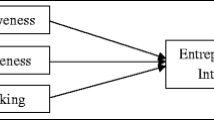

Conceptual model

Figure 1 shows the relationship between IEO in terms of risk-taking, innovation, proactivity, and entrepreneurial readiness. The model also indicates the gender impact in the relationship between IEO and entrepreneurial readiness. The conceptual model was designed to determine the contributions of IEO dimensions to entrepreneurial readiness of young minds in Nigeria.

The model demonstrates the interlink between risk-taking and entrepreneurial readiness denoted as H1, the relationship between innovation and entrepreneurial readiness is denoted as H2, while the relationship between proactivity and entrepreneurial readiness is indicated as H3, and gender was used as a control variable moderating the relationship between IEO and entrepreneurial readiness, which is indicated as H4.

The study context

In a developing context such as Nigeria, the concept of IEO has been examined to prepare young individuals for future work. However, most of the studies have concentrated on both entrepreneurial orientation and entrepreneurial intention of companies’ performance (Alarape, 2013; Ibrahim and Lucky, 2014). Conversely, few studies have been conducted on the contribution of IEO to students’ entrepreneurial readiness (Aminu, 2016; Abubakar and Yakubu, 2019; Gabriel and Kobani, 2022). On one hand, Gabriel and Kobani (2022) evaluated individual entrepreneurial orientation and community development in Nigeria. The authors argued that IEO, such as community development, has the potential to stimulate development in the areas of healthcare, the rural industry, education, and social network of the community. On the other hand, Aminu (2016), and Abubakar and Yakubu (2019) found that IEO is a moderating factor in entrepreneurship education and students’ entrepreneurial intention towards venture creation in Nigeria. It is worthy of note that none of these studies empirically considers the dimensions of IEO on students’ entrepreneurial readiness for business creation. Moreover, the determination of entrepreneurial readiness in relation to risk-taking, innovation, and proactivity among students of science and technology colleges in Nigeria is underexplored. This has led to low business creation and increasing graduate unemployment in the country.

Entrepreneurship education in TVET Colleges in Nigeria

In 2004, due to low business start-ups and increasing youth unemployment, the Nigerian government introduced entrepreneurship education into all science and technical colleges. It is expected that TVET will supply young minds with technological skills in various trades, while entrepreneurship education will provide entrepreneurial skills for business start-ups (Fagge, 2017). Despite the concerted efforts of the Nigerian government to empower graduates of TVET colleges for employment creation and self-employment, the institutions are not performing well (Okolie et al. 2019). Previous scholars have argued that the entrepreneurship curriculum in TVET colleges lacks appropriate entrepreneurship programmes for business creation (Ladipo et al. 2013: Maigida et al., 2013). The entrepreneurship curricular content in most TVET colleges in Nigeria is deficient in workshop programmes and practical engagements (see example in Table 1). The table below shows the entrepreneurship curriculum content of Lagos State Technical Vocational Education and Training.

Table 1 above shows that more than 90% of the course content is taught theoretically. This is in line with the position of Ladipo et al. (2013) and Vincent et al. (2021) that the curriculum content of TVET institutions in Nigeria is deficient in practical translations. Thus, the students lack the key entrepreneurial skills such as risk-taking ability, innovation, and managerial competence to create and grow a business. Oviawe (2010) affirms that properly planned entrepreneurship programmes will ensure self-employment and increase job creation amongst the youth. The entrepreneurial characteristics of risk-taking, innovation, and proactivity which are part of the IEO concept have not been fully harnessed in entrepreneurship education (Ferreira et al. 2012). Koe (2016) emphasized that entrepreneurship education should stress students’ IEO ability in order to increase their entrepreneurial readiness.

Methods

This study is grounded in the positivist philosophical assumption that the construction of knowledge is subject to the law of cause and effect in which scientific principles are applied (Wilson, 2014). The positivist view allows for the adoption of quantitative research design as demonstrated in much entrepreneurship literature (Sánchez 2013; Adeniyi et al. 2022). The case-study research technique informs the assessment of exit-level students from three TVET colleges in Lagos Metropolis of Nigeria. It is important to state that some of the students are already self-employed with small-scale businesses as at the time of this survey. The independent variables (risk-taking, innovation, and proactivity) were measured from the instrument developed by Bolton and Lane (2012) and Vogelsang (2015); while the dependent variable (entrepreneurial readiness) was determined by an entrepreneurial readiness scale developed by Coduras et al. (2016). All the variables had internal consistency that surpassed the required threshold of 0.7 as shown in Table 2. A six-point Likert scale rating strongly disagree, disagree, slightly disagree, slightly agree, and strongly agree was adopted in measuring the students’ entrepreneurial readiness.

Taro’s equation model was helpful in the selection of 301 exit-level students from the 1212 sample frame. Questionnaires were administered to elicit required information from the students. Of the 301 distributed questionnaires, 289 were duly filled in and returned, which suggests a 98% response rate. The statistical tool, SPSS version 25, was utilized in the analysis of the data. Descriptive and inferential statistics such as correlation and regression were adopted in the presentation of results and test of hypotheses.

Analysis

The variables were subjected to both validity and reliability tests to determine their internal consistency and sample adequacy. Table 2 shows the coefficient values for a factor analysis.

As shown in Table 2, all the variables indicated a reliability value between 0.76 and 0.90, which surpasses the minimum requirement of 0.7 (Wilson 2014). The Keiser–Meyer Olkin, and the Bartlett’s test values revealed that the sample is adequate for both data collection, and significance respectively.

An anti-image correlation was performed to further measure the sampling adequacy of the data, as shown in Table 3.

As indicated in Table 3, the anti-image correlation number denoted as (ª) has 4 variables that meet the required measure of sampling adequacy, with coefficients greater than the minimum threshold of 0.5. This implies that all the constructs are valid for further analysis.

The presentation in Table 4 depicts the result of the relationship between IEO and entrepreneurial readiness. The correlation effect reveals that all components (risk, innovation, and proactivity) of IEO have significant and positive association with entrepreneurial readiness − IEO risk-taking (r = 0.334, n = 288, p < 0.001), IEO innovation (r = 0.415, n = 288, p < 0.001) and IEO proactivity (r = 0.456, n = 288, p < 0.001). This indicates that IEO is a determining factor of entrepreneurial readiness. IEO proactivity shows the strongest correlation with entrepreneurial readiness.

Test of hypotheses

To test the hypotheses, we conducted a multi-collinearity test to verify the presence or absence of collinearity between the variables.

Table 5 shows that the variance inflation (VIF) of the independent variables was well below 10; and the tolerance values were higher than 0.10 (tolerance > 0.10). Therefore, the variables are free from multi-collinearity, and the results of the regression analysis can be relied upon.

Table 6 revealed the outcome of the regression analysis, with R² value as 0.234, which implies that IEO was able to explain 23.4% variations in entrepreneurial readiness. Further, while innovation β = 0.153, t (287) = 2.200, p < 0.05, and proactivity β = 0.286, t (287) = 3.745, p < 0.05 shows a significant association with entrepreneurial readiness; the standardized beta value of risk-taking β = 0.109, t (287) = 1.769, p > 0.05 shows an insignificant association with entrepreneurial readiness. Therefore, H1 (IEO risk-taking ability has a significant effect on students’ entrepreneurial readiness for business creation) was rejected. However, the significant association between innovation, proactivity, and the students’ entrepreneurial readiness implies that H2 (IEO innovation has a significant influence on students’ entrepreneurial readiness for business creation) and H3 (IEO proactive steps have a significant impact on students’ entrepreneurial readiness for business creation) were accepted.

The presentation in Table 7 shows the gender difference in the students’ entrepreneurial readiness as influenced by IEO for business creation. On one hand, the result shows that risk-taking β = 0.135, t (154) = 1.660, p > 0.05; β = 0.084, t (126) = 0.860, p > 0.05, and innovation β = 0.183, t (154) = 1.916, p > 0.05; β = 0.143, t (126) = 1.075 p > 0.05 have no significant association with the male and female students’ entrepreneurial readiness, respectively. On the other hand, proactivity shows significant association with male and female students’ entrepreneurial readiness β = 0.221, t (154) = 2.365 p < 0.05; β = 0.356, t (126) = 2.776 p < 0.05, respectively. This indicates that there is no significant gender difference between the students’ entrepreneurial readiness as influenced by IEO towards business creation. This further suggests that H4 (IEO propensities have significant gender difference in entrepreneurial readiness for business creation) should be rejected. It should be noted that, on aggregate, IEO shows significant association with both male and female students’ entrepreneurial readiness F (3;154) = p < 0.05; F (3;126) = p < 0.05, respectively.

Discussion of findings

The aim of this study is to comprehend students’ entrepreneurial readiness patterns as influenced by IEO positions on business creation. In this study, three constructs of IEO − risk-taking, innovation, proactivity, and a control variable (gender) − were evaluated for observed significance.

Research findings from the regression model indicate that IEO risk-taking ability has no significant impact on students’ entrepreneurial readiness β = 0.109, t (287) = 1.769, p > 0.05. Therefore, the first hypothesis was rejected. This is in line with the position of Olajide (2015) that risk-taking deficiency is one of the challenges facing students in Nigeria on venturing into business. The assertion was further buttressed by Ibrahim and Lucky (2014) that the IEO component of risk-taking is lacking among students in Nigeria. Despite the teaching on risk management as shown in the TVET entrepreneurship curriculum, findings from the study revealed that the students from these colleges show low risk-taking ability towards starting a business. The challenge may be attributed to a lack of practical training programmes on risk management in the entrepreneurship curriculum of the selected TVET colleges (see Table 1). Wennberg et al. (2013) had earlier stated that aversion to risk hinders entrepreneurship endeavours.

Several empirical investigations have shown that risk-taking ability is associated with successful entrepreneurs (Ebrahim and Schøtt 2011; Kumar et al. 2021). We argue that the low level of risk-taking ability, as demonstrated in this study, is not unconnected to the poor level of business creation among the youth. The ability to gather economic resources such as capital, investors, assets, employees, and suppliers for business implementation are a function of risk endeavour. Moreover, strong ability to take business risk is required to survive the current Nigeria’s entrepreneurial ecosystem.

Results from the regression analysis also reveal that IEO innovation and IEO proactivity show significant association with the students’ entrepreneurial readiness β = 0.153, t (287) = 2.200, p < 0.05; β = 0.286, t (287) = 3.745, p < 0.05, respectively. Therefore Hypotheses 2 and 3 were accepted. This result is consistent with the assertion of Wiklund and Shepherd (2005) that proactivity and innovation have a significant effect on the performance of an entrepreneur’s business. Bolton and Lane (2012) added that innovation and proactivity are essential to the business-decision process. Innovation and proactivity have also been found to influence entrepreneurship training for start-ups among students from Norway and the United States (Robinson and Stubberud 2014). This implies that innovative skills and proactive steps are critical for business start-ups. However, graduates of TVET colleges in Nigeria are yet to transform these skills into business enterprises. This is because of the low business spin-offs and increasing youth unemployment rate in the country.

Using gender as a control variable, the outcome of the regression analysis reveals that risk-taking β = 0.135, t (154) = 1.660, p > 0.05; β = 0.084, t (126) = 0.860, p > 0.05, and innovation β = 0.183, t (154) = 1.916, p > 0.05; β = 0.143, t (126) = 1.075, p > 0.05 have no significant association with male and female students’ entrepreneurial readiness, respectively. However, proactivity shows significant association with male and female students’ entrepreneurial readiness β = 0.221, t (154) = 2.365, p < 0.05; β = 0.356, t (126) = 2.776, p < 0.05, respectively. This suggests that there is no significant difference in both male and female students’ entrepreneurial readiness as determined by IEO. This result affirms the empirical findings of Suartha and Suprapti (2016). The authors reported that there is no significant difference between male and female students’ entrepreneurial intention as influenced by IEO. This study also demonstrated that the female students show higher proactive ability (B = 0.339) than their male (B = 0.246) counterparts. This finding aligns with the study conducted by Jelenc et al. (2016), in which female entrepreneurs were more proactive than male entrepreneurs; while there is no gender difference in risk-taking ability (Jelenc et al. 2016). This finding is in contrast to the report of Suartha and Suprapti (2016), in which male students have a higher score of IEO than their female counterparts. Additionally, Goktan and Gupta’s (2015) study on IEO of men and women from the United States, Turkey, Hong Kong, and India revealed that men are more strongly related to IEO than women. The gender indifference of IEO in male and female entrepreneurial readiness suggests the achievement of gender parity in entrepreneurship as a result of equal access to education (Adeniyi and Ganiyu 2021). In recent times, the Nigerian informal sector has witnessed an increase in female-owned businesses (Ogundana et al. 2021), which is driven by necessity entrepreneurship.

The insignificant association between risk-taking and innovation, and male and female entrepreneurial readiness may be attributed to poor infrastructural facilities and the continuous unavailability of foreign exchange for businesses in the country. For instance, the unpredictable power supply in many parts of the country discourages innovations and ideas for starting a business. Foreign exchange unavailability for business is the most recent cause of the exit of many multinational companies from Nigeria. Companies such as Michelin Tyres, Deli Foods, Procter & Gamble, the Mr Price Group, ExxonMobil, and GlaxoSmithKline, to name a few, have all shut down operations due to the cost of doing business in the country. The Nigerian naira has continued to fall against the dollar in recent times. The rate of the dollar jumped from 742.268 in August 2023 to 832.578 in October 2023 (Central Bank of Nigeria 2023) making it the worst fall in the history of foreign exchange. This hostile entrepreneurial ecosystem prevents young people from taking business risks (Adeniyi 2023).

Theoretical contributions

A major contribution to scholarship in entrepreneurship is the identification of the insignificant impact of risk-taking ability on entrepreneurial readiness of young people in Nigeria. The low level of risk-taking ability better underscores the low level of business start-up and the increase of youth unemployment in the country. Besides, previous studies have revealed that individuals who are more risk-tolerant benefit more from entrepreneurship than individuals who are less risk-tolerant (Fairlie and Holleran 2012). Accordingly, risk aversion has been found to create a negative effect on wealth creation (Kan and Tsai 2006). Results from 53 countries further indicate that risk aversion reduces individuals’ entrepreneurial intention (Costa and Mainardes 2016). Another contribution to this theory suggests that risk attitude is a determinant of entrepreneurial intention. This research thus provides support for the theory of planned behaviour as attitude toward risk, perceived behavioural control, and subjective norm show significant support for entrepreneurial intention (Kautonen et al. 2013; Wach and Wojciechowski 2016).

Contrary to many studies (Yordanova and Tarrazon 2010; Do Paço et al. 2015; Ward et al. 2019; Adeniyi et al. 2023), IEO shows no gender difference between male and female entrepreneurial readiness. This result contributes to the assumption that there are many similarities between male and female personality traits but genders may differ in terms of motivation (DeMartino and Barbato 2003). Motivational factors towards entrepreneurship may be either opportunity-driven or necessity-driven. However, women are more socially and economically disadvantaged at different levels of entrepreneurship than men (Zhang et al. 2009); which suggests the level of gender disparity in creating a business start-up (Díaz-García and Jiménez-Moreno 2010: Sánchez 2013). Nevertheless, successful entrepreneurs are perceived to have feminine characteristics (Díaz-García and Jiménez-Moreno 2010). This debate is inconclusive since similarities and differences have been found between male and female entrepreneurs (Lim and Envick 2013).

This is one of the first studies to measure students’ entrepreneurial orientation for entrepreneurial readiness within the context of TVET colleges in Nigeria.

Practical contributions

Despite the great support for socio-cultural and economic effects on an individual’s decision and intention to become an entrepreneur, this study aligns with certain studies that find that psychological attributes are related to entrepreneurship and can be acquired (Ajzen 2001) through entrepreneurship education. The study of the entrepreneurial mindset is critical to improving the psychological traits of an individual. An entrepreneurial mindset refers to the way in which entrepreneurs think and act, which is a combination of both personality traits and entrepreneurial skills. The current entrepreneurship education curriculum at the selected TVET college requires a reform in the development of individual students’ entrepreneurial mindsets towards business creation.

This study findings underscore the need for Lagos State Vocational Education Board (LASTVEB), and other stakeholders in curriculum reform for TVET colleges and general education to gain insight into reforming the entrepreneurship curriculum content to suit students’ needs. The inadequacy of practical entrepreneurship trainings is also evident in this study. Because entrepreneurship education is practice-oriented, there is a crucial need to incorporate extensive hands-on-learning entrepreneurship programmes via workshops, seminars, computer-based simulations, and field activities with TVET skills. There is urgent need for the government to improve infrastructural facilities and the economic situation to encourage foreign investors and young minds to take advantage of entrepreneurship opportunities.

Conclusion

Entrepreneurship education is globally recognised for its role in human capital development. However, the entrepreneurial ecosystem in Nigeria does not encourage young individuals to harness the opportunities in entrepreneurship. It was observed that the lack of business risk-taking ability may be traceable to the faulty entrepreneurship curriculum, in which risk-taking management is taught as a classroom subject only, while neglecting the importance of entrepreneurship training programmes or workshops on how to take business risks. Furthermore, the hostile entrepreneurial environment in the country could prevent potential entrepreneurs from taking business risks. The cost of doing business has led to the exit of many multinational organizations in recent times (Adeniyi 2023). There is evidence to suggest that there is a high level of risk aversion among young minds towards starting a business. This challenge influences the low business creation among the youth in Nigeria. There is a need to promote and develop the entrepreneurial mindset of young people to foster business start-ups for self-employment and creation of business opportunities.

Limitations and future study

Four hypotheses were formulated in this study. Risk-taking, proactivity, and innovation are the most adopted components of EO; and gender construct was introduced as a control variable. Some other fundamental constructs of EO such as autonomy and competitive aggressiveness were not considered in this study. We suggest that future research may consider the assessment of self-efficacy, subjective norm, and perceived behavioural control towards engaging in entrepreneurial activities among nascent entrepreneurs. A mixed-methods approach with nascent entrepreneurs may provide deeper insights into the interlink between components of entrepreneurial orientation and business intention. The inclusion of the ecosystem components (private sector, financial institutions, start-up incubators) may further provide insights into the cause and effects of low business start-ups among young individuals in other developing countries.

Data availability

The primary data of this survey research is available on Humanities & Social Sciences Communications Dataverse repository online: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/2YZXLR.

References

Abubakar SA, Yakubu MS (2019) Moderating effect of individual entrepreneurial orientation on the relationship between entrepreneurship education and student entrepreneurial intention. Islamic Univ Multidiscip J 5(6):69–79. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/335820643_Effect_of_individual_entrepreneurial_orientation_between_education_and_student_intention#fullTextFileContent

Adebayo PO (2015) Impact of social media on students’ entrepreneurial orientation: a study of selected institutions in Nigeria. Journal of Advance Research in Business Management and Accounting 1(10):08–16. https://doi.org/10.53555/nnbma.v1i10.117

Adeniyi AO (2023) The mediating effects of entrepreneurial self-efficacy in the relationship between entrepreneurship education and start-up readiness. Hum Soc Sci Commun 10(1):1–14. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-02296-4

Adeniyi AO (2021) Psychosocial determinants of entrepreneurial readiness: the role of TVET institutions in Nigeria. (Doctoral thesis, University of KwaZulu-Natal) South Africa. https://ukzn-dspace.ukzn.ac.za/handle/10413/20102

Adeniyi AO, Gamede VW, Derera E (2023) Exploring dimensions of entrepreneurship education as determinants of entrepreneurial readiness among exit-level students at selected TVET colleges in a developing context. J Contemp Manag 20(2):236–259. https://doi.org/10.35683/jcman1010.221

Adeniyi AO, Derera E, Gamede V (2022) Entrepreneurial self-efficacy for entrepreneurial readiness in a developing context: a survey of exit level students at TVET institutions in Nigeria. SAGE Open 12(2):1–15. https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440221095059

Adeniyi AO, Ganiyu IO (2021) Reshaping education and entrepreneurial skills for Industry 4.0. In AO Ayansola (ed.) Reshaping entrepreneurship education with strategy and innovation (pp. 64–77). IGI Global. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-7998-3171-6.ch004

Ajzen I (2001) Nature and operation of attitudes. Annu Rev Psychol 52(1):27–58. https://www.annualreviews.org/doi/abs/10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.27

Alarape AA (2013) Entrepreneurial orientation and the growth performance of Small and Medium Enterprises in Southwestern Nigeria. J Small Bus Entrepreneurship, 26(6):553–577. https://doi.org/10.1080/08276331.2014.892308

Aminu MI (2016) Proposing individual entrepreneurial orientation as a moderator on the relationship between entrepreneurship education and students’ intention to venture creation in Nigeria. Niger J Manag Technol Dev 7:174–178

Bandera C, Collins R, Passerini K (2018) Risky business: experiential learning, information and communications technology, and risk-taking attitudes in entrepreneurship education. Int J Manag Educ 16(2):224–238. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijme.2018.02.006

Bolton DL, Lane MD, (2012) Individual entrepreneurial orientation: development of a measurement instrument. Emerald Publishing 54(2/3): 219–233. https://doi.org/10.1108/00400911211210314

Braum L et al. (2023) Propensity to entrepreneurship and its antecedents: development and validation of a measurement scale. Cadernos EBAPE. BR 21:e2022-0254. https://doi.org/10.1590/1679-395120220254x

Central Bank of Nigeria (2023) Exchange rate. Available at: https://www.cbn.gov.ng/rates/ExchRateByCurrency.asp

Chow MM, Hock OY (2021) Developing pre-retiree intent-entrepreneurship learning to new normal entrepreneurial initiatives. Solid State Technol 64(2):318–333. http://ur.aeu.edu.my/id/eprint/873

Coduras A, Saiz-Alvarez JM, Ruiz J (2016) Measuring readiness for entrepreneurship: an information tool proposal. J Innov Knowl 1(2):99–108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jik.2016.02.003

Costa LDA, Mainardes EW (2016) The role of corruption and risk aversion in entrepreneurial intentions. Appl Econ Lett 23(4):290–293. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504851.2015.1071462

Covin JG, Rigtering JC, Hughes M et al. (2020) Individual and team entrepreneurial orientation: scale development and configurations for success. J Bus Res 112:1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.02.023

Craig JB, Pohjola M, Kraus S et al. (2014) Exploring relationships among proactiveness, risk‐taking and innovation output in family and non‐family firms. Creativity Innov Manag 23(2):199–210. https://doi.org/10.1111/caim.12052

Dakhan SA, Khan A, Akhtar S et al. (2021) Role of university support and instrumental readiness on student’s entrepreneurial orientation and intention. Int J Manag 12(2):195–204. https://doi.org/10.34218/IJM.12.2.2021.020

Darmasetiawan NK (2019) Readiness and entrepreneurial self-efficacy actors of SMEs snake-fruit processed products in the conduct of e-business. Atlantis Press 74: 1–5

DeMartino R, Barbato R (2003) Differences between women and men MBA entrepreneurs: exploring family flexibility and wealth creation as career motivators. J Bus Venturing 18(6):815–832. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-9026(03)00003-X

Derera E, et al (2020) Entrepreneurship and women’s economic empowerment in Zimbabwe: research themes and future research perspectives. https://doi.org/10.4102/td.v16i1.787

Díaz-García MC, Jiménez-Moreno J (2010) Entrepreneurial intention: the role of gender. Int Entrep Manag J 6:261–283. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-008-0103-2

Do Paço A, Ferreira JM, Raposo M et al. (2015) Entrepreneurial intentions: is education enough? Int Entrep Manag J 11:57–75. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-013-0280-5

Ebrahim M, Schøtt T (2011) Entrepreneurial intention promoted by perceived capabilities, risk propensity, and opportunity awareness a global study. Stockholm, Sweden

Eniola AA (2020) Entrepreneurial self-efficacy and orientation for SME development. Small Enterprise Research 1–21 https://doi.org/10.1080/13215906.2020.1752295

Fagge BG (2017) 21st century global changes in education: entrepreneurship education and TVET for sustainable development. J Hum Cap Dev 10(2):75–81. https://journal.utem.edu.my/index.php/jhcd/article/view/3205/2312

Fairlie RW, Holleran W (2012) Entrepreneurship training, risk aversion and other personality traits: Evidence from a random experiment. J Econ Psychol 33(2):366–378. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joep.2011.02.001

Ferreira J, Ratten V, Dana LP (2017a) Knowledge spillover-based strategic entrepreneurship. INT ENTREP MANAG J 13:161–167. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-016-0415-6

Ferreira JJ, Fayolle A, Fernandes C et al. (2017b) Effects of Schumpeterian and Kirznerian entrepreneurship on economic growth: panel data evidence. Entrep Regional Dev 29(1–2):27–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/08985626.2016.1255431

Ferreira J J et al. (2012) A model of entrepreneurial intention: an application of the psychological and behavioral approaches. J Small Bus Enterp Dev 19(3):424–440. https://doi.org/10.1108/14626001211250144

Gabriel JMO, Kobani D(2022) An evaluation of individual entrepreneurial orientation and community development in Nigeria. World J Adv Res Rev 15(01):246–256. https://doi.org/10.30574/wjarr.2022.15.1.0692

Goktan AB, Gupta VK (2015) Sex, gender, and individual entrepreneurial orientation: evidence from four countries. Int Entrep Manag J 11(1):95–112. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-013-0278-z

Hashimu SN (2018) Moderating effect of culture on the relationship between entrepreneurial competencies, entrepreneurial orientation, and women entrepreneurs’ business success in north-western Nigeria (Doctoral dissertation, Universiti Utara Malaysia)

Ibrahim NA, Lucky EOI (2014) Relationship between entrepreneurial orientation, entrepreneurial skills, environmental factor and entrepreneurial intention among Nigerian students in UUM. Entrep Innov Manag J 2(4):203–213

Ilevbare FM, Ilevbare OE, Adelowo CM, Oshorenua FP (2022) Social support and risk- taking propensity as predictors of entrepreneurial intention among undergraduates in Nigeria. Asia Pac J Innov Entrep 16(2):90–107. https://doi.org/10.1108/APJIE-02-2022-0010

Ita VE, Bassey JE (2022) Rising youth unemployment and the socio-economic realities in Nigeria: the Akwa Ibom State Experience. International Journal of Development and Economic Sustainability 10(10):1–14. https://eajournals.org/ijdes/vol10-issue-4-2022-2/rising-youth-unemployment-and-the-socio-economic-realities-in-nigeria-the-akwa-ibom-state-experience/

Iqbal A, Melhem Y, Kokash H (2012) Readiness of the university students towards entrepreneurship in Saudi Private University: an exploratory study. Eur Sci J 8(15): 109–131. https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/328023421.pdf

Jelenc L, Pisapia J, Ivanušić N (2016) Demographic variables influencing individual entrepreneurial orientation and strategic thinking capability. J Econ Soc Dev 3(1):3–16. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2715121

Jerven M (2010) The relativity of poverty and income: how reliable are African economic statistics? Afr Aff 109(434):77–96. https://doi.org/10.1093/afraf/adp064

Jerven M (2013) For richer, for poorer: GDP revisions and Africa’s statistical tragedy. Afr Aff 112(446):138–147. https://doi.org/10.1093/afraf/ads063

Jerven M, Johnston D (2015) Statistical tragedy in Africa? Evaluating the database for African economic development. J Dev Stud 51(2):111–115. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2014.968141

Kan K, Tsai WD (2006) Entrepreneurship and risk aversion. Small Bus Econ 26:465–474. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-005-5603-7

Kautonen T, Van Gelderen M, Tornikoski ET (2013) Predicting entrepreneurial behaviour: a test of the theory of planned behaviour. Appl Econ 45(6):697–707. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036846.2011.610750

Koe WL (2016) The relationship between individual entrepreneurial orientation and entrepreneurial intention. J Glob Entrep Res 6(1):1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40497-016-0057-8

Koen V, Asada H, Rahuman MRH (2018) Boosting productivity and living standards in Thailand. OECD Working Paper. Retrieved from: https://doi.org/10.1787/e525c875-

Kumar S, Paray ZA, Dwivedi AK (2021) Student’s entrepreneurial orientation and intentions: a study across gender, academic background, and regions. High Educ, Skills Work-Based Learn 11(1):78–91. https://doi.org/10.1108/HESWBL-01-2019-0009

Kuratko DF, Morris MH, Schindehutte M (2015) Understanding the dynamics of entrepreneurship through framework approaches. Small Bus Econ 45(1):1–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-015-9627-3

Kurniawan JE, Suhariadi F, Hadi C (2017) The impact of school’s corporate cultures on teacher’s entrepreneurial orientation: the mediating role of readiness for change. University of Ciputra, Indonesia http://dspace.uc.ac.id/handle/123456789/5280

Ladipo MK, Akhuemonkhan IA, Raimi L (2013) Technical Vocational Education and Training (TVET) as a mechanism for sustainable development in Nigeria (SD): potentials, challenges, and policy prescriptions. TVET for Sustainable Development in Africa. Held in Banjul, the Gambia from 2nd to 8th June 2013 at The Paradise Suits Hotel, p.12

Lagos State Vocational Education Board (2017) Directorate of Curriculum and Examinations. Retrieved from: https://lastveb.com.ng/directorates-and-staff/directorate-of-curriculum-and-

Lawan SA, Fakhrul AZ (2015) Vision, innovation, pro-activeness, risk-taking and SMEs performance: a proposed hypothetical relationship in Nigeria. Int J Acad Res Econ Manag Sci 4(2):2226–3624. http://eprints.unisza.edu.my/id/eprint/5064

Lim S, Envick BR (2013) Gender and entrepreneurial orientation: a multi-country study. Int Entrep Manag J 9:465–482. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-011-0183-2

Lumpkin GT, Dess GG (2001) Linking two dimensions of entrepreneurial orientation to firm performance: the moderating role of environment and industry life cycle. J Bus Venturing 16(5):429–451. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-9026(00)00048-3

Luu N, Ngo LV (2019) Entrepreneurial orientation and social ties in transitional economies. Long Range Plan 52(1):103–116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2018.04.001

Lyon DW, Lumpkin GT, Dess GG (2000) Enhancing entrepreneurial orientation research: operationalizing and measuring a key strategic decision-making process. J Manag 26(5):1055–1085. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/014920630002600503

Maigida JF, Saba TM, Namkere JU (2013) Entrepreneurial skills in technical vocational education and training as a strategic approach for achieving youth empowerment in Nigeria. Int J Hum Soc Sci 3(5):303–310. http://repository.futminna.edu.ng:8080/jspui/handle/123456789/3029

Miller D (1983) The correlates of entrepreneurship in three types of firms. Manag Sci 29(7):770–791. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.29.7.770

National Bureau of Statistics (2020). Population of youth in Nigeria. Abuja: NBS. Retrieved from: National Bureau of Statistics https://nigerianstat.gov.ng

Ndoro T, van Niekerk R (2019) A psycho-biographical analysis of the personality traits of Steve jobs’ entrepreneurial life. Indo-Pac J Phenomenol 19(1):31–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/20797222.2019.1620421

Nikitina T et al. (2023) Individual entrepreneurial orientation: comparison of business and STEM students. Emerald Publ Group 65(4):565–586. https://doi.org/10.1108/ET-07-2021-0256

Ogundana OM et al. (2021) Women entrepreneurship in developing economies: a gender-based growth model. J Small Bus Manag 59(1):42–72. https://doi.org/10.1080/00472778.2021.1938098

Okolie UC, Elom EN, Osuji CU et al. (2019) Improvement needs of Nigerian technical college teachers in teaching vocational and technical subjects. Int J Train Res 17(1):21–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/14480220.2019.1602207

Olajide SE (2015) Repositioning technical and vocational education toward eradicating unemployment in Nigeria. Int J Vocat Tech Educ 7(6):54–63

Otache I, Edopkolor JE, Kadiri U (2022) A serial mediation model of the relationship between entrepreneurial education, orientation, motivation, and intentions. Int J Manag Educ 20(2):100645. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijme.2022.100645

Oviawe JI (2010) Repositioning Nigerian youths for economic empowerment through entrepreneurship education. Euro J Educ Stud 2(2):113–118

Penz D, Amorim BC, do Nascimento S et al. (2017) The influence of technology readiness index in entrepreneurial orientation: a study with Brazilian entrepreneurs in the United States of America. Int J Innov: IJI J 5(1):66–76. https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=5917127

Pratomo RPK, Mulyadi H, Utama DH (2018) Pengaruh pembelajaran kewirausahaan terhadap kesiapan berwirausaha siswa kelas Xii pastry sekolah menengah kejuruan negeri 9 bandung. J Bus Manag Educ 3(2):67–77. https://doi.org/10.17509/jbme.v3i2.14216

Rahaman MA et al. (2021) Do risk-taking, innovativeness, and proactivity affect business performance of SMEs? A case study in Bangladesh. J Asian Financ, Econ Bus 8(5):689–695. https://doi.org/10.13106/jafeb.2021.vol8.no5.0689

Robinson S, Stubberud HA (2014) Elements of entrepreneurial orientation and their relationship to entrepreneurial intent. J Entrep Educ 17(2):1–11

Sánchez JC (2013) The impact of an entrepreneurship education program on entrepreneurial competencies and intention. J Small Bus Manag 51(3):447–465. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsbm.12025

Saputri INA, Wardana L, Kusdiyanti H (2019) The effect of entrepreneurship knowledge And personality personnel against business readiness through an entrepreneurial interest in the prospective Purnawirawan East Java Police Unit. Int Jf Bus Econ Law 20(5):120-126. https://ijbel.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/IJBEL20_226.pdf

Sasu DK (2022) Forecast Unemployment Rate in Nigeria 2021–2022. Trading Economics. Retrieved from: https://tradingeconomics.com/nigeria/unemployment-rat

Shamsudin SFFB, (2017) Factors influencing entrepreneurial intention and the moderating role of entrepreneurship education: a conceptual model. Adv Sci Lett 23(4): 3006–3008. https://doi.org/10.1166/asl.2017.7635

Soetjipto BW, Alanudin D, Sidik HM et al. (2022) Understanding the effects of digital transformation, entrepreneurial orientation, readiness for change, and innovative behaviour on performance. Int J Bus Syst Res 16(5-6):709–731. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJBSR.2022.125496

Storey DJ, Greene FJ (2010) Small business and entrepreneurship. Pearson Education Ltd, Essex

Suartha N, Suprapti NWS (2016) Entrepreneurship for students: the relationship between individual entrepreneurial orientation and entrepreneurial intention. Eur J Bus Manag 8(11):45–52. https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/234627209.pdf

Vincent C, John WS, Asukwo AE (2021) Improving curriculum content of electrical/electronics engineering of Polytechnics in North-East Nigeria for technology-driven curriculum. Online Journal for TVET Practitioners 6(2):41–49. https://publisher.uthm.edu.my/ojs/index.php/ojtp/article/view/9262

Vogelsang L (2015) Individual entrepreneurial orientation: an assessment of students (Doctoral dissertation) Humboldt State University https://scholarworks.calstate.edu/downloads/1c18dj33x

Voss Z, Voss GB, Moorman C (2005) An empirical examination of the complex relationships between entrepreneurial orientation and stakeholder support. Eur J Mark 39(9/10):1132–1150. https://doi.org/10.1108/03090560510610761

Wach K, Wojciechowski L (2016) Entrepreneurial intentions of students in Poland in the view of Ajzen’s theory of planned behaviour. Entrep Bus Econ Rev 4(1):83–94

Ward A, Hernández-Sánchez BR, Sánchez-García JC (2019) Entrepreneurial potential and gender effects: the role of personality traits in university students’ entrepreneurial intentions. Front Psychol 10:2700. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02700

Wennberg K, Pathak S, Autio E (2013) How culture moulds the effects of self-efficacy and fear of failure on entrepreneurship. Entrep Reg Dev 25(9-10):756–780. https://doi.org/10.1080/08985626.2013.862975

Westhead P, Wright M, McElwee G (2011) Entrepreneurship: perspectives and cases. Pearson Education Limited, Essex

Wiklund J, Shepherd D (2005) Entrepreneurial orientation and small business performance: a configurational approach. J Bus Venturing 20(1):71–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2004.01.001

Wilson V (2014) Research methods: triangulation. Evid based Libr Inf Pract 9(1):74–75. https://doi.org/10.18438/B8WW3X

Wulandari A, Hermawan A, Mukhlis I (2021) Exploring determinants of entrepreneurial readiness on Sukses Berkah community’s member. J Bus Manag Rev 2(4):303–317. https://doi.org/10.47153/jbmr24.1332021

Yordanova DI, Tarrazon MA (2010) Gender differences in entrepreneurial intentions: evidence from Bulgaria. J Dev Entrep 15(03):245–261. https://doi.org/10.1142/S1084946710001543

Yunusa ZF, Aminu M, Badara MS et al. (2022) Moderating effect of need for achievement on the relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and performance of small and medium enterprises in Gombe state. J Entrep Innov Res 1(1):1–16

Zaleskiewicz T, Bernady A, Traczyk J (2020) Entrepreneurial risk taking is related to mental imagery: a fresh look at the old issue of entrepreneurship and risk. Appl Psychol 69(4):1438–1469. https://doi.org/10.1111/apps.12226

Zhang Z, Zyphur MJ, Narayanan J et al. (2009) The genetic basis of entrepreneurship: effects of gender and personality. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process 110(2):93–107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2009.07.002

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AO developed the concepts, literature review, methodology and composed the discussion of the study. VW contributed to the literature review, and discussion of the study. DE contributed to the literature review, analysis, and discussion of the study.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This research has been ethically reviewed and approved by the University of KwaZulu-Natal Humanities and Social Sciences Research Ethics Committee (approval number HSSREC/00000289/2019). All procedures in this study were in accordance with the institutional research and the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all the participants in this study, and confidentiality of the participants were treated according to POPIA guidelines.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Adeniyi, A.O., Gamede, V. & Derera, E. Individual entrepreneurial orientation for entrepreneurial readiness. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11, 264 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-02728-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-02728-9

- Springer Nature Limited