Abstract

Democracy festivals are an emerging phenomenon in Northern European democracies. Currently, such festivals are found in 10 different countries, yet they have received virtually no scholarly attention. This article is a first attempt to subject such festivals to systematic study, by means of a survey of event organizers at one of the largest, most longstanding festivals, Norwegian Arendalsuka. A stated goal of Arendalsuka is to give organizations more equal access to decision makers. We analyze whether this ambition is fulfilled by examining whether the festival redistributes, reinforces, or reproduces patterns of access we observe in the rest of the year. We do so through the lens of two perspectives on interest group representation. Resource exchange theory argues that access to different political arenas is determined by how group resources match the demand of the gatekeepers. The cumulative access perspective argues that superior resources override dynamics of resource exchange. We find weak evidence of resource exchange and stronger evidence for cumulative access. With regard to politicians, the festival might reinforce differences compared to the rest of the year. Thus, even though the democracy festival under study actively tries to reduce bias, the dominance of the financially and professionally strongest actors prevails.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In recent years, democracy festivals have emerged as a new arena for contact between organized interests and gatekeepers. Currently, such festivals are found in ten different countries, yet they have received virtually no scholarly attention. The stated goal of democracy festivals, according to their international umbrella organization, is to revitalize democracy by connecting the political system with citizens and their organizations, enhancing dialogue and participation, and ensuring access to core political discussions and actors across resource differences (Buhl et al. 2019). A key rationale behind the festival under study here, Arendalsuka, is to create what its founder referred to as a “dance floor of democracy,” i.e., an arena where all actors participate on equal terms and existing resource-based differences in access to decision makers are levelled.Footnote 1

Thus, democracy festivals potentially represent an antidote to the often-cited problem of biased access to gatekeepers (Baumgartner & Leech 1998; Drutman 2015; Gilens & Page 2014; Schattschneider 1960; Schlozman et al., 2013; Rokkan 1966), by creating a novel and informal arena of contact between organized interests and bureaucrats, politicians, and the media in which access is less contingent upon resources.

The primary purpose of the article is to situate democracy festivals within the study of interest and advocacy group behavior, highlighting the emergence of such festivals as a recent and expanding feature of Northern European culture. We further investigate whether the ambition of reduced bias in access is fulfilled, by comparing access to three different arenas (administrative, political, and media) at Arendalsuka to similar types of access in everyday politics. We do so through the lens of resource exchange and cumulative access theory, responding to a call by Binderkrantz et al. (2015) for more research on these perspectives within different contexts.

After presenting the phenomenon of democracy festivals, we address the following research questions: First, do patterns of access at Arendalsuka conform to expectations based on resource exchange theory, cumulative access theory, neither, or both? Second, does the informal context of a democracy festival redistribute, reinforce, or reproduce the patterns of access to decision makers we observe the rest of the year?

We conceptualize access as a contact at least partly at the discretion of the targeted decision makers (Halpin & Fraussen 2017), producing a result. This may be in the form of expansion of networks that could be useful in the future, agreement on future meetings or media coverage. Thus, access entails something more than merely having spoken to or had a drink with a politician or a bureaucrat. Even though access is no guarantee for influence, we follow the interest group literature in looking at access as a prerequisite for influencing the policy process (Bouwen 2004; Eising 2007; Binderkrantz et al. 2015). The decision makers have the prerogative to refuse further contact. This distinguishes “access” from “involvement,” in which the contact is at the discretion of the group itself (Halpin & Fraussen 2017).

The data stem from quantitative survey of actors organizing at least one event at Arendalsuka in 2018. The theoretical universe of the study is organizations taking part at a democracy festival. Although the most politically relevant lobbyists in Norway are present at the festival, our data are not a representative sample of the larger Norwegian universe of interest groups, nor are it intended to be.

The findings indicate that organizations meet similar challenges with regard to access here as they do in everyday politics. Although an informal atmosphere lowers the threshold of contact, attention is still a scarce resource. The political parties and administrative actors decide which events they would like to participate in and the media chooses what events to cover. They choose whom to promise a meeting after the event or with whom to stay in touch. In this selection process, resourceful actors still enjoy a privileged position. Hence, resources play an important role in explaining success and failure on Arendalsuka, as they do the rest of the year.

We proceed by introducing the phenomenon of democracy festivals in general and Arendalsuka specifically. We then summarize the contrasting perspectives of resource exchange and cumulative access before presenting our data and design. Finally, we present our results and discuss the implications in a concluding section.

Democracy festivals: an emerging, but understudied, phenomenon

Democracy festivals have proliferated rapidly over the past few years. As of 2019, 11 such festivals exist throughout Northern Europe. Their umbrella organization, the International Democracy Festival Association, supported by the Nordic Council of Ministers, now counts eight national festivals as members. In total, the association estimates that the festivals comprise 8,700 events and 150,000 unique participants and are attended by 90 percent of political parties represented in parliaments (Buhl et al., 2019, 5).

The oldest festival is Sweden’s Almedalsveckan, which began with a speech by then Education Minister Olof Palme standing on a truck in 1968. It grew to include participants from all political parties since 1981. According to its organizers, the festival is now “the largest democratic meeting place for anyone wanting to discuss societal issues.”Footnote 2

Since the establishment of Almedalsveckan, the phenomenon has spread to other Nordic countries, manifested in Finland’s Suomiareena (established 2006); Denmark’s Folkemødet (2011); the festival under study here, Arendalsuka (2012); Iceland’s LÝSA festival (2015). Inspired by the Nordic festivals, similar events have been established in Estonia (2013, the Arvamusfestival), Latvia (Lampa, 2015), Lithuania (the Diskusiju Festivalis Bütenti, 2017), and Belgium (the Jubel festival, to be held in 2019). Two additional festivals are not members of the international association: D’ran in the Netherlands (established in 2017) and Democracy Alive, organized by the European Movement (2019).

Although the festivals’ historical origins, scopes, and sizes differ, they share a commitment to be “platforms for democratic dialogue between civil society, politicians, business, media, universities, and people at large.”Footnote 3 The festivals’ stated goal is to “revitalize democracy by strengthening the link between a political system and citizens, as well as creating spaces for dialogue and participation.” The criteria for inclusion in the umbrella organization mandate that each festival must be nationwide, work for participatory democracy and societal benefit, provide free admission and be open to everyone, be based on a participatory-democracy philosophy, provide an informal atmosphere, and focus on conversations and dialogue (Buhl et al., 2019).

Founded in 2012, Arendalsuka’s history is one of the longest among the festivals. The initiative originated from a group of national corporate leaders who established the festival in collaboration with the small town of Arendal (population: 45,000). The municipality owns Arendalsuka and is headed by Arendal’s mayor. It is 70% funded by private sponsors and 30% by the government. The festival lasts six days and takes place in the middle of August. According to Arendalsuka’s own estimates, the festival has approximately 75,000 unique visitors, making it the largest festival in terms of audience (though not number of events).Footnote 4 Our impression from attending Arendalsuka in 2019 and 2020 is that the majority of attendees are policy professionals working for or associated with interest groups, private companies, think tanks, political parties or PR-companies.

In 2017, the program included 791 official events, growing to 1 261 events in 2019. The most frequent topics were health, climate, labor and business, and digitization (Anonymized 2019). The festival is attended by politicians, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), corporate representatives, the media, and ordinary citizens. Political parties play a key role, with each given one hour to present themselves during the festival. All parties represented in parliament attend the festival, including 60 to 70 out of a total of 169 members of parliament and all government ministers. Each party has an in-house Arendalsuka coordinator (Buhl et al. 2019).

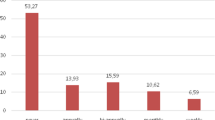

Over time, the festival has grown to become an arena in which most relevant lobbyists within all sectors, as well as politicians, representatives of the bureaucracy and the media, gather in one place. Our data confirm that access to gatekeepers and decision makers, and politicians in particular, is the key motive for the organizations participating at Arendalsuka. In a separate survey carried out before the festival in 2017, 90 percent of event organizers rated networking with politicians and 73 percent networking with the media as an important motivation for participating.Footnote 5 When asked to prioritize the most important motive (Table 1), networking with politicians was the most frequent answer (50 percent). Contact with the general audience was a less frequent motivation. Comparing with the results the participants achieved, as measured in responses after the event, it is clear that these ambitions were not always fulfilled. Significantly fewer (31 percent) rated networking with politicians as the most important outcome, while the goal of competence building within own organization occurred more frequently among results than among expectations. This underlines that the competition is fierce for access to politicians who are often pressed for time running between different events.

The preparation of the program at Arendalsuka follows a set procedure. All types of interest groups and political parties can sign up to arrange events. The events are required to be free of charge, open for everyone and address a socially beneficial topic. If the interest groups want a politician to participate, they have to send an application by 31st of May of that year. The political party coordinators decide which events they prioritize attending. If interest groups want other elite participants from the media, bureaucracy, or other interest groups to attend their events, this is arranged through existing networks. Based on the conversations the authors had with decision makers attending Arendalsuka, the process of prioritizing which events to attend followed typical criteria such as the importance of the other participants, closeness of existing bonds with interest groups, and the chance of gaining media attention.

In addition to the official program, numerous closed, invitation-only events take place. At this “backstage” segment of the festival, the power gradient is arguably much more visible than in the “frontstage” open program. Several of the most powerful groups organize closed, high-budget events offering free drinks, gaining valuable face time with powerful decision makers.

The media presence at Arendalsuka is considerable. All the major newspapers are present with several journalists. The major television outlets, Norwegian Broadcasting Corporation (NRK) and TV2, move their studios and political reporting to Arendal during Arendalsuka. A yearly highlight is the party leader debate, which is broadcast live on NRK on the first day of the festival. A list we obtained from Arendalsuka in 2018 showed that over 300 journalists were accredited for the event. Despite the large number of journalists present, the competition for media coverage during Arendalsuka is intense. Journalists we talked to during Arendalsuka in 2018 told us that they were drowning in sales pitches from interest groups.

In a competitive market like this, in which the attention of the powerful is a scarce resource, it takes conscious effort to avoid the Matthew effect in which those with insider status and superior resources achieve greater results. To counteract this, the festival tries to counteract resource differences by waiving participant fees for event organizers and offering cheaper alternatives for small nonprofit organizations (Buhl et al. 2019, 23). A key organizer, Øystein Djupedal, frequently refers to the festival as “the dance floor of democracy,” implying that all actors from different sectors meet on equal terms.

Despite being a growing international phenomenon attended by hundreds of thousands of people, thousands of NGOs and private sector lobbyists, and almost all political parties, virtually no research has been done on democracy festivals. A Google Scholar search on “democracy festivals” yields zero relevant results. Even the longstanding Almedalsveckan has elicited only a handful of student theses, a Swedish-language working paper (Fredriksson et al. 2018), and a chapter in a Swedish-language book about policy professionals in Swedish (Garsten et al., 2015). This article is an attempt to start filling the gap in our existing knowledge about this emerging phenomenon.

Democracy festivals comprise an interesting laboratory for research, as a large proportion of relevant lobbyists, regardless of sector, is gathered in one place. Lobbyists at Arendalsuka meet many of the same challenges with regard to access as in everyday politics as the attention of top politicians, bureaucrats and the media is a scarce resource. Thus, after presenting the theoretical perspective and our data, we examine empirically whether Arendalsuka succeeds in its ambitious aim of levelling out resource differences in this competitive climate, or whether resourceful insiders prevail even there.

Resource exchange and cumulative access: two perspectives on group access to bureaucrats, politicians, and the media

Binderkrantz et al. (2015) compare two perspectives of access to different arenas. On one hand, the resource exchange perspective states that gatekeepers in the parliamentary system, the bureaucracy, and the media value different resources among organizations (Beyers 2004; Beyers & Kerremans 2007; Braun 2012). On the other hand, the cumulative access perspective states that the same actors are likely to be dominant in several arenas. We briefly review each of these approaches below.

From a resource exchange perspective, interest group access is determined by the resources that different groups bring to the table and how these match gatekeepers’ demand in the bureaucracy, parliament, and the media (Bouwen 2004; Hall & Deardorff 2006; Woll 2007). A key distinction with resource exchange theory is between insider and outsider resources, which provide access to different arenas (Dür & Mateo 2016; Kollman 1998). Groups with ample insider resources possess information and expertise relevant to the policy process, and they exert external control over members. Such organizations feed decision makers with technical information, as well as information about core actors’ political support. Although public interest groups and identity groups may attain insider status under certain circumstances, such resources are particularly prominent among professional organizations, unions, employers’ organizations, and business interests—the quintessential participants in corporatist arrangements (Austen-Smith & Wright 1994; Marsh & Rhodes 1992; Rokkan 1966; Öberg et al. 2011). Thus, there is generally a match between economically oriented groups, decision makers in general, and the bureaucracy in particular—that values insider resources the most.

A different set of organizations may possess ample outsider resources, such as the ability to establish broad social relevance and deliver personalized stories with high news value (Binderkrantz & Krøyer 2012; Kollman 1998). These characteristics are likely to affect access to public arenas. Although, for example, labor unions are frequently able to make successful appeals to social relevance, the ability to raise issues with public appeal is primarily the key strength of public interest and identity groups, whose insider resources are often weaker. Identity groups also possess the ability to capture attention through personalized stories.

On the demand side, the bureaucracy tends to value insider resources, such as technical information and control over members. The media value outsider resources, such as stories with broad appeal or a personalized angle. Politicians (members of parliament) may value both insider and outsider resources. These actors are interested in both expertise and attracting public attention.

Thus, this approach modifies the economic-purpose bias in that groups even outside the economic sector possess resources that powerful gatekeepers value (Binderkrantz et al. 2015). Although the general notion of resource exchange emanates from a corporatist perspective (Bouwen 2002), this version of the theory is compatible with the pluralist notion that access by different types of groups is possible.

Empirically, the resource exchange thesis has received mixed support. Weiler et al. (2019) and Greene and Heberlig (2002) have identified such patterns in their studies of Swiss legislative and administrative venues and US voluntary organizations, respectively. However, Hanegraaff and Berkhout (2019) found no evidence of resource exchange in their study of the EU interest group community, and Binderkrantz et al. (2015) found that both resource exchange and cumulative access are in play.

From the cumulative access perspective, in contrast, the dynamics of resource exchange are overridden by the superior resources that some organized actors possess in the form of finances, employees, or preexisting networks (Binderkrantz et al. 2015). Thus, the same actors are dominant in several arenas, and access primarily is found among wealthy and professionalized groups (Binderkrantz 2005; Eising 2007). Several US scholars have pointed out the importance of financial resources in gaining access to decision makers (Austen-Smith & Wright 1994; Hall & Wayman 1990). This is due to two mechanisms:

First, finances and staff are relevant across arenas. Bigger and more powerful actors are more likely to be heard, as they can spend more time and energy courting gatekeepers, establishing relationships, and preparing documents—and do so in a more professionalized way. Second, spillover effects are at work, in that access to one arena positively influences access to others (Thrall 2006). For example, groups with access to decision makers hold inherently greater news value, groups with ample media coverage are more attractive for politicians to associate with, and groups that capture more attention from politicians are of greater value to bureaucrats anticipating legislators’ reactions (Binderkrantz et al. 2015, 101).

Binderkrantz et al. (2015) find that multiple arenas provide access for multiple interests, but that the unequal distribution of resources produces cumulative effects. They describe this as a system of privileged pluralism, in which all groups participate, but some have privileged access to a distinct set of gatekeepers.

Following Binderkrantz et al. (2015), the predictions regarding resource exchange and cumulative access are the same for business and professional groups: They are expected to be more active, especially vis-á-vis the bureaucracy. Citizen groups and NGOs seeking public, collective goods (public interest groups), and those seeking benefits for limited constituencies, e.g., patients, minority groups (identity groups) are viewed as rich in outsider resources. Thus, following resource exchange theory, they should be well-represented vis-á-vis politicians and the media, but less so in the bureaucracy (Berkhout 2013; Lowery 2007). Finally, institutional groups, i.e., providers of public or semipublic services such as schools and museums, are likely to possess ample insider resources and should have greater access to the administrative arena. The typology is presented in more detail in the following data section. It should be noted that Binderkrantz et al.’s perspective has been developed within a corporatist, Northern European context, to which the case under study belongs, and that the classification of groups may be less appropriate in systems with weaker corporatist arrangements.

Data and methods

The analyses are based on a survey of event organizers conducted after the 2018 festival. The survey contained questions about results from participation, access to decision makers outside Arendalsuka, resources, and several other themes. The survey was conducted in March 2019 by invitation through e-mail. In all, 598 questionnaires were sent out. For this study, 83 organizations were excluded because they were ministries, directorates, or otherwise part of the public bureaucracy; three were political parties; and five were not organizations. In 21 cases, the e-mail did not reach the recipient. This left 486 organizations remaining in the adjusted sample.

182 organizations that fell under this study’s scope responded, yielding a total response rate of 37.4% (Table 2). The rate was lower for private businesses than for other types of groups; therefore, the results from this category should be interpreted with some caution.

Below, we analyze three sets of variables: access to decision makers inside Arendalsuka; access outside Arendalsuka; and resources.

Access at Arendalsuka

Three additive indices measure access to gatekeepers and decision makers at Arendalsuka, one for the administrative arena, one for politicians, and one for the media (see 'Appendix' for question wording).

For the administrative arena, we use an additive index of two items: First, the extent to which networking with the public sector was a result of participation was gauged (using a five-point Likert scale ranging from “to a very small extent” to “to a very large extent”). Second, the frequency of establishing new contacts with the public sector that may be useful in the future was gauged (on a four-point scale: (1) none; (2) once; (3) two to three times; and (4) more than three times).

For politicians, we similarly used measures of whether networking was a result of festival participation and the frequency of establishing new contacts. In addition, we gauged frequency of “agreed on future meetings with politicians” using the same scale as above.

Regarding the media, we included a measure of networking with the media as a result of festival participation, the frequency of establishing contacts with journalists that may be useful in the future, and the frequency of achieving media attention (newspaper, radio, or TV) about issues that the organization wants to raise.Footnote 6

Our measures are adaptations of standard operationalizations of access in the interest groups literature. Meetings with politicians and media coverage are frequently used to measure access to politicians and the media (Binderkrantz et al. 2015). For the administrative arena, group representation in public committees is the most frequently used measure in the literature (Bouwen 2004; Eising 2007; Binderkrantz 2015). As committee participation is not applicable in the context of a democracy festival, we replace it with measures gauging network building.

Access outside Arendalsuka

As noted, the different nature of access at and outside Arendalsuka prevents us from using the exact same measures for both arenas. To gauge access outside Arendalsuka, we constructed additive indices of contact with (a) ministries and (b) directorates for the administrative arena, and (a) cabinet ministers; (b) parliamentary committees; (c) party groups in parliament; and (d) singular members of parliament for politicians. For the media, we used a singular measure of contact frequency with the media and journalists.

For ease of interpretation, all indices used in the analyses were recoded to run from 0 to 100. For cross-tabulations and comparisons of means, the measures of access outside Arendalsuka are split into four categories of fairly equal sizes.

Resources

We use two measures of resources in the analysis: the cost of the organizations’ participation at Arendalsuka and the number of yearly full-time equivalents (FTEs) that the organizations dedicate to political work. The latter was specified to include “contact with the bureaucracy, politicians, and journalists, or work with analyses and evaluations of political processes.” In the cross-tabulations and comparisons of means, these continuous variables are split into four categories of fairly even size. In the regression analyses, we use the logarithmic transformation of the variables to normalize the distribution.

Organization types

Due to a low number of observations in the data, we use a simplified version of the typology presented in Binderkrantz et al. (2015). We combine trade unions, employers’ associations, and professional groups in one category, labeled business and professional groups. Trade unions comprise the highest number of entities in this category.

Identity groups and public interest groups are often analyzed together under the heading of citizen groups (e.g., Berry 1999). We combine these in a category labeled citizen groups/NGOs. Also included in this category is eight “leisure” groups (sports, other leisure interests, religion, and other spiritual interests). These groups are numerous in the Nordic nonprofit sectors (Henriksen et al. 2018), but due to their nonpolitical nature, their attempts to access decision makers (and presence at a democracy festival) are limited.Footnote 7

In order to capture the full range of participants at the festival, we, unlike Binderkrantz’ et al. (2015), included a small number (22) of private companies within the for-profit sector. Their motivation for participation at Arendalsuka may vary, with some looking for political influence, while others view the festival as an arena in which to promote their businesses. Therefore, we do not expect this organizational category to stand out with either greater or lesser access.

Institutional groups are providers of public or semipublic services, e.g., associations of local authorities, schools, museums, and other types of institutions. These organizations also play a prominent role in corporatist arrangements, and they are found both in the public, nonprofit, and for-profit sectors. As institutional groups are expected to be highly active in the administrative arena, we retain this as a separate category in the material.

We exclude participants from the public sector from the analyses, as the contact between these organizations and the bureaucracy and politicians can be viewed as an integral part of their day-to-day operations. Many are targets of lobbying attempts themselves. However, we retained 10 institutional actors within the public sector, comprising mainly hospitals and higher education institutions, as these tend to fight for public funding and attention from the media.

Thus, we analyze four different types of groups: (1) professional organizations; (2) citizen groups/NGOs; (3) private businesses; and (4) institutional groups (both nonprofit, for-profit, and public sector).

In addition to the survey, both researchers participated at Arendalsuka in 2018 and 2019 and talked to both interest groups, politicians, bureaucrats, and media representatives. Some of these observations are included in this article where deemed relevant.

Results

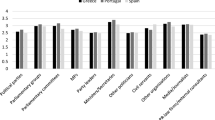

Table 3 compares access inside Arendalsuka and the rest of the year, based on the indices presented in the data section.

Regarding the administrative arena, business and professional groups emerge as the most active outside Arendalsuka. As predicted by resource exchange theory, citizen groups are less active than average in the administrative arena. The same applies to private businesses. At Arendalsuka, in contrast, institutional actors are the most active, while citizen groups again are less active than average. However, business and professional groups are also surprisingly slightly less active than average when it comes to contact in the administrative arena at Arendalsuka, while they are more active the rest of the year. This result may be affected by which parts of the bureaucracy are represented at Arendalsuka. Based on our observations at the festival, it is our impression that some high-ranking bureaucrats, especially within the ministries, are absent. This may make the bureaucracy less attractive as a lobbying target at Arendalsuka.

With regard to networking with politicians, the differences between actor types are somewhat smaller, both inside and outside Arendalsuka. The analysis of activity at Arendalsuka does show significant differences between types, with business and professional groups and institutional groups being the most active. However, the differences are not large, and networking with politicians appears to be distributed fairly evenly between different types of organizations at Arendalsuka.

Regarding the media, business and professional groups and institutional groups are somewhat more active at Arendalsuka. The former type is also more active the rest of the year. We did not find the tendency predicted by resource exchange theory, namely that organizations rich in outsider resources (citizen groups/NGOs) would be more active than average. Both inside and outside Arendalsuka, these organizational types are slightly less active than other organizations.

The analyses with regard to resources show that for politicians and the media, resourceful organizations are more active both inside and outside Arendalsuka. However, strong evidence of resource bias exists, whether measured in resources spent on participation or the number of political employees. The exception is contact with the bureaucracy, in which only budget for participation is significant at the 90% level.

Finally, Table 3 shows the relationship between access outside and inside Arendalsuka. A strong, positive association exists between day-to-day lobbying activity and lobbying at Arendalsuka, implying that those who are insiders the rest of the year also dominate during the democracy festival.

Comparing the effects from purpose and resource bias

So far, we have shown that resources and extensive day-to-day contact with decision makers and gatekeepers are associated positively with access at Arendalsuka, supporting predictions of cumulative access, whereas support for resource exchange theory has been more tenuous. The multivariate analysis addresses two questions: First, what is more important: resources or purposes (Models 1 and 2)? Second, does Arendalsuka reproduce patterns of access, or do effects from purpose and resources occur even when day-to-day contact is taken into account (Model 3)? Table 4 shows a multivariate analysis of access during Arendalsuka using the same indices as those used in Table 3.

Regarding the bureaucracy, we find weak indications of both resource and purpose bias. Citizen groups are underrepresented, and institutional actors are overrepresented. Surprisingly, there is a weak tendency (significant at the 90% level in Model 1) toward an underrepresentation of business and professional groups. This indicates that these groups are less dominant at Arendalsuka than elsewhere with regard to the bureaucracy. Resources play a role, but a limited one. The amount of money spent on participation exerts an effect significant at the 90% level in Model 1, but number of political employees exerts no effect. Model 3 takes into account access during the rest of the year. For the bureaucracy, no significant effect from day-to-day contact exists. The modest effect from amount spent on Arendalsuka in Model 1 is cancelled out; thus, the only significant predictor at the 95% level is an underrepresentation of citizen groups.

Regarding politicians, institutional groups and business and professional groups (only significant in Model 2) are overrepresented. Resources play a greater role than was the case for the bureaucracy. Significant effects were found from both money spent and number of professional employees. These effects are weakened when access during the rest of the year is taken into account, but the effect from money spent on participation remains significant. Generally, access to politicians at Arendalsuka conforms to patterns found during the rest of the year, but with an additional effect from high cost of participation. The combined effects from type, resources, and day-to-day access are stronger in contacts with politicians than for the other two arenas (r2 = 0.25).

When it comes to the media, no evidence of purpose bias exists when resources are taken into account. A strong effect was found from the number of political employees, and a weaker effect from money spent on participation. Professionalization seems to be the key to media access at Arendalsuka, but when activity the rest of the year is included in Model 3, the impact from resources disappears. This indicates that the same resourceful actors dominate both inside and outside Arendalsuka.

Overall, access the rest of the year plays a key role in explaining access at Arendalsuka when it comes to politicians and the media, but not the bureaucracy. The effects from resources and cost of participation are weakened when taking into account that resourceful actors are also more active in day-to-day lobbying activity, but for contact with politicians, a significant effect from money spent remains. Thus, the pattern is different for the three arenas: Resources play a limited role in access to the bureaucracy at Arendalsuka, contact patterns the rest of the year are reproduced for the media, and inherent resource differences in access are somewhat reinforced regarding contact with politicians.

Conclusion

The present study has highlighted democracy festivals as an emerging feature in Northern European political culture. As such festivals grow and proliferate in an increasing number of countries, it is clear that they are relevant to the study of interest groups and advocacy. A large number of organizations across sectors participate, and networking, especially directed toward politicians, is a key motivation for attending. Almost all participants (91% in our survey) are in contact with politicians during Arendalsuka, and two-thirds try to influence politicians.

So far, however, this phenomenon has passed under the research radar—virtually no published studies exist. The present study is a first attempt to start filling this gap, by describing the purpose and characteristics of the festivals and analyzing the patterns of access to decision makers and gatekeepers at the largest festival in terms of visitors, Norwegian Arendalsuka.

The explicit aim of democracy festivals is to redistribute differences in access to decision makers. Measures are taken to ensure greater access for smaller and less resourceful participants in terms of economy and insider connections. If this were the case, it would represent a major democratic innovation. In the analyses above, therefore, we have examined the extent to which this ambition is fulfilled. The general pattern in our results suggests that resource contingent differences in access are reproduced or, in the case of politicians, even reinforced, compared to day-to-day access to power.

Our theoretical point of departure was two approaches to the study of interest group access: Resource exchange, in which access is determined by a match between gatekeeper demands and the resources that different types of actors bring to the table, and cumulative access, in which superior resources and insider status override this exchange.

The results provide some support for the resource exchange thesis. In accordance with resource exchange dynamics, institutional actors were more active vis-á-vis the bureaucracy at Arendalsuka, whereas citizen groups/NGOs were less active. However, we did not find the anticipated overrepresentation of professional groups in this arena. One interpretation of this anomalous finding could be that while top-ranking politicians and journalists are present at Arendalsuka, core parts of the bureaucracy, especially ministries, are present less frequently and, thus, are less attractive to lobbyists. With regard to networking with politicians, professional groups and institutional actors were the most active. In the media arena, contrary to expectations, organizations rich in “outsider” resources, i.e., citizen groups, were not overrepresented. Instead, even this arena was dominated by business and professional groups and institutional actors.

Support for the cumulative access perspective was more robust. The resources spent on Arendalsuka and the number of employees were associated with extensive networking and access inside and outside Arendalsuka, regarding politicians and the media. The exception was contact with the bureaucracy, in which the impact from resources was weaker.

In the multivariate analyses of media access, resource bias was cancelled out when measures of access outside Arendalsuka were included in the analysis. However, for politicians, the story was different: A significant, albeit weakened, relationship was found between measures of resources and networking (amount of money spent on participation) at Arendalsuka, even when organizational type and day-to-day access were accounted for.

Thus, while resources exerted no additional effect on access to the bureaucracy (no effect from resources when controlling for type) and the media (reproduction of resource differences in access elsewhere), we found some evidence of reinforcement of resource differences on access to politicians. Even when controlling for the fact that those who are most resourceful generally have much greater access, we still found that the strongest actors more frequently succeeded in establishing connections at Arendalsuka—relations that are likely to ease access the rest of the year and ultimately yield political rewards.

In summary, organizations rich in insider resources and economic resources dominate at Arendalsuka, while ample outsider resources generally do not improve access. This runs counter to organizers’ ambitions to redistribute such differences and raises the question of whether democracy festivals, to some extent, may in fact exacerbate resource biases. It is possible that the informal and friendly atmosphere that a festival fosters rewards insiders even more than more formalized contexts do.

If we see lobbying as a relationship market, resourceful organizations are likely to have more employees with broad, politically relevant networks stemming from their past political experience (i Vidal et al. 2012; LaPira & Thomas 2014). Professional lobbyists spend extensive resources cultivating such informal networks (Groll & McKinley 2015; Susman 2008). They are likely to be highly useful at Arendalsuka, where informal contexts such as dinners, receptions, or hanging out in pubs are important venues for meeting politicians. In our conversations with participants, they frequently describe Arendalsuka as a way to reunite with old friends. Consequently, existing networks belonging to powerful actors might be strengthened and expanded, while less resourceful actors lose on the informal relationship market as they do in more formal settings.

If democracy festivals are to reach their ambition of reducing bias in access to decision makers, they need to engage in more effective redistributive policies than just waiving fees for events and subsidizing accommodation for smaller organizations. One example could be guidelines for political parties demanding that a certain percentage of the events in which they agree to participate should be organized by less resourceful groups. In an unregulated, “free market of events,” the resourceful are likely to prevail.

The present study has some limitations. First, the low number of observations in different types of organizations may have led to an imprecise estimation of the presence of resource exchanges. Second, the study is based on the organizations’ self-reported success measures, and organizations may tend to inflate their results, especially if they have spent substantial amounts of money on participation. However, previous research indicates that self-reported measures of lobbying results correlate well with documentary sources and that there is no systematic tendency towards some groups being more dishonest than others (McKay, 2012; Pedersen, 2013; Tallberg et al., 2015). Third, the results stem from only one of the 11 democracy festivals established in Northern Europe and, thus, need to be repeated in other countries to draw conclusions about festivals’ contributions to democracy in general. Finally, the survey includes only those participating at Arendalsuka; thus, a downward bias may exist in the estimation of reinforcement of resource and purpose bias if the least-resourceful actors of certain types refrained from even attending. We make no claim of generalizing our findings beyond organizations participating at a democracy festival, i.e., to the entire lobbying universe.

A democracy festival’s context does provide access to politicians to some organizations that are not active lobbyists the rest of the year. However, in the bigger picture, it seems that despite organizers’ intentions to create a “dance floor of democracy,” establishing democracy festivals is no panacea against resource biases in access. Resourceful organizations with insider status dominate at Arendalsuka, just as they do the rest of the year, perhaps even more so. Even in a highly egalitarian country, at a festival actively trying to reduce bias, the financially and professionally strongest actors’ dominance is confirmed.

Notes

https://www.aftenposten.no/meninger/kommentar/i/kB109/Lobbyistenes-festuke--Ola-Storeng, accessed May 20, 2019.

http://www.almedalsveckan.info/hur_fungerar_almedalsveckan, accessed May 20, 2019.

Quotes from https://democracyfestivals.org/, accessed May 20, 2019.

https://arendalsuka.no/6240. The Swedish Almedalsveckan has the highest number of events (4000 official and 2000 unofficial), but a lower estimate of the number of visitors (40 000) (Buhl et al. 2019).

n = 219, response rate 50%. More information about the survey (in Norwegian): https://polkom.org/home/2018/8/14/hvem-vinner-og-taper-p-arendalsuka.

It could conceivably affect results that we used slightly different measures for the three sectors. As a robustness check, we reran the analyses using only the items that were the same for the bureaucracy, politicians, and the media (establishing new contacts and networking as a result of the participation), excluding media attention and agreement on future meetings. This did not significantly alter the results.

Inclusion of these groups as citizen groups may create a downward bias in the estimate of access to decision makers in this category. In order to check for this, we also carried out all the analyses reported below with leisure groups excluded. This altered none of the results.

References

Anonymized. 2019. “Dagsorden og innflytelse på Norges største demokratifestival [Agenda setting and influence at Norway’s largest democracy festival]. Oslo: POLKOM-Report.

Austen-Smith, D., and J.R. Wright. 1994. Counteractive lobbying. American Journal of Political Science 38 (1): 25–44.

Baumgartner, F.R., and B.L. Leech. 1998. Basic Interests: Importance of Groups in Politics and in Political Science. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Berkhout, J. 2013. Why interest organizations do what they do: Assessing the explanatory potential of ‘exchange’ approaches. Interest Groups & Advocacy 2 (2): 227–250.

Berry, J.M. 1999. The New Liberalism: Rising Power of Citizen Groups. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Beyers, J. 2004. Voice and access: Political practices of European interest associations. European Union Politics 5 (2): 211–240.

Beyers, J., and B. Kerremans. 2007. Critical resource dependencies and the Europeanization of domestic interest groups. Journal of European Public Policy 14 (3): 460–481.

Binderkrantz, A.S. 2005. Interest group strategies: Navigating between privileged access and strategies of pressure. Political Studies 53 (4): 694–715.

Binderkrantz, A.S., and S. Krøyer. 2012. Customizing strategy: Policy goals and interest group strategies. Interest Groups & Advocacy 1 (1): 115–138.

Binderkrantz, A.S., P.M. Christiansen, and H.H.J.G. Pedersen. 2015. Interest group access to the bureaucracy, parliament, and the media. Governance 28 (1): 95–112.

Bouwen, P. 2002. Corporate lobbying in the European Union: The logic of access. Journal of European Public Policy 9 (3): 365–390.

Bouwen, P. 2004. Exchanging access goods for access: A comparative study of business lobbying in the European Union institutions. European Journal of Political Research 43 (3): 337–369.

Braun, C. 2012. The captive or the broker? Explaining public agency–interest group interactions. Governance 25 (2): 291–314.

Buhl, A., Elvang, Z., Wolff, M. 2019. Democracy Festival: Introduction. Retrieved from https://democracyfestivals.org/

Drutman, L. 2015. The Business of America Is Lobbying: How Corporations Became Politicized and Politics Became More Corporate. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Dür, A., and G. Mateo. 2016. Insiders Vs. Outsiders: Interest Group Politics in Multilevel Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Eising, R. 2007. Institutional context, organizational resources, and strategic choices: Explaining interest group access in the European Union. European Union Politics 8 (3): 329–362.

Fredriksson, M., D. Lövgren, and J. Pallas. 2018. Bortom uppdraget: En analys av svenska myndigheters kommunikationsaktiviteter under Almedalsveckan. Göteborg: Institutionen för journalistik, medier och kommunikation, Göteborgs universitet.

Garsten, C., B. Rothstein, and S. Svallfors. 2015. Makt utan mandat: de policyprofessionella i svensk politik. Stockholm: Dialogos förlag.

Gilens, M., and B.I. Page. 2014. Testing theories of American politics: Elites, interest groups, and average citizens. Perspectives on Politics 12 (3): 564–581.

Greene, S., and E.S. Heberlig. 2002. Finding the weak link: The choice of institutional venues by interest groups. American Review of Politics 23: 19–38.

Groll, T., and M. McKinley. 2015. Modern Lobbying: A Relationship Market. Cesifo DICE Report 13 (3): 15–22.

Hall, R.L., and A.V. Deardorff. 2006. Lobbying as legislative subsidy. American Political Science Review 100 (1): 69–84.

Hall, R.L., and F.W. Wayman. 1990. Buying time: Moneyed interests and the mobilization of bias in congressional committees. American Political Science Review 84 (3): 797–820.

Halpin, D., and B. Fraussen. 2017. Conceptualising the policy engagement of interest groups: Involvement, access and prominence. European Journal of Political Research 56 (3): 723–732.

Hanegraaff, M., and J. Berkhout. 2019. More business as usual? Explaining business bias across issues and institutions in the European Union. Journal of European Public Policy 26 (6): 843–862.

Henriksen, L.S., K. Strømsnes, and L. Svedberg, eds. 2018. Civic Engagement in Scandinavia: Volunteering, Informal Help, and Giving in Denmark, Norway, and Sweden. New York: Springer.

Kollman, K. 1998. Outside Lobbying: Public Opinion and Interest Group Strategies. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

LaPira, T.M., and H.F. Thomas. 2014. Revolving door lobbyists and interest representation. Interest Groups and Advocacy 3 (1): 4–29.

Lowery, D. 2007. Why do organized interests lobby? A multi-goal, multi-context theory of lobbying. Polity 39 (1): 29–54.

Marsh, D., and R.A.W. Rhodes. 1992. Policy Networks in British Government. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

McKay, A. 2012. Buying policy? The effects of lobbyists’ resources on their policy success. Political Research Quarterly 65: 908–923.

Öberg, P., T. Svensson, P.M. Christiansen, A.S. Nørgaard, H. Rommetvedt, and G. Thesen. 2011. Disrupted exchange and declining corporatism: Government authority and interest group capability in Scandinavia. Government and Opposition 46 (3): 365–391.

Pedersen, H.H. 2013. Is measuring interest group influence a mission impossible? The case of interest group influence in the Danish parliament. Interest Groups & Advocacy 2: 27–47.

Rokkan, S. 1966. Numerical democracy and corporate pluralism. In Political Oppositions in Western Democracies, ed. R.A. Dahl. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Schattschneider, E.E. 1960. The Semisovereign People: A Realist’s View of Democracy in America. New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston.

Schlozman, K.L., S. Verba, and H.E. Brady. 2013. The Unheavenly Chorus: Unequal Political Voice and the Broken Promise of American Democracy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Susman, T.M. 2008. Private ethics, public conduct: An essay on ethical lobbying, campaign contributions, reciprocity, and the public good. Stanford Law and Policy Review 19: 10.

Tallberg, J., L.M. Dellmuth, H. Agné, and A.K. Duit. 2015. NGO influence in international organizations: Information, access, and exchange. British Journal of Political Science 48: 213–238.

Thrall, T.A. 2006. The myth of the outside strategy: Mass media news coverage of interest groups. Political Communication 23 (4): 407–420.

Vidal, I.J.B., M. Draca, and C. Fons-Rosen. 2012. Revolving door lobbyists. The American Economic Review 102 (7): 3731–3748.

Weiler, F., S. Eichenberger, A. Mach, and F. Varone. 2019. More equal than others: Assessing economic and citizen groups’ access across policymaking venues. Governance 32 (2): 277–293.

Woll, C. 2007. Leading the dance? Power and political resources of business lobbyists. Journal of Public Policy 27 (1): 57–78.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

On behalf of both authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix

Items measuring access at Arendalsuka

Access administrative arena: (To what extent did the organization achieve the following at Arendalsuka?) Build networks with the public sector “to a very large extent” (5)/ “to a very small extent” (1).

(How many times did you achieve the following): Established contacts with representatives of the public sector that may be useful in the future. (1) Zero, (2) Once, (3) 2–3 times, (4) more than 3 times.

Access politicians: (To what extent did the organization achieve the following at Arendalsuka?) Build networks with politicians “to a very large extent” (5)/ “to a very small extent” (1).

(How many times did you achieve the following): Established contacts with politicians that may be useful in the future. (1) Zero, (2) Once, (3) 2–3 times, (4) more than 3 times.

Agreement on future meeting with politicians. (1) Zero, (2) Once, (3) 2–3 times, (4) more than 3 times.

Access media: (To what extent did the organization achieve the following at Arendalsuka?) Build networks with the media “to a very large extent” (5)/ “to a very small extent” (1).

(How many times did you achieve the following): Established contacts with journalists that may be useful in the future. (1) Zero, (2) Once, (3) 2–3 times, (4) more than 3 times.

Media coverage (newspaper, radio, TV) about case (s) the organization is concerned with. (1) Zero, (2) Once, (3) 2–3 times, (4) more than 3 times.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wollebæk, D., Raknes, K. Interest group access to decision makers at a democracy festival. Int Groups Adv 11, 333–352 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41309-021-00150-z

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41309-021-00150-z