Abstract

Democracy is backsliding in Europe and around the world as citizens’ trust in elected representatives and institutions wanes. Representation theories and studies have mostly centred on the representatives, rather than the represented. But how do citizens perceive political representation? Are their perceptions of any consequence at all? In this paper, we set forth a framework of representation in the eyes of citizens, based on Pitkin’s classic concept of representation in conjunction with Weissberg’s distinction between dyadic and collective representations. We use Israel as a proof of concept for our theoretical framework, employing an original set of survey items. We find that, in keeping with Pitkin’s framework, citizens perceive representation as multidimensional and depreciate the descriptive and symbolic—the standing-for—dimensions. Furthermore, citizens’ democratic attitudes are shaped by collective representation by the parliament rather than by dyadic representation by an elected representative. We conclude with a call for a greater focus on representation from the citizens’ standpoint.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Democracy is backsliding in Europe and around the world as citizens’ trust in elected representatives and institutions wanes (Claassen 2020; Foa et al. 2022; Foa and Mounk 2017). The bulk of representation theories and studies have been focusing on the representatives: their claims (Saward 2010), how they mobilize and construct constituencies (Disch 2011; Mansbridge 2003), and what makes them good representatives (Dovi 2007). Considerably less is known about the represented and their perceptions of representation (De Mulder 2023; Wolkenstein and Wratil 2021). We ask: How do citizens perceive political representation? And, crucially, how do these perceptions relate to democratic attitudes?

In this study, we offer a theoretical framework for citizens’ perceptions of representation and test it empirically. Our approach draws from theoretical works in representation that focus on the audience (Rehfeld 2006; Saward 2010) and the citizen’s standpoint (Disch 2015), and from empirical studies on citizens’ preferences, perceptions, and expectations as regards political representation (Best and Seyis 2021; Harden 2016; Harden and Clark 2016; Holmberg 2020; Jones 2016; Lauermann 2014). Several studies have established that citizens’ perceptions of being represented (henceforth also representation perceptions or feelings of representation) can increase voter turnout (Blais, Singh, and Dumitrescu 2014; Kölln 2016), trust in the parliament (Dunn 2015), and satisfaction with democracy (van Egmond et al. 2020; Weßels 2011).

Our paper contributes in two important ways to the growing theoretical and empirical interest in citizens’ perceptions of representation. First, we put forth a framework of these perceptions, anchoring it in the foundations of representation theory: Pitkin’s (1967) classic multidimensional concept of representation and Weissberg’s (1978) distinction between dyadic and collective representations, where the former pertains to an elected representative and the latter to institutions. We draw on these foundations and move beyond previous studies, most of which investigated one or two of Pitkin’s dimensions at a time and focused mainly on dyadic representation (De Mulder 2023).

Second, we examine our theoretical framework empirically, contributing to the productive interface between political theory and empirical research (Mansbridge 2003). We developed a theoretically informed set of survey items designed to measure citizens’ perceptions and preferences of dyadic and collective representation along Pitkin’s four dimensions. As a proof of concept, we conduct an exploratory study in Israel, a country where all four dimensions are prominent.

Our results indicate that citizens view representation as multidimensional, contributing to their overall sense of being represented. We also find that citizens prefer to be represented on the formalistic and substantive dimensions, but these are not the dimensions they feel represented on. Furthermore, our results show that citizens perceive dyadic and collective representation differently, and that it is the latter that is largely regarded to be in deficit. Crucially, it is collective representation that relates to their attitudes towards democracy. We conclude by highlighting the importance of developing an agenda for studying citizens’ perceptions of representation in general, and of collective representation in particular.

Pitkinian representation: perceptions and preferences

Hanna Pitkin’s seminal book The Concept of Representation (1967) proposes a four-dimensional concept of representation: substantive representation of the public’s policy preferences and interests; formalistic representation of the rules that govern the workings of representative democracy; descriptive representation, which pertains to the resemblance between citizens and their representatives in various social categories; and symbolic representation, which is closely associated with issues of identity. Representation scholars broadly adopted Pitkin’s concept as their point of departure (Wolkenstein and Wratil 2021), studying, developing, criticizing, and expanding it (e.g. Politics & Gender 2012).

The literature on the substantive dimension has centred around congruence between policy decisions and constituents’ policy preferences (see Wlezien and Soroka 2007 for an overview), while research on the formalistic dimension has focused on electoral systems and procedures, accountability, and authorization (Powell 2000; Przeworski et al. 1999). An influential line of studies relates the formalistic aspect of electoral systems to the substantive or descriptive dimensions (Crisp et al. 2018; Powell 2000). Descriptive representation has been extensively studied in terms of sociological categories (Lijphart 1999; Lipset and Rokkan 1967; Verba, Nie, and Kim 1978), diversity, and inclusion (Mansbridge 1999; Phillips 1995; Young 2002), and in conjunction with substantive representation (Bailer et al. 2022; Celis and Childs 2020; Yildirim 2022). The symbolic dimension was the focus of studies on minority groups’ representation (Lombardo and Meier 2016; Marschall and Ruhil 2007; Sheafer et al. 2011) and has garnered attention in studies on the role of populist politicians in Europe and the USA (Cramer 2016; Reinemann, Matthes, and Sheafer 2016). Still, most empirical studies of representation have not explored all four dimensions in tandem (but see Krook 2020; Schwindt-Bayer and Mishler 2005).

The prioritization of the dimensions remains under scholarly debate. Pitkin and a long line of representation studies that followed her prioritized the substantive dimension over the descriptive and symbolic dimensions, relying on her often-quoted definition of representation as ‘acting in the interests of the represented, in a manner responsive to them’ (Pitkin 1967: 209). Pitkin deemed the descriptive and symbolic dimensions, which she labels standing-for representation, as less important for political representation (p. 232), because they depend on ‘the representative’s characteristics, on what he is or is like, on being something rather than doing something’ (Pitkin 1967, 61).

The prioritization of the formalistic dimension in Pitkin’s conceptualization has been less clear. Representation scholars, including Pitkin, have usually associated it with the institutions, rules, and procedures through which representatives are chosen (Krook 2020; Schwindt-Bayer and Mishler 2005). However, Pitkin acknowledged that, especially in the context of the accountability of a representative government (pp. 57–9, 234–40), this dimension pertains not only to institutions but also to the representative activity they enable: ‘the controls or accountability which they impose on the representative … are merely a device, a means to their ultimate purpose, which is a certain kind of behaviour on the part of the representative’ (p. 57). Some subsequent works have explicitly considered the formalistic dimension in tandem with the substantive dimension. Saward, for example, terms the two aspects of the formalistic dimension—authorization and accountability—as well as substantive representation as ‘three modes of acting-for’ (2010, 10). Rehfeld (2006) links the formalistic and substantive dimensions in his discussion of ‘the standard account’ of democratic political representation. Some empirical studies on the sources of citizens’ sense of representation have shown that the formalistic dimension (the quality of procedures and institutions) is no less, and may be even more, important than substantive representation (Hibbing and Theiss-Morse 2002; Rohrschneider 2002; 2005).

The concept of representation claim-making (Saward 2010) has put forth the importance of descriptive and symbolic representation. The vast scholarship on the representation of women and minority groups has emphasized descriptive representation (Celis and Childs 2008; Dovi and Wolbrecht 2023; Mansbridge 1999; Phillips 1995; Politics & Gender 2012; Young 2002). And the symbolic dimension is evident in the growing importance of the political-cultural cleavage that shapes citizens’ political preferences and voting behaviour (Dalton 2018; Shamir and Arian 1999).

There is little research into the dimensions of representation and their prioritization in the eyes of citizens (but see De Mulder 2023; Harden 2016). Constructivist theorists of representation have taken up Pitkin’s emphasis on representation as a relationship, seeing a pivotal role for the represented in making representation democratic (Brito Vieira 2017). However, it is still unclear whether Pitkin’s framework, on all of its dimensions and their prioritization, applies to the public. A multidimensional approach is essential for: (1) Examining citizens’ perceptions of representation—whether they feel represented on some dimensions and not others, and (2) Identifying citizens’ preferences of representation—the dimensions that citizens deem most important for their sense of representation.

Addressing this gap, we examine the Pitkinian prescription in the eyes of citizens and their representational preferences. We formulate citizens’ perceptions of Pitkin’s four dimensions: formalistic—perception of the representative’s accountability in using the authority bestowed on them; descriptive—the commonality of the background and sociological characteristics between the citizen and the representative; symbolic—feelings of belonging elicited by the representative; and substantive—perception of congruence between the citizen’s stances and the laws and policies espoused by the representative.

By advancing an approach that focuses on citizens’ perceptions of representation as multifaceted in terms of substantive, formalistic, descriptive, and symbolic representation, we examine which dimensions citizens prefer, which they deem as more important to them. Next, we implement this framework with regard to two types of representative agents—dyadic representation by an elected representative and collective representation by institutions.

Dyadic and collective representation

Following the pioneering study by Miller and Stokes (1963), representation has been customarily studied and theorized as dyadic representation, by an individual politician (see overviews by Dovi 2018; Mansbridge 2020). Weissberg (1978) challenged the dyadic approach and identified another type of representation: collective representation, obtained when ‘institutions collectively [represent] the people’ (p. 535). Pitkin (1967) acknowledged the importance of representation by institutions, and especially the substantive and formalistic dimensions thereof, in the concluding chapter of her book. Other scholars have also emphasized the importance of political institutions in making representative claims (Saward 2010), contributing to substantive representation (Brito Vieira 2017), and providing surrogate representation, by legislators one did not elect (Mansbridge 2003).

Collective representation as a ‘systemic property’ (Wlezien and Soroka 2007, 801) has received considerably less empirical and theoretical attention, and the existing scholarship focuses mostly on the substantive dimension (Lefkofridi 2020; Soroka and Wlezien 2010). Some of these studies do not place themselves within the representation literature, nor do they explicitly refer to ‘collective representation’ (e.g. Gilens and Page 2014; Page and Shapiro 1983; Stimson et al. 1995). A few comparative studies have focused on the importance of citizens’ perspectives on electoral institutions (Blais et al. 2021) and the influence of these views on citizens’ representational judgements (Rohrschneider 2005) and satisfaction with democracy (Karp et al. 2003). Highlighting the formalistic dimension in collective representation, Hibbing and Theiss-Morse (2002) found that when Americans evaluate their government, they care about process rather than policy, or in Pitkin’s terminology—formalistic, not substantive representation.

Several studies have demonstrated the effect of descriptive collective representation in the US state legislatures on voter turnout and on the sense of external efficacy among underrepresented groups (Atkeson and Carrillo 2007; Clark 2014; Uhlaner and Scola 2016). A few other studies examined the descriptive and substantive dimensions at the collective and dyadic levels and showed that dyadic descriptive representation alone is insufficient to affect substantive-collective representation (Harden and Clark 2016; Rocha et al. 2010).

Our framework encompasses citizens’ perceptions regarding both dyadic and collective representations. The ongoing decline in public trust in representative institutions accentuates the importance of distinguishing between citizens’ perceptions of collective versus dyadic representation. These modalities of representation have been defined and operationalized in the theoretical and empirical literature in a variety of ways, resulting in diverging findings (e.g. Andeweg 2011; Golder and Stramski 2010; Hurley 1982). We draw on Weissberg (1978) for collective representation and look at representation by the parliament. For dyadic representation, we consider the elected representative, which could be a single legislator or a political party, depending on the electoral system (Dalton 1985, 277–79; Wolkenstein and Wratil 2021, 866–67).

Empirical implications

The framework we propose in this study comprises citizens’ perceptions and preferences of four representation dimensions, applied to dyadic and collective representation. It informs four empirical implications: First, we examine whether citizens’ perception of being represented is multidimensional, encompassing Pitkin’s four dimensions of representation, or rather relies on the dimension they deem as the most important to them.

Second, we investigate citizens’ preferences of being represented on certain dimensions over others. As discussed above, Pitkin has prioritized the substantive dimension. Other scholars suggested that the formalistic dimension is more important. Still others have emphasized the importance of the descriptive and symbolic dimensions in representation claim-making, for the representation of minority groups, and as part of the cultural cleavage in established democracies. We thus explore which of the Pitkin-dimensions citizens deem more important to them.

Thirdly, we compare the above-mentioned citizens’ perceptions (multidimensional) and preferences (among dimensions) in dyadic and collective representation. We investigate whether the perception of representation is multidimensional in both dyadic and collective representations, and which dimensions citizens deem most important to them in dyadic and collective representation.

Finally, we explore the relationship between citizens’ representation perceptions and their attitudes towards democracy. We examine which has a stronger association with citizens’ democratic attitudes—their perceptions of representation on multiple dimensions or their perceptions of representation on the dimension they prefer most. In addition, since collective representation by institutions is the systemic context for dyadic representation, we investigate if citizens’ perceptions of representation by the parliament is more strongly associated with their democratic attitudes, compared to their perceptions of representation by an elected representative.

The empirical setting

Political representation in Israel

We employ Israel as a proof of concept for our theoretical framework. All four dimensions of representation have always been and still are central for the workings of its political system (Galnoor and Blander 2018; Horowitz and Lissak 1989). Therefore, the Israeli case provides us with a strong basis to assess whether these dimensions are also present in citizens’ perceptions of representation of dyadic and collective representation.

Israel is a multi-party system, with a nationwide party-list PR (proportional representation) electoral system and an electoral threshold of 3.25 per cent. Since Israeli voters vote for parties with closed lists, strictly speaking, the dyadic representative is a party, and the collective representative is the Knesset. However, Israel is characterized by high levels of personalization, so much so that voters often see individuals as their representatives (Lavi et al. 2022; Rahat and Kenig 2018).

This political system was designed to allow descriptive representation to its diverse societal groups (Hazan and Rahat 2000; 2010). Significant electoral and party reforms have put forward formalistic aspects of representation, while the nexus of descriptive, substantive, and symbolic representation is evident in the profound social rifts, issue-based cleavages, and collective identity dilemmas that shape Israeli politics (Arian and Shamir 2008; Rahat and Itzkovitch-Malka 2012; Shamir and Arian 1999). Representation predicaments pertaining especially to women, Arabs, and Mizrahi Jews keep all four dimensions prominent (Herzog 1984; Kook 2017; Shamir, Herzog, and Chazan 2020; Sheafer et al. 2011).

Our data are based on the April 2019 Israel National Election Study.Footnote 1 The election was held early, which is not unusual in Israeli politics. It was precipitated by a coalition crisis over the government’s policy towards Hamas in Gaza, a controversy regarding the military service of ultra-Orthodox Jews (a long-standing divisive issue in Israeli politics), and the attorney general’s recommendation to prosecute Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu for bribery and breach of trust. Being the first in the series of five elections within the next three and a half years, it preceded the political instability and the democratic crises that have ravaged Israel since.

Data and measurement

We rely on the pre-election wave of the Israel National Election Studies (INES) for the April 2019 election. The sample is representative of the Israeli electorate; interviews were conducted on the phone by Tel Aviv University’s B. I. and Lucille Cohen Institute for Public Opinion Research.Footnote 2

In keeping with our framework, we employed a set of items that we designed to establish and evaluate citizens’ perceptions of the four representation dimensions. These were examined both dyadically, with regard to a politician/party, and collectively, with regard to the Knesset (the Israeli parliament).Footnote 3 The survey comprised of four items for perceptions of dyadic and four items for collective representation, each targeting one of the dimensions. As concerns dyadic representation, respondents were asked to evaluate the extent to which a political party or a politician (1) Represents their views (substantive), (2) Shares their personal and background characteristics (descriptive), (3) Elicits a sense of belonging (symbolic), and (4) Uses the authority bestowed on them in a responsible/accountable manner (formalistic).Footnote 4 The collective representation items were worded similarly but referred to the Knesset. Following Pitkin’s four-dimension concept of representation, we employed these items to create two additive representation scales. The mean score for the dyadic scale is 0.600 (SD = 0.26) and for the collective scale 0.434 (SD = 0.23); Cronbach alpha for the dyadic scale is 0.778 and 0.746 for the collective scale.Footnote 5

Following these eight representation items, we asked the respondents to indicate their preference by asking which dimension is most important to them in dyadic and in collective representation. The collective item referred to the Knesset. The dyadic item was designed to prompt the respondents to think about their vote in the election (prompting the dyadic electoral connection) and to reflect on the dimension which was most important in guiding their vote. In another part of the questionnaire, we posed two general questions about respondents’ overall feelings of being represented, with no relation to any specific dimension: one item asks about overall representation by a political party or politician, and the other—about overall representation by the political system. Table 1 details the full list of the four dimensions and overall representation items and their descriptive statistics.

In formulating the survey items, we relied on Pitkin’s definitions and consulted with public opinion and election scholars on the best way to capture citizens’ perceptions in relation to each dimension. We also relied on in-depth interviews with 47 individuals, tapping into the phrasing they used in discussing representation.

To evaluate respondents’ attitudes towards democracy, we created a scale comprising 5 items on satisfaction with the way democracy works, satisfaction with the political system, trust in the government, trust in the parliament and trust in politicians. For each respondent, we summed the scores on these variables and rescaled the values to range between 0 and 1 (Cronbach alpha 0.818). These items were presented to half of the sample (N = 812). The exact wording and descriptive information of these variables is detailed in Table A1 in Online Appendix (henceforth OA).

The following variables were used as covariates in the analyses below: political ideology, gender, age, education, religiosity, nationality (Jewish or Arab), and socio-economic status (by density of living). Our controls do not include winners/losers due to the considerable overlap in Israel between these categories and right/left political ideology. The control variables and sample demographics are detailed in Tables A2 and A3 in the OA.Footnote 6

Analysis: patterns of representation in the eyes of the public

Multidimensional representation

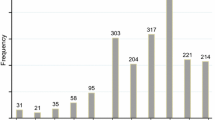

We begin our empirical exploration by looking at citizens’ perceptions of representation, specifically the number of dimensions on which citizens feel represented (Fig. 1). We find that some respondents do not feel represented at all: 24 per cent do not feel the Knesset represents them in any dimension and 13 per cent do not feel there is a party or a politician that represents them. Conversely, other respondents feel represented on all dimensions: 19 per cent in collective representation and 39 per cent in dyadic representation. The rest, 57 per cent in collective representation and 48 per cent in dyadic representation, feel represented on one, two, or three dimensions. This latter group of respondents evidently distinguish between dimensions of representation, as they feel represented in some dimensions but not in others.

The pattern of interrelationships between the representation dimensions provides another indication that citizens differentiate between dimensions. The correlations vary between 0.403 and 0.518 for dyadic representation, and between 0.350 and 0.516 for collective representation, implying that citizens’ perceptions of representation are comprised of distinguishable dimensions. The Cronbach alphas of the multidimensional scales (0.778 for the dyadic and 0.746 for the collective) indicate that they are coherent measures, bringing together the four dimensions into one overall sense of dyadic and collective representation.

A Principal Component Analysis of the eight representation items tells the same story: The initial results before rotation show that the first (best) factor covers almost half of the variance (45 per cent, eigenvalue 3.619), with all items loading highly and similarly on it, varying between 0.594 and 0.731. This means that there is a general sense of representation incorporating all 4 representation dimensions across both dyadic and collective representations. After (oblique) rotation, the results reveal two representation factors, the dyadic and the collective, each comprising of their four Pitkin dimensions. The two factors are quite strongly related (0.399).Footnote 7

To further examine our first empirical implication, we assess what matters more for our respondents’ overall representation perception: multidimensional sense of representation or feeling represented on one’s most important dimension. We estimate OLS linear regression models, using as the dependent variable the question on the overall sense of being represented by a politician or a party for the dyadic model, and the question on the overall sense of being represented by the political system for the collective model (see Table 2).Footnote 8 The regression results indicate that both the most important dimension and multidimensional representation contribute to citizens’ overall feeling of representation. However, the coefficients for multidimensional representation are almost double the size of those for the most important dimension. It holds for both dyadic and collective representations and is substantial even if we consider that the multidimensional scale is comprised of multiple items. Our findings thus indicate that citizens’ representation perceptions are multidimensional.

Representation preferences

We now move to examine the second empirical implication—respondents’ preferences of representation across dimensions. Table 3 presents crossed frequencies of the most important dimension for respondents in dyadic and collective representation. The frequencies show that citizens prefer to be represented on the formalistic and substantive dimensions. The formalistic dimension is most important to 37 per cent of the respondents, and substantive representation is most important to 17 per cent of the respondents. The most important dimensions for 16 per cent of the respondents are substantive-dyadic and formalistic-collective, while for 6 per cent, these are the formalistic-dyadic and substantive-collective dimensions. Altogether, 76 per cent prefer the formalistic and substantive dimensions at both levels, and 94 per cent prefer one of them at either level. Only 6 per cent prefer the two standing-for dimensions (descriptive and symbolic) at both levels and 24 per cent at either level.

These findings show that citizens’ preferences square with Pitkin’s low prioritization of the descriptive and symbolic dimensions as well as her emphasis on the substantive dimension for political representation. These preferences also echo previous studies that pointed at the importance of the formalistic dimension (Hibbing and Theiss-Morse 2002; Rohrschneider 2005).

Dyadic and collective representation

The third empirical implication applied citizens’ perceptions and preferences of representation to collective and dyadic representation. We find that in both dyadic and collective representations, citizens hold multidimensional perceptions, but the pattern of these perceptions and citizens’ preferences vary between the two.

Table 3 shows that respondents clearly distinguish between the dimensions and prefer the formalistic and substantive dimensions over the descriptive and symbolic. However, within this overall pattern, there are notable differences between dyadic and collective representations. In collective representation by the parliament, citizens prefer the formalistic dimension, while the substantive dimension is less important for them by a considerable margin (60 and 25 per cent, respectively). In dyadic representation by a politician or a political party, a similar weight is assigned by the respondents to the two dimensions, with 47 and 38 per cent preferring formalistic and substantive representation, respectively.

We also find different patterns in citizens’ perceptions of dyadic and collective representation. First, in Fig. 1, we showed that 62 per cent feel represented dyadically on three or all four dimensions in contrast with only 35 per cent who feel represented by the parliament. That is, more citizens feel represented in more dimensions dyadically, compared to collective representation.

Table 4 further develops these differences. It presents citizens’ perceptions and preferences of dyadic and collective representation. It shows the share of respondents who feel represented on a given dimension (perceptions) and the share of respondents for whom it is the most important (preferences). In dyadic representation, perceptions of representation are high across the board, with a majority of respondents feeling represented on each of the dimensions (varying between 61 and 71 per cent of respondents who feel represented). In collective representation, perceptions of representation are much lower, ranging between 40 and 58 per cent. A majority of citizens feel represented by the Knesset only in the descriptive dimension, while on the other three dimensions, a minority (of about 40 per cent) does. Thus, citizens consistently feel that they are better represented by a politician or a party than by the Knesset.

The implications of different patterns of representation perceptions are further clarified when combined with citizens’ preferences of representation (Table 4, right column). The findings show that citizens’ preferences do not match their perceptions of representation. As discussed above, the only dimension on which a majority of citizens feels represented by both the Knesset (58 per cent) and their elected representative (politician or party) (71 per cent) is the descriptive. However, this is also the dimension least important to them at both levels. This is especially consequential at the collective level, where most citizens do not feel represented in any of the other dimensions. In dyadic representation, there are other dimensions citizens feel represented on, resulting in more congruence between perceptions and preferences (the substantive dimension, for example, is second in importance and 67 per cent feel represented on it). In collective representation, by comparison, most citizens do not feel represented in the substantive, formalistic, and symbolic dimensions—all more important to them than the descriptive.

Indeed, the correlations between citizens’ representation perceptions and preferences are very low (see Table B5 in OA). Such low correlations preclude the possibility that citizens may assign more importance to the type of representation that they do not have. It also alleviates the empirical concern that responses to the items reflect an attempt to reduce cognitive dissonance, in the sense that people may prioritize a dimension on which they feel gratified or convince themselves they feel represented on a dimension which they value highly.

To sum, we find that citizens’ perceptions of being represented are multidimensional in both dyadic and collective representations, but that they feel less represented by the Knesset and prefer different dimensions, compared to their dyadic representatives (be it a party or a politician).

Representation and democracy in the eyes of the public

Our fourth empirical implication relates representation perceptions to attitudes towards democracy. Table 5 presents linear regression models of citizens’ attitudes towards democracy on their representation perceptions—multidimensional and the most important dimension. The results present a positive relationship between representation perceptions—especially multidimensional—and attitudes towards democracy. The first four models show higher coefficients for the multidimensional scales, compared to representation on the most important dimension (much like with the overall feeling of being represented, Table 2).Footnote 9

Table 5 establishes another important point with regard to dyadic and collective representation. Comparing between Models 1 and 3, and Models 2 and 4, we find that feeling represented by the parliament, whether on the most important dimension or across all dimensions, is more strongly related with citizens’ attitudes towards democracy than representation by one’s electoral representative (a party or a politician). Model 5 in the last column includes both dyadic and collective multidimensional representations and shows that only the collective scale remains significant. This finding reveals that it is only collective multidimensional representation that is significant in terms of citizens’ attitudes towards democracy.

Conclusion

This article presents a novel framework and an empirical exploration of citizens’ view of representation. Zooming in on the citizens, we find that their perceptions are Pitkinian in the sense that they fit her theoretical formulation of representation: citizens consider different dimensions of political representation and overwhelmingly care less about the descriptive and symbolic dimensions which Pitkin depreciates. These findings call for future studies that will explore individual, group, and country-level variations in representation perceptions and preferences, especially among minority and underserved groups.

We further find that citizens’ representation perceptions and preferences differ along dyadic vs. collective representation and that they are correlated with pro-democratic attitudes. Of the two, it is the multidimensional sense of representation at the collective level that relates to the overall sense of representation and to citizens’ democratic attitudes. Our study thus substantiates Weissberg’s (1978, 545–7) surmise that citizens may be more concerned with collective than dyadic representation. Yet, crucially, the findings indicate that citizens perceive this representation to be in deficit. The discrepancy is especially prominent when it comes to descriptive representation. Previous studies, as well as normative theories, have suggested that descriptive representation, especially by institutions, is germane to substantive representation. Our findings challenge this linkage. A majority of respondents felt represented by the parliament descriptively but not substantively, while the former dimension was the least important to them. Our results thus call for more theoretical and empirical attention to collective representation from the citizen’s standpoint, and for its multidimensional make-up.

Our examination of citizens’ perceptions and preferences of representation across multiple dimensions establishes their relevance to citizens’ attitudes towards democracy. Our findings show that the demand for representation is poorly met—citizens feel represented in dimensions that are not important to them. It is therefore not surprising that the correlation between feeling represented on the most important dimension and positive attitudes towards democracy is weaker than that of multidimensional perceptions of representation. A multidimensional approach to representation in the eyes of citizens is thus crucial for understanding the dynamics of democratic legitimacy and backsliding.

The present study is not without limitations. First, it focuses on one election in one country. The Israeli case was chosen as a proof of concept because it is known to encompass all four dimensions, allowing to examine citizens’ perceptions of them. The findings proved robust in another election in Israel. However, in other countries, Pitkin’s dimensions may manifest in other ways and reflect differently in citizens’ views of representation. Israel is surely not the only case in which all dimensions are manifested, but some of our findings—such as the prominence of the descriptive dimension—may be shaped by the characteristics of its political system. Future studies that will take a comparative perspective may examine how different aspects of electoral systems manifest in citizens’ perceptions of representation dimensions.

Second, Israel’s multi-party system may lead to a potential trade-off between fragmentation and representation at the dyadic and collective levels. The large number of parties could increase dyadic substantive representation but could make it more difficult to achieve substantive representation at the collective level, driving the differences we find in dyadic and collective representation. Future comparative studies could highlight whether this trade-off changes under different electoral systems.

Our theoretical framework draws from Pitkin’s classic conceptualization of representation, which has influenced a long line of theories and empirical studies of representation. Recent scholarship challenges Pitkin’s conceptualization and highlights new approaches and concepts, most notably the notion of the audience in the context of representation claim-making. Our framework of citizens’ perception of representation could be further developed in connection with the role of the audience in accepting and rejecting representation claims made by representatives.

In her last account of representation (2004), Pitkin ponders the intricate relationship between representation and democracy, observing that ‘the arrangements we call “representative democracy” have become a substitute for popular self-government, not its enactment’ (p. 34). If this is indeed so, the time is ripe to bring the citizens into our theories and studies of representation, especially collective representation by political institutions. The theoretical framework and the empirical examination in this study provide a first step in this direction.

Notes

On the 2019–21 elections in Israel, see Shamir and Rahat (2023).

The April 2019 pre-election wave was fielded between 24 February and 8 April 2019 and included 1,614 respondents (1,347 Jews, 267 Arabs). For all analyses, we rely on weighted data. The data are available on the INES website: https://www.tau.ac.il/~ines/2019.html

As mentioned above, while parties are the elected representative (dyadic) in Israel, the country is characterized by high levels of personalization. In addition, the vast majority of the representation literature considers dyadic representation in terms of individual representatives. The dyadic items thus mention both a party and an individual representative.

The phrasing of this item employs the word “אחראית” which means responsible or accountable, since there is no word in common Hebrew for accountable/accountability. Incorporating both authorization and accountability, the item is in line with the interconnections between form, institutions, and representative activity, as outlined in the theoretical discussion about the formalistic dimension above.

The two scales were recoded to range from 0 to 1, where a higher score indicates a stronger feeling of being represented on the four dimensions combined. The statistics include only those participants who responded to all the items making up the scales (N = 1,274 dyadic, N = 1,291 collective).

As a robustness check, we replicated our analysis on data from the INES March 2020 pre-election survey. This election was the third of the five Knesset elections Israel conducted in the course of three and a half years. The 2020 pre-election wave was in the field between 29 January and 1 March 2020, with 873 respondents (729 Jews, 144 Arabs). The results are very similar. The analyses for the March 2020 election are reported in section C of the OA.

See Table B6 in OA for full OLS regression results, including covariates. The lower number of observations here, compared to Table 2, is due to the fact that the attitude towards democracy items was presented to half of the sample. We replicate the analysis for the respondents who answered all the representation items Table B7 in OA.

References

Andeweg, R. 2011. Approaching Perfect Policy Congruence: Measurement, Development, and Relevance for Political Representation. In How Democracy Works, ed. M. Rosema, B. Denters, and K. Aarts, 39–52. Amsterdam University Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9789048513369-004.

Arian, A., and M. Shamir. 2008. A Decade Later, the World Had Changed, the Cleavage Structure Remained: Israel 1996–2006. Party Politics 14 (6): 685–705. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068808093406.

Atkeson, L.R., and N. Carrillo. 2007. More Is Better: The Influence of Collective Female Descriptive Representation on External Efficacy. Politics & Gender. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1743923X0707002X.

Bailer, S., C. Breunig, N. Giger, and A.M. Wüst. 2022. The Diminishing Value of Representing the Disadvantaged: Between Group Representation and Individual Career Paths. British Journal of Political Science 52 (2): 535–552. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123420000642.

Best, R.E., and D. Seyis. 2021. How Do Voters Perceive Ideological Congruence? The Effects of Winning and Losing under Different Electoral Rules. Electoral Studies 69 (February): 102201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2020.102201.

Blais, A., S. Singh, and D. Dumitrescu. 2014. Political Institutions, Perceptions of Representation, and the Turnout Decision. In Elections and Democracy: Representation and Accountability, ed. J. Thomassen, 99–112. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198716334.003.0006.

Blais, A., D. Bol, S. Bowler, D.M. Farrell, A. Fredén, M. Foucault, E. Heisbourg, et al. 2021. What Kind of Electoral Outcome Do People Think Is Good for Democracy? Political Studies, November. https://doi.org/10.1177/00323217211055560.

Brito Vieira, M. 2017. Performative Imaginaries: Pitkin versus Hobbes on Political Representation. In M Reclaiming Representation: Contemporary Advances in the Theory of Political Representation, ed. M. Brito Vieira, 25–50. Routledge.

Celis, K. 2020. Feminist Democratic Representation. Oxford University Press.

Celis, K., and S. Childs. 2008. Introduction: The Descriptive and Substantive Representation of Women: New Directions. Parliamentary Affairs 61 (3): 419–425. https://doi.org/10.1093/pa/gsn006.

Claassen, C. 2020. Does Public Support Help Democracy Survive? American Journal of Political Science 64 (1): 118–134. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12452.

Clark, C.J. 2014. Collective Descriptive Representation and Black Voter Mobilization in 2008. Political Behavior 36 (2): 315–333. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-013-9237-1.

Cramer, K.J. 2016. The Politics of Resentment. University of Chicago Press.

Crisp, B.F., B. Demirkaya, L.A. Schwindt-Bayer, and C. Millian. 2018. The Role of Rules in Representation: Group Membership and Electoral Incentives. British Journal of Political Science 48 (1): 47–67. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123415000691.

Dalton, R.J. 1985. Political Parties and Political Representation: Party Supporters and Party Elites in Nine Nations. Comparative Political Studies 18 (3): 267–299. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414085018003001.

Dalton, R.J. 2018. Political Realignment: Economics, Culture, and Electoral Change. Oxford University Press.

De Mulder, A. 2023. Making Sense of Citizens’ Sense of Being Represented. A Novel Conceptualisation and Measure of Feeling Represented. Representation 59 (4): 633–657. https://doi.org/10.1080/00344893.2022.2095662.

Disch, L. 2011. Toward a Mobilization Conception of Democratic Representation. American Political Science Review 105 (01): 100–114.

Disch, L. 2015. The ‘Constructivist Turn’ in Democratic Representation: A Normative Dead-End? Constellations 22 (4): 487–499.

Dovi, S. 2007. The Good Representative. Blackwell Pub.

Dovi, S., and C. Wolbrecht. 2023. Reevaluating the Contingent ‘Yes’: Essays on ‘Should Blacks Represent Blacks and Women Represent Women? Politics & Gender 19: 1231–1233. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1743923X22000277.

Dovi, S. 2018. Political Representation. In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, edited by Eץ N. Zelta. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2018/entries/political-representation.

Dunn, K. 2015. Voice, Representation and Trust in Parliament. Acta Politica 50 (2): 171–192. https://doi.org/10.1057/ap.2014.15.

Foa, R.S., and Y. Mounk. 2017. The Signs of Deconsolidation. Journal of Democracy 28 (1): 5–15. https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2017.0000.

Foa, R.S., Y. Mounk, and A. Klassen. 2022. Why the Future Cannot Be Predicted. Journal of Democracy 33 (1): 147–155. https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2022.0010.

Galnoor, I., and D. Blander. 2018. The Handbook of Israel’s Political System, 1st ed. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781316160978.

Gilens, M., and B.I. Page. 2014. Testing Theories of American Politics: Elites, Interest Groups, and Average Citizens. Perspectives on Politics 12 (3): 564–581. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592714001595.

Golder, M., and J. Stramski. 2010. Ideological Congruence and Electoral Institutions. American Journal of Political Science 54 (1): 90–106. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2009.00420.x.

Harden, J.J. 2016. Multidimensional Democracy: A Supply and Demand Theory of Representation in American Legislatures. Cambridge University Press.

Harden, J.J., and C.J. Clark. 2016. A Legislature or a Legislator Like Me? Citizen Demand for Collective and Dyadic Political Representation. American Politics Research 44 (2): 247–271. https://doi.org/10.1177/1532673X15594000.

Hazan, R.Y., and G. Rahat. 2000. Representation, Electoral Reform, and Democracy: Theoretical and Empirical Lessons from the 1996 Elections in Israel. Comparative Political Studies 33 (10): 1310–1336. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414000033010003.

Hazan, R.Y., and G. Rahat. 2010. Democracy Within Parties: Candidate Selection Methods and Their Political Consequences. Oxford University Press.

Herzog, H. 1984. Ethnicity as a Product of Political Negotiation: The Case of Israel. Ethnic and Racial Studies 7 (4): 517–533.

Hibbing, J.R., and E. Theiss-Morse. 2002. Stealth Democracy: Americans’ Beliefs About How Government Should Work. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511613722.

Holmberg, S. 2020. Feeling Represented. In The Oxford Handbook of Political Representation in Liberal Democracies, ed. R. Rohrschneider and J.J.A. Thomassen, 413–432. Oxford University Press.

Horowitz, D., and M. Lissak. 1989. Trouble in Utopia: The Overburdened Polity of Israel. State University of New York Press.

Hurley, P.A. 1982. Collective Representation Reappraised. Legislative Studies Quarterly 7 (1): 119. https://doi.org/10.2307/439695.

Jones, P.E. 2016. Constituents’ Responses to Descriptive and Substantive Representation in Congress. Social Science Quarterly 97 (3): 682–698. https://doi.org/10.1111/ssqu.12243.

Karp, J.A., S.A. Banducci, and S. Bowler. 2003. To Know It Is to Love It?: Satisfaction with Democracy in the European Union. Comparative Political Studies 36 (3): 271–292. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414002250669.

Kölln, A.-K. 2016. The Virtuous Circle of Representation. Electoral Studies 42 (June): 126–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2016.02.011.

Kook, R. 2017. Representation, Minorities and Electoral Reform: The Case of the Palestinian Minority in Israel. Ethnic and Racial Studies 40 (12): 2039–2057. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2017.1277027.

Krook, M.L. 2020. Electoral Quotas and Group Representation. In Research Handbook on Political Representation, ed. M. Cotta and F. Russo, 198–210. Edward Elgar Publishing.

Lauermann, R.M. 2014. Constituent Perceptions of Political Representation. Palgrave Macmillan US. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137400437.

Lavi, L., N. Rivlin-Angert, C. Treger, T. Sheafer, I. Waismel-Manor, and M. Shamir. 2022. King Bibi: The Personification of Democratic Values in the 2019–2021 Election Cycle. In The Elections in Israel, 2019–2021, ed. M. Shamir and G. Rahat, 77–98. Routledge.

Lefkofridi, Z. 2020. Opinion-Policy Congruence. In The Oxford Handbook of Political Representation in Liberal Democracies, ed. R. Rohrschneider and J.J.A. Thomassen, 357–376. Oxford University Press.

Lijphart, A. 1999. Patterns of Democracy: Government Forms and Performance in Thirty-Six Countries. Yale University Press.

Lipset, M., and S. Rokkan, eds. 1967. Party Systems and Voter Alignments: Cross-National Perspectives. The Free Press.

Lombardo, E., and P. Meier. 2016. The Symbolic Representation of Gender. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315552408.

Mansbridge, J. 1999. Should Blacks Represent Blacks and Women Represent Women? A Contingent ‘Yes.’ The Journal of Politics 61 (3): 628–657. https://doi.org/10.2307/2647821.

Mansbridge, J. 2003. Rethinking Representation. American Political Science Review 97 (04): 515–528.

Marschall, M.J., and A.V.S. Ruhil. 2007. Substantive Symbols: The Attitudinal Dimension of Black Political Incorporation in Local Government. American Journal of Political Science 51 (1): 17–33. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2007.00234.x.

Miller, W.E., and D.E. Stokes. 1963. Constituency Influence in Congress. American Political Science Review 57 (1): 45–56. https://doi.org/10.2307/1952717.

Page, B.I., and R.Y. Shapiro. 1983. Effects of Public Opinion on Policy. American Political Science Review 77 (1): 175–190. https://doi.org/10.2307/1956018.

Phillips, A. 1995. Politics of Presence. Clarendon Press.

Pitkin, H.F. 1967. The Concept of Representation. University of California Press.

Pitkin, H.F. 2004. Representation and Democracy: Uneasy Alliance. Scandinavian Political Studies 27 (3): 335–342. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9477.2004.00109.x.

Politics & Gender. 2012. Symposium: Hanna Pitkin’s ‘Concept of Representation’ Revisited: Critical Perspectives on Gender and Politics. Politics & Gender 8 (4): 508–547.

Powell, G.B. 2000. Elections as Instruments of Democracy: Majoritarian and Proportional Visions. Yale University Press.

Przeworski, A., S.C. Stokes, and B. Manin. 1999. Democracy, Accountability, and Representation. Cambridge University Press.

Rahat, G., and R. Itzkovitch-Malka. 2012. Political Representation in Israel: Minority Sectors VS. Women. Representation 48 (3): 307–319. https://doi.org/10.1080/00344893.2012.706986.

Rahat, G., and O. Kenig. 2018. From Party Politics to Personalized Politics? Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780198808008.001.0001.

Rehfeld, A. 2006. Towards a General Theory of Political Representation. The Journal of Politics 68 (1): 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2508.2006.00365.x.

Reinemann, C., J. Matthes, and T. Sheafer. 2016. Citizens and Populist Political Communication. In Populist Political Communication in Europe, ed. T. Aalberg, F. Esser, C. Reinemann, J. Stromback, and C. De Vreese, 381–394. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315623016.

Rocha, R.R., C.J. Tolbert, D.C. Bowen, and C.J. Clark. 2010. Race and Turnout: Does Descriptive Representation in State Legislatures Increase Minority Voting? Political Research Quarterly 63 (4): 890–907. https://doi.org/10.1177/1065912910376388.

Rohrschneider, R. 2002. The Democracy Deficit and Mass Support for an EU-Wide Government. American Journal of Political Science 46 (2): 463–475. https://doi.org/10.2307/3088389.

Rohrschneider, R. 2005. Institutional Quality and Perceptions of Representation in Advanced Industrial Democracies. Comparative Political Studies 38 (7): 850–874. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414005276305.

Rohrschneider, R., J. Thomassen, and J. Mansbridge. 2020. The Evolution of Political Representation in Liberal Democracies: Concepts and PracticesConcepts and Practices. In The Oxford Handbook of Political Representation in Liberal Democracies, ed. R. Rohrschneider, J. Thomassen, and J. Mansbridge, 15–54. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780198825081.013.1.

Saward, M. 2010. The Representative Claim. Oxford University Press.

Schwindt-Bayer, L.A., and W. Mishler. 2005. An Integrated Model of Women’s Representation. The Journal of Politics 67 (2): 407–428. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2508.2005.00323.x.

Shamir, M., and G. Rahat, eds. 2023. The Elections in Israel 2019–2021. Routledge.

Shamir, M., and A. Arian. 1999. Collective Identity and Electoral Competition in Israel. American Political Science Review 93 (2): 265–277.

Shamir, M., H. Herzog, and N. Chazan, eds. 2020. Gender Gaps in Israeli Politics. The Van Leer Institute and Am Oved.

Sheafer, T., S.R. Shenhav, and K. Goldstein. 2011. Voting for Our Story: A Narrative Model of Electoral Choice in Multiparty Systems. Comparative Political Studies 44 (3): 313–338.

Soroka, S.N., and C. Wlezien. 2012. Degrees of Democracy: Politics, Public Opinion, and Policy. Cambridge University Press.

Stimson, J.A., Michael B. Mackuen, and Robert S. Erikson. 1995. Dynamic Representation. American Political Science Review 89 (03): 543–565.

Uhlaner, C.J., and B. Scola. 2016. Collective Representation as a Mobilizer: Race/Ethnicity, Gender, and Their Intersections at the State Level. State Politics & Policy Quarterly 16 (2): 227–263. https://doi.org/10.1177/1532440015603576.

van Egmond, M., R. Johns, and H. Brandenburg. 2020. When Long-Distance Relationships Don’t Work out: Representational Distance and Satisfaction with Democracy in Europe. Electoral Studies 66 (August): 102182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2020.102182.

Verba, S., and N.J.O. NieKim. 1978. Participation and Political Equality: A Seven Nation Comparison. Cambridge University Press.

Weissberg, R. 1978. Collective vs. Dyadic Representation in Congress. American Political Science Review 72 (2): 535–547. https://doi.org/10.2307/1954109.

Wessels, B. 2011. Performance and Deficits of Present-Day Representation. In The Future of Representative Democracy, ed. S. Alonso, J. Keane, and W. Merkel, 96–123. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511770883.005.

Wlezien, C., and S.N. Soroka. 2007. The Relationship Between Public Opinion and Policy. In The Oxford Handbook of Political Behavior, ed. R.J. Dalton and H.D. Klingemann, 799–817. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199270125.003.0043.

Wolkenstein, F., and C. Wratil. 2021. Multidimensional Representation. American Journal of Political Science 65 (4): 862–876. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12563.

Yildirim, T.M. 2022. Rethinking Women’s Interests: An Inductive and Intersectional Approach to Defining Women’s Policy Priorities. British Journal of Political Science 52 (3): 1240–1257. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123421000235.

Young, I.M. 2002. Inclusion and Democracy. Oxford University Press.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by The Israel Science Foundation (Grant No. 2315/18).

Funding

Open access funding provided by Bar-Ilan University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lavi, L., Treger, C., Rivlin-Angert, N. et al. The Pitkinian public: representation in the eyes of citizens. Eur Polit Sci (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41304-024-00489-2

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41304-024-00489-2