Abstract

In the exploration of factors influencing women’s empowerment, prior research has offered limited insights into the impact of technology, specifically the Internet. This study pioneers the incorporation of the Internet into the framework of women’s empowerment, investigating its causal effect on women’s bargaining power within households. Bargaining power is defined here as women’s capacity to shape crucial decisions pertaining to significant family matters such as investments and property acquisitions. Utilizing data from the Third National Survey on Chinese Women’s Social Status and the 2014 China Family Panel Studies, this paper reveals that Internet usage significantly enhances women’s bargaining power. Notably, this positive effect persists even after addressing endogeneity concerns through instrumental variable methodology. The study further uncovers that the empowering influence of Internet use is particularly pronounced in rural areas. Gender beliefs, employment status, and income level emerge as pivotal mediating factors through which Internet usage influences women’s bargaining power. The findings highlight the crucial role of digital technology in women’s empowerment, underscoring the importance of policies aimed at expanding women’s Internet access to enhance their bargaining power within households.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Amidst China’s rapid socio-economic advancement, women have gained substantial sway in household bargaining process. This surge is evident in their proactive involvement in various household choices, a trend substantiated by the 2010 Third National Survey on Chinese Women’s Social Status (NSWSS). Impressively, a significant percentage of women, at 74.7%, 72.5%, and 74.4%, actively participated in decisions concerning household loans, business matters, and house purchases, respectively. Furthermore, there has been a notable rise in women’s influence over household finances. As per the 2018 Chinese Household Financial Market Analysis Report, in 62% of Chinese households, a female member holds ultimate decision-making authority regarding financial mattersFootnote 1. This coincides with the rapid socioeconomic transformation in China, which has facilitated widespread access to technology and media, particularly exemplified by the sharp increase in Internet users. The 2023 China Internet Development Report disclosed an impressive 1.079 billion Internet users, boasting a penetration rate of 76.4%Footnote 2. The Internet, emerging as a powerful tool for communication and information dissemination, has left an indelible mark on daily life and production. Its impact, especially in relation to residents’ well-being, including that of women, has garnered considerable attention from scholars.

Previous research underscores that the bolstering of women’s bargaining power predominantly arises from increased self-esteem, education, property rights, and income levels, as these directly fortify women’s threat point within the household (Li, 2023a; Moeeni, 2021; Wang, 2014). However, unlike traditional elements such as income, education, and property rights that impact women’s well-being, technological elements, specifically the Internet, have introduced a new dimension in influencing women’s welfare. For example, the Internet has been associated with women’s labor market outcomes, fertility, gender beliefs, and mental health in the burgeoning digital age (Billari et al., 2019; Golin, 2022; Shuangshuang et al., 2023). The comprehensive influence of the Internet on women’s overall well-being remains an area for future exploration. Concerning our topic, a pertinent question emerges: regarding women’s welfare in the household, does the Internet significantly catalyze the improvement of women’s bargaining power in this process, and if so, through what means? Thus far, we have lacked understanding regarding whether the Internet causally affects women’s bargaining power and the underlying mechanisms involved.

Considering this, this paper endeavors to utilize two major databases, the Third National Survey on Chinese Women’s Social Status (NWSSS), along with China Family Panel Studies (CFPS) to investigate the relationship between the Internet and women’s bargaining power and its transmission paths under the framework of resource-agency-achievement (Kabeer, 1999). The use of the Internet is seen as a valuable resource, while shifts in women’s intra-household bargaining power are manifested through agency. This paper employs an instrument variable approach to study a causal relationship between them and the counterfactual framework of causal mediation analysis to dissect direct and indirect effects, calculating the proportion of the mediating effect in the total effect. The paper concludes that Internet use significantly enhances women’s bargaining power. In terms of transmission pathways, gender beliefs play a substantial role at ~11.435%, while income accounts for 9.88% and employment status contributes 3.085%.

The contribution of this paper lies in three aspects. Firstly, for the first time, we incorporate the Internet as a technological factor within the framework of women’s empowerment, exploring the role of new media, represented by the Internet, in enhancing women’s intra-household bargaining power. Meanwhile, it uncovers the potential transmission channels of Internet use in enhancing women’s bargaining power, offering fresh avenues for analyzing the Internet’s impact on internal family dynamics and welfare. Secondly, we test the causal relationship between Internet use and women’s bargaining power by utilizing an instrument variable approach and employing the counterfactual framework of causal mediation analysis to separate direct and indirect effects, effectively quantifying the significance of each mediating variable. So, we can provide more precise policy recommendations in further improving women’s bargaining position in the household. Thirdly, this study holds significant relevance for other developing countries in front of the digital revolution. The research findings highlight that Internet use plays a significant role in increasing women’s agency in family negotiations, so, to improve the socioeconomic well-being of women, we can shift some traditional approaches to an Internet-based approach.

The subsequent sections are structured as follows: section “Literature review and research hypotheses” encompasses a review of literature and research hypotheses, section “Data, model, variables and descriptive statistics” introduces data, model, variables, and descriptive statistics, section “Empirical analysis and its interpretation” presents econometric analysis and its interpretation, and the final sections concludes with the findings and policy implications of this study.

Literature review and research hypotheses

The determinants of intrahousehold bargaining power

Historically, initial research, notably led by Nobel laureate Becker (1981), introduced the unitary model, assuming a unified set of preferences governing resource allocation within families. This theoretical framework suggests that families aim to maximize a singular representative utility function, disregarding recipient identities due to resource pooling. However, recent empirical evidence, as highlighted by Molina et al. (2023) and Saelens (2022), has raised significant challenges to its validity. As a result, there has been a notable shift towards the collective model, championed by scholars such as Apps and Rees (1988) and Chiappori (1988, 1992). This alternative framework perceives families as negotiators with varied preferences and resource endowments, acknowledging the diversity among household members. Increasing empirical studies have lent support to the collective model in understanding family dynamics (Bargain et al., 2022; Molina et al., 2023). Consequently, the dominant paradigm for analyzing household behavior has transitioned from the unitary model to the more robust collective model (Donni and Molina, 2018).

Within the framework of the collective model, scholars frequently employ the resource endowments theory to shed light on the allocation of household resources. This theory emphasizes that elements like income, employment, and occupation significantly shape the bargaining power of individuals within households (Chen and Park, 2023; Dong, 2022). Until now, it has accumulated substantial empirical support across diverse countries (Nguyen and Le, 2023; Parada, 2023), establishing itself as the primary framework for understanding power dynamics within couples on a micro level. Nonetheless, empirical findings may occasionally diverge, resulting in conflicting conclusions, such as the suggestion that women’s ownership of resources does not necessarily improve their bargaining outcomes, potentially due to resistance from men (Benstead et al., 2023; Dhanaraj and Mahambare, 2022).

In this context, the cultural norm theory presents an alternative viewpoint, highlighting the influence of external factors such as gender norms, religious beliefs, and social norms on the negotiation dynamics within households (Li, 2023b; Mabsout and van Staveren, 2010). Especially in numerous developing nations, these biased gender norms function as institutional barriers that often disadvantage women within household settings. For instance, Staveren and Ode Bode (2007) discovered that despite improved fallback positions, women’s well-being might not necessarily improve due to the impact of restrictive patriarchal norms on relative power dynamics in Nigeria. Similar studies highlight the potential risk of a temporary backlash in domestic violence during periods of female economic and educational empowerment, as men may attempt to reassert control over their wives through physical and sexual violence (Erten and Keskin, 2018; Matjasko et al., 2020). These instances underscore the significance of considering both resource endowments and cultural norms when exploring power dynamics within families.

A conceptual framework between Internet use and women’s bargaining power

The Internet, as a transformative technological catalyst, profoundly influences multiple facets of human life and productivity, notably in politics, economics, education, law, and culture. It serves as an effective tool for disseminating policy information, bridging digital gaps, and fostering comprehension of modern-day concerns, thereby reinforcing individual rights (Nisbet et al., 2012). In our study, we anticipate that the Internet plays a pivotal role in enhancing women’s bargaining power through several significant mechanisms.

First, Internet use significantly enhances women’s employment prospects by providing them access to a wide range of opportunities, resources, and networks that were previously limited or unavailable. The Internet enables remote work, allowing women to engage in employment even if commuting to a physical office is impractical (Bailur and Masiero, 2017). This flexibility is particularly beneficial for women who bear caregiving responsibilities or face mobility constraints. Additionally, social media platforms and professional networking sites offer avenues for women to connect with peers in their respective fields, participate in webinars and workshops, and stay updated on industry trends. This networking can lead to job referrals, collaborative ventures, and valuable mentorship opportunities (Robertson and Kee, 2017). Moreover, the Internet provides a platform for women to market and sell products and services through e-commerce platforms or online marketplaces, opening up entrepreneurial opportunities and creating employment for women who may not have access to traditional brick-and-mortar markets (Melissa et al., 2015).

Secondly, Internet usage has the potential to substantially augment women’s income in several ways. The Internet expands job opportunities through online portals, freelancing platforms, remote work options, and e-commerce ventures, overcoming geographical limitations that might otherwise restrict income avenues (Atasoy, 2013; Denzer et al., 2021). Additionally, Internet usage facilitates the establishment and management of online businesses, utilizing e-commerce platforms and social media to showcase products or services, reach broader audiences, and boost earnings (Galloway et al., 2011). It also acts as an educational resource hub, providing diverse courses and skill development programs. This enables women to upgrade their skills, improving employability for higher-paying roles or entrepreneurial success (Palvia et al., 2018). Furthermore, the flexibility of online work enables women to better balance personal and professional commitments, potentially boosting both productivity and income levels (Carlson et al., 2010; Coenen and Kok, 2014). So, the Internet serves as a conduit to diverse income streams, facilitates skill enhancement, fosters networking opportunities, and provides the flexibility necessary to elevate women’s income levels.

Thirdly, the use of the Internet significantly shapes women’s perceptions of gender roles, fostering a transition from traditional to egalitarian perspectives (Viollaz and Winkler, 2022). Internet users, through access to diverse global perspectives and experiences, are progressively challenging deeply rooted gender expectations (Zhou et al., 2020). Furthermore, online communities and forums advocating gender equality provide spaces for support and discussions, reshaping attitudes toward stereotypical roles (Liu et al., 2020). Educational materials and online campaigns emphasize gender equality, prompting a reassessment of established beliefs. Additionally, the presence of visible role models breaking traditional norms serves as inspiration for others to challenge these norms (Chhaochharia et al., 2022). Internet activism dedicated to gender equality sparks discussions and garners support, encouraging a rethinking of traditional roles (Gheytanchi and Moghadam, 2014). Collectively, the Internet’s diverse perspectives, educational resources, supportive communities, and influential role models all contribute to shifting attitudes toward more egalitarian gender roles.

Given its notable role in bolstering women’s employment status and income, and disseminating egalitarian gender role perspectives, the Internet has taken on an increasingly significant position in women’s empowerment research. The foregoing research on factors influencing women’s bargaining power indicates that all these three aforementioned aspects serve to strengthen women’s capacity to influence the household bargaining process. As illustrated in Fig. 1, there are three pathways through which Internet use impacts women’s bargaining power.

Building upon this, this study posits the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1: Internet use enhances women’s bargaining power.

Hypothesis 2: Women’s employment status, income level, and gender belief are pivotal conduits through which Internet use enhances women’s bargaining power.

Data, model, variables, and descriptive statistics

Data source

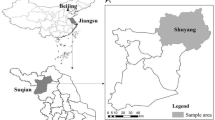

This study mainly relies on data from the National Survey on Chinese Women’s Social Status (NSWSS) for empirical analysis. The survey employs a random sampling method to select Chinese people aged 18 and above, excluding those from Hong Kong, Macau, and Taiwan. Ultimately, it gathers data from ~30,000 individuals, forming a nationally representative sample. To date, three waves of NSWSS surveys have been conducted and released, NSWSS 1990, 2000, and 2010, respectively. We utilize the most recent survey, i.e., NSWSS 2010 to capture the current state of social development and the status of women in China. The 2010 NSWSS survey covers nine key areas, including women’s health, education, economic status, social security, politics, marriage and family dynamics, lifestyle, legal rights and awareness, and gender attitudes and beliefs. Although the NSWSS is a cross-sectional survey, it brings two advantages to this study: firstly, it assesses women’s family dynamics from various angles, like power dynamics within the household and involvement in daily housework, enhancing the robustness of the study’s findings. Secondly, it offers a rich array of unique information, such as gender beliefs, and details about spouses. These aspects not only help mitigate issues related to omitted variable bias but also provide mediating variables for understanding how Internet usage impacts women’s family dynamics.

We limit our sample to married women, as the analysis focuses on women’s intrahousehold bargaining power. Additionally, we exclude retired women from the sample, as Internet use may impact women’s bargaining power by potentially augmenting their employment status. Following the treatment of missing observations in the main variables, we are left with 5408 observations for empirical analysis.

Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics comparing the main demographic variables between the initial and final samples in the NSWSS. The data demonstrates strikingly similar patterns in both mean values and standard deviations across these variables in both samples. This reaffirms the representativeness of our final sample within the NSWSS dataset. Consequently, we can confidently utilize the collected NSWSS dataset for empirical analysis, ensuring the retention of crucial information.

To fortify our study’s conclusions, we also utilize the China family panel studies (CFPS) for robustness checks. Conducted biennially, the national longitudinal CFPS survey comprehensively monitors shifts in China’s social, economic, demographic, educational, and health-related dimensions. Each wave of the CFPS comprises three types of datasets, adult, family relationship, and family economy, surveying diverse levels of information. Up to now, the most recent survey available is the CFPS 2020. However, among all the survey rounds, only the CFPS 2014 includes the essential variables, i.e., intra-household bargaining power and Internet usage, while none of the other survey rounds encompass both. Consequently, we rely on the 2014 CFPS adult, family relations, and family economic databases to probe the correlation between Internet usage and women’s family dynamics. To address critical information gaps, including years of marriage, emphasis on family harmony and happiness, and parents’ educational levels, we combine the 2010 CFPS adult database with the 2014 CFPS using respondents’ Personal IDs (PIDs). Upon handling missing observations within the utilized variables, a total of 5751 observations are available for empirical analysis.

Table 1A in the Appendix presents descriptive statistics that compare the key demographic variables between the initial and final samples in the CFPS. Similarly, it illustrates consistent patterns in mean values and standard deviations across these variables in both sample sets, further substantiating the representativeness of our final sample within the CFPS dataset.

Econometric model

To scrutinize the influence of Internet usage on women’s bargaining power, this study employs two metrics that reflect women’s bargaining power as dependent variables. Internet usage is considered the key explanatory variable, while various potential confounding factors are incorporated as control variables. The study establishes two econometric models as follows:

Here, Actual_power and Bargain_power represent the dependent variables, signifying women’s bargaining power. Internet_use serves as the primary explanatory variable, reflecting the frequency of Internet usage. The coefficients, denoted as β11 and β22, are the parameters that require estimation. They serve to assess the direction and magnitude of Internet usage’s influence on women’s bargaining power. Covariates refer to control variables at the individual, intra-family, and community levels. It is worth noting that both Actual_power and Bargain_power are treated as ordered discrete choice variables. To enhance the robustness of the study, following the approach of Ferrer-i-Carbonell and Frijters (2004), this research also employs ordinary least squares (OLS) estimation for Eqs. (1) and (2).

Variable selection

The dependent variable in this study is women’s intrahousehold bargaining power, assessed through both subjective and objective indicators within the NSWSS dataset. The subjective measure, referred to as Actual_power, assesses the respondent’s perception of who holds real authority in the family. This captures their overall assessment of power dynamics and responsibility distribution within the household. A score of 2 is given if the wife holds authority, 0 if it is the husband, and 1 if decisions are reached through mutual negotiations.

To complement this subjective measure, we utilize an objective indicator that assesses six distinct dimensions of household decision-making power, providing insights into the couple’s relative dominance in family affairs. These dimensions include daily household expenditure, staple commodity purchases, house purchase, and construction decisions, involvement in production and business activities, investment and loans, as well as choices related to children’s education and schooling. Respondents choose from three options: husband dominates, nearly equal, or wife dominates. Aligning with the Actual_power variable, we assign values of 0, 1, and 2 accordingly. Subsequently, we aggregate the scores from all six dimensions to construct a more objective indicator, denoted as Bargain_power.

The study’s explanatory variable is Internet usage (Internet_use). Within the NSWSS data, respondents’ Internet activity is gauged by the question: How much time do you spend online each day? Response options range from 0 (never go online), 1 (less than half an hour), 2 (half an hour to one hour), 3 (one to three hours), 4 (three to eight hours) to 5 (more than eight hours). The fifth option, selected by only 0.4% of respondents and considered an exceptional case, has been excluded from the sample. Thus, Internet_use is an ordered variable indicating the frequency of Internet use, ranging from 0 to 4, where a higher value signifies more frequent Internet use.

The mediating variables in this study are employment status (Employment), income level (Income)Footnote 3, and gender belief (Gender_befief). Employment status is defined as actively participating in paid work or labor, denoted as 1, whereas a status of 0 indicates non-engagement in such activities. The income level encompasses the entire annual income, comprising earnings from labor, rental income from houses, land, and cars, property income derived from stocks, bonds, and mutual funds, pension gratuities, unemployment insurance, minimum living security funds, agricultural subsidies, as well as other forms of support from family and friends. To mitigate the potential impact of extreme outliers, we employ a logarithmic transformation, specifically log (annual income + 1). Gender belief is evaluated through nine statements pertaining to gender equality, detailed in Table 2. To provide a comprehensive assessment of respondents’ gender beliefs, the scores from these nine statements are aggregated to create an ordered gender belief variable. The scale ranges from 12 (indicating the most conservative beliefs) to 36 (indicating the most egalitarian beliefs), where higher scores signify a more egalitarian perspective on gender. It is worth noting that the minimum value is not 9, as there is no respondent consistently expressing strong disagreement with all four statements supporting gender equality and strong agreement with all five statements opposing gender equality.

This study accounts for potential confounding factors, including individual characteristics, as well as family and community-level variables. Individual characteristic variables include urban hukou status (Urban, yes = 1, otherwise = 0), property ownership (Property, yes = 1, otherwise = 0), years of education (Education), age (Age). Family-level variables include whether the spouse owns property (Spouse_property, yes = 1, otherwise = 0), educational disparity between own and the spouse (Education_difference), age difference between own and the spouse (Age_difference), years of marriage (Marry_year), the extent to which the spouse is willing to listen, understand, and support each other (Spouse_understand, 3–12, higher values indicates the spouse is more willing to support each other)Footnote 4, whether the wife’s natal family had pre-marital economic advantages (Economy_advantage, yes = 1, otherwise = 0), and parents’ education level (Parents_education, 1–6)Footnote 5. Acknowledging that community norms and traditions can subtly shape individuals’ development and viewpoints, thereby indirectly impacting women’s bargaining power within the family, we use gender role beliefs in the community (Gender_befief_community) as a proxy for this environmental influence. It primarily mirrors the community’s stance on the appropriateness of gender roles in family and marriage, with a higher value indicating a community that leans towards more equal gender roles. The relationship between Gender_befief and Gender_befief_community is as follows: \({\rm {Gender}}\_{\rm {belief}}\_{\rm {community}} = \left[ {\left( {\left. {\mathop {\sum }\limits_{i = 1}^n {\rm {Gender}}\_{\rm {belief}}_i} \right) - {\rm {Gender}}\_{\rm {belief}}_i} \right)} \right]/\left( {n - 1} \right)\).

Descriptive statistics

Table 3 furnishes descriptive statistics for key variables in the primary regression model. These statistics encompass the mean, standard deviation, minimum value, 50th percentile (median), and maximum value. In the NSWSS data, the mean values for the dependent variables Actual_power and Bargain_power stand at 0.808 and 5.577, respectively, with corresponding medians of 1 and 6. This suggests that women tend to have relatively lower bargaining power within their households, reflecting the established societal structure in China where husbands traditionally oversee major household decisions, while wives primarily assume supportive roles such as managing household chores and caring for children. The mean value for the variable Internet_use is 0.592, indicating that the majority of women either do not use or use the Internet infrequently.

Furthermore, while 46.7% of women reside in urban areas, only 13.3% own property. In contrast, the proportion of husbands who own property is notably higher at 47.8%. In terms of education, women have an average of 7.734 years of schooling, while their husbands hold an educational advantage, boasting an additional 1.054 years of education. This suggests that, compared to their husbands, women face relatively greater disadvantages in terms of education and asset ownership. Regarding the external environment, a majority of community residents tend to hold traditional gender beliefs, implying that women often find themselves accepting the dominance of men in household affairs.

Figure 2 illustrates the scatter plot and fitted line between women’s Internet use with their intra-household bargaining power (Actual_power on the left, Bargain_power on the right). The upward-sloping straight line signifies a positive association between women’s bargaining power and their Internet usage. Along the X-axis, the frequency of women’s Internet use progressively increases from left to right, while their corresponding bargaining power rises from bottom to top along the Y-axis.

Empirical analysis and its interpretation

Baseline regression results

Table 4 provides the estimated results of Eqs. (1) and (2). It is evident that, after controlling for individual, familial, and community-level factors, Internet usage is positively associated with women’s bargaining power. Both the ordered logit and OLS regression results are consistent. Moreover, the OLS regression coefficients in Columns (2) and (4) further suggest that holding conditions constant, a one-unit rise in Internet usage frequency amplifies women’s household bargaining power by 0.028 and 0.082 units, respectively.

Addressing endogeneity issues

In the preceding analysis, we conducted correlation analysis while controlling for pertinent confounding variables. This allowed us to calculate the correlation coefficient between Internet usage and women’s bargaining power. However, to more effectively investigate the causal relationship between these variables, it is crucial to address potential endogeneity issues pertaining to Internet usage. These issues can manifest in two distinct ways:

Firstly, there might be a reciprocal cause-and-effect relationship between Internet usage and women’s bargaining power. This suggests that women’s bargaining power could also influence Internet usage in return. Women possessing greater bargaining power are more likely to have access to financial resources, affording them the opportunity to acquire and make use of internet-connected devices and services. Secondly, there may be concerns regarding omitted variables in the equation for women’s bargaining power, particularly those that are unobservable, e.g., non-cognitive abilities. If these unaccounted factors are correlated with Internet usage, it could result in biased coefficient estimates. To mitigate these concerns, this study identifies instrumental variables to more accurately capture the true causal relationship associated with Internet usage.

In this study, we create an interaction term between the number of fixed telephones and post offices per 10,000 people in each province in 1984 and the Internet penetration rate in the individual’s community in 2010. This term is subsequently employed as the instrumental variable for individual Internet usage in Eqs. (1) and (2). The original model is then re-estimated utilizing the instrumental variable ordered probit model (IV-oprobit). This instrumental variable is chosen due to its fulfillment of both correlation and exogeneity conditions.

Firstly, the instrumental variable exhibits a correlation with Internet access. Tracing the historical progression of Internet access technology in China, widespread accessibility initially relied on dial-up connections through landlines (PSTN), followed by ISDN, ADSL, and, eventually, fiber broadband technology. Thus, the advancement of Internet technology can be traced back to the proliferation of fixed telephones. Regions with historically high fixed telephone penetration rates are likely to also exhibit elevated Internet penetration rates.

Meanwhile, prior to the widespread availability of fixed telephones, postal systems served as the primary means of communication. The postal service was responsible for establishing fixed telephone lines, so the distribution of post offices, to some extent, influenced the availability of fixed telephones, consequently impacting early Internet access. In this context, the availability of both fixed telephones and post offices significantly influenced individuals’ ability to access the Internet, thereby predicting the level and extent of Internet development in a given region.

Additionally, we incorporate the inductive effect of Internet usage into the instrumental variable, namely, the Internet penetration rate in the individual community in 2010. This reflects the Internet usage habits of other residents in the community, exerting an influence on the individual’s decision regarding Internet use through peer effects. Consequently, both the prerequisite and inductive effects of Internet usage play a substantial role in an individual’s Internet usage behavior, thereby satisfying the relevance criterion of instrumental variables.

Secondly, the instrument is exogenous to women’s bargaining power. In contrast to the swift advancement of Internet technology and information technology transformations, historical metrics such as the density of fixed telephones and post offices per 10,000 people, along with the Internet penetration rate in 2010, represent higher-level external environmental variables. They typically exert limited direct influence on women’s decision-making authority within the family. Therefore, considering these historical metrics of fixed telephones and post offices as instrumental variables, after accounting for other variables, to some extent meets the exogeneity criterion.

As depicted in the regression outcomes presented in Table 5, the instrumental variables constructed in the first-stage model exhibit a positive impact on individual Internet usage. Moreover, the first-stage Cragg–Donald Wald F-values surpass 10, effectively dispelling concerns regarding weak instrumental variables. In the second-stage model, Internet usage demonstrates a positive influence on women’s bargaining power, with a coefficient larger than that in Table 4. This suggests that the endogeneity of Internet usage may lead to an underestimation of its impact on women’s bargaining power. However, beyond this explanation, the larger IV regression coefficients may also be attributed to the concept of local average treatment effect (LATE). For individuals who would use or not use the Internet regardless, the historical quantities of fixed telephones and post offices, along with the 2010 community Internet usage rate being high or low, will not alter their decisions. This exemplifies a typical case of a local average treatment effect, where the results primarily pertain to those influenced by the instrumental variable in changing their Internet usage behavior. To summarize, the regression results employing instrumental variables consistently indicate that internet usage significantly enhances women’s bargaining power.

To bolster the resilience of our findings, we extend our analysis to include IV-oprobit estimates for all six sub-indicators of women’s intra-household bargaining power concerning their Internet usage. Except for the dimension related to children’s education and schooling, the comprehensive results presented in Table 6 consistently highlight the correlation between Internet usage and the enhancement of women’s influence across the mentioned family domains.

Testing the influencing pathways

To explore the mechanisms connecting Internet use and women’s bargaining power, we utilize causal mediation analysis within the counterfactual framework, introduced by Imai et al., (2010). This method avoids assumptions about equation form or parameter distribution and adeptly handles discrete mediating and outcome variables. It provides causal mediation effects under the assumption of sequential ignorability. Building on this, this study estimates the average causal mediation effect (ACME) and average total effect (ATE) of Internet usage on women’s bargaining power, following Kosuke et al. (2010)’s work.

Prior to estimating these effects, the study identifies predetermined confounding variables (X) in both the mediating and outcome variable equations. These encompass individual-level factors (urban household registration, property ownership, education years, age, and health status), family-level aspects (spouse’s property ownership, education years, age, children and daughters count, marriage duration, spouse’s willingness to listen, understand, and support, and average parental education), and community-level factors (community-level gender role beliefs). Subsequently, the study follows a three-step process within the counterfactual framework to estimate the causal mediation effects.

First, a measured regression of the mediating variable M (comprising women’s employment status, income level, and gender beliefs) is conducted in the following form:

This indicates that the mediating variable M is influenced by both the treatment variable, Internet_use and the predetermined confounding variable X. Given this, the study generates two sequences of predicted values for the mediating variable, corresponding to women who use the Internet (M(1)) and those who do not (M(0)).

Secondly, the study employs the following regression equation to estimate women’s bargaining power Y:

This implies that the outcome variable Y is influenced by the mediating variable M, the treatment variable Internet_use, and all predetermined confounding variables X. After obtaining the predicted values of women’s bargaining power for Internet-using women (Y(1, M(1))) and the predicted values of the two mediating variables from the first step, predicted values for the outcome variable are generated under the counterfactual scenario of the mediating variable. In this scenario, the treatment variable remains Internet usage, but the mediating variable corresponds to the predicted values of bargaining power for women who did not use the Internet in the first step (Y(1, M(0))).

Thirdly, by comparing the average difference in predicted values of the outcome variable under the two mediating variable scenarios, the average causal mediation effect of Internet usage is calculated. This is expressed mathematically as follows:

Table 2A in the Appendix exhibits the outcomes of the causal mediation analysis. In Panels A–C, Columns (1) illustrate that Internet usage elevates the likelihood of women being employed, achieving higher income, and embracing egalitarian gender beliefs. Columns (2) and (3) demonstrate a positive connection between women’s employment status, income levels, and egalitarian gender beliefs with their bargaining power. Simultaneously, Internet usage exhibits a positive correlation with women’s intra-household bargaining power.

Table 7 presents the average causal mediation effects (ACME), average total effects (ATE), and the proportion of the mediation effects (ACME/ATE) of three mediators. The following conclusions can be drawn: Firstly, overall, Internet usage positively impacts women’s bargaining power (ATE is positive), confirming Hypothesis 1 proposed in this study. Internet usage influences women’s bargaining power through changes in women’s employment status, income level, and gender beliefs (significant ACME), supporting Hypothesis 2.

Moreover, this study rigorously quantifies the specific contributions of each mediating variable in elucidating the impact of Internet usage on women’s bargaining power. This is pivotal in comprehending the underlying mechanisms of women’s empowerment facilitated by Internet use. Approximately 11.435%Footnote 6 of this influence is channeled through shifts in women’s gender beliefs, underscoring how Internet usage liberates women from entrenched traditional norms, gradually fostering a sense of personal autonomy, and bolstering their negotiating power within marital relationships. In parallel, women’s income level and employment status contribute 9.88% and 3.085%, respectively, to the mediating pathways through which the Internet influences women’s bargaining power.

Heterogeneity analysis

Given the regional disparities in China, the influence of the Internet on household bargaining power may vary significantly. To provide more targeted policy recommendations, this study delves into the differential impacts of Internet usage on women’s intrahousehold bargaining power, with a specific focus on urban-rural distinctions. The IV-based estimation results for both urban and rural areas are presented in Table 8. It is evident that Internet_use is not statistically significant in urban areas, but shows significance in rural areas. We further elaborate on the reasons behind this heterogeneous effect of Internet use on women’s bargaining power.

It is found that factors like information exposure and awareness of gender equality significantly influence women’s involvement in family matters (Li, 2023a). Urban areas inherently possess higher levels of gender equality awareness, attributed to factors like increased education and exposure to new ideas (Du et al., 2021). As a result, the influence of modern media tools, such as the Internet, on their household decision-making behavior tends to be comparatively moderate. In contrast, rural communities have limited exposure to new information, and the mainstream traditional media they rely on often adhere to entrenched gender norms. This results in reduced participation in the household decision-making process. However, with the widespread use of the Internet, rural communities are expanding their information exposure and adopting concepts of gender equality. A diverse range of information concerning women in disadvantaged positions is gradually becoming accessible to rural residents, significantly reshaping their involvement in household affairs. This surge in exposure directly correlates with increased participation in family matters. Therefore, the influence of Internet usage on household bargaining behavior among rural women is more pronounced.

Robustness checks by using the CFPS dataset

In the CFPS dataset, this study scrutinizes five key areas of household decision-making: household expenditure allocation, savings, investments and insurance, house purchases, and children’s upbringing, as well as high-value consumer goods acquisition. A score of 3 is assigned if the wife solely makes decisions in a specific area, 2 if decisions are made through negotiation, and 1 if the husband is the primary decision-maker. These scores are aggregated to construct a comprehensive variable (Bargain_power_cfps), ranging from 5 to 15. A higher value signifies a greater degree of women’s bargaining power.

Internet usage in the CFPS data is assessed through the question: Do you use the Internet? Respondents choose between Yes and No, corresponding to values of 1 and 0, respectively. Therefore, in the CFPS, the explanatory variable is a binary variable indicating whether the individual uses the Internet (Interne_use_cfps).

The control variables that align with those in Table 4 comprise Urban, PropertyFootnote 7, Education, Education_difference, Age, Age_difference, Marry_year, and parents_educationFootnote 8. Furthermore, considering the accessibility of CFPS data, additional control variables encompass interpersonal relationship (Relationship, 0–10, where higher values indicate better relationships), spouse’s interpersonal relationship (Spouse_relationship, defined similarly to Relationship), emphasis on family harmony and happiness (Family_harmony, 1–5, where higher values indicate greater importance placed by respondents on family harmony and happiness), as well as the community’s leanings towards traditional family ethics (Family_ethics_community). A person’s family ethical attitudes (Family_ethics, 6–30) are evaluated through six statements that reflect the dynamics between children and parents. These statements inquire about the extent of agreement with the following beliefs: (1) Regardless of how poorly parents treat their children, children should still treat them well, (2) Children should give up their personal ambitions to fulfill their parents’ wishes, (3) Sons should live with their parents after getting married, (4) To continue the family lineage, having at least one son is necessary, (5) People should undertake actions to honor their ancestors and (6) Even if working elsewhere, children should regularly visit their parents at home. Each statement is scored positively, with strongly disagree as 1, disagree as 2, agree as 3, quite agree as 4, and strongly agree as 5. The scores from these six statements are then totaled to create an ordered variable representing family ethical attitudes. The resulting scores range from 6 to 30, with higher scores indicating a more traditional perspective on family ethical attitudes at the individual level. Likewise, the relationship observed between Gender_belief_community and Gender_belief similarly applies to that between Family_ethics and Family_ethics_community. Table 3A in the Appendix showcases the descriptive statistics of the main variables.

To mitigate potential endogeneity bias, we also employ the IV-oprobit for estimation, using the same instrument as before. Table 9 presents the estimated results concerning the impact of Internet usage on women’s bargaining power, based on the CFPS data. It is evident that Internet usage significantly enhances women’s bargaining power. Thus, the findings from the NSWSS are further corroborated by the CFPS data.

To reinforce our conclusion, we explore the effects of Internet usage on the five distinct sub-dimensions of women’s authority in household decision-making. The IV-oprobit estimates regarding Internet usage are delineated in Table 10. Remarkably, the coefficients associated with Internet usage showcase significant positivity across all five sub-indicators of intra-household decision-making power. This additional evidence serves to further validate our findings.

Conclusion and implications

Drawing on data from the 2010 NSWSS, along with the 2014 CFPS, this study explores the impact of Internet usage on women’s bargaining power. Utilizing a range of metrics from both datasets to assess women’s bargaining strength, the study consistently reveals that Internet usage plays a significant role in bolstering women’s bargaining power. Addressing potential endogeneity concerns associated with Internet usage through instrumental variable methodology, the IV-oprobit estimation results further affirm the crucial role of the Internet in enhancing women’s bargaining power.

To probe into the mechanisms through which the Internet influences women’s bargaining power, the study employs causal mediation analysis within a counterfactual framework to quantify the contribution of mediators to the overall effect. The findings of this analysis underscore that employment status, income, and gender belief act as pivotal mediators in the pathway through which the Internet affects women’s bargaining power. The positive influence of Internet use on women’s bargaining power exhibits heterogeneity, especially among rural women compared to their urban counterparts. This is attributed to the fact that rural women can leverage the internet to greatly access new information pertaining to gender equality and market opportunities.

Building upon these research findings, we advocate for policies aimed at narrowing the digital gender gap, empowering rural women through enhanced Internet access for economic and educational prospects, and fostering their engagement in promoting gender equality and personal development. These policy recommendations revolve around three key dimensions:

Firstly, enhancing Internet infrastructure: Government initiatives should focus on expanding and improving Internet infrastructure, reducing costs, and enhancing connectivity speed. Special attention should be given to rural areas, ensuring that women in remote regions have access to free Internet. This can be achieved by subsidizing Internet services or establishing community Internet centers in rural locations, aimed at increasing female Internet usage.

Secondly, promoting access to quality online resources: Policies should ensure access to high-quality online educational resources for women, especially rural women. This might involve subsidizing online courses or providing free access to educational platforms. Additionally, advocating for policies that promote the free accessibility of Internet resources to the public ensures that rural women have access to the latest ideas and trends. This intellectual exposure is crucial for advocating gender equality and fostering personal development and well-being among rural women.

Thirdly, supporting Internet-based industries: The government should encourage the growth of industries reliant on the Internet, providing incentives that promote diverse employment opportunities. By facilitating legal and compliant Internet-based income generation for women, it broadens their financial avenues and reinforces their bargaining power within households. Initiatives could include subsidizing training programs for women in digital skills or providing tax incentives for Internet-based businesses that employ women.

Nevertheless, it is crucial to highlight that the issue of Internet policy issued by the Chinese government greatly intersects with the potential for Internet usage to empower women. While utilizing the Internet can undoubtedly act as a catalyst for women’s empowerment, providing access to information, education, networking, and advocacy platforms, the specific landscape of Internet governance and regulations in China significantly influences the extent of this empowerment. China’s Internet policies, known for stringent censorship and regulation methods such as the Great Firewall, exert substantial control over online content and discourse. This tight control has the potential to restrict women’s access to critical information, educational resources, and platforms that could otherwise contribute significantly to their empowerment. Constraints on free expression and the suppression of diverse voices online may also dampen discussions and initiatives concerning gender equality and women’s rights. Hence, while Internet usage can serve as a conduit for women’s empowerment, the specific context of government policies, particularly in China, introduces multifaceted complexities and obstacles. Discussions regarding the relationship between Internet usage and women’s empowerment must encompass considerations of the regulatory environment and the potential barriers imposed by government policies. These are crucial in understanding and addressing the challenges that impact the realization of empowerment objectives for women in the digital sphere.

The paper offers interesting insights, though it has some noteworthy limitations. Firstly, the dataset’s timeliness is a consideration; it dates from 2010 and 2014, potentially not capturing the current situation in 2023. However, recent studies suggest that Chinese family dynamics have been evolving gradually (Yu and Xie, 2021). Internet usage and its benefits in social and economic aspects are on an upward trajectory, indicating the positive effect is likely to persist. Nevertheless, future research will prioritize employing the latest surveys for more current empirical examinations.

Secondly, it is important to consider the generalizability of the findings. The study’s applicability to different cultures is a key consideration. It focuses on the relationship between Chinese women’s Internet use and their influence on family dynamics. Power dynamics in families are significantly shaped by cultural norms and moral guidelines (Agarwal, 1997). While some Northern European countries demonstrate near parity in household power dynamics, this diversity cautions against the universal application of our findings. Nonetheless, our research may offer valuable insights into countries with comparable cultural contexts, particularly in Eastern Asia.

Data availability

The authors confirm that the data and code supporting the findings of this study are available at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/YA3VBL.

Notes

2018 Chinese Household Financial Market Analysis Report, China Banking News, November 15, 2018. Retrieved from https://www.chinabankingnews.com/2018/11/05/women-control-finances-60-chinese-households/.

The 52nd Statistical Report on China’s Internet Development, August 2023. Retrieved from https://www.cnnic.com.cn/IDR/ReportDownloads/202311/P020231121355042476714.pdf.

The unit of measure is Chinese Yuan.

It is assessed by asking the respondents to indicate their level of agreement with three statements: (1) The spouse listens to your feelings and worries, (2) The spouse seeks your opinion on important matters, and (3) Your desires are generally supported by the spouse. Each statement offers four response options: strongly disagree, disagree, agree, and strongly agree, corresponding to assigned values of 1–4, respectively. The scores from these statements are totaled to create the variable.

The highest education level among both parents, illiterate = 1, primary school = 2, junior high school = 3, high school or technical secondary school = 4, junior college = 5, and bachelor degree or above = 6.

The number is obtained by averaging the mediating effect of gender belief in Actual_power and Bargain_power. It is similar for employment status and income level.

It is important to note that Property in the CFPS differs slightly in item formulation from its corresponding variable in the NSWSS data. In the CFPS, Property is measured by the question: Do you own any property besides the current residence?' Additionally, under this definition, Spouse_property and Property are completely collinear, hence we only control for the Property variable.

In the CFPS dataset analysis, three variables, Marry_year, Parents_education, and Family_harmony, are sourced from the adult database of CFPS 2010, while the remaining variables are from CFPS 2014.

References

Agarwal B (1997) “Bargaining” and gender relations: within and beyond the household. Fem Econ 3(1):1–51

Apps PF, Rees R (1988) Taxation and the household. J Public Econ 35(3):355–369

Atasoy H (2013) The effects of broadband Internet expansion on labor market outcomes. ILR Rev 66(2):315–345

Bailur S, Masiero S (2017) Women’s income generation through mobile Internet: a study of focus group data from Ghana, Kenya, and Uganda. Gend Technol Dev 21(1-2):77–98

Bargain O, Lacroix G, Tiberti L (2022) Intrahousehold resource allocation and individual poverty: assessing collective model predictions using direct evidence on sharing. Econ J (Lond) 132(643):865–905

Becker GS (1981) A treatise on the family. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA

Benstead LJ, Muriaas R, Wang V (2023) Explaining Backlash: social hierarchy and men’s rejection of women’s rights reforms. Soc Politics 30(2):496–524

Billari FC, Giuntella O, Stella L (2019) Does broadband Internet affect fertility? Popul Stud 73(3):297–316

Carlson DS, Grzywacz JG, Michele Kacmar K (2010) The relationship of schedule flexibility and outcomes via the work–family interface. J Manag Psychol 25(4):330–355

Chen Z, Park A (2023) Rural pensions, intra-household bargaining, and elderly medical expenditure in China. Health Econ 32(10):2353–2371

Chhaochharia V, Du M, Niessen-Ruenzi A (2022) Counter-stereotypical female role models and women’s occupational choices. J Econ Behav Organ 196:501–523

Chiappori P-A (1988) Rational household labor supply. Econometrica 56(1):63–90

Chiappori P-A (1992) Collective labor supply and welfare. J Polit Econ 100(3):437–467

Coenen M, Kok RAW (2014) Workplace flexibility and new product development performance: the role of telework and flexible work schedules. Eur Manag J 32(4):564–576

Denzer M, Schank T, Upward R (2021) Does the internet increase the job finding rate? Evidence from a period of expansion in internet use. Inf Econ Policy 55:100900

Dhanaraj S, Mahambare V (2022) Male Backlash and Female Guilt: women’s employment and intimate partner violence in urban India. Fem Econ 28(1):170–198

Dong X (2022) Intrahousehold property ownership, women’s bargaining power, and family structure. Labour Econ 78:102239

Donni O, Molina JA (2018) Household collective models: three decades of theoretical contributions and empirical evidence. IZA Discussion Papers No. 11915

Du H, Xiao Y, Zhao L (2021) Education and gender role attitudes. J Popul Econ 34(2):475–513

Erten B, Keskin P (2018) For better or for worse?: education and the prevalence of domestic violence in Turkey. Am Econ J Appl Econ 10(1):64–105

Ferrer-i-Carbonell A, Frijters P (2004) How important is methodology for the estimates of the determinants of Happiness? Econ J (Lond) 114(497):641–659

Galloway L, Sanders J, Deakins D (2011) Rural small firms’ use of the internet: From global to local. J Rural Stud 27(3):254–262

Gheytanchi E, Moghadam VN (2014) Women, social protests, and the new media activism in the Middle East and North Africa. Int Rev Mod Sociol 40(1):1–26

Golin M (2022) The effect of broadband Internet on the gender gap in mental health: evidence from Germany. Health Econ 31(S2):6–21

Imai K, Keele L, Tingley D (2010) A general approach to causal mediation analysis. Psychol Methods 15(4):309–334

Kabeer N (1999) Resources, agency, achievements: reflections on the measurement of women’s empowerment. Dev Change 30(3):435–464

Kosuke I, Luke K, Teppei Y (2010) Identification, inference and sensitivity analysis for causal mediation effects. Stat Sci 25(1):51–71

Li Z (2023a) Does self-esteem affect women’s intra-household bargaining power: evidence from China. Appl Econ. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036846.2023.2187040

Li Z (2023b) Family decision making power and women’s marital satisfaction. J Fam Econ Issues 44(3):568–583

Liu J, Cheng M, Wei X, Yu NN (2020) The Internet-driven sexual revolution in China. Technol Forecast Soc Change 153:119911

Mabsout R, van Staveren I (2010) Disentangling bargaining power from individual and household level to institutions: evidence on women’s position in Ethiopia. World Dev 38(5):783–796

Matjasko JL, D’Inverno AS, Marshall KJ, Kearns MC (2020) Microfinance and violence prevention: a review of the evidence and adaptations for implementation in the U.S. Prev Med 133:106017

Melissa E, Hamidati A, Saraswati MS, Flor A (2015) The Internet and Indonesian women entrepreneurs: examining the impact of Social Media on women empowerment. In: Chib A, May J, Barrantes R (eds) Impact of Information Society Research in the global south. Springer Singapore, Singapore, pp. 203–222

Moeeni S (2021) Married women’s labor force participation and intra-household bargaining power. Empir Econ 60(3):1411–1448

Molina JA, Velilla J, Ibarra H (2023) Intrahousehold bargaining power in Spain: an empirical test of the collective model. J Fam Econ Issues 44(1):84–97

Nguyen M, Le K (2023) The impacts of women’s land ownership: evidence from Vietnam. Rev Dev Econ 27(1):158–177

Nisbet EC, Stoycheff E, Pearce KE (2012) Internet use and democratic demands: a multinational, multilevel model of Internet use and citizen attitudes about democracy. J Commun 62(2):249–265

Palvia S, Aeron P, Gupta P, Mahapatra D, Parida R, Rosner R, Sindhi S (2018) Online education: worldwide status, challenges, trends, and implications. J Glob Inf Technol Manag 21(4):233–241

Parada C (2023) Cash transfers and intra-household decision-making in Uruguay. J Fam Econ Issues 44(3):757–775

Robertson BW, Kee KF (2017) Social media at work: the roles of job satisfaction, employment status, and Facebook use with co-workers. Comput Hum Behav 70:191–196

Saelens D (2022) Unitary or collective households? A nonparametric rationality and separability test using detailed data on consumption expenditures and time use. Empir Econ. 62(2):637–677

Shuangshuang Y, Zhu W, Mughal N, Aparcana SIV, Muda I (2023) The impact of education and digitalization on female labour force participation in BRICS: an advanced panel data analysis. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 10(1):1–9

Staveren IV, Ode bode O (2007) Gender norms as asymmetric institutions: a case study of Yoruba women in Nigeria. J Econ Issues 41(4):903–925

Viollaz M, Winkler H (2022) Does the Internet reduce gender gaps? The case of Jordan. J Dev Stud 58(3):436–453

Wang S-Y (2014) Property rights and intra-household bargaining. J Dev Econ 107:192–201

Yu J, Xie Y (2021) Recent trends in the Chinese family: national estimates from 1990 to 2010. Demogr Res. 44:595–608

Zhou D, Peng L, Dong Y (2020) The impact of Internet usage on gender role attitudes. Appl Econ Lett. 27(2):86–92

Acknowledgements

The work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (42001118, 72304001), the Advance Research Fund for Humanities and Social Sciences of Zhejiang University of Technology (SKY-ZX-20220243), Zhejiang University of Technology Foundation (GB202301003).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ZL is responsible for conceptualizing, designing, implementing, and composing the paper, while FL is tasked with cleaning the dataset and conducting result analysis.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, Z., Lu, F. The power of Internet: from the perspective of women’s bargaining power. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11, 169 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-02670-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-02670-w

- Springer Nature Limited