Abstract

Our paper analyzes the role of public employment agencies in job matching, in particular the effects of the restructuring of the Federal Employment Agency in Germany (Hartz III labor market reform) for aggregate matching and unemployment. Based on two microeconomic datasets, we show that the market share of the Federal Employment Agency as job intermediary declined after the Hartz reforms. We propose a macroeconomic model of the labor market with a private and a public search channel and fit the model to various dimensions of the data. We show that direct intermediation activities of the Federal Employment Agency did not contribute to the decline in unemployment in Germany. By contrast, improved activation of unemployed workers reduced unemployed by 0.8 percentage points. Through the lens of an aggregate matching function, more activation is associated with a larger matching efficiency.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Our model shows important similarities to Pissarides (1979) setup. However, there are also important differences. Workers’ search decisions are not sequential in the data (i.e., using both channels at the same time is possible). We do not have fixed wages and can thereby analyze the implications of benefit shifts on wage bargaining outcomes. Moreover, we analyze the dynamic adjustment path of our labor market in response to business cycle shocks.

See “Appendix 1” for further institutional information and details on the other reform steps.

The size of the partial effect is supported by microeconometric evidence by Price (2018).

We also show results for the matching share based on the IAB Vacancy Survey in the Appendix. Both sources yield very similar developments over time.

See Appendix “Data” for details on the chosen baseline observation period and the calculation of vacancy and matching shares.

In Table 10, it can be seen that we also find no evidence that the matching share increased for individuals with a loose connection to the labor market.

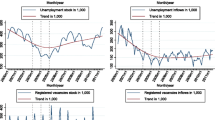

In time series regressions, in contrast to the time trend, the permanent downward shift of the matching share in the aftermath of the Hartz reforms is always statistically significant at the 1% level (for the short and long time series as well as for West Germany and for Germany as a whole).

This survey is only available from 1998 onward. We do not use the SOEP, as search behavior was only asked for a limited number of years and the relevant question changed over time.

For the derivations in this section, we postulate that \(\nu _t\) is a function of \(g_t\) of the type \(\nu _t =x_t g_t\) where \(x_t\) is not yet determined and that \(o_t\) does not depend on \(g_t\). Both will be verified later.

In a prior version of this paper, we assumed a different wage formation that lead to the same wage for all workers. In this case, we had to choose a rule for the share of private and agency matches. All our key results are unaffected by this assumption.

These are treated alike as new private matches and existing matches earn the same wage.

Thereby, we assume that the agency also sanctioned before the reforms. However, much less so than after the Hartz III reform. This assumption is chosen in order to be able to assign double matches to one of the two channels before the reform.

\(\tau ^{u}\) corresponds to the reported vacancies divided by the number of unemployed.

Since we do not have the share of privately searching unemployed for the full-time period, we cannot estimate the private elasticity.

The two elasticities are estimated by regressing the corresponding job-finding rate on the relevant market tightness. The job-finding rate of the agency is constructed by multiplying the aggregate job-finding rate with the matching share of the agency. The stated values for the elasticities are estimated with robust standard errors. They are significant on the 1% (\(\alpha\)) and 5% (\(\alpha _a^{m}\)) level, where \(\alpha\) is the estimated aggregated coefficient. \(\alpha _a^{m}\) is the estimated coefficient for the agency.

In contrast to Coe and Snower (1997), we do not have policy complementarities. See Appendix for a different sequencing of reforms.

For comparability, we use the definition of tightness as vacancies over unemployed.

Compared to studies that estimate aggregate matching efficiency, this increase appears moderate. This is due to the observation period, which is longer in our case than in existing matching function estimations for Germany (Fahr and Sunde 2009; Hertweck and Sigrist 2013; Klinger and Rothe 2012; Stops 2016).

For expositional convenience, we use the splitting equilibrium rules for double matches from Sect. 4.5 throughout the Appendix.

References

Abbring, J.H., G.J. van den Berg, and J.C. van Ours. 2005. The effect of unemployment insurance sanctions on the transition rate from unemployment to employment. The Economic Journal 115(505): 602–630.

Bossler, M., H. Gartner, A. Kubis, and B. Küfner. 2020a. The IAB job vacancy survey: establishment survey on labour demand and recruitment processes, waves 2000 to 2017 and subsequent quarters 2006 to 2018, FDZ-Datenreport 06/2020, Nuremberg.

Bossler, M., N. Gürtzgen, A. Kubis, B. Küfner, and B. Lochner. 2020b. The IAB job vacancy survey: design and research potential. Journal for Labour Market Research 54(1): 1–12.

Bossler, M., N. Gürtzgen, A. Kubis, and A. Moczall. 2018. IAB-Stellenerhebung von 1992 bis 2017: So wenige Arbeitslose pro offene Stelle wie nie in den vergangenen 25 Jahren, IAB-Kurzbericht 23/2018, Nuremberg.

Cacciatore, M., R. Duval, G. Fiori, and F. Ghironi. 2016. Market reforms in the time of imbalance. Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control 72: 69–93.

Cacciatore, M., and G. Fiori. 2016. The macroeconomic effects of goods and labor market deregulation. Review of Economic Dynamics 20: 1–24.

Carrillo-Tudela, C., A. Launov, and J.-M. Robin. 2021. The fall in German unemployment: a flow analysis. European Economic Review 132: 103658.

Coe, D.T., and D.J. Snower. 1997. Policy complementarities: the case for fundamental labor market reform. Staff Papers (International Monetary Fund) 44(1): 1–35.

Duval, R., and D. Furceri. 2018. The effects of labor and product market reforms: the role of macroeconomic conditions and policies. IMF Economic Review 66(1): 31–69.

Eichhorst, W., M. Braga, A. Broughton, A. de Coen, H. Culot, F. Dorssemont, U. Famira-Mühlberger, M. Gerard, U. Huemer, M. J. Kendzia, J. L. Pedersen, and E. Slezak. 2013. The role and activities of employment agencies, IZA Research Report 57.

Fahr, R., and U. Sunde. 2009. Did the Hartz reforms speed-up the matching process? A macro-evaluation using empirical matching functions. German Economic Review 3(10): 284–316.

Fair, R.C., and J.B. Taylor. 1983. Solution and maximum likelihood estimation of dynamic nonlinear rational expectations models. Econometrica 51(4): 1169–1185.

Federal Employment Agency. 2020. Arbeitslosigkeit im Zeitverlauf: Entwicklung der Arbeitslosenquote (Strukturmerkmale).

Federal Employment Agency. 2023. Sanktionen (Zeitreihe Monats- und Jahreszahlen ab 2007).

Franz, W. 2013. Arbeitsmarktökonomik, 8. aktualisierte und ergänzte Auflage, Springer Gabler.

Gartner, H., C. Merkl, and T. Rothe. 2012. Sclerosis and large volatilities: two sides of the same coin. Economics Letters 117: 106–109.

Gartner, H., T. Rothe, and E. Weber. 2019. The quality-weighted matching function: did the German labour market reforms trade off efficiency against job quality? IAB Discussion Paper 24/2019.

Gehrke, B., W. Lechthaler, and C. Merkl. 2019. The German labor market during the great recession: shocks and institutions. Economic Modelling 78: 192–208.

Goebel, J., M.M. Grabka, S. Liebig, M. Kroh, D. Richter, C. Schröder, and J. Schupp. 2019. The German socio-economic panel (SOEP). Jahrbücher für Nationalökonomie und Statistik 239(2): 345–360.

Hainmueller, J., B. Hofmann, G. Krug, and K. Wolf. 2016. Do lower caseloads improve the performance of public employment services? New evidence from German employment offices. The Scandinavian Journal of Economics 118: 941–974.

Hamjediers, M., P. Schmelzer, and T. Wolfram. 2018. Do-files for working with SOEP Spell Data, SOEP Survey Papers 492, Berlin.

Hartung, B., P. Jung, and M. Kuhn, 2022. Unemployment insurance reforms and labor market dynamics, mimeo.

Hertweck, M. S., and O. Sigrist. 2013. The aggregate effects of the Hartz reforms in Germany, SOEPpapers on Multidisciplinary Panel Data Research 532.

Hochmuth, B., B. Kohlbrecher, C. Merkl, and H. Gartner. 2021. Hartz IV and the decline of German unemployment: a macroeconomic evaluation. Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control 127: 104114.

Holzner, C., and M. Watanabe. 2020. Intermediation Services and Search Friction, mimeo.

Holzner, C., and M. Watanabe. 2021. The wage effect of vacancy referrals from the public employment agency, mimeo.

Hutter, C., F. Carbonero, S. Klinger, C. Trenkler, and E. Weber. 2022. Which factors were behind Germany’s labour market upswing? A data-driven approach. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics 84(5): 1052–1076.

IMF. 2015. “Chapter 3. Where are we headed? Perspectives on potential Output” in World Economic Outlook, April 2015. International Monetary Fund, Washington, DC.

Jacobi, L., and J. Kluve. 2007. Before and after the Hartz reforms: The performance of active labor market policy in Germany. Journal for Labour Market Research 40(1): 45–64.

Klein, M., and S. Schiman. 2022. What accounts for the German labor market miracle? A structural VAR approach. Macroeconomic Dynamics 1–32.

Klinger, S., and T. Rothe. 2012. The impact of labour market reforms and economic performance on the matching of the short-term and the long-term unemployed. Scottish Journal of Political Economy 59(1): 90–114.

Klinger, S., and E. Weber. 2016. Decomposing Beveridge curve dynamics by correlated unobserved components. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics 78(6): 877–894.

Kohlbrecher, B., C. Merkl, and D. Nordmeier. 2016. Revisiting the matching function. Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control 69: 350–374.

Krause, M.U., and H. Uhlig. 2012. Transitions in the German labor market: structure and crisis. Journal of Monetary Economics 59(1): 64–79.

Krebs, T., and M. Scheffel. 2013. Macroeconomic evaluation of labor market reform in Germany. IMF Economic Review 61(4): 664–701.

Lalive, R., J.C. van Ours, and J. Zweimüller. 2005. The effect of benefit sanctions on the duration of unemployment. Journal of the European Economic Association 3(6): 1386–1417.

Launov, A., and K. Wälde. 2013. Estimating incentive and welfare effects of nonstationary unemployment benefits. International Economic Review 54(4): 1159–1198.

Launov, A., and K. Wälde. 2016. The employment effect of reforming a public employment agency. European Economic Review 84: 140–164. European Labor Market Issues.

Lochner, B., C. Merkl, H. Stüber, and N. Gürtzgen. 2020. Recruiting intensity and hiring practices: cross-sectional and time-series evidence. Labour Economics 68: 101939.

Pissarides, C. 1979. Job matchings with state employment agencies and random search. Economic Journal 89(356): 818–33.

Pissarides, C.A. 2000. Equilibrium unemployment theory, 2nd ed. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Price, B. 2018. The duration and wage effects of long-term unemployment benefits: evidence from Germany’s Hartz IV reform. UC Davis, mimeo.

Schiprowski, A. 2020. The role of caseworkers in unemployment insurance: evidence from unplanned absences. Journal of Labor Economics 38(4): 1189–1225.

SOEP. 2019. Socio-Economic Panel (SOEP). Data for years 1984–2018, SOEP-Core, v35. https://doi.org/10.5684/soep-core.v35.

Stops, M. 2016. Revisiting German labour market reform effects-a panel data analysis for occupational labour markets. IZA Journal of European Labor Studies 5(1): 1–43.

Svarer, M. 2011. The effect of sanctions on exit from unemployment: evidence from Denmark. Economica 78(312): 751–778.

vom Berge, P., A. Burghardt, and S. Trenkle. 2013. Sample of integrated labour market biographies: Regional File 1975-2010 (SIAB-R 7510), IAB-Datenreport 09/2013, Nuremberg.

Funding

Funding was provided by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (Grant No. ME-3887/5-1).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

We are grateful to Hermann Gartner and Alexander Kubis for providing data on job vacancies in Germany. We would like to thank Anja Bauer, Hermann Gartner, Brigitte Hochmuth, Michael Stops, Heiko Stüber, Klaus Wälde, as well as participants at the European Economic Association, the Verein für Socialpolitik, the Austrian Economic Association, 13th IAAEU Workshop on Labour Economics, the internal IAB seminar, and the 11th ifo Conference on Macroeconomics and Survey Data, the BGPE Research Workshop, the 13th interdisciplinary Ph.D. workshop "Perspectives on (Un-)Employment," the final international conference of the DFG Priority Program 1764 and the 26th Spring Meeting of Young Economists for valuable feedback. We would like to thank Christian Holzner for discussing our paper at the Bavarian Macro Workshop. We thank the German Research Foundation for funding (Grant Number: ME-3887/5-1).

Appendices

Appendix 1: Details on Hartz Reforms

1.1 Different Reform Steps

The so-called Hartz commission (named after the head of the commission, Peter Hartz) developed recommendations how to reform the German labor market in order to reduce unemployment. The guiding principle for these reforms was “Fordern und Fördern,” the so-called principle of “rights and duties” (see Jacobi and Kluve 2007). These recommendations were implemented gradually, starting in 2003. See Hochmuth et al. (2021) or Launov and Wälde (2016) for a more detailed description:

Hartz I (implemented in 2003): The first package of the Hartz reform facilitated temporary work contracts. In addition, it introduced vouchers for training.

Hartz II (implemented in 2003): The second package introduced new types of marginal employment, with reduced social security contributions for low-income contracts. In addition, it introduced subsidies for unemployed workers to transition into self-employment.

Hartz III [implementation, started in 2004, the full roll-out ended in late 2005, see Holzner and Watanabe (2021) for details]: The core element of Hartz III was the restructuring of the Federal Employment Agency (see Launov and Wälde 2016 for details). With the introduction of Hartz III, all claims of an unemployed person were processed by the same case worker (support from a single source) and an upper limit on the number of cases handled by one single case worker was introduced. In addition, market elements for private placement services and providers of training measures were introduced.

Hartz IV (implemented in 2005 and 2006): The last step of the Hartz reforms changed the unemployment benefit system for the long-term unemployed. Before Hartz IV, long-term unemployed received benefits that were dependent on their prior net earnings. With the introduction of Hartz IV, long-term unemployed had to go through a strict means test and received a fixed transfer (independent of their prior income). See Hochmuth et al. (2021) for details.

1.2 Activation and Counseling

As part of the Hartz III reform, the Federal Employment Agency offered new services to unemployed workers, such as advising and counseling. In addition, individuals that were not placed by the PEA within six weeks received subsidies for a private placement service [see Jacobi and Kluve (2007) for institutional details, in particular, their Sect. 3. Furthermore, the Hartz reform introduced new sanctions to monitor unemployed workers’ job search activities.

We are not able to differentiate these measures in our macroeconomic matching exercise. However, all of them have in common that they stimulate private search activities of unemployed workers. In our numerical, exercise we show that activation and counseling policies play an important role to explain the macroeconomic patterns after the Hartz reforms.

Appendix 2: Model Derivations

This Appendix shows the detailed model derivations. As in the main part, we start with the household optimization, followed by the firm optimization and the derivation of wages.Footnote 21

1.1 Household

Each unemployed worker has to make the decision whether to search privately herself or to rely only on the agency to find a job. For this decision, the probabilities of finding a job in both cases are important. If no private search is carried out, the probability of being employed in the next period is \(p_t^{a}\). The worker himself cannot get in contact with two vacancies since he only searches through one channel. The worker can get in a situation, where he gets in contact with a vacancy which has a second contact from the private search market. Since firms always choose the agency contact if they have a double match this does not reduce the matching probability of a worker who only searches via the agency.

If a worker uses the private search market his probability of making a match through the private market is:

If a worker gets in contact with a vacancy through the private market and this vacancy made a second contact through the public search channel, the worker will not be matched since firms prefer agency contacts. The probability that the worker himself makes two contacts (one through each search channel) is not subtracted here since workers prefer private contacts over agency contacts. The worker’s probability of being matched through the agency thus has to be reduced to \(p_t^{a} -p_t^{a} p_t^{a}\).

With these probabilities we can define the value of only searching through the agency as

and the value of using both channels as

The worker will only use both channels if the value from doing so is higher than the value of searching through the agency only.

The worker with the highest individual search cost who is still searching through the private market is indifferent between searching privately and not searching privately. Thus, for this worker equation (47) holds with equality. Using equations (45) and (46), we can derive the cutoff search costs:

Using

we obtain equation (11) stated in the main text:

Every job seeker who draws a value of \(e_{it}\le \tilde{e}_t\) uses the private market. Thus the share of privately searching job seekers is

The conditioned expected value of search costs is

1.2 Firm

The probability of matching with a worker through the private search market is

The probability of matching with a worker through the public search market is

The representative firm solves the following maximization problem:

subject to the constraints:

The corresponding Lagrangian is:

The first-order conditions are:

Substituting into first-order condition for \(v_t\):

Substituting back into first-order conditions for \(g_t\):

Plug into the FOCs for \(m_t^{a}\) and \(n_t^{p}\):

1.3 Wage Bargaining

A worker’s expected value of a match via the private market is:

\(U_{t}^{p}\) is the average value of being unemployed after having used the private market:

A worker’s expected value of a match via the employment agency:

\(U_{t}^{a}\) is the average value of being unemployed after having used the agency only (and not the private market):

A firm’s value of a matched job depends on whether the match was established via the private market \(J_{t}^{p}\) or the agency \(J_{t}^{a}\):

The Nash bargaining problem can be written as for workers that matched via the agency:

which results in the following sharing rule:

Equivalently, the Nash bargaining problem for workers that matched via the private market is:

which results in the following sharing rule:

The term on the right-hand side includes

for the private wage and

for the agency wage. The two terms can be written in a compact way using the definition of the variable \(V_{t+1}\)

such that

and

Combining these expressions with sharing rules (73) and (75) as well as firms’ values (71) and (70) we get the wage equations stated in the main text

Appendix 3: Details on Bargaining

Figure 8 shows the model assumptions and implications on the out-of-equilibrium outcomes for bargaining. Workers receive a lower starting wage if they are matched via the public employment agency than via the private channel.

Appendix 4: Robustness of Numerical Results

1.1 Reform Complementarities or Substitutabilities

In addition to the effect of one reform step as the only change (Table 5), we calculate the effect of each reform step if it was the last change to happen (Table 8). To do this, we simulate the model with all three reform steps, remove one reform step and then calculate the respective difference for the three outcome variables. It can be seen that this reduces the unemployment effects for sanctions and the surplus shock. This can at least partly be explained by nonlinearities in the model resulting from the cost shock distribution. Although the cutoff point for search costs moves by a similar amount for the exercises in Tables 5 and 8, the additional number of workers who use the private channel increases by less if the other exercise is in place. With a larger share of private searchers, the cutoff point moves into a thinner part of the idiosyncratic distribution.

1.2 Homogeneous Labor Market

As a second exercise, we look at a version of the model with only one search channel which we interpret as the agency. We then check if the results based on this version of the model are comparable to the results of Launov and Wälde (2016) if we follow their methodology in simplified manner. If we restrict workers to search via the public agency only, there is no second private search market. In different words, the Federal Employment Agency is the only intermediary/matching function in the economy. The model equations are:

In this homogeneous model, we have to redesign our calibration exercise, as targeting the vacancy share and matching is not possible (by definition, they are equal to 100%). Note that we replicate the parametrization from the main part.

We follow Launov and Wälde (2016)’s numerical strategy in simplified fashion (as our homogeneous model is less complex than theirs, e.g., in terms of unemployment durations). We take the increase of the matching efficiency from our reduced-form matching function in Table 11, namely 7%. We impose this increase in the matching efficiency on our model. This exercise yields a decline in unemployment of 0.65 pp (see Table 9). This number is comparable to Launov and Wälde (2016) who find a 0.88 pp decline (see their Table 2). In a second step, we use the 7% benefit reduction for long-term unemployed from Launov and Wälde (2016). To simulate this in our model, we multiply this change by 0.36 which corresponds to the average share of long-term unemployed in West Germany in the years from 1998 to 2003 (Hochmuth et al. 2021; vom Berge et al. 2013). The result is a reduction of the unemployment rate by 0.11 pp which is comparable to the results of Launov and Wälde (2016) who find a 0.08 pp decline (see their Tables 2, 9).

Appendix 5: Data and Further Empirical Facts

1.1 Data

1.1.1 German Socio-Economic Panel

As stated before, we construct the matching share of the agency from the German Socioeconomic Panel (SOEP). We also use it to get our target for the share of privately searching unemployed. The SOEP is a longitudinal survey covering approximately 30,000 individuals. For further descriptions of the SOEP, see Goebel et al. (2019). Since we use wave 35, we have observations from the starting year of the SOEP 1984 up to the year 2018. However, due to variations in the questionnaires, the time period of the data used is restricted depending on the variable constructed from the SOEP. For our calibration, we use observations from individuals living in West Germany.

The basis for the share of privately searching unemployed is the question whether a non-employed individual has been actively searching for employment in the last four weeks. To stay close to the model, we only use individuals registered as unemployed at the agency. Since the question whether an active search is being carried out includes the search via the employment agency as active search, a further adjustment is necessary. For the years 2003-2007, additional information is available on the channels through which employment is searched for. For these years, the share of actively searching, registered unemployed who are not only searching through the agency is calculated using the cross-sectional individual weights. The corresponding value for West Germany for the year 2003 is the stated target.

For the matching share, we use the question how an individual found out about her new position. This question is only answered by individuals who started their current employment in the year of the questionnaire or in the year before. The construction of the time series shown in Sect. 3 and used as a target in Sect. 5 takes into account the possibility that the employment started in the year before the questionnaire. In addition, we exclude individuals who claim to have become self-employed, who have changed jobs in the same firm, and who have stated multiple channels. We also add job centers to the agency and exclude personnel service agencies. Finally, we also count individuals who found their job with the help of a voucher from the agency to the matches of the agency. The survey also contains the question what type of occupational change occurred. Based on this question, we again exclude individuals who change their job in a firm and individuals who switch to self-employment as well as individuals for whom this information is missing. We also exclude apprenticeship positions, individuals who are employed in a sheltered workshop, 1 Euro jobs, and public job creation schemes (ABM) positions as well as returnees from parental leave for all years with the respective information. Finally, employees older than 65 are excluded. Based on these adjustments we calculate the matching share of the agency using the cross-sectional individual weights. Not all necessary questions were asked before the time period considered in the main text. That is why the corresponding adjustments were not possible in the longer time series in Fig. 4. The time series in Fig. 11 is based on the same adjustments. Additionally, information from the SOEP spell data is used to obtain the information in which month unemployment spells end. For this, the do-files by Hamjediers et al. (2018) are used. The shown times series is the matching share if an unemployment spell ended in the month in which the new position started or one month before.

1.1.2 IAB Job Vacancy Survey

The data we use for the vacancy share, for the additional time series of the matching share, and for vacancies come from the IAB Job Vacancy Survey (Bossler et al. 2020a, b). The Job Vacancy Survey is a repeated cross section. It was carried out for the first time in the year 1989 and covers up to around 14,000 establishments.

The vacancy share is based on the question how many vacancies an establishment has. In parallel, it is asked how many of these have been reported to the agency. The ratio of the two, each weighted by the weighting factors, gives the vacancy share. In addition, more detailed questions are asked on the last successful hire. Two of these questions are, which search channels were used, and which of those led to the hiring. The latter is the question used for the Job Vacancy Survey time series on the matching share. From 2004 onward, the agency’s internet services are listed as a separate response option in the questionnaire. We add the matches resulting from this option to the matches of the agency. The share of hires for which the agency was stated as the recruitment channel is the matching share. The corresponding weighting factors have been used. When we construct qualification groups, the group university includes degrees from universities and universities of applied sciences.

We use the number of vacancies from the Job Vacancy Survey for our target of the public labor market tightness. The number of unemployed as well as the job finding rates is from the Integrated Labour Market Biographies (vom Berge et al. 2013). For more details see Appendix B in Hochmuth et al. (2021).

1.1.3 Baseline Sample

Data from the IAB Job Vacancy Survey for West and East Germany is only available from 1992 onward. In addition, one key question for the construction of the matching share (on the job transition type, see Appendix “Data”) in the SOEP was rephrased in 1994. Because of the backward-looking nature of the underlying questions and the relatively large sample size in these years, we start calculating the matching share from 1993. Given these two restrictions, we chose the time period from 1993 to 2018 as our baseline. In addition, we do robustness checks based on a long sample from 1985 to 2018. Technically, it is possible to calculate the matching share also for the year 1984 since a share of respondents refers to positions started in the year 1984 when they are surveyed in the year 1985. Because of the small number of observations resulting from this, we chose to start the long time series in 1985, the first year in which the questions necessary were asked.

1.2 Vacancy and Matching Share: Robustness

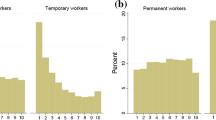

Figure 9 shows the matching share for different education requirements for Germany and West Germany. This figure suffers from a small number of micro-observations per aggregate data point and is therefore somewhat more noisy that the aggregated figures. However, it is visible that the matching share (within certain groups) peaks in times of high unemployment.

Figure 10 shows the matching share based on the Job Vacancy Survey. Although the level of this matching share is somewhat larger, the dynamics is very similar to the SOEP-based matching share.

Figure 11 and Table 10 show further robustness checks with alternative definitions. The key patterns in the data are very robust.

Matching Share: Ending Unemployment Spell. Note: The figure shows the matching share based on all observations in blue and the matching share that is restricted to observation where an unemployment spell ended in the month of the match or the month before in red. Both time series are normalized to a mean of one. On average the restricted matching share was roughly 5 percentage points lower for Germany and 2.5 percentage points lower for West Germany in the post-reform period. (Colour figure online)

1.3 Matching Function Estimations

Table 11 shows matching function estimations with shift dummies for the Hartz III reform. The left column shows a standard matching function estimation, based on the aggregate job-finding rate and market tightness. The right column shows the estimation for a public matching, based on agency matches and agency market tightness. While there is a positive and statistically significant coefficient on the aggregate shift dummy, the estimated coefficient is negative and not statistically significant for the agency.

1.4 Probability of Being Matched via the PEA

Table 12 shows how the individual-level probability of being matched via the agency shifted after the reforms (Hartz III dummy). It controls for aggregate and individual-level observables. The estimations are based on individual-level data from SOEP.

In line with our descriptive evidence from the main part, the probability of being matched via the agency drops in the aftermath of the Hartz reforms. Thus, this fact is robust to controlling for individual-level characteristics.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.