Abstract

This study assesses democratic changes against the background of an increased use of referendums in European parliamentary systems. Existing studies on why referendums have become more frequent argue that it is due to the so-called ‘blurring’ of political alignments aiming to bypass institutional veto players. Which change of conditions is sufficient for a more frequent use of referendums? The proposed domestic conditions do not exclude external reasons, and related studies imply that various combinations of internal and external factors are worth exploring further. Accordingly, in our study we assess the configurations of political-institutional changes by using time-differencing Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA). First, we find that democratic convergence leads to multiple explanatory paths for referendum use. Second, the result suggests that explanations with simple majoritarian dynamics are robust compared to other explanations showing convergence. Third, the existence of many veto players combined with economic globalization is identified as an alternative explanation to the convergence toward more frequent referendum use. This study advances referendum and European integration research by highlighting the dynamics of simple majoritarian democratic systems, but also veto players and globalization over time. The results imply that more attention should be given to the configurational nature of an increased rise in referendums in European democracies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

This study assesses the dynamics of democratic change against the background of a more frequent use of referendums in European parliamentary systems. The rise of referendums has received increasing attention in connection with the rapid progress of European integration since the 1990s (e.g., Mendez et al. 2014; Beach 2018; Smith 2021; Qvortrup 2021). The dynamics behind this trend are, however, not simple and intertwined with questions about the legitimacy of parliamentary systems as well as the democratic deficit of the European Union (EU), especially during the so-called ‘permissive consensus’ of deals cut by insulated elites until the 1980s (Hooghe and Marks 2008). Populist rhetoric against change in European democracies is often combined with calls for more popular decision-making. Moreover, authoritarian referendums have been shown to be instrumental in the process of consolidating non-democratic regimes (Penadés and Velasco 2022, 2024). However, empirical studies suggest that the rise of referendums is not necessarily associated with populist values, perceptions, or behaviour (e.g., Gherghina and Silagadze 2020), and some studies highlight that referendums have the potential to enhance inclusive political participation (e.g., Rose and Weßels 2021).

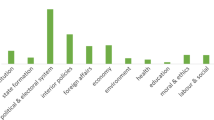

Which change of conditions is sufficient for a more frequent use of referendums? We aim to compare macro-level changes in European parliamentary democracies in the use of referendums, defined as the institutionalization of popular votes in the decision-making process (see Altman 2015). Referendums can be generalized as any popular vote on a policy issue, including both binding and consultative votes as well as votes on government proposals and citizen initiatives. Our focus is on general trends in the institutionalized practices, which have often taken the form of government-initiated, non-government-initiated, and obligatory referendums (see Morel 2007). Therefore, we do not aim to identify which types of referendums (e.g., EU-related, advisory, or constitutionally required referendums) produce specific outcomes (Beach 2018; see also Silagadze and Gherghina 2018).

Previous macro-level studies based on cross-case comparisons have, for one, elucidated country-specific features, such as the reasons behind the popular vote in Switzerland, the country with the most experience with referendums (see Smith 2021). For another, the use of referendums has been understood as an extension of the simple majoritarian type of parliamentary democracies, where winner-takes-all prevails in institutional arrangements (Lijphart 2012; Silagadze and Gherghina 2018; Vospernik 2018; Hollander 2019). However, even if we assume that the simple majoritarian type contributes to the use of referendums, previous studies have paid little attention to patterns of institutional change over time in different contexts. This relates to patterns such as the (dis)promotion of economic globalization, the (de)legitimation of European integration, and veto players in the decision-making process (Bogdanor 1994; Setälä 1999; Prosser 2016; see also Vatter et al. 2014). In contrast, micro-level studies explicitly focus on temporal changes in referendum support (e.g., Kern and Hooghe 2018; Rojon and Rijken 2021). To provide an integrative understanding of previous research, our study is designed to identify changes over time toward increased referendum use based on changing institutional arrangements in parliamentary democracies.

To fill the gap of research on the change over time (i.e., the temporal dynamics) of democratic institutional patterns and their relation to referendums, methodologically we rely on time-differencing Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA). QCA was originally developed by Ragin (1987) and can be used to conduct a comparison of complex combinations of conditions (so-called configurations). In the configurational comparison, one can systematically assess necessity and sufficiency for target outcomes based on set theoretical assumptions.Footnote 1 Less attention, however, has been paid to cross-sectional and time series data analysis with QCA (Verweij and Vis 2020). To assess the dynamics of changing institutional arrangements towards an increased use of referendums, this contribution extends QCA to time-differencing QCA, proposed as a set theoretical technique for time series data analysis (TS/QCA) by Hino (2009; see Pagliarin and Gerrits 2020).

The article is structured as follows: First, we briefly discuss the relevant literature to construct multiple (i.e., conjunctural) expected explanations towards a more frequent use of referendums. Second, we introduce time-differencing QCA as an extension of conventional QCA based on cross-case comparison and set out our observational study design. Third, we conduct the analysis to identify multiple combinations of conditions that lead to a rise in referendums. Finally, we check the sensitivity and robustness of the results, especially the link between the solutions and the outcome by relaxing the analytical requirements of the initial result.

Referendums and the dynamics of democratic change

The literature on comparative political institutions sheds light on the use of referendums beyond the normative debate about the trade-off between direct and representative democracies, i.e., whether to maximize the leverage of direct voting or to reflect different voices in political participation (see LeDuc 2015). Specifically, the institutionalization of referendum use is empirically understood as an integrative part of the institutional arrangements in parliamentary democracies (direct democratic dimension, see Vatter 2009; Krisi 2015). Based on the growing importance of participatory procedures since the 1990s (Altman 2019), the direct democratic dimension, in which policy decisions are made without the mediation of representatives, is linked to the question of democratic innovation (Elstub and Escobar 2019). This research asks how parliamentary systems can be synchronized with inclusive political participation (e.g., Kern and Hooghe 2018; Rose and Weßels 2021).

Institutional arrangements of parliamentary systems have been primarily characterized by institutional connections of electoral systems and government formation (party-executive dimension, Lijphart 2012; Shugart and Taagepera 2017; Taagepera and Nemčok 2021). They have understood political representation from the bi-polar concept of simple and non-simple majoritarian types of parliamentary democracy. The latter, non-simple type, is commonly called the ‘consensus model’ and describes how power is shared, dispersed, and restrained in a variety of ways (Lijphart 2012: 33; see also Powell 2000; Bernauer and Vater 2019; Ganghof 2021; Bochsler and Juon 2021). However, the polar concepts do not exclude the existence of a ‘middle zone’. They are instead thought of as a continuum with the majoritarian type at one end. The literature on comparative political institutions provides us with two strategies to identify varieties in this continuum. First, diverse institutional arrangements that combine both majoritarian and non-majoritarian attributes can be investigated (Schmidt 2015; Ganghof 2021). Second, convergence can be evaluated through temporal changes of either simple or non-simple majoritarian arrangements toward the ‘middle zone’ (Armingeon 2004; Vatter et al. 2014; Magone 2016). These two strategies are not mutually exclusive. Many arrangements are assumed due to the existence of different forms of convergence, even though this study focuses primarily on democratic changes toward a more frequent referendum use.

Previous studies based on cross-case comparison have already suggested a generalizable relationship between types of institutional arrangements and the direct democratic dimension. They emphasize that the majoritarian nature of the party-executive dimension contributes to the use of referendums (Geissel and Michels 2018; Vospernik 2018; Hollander 2019; Qvortrup 2021). Although some micro-level studies have focused on attitudinal changes over time in support of referendums (e.g., Kern and Hooghe 2018; Rojon and Rijken 2021), less attention has been paid to studying how changes of institutional arrangements at the macro-level are connected to a more frequent use of referendums. Moreover, the results of such studies have not yet systematically analyzed the non-linear relationships of different combinations (configurations) between the international and domestic factors.

Our study is based on a macro-level configurational comparative approach integrating temporality (Verweij and Vis 2020). While acknowledging the contribution of institutional arrangements to the use of referendums, changing institutional arrangements are, at the same time, related to economic globalization and veto players in the decision-making process (Vatter et al. 2014). Referendum studies have suggested an increased use of referendums against the background of further European integration (Setälä 1999) in parallel with the argument of changing institutional arrangements (Bogdanor 1994). However, the growing literature on EU-related referendums (e.g., Hug 2002; Hobolt 2006; Closa 2007; Oppermann 2013; Prosser 2016) has argued that domestic factors such as institutional arrangements and veto players do not exclude European-level reasons such as economic globalization or Europeanization, and suggested that combinations of internal and external conditions are worth exploring further as a way of explaining the use of referendums. To provide an integrative understanding based on mutual complementation between the literature of comparative political institutions and referendum studies, the next section clarifies our analytical framework to explain the use of referendums.

Explaining the increase in referendums: an analytical framework

Before we examine the expected explanatory paths for the increase in referendums over time, we first define the outcome we seek to explain, i.e., change over time in the use of referendums. Hooghe and Marks (2008: 21) suggest that the Maastricht Treaty (signed in February 1992, effective 1 November 1993) was a turning point of European integration. Even though EU-related referendums first occurred in 1972 (Beach 2018), the treaty led to a complex elite bargain that facilitated referendums. The increased use of referendums in each country may be simply measured by comparing the frequency of popular votes before and after the Maastricht Treaty, but change is also assessed from how referendums are organized in a country. Therefore, we define changes in the use of referendums as the institutionalization of popular votes in the decision-making process (see Altman 2015). Subsequently, the temporal difference from our hypothesized point of change in 1993 (Maastricht Treaty comes into force), is represented by ΔREF with the following simple subtraction:

The idea of calculating ΔREF by comparing time points before and after 1993 in the same unit of analysis (i.e., country) is similar to focusing on time-variant conditions in statistical time series data analysis.Footnote 2 Comparative studies have suggested various time-invariant conditions for referendums, e.g., different histories of institutionalizing parliamentarism in countries like Switzerland, Austria, Portugal compared to the UK or the Benelux countries (Norton 2021: 92–93); the constitutional idea of democratic political participation and representation; or two-level games to maximize bargaining power or leverage in international negotiations based on country-specific resources (Hug 2002; Beach 2018). By analyzing time-variant conditions (i.e., conditions that change over time), we assess whether change leads to a temporal difference in the outcome (ΔREF). Even if the difference cannot be explained by individual time-variant conditions, our set-theoretical analysis allows for combinations with time-invariant conditions that are theoretically and empirically related to the time-variant condition. We will formalize these hypothetical combinations as detailed below.

Our focal time-variant condition can be described as changes of institutional arrangements that lead to a destabilization of political alignments in European parliamentary democracies (Bogdanor 1994; Closa 2007; Qvortrup 2018c, 2021: 38). Political developments that lead to an increase in political parties or to unconventional forms of government play a role in processes of convergence, which reduce the clear difference between institutional arrangements (Vatter et al. 2014). The ‘blurring’ of established political alignments in the dynamics of institutional arrangements may highlight the role of referendums in tackling issues beyond partisan calculus, such as politicizing referendums to weaken either governments or oppositions, or depoliticizing referendums to avoid the political costs within government parties (e.g., Oppermann 2013). However, this macro-level explanation does not exclude pressure from non-partisan considerations that might legitimize referendums based on the logic of appropriateness (Closa 2007; Mendez et al. 2014).

Explanations from the perspective of institutional convergence do not assume a one-way street, but rather go in both directions (Lijphart 2012: 252–253). The first direction is changes of the simple majoritarian type toward a more consensual type, which prioritizes proportional representation and can be described by CONV[1]. The second direction of change is from the consensus type toward the simple majoritarian type, represented by CONV[2]. Based on these two directions of change,Footnote 3 we can also define a state of no change from both types as CONV[0], or the negation of CONV[1]*CONV[2] using the set-theoretical AND operator (*). The hypothesized link of both types of convergence can be expressed as CONV[1] + CONV[2] → ΔREF by using the set-theoretical OR operator (+) and rightwards arrow (→).Footnote 4

However, external conditions like the (de)legitimization of European integration (EU) and the (dis)promotion of economic globalization (GLOB) can intersect with the internal change of institutional arrangements to explain the increased use of referendums. For one, the use of referendums can interact with the issue of sovereignty in the context of EU-level decision-making. Because of the Maastricht accession criteria, further European integration is (de)legitimized by referendums of each membership country (Setälä 1999). For another, economic globalization has opened channels to change established political institutions and its (dis)promotion is questioned by referendums, especially through references to the popular will (Rodrik 2021).

Although these two factors (EU, GLOB) can each facilitate referendums, they are not mutually exclusive. We thus represent the relationship by EU + GLOB using the set-theoretical operator OR ( +). Based on this insight, the interaction between the two types of convergence can be formalized as follows: (EU[1] + GLOB[1]) * (CONV[1] + CONV[2]). Here, EU membership (EU[1]) and economic globalization (GLOB[1]) are considered dichotomous conditions (i.e., conditions that can take on a value of true/1 or false/0).

The two types of convergence are also related to institutional veto players because of their theoretical link to the party-executive dimension in parliamentary systems (see Ganghof 2010). Fewer institutional veto players are expected to promote the change of institutional arrangements (Bernauer and Vatter 2019) and reduce complexity in reaching agreements on referendums, although some studies show that the influence of veto players is context-dependent (Hollander 2019). We consider the use of referendums as a strategic option to bypass veto players (Prosser 2016: 184).

These distinct functions of veto players are not contradictory when we take combinations with external conditions into account. In the literature on political-institutional convergence, veto players are often linked to economic globalization. Specifically, countries with less veto players are hypothesized to respond more to economic globalization and in this process, democratic convergence is expected (Vatter et al. 2014: 908). In parallel with the influence of EU membership, we thus express the combination of economic globalization and veto players set-theoretically as (GLOB[1]*VETO[0]) * (CONV[1] + CONV[2]), where veto players are formalized as a dichotomous condition. This conjunction is compatible with the situation in some European countries with a considerable number of veto players where referendums have grown in number against a background of increasing economic globalization. Specifically, we understand VETO[1]*GLOB[1] as an alternative explanation to the convergence hypothesis and set-theoretically construct the following hypothesized expectations: VETO[1]*GLOB[1] + (EU[1] + GLOB[1]*VETO[0]) * (CONV[1] + CONV[2]). These expectations toward referendum use can be further simplified as follows:

With the explanations derived from a simplification of these combinations, we can identify conjunctions of domestic and external conditions, namely either EU[1] or GLOB[1] (see Appendix 1.1 for details). Based on this analytical framework, the next section details time-differencing QCA as a tool to assess explanations for an increased use in referendums and clarify the observational study design.

Methodological notes on time-differencing QCA

Investigating convergence in the literature of comparative political institutions is useful to assess changes between given time points, but there are two different observational methods of convergence, namely difference-based observation (Armingeon 2004) and variance-based observation (Vatter et al. 2014). While the former compares the difference between more than two time points within a single unit (i.e., country), the latter compares the dispersion between more than two units within a single time point. Variance-based observation is proposed to control the between effects and the within effects in the statistical framework of generalized linear latent and mixed models (Bernauer and Vatter 2019). For our analysis, we use the difference-based method because of two reasons: First, variance is not a simple measure of interpreting each analytical unit’s movement from the previous to the following time point, although the convergence effect estimation may become more precise. Second, the variance calculated with the squared differences returns non-negative values. This can be useful to clarify convergence (= low variance) or divergence (= high variance), but it makes measurements of change in institutional arrangements difficult.

Like our focal time-variant condition CONV, the difference-based observation will also be applied to the outcome ΔREF. To assess the hypothetical link between observed differences, we use QCA instead of regression-based methods or case studies. Compared with quantitative methods, which are designed to specify interactions as an extension of estimating individual variables, QCA focuses on different combinations of conditions that explain the same outcome (Thiem et al. 2016). Conducting QCA in an incremental and iterative manner provides a systematic overview of insights from qualitative methods and can easily be combined with case studies (Schneider and Rohlfing 2019). Although there is no dominant methodological guideline in referendum studies (Qvortrup 2018b), these characteristics of QCA are well suited for our macro-comparative study because we aim to investigate multiple and conjunctional explanations for an increased use of referendums.

To investigate configurations of dynamics like convergence, we need to integrate temporality into the formal procedure of QCA (Verweij and Vis 2020). For this purpose, we employ time-differencing QCA, which was originally proposed as a technique of time series QCA (tsQCA) to extend QCA for modelling temporal dependencies that involve changes in a trend following a change point (Hino 2009).

Based on the analytical motivation to theorize the ‘before and after’, time-differencing QCA is designed to focus on time-variant conditions, although time-invariant conditions can also be considered. If we analyze a time-variant condition X within the same unit that is divided by two given time points, namely Xt+1 and Xt, the difference ΔX = Xt+1 − Xt describes whether the change of condition X is related to generating the outcome Y, while the difference of the outcome ΔY = Yt+1 − Yt in each unit specifies the change in outcome based on time-variant conditions. Moreover, taking a difference or differencing connotes a change point E between two given time points. The change point E allows us to trace a temporal change in property X causing a change in property Y. The causal link between ΔX and ΔY is then formalized as E*(ΔX) → E*(ΔY).

This type of causal inference using delta values does not conflict with the case-based nature of QCA (Ragin 1987), which is characterized by a back and forth between cross-case- and within-case-level analysis. It is instead related to the peculiarities and limitations of time differencing, which assumes comparable trajectories from the starting points in observed cases. Causal inference in time-differencing QCA can be uniquely assessed by the ‘difference between two differences’, often applied in the causal inference framework of quantitative methods.

For one, as an assessment of causal inconsistency (i.e., when a delta condition is associated with both change and no change), difference within time series is checked by whether E*ΔX[1] can be expected to generate E*ΔY[1] or not. For another, as an assessment of causal redundancy (i.e., when both the presence and absence of a delta condition is associated with change), inferences about a different outcome in E*ΔX[1] require difference with another time series that generates E*ΔX[0]. However, time-differencing QCA is currently limited to dichotomized (‘crisp set’) data (Hino 2009: 262), which require an alternative approach to assess the trichotomized condition ‘convergence’ that is represented by multiple values.Footnote 5 Therefore, we analyze set-theoretical differences through an extended rule of minimization (Dușa 2019: ch. 8). The procedure is as follows:

Formulas (3) and (4), which assess whether a change in the outcome is caused by a change in the conditions, are evaluated in a truth table analysis. Causal inconsistency is used to check whether ΔX[1] or ΔX[2] on ΔY[1] are discernible from ΔY[0] (Dușa 2019: 197–208). Formula (5), which assesses whether a change in the conditions is redundant for a change in the outcome, provides clues about the redundancy for sufficiency. Even if (3) and (4) are rejected, the observed changes that are redundant can be eliminated in the minimization procedure.

By using time-differencing QCA, this study investigates configurations of institutional convergence (CONV) to explain the increased use of referendums since the 1990s (ΔREF). We use cross-national data of 19 countries that are listed as OECD and/or EU member countries in the Comparative Political Data Set (CPDS; Armingeon et al. 2021) and which were already democratized in the 1970s (without Cyprus). In addition, we also employ empirical data of three non-European parliamentary systems (Australia, Canada, and New Zealand) to check extra-case influence. The CPDS is useful for calibrating our conditions (CONV, VETO, EU, GLOB) in the 19 + 3 countries, but the related index of referendum use only goes back to the 1990s. Therefore, as detailed below, we compensate for missing information using the Varieties of Democracy (V-DEM) dataset, version 11.1 (Altman 2015, 2019).

The reference point to compare temporal changes since the 1990s is constructed from the data of 1970–1989 in each country, in which the use of referendums gradually increased in connection with European integration. We compare this to the period until the 1980s and the following period since the 1990s. However, observational changes since the 1990s are not monotonic and show gradual changes. Therefore, the panel data from 1990 to 2019 is partitioned along three temporal dimensions, the 1990s (1990–1999), the 2000s (2000–2009), and the 2010s (2010–2019).Footnote 6 In sum, we investigate differences in the three periods of 19 + 3 countries (i.e., 57 + 9 cases) in comparison with the previous 1970 to 1989 period.

Based on the observational study design using time-differencing QCA, in the following section we conduct an empirical analysis that consists of various set-theoretical procedures, especially data calibration and logical minimization.

Calibration

Calibration is a procedure that converts raw data to set data through set membership scores for conditions and outcomes in each case, thus roughly corresponding to what is often called ‘operationalization’ when other methods of analysis are used. Calibration is a necessary step to prepare further analysis or the so-called ‘analytical moment’ in QCA. Meanwhile, set data requires membership scores, which cannot be assigned without theoretical and/or empirical knowledge (Oana et al. 2021: 31). The calibration procedures are summarized in Table 1.

Calibrating the outcome (ΔREF)

First, raw data for the outcome is based on the direct popular vote index (Altman 2015) that addresses to what extent the direct popular vote is put into practice, and it is measured in a range from 0.0 to 1.0 (for details, see Appendix 2.1). In our observations, the scores of Switzerland from 1970 to 2019 are always higher than 0.60. In contrast, the scores of other European countries never reach a score of 0.50. As an extreme case, Germany is assigned a score of 0.01 from 1970 to 2019. This lowest possible non-zero score means that the use of referendums is only weakly institutionalized despite not being fully excluded.

Relying on this index, temporal changes in the use of referendums (ΔREF) in each country are calibrated by calculating the temporal difference between a reference time point from the 1970–1989 period and the subsequent time points from the data of 1990 to 2019. The anchor point for temporal change is based on whether we can observe a difference or not. This process includes three steps:

First, we set a reference point by calculating the geometric mean (and not the minimum values) of the index scores from 1970 to 1989 in each country.Footnote 7 The geometric mean is used because referendum use had already increased before the 1990s, and thus to avoid overestimating the difference between our reference point (1970–1989) and the subsequent time periods. Second, we calculate raw scores of the index per country in the three subsequent periods (the 1990s, the 2000s, and the 2010s). While maximum values could be considered for calibration, this might lead to an overestimation of temporal differences, which is why we use average scores. Third, we subtract the geometric mean of the 1970–1989 period from the average scores from the periods from 1993 to 2019. Subsequently, we assign a set membership score of 1 if the observed difference is positive, indicating an increased use of referendums, and otherwise 0.

Calibrating political-institutional convergence (CONV)

Second, as raw data for our focal condition, we use the variable for institutional arrangements from the database by Armingeon et al. (2021), measured based on four indices of the party-executive dimension. The variable is constructed by calculating the sum of moving averages over the decade of the four indices with z-standardization across units for each time point. In each time point, either a negative value for the simple majoritarian type or a positive value for the non-simple majoritarian type based on the value of 0 is calculated (for details, see Appendix 2.2).

As for the outcome (ΔREF), we calibrate institutional convergence by measuring whether we can observe a difference in each country. However, the raw data of the condition can take on multiple (including negative) values, namely CONV[0], CONV[1], and CONV[2]. Therefore, we calibrate the condition in three steps by differentiating between a reference time point and the following time points:

First, to set a reference point for identifying temporal change, we do not use ideal scores represented by the minimum or maximum values in the initial period (1970–1989) per country. This is because the ideal or ‘best shot’ (Goertz 2020: 177) scores involve the risk of misconceiving institutional arrangements due to outliers and ignoring trends of change before the 1990s. We thus use a modified version, i.e., the minimum (maximum) score of either the average score of the 1970s (1970–1979) or the 1980s (1980–1989), if the average score from 1970 to 1989 was scored as negative (positive).Footnote 8 Second, average scores of the three subsequent periods (the 1990s, the 2000s, and the 2010s) are divided based on the modified score from above.Footnote 9 Then we assign the value of 1 if the ratio is larger than 1.0 (i.e., in the case of convergence toward the ‘middle zone’ from the initial period), and otherwise 0 if the ratio is smaller than 1.0. Third, the binary values are differentiated through multi-value scaling. Specifically, we assign the value of 1 (CONV[1]) to convergence from the simple majoritarian type and the value of 2 (CONV[2]) for convergence from the non-simple majoritarian type. No convergence (CONV[0]) is coded as 0.

Calibrating other conditions (EU, VETO, GLOB)

We also construct set data of the remaining three conditions (EU, VETO, and GLOB). First, the condition ‘EU’ is based on whether a country is an EU member or not. Therefore, a value of 1 (EU[1]) is given to observations in each country that joined the EU in the 1990s (1990–1999), the 2000s (2000–2009), or the 2010s (2010–2019), and otherwise a value of 0 (EU[0]; see Armingeon et al. 2021).

Second, the number of veto players (VETO) is calibrated by whether each country has a federal bicameral structure or not (Armingeon et al. 2021). Bicameralism strongly affects institutional veto players and is thus hypothesized as a cause of referendums (e.g., Prosser 2016), while federalism can be considered an institutional hurdle for the use of referendums (e.g., Mendez et al. 2014). Although cases of non-federal bicameralism can be observed (see Appendix 2.3), we use the minimum value or ‘weakest link’ (Goertz 2020: 177) of given institutional arrangements, i.e., federal AND bicameral structure as an indicator that avoids overestimating VETO[1].

Third, the condition of GLOB is dichotomized through statistical cluster analysis. Based on averaged total trade scores in each country from 1970 to 1989 (Armingeon et al. 2021), we measure whether countries were already economically globalized. We expect that the different initial settings influence the difference between countries of how economic openness has accelerated since the 1990s. As a result of the clustering, we can identify the anchor for dichotomization based on an empirical gap around 60.0 (see Appendix 2.4), with the threshold between Sweden (54.0) and Austria (61.0). This is theoretically justified considering flexible adjustments of European small states to economic openness (Katzenstein 1985; Rodrik 2011).

Truth table analysis and minimization

Based on the calibration, we check the logical necessity of each condition as per methodological recommendations prior to conducting the truth table analysis (Oana et al. 2021: 133–134). The result suggests that no condition is logically necessary because no ‘consistency’ scoreFootnote 10 reaches the value of 0.9 required for necessity (see Appendix 3). Consequently, we build the following truth table, i.e., a structured table that presents all logically possible combinations of our four conditions with their truth values and the corresponding outcome values:

The truth table reveals 14 empirical patterns in the 19 European democracies from the possible 24 configurations (see also Appendix 1.1). First, we can infer positive changes in the outcome (ΔREF[1]) within each configuration from the consistency scores that are shown as ‘incl’ in Table 2. If we do not observe any changes (i.e., no increased use of referendums) negative outcomes (ΔREF[0]) in a truth table row (i.e., a distinct, logically possible configuration of conditions), the consistency scores will be lower than 1. No general threshold of consistency scores exists, but scores below 0.75 are seen as problematic (Oana et al. 2021: 92). Although this benchmark should not be applied automatically, we evaluate that configurations in rows 8 to 14 are closer to a ‘no positive change’ outcome than the other rows. This is because the rows expected to have a positive outcome (ΔREF[1]) below a score of 0.67 have the same degree of consistency as rows 8, 10, and 11, which do not satisfy expectation (2).

However, we still predict positive outcomes in rows 9 and 12, which include CONV[1], even though the single-period cases observed in Malta (MAL1990) and France (FRA1990) do not provide cues on whether a temporal change that generates a positive outcome can be expected. For example, the Netherlands in the 1990s and 2000s periods is part of row 7, but the cases have different outcomes. In the Netherlands, which has not held a nation-wide referendum until 2005, referendums on the European treaties and introduction of the Euro were already discussed in the 1990s especially by opposition parties, though the related constitutional amendment failed in 1999. However, the Dutch parliament has called for referendums since the 2000s with the rise of a new right-wing party that showed dissatisfaction with several policies and institutions, among them the EU. The first nation-wide referendum was realized in 2005 on the European Constitution (Hollander 2019; Qvortrup 2021). This brief illustration suggests that different outcomes within each country can be evaluated as a temporal change from a negative to a positive outcome.

Based on the truth table analysis, minimization is conducted next. If we use only rows (i.e., logically possible combinations of conditions) with empirical cases for minimization, the result is called ‘conservative solution’ (Oana et al. 2021: 123–125). However, minimization can also include truth table rows without empirical cases assigned to them, so-called ‘logical remainders’. In your analysis, 10 out of 24 possible configurations are logical remainders. Including them in the minimization process produces a more parsimonious solution (rows 15 to 24 in Table 2).

When we simplify the configurations linked with a positive outcome based on both rows with empirical observations and theoretically viable logical remainders, the result will be more parsimonious than the conservative solution. In general, inferences about logical remainders in the minimization procedure requires careful consideration as to whether these configurations are expected to generate a positive outcome. For our truth table, assessing the redundancy for sufficiency becomes more rigorous by using the logical remainder rows 20, 23, and 24 for minimization. However, the three remainders still predict an increase in referendums as per expectation (2). The resulting solution is called ‘enhanced parsimonious solution’ (Dușa 2019: 190–192) because it includes theoretically meaningful truth table rows without empirical cases. The result is as follows:

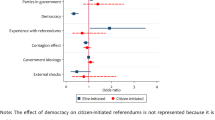

Table 3 shows three separate explanations of temporal changes in the use of referendums. First, we find VETO[1]*GLOB[1] as an alternative to our convergence hypothesis (CONV). The unique cases of Switzerland (SWI1990, 2000, 2010), which cannot be explained by other paths, show that referendums are used to bypass veto players. Specifically, the use of referendums increases despite a high number of veto players in a highly globalized country, even though there is no shift toward the majoritarian type in Switzerland since the 1990s (see Vatter 2016).

Second, we confirm that EU[1] combined with convergence toward more majoritarianism (CONV[2]) is a logically consistent path to increased referendum use. For one, the case of Belgium (BEL1990 and 2000) is not unique. It indicates that the Belgian constitutional provision set up in 1993 for popular votes (non-binding and at the local level) can be explained not only by changes in the party-executive dimension, but also by a formal change to a federal structure in a globalized context. For another, the case of Italy (ITA2000, 2010) provides insights on majoritarian dynamics, in which the proportional representation system has been changed by political reforms in the 1990s period. The result suggests that convergence toward majoritarianism (CONV[2]) with European Integration (EU[1]) has better empirical support than the hypothesized combination with economic globalization (GLOB[1]).

Third, we confirm another dynamic from the combination of CONV[1], EU[1], and GLOB[1]. The case of Austria (AUT1990, 2000, 2010) exemplifies a shift from a simple majoritarian type towards the ‘middle zone’ based on the rise of a right-wing party. Although Austria can be considered a non-majoritarian country (Lijphart 2012: 95, 244), it can also be explained by its federal structure in a highly globalized context. Therefore, it does not constitute a unique example of the dynamics of convergence. In contrast, the case of Ireland (Ireland 1990, 2000, 2010) is understood as a typical case of convergence toward the ‘middle zone’ from the simple majoritarian type (Vatter et al. 2014). The use of referendums is common in Ireland—there were 35 referendums from 1970 to 1989 (Hollander 2019). However, a gradual increase in referendums can be observed since 1990, e.g., the popular vote to ratify the 2012 European Fiscal Compact during the financial crisis. Partly contrary to our own expectation, convergence toward the non-majoritarian type (CONV[1]) with either EU[1] or GLOB[1]) is empirically not sufficient in the case of Ireland, but both external conditions are a necessary part of explaining the outcome.

Sensitivity check

In this section, we assess whether the solution is connected to the outcome in a stable manner by relaxing the analytical requirements of the initial result and comparing different models. Specifically, we compare results of the following four datasets: (A) baseline dataset, (B) generalized dataset, (C) lagged baseline dataset, and (D) lagged generalized dataset. First, the baseline dataset (A) is constructed by using the same 19 European countries. Second, the generalized dataset (B) is constructed with the 19 European countries and three non-European countries (Australia, Canada, and New Zealand). In the lagged datasets (C) and (D), we assess whether configurations of each condition in the 1990s (2000s) could generate positive outcomes in the 2000s (2010s).

In each dataset, we assess the result of the previous section with the initial settings (I) and with three alternatives (II), (III), and (IV). These relax the minimum or maximum value assumptions of the differencing procedures of CONV and ΔREF as follows. For (II), the aggregation method for the period 1970–1989 is changed to the simple arithmetic mean and we take the difference between the average of the 1970–1989 period in each country and the averages for the three periods in the 1990s (1990–1999), the 2000s (2000–2009), and the 2010s (2010–2019). For (III), we set a different change point (III) in which the previous observations are aggregated from 1970 to 1985 (before the Single European Act), and the following observations are aggregated from 1993 (after the Maastricht Treaty). For (IV), we apply the changes from both (II) and (III) at the same time.

From the four datasets and the alternative calibrations, we can compare the new results with the initial solution. To illustrate the sensitivity check, we take the result from the lagged generalized dataset (D)-(IV) because it introduces greater changes compared to the other datasets. As with the initial analysis based on (A)-(I), we build a truth table after calibration. The result is as follows:

Table 4 shows possible configurations based on the dataset (D)-(IV). First, we can confirm that configurations of the additional countries (AUL, CAN, NZ) are not mixed with other European countries. While the case of New Zealand in row 4 can be understood as an alternative case for referendum increase, the cases of Australia and Canada in row 9 have different outcomes, indicating that different configurations are required to explain non-European countries.

Second, we observe case movement in the truth table. Specifically, the case of Belgium (BEL) is now part of a different configuration compared to the initial results (see Table 2), though the same positive outcome is observed. In contrast, row 11 contains the case of Austria (AUT) with an indeterminate consistency score of 0.50, although this case is now part of the same combination of conditions as row 3.

Third, the lagged explanation in each country alters the configurational patterns. Compared with Table 2, the cases of Luxemburg (LUX) and Denmark (DEN) in row 2 are consistent with a positive outcome. In contrast, row 7, which includes the Netherlands (NET) and Denmark (DEN) with a score 0.75 in the initial results, is now an unclear configuration of referendum increase with a consistency score of 0.67. While a positive outcome may be derived from expectation (2), it is difficult to assume a positive outcome from the single-period case of Denmark (DEN2000) compared to two Dutch cases (NET1990, 2000).

Whether these changes have an influence on the minimization process is assessed with other robust cases that show the same configurations and directions as Table 2. For one, a positive robust outcome is observed in the cases of Finland (FIN), Italy (ITA), and Portugal (POR) in row 1, in Ireland (IRE) and Malta (MAL) in row 3, and in Switzerland (SWI) in row 5. For another, rows 8, 10, 12, 13, and 14 have consistency scores below 0.50, which suggests that these configurations are not sufficient for temporal changes of referendum use (see Table 2). From Table 4, we derive a minimized solution by setting the same consistency score threshold as in the initial analysis (i.e., scores over 0.75) and using only theoretically meaningful logical remainders (see the notes on Tables 3 and 5). The result is as follows:

The minimization result is not identical with the initial solution from Table 3. The first path explaining Luxemburg (LUX), which consists of external reasons without institutional convergence since the 1990s period (EU[1]*GLOB[1]*CONV[0]), is understood as an unexpected path based on expectation (2). The path provides an empirical clue about the theoretical implication that internalizing EU treaties and economic globalization (EU[1]*GLOB[1]) can legitimize referendums based on the logic of appropriateness (e.g., Morel 2007; Oppermann 2013; Mendez et al. 2014).

The second path is derived from a non-European country. Specifically, we find VETO[0]*EU[0]*GLOB[0]*CONV[1] in New Zealand (NZ), where the use of referendums increased in the 1990s period against the background of an electoral reform introducing a proportional representation system (Qvortrup 2021). The result implies that institutionalizing direct democratic procedures can be an additional tool of political participation in the shift away from the established majoritarian type of parliamentarism.

In the other four paths, we find the same combinatorial characteristics as in the three paths from Table 3, although additional conditions are included in each configuration. The combinations from the initial solution (EU[1]*CONV[2], EU[1]*GLOB[1]*CONV[1], and VETO[1]*GLOB[1]) are set-theoretically understood as part of the so-called ‘robust core’ (see Oana et al. 2021: 146–147). In the analysis of Table 5, the three combinations from the initial solution are confirmed, even if we consider two different models (M1 and M2).Footnote 11

As with the sensitivity check in dataset (D)-(IV), each explanation has a stable link with the outcome if the three initial combinations are included in the models based on a consistency threshold of 0.75 and use the same remainders as before. By using (A)-(II) to (D)-(IV), we can derive 21 different models (see Appendix 4.1). We can empirically confirm that VETO[1]*GLOB[1] and EU[2]*CONV[2] in the initial solution has a stable link with the outcome. In comparison with these paths, GLOB[1]*EU[1]*CONV[1] cannot always be recovered in the models. Specifically, it did not appear in the analyses of the lagged datasets.

Our results confirm studies that focus on simple majoritarian dynamics for explaining the increase in referendum use (Vospernik 2018; Hollander 2019; Qvortrup 2021). While the lagged models are not useful for considering simultaneous temporal changes between time-variant conditions and the outcome, the implied changes from these models provide a source to assess the breadth of possibilities to generate the outcome. Although convergence toward the more consensual type provides a general explanatory component valid beyond European countries based on the case of New Zealand (see Table 5), the temporal dynamics for increased referendum use would be different. In sum, while the two types of convergence show different causal properties in the empirical analysis, the result still implies that the configurations of both types could generate dynamics toward an increased use of referendums.

The sensitivity check leaves room for further assessment: First, we focus on the temporal dynamics of referendums at the national level, but distinct types of referendums and/or referendums at different levels should be also assessed. Second, we uncover multiple conjunctural paths with an extension of time-differencing QCA for employing multi-values. In general, multi-value QCA is useful to identify discrete patterns, but integrating fuzzy sets and combining in-depth case studies would provide a way to enhance causal inference of the underlying mechanisms. Third, based on the cases of Australia, Canada, and New Zealand, further assessments of increased referendum use should not be confined to Western countries. Thus, Central and Eastern European countries as well as presidential systems like Latin American countries could also be investigated.

Concluding remarks

This study assesses the dynamics of democratic change in relation to an increased use of referendums in European parliamentary democracies. Our major findings are the following: First, we find that democratic changes of institutional arrangements create multiple paths to explain an increased referendum use. Second, our results suggest that the explanation with simple majoritarian dynamics holds up compared to other explanations based on convergence toward consensual type. Third, many veto players combined with economic globalization is identified as an alternative explanation for an increase in referendums, which adds a new perspective to the debate on the broad dynamics of European integration and the ‘new intergovernmentalism’ (Bickerton et al. 2015). This implies that democratic changes in European parliamentary democracies cannot be ignored as an explanation of the use of referendums, while both convergence types—toward simple majoritarianism and toward consensual democracy—are individually neither necessary nor sufficient conditions and may have different causal properties.

This macro-level study uses the novel method of time-differencing QCA to advance research on referendums in European countries by elucidating the neglected combination of economic globalization and a high number of veto players. The configurational comparative approach to assess temporal changes suggests that the increased use of referendums cannot simply be explained by majoritarian dynamics (Vospernik 2018). For one, our findings imply that more attention should be paid to the conjunctural nature of referendums in parliamentary democracies, which is characterized by complexity that goes beyond the influence of individual factors. For another, our finding that changes in institutional arrangements relate to EU membership and/or globalization leaves room to investigate the question of temporal trajectories to transform the decision-making process considering the EU’s democratic deficit. It provides a new venue to address the puzzle of democratic innovation, specifically how inclusive political participation using referendums evolves (or not) from changing parliamentary systems.

Data availability

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available in the article and its supplementary materials (provided online alongside the article).

Notes

Based on the set theoretical notion in which symmetrical relationships are not required, QCA is designed to identify disjunctive configurations for the same outcome constructed by conjunctive conditions (Oana et al 2021).

If time-invariant conditions (i.e., conditions that do not change over time) are constant in our analysis, we expect that the logically possible combinations exceed the number of empirical cases (so-called ‘limited diversity’). Reducing high levels of limited empirical diversity is recommended when the number of potentially relevant conditions is large (Oana et al 2021: 213).

Strictly speaking, INUS conditions are investigated, i.e., insufficient but necessary parts of an unnecessary but sufficient condition (Dușa, 2019: 125).

While the relationship between multi-value QCA and set theory is not fully understood yet, we assume that it can be grounded in set theory and seen as an integral part of QCA (see Dușa, 2019).

As the geometric mean cannot be assessed based on zero values, we modify the lowest value of 0 to 0.0055, which is derived from splitting the second lowest score of 0.011 (the case of Germany).

Negative values cannot be assessed easily based on the geometric mean, which is why we apply a different method to set the reference point. Analytical robustness measures of the modified average scores will be checked by changing to a simple arithmetic mean during the sensitivity check.

This is used to identify differences in the condition ranging from negative to positive values (see Appendix 2.2).

Consistency is an important quality measure of QCA and describes how consistent the necessity/sufficiency relationship between (combinations of) conditions and the outcome is (Schneider and Wagemann 2012: ch. 5.1). It is thus related to the number of cases that deviate from necessity or sufficiency relationships.

The model ambiguity is caused by logically equivalent terms to find a comprehensive solution in the minimization process.

References

Altman, D. 2014. Direct Democracy Worldwide. Cambridge University Press.

Altman, D. 2015. Measuring the Potential of Direct Democracy Around the World (1900–2014). V-Dem Working Paper 17.

Altman, D. 2019. Citizenship and Contemporary Direct Democracy. Cambridge University Press.

Armingeon, K. 2004. Institutional Change in OECD Democracies, 1970–2000. Comparative European Politics 2: 212–238.

Armingeon, K., S. Engler, and L. Leemann. 2021. Comparative Political Data Set 1960–2019. University of Zurich.

Beach, D. 2018. Referendums in the European Union. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228637.013.503.

Bernauer, J., and A. Vatter. 2019. Power Diffusion and Democracy. Cambridge University Press.

Bickerton, C.J., D. Hodson, and U. Puetter. 2015. The New Intergovernmentalism: European Integration in the Post-Maastricht Era. Journal of Common Market Studies 53: 703–722.

Bochsler, D., and A. Juon. 2021. Power-Sharing and the Quality of Democracy. European Political Science Review 13: 411–430.

Bogdanor, V. 1994. Western Europe. In Referendums Around the World, ed. D. Butler and A. Ranney. Macmillan.

Closa, C. 2007. Why Convene Referendums? Journal of European Public Policy 14 (8): 1311–1332.

Dușa, A. 2019. QCA with R. Springer.

Elstub, S. and Escobar, O. (2019) Defining and Typologising Democratic Innovations. In: ibid (eds.) Handbook of Democratic Innovation and Governance. Edward Elgar Publishing.

Ganghof, S. 2010. Democratic Inclusiveness. British Journal of Political Science 40: 679–692.

Ganghof, S. 2021. Beyond Presidentialism and Parliamentarism. Oxford University Press.

Geissel, B., and A. Michels. 2018. Participatory Developments in Majoritarian and Consensus Democracies. Representation 54 (2): 129–146.

Gherghina, S., and N. Silagadze. 2020. Populists and Referendums in Europe. The Political Quarterly 91 (4): 795–805.

Goertz, G. 2020. Social Science Concepts and Measurement. Princeton University Press.

Hino, A. 2009. Time-Series QCA. Sociological Theory and Methods 24 (2): 247–265.

Hobolt, S.B. 2006. Direct Democracy and European Integration. Journal of European Public Policy 13 (1): 153–166.

Hollander, S. 2019. The Politics of Referendum Use in European Democracies. Palgrave Macmillan.

Hooghe, L., and G. Marks. 2008. A Postfunctionalist Theory of European Integration. British Journal of Political Science 39: 1–23.

Hug, S. 2002. Voices of Europe. Rowman & Littlefield.

Katzenstein, P.J. 1985. Small States in World Markets. Cornell University Press.

Kern, A., and M. Hooghe. 2018. The Effect of Direct Democracy on the Social Stratification of Political Participation. Comparative European Politics 16: 724–744.

Krisi, H. 2015. Varieties of Democracy. In Complex Democracy, ed. V. Schneider and B. Eberlein. Springer.

LeDuc, L. 2015. Referendums and Deliberative Democracy. Electoral Studies 38: 139–148.

Lijphart, A. 2012. Patterns of Democracy. Yale University Press.

Norton, P. 2021. Referendums and Parliaments. In The Palgrave Handbook of European Referendums, ed. J. Smith. Palgrave Macmillan.

Mahoney, J. 2021. Logic of Social Science. Princeton University Press.

Magone, J. 2016. The Statecraft of Consensus Democracies in a Turbulent World. Routledge.

Mendez, F., M. Mendez, and V. Triga. 2014. Referendums and the European Union. Cambridge University Press.

Morel, L. 2007. The Rise of ‘Politically Obligatory’ Referendums. West European Politics 30 (5): 1041–1067.

Oana, I.-E., C.Q. Schneider, and E. Thomann. 2021. Qualitative Comparative Analysis Using R. Cambridge University Press.

Oppermann, K. 2013. The Politics of Discretionary Government Commitments to European Integration Referendums. Journal of European Public Policy 20 (5): 684–701.

Pagliarin, S., and L. Gerrits. 2020. Trajectory-based Qualitative Comparative Analysis. Methodological. Innovations 13 (3): 1–11.

Penadés, A., and S. Velasco. 2022. Plebiscites. European Political Science Review 14: 74–93.

Penadés, A., and S. Velasco. 2024. The Effect of Referendums on Autocratic Survival. Government and Opposition 59: 405–424.

Powell, G.B. 2000. Elections as Instruments of Democracy. Yale University Press.

Prosser, C. 2016. Calling European Union Treaty Referendums. Political Studies 64 (1): 182–199.

Qvortrup, M. 2018a. The Paradox of Direct Democracy and Elite Accommodation. In Consociationalism and Power-Sharing in Europe, ed. M. Jakala, D. Kuzu, and M. Qvortrup. Palgrave Macmillan.

Qvortrup, M. 2018b. Methodological Issues. In The Routledge Handbook to Referendums and Direct Democracy, ed. L. Morel and M. Qvortrup. Routledge.

Qvortrup, M. 2018c. Western Europe. In Referendums Around the World, ed. M. Qvortrup. Palgrave Macmillan.

Qvortrup, M. 2021. Democracy on Demand. Manchester University Press.

Ragin, C.C. 1987. The Comparative Method. University of California Press.

Rodrik, D. 2011. The Globalization Paradox. W. W. Norton.

Rodrik, D. 2021. Why Does Globalization Fuel Populism? Annual Review of Economics 13: 133–170.

Rojon, S., and A. Rijken. 2021. Referendums. Comparative European. Politics 19: 49–76.

Rose, R., and B. Weßels. 2021. Do Populist Values or Civic Values Drive Support for Referendums in Europe? European Journal of Political Research 60: 359–375.

Schmidt, M.G. 2015. The Four Worlds of Democracy. In Complex Democracy, ed. V. Schneider and B. Eberlein. Springer.

Schneider, C.Q., and C. Wagemann. 2012. Set-Theoretic Methods for the Social Sciences: A Guide to Qualitative Comparative Analysis. Cambridge University Press.

Shugart, M.S., and R. Taagepera. 2017. Votes from Seats. Cambridge University Press.

Silagadze, N., and S. Gherghina. 2018. When who and how matter. Comparative European Politics 16: 905–922.

Smith, J., ed. 2021. The Palgrave Handbook of European Referendums. Palgrave Macmillan.

Setälä, M. 1999. Referendums in Western Europe. Scandinavian Political Studies 22 (4): 327–340.

Taagepera, R., and M. Nemčok. 2021. Majoritarian and consensual democracies. Party Politics 27 (3): 393–406.

Thiem, A., M. Baumgartner, and B. Bol. 2016. Still Lost in Translation! Comparative Political Studies 49 (6): 742–774.

Vatter, A. 2009. Lijphart Expanded. European Political Science Review 1 (1): 125–154.

Vatter, A., M. Flinders, and J. Bernauer. 2014. A Global Trend Toward Democratic Convergence? Comparative Political Studies 47 (6): 903–929.

Vatter, A. 2016. Switzerland on the Road from a Consociational to a Centrifugal Democracy? Swiss Political Science Review 22 (1): 59–74.

Verweij, S., and B. Vis. 2020. Three Strategies to Track Configurations Over Time with Qualitative Comparative Analysis. European Political Science Review 13 (1): 95–111.

Vospernik, S. 2018. Referendums and Consensus Democracy. In The Routledge Handbook to Referendums and Direct Democracy, ed. L. Morel and M. Qvortrup. Routledge.

Acknowledgements

Sho Niikawa’s work was supported by grants of the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS): Grant-in-Aid for Early-Career Scientists (project number 22K13329) and Grant-in-Aid for Challenging Research (Pioneering) (project number 23K17283).

Andreas Corcaci’s work was co-funded by the European Union under grant agreement ID 101105696. Views and opinions expressed are however those of the author only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or the European Research Executive Agency. Neither the European Union nor the granting authority can be held responsible for them.

Funding

Open Access funding provided by Kobe University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

None.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Niikawa, S., Corcaci, A. Referendums and political-institutional convergence in European democracies: A time-differencing configurational analysis. Comp Eur Polit (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41295-024-00396-2

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41295-024-00396-2