Abstract

Attempts to expand the availability of higher education frequently come with exorbitant expenses, heightening the gap between privileged and underprivileged students. Distributing scholarships to the higher education sub-sector is commonly seen as a viable means of promoting educational success, expanding accessibility, and addressing equity issues in higher education. Nevertheless, the problem of equity remains a long-lasting and unfair obstacle in Cambodia's higher education sub-sector, despite the presence of a national scholarship policy. This is based on the straightforward fact that there is no fundamental metric to evaluate the inclusion and equity of scholarship distribution. Moreover, the scholarship selection procedures may be inefficient, contrary to what policy documents indicate, resulting in students from lower-income households being left behind in the opportunities they were promised. Therefore, this study is the first ever attempt to profile Cambodian higher education scholarships from a socio-economic viewpoint that discusses how family background impacts the likelihood of students from low-income households accessing social investments, such as scholarships. All analyses point out that opportunities are heavily skewed toward students with better-off background, and therefore incorporating this understanding will help Cambodian universities better allocate scholarships to boost the country’s human capital and improve university representation from lower economically-secure communities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The field of higher education is undergoing rapid and unprecedented growth, driven by increasing student enrollment and coupled with significant socio-economic transformations. These changes are further influenced by domestic political shifts and global development initiatives, notably those articulated in the 2015 Incheon Declaration, necessitating policy adjustments within the sector (Teixeira & Landoni, 2017). This expansion aligns closely with UNESCO’s Sustainable Development Goal 4 (SDG 4), which emphasizes inclusive and equitable quality education. Specifically, SDG 4 Target 4.b underscores the distribution of scholarships as a pivotal strategy to enhance global access to higher education, thereby promoting educational attainment and addressing equity issues within the sector (Krafft & Alawode, 2018; World Bank, 2012).

In 2014, Cambodia's Ministry of Education, Youth, and Sport (MoEYS) emphasizes the necessity of a comprehensive scholarship initiative in its Higher Education Vision 2030 (MoEYS, 2014). The 2030 vision is rooted in Sub-Decree No.174, ratified by the Royal Government of Cambodia (RGC), which mandates tuition-waiver scholarships and subsistence allowances for high school graduates entering university (Leth & Heang, 2011). This policy aims to incentivize outstanding students and those with exceptional abilities from disadvantaged economic backgrounds to pursue university-level education as it categorizes students into four groups: outstanding students, orphaned students, Indigenous students, and low-income students. Moreover, it strategically positions the higher education sub-sector to adapt to new development stages in both global and regional contexts. More importantly, this policy responds to Cambodia's increasing demand for university-level education and reflects the impact of macro-economic policies on the nation's education system. It has been molded by global development strategies and Cambodia's transition toward an Industry 4.0 and knowledge-based economy (ADB, 2011; CDRI & CADT, 2021; Chea, 2019; Kao, 2020).

Despite the implementation of a national scholarship policy, equity remains a persistent and significant challenge in Cambodia's higher education sub-sector. This issue arises from the high costs associated with obtaining a university degree and the limited availability of tuition-waiver scholarships for high school graduates pursuing higher education (Chea, 2019; Mak et al., 2019). Additionally, issues in the scholarship selection procedures have added another layer of challenge faced by students from economically disadvantaged households (Chea, 2018; Leth & Heang, 2011). For instance, better-off students often misrepresent their economic status during the scholarship application process, exploiting the absence of an effective financial need verification mechanism. This leads to inclusion and exclusion errors in the scholarship selection process (Leth & Heang, 2011). Furthermore, the MoEYS has faced challenges to encourage students from provinces and underrepresented groups to apply for scholarships, contributing to the inequity (World Bank, 2017). Consequently, this results in heightening the probability of students, particularly those with socio-economically disadvantaged background, forsaking their academic endeavors because the shared expense of high-priced higher education is an enormous cost that can jeopardize economically disadvantaged students' future by negatively affecting their wage potential and employment prospects due to reduced productivity (Heckman et al., 2006; Lin et al., 2018).

Although research on student financing in Cambodian higher education is increasing, there remains a scarcity of studies specifically examining scholarships within this context. For instance, a landscape analysis by Mak et al. (2019) primarily investigates the effective methods and outcomes associated with higher education financing in various Southeast Asian nations, aiming to integrate adaptation strategies suitable for Cambodia's specific circumstances. Additionally, empirical studies by Chea (2019), Chea et al. (2022a, b), Kao (2020), and UNDP (2019) address student financial aids and scholarship funding. However, these aforementioned studies predominantly focus on scholarships targeted at Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (STEM) disciplines, limiting the broader understanding of scholarship dynamics across other fields, more specifically from the lens of socio-economic status.

Given the significant obstacle of financial constraints and the limited availability of higher education opportunities, this study represents the first attempt to profile Cambodian higher education scholarships from a socio-economic viewpoint, exploring how family background impacts the likelihood of students from low-income households accessing social investments such as scholarships. The study begins by utilizing principal component analysis (PCA) to generate a singular family wealth index from 35 variables derived from the household questionnaire of the Cambodia Socio-Economic Survey (CSES) 2019–2020 and set those falling within the 25th percentile as poor students. Subsequently, a high-dimensional fixed effect (HDFE) regression is estimated to address the overarching question: For students from low-income families, how much does their socio-economic status affect their probability of receiving scholarship? To ensure robustness and address heterogeneity, the study includes interaction terms to examine the effects of household dynamics and the intergenerational transmission of education on the likelihood of receiving a scholarship. The results have significant implications for scholarly discourse on financing higher education and for policymaking efforts aimed at expanding existing scholarship selection methods and schemes to better meet the needs of the masses.

Literature Review

Numerous governments have implemented various policies to provide financial assistance to students, aiming to overcome obstacles that hinder those from economically disadvantaged backgrounds from pursuing higher education and to motivate students who exhibit exceptional academic performance (Marcucci, 2016). This approach is especially prevalent among governments in capitalist societies, which justify the expansion of education by emphasizing its significance in fostering globally competitive economies and addressing issues such as poverty, unemployment, and social inequalities. This rationale echoes in the fundamental premise of Human Capital Theory (HCT). According to prominent human capital theorists Becker (1964) and Schultz (1961), who base their perspectives on the neoclassical economic school of thought, individuals are assumed to be rational actors with the ultimate goal of maximizing utility. They posit that individuals are willing to bear the high costs of education and continue their investment up to a point where the difference in expected value of lifetime utility between attending and not attending in the university is equal to or lower than zero. However, an alternative perspective contends that in the absence of government policies and deliberate actions, education remains inadequately funded and consequently incapable of providing the requisite human capital to make a lasting impact on a nation's socio-economic development (Chea et al., 2022b; Lindahl & Canton, 2007).

Simply put, the likelihood of a student and their family, particularly those from lower-income households, investing in higher education decreases due to high costs resulting from insufficient financial assistance distribution and higher tuition fees (ADB, 2011; Farrell & Kienzl, 2009; Friedman, 2017; Liu et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2013). Financial constraints often deter these students from enrolling in universities unless they receive state-sponsored scholarships. Consequently, government financing mechanisms and investments should be directed toward expanding equal opportunities and addressing income disparities to foster economic development. Need-based grants can be an effective means of providing educational opportunities at universities for students who lack the financial capacity to cover significant portions of their university costs.

Implementing a need-based financial system ensures that students from the lowest consumption quintiles receive adequate financial assistance to pursue their degree programs (Krafft & Alawode, 2018; Smolentseva, 2020). This approach is beneficial as it serves the masses, catering to the majority of students rather than a select few from the elite class. A practical example of this system is observed in Thailand, where students with an annual household income of less than $4300 are eligible for need-based funding (World Bank, 2012). Beyond Thailand, socio-economic background has been supported by global empirical evidence in promoting need-based scholarships. For example, research, such as studies by Alon (2011) and Wang et al. (2013), consistently demonstrates that students within the lowest consumption quintile receive more financial assistance than their affluent counterparts and exhibit a higher likelihood of graduating. This highlights the effectiveness of need-based financial aid in enhancing educational access and success for economically disadvantaged students.

When the distribution of need-based scholarships in higher education is disaggregated by gender and major choices, the results reveal a significant bias toward female students, particularly those majoring in STEM disciplines and residing in underrepresented areas (Kao et al., 2023; Navarra-Madsen et al., 2010; Sweeder et al., 2021). This trend corresponds to global initiatives aimed at reducing economic disparities between male and female and addressing the impact of parental biases on occupational choices, especially where conventional views regard STEM professions as male-dominated (Morley & Lugg, 2009; UNESCO, 2015). Such initiatives are essential in promoting gender equity and encouraging more women to pursue careers in STEM, thereby contributing to a more diverse and inclusive workforce.

In addition to need-based financial assistance, universities operate within two distinct markets under the dual-track fee policy. In one market, universities compete for students with exceptional academic performance through state subsidies, while in the other, they compete for non-tuition-free places regardless of academic performance, thereby generating additional revenue (Marcucci, 2016; Smolentseva, 2020). The government-sponsored track prioritizes students who are academically excellent and specialize in less mainstream fields of study, with admission restricted to individuals who achieve the highest scores on standardized national tests (Silva et al., 2020). As numerous research studies have reported, academic performance during high school is a critical factor in determining eligibility for merit-based scholarships (Cohn et al., 2004; Heller, 2016; Sjoquist & Winters, 2015). Cohn et al. (2004) assert that the foremost determinant for university admission and qualification for merit-based scholarships is the grade point average (GPA). Similar studies by Heller (2016) and Sjoquist & Winters (2015) employed regression techniques to derive estimates and found that, upon removing high school achievement variables such as GPA and standardized test scores from the equation, the results became statistically insignificant. This suggests that high school achievement is a suitable criterion for merit-based scholarships and may enhance the likelihood of students completing their university degrees.

However, it has been argued that raising the merit requirement threshold may lead to the exclusion of economically disadvantaged students from prestigious public or private institutions and STEM-related fields. Studies by Baker & Finn (2008), Minaya et al. (2022), Wang et al. (2013), and Wilson et al. (2012) reveal that students from disadvantaged socio-economic backgrounds can gain admission to prestigious universities and receive adequate financial aid to pursue degrees in science-related fields, provided their upper-secondary education test scores meet the admission criteria. Conversely, this system tends to disproportionately benefit students majoring in science and enrolling in top or second-tier universities, limiting its capacity to produce significant differences in educational access and equity. Consequently, while merit-based scholarships can enhance opportunities for some, they may unintentionally reinforce existing disparities.

Study Context

In 2008, the Cambodian government, through MoEYS, initiated the Special Priority Scholarship (SPS) program as part of the Higher Education Quality and Capacity Improvement Project (HEQCIP), funded by the World Bank. Unlike conventional scholarships, the SPS is specifically tailored to meet the needs of students from low-income households, providing tuition waivers and subsistence allowances ranging from $50 for rural students to $70 for students in Phnom Penh. The program yielded promising outcomes, reducing the dropout rate among the targeted demographic from 48 to 15.5% (Chea, 2018). However, following the project's conclusion, the government struggled to sustain the scholarship program due to resource limitations, hindering its ability to expand its scope or maintain operations (World Bank, 2018).

Chet (2009) and UNESCO (2020) indicate that government subsidies allocated to the higher education sub-sector predominantly cover recurrent expenditures, such as staff remuneration and utilities, resulting in limited or no funds available for development purposes; consequently, a significant proportion of scholarships cannot be financed. As a result of the higher education privatization,Footnote 1 the primary sources of providing scholarships depend entirely on the collective contribution from both public and private universities. A small portion of resources originate from their respective fee-paying programs is subsequently transferred to the MoEYS to establish the current Need- and Merit-based National Scholarship Schemes. The total funding received by the participating universities in the national scholarship schemes is utilized to calculate the allocation of tuition-waiver scholarships annually. Through the allocation of funds from the universities, the government is capable of granting scholarships for undergraduate studies to approximately 15% of the overall student population, assuming an annual intake of 40,000–50,000 students.

For example, the cross-tabulation table presented in Table 1 is the outcome of disaggregating data based on discipline, financial source type, and gender. Among undergraduates, 27% were enrolled in STEM-related programs, including 12.80% in agriculture, 19.70% in fundamental science, 25.50% in engineering, 15.90% in health, and 26.10% in information technology. The remaining 74% of students choose non-STEM majors, with 52% opting for business. Significant gender disparities in scholarship awards within the science sector were evident, as female students receive 18.2% more scholarship compared to their male counterparts, who receive only 13.5%. Specifically, the number of female students majoring in information technology and engineering is almost double the number of male students. Female students make up 27.1% of information technology majors and 16.10% of engineering majors. Although the percentage of women receiving basic science scholarships is somewhat lower than that of men (13.40% vs. 14.20%, respectively), women studying in agriculture have about 14% better chances of receiving scholarships. Despite a notable disparity in participation between the science and non-science streams, scholarships predominantly favor the science stream, and female students are given priority in all fields of study.

Regarding scholarship selection, the guidelines clearly state that 60% of scholarships are allocated based on merit (i.e., higher academic performance), while the remaining 40% are designated for specific categories such as female, disadvantaged students, students with an ethnic background, and students with disabilities. The application period for both merit-based and need-based scholarships begins in April. Grade 12 students must choose one scholarship scheme to apply for and submit applications to their three preferred universities. The percentile rank of the aggregate test score from the high school diploma, along with the corresponding grade (ranging from A to F), is the sole determinant of eligibility for merit-based scholarships at public and private universities in Cambodia. In 2011, the priority scholarship application process was replaced with a poverty questionnaire consisting of 29 inquiries. Eligibility for need-based scholarships is determined by evaluating candidates' poverty scores, which are calculated by testing their responses against an algorithm code (Chea, 2018, 2019; Kao, 2020; Leth & Heang, 2011).

Data Setting

Sampling

This research utilizes nationally representative cross-sectional data from the Cambodia Development Resource Institute's (CDRI) Higher Education Student Survey 2020 (CDRI, 2020). The primary objective of this survey is to assess technological readiness during the swift adoption of online learning amid the COVID-19 disruption, with a strong focus on students’ socio-economic status. The survey includes detailed information on students' basic demographics (such as gender, age, and place of birth), current economic activities, educational background, sources of financing, training, access to and use of ICT facilities and services, household background, and experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, the analysis in this study only draws on a small subset of the relevant variables (detailed in Table 2). CDRI utilizes a two-stage sampling strategy to select a nationally representative sample. The sampling frame is constructed using the MoEYS list of universities and higher education enrollment figures (MoEYS, 2020). The sampling process begins with selecting multiple universities using stratified random sampling with probability proportional to size. However, universities with 500 or fewer students and provincial campuses are excluded from CDRI’s sampling frame. In the second stage, cluster sampling is used to select classes as the primary sampling units (PSU). This involves formally requesting access to student records, including names, gender, degree, major, and contact information from participating universities, of the selected classes from sampled universities to start data collection. Simple random sampling with equal probability is then applied in this stage, resulting in a dataset of 1338 undergraduates from various Cambodian universities and TVET institutes. Due to highly fragmented financing mechanisms, this study focuses primarily on samples from universities under MoEYS jurisdiction; however, at the outset, students from TVET institutes are also included in the entire sampled respondents. Excluding those attending TVET institutes, 1158 undergraduate students from 18 universities in the nation's capital and the provinces remain for the estimates.

Measuring Students’ Socio-Economic Status

The main variable of interest in this study is students’ socio-economic status (SES), which mathematically assesses the resourcefulness within individual students' households. Various methods have been proposed in academic literature to measure students' household wealth, one of which is evaluating household consumption (Chea, 2019). However, disaggregating household consumption into several levels has proven to be practically questionable due to the low reliability of selecting a consistent base form for statistical estimation, with different bases producing varying effects. Fortunately, this study employs an instrument comprising 35 items, where participants provide binary responses (0 for No and 1 for Yes) regarding their household’s durable assets. These 35-item questions are derived from the household questionnaire of the Cambodia Socio-Economic Survey (CSES) 2019–2020. Principal component analysis (PCA), a data reduction technique, is utilized to generate a singular family wealth index from these 35 variables. PCA is preferred over including all 35 variables in the regression model to derive a composite score for an individual's family wealth index. This approach involves computing composite scores for individual variables, which are then aggregated to construct the socio-economic status for the entire sample of 1158 undergraduate students. Although using this composite metric may mask many important dimensions of family wealth, compressing 35 items into a single metric offers computational convenience and has demonstrated significant benefits. Importantly, the first principal component score enables this investigation to account for a greater proportion of variance in the model compared to alternative component scores and methods. After analyzing the socio-economic status of the entire group of 1158 undergraduate students, the study defines students from poor households as those falling within the 25th percentile of the family wealth index.

Summary Statistics

The descriptive statistics from Table 2’s Panel A demonstrate significant disparities in scholarship opportunities. Students from non-poor households exhibit a notably higher likelihood of receiving scholarships, with a difference of approximately 0.094. This trend persists across both merit-based and need-based scholarships, showing disparities of 0.031 and 0.082, respectively. These differences are both substantial and statistically significant at the 5% and 1% levels, underscoring a significant gap in scholarship access between students from non-poor and poor households.

Moreover, parents of students from poor households generally attain higher levels of educational achievement. Additionally, Students from poor households typically have fewer siblings compared to their non-poor counterparts, with a notable difference of 0.182.

Age and gender composition are nearly evenly distributed in Panel C, with slight differences that do not reach statistical significance. Notably, disparities in the selection of academic tracks in high school are statistically significant at the 99% level. The scholarship allocation process may be influenced by high school academic performance, particularly overall and mathematics grades, which serve as predictors for scholarship attainment. Students from economically disadvantaged backgrounds are shown to have had significantly higher mean scores in both categories, with statistical significance at the 5% and 1% levels, respectively.

The choice of a STEM major at the university does not significantly influence the likelihood of receiving a scholarship, as it is only statistically significant at the 10% level. Additionally, the observed disparity appears to be influenced by enrollment patterns in high schools and universities within Phnom Penh, including private universities, as shown in Panel D. However, these initial comparisons do not account for potential confounding variables. The subsequent section will present a regression model that addresses these confounders and offers a more comprehensive analysis of the outcomes.

Econometric Modeling

This study employs high-dimensional fixed effect (HDFE) regression to assess the impact of students' socio-economic status on the likelihood of receiving a tuition-waiver scholarship for higher education. This technique is frequently utilized to control for entity-specific effects when dealing with a large number of entities, such as individuals, firms, or countries (Guimarães & Portugal, 2010). The advantage of this method lies in its robustness to outliers; it incorporates dummy variables that capture group-specific heterogeneity, thus accounting for all intragroup variability and time-invariant differences across universities. Consequently, the inclusion of fixed effects addresses concerns about clustering by absorbing common shocks, leading to zero correlation within clusters for the remaining errors.

The analysis is conducted using three distinct models to evaluate the two scholarship schemes available for application by high school graduates. The All-Scholarship model provides a comprehensive estimation, encompassing students who reported receiving scholarships for their undergraduate studies. Additionally, the analyses are further disaggregated into two specific models: Merit Scholarship and Need Scholarship. High school achievement, measured on a scale from A to E (with A indicating the highest achievement), is a critical determinant used to estimate the probability of students receiving merit-based scholarships. For the need-based scholarship model, eligibility is restricted to students from lower-income households, as the sampled respondents do not identify as belonging to a specific ethnic background or having a disability.

In the estimation regressions, students who are awarded a partial scholarship are treated as if they were fee-paying students. The justification for this approach lies in the fact that these students still bear a significant financial burden in covering a substantial part of their tuition fees. Furthermore, the lack of comprehensive information on the various types of scholarships available and the corresponding percentages of tuition fee reduction further offer substantiation to this argument. Moreover, in the absence of government policy influence, the provision of partial scholarships is typically driven by the marketing strategies of individual universities. Hence, the baseline analytical framework can be reformulated as an econometric specification in the following Equation (1):

The dependent variable, denoted as \({y}_{ij}\), represents the scholarship recipient status of student i studying at university j. The socio-economic status, denoted as Poorij, represents the measurement of household family wealth derived from the reported family durable assets of the student who fell inside the 25th percentile of the socio-economic status index. The variable \({ff}_{ij}\) encompasses a vector that represents the educational attainment of parents and the household with 5 siblings based on the average size reported in CSES 2019–2020. \({if}_{ij}\) refers to personal characteristics, including age, students; high school achievement, and dummy variables indicating whether student i is female or pursuing a science major at the university j. The vector \({gef}_{ij}\) represents the relevant variables associated with the location of high schools, with Phnom Penh being assigned a value of 1. The Equation (1) incorporates an error term, denoted as \(\varepsilon_{ij}\), which serves to account for unobserved variables. The regression model specified in Equation (1) presented above incorporates the university fixed effect ( \({\gamma }_{u}\)) as a means of accounting for variations in the number of scholarships contributed to the scholarship schemes and the size of the university.

The above model investigates the impact of students’ socio-economic status on the predicted probability of being awarded a scholarship to attend university. It is worth stressing that \({\beta }_{1}\) is the main coefficient of interest. Several controlled variables are also included into the regression model. The study also utilizes Equation (2) to assess the effects of heterogeneity by including interaction terms involving important household characteristics, such as parental education with a higher education degree and having more than 5 siblings. In order to assess the robustness of the main investigation, the study establishes a stringent criterion for students from poor households to go up by 50th percentiles within the sample. Stata statistical software is used to perform data processing, cleaning, and analysis.

Further, the study analyses the observed determinants \({X}_{i}\) contributing to the opportunity gap in scholarship between non-poor and poor students through the application of Oaxaca-Blinder decompositionFootnote 2 (Blinder, 1973).

Results and Discussion

Holding controlled variables constant and without incorporating university fixed effects, students from poor households are less likely to receive scholarships compared to students from non-poor households, as illustrated in Table 3. The coefficient magnitude is −8.6 percentage points, with statistical significance at p < 0.01. With the inclusion of other covariates and to partial out the effects university in Model (2), enabling for a comparison of non-poor and poor students while taking into account any variations across universities, Model (2) remains consistent, with no significant changes in the coefficient magnitude, although model fit improves slightly (R2 increases from 1 to 19%). This trend persists in Model (3) and Model (4). Although need-based scholarships are intended for students from economically disadvantaged backgrounds, students from more non-poor households have a higher chance of enrolling in university and consequently a greater probability of benefiting from such scholarships. Both merit and need models are statistically significant at 10%. These results indicate that scholarship outcomes are significantly influenced by socio-economic status.

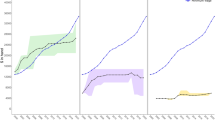

To further examine the issue from a gender perspective, Fig. 1 provides a graphical representation of the predicted probability of scholarship outcomes by students’ socio-economic status and gender. The socio-economic status of students is divided into five quintiles (Q1 Lowest to Q5 Highest), indicating household wealth. In this analysis, the gender and students’ wealth quintiles variables are predicted at their mean values. The data shows that female students have higher predicted probabilities of receiving scholarships across all three estimation models, consistent with findings from Navarra-Madsen et al. (2010) and Sweeder et al. (2021). These findings suggest that Cambodia's scholarship distribution mechanism aligns with global efforts to address gender disparities. However, claims that Cambodia is making substantial progress in inclusiveness are overstated. Students from the two lowest quintiles, regardless of gender, continue to lag behind and are less likely to benefit from scholarships. This disparity has serious implications for access equity at the university level, necessitating the need for more effective policies to support economically disadvantaged students.

As described in the methodology section, a revised definition has been established to categorize students from economically disadvantaged households, shifting the threshold up to the 50th percentile to capture both near-poor and poor samples. This adjustment ensures robustness in the analysis. Table 4 displays the outcomes of re-estimating Equation (1) in Models (1)–(4), incorporating interaction terms with dummy variables to examine heterogeneity in the main study. These interactions include parental education and households with more than five members. The coefficient of \({\beta }_{1}\), the main coefficient of interest, confirms that the main analysis is robust. It shows that students from poor households continue to lag behind in scholarship opportunities compared to non-poor students. From these results, significant equity issues have been pointed out, revealing numerous barriers that hinder low-income students from taking advantage of scholarship programs designed to help them pursue higher education. Despite the Cambodian government's financial framework prioritizing students from socio-economically disadvantaged backgrounds, consistent with global studies (Alon, 2011; Krafft & Alawode, 2018; Smolentseva, 2020; Wang et al., 2013), this study finds the opposite to be true. Research by Leth and Heang (2011) and Chea (2019) explains these discrepancies. After high school, students from non-poor families in Cambodia are more likely to continue their education at the university level and thereby have a higher predicted probability of obtaining scholarships for higher education. This is primarily because students from low-income families face significant obstacles in affording higher education, and a free, 12-year public school education may not be sufficient to guarantee a seamless transition from upper-secondary school to university. Moreover, the scholarship schemes only cover tuition fees, leaving subsistence costs as a substantial financial burden. Consequently, students from low-income backgrounds may hesitate to apply due to the additional financial burden. Additionally, students who are unaware of prospective scholarships may overestimate the cost of education and opt not to further their studies (World Bank, 2017).

Besides, it is evident that parental education yields a strong and positive coefficient magnitude and level of statistical significance, except Model (4), on the likelihood of receiving scholarship. Students who receive scholarship, particularly merit-based scholarships, are already seen as high achievers but having parents with a high level of education can boost their confidence, prepare them for network and opportunities, and inspire them to reach even greater heights in the classroom (Glick, 2008; Wang et al., 2013). However, upon examining the coefficient of the interaction terms, it becomes obvious that even when students have parents with higher levels of education, the likelihood of students from poor households receiving scholarships continues to decrease. This suggests that the intergenerational transmission of education may not be a significant factor in explaining the advantage that poor students have in terms of scholarship opportunities. Students are granted autonomy to make academic decisions. This is particularly evident in Cambodia, where parental involvement in their children’s higher education remains relatively low, especially among socio-economically disadvantaged families. This may not necessarily imply a lack of desire in a child's education or growth, but rather reflect the limitations imposed by the family's socio-economic condition, such as time limits and work commitments.

Why Lower-Income Students are Lagging Behind

As results detailed in Tables 3 and 4 clearly demonstrate that students from poor households lag behind in terms of scholarship opportunities, Table 5 represents the Oaxaca-Blinder decomposition of the scholarship opportunity gap between students from poor and non-poor households without incorporating university fixed effect.

Based on the sampled participants in this study, students from non-poor households have a higher chance of receiving scholarships. The estimated average difference in scholarship opportunities between poor and non-poor households is 9% for Scholarship, 3.1% for Merit Scholarship, and 8.2% for Need Scholarship. Nevertheless, the disparity in scholarship opportunities can be primarily attributed to unexplained factors, which account for around 74% of the gap in scholarships, 93% in merit-based scholarships, and 76% in need-based scholarships. Typically, around 29% (0.026/0.090) of the difference can be attributed to the varying distribution of observable endowment factors. On average, these factors play a greater role in reducing the gap in scholarship opportunities in Model (1) compared to other models. Given that the majority of the disparity can be attributed to unobserved qualities or resources, it can be inferred that obstacles such as opportunity discrimination and other hidden hurdles continue to play a significant role in preventing students from disadvantaged backgrounds from accessing the scholarship. The outcomes can be ascribed to unquantifiable attributes such as the level of support provided by the high school system or the extent of dissemination of scholarship information, as well as intangible abilities, two examples of which include interpersonal skills or dedication.

Furthermore, Fig. 2 provides a detailed analysis of each observable endowment factor contributing to the disparity in scholarship opportunities. Within the explained portion of the scholarship opportunity gap, the disparity is particularly pronounced concerning parental educational attainment. Parental education accounts for approximately 15.25% of the gap for scholarships, 20.51% for merit-based scholarships, and 15.27% for need-based scholarships. It is not uncommon for students whose parents have higher levels of formal education to experience greater academic pressure, yet this phenomenon extends beyond them. Students from disadvantaged backgrounds, even those with highly educated parents, face additional challenges due to the constraints imposed by their socio-economic status. These challenges may prevent their parents from accessing broader support networks that could assist their children for educational opportunities. Similarly, a significant 6.33% gap in the need-based scholarship model regarding the number of siblings indicates that socio-economically disadvantaged families often cannot allocate resources exclusively to students intended to pursue higher education, hindering and downplaying their efforts to better prepare for educational opportunities. These findings highlight the multifaceted nature of educational disparities and stress the need for targeted interventions to support students from disadvantaged backgrounds.

High schools located in the capital of Phnom Penh significantly contribute to reducing the gap in opportunities between students from non-poor and poor households, reducing the gap by approximately 29% for both the Scholarship and Need Scholarship models, and 4% for the Merit Scholarship model. These reductions have prompted significant efforts to address inclusiveness. This finding has significant implications for the effectiveness of Cambodia's scholarship distribution system, particularly highlighting the efficiency of the system in the country's capital. However, unresolved questions remain regarding the support system in provincial high schools. To enhance nationwide efficiency, it is imperative to strengthen provincial support systems at the school level to assist students, particularly those from disadvantaged backgrounds, in successfully completing scholarship applications. Two important studies discussing information limitations on intricate scholarship and financial aid requirements that corroborate these findings are Heller (2016) and Scott-Clayton (2016). Strengthening these support systems can help ensure that all students, regardless of their socio-economic background and place of origin, have equitable access to scholarship opportunities.

The level of success in high school significantly influences the gap in scholarship opportunities, particularly for the Merit Scholarship Model, contributing approximately 18% to the disparity. The impact of high school achievement on reducing this gap is notable, provided that economically disadvantaged students can improve their performance in high-stakes examinations. However, students from economically disadvantaged backgrounds generally do not perform as well as their more affluent peers on national examinations, diminishing their chances of competing for scholarships. This finding is consistent with Wang et al. (2013) and reflects the scholarship policy of MoEYS, which typically awards scholarships based on students' academic merit as determined by their percentile rank in the 12th grade National Examination (MoEYS, 2018). Improving the performance of economically disadvantaged students in these examinations is crucial for enhancing their access to merit-based scholarships and reducing the overall disparity in scholarship opportunities.

While other observable endowment factors do not exert significant influence on the gap in scholarship opportunities, the geographical location of universities produces contradictory outcomes that add to the gap in scholarship opportunities. For instance, the implementation of the Merit Scholarship model can effectively narrow the gap between students from affluent backgrounds and those from low-income households by approximately 20%. In essence, students from both affluent and disadvantaged backgrounds have an equal likelihood of receiving a merit scholarship if they can achieve great academic performance. This finding is supported by the results of a recent study conducted by Smolentseva in 2020. Conversely, universities situated in the capital city of Phnom Penh account for around 8% of the gap in need scholarship opportunities. Mere statistical analysis is inadequate to elucidate this phenomenon. The gap can be partly explained by the fact that most prestigious universities in Phnom Penh prioritize attracting intellectually talented persons rather than those who have financial constraints. If this argument holds true, obtaining a scholarship for higher education at a university located outside of Phnom Penh is more attainable for poor students compared to universities in the capital city, maybe due to lower enrollment rates. Overall, these findings confirm the regressive nature of higher education in Cambodia, where privileged students often benefit at the expense of disadvantaged ones (Seyhah & Naron, 2020; UNDP, 2019).

Conclusion

The study examines how students’ socio-economic status affects the probability of high school graduates receiving a scholarship at the university level. Although limited to a single data period, this study adds significant values to existing literature and breaks a new ground by identifying significant associations between socio-economic status and scholarship outcomes. These findings provide strong and robust baseline evidence with important policy implications, offering insights into the equity and efficiency of scholarship screening mechanisms at Cambodian universities. Having said that, the need for targeted interventions is imperative to improve access to scholarships for students from economically disadvantaged backgrounds, ensuring a more equitable distribution of educational opportunities.

Scholarship programs offered by Cambodian public and private universities have aligned with the global development agenda and have helped the government enable a sizable proportion of Cambodia's high school graduates to continue their education at the university level. However, not all students, particularly those from socio-economically disadvantaged backgrounds, benefit from these programs. Therefore, the assumption that the scholarship distribution systems at Cambodian universities are inefficient and unfair is valid.

Many students do not receive the scholarships to which they are entitled. For example, although need-based scholarship is meant for students with disadvantaged backgrounds, opportunities are skewed heavily in favor of those who already have socio-economic privilege. It is clear that high school students need to be made aware of the scholarship application process, the qualities they should have, or the preparation they should undertake to be competitive for available scholarships. Parents, especially those from low-income households, should be informed about the scholarships that are available. This will allow parents to encourage and prepare their children for the opportunity, as not all students from socio-economically disadvantaged households may be eager to pursue it. The equity conundrum will become more pressing if this issue cannot be resolved.

To ensure that universities in Cambodia are applying the same standards of equity and consistency when selecting scholarship beneficiaries, a national scholarship selection guideline should be drafted and disseminated to responsible departments and Cambodian universities. To streamline the selection and distribution process, a thorough verification strategy should be the primary component for verifying the applicants' socio-economic status. There could be inconsistencies in the evaluation of scholarship applications and the selection of beneficiaries in the absence of uniform criteria. Scholarship applicants will be better prepared if the selection process is transparent and accountable, thanks to a list of criteria and a detailed description of how those criteria will be applied. Finally, a national scholarship selection guideline allows for greater standardization and coordination of scholarship programs nationwide. This has the potential to improve scholarship allocation and give more students access to much-needed financial aid for higher education. Additional funds should be allocated to offer subsistence allowance together with a tuition-waiver scholarship to socio-economically disadvantaged individuals. This effect is a significant contributor to rising intergenerational income mobility, which has the potential to address economic inequality by enabling students to continue their undergraduate studies. This will help Cambodia expand the stock of human capital for the country to keep pace with regional and global industrialization and servicification trends.

Future research, instead of testing for correlation, should employ mixed methods by incorporating quasi-experimental approach (i.e., Regression Discontinuity Design or Instrumental Variables) and in-depth study to determine what university characteristics (i.e., university’s scholarship selection policy and the availability of financial sources that contribute to the national scholarship schemes) cause high school graduates to earn scholarships. Using such improved and advanced methods, more robust estimation can be made to identify and explain the shortcomings of the current scholarship structure and make better policy recommendations.

Notes

The privatization of Cambodia's higher education in 1997 has been the most notable progress in the education sector since it was initiated by “Cambodia's National Action Plan for Higher Education”. Privatization resulted in two significant changes, one of which was the granting of permission for private universities to create and manage programs at the university level. Another pivotal change occurred with the implementation of neoliberalism, which designated public universities as Public Administration Institutions (PAI), empowering them to form a governing board with full authority over their activities and amass private capital. (Mak et al., 2019).

The study estimates: \({T}_{NP}-{T}_{P}=\left({X}_{NP}-{X}_{P}\right){\beta }_{NP}+{X}_{P}\left({\beta }_{NP}-{\beta }_{P}\right)+{(\varepsilon }_{NP}-{\varepsilon }_{P})\). This equation divides the gap in scholarship opportunities into two groups: One that is explained by observable factors and another that is attributed to unobservable predictors.

References

ADB (2011) Higher Education Across Asia: An Overview of Issues and Strategies, Manila: Asian Development Bank.

Alon, S. (2011) Who benefits most from financial aid? The heterogeneous effect of need-based grants on students’ college persistence. Social Science Quarterly 92(3): 807–829. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6237.2011.00793.x.

Baker, J.G. and Finn, M.G. (2008) Can a merit-based scholarship program increase science and engineering baccalaureates? Journal for the Education of the Gifted 31(3): 322–337. https://doi.org/10.4219/jeg-2008-766.

Becker, G. (1964) Human Capital: A Theoretical and Empirical Analysis, with Special Reference to Education, Cambridge: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Blinder, A.S. (1973) Wage Discrimination: Reduced form and structural estimates. The Journal of Human Resources 8(4): 436–455.

CDRI (2020) Higher Education Student Survey 2020, Phnom Penh: Cambodia Development Resource Institute.

CDRI and CADT (2021) Demand for and Supply of ICT and Digital Skills in Cambodia, Phnom Penh: Cambodia Development Resource Institute and Cambodia Academy of Digital Technology.

Chea, P. (2018) Equitable Access to Higher Education in Cambodia: Effects of Financial Aid for Low-Income Students', Ph.D. Dissertation. Graduate School of International Cooperation Studies, Kobe University.

Chea, P. (2019) Does higher education expansion in Cambodia make access to education more equal? International Journal of Educational Development 70: 102075. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2019.102075.

Chea, P., Hun, S. and Song, S. (2022a) Blurred identities: the hybridization of post-secondary education and training in Cambodia. Research in Post-Compulsory Education 27(2): 175–197. https://doi.org/10.1080/13596748.2022.2042904.

Chea, P., Tek, M.T. and Nok, S. (2022b) 'Are students financially incentivized to enroll in STEM majors in Cambodian higher education?', in P. Leng, P. Eam, S. Khieng and S. Song (eds.) Cambodian Post-Secondary Education and Training in the Global Knowledge SocietiesPhnom Penh: Cambodia Development Resource Institute, pp. 274–293.

Chet, C. (2009) 'Higher education in Cambodia', in Y. Hirosato and Y. Kitamura (eds.) The Political Economy of Educational Reforms and Capacity Development in Southeast Asia: Cases of CambodiaBerlin: Springer, pp. 153–165.

Cohn, E., Cohn, S., Balch, D.C. and Bradley, J. (2004) Determinants of undergraduate GPAs: SAT scores, high-school GPA and high-school rank. Economics of Education Review 23(6): 577–586. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2004.01.001.

Farrell, P.L. and Kienzl, G.S. (2009) Are state non-need, merit-based scholarship programs impacting college enrolment? Education Finance and Policy 4(2): 150–174. https://doi.org/10.1162/edfp.2009.4.2.150.

Friedman, B.M. (2017) 'The moral consequences of economic growth', in Jonathan B. Imber (ed.) Markets, Morals & ReligionNew York: Routledge, pp. 29–24.

Glick, P. (2008) What policies will reduce gender schooling gaps in developing countries: evidence and interpretation. World Development 36(9): 1623–1646. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2007.09.014.

Guimarães, P. and Portugal, P. (2010) A simple feasible procedure to fit models with high-dimensional fixed effects. The Stata Journal: Promoting Communications on Statistics and Stata 10(4): 628–649. https://doi.org/10.1177/1536867X1101000406.

Heckman, J.J., Stixrud, J. and Urzua, S. (2006) The effects of cognitive and noncognitive abilities on labor market outcomes and social behavior. Journal of Labor Economics 24(3): 411–482. https://doi.org/10.1086/504455.

Heller, D.E. (2016) 'Introduction', in D.E. Heller and C. Callender (eds.) Student Financing of Higher Education: A Comparative PerspectiveNew York: Routledge, pp. 30–38.

Kao, S. (2020) Family socioeconomic status and students’ choice of STEM majors: evidence from higher education of Cambodia. International Journal of Comparative Education and Development 22(1): 49–65. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCED-03-2019-0025.

Kao, S., Chea, P. and Song, S. (2023) Upper secondary school tracking and major choices in higher education: to switch or not to switch. Educational Research for Policy and Practice. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10671-023-09356-1.

Krafft, C. and Alawode, H. (2018) Inequality of opportunity in higher education in the Middle East and North Africa. International Journal of Educational Development 62(April): 234–244. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2018.05.005.

Leth, P.T. and Heang, S. (2011) Report on the process of selecting Special Priority and other Government Scholarships for entry to higher education in the 2011–2012 academic year, Phnom Penh: Ministry of Education, Youth, and Sport.

Lin, D., Lutter, R. and Ruhm, C.J. (2018) Cognitive performance and labour market outcomes. Labour Economics 51: 121–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.labeco.2017.12.008.

Lindahl, M. and Canton, E. (2007) 'The social returns to educations', in J. Hartog and H.M. Brink (eds.) Human Capital: Theory and EvidenceNew York: Cambridge University Press, pp. 21–37.

Liu, S., Wang, E. and Wang, X. (2021) Changes in the affordability of 4-year public higher education in China during massification. Asia Pacific Education Review 22(2): 273–289. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12564-020-09666-6.

Mak, N., Sok, S. and Un, L. (2019) Finance in Public Higher Education in Cambodia. Phnom Penh: Cambodia Development Resource Institute. CDRI Working Paper Series no. 115.

Marcucci, P. (2016) 'The politics of student funding policies from a comparative perspective', in D.E. Heller and C. Callender (eds.) Student Financing of Higher Education: A Comparative PerspectiveNew York: Routledge, pp. 40–77.

Minaya, V., Agasisti, T. and Bratti, M. (2022) When need meets merit: The effect of increasing merit requirements in need-based student aid. European Economic Review 146(14423): 104164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroecorev.2022.104164.

MoEYS (2014) Higher Education Vision 2030, Phnom Penh: Ministry of Education, Youth, and Sport.

MoEYS (2018) Guideline for Applicants to Apply for the Scholarship Into Higher Education in the Academic Year 2018–2019, Phnom Penh: Ministry of Education, Youth, and Sport.

MoEYS (2020) DGHE’s Statistics in the Academic Year 2018–2019, Phnom Penh: Ministry of Education, Youth, and Sport.

Morley, L. and Lugg, R. (2009) Mapping meritocracy: Intersecting gender, poverty and higher educational opportunity structures. Higher Education Policy 22(1): 37–60. https://doi.org/10.1057/hep.2008.26.

Navarra-Madsen, J., Bales, R.A. and Hynds, D.A.L. (2010) Role of scholarships in improving success rates of undergraduate Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (STEM) majors. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences 8(5): 458–464. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2010.12.063.

Schultz, T.W. (1961) Investment in human capital. The American Economic Review 51(5): 1035–1039.

Scott-Clayton, J. (2016) 'Information constraints and financial aid policy', in D.E. Heller and C. Callender (eds.) Student Financing of Higher Education: A Comparative PerspectiveNew York: Routledge, pp. 158–203.

Seyhah, V. and Naron, V. (2020) The Contribution of Vocational Skills Development to Cambodia ’s Economy. Phnom Penh: Ministry of Education, Youth, and Sport. CDRI Working Paper Series No. 122.

Silva, P.L., Nunes, L.C., Seabra, C., Balcao Reis, A. and Alves, M. (2020) Student selection and performance in higher education: admission exams vs. high school scores. Education Economics 28(5): 437–454. https://doi.org/10.1080/09645292.2020.1782846.

Sjoquist, D.L. and Winters, J.V. (2015) State merit-based financial aid programs and college attainment. Journal of Regional Science 55(3): 364–390. https://doi.org/10.1111/jors.12161.

Smolentseva, A. (2020) Marketisation of higher education and dual-track tuition fee system in post-Soviet countries. International Journal of Educational Development 78: 102265. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2020.102265.

Sweeder, R.D., Kursav, M.N. and Valles, S.A. (2021) A cohort scholarship program that reduces inequities in STEM retention. Journal of STEM Education 22(1): 5–13.

Teixeira, P. and Landoni, P. (2017) The Rise of Private Higher Education, in Rethinking the Public-Private Mix in Higher Education, Rotterdam: SensePublishers, pp. 21–34.

UNDP (2019) Economic Return to Investment in Education and TVET: Micro and Macro Perspectives, Phnom Penh: Ministry of Education, Youth, and Sport.

UNESCO (2015) Incheon Declaration and Framework for Action, Paris: UNESCO.

UNESCO (2020) Towards Universal Access to Higher Education: International Trends, Paris: UNESCO.

Wang, X., Liu, C., Zhang, L., Yue, A., Shi, Y., Chu, J. and Rozelle, S. (2013) Does financial aid help poor students succeed in college? China Economic Review 25(1): 27–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chieco.2013.01.003.

Wilson, Z.S., Iyengar, S.S., Pang, S.S., Warner, I.M. and Luces, C.A. (2012) Increasing access for economically disadvantaged students: the NSF/CSEM & S-STEM programs at Louisiana State University. Journal of Science Education and Technology 21(5): 581–587. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10956-011-9348-6.

World Bank (2012) Putting Higher Education to Work: Skills and Research for Growth in East Asia, Washington, DC: World Bank Group.

World Bank (2017) Higher Education Improvement Project (Heip)—Cambodia: Equity Assessment and Equity Plan, Phnom Penh: World Bank Group.

World Bank (2018) Cambodia: Higher Education and Capacity Improvement Implementation Completion Report, Phnom Penh: World Bank Group.

Acknowledgements

I would like to acknowledge the support from the Lancang-Mekong Cooperation that provided funding for the data collection of this study to the Cambodia Development Resource Institute. I express sincere gratitude to Prof. Yamada Shoko for generously providing her unparalleled insights during the process of formulating my research topic in her capacity as my academic advisor. In addition, I would like to express my gratitude to Prof. Christian Otchia, Prof. Utsumi Yuji and Dr. Chea Phal for their invaluable guidance and insightful feedback throughout the various stages of this research. My academic journey in Japan would not have been possible with the generosity and financial supports from the prestigious ADB-JSP fund.

Funding

Open Access funding provided by Nagoya University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The author declares that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

The research has been scrutiny by the management team of Cambodia Development Resource Institute. Before that, the Ministry of Education, Youth, and Sport examined, endorsed, and approved the concept note and survey questionnaire. The sampled universities also confirmed that the data collection processes followed ethical guidelines for research involving human subjects.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hun, S. Scholarship Schemes in Cambodian Higher Education: Unpacking Why Lower-Income Students are Lagging Behind. High Educ Policy (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41307-024-00369-w

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41307-024-00369-w