Abstract

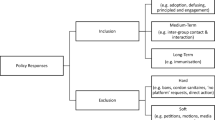

Departing from a critique of existing classification schemes in work on ‘militant’ and ‘defending’ democracy, the article presents a new typology for classifying initiatives opposing populist parties (IoPPs). The typology incorporates public authorities, political parties and civil society actors operating at state and supranational levels along one dimension, and tolerant and intolerant modes of engagement with populist parties on another dimension. The six types of opposition identified—rights-restrictions, ostracism, coercive confrontation, ordinary legal controls and pedagogy, forbearance, and adversarialism—are illustrated with empirical examples of opposition from populist parties in opposition and government, and by domestic actors and international organisations. The article then turns to outline methods for collecting data on IoPPs in contemporary Europe using a newspaper sampling techniques inspired by protest event and political claims analysis as a starting point. The final section presents four patterns of opposition to populist parties, ‘adapted-militancy’ (Germany), ‘political competition’ (Denmark); a ‘pincer-movement’ (Poland), and ‘differentiated ordinary opposition’ (Italy) models.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The team continues to collect data on opposition to Fidesz and Jobbik in Hungary, Sweden Democrats, and Podemos and Vox in Spain.

A fourth subtype of ordinary legal controls and pedagogy is policy and legislative responses (see Bourne 2022 for details). It is not discussed here because policy and legislative responses often pursue more general goals in addition to opposing populist parties and require more in-depth, qualitative research methods to identify them than the ones used here.

The variables used were People_vs_elite; Antielite_salience; Corruption_salience.

References

Akkerman, T., S. de Lange, and M. Roodouijn, eds. 2016. Radical right-wing populist parties in Western Europe: Into the mainstream? Abingdon: Routledge.

Albertazzi, D., and D. Vampa, eds. 2021. Populism and new patterns of political competition in Western Europe. Milton: Taylor and Francis.

Art, D. 2007. Reacting to the radical right: Lessons from Germany and Austria. Party Politics 13: 331–349.

Bale, T. 2003. Cinderella and her ugly sisters: The mainstream and extreme right in Europe’s bipolarising party systems. West European Politics 26: 67–90.

Bleich, E. 2011. The rise of hate speech and hate crime laws in liberal democracies. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 37 (6): 917–934.

Bourne, A. (2022) From militant democracy to normal politics? How European democracies respond to populist parties, European Constitutional Law Review.

Bourne, A. 2018. Democratic Dilemmas: Why democracies ban political parties. London: Routledge.

Campo. F. 2023. Differentiated opposition in collective mobilization: Countering Italian populism. Comparative European Politics. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41295-023-00337-5.

Canovan, M. 1999. Trust the People! populism and the two faces of democracy. Political Studies XLVII: 2–16.

Capoccia, G. 2005. Defending democracy: Reactions to extremism in interwar Europe. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press.

Charmaz, C. 2014. Constructing grounded theory. London: Sage.

Koopmans, R. and Rucht, D. (2002). ‘Protest Event Analysis’ In (Eds). Klandermans. B and Staggenborg. Methods of Social Movement Research. Minneapolis: The University of Minnesota Press, pp. 231–59.

Dahl, R. 2000. On Democracy. Yale University Press.

Downs, W. 2012. Political extremism in democracies: Combatting intolerance. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Drisk, J.W. and T. Maschi. 2015. Content analysis. New York: Oxford University Press.

Earl, J Martin, A.J. McCarthy, and S. Soule. 2004. The use of newspaper data in the study of collective action. Annual Review of Sociology 30: 65–80.

Fink-Hafner, D., and A. Krasovec. 2014. Slovenia. European Journal of Political Research Political Data Yearbook 53: 281–286.

Fox, G., and G. Nolte. 2000. Intolerant democracies. In Democratic governance and international law, eds. G. Fox, and B. Roth, 389–435. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Huber, R.A., and C.H. Schimpf. 2017. On the distinct effects of left-wing and right-wing populism on democratic quality. Politics and Governance 5: 146–165.

Hutter, S. (2014) Protest Event Analysis and Its Offspring. In: Methodological Practices in Social Movement Research (edited by D. della Porta). P. 336–405.

Keane, J. (2004) Violence and Democracy (Cambridge University Press 2004).

Laclau, E. 2005. On populist reason. London: Verso.

Laumond, B. 2023. Increasing toleration for the intolerant? “Adapted miitancy” and German responses to Alternative for Germany. Comparative European Politics. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41295-023-00336-6.

Loewenstein, K. 1937. Militant democracy and fundamental rights II. The American Political Science Review 31: 638–658.

Lührmann, A., and S.I. Lindberg. 2019. A third wave of autocratization is here: What is new about it? Democratization 26: 1095–1113.

Malkopoulou, A., and A. Kirshner, eds. 2019. Militant Democracy and Its Critics. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Meguid, B.M. 2005. Competition between unequals: The role of mainstream party strategy in Niche party success. American Political Science Review 99: 347–359.

Moroska-Bonkiewicz, A., and K. Domagała. 2023. Opposing populists in power: how and why Polish civil society Europeanized their opposition to the rule of law crisis in Poland. Comparative European Politics. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41295-023-00339-3.

Motak, D., J. Krotofil, and K. Wójciak. 2021. The Battle for Symbolic Power: Kraków as a Stage of Renegotiation of the Social Position of the Catholic Church in Poland. Religions 12: 594–612.

Mouffe, C. (2000) The Democratic Paradox (Verso).

Mudde, C. 2004. The populist zeitgeist. Government and Opposition 39: 541–563.

Mudde, C., and C. Rovira Kaltwasser. 2017. Populism: A very short introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Müller, J.-W. 2016. What is populism? Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Mudde, C. & Rovira Kaltwasser, C. (2012). Populism and (liberal) democracy: a framework for analysis. In: Populism in Europe and the Americas: Threat or Corrective for Democracy? (edited by C. Mudde & C. Rovira Kaltwasser). Pp. 1–26. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Müller, J.-W. 2012. Militant democracy. In The Oxford handbook of comparative constitutional law, ed. M. Rosenfeld and A. Sajó, 1253–1269. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Müller, W. & Strøm, K. (1999) Policy Office or Votes? (Cambridge University Press)

Nicolaisen, M.H. 2023. From toleration to recognition: Explaining change and stability in party responses to the Danish People's Party. Comparative European Politics. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41295-023-00338-4.

Ostiguy, P. (2017). Populism: A Socio-Cultural Approach. In: The Oxford Handbook of Populism (edited by C. Kaltwasser Rovira, P. Taggart, P. Espejo Ochoa & P. Ostiguy). Pp. 73–100. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Pedahzur, A. 2004. The defending democracy and the extreme right: A comparative analysis. In Western democracies and the new extreme right challenge, ed. R. Eatwell and C. Mudde, 108–132. London: Routledge.

Ritchie, J., and L. Spencer. 1994. Qualitative data analysis for applied policy research. In Analyzing qualitative data, ed. A. Bryman and B. Burgess, 173–196. London: Taylor and Francis Group.

Rooduijn, M. 2019. State of the field: How to study populism and adjacent topics? A plea for both more and less focus. European Journal of Political Research 58: 362–372.

Rosenblum, N. 2008. On the side of the angels: An appreciation of Parties and Partisanship. Princeton University Press.

Rummens, S., and K. Abts. 2010. Defending democracy: The concentric containment of political extremism. Political Studes 58: 649–665.

Ruth-Lovell, S.P., Lührmann, A. & Grahn, S. (2019). Democracy and Populism: Testing a Contentious Relationship. SSRN Electronic Journal.

Sadurski, W. 2019. Poland’s Constitutional Breakdown. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Scheppele, K.L., D. Vladimirovich Kochenov, and B. Grabowska-Moroz. 2020. EU values are law, after all: Enforcing EU values through systemic infringement actions by the european commission and the member States of the European Union. Yearbook of European Law 39: 3–121.

Scheppele, K.L. 2018. Autocratic legalism. The University of Chicago Law Review 85: 545–585.

Schimmelfennig, F., and U. Sedelmeier. 2020. The Europeanization of Eastern Europe: The external incentives model revisited. Journal of European Public Policy 27: 814–833.

Taggart, P. 2002. Populism and the pathology of representative politics. In Democracies and the populist challenge, ed. Meny, Y., and Y. Surel, 62–80. Houndsmills: Palgrave Macmillan.

Tarrow, S. 2011. Power in movement: Social movements and contentious politics. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Tarrow, S., and C. Tilly. 2006. Contentious Politics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Tilly, C. 2003. The politics of collective violence. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Tyulkina, S. 2015. Militant democracy: Undemocratic political parties and beyond. London: Routledge.

Van Spanje, J. 2018. Controlling the electoral marketplace. How Established Parties Ward Off Competition: Springer International Publishers.

Ware, A. 1995. Political parties and party systems. Oxford University Press.

van Heerden, S & W. van der Brug, Demonization and electoral support for populist right parties, 47 Electoral Studies (2017), p. 37.

Weyland, K. (2017). Populism: A Political-Strategic Approach. In: Oxford Handbook of Populism (edited by P. Taggart, P. Ostiguy, C. Kaltwasser Rovira & P. Espejo Ochoa). Pp. 48–72. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Wistrich, R. (2012) Holocaust Denial: The Politics of Perfidy (De Bruyter 2012)

Zulianello, M. 2020. Varieties of populist parties and party systems in Europe: From State-Of-The-Art to the application of a novel classification scheme to 66 parties In 33 countries. Government and Opposition 55: 327–347.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Tore Vincents Olsen, Francesco Campo, Mathias Holst Nicolaisen, Aleksandra Moroska-Bonkiewicz, Bénédicte Laumond, Franciszek Tyszka, Katarzyna Domagała, Juha Tuovinen, Anthoula Malkopoulou, Patrick Nitzschner and 2 anonymous reviewers for Comparative European Politics for comments on earlier versions of this paper. All errors remain fully mine.

Funding

This research was in part financed by the Carlsberg Foundation Grant CF20-0008.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Bourne, A. Initiatives opposing populist parties in Europe: types, methods, and patterns. Comp Eur Polit 21, 742–760 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41295-023-00343-7

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41295-023-00343-7