Abstract

Using Industrial Revolution 4.0 (IR4.0) technology, companies can upscale their innovation in organizing, managing, and controlling the value chain life cycle. IR4.0 is anticipated to bring challenges and opportunities to developing economies such as Malaysia, but due to its novelty to the Malaysian business community, the concept still needs clarity in its definition for proper understanding and business practice. This paper aims to examine the impact of IR4.0 adoption on Malaysian small and medium enterprises (SMEs) by analyzing the organizational readiness, relative advantage, compatibility, top management support, government regulation, and competitive pressure, and its relationship with the adoption of IR4.0 to Malaysian SMEs. This study framework is based on the diffusion of innovation theory (DOI) and technology–organization–environment (TOE) framework. The study results verified the importance of relative advantage, compatibility, competitive pressure, and top management support as significant predictors of IR4.0 adoption. The study is expected to benefit regulators and business ecosystems in understanding the challenges in implementing IR4.0 in Malaysia and formulating intervention processes and programs for successful IR4.0 adoption.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Starting point of considerations

The Industrial Revolution 4.0, or IR4.0, is no longer new. By using the IR4.0 technology, organizations can upscale their innovation in organizing, managing, and controlling the value chain life cycle. IR4.0 has brought significant social and economic opportunities and challenges, requiring governments to respond appropriately (Manda and Dhaou, 2019). It brings convenience to the table and acts as a trendy mechanism towards smart technology, which not only has doubled productivity but also increased efficiency, but at the same time, has shortened production times hence improving the organization’s income (Sima et al., 2020).

The Malaysian manufacturing sector is vital to the country’s economy and significantly contributes (23.47% in 2021) to the national gross domestic product (GDP). It is expected to contribute more than 50% by 2025, proving Malaysia is a developed nation. As for 2021, the manufacturing sector has recorded a growth of sales, which is RM $87.53B billion compared to the year 2020 increase. Manufacturers must revolve and improve to ensure the manufacturing sector keeps growing and contributing to the development of Malaysia at large. Regarding the improvement, IR4.0 shall be the new norm and culture to enhance and enrich the manufacturing sector. Challenges of adapting IR4.0 among Malaysian companies, especially Malaysian manufacturing SMEs, have generally been discussed in many forums (Ling et al., 2020). Effectiveness and efficiency of manufacturing SMEs, there are still few studies in Malaysia that specifically look into the adoption of IR4.0 among SMEs.

However, only 30% of Malaysian manufacturing SMEs have just started the adoption of Industrial 3.0, which covers the adoption of advanced technology (United Nation Industrial Development Organization, 2016). This low adaptation rate indirectly shows Malaysia lags in its adoption process. Because IR4.0 is considered a new concept to the manufacturing industry in Malaysia, the business entities may have a shortage of knowledge about the exact impacts and cost-effectiveness of adopting IR4.0 related to the technologies to their business (Dalenogare et al., 2018; Hamim et al., 2021).

Based on a governmental report, the national adoption rate in Malaysia for IR4.0 was between fifteen (15) to twenty (20) percent, mainly by tier-one companies. However, it had been almost a year after the Government of Malaysia, through the Ministry on International Trade and Industry (MITI), introduced a National Policy on IR4.0, better known as the Industry4WRD. Less than 21% of SMEs reportedly implemented IR4.0 initiatives in some production-related processes (MITI, 2018).

In the context of the insignificant growth and lower technology adoption rate (Furuholt and Orvik, 2006), competencies, literacy, and business skills to stay on top of the game (Duncombe and Heeks, 2003). The slow adoption can also be caused by top management of the organization, organizational readiness, and government regulation (Deakins et al., 2003; Hawkins and Prencipe, 2000). The government’s inadequate focus on digital literacy and innovation has led to sluggish technology adoption and a potential workforce unprepared for IR4.0, resulting in employees being unable to familiarize themselves with quick technology changes. It indicates either resistance to change, a low level of interest, or a low level of readiness at the organizational level, ultimately leading to sluggish implementation at the national level. In general, smaller firms tend to be more receptive, flexible, and easier to adopt new technologies than larger firms (Narula, 2004; Lin, 2006; Nagayya and Rao, 2013; Yu and Schweisfurth, 2020).

The lower rate of IR4.0 is adopted based on the lack of external support and lower awareness of available government channels and initiatives for the adoption process. The business community claimed to be unaware of proper channels for fund disbursement for technology upgrades related to IR4.0 and the confusion caused by many government machinery agencies taking the lead for IR4.0 implementation. Through MITI, Malaysia’s government has conducted an essential program for IR4.0 adoption, i.e., Industry4WRD Readiness Assessment. The program has done an on-site assessment and produced an Industry 4.0 readiness report with recommendations for improvements. The government will subsidize qualified SMEs for this initiative. As of October 2019, 47% of Malaysian manufacturing companies have yet to have the knowledge and are not aware of the program. From the statistics, it is said that there were only 3.6% in the midst of applying for it (MITI, 2019).

Problem formulation and research question

Based on the readiness assessment, it is tough and challenging for Malaysian SMEs to seek IR4.0 potential, as it requires significant technology and talent investment. Besides that, elements such as I.T. competencies, a strategic company vision, support from high-level management, and whether the organization is ready to embrace the transformation development must be considered before implementing any technology adoption (Balasingham, 2016; Ling et al., 2020).

As the study measures the adoption of IR4.0 among SMEs in Malaysia, it primarily aims to understand the factors and attributes that might influence the choice of adoption based on the DOI and Technology-Environment-Organization (TOE) framework (Tornatzky et al., 1990). Thus the following research questions will be answered by our study:

-

a.

How can the adoption of IR4.0 among Malaysian SMEs be defined and measured, including technological factors, relative advantages, and compatibility?

-

b.

What are the organizational adoption aspects of the adoption of IR4.0? In particular, what is the role of organizational readiness and top management support?

-

c.

What are the environmental factors for the adoption of IR4.0? In particular, what is the role of competitive pressure and governmental regulation?

We developed and empirically validated a conceptual model based on survey results amongst more than 120 Malaysian SMEs to answer these research questions. The remainder of the paper is as follows: After introducing the problem background and the research questions, we first discuss the results of a literature review on IR4.0 from a Malaysian point of view. Afterward, we derive a conceptual model and its underlying hypotheses. Then, we present our methodological setup, sampling procedures, and variables, followed by the results of our analysis and their discussion. The paper ends by showing this study’s main contributions, an answer to the research question, and an outlook for future studies.

Literature review

Overview of IR4.0

Industry Revolution 4.0 involves digitalizing manufacturing procedures and activities to the next level. The phase of digitalization consists of automation that modernizes the processes via the introduction of customization and flexible mass production with the utilization of high technologies. Industrial Revolution 4.0 will bring huge potential, opportunities, and benefits for businesses, especially SMEs. Production optimization is one of the company’s benefits in adopting smart production (Balakrishnan et al., 2021). There are nine elements under IR4.0. These include big data analytics, the Internet of Things (IoT), cloud computing, autonomous robots, additive manufacturing, simulation, augmented reality, horizontal and vertical system integration, and, last but not least, cybersecurity. IR4.0 can encourage automation through autonomous robots while reducing the dependency on humans, eliminating human error (Pech and Vrchota, 2020; Gilchrist, 2016).

The principal characteristics of IR4.0 are collaboration and integration. Core technologies and examples of business applications are big data analytics, cloud technology, autonomous robots, simulation, additive manufacturing, augmented reality, business intelligence, cyber security, and the industrial Internet of Things (IIoT) (Montreuil, 2011). Big data and analytics enable the organization to make business strategies using the data gathered. Businesses can understand consumer behavior better and tailor marketing strategies proactively through machine learning tools. Through cloud computing, companies can outsource I.T. services to cloud providers, which allows them to keep the focus on the core business. At the same time, cybersecurity can help the company ensure that their essential data, such as customer and sensitive data, is much more secure (Alcácer and Cruz-Machado, 2019; Kleindienst and Ramsauer, 2016). The advanced technology brings many new capabilities, including traceability prototyping and development, new product design, preventive maintenance services, diagnosis, agility, real-time applications, health monitoring systems, and innovation (Ghadge et al., 2020). The capabilities realized by IR4.0 introduce advantages to an organization, including autonomous control and monitoring, increased visibility, product customization, dynamic product design, and real-time data analysis (Bahrin et al. (2016); Dalenogare et al., 2018).

IR4.0 started in the year 2012 when future industry development trends characterized the 4th Industrial Revolution to achieve more intelligent manufacturing processes, including reliance and construction of Cyber-Physical Systems and the implementation and operation of smart industries that use advanced techniques and technologies (Nagy et al., 2018; Schwab, 2016; Zhou et al., 2015). The whole idea was believed to be an integrated, optimized, and service-oriented manufacturing activity with the implementation of a list of advanced technologies (Alcácer and Cruz-Machado, 2019; Sima et al., 2020). IR4.0 has been defined as the new chapter in the digitalization of the manufacturing sector. It brings a promisingly exponential increase in efficiency and productivity, particularly to small and medium enterprises (SMEs). By embracing IR4.0, SMEs would have a better opportunity to increase their productivity and efficiency.

Hence Malaysian SMEs are also required to adapt to the changes brought by IR4.0. Many manufacturing entities, especially small and medium-sized companies, are informed and have basic knowledge of IR4.0. Unfortunately, from the statistics, only 30% of Malaysian SMEs started at the level of Industrial 3.0, which covers the adoption of advanced technology. Only 10% of Malaysian manufacturing companies are adopting one of the IR4.0 essential elements: information communication technology (ICT). This rate is relatively low compared to some Asian developed countries like Singapore, South Korea, and Japan. Their SMEs’ adoption of I.T. is at 50%.

Malaysian SMEs and IR4.0

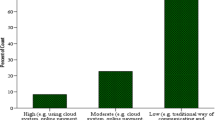

As for today’s Malaysian SME environment, innovation is defined as continuous and the percentage of contribution to the nation’s GDP, exports, and job creation. This definition has also been spelled out in the SME Masterplan by SME Corporation Malaysia. The characteristic of developed nations also defines SMEs’ elements in the country, which is also related to contribution to GDP, export contribution, and employment contribution. Relevant Malaysian SMEs statistics are shown in Figs. 1 and 2.

Malaysia SMEs definition (SME Corporation Malaysia, 2022a).

Small and medium enterprises (SMEs) performance (SME Corporation Malaysia, 2022b).

The numbers show that more than 900,000 business entities were operating in Malaysia. This number represents more than 98% of the total business establishments in the country. The actual cuts across all sizes and sectors in which microenterprises recorded nearly 700,000 (~77%), small businesses at more than 190,000 (21%), and medium-size companies recorded about 21,000 (2%).

Furthermore, SMEs in Malaysia contributed more than 36% to the country’s gross domestic product (GDP), more than 18% to the nation’s exports, and employed about 4.6 million workers or two-thirds of the total employment in Malaysia. These statistics show that SMEs’ roles and presence are significant to the nation’s development and economy.

Due to COVID-19, the SME’s GDP decreased by 1% in 2020 before increasing again by more than 4% in 2021 and is projected to grow next to 6% by 2022. By looking at this situation, adopting IR4.0 and the company embarking on IR4.0 could be an alternative key to bringing back Malaysian SMEs on the right track (DSM, 2020; Samsudin et al., 2021).

SMEs in Malaysia are known and aware of the IR4.0 concept, as reported in SME Bank Biz Pulse Issue 17 by Entrepreneur Development Division SME Bank. However, only 30% of Malaysian manufacturing SMEs have just started adopting Industrial 3.0, which covers the adoption of advanced technology (Abod, 2016). According to the Malaysia Productivity Corporation (MPC), adopting I.T. among Malaysian manufacturing SMEs is relatively low, at only 10%. Compared to some developed Asian countries such as Singapore, Japan, and South Korea, Malaysia is far from the total adoption of 50% recorded by such a country (EMP, 2018). It has also been published that the low levels of automation and modernization in manufacturing processes also inhibit awareness and knowledge regarding IR4.0 (Ling et al., 2020).

In October 2018, Malaysia’s 6th Prime Minister, Y.A.B Tun Dr. Mahathir Mohamad, launched the National Policy on Industry 4.0, or branding known as Industry4WRD. Malaysia’s blueprint provides a concerted and comprehensive transformation plan for the manufacturing sector and its related services. Indusrty4WRD envisions Malaysia as a strategic partner for intelligent manufacturing and has become a central hub for high-tech industries. The policy also envisions making Malaysia ready as a champion of solution providers for the region’s manufacturing industry and manufacturing-related services (MITI, 2018).

Conceptual model

Overview

In this study, we identify six independent variables that hypothetically affect the adoption of IR4.0 among SMEs in Malaysia, and we embed our model in a theoretical framework of technological, organizational, and environmental factors (see next section).

The first one is a relative advantage. Relative advantage is critical for adoption exercise (Baker, 2012; Nimfa et al., 2020). Firms that intend to transform to the new technology might be intensely affected by the technology’s sensed benefit to the firm’s performance. The second element is compatibility. The compatibility of manufacturing equipment and machinery indicates the equivalence with the firm’s production process and current practices (Chen et al., 2015). Compatibility is among the significant drivers of technology adoption (Gibbs et al., 2007). The ability and readiness of firms to adapt to brand-new technology is the definition of organization readiness, according to (Haddad et al., 2018). It exemplifies the organization’s capability to measure, plan, execute, and manage the entire adoption process, including I.T. capacity and ability and specialized expertise (Senarathna et al., 2018)

Top management support can be a significant attribute that affects the adoption of IR4.0. The high level of decision-maker and control in the organization’s support means extending understanding and support to high-tech technology competencies (Barham et al., 2020). Support from the organization’s decision-maker is one of the crucial I.T. adoption predictors (Hussein et al., 2019). Competitive pressure in the study means the “influences from the external environment that prompt the organization to use IR4.0 technology.” In other words, it is the stress from its customers, contractors, and competition. Empirical evidence shows a positive relationship between competitive pressure and technology adoption. Hussain et al. (2020) revealed that competitive pressure is one of the influencing factors in technology adoption. Government regulations may be unpopular but can be the reason for some and make an organization venture into new technology. Government regulations crafted with the proper measurement and execution can comprehensively become essential drivers for adopting innovation and the latest technology.

Diffusion of innovation (DOI) theory

Diffusion of innovation theory (DOI) follows Roger’s (2003) notions of an innovation, which is considered “an idea, practice, or object that is perceived to be new by an individual or another unit of adoption” (Rogers, 2003). Roger’s (2003) suggestion of diffusion being a communication process amongst social system members is used. The adoption of innovations is a consequence of its diffusion. However, it implies the users’ decision to accept and employ the innovation (see Bødker and Bøving, 2003). The theory of DOI has been tested in several studies related to information system adoption on mobile applications and e-learning using mobile banking apps (Luong and Wang, 2019; Mohtaramzadeh et al., 2018).

Technology–organization–environment (TOE) framework

We chose as the theoretical foundation the TOE model developed by Tornatzky et al. (1990). Figure 3 illustrates the framework. The framework includes characteristics specific to the technology examined in the study, consisting of internal and external technologies with existing practices and internal equipment and technologies made available externally to the firm.

Technology, organization, and environment framework (Tornatzky et al., 1990).

Three (3) areas are identified in the framework, resulting in enterprises’ technology adoption and innovation processes. The areas identified were namely technology, organization, and environment. The framework incorporates issues relating to the adopting organization, including concise organizational steps such as scale, management structure, and scope (Oliveira and Martins, 2011). Behaviors within the firm’s external environment impacting the adoption rate, i.e., the environmental context of the organization, include its industry, competitors, and dealings with the government (Tornatzky et al., 1990).

The TOE framework has been applied in various technology adoption research (Baker, 2012; Bhattacharya and Wamba, 2018). The TOE model has been adopted few studies in the past, such as e-commerce adoption (Rodríguez-Ardura and Meseguer-Artola, 2010), RFID adoption (Bhattacharya and Wamba, 2018), electronic data interchange (Iacovou et al., 1995; Kuan and Chau, 2001), and e-business adoption (Hussain et al., 2020; Molla et al., 2010; Ramdani et al., 2013; Zhu et al., 2003). Table 1 also summarizes the few studies that applied the TOE framework.

Bhattacharya and Wamba (2018) proposed a framework for RFID adoption. Under the TOE model, they observed the influence of 12 contextual factors under technology, environment, organization, and value chain on the RFID. They gathered their data from 74 experts from different businesses, and their results show that competitive pressure, relative advantage, and value chain positively impact RFID adoption.

Hussain et al. (2020) explained organizational and environmental factors in SMEs in their study and used a cross-sectional study survey method and DOI and RBV theories. The results, based on PLS-SEM, show a positive and significant effect between competitive pressure and management support on e-commerce usage.

The study by Chatterjee et al. (2021) used the TOE framework to explore the applicability of Industry 4.0 among Indian SMEs (n = 340) and their results showed a significant positive influence of environmental, technological, and social factors on the adoption of Industry 4.0 among SMEs in India. Dadhich and Hiran (2022) further explored the relationship between economic, social, technological, and organizational factors on the corporate environment sustainability of Indian SMEs (n = 390) and their results confirmed the important and significant relationship between these variables. Sayginer and Ercan (2020) used the TOE ModThel model to examine how external and internal factors influence the decision to adopt cloud computing in Turkey (n = 176) and showed the significant influence of top management support and the complexity of this type of decision. The study by Effendi et al. (2020) analyzed the behavioral intention to adopt social media in Indonesian SMEs (n = 250) affected by COVID-19 by using the TOE model. The results of this study showed that the technological context, organizational context, and environmental context, positively and significantly affect the intention to adopt social media.

Amini and Jahanbakhsh Javid (2023) applied the TOE model to determine the adoption of cloud computing in Malaysian SMEs (n = 22). The results showed that technology readiness, top management support, competitive pressure, and regulatory support were found to have positive and significant effects on the adoption of supply chain management in SMEs.

A study was conducted in Hong Kong by Kuan and Chau (2001), who applied a technological, organizational, and environmental framework and EDI adoption model. They collected data from 575 small firms and used logistic regression. The findings show that the technological, organizational, and environmental factor-related framework significantly affected technology adoption.

Zhu et al. (2003) developed a framework for electronic business adoption. They incorporated six adoption drivers relevant to a technological, organizational, and environmental framework. They collected data from 3100 organizations and 7500 customers from eight different European countries and applied EFA analysis to examine the reliability and validity of the constructs. Their results show that technological competency, form scope, the readiness of consumers, and the competitiveness pressure are the significant adoption facilitators.

Furthermore, the TOE framework has been employed in a large variety of research about technological innovation and technology adoption and usage studies such as the adoption of electronic data interchange (EDI), e-market adoption, web 2.0, and enterprise resource planning (ERP) are some examples (Saldanha and Krishnan, 2012; Ramdani et al., 2013).

Research framework and hypothesis

The current study focuses on technology factors’ relative advantage and compatibility toward adopting IR4.0. Furthermore, the organizational readiness and top management support as an organizational context. Comparably competitive pressure and governmental regulation as environmental factors toward adopting IR4. The current research, the adoption of IR4, was applied by examining two parts of the TOE model and the DOI theory to improve the efficiency of their system and, ultimately, to gain a competitive advantage over their competitors to gain a competitive edge over their competitors. Figure 4 summarizes our research framework and shows the suggested six predictors and underlying hypotheses with the IR4.0 adoption based on the literature.

Technology

Relative advantage can be defined as the degree to which technology acceptance enhances other kinds of technology currently being used in the organization. At the same time, the kind of opportunities and advantages technology offers the firm (Rogers, 2003). Organizations such as small and medium enterprises are keen to implement new developments or ways of manufacturing if they recognize that its benefits and improvement are better than the current technology (Ghobakhloo et al., 2011; Mittal et al., 2018). A study in Malaysia found a positive and significant relationship between the relative advantage of IR4.0 with its adoption (Ahmadi et al., 2017). Another study in China identified a positive relationship between the relative advantage of IR4.0 and its adoption (Yang et al., 2015). This discussion suggests the following hypothesis:

H1. The relative advantages of IR4.0 have a positive relationship with its adoption.

Rogers (2003) shows that compatibility is an influential determinant of technology adoption. This view is also supported by the technology task fit theory, which assumes that users will use the best technology for their intended use (Rai and Selnes, 2019; Röcker, 2010). This study proposes that the firm is willing to accept and execute changes if the company recognizes and understands that the IR4.0 implementation is compatible with existing processes and specifications. In Malaysia, Aziz and Wahid (2020) identified a positive and significant relationship between the compatibility of technology and the adoption of technology. The proposed hypothesis is as follows:

H2. There is a positive relationship between Compatibility and IR4.0 adoption.

Organizational

According to Boan and Funderburk (2003), an organization with solid norms and culture easily adapts to change. An organization and management’s ability to accept change and operate in a diverse environment keeps it relevant and competitive in the developed market. Organizational readiness makes it easy for companies to absorb and implement changes with less resistance (Bertoldi et al., 2018). Balakrishnan et al. (2021) explained in their study that organizational readiness positively and significantly affects IR4.0 adoption. This discussion ultimately suggests the following hypothesis:

H3. Organizational readiness positively influences IR4.0 adoption.

SMEs’ decision-makers usually come from the organization’s high-level management, and it is critical to seek their support throughout the transformation. Hussain et al. (2020) acknowledge that getting top management support will positively affect a new practice. Arnold et al. (2018) also recognize the importance of companies’ managerial role in considering the implementation of IR4.0 in the company. Because the execution of IR4.0 will come with extensive organizational changes and require substantial investments (Kagermann et al., 2013; Vuong and Mansori, 2021), top management’s support is critical to the success of IR4.0 adoption. A study in Malaysia examined top management support and IR4.0 adoption and showed a positive and significant impact on management support and adoption of IR4.0 technology (Ali and Johl, 2023). This input leads to the hypothesis below:

H4. Top management support is positively linked with IR4.0 adoption.

Environmental

Adopting modern technologies provides a competitive advantage for organizations to shift the traditional way of conducting business and dealing with competitors. Thus, this pressure of competition will increase the predisposition for technology adoption. Arnold et al. (2018) and Sima et al. (2020) acknowledge that intense competition motivates companies to be vigilant of competitors’ moves. A significant and positive relationship was found between competitive pressure and the adoption of IR4.0 (Yang et al., 2015). Hence the importance of technology adoption to avoid lagging leads to the following hypothesis:

H5: Competitive pressure positively influences IR4.0 adoption.

Studies have reported that the government’s support may be one factor that drives technology adoption and influences actual acceptance (Raj et al., 2020). Songling et al. (2018) stated that government regulations might be unpopular, which can encourage the organization to consider implementing new technology. Government regulation can comprehensively be one of the main drivers of innovation adoption. The study about government regulation and adopting new technology and found a positive relationship between government regulation and technology. Another study was conducted in India to analyze the relationship between government regulation and adopting IR4.0 technology. They saw government regulation’s positive and significant impact on IR4.0 adoption (Raj et al., 2020). This statement suggests the hypothesis below:

H6. Government regulation has positively influenced IR4.0 adoption.

Research methodology

Questionnaire design

We adopted our scales based on previous studies and modified them to the current research context, and used IR4.0 as the dependent variable and organizational readiness, top management support, relative advantage, compatibility, competitive pressure, and government regulation as independent variables. Table 2 presents the adapted survey items capturing the study variables.

We used the 14-item scale based on Ghobakhloo et al. (2011) and Raguseo and Vitari (2018) for measuring the dependent variable (IR4.0 adoption). For measuring the independent variables, we used a 6-item scale for the relative advantage based on Chen et al. (2015), Ghobakhloo et al. (2011) and Raguseo and Vitari (2018), and a three-item scale for compatibility from Ghobakhloo et al. (2011) and Raguseo and Vitari (2018). We further used a four-item scale to measure top management support from Chen et al. (2015) and Lai et al. (2018) and a four-item scale to measure organizational readiness from Chen et al. (2015). To measure competitive pressure, we used three items from Lai et al. (2018) and three items to measure government regulation from Agrawal (2015) and Lai et al. (2018).

We designed the questionnaires to answer the study’s objectives to cover a range of possible answers for different scenarios and use closed questions for the respondents. A closed-question format is more convenient and quickly answered due to limited potential answers. Besides, it is much more organized for data collection and analysis. In addition, the relationship between variables can be easily demonstrated (Bryman and Bell, 2007).

Data collection

For this study, we took a sample of 300 SMEs from all over Malaysia from a population of 1000 SMEs registered with Malaysian Industrial Development Industry (MIDF) Berhad. MIDF Berhad is one of the development financial institutions under the Ministry of International Trade and Industry (MITI) Malaysia. We distributed the questionnaires to Malaysian SMEs across three sectors: manufacturing, non-manufacturing, and others, and we used Google Forms to record the survey data. 123 questionnaires were returned, which resulted in a 41% percent response rate. One of the reasons for the low response rate could be the condition the SMEs were in during the COVID-19 pandemic when the study was conducted. SMEs’ focus was on ways to ensure their companies were in survival mode throughout the pandemic. With many surveys conducted by government agencies seeking feedback on intervention programs for government aid, initiatives requiring additional investment, such as technology adoption, are possibly a secondary option to SMEs.

To analyze the survey data, we used the Statistical Package for Social Sciences 25 (SPSS 25) and SMRT PLS 3.0 for the assessment of the measurement model (i.e., internal consistency or reliability, construct validity) and structural model (i.e., correlation, power of analysis).

Data analysis result

Demographics analysis

The demographic segregates based on position in the company, companies being in operation, and business sector. Of 123 respondents, less than 2/3 were from top management; the rest represented middle management (less than 1/3) and other levels (~3%). Respondents were mainly from the manufacturing industry, which recorded nearly 80%, while respondents from the non-manufacturing sector and others were around 20% each. Regarding the respondents’ company location, the largest state in Selangor with more than 1/3, followed by Kuala Lumpur with more than 20% and Penang with more than 12%. The least respondents come from the states of Perlis and Putrajaya and are below 1%.

The respondent firm age can be considered as high, where nearly 80% of the firms operate between 11 and more than 30 years. From the total of 123 respondents, more than 40% of companies employed 5–29 employees, followed by a range of 30–74 employees (more than 30%), over 200 employees (nearly 15%), 75–200 employees (almost 10%), and companies employed less than five employees (<3%). The survey also recorded that the average annual sales turnover of a company is divided into five categories which are RM3 million—less than RM15 million (nearly half of the sample), RM15 million—RM50 million (>18%), RM300,000—<RM3 million (more than 17%) and over RM50 million with nearly 10% and lastly <RM300,000 with almost 5%. More than 60% of respondents generally reported having a medium level of IR4.0 knowledge. In comparison, less than 1/3 claimed to have a high level of IR4.0 knowledge, nearly 10% had a low level of IR4.0 expertise, and <2% had no exposure to IR4.0.

Assessment of PLS-SEM path model results

We used confirmatory factors analysis (CFA) and multiple regression through the application of partial least square and structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) in the SmartPLS 3.0 software (Hair et al., 2014; Ringle et al., 2012). The two-step method for researching and documenting PLS-SEM findings was adopted, as Henseler et al. (2009) suggested.

Figure 5 illustrates the two-step method, which evaluates the measurement model as the first step and the structural model as the second step of analysis (Hair et al., 2014; Henseler et al., 2009). Once the data were screened, we applied PLS-SEM 3.0 to evaluate both the outer model (measurement model) and the inner model (structural model) (Hair et al., 2014), as the model is designed to be reflective before the analysis is completed (see Fig. 4). Our approach is significant because reflective model testing differs from the formative measurement model (Hair et al., 2014).

Internal consistency is measured by examining the C.R. value. Determining whether the construct’s proposed items produce similar scores (Hair et al., 2014) is essential. The C.R. value is between 0 and 1, with the expected value of not lower than 0.60 (Henseler et al., 2009). This study’s data illustrates that each construct’s C.R. values are above 0.6. The evaluation model requires that the measurement model begins with a reliability analysis of individual objects. The cross-loading of all construct items in the variables is analyzed to recognize any issues that serve as a prerequisite for the measurement model. It is intended to promote an understanding of the measuring model’s validity and reliability.

Hair et al. (2014) indicated that the average variance extracted (AVE) should exceed 0.50. This study’s data illustrates that each construct’s AVE values exceeded 0.50, with IR4.0 adoption at 0.902. The AVE for independent variables is as follows: relative advantage (0.890), compatibility (0.935), organizational readiness (0.896), top management support (0.879), competitive pressure (0.898), and government regulation (0.785) (see also Table 3). According to Fornell and Larcker (1981), calculating discriminant validity using AVE helps to check the models’ external consistency. Contrasting latent variables with AVE’s square root in a correlation can determine the discriminant validity. The value of discriminant validity, which is a square root of AVE, is suggested to be greater than indicated by the latent variables. The AVE will be within 0.50 or more of the score value (Fornell abd Larcker, 1981).

The discriminant validity matrix for IR4.0 adoption recorded a value of 0.946. As for the discriminant validity matrix for independent variables, the scores are indicated as follows: relative advantage (0.944), compatibility (0.967), organizational readiness (0.946), top management support (0.938), competitive pressure (0.948), and government regulation (0.886) (see Table 4). As shown in Table 4, the square roots of the AVE (bolded) are all higher than the off-diagonal correlation values, suggesting sufficient discriminant validity.

Assessment of structural model

The structural (inner) model is evaluated by using the direct relationship model for analysis. Structural equation analysis using PLS provides the value of the path coefficients and t-values in Fig. 6. If the t-value exceeds 1.64, it is considered significant and can be used for the proposed hypothesis.

Table 5 discusses the results of the present study. HI: relative advantage (β = 0.739, t = 9.734, p < 0.00) has a significant positive influence on the adoption of IR4.0 among Malaysian SMEs, and H2: compatibility (β = −0.181, t = 2.624, p < 0.004) has a positive impact on the adoption of IR4.0 among Malaysian SMEs. Also, H3: top management support (β = 0.269, t = 3.247, p < 0.001) has a positive influence on the adoption of IR4.0 among Malaysian SMEs, and H5: competitive pressure (β = 0.167, t = 1.870, p < 0.031) has a positive impact on the adoption of IR4.0 among Malaysian SMEs. H4: organizational readiness (β = −0.020, t = 0.366, p < 0.357) and H6: government regulation (β = 0.001, t = 0.016, p < 0.494) has no impact on the adoption of IR4.0 among Malaysian SMEs. The detailed result of hypotheses testing (direct effects) is shown in Table 5.

Figure 6 indicates the results generated using Smart PLS 3.0 and illustrates the p-value path, t-value, coefficient value, and standard errors. Four hypotheses were supported by the six hypotheses tested: H1, H2, H4, and H5. Meanwhile, two hypotheses, H3 and H6, were not supported (see also Table 5).

Discussion

This paper studies the factors influencing the adoption of IR4.0 among Malaysian SMEs. The research objectives investigate the technology factors, such as relative advantage and compatibility, the organizational factors, such as organizational readiness and top management, and the environmental factors, such as competitive pressure and government regulation on adopting IR4.0. The objectives were to know to which extent the technological, organizational, and environmental factors affect the adoption of IR4.0. The study aims to examine factors influencing the adoption of IR4.0 among SMEs in Malaysia and identify factors hindering successful adoption. Six independent variables were chosen to be tested to investigate their effect on the dependent variable. The independent variables were taken from the TOE framework, which covers the technological, organizational, and environmental as seen in Table 5. The variables have been examined using inner modeling analysis to understand better the factors that influence the IR4.0 adoption. The study shows a significant relationship between variables, except organizational readiness and government regulation.

The findings indicate that the relative advantages of IR4.0 have a positive relationship with companies’ adoption of the technology. The adoption of IR4.0 positively impacts the organization by making work more efficient, improving the value and worth of work, lowering the cost of doing business operations, attracting new market segments and customers, improving client service, and identifying and producing and producing innovative products or services. Companies with higher compatibility are more receptive to new technology. The SMEs that adopted IR4.0 stated that adopting IR4.0 in their organization is consistent with their current business practices and fits their organizational culture. Hence, it is easy to incorporate IR4.0 into the organization.

Another significant point is the importance of getting top management support for adoption. The boldness in providing resources necessary for IR4.0 adoption and conviction that the technology adoption is deemed as “strategically important” scored highest in this dimension. Top management support in promoting the use of IR4.0 in the organization, creating support for IR4.0 initiatives within the organization, promoting IR4.0 as a strategic priority, and showing interest in the news about using IR4.0 technology is the key that positively influences IR4.0 adoption.

SMEs in Malaysia would be affected by what their competitors are doing. The adoption of IR4.0 is directly linked to the pressure from competitors and the response to competitors’ actions. Competitive companies adopt new technology to be at par with their direct competitors or other competitors within the market—a fundamental move to strengthen their market position. This study indicates that organizational readiness is one of the main problems in implementing and adopting IR4.0. The findings reveal that companies with problems such as lack of capital or financial resources, information technology infrastructure and lack of analytics capability, and skilled resources are less likely to adopt IR4.0. These elements could cause a low confidence level in the vast potential of IR4.0. The study also highlighted that government policies might not encourage SMEs in Malaysia to adopt new information technology (e.g., IR4.0). Even though some companies agreed that the government had provided special lanes and incentives for adopting IR4.0 in government procurements or contracts, the factor is not strong enough to push them to adopt IR4.0. At the same time, the manufacturing SMEs also stated that the business regulations in dealing with the security matter and confidentiality of the IR4.0 technology are relatively low.

Conclusion

Based on the findings of our study, we can answer the research questions as follows. By using the TOE framework to see which factors define and measure the adoption of IR4.0 among Malaysian SMEs, the results of our study show that technological factors such as relative advantage and compatibility are essential elements that can significantly contribute to adoption success. This paper also highlights the importance of organizational readiness and top management support to adopt IR4.0.

Current research also indicates that top management support is a crucial driver for overcoming barriers and enhancing the organization’s ability to adopt modern technology successfully. The findings also highlight the importance of environmental factors in adopting IR4.0, particularly competitive pressure, and governmental regulation. Consequently, our results are significant for SME company owners, as our findings can help them to prepare themselves before embarking on technology adoption, in this case, IR4.0.

Finally, the study will benefit government agencies and related regulators to develop policies that support the proper intervention the technology adoption. Moving forward, they can create necessary programs and initiatives to encourage the adoption of IR4.0. The government can refine the ecosystem through the ministries and agencies by offering technical support, training, and funding either in a grant or soft financing form. They can also start revising and strengthening the business regulations in dealing with the security matter and confidentiality of the IR4.0 technology to encourage SMEs to venture into the new technology.

The results of our study provide theoretical contributions as well as practical implications. As such, our work contributes to the TOE framework, which has provided a structured thought process and good predictors to ensure the successful adoption of technology.

Based on general observations and literature reviews, an empirical indication of adopting IR4.0 within Malaysia’s context was lacking due to the technology’s novelty. Most of the focus was generally on the challenges of adopting IR4.0 in Malaysia (Tay et al., 2021), the opportunities and benefits of adoption, and the development of IR4.0 from the sectoral perspective (Jagan et al., 2018). Therefore this study shows the importance of technological, organizational, and environmental factors as critical predictors for adopting IR4.0 among Malaysian SMEs. With our work, we close this gap.

As for the development of financial institutions such as SME Bank, Malaysian Industrial Development Finance (MIDF), or Bank Pembangunan, the study might help the institutions develop initiatives and products that can cater to the issues faced by the SMEs. This will significantly impact the SME’s financial ecosystem, benefiting all parties.

From a company-level perspective that would like to explore and venture into the industrial revolution 4.0 hence staying ahead of the game, the findings indicate that allocation of resources is essential in financial, I.T. infrastructure, analytical capacity, and skilled talent development. The internal aspect of organizational readiness should be prioritized, and a strategic plan should ensure that the adoption process runs successfully. From the regulators’ point of view, the governmental policies might need to be strengthened to encourage SMEs in Malaysia to adopt new information technology. The right intervention programs and initiatives in promoting the adoption of IR4.0 are required. The government can refine the ecosystem by offering technical support, training, and funding through the ministries and agencies in a grant or soft financing form. The regulators also need to strengthen the business regulations in dealing with the security matter and confidentiality of the IR4.0 technology to attract SMEs to venture into the new technology adoption. Through active engagement with top management, the Buy-in process must ensure that IR4.0 knowledge, its benefits, and the country’s aspirations toward a developed nation are communicated well to the organization.

The second level is SMEs that are implementing and developing it. The last level is in the advanced stage and who are the leading in the market. By knowing the challenges, SMEs in the 1st stage will benefit by preparing and preparing the necessary according to the requirements and possibilities. SMEs in the second level can also improve and be ready to face any opportunity to impact the organization. The advanced SMEs can benefit by turning the other SMEs’ challenges into collaborating and mentoring the related SMEs. The study aims to deal with the fundamentals of technology adoption and unveil which factor is most prominent in adopting IR4.0 among Malaysian SMEs. The elements used to investigate the adoption level of IR4.0 will refer to the three categories: the technology, organization, and environment—within the TOE Framework. This study uses the DOI and TOE framework to understand further IR4.0 adoption and factors affecting its successful implementation, especially among SMEs in Malaysia.

One limitation refers to the sample population of 1000 SMEs in Peninsular Malaysia. This differs in terms of exposure to the IR4.0 concept from the SME population, which covers 98.5% of the total business establishments in Malaysia, including Sabah and Sarawak. The second limitation is that the samples cut across all sectors and do not focus on the manufacturing industry, where the IR4.0 technology is most applicable. Thirdly, due to the less exposure to new technology. Last but not least, the study occurred during the global outbreak of the deadly infectious disease COVID-19. The movement control order (MCO) announced by the government has indirectly impacted the survey regarding data collection. There were some restrictions and limitations in conducting the extensive survey. As far as the economy is concerned, SMEs were badly impacted by the current situation. Hence their focus was more on business survival as they struggled to handle distribution and retaining employees. Since the business sentiment was negative at the point this study took place and the nature of this study is “additional investment”, the response to the survey was lower than expected.

The study will also be better if it is across SMEs in all states in Malaysia, including Sabah and Sarawak, to make a more holistic view of the adoption IR4.0 scenario in Malaysia. The findings from this study can act as a basis for identifying factors influencing IR4.0 adoption. For precision in future studies, the focus should be on companies from the manufacturing sector and their related services, as pointed out in the National Policy on Industry 4.0 (Industry4WRD). In terms of precision, it would also be more effective to cover companies with the same level of exposure and knowledge for IR4.0 for better comparison.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Abod SG (2016) Industry 4.0: are Malaysian SMEs ready. BizPulse 17:1–3

Agrawal K (2015) Investigating the determinants of big data analytics (BDA) adoption in Asian emerging economies. In: Proceedings of the 21st information systems. pp 13–15. https://journals.aom.org/doi/10.5465/ambpp.2015.11290abstract

Ahmadi H, Nilashi M, Shahmoradi L, Ibrahim O (2017) Hospital information system adoption: expert perspectives on an adoption framework for Malaysian public hospitals. Comput Hum Behav https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.10.023

Alcácer V, Cruz-Machado V (2019) Scanning the Industry 4.0: a literature review on technologies for manufacturing systems. Eng Sci Technol 22(3):899–919. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jestch.2019.01.006

Ali K, Johl SK (2023) Impact of total quality management on industry 4.0 readiness and practices: does firm size matter? Int J Comput Integr Manuf 36(4):567–589

Amini M, Jahanbakhsh Javid N (2023) A multi-perspective framework established on diffusion of innovation (DOI) theory and technology, organization and environment (TOE) framework toward supply chain management system based on cloud computing technology for small and medium enterprises. Int J Inf Technol Innov Adopt 11:1217–1234

Arnold C, Veile J, Voigt KI (2018) What drives industry 4.0 adoption? An examination of technological, organizational, and environmental determinants. In: Proceedings of 27th Annual Conference of the International Association for Management of Technology, Birmingham, United Kingdom, pp 22–26

Aziz ASA, Wahid NA (2020) Do new technology characteristics influence intention to adopt for manufacturing companies in Malaysia? In: First ASEAN Business, Environment, and Technology Symposium (ABEATS 2019). Atlantis Press, pp 30–35

Bahrin MAK, Othman MF, Azli NH, Talib MF (2016) Industry 4.0: A review on industrial automation and robotic. J Teknol 78:137–143. https://doi.org/10.11113/jt.v78.9285

Baker J (2012) The technology–organization–environment framework. Information Systems Theory: Explaining and Predicting Our Digital Society 1:231–245

Balakrishnan B, Othman Z, Zaidi MFA (2021) The impact of IR4.0 readiness on IR4.0 adoption among Malaysian e&e SMEs. Int J Technol Manag Inf Syst 3(1):1–11

Balasingham K (2016) Industry 4.0: securing the future for German manufacturing companies, M.S. thesis, University of Twente, Enschede

Barham H, Dabic M, Daim T, Shifrer D (2020) The role of management support for the implementation of open innovation practices in firms. Technol Soc 63:101282. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2020.101282

Bertoldi B, Giachino C, Rossotto C, Bitbol-Saba N (2018) The role of a knowledge leader in a changing organizational environment. A conceptual framework drawn by an analysis of four large companies. J Knowl Manag 22(3):587–602. https://doi.org/10.1108/JKM-09-2017-0422

Bhattacharya M, Wamba SF (2018) A conceptual framework of RFID adoption in retail using TOE framework. In: Technology adoption and social issues: Concepts, methodologies, tools, and applications. IGI Global, pp. 69–102 https://www.igi-global.com/chapter/a-conceptual-framework-of-rfid-adoption-in-retail-using-toe-framework/196673

Boan D, Funderburk F (2003) Healthcare quality improvement and organizational culture: insights. Delmarva Foundation

Bødker K, Bøving KB (2003) Implementation of groupware technology in a large organization: lessons learned. In: Proceedings of the Third Danish Human-Computer Interaction Research Symposium: Roskilde, Denmark 27th November, 2003. Roskilde Universitet, pp. 21–24

Bryman A, Bell E (2007) Business research methods, 2nd edn. Oxford University Press, Oxford, USA

Chatterjee S, Rana NP, Dwivedi YK, Baabdullah AM (2021) Understanding AI adoption in manufacturing and production firms using an integrated TAM-TOE model. Technol Forecast Soc Change 170:120880

Chen D, Heyer S, Ibbotson S, Salonitis K, Steingrímsson JG, Thiede S, (2015) Direct digital manufacturing: definition, evolution, and sustainability implications, J Clean Prod (in the press), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2015.05.009

Dadhich M, Hiran KK (2022) Empirical investigation of extended TOE model on Corporate Environment Sustainability and dimensions of operating performance of SMEs: a high order PLS-ANN approach. J Clean Prod 363:132309

Dalenogare LS, Benitez GB, Ayala NF, Frank AG (2018) The expected contribution of Industry 4.0 technologies for industrial performance. Int J Prod Econ 204:383–394. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpe.2018.08.019

Deakins D, Galloway L, Mochrie R (2003) The Use and Effect of ICT on Scotland’s Rural Business Community Research Report for Scottish Economist Network. Scottish Economist Network, Stirling

DSM (2020) Department of Statistics of Malaysia. https://www.dosm.gov.my. Accessed 6 Dec 2020

Duncombe R, Heeks R (2003) An information systems perspective on ethical trade and self-regulation. Inf Technol Dev 10(2):123–138. https://doi.org/10.1002/itdj.1590100206

Effendi MI, Sugandini D, Istanto Y (2020) Social media adoption in SMEs impacted by COVID-19: The TOE model. J Asian Finance Econ Bus 7(11):915–925

EMP (2018) Eleventh Malaysia Plan mid-term review of the 2016. Retrieved: 18 Oct 2018. https://www.ekonomi.gov.my/en/economic-developments/development-plans/rmk/mid-term-review-eleventh-malaysia-plan-2016-2020

Fornell C, Larcker DF (1981) Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: algebra and statistics. J Mark Res 18(3):382–388. https://doi.org/10.2307/3150980

Furuholt B, Orvik TU (2006) Implementation of information technology in Africa: understanding and explaining the results of ten years of implementation effort in a Tanzanian organization. Inf Technol Dev 12(1):45–62. https://doi.org/10.1002/itdj.20030

Ghadge A, Kara ME, Moradlou H, Goswami M (2020) The impact of Industry 4.0 implementation on supply chains. J Manuf Technol Manag https://doi.org/10.1108/JMTM-10-2019-0368

Ghobakhloo M, Arias‐Aranda D, Benitez‐Amado J (2011) Adoption of e‐commerce applications in SMEs. Ind Manag Data Syst 111(8):1238–1269. https://doi.org/10.1108/02635571111170785

Gibbs S, Sequeira J, White MM (2007) Social networks and technology adoption in small business. Int J Glob Small Bus 2(1):66–87. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJGSB.2007.014188

Gilchrist A (2016) Introducing Industry 4.0. In: Industry 4.0. Apress, Berkeley, CA. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4842-2047-4_13

Haddad A, Ameen AA, Mukred M (2018) The impact of intention of use on the success of big data adoption via organization readiness factor. Int J Manag Hum Sci 2(1):43–51

Hair JF, Hult GTM, Ringle CM, Sarstedt M (2014) A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). Sage Publication, Thousand Oaks, CA

Hamim H, Kadir MNA, Shariff MNM (2021) SMEs Retailing in Malaysia: Challenges for Industrial Revolution 4.0 Implementation. In: Sergi BS, Jaaffar AR (ed) Modeling Economic Growth in Contemporary Malaysia. Emerald Publishing Limited, pp. 1–15

Hawkins R, Prencipe A (2000) Business-to-business e-commerce in the U.K.: a synthesis of sector reports commissioned by the Department of Trade and Industry

Henseler J, Ringle CM, Sinkovics RR (2009) The use of partial least squares path modeling in international marketing. Adv Int Mark 20(1):277–319. https://doi.org/10.1108/S1474-7979(2009)0000020014

Hussain A, Shahzad A, Hassan R (2020) Organizational and environmental factors with the mediating role of e-commerce and SME performance. J Open Innov: Technol Mark Complex 6(4):196. https://doi.org/10.3390/joitmc6040196

Hussein LA, Baharudin AS, Jayaraman K, Kiumarsi SHAIAN (2019) B2B e-commerce technology factors with mediating effect perceived usefulness in Jordanian manufacturing SMES. J Eng Sci Technol 14(1):411–429. https://doi.org/10.48084/etasr.3373

Iacovou CL, Benbasat I, Dexter AS (1995) Electronic data interchange and small organizations: adoption and impact of technology. MIS Q 19(4):465–485. https://doi.org/10.2307/249629

Jagan J, Othman MR, Saharuddin AH, Park GK, Do TMH (2018) An evolution of a nexus between Malaysian Seaport Centric Logistic and Industrial Revolution 4.0: current status and future strategies. Int J e-Navig Marit Econ 10:1–15

Kagermann H, Wahlster W, Helbig J (2013) Recommendations for implementing the strategic initiative Industrie 4.0—Final report of the Industrie 4.0 Working Group. Communication Promoters Group of the Industry–Science Research Alliance, acatech, Frankfurt am Main

Kleindienst M, Ramsauer C (2016) SMEs and Industry 4.0-introducing a KPI based procedure model to identify focus areas in manufacturing industry. Athens J Bus Econ 2(2):109–122. https://doi.org/10.30958/ajbe.2-2-1

Kuan KK, Chau PY (2001) A perception-based model for EDI adoption in small businesses using a technology–organization–environment framework. Inf Manag 38(8):507–521. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-7206(01)00073-8

Lai Y, Sun H, Ren J (2018) Understanding the determinants of big data analytics (BDA) adoption in logistics and supply chain management: an empirical investigation. Int J Logist Manag 29(2):676–703. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJLM-06-2017-0153

Lin CS (2006) Organizational, technological, and environmental determinants of electronic commerce adoption in small and medium enterprises in Taiwan. Doctoral dissertation, Lynn University

Ling YM, Hamid NAA, Te Chuan L (2020) Is Malaysia ready for Industry 4.0? Issues and challenges in manufacturing industry. Int J Integr Eng 12(7):134–150. https://doi.org/10.30880/ijie.2020.12.07.016

Luong NAM, Wang L (2019) Factors influencing e-commerce usage within internationalisation: a study of Swedish small and medium-sized fashion retailers. M.S. thesis, Uppsala Universitet, Sweden

Manda MI, Ben Dhaou S (2019) Responding to the challenges and opportunities in the 4th Industrial revolution in developing countries. In: Proceedings of the 12th international conference on theory and practice of electronic governance, pp. 244–253. https://dl.acm.org/doi/abs/10.1145/3326365.3326398

MITI (2018) Industry 4WRD: National Policy on Industry 4.0. Industry4WRD_Final.pdf. miti.gov.my. Accessed 31 Oct 2018

MITI (2019) Ministry of International Trade and Industry. https://www.miti.gov.my/miti/resources/MITI%20Report/MITI_REPORT_2019.pdf. Accessed 1 Aug 2020

Mittal S, Khan MA, Romero D, Wuest T (2018) A critical review of smart manufacturing & Industry 4.0 maturity models: implications for small and medium sized enterprises (SMEs). J Manuf Syst 49:194–214. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmsy.2018.10.005

Mohtaramzadeh M, Ramayah T, Jun-Hwa C (2018) B2B E-commerce adoption in Iranian manufacturing companies: analyzing the moderating role of organizational culture. Int J Hum–Comput Interact 34(7):621–639. https://doi.org/10.1080/10447318.2017.1385212

Molla A, Peszynski K, Pittayachawan S (2010) The use of e-business in agribusiness: investigating the influence of e-readiness and OTE factors. J Global Inf Technol Manag 13(1):56–78. https://doi.org/10.1080/1097198X.2010.10856509

Montreuil B (2011) Toward a Physical Internet: meeting the global logistics sustainability grand challenge. Logist Res 3(2):71–87. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12159-011-0045-x

Nagayya D, Rao TP (2013) Small and medium enterprises in the era of globalization. J Rural Dev 32(1):1–17

Nagy J, Olah J, Erdei E, Mate D, Popp J (2018) The role and impact of Industry 4.0 and the Internet of Things on the business strategy of the value chain-the case of Hungary. Sustainability 10:3491. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10103491

Narula R (2004) R&D collaboration by SMEs: new opportunities and limitations in the face of globalization. Technovation 24(2):153–161. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0166-4972(02)00045-7

Nimfa HMDT, Maimako LN, Idris IR (2020) Effect of digital manufacturing and consumer behaviour on firm sustainability in Malaysia. Curr Issues Entrep Bus 70–96

Oliveira T, Martins MF (2011) Literature review of information technology adoption models at firm level. Electron J Inf Syst Eval 14(1):110–121

Pech M, Vrchota J (2020) Classification of small-and medium-sized enterprises based on the level of industry 4.0 implementation. Appl Sci 10(15):5150. https://doi.org/10.3390/app10155150

Raguseo E, Vitari C (2018) Investments in big data analytics and firm performance: an empirical investigation of direct and mediating effects. Int J Prod Res 56(15):5206–5221. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207543.2018.1427900

Rai RS, Selnes F (2019) Conceptualizing task-technology fit and the effect on adoption. A case study of a digital textbook service. Inf Manag 56(8):103161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2019.04.004

Raj A, Dwivedi G, Sharma A, de Sousa Jabbour ABL, Rajak S (2020) Barriers to the adoption of industry 4.0 technologies in the manufacturing sector: an inter country comparative perspective. Int J Prod Econ 224:107546. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpe.2019.107546

Ramdani B, Chevers D, Williams DA (2013) SMEs’ adoption of enterprise applications: a technology–organisation–environment model. Jf Small Bus Enterprise Dev 20(4):735–753. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSBED-12-2011-0035

Ringle CM, Sarstedt M, Straub DW (2012) Editor’s comments: a critical look at the use of PLS SEM. MIS Q 36(1):iii–xiv. https://doi.org/10.2307/41410402

Röcker Cc (2010) Why traditional technology acceptance models won’t work for future information technologies? vol. 41. World Academy of Science, Engineering and Technology, pp.199–205

Rodríguez-Ardura I, Meseguer-Artola A (2010) Toward a longitudinal model of e-commerce: environmental, technological, and organizational drivers of B2C adoption. Inf Soc 26(3):209–227. https://doi.org/10.1080/01972241003712264

Rogers EM (2003) Diffusion of innovations. Free Press, New York, NY

Saldanha TJV, Krishnan MS (2012) Organizational adoption of web 2.0 technologies: an empirical analysis. J Organ Comput Electron Commer 22:301–333. https://doi.org/10.1080/10919392.2012.723585#preview

Samsudin NA, Alias Z, Khan NU, Bazkiaei HA (2021) Pathways towards sustainable business model for Malaysian microenterprises. Acad Strateg Manag J 20:1–9

Sayginer C, Ercan T (2020) Understanding determinants of cloud computing adoption using an integrated diffusion of innovation (doi)-technological, organizational and environmental (toe) model. Humanit Soc Sci Rev 8(1):91–102

Schwab K (2016) The fourth industrial revolution. World Economic Forum, Geneva

Senarathna I, Wilkin C, Warren M, Yeoh W, Salzman S (2018) Factors that influence adoption of cloud computing: an empirical study of Australian SMEs. Australas J Inf Syst 22. https://doi.org/10.3127/ajis.v22i0.1603

Sima V, Gheorghe IG, Subić J, Nancu D (2020) Influences of the Industry 4.0 revolution on the human capital development and consumer behavior: a systematic review. Sustainability 12(10):4035. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12104035

SME Corporation Malaysia (2022a) SME definitions, https://www.smecorp.gov.my/index.php/en/policies/2020-02-11-08-01-24/sme-definition

SME Corporation Malaysia (2022b) MSME statistics, https://www.smecorp.gov.my/index.php/en/policies/2020-02-11-08-01-24/sme-statistics

Songling Y, Ishtiaq M, Anwar M, Ahmed H (2018) The role of government support in sustainable competitive position and firm performance. Sustainability 10(10):3495. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10103495

Tay SI, Alipal J, Lee TC (2021) Industry 4.0: Current practice and challenges in Malaysian manufacturing firms. Technol Soc 67:101749. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2021.101749

Tornatzky LG, Fleischer M, Chakrabarti AK (1990) Processes of technological innovation. Lexington Books

United Nation Industrial Development Organization (2016) Industry 4.0: opportunities and challenges of the new industrial revolution for developing countries and economies in transition. United Nation Industrial Development Organization

Vuong TK, Mansori S (2021) An analysis of the effects of the fourth industrial revolution on Vietnamese enterprises. Manag Dyn Knowl Econ 9(4):447–459. https://doi.org/10.2478/mdke-2021-0030

Yang Z, Sun J, Zhang Y, Wang Y (2015) Understanding SaaS adoption from the perspective of organizational users: a tripod readiness model. Comput Hum Behav 45:254–264. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.12.022

Yu F, Schweisfurth T (2020) Industry 4.0 technology implementation in SMEs—a survey in the Danish–German border region. Int J Innov Stud 4(3):76–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijis.2020.05.001

Zhou K, Liu T, Zhou L (2015) Industry 4.0: Towards future industrial opportunities and challenges. In: 2015 12th International conference on fuzzy systems and knowledge discovery (FSKD). IEEE, pp. 2147–2152

Zhu K, Kraemer KL (2005) Post-adoption variations in usage and value of e-business by organizations: cross-country evidence from the retail industry. Inf Syst Res 16(1):61–84. https://doi.org/10.1287/isre.1050.0045

Zhu K, Kraemer K, Xu S (2003) Electronic business adoption by European firms: a cross-country assessment of the facilitators and inhibitors. Eur J Inf Syst 12(4):251–268. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.ejis.3000475

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AS: conceptualization, data analysis, and interpretation, MsAbZ: methodology— data collection-interpretation, HK: conceptualization, writing—review and editing, supervision project administration, MAMM: resources and investigation, AH: literature writing and JF: writing—review and editing, project administration.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors

Informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shahzad, A., bin Zakaria, M.S.A., Kotzab, H. et al. Adoption of fourth industrial revolution 4.0 among Malaysian small and medium enterprises (SMEs). Humanit Soc Sci Commun 10, 693 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-02076-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-02076-0

- Springer Nature Limited