Abstract

The existing literature postulates that individual-level attitudes toward immigration are partly determined via the effect of immigration on the labor market. In particular, the labor market competition hypothesis states that natives should oppose immigrants with similar qualifications because they threaten their jobs. Empirical findings, however, partly contradict this expectation. In this paper, we argue that one needs to evaluate immigration attitudes in a broader context since the impact of immigration should be mediated by actual job market competition. In industrialized countries, the arrival of high-skilled immigrants happens against a background in which economic globalization positively affects the demand for high-skilled labor. Thus, the influx of high-skilled immigrants should rarely increase job market competition. The opposite occurs for low-skilled workers, for which labor market insecurity is enhanced by both economic globalization and immigration. We find some support for our argument using micro-level data from 19 European countries.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

In many industrialized countries, citizens currently not only consider immigration one of the most important issues, they also seem to be strongly divided over it (Gonzalez-Barrera and Connor 2019; Armstrong 2019; Eurobarometer 2022). Many conservative and right-leaning groups vocally reject the idea of opening their countries’ borders to foreigners. For instance, in the Brexit referendum, citizens voting for Leave prominently voiced their concerns about the insufficient restriction of immigration flows within the EU (Owen and Walter 2017). The US citizens feeling close to the Republican Party express similar objections to their country’s immigration policy (Daniller 2019). Despite such calls to restrict general immigration flows, in most industrialized countries we still observe solid support for a specific form of immigration, namely high-skilled immigration (e.g., Connor and Ruiz 2019). In light of these observations, the question arises what makes high-skilled immigration different in that it is perceived quite positively by the general public?

The literature dealing with immigration preferences does not offer a clear explanation for this. A prominent branch of this literature postulates that individual-level attitudes toward immigration are partly determined by the effect of immigration on the labor market. In particular, the labor market competition hypothesis (LMCH) states that natives should perceive immigrants with similar qualifications more negatively because they compete for the same jobs (Scheve and Slaughter 2001). Consequently, low-skilled natives should mainly oppose low-skilled immigrants while high-skilled natives should oppose high-skilled immigrants. Evidence for this argument is, however, limited since high-skilled workers do not seem to view high-skilled immigrants in negative terms (Hainmueller and Hiscox 2007, 2010).

This finding implies that high-skilled workers either do not form their opinion toward immigration based on economic self-interest or that they are rarely exposed to the theorized labor market threats. Explanations in-line with the first reasoning highlight that people either evaluate immigration based on cultural factors or based on its impact on society at large, i.e., sociotropic considerations (Hainmueller and Hopkins 2015). In the latter perspective, individuals prioritize the societal consequences of immigration over the potential personal costs it causes. Therefore, both high and low-skilled natives should support high-skilled immigration because of the believe that this type of immigration brings the most economic benefits for their home country independent of their own economic situation.

In contrast, in this paper, we argue that too little attention has been dedicated to investigating the implications of the second potential explanation, namely that high-skilled natives do not oppose high-skilled immigrants simply because they do not feel sufficient labor market competition. In particular, we propose to evaluate immigration attitudes in a broader context as we argue that the impact of immigration should be mediated by actual labor market competition (Malhotra et al. 2013; Peters 2015). In industrialized countries, the type of countries we are interested in in this paper, the baseline of actual labor market competition against which high-skilled and low-skilled workers assess the influx of similar-skilled immigrants should differ significantly. Since different forms of globalization (e.g., trade openness, off-shorability and foreign direct investments) have divergent implications for the labor market situation of high-skilled versus low-skilled workers (e.g., Girma et al. 2001; Scheve and Slaughter 2001; Walter 2010; Oatley 2015; Kaihovaara and Im 2018), the demand for low-skilled labor tends to decrease whereas the demand for high-skilled workers tends to increase in industrialized countries due to globalization (Dancygier and Walter 2015).

Consequently, in the case of low-skilled workers, both globalization and low-skilled immigration push in the same direction by increasing labor market competition. In the case of high-skilled workers, however, the two factors push in different directions: While the influx of high-skilled immigrants should increase labor market competition, this happens against a background in which globalization should increase overall demand for high-skilled workers. Thus, only if exposure to similar-skilled immigrants on the labor market is large enough, we might observe that also high-skilled workers feel the competition and react accordingly.

We test our argument that support for high-skilled immigrants should vary with actual exposure to high-skilled immigrants using micro-level data from 19 European countries. Previous studies that examine the mechanism underlying the labor market competition hypothesis with observational data rely on survey questions that capture general immigration attitudes. Our approach rests on observational data that measures whether high-skilled immigrants are the preferred type of immigrants for respondents. This more nuanced measure allows us to test our proposed argument more precisely. Our results provide support for our argument as we find that a person’s skill level and her exposure to job market competition significantly affect whether she opposes similar-skilled immigrants. Economic competition for one’s skill level therefore mediates how a person views immigrants with the same skill level. Both high- and low-skilled natives become more opposed to similar-skilled immigrants once exposure to this type of immigrants increases. In contrast, to more established findings in the literature, this effect is more pronounced for high-skilled than for low-skilled natives.

What drives immigration preferences?

The labor market competition hypothesis (LMCH) is part of a large strand of the literature focusing on the relative importance of economic factors for explaining anti-immigration sentiments (e.g., Scheve and Slaughter 2001; Hanson et al. 2007; Mayda 2008; Wilkes et al. 2008; Facchini and Mayda 2009; Meuleman et al. 2009; Dancygier and Donnelly 2012; Malhotra 2013; Hainmueller and Hopkins 2015). The LMCH assumes that individuals mainly evaluate immigration via its effect on their employment situation and that they only compete with similar-skilled immigrants for employment (e.g., Scheve and Slaughter 2001; Mayda 2008; Malhotra 2013). Therefore, natives’ labor market situation should be unaffected by immigrants with different skill levels and thus they should only oppose immigrants with the same skill endowment (Scheve and Slaughter 2001; Malhotra 2013; Hainmueller et al. 2015).Footnote 1

Empirical evidence for the LMCH is weak at best (Hainmueller and Hiscox 2007; Malhotra et al. 2013). In particular, many studies find contradicting evidence to the LMCH in that high-skilled workers, who should perceive high-skilled immigrants as labor market competition, tend to have more negative attitudes toward low-skilled than toward high-skilled immigrants (Hainmueller and Hiscox 2010; Goldstein and Peters 2014; Hainmueller et al. 2015; Hainmueller and Hopkins 2015). This means that highly educated natives’ immigration preferences seem to resemble those of their low-skilled counterparts. Thus, independent of a person’s education level opposition to low-skilled immigration seems more pronounced.

Hainmueller and Hiscox (2007, 2010) introduce a possible explanation for this puzzling finding. They argue that previous research overlooks that education not only measures a person’s skill level but also their cultural orientation, in particular cosmopolitan values. Since cultural values vary for high- and low-skilled workers this can explain why high-skilled workers have a more positive attitude toward immigrants in general. Some authors go even further and claim that cultural factors play the most decisive role in explaining immigration attitudes (Esses 2006; Dustmann and Preston 2007; Brader et al. 2008; Hainmueller and Hangartner 2013). This strand of the literature emphasizes that natives see immigrants as a threat to their national identity (e.g., Esses et al. 2006; Hainmueller and Hiscox 2007; Brader et al. 2008; Hainmueller and Hangartner 2013). As for research on the LMCH, empirical findings on the impact of cultural factors on immigration attitudes are ambiguous (Harell et al. 2012; Hainmueller and Hopkins 2015). Therefore, the jury is still out on whether economic or cultural factors are decisive in explaining immigration attitudes.Footnote 2

The most recent explanation for why natives evaluate high- and low-skilled immigrants differently highlights sociotropic concerns about immigration effects. Such arguments start from the assumption that individuals form their attitudes toward immigrants not by evaluating how immigrants affect their own personal economic situation but by considering how immigrants contribute to society more generally. Since high-skilled immigrants presumably contribute more to a country’s economic success, people are more willing to accept this kind of immigration (e.g., Hainmueller and Hopkins 2015).

In general, therefore, the sociotropic argument contradicts the assumption that immigration attitudes rest on economic personal self-interest and various studies tend to support this conclusion (e.g., Hainmueller and Hopkins 2015; Valentino et al. 2019). Does this imply that individuals do not take their own economic self-interest into account when forming their preference toward immigration? While we do not want to discard sociotropic aspects, we argue that one reason why the literature so far has found little evidence for the LMCH might be the way it evaluates economic self-interest.

This idea is supported by survey results showing that high-skilled workers started to oppose high-skilled immigrants during the great recession (Goldstein and Peters 2014); hence at a time when high-skilled immigrants suddenly posed a real economic threat and high-skilled natives felt anxious about their financial situation. Similarly, people experiencing globalization induced pressures on the labor market also viewed immigration in general more negatively than people not experiencing such pressures (Dancygier and Walter 2015; Kaihovaara and Im 2018). The most convincing evidence in this regard so far, comes from Malhotra et al. (2013). By studying the exposure of high-skilled natives to high-skilled immigrants in the information technology sector, Malhotra et al. (2013) show that natives only become concerned with similar-skilled immigrants when they actually pose an economic threat to them. As the number of high-skilled immigrants in a sector is seldomly high enough to intensify labor market competition, the economic threat posed by similar-skilled immigrants stays often hypothetical.

Taking into account actual labor market risks when determining immigration preferences

Based on the discussion in the previous section, we therefore caution from discarding the labor market competition hypothesis prematurely. Rather, we expand on the findings of Malhotra et al. (2013) by examining whether they hold beyond the context of the information technology sector. In particular, we consider the unequal distribution of economic pressure between high- and low-skilled natives in a globalized world and argue that these pressures should influence acceptance levels for similar-skilled immigrants.

Our argument starts from the assumption that the support for immigration should be affected by competition over scarce resources between immigrants and natives (Coenders et al. 2008; Wilkes et al. 2008; Meuleman et al. 2009; Dancygier and Donnelly 2013; Hainmueller and Hangartner 2013; Hainmueller and Hopkins 2015; Bansak et al. 2016). Therefore, we argue that the degree of economic pressure a person is exposed to needs to be taken into account when evaluating attitudes toward immigration. Diverse forms of globalization (e.g., trade openness, off-shorability and foreign direct investments) can potentially worsen the labor market situation of specific people by negatively impacting wages or job security (e.g., Girma et al. 2001; Scheve and Slaughter 2001; Walter 2010; Oatley 2015; Kaihovaara and Im 2018). In industrialized countries, economic globalization tends to hurt low-skilled workers rendering them decisively more vulnerable than high-skilled natives (Dancygier and Walter 2015). For this reason, we assume that low-skilled workers experience high levels of economic pressure even if their exposure to immigrants on the labor market is low. This situation is reversed for high-skilled workers, for which economic globalization tends to ease job market vulnerability (Oatley 2015).

In contrast to other forms of globalization, immigration can potentially harm both low- and high-skilled natives. Following the LMCH, immigrants pose a labor market threat to those native workers with the same skill endowment as the new arrivals (Scheve and Slaughter 2001; Mayda 2008; Dancygier and Donnelly 2012; Malhotra et al. 2013). Thus, high-skilled (low-skilled) immigrants compete with high-skilled (low-skilled) natives for jobs. Immigrants whose skills differ from a native’s skill endowment should not directly pose a threat.

The presence of similarly skilled natives, however, should only become a salient issue if the number of immigrants a native is exposed to is high enough to actually intensify labor market competition (Malhotra et al. 2013; Dancygier and Walter 2015). Consequently, the only individuals who should, due to economic reasons, view similar-skilled immigrants negatively are those exposed to an above-average number of migrants. This conditionality of the immigration effect implies that what matters for the formation of immigration preferences is not the skill level of immigrants alone but also actual job market competition.

Given their higher labor market risk due to the influence of economic globalization in general, we argue that low-skilled natives should be more sensitive toward the presence of low-skilled immigrants. Even without the arrival of immigrants, they should face serious labor market risks due to the afore-mentioned effects of economic globalization. This risk then strongly increases with the influx of low-skilled immigrants that compete for the same scarce jobs (Malhotra et al. 2013). Since sufficient employment opportunities should exist for high-skilled workers, the winners of globalization (Oatley 2015), they should feel mostly unthreatened by similar-skilled immigrants unless their numbers are high enough to strongly intensify labor market competition (Malhotra et al. 2013). As a consequence, for low-skilled workers, both globalization and low-skilled immigration push in the same direction by increasing labor market competition. This is different for high-skilled workers, for which the influx of high-skilled immigrants should increase but economic globalization should decrease job market competition.

We therefore expect low-skilled natives to, on one hand, always oppose similar-skilled immigrants, yet, on the other hand, intensify their negative attitudes if they are exposed to a higher influx of similar-skilled immigrants. In contrast, we expect high-skilled natives to only oppose similar-skilled immigrants when they are exposed to a high influx of similar-skilled immigrants.

Research design

We test our theoretical argument using cross-national micro-level data from the European Social Survey (ESS) Round 7, conducted in 2014 (ESS 2019). This particular edition of the ESS has the advantage of containing a section with questions on immigration that are only included in Rounds 1 and 7 of the ESS. This large set of questions on immigration allows us to test our theoretical argument as closely as possible using existing survey data. To the best of our knowledge, the question we use to operationalize people’s immigration preferences is unique because it assesses how someone views immigration in general and how respondents consider the educational qualifications of immigrants.

Previous studies usually rely on survey experiments to assess the mechanism we examine here (e.g., Hainmueller et al. 2015; Hainmueller and Hopkins 2015; Valentino et al. 2019). Others apply observational data, but if they do so, they often use survey questions that capture more general immigration attitudes (e.g., Scheve and Slaughter 2001; Mayda 2008).Footnote 3 This emphasis on general public immigration attitudes leads to a validity problem, however. The theoretical argument specifies which kind of immigrants should be preferred by natives while the applied measure does not. Furthermore, the ESS data allows us to produce generalizable results for the European context because it enables us to include individual-level data from 19 European countries in our analysis, all of them advanced industrialized countries, as specified in our theory.Footnote 4 Additionally, the individual-level data from the ESS can be combined with aggregate data on immigration exposure from the European Labor Force Survey (LFS) of 2013. We need this data to obtain a valid measure of actual labor market competition.

Our main dependent variable captures whether ESS respondents think it is important for immigrants to have good educational qualifications on a scale from 0 to 10.Footnote 5 While lower values indicate that a respondent finds it unimportant that immigrants have good educational qualifications, a higher value expresses the opposite. In our view, this variable measures as closely as possible whether a person is in favor of high-skilled immigrants (in this case, this respondents should indicate that good educational qualification is important) or rather in favor of low-skilled immigrants (in this case, respondents should indicate that good educational qualification is unimportant).Footnote 6 While other interpretations of the question might be possible, we still consider it the best possible measure we could identify among existing survey data.

In addition, we run models with an additional dependent variable to test our theoretical mechanism in more detail and examine whether parts of our findings might be driven by sociotropic concerns. This variable, also ranging from 0 to 10 and captures if a respondent finds it important that an immigrant obtained the work skills a country needs.Footnote 7 Therefore, it allows a test of the sociotropic argument as proposed in the existing literature because it assesses if people find it important that immigrants contribute to the overall economic success of their country. If respondents believe that it is important that an immigrant is equipped with the work skills a country needs, we argue that we can interpret this in terms of them evaluating immigration from a sociotropic perspective. The opposite is true for respondents who state that it is unimportant that immigrants have the work skills needed by their country. Repeating our analysis with this second dependent variable enables us to compare the results from our main model of interest using the importance of immigrants’ skill level as the dependent variable with the results of this sociotropic analysis. Thereby, we can contrast our argument more directly with potential alternative explanations advanced in the literature.

We rely on multiplicative interaction terms combining respondents’ skill levels with their exposure to low- or high-skilled immigrants to assess whether economic pressure caused by similar-skilled immigrants conditions the effect of skill level on attitudes toward similar-skilled immigrants. The skill level is captured by information regarding respondents’ education as documented by the ESS. The ESS captures education on a different scale than the European Labor Force Survey (LFS). Therefore, we unify the scales of both datasets to obtain a consistent measurement of education for all relevant data sets. Appendix Table A.1 provides an in-depth description of how the unification worked and shows the result of this process.

Subsequently, we coded every respondent who did not receive more than secondary education as low-skilled and respondents who received additional schooling after completing their secondary education as high-skilled (high-skilled respondent). However, in Appendix Fig. A.2, we show that the results are robust if we define high-skilled individuals as individuals with at least some university education (see, Hainmueller and Hiscox 2007, 2010).

Economic pressure induced by similar-skilled immigrants is the second component of our interaction term. Since our argument differentiates between pressure steaming from low- and high-skilled immigrants, we run two separate models. The first model contains an interaction effect between the dummy variable indicating respondents with low skills (low-skilled respondents) and the level of exposure to low-skilled immigrants (exposure to low-skilled immigrants). The second model, in contrast, contains an interaction term between the dummy variable indicating respondents with high skills (high-skilled respondent) and exposure to high-skilled immigrants (exposure to high-skilled immigrants).

The immigration exposure variables consist of an aggregated measure that calculates the relative amount of high- or low-skilled immigrants as stated by the European LFS employed in a particular industry relative to the overall number of individuals engaged in this industry expressed in percentages.Footnote 8 The information is taken from the LFS (2020) which was conducted in 2013.Footnote 9 The industry of employment is recorded in the most aggregated form of the statistical classification of economic activities in the European Community (NACE), which both the ESS and the LFS use. In Appendix, Fig. A.1, we present summary statistics of the immigration exposure variables by country.

The control variables, which we introduce into our model, reflect the focus of the literature on economic and cultural factors to explain opposition toward similar-skilled immigrants. The first group of variables captures individuals’ sociodemographic characteristics: respondents’ age and their gender (male). Additionally, we also include attitudinal factors, namely respondents’ political-ideological orientation (political ideology), how closely connected they feel to their country (identity) (Hainmueller and Hiscox 2007, 2010), and how they perceive the economic conditions in their home country (economy) (Goldstein and Peters 2014).

Finally, we also include an index measuring respondents’ attitudes toward immigrants based on their cultural attitudes toward immigration (anti-nativism score). Since we aim to get as close as possible to the economic assessment of different skilled immigrants, we do not want this assessment to be affected by respondents’ cultural assessment of these immigrants. We calculated our anti-nativism score by adding up the values of answers that respondents gave to six questions that focus exclusively on the cultural dimension of a respondent’s preferences toward immigration. The questions addressed the cultural implications of immigration in general, the importance of language, skin color, religion, and the willingness to adopt the traditions of the host country (see Appendix Table A.4). Since all questions range from 0 to 10, the anti-nativism score takes on values between 0 and 60, with lower values standing for more nativist attitudes.Footnote 10

Table 1 contains a summary of relevant information concerning the variables that we include in our regression models.

Results

To analyze how individuals’ skill level and exposure to immigration-induced job market competition affect their views on immigrants, we use multilevel regression models with random intercepts to control for the country context in which the individual-level ESS data is nested. The models that are the basis for Figs. 1 and 2, which display the interaction between skill level and immigration exposure, are based on the interflex procedure as proposed by Hainmueller et al. (2019) and are thus linear regression models including country fixed effects and cluster standard errors by country to control for the country context. For each of our two dependent variables, we first run a baseline model without interaction terms to understand how skill level and exposure to immigrants affect their views on immigration. We then run two models with interaction effects—one with an interaction effect for low-skilled natives and one for high-skilled natives—for each of our two dependent variables. Table 2 shows the results of all six models.

The results of Models 1 and 4 in Table 2 provide for the first assessment of our theoretical argument. In particular, the findings indicate that respondents with high skills in contrast to respondents with low skills respond significantly more positively to whether immigrants should have good educational qualifications and whether high-skilled immigrants are what the respective country needs. These positive effects of high-skilled respondents preferring high-skilled immigrants are in line with much of the existing literature (e.g., Hainmueller and Hiscox 2007, 2010), but they are not in line with the labor market competition hypothesis. If the latter were to hold, we should have instead observed that high-skilled (low-skilled) natives, in general, are more likely to oppose high-skilled (low-skilled) immigrants. Furthermore, only exposure to high-skilled immigrants affects respondents’ view on immigration independently, i.e., without being interacted with the skill level of an individual. In contrast, exposure to low-skilled immigrants has no statistically significant effect on respondents’ attitudes toward which type of immigrants are preferred.

With regard to our control variables, two aspects seem noteworthy. First, all control variables show effects in-line with the existing literature, therefore providing additional confidence that we have correctly specified our models. For instance, the results show that respondents who are more conservative or feel closer to their country also find it more important that immigrants are high-skilled or useful to their national economy (Gonzalez-Barrera and Connor 2019). Second, throughout all specifications, those respondents with high scores on the anti-nativism score, which implies cultural aspects of immigration are not very important to them, are significantly less likely to state that the skill level of immigrants is important. We interpret this finding as highlighting that cultural aversion to immigrants leads people to believe that low-skilled immigrants are undesirable. This might be connected to the fact that radical right-wing parties, which often resonate with people who have high cultural aversion to immigrants, tend to spread such welfare chauvinistic messages (Ennser-Jedenastik 2018).

From these baseline results, we now turn to the main test of our theoretical argument. In particular, as explained above, we provide two models for each dependent variable with a distinct interaction term. Thus Models 2 and 3 display the results for our dependent variable measuring whether the skill level of immigrants is important and Models 5 and 6 for the dependent variable measuring whether the country needs high-skilled immigrants. Since interaction effects are hard to interpret without graphical illustration, we provide figures for each interaction effect.

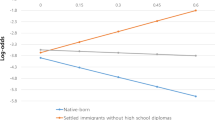

Figure 1 depicts the results for our main dependent variable, i.e., whether respondents consider high education important for an immigrant.Footnote 11 The left panel shows the interaction effect of being low-skilled and respondents’ degree of exposure to low-skilled immigrants. The right panel presents the interaction effect of being high-skilled and the degree of exposure to high-skilled immigrants. The figures are based on the interflex procedure by Hainmueller et al. (2019) and only show the part of our interaction effect supported by actual data for our mediating variable. Since 80% of our observations have an exposure level of less than 12% in case of high-skill immigrant exposure and less than 14% in case of low-skilled immigrant exposure, we decided to limit the graphs to all levels of exposure below 15%. This captures the most important variation in the data and we correspondingly do not rely on extrapolation of our results (for a detailed discussion, see Hainmueller et al. 2019). The line in each plot displays the kernel estimator for the marginal effect of low- or high-skilled respondents, and the gray area around shows the 95% confidence intervals. Each figure also contains the histogram of the mediating variable, i.e., exposure to low- or high-skilled immigrants per industry in percent.

Beginning with the left sub-figure in Fig. 1, which depicts the interaction between being low-skilled and the degree of exposure to low-skilled immigrants, the results show that with increasing exposure to similar, i.e., low-skilled, immigrants in a respondents’ industry, the likelihood of considering high education to be important for immigrants increases, though only bordering on statistical significance. This implies that low-skilled natives without pressure from similarly low-skilled immigrants are significantly more negative in assessing high-skilled migrants (and vice versa, potentially more positive toward low-skilled migrants) than high-skilled natives. However, the more exposed these low-skilled natives become, the less they differ from their high-skilled native counterparts in assessing the skill level of immigrants. Under moderate exposure to immigrants, around 8%, they show the same preference for high-skilled immigrants as high-skilled natives, thus clearly opting for the category of migrants that does not constitute additional job market pressure.

We interpret this finding to be partially in-line with our argument. In contrast to our expectations, our results do not show that low-skilled natives have negative attitudes toward similar-skilled immigrants unconditionally, i.e., with no exposure to similar-skilled migrants. Theoretically, we expected this to be the case because we based our argument on the assumption that different forms of globalization reduce the demand for low-skilled workers providing a situation in which jobs for low-skilled workers are generally scarce. This should have resulted in low-skilled natives opposing low-skilled immigrants across the board, something our results do not support. However, low-skilled natives’ opposition toward similar-skilled immigrants strengthens with a higher influx of similar-skilled immigrants resulting in the attitudes of low-skilled natives being indistinguishable from those of high-skilled natives. Therefore, this second observation is clearly in-line with our prediction that higher exposure to similar-skilled immigrants should increase opposition toward them.

The opposite pattern occurs in the case of high-skilled natives, as displayed in the right panel of Fig. 1. While high-skilled natives are significantly more positive toward high-skilled natives under conditions of low exposure, this completely reverses once high-skilled natives compete with many high-skilled migrants. This finding is entirely in-line with our theoretical argument in that only under conditions of real job market competition for high-skilled natives by high-skilled immigrants, which are indeed very rare in the industrialized countries under analysis in this paper as shown by the distribution in Fig. 1, do high-skilled natives become opposed to same-skilled immigrants.

Overall, we, therefore, consider the results, as displayed in Fig. 1, as partially supporting our argument: While low-skilled natives become more likely to oppose low-skilled immigration and to support high-skilled immigration under increasing exposure, the opposite is true for high-skilled natives if they are in a situation of intense labor market competition. However, we do not observe that low-skilled natives are already more opposed to low-skilled immigrants even without actual immigration pressures, as our baseline assumption about low-skilled natives in industrialized countries would indicate.

Turning to the assessment of the sociotropic aspect of immigration, Fig. 2 shows the marginal effects for the interaction terms if we rely on the question of whether an immigrant should have skills the respective country needs to operationalize our dependent variable. Again, as above, the interaction term for being low-skilled and the degree of exposure to low-skilled immigrants are depicted in the left panel of Fig. 2. The one for being high-skilled and the degree of exposure to high-skilled immigration can be found in the right panel.

The results for both low- and high-skilled natives exactly mirror those in Fig. 1. Under low exposure conditions, low-skilled natives are less likely to answer positively to the question that high-skilled immigrants are important for the country. Under high exposure conditions, their answering pattern again becomes indistinguishable from their high-skilled counterparts, as the insignificant effect shows. Hence under high levels of exposure, also low-skilled natives seem to opt for high-skilled immigrants as being what their country needs.

Again, this pattern is even more pronounced for high-skilled natives (right panel in Fig. 2). Here the effect is positive for low levels of exposure and turns even statically negative for higher levels of exposure. We interpret this finding to mean that under conditions of high exposure, especially the high-skilled natives no longer consider it important what their country needs. On the contrary, under circumstances of high economic competition, they start to think of what they need rather than their country. This implies that people seem to only form their preferences on immigration based on potentially altruistic consideration if they consider it feasible based on their own economic situation.

The results based on both dependent variables lead to the conclusion that high- and low-skilled natives indeed react similarly to those types of immigrants that pose a potential economic threat to them. While both high- and low-skilled natives are willing to accept similar-skilled immigrants to a certain extent, their opposition grows with increasing economic pressure posed by precisely those similar-skilled immigrants. Our findings therefore show that increasing labor market risk caused by exposure to a high quantity of similar-skilled migrants renders self-centered assessment more important. We conclude that only under relaxed economic conditions people might be able to afford altruistic views on immigration.

Conclusion

Why do high-skilled natives often not oppose high-skilled immigrants? Parts of the existing literature argues that this is the case because immigration preferences are not formed based on economic self-interest (Hainmueller and Hopkins 2015). Rather, this literature argues that immigration preferences are formed based on sociotropic considerations. While we do not want to discard sociotropic preferences in our paper, we examine a second potential explanation for the empirical finding that high-skilled natives do not oppose high-skilled immigration. In particular, we argue that immigration seldomly intensifies labor market competition for high-skilled workers because the influx of high-skilled immigrants is rarely high enough to cause economic stress (Malhotra et al. 2013). Considering the consequences of globalization more generally, we argue that especially the labor market situation of low-skilled natives in industrialized countries is tense because open borders hurt them in general (Girma et al. 2001; Scheve and Slaughter 2001b; Walter 2010; Oatley 2015; Kaihovaara and Im 2018). The same does not apply to high-skilled natives who are often identified as the winners of globalization (Dancygier and Walter 2015). Therefore, high-skilled natives should have more room to tolerate similar-skilled immigrants since the labor market can usually absorb both high-skilled natives and high-skilled immigrants. In contrast, low-skilled natives who are already under economic pressure due to other forms of globalization should perceive low-skilled immigrants as an additional economic threat leading them to reject this type of immigration.

We tested our theoretical argument using micro-level survey data from 19 European countries. Relying on multilevel regression models and regressions models including country fixed effects with standard errors clustered at the country level to account for the nested structure of our data, we find support for the fact that job market vulnerability indeed mediates individual-level preferences vis-à-vis immigration. In particular, our results show that while in general high-skilled natives tend to prefer high-skilled immigrants, this is only the case if job market competition is low. Once exposure to similar-skilled immigrants increases, high-skilled natives seem to reverse course and opt for low-skilled immigrants instead. The exact opposite pattern occurs for low-skilled natives. This supports our expectation that high-skilled/low-skilled natives should prefer low-skilled/high-skilled immigrants with increasing exposure. Generally, we can conclude that both high- and low-skilled natives need to be in a comfortable labor market position to afford themselves a sociotropic perspective on immigration.

Importantly, we also expected low-skilled natives to prefer high-skilled immigrants already under conditions of little actual exposure, something we do not find. One potential explanation for this is that by assuming that people with lower levels of education in industrialized countries always lose from globalization, we have oversimplified the complex implications of globalization for society. As with immigration, other forms of globalization might only exert pressure when people are actually and strongly affected by them and thus not all low-skilled workers might necessarily experience the negative consequences of globalization after all (e.g., Owen and Johnston 2017). This has two implications for further research. On one hand, researchers should assess globalization-induced economic pressure differently than by simply relying on socio-demographic characteristics, such as a person’s skill level (e.g., Schaffer and Spilker 2019). Instead, it seems essential to quantify the degree of exposure to different forms of globalization. On the other hand, we need to improve our understanding of the role of increased labor market competition caused by an interplay between consequences from different forms of globalization in the opinion formation process (e.g., Peters 2015). It is only possible to assess the full extent of economic pressure a person is exposed to due to globalization if their overall situation is considered.

We believe our paper contributes to the literature in at least two ways. First, we show that it might not be as easy as suggested by the existing literature to refute the labor market competition hypothesis. By showing that high-skilled natives act upon their self-interest once they are exposed to some economic pressure, we find evidence in-line with its main expectation. Second, we emphasize that, contrary to the labor market competition hypothesis’ logic, people need a decisive reason for prioritizing their self-interest when forming opinions on immigration. If the labor market situation of individuals is relaxed, they will not necessarily choose egoistic over sociotropic consideration as their position allows them to maintain altruistic views.

Notes

Some studies also investigate labor market threats by immigrants that are industry-specific (Dancygier and Donnelly 2013; Mayda 2008). In this case, immigrants pose a threat to natives that are employed in those industries, in which a significant number of immigrants are trying to find employment. In comparison to the skill-specific models, however, empirical literature does not prominently discuss sector-specific models.

The countries are: Austria, Belgium, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Great Britain, Hungary, Ireland, Lithuania, the Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland.

The exact wording of the question is: “Please tell me how important you think each of these things should be in deciding whether someone born, brought up and living outside [country] should be able to come and live here. Firstly, how important should it be for them to have good educational qualifications?” A summary statistic that give an overview of respondents’ preference distribution on the issue of high-skilled immigrants are available in the Appendix, Fig. A.1.

While being measured on a scale from 1–10, this variable is strictly seen not interval-scaled. Thus, we show in the robustness section that our results are robust if we either rely on ordered logistic regression models (Table A.2 in the Appendix) or if we transform the original scale into a dummy variable and use multilevel logistic regression analysis (Table A.3 in the Appendix). For the dummy variable, we code answers ranging from 0 to 5 as 0 and values above 5 as 1. We incorporate 5, which is the center of the original scale, into the 0 category because we assume that respondents that chose the center of this scale still think that the education level of an immigrant is rather unimportant than important. The reason for this is that they indicate indifference for the issue by choosing the center of the scale.

The exact wording of the question is: “Please tell me how important you think each of these things should be in deciding whether someone born, brought up and living outside [country] should be able to come and live here. How important should it be for them to have work skills that [country] needs?”. A summary statistic that depicts the distribution of preferences on this issue is depict in Fig. A.1.

Even if our underlying theoretical framework assumes factor mobility, we still rely on the industry of employment to calculate the degree of exposure to immigration because we only cover short term effects in our analysis in which factor mobility is still limited (Mayda 2008). This does not change the fact that the labor competition within sectors is carried out between equally skilled immigrants and natives. This is why the exposure to high and low skilled immigrants consists of an aggregated measure that calculates the percentage of immigrants of one of the two skill levels employed in a certain sector relative to the overall amount of individuals employed in this sector.

We excluded Norway from the analysis because the data quality for this particular country in the European LFS is low especially among immigrants.

We assessed the internal consistency reliability of our nativism measure using Cronbach’s alpha which takes on a value of 0.72. This means our anti-nativism score reports a high internal consistency reliability.

The models used to calculate the marginal effects displayed in Fig. 2 and 3 control for the country context by including country fixed effects and standard errors clustered on the country level.

References

Armstrong, M. 2019. The most important issues facing the U.S. today. https://www.statista.com/chart/10278/the-most-important-issues-facing-the-us-today/. Accessed 11 Sept 2020.

Bansak, K., J. Hainmueller, and D. Hangartner. 2016. How economic, humanitarian, and religious concerns shape European attitudes toward asylum seekers. Science 354 (6309): 217–222.

Brader, T., N.A. Valentino, and E. Suhay. 2008. What triggers public opposition to immigration? Anxiety, group cues, and immigration threat. American Journal of Political Science 52 (4): 959–978.

Coenders, M., M. Lubbers, P. Scheepers, and M. Verkuyten. 2008. More than two decades of changing ethnic attitudes in the Netherlands. Journal of Social Issues 64 (2): 269–285.

Connor, P. and N.G. Ruiz. 2019. Majority of U.S. public supports high-skilled immigration. https://www.pewresearch.org/global/2019/01/22/majority-of-u-s-public-supports-high-skilled-immigration/. Accessed 11 Sept 2020.

Dancygier, R.M., and M.J. Donnelly. 2013. Sectoral economies, economic contexts, and attitudes toward immigration. The Journal of Politics 75 (1): 17–35.

Dancygier, R.M., and S. Walter. 2015. Globalization, labor market risks, and class cleavages. In The politics of advanced capitalism, ed. Pablo Beramendi, Silja Häusermann, Hebert Kitschelt, and Hanspeter Kriesi, 133–156. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Daniller, A. 2019. Americans’ immigration policy priorities: Divisions between–and within—the two parties. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/11/12/americans-immigration-policy-priorities-divisions-between-and-within-the-two-parties/. Accessed 11 Sept 2020.

Dustmann, C., and I.P. Preston. 2007. Racial and economic factors in attitudes to immigration. The BE Journal of Economic Analysis & Policy 7 (1): 1–39.

Ennser-Jedenastik, L. 2018. Welfare chauvinism in populist radical right platforms: The role of redistributive justice principles. Social Policy & Administration 52 (1): 293–314.

ESS. 2019. Download datafile. https://www.europeansocialsurvey.org/download.html?file=ESS7e02_2&y=2014. Accessed 07 June 2019.

Esses, V.M., U. Wagner, C. Wolf, M. Preiser, and C.J. Wilbur. 2006. Perceptions of national identity and attitudes toward immigrants and immigration in Canada and Germany. International Journal of Intercultural Relations 30 (6): 653–669.

Eurobarometer 2022. Standard Eurobarometer 96-Winter 2021-2022. https://europa.eu/eurobarometer/surveys/detail/2553

Facchini, G., and Mayda, A. M. 2009. Does the welfare state affect individual attitudes toward immigrants? Evidence across countries. The review of economics and statistics 91 (2): 295–314.

Goldstein, J.L., and M.E. Peters. 2014. Nativism or economic threat: Attitudes toward immigrants during the great recession. International Interactions 40 (3): 376–401.

Gonzalez-Barrera, A. and P. Connor. 2019. Around the World, more say immigrants are a strength than a burden. https://www.pewresearch.org/global/2019/03/14/around-the-world-more-say-immigrants-are-a-strength-than-a-burden/. Accessed 11 Sept 2020.

Girma, S., D. Greenaway, and K. Wakelin. 2001. Who benefits from foreign direct investment in the UK? Scottish Journal of Political Economy 48 (2): 119–133.

Hainmueller, J., and D. Hangartner. 2013. Who gets a Swiss passport? A natural experiment in immigrant discrimination. American Political Science Review 107 (1): 159–187.

Hainmueller, J., and M.J. Hiscox. 2007. Educated preferences: Explaining attitudes toward immigration in Europe. International Organization 61 (2): 399–442.

Hainmueller, J., and M.J. Hiscox. 2010. Attitudes toward highly skilled and low-skilled immigration: Evidence from a survey experiment. American Political Science Review 104 (1): 61–84.

Hainmueller, J., and D.J. Hopkins. 2015. The hidden American immigration consensus: A conjoint analysis of attitudes toward immigrants. American Journal of Political Science 59 (3): 529–548.

Hainmueller, J., M.J. Hiscox, and Y. Margalit. 2015. Do concerns about labor market competition shape attitudes toward immigration? New evidence. Journal of International Economics 97 (1): 193–207.

Hainmueller, J., J. Mummolo, and Y. Xu. 2019. How much should we trust estimates from multiplicative interaction models? Simple tools to improve empirical practice. Political Analysis 27 (2): 163–192.

Hanson, G.H., Scheve, K. and Slaughter, M.J.2007. Public finance and individual preferences over globalization strategies. Economics & Politics 19(1): 1–33

Harell, A., S. Soroka, S. Iyengar, and N. Valentino. 2012. The impact of economic and cultural cues on support for immigration in Canada and the United States. Canadian Journal of Political Science/revue Canadienne De Science Politique 45 (3): 499–530.

Kaihovaara, A., and Z.J. Im. 2018. Jobs at risk? Task routineness, offshorability, and attitudes toward immigration. European Political Science Review 12: 1–19.

LFS. 2020. European Union Labour Force Survey (EU LFS). https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/microdata/european-union-labour-force-survey. Accessed 15 July 2020.

Malhotra, N., Y. Margalit, and C.H. Mo. 2013. Economic explanations for opposition to immigration: Distinguishing between prevalence and conditional impact. American Journal of Political Science 57 (2): 391–410.

Mayda, A.M. 2008. Why are people more pro-trade than pro-migration? Economics Letters 101 (3): 160–163.

Meuleman, B., E. Davidov, and J. Billiet. 2009. Changing attitudes toward immigration in Europe, 2002–2007: A dynamic group conflict theory approach. Social Science Research 38 (2): 352–365.

Oatley, T. 2015. International political economy. New York: Routledge.

Owen, E., and N.P. Johnston. 2017. Occupation and the political economy of trade: Job routineness, offshorability, and protectionist sentiment. International Organization 71 (4): 665–699.

Owen, E., and S. Walter. 2017. Open economy politics and Brexit: Insights, puzzles, and ways forward. Review of International Political Economy 24 (2): 179–202.

Peters, M.E. 2015. Open trade, closed borders immigration in the era of globalization. World Politics 67 (1): 114–154.

Schaffer, L.M., and G. Spilker. 2019. Self-interest versus sociotropic considerations: An information-based perspective to understanding individuals’ trade preferences. Review of International Political Economy 26 (6): 1266–1292.

Scheve, K.F., and M.J. Slaughter. 2001. Labor market competition and individual preferences over immigration policy. Review of Economics and Statistics 83 (1): 133–145.

Valentino, N.A., et al. 2019. Economic and cultural drivers of immigrant support worldwide. British Journal of Political Science 49 (4): 1201–1226.

Walter, S. 2010. Globalization and the welfare state: Testing the microfoundations of the compensation hypothesis. International Studies Quarterly 54 (2): 403–426.

Wilkes, R., N. Guppy, and L. Farris. 2008. “No thanks, we’re full”: Individual characteristics, national context, and changing attitudes toward immigration. International Migration Review 42 (2): 302–329.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rhein, S., Spilker, G. When winners win, and losers lose: are altruistic views on immigration always affordable?. Int Polit (2022). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41311-022-00389-6

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41311-022-00389-6