Abstract

This article discusses the usefulness of studying regional powers through a ‘politics-of-scale’ lens. We argue that this approach, borrowed from political geography, helps to better understand whether and how actors navigate the complex landscape of ‘scales’ in international politics. The combination of regional powers literature with political geography allows us to grasp the unexplored nuances of how power behaviour transcends regional and global levels and what actors (beyond the state) and processes constitute it. We test the empirical applicability of ‘politics-of-scale’ with the help of two country studies within the field of environmental politics: Japan, whose regional power status has been contested, but has used cooperation in the field of environment to establish itself as a regional leader within different spaces of its neighbourhood and Australia, which has reconstructed its climate regionalism in order support domestic politics and related to important domestic interest groups.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

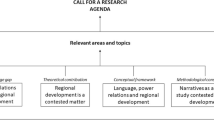

This article describes the contribution of a politics-of-scale approach derived from political geography to the study of regional powers and the study of ‘regions’ in international relations more broadly. We argue that an integration of scalar thinking will help alleviate several shortcomings in the literature—for instance, regarding the interlinkages between the ‘regional’ and the ‘global’, the absence of a clear definition of the regional spaces in which regional powers presumably lead, and the role of non-traditional actors in shaping their own spaces of power and interest. The article begins with a brief discussion of the two sets of literatures, focusing on areas of overlap and mutual enrichment. We focus on three aspects: first, the broadened spectrum of regional power agency; second, the ontological status of the region, the politicization of space, and the formation of regions as political tools; and third, the understudied impact of multiscalarity, multiplicity, and simultaneity on how actors craft and use scalar politics to achieve their interests.

The focus of this article is on concept and theory by providing arguments for the inclusion of a Politics of Scale framework into International Relations in general and the Regional Powers Research Programme more specifically. We suggest a conceptual framework by developing ‘guiding questions’ for helping the analysis and for helping to uncover regional power dynamics that conventional approaches miss. Yet, we also illustrate some of the empirical and theoretical implications of our propositions with the help of two case studies and examples from multidimensional environmental politics. We have chosen this issue area, first, because it is in environmental politics that the scalar approaches have developed. This makes some of the language used in scalar politics more easily adaptable. Second, global environmental politics is particularly interesting, as environmental issues intuitively seem tied to specific spaces and amenable to cooperation at regional levels among neighbours who are exposed to similar environmental challenges, a process enhanced by the presence of a regional power with the capacity to solve environmental problems and assume leadership in times of crisis. Third, there has traditionally been a lack of attention to environmental issues in the regional powers research programme (RPRP) and, conversely, a lack of attention to power politics in global environmental politics (Morrison et al. 2019), which makes this mutual engagement an important contribution to both areas of research.Footnote 1

We use the cases of Japan and Australia to both illustrate the breadth and potential of a scalar approach to the IR, the RPRP, and the study of regions and regionalism more specifically. The two cases are useful examples as both are entrapped in complex regional frameworks and they share that the Indo-Pacific has emerged as a new and important regional framing to them, mostly linked to their security, but as will we show, also beyond and within which they both attempt to act as regional power. The crafting and re-crafting of a regional ‘idea’—the Indo-Pacific—is central to each country’s regional powerhood also at the intersection of environment and security, yet, in different forms and processes, and by different actors.

Regional powers, space, and scales

Regional powers research generally starts with the determination of which actors are dominant and hence should at least aspire to regional power status within a given, specified region.Footnote 2 This ascription of regional powerhood across realist, liberal, and institutionalist theories hinges on military capacity, on the one hand, and economic and trade-related capacities, on the other; in all these theories the territorial state remains the central actor. Regions, assumed to be clearly distinguishable from other scales, are almost self-evidently considered to be fixed playing grounds for these actors, over which these actors are destined to have control. These actors’ form of engagement with the region is assumed to be significant for the structure of the regional order and its institutions, for peace and conflict, and increasingly for the global order as a whole. Different approaches lead to different conclusions about the causal processes linking regional powerhood with outcomes such as regional institutionalization, regional stability or instability, and the provision of regional public goods (Prys 2012; Frazier and Stewart-Ingersoll 2010; Destradi 2010). Yet, independent of the processes assumed to take place, most approaches share several ontological and epistemological challenges. Alongside critical political geographers, we argue that at least some of them have to do with the absence of the problematization of both space and statehood prevalent in much research, and even more so in regional powers research (Agnew 1994; 2015; Swyngedouw 2004; Sjoberg 2008; Adamson 2016).Footnote 3

Much of the existing research on regional powers conceptualizes the state as a unitary actor. Although there are exceptions (Beck 2014; Kausch 2017; Mattheis 2021), non-state actors have not featured significantly as either bearers of regional powerhood themselves or as a major influence on state regional powers’ foreign policymaking. Moreover, differences in statehood (which go beyond the difference between democracies and autocracies) are often left out of research designs. Instead, ‘the’ state is an ‘ideal-type or logical object … rather than a particular state and, thus, states can be written about without references to the concrete [geographic] conditions in which they exist’ (Agnew 1994, 58). This is, from the perspectives of the Global South, and from an area studies view, a considerable obstacle on the path towards better explanations and insights, which necessarily include historical and geographic factors. For instance, only a few states, if any, are ethnically homogeneous, and societal processes do not stop at the border.

An important consequence of this treatment of the state is that the region of regional powers is also mostly conceptualized as an interstate phenomenon. Thus, the outcomes of the exercise of regional powerhood, including regional institutions and norms, are also largely limited to those at the interstate level—as the central arena for the construction, reconstruction, and deconstruction of regional orders. This makes the ontological status of the region as a space for interaction volatile in the sense that it is dependent on state action for its existence and its meaning; other forms of regionality or forms of localism are marginalized (Wimmer and Schiller 2003, 576). Much research on regional powers thus conceptualizes the essence of regions as ‘interacting states’, constituted by (representatives of) states negotiating, arguing, being in conflict, etc., with (representatives of) other states. This leaves little room for the inclusion of, for instance, societal variance and consolidates the boundaries of the regional nation-states as the ‘natural’ and unquestionable boundaries of specific regions. As such, the notion of the region exposes an ontological solidification, which brackets its physical geography, history, and sociology and excludes these factors as points of interest for the RPRP (Paasi and Metzger 2017, 21).

Political geographers have noted that even approaches that engage with and rely on explicitly variable regional contexts in research designs (e.g. comparative regionalism) use geography as a fixed point, which provides a static environment for state (inter)action; in doing so, these approaches implicitly assume that regions remain constant over time and space. Even constructivist approaches to region-building that assume that regions are ‘built’ (Neumann 2003) diverge from a scalar approach in that ‘theories of scale … go beyond social constructivism to recognize the co-constitution of the physicality and social properties of political interaction. Geographical scales are not simply physical or social concepts, but they incorporate both for a broader understanding of global politics’ (Sjoberg 2008, 478). Regional powers research is mostly set in ‘a closed world of interstate relations in which the working of power at other scales and across networks is ignored’ (Agnew 2015, 45). This ignores questions about the different meanings and extensions of regions and there is little reflection on how regions can be constructed and reconstructed to include and exclude issues and actors—and can hence crafted to serve the interests of powerful actors, for example.

We also find that the absence of scalar thinking is not only theoretically limiting but also leads to several existing empirical puzzles prevailing in the RPRP. A considerable amount of regional powers research, for instance, continues to struggle with the question of why some apparent—by material definition—regional powers do not engage more constructively with ‘their own region’, by providing specific public goods or trading sufficiently with their neighbours (see Fawcett and Jagtiani, this issue). We argue, however, that this ‘scholarly’ puzzle emerges from a continued treatment regions as fixed, miniature ‘global systems’ to which the rules and principles of traditional global-level hegemony theories can be applied, raising expectations about a provision of public goods and some often underspecified ‘leadership’ ambitions. This has been a popular fallback option of most of the regional power literature of the early 2000s and more than only remnants of this line of argumentation continue to flourish (for a critique, see Prys 2012; 2013). Taking the case of India, it not only seems obvious that it has only little ambition to take on regional leadership, or to contribute to the development of regional order in any constructive manner (Hurrell 2006, 8) but that, at the same time, it is inescapably influenced by its regional neighbourhood, This simultaneity of regional dominance and wider global ambitions is hard to capture via the linear, uniscalar theories that are prevalent in all IR paradigms. Actors can be tied into various kinds of interactions and networks across levels, and it is difficult for external observers (from politics and from academia) to determine which arena, which level, or which network is of the greatest importance or priority for any actor. Strict levels-of-analysis thinking, where each actor has a clear position that is easy to observe and assess, is hence ‘performatively unrepresentative of the ways that global politics work’ and is potentially flawed in its ‘lack of attention to political process’ (Cox 1981; cited in Sjoberg 2008, 475). In other words, levels-of-analysis thinking does not allow for a focus on the simultaneity of different engagements, the multiplicity of identities, and other ambiguities that are relevant to global politics but occur across or even outside of the usual arenas.

Our main point of critique from a scalar lens about IR research on regions in general and the RPRP is that it frequently underestimates how spaces, locations, and scales can be politicized and thus form an important aspect of regional power; the ability to shape what comes to be understood as the region. In our conceptualization, this becomes one of the key indicators of regional powerhood in addition to material and other social factors. Applying a scalar framework allows instead to uncover ways in which actors use or are subjected to this kind of politicization, which plays a key role in understanding regional and global political dynamics. This implies, for instance, that a state can attempt to shape ‘its region’ according to specific prioritized issue areas in which it might have material or other advantages. Regional power politics might include coalitions of state and non-state actors working together (or against) one another in making specific framings of a region more or less prominent. While complicating research on regional powers significantly, a scalar lens thus helps to steer away from the present trivialization of regional powerhood: with the bracketing of the ontology of regions, the ‘regional’ is implicitly or explicitly limited to serving as either a stepping stone towards great powerhood and the transcendence of almost trivial, bounded localism or a means of consolidating and strengthening the nation-state (Söderbaum 2013, 13) without much significance in and of itself. Our (and other) case studies show that ‘the region’ is an important playground for many actors, yet ‘the region’ can mean many things to many actors. A case in point is that the ‘regional power’ designation has also been used as an instrument to exclude other actors from greater significance in world politics. We thus find that standard regional powers research often fails to capture how states and other actors, spaces, regions, and so forth can be reconfigured and new identities, forms of power, and relations can emerge (Lambach 2021; Sjoberg 2008, 493).Footnote 4

Politics of scale and scalecraft

In political geography, the concept of ‘scale’ has been used—generally speaking—in two basic ways:Footnote 5 first, to describe the physical and social organization of the world, and second, and more relevant to the purposes of this article, to explain and showcase processes of spatial ordering, shaping, exclusion, and other ‘power tools’ in so far mostly domestic settings. Yet, as a theoretical tool and ontological and epistemological premise, there is no reason why politics of scale and, more particularly, the notion of scalecraft should not be employed to critically study the processes and constructions of regional powerhood. Indeed, Ó Tuathail and Agnew, in their seminal article ‘Geopolitics and Discourse’, argue that ‘intellectuals of statecraft’, i.e. foreign policy elites,Footnote 6 use, develop, construct, and ‘make real’ different meanings of space and scales, with direct implications for their audiences and for regional and global politics at large (Ó Tuathail and Agnew 1992, 193).

This implies, in essence, that scale needs to be problematized as a tool in power relations. Scale is ‘a way of framing political-spatiality that in turn has material effects [and] … can shape the meaning of space’ (Jones 1998, 27, also see Van Lieshout et al. 2017). So, while a scale ontology emphasizes the connectedness and interactions of levels, as well as the interactions of (physical and other) structures and practices, it understands scales as the ‘contingent outcome of the tensions that exist between structural forces and the practices of human agents’ (Marston 2000, 220). Level-thinking instead arguably results in division and separation. Scales are thus inherently relational and intersubjectively constructed and allow for the opening of boundaries, both geographical and even non-geographical ones, and, as the case studies will show, new policy spaces in which environmental purposes and security needs intersect. It therefore becomes a central goal in political geography to ‘understand how particular scales become constituted and transformed in response to social-spatial dynamics’ (ibid., 221). This understanding offers good linkages to the RPRP, where the separation of levels has led to important challenges (described above) both at the theoretical and empirical level.Footnote 7

So, how does thinking about scale help us with research on regional powers? Overall, we find it useful for regional powers research to treat ‘scales as “powerful and institutionalized sets of practices … rather than concrete things” … [resulting in] a type of analysis which center[s] on how particular constructions of scale dominate ways of understanding the world and how these are used and constructed by actors in their everyday work’ (Papanastasiou 2017, 43).Footnote 8 Scale is hence not just a point of spatial reference for discussing the scope and location of a particular issue or policy problem. Scales are identifiable, particularly through the practices and discourses (Bulkeley 2005, 883; Engels 2021, 2) used by actors to ‘frame and define, and thereby constitute and organize, social life’ (Moore 2008, 218). By adopting this scalar perspective, the central and new objectives of RPRP could—and should—be to study how assumed regional powers contest space and its boundaries; how they thereby contribute to spatial constructions and deconstructions; and how they use the inclusion and exclusion of specific actors, issues, or structures to achieve their specific policy objectives. Identifying these practices unearths sources and mechanisms of power that have been understudied to date, including differences in mobility across scales, the capacity to ascribe particular meanings to spaces, and the ability to successfully engage in other social ‘strategies and struggles for control and empowerment’ (Swyngedouw 1997, 141; cited in: Brenner 2001, 608; Heathershaw and Lambach 2008, 271; Ó Tuathail 1996, 6:1).Footnote 9 What this means more concretely is that scaling is a political act and the use of specific descriptors, including ‘Central America’, ‘Indo-Pacific’, or ‘G2’ is—at least at times—knowingly and strategically used, for example, to include and exclude particular actors.Footnote 10

We offer the following specification of these broad assumptions for an applicable conceptual toolkit. We focus on three selected but highly intertwined aspects, which we describe as the who, where, and how of regional powerhood, but we expect them to be applicable beyond regional powers. Considering (1) the ‘who’ points the fluidity and hybridity of regional orderings, which allows, for instance, for the inclusion of the diplomatic and foreign policy-related practices of substate entities (often labelled ‘paradiplomacy’) (Cornago 2018; Kuznetsov 2014). Such practices can have an impact on the dominance of the central government in foreign policy–related manners and even articulate ‘new geopolitical configurations’ based on identity, religion, and ethnicity that may ‘summon a region into existence’ (Jackson and Jeffrey 2021). Agency in regional power studies thus is not necessarily limited to state actors, while we stick to the notion that in most cases state actors are the most important ones, but instead come from a position of openness regarding the kinds of actors who engage in scalecraft to shape regions and regional orders. This requires in-depth knowledge of the field, but also promises to yield novel, and noteworthy results.

For example, a highly relevant case study by Jackson and Jeffrey (2021) examines how the Russian Orthodox Church has created legitimacy for a shared ‘region’ between Russia and the Republika Srpska by using different forms of social and cultural capital to substantiate an ‘idea of an interlinked and joint region’. Geopolitical relations and processes thus can emerge from the bottom up, in an improvised and opportunistic manner, and through unconventional resources. This is enabled and enhanced by digital technologies, which dissolve the hierarchies of ‘local, national and global proximity’ (Sassen 2012, 466, 468; Adamson 2016, 25). Regions, in this sense, are ‘spatial, contextual groupings’, and the important question regarding their formation and continued existence is who or what shapes these groupings and what kind of processes of inclusion and exclusion take place. Moreover, different actors have varying abilities to move across different scales, and it would be interesting to explore the different preconditions for such mobility, as well as the potential actor influences related to it.

A politics-of-scale lens (2) requires asking about ‘where’ does regional power politics takes place. As noted above, despite a decades-long research tradition, some fundamental ontological and epistemological issues remain when it comes to the discussion of the spatiality of regional powers, above all the theoretical underpinnings of ‘region-building’. A politics-of-scale lens evinces a clear procedural understanding of global politics and helps to insert the constitution of the region into the analytical focus, specifically it allows us ‘to theorize multiple actors and multiple processes in the same studies’ and helps resolve the ‘fundamental incompatibility of the concept of levels of analysis and the realities of global politics’ (Sjoberg 2008, 476). Asking open questions, including ‘where and why do regional and global politics take place, what processes lead to the formation and dissolution of regional orders, how can the fluidity and hybridity of actors and structures be captured in the context of social relations and physical geography?’ allows going beyond thinking about the regional and the global as levels that are clearly distinguishable and hierarchically ordered. A scalar approach conceptualizes such entities as historical products that are both socially constructed and politically contested and thus warrants the necessary flexibility and hybridity in the definition of regional spaces. The institutionalization of a region, for instance, is, through a scalar lens, only one of many possible forms of political organization within a space, but not necessarily the only one. The same geographical space could also be structured differently by different sets of actors, such as religious institutions or different forms of capital, yet the same or overlapping regional spaces can also simultaneously serve multiple purposes for the more traditional actors, such as national and subnational governments.

While the persistent focus on ‘natural boundaries’ (for instance, oceans or mountain ranges) in conventional regional powers research is understandable because it is parsimonious, many authors nevertheless agree at least to some extent that regions can change and are therefore at least partially constructed. Constructivist research, for instance, that looks at region-building engages with processes of the social construction of geographic spaces, yet, the crucial difference to a scalar approach is, in scalar thinking, first, that region and non-region are not always clearly separable and that there can be different regions within the same physical geography that serve different purposes for different (but also overlapping) actors.

Thus, in absence of an understanding of regions as malleable scales, the ontological status of the region remains precarious. While the significance of regional interlinkages, regional institutions, and regional cultures is obvious on the ground, a good theoretical reason for drawing or conceptualizing specific regional boundaries is absent. Politics-of-scale approaches can help put other types of questions at centre stage, rather than only clearly delimited regions.

In practice, we can observe the significance of such understandings as the meanings of labels such as South Asia, Indo-Pacific or even India shift, depending on context and perspective, historical background, and specific physical-geographic and social changes; this malleability should necessarily impact our analysis of regional powers and their interests, beliefs, and strategies. This fluidity and hybridity of labels is a tool in the hands of powerful actors. Cartography is not a constant relationship but a social one, which can be both explanans and explanandum. This also implies that there are an infinite number of potential levels of global politics and that we should engage more thoroughly with the complex processes of the co-constitution of these levels, as well as the participating actors and the social and physical processes.

Politics-of-scale thinking invites using ‘scalecraft’ (Papanastasiou 2019; Fraser 2010) as an approximation of forms of power that have so far not been systematically included in the IR toolbox, and obviously also in research on regional powers. This concept refers to ‘the techniques and creativity involved in articulating policy using particular representations of scale’ (Fraser 2010). This can evoke notions of (regional) hegemony, as the most powerful tool of actors engaging in scalecraft is the production of ‘common sense’ among their audience about specific representations and legitimations of scalar constellations (Papanastasiou 2019). We describe this as, (3), the how question, which looks at regional power politics of scale as a means to solidify the region and for the constant construction and reconstruction of regional spaces as opposed to other entities, often knowingly and with strategic intent. Processes of meaning-making are interesting in this regard, as are more subtle forms of power. As a first step, it is thus necessary to draw ‘attention to actors’ skills and agency amidst the structures of opportunities and constraint that constitute the politics of scale’ (Fraser 2010, 11). Such skills and agency can involve the establishment of institutions or governance structures, for example, that ‘alter the socio-spatial conditions in specific sites’. Power and authority can then be rescaled to other places and include or exclude different actors and issues, governed by different rules and norms across these spaces. Actors thus have, depending on their capacities, the ability to bring about scalar processes that contribute to their aims and interests; a focus on processes helps map out ‘the complexities of spatial arrangements in ways that are more sophisticated than a simple levels-of-analysis approach’ (Adamson 2016; Sjoberg 2008). The reality or truth of regions changes together with economic, social, and spatial narratives; this is thus an evolutionary process, which often occurs gradually.

We can describe one such process as ‘regional siting’, which emerges out of political contestation and refers to the use of specific scalar narratives and practices that can be systematically analysed. There are a few concrete examples of regional-siting in the literature—for instance, studies on the emergence of ocean regions as new arenas for regionalism, which complement hitherto predominantly land-based regionalisms. Sengupta describes, for example, how new narratives have been constructed about historical interactions. These narratives geographically (and geopolitically) reorder the world and therefore have implications for a broad range of issues: ‘the maritime border has been a crucial site of experimentation and a spate of new policy is blurring “inside” and “outside” national space, reconfiguring border security and reorganizing citizenship and labour rights’ (Sengupta 2020, citing Cowen 2010). Another example is the impact of infrastructural development that shapes and reshapes borderlands.Footnote 11 For instance, in India’s Northeast, the Indian government has been building large and often ineffective (and environmentally damaging) hydropower plants and other forms of water infrastructure, which have transformed the border environment from a classic frontier to a strategic corridor into Southeast Asia, presumably to curb Chinese influence there (Gergan 2020, 2). We could extend our perspective, for instance, to diasporas that link resource-rich spaces with resource-poor one; a politics-of-scale approach can analyse how ‘actors gain advantages from the unique resources and opportunities that exist across various scales’ (Adamson 2016, 28).

Politics of scale are thus compatible with and, at least in part, a corrective to research on regional orders and regional powers, but also IR more broadly. What regional powers research can take away from the politics-of-scale approach for its understanding of the region is that ‘scalar craft’ or ‘scalar practices’ can open the way to using the ‘regional scale’ as an explanatory factor (in terms of scale-framing, the roles of spatial or other narratives in achieving particular [foreign] policy goals and interests). This focus on processes, for instance, allows for the use of the label ‘region’ without reproducing fixed geographies as an unwanted by-product, as has so often occurred in constructivist-minded regional powers research of the past. In other words, we can continue to use the concept of regions without necessarily essentializing it, and at the same time include the contributions of non-state actors and institutions to gain a dynamic understanding of regions and their meaning in time and space. Focusing on the processes and agency of region-building, of scaling, and of rescaling also allow for questions about the differentiation (and therefore simultaneities) of issue-specific regional orderings—for example, showing that the location of politics is important, but not fixed.

We use two case studies, Japan and Australia, to illustrate a few aspects of the conceptual thinking underlying the scalar approach to study regional powers. We first review existing literature on their respective regional spaces, then problematize the three major questions of ‘who’, ‘where’, and ‘how’, as defined above. Japan has often been studied through a global lens as global or potential global power; and yet, the region plays an indispensable role in its respective foreign policy. Australia is traditionally thought of as a middle power, but the global context is essential to Australian regional powerhood and understanding of the Indo-Pacific, as are domestic dynamics that determine whether Australian policy of regional integration tilts towards community-building or the construction of a security architecture.

Japan in East Asia

The Japanese perceptions of the East Asian region have evolved significantly in the last decades. There has been a steady rise of challenges for Japanese diplomacy, such as the emergence of China as a superpower, the rapid progress of the North Korean nuclear program, and the shifts in American policy in the region. Observers have illustrated how these security challenges provoked a re-evaluation of Japanese foreign policy into a ‘new’ form and have used terms such as ‘normalization’ and ‘security renaissance’ to define the profound changes the country has undertaken, such as building up its defence capabilities, revisiting regional alliances, and building new ones including the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (see, for example, Izumikawa 2020, O’Shea and Maslow 2020; Tamaki 2020, Hosoya 2019, Dobson 2017; kolmas 2021).

The evolution of the concept of the Indo-Pacific has been the most visible sign of this preoccupation with security in the approach to regional politics. Although once a non-relevant and scarcely used concept, under former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe the Indo-Pacific became the central focus of Japanese foreign policy narratives. Since Abe’s speech on ‘the confluence of the two seas’ in 2007, the concept of the Indo-Pacific came to dominate regional debates and was incorporated into official discourses and security strategies of several key actors including the USA, Australia, and the European Union (c.f. Yoshimatsu 2019; Sato 2019).Indeed, the Indo-Pacific is a highly relevant term for Japanese security policy and security preference vis-a-vis mounting regional challenges. But the security-relevant regional rescaling has had a profound effect on other regional initiatives and actors far outside the field of security. Following the theme of this study in illustrating the scalar nature of regional policymaking, the puzzle here is how despite its limited ecological relevance, the security-relevant Indo-Pacific region became a venue for Japanese environmental diplomacy. To grasp the nuances in this process, including the variety of engaged actors, their transboundary linkages, and the role of ideational factors such as norms, we aim to highlight other forms of regionality or forms of localisms that are marginalized in conventional regional powers research, and the intersection of policy (security x environmental) fields. We divide the study according to these aims into who, where and how.

The most important actor in Japanese regional environmental diplomacy has been the state. This is understandable given the fact that Japan is widely understood to possess a highly top-down political system, where power is in the hands of a limited group of politicians mostly drawn from the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) (see Shinoda 2013; Pugliese 2017). Much of the conventional regional power literature has thus focused on the region as directly influenced by Japanese high politics and strategy. Much in this vein, the Indo-Pacific has also been framed as the creation of a singular politician (Shinzo Abe), as if there were no other meaningful actors influencing the way in which the region is imagined and defined. Indeed, the Japanese government (and particularly the Prime Minister’s Office Kantei) has been instrumental in guiding Japanese diplomacy. But other actors were prominent in this regional rescaling. The Japanese bureaucracy is a particularly interesting actor in Japanese regional environmental policymaking. Although formally devoid of foreign policy power, various ministries and their agencies have been instrumental in the definition of Japanese aims and targets. For instance, the powerful Fisheries Agency of the Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry (MAFF) had nearly exclusive jurisdiction over Japanese whaling policy. The agency, which is existentially dependent on the continuation of Japanese whaling, was instrumental in the formation of Japanese anti-International Whaling Commission (IWC) stance and has often represented Japan in its meetings. It has also presented Japanese scientific evidence on whale stocks, which were prepared by the ‘quasi-governmental’ think tank Institute for Cetacean Research (Hirata 2004; Clapham 2015).

The Environmental Ministry (MoE) also promoted the government’s security agenda via different channels. It adopted a more conciliatory tone to address Japan’s turbulent relations with its neighbours China and South Korea. The three countries adopted the Tripartite Environmental Ministers Meeting (TEMM) format in 1999, with the aim of ‘[promoting a] candid exchange of views and strengthening cooperation on environmental issues not only for the region but for the entire globe’ (MoE 2021). The TEMM meets yearly and has adopted several action plans, the latest for 2020–2024, and created joint programmes on topics including decarbonization, sustainable urban development, and experience-sharing vis-à-vis waste management. Despite being promoted by governments, these initiatives have often largely functioned at the non-state or subnational level and therefore have attracted significant interest from the Japanese business community. Interest from this domestic coalition may be one reason the TEMM format continues, even as relations between its member states worsen.

Japanese powerful industries were similarly important in environmental policymaking. In particular, the industrial, nuclear, and oil lobbies (organized in the business federation Keidanren) have been very vocal in their opposition to strong environmental pledges. Using large media campaigns, they have played the strings of popular anxieties about Japan’s economic prospects, which go back to the Japanese bubble crisis of 1990. They have not always been successful in their campaigns—as was visible when they failed to prevent the Kyoto Protocol—but they have played a significant role in many of Japan’s environmental, as well as political initiatives including the country’s final decision to withdraw from Kyoto in 2013. The significant role of the business community in policymaking is possible because of the strong connection between the LDP and the Keidanren. Forming an ‘iron triangle’ (together with bureaucracy), the business community has often complemented the state’s political preferences, including its preferential regional settings and modes of intervention. In this vein, Japanese banks have played a substantial role in ‘filling up’ the Indo-Pacific security doctrine with environmental investment. Institutions such as the Japan Bank of International Cooperation (JBIC) and the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) have promoted Japanese environment-related investment. Since 2010, they have made substantial investments in high-tech ‘green’ projects addressing energy efficiency, greenhouse gas emissions, environmental management, water conservation, and other issues across the Indo-Pacific (Silverberg and Smith 2019).

What is striking here is the fact that Japanese media and NGOs have played a very muted role in environmental policymaking, especially regarding promoting alternative forms of environmental policy. NGOs often have limited access to the policymaking process, and their campaigns typically take a conciliatory tone. Media coverage of environmental issues is also limited in Japan. Most influential media are private, but they have a remarkably close relationship with the state through the so-called kisha kurabu (journalist clubs), though which they gain information. Although there are alternative media (especially in the form of weekly magazines shukanshi), its readership and influence lags behind the mainstream ones. Several studies (Nakai 2017; Hasegawa 2022) have shown that outside of major events such as UNFCCC COPs, there is virtually no coverage of environment-related issues in Japanese media.

These governmental and industry actors have been particularly important in shifting the perception of ‘where’ the region lies. Prior to the 2000s, Japanese environmental diplomacy targeted the global level. Not only did it make little sense from the ecological and economic viewpoints to focus on environmental diplomacy within the Indo-Pacific (as there are very substantial differences in terms of ecological habitats, climate-induced threats, levels of economic development and resulting institutional strategies to tackle them), but Japan was also in the process of ‘reframing’ its identity from the post-war ‘low profile’ Yoshida doctrine towards an independent and proactive member of the international community (Hagström, 2015). In the 1990s, Japan sought to become a global leader in world politics, framing its post-war impediments of foreign policy ‘masochistic’ (jigyakuteki) and looking to normalize its security and foreign policy. Japan’s hosting of the COP eventually reflected this—and despite significant internal opposition within the influential business community (Michal Kolmas)—produced the Kyoto protocol.

But with the rise of the significant security threats in East Asia following the end of the Cold War, Japan rescaled its leadership policy to a region it understood to be more relevant to its security agenda. In other words, despite these dynamics being global in scope, the Indo-Pacific became the key focal point of this political transition. The United States was particularly important for Japanese rescaling. Although the 1960 security alliance remained in place even after the fall of the Soviet Union, its original goal of preventing Soviet invasion of the country vanished after 1991. To keep the USA interested in East Asia, Japan rescaled the scope of the alliance in the 1997 New guidelines for the alliance which made it regional by expanding where Japan’s military could operate (from its home islands to ‘surrounding areas’). Some perceived the move as Japan taking greater responsibility for its own defence and for the whole region of the Asia–Pacific (c.f. Maizland and Cheng 2021). Nonetheless, as security challenges including the rise of China became more apparent, it became clear to Tokyo that the Asia–Pacific scale would no longer be sufficient to address its security concerns. The need to incorporate India in the balance of power drove Japanese policymakers to rescale the region to the doctrine of ‘Indo-Pacific’. For Japan, changing geopolitical realities boosted India’s importance in balancing China, and the rapprochement between the USA and India created suitable circumstances for Abe’s regional rescaling.

Japanese environmental diplomacy has often been analysed as devoid of such a security dimension (Takao 2012; Morishima 2003; Sakaguchi et al. 2021). But the rescaling to the Indo-Pacific shows the clear interconnection of these policy fields. Framing the region as Indo-Pacific did not make much sense for Japan in terms of trade (India was never member of regional economic initiatives including the Japan-led Trans-Pacific Partnership, TPP and the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership, RCEP), nor in terms of ecology (despite some shared marine habitats there were substantial differences in terms of environmental/climate strategies as well as ecological conditions). But the security domain has pressured actors to advance their cooperation on these terms. Japan has embraced this security narrative and has reached out to South and Southeast Asia to foster this nascent security coordination in non-security matters.

Tokyo established the recurrent Japan–ASEAN Dialogue on Environmental Cooperation in 2007, paving the way for a set of bilateral environmental mechanisms with Southeast Asian states including Indonesia and Vietnam, but also with Mongolia and China. Japan’s bilateral environmental partnership with India is among the most significant. Mirroring the increasing importance of the Japan–India strategic partnership, and security cooperation within the Indo-Pacific policy of former PM Abe, Japan has been among the most significant investors in India’s economic transformation during the Modi government, chiefly within the infrastructure, energy, and water management sectors (Silverberg and Smith 2019). However, cooperation has not been solely limited to the bilateral level; rather, it has encompassed a broader set of actors in a push to further integrate India within the recently framed Indo-Pacific region. This was clearly visible in the establishment of the Japan-led security organization Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (Quad). In 2017, signalling the centrality of the Indian Ocean to the Indo-Pacific, Japan and India announced the ambitious Asia–Africa Growth Corridor, an economic cooperation initiative that included multiple African countries and aimed to develop, inter alia, quality infrastructure as well as skill enhancement in agriculture and agro-processing ‘in compliance with international standards established to mitigate environmental and social impact’ (Chaudhury 2017). These initiatives show the intersection of policy fields that have contributed, or even constituted, the space for Japanese environmental policy.

Initially, Japan sought to address the global scale in its environmental policymaking. Japan is active in many international organizations. For instance, Japan was among the founding members of the International Whaling Commission, and despite its general dissatisfaction with how the organization operated, it remained a member even after the 1986 moratorium on whale hunts was implemented and other large whaling nations including Norway and Iceland clearly stated they would not follow the ruling. Similarly, Japan took an active role in the United Nations’ environmental and development programs (UNEP and UNDP), promoting the concept of human security. The above-mentioned Japanese role in the formulation of the Kyoto Protocol should also not be underestimated. Japan’s declaration of its intent to withdraw from the Kyoto Protocol damaged the credibility of its aspirations for leadership, as did its increase in the production of fossil fuel-based electricity after the Fukushima disaster of 2011. PM Abe engaged in extensive diplomacy to salvage Japanese credibility, maintaining that Japan would not back down on its commitments, and even urging the world in a 2018 Financial Times editorial to ‘Join Japan and act now to save the planet’ (Abe 2018). But such politicking could not mask the fact that Japan’s carbon emissions grew. Furthermore, Japan’s position on the Paris Agreement was a underwhelming one. It pushed for a market-based mechanism for carbon trading and opposed compulsory financial transfers from developed to developing countries (Dimitrov 2016). Japan’s NDC used the baseline of 2013, instead of the widely used 1990 one, for its energy reduction and the pledges were lower than those of other developed nations.

While Japan’s position on the Paris Agreement was sceptical, it became much more invested in environmental cooperation in the Indo-Pacific. What rescaling to the region produced in practical terms was that while symbolic commitment to multilateral institutions would remain present in Japanese policymaking, the practical, results-oriented policymaking would retreat to the regional, minilateral, and bilateral formats. Japan’s push for a regional scale of environmental leadership was linked to the necessity of building partnerships with emerging powers and middle-income economies to counter the rise of China, especially with respect to Chinese investment, innovation, and trade. Although promoted by the Japanese government, these regional initiatives incorporated a multiplicity of non-state stakeholders and policy entrepreneurs, especially large Japanese conglomerates, and financial institutions, which have long enjoyed a symbiotic relationship with the LDP. In cooperation with these actors, the government raised significant funds for innovation and infrastructure projects in Southeast and South Asia, especially through the Asian Development Bank (ADB), totalling $30 billion, aiming to add another $80 billion by 2030.

To sum up, there are several relevant takeaways for the politics-of-scale approach. Although Japan was initially conducive to environmental politics on the global level (due to its identity-seeking) and regionally within the Asia–Pacific, it rescaled it to fit with the newly security-relevant region of the Indo-Pacific. The new region had little ecological relevance for Japan, but it became filled with environmental initiatives that mirrored Japan’s security interests. Coalitions of actors in- and outside the Japanese government, including bureaucracy, banks, and business groups, drove these initiatives.

Australia in the (Southwest) Pacific

IR research often treats the Southwest Pacific as an extension of the Asia–Pacific, more recently of the Indo-Pacific, and as a region increasingly characterized by bilateral competition between the USA and China (Saeed 2017). Within this context, Australia is conceptualized as an actor that has gradually transitioned from a policy of hedging against China (Jackson 2014) to a much closer alignment with the USA (Lim and Cooper 2015). Other studies focus on the growing importance of intra-regional bilateral relationships with Japan (Wilkins 2021), South Korea (Park 2016), India (Lee 2020), and Southeast Asia (Frost 2016), or Australia’s engagement with the UK (Tsuruoka 2021) and the EU Strategy for Cooperation in the Indo-Pacific (Mohan 2020). Australia’s role and status as a regional power is not a product of a dominant position in the regional balance of power, but the result of its key role in community-building and the maintenance of the regional security architecture (Wilkins 2017). There is a focus on security at the expense of other issue areas, and the transition from the Asia–Pacific to the Indo-Pacific frame has not led to attention being shifted to the processes by which ‘Indo-Pacific’ as a constructed region implicitly encompasses different forms and scopes of regionalisms (Southeast Asia, Southwest Pacific, Indian Ocean) depending on the institutions and actors framing the region.

By contrast, the debate on Australian environmental policy focuses on domestic factors (Lowe 2020) and the prevalent antagonistic framing of environmental versus energy security (Taylor 2014; Ali et al. 2020). This also means that there is comparatively little writing on Australian regional (or other) environmental diplomacy, aside from a consideration of the growing security dimension of the environment in the region (Dunlop and Spratt 2017). Nevertheless, through a scalar lens we can find that the linkages between Australian domestic debates on environmental policy and Australian regional powerhood remain significant and intersect with Australia’s position as a notable climate laggard among the industrialized economies (UNEP and UNFCCC 2020; Climate Action Tracker 2021). Most notably, this frames the puzzle as to why Australian political actors—especially the conservative Coalition governments—used security-driven concepts of the region in environmental policy and diplomacy, despite the lack of a substantive link to ecological realities. Research on subnational actors in environmental policy identifies key actors, such as cities, which can play significant and constructive roles beyond that of their national governments. However, the story of Australian environmental policy between 2013 and 2022 is one of intense climate scepticism and inaction; the powerful subnational actors involved hail from media and industry spaces, with significant transnational linkages to like-minded actors elsewhere in English-speaking industrialized countries. The prevalent separation between the global, regional, and domestic has limited the possibilities for an integrated understanding of Australian regionalism and regional integration in traditional IR literature. Exploring the ‘who, where, and how’ of the politics of scale instead allows for a finer-grained analysis that shows how scalar processes allowed, for instance, domestic actors in Australian politics to constrain or enable specific frames that articulate Australia’s identity as a regional power and the scope of its region. As we show in the following, it can also illustrate how an issue such as environmental governance can be included or excluded from forming part of a larger ‘regional project’, despite not being at the core of a government’s policy agenda.

The Labor governments under PMs Kevin Rudd and Julia Gillard (2007–2013) positioned Australia as a middle power working towards a balance between economic and military responsibility and a commitment to the rules-based order (Teo 2018). This period was characterized by hedging against China, and by growing engagement and community-building beyond the Southwest Pacific (Wilkins 2017), traditionally a recipient of Australian aid and influence, into the greater Asia–Pacific. The most ambitious attempt at furthering regional integration through a multilateral mechanism was Rudd’s project for an Asia–Pacific Community (APC) (Rodan 2012), which would include the Southeast Asian states in regional governance on transnational security and environmental problems. ASEAN states, however, did not support the project, considering it an external intrusion into existing Southeast Asian regional integration (Rodan 2012). The Rudd government also attempted to move away from ‘pushy’ or ‘bullying’ bilateral relationships with the other member states of the Pacific Islands Forum (PIF) and towards greater multilateralism, although this was not entirely successful (Hawksley 2009). The inauguration of the conservative Coalition after 2013 marked a transition in Australian regionalism. Beginning with the Defence White Paper of 2013 (DoD 2013), the successive conservative Coalition governments of Tony Abbott (2013–2015), Malcolm Turnbull (2015–2018), and Scott Morrison (2018) reframed the scope of their regional frame of reference from ‘Asia–Pacific’ to ‘Indo-Pacific’ as Australia’s geopolitical region (Scott 2013), culminating in the 2017 resurrection of the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (Quad) comprising Australia, India, Japan, and the USA. This rescaling enabled greater security cooperation with the USA due to American focus on greater containment of China (Scott 2018). Policy entrepreneurs from the more hawkish wings of both the Liberal and National parties played a significant role in this shift, which also won praise for the Coalition among the mainstream of the Australian defence establishment, ensuring substantial payoffs in national politics by enabling a ‘tough on China’ narrative. The signature of the AUKUS security pact in 2021 between the USA, the UK, and Australia, signalled that under conservative coalition leadership Australian regional powerhood should be ever more tightly connected to American strategic concerns.

Environmental policies also significantly shifted with the change of the ruling party. When Labor won the 2007 federal election, the change in government accelerated trends in Australian society, that enabled for the first time a discursive shift by which environmental policy was treated not as an impediment to economic growth, but as a necessary good due to the reality of climate change (Christoff 2013), with Australian media actors as significant drivers of the popularization of this new perspective. This enabled—or even necessitated on the part of the government—a shift in Australia’s self-understanding and positioning within the global climate regime. PM Rudd capitalized on this trend, his rhetoric on the normative and environmental aspects of environmental policy (Crowley 2013) signalling a scalar shift in Australian leadership in terms of its own responsibility, both at the global level, where Australia signed the Kyoto Protocol, and in regional multilateralism, manifested in projects such as the APC (Rodan 2012) and the PIF (Hawksley 2009).

However, this shift, which could have led to environmental diplomacy as a pillar of regionalism as in the case of Japan, proved ephemeral. Countervailing climate-sceptic actors in politics, conservative media, and Australian industry coalesced around Abbott, then a Liberal MP, and forcefully reclaimed the issue of environmental policy by rescaling it to the original framing of its antagonism vis-à-vis Australian economic growth and energy security (Crowley 2013), thereby removing it from the realm of foreign policy. As by that time Rudd’s APC, including the vision of multilateral climate mitigation policies, was effectively dead, the victory of the conservative Coalition ensured that the Australian government would not engage in regional environmental policy initiatives, which were very controversial at home, let alone abroad. As an example, the Foreign Policy White Paper of 2017 (DFAT 2017), which discusses bilateral cooperation within the frame of the Indo-Pacific, altogether omits climate or environment in its discussion of regional partnerships, aligning with the preferences of the new Abbott appointees to the DFAT. More significantly, the Australian government withdrew from the UNFCCC Green Climate Fund in 2018, even after a proposed accreditation system that would have preferentially allocated Australian aid to Pacific Island countries (PICs) and returned to a preference for bilateral relationships in the PIF.

The climate policy of the conservative Coalition government was characterized by reliance on coal and other fossil fuels and by raising emissions caps to meet its already low UNFCCC targets (Crowley 2007; UNEP and UNFCCC 2020). Although Abbott was the party activist that that brought together the push to politicize climate change, and therefore to rescale environmental policy and discourse to the climate-sceptic state of the previous period of conservative Coalition government of John Howard (1996–2007), he was not the only actor involved in this scalar process. Climate-sceptic media and fossil fuel industry lobbying took leading roles as policy entrepreneurs (Pearse et al. 2013; Baer 2016). In particular, the Murdoch media empire was a powerful proponent of the climate-denialist narrative (Christoff 2013), and enabled linkages and learning processes between Australian climate-sceptic actors and their counterparts in American and British media and industry circles, drawing on narratives of economic freedom as central to the ‘free world’. This framing identified Australia with a region that has both spatial and cultural dimensions and has a prominent role in English-speaking countries’ conservatism dating back to intense anti-Communism during the Cold War.

As a sprawling transnational conglomerate, the Murdoch media space was uniquely placed to amplify climate-sceptic voices through multiple mediums and developed remarkably close relationships with the Coalition upon which successive PMs came to rely for positive coverage. For example, before departing for the pivotal 2019 PIF meeting, Morrison’s office reassured listeners on popular right-wing radio host Alan Jones’ breakfast show that Australia would take a tough stance at the meeting, and that any aid pledged at the meeting would not mean new expenses (Greenpeace 2019). This demonstrates how this media ecosystem, in particular Sky News, shaped Australia’s regional powerhood. As a multinational conglomerate, Sky News also amplified climate denialism in other media markets, which may mutually empower climate-sceptic governments’ diplomacy. Likewise, the fossil fuel industry promoted lax rules at home and abroad and lobbied in conjunction with the media ecosystem for concepts such as ‘clean coal’ (Demetrious 2017). However, the picture of subnational actors is not complete without the role of climate-sceptic policy entrepreneurs within the Coalition itself, which played a key role in coordinating with other societal actors to constrain climate policy (Chubb 2014; Wilkinson 2020). Insufficient rhetorical and policy support for the orthodoxy of climate scepticism was used in turn to unseat Abbott in 2015 and Turnbull in 2018. During his tenure, PM Morrison was likewise beholden to party activists on climate policy (Savva 2019). Taken together, these subnational actors were a significant force in shaping the ‘acceptable’ range of government policy, which also affected Australian leadership, or lack thereof, on regional and global responsibilities on environmental policy.

However, domestic stability on environmental policy, at least within the conservative Coalition, could not mask growing domestic, regional, and international pressure for Australia to get more serious about its existing commitments (Morgan 2016) and its responsibility as an industrialized country and significant emitter (Parry 2019) to provide, if not leadership, at least followership on the environment. The Australian delegation’s weak commitments at the COP26 Glasgow summit were emblematic of continued inaction within the framework of global governance, with a target of net-zero emissions by 2050, far from the 2030 goal adopted by other industrialized nations, and no commitments even on mainstream policies such as support for electric vehicles (UNEP and UNFCCC 2020). To deflect criticism, the Morrison government announced at the annual PIF meeting in 2019 a $500 million climate aid commitment to the PIF’s developing member countries, followed by a $2 billion climate aid commitment from 2020 to 2025 to developing countries, with the vast majority earmarked for the Indo-Pacific region (DFAT 2019), effectively rescaling Australian climate commitments from the global forum of the UNFCCC to the region. The Australian government’s framing of its regional leadership as directed to the developing countries of the Indo-Pacific was telling, as this rescaled the Indo-Pacific region to the small island developing states (SIDS) of the Southwest Pacific, thereby excluding the middle-income economies of Southeast Asia and Australia’s security partners in the Quad. Ostensibly, the PIF would distribute the aid, signalling Australia’s commitment to regional leadership through regional integration and multilateral regional governance.

However, the Morrison government had to remain mindful of satisfying its constituencies in the media, the fossil fuel industry, and the Coalition policy entrepreneurs in engaging in this shift in policy and the concomitant significant financial commitment. In the 2019 PIF meeting, the Australian delegation claimed that it granted climate to the PIF as a regional organization. However, the reality that emerged following the meeting was of ‘business as usual’, with aid disbursed only on a bilateral basis and contingent upon recipient countries’ silence on climate change and environmental degradation (Greenpeace 2019). Furthermore, attempts were made to dilute the environmental aspects of the communiqué (Wallis 2021), based on Australia’s significant leverage over the other PIF members when it comes to bilateral aid. Since 2020 this has become even more acute as the PICs had to rely on Australia for COVID vaccines. Subsequent investigation of projects undertaken under this commitment to Australian regional leadership revealed that the bulk of funding was allocated to projects related to state governance or economic development that are only tangentially related to environmental policy, or fully unrelated, with a generic mention of ‘environment’ or ‘climate’ in the project description, if at all (Greenpeace 2019). This is a textbook case of ‘greenwashing’.

Rescaling environmental policy commitments to a framing of the Indo-Pacific that focused on the Southwest Pacific excluded the Quad. For the conservative Coalition, which framed Australia’s regional role through the prism of the security architecture of the Indo-Pacific, this decentred environment from regionalism, which was particularly significant for Australia’s relationship with the USA. Whereas the previous period of conservative Coalition rule (1996–2007) could rely on a firm and predictable relationship with the USA, the Trump presidency led to strained relations, although not as much for Australia as for other traditional American allies (Beeson and Bloomfield 2019). The Trump administration was deeply hostile to climate change discourse, and leading figures on the US populist right such as Fox News media personality Tucker Carlson and governor of Florida Ron DeSantis exercised significant influence over the Republican base, which raised the possibility that a future conservative Coalition government in Australia would have to avoid taking climate action, even in a ‘greenwashed’ format, if it might irritate a putative Republican US president.

The dynamics of Australian environmental politics highlight the role that scalecraft can play in the ‘who, where, and how’ of regional powerhood. A politicized scale of generalized climate scepticism, generated by a mixture of media and industry actors along with policy entrepreneurs within the conservative Coalition governments (2013–2022), significantly constrained environmental policy options. Faced with these constraints, on one hand, and with demands for greater leadership coming from Australian society and international advocacy groups, on the other hand, the Morrison government partially rescaled Australia’s environmental policy commitment to an Indo-Pacific region framed to cover the PIF member states. This scalar process enabled greater flexibility for the Morrison government, as the power imbalance within the PIF could negate meaningful policy action, while the framing of the region to exclude the Quad made it possible to compartmentalize Australian regionalism regarding the Indo-Pacific’s security architecture, notably avoiding potential American audience costs. However, this came at the detriment of global cooperation.

Conclusion and outlook

This article has discussed the contributions of a ‘politics-of-scale’ lens to the RPRP and, essentially, to the broader IR discipline. We have argued that a scalar perspective might contribute to the resolution of several inherent challenges of the RPRP, including its rather monolithic view of the state; the ontological solidification of the region; and the lack of theory regarding the creation, boundaries, and processes of regional orderings. It can also offer more sophisticated and accurate ideas on how to study regions and even conceptualize geopolitics and help research in this field to exit from a ‘closed world of interstate relations in which the working of power at other scales and across networks is ignored’ (Agnew 2015, 45). IR would benefit from moving beyond the idea that a decisive feature of regionness can be described as ‘a small number of state actors interacting’.Footnote 12

The conceptual, politics-of-scale framework we propose consists of a three-pronged set of questions about the ‘the where, who and how’ of regional powerhood. While there are no linear, unidirectional links between the three aspects, looking at a more comprehensive understanding of the ‘where’ of regional powerhood has led, also in the case study, to most progress and innovation in our understanding of regional powers. Asking about the ‘where’ of regional powerhood fundamentally transforms the fact that regions are not constant over time and space into a central analytical interest of RP research. It helps to shift our attention to the intersections of physical geography, history, sociology, economics of the region and relieves geography from its treatment as ‘as if’-fixed. Applying a scalar lens thus allows the ‘where’ to become a core analytical interest of research. This perspective also allows to study actors, behaviours, structures, or institutions, much akin to their real-world interactions, as present and operative different scales at the same time. The simultaneity of their often-contradictory interactions is thus no longer a problem to be bracketed, but a puzzle to be studied and to be developed as a core driver of foreign policy. Expanding our focus on ‘where’ also helps to expand the focus on ‘who’, or the scope of potential agents of regional powerhood. The problematization not only of space but also of unified statehood further promotes openness towards the inclusion of societal variance and helps to loosen our equalization of the boundaries of nation-states with boundaries of specific regions. We further suggested enquiring about the ‘how’ of regional powerhood, which we defined as scale-crafting or the construction, deconstruction, framing and re-framing of spaces and scales and hence, the formation of regions as political power tools. This step helps to uncover so far understudied dynamics of ‘regional’ power. This form of power is important for aspiring regional powers, as this process is likely to be a crucial first step for an actor in creating the conditions for exercising regional powerhood, whether as coercive or ‘benign’, cooperative leadership. This is, we believe a major advantage of our approach as it focuses our attention on the political process along which actors navigate their multiple identities, networks or roles across multi-scalar global politics.

Overall, we have shown how a politics-of-scale approach makes research about regional powers less ‘trivial’. For dynamics that seem to be inherently bound by geography it should be of considerable importance to study the politicization of spaces, locations, and scales and how actors can be both object and subject of this politicization. In sum, the examination of regional powers and their (foreign) policymaking using a politics-of-scale approach helps better represent and understand the contributions of a diversity of institutions, practices, and actors to regional power politics. Standard RP research has persistently overlooked some of these practices. This does not mean that traditional state actors are unimportant; we simply call for the inclusion of relevant scale-making of other actors as a matter of empirical observation, depending on context and cases.

The two case studies, Japan and Australia, have shown some of the potential of a scalar lens and illustrated novel dynamics at the cross-scalar intersection of environment/security that have previously been outside our scholarly attention. These two case studies shed light on the breadth of different mechanisms and processes a politics-of-scale approach can encompass and points to the utility of scalar thinking to highlight and compare such processes. Most importantly, the cases highlight two findings. First, differences in domestic coalitions can lead to vastly different outcomes within the region. A multiplicity of non-state and subnational actors can have a significant amount of influence on the eventual features of regional powerhood. Second, the strategy of rescaling regions to enable certain policy options can strongly serve domestic purposes, strengthening bonds between a government, interest groups and policy entrepreneurs, and granting flexibility in foreign relations. However, this process uniformly appears to come at the cost of global cooperation and leadership.

The case of Japan, for instance, demonstrated a revisionist foreign policy project, which links the regional dimension of East Asia with larger global ambitions. Contrary to Russia or China, however, Japan is far from being a counter-systemic agent. Tokyo’s main revisionist driver has been the attempt to ‘normalize’ Japanese foreign policy—that is, to recreate Japan’s status as a systemic/regional power. Although this reconfiguration has been global in scale and political in nature, the regional scale and environmental field have been key drivers or even enablers of these processes. The Japanese push for global environmental leadership in the 1990s was a coordinated push for a new ‘normal’ identity, but implementation problems resulted in a near-total retreat from this strategy. The government turned to the regional scale, where environmental initiatives complemented the construction of the Indo-Pacific region, to counter the threats posed by the rise of China. This regional scale of global politics remains essential to protecting Japanese interests and has cemented Tokyo’s identity as a regional leader.

The case of Australia evinced similarities with that of Japan. Both countries eventually ended up as laggards in environmental policy, and both define their regional powerhood through the concept of the Indo-Pacific. This concept scales the region to include India as a prime stakeholder, altering the previously common conception of the Asia–Pacific and the concurrent perceptions of growing Chinese influence within Australia’s core region. Australian concepts of regional integration rest on the pillars of community-building in a security architecture. A focus on regional community-building and a hedging approach to China was the norm during the Labor period of Rudd/Gillard (2007–2013), and environmental policymaking was characterized by a domestic discourse that treated international environmental cooperation as strongly compatible with domestic economic growth. During the reign of the conservative coalition (2013–2022), both Liberal and National party elites framed climate policy and economic growth as contradictory instead, with adherents of hard-line positions triumphing over more moderate rivals. Regionally, the Australian government moved away from the ‘Asia–Pacific’ and towards both the ‘Indo-Pacific’ with a focus on building a regional security architecture that was paramount to Australian regional powerhood. Faced with growing pressures to act on Australia’s already tepid international environmental commitments, the Morrison government attempted to rescale global commitments away from the Paris framework to the Pacific region. It argued, for example, that Australia had significantly increased funding of environmental development projects. Yet, a coalition of climate change-denying media, fossil fuel-interest groups, and policy entrepreneurs within the conservative coalition drove this approach and closer examination shows a significant degree of ‘greenwashing’ in Australian development projects. This suggests that Australian environmental politics revolved around managing domestic climate sceptics, rather than constituting a new scale of regional leadership, as in the case of Japan.

We envisage future research on regional powers, but also more broadly on regionalisms in International Relations to consider a politics-of-scale approach as a corrective to an essentialization of ‘regions’ that is, despite better knowledge, a constant feature in this field. Other applications may pay even more attention to non-traditional actors than we have in our case studies, to processes in even more unconventional issue-areas. In a next step, it may, for instance, be useful to focus more explicitly on the usage of scalecraft, on factors for success and failures of these processes and the different drivers supporting such policies. One of the advantages of our approach is that is, in principle, compatible with a broad range of theoretical foundations and we look forward to future works employing this framework in creative ways.

Notes

While research in IR takes note of ‘space’, the missing links are obvious when space is linked to power (Lambach 2021).

Adamson (2016, 29) names some approaches that have embraced this ‘spatial’ turn, including ‘human security, environmental security, and feminist approaches’ (Paris 2001; Enloe 2014) in addition to work on the Arctic (Dodds and Woon 2019; Stephenson 2018) and the construction and meaning of cyberspace (Blakemore and Awan 2016, Choucri 2012).

Politics of scale is a core concept of political geography; a comprehensive review is beyond the scope here (cf. Lambach 2021 for a IR perspective).

This may include governmental officials, but also can go beyond, including sub-national actors or cities forming transnational networks.

The focus on the analytical function of scales should not mask the importance of their descriptive function. When thinking about regional powers, it is impossible to talk about ‘reality’ without reference to levels and categorizations of space (Heathershaw and Lambach 2008, 278).

Towers (2000, 26) describes this as the scales of meaning (as contrasted with the scales of regulation, which are structured by the respective institutional settings).

The authors thank an anonymous reviewer for pushing them to make bolder their claim about the political and at least potentially intentional aspect of scalar politics.

The emerging literature on ‘energy regionalism’ addresses similar issues regarding the role of infrastructure contributing to ‘regional constellations of various geographic extents, which often transcend national and subnational boundaries’ (Johnson and VanDeveer 2021, 2).

One reviewer has expressed this so accurately that we would like to reference her words here: ‘In short, regionness is much, much more than a small number of state actors interacting, which IR has too often been unable to accept’.

References

Abe, S. (2018) Join Japan and act now to save our planet. Financial Times, 23 September, https://www.ft.com/content/c97b1458-ba5e-11e8-8dfd-2f1cbc7ee27c. Accessed 11 Feb 2022.

Adamson, F.B. 2016. Spaces of global security: Beyond methodological nationalism. Journal of Global Security Studies 1 (1): 19–35.

Agnew, J. 1994. The territorial trap: The geographical assumptions of international relations theory. Review of International Political Economy 1 (1): 53–80.

Agnew, J. 2015. Revisiting the territorial trap. Nordic Geographical Publications 44 (4): 43–48.

Ali, S.H., K. Svobodova, J.A. Everingham, and M. Altingoz. 2020. Climate policy paralysis in Australia: Energy security, energy poverty and jobs. Energies 13 (18): 4894.

Baer, H.A. 2016. The nexus of the coal industry and the state in Australia: Historical dimensions and contemporary challenges. Energy Policy 99: 194–202.

Balsiger, J., B. Cugusi, and S.D. VanDeveer. 2019. Still Saving the Mediterranean? Expert communities, regionalization and institutional change. In Contesting global environmental knowledge, norms, and governance, ed. M.J. Peterson, 33–53. London: Routledge.

Balsiger, J., and M. Prys. 2016. Regional agreements in international environmental politics. International Environmental Agreements: Politics, Law and Economics 16 (2): 239–260.

Beck, M. 2014. The concept of regional power as applied to the Middle East. In Regional powers in the middle east. New Constellations after the Arab Revolts, ed. H. Fürtig, 1–20. New York: Palgrave MacMillan.

Beeson, M., and A. Bloomfield. 2019. The Trump effect down under: US allies, Australian strategic culture, and the politics of path dependence. Contemporary Security Policy 40 (3): 335–361.

Blakemore, B., and I. Awan. 2016. Policing cyber hate, cyber threats and cyber terrorism. London: Routledge.

Brenner, N. 2001. The limits to scale? Methodological reflections on scalar structuration. Progress in Human Geography 25 (4): 591–614.

Bulkeley, H. 2005. Reconfiguring environmental governance: Towards a politics of scales and networks. Political Geography 24 (8): 875–902.

Chaudhury, D. R. (2017) India, Japan come up with AAGC to counter China’s OBOR. Economic Times, 26 May, https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/economy/policy/india-japan-come-up-with-aagc-to-counter-chinas-obor/articleshow/58846673.cms. Accessed 11 Feb 2022.

Choucri, N. 2012. Cyberpolitics in international relations. Cambridge: The MIT Press.

Christoff, P. 2013. Climate discourse complexes, national climate regimes and Australian climate policy. Australian Journal of Politics & History 59 (3): 349–367.

Chubb, P. 2014. Power failure: The inside story of climate politics under Rudd and Gillard. Collingwood, Victoria: Black Inc.

Clapham, P. 2015. Japan’s whaling following the international court of justice ruling: Brave new world—or business as Usual? Marine Policy 51: 238–241.

Climate Action Tracker (2021) Australia Country Profile. https://climateactiontracker.org/countries/australia/. Accessed 11 Feb 2022.

Cornago, N. 2018. Paradiplomacy and protodiplomacy. In The encyclopedia of diplomacy, ed. G. Martel, 1–8. Hoboken: Wiley.

Cowen, D. 2010. A geography of logistics: Market authority and the security of supply chains. Annals of the Association of American Geographers 100 (3): 600–620.

Cox, R.W. 1981. Social forces, states and world orders: Beyond international relations theory. Millennium: Journal of International Studies 10 (2): 126–155.