Abstract

Field of study decisions are important for children’s future life chances, as significant differences exist in terms of financial and status benefits across fields of study. We examine whether the economic or the cultural status of the parents is more influential in shaping their children’s expectations about their future field of study. We also test whether children’s expectations about field of study choices are mediated by the child-rearing values that parents hold. Results show that parental economic status increased the likelihood of adolescents expecting to opt for extrinsic rewarding fields of study. Adolescent girls, not boys, with high cultural status parents were more likely to expect to opt for intrinsically rewarding fields of study. An upbringing that is characterized by conformity increased the expectations of boys to choose an extrinsically rewarding study, while self-direction increased the expectations of girls to opt for an extrinsic field of study

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

A key question in studies on occupational choices of young adults is to what extent and in what ways their socio-economic background influences their future life chances (Wicht and Ludwig-Mayerhofer, 2014; Howell et al., 1984; Blau and Duncan, 1967). As educational attainment is usually viewed as a prerequisite for occupational success, much research has focused on how parental socio-economic status (SES) influences educational attainment processes (Parsons and Halsey, 2014; Sewell, Haller and Portes, 1969). In these studies, attention has mostly focused on the influence of parental SES on the level of education that their children attain (Bornstein and Bradley, 2014; Fehrmann et al., 1987). However, partially in response to a general increase in the level of education, recent research pays increasing attention to how parental SES influences the field-of-study choices of children (Goyette, 2008; Goyette and Mullen, 2006; Van de Werfhorst and Luijkx, 2010). Field-of-study decisions are important for children’s future life chances, as significant differences exist in terms of financial and status benefits across fields of study. It is often assumed that children of parents who have a relatively low SES are more likely to view their field-of-study choices as ‘instrumental’ (Davies and Guppy, 1997), implying that the most important goal of studying is to gain extrinsic rewards, i.e., a well-paid job. In contrast, children of parents with a relatively high SES are assumed to place more value on intrinsic aspects of fields of study, such as their potential for self-development (Johnson et al., 2007; Johnson and Mortimer, 2011).

Given our limited knowledge of the influence of parental SES on adolescent field-of-study choices, this article will address three related research questions: (1) to what extent does parental SES influence the future field-of-study expectations of adolescents, (2) which aspect of parental SES (economic or cultural status) is more important in this respect, and (3) to what extent is this influence mediated by parents’ child-rearing values? In answering these questions, we want to contribute to the existing literature in four ways.

First, we focus on adolescents’ expectations about their future field of study rather than on their actual choices. We have two reasons for this. Adolescents’ expectations are found to be a good indicator of their subsequent actual life decisions (Rimkute et al., 2012). More important, though, is that young adults’ actual choices often are a mix of expectations and aspirations on the one hand and available opportunities on the other. Parental SES can influence these choices either through its influence on their children’s expectations and aspirations or through its influence on the opportunities that their children face. By studying the expectations of adolescents, we can ascertain to what extent parents influence the expectations of their children, irrespective of the ‘opportunity structure’ they face.

Second, we classify the different fields of study by the type of reward (extrinsic versus intrinsic), which is thought to be key to opting for specific types of study. Thus, the emphasis of humanities and social studies is on intrinsic rewards, with characteristics as furthering knowledge and interest (Bonvillian and Murphy, 2014). In these fields of study, studying in itself is often viewed as the goal and it is not directly related to future employment. This is in contrast to studies like business economics and technical/engineering studies, in which a specific set of skills and knowledge are taught that will make graduates more attractive on the labor market (Kerr, 1991), and offer much clearer future employment and salary expectations. These fields of study are therefore often mainly characterized as extrinsically rewarding.

Third, we examine whether the economic or the cultural status of the parents is more influential in shaping their children’s expectations about their future field of study (Bourdieu, 1986). Adolescents from a high economic status background might be particularly likely to opt for studies that are extrinsically rewarding, while adolescents from a high cultural status background might be more likely to opt for studies that are intrinsically rewarding.

Fourth, we test whether the influence of parental SES on children’s expectations about field-of-study choices is mediated by the parents’ child-rearing values and parenting styles. Many studies have shown that child-rearing values and parenting styles are SES-dependent (Baumrind, 1971; Kohn, 1963; Lareau, 2011). In addition, these styles in themselves may have consequences for the expectations that children develop concerning their field of study. In particular, we expect that a parenting style that focuses on conformity favors opting for extrinsically rewarding fields of study, whereas a parenting style that focuses on self-direction favors opting for intrinsically rewarding fields of study.

The research questions will be answered using data on more than 1500 Dutch adolescents aged 14–17, who completed a survey about their future plans, expectations and ambitions. In addition, one of the pupil’s parents was also asked about his or hers expectations and ambitions for this child. Furthermore, we used experts’ opinions to classify the extent to which specific fields of study could be classified as either extrinsically or intrinsically rewarding.

Theory and hypotheses

SES and field of study

In a highly individualistic society, it is sometimes assumed that fields-of-study choices are based primarily on preferences and abilities of the adolescents themselves (Beck, 2002; Giddens, 2013), rather than determined by parental background. Yet, empirical research has shown that strong similarities exist between the field of study of fathers and of their children (Van de Werfhorst et al., 2001). Van de Werfhorst and Luijkx (2010) also found an association between the father’s employment field and the study choice of his children.

One explanation for this link between SES and field of study is Lucas’ (2001) idea of ‘Effectively Maintained Inequality’ (EMI). EMI suggests that parents with higher SES try to secure ‘benefits’ for their children through the educational system. These ‘benefits’ can take two forms: quantitative (e.g., level of education) and qualitative (e.g., curriculum choices). As more and more young people continue to tertiary education, the ‘benefits’ effect from the level of education has become less important, so it has become more important to get the ‘benefit’ out of the chosen study. Assuming that good employment prospects are seen as a ‘benefit’, one can infer that parents with a high SES are more likely to direct their children to fields of study with better employment prospects (Ma, 2009), and thus stimulate them to opt for extrinsically rewarding fields of study.

An alternative argument leading to quite opposite expectations is provided by Breen and Goldthorpe’s (1997) ‘Relative Risk Aversion’ theory (RRA). RRA states that parents prefer their children’s future social status to be just as good as or better than their own, and that it is important to counter downward social mobility. RRA was initially used to explain status attainment, but it could also explain field-of-study choices. Assuming that parents with a low SES exhibit strong risk aversion behavior, it is expected that low SES parents will stimulate their children to choose fields of study with good employment prospects. Research into adolescents’ attitudes towards work shows that adolescents who have parents with a high SES better appreciate the intrinsic aspects of a job, such as self-fulfillment, than adolescents from low SES origins (Kohn and Schooler, 1969), while the latter are more appreciative of the extrinsic aspects of a job, such as a good salary and job security.

Empirical research seems to support RRA rather than EMI. Kelsall et al. (1972) concluded that adolescents from low socio-economic origins opt for studies with good employment prospects. Davies and Guppy (1997) also concluded that the field-of-study choice of ‘working-class students’ is more often seen as ‘instrumental’ and that these students are more inclined to choose technical or business economic studies. Technical studies often strongly appeal to the experience of lower-class fathers: think, for example, of fathers with physically demanding (un)skilled labor (Kelsall et al., 1972). Intellectual and esthetic skills are often less important to this group of students.

What both RRA and EMI have in common, is that they start from a one-dimensional interpretation of parental SES. In contrast, Bourdieu (1986) distinguishes between a cultural and an economic status dimension. He viewed society as hierarchically divided into economic and cultural status positions, each with its own norms, values and customs. The economic elite (managers, lawyers and CEOs) is distinguished by a focus on luxury and possessions, while the cultural elite is distinguished by emphasizing ‘good taste’ in art and literature. By internalizing parental norms and values, adolescents whose parents have a strong economic status might be particularly likely to opt for law and economics, because these studies lead to economic status and esteem, while adolescents with a strong cultural background might be more likely to opt for social and cultural studies because of the cultural status and appreciation of these studies.

Several hypotheses may be formulated on the basis of this literature. First, two competing hypotheses can be formulated about the effect of the economic status of the parents on the field-of-study choice of their children. The ideas of both Lucas and Bourdieu seem to suggest that, as parents have higher economic status, their children will be increasingly likely to opt for more extrinsically rewarding fields of study, while on the basis of the ‘Relative Risk Aversion’ theory one would expect that low SES background children would show a stronger preference for extrinsically rewarding fields of study. Therefore, we formulate two competing hypotheses:

H1a: The higher parents’ economic status, the stronger their children expect to opt for extrinsically rewarding fields of study.

H1b: The lower parents’ economic status, the stronger their children expect to opt for extrinsically rewarding fields of study.

In addition, Bourdieu’s ideas about cultural status suggest a hypothesis on the relationship between parental cultural status and their children’s expectations about future fields of study:

H2: The higher parents’ cultural status, the stronger their children expect to opt for intrinsically rewarding fields of study.

The mediating role of parental values and styles

At least three different strands of literature suggest that, in understanding the relationship between parents’ SES and their children’s expected field of study, child-rearing values and styles may play a key role. In his classic study, Class and Conformity, Kohn and Schooler (1969) argued that parents (fathers) transmit values that are appreciated in the workplace to their children. Middle-class parents often have jobs where intellectual stimulation and independent decision-making are important. These parents internalize ‘self-direction’ in their behavior, and this orientation, both intentionally and unintentionally, is transferred to their children. Lower-class parents, on the other hand, experience that conformity to rules and requirements is valued, and thus ‘conformity’ is internalized and passed on to their children.

Whereas Kohn stressed the importance of parental values, Baumrind (1971) stressed the importance of parenting styles. Her typology distinguishes between authoritative (supportive), authoritarian, and permissive (laissez-faire) parenting styles, each a blend of warmth, control and independence. The emphasis is usually on the difference between the first two (most common) styles. The authoritative parenting style advocates warmth and engagement, reasoning and the promotion of independence. Children from parents who practice authoritative parenting are generally happier, can cooperate better and have more confidence (Berk, 2000). Parents who use an authoritarian parenting style score low on warmth and engagement, high on a stringent, authoritarian control style and low on the promotion of the child’s independence. As authoritarian parents often make decisions for the child and do not explain the reasons for rules, their children are often uncertain and less independent (Nix et al., 1999).

Lareau (2011) suggested a similar link between socialization and SES. She suggests that “concerted cultivation” is the most common type of parenting among middle-class parents in the USA. These parents teach their children things that are not taught in school and stimulate critical thinking and participation in many out-of-school activities. An important advantage of this form of parenting is that children learn how to get along with adults and each other through organized activities. In addition, the child develops a ‘sense of entitlement’: his or her opinion counts and is taken into consideration. This is in contrast to socialization by poor and lower-class parents, which is often more directive. These parents are often less involved with after-school activities. Due to their lower level of education and lack of time, they are less able to support their children. Children participate less in organized activities and spend more of their free time with other children in the neighborhood. The children and parents often allow themselves to be led by the choices that institutions, such as the school, present to them. In addition, children learn how to get along with each other on the street, without the supervision of parents. The desired attitude with respect to adults and parents is that of obedience. Lareau terms this type of socialization “the accomplishment of natural growth”.

What these three strands of literature have in common is that they hypothesize a relationship between parental social class and the ways in which parents raise their children. Middle- and higher-class parents are thought to promote a cultural climate of ‘concerted cultivation’, exert a more authoritative parenting style, and encourage self-direction. In contrast, lower-class parents are thought to promote a climate of ‘accomplishment of natural growth’, exert an authoritarian parenting style, and encourage an obedient and conformist attitude towards authorities and adults.

Empirical studies confirm the relationship between Baumrind’s authoritarian parenting style and low SES (Bluestone and Tamis-LeMonda, 1999; Conger et al., 1994). McLoyd (1990) summarized the relationship by stating that poverty and economic disadvantage negatively affects parents’ ability to be supportive, consistent and engaged. As a consequence of economic stress, these parents often demand obedience and discipline while providing less explanation for their actions (McLoyd, 1990). The authoritative parenting style seems to generate more positive outcomes. Empirical research shows that these adolescents perform better in school (Dornbusch et al., 1987; Weiss and Schwarz, 1996), are more involved in school (activities) (Steinberg et al., 1992) and have a positive attitude toward school (Maccoby and Martin, 1983; Steinberg et al., 1992). These results are often attributed to encouraging independent problem-solving and learning to think critically, as opposed to the authoritarian parenting style, which may lead to passivity (Steinberg et al., 1992) and a lack of interest in school (Pulkkinen, 1982). The same was found for Lareau’s ideas about the link between SES and socialization. A socialization characterized as ‘concerted cultivation’ leads to better school performance and more involvement in school than an upbringing characterized by ‘accomplishment of natural growth’ (Bodovski and Farkas, 2008; Redford et al., 2009).

Remarkably, hardly any research has directly linked parenting values and styles to field-of-study choices. However, studies on adolescents’ motivation could offer insights into this link. Leung and Kwan (1998) found that authoritative parenting style was linked to the development of an intrinsic motivation among children, whereas an authoritarian parenting style was linked to the development of extrinsic motivation among children. It is therefore likely that authoritative parenting stimulates adolescents to develop a preference for more intrinsically rewarding fields of study, whereas authoritarian parenting stimulates the development of a preference for more extrinsically rewarding fields of study.

On the basis of these considerations three additional hypotheses are formulated:

H3: The more parents employ a conformity-oriented parenting style, the stronger their children expect to opt for extrinsically rewarding fields of study.

H4: The more parents employ a self-direction-oriented parenting style, the stronger their children expect to opt for intrinsically rewarding fields of study.

H5: The effects of parental economic and cultural status on their children’s expected field of study are mediated by parental values.

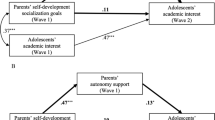

This final hypothesis concerns the indirect relationship between parents’ economic and cultural status and their children’s expected field-of study choice. A higher SES is expected to be related to a more self-direction-oriented parenting style, which in turn leads to more intrinsically rewarding expected study choices. Figure 1 summarizes the expected relationships between parental SES, parenting styles and children’s expectations about future field of study.

Thus far, we have refrained from explicitly discussing gender, because we expect that the same basic processes apply to boys and girls. At the same time, different expectations may exist with regard to the field-of-study choices of boys and girls. In particular, parents stressing conformity may hold different field-of-study expectations for sons and daughters, as both genders are expected to conform to traditional ‘gendered’ ideas about future occupational involvement. Therefore, we will perform separate analyses for boys and girls.

Methods

Sample

Data were collected in 2005 (Ganzeboom et al., 2005–2006) as part of the project ‘Youth and Culture’. Data collection took place among students in secondary education in 14 municipalities located throughout the Netherlands. The selected municipalities included two major cities, eight medium-sized municipalities, and four small municipalities. Within these municipalities, 69 schools were contacted, of which 60 were willing to participate in the research. Dutch secondary education is highly stratified, with children having to make choices that influence whether they will be able to attend university at the age of 12 already. All levels of education of Dutch secondary education were represented in the sample (VMBO-B (lower vocational education), MAVO/VMBO-T (lower general secondary education), HAVO (higher general secondary education) and VWO (pre-university education) (Nagel, 2007). The inequality in the Netherlands is largely due to difference in the parental resources (cultural, economic and social) that matter so much at the age of 12 (Keijer et al., 2016). Within each school, a sample was drawn of three classes of different level-grade combinations within schools. This procedure resulted in 190 classes of which 148 actually participated. The response rate is 87% at the school-level and 78% at the class-level. In each class, students completed a questionnaire during a regular lesson (45–50 min). A total of 1544 students participated in this study. Because of the classroom nature of the survey, selective non-response can be assumed to be quite low.

In January 2006, parents received a postal questionnaire concerning their child’s future plans. In two-parent families, one randomly chosen parent was approached; in single-parent families, the child’s co-residing parent was approached. Eventually, this led to 1001 adolescent-parent pairs taking part in the research. Non-responding parents had a slightly lower level of education than responding parents.

Measurement instruments

Expected field of study

Adolescents’ expectations regarding their future field of study were measured by asking: “If you are thinking about going into higher education, in which field of study do you think that will be?” A list of thirteen fields were offered: (1) teaching, (2) languages, history, theology, (3) agriculture, (4) mathematics, physics, (5) engineering, (6) transportation, (7) healthcare, (8) economics, (9) law, (10) socio-cultural education, (11) social care, (12) arts, and (13) public order and safety. They had to indicate the likelihood of each field of study on a 4-point scale (1 = definitely not, 2 = probably not, 3 = probably, and 4 = definitely). In Table 1, the percentage of students stating that they will probably or definitely opt for a specific field is presented. Healthcare and socio-cultural education were the most popular fields among women, whereas economics and technical studies/engineering were the two most popular fields among men. Of all the surveyed fields of study, agriculture (rural studies) was the least popular among both boys and girls. The biggest difference in popularity between boys and girls was found for technical studies. Healthcare, social-cultural studies, and personal and social care studies also showed a significant difference in popularity between boys and girls. Girls chose the latter three studies more often.

To determine the extent to which these fields of study can be considered as intrinsically or extrinsically rewarding, evaluations from an expert panel were employed. The thirteen fields of study were presented to 52 student counselors working in secondary schools in the Netherlands. These student counselors give advise to students at all levels of secondary education. They were recruited through two student counselor associations, namely the Association of Careers Advisors (VvSL) and the Dutch Association of Careers- and Student Advisors, (NVS-NVL). They were asked to rate each of the thirteen fields of study on a 4-point scale (1 = primarily intrinsic, 2 = more intrinsic than extrinsic, 3 = more extrinsic than intrinsic, and 4 = primarily extrinsic), based on their assessment of why adolescents opt for each of these fields. Based on an inter-rater reliability analysis, the scores of three study advisors were found to differ strongly from all others and were removed from the data. The scores of the remaining 49 counselors had an average item-total correlation of 0.98. Subsequently, these responses were averaged per field of study and ranked from intrinsic to extrinsic (see Table 1). The study advisors viewed the fields of languages, history, theology and art as the most intrinsically rewarding, while they viewed law and economics studies as the most extrinsically rewarding.

To arrive at an overall score of the extent to which students expected to opt for extrinsically or intrinsically rewarding fields of study, three steps were taken. First, adolescents’ expectation scores for the thirteen fields of study were centered (recoding them from a 1 to 4 scale to a −1.5 to +1.5 scale). Next, the resulting score for each field was multiplied by the standardized motivation scores derived from the counselors’ assessments. And finally, these thirteen scores were averaged. The result was an overall score for each adolescent on a unidimensional scale indicating to what extent they expect to opt for fields of study that are extrinsically rewarding or fields of study that are intrinsically rewarding. Adolescents favouring extrinsically rewarding fields of study, like economics and law, score higher on this scale than adolescents favouring intrinsically rewarding fields of study, like the arts or teaching.

Parenting values

Parents were asked to respond to eleven statements about how they raise their child. Examples of these statements include, “I allow my child to solve his/her own problems” and “I teach my child to respect authority”. The response categories to the 11 statements ranged from 1 = not at all true, 2 = not true but not false, 3 = somewhat true, to 4 = completely true. These statements can be divided into Kohn’s child-rearing values of conformity and self-direction. A confirmatory factor analysis showed that two latent variables, termed ‘conformity’ and ‘self-direction’, could be distinguished. These factors were not orthogonal to each other, but positively correlated (r = 0.33 for boys and r = 0.21 for girls). Table 2 presents the question wording of all items, with the factor loadings from the confirmatory factor analysis. The factor loadings are reasonably high, suggesting good measurement quality.

Parents’ socio-economic status (SES)

Two dimensions of parental SES were distinguished, reflecting the economic and cultural status of the parental home. Parental cultural status was measured as a latent variable based on the educational attainment of both parents. The educational level of both parents was measured on a scale running from 1 (no education) to 9 (university). Subsequently, the levels of education of both parents were recoded using the newly developed International Standard Level of Education (ISLED) scoring system (Schröder and Ganzeboom, 2014). ISLED is an empirically derived, internationally comparable interval scale for educational level, the value of which can vary between 0 and 100.

Parental economic status was measured by parents’ income. Information on income per parent was collected on a scale of 1 to 16, where 1 referred to ‘no income’ and 16 referred to more than € 5000 net income per month. This scale was converted to a ratio scale by assigning a parent the median income for their income class (e.g., € 1750 for those in the € 1500–2000 income class). Parents in the highest income category of € 5000 or more were given a score of € 5500. The joint income of both parents was then calculated by summation. Subsequently, family income was standardized through the application of equivalence factors (Siermann et al., 2004). As a result, the income of households of different sizes and compositions can be compared more effectively. As the survey was only submitted to one of the parents, it was assumed that the parent who filled in the questionnaire had a sufficient understanding of the education and income of his or her partner.

Educational level of the adolescent

The adolescent’s current level in secondary school is used as a control variable in all analyses. The answers were again recoded into ISLED codes, and ranged from 31.90 to 69.80 (Schröder and Ganzeboom, 2014).

Analysis strategy

Structural equations modeling (SEM) was used to estimate the relationships between parental SES, parents’ child-rearing values and adolescents’ expected field of study choices. SEM allows to simultaneously test the complete conceptual path model shown in Fig. 1. To account for item non-response in the data, the models were estimated in Mplus using the method of ‘full information maximum likelihood’ (Muthén and Muthén, 2004), with a cluster correction applied at the class-level. The models were estimated on 1512 adolescent observations with a valid score on gender. Several models were estimated: the first model used the overall score on the intrinsic-extrinsic reward scale as the dependent variable (range from −1.91 to 2.82), whereas the second model used adolescents’ separate assessments of whether they expected to follow a study in the 13 different fields of study as dependent variables (range from 1 to 4). The models were estimated separately for boys and girls. The estimated SEM models included both manifest (represented by rectangles) and latent variables (represented by ovals), as depicted in Fig. 1. In the models presented in Figs. 2 and 3, we tested whether the unstandardized effects could be constrained to be equal for men and women. If so, this is indicated in the figures. However, because we report standardized effects rather than unstandardized effects, the standardized effects of these constrained parameters could still differ slightly from each other.

Results

Testing the overall model

First, we tested our hypotheses with our key measure of extrinsic/intrinsic fields of interest as the dependent variable. Direct and indirect effects are presented in Figs. 2 and 3 for men and women, respectively. Total effects for variables that have both direct and indirect effects are shown in Table 3. To test our hypotheses on the total influence of parental SES, the total standardized effects of the cultural and economic status of the parents on the intrinsic-extrinsic scale were estimated. Hypothesis 1a stated that the higher the economic status of the parents, the more likely it would be that their children’s expect to opt for extrinsically rewarding fields of study, whereas hypothesis 1b suggested exactly the opposite. The results in Table 3 show that, in line with H1a, for both boys and girls the economic status of the parents had a positive effect on adolescents’ expectations to choose extrinsically rewarding studies. The second hypothesis postulated that children whose parents had a high cultural status would make more intrinsically rewarding expected field of study choices than children whose parents had a low cultural status. The generic analysis of the intrinsic/extrinsic scale in Table 3 supported this idea, as a negative effect of cultural status of the parents on the extent to which adolescents expect extrinsic field of study choices was estimated. However, the effect of parents’ cultural status on the intrinsic/extrinsic scale were weaker for male than for female adolescents (Wald-test, p-value = 0.039), suggesting that parents’ cultural status has a stronger effect on the field-of-study choices of girls than of boys.

Hypothesis 3 stated that as parents adopt a more conformity-oriented parenting style, their children will have stronger expectations to choose extrinsically rewarding studies. Figures 2 and 3 show that a focus on conformity in parenting was indeed correlated with extrinsic field of study choices for boys (β = 0.162, p < 0.01), but that this was not true for girls (β = −0.032, ns). Hypothesis 4 focused on the impact of a self-direction-oriented parenting style on field-of-study preferences. It was expected that as parents have a more self-direction-oriented parenting style, their children will make more intrinsically rewarding and less extrinsically rewarding field-of-study choices. For boys, this effect is not found (β = −0.071, ns). For girls, Fig. 3 even demonstrates that, contrary to the hypothesis, self-direction correlated positively with the expectation to opt for extrinsic fields of study (β = 0.129, p < 0.05).

The fifth hypothesis stated that the effects of economic and cultural status on expected field of study were mediated by self-direction and conformity (Fig. 1 (a×b)). Before addressing the hypothesis, we will briefly discuss the direct effects of parental economic and cultural status on child-rearing values (Fig. 1 (b)). Figures 2 and 3 show that parents’ cultural status was negatively related to conformity, with the effect for girls (β = −0.328, p < 0.01) being larger than that for boys (β = −0.246, p < 0.01). The higher the cultural status of parents, the less emphasis was placed on conformity requirements and rules. In addition, for both boys (β = 0.179, p < 0.01) and girls (β = 0.178, p < 0.01), there was a positive relationship between parents’ cultural status and self-direction. Parents with a higher cultural status put more emphasis on self-direction in socialization than parents with a low cultural status. Parental economic status had no relationship with child-rearing values. With regard to the degree of mediation of the effect of economic and cultural status by child-rearing values, it turned out that, although there are significant relationships between parents’ cultural status and their child-rearing values (Fig. 1 (b)), and between child-rearing values and whether fields of study were classified as extrinsic or intrinsic (Fig. 1 (a)), the indirect effects of economic and cultural status through conformity and self-direction were not statistically significant (Fig. 1 (a×b)). Therefore, child-rearing values did not mediate the effect of parental status on the expected field-of-study choices of their children. Hypothesis 5 was rejected.

Analyses by field of study

We also performed the same SEM analyses for each of the 13 fields-of-study separately. Direct effects for all independent variables are presented in Table 4 for women and in Table 5 for men. Fields of study are ordered from intrinsic to extrinsic, based on the expert assessments of study advisors.

For girls, results were in line with expectations. Although the results were much less clear-cut than for overall model, the patterns were very comparable. The economic status of parents correlated positively with preferences for extrinsically rewarding studies in economics and law whereas negative effects were observed for several more intrinsically rewarding fields of study, like art, teaching and nursing. For other studies there was no clear relationship between parents’ economic status and their children’s expected prospective field of study choices. Parents’ cultural status was positively correlated with a preference for socio-cultural and arts education among girls. Furthermore, girls with parents with a high cultural status had a weaker preference for extrinsically rewarding fields of study like economics or law. With regard to child-rearing values, conformity was positively correlated with preferences for teacher training and healthcare, relatively intrinsically rewarding studies. However, a more conformist upbringing correlates negatively with studies in languages, history, theology, economics, and personal and social care. Overall, these results imply that the hypothesis that more conformity leads adolescents to choose extrinsically motivated studies has to be rejected for girls. In addition, there were significant positive correlations between self-direction and the expectation to choose transportation, law, public order and safety, mathematics and physics and socio-cultural training, which are predominantly intrinsically rewarding fields-of-study. These field-of-study specific results confirm our general finding that a more self-direction-oriented parenting style leads girls to opt for more extrinsically rewarding fields-of-study.

For boys, the individual analysis of the thirteen fields of study, summarized in Table 5, showed that the economic status of parents correlated positively with preferences for studies in economics and law. Furthermore, several expectations to opt for more intrinsically rewarding fields of study correlated negatively with parents’ economic status, which was also in line with hypothesis 1a. Teacher training was less attractive when the parents’ economic status was higher, and the same was true for mathematics and physics. However, parents’ economic status was negatively correlated with the expectation to choose technical studies. In addition, boys’ expectations for socio-cultural education correlated positively with the economic status of the parents. Parents’ cultural status was only positively correlated with a preference for mathematics and physics, which confirms the general finding that parents’ cultural status only had a limited effect on boys’ preferences for intrinsically rewarding fields of study. Conformity had a significant positive effect on boys’ preferences for studies in the fields of healthcare, law, and public order and safety, the latter two being extrinsically rewarding fields of study. However, no relation was found between conformity and other relatively extrinsically rewarding studies, like economics, studies in transport and technical studies. There were no positive correlations between self-direction and intrinsically motivated fields of study. Self-direction during upbringing for boys was even negatively correlated with the expectation to continue one’s study in the fields of language, history, and theology. However, the negative effect of self-direction on the expectation to choose extrinsically rewarding fields of study like law and public order and safety can be considered in line with expectations.

Discussion

This study examined to what extent adolescents’ expectations about their future field-of-study choices are influenced by their parents’ socio-economic status and child-rearing values. We were particularly interested in whether adolescents expected to opt for study fields that reap extrinsic rewards like money or for study fields that are more intrinsically rewarding. Following Bourdieu (1986), two dimensions of parents’ socio-economic status were distinguished, cultural and economic status. With regard to economic status, two contrasting hypotheses were formulated. On the one hand, one could expect children whose parents have a low economic status to opt for extrinsically rewarding study fields—as this would increase their financial security—whereas one could also argue that it is mainly children of parents with a high economic status that opt for such studies—to retain their strong economic position. The empirical findings clearly indicated that parental economic status increased rather than decreased the likelihood of their children expecting to opt for extrinsic fields of study. For instance, economics and law were positively correlated with parents’ economic status, for both boys and girls. In the Netherlands, income-dependent subsidies make the costs of pursuing an education at schools and universities reasonably homogeneous across socio-economic strata. In addition, these costs are relatively low compared to Anglo-Saxon countries. Therefore, we interpret the effect of parents’ economic status in the Dutch context not so much as a sign that high parental income is needed to pursue extrinsically rewarding fields of study, but rather as signifying that parents who have a high economic status transmit their preferences for fields of study and jobs that permit the acquisition of such high economic status to their children. We also observe, like Davies and Guppy (1997), that the expectation to choose a technical study is negatively correlated with parents’ economic status. Technical studies, adjusted to the adolescent’s educational level, may be more interesting to boys from a lower socio-economic background, because these studies reflect the perceptions and values of the profession of their working-class fathers.

Our hypothesis that children of parents with high cultural status were more likely to expect to opt for intrinsically rewarding study fields than children of parents with low cultural status was supported for girls, but not for boys. Thus, in general parental economic status correlated positively with extrinsic field-of-study expectations, and parental cultural status correlated negatively with extrinsic expectations. This was also reflected in the results with regard to specific study fields. For boys, mathematics, physics and teaching are positively correlated with cultural status, but negatively with economic status. These more intrinsically rewarding fields of study are therefore mainly chosen by adolescents from households that are higher on the cultural status dimension than on the economic. The same process is evident in socio-cultural studies and the arts for girls; these fields of study are particularly popular among girls whose parents are higher on cultural status than on economic status. More extrinsically rewarding fields of study, like economics and law, show the opposite pattern: the expectation to opt for this type of study is positively correlated with parents’ economic status, and negatively with their cultural status. Thus, these results largely support Bourdieu’s ideas about a two-dimensional status hierarchy.

Parents’ parenting values, in particular how much emphasis they put on conformity and self-direction, were thought to be influenced by the parents’ socio-economic status and, in their turn, to influence children’s expectations about their future field of study. We found a strong negative influence of parents’ cultural status on conformist parenting values, while cultural status had a positive effect on self-directed parenting values. Parents’ economic status, on the other hand, had no effect on parenting values. Thus, the ways in which parents rear their children—emphasizing conformity or self-direction—is affected by their cultural status, rather than by their economic status. This does not imply that economic status is unimportant in socializing children. Rather, it could be that economic status influences more what children value than how they should behave—cf. Rokeach’ (1973) distinction between terminal and instrumental values.

Hypotheses 3 and 4 postulated that parental child-rearing values influence the expected field-of-study choices of their children. In line with hypothesis 3, an upbringing characterized by conformity increased the likelihood that boys expect to choose an extrinsically rewarding study. If we consider the separate fields of study, it appeared that conformity has a positive effect on two extrinsic fields of study for boys, namely law and public order and safety. For girls, no relation was found between conformity and the degree of extrinsic motivation of the studies they prefer. Rather, the results seemed to suggest that—in choosing for a future field of education—girls whose parents put a high value on conformity are likely to be influenced by gender-stereotypic motives. The positive correlation among girls between conformity and expectations to opt for the educational fields of teaching and healthcare seems to fit traditional educational and occupational gender stereotypes. Gender-stereotyping is only part of the explanation though: there was no relation between conformity and two other typical female fields of study, socio-cultural education and personal and social care studies, and a negative one with languages, history and theology. Boys’ field-of-study choices could also partially be regarded as reflecting gender stereotypes. The breadwinner motive suggests that their choices for a ‘clearly defined’ gender-stereotypical field of study lead to a stable/good income (lawyer, soldier/police or doctor, though not technical studies).

Parents’ emphasis on self-direction values only influenced the expected field-of-study choices of their daughters, but in the opposite direction as expected in Hypothesis 4. A stronger influence on self-direction increased the expectation of daughters that they would opt for an extrinsically rewarding field of study, and in particular for the fields of mathematics and physics, transportation, public order and safety, and law. This finding may again relate to the idea of gender-stereotypical field of study choices. Girls’ choices for such study fields as mathematics, physics and transportation suggest a break with gender-specific patterns. An emphasis of parents on self-direction could strengthen general feelings of independence in their daughters, and this could explain both the choice for a non-gender-specific field of study and for a field of study like law that could be viewed as a means to achieve this goal of independence.

Our final hypothesis postulated that the effect of parents’ economic and cultural status on their children’s expected field-of-study choices was mediated by self-direction and conformity. However, we found no support for this mediating role of parenting values, despite the significant relationships between the two dimensions of social status and parental values, and the significant relationships between parental values and expected field-of-study choices. Thus, it seems likely that other mechanisms are needed to explain the influence of parental socio-economic status on their children’s expected field-of-study choices. One potential explanation could be that it is not just parents’ position on the general cultural and economic status dimensions that influences their children’s field-of-study choices, but that the actual educational and occupational fields in which parents were or are active is more directly transmitted, e.g., with children from parents who work in socio-cultural occupations developing a preference for studies and occupations in this same field as well. Thus, one promising avenue for future research could be to examine to what extent parents transmit specific preferences for fields of study and occupation. In addition, parents’ socio-economic status may influence the peer networks in which adolescents become engaged, and these may influence the future life plans of these adolescents.

A few additional issues for future research could be mentioned as well. First, given that the two dimensions of social status have a relatively weak relationship with conformity, it is important to examine which other aspects of social background influence this parenting value. For instance, parents’ religiosity may be important in this respect. Second, in our questionnaire, we used expert opinions to categorize fields of study as extrinsic or intrinsic. However, it would also be interesting to ask directly for adolescents’ motivations for their field-of-study expectations. Finally, the cross-sectional nature of our study did not allow us to study how realistic adolescents’ expectations were. Using panel data, it would be interesting to examine to what extent adolescents’ expectations have been realized, and whether the same processes influence both their expectations and their actual behavior.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Baumrind D (1971) Current patterns of parental authority. Dev Psychol 4(p2):1–103

Beck U (2002) Individualization: institutionalized individualism and its social and political consequences. Sage Publications Ltd, London

Berk LJ (2000) Child development, 5th edn. Allyn and Bacon, Boston

Blau PM, Duncan OD (1967) The American occupational structure. Am Soc Rev 21:290–295

Bluestone C, Tamis-LeMonda CS (1999) “Correlates of parenting styles in predominantly working-and middle-class African American mothers”. J Marriage Fam 61:881–893

Bodovski K, Farkas G (2008) “Concerted cultivation” and unequal achievement in elementary school”. Soc Sci Res 37:903–919

Bonvillian G, Murphy R (2014) The liberal arts college adapting to change: The survival of small schools. Routledge, New York, NY

Bornstein MH, Bradley RH (2014) Socioeconomic status, parenting, and child development. Routledge, New York, NY

Bourdieu P (1986) The Forms of Capital. In: Richardson JohnG ed The handbook for theory and research for the sociology of education. Greenwood Publishing Group, Westport, CT, pp. 241–258

Breen R, Goldthorpe JH (1997) “Explaining educational differentials”. Ration Soc 9:275

Conger RD, Ge X, Elder GH, Lorenz FO, Simons RL (1994) Economic stress, coercive family process, and developmental problems of adolescents. Child Dev 65:541–561

Davies S, Guppy N (1997) Fields of study, college selectivity, and student inequalities in higher education. Soc Force 75:1417–1438

Dornbusch SM, Ritter PL, Leiderman PH, Roberts DF, Fraleigh MJ (1987) The relation of parenting style to adolescent school performance. Child Dev 58:1244–1257

Fehrmann PG, Keith TZ, Reimers TM (1987) Home influence on school learning: Direct and indirect effects of parental involvement on high school grades. J Educ Res 80:330–337

Ganzeboom H, Nagel I, Liefbroer AC (2005) [p.i.]. Youth and culture. a multi-actor panel study; cultural participation and future plans. [machine readable datafiles]. Vrije Universiteit [producer] To be archived, Amsterdam, 2006

Giddens A (2013) Modernity and self-identity: Self and society in the late modern age. John Wiley and Sons, London

Goyette KA (2008) College for some to college for all: Social background, occupational expectations, and educational expectations over time. Soc Sci Res 37:461–484

Goyette KA, Mullen AL (2006) Who studies the arts and sciences? Social background and the choice and consequences of undergraduate field of study. J High Educ 77:497–538

Howell FM, Frese W, Sollie CR (1984) The measurement of perceived opportunity for occupational attainment. J Vocation Behav 25:325–343

Johnson MK, Mortimer JT (2011) Origins and outcomes of judgments about work. Soc Force 89:1239–1260

Johnson MK, Mortimer JT, Lee JC, Stern MJ (2007) Judgments About Work Dimensionality Revisited. Work Occup 34:290–317

Keijer MG, Nagel I, Liefbroer AC (2016) ‘Effects of parental cultural and economic status on adolescents’ life course preferences. European Sociol Rev 32:607–618

Kelsall RK, Poole A, Kuhn A (1972) Graduates: the sociology of an elite. Methuen, London

Kerr C (1991) The great transformation in higher education, 1960-1980. Suny Press, New York, NY

Kohn ML (1963) Social class and parent-child relationships: An interpretation. Am J Sociol 68:471–480

Kohn ML, Schooler C (1969) Class, occupation, and orientation. Am Sociol Rev 34:659–678

Lareau A (2011) Unequal childhoods: Class, race, and family life. University of California Press, Berkeley

Leung PW, Kwan KS (1998) Parenting styles, motivational orientations, and self-perceived academic competence: A mediational model. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 1–19

Lucas SR (2001) Effectively maintained inequality: education transitions, track mobility, and social background effects. Am J Sociol 106:1642–1690

Ma Y (2009) Family socioeconomic status, parental involvement, and college major choices—Gender, race/ethnic, and nativity patterns. Sociol Perspect 52:211–234

Maccoby EE, Martin JA (1983) Socialization in the context of the family: Parent-child interaction. Handbook of child psychology. John Wiley and Sons, New York, NY

McLoyd VC (1990) The impact of economic hardship on black families and children: psychological distress, parenting, and socio-emotional development. Child Dev 61:311–346

Muthén LK, Muthén BO (2004) Mplus user’s guide. 3rd. Muthén and Muthén, Los Angeles

Nagel I (2007) Cultuurparticipatie tussen 14 en 24 jaar: intergenerationele overdracht versus culturele mobiliteit. In: Liefbroer AC, Dykstra PA (ed.) Van generatie op generatie. Gelijkenis tussen ouders en kinderen. Amsterdam University Press, Amsterdam

Nix RL, Pinderhughes EE, Dodge KA, Bates JE, Pettit GS, McFadyen‐Ketchum SA (1999) The relation between mothers’ hostile attribution tendencies and children’s externalizing behavior problems: The mediating role of mothers’ harsh discipline practices. Child Dev 70:896–909

Parsons T, Halsey AH (2014) The school class as a social system. Schools and society, a sociological approach to education. Sage Publications Ltd, Los Angeles

Pulkkinen L (1982) Self-control and continuity from childhood to late adolescence. Life-span Dev Behav 4:63–105

Redford J, Johnson JA, Honnold J (2009) Parenting practices, cultural capital and educational outcomes: the effects of concerted cultivation on academic achievement. Race Gender Class 16:25–44

Rimkute L, Hirvonen R, Tolvanen A, Aunola K, Nurmi JE (2012) Parents’ role in adolescents’ educational expectations. Scand J Educ Res 56:571–590

Rokeach M (1973) The nature of human values. The Free Press, New York, NY

Schröder H, Ganzeboom HBG (2014) Measuring and modelling level of education in european societies. Eur Sociol Rev 30:119–136

Sewell WH, Haller AO, Portes A (1969) The educational and early occupational attainment process. Am Sociol Rev 34:82–92

Siermann C, Teeffelen P, Urlings L (2004) Equivalentiefactoren 1995-2000. Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek, Voorburg/Heerlen

Steinberg L, Lamborn SD, Dornbusch SM, Darling N (1992) Impact of parenting practices on adolescent achievement: Authoritative parenting, school involvement, and encouragement to succeed. Child Dev 63:1266–1281

Van de Werfhorst HG, Luijkx R (2010) Educational field of study and social mobility: Disaggregating social origin and education. Sociology 44:695–715

Weiss LH, Schwarz JC (1996) The relationship between parenting types and older adolescents’ personality, academic achievement, adjustment, and substance use. Child Dev 67:2101–2114

Wicht A, Ludwig-Mayerhofer W (2014) The impact of neighborhoods and schools on young people’s occupational aspirations. J Vocation Behav 85:298–308

Acknowledgements

Work on this article has been funded by a grant to the project “The Influence of Family and School on Future Life Plans of Adolescents” from the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO) (projectnr 400Y09Y116).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The project design was approved by Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research. As the project does not involve human biological material, approval by the Research Ethics Committee is not applicable.

Informed consent

Data collection for this study was approved by Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research. None of the individuals are recognizable from the data and the data is the declared at Data Archiving and Networked Services (DANS).

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Keijer, M.G. Effects of social economic status and parenting values on adolescents’ expected field of study. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 8, 303 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-021-00992-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-021-00992-7

- Springer Nature Limited