Abstract

How ready were governments and the public to sacrifice thousands of lives to avoid economic collapse during the pandemic? We designed a trade-off scale measuring whether the French population is more concerned with the health or economic consequences of the pandemic and administered it eight times from April 2020 to April 2021. We find that concern for the economy was correlated with a preference for the application of a free-market logic, and that it grew swiftly over time and uniformly across the population despite the unprecedented epidemiological circumstances. Absolute differences in concerns correlated with material factors after the first lockdown, and with self-perceived risk of Covid-19 infection and especially political orientation consistently over the year. Respondents who were old, wealthy, highly educated, at low risk of infection, and on the political right were more concerned for the economy than their counterparts. Older respondents’ strong adherence to the free-market logic seems to explain why economic concerns were more important among the group with the highest mortality rate. When political stance is interacted with material factors, marked divisions emerge among the wealthy, the highly educated, and especially the young depending on their political orientation from left to right. We employ insights from Polanyi and Gramsci to interpret these divisions as the potential build-up of a ‘double movement’ around the predominance of the free-market logic in the public’s ‘common sense’.

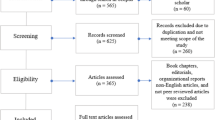

Source: Coping with Covid-19, Waves 1–8 (Recchi et al. 2021)

Source: Coping with Covid-19, Waves 1–8 (Recchi et al., 2021)

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

For a measurement of ‘individual free-market mentality’ across different countries, see Czeglédi and Newland, 2018. Liberal countries like the USA top the ranking.

ISCO is grouped into 9 non-ordinal categories in the following order: legislators, senior officials and managers; professionals; technicians and associate professionals; clerks (routine); service workers, and shop and market sales workers; skilled agricultural and fishery workers; craft and related trade workers; plant and machine operators and assemblers; elementary occupations. The EGP social class scheme contains 5 non-ordinal categories: the salariat; petit bourgeoisie; farmers; skilled workers; non-skilled workers. The Oesch scheme contains 8 non-ordinal categories: large employers and employed professionals; small business owners; technical (semi-) professionals; production workers; (associate) managers; office clerks; sociocultural (semi-) professionals; service workers.

Income and wealth are highly collinear. Hence, we tested our models including either income or wealth, and report the models with wealth here because it is a stronger predictor for concern for health versus the economy. The additional models that include income are available upon request.

We do not consider those who report suspected infection but who do not report a positive test in this category because testing became widely available and free after the first lockdown. Although this means cases are likely to be undercounted in the first waves of our survey, this reflects the global trend of early undercounting due to a lack of available tests.

Moreover, the two concerns on the barometer remained quite balanced over the period. Our barometer had a mean value of 5.22 across all waves; for a full account of descriptive statistics for our covariates, see Table 1.

Available upon request.

We cannot rule out the possibility that some individuals may have worried about the absence of production without adhering to a free-market logic.

References

Abramowitz, A., and K. Saunders. 2008. Is Polarization a Myth? The Journal of Politics 70: 542–555.

Alsan, M., L. Braghieri, S. Eichmeyer, M. Kim, S. Stantcheva, and D. Yang. 2020. Civil Liberties in Times of Crisis (No. w27972). NBER.

Amable, B. 2017. Structural Crisis and Institutional Change in Modern Capitalism: French Capitalism in Transition. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Ares, M., R. Bürgisser, and S. Häusermann. 2021. Attitudinal Polarization Towards the Redistributive Role of the State in the Wake of the COVID 19 Crisis. Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties 31: 41–55.

Armingeon, K., C. de la Porte, E. Heins, and S. Sacchi. 2022. Voices From the Past: Economic and Political Vulnerabilities in the Making of Next Generation EU. Comparative European Politics 20: 144–165.

Aum, S., S. Lee, and Y. Shin. 2020. Inequality of Fear and Self-Quarantine: Is There a Trade-off between GDP and Public Health? (No. w27100). NBER.

Bansak, K., M. Bechtel, and Y. Margalit. 2021. Why Austerity? The Mass Politics of a Contested Policy. American Political Science Review 115: 486–505.

Barrios, J. and Y. Hochberg. 2020. Risk Perception Through the Lens of Politics in the Time of the COVID-19 Pandemic (No. w27008). NBER.

Bayrou, F. 2021. Dette : « Nous ne pouvons pas laisser la France dans la situation où elle est ». France Info.

Bell, D. 1960. The End of Ideology. New York, NY: Glencoe Free Press.

Benoît, C., and C. Hay. 2022. The Antinomies of Sovereigntism, Statism and Liberalism in European Democratic Responses to the COVID-19 crisis: A Comparison of Britain and France. Comparative European Politics 20: 390–410.

Bethlehem, J. 2008. Representativity of Web surveys - An illusion? In: I. Stoop and M. Wittenberg (eds.) Access panels and online research, panacea or pitfall? proceedings of the DANS symposium. Amsterdam: Aksant, pp. 19–44.

Block, F. 2008. Polanyi’s Double Movement and the Reconstruction of Critical Theory. Interventions Économiques 38: 1–16.

Block, F., and M. Somers. 2014. The Power of Market Fundamentalism. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Blyth, M. 2013. Austerity: The History of a Dangerous Idea. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Brown-Iannuzzi, J., K. Lundberg, A. Kay, and B. Payne. 2015. Subjective Status Shapes Political Preferences. Psychological Science 26: 15–26.

Bruine de Bruin, W., H. Saw, and D. Goldman. 2020. Political Polarization in US Residents’ COVID-19 Risk Perceptions, Policy Preferences, and Protective Behaviors. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty 61: 177–194.

Burawoy, M. 2003. For a Sociological Marxism: The Complementary Convergence of Antonio Gramsci and Karl Polanyi. Politics and Society 31 (2): 193–261.

Cafruny, A., and M. Ryner. 2007. Europe at Bay. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner.

Campbell, J., and O. Pedersen, eds. 2002. The Rise of Neoliberalism and Institutional Analysis. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Chorus, C., E. Sandorf, and N. Mouter. 2020. Diabolical Dilemmas of COVID-19. PLoS ONE 15 (9): e0238683.

Clegg, D. 2022. A More Liberal France, a More Social Europe? Macron, Two-Level Reformism and the COVID-19 Crisis. Comparative European Politics 20: 184–200.

Clift, B. 2012. Comparative Capitalisms, Ideational Political Economy and French Post-Dirigiste Responses to the Global Financial Crisis. New Political Economy 17: 565–590.

Clift, B., and S. McDaniel. 2017. Is this crisis of French Socialism Different? Modern & Contemporary France 25: 403–415.

Clift, B., and M. Ryner. 2014. Joined at the Hip, but Pulling Apart? Franco-German Relations, the Eurozone Crisis and the Politics of Austerity. French Politics 12: 136–163.

Couper, M. 2000. Review: Web Surveys: A Review of Issues and Approaches. The Public Opinion Quarterly 64: 464–494.

Czeglédi, P., and C. Newland. 2018. Measuring Global Support for Free Markets, 1990–2014. In Economic Freedom of the World, 2018th ed., ed. J. Gwartney, et al., 189–211. Vancouver.

Dares 2020. Situation sur le marché du travail durant la crise sanitaire au 8 décembre 2020. https://dares.travail-emploi.gouv.fr/publications/situation-sur-le-marche-du-travail-durant-la-crise-sanitaire-au-8-decembre-2020, accessed 15 September 2023.

Dares 2021. Situation sur le marché du travail durant la crise sanitaire au 5 janvier 2021. https://dares.travail-emploi.gouv.fr/publications/situation-sur-le-marche-du-travail-durant-la-crise-sanitaire-au-5-janvier-2021 accessed 15 September 2023.

Duménil, G., and D. Lévy. 2004. Capital resurgent. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Eurostat 2020. GDP main aggregates and employment estimates for the second quarter of 2020, 8 September 2020. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/2995521/10545471/2-08092020-AP-EN.pdf/437646135472e407a24-d20c30a20f64 accessed 15 September 2023.

Ferguson, N., D. Laydon, G. Nedjati Gilani, N. Imai, K. Ainslie, M. Baguelin, S. Bhatia, A. Boonyasiri, Z. Cucunuba Perez, G. Cuomo Dannenburg, A. Dighe, I. Dorigatti, H. Fu, K. Gaythorpe, W. Green, A. Hamlet, W. Hinsley, L. Okell, S. Van Elsland, H. Thompson, R. Verity, E. Volz, H. Wang, Y. Wang, P. Walker, P. Winskill, C. Whittaker, C. Donnelly, S. Riley, and A. Ghani. 2020. Report 9: Impact of non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) to reduce COVID-19 mortality and healthcare demand, Imperial College London.

Ferragina, E. 2022. Welfare state Change as a Double Movement: Four Decades of Retrenchment and Expansion in Compensatory and Employment-Oriented Policies Across 21 High-Income Countries. Social Policy & Administration 56: 705–725.

Ferragina, E., and A. Arrigoni. 2021. Selective Neoliberalism: How Italy went from Dualization to Liberalisation in Labour Market and Pension Reforms. New Political Economy 26: 964–984.

Ferragina, E., and F. Filetti. 2022. Labour Market Protection Across Space and Time: A Revised Typology and a Taxonomy of Countries’ Trajectories of Change. Journal of European Social Policy 32: 148–165.

Ferragina, E., and A. Zola. 2022. The End of Austerity as Common Sense? An Experimental Analysis of Public Opinion Shifts and Class Dynamics During the Covid-19 Crisis. New Political Economy 27: 329–346.

Ferragina, E., A. Arrigoni, and T. Spreckelsen. 2022. The Rising Invisible Majority: Bringing Society Back into International Political Economy. Review of International Political Economy 29: 114–151.

Fourcade-Gourinchas, M., and S. Babb. 2002. The Rebirth of the Liberal Creed. American Journal of Sociology 108: 533–579.

Global wealth databook 2021. Global Wealth Report. https://www.credit-suisse.com/about-us/en/reports-research/global-wealth-report.html accessed 15 September 2023.

Goldstein, D., and J. Wiedemann. 2021. Who Do You Trust? The Consequences of Partisanship and Trust for Public Responsiveness to COVID-19 Orders. Perspectives on Politics 20: 1–27.

Gramsci, A. 2014 [1975]. Quaderni del Carcere: Edizione critica dell’Istituto Gramsci a cura di Valentino Gerratana. Torino: Einaudi.

Hall, P., and D. Soskice, eds. 2001. Varieties of capitalism. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Harvey, D. 2005. A Brief History of Neoliberalism. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hemerijck, A. 2013. Changing welfare states. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hirschman, A. 1991. The Rhetoric of Reaction. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Inglehart, R. 2018 [1990]. Culture Shift in Advanced Industrial Society. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Inglehart, R., and P. Norris. 2017. Trump and the Populist Authoritarian Parties: The Silent Revolution in Reverse. Perspectives on Politics 15: 443–454.

Insee 2021. Le PIB se replie au quatrième trimestre (–1,3 %) - Informations rapides - 026. https://www.insee.fr/fr/statistiques/5018361 accessed 15 September 2023

Jessop, B. 1993. Towards A Schumpeterian Workfare State? Studies in Political Economy 40: 7–39.

Jost, J. 2006. The end of the End of Ideology. American Psychologist 61: 651–670.

Jost, J., J. Glaser, A. Kruglanski, and F. Sulloway. 2003. Political Conservatism as Motivated Social Cognition. Psychological Bulletin 129: 339–375.

Kerr, J., C. Panagopoulos, and S. van der Linden. 2021. Political Polarization on COVID-19 Pandemic Response in the US. Personality and Individual Differences 179: 1–9.

Kritzinger, S., M. Foucault, R. Lachat, J. Partheymüller, C. Plescia, and S. Brouard. 2021. ‘Rally Round the Flag’: The COVID-19 Crisis and Trust in the National Government. West European Politics 44: 1205–1231.

Lenglet, F. 2020. Quoi qu’il en coûte ! Paris: Albin Michel.

Lesschaeve, C., J. Glaurdic, and M. Mochtak. 2021. Health Versus Wealth During the Covid-19 Pandemic. Public Opinion Quarterly 85 (3): 808–835.

Macron, E. 2020. Adresse aux Français du Président de la République. 16 March, Le palais de l’Élysée, Paris. https://www.elysee.fr/emmanuel-macron/2020/03/16/adresse-aux-francais-covid19 accessed 15 September 2023.

Margalit, Y. 2013. Explaining Social Policy Preferences: Evidence from the Great Recession. American Political Science Review 107: 80–103.

Marpsat, M., and N. Razafindratsima. 2010. Survey Methods for Hard-to-Reach Populations. Methodological Innovations Online 5: 3–16.

Mirowski, P., and D. Plehwe. 2009. The Road from Mont Pèlerin. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Mitrea, E., M. Mühlböck, and J. Warmuth. 2021. Extreme Pessimists? Expected Socioeconomic Downward Mobility and the Political Attitudes of Young Adults. Political Behavior 43: 785–811.

Oana, I., A. Pellegata, and C. Wang. 2021. A Cure Worse Than the Disease? Exploring the Health-Economy Trade-Off During COVID-19. West European Politics 44: 1232–1257.

OECD 2023. Social Expenditure Database (SOCX). https://www.oecd.org/social/expenditure.htm accessed 15 September 2023.

Paterson, M. 2020. Climate Change and International Political Economy. Review of International Political Economy 28: 394–405.

Pierson, P. 2001. The New Politics of the Welfare State. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Piketty, T., and G. Zucman. 2014. Capital is Back: Wealth-Income Ratios in Rich Countries 1700–2010. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 129: 1255–1310.

Polanyi, K. 1944. The Great Transformation: The Political and Economic Origins of Our Time. New York, NY: Farrar and Rinehart.

Prasad, M. 2006. The Politics of Free Markets. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press.

Recchi, E., E. Ferragina, O. Godechot, E. Helmeid, S. Pauly, M. Safi, N. Sauger, J. Schradie, K. Tittel, and A. Zola. 2020. Living through Lockdown: Social Inequalities and Transformations during the COVID-19 Crisis in France. Zenodo.

Recchi, E., E. Ferragina, M., Safi, N., Sauger, J., Schradie. 2021. Coping with Covid-19: Social distancing, cohesion and inequality in 2020 France.

Ritchie, H., Mathieu, E., Rodés-Guirao, L., Appel, C., Giattino, C., Ortiz-Ospina, E., Hasell, J., Macdonald, B., Beltekian D., and Roser, M. 2020. Coronavirus Pandemic (COVID-19). Accessed at: https://ourworldindata.org/coronavirus accessed 2 December 2021.

Safi, M., P. Coulangeon, E. Ferragina, O. Godechot, E. Helmeid, S. Pauly, E. Recchi, N. Sauger, J. Schradie, K. Tittel, and A. Zola. 2020. La France confinée. Anciennes et nouvelles inégalités. In: M. Lazar, G. Plantin and X. Ragot (eds.) Le Monde d’aujourd’hui. Les sciences sociales au temps du Covid. Paris: Presses de Sciences Po, pp. 93–116.

Scherbina, A.D. 2020. Determining the Optimal Duration of the COVID-19 Suppression Policy: A Cost-Benefit Analysis. SSRN Journal.

Scherpenzeel, A. 2011. Data Collection in a Probability-Based Internet Panel. Bulletin of Sociological Methodology 109: 56–61.

Schmidt, V. 2003. French Capitalism Transformed, Yet Still a Third Variety of Capitalism. Economy and Society 32: 526–554.

Somers, M., and F. Block. 2005. From Poverty to Perversity: Ideas, markets, and Institutions over 200 Years of Welfare Debate. American Sociological Review 70: 260–287.

Stanley, L. 2014. ‘We’re Reaping What We Sowed’: Everyday Crisis Narratives and Acquiescence to the Age of Austerity. New Political Economy 19: 895–917.

Streeck, W., and K. Thelen. 2005. Beyond Continuity: Institutional Change in Advanced Political Economies. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Unédic. 2020. Premier bilan activité partielle crise Covid- Bureau du 23 septembre 2020. https://www.unedic.org/sites/default/files/2020-09/Un%C3%A9dic%20-%20Premier%20bilan%20activit%C3%A9%20partielle%20crise%20Covid-%20Bureau%20du%2023%20septembre%202020%20VF.pdf accessed 15 September 2023.

Watson, M., and C. Hay. 2003. The Discourse of Globalisation and the Logic of No Alternative. Policy & Politics 31: 289–305.

WHO 2021. WHO Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Dashboard https://covid19.who.int/table accessed 2 December 2021.

Williamson, J. 1990. What Washington means by policy reform. In: J. Frieden, M. Pastor and M. Tomz (eds.) Modern Political Economy and Latin America.

Acknowledgements

We must first thank the entire Coping with Covid-19 (CoCo) research team, including Mirna Safi, Jen Schradie, and Katharina Tittel, along with other collaborating CRIS scholars, notably Olivier Godechot and Philippe Coulangeon. Nicolas Sauger, Emmanuelle Duwez, Mathieu Olivier, and Laureen Rotelli-Bihet at the Centre de données socio-politiques (CDSP) have been indispensable from start to finish in regard to our data. The views expressed herein are those of the authors. The CoCo project was funded by the Flash Covid-19 call by the French Agence nationale de la recherche (ANR), March 2020.

Funding

Funding for this study was received from the Flash Covid-19, L’Agence nationale de la recherche (ANR), March 2020.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Ferragina, E., Zola, A., Pasqualini, M. et al. Understanding public attitudes during Covid-19 in France with Polanyi and Gramsci: a political economy of an epidemiological and economic disaster. Comp Eur Polit (2023). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41295-023-00369-x

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41295-023-00369-x