“The border city of El Paso, Texas, used to have extremely high rates of violent crime – one of the highest in the country, and considered one of our nation’s most dangerous cities. Now, immediately upon its building, with a powerful barrier in place, El Paso is one of the safest cities in our country.”

Former President Donald Trump

State of the Union address

February 5, 2019

Abstract

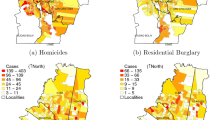

Despite a lack of rigorous empirical evidence, reduced crime is often touted as a potential benefit in the debate over increasing border infrastructure (i.e., border walls). This paper examines the effect of the Secure Fence Act of 2006, which led to unprecedented barrier construction along the US–Mexico border, on local crime using geospatial data on dates and locations of border wall construction. Synthetic control estimates across twelve border counties find no systematic evidence that border infrastructure reduced property or violent crime rates in the counties in which it was built. Further analysis using matched panel models indicates no effect on property crime rates and that observed declines in violent crime rates precede barrier construction, not the other way around. Taken together, this paper finds that potential crime reductions are not a compelling argument toward the benefits of expanding border infrastructure.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Advocacy for border walls continued beyond the end of the Trump presidency, as evidenced by Texas Governor Greg Abbot’s push to use state funds to build border walls in Texas.

Throughout this study, we use the terms “wall,” “barrier,” and “fence” interchangeably.

For example, Allen et al. (2019) look at the labor market effects of building walls along the US–Mexico border.

An advantage of using county-level data in our analysis is that we can effectively control for immigration policies such as SB 1070 that are enacted at the federal and state level, as our analysis focuses on individual counties within states.

Authors’ calculations based on total crossings of bus passengers, pedestrians, and vehicle passengers across 27 different legal ports of entry along the US–Mexico border for the year 2018. Data source is US Department of Transportation (2019).

UCLA Labor Center (2019).

For example, Amuedo-Dorantes and Arenas-Arroyo (2019) find that immigrants are more likely to report domestic violence in “sanctuary cities,” locations with policies that limit the cooperation of local law enforcement with Immigration and Customs Enforcement.

The RMSPE for county i across periods \(1 - s\) is calculated as \(\sqrt{\frac{1}{s}\sum _{t=1}^s {\hat{\alpha }}^2_{it}}\).

For example, if there are 10 placebo estimates with post-/pre-RMSPE ratios larger than the treated unit, and \(N+1 = 243\), the quasi-p value would be 11/243 = 0.045. Also note that, because we are agnostic on the direction of the effect, our ranking is only on the RMSPE, not the sign of the estimated average effect.

The online appendix may be accessed at https://sites.google.com/sdsu.edu/hishamfoad/research/border-walls.

Figure A8 in the online appendix plots average crime rates across our treated counties and the weighted average of control counties. Comparing this plot to Fig. 4, the matched sample does is better able to align the pre-period crime rates than the full sample.

We use 97.5% rather than 100% only because there are a large number of counties that show very small sections completed only in the last year. As such, we believe that 97.5% provides a more meaningful end date of the construction.

These numbers are in 2008 dollars. In terms of today’s prices, the same figures would be $7.8 and $2.0 million per mile, respectively. Source: US Government Accountability Office (2009) For a side-by-side visual comparison of the two types of barriers, see Figure A1 in the online Appendix.

Table A21 presents the estimates from these models, and Table A22 presents the results split by construction completion date.

We present the graph of averages for these two groups in the online appendix. We also estimated a difference-in-differences model using county income and population as controls with both county and year fixed effects. The average treatment effect of border wall construction (defined as counties experiencing construction activity during the period 2006–2011) is statistically insignificant.

Our earlier analysis of these data suggests limited internal mobility of migrants, implying that those migrating to border counties tend to stay in border counties.

Construction cost estimates reported in US Government Accountability Office (2009). Miles of border wall constructed include all construction from 2006 to 2014 based on authors’ calculations. Vehicle barriers are not included so as to estimate a lower bound of construction costs.

This was computed by first looking at the breakdown of violent crimes in Santa Cruz County over the sample period as 4% murder, 12% rape, 32% robbery, and 52% aggravated assault. We then multiplied these weights by the costs in Chaflin and McCrary (2018) of $7,000,000 per murder, $142,000 per rape, $12,624 per robbery, and $38,924 per assault.

References

Abadie, A., A. Diamond, and J. Hainmueller. 2010. Synthetic control methods for comparative case studies: Estimating the effect of California’s tobacco control program. Journal of the American statistical Association 105 (490): 493–505.

Abadie, A., A. Diamond, and J. Hainmueller. 2015. Comparative politics and the synthetic control method. American Journal of Political Science 59 (2): 495–510.

Abadie, A., and J. Gardeazabal. 2003. The economic costs of conflict: A case study of the Basque Country. American Economic Review 93 (1): 113–132.

Allen, T., C. Dobbin, and Morten, M. 2019. Border walls. NBER Working Paper, No. 25267.

Alonso-Borrego, C., N. Garoupa, and P. Vázquez. 2012. Does immigration cause crime? Evidence from Spain. American Law and Economics Review 14 (1): 165–191.

Amuedo-Dorantes, C. and E. Arenas-Arroyo, 2019. Immigration enforcement, police trust, and domestic violence. Unpublished manuscript. Retreived on October 28, 2019 from www.estherarenasarroyo.com.

Becker, G. 1968. Crime and punishment: An economic approach. Journal of Political Economy 76 (2): 169–217.

Bell, B., F. Fasani, and S. Machin. 2013. Crime and immigration: Evidence from large immigrant waves. Review of Economics and Statistics 95 (4): 1278–1290.

Bianchi, M., P. Buonnano, and P. Pinotti. 2012. Do immigrants cause crime? Journal of the European Economics Association 10 (6): 1318–1347.

Billmeier, A., and T. Nannicini. 2013. Assessing economic liberalization episodes: A synthetic control approach. Review of Economics and Statistics 95 (3): 983–1001.

Bohn, S., M. Lofstrom, and S. Raphael. 2014. Did the 2007 legal Arizona workers act reduce the state’s unauthorized immigrant population? Review of Economics and Statistics 96 (2): 258–269.

Butcher, K., and A. Piehl. 1998. Cross-city evidence on the relationship between immigration and crime. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 17: 457–493.

Butcher, K., and A. Piehl, 2007. Why are immigrants’ incarceration rates so low? Evidence on selective immigration, deterrence, and deportation. NBER Working Paper, No. 13229.

Carrión-Flores, C. and T. Sorensen, 2006. The effects of border enforcement on migrants’ border crossing choices: Diversion or deterrence? Unpublished manuscript. Retreived on June 28th, 2021 from http://cream-migration.org.

Castañeda, L., and B. Quester, 2017. America’s wall. inewssource and KPBS.

Chaflin, A. 2014. What is the contribution of Mexican immigration to U.S. crime rates? Evidence from rainfall shocks in Mexico. American Law and Economics Review 16 (1): 220–268.

Chaflin, A., and J. McCrary. 2018. Are U.S. cities underpoliced? Theory and evidence. Review of Economics and Statistics 100 (1): 167–186.

Dudley, S. 2018. Trump’s border policies strengthen organized crime. Here’s how. Insight Crime. Reterived on May 15, 2019 from http://www.insightcrime.org

Dustmann, C., U. Schönberg, and J. Stuhler. 2017. Labor supply shocks, native wages, and the adjustment of local employment. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 132 (1): 435–483.

Ehrlich, I. 1973. Participation in illegitimate activities: A theoretical and empirical investigation. Journal of Political Economy 81 (3): 521–565.

Feigenberg, B. 2019. Fenced out: why rising migration costs matter. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics (Forthcoming).

Ferman, B., C. Pinto, and V. Possebom. 2020. Cherry picking with synthetic controls. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 39 (2): 510–532.

Gobillon, L., and T. Magnac. 2016. Regional policy evaluation: Interactive fixed effects and synthetic controls. Review of Economics and Statistics 98 (3): 535–551.

Hanson, G., and A. Spilimbergo. 1999. Illegal immigration, border enforcement, and relative wages: Evidence from apprehensions at the U.S.-Mexico border. American Economic Review 89 (5): 1337–1357.

Hinrichs, P. 2012. The effects of affirmative action bans on college enrollment, educational attainment, and the demographic composition of universities. Review of Economics and Statistics 94 (3): 712–722.

Hoekstra, M., and S. Orozco-Aleman. 2017. Illegal immigration, state law, and deterrance. American Economic Journal: Policy 9 (2): 228–252.

Kaul, A., S. Klößner, G. Pfeifer, and M. Schieler, 2015. Synthetic control methods: Never use all pre-intervention outcomes together with covariates. Working Paper.

Laughlin, B. 2019. Border fences and the Mexican drug war. Unpublished manuscript. Retrieved on February 13, 2019 from www.benjamin-laughlin.com.

Miles, T., and A. Cox. 2014. Does immigration enforcement reduce crime? Evidence from Secure Communities. Journal of Law and Economics 57 (4): 937–973.

Mok, P., A. Astrup, M. Carr, S. Antonsen, R. Webb, and C. Pedersen. 2018. Experience of child-parent separation and later risk of violent criminality. American Journal of Preventative Medicine 55 (2): 178–186.

Nowraseth, A. January 8, 2019. The cost of the border wall keeps climbing and it’s becoming less of a wall. Cato Institute. Retrieved on May 15, 2019 from www.cato.org.

Nuñez-Neto, B., and S. Viña. 2006. Border security: Barriers along the U.S. international border. Congressional Research Service.

Orrenius, P., and R. Coronado. 2015. The effect of illegal immigration and border enforcement on crime rates along the U.S.-Mexico border. UCSD Center for Comparative Immigration Studies Working Paper, 131.

Roberts, B., G. Hanson, D. Cornwell, and S. Borger. 2010. An analysis of migrant smuggling costs along the southwest border. Department of Homeland Security: Office of Immigration Statistics Working Paper, November 2010.

Sandner, M., and P. Wassman. 2018. The effect of changes in border regimes on border regions crime rates: Evidence from the Schengen Treaty. Kyklos 71 (3): 482–506.

Soares, R. 2004. Development, crime and punishment: Accounting for the international differences in crime rates. Journal of Development Economics 73: 155–184.

Spenkuch, J. 2014. Understanding the impact of immigration on crime. American Law and Economics Review 16 (1): 177–219.

Stana, R., S. Quinland, and J. Espinola. 2009. Secure border initiative fence construction costs. Government Accountability Office (GAO).

UCLA Labor Center 2019. The Bracero Program. Retreived on May 30, 2019 from http://braceroarchive.org.

United Nations Population Division. 2017. International migration report.

U.S. Department of Homeland Security. 2019. DHS Budget. http://www.dhs.gov/dhs-budget.

U.S. Department of Transportation. 2019. Border Crossing Entry Data. Retreived on May 30, 2019 from http://data.transportation.gov.

U.S. Government Accountability Office. 2009. Secure Border Initiative Fence Construction Costs. Retreived on February 23, 2020 from gao.gov.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Abman, R., Foad, H. Border Walls and Crime: Evidence From the Secure Fence Act. Eastern Econ J 48, 167–197 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41302-021-00207-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41302-021-00207-6